Abstract

This article presents the development and validation process of a qualitative data collection instrument aimed at analysing natural sciences teachers’ perceptions of practical work in lower secondary education (third cycle) in Portugal. The methodological approach combined a systematic literature review following PRISMA guidelines with an analysis of relevant curricular frameworks and legal documents. Based on the triangulation of these sources, a semi-structured interview guide was constructed, validated by a panel of five experts from four Portuguese public universities, and tested through a pilot interview. The final instrument comprised seven dimensions and fourteen subdimensions, totalling 44 items. It demonstrated methodological rigour and practical applicability for qualitative data collection and analysis. Findings indicate that the instrument enables a comprehensive exploration of teachers’ practices and perceptions regarding practical work, offering a valuable contribution to the research on didactics of science and to the professional development of teachers. Also, the application of this instrument will enable teachers and researchers to characterise the dynamics of practical work carried out with young students in natural sciences education across seven structuring dimensions: (1) Conceptual; (2) Limitations; (3) Advantages; (4) Evaluative; (5) Operationalisation; (6) Textbook; and (7) Curricular.

1. Introduction

Practical work (PW) represents a central pillar in natural sciences education, playing a key role in promoting scientific literacy and in developing students’ cognitive and procedural skills (Abrahams & Reiss, 2012). This pedagogical approach, often associated with hands-on and minds-on methodologies, fosters active and meaningful learning experiences, enabling the integration of theory and practice and supporting the construction of contextualised scientific knowledge (Harrison, 2016; Wei et al., 2019).

However, despite the consensus on the pedagogical value of PW, its effective implementation in schools faces significant constraints related to limited resources, time, teacher training, and curricular alignment (Akuma & Callaghan, 2019; Ramnarain & de Beer, 2013). As noted by Ferreira and Morais (2014), the conceptual and operational complexity of PW requires clear articulation among its conceptual, procedural, and evaluative dimensions; otherwise, it risks being reduced to a merely technical activity, lacking scientific and pedagogical intentionality.

In this context, the need for valid and reliable instruments to collect data on teachers’ perceptions and practices regarding PW becomes evident. Research on the didactics of science has emphasised that the development and validation of such instruments allow for a deeper understanding of how teachers interpret, implement, and reflect on PW within their professional practice (Abrahams et al., 2014; Hartman & Squires, 2024).

This study addresses this gap by developing and validating a comprehensive interview guide designed to collect qualitative data on PW in natural sciences education, specifically within the third cycle of Portuguese basic education. Grounded in a systematic literature review (SLR) (Oliveira & Bonito, 2023) and an analysis of the national curricular guidelines (DGE, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c; Martins et al., 2017), the instrument aims to explore teachers’ perceptions regarding the conceptual, evaluative, operational, and curricular dimensions of PW, promoting a holistic understanding of scientific practice in educational contexts.

The focus of this study is the characterisation of practical work in natural sciences education in the 3rd cycle of basic education within the Portuguese education system. In addition, the study aims to contribute to this characterisation through the development of the qualitative data collection instrument, illustrated and characterised in this manuscript. The overarching research question that guided all procedures in this investigation was the following: How do natural sciences teachers in the 3rd cycle of basic education perceive and implement practical work in their teaching practice?

In the reference list of the main body of this scientific article, we include the references of the authors cited in the text, as well as those underpinning the domains, subdomains, objectives, questions, criteria, and indicators of the interview protocol, the full version of which can be consulted in Supplementary File S1—Qualitative Data Collection Instrument. These authors correspond to the corpus of 53 manuscripts selected through the previously conducted SLR. Additionally, legal regulations from the legislation of the Portuguese Republic, as well as the national curriculum guidelines for the subject of natural sciences in the 3rd cycle of basic education, were also consulted and incorporated into the reference list.

2. Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review on Practical Work

The first step in this process was conducting an SLR on the state of the art of practical work in science education. This review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines (Page et al., 2021) and conducted across five distinct databases: B-on, ERIC, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. Table 1 outlines the objective of the SLR, its research question, the keywords used in the search equations, and the inclusion/exclusion criteria applied to the selected databases.

Table 1.

Structure of the Research Protocol.

Table 2 identifies the databases, query options, query criteria, and document count that resulted in the initial set of 163 potentially relevant manuscripts, which were subsequently subjected to a screening process.

Table 2.

Findings from the initial identification of studies in the systematic literature review.

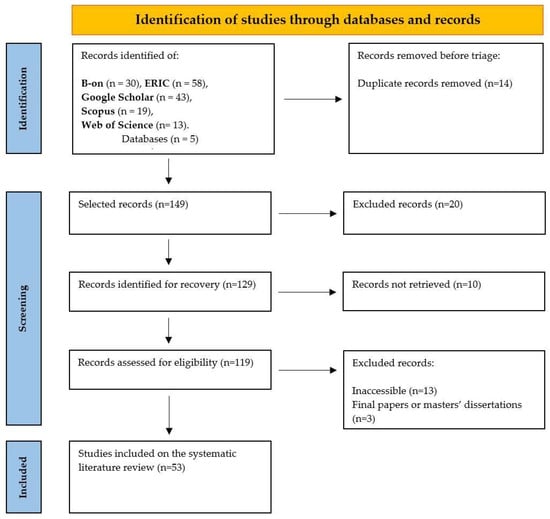

In the initial phase of the SLR, 163 potentially relevant studies were identified. Following a screening process—which included the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, removal of duplicates, and elimination of out-of-scope studies—a final corpus of 53 relevant studies was established for document analysis. Figure 1 presents the flow diagram illustrating the processes of identification, screening, and inclusion that led to the selection of these 53 manuscripts for documentary analysis.

Figure 1.

Screening results for the constitution of the corpus. Retrieved from Oliveira and Bonito (2023, p. 5).

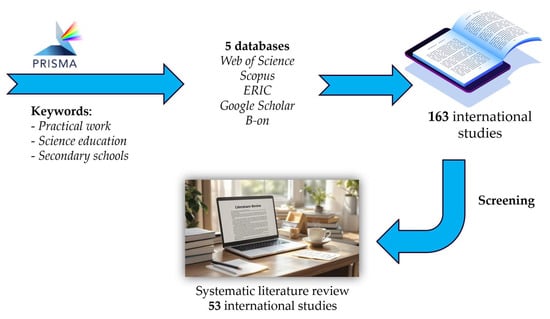

Through the graphical illustration in Figure 2, a simplified overview of the process followed throughout the various stages of the SLR on practical work in science education can be established.

Figure 2.

Outline of the methods applied in the systematic literature review. Figure created by the authors. Icons sourced from the Microsoft Office image library.

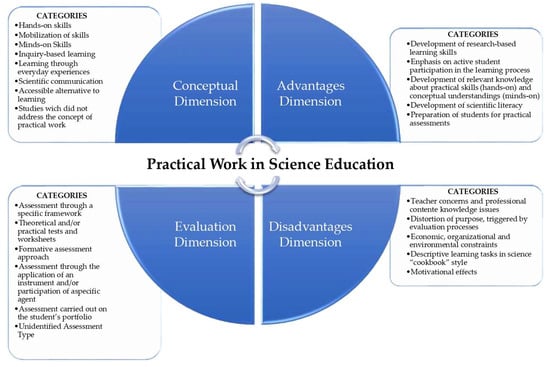

This SLR highlighted four major dimensions of the dynamics of practical work in science education: (1) the conceptual dimension; (2) the advantages dimension; (3) the evaluation dimension; and (4) the disadvantages dimension. Figure 3 illustrates the categories of practical work dimensions under analysis.

Figure 3.

Outline of the methods applied in the design and validation of the interview guide. Figure created by the authors. Icons sourced from the Microsoft Office image library.

2.2. Design of the Interview Guide

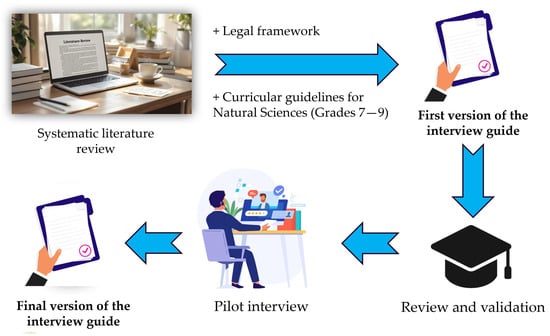

By triangulating the data obtained from the SLR with the curricular guidelines for natural sciences in the third cycle of basic education and relevant legal frameworks, it was possible to structure the first version of the interview guide (including its objectives, questions, criteria, and indicators). In addition to the four dimensions considered in the SLR, the analysis of legal regulations and curriculum guidelines enabled the inclusion of three further relevant dimensions in the first version of the interview guide: the operationalisation dimension, the textbook dimension, and the curricular dimension.

More specifically, the intention to conduct an interview-based survey with teachers of the natural sciences subject in the third cycle of basic education led to the development of a comprehensive, semi-structured interview guide, grounded in the Kaufmann (2004) approach, which places particular emphasis on the context in which actions occur, and the meanings constructed within it. With the aim of analysing Biology and Geology teachers’ perceptions regarding the PW carried out in the natural sciences subject at this educational level within the Portuguese education system, this instrument was developed and validated to enable an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (Hartman & Squires, 2024). This approach is intended to make it possible to interpret detailed, first-person accounts of the PW promoted in the natural sciences curriculum, thereby unveiling its underlying meanings. Reflecting on the value of IPA, we would acknowledge that its layered analytical structure—encompassing the exploration of content, contextual dimensions, and linguistic features such as metaphor—would offer a vivid and meaningful portrayal of participants’ lived experiences. By comparing these elements within and across cases, the approach would allow for a deep and intimate understanding of the phenomena under study. Our engagement with IPA would reveal the immersive nature of the methodology, providing a comprehensive framework that could assist researchers in grasping the complexities embedded in participants’ accounts. Moreover, IPA would prompt researchers to question and bracket their own taken-for-granted assumptions, enabling participants’ underlying experiences to surface more clearly. This process would not only enhance the analytical depth but also contribute to a more nuanced and authentic representation of participants’ perspectives.

The interview protocol developed herein was designed with the intention of conducting interviews with 23 natural sciences teachers within the Portuguese education system. For the study in which this qualitative data collection instrument will be applied, one natural sciences teacher from the 3rd cycle of basic education will be selected from a school or school cluster in each district of mainland Portugal, totalling 18 teachers. Regarding the archipelago of the Autonomous Region of the Azores, one teacher will be selected from each island group (Eastern, Central, and Western), based on convenience sampling, resulting in a total of three teachers. For the archipelago of the Autonomous Region of Madeira, two teachers will be selected, also through convenience sampling, who are currently teaching on Porto Santo Island and Madeira Island, respectively.

As previously demonstrated, the construction of the instrument was based on an SLR, concerning PW in science education at the pre-university level (UNESCO, 2012), which enabled the identification of the state of the art regarding the international adoption of this methodology. In a second phase, an analysis was conducted of the Portuguese curricular guidelines for the teaching of natural sciences in the third cycle of basic education, with the aim of gathering elements that would facilitate an adaptation as closely aligned as possible with the scope of this educational level. To this end, the Student Profile at the End of Compulsory Schooling framework (Martins et al., 2017) and the Essential Learnings defined for the natural sciences subject in the third cycle were examined (DGE, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c). Additionally, legal frameworks within Portuguese legislation were analysed for their potential impact on the dynamics of PW in science education (Portugal, 2018a, 2018b, 2018c), with a view to triangulating this information with the previously identified documents.

Based on the triangulation of information from the SLR, the curricular guidelines, and the legal frameworks, the questions that comprise the interview guide were defined. These questions are intrinsically linked to a set of criteria and indicators designed to serve as a guide for the interviewer, helping to steer the interview toward relevant topics and to more effectively capture the meanings attributed by natural sciences teachers to the phenomena under investigation. These sets of criteria and indicators will also serve, subsequently, as facilitators for the content analysis of the participants’ discourse, particularly within the topics embedded in each dimension and subdimension of the semi-structured interview. Furthermore, to support the processes previously described, a set of clearly defined objectives was established for each of the outlined dimensions and subdimensions, clarifying the scope and purpose of the questions addressed in each area.

Subsequently, the first version of the instrument underwent a review process supported by five experts from four Portuguese public universities. Once validated, the guide was tested in a pilot interview with a natural sciences teacher from the Lisbon district, leading to its final version. A synthesis of this entire process is illustrated in Figure 3, which depicts the key stages and the sequence of steps followed.

3. Results

The SLR made it possible to identify four major dimensions associated with the dynamics of practical work in science education: (1) the conceptual dimension; (2) the advantages dimension; (3) the evaluative dimension; and (4) the disadvantages dimension. Figure 4 provides a synthesis of these results.

Figure 4.

Dimensions of practical work and its emergent categories. Note. Adapted from Oliveira and Bonito (2023).

These four dimensions identified through the SLR were subsequently incorporated into the structure of the qualitative data collection instrument, to which the operationalisation dimension, the textbook dimension, and the curricular dimension were added. These additional dimensions emerged from the triangulation of data with relevant legal frameworks in Portuguese legislation and with the natural sciences curriculum guidelines for the 3rd cycle of basic education, as described in the previous section.

The overall structure of the first version of the interview guide is presented in Table 3, illustrating the distribution of the defined questions (items) across the respective dimensions and subdimensions under study.

Table 3.

General Structure of the Interview Guide (First version).

An analysis of the overall structure of the first version of the interview guide reveals that it constituted an instrument comprising seven dimensions, which were further subdivided into nineteen specific subdimensions, encompassing a total of thirty-eight items.

Following the development of this initial version of the interview script, contact was established with five experts from four different Portuguese public universities (University of Aveiro, University of Lisbon, University of Minho, and University of Porto), with the aim of obtaining their contributions towards the validation of this qualitative data collection instrument. Accordingly, and in order of response to the invitation, the five experts are coded as presented in Table 4, which also includes the number of optimisation suggestions proposed by each expert.

Table 4.

Coding of experts involved in the interview script validation process and their optimisation suggestions.

The experts’ recommendations primarily revolved around the following aspects: (a) paying attention to the potentially ambitious length of the interview script and the effects of fatigue during extended interviews; (b) simplifying the concepts of (multi)interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity and instead asking whether the teacher “usually conducts project work with colleagues from other disciplines, and in what ways?”; (c) balancing the number of items/questions addressing both the advantages and disadvantages of project work; (d) avoiding overly goal-oriented or directive questions, thereby allowing space for the interviewees’ reasoning and discourse; and (e) requesting concrete examples or descriptions of everyday teaching practices.

After incorporating the experts’ suggestions, the interview script was then validated and adopted its final structure, after a pilot interview, being structured as illustrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

General structure of the interview script (Final Version).

The final version of the interview script adopted a more simplified structure, due to a reduction in the number of subdimensions. Nevertheless, six additional items were included overall. These details can be more thoroughly examined in the comparative table between the initial and final versions of the interview script (Table 6).

Table 6.

General structures of the first version and the final version of the qualitative data collection instrument.

An analysis of the previous table reveals that both versions contain an identical number of dimensions. However, the initial version is structured into 19 subdimensions, whereas the final version comprises 14 subdimensions. Regarding the number of items, the initial version includes 38 questions, while the final version comprises 44 questions.

To provide a more comprehensive and detailed overview of the structure of this qualitative data collection instrument, Table 7 presents a fragment of the specific structure of its final version, focusing on the first dimension under analysis (conceptual dimension). Including the full qualitative data collection instrument in the main manuscript would exceed the recommended length for this article. To provide a concise yet informative overview of its structure, only an illustrative excerpt is presented. The complete instrument is available in Supplementary File S1—Qualitative Data Collection Instrument.

Table 7.

Specific structure of the interview script—Conceptual dimension.

In general, the specific structure of the qualitative data collection instrument comprises seven distinct columns. From left to right, these include the identification of the dimension under analysis, followed by its corresponding subdimension. Next is the column outlining the objectives, followed by the column listing the items/questions. The criteria column is also included, which is particularly useful during the interview process, as well as the indicators column, which plays a key role during the content analysis phase—both of which are highly valuable in these two critical stages of the interview-based inquiry. Finally, the last column presents the authors and/or legal frameworks that underpin the preceding content.

Following the validation process by the panel of reviewers, a pilot interview was conducted on 26 May 2023, with a natural sciences teacher from the 3rd cycle of basic education, who has been teaching at the same school in the Lisbon district for 27 years. During the semi-structured interview, which lasted 85 min, the script proved to be a robust instrument, enabling an intuitive and comprehensive collection of qualitative data. Additionally, the instrument also demonstrated its effectiveness in facilitating the content analysis process of the collected data, owing to the clear definition of its objectives, criteria, indicators, authors, and legal frameworks—elements supported by an SLR on the state of the art of PW in science education. For the reasons outlined above, this interview script is considered suitable for holistically analysing natural sciences teachers’ perceptions of PW in their daily teaching practice, whether individually or in an integrated manner.

Finally, and as previously mentioned, the complete and final version of this qualitative data collection instrument is included as a Supplementary File to the main body of this manuscript (see Supplementary File S1—Qualitative Data Collection Instrument).

Table 8 summarises the dimensions of the qualitative data collection instrument, identifying the authors and regulations that underpinned its objectives, questions, criteria, and indicators.

Table 8.

Dimensions and Theoretical Foundations of the Qualitative Data-Collection Instrument.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The development of this qualitative data collection instrument aims to contribute to the characterisation of the dynamics of practical work across seven distinct dimensions, all of which are incorporated into the interview guide, the construction and validation process of which is presented in this manuscript. Designed to interview natural sciences teachers in the 3rd cycle of basic education, the instrument is intended to support the in-depth collection of teachers’ accounts, thereby contributing to the grounding of policies, curriculum guidelines, the optimisation of school administration, and the promotion of collaborative practices that enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of practical work in natural sciences education with young students.

This study does not seek to generalise data concerning the acceptability and consistency of the interviews. Instead, it focuses on describing the design and validation process of the qualitative data collection instrument, carried out through expert review and pilot testing. The validation process involved assessment by five experts from four Portuguese public universities, which ensures the survey’s credibility and scientific rigour. None of the experts involved in reviewing this qualitative instrument is affiliated with the authors’ university or engaged in joint projects, thereby eliminating any potential conflicts of interest. At this stage, the data are used to confirm the instrument’s clarity, reliability, and internal consistency, rather than to draw conclusions that can be extrapolated to broader populations. The methodological emphasis lies in validating and consolidating the tool, not in generalisation. Future research may include broader and more quantitative validation of this instrument.

For a holistic discussion of the results, it is also highly relevant to establish a general characterisation of the qualitative data collection instrument, with particular emphasis on its potential. Accordingly, the following considerations can be made: (a) It is a robust instrument that enables the collection of data across seven dimensions of practical work dynamics in the natural sciences subject of Lower Secondary Education. (b) It subsequently facilitates the process of content analysis, supported by its clearly defined criteria and indicators. (c) It contributes to the analysis of teachers’ perceptions regarding their individual pedagogical practice and may be particularly useful in processes of self-assessment and peer evaluation. (d) It also supports the analysis of teachers’ perceptions of their pedagogical practice in interaction with colleagues and the broader educational community, offering valuable insights into the dynamics of practical work in natural sciences education.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/youth6010010/s1. The complete and final version of the qualitative data collection instrument is included as a supplementary file to the main body of this manuscript (see Supplementary File S1—Qualitative Data Collection Instrument). The reference list in the main article fully incorporates all citations from the Supplementary File.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.O.; methodology, H.O.; investigation, H.O.; resources, H.O.; data curation, H.O.; writing—original draft preparation, H.O.; visualisation, H.O.; Validation, J.B.; formal analysis, J.B.; writing—review and editing, J.B.; supervision, J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, grant number UI/BD/151078/2021, with the DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/UI/BD/151078/2021. The APC was funded by co-author Jorge Bonito.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute for Advanced Studies and Research of the University of Évora (GD/17004/2025, 8 May 2025). All data were handled in compliance with European data protection legislation, in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ELs | Essential Learnings |

| IPA | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PW | Practical Work |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SPECS | Student Profile at the End of Compulsory Schooling |

References

- Abrahams, I., & Reiss, M. (2012). Practical work: Its effectiveness in primary and secondary schools in England. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(8), 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I., Reiss, M., & Sharpe, R. (2013). The assessment of practical work in school science. Studies in Science Education, 49(2), 209–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I., Reiss, M., & Sharpe, R. (2014). The impact of the ‘Getting Practical: Improving Practical Work in Science’ continuing professional development programme on teachers’ ideas and practice in science practical work. Research in Science and Technological Education, 32(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, S., & Achufusi-Aka, N. N. (2020). Extent of integration of practical work in the teaching of chemistry by secondary schools teachers in Taraba State. UNIZIK Journal of STM Education, 3(2), 63–75. Available online: https://journals.unizik.edu.ng/index.php/jstme (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Akuma, F., & Callaghan, R. (2019). Teaching practices linked to the implementation of inquiry-based practical work in certain science classrooms. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 56(1), 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J., & Enghag, M. (2017). The relation between students’ communicative moves during laboratory work in physics and outcomes of their actions. International Journal of Science Education, 39(2), 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anza, M., Bibiso, M., Mohammad, A., & Kuma, B. (2016). Assessment of factors influencing practical work in chemistry: A case of secondary schools in Wolaita zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Education and Management Engineering, 6(6), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, F. E., Lambourne, R. J., & Swithenby, S. J. (2020). The real aims that shape the teaching of practical physics in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18(2), 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohloko, M., Makatjane, T. J., George, M. J., & Mokuku, T. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of using youtube videos in teaching the chemistry of group i and vii elements in a high school in Lesotho. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 23(1), 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonito, J., Morgado, M., Silva, M., Figueira, D., Serrano, M., Mesquita, J., & Rebelo, H. (2014a). Metas Curriculares—Ensino Básico—Ciências Naturais, 5.º, 6.º, 7.º e 8.º anos. Ministério da Educação e Ciência. Available online: http://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/ficheiros/eb_cn_metas_curriculares_5_6_7_8_ano_0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Bonito, J., Morgado, M., Silva, M., Figueira, D., Serrano, M., Mesquita, J., & Rebelo, H. (2014b). Metas Curriculares—Ensino Básico—Ciências Naturais 9.º ano. Ministério da Educação e Ciência. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/ficheiros/metas_curriculares_ciencias_naturais_9_ano_0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Costa, F., Paz, A., Pereira, C., Cruz, E., Soromenho, G., & Viana, J. (2022). Relatório de avaliação da implementação das aprendizagens essenciais. Instituto de Educação da Universidade de Lisboa. Available online: http://www.dge.mec.pt/noticias/relatorio-de-avaliacao-da-implementacao-das-aprendizagens-essenciais (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Danmole, B. T. (2012). Biology teachers’ views on practical work in senior secondary schools of South Western Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 9(2), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A., Fidler, D., & Gorbis, M. (2020). Future work skills 2020 report (pp. 1–19). Institute for the Future for the University of Phoenix Research Institute. Available online: https://legacy.iftf.org/uploads/media/SR-1382A_UPRI_future_work_skills_sm.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- DGE. (2018a). Aprendizagens essenciais—Ciências Naturais. 7.º ano. 3.º ciclo do ensino básico. Ministério da Educação. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/3_ciclo/ciencias_naturais_3c_7a_ff.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- DGE. (2018b). Aprendizagens essenciais—Ciências Naturais. 8.º ano. 3.º ciclo do ensino básico. Ministério da Educação. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/3_ciclo/ciencias_naturais_3c_8a_ff.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- DGE. (2018c). Aprendizagens essenciais—Ciências Naturais. 9.º ano. 3.º ciclo do ensino básico. Ministério da Educação. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Aprendizagens_Essenciais/3_ciclo/ciencias_naturais_3c_9a_ff.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- di Fuccia, D., Witteck, T., Markic, S., & Eilks, I. (2012). Trends in practical work in German science education. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 8(1), 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, D., O’Reilly, J., & McGarr, O. (2013). Enhancing the student experiment experience: Visible scientific inquiry through a virtual chemistry laboratory. Research in Science Education, 43, 1571–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, L. (2001). Trabalho Prático, Trabalho Laboratorial, Trabalho de Campo e Trabalho Experimental no Ensino das Ciências—Contributo para uma clarificação de termos. In Ensino Experimental das Ciências: (Re)pensar o Ensino das Ciências (pp. 13–18). A. Veríssimo, M. A. Pedrosa, & R. Ribeiro, Coordinator.Ministério da Educação—Departamento do Ensino Secundário. [Google Scholar]

- Erduran, S., Masri, Y., Cullinane, A., & Ng, Y. (2020). Assessment of practical science in high stakes examinations: A qualitative analysis of high performing English-speaking countries. International Journal of Science Education, 42(9), 1544–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadzil, H., & Saat, R. (2019). The development of a resource guıde in assessıng students’ scıence manıpulatıve skılls at secondary schools. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 16(2), 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S., & Morais, A. (2014). Conceptual demand of practical work in science curricula: A methodological approach. Research in Science Education, 44(1), 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K. M., & Wickman, P. O. (2013). Student engagement with artefacts and scientific ideas in a laboratory and a concept-mapping activity. International Journal of Science Education, 35(13), 2254–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M. (2016). Making practical work work: Using discussion to enhance pupils’ understanding of physics. Research in Science and Technological Education, 34(3), 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, A., & Squires, V. (2024). Bridging perspectives: Utilizing interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to inform and enhance social interventions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23, 16094069241306284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, J., Rannikmäe, M., & Soobard, R. (2020). STEAM Education—A transdisciplinary teaching and learning approach. In B. Akpan, & T. Kennedy (Eds.), Science Education in Theory and Practice: An introductory guide to learning theory (pp. 465–477). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzek-Greulich, H., & Vollmer, C. (2017). Emotional and motivational outcomes of lab work in the secondary intermediate track: The contribution of a science center outreach lab. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 54(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpin, T., Juuti, K., & Lavonen, J. (2014). Learning to apply models of materials while explaining their properties. Research in Science and Technological Education, 32(3), 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, J. (2004). L’entretién compréhensif (4th ed.). Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, D. (2013). The role of investigations in promoting inquiry-based science education in Ireland. Science Education International, 24(3), 282–305. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1022335 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Köksal, E. (2018). Self-efficacy beliefs of pre-service science teachers on fieldtrips. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, L. (2001). Contributos para uma utilização mais fundamentada do trabalho laboratorial no ensino das ciências. In Cadernos Didáticos de Ciências 1 (pp. 79–97). H. V. Caetano, & M. G. Santos, Organizer.Ministério da Educação—Departamento do Ensino Secundário. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D., Newcombe, P., & Stumpers, B. (2013). Evaluation of the use of remote laboratories for secondary school science education. Research in Science Education, 43(3), 1197–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, S., & Rohini, R. (2017). Problems faced by the physical science teachers in doing practical work in higher secondary schools at Aranthangi educational district. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 6(1), 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamlok-Naaman, R., & Barnea, N. (2012). Laboratory activities in Israel. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 8(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G., Gomes, C., Brocardo, J., Pedroso, J., Carrillo, J., Silva, L., Encarnação, M., Horta, M., Calçada, M., Nery, R., & Rodrigues, S. (2017). Perfil dos alunos à saída da escolaridade obrigatória. Direção-Geral da Educação, Ministério da Educação. Available online: https://dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Projeto_Autonomia_e_Flexibilidade/perfil_dos_alunos.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Mkimbili, S. T., & Ødegaard, M. (2019). Student motivation in science subjects in Tanzania, including students’ voices. Research in Science Education, 49(6), 1835–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musasia, A., Abacha, O., & Biyoyo, M. (2012). Effect of practical work in physics on girls’ performance, attitude change and skills acquisition in the form two-form three secondary schools’. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(23), 151–166. Available online: http://ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_23_December_2012/18.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Musasia, A., Ocholla, A., & Sakwa, T. (2016). Physics practical work and its influence on students’ academic achievement. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(28), 129–134. Available online: http://www.iiste.org (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Oguoma, E., Jita, L., & Jita, T. (2019). Teachers’ concerns with the implementation of practical work in the physical sciences curriculum and assessment policy Statement in South Africa. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 23(1), 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H., & Bonito, J. (2023). Practical work in science education: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1151641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyoo, S. (2012). Language in science classrooms: An analysis of physics teachers’ use of and beliefs about language. Research in Science Education, 42(5), 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phaeton, M., & Stears, M. (2017). Exploring the alignment of the intended and implemented curriculum through teachers’ interpretation: A case study of A-level biology practical work. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(3), 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pols, C., Dekkers, P., & de Vries, M. (2021). What do they know? Investigating students’ ability to analyse experimental data in secondary physics education. International Journal of Science Education, 43(2), 274–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal. (2018a, July 6). Decreto-Lei no. 54/2018, 6 de julho. Establishes the framework for inclusive education. Diário da República, Lisboa. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/EEspecial/dl_54_2018.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Portugal. (2018b). Decreto-Lei no. 55/2018, Diário da República n.o 129/2018, Série I de 06/07/2018 2928. Available online: https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/115652962 (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Portugal. (2018c). Portaria n.º 223-A/2018, de 3 de agosto. Regulates the educational and training offerings in basic education. Diário da República, 1.ª série, n.º 149, 3 ago. Available online: https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/115886163/details/maximized (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Preethlall, P. (2015). The relathionship between life sciences teacher’s knowledge and beliefs about science education and the teaching and learning of investigative practical work [Doctoral dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10413/14035 (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Ramnarain, U., & de Beer, J. (2013). Science students creating hybrid spaces when engaging in an expo investigation project. Research in Science Education, 43(1), 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparanganda, F., Rwodzi, M., & Mukundu, C. (2013). Project approach as an alternative to regular laboratory practical work in the teaching and learning of biology in rural secondary schools in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Education and Information Studies, 3(1), 13–20. Available online: http://www.ripublication.com/ijeis.htm (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Sani, B. (2014). Exploring teachers’ approaches to science practical work in lower secondary schools in Malaysia [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shana, Z., & Abulibdeh, E. S. (2020). Science practical work and its impact on students’ science achievement. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 10(2), 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R., & Abrahams, I. (2020). Secondary school students’ attitudes to practical work in biology, chemistry and physics in England. Research in Science and Technological Education, 38(1), 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sund, P. (2016). Science teachers’ mission impossible? A qualitative study of obstacles in assessing students’ practical abilities. International Journal of Science Education, 38(14), 2220–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šorgo, A., & Špernjak, A. (2012). Practical work in biology, chemistry and physics at lower secondary and general upper secondary schools in Slovenia. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 8(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, G., Lykknes, A., & Kvittingen, L. (2014). Small-scale chemistry for a hands-on approach to chemistry practical work in secondary schools: Experiences from Ethiopia. African Journal of Chemical Education, 4(3), 48–94. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Small-scale-chemistry-for-a-hands-on-approach-to-in-Tesfamariam-Lykknes/e76e4ee6a17e14c0d439fdeca13a4a4f586cdf8c (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Toplis, R. (2012). Students’ views about secondary school science lessons: The role of practical work. Research in Science Education, 42(3), 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2012). International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Available online: https://www.uis.unesco.org/en/methods-and-tools/isced (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Viswarajan, S. (2017). GCSE practical work in English secondary schools. Research in Teacher Education, 7(2), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B., Chen, S., & Chen, B. (2019). An investigation of sources of science teachers’ practical knowledge of teaching with practical work. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(4), 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B., & Li, X. (2017). Exploring science teachers’ perceptions of experimentation: Implications for restructuring school practical work. International Journal of Science Education, 39(13), 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B., & Liu, H. (2018). An experienced chemistry teacher’s practical knowledge of teaching with practical work: The PCK perspective. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 19(2), 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. (2018). The development, implementation, and evaluation of Labdog—A novel web-based laboratory response system for practical work in science education [Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton]. University of Southampton Institutional Repository. Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/418168/ (accessed on 18 January 2016).

- Xu, L., & Clarke, D. (2012). Student difficulties in learning density: A distributed cognition perspective. Research in Science Education, 42(4), 769–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.