Abstract

Across the globe, as countries implement policies and programs to increase college enrollment of youth to increase their workforce outcomes, a recently implemented education policy in Texas instead centers the student in selecting career pathways right out of high school. This paper explores the relationship between career-focused graduation plans and workforce outcomes of the 40% of Texas public school youth who do not continue into higher education. Through access to a statewide, individual-level data repository, this research produces a thorough descriptive analysis of the workforce outcomes of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education and estimates relationships between workforce outcomes and career-focused high school graduation plans. Our findings indicate that early in their implementation, career-focused graduation plans demonstrate no relationship to workforce outcomes for high school graduates who do not continue into higher education. We further found a declining trend in workforce participation for youth with only a high school credential. In conclusion, we recommend revising current graduation pathways to reinstate the requirement for higher-level mathematics courses across all graduation plans, while also ensuring that every student has access to these advanced math opportunities during high school.

1. Introduction

For the past 30 years, the American workforce has increased the educational requirements of the labor force, creating an economic divide among those with and without a college education (Autor et al., 2020). Similar trends can be observed in the four largest European economies, where the returns to college-level education were over 10% higher than the returns to lower secondary education (Anghel & Lacuesta, 2025). In 2020, those with a bachelor’s degree in the U.S. earned more than 1.5 times that of those with only a high school diploma, and those with advanced degrees earned more than twice the wages of those with only a high school diploma (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). As of 2022, only 37% of Americans aged 25 and older held a bachelor’s degree (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023), compared to an average of 41.2% of adults in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries who had completed tertiary education, as of 2024 (OECD, 2024). This means that approximately 63% of Americans 25 years or older without higher education will likely struggle to earn living wages, experience higher rates of unemployment, and be the last to recover from economic shocks like those created by the pandemic (Carnevale et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2021). Similarly, in OECD countries, about 59% of adults in the same age group without tertiary education would earn lower wages and experience relatively stagnant income growth over time (Anghel & Lacuesta, 2025; OECD, 2024).

To address the challenges of an underprepared workforce, several global policies and programs have been implemented. For example, the European Union set a target for at least 40% of individuals aged 30–34 to complete tertiary education by 2020 (Dragomirescu-Gaina et al., 2015). Similarly, many OECD countries have increased investments in both tertiary and vocational education to enhance workforce readiness (Sahnoun & Abdennadher, 2022). On the other hand, the U.S. federal government and many states have embraced the role of public education as the first of two levels of education necessary for successful workforce development and have enacted policies aimed at ensuring high school graduates are well prepared for higher education (Balfanz et al., 2016; Nettles, 2017). Over the past several decades, high school graduation requirements have been structured to support higher education attainment by increasing the number of courses required for graduation (Planty et al., 2007), raising academic standards (Balfanz et al., 2016), increasing curricular intensity (Austin, 2020), and incorporating career and technical education into college-ready pathways (Brand et al., 2013).

In this paper, we focus on Texas, where a recent policy stands as a contrasting narrative to this global and national focus on higher education preparation. House Bill (HB) 5, codified in 2013, redesigned the previous system of a default college-ready graduation plan requiring four courses in each of four core subject areas (referred to as a “4 × 4”) to the Foundation High School Program (FHSP), a minimal foundation plan supplemented with students’ choices of one of five career-focused graduation plans (called “endorsements”) with additional course requirements. The bill also reduced the number of exit-level exams students are required to pass for graduation, with the remaining exams being those of lower-level courses. In a notable departure from the previous college-ready 4 × 4 graduation plans, the FHSP graduation requirements minimize the core courses required for graduation and center the student in selecting career pathways and courses through the endorsement. Instead of requiring students to formally opt out of a college-ready plan, the new plan requires students to opt in to a selection of college-focused courses should postsecondary education be necessary to achieve their career outcomes (Mellor et al., 2017).

Across the state of Texas, preliminary and ongoing research continues to illuminate the ways in which the FHSP has influenced high school course-taking and post-secondary enrollment and attendance (Holzman & Lewis, 2020; Mansell & Kirksey, 2023; Mellor et al., 2017; Terry et al., 2016). On the other hand, the relationship between graduation plans and workforce outcomes of the more than 40% of Texas high school graduates who do not continue into higher education remains understudied. The purpose of this research is to explore the workforce outcomes of the youth left out of existing research. This study uniquely contributes to the literature base as it explores the possibility of high schools as institutions of workforce development for youth. This study is guided by the following research question: To what degree are high school graduation plans related to workforce outcomes1 for graduates who do not continue into higher education?

Through access to a statewide, individual-level data repository that allows students to be followed from their entry into public education through higher education and into the workforce, this research produces a thorough descriptive analysis of the workforce outcomes of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education. Moreover, we employ production function estimates to demonstrate the relationships between workforce outcomes and high school graduation plan selection.

Conceptual Framework

Operationalizing the high school diploma as a crucial piece of human capital accrued on the pathway to educational attainment and economic independence, we are guided by human capital theory (Becker, 2009). For our study, we focus our human capital lens on the formal education attained in schools and its relationship with workforce earnings. The Texas high school diploma plan endorsement aligns with four distinct areas of the workforce and signals specific education attained within each, which we are operationalizing as human capital to be leveraged in the workforce for earnings (workforce outcomes). As demonstrated by a rich research base, a positive relationship between educational attainment and workforce earnings has persisted over time (e.g., Harmon et al., 2003; Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2018). In contrast to this research base, Texas’s efforts to align high school graduation requirements to workforce participation directly were intended to provide opportunity for students to leverage their workforce-specific high school graduation plan as human capital to acquire employment with living wages without continuing into higher education or specialized training after high school (Texas Legislature, 2013).

In addition to considering the historic positive association between educational attainment and workforce outcomes, our conceptual framework considers the complex interactions of individual characteristics and educational characteristics within American society as influential factors for workforce earnings. We know that individual and familial characteristics like socioeconomic status (e.g., Chetty et al., 2014), English language proficiency (e.g., Bleakley & Chin, 2004), and race or ethnicity (e.g., Chetty et al., 2020) are related to workforce earnings at each level of educational attainment. Additionally, high school characteristics such as school quality and resources (e.g., Card & Krueger, 1992; Chetty et al., 2011) and characteristics of the higher education institution attended (e.g., Zhang, 2005) also contribute to workforce earnings. Finally, societal aspects of racial discrimination (e.g., Carnevale & Strohl, 2013) and gender discrimination (e.g., Hu & Wolniak, 2013) are well-known factors that influence workforce earnings.

In our quantitative study, we combine human capital theory and the associated vast research base outlining factors related to workforce earnings (Bleakley & Chin, 2004; Card & Krueger, 1992; Carnevale & Strohl, 2013; Chetty et al., 2020; Hu & Wolniak, 2013; Zhang, 2005) to shape our analytic approach and contextualize our findings into the modern education systems and workforce. In the statewide data system used in this study, our outcome variable is constructed from reported earnings. Our covariate of interest is human capital, which is reflected by variables that indicate the high school graduation plan of each student. As established in previous research, individual and familial characteristics indicated by variables for race and ethnicity, English language learner status, and socioeconomic status and included in our analysis as important covariates. Also, to reflect the wide range of industries represented in the dataset, we also include a covariate indicating the industry in which an individual was employed. High school characteristics and the social aspects of racial and gender discrimination were not explicitly examined in this study and are discussed in the Limitations section. Our study explores how the new career-focused graduation plans may be related to individuals’ access to better economic opportunities.

2. Background

While U.S. education systems are governed by state constitutions, globalization and the push for nationwide competitiveness have prompted federal involvement in shaping the quality and equity of state graduation requirements (Goertz, 2005; McGuinn, 2006; Thomas & Brady, 2005). Concurrent to concerns over globalization, the technological shift of the American workforce demanded more workers with higher education (Goldin & Katz, 2008), and public scrutiny of schools continued to contrast the performance of American students against those from other nations and to highlight disparate performance among students of different socioeconomic statuses (Dalton et al., 2007). In 2001, the federal government adopted the No Child Left Behind Act to hold states and schools accountable for increasing overall academic performance and decreasing inequity. The act mandated strict standards for assessment and accountability for all schools and education agencies that received federal funding (McGuinn, 2006) and mandated graduation requirements to ensure standardization and a minimum level of rigor (Schiller & Muller, 2003). Research has documented the role of federal accountability in increasing the number of courses required for graduation (Planty et al., 2007), positively influencing students’ mathematics course-taking (Schiller & Muller, 2003), and encouraging state policies aimed at ensuring high school graduates were well prepared for higher education (Balfanz et al., 2016; Nettles, 2017).

With the job losses and economic downturn of 2008, the federal government highlighted how education could bolster the country’s wavering economy (Palmadessa, 2017). The Obama administration spearheaded the enhancement of the newly created Common Core State Standards (CCSS)2 through the Race to the Top3 federal grant program, which focused on academically preparing students for postsecondary success by aligning all facets of curriculum toward critical reading, writing, communications, and mathematical reasoning skills. This included breaking down the typically siloed career- and college-ready pathways (Brand et al., 2013; Pearson, 2015). The adoption of CCSS and related testing accountability measures varied from state to state, with some states, such as Texas, refusing adoption altogether (Edgerton, 2020). However, in 2015, Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which mandated that all states create educational plans that aligned academic achievement standards with entrance requirements for credit-bearing coursework in the state’s institutes of higher education and that states develop workforce-aligned career and technical education standards (ESSA, 2015). The federal education policies adopted over the past 40 years encouraged (and at times mandated) state education systems to align curricula and course-taking with the ultimate goal of college readiness. It is within this context that Texas shifted focus away from college readiness toward career pathways with HB5.

Texas Policy and Graduation Requirements

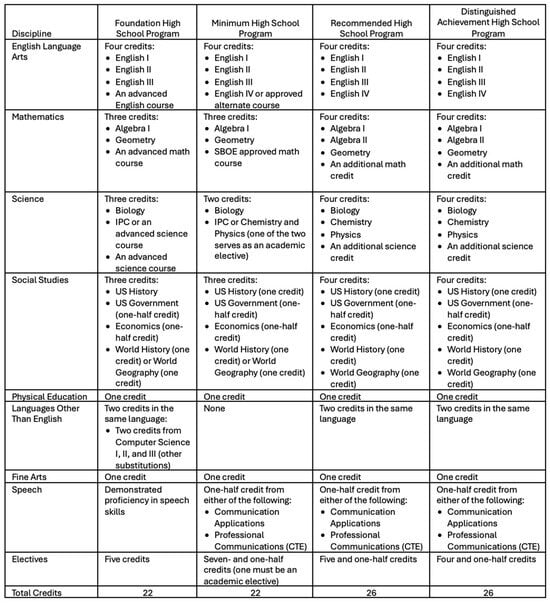

Prior to 2013, Texas graduation requirements were designed primarily to ensure that students completed the coursework and standardized testing necessary to gain admission to four-year colleges and universities (Mellor et al., 2017). These graduation requirements, introduced in 2006, placed all Texas high school students on the Recommended High School Program (RHSP), or 4 × 4 plan, which required successful completion of four credits each of the four core subjects: mathematics, English language arts, science, and social studies (see Figure 1). Students seeking a higher standard could opt into the Distinguished Achievement High School Program (DAHSP), and only after formal permission was granted by the school district and parent (or adult student) could students opt into the lesser 22-credit Minimum High School Program (MHSP)—a program that did not provide the coursework necessary for college entrance. All programs mandated passing four core subject exit-level state standardized exams in the 11th grade (TEA, n.d.).

Figure 1.

Comparison of graduation programs.

In part to increase the college readiness of Texas students, the state also transitioned its standardized testing from the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) to the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STARR®) in 2012. Statewide poor performance on the more rigorous STAAR tests and a business sector unimpressed with the skills of the labor force prompted many to question the rationale and motive of the new STAAR tests, and in response, in 2013, the legislature passed HB5 (Texas Legislature, 2013).

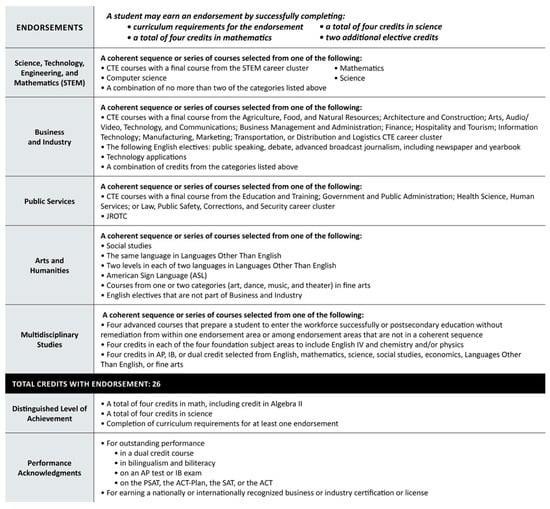

The intent of HB5 was to reform graduation requirements to support labor demands, reduce the state’s focus on standardized testing, and foster student career choice (Texas Legislature, 2013). The bill established the Foundation High School Program (FHSP), which replaced the previous graduation requirements and was designed to give students more flexibility to take classes aligned with their interests and career goals and reduce the number of standardized tests required for graduation from 15 to five (TEA, 2020). As part of the FHSP, prior to entry into the 9th grade, all students select one of five career-focused pathways for coursework, called endorsements: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); public service; business and industry; arts and humanities; or multidisciplinary studies (TEA, n.d.). Most notably, the new FHSP changed the system from one in which all students were placed on a college-ready track by default to a system where students had to opt in to the college-ready track or could choose paths that would not provide them with the course requirements necessary for higher education. Students need to earn the Distinguished Level of Achievement, in addition to the selection of an endorsement, to be admitted to a four-year Texas college or university through Texas’s Top Ten Percent automatic admission law (TEA, 2020).

Figure 1 highlights the main differences between the current foundation program (FHSP) and the previous Minimum (MHSP), Recommended (RHSP), and Distinguished Achievement (DAHSP) high school programs. As indicated, HB5 lowered the total number of credits needed for graduation when it created the FHSP. The FHSP also gives students the ability to use computer science to satisfy the two “Language Other Than English” credits. By eliminating the previous tiered options, the FHSP decreased the number of credits in mathematics, science, and social studies and offered students the flexibility to add the higher-level courses through career-focused endorsement programs that were of personal interest (see Figure 2). Outstanding credentials such as advanced placement (AP) or international baccalaureate (IB) course-taking, dual credit, and bilingualism are noted on students’ high school transcripts. However, it is nonetheless possible for the substantive changes to students’ course-taking to be minimal: The FHSP graduation plan without an endorsement is similar to the previous MHSP, and the FHSP graduation plan with a multidisciplinary endorsement looks quite similar to the previous RHSP. Ostensibly, student course requirements before and after the FSHP could vary little.

Figure 2.

Foundation high school program endorsements.

This research examines the shift from a universal college-readiness pathway to one where college preparation is offered as an option in Texas. We explore how this change—occurring at a time when a college education is increasingly critical for long-term economic stability—affects the workforce outcomes of youth who do not pursue higher education. Based on these policy shifts, we expect to observe variations in workforce earnings across endorsement types.

3. Data and Methods

This study was conducted using the statewide data repository housed at the University of Houston Education Research Center. Dataset construction in STATA began with a TEA dataset of graduates4 of Texas public high schools from the 2010–2011 through 2020–2021 school years. For the purposes of this study, we define graduates who did not continue into higher education as a student who, as of 2022, had not (1) enrolled in a dual-credit course in high school, (2) enrolled in a postsecondary institution, (3) received an industry certificate from a postsecondary institution, (4) received an associate degree, or (5) received a bachelor’s degree or higher. The dataset of Texas public high school graduates whose highest level of education was high school contained variables representing the high school from which the student graduated, courses taken throughout their high school career, endorsements, demographic characteristics of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, English language proficiency, and special education services participation.

The dataset of high school graduates was cross-referenced with Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board data to determine higher education enrollment between 2011 and 2022. A binary variable indicating enrollment in higher education was created for each high school graduate. Texas Workforce Commission data, including quarterly wages and employment sector from 2011 to 2022, were added to the dataset. The industry area of employment is from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code, which indicates the sector of employment but not the job description of the position within the sector. To calculate the annual wage, individual quarterly wages were added. Because the data do not contain a measure of time worked, the dataset was narrowed to exclude annual wage outliers reported beyond 3 standard deviations of the mean annual income each year. Finally, all wage data were converted to constant 2022 dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

In summary, the dataset analyzed in this study was created from the entire population of Texas high school graduates. The statewide data repository used in this analysis provides a unique identifier for each individual consistent across all three datasets (K-12, higher education, and workforce). For individuals with more than one reported high school graduation, the first graduation was kept. High school graduates with no workforce data were assumed to have no workforce earnings reported as W2 wages. As the relationship between the FHSP degree plans was the focus of this study, students who graduated under degree plans not explicitly a part of the FHSP were excluded from the study. Students who graduated with a diploma plan determined by special education services were excluded from the study and represented 0.79% of the entire population of Texas high school graduates between 2011 and 2021 (see Table 1). Additionally, in line with previous research using workforce earning data (e.g., Hanushek et al., 2017), less than 2% of the remaining population was excluded from the dataset analyzed as their wage variables fell outside of 3 standard deviations of the mean and were likely reported in error.

Table 1.

Total Texas public high school graduates and high school graduates with no higher education as of 2022, Class of 2011 through Class of 2021.

This research sought to document the sector employment and wage earnings of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education and the relationship between workforce outcomes and graduation plans. In order to document the wide variance that exists within the Texas workforce, we employed a range of descriptive statistics. Additionally, we drew from the rich literature base surrounding the study of wage outcomes to understand the influence of high school course-taking on wage outcomes through a modified version of the Mincer (1974) equation. The log wage function used takes the following general form:

In this equation, the dependent variable of interest is ln wage, which refers to the natural log of wages reported for each individual, i, from each class of graduates, t. The log wage function does not take the true Mincer form, as experience is not an explicit variable in the model, but instead approximated by the year after graduation (t) variable and squared by the year variable in the equation due to the nonlinear relationship between experience and wages. Because our workforce data do not have the detail to allow us to determine the specific job role of individuals in the dataset, the experience variable is limited to the years of possible experience in the workforce following high school graduation. The variable C represents a vector of upper-level and career-focused courses taken by the graduate. The variable X is a vector of student characteristics that includes race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and the highest math course taken. The sector of employment is represented by the variable S.

Specific covariate selection was made by a correlation analysis between the outcome and covariate variables. The final ordinary least squares model was selected by comparing the Wald chi2 statistic of the base model, including only experience as a covariate, to models increasingly including additional covariates. Post-estimation, residuals produced from the model were assessed for normality, and kernel distribution plots were used to compare actual to predicted values to assess goodness of fit. The variance inflation factor was assessed to be near 2, indicating no substantial multicollinearity.

4. Results

To understand the relationship between graduation plans and workforce earnings, our analysis began with a description of the subgroup of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education compared with the total population of high school graduates. Then, the graduation plans, sector of employment, and average wages were described before estimating the log wage function model.

4.1. Texas High School Graduates with No Higher Education

Table 1 displays the total number of Texas public high school graduates from 2011 to 2021, with the number and percentage of those graduates who did not pursue post-secondary education as of 2022. In 2011, 290,220 students graduated from Texas public high schools, and as of 2022, 119,186 (41%) had not obtained any post-secondary education. As shown in Table 1, since 2011, the percentage of students from each high school graduating class who do not continue to higher education has increased. This should be interpreted with care, as there is the possibility that the more recent graduates (e.g., the Class of 2021) could enroll in higher education after 2022, the last year of data captured in this analysis.

Table 2 reports the percentage of graduates and the percentage of those who did not continue into higher education by race and ethnicity and special populations. Compared with the racial and ethnic makeup of all high school graduates, the group of students who did not continue into higher education has larger proportions of Black and Hispanic students (χ2 (6, N = 5,905,790) = 13,723, p < 0.05). This finding is consistent with national analyses demonstrating higher educational attainment among White and Asian adults (Carnevale et al., 2023) and research that has shown that historically marginalized populations (Garibaldi, 2014), English language learners (Flores et al., 2012), and special education graduates (Shaw et al., 2009) are underrepresented in higher education.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Texas graduates and Texas graduates with no higher education as of 2022, Class of 2011 through Class of 2021.

4.2. Graduation Plans

Under the previous graduation plan in place for students entering high school prior to 2015, 68% of graduates who did not continue into higher education graduated with the Recommended version of the plan, while approximately 10% graduated with the Distinguished plan and approximately 20% graduated with the Minimum plan. Graduation under the Recommended or Distinguished plans provided students with the prerequisite coursework for higher education enrollment, indicating that only 20% of graduates under the previous graduation plans left high school without the coursework needed for immediate higher education enrollment.

Since the implementation of the FHSP in 2015, 29% of high school graduates who did not continue into higher education graduated with no endorsement (22 credits), and 45% of high school graduates who did not continue into higher education graduated with the multidisciplinary endorsement (26 credits).5 The most common endorsement of students who did not continue into higher education was the multidisciplinary endorsement, which could be the result of permission granted to schools to offer only the multidisciplinary endorsement, rather than a reflection of student choice. Across the dataset of high school graduates who did not continue into higher education, the public service endorsement (11% of graduates) and the STEM endorsement were the least common selections. Many graduates (37%) who did not continue into higher education graduated under the FHSP with more than one endorsement. Unlike graduation under the previous Recommended or Distinguished graduation plans, graduation under the FHSP with an endorsement does not indicate that students have taken Algebra 2, a course consistently found to be key in higher education success (Blankenberger et al., 2017; Long et al., 2012; Woods et al., 2018).

4.3. Employment and Wages

Table 3 displays the sector of employment and average wages for high school graduates who did not continue into higher education five years after graduation.6 In their first year of employment, almost 60% of the 594,490 high school graduates who did not continue into higher education were employed in the accommodation/food service (181,504) or retail trade (169,162) sectors and reported average annual earnings of $13,378 and $14,741, respectively. High school graduates who did not continue into higher education employed in the construction ($28,888), utilities ($34,309), and mining/oil and gas ($40,885) sectors reported the highest earnings in their first year in the workforce; however, they represented a much smaller proportion of the total number of graduates.

Table 3.

First- through fifth-year sector employment and annual wages for graduates with no higher education, Class of 2011 through Class of 2021.

Table 3 also shows that five years after high school graduation, 376,036 high school graduates who did not continue on to higher education were found in the workforce.7 By year 5, the graduates with no higher education employed in the accommodation/food service (59,727) and retail trade (74,106) sectors decreased, and average annual earnings reported increased to $19,924 and $25,000, respectively. Employment of high school graduates who did not continue into higher education increased most in the education (18,166; $29,670), professional, scientific, and technical services (17,793, $41,972), and finance/insurance (11,425; $40,436) sectors. As was the case in first-year employment, the construction ($43,103), utilities ($59,712), and mining/oil and gas ($59,759) sectors reported the highest earnings for graduates in their fifth year in the workforce, but represented a decreasing proportion of the workforce.

Of concern in the five-year employment trends of students who do not continue into higher education is their decreasing participation in the workforce. While the dataset evaluated for this study is limited in its exclusion of gig-economy jobs such as contract work, decreased participation in the workforce could signal difficulty in finding employment. Of those students who remained employed in the workforce five years after high school graduation, 35% remained employed in sectors that reported annual wages equal to or less than $25,000, and only a small proportion of graduates earned wages over $50,000 per year. Considering these earnings in the context of modern cost-of-living estimates (Carnevale et al., 2023), this evidence suggests a limited ability for high school graduates without higher education to live and support families—a finding at odds with the goals of the FHSP.

4.4. Connecting FHSP Graduation Plans and Wages

To understand the FHSP as a graduation plan aligned with career outcomes, this analysis connects its plan types to wages using a random effects log-wage function commonly employed in workforce outcome literature. The results of the regression-based analysis are displayed in Table 4. The natural log of annual wages serves as the outcome variable for the model that analyzed the FHSP endorsements and industries, while controlling for characteristics known to influence workforce outcomes such as gender, race and ethnicity, and years of experience in the workforce.

Table 4.

Regression results for wages, foundation high school program graduates, Class of 2011 through Class of 2021.

The years of experience in the workforce were positively related to wages earned (β = 0.021; p < 0.05). Among high school graduates who did not continue into higher education and graduated under the FHSP, women (β = −0.238; p < 0.05) and graduates who identified as Asian (β = −0.208; p < 0.05), Black (β = −0.257; p < 0.05), and White (β = −0.094; p < 0.05) demonstrated negative associations with annual wages. Hispanic (β = 0.114; p < 0.05) graduates who did not continue into higher education demonstrated positive associations with annual wages.

4.5. FHSP Endorsements

For high school graduates who did not continue into higher education, graduating under the FHSP with a business endorsement (β = 0.103; p < 0.05), a public service endorsement (β = 0.085; p < 0.05), or a distinguished endorsement (β = 0.025; p < 0.05) was positively associated with wages earned. Conversely, high school graduates who did not continue into higher education and graduated with no endorsement (β = −0.085; p < 0.05), a STEM endorsement (β = −0.139; p < 0.05), an arts and humanities endorsement (β = −0.011; p < 0.05), or a multidisciplinary endorsement (β = −0.050; p < 0.05) demonstrated negative associations with wages. The negative association with multidisciplinary endorsement is especially concerning since 45% of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education graduate with the multidisciplinary endorsement, and it is the default endorsement for school districts. Notably, controlling for endorsement, coursework at or beyond the Algebra 2 level was positively associated with wages (β = 0.047; p < 0.05), reiterating the importance of higher-level math coursework under any endorsement plan.

4.6. Industry of Employment

Table 4 also displays the relationship between industry of employment and wages earned. Controlling for personal characteristics and the type of FHSP endorsement earned, compared with employment in the construction industry—an industry of modest employment and earnings—employment in the mining/oil/gas (β = 0.060; p < 0.05), utilities (β = 0.235; p < 0.05), and public administration industries (β = 0.117; p < 0.05) were the only industries of employment to demonstrate positive relationships with earnings. As demonstrated in Table 3, relatively small numbers of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education are employed in these industries. All other industries of employment were negatively associated with wages in comparison to the construction industry, including the largest industries of employment: accommodation/food service (β = −0.480; p < 0.05) and retail trade (β = −0.364; p < 0.05).

5. Discussion

This analysis of the workforce employment and outcomes of the population of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education corroborates previous research investigating educational attainment as a form of human capital (e.g., Harmon et al., 2003; Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2018), as most who did not continue into higher education were employed in low-wage jobs during their first five years in the workforce. Despite the efforts of Texas policymakers to align high school graduation plans to specific areas of the workforce, this research found that high school graduates who did not continue into higher education were employed in low-wage jobs predominantly in the retail and food service sectors. Reflecting the findings of previous research on the influence of individual characteristics on educational attainment (Chetty et al., 2014, 2020), our research found the overrepresentation of graduates of color and graduates of low socioeconomic status among students who did not continue into higher education. Moreover, each year, a decreasing number of high school graduates who did not continue into higher education participated in the workforce. The decline in workforce participation reported for youth with a high school credential who did not continue into higher education between their first and fifth years in the workforce illuminates a troubling trend. While the data for this analysis is limited to employment reported through the state unemployment insurance system and excludes gig-economy and contract jobs, decreased participation in the reported workforce is concerning, given the comparable instability and lack of workforce benefits associated with gig-economy and contract jobs. Declining participation could also signal increased difficulty that this youth might be facing in finding and maintaining employment without higher education.

Concerningly, many high school graduates who do not continue into higher education are employed in the retail trade and accommodation/food service industries and earn far less than living wages five years after high school graduation (Carnevale et al., 2023). Little evidence in the first seven years of implementation indicates that the endorsement pathways offered under the FHSP provide preparation and training that lead to living-wage earnings of high school students who do not continue into higher education. Stated differently, the high school diplomas with endorsement pathways have provided no discernible differences in human capital. The less commonly selected public service, business, and distinguished endorsements were the only endorsements to demonstrate a positive association with workforce earnings. The multidisciplinary endorsement’s negative association with wages is an area of great opportunity for improvement, as 45% of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education graduated with that endorsement. Furthermore, the lack of higher-level math and science course requirements in many of the endorsements under the FHSP could deter students from continuing into higher education. After graduation, students without higher-level math courses could find they would not meet the minimum performance requirements of some colleges or that they need to take additional math courses in higher education. These additional barriers to higher education could be preventing many students from attaining the human capital necessary for economic independence.

One area of potential opportunity lies within the public service and business endorsements. Though the endorsements were not widely chosen by students, the industries of employment that were positively associated with wages (e.g., mining/oil/gas, utilities, and public administration) could be supported by specific coursework in the public service or business endorsements. Providing human capital attainment opportunities to students by developing a sector-specific set of skills through pathways offered in the public service or business endorsement could provide pathways to living-wage careers that do not require higher education could provide more opportunity to students seeking to enter the workforce immediately after high school graduation.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the FHSP endorsements are not yet fully developed as human capital to be leveraged for living-wage jobs. Importantly, this study also emphasizes the importance of returning the requirements of higher-level math courses to all graduation plans and ensuring all students have the opportunity to take higher-level math courses in high school.

Limitations and Future Research

The regression analysis conducted in this study serves as an exploratory study of the wage outcomes of high school graduates who do not continue into higher education. This study included higher education data through 2022 and, as such, does not account for the possibility of high school graduates enrolling in higher education after 2022. This study does not control for structural effects or the characteristics of students’ high schools that could influence course-taking and graduation. The analysis is limited to high school implementation of the FHSP in the first seven years of implementation. While the study did analyze constant 2022 dollars, it does not account for geographical differences that exist in wage earnings across the state of Texas. Future research capturing the workforce earnings of individuals in gig-economy or contract jobs, in addition to regional workforce differences, would supplement this analysis and aid in a better understanding of the complete workforce outcomes within the state.

An important consideration this study does not fully consider is the influence of structural inequity within the educational system and its impact on course-taking, high school completion, and workforce outcomes (Garces & Gordon da Cruz, 2017; Schiller & Muller, 2003). Our results suggest that the FHSP may be tracking students into specific coursework or graduation pathways, subsequently increasing inequity within the public education system. We cautiously advise education policymakers to be increasingly aware of trends in educational pathways and workforce outcomes of students identifying as diverse and minoritized racial and ethnic groups, as well as students of low socioeconomic statuses. As demonstrated by the overrepresentation of these groups in high school graduates who do not continue into higher education, Texas high school graduation plan policies are contributing to the reproduction of long-standing inequalities of the public school system. Future research exploring the availability of course offerings across the diverse landscape of locally controlled Texas public schools could provide meaningful insight to understand the root of the problem of course-taking outcomes, and further exploration of graduation pathways and specific coursework that lead to living-wage jobs for students of color could provide additional insight into wage differences.

6. Conclusions

Human capital theory asserts a strong connection between educational attainment and workforce earnings (Becker, 2009), and at each level of educational attainment, individual, educational, and societal factors are influential (Bleakley & Chin, 2004; Card & Krueger, 1992; Carnevale & Strohl, 2013; Chetty et al., 2020; Hu & Wolniak, 2013; Zhang, 2005). Earning a living wage in the United States is increasingly dependent upon higher education credentials (Goldin & Katz, 2008). As much as federal and state education policy has shifted to prepare students for higher education, recent Texas policy focuses first on career alignment. HB5, codified in 2013, ushered in a career-aligned graduation plan system where students choose one of five different career pathways for coursework. While many have examined the higher education impacts of the new graduation plan (Mellor et al., 2017), this study fills a gap in the literature regarding the more than 40% of Texas youth with a high school credential who do not continue into higher education.

Through the analysis of workforce outcomes associated with graduation requirements and pathways, this research intends to inform policies and practices that best support the preparedness of youth who enter the workforce post attaining a high school credential. While higher education remains a primary driver of wage earnings, there are a large number of students who do not continue into higher education, and for them, the findings from this research and any future analyses remain an important component of improving the overall education system and economic future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.F. and T.T.; Methodology, T.T.; Software, M.F.; Formal analysis, M.F. and T.T.; Investigation, T.T.; Resources, E.M.-M.; Writing—original draft, T.T. and S.S.F.; Writing—review & editing, T.T. and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Houston Education Research Center in the College of Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Houston (STUDY00003807 exempted 18 August 2022) determined the study to be exempt from IRB approval. The study was exempted from IRB approval due to the use of anonymized data housed in the University of Houston Education Research Center.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data for this study are not available. The data for this research was individual-level, FERPA-protected data housed at the University of Houston Education Research Center. Researchers can attain access to the data repository after studies to evaluate education policy are approved by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. See https://www.uh.edu/education/research/institutes-centers/erc/ (accessed on 25 November 2025) for more detail regarding data access.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank Diana D’Abruzzo, Jeanette Narvaez, Sherri Lowrey, and Catherine Horn for their support of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FHSP | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| CCSS | Common Core State Standards |

| TEA | Texas Education Agency |

Notes

| 1 | In this paper, the term workforce outcomes refers to the quantifiable effects individuals experience following participation in educational, vocational training, or employment initiatives. These outcomes serve as indicators for evaluating the success of programs designed to enhance employability, support career development, and promote economic well-being (Amin et al., 2020; Shiferaw et al., 2024). |

| 2 | The Common Core State Standards, developed by state leaders in the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers in 2009, are academic standards for mathematics and English language arts and literacy that outline what students should know at the end of each grade level in order to succeed. For more information, see http://www.thecorestandards.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2025). |

| 3 | Race to the Top was an initiative launched in 2012 by the Obama administration to encourage the alignment of educational practices, standards, and policies to college readiness. For more information, see https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/issues/education/k-12/race-to-the-top (accessed on 25 November 2025). |

| 4 | Under the previous diploma program and under the FHSP, several diploma plans and high school completion options were available for students served by the special education program. Because the requirements of these plans can vary significantly from the diploma plans that are the focus of this analysis, students graduating under special education degree programs were removed from the dataset. |

| 5 | Policy mandates the graduation plans for students based upon their first year in ninth grade (TEA, n.d.), so the first cohort of ninth-graders to graduate under the FHSP would have been those in ninth grade in 2015, or the Class of 2018. However, HB5 provided an opportunity for students in high school when the bill was passed (2013) to elect to graduate under the FHSP, hence the small number of graduates under the FHSP in 2015, 2016, and 2017. School districts are not required to offer all endorsements. If one endorsement is offered, it must be the multidisciplinary endorsement (TEA, 2020). |

| 6 | Sector of employment represents what was reported in the first quarter of the calendar year. |

| 7 | The decreased number of graduates in the workforce by year 5 is partially attributed to the way in which the dataset is censored. The latest year of workforce data available was 2022. For example, data for only the first two years of the workforce were available for graduates from the Class of 2020, so they are not included in the data presented for years 3 to 5. |

References

- Amin, S., Kitmitto, S., Fagan, K., & Hester, C. (2020). A review of the evidence on youth and young adult workforce development programming. American Institutes for Research. [Google Scholar]

- Anghel, B., & Lacuesta, A. (2025). Wage returns to education in the four largest European economies. Banco de Espana Article, 3(2025), Q1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M. (2020). Measuring high school curricular intensity over three decades. Sociology of Education, 93(1), 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2020). Extending the race between education and technology. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfanz, R., DePaoli, J. L., Ingram, E. S., Bridgeland, J. M., Fox, J. H., & Hornig, J. (2016). Closing the college gap: A roadmap to postsecondary readiness and attainment. Civic Enterprises and Everyone Graduates Center at the School of Education at Johns Hopkins University. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED572785 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Becker, G. S. (2009). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberger, B., Lichtenberger, E., Witt, M. A., & Franklin, D. (2017). Diverse students, high school factors, and completion agenda goals: An analysis of the Illinois class of 2003. Education and Urban Society, 49(5), 518–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, H., & Chin, A. (2004). Language skills and earnings: Evidence from childhood immigrants. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B., Valent, A., & Browning, A. (2013). How career and technical education can help students be college and career ready: A primer. College & Career Readiness & Success Center at American Institutes for Research. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED555696.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (1992). School quality and black-white relative earnings: A direct assessment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(1), 151–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, A. P., Mabel, Z., Campbell, K. P., & Booth, H. (2023). What works: Ten education, training, and work-based pathway changes that lead to good jobs. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED628027.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Carnevale, A. P., & Strohl, J. (2013). White flight goes to college. Poverty & Race, 22(5), 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hilger, N., Saez, E., Schanzenbach, D. W., & Yagan, D. (2011). How does your kindergarten classroom affect your earnings? Evidence from Project STAR. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1593–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Jones, M. R., & Porter, S. R. (2020). Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 711–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1553–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, B., Ingels, S. J., Downing, J., & Bozick, R. (2007). Advanced mathematics and science coursetaking in the spring high school senior classes of 1982, 1992, and 2004. NCES 2007-312. National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497754.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Dragomirescu-Gaina, C., Elia, L., & Weber, A. (2015). A fast-forward look at tertiary education attainment in Europe 2020. Journal of Policy Modeling, 37(5), 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgerton, A. K. (2020). Learning from standards deviations: Three dimensions for building education policies that last. American Educational Research Journal, 57(4), 1525–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Every Student Succeeds Act, Public Law 114–95, 129 Stat. 1802. (2015).

- Flores, S. M., Batalova, J., & Fix, M. (2012). The educational trajectories of English language learners in Texas. Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Garces, L. M., & Gordon da Cruz, C. (2017). A strategic racial equity framework. Peabody Journal of Education, 92(3), 322–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, A. M. (2014). The expanding gender and racial gap in American higher education. The Journal of Negro Education, 83(3), 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, M. E. (2005). Implementing the No Child Left Behind Act: Challenges for the states. Peabody Journal of Education, 80(2), 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2008). Transitions: Career and family life cycles of the educational elite. American Economic Review, 98(2), 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Woessmann, L., & Zhang, L. (2017). General education, vocational education, and labor-market outcomes over the lifecycle. The Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 48–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, C., Oosterbeek, H., & Walker, I. (2003). The returns to education: Microeconomics. Journal of Economic Surveys, 17(2), 115–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzman, B., & Lewis, B. (2020). House Bill 5 and high school endorsements: How do they align to college admissions? Houston Education Research Consortium. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611116.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Hu, S., & Wolniak, G. C. (2013). College student engagement and early career earnings: Differences by gender, race/ethnicity, and academic preparation. The Review of Higher Education, 36(2), 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y. T., Park, M., & Shin, Y. (2021). Hit harder, recover slower? Unequal employment effects of the COVID-19 shock (No. w28354). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M. C., Conger, D., & Iatarola, P. (2012). Effects of high school course-taking on secondary and postsecondary success. American Educational Research Journal, 49(2), 285–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansell, K. E., & Kirksey, J. J. (2023). Shifts in advanced science course-taking and postsecondary and career pathways following Texas house bill 5. Texas Tech University College of Education Policy Brief. Available online: https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/handle/2346/93034/PB_Apr_5.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- McGuinn, P. (2006). No child left behind and the transformation of federal education policy, 1965–2005. University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, L., Stoker, G., & Muhisani, H. (2017). House bill 5 evaluation: Final report. American Institutes for Research. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED615738.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Mincer, J. A. (1974). The human capital earnings function. In Schooling, experience, and earnings (pp. 83–96). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Nettles, M. T. (2017). Challenges and opportunities in achieving the national postsecondary degree attainment goals. Educational Testing Service. Available online: https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/37720-Challenges-and-Opp-Exec-Summary.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- OECD. (2024). Population with tertiary education. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/population-with-tertiary-education.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Palmadessa, A. L. (2017). America’s college promise: Situating president Obama’s initiative in the history of federal higher education aid and access policy. Community College Review, 45(1), 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D. (2015). CTE and the common core can address the problem of silos. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(6), 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planty, M., Provasnik, S., & Daniel, B. (2007). High school coursetaking: Findings from the condition of education 2007 (NCES 2007-065). National Center for Education Statistics.

- Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. A. (2018). Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Education Economics, 26(5), 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahnoun, M., & Abdennadher, C. (2022). Returns to investment in education in the OECD countries: Does governance quality matter? Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(3), 1819–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, K. S., & Muller, C. (2003). Raising the bar and equity? Effects of state high school graduation requirements and accountability policies on students’ mathematics course taking. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(3), 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S. F., Madaus, J. W., & Banerjee, M. (2009). Enhance access to postsecondary education for students with disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(3), 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, L., Dolfin, S., & Streke, A. (2024). The Effects of Employment and Training Programs for Populations with Low Incomes: Evidence from the Pathways Clearinghouse. Journal of Labor Research, 45(3), 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, R., Gammon, H., Mullen, E., Dearmon, W., & Alexander, L. (2016). House bill 5: The new shape of Texas high school education. Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/187044/2016%20HB5%20TEGAC%20HB5%20Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Texas Education Agency [TEA]. (n.d.). State graduation requirements. Available online: https://tea.texas.gov/academics/graduation-information/state-graduation-requirements (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Texas Education Agency [TEA]. (2020). Graduation toolkit. Available online: https://tea.texas.gov/about-tea/news-and-multimedia/brochures/graduationtoolkit2020-english-website.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Texas Legislature. (2013). Bill analysis CSHB 5 by aycock. Available online: https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/83R/analysis/pdf/HB00005H.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Thomas, J. Y., & Brady, K. P. (2005). The elementary and secondary education act at 40: Equity, accountability, and the evolving federal role in public education. Review of Research in Education, 29, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Figure 10: Average earnings by education attainment as a proportion of the average earnings of high school graduates, 1975–2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/time-series/demo/fig_10.png (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). CPS historical time series tables. Table a-4. Detailed years of school completed by people 25 years and over: 2000 to 2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/educational-attainment/cps-historical-time-series.html (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Woods, C. S., Park, T., Hu, S., & Betrand Jones, T. (2018). How high school coursework predicts introductory college-level course success. Community College Review, 46(2), 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. (2005). Do measures of college quality matter? The effect of college quality on graduates’ earnings. The Review of Higher Education, 28(4), 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).