Architecture for Spatially Just Food System Planning with and for Urban Youth South Sudanese Refugees in Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualization

1.1.1. Conflict and Displacement in South Sudan

1.1.2. Refugees in Kenya

- A low loan availability rate: 40 percent of individuals access loans from friends and family, while only 1 percent receive loans from banks (Pape et al., 2021).

- Poor secondary school enrollment, with a net rate of 28 percent (31 percent for boys and 24 percent for girls) (Wangui & Kipchumba, 2024).

- Harassment from officials (Muindi & Mberu, 2019).

- Competition with locals for resources and employment (Muindi & Mberu, 2019).

- Previous education is often disregarded because employers are reluctant to recognize certifications from foreign schools (Okello, 2024).

1.1.3. Refugee Youth Health and Wellbeing Ecosystems

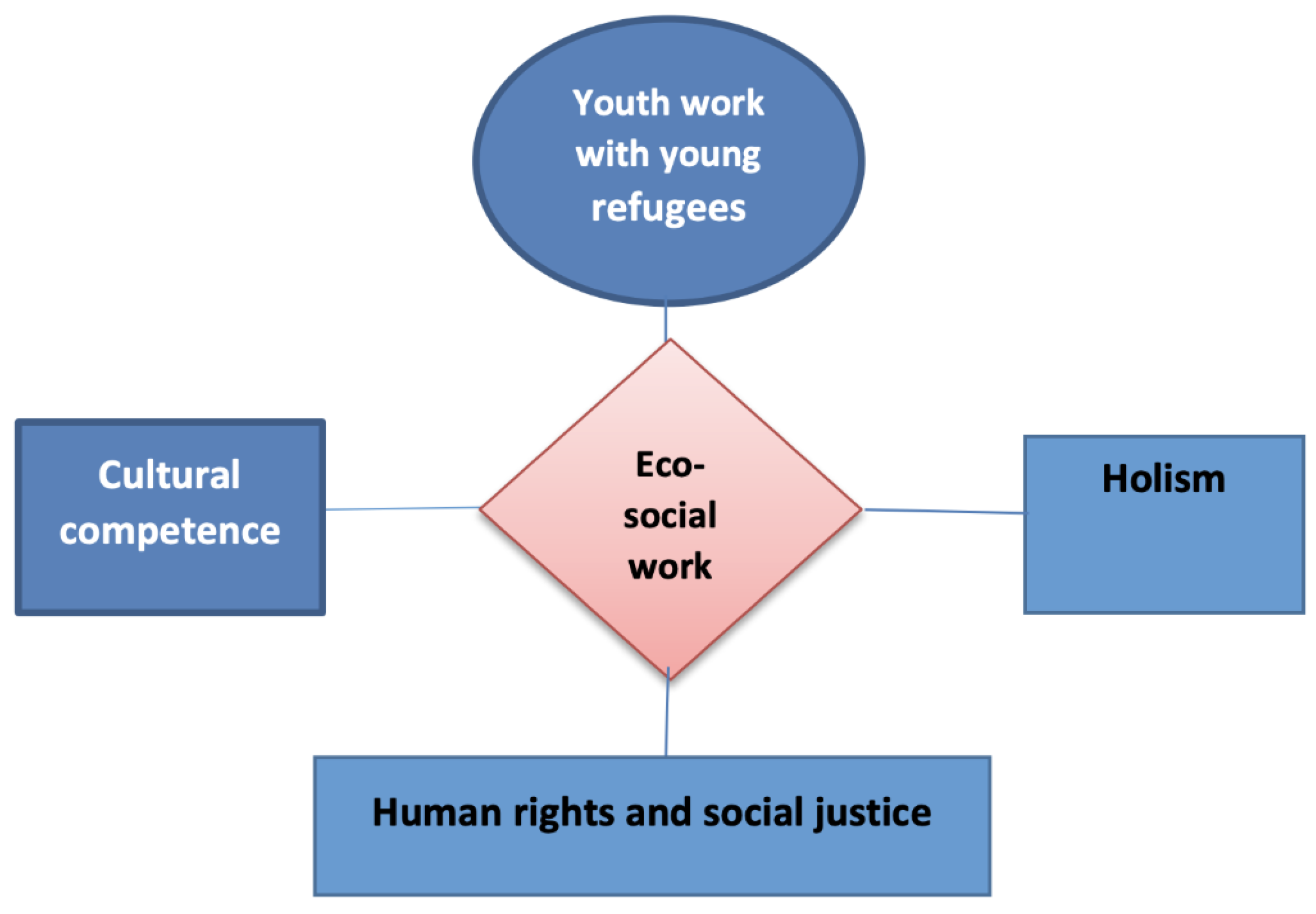

1.1.4. Theoretical Framework

1.1.5. Research Aim

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results

3.1.1. Completion and Participation

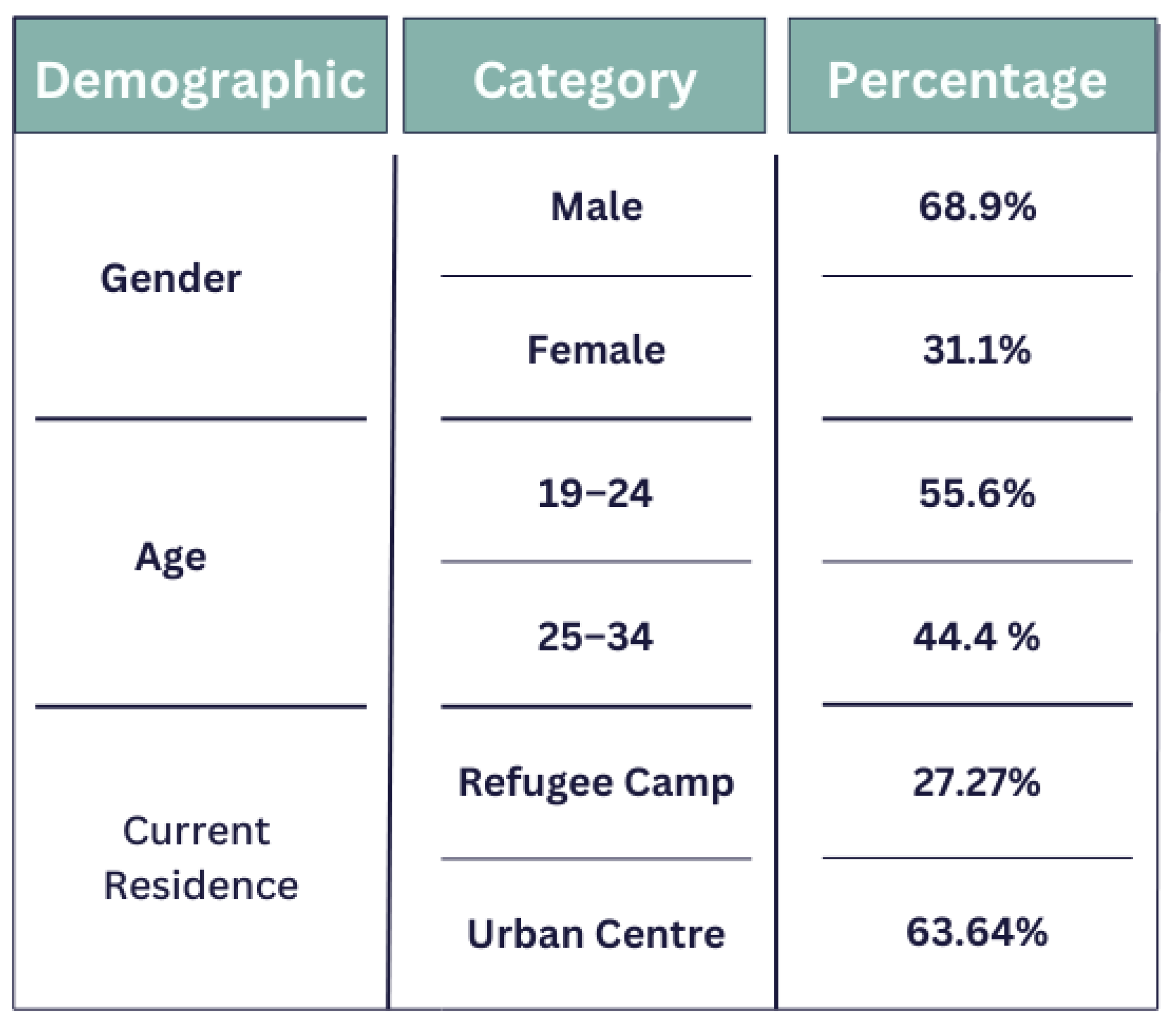

- 42 participants enrolled in the digital course (see demographic chart in Figure 4).

- 23 learners completed the online portion, and 14 submitted food maps and diaries.

- 8 of them sent in an optional business idea, and 3 ideas have been selected to receive a small start-up grant.

- Emails encouraging participants to complete incomplete assignments helped motivate some learners to act, but others seemed to struggle with completing everything.

- Participants were eager to receive a completion certificate from a Canadian university.

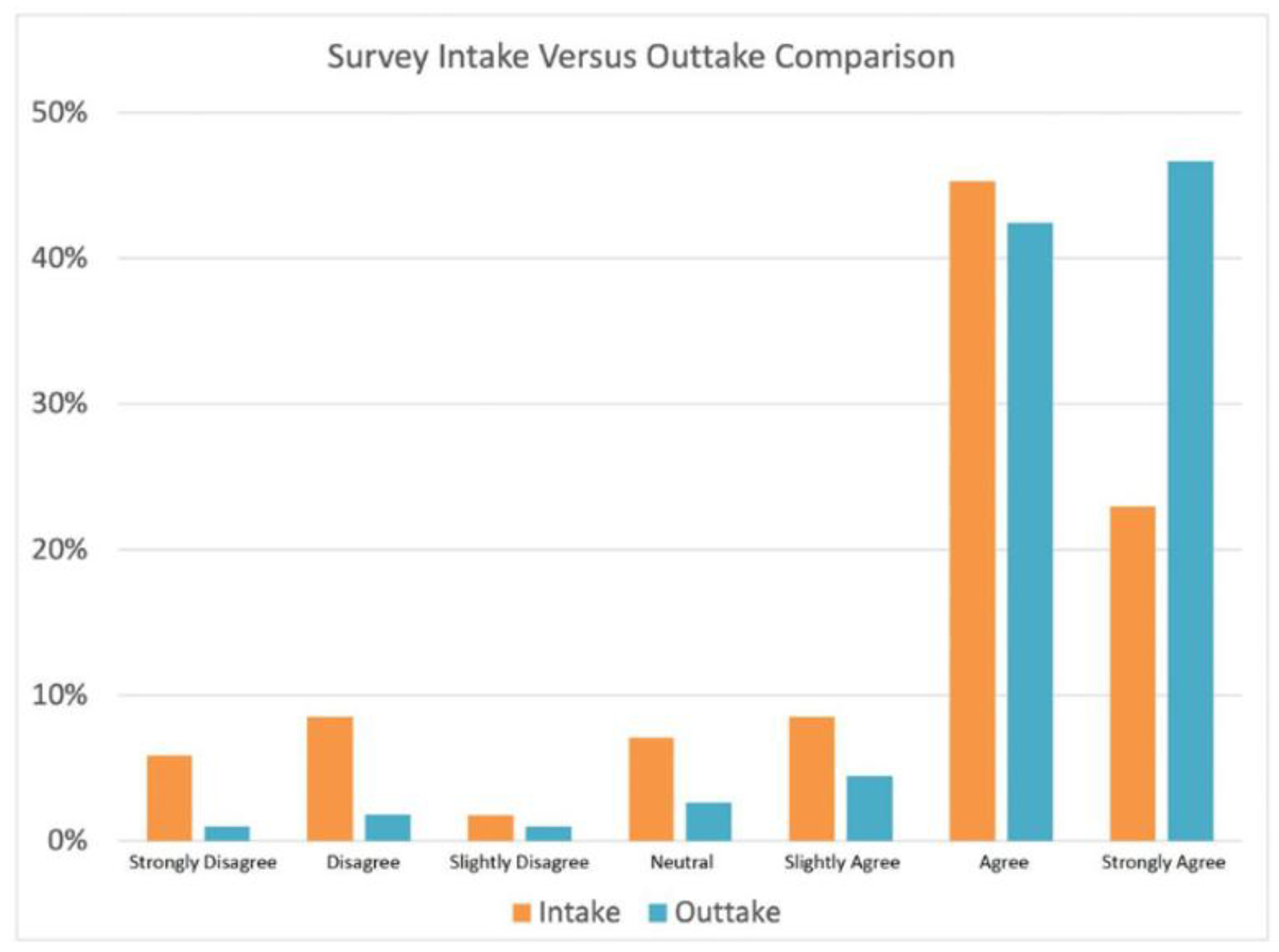

3.1.2. Knowledge Gains

- The different work permit classes in Kenya rose from 45.45 percent to 87.5 percent (+42.05 percent).

- Legal consequences of working without a work permit jumped from 63.64 percent to 100 percent.

- Rights as a worker in Kenya grew from 36.36 percent to 87.5 percent (+51.14 percent);

- What a social enterprise is improved from 45.45 percent to 93.75 percent.

- The difference between a resume and a CV climbed from 90.9 percent to 93.75 percent.

- The purpose of a cover letter was already at 100 percent agreement, but the percentage of “strongly agree” still increased, indicating greater understanding.

- The purpose of a business plan advanced from 90.9 percent agreeing to 100 percent.

3.1.3. Confidence and Empowerment

- “I feel confident in my abilities and skills to get a job” dropped from 81.81 percent to 81.25 percent.

- “I feel confident in supporting myself and/or others” contracted from 72.72 percent to 68.75 percent (−3.97 percent).

- “I feel empowered to contribute to food security in my community” increased from 90.91 percent to 93.75 percent.

3.1.4. Aspirations

3.2. Food Diaries and Refugee Food Insecurity

3.2.1. Sources and Distribution of Food

We don’t get food unless I talk to my relatives who are far away to give us something to eat. That is how we survived. Other than that, there is [not] any means of survival here in Nairobi.(as quoted in Enns et al., 2024, p. 6)

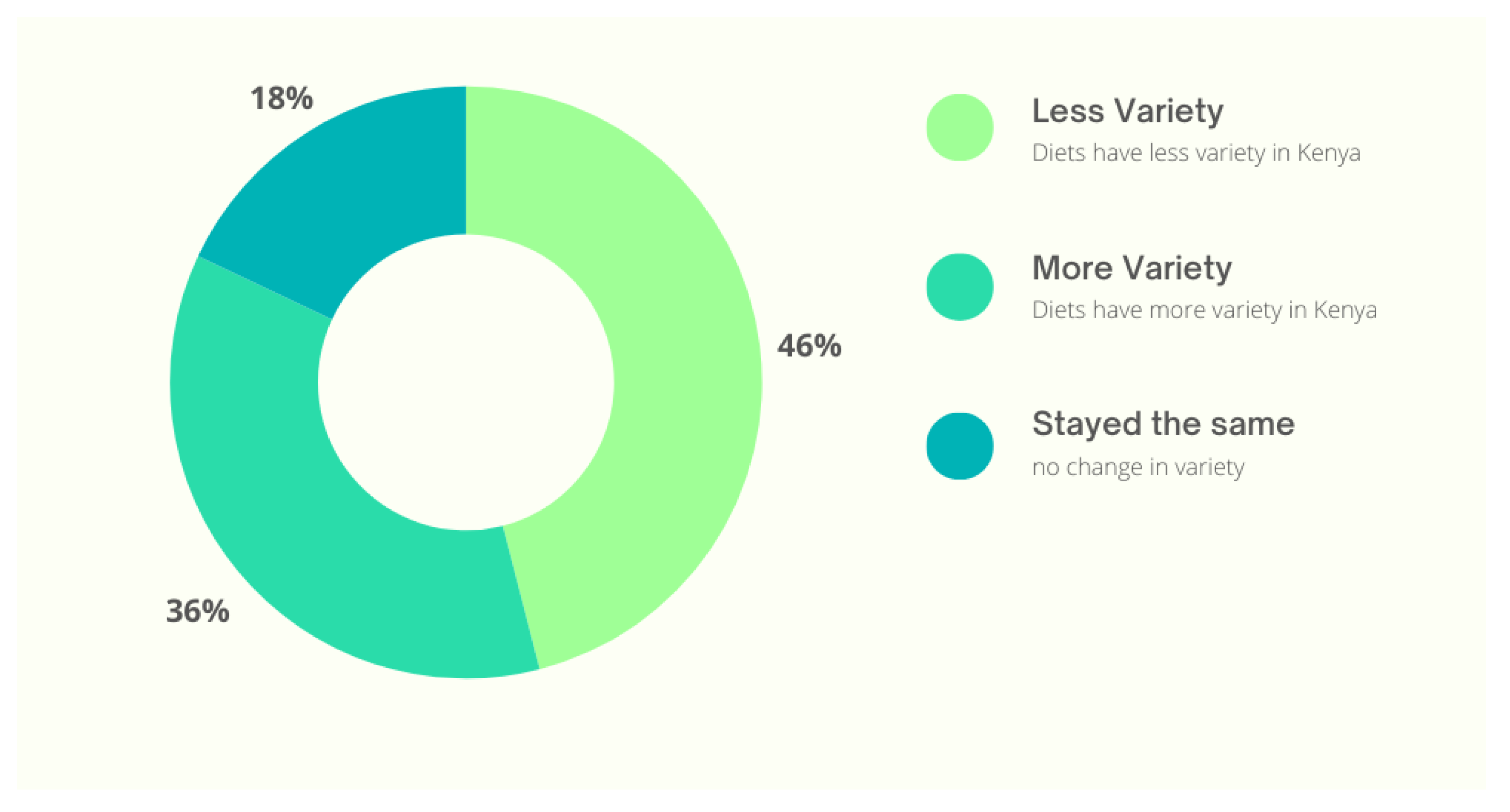

3.2.2. Change in Variety and Nutritional Quality

3.2.3. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS)

3.2.4. Roles in Procuring, Growing and Selling Food

3.3. Case Studies

3.3.1. A New Dawn for Atem

3.3.2. Sowila’s Ride

3.3.3. Beyond the Market: A Garden for Nyaboth

- Find a suitable location: a backyard, community plot, or even a school ground.

- Prepare the land and improve the soil.

- Purchase seeds: spinach, sukuma wiki, tomatoes, and onions, which are fast-growing and high-yielding.

- Train a few people in basic gardening techniques.

- Monitor growth and harvest for daily home use.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Significance and Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDSS | Household Dietary Diversity Score |

| HFIAS | Household Food Insecurity Access Scale |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WFP | World Food Program |

References

- Ahmed, Z., Crush, J., Owuor, S., & Onyango, E. (2024). Refugee migration and urban food security: Somali migrants in Nairobi, Kenya. MiFOOD Network. Available online: https://mifood.org/papers/refugee-migration-and-urban-food-security-somali-migrants-in-nairobi-kenya/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Aljararwa, R. (2023). (Re)negotiating empire: A postcolonial reading of the narrative of refugee experience in Laila Lalami’s hope and other dangerous pursuits. Journal of Global Postcolonial Studies, 11(1–2), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayeck, R. (2022). Positionality: The interplay of space, context and identity. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 160940692211147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R. T. (2025, April 9). ‘Everything was stopped’: USAID cuts hit hard in northern Kenya. The New Indian Express. Available online: https://www.newindianexpress.com/world/2025/Apr/09/everything-was-stopped-usaid-cuts-hit-hard-in-northern-kenya (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Coates, J., Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2007, August). Household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide. Version 3. Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development. Available online: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/HFIAS_ENG_v3_Aug07.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Crea, T. M., & Sparnon, N. (2017). Democratizing education at the margins: Faculty and practitioner perspectives on delivering online tertiary education for refugees. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Refugee Services. (2023). The Kenya Shirika plan: Overview and action plan. Government of Kenya. Available online: https://refugee.go.ke/kenya-shirika-plan-overview-and-action-plan (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Easton-Calabria, E., Abadi, D., Gebremedhin, G., & Wood, J. (2022). Urban refugees and IDPs in secondary cities: Case studies of crisis migration, urbanisation, and governance. Cities Alliance. Available online: https://www.citiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/citiesalliance_urban-refugees-and-idps-in-secondary-cities_2022.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Enns, C., Owuor, S., Lin, A., Kapeleelow, N., Fanta, J., Achieng, C., Kolong, W., & Swardk, K. (2024, May 11). COVID-19, food insecurity and South Sudanese urban refugees in Nairobi and Nakuru, Kenya (MiFOOD Paper No. 19). MiFOOD Network. Available online: https://mifood.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/MiFOOD19.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2021). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021: The world is at a critical juncture. Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition/2021/en/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Gikandi, L. (2020). COVID-19 and vulnerable, hardworking Kenyans: Why it’s time for a strong social protection plan (pp. 1–18). Oxfam International. [Google Scholar]

- Hews, R., McNamara, J., & Nay, Z. (2022). Prioritising lifelong and ever-learning load: Understanding post-pan demic student engagement. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 19(2), 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIAS. (2025, May 1). Refugees in Kenya: What you need to know. HIAS. Available online: https://hias.org/news/refugees-kenya-what-you-need-know/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). (n.d.). Nairobi launch: Pioneering refugee integration strategy. International Institute for Environment and Development. Available online: https://www.iied.org/nairobi-launch-pioneering-refugee-integration-strategy#:~:text=Apprencent20newpercent20Refugeepercent20Capertenc2 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). (2024). An inclusive Nairobi? refugee accounts of life in the City. International Institute for Environment and Development. Available online: https://www.iied.org/inclusive-nairobi-refugee-accounts-life-city (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Kamau, D. M., & Mwenda, M. N. (2021). Empowerment of urban refugee youths in Nairobi County, Kenya: A socio-economic perspective. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 6(1), 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi-Sánchez, J. L. (2020). Sanctuary cities: What global migration means for local governments. Social Sciences, 9(8), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkwananzi, F. (2019). Understanding migrants’ valued capabilities and functionings. In Higher education, youth and migration in contexts of disadvantage (pp. 87–102). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muindi, K., & Mberu, B. (2019). Urban refugees in Nairobi: Tackling barriers to accessing housing, services and infrastructure. International Institute for Environment and Development. Available online: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10882IIED.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Mupenzi, A., Mude, W., & Baker, S. (2020). Reflections on COVID-19 and impacts on equitable participation: The case of culturally and linguistically diverse migrant and/or refugee (CALDM/R) students in Australian higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1337–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, S., Manji, F., Holloway, K., & Lowe, C. (2019). The comprehensive refugee response framework: Progress in Kenya [working paper]. Overseas Development Institute. Available online: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/12940.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Okello, A. (2024, November). Refugee welfare in Kenya: Challenges and solutions (LERRN Working Paper No. 28). Local Engagement Refugee Research Network. Available online: https://carleton.ca/lerrn/wp-content/uploads/RM_Nov_8_2024_LERRN_Working_Paper_28.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Onyango, E. O., Crush, J. S., & Owuor, S. (2023). Food insecurity and dietary deprivation: Migrant households in Nairobi, Kenya. Nutrients, 15(5), 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orjuela-Grimm, M., Deschak, C., Aragon Gama, C. A., Bhatt-Carreño, S., Hoyos, L., Mundo, V., Bojorquez, I., Carpio, K., Quero, Y., Xicotencatl, A., & Infante, C. (2021). Migrants on the move and food (in)security: A call for research. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 24(5), 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyuela, A. (2019, December 9). Empowering refugees in Kenya through urban farming. Food Tank. Available online: https://foodtank.com/news/2019/12/empowering-refugees-in-kenya-through-urban-farming/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Pape, U., Beltramo, T., Fix, J., Nimoh, F., Rios-Rivera, L. A., & Sarr, I. (2021). Understanding the socioeconomic conditions of refugees in Kenya. Results from the 2020-21 urban socioeconomic survey (Vol. C: Urban Refugees, pp. 1–84). UNHCR & World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J. (2024, November 1). Localizing climate adaptation in Kenya’s refugee-hosting counties. Refugees International. [Google Scholar]

- Pingeot, L., & Pouliot, V. (2024). Agency is positionally distributed: Practice theory and (post)colonial structures. International Studies Quarterly, 68(2), sqae021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaree, K., Berg, M., & Thomson, R. (2016). A framework for youth work with refugees. Youth Partnership. Available online: https://pjp-eu.coe.int/documents/42128013/47262364/Framework-youth-work-refugees.pdf/94f8ad98-27af-4bfb-81e0-80fade21838a?t=1490108241000 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Schulze, H. (2018, January 15). Greening Iraq’s refugee camps: “This garden is my kingdom”. Food Tank. Available online: https://foodtank.com/news/2018/01/greening-iraqs-refugee-camps-urban-agriculture/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Sellman, J. (2018). A global postcolonial: Contemporary Arabic literature of migration to Europe. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 54(6), 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taftaf, R., & Williams, C. (2020). Supporting refugee distance: A review of the literature. American Journal of Distance, 34(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, J. (2022). Do African postcolonial theories need an epistemic decolonial turn? Postcolonial Studies, 25(1), 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufts University. (2023). Household dietary diversity score (HDDS). In Data4Diets: Building blocks for diet-related food security analysis. Available online: https://inddex.nutrition.tufts.edu/data4diets/indicator/household-dietary-diversity-score-hdds (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- UN-Habitat. (2023). Models & programs for youth’s governance & participation in planning: More inclusive & sustainable cities. UN-Habitat Youth. Available online: https://www.unhabitatyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/her_city_final_report_20221019.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- UNHCR. (2023, September 8). New UNHCR report reveals over 7 million refugee children out of school [press release]. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/new-unhcr-report-reveals-over-7-million-refugee-children-out-of-school/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- UNHCR. (2024, July 19). South Sudan—Spontaneous refugee returns dashboard (May 2024). UNHCR. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/108426 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- UNHCR. (2025, May 31). Kenya—Statistics Package (May 2025). UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/ke/media/kenya-statistics-package-31-may-2025 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- UNHCR & World Bank. (2020). Kenya: Socioeconomic survey of urban refugees in Kenya, 2021 [microdata]. UNHCR Microdata Library. Available online: https://microdata.unhcr.org/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021). Facts and figures: Economic development in Africa report 2021—Reaping the potential benefits of the African Continental Free Trade Area for inclusive growth. UN Trade and Development. Available online: https://unctad.org/press-material/facts-and-figures-7 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- USA for UNHCR. (2023, July 24). South Sudan refugee crisis explained. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/south-sudan-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. (2025, May 13). Toward a shared future: Advancing refugee integration in Kenya. Available online: https://refugees.org/toward-a-shared-future-advancing-refugee-integration-in-kenya/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Wangui, W. I., & Kipchumba, D. H. E. (2024). Determinants of urban refugee youth self-reliance in Nairobi City County, Kenya. Journal of Public Policy and Governance, 4(2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, A. (2016). Tourists, travellers, refugees: An interview with Michelle De Kretser. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 52(5), 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WELT HUNGER LIFE. (n.d.). Household dietary diversity score (HDDS) [Web indicator]. WELT HUNGER LIFE. Available online: https://whh.indikit.net/indicator/925-food-security/4464-household-dietary-diversity-score-hdds (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- WHO. (n.d.). Refugee and migrant health—Global. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/refugee-and-migrant-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Witthaus, G. (2023). Refugees and online engagement in higher education: A capabilitarian model. Online Learning, 27(2), 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witthaus, G., & Ryan, G. (2021). Supported mobile learning in the “Third Spaces” between non-formal and formal education for displaced people. In J. Traxler, & H. Crompton (Eds.), Critical mobile pedagogy: Cases of inclusion, development, and empowerment (pp. 76–88). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- World Food Programme (WFP). (2025, May 22). Refugees in Kenya at risk of worsening hunger as WFP faces critical funding shortfall. World Food Programme. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/news/refugees-kenya-risk-worsening-hunger-wfp-faces-critical-funding-shortfall (accessed on 9 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schofield, K.; Fanta, J.; Pioth, W.K.; Cook, A.; Owuor, S.; Enns, C. Architecture for Spatially Just Food System Planning with and for Urban Youth South Sudanese Refugees in Kenya. Youth 2025, 5, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040130

Schofield K, Fanta J, Pioth WK, Cook A, Owuor S, Enns C. Architecture for Spatially Just Food System Planning with and for Urban Youth South Sudanese Refugees in Kenya. Youth. 2025; 5(4):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040130

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchofield, Katie, Jacqueline Fanta, William Kolong Pioth, Alissa Cook, Samuel Owuor, and Cherie Enns. 2025. "Architecture for Spatially Just Food System Planning with and for Urban Youth South Sudanese Refugees in Kenya" Youth 5, no. 4: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040130

APA StyleSchofield, K., Fanta, J., Pioth, W. K., Cook, A., Owuor, S., & Enns, C. (2025). Architecture for Spatially Just Food System Planning with and for Urban Youth South Sudanese Refugees in Kenya. Youth, 5(4), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040130