Climate Activism in Our Part of The World and Methodological Insights on How to Study It †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Approach: (Geo)Politics of Impossible Research or How Do I Get There?

3. Geopolitical Context at COP27: Who Is Saving Who? (And from Whom?)

4. Theoretical and Methodological Framework: From Social Non-Movements to Environmental Non-Activism

5. Findings: The Skeptical, the Hopeful, the Proud

“I would say a huge greenwashing would be just COP27 happening in Egypt.”(E02, 30, M.)13

“People in the pavilion space had absolutely no idea [of] what’s happening in the negotiations about everything they care, completely disconnected, and this gives space for greenwashing, this gives space for corporates to actually divert attention away from the negotiations, it makes the work of activists harder.”(E08, 26, M.)

Sponsors of the conference were widely criticized for greenwashing. In September 2022, Egypt’s foreign ministry signed a contract with Coca-Cola to sponsor COP27 (Ahram Online, 2022). The decision sparked considerable controversy within climate circles in Egypt and globally due to the brand’s longstanding notoriety for decades of environmental and human rights abuses (Tigue, 2022). Activists called on the UN to remove Coca-Cola, along with Microsoft, as sponsors of COP27, describing the partnership as “pure greenwashing” (Tigue, 2022). However, Coca-Cola maintained a prominent presence at the conference, just as it has throughout Cairo: “Some organizations will never be sustainable, because what they’re doing mainly is greenwashing, “Hi, like, I’m Coca Cola, I’m not sustainable whatsoever, but I’m gonna invest money to reduce carbon emissions”, they just want the good publicity for being sustainable.”(E01, 26, F.)

“We’re trying to take money from the countries of the North, because as compensation for the historical extractivism, which is, of course, very important issue and we all need to back this up, because it’s the only fair thing that can happen, and by coincidence, the governments of the Global South are the most corrupted, and there is no accountability, no transparency. So, who will be monitoring this? Civil society of course. Where is civil society? There is no civil society, they are in prison. So, tackling the human rights issue is inevitable here, if we are speaking about any kind of Loss and Damage [Fund] […] even me advocating for climate injustices […] you need civil society, you need freedom of speech to be speaking about this.”(E13, 44, M.)

“There’s not that many of us [Egyptian activists], we have seen a rise because of COP27. But now, four months later, […] the momentum is now not visible anymore, […] it’s more of a thing that they just engage with for the sake of the conference.”(E08, 26, M.)

“For them [the government] it’s still a checklist for certain keywords that they need to say, so that they can get more funds, and more loans […] everyone is making the other hear what they want to hear. “Will it be a potential for more money?” And now we call it green, and we will be tree huggers.”(E13, 44, M.)

“I think it was a great way to bring attention to the environmental issues in Egypt, and to make Egyptians even just think about the environmental issues. And also, to show that there’s a lot of people who are working towards a better future, especially the youth.”(E07, 32, F.)

“I have to say COP27 was a golden moment that all the actors working on climate got to know each other and were able to get together and get themselves together […] and I hope that that this momentum continues, although unlikely will, but at least there is hope.”(E04, 40, M.)

“The main challenge [facing environmental groups] was the misunderstanding from the authorities, […] before COP27 or the announce that Egypt will host the COP27, it wasn’t easy to explain to the any responsible [authorities] about the environment, climate change, the human impact, it was like something that to talk about environment, it was a kind of welfare, like, people die, there is more important problems. But also people die from climate change.”(E20, 43, M.)

“It’s about the connections. […] I’ve connected with climate activists from Namibia, from Tuvalu, from Fiji Islands, and like I’ve met a queer inclusive feminist from the Pacifics and working on sexual reproductive health and rights in a climate aware approach.”(E15, 33, F.)

“It was good to found that people share your interest, […] that you are not alone […] there is people they share the same passion with you to also to get to know to new tools, to know how to fight for your case in a better way, […] it was a very good opportunity for me to tell my story”(E20, 43, M.)

“If you look at the developing and even LDCs, like the Least Developed Countries, or the small island developing states, how they get one weather event that wipes out 200% or 300% of their GDP in a few hours, that’s why it was a huge accomplishment of COP27 to establish the foundations of the Loss and Damage Fund, which is supposed to be dedicated to really compensating those countries that are worst affected by the impacts of climate change and extreme weather events.”(E12, 45, M.)

“I think for any Egyptian actor, regardless [of] what they work on, COP27 was a success, and I’m not here looking from an international community’s perspective, […] I’m just looking at the context in Egypt: whether you are a government official, whether you are an environmental activist, whether you are a human rights activist, whatever you’re working on, this was a success. Every single activist was able to spotlight issues they’re working on and adequately engage with different stakeholders and bring to light things that if COP had not come to Egypt this would have never been discussed or acknowledged, that’s why I deem it a success”.(E08, 26, M.)

“I think COP27 provided a platform, an opportunity for human rights activists to speak that they don’t get, just listen, just look at pre- and post-COP, pre-COP all the international journalists were paying attention to issues in Egypt, post-COP they don’t. And now they’re on to COP28, and that’s exactly what I mean.”(E08, 26, M.)

“I think Egypt before COP27 isn’t Egypt after COP27”(E09, 20, F.)

“Egypt’s Vision 2030 was there since 2015 but like, in the past five years maybe the discourse was more familiar, you start seeing more NGOs coming out and saying that […] we want to advocate sustainability […], especially by the time COP27 was being hosted in Egypt, So more NGOs started leaning more towards working on the SDGs, […] private sector even started creating foundations […] in order to advocate sustainable development as part of their corporate social responsibility.”(E11, 26, F.)

6. Discussion

“… amongst the problems of the existing institutional structure is the lack of a clear participation mechanism to secure societal buy-ins. […] some other experts were doubtful about the participatory process that the government referred to as being part of the development of NCCS [Egypt National Climate Change Strategy 2050].19 Either they said that they were surprised to learn that there is a NCCS, or they participated but were concerned about the extent their opinions will be heeded to”.(p. 300 [emphasis added])

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

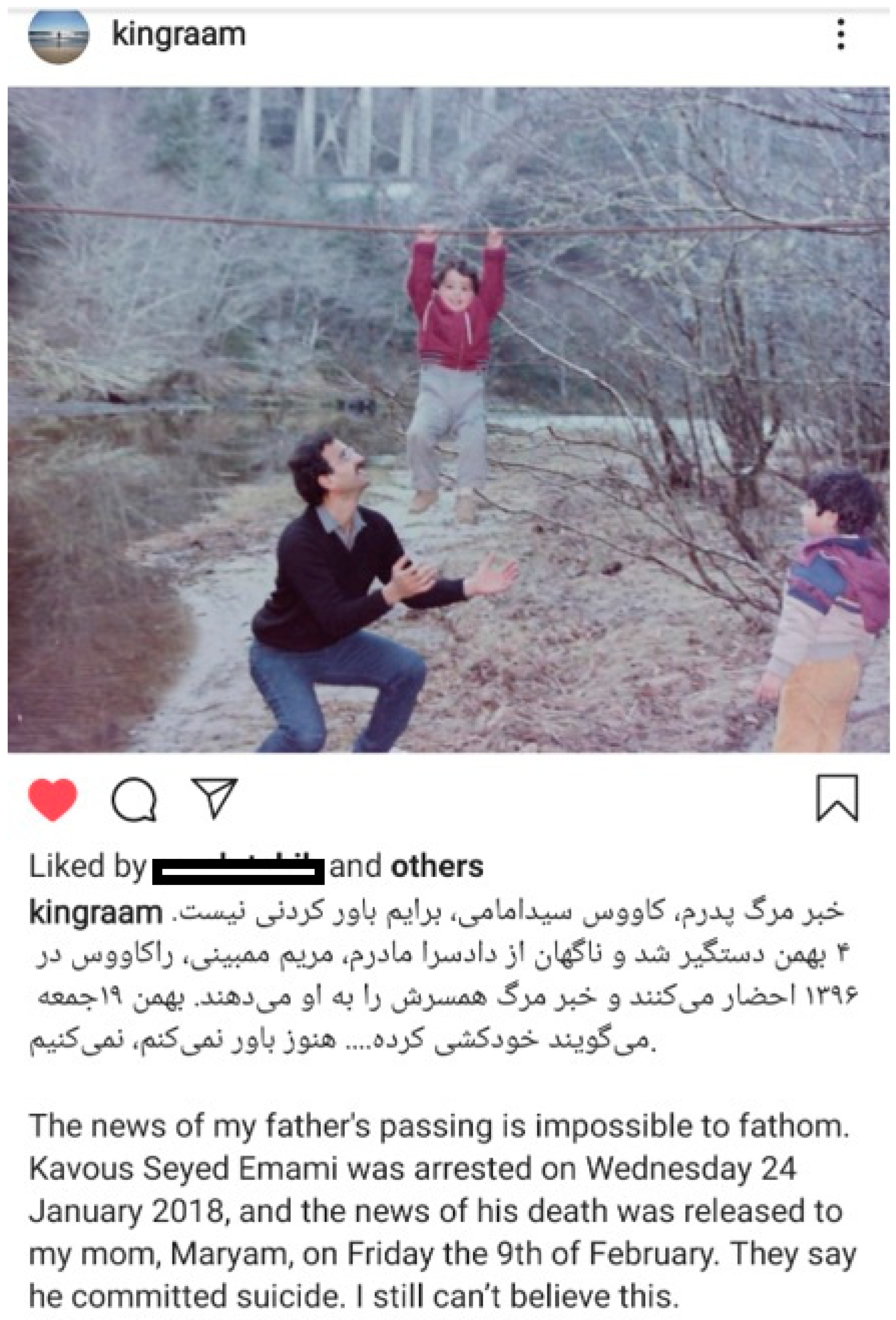

| 1 | Doyle and Simpson (2006, p. 750) observe that the Iranian government sees state-sanctioned environmentalism as a safe form of participation or a pressure relief valve that ultimately helps to consolidate its power. Their observation, however, is not applicable to the post-Mahsa Zhina Amini uprising Iran. For more on the Iranian civil society after the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, see Khatam (2023). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | In this research, I adopt Bayat’s (2002, p. 3) definition of activism referring to “any kind of human activity that aims to engender change in people’s lives. As an antithesis of passivity, ‘activism’ includes many types of activities, ranging from survival strategies and resistance to more sustained forms of collective action and social movements”. |

| 4 | In her chapter, “Interviewing women: a contradiction in terms”, Oakley (1981) discusses the importance of establishing a dialogue-based space where participants have the opportunity to “talk back”. Watkins and Shulman (2008, p. 307) use the term “counter-interview” to discuss Oakley’s point. However, Oakley never uses the term “counter-interview”. She provides an interesting list of questions that her interviewees asked her at some point during the interviews and between them in a longitudinal study on transision to motherhood. The questions raised by Oakley’s respondants were mostly focused on requesting information, such as “who will deliver my baby?”(76%). A quarter of the questions were personal focused on the interviwer, while only 6% were on the research and 4% on reqesting advice (Oakley, 1981, p. 42). Oakley makes an unconventional decision “to answer all personal questions and questions about the research as fully as was required” (p. 47) despite “the [methods] textbook code of ethics with regard to interviewing women”(p.48), which was mainly redirecting the respondants’ questions or ignoring them altogether. Oakley challenges the common dominant–subordinate interviewer–interviewee relationship that replicates male–female power dynamics in the larger society and argues that “’proper’ interview is a masculine fiction” (p. 55) that sees interviewees merely as sources of data (p. 48). |

| 5 | A topic we have discussed in (Erfani et al., 2024). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Giulio Regeni was a Cambridge Ph.D. student studying labor movement and unions in Egypt. To learn more about his tragic death, visit https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/24/why-was-he-killed-brutal-death-of-italian-student-in-egypt-confounds-experts. (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 8 | “Arrests and detention, NGO asset freezes and dissolutions and travel restrictions against human rights defenders have created a climate of fear for Egyptian civil society organisations to engage visibly at the COP27” (UNCHR, 2022). |

| 9 | Egyptians have weekends on Fridays and Saturdays. Friday is the Islamic day of worship when the communal Friday Prayer is practiced at noon in local and major mosques by millions of Muslims around the world. See Brooke et al. (2023) to learn about the political implications of the Friday Prayer in the Middle East and “the Friday Effect”. |

| 10 | Many churches in Egypt hold worship services on Fridays (and some on both Fridays and Sundays). |

| 11 | Many Egyptian and Turkish interviewees mentioned the public perception of environmental issues or environment in general as a luxury or Western topic as one of the challenges in their activism. |

| 12 | Reference to fieldnotes. |

| 13 | The coding represents the participants’ age (the second number) and gender (F, M, or X). |

| 14 | Egyptian activists were under more rigid scrutiny than foreigners. One of my participants reported that he was interrupted by the police and asked to leave when he was having a conversation with Israeli climate activists during the conference (E05, 17, M). |

| 15 | However, some of my informants and participants did not necessarily see themselves as African or Arab and referred to their Egyptian origin as Pharaonic. |

| 16 | The full speech is available on the State Information Service website at https://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/172566/President-El-Sisi’s-Speech-at-the-Opening-Session-of-COP-27 accessed on 20 July 2025. |

| 17 | The full speech is available on The White House website at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/11/11/ accessed on 20 July 2025. |

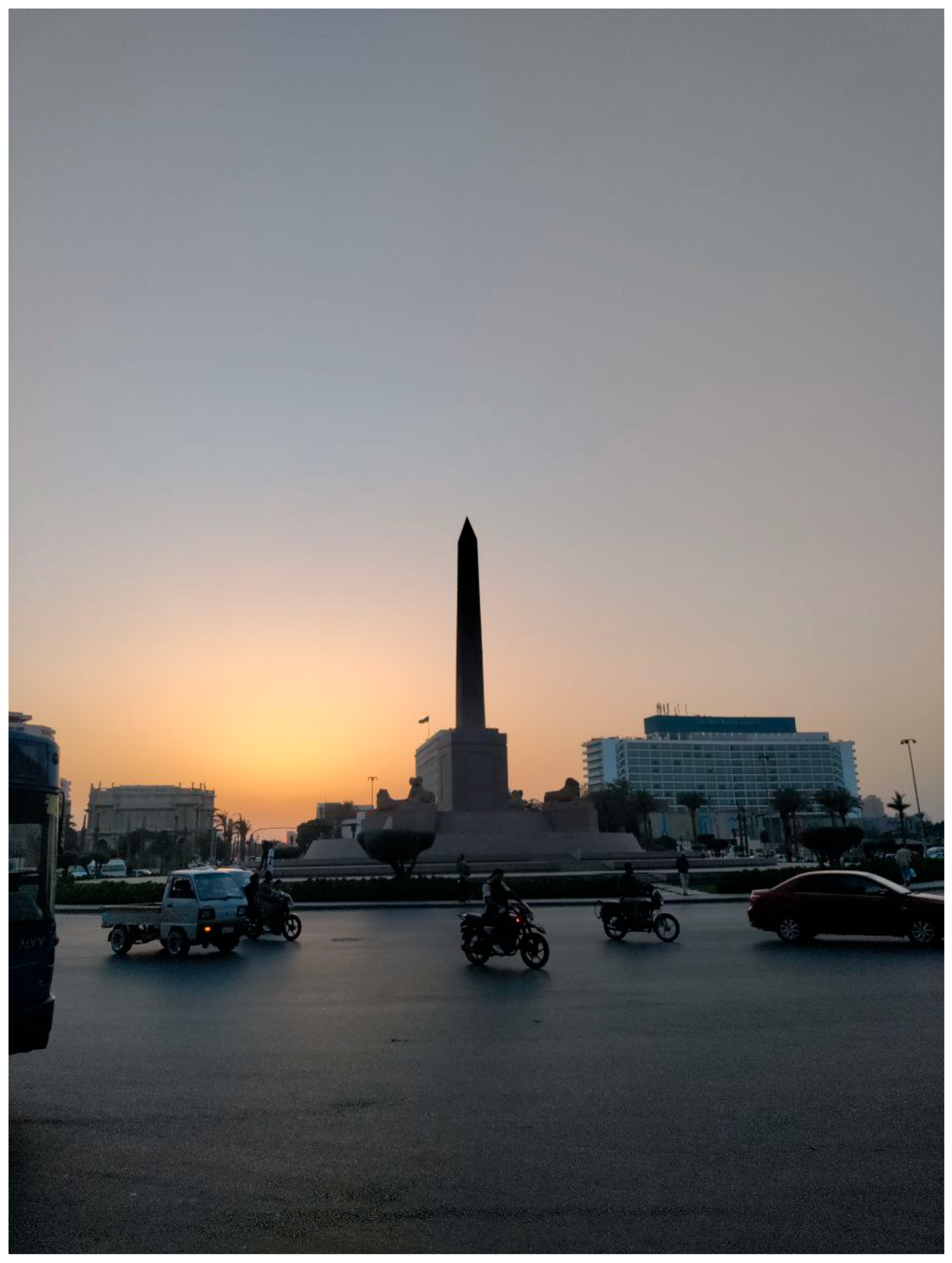

| 18 | Literally translated as “Mother of the World”. |

| 19 | Available at https://www.eeaa.gov.eg/Uploads/Topics/Files/20221206130720583.pdf accessed on 20 July 2025. |

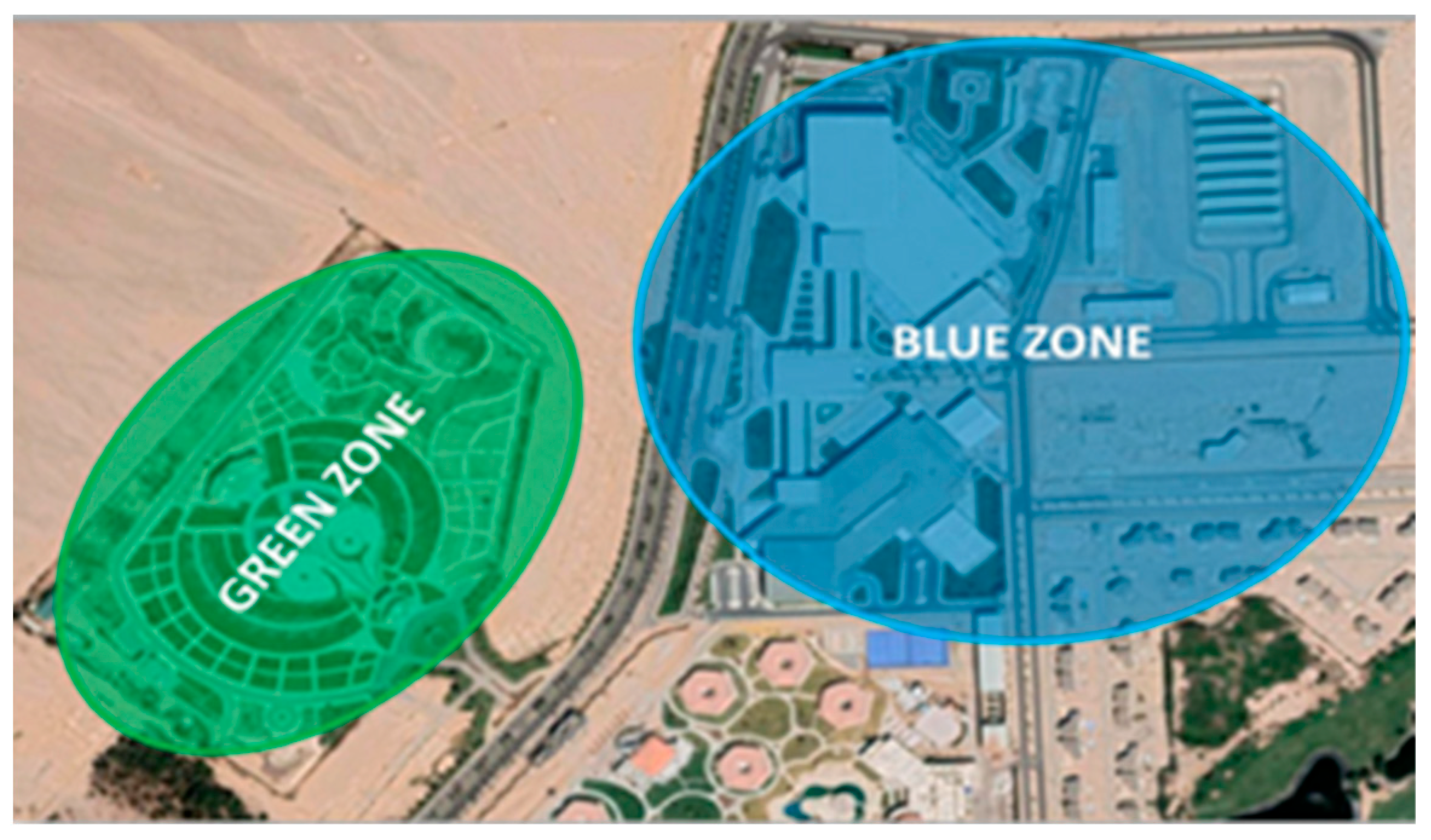

| 20 | Available at https://www.cop28.com/-/media/Project/COP28/files/COP28-Overview-En.pdf accessed on 20 July 2025. |

References

- Ahram Online. (2022, September 29). Coca-Cola to sponsor COP27. Available online: https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/10/1255/476935/COP/Sharm-ElSheikh/CocaCola-to-sponsor-COP-.aspx (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Alibeli, M. (2004). Environmentalism in the Middle East: Attitudes toward preservation, conservation, and grass roots ecosystem management in Bahrain, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. Mississippi State University. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. (2023). UAE: New sham trial targeting dissidents during COP28 reveals authorities’ shameless contempt for human rights. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/12/uae-new-sham-trial-targeting-dissidents-during-cop28-reveals-authorities-shameless-contempt-for-human-rights/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Ayana, A. N., Arts, B., & Wiersum, K. F. (2018). How environmental NGOs have influenced decision making in a ‘semiauthoritarian’ state: The case of forest policy in Ethiopia. World Development, 109, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A. (2002). Activism and social development in the Middle East. International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 34, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A. (2013). Life as politics: How ordinary people change the Middle East. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BayatRizi, Z., Erfani, R., & Torabi, S. (2022). Grieving immigrants: Emotions at the intersections of politics and race. In J. Jean-Pierre, V. Watts, C. E. James, P. Albanese, X. Chen, & M. Graydon (Eds.), Reading sociology: Decolonizing Canada (4th ed., pp. 214–219). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. (2011). Egypt: Cairo’s Tahrir Square fills with protesters. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20110709112514/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-14075493 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Bello, W. (2007, October 13). The environmental movement in the Global South: The pivotal agent in the fight against global warming? International Media Forum for the Protection of Nature. Available online: https://focusweb.org/environmental-movement-in-the-global-south-the-pivotal-agent-in-the-fight-against-global-warming/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Bisaillon, L. (2012). An analytic glossary to social inquiry using institutional and political activist ethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(5), 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhari, J. (2022, October 31). Egypt’s NGOs and activists are not welcome at COP27. Equal Times. Available online: https://www.equaltimes.org/egypt-s-ngos-and-activists-are-not?lang=en (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Böhmelt, T. (2014). Political opportunity structures in dictatorships? Explaining ENGO existence in autocratic regimes. Journal of Environment & Development, 23(4), 446–471. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, S., Chouhoud, Y., & Hoffman, M. (2023). The Friday effect: How communal religious practice heightens exclusionary attitudes. British Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, J., & Fagan, A. (2010). Environmental mobilisation and organisations in post-socialist Europe and the former Soviet Union. Environmental Politics, 19(5), 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Action Network International. (2022, November 10). Eco-NGO Newsletter. Available online: https://climatenetwork.org/resource/eco5-cop27/ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Doyle, T., & Simpson, A. (2006). Traversing more than speed bumps: Green politics under authoritarian regimes in Burma and Iran. Environmental Politics, 15(5), 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baradei, L., & Sabbah, S. (2024). Climate change governance and institutional structures in Egypt pre- and post-COP27. In P. F. Haruna, L. El Baradei, L. van Jaarsveldt, A. D. Benavides, & C. M. Stanica (Eds.), Climate governance in international and comparative perspective: Issues and experiences in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean (pp. 227–318). Information Age Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Erfani, R., BayatRizi, Z., & Torabi, S. (2024). Flying, fleeing, and hanging on: Trauma baggage at airports. In C. Courage, & A. McKeown (Eds.), Trauma-informed placemaking (pp. 45–53). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fadaee, S. (2016). Post-contentious politics and Iran’s first ecovillage. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, 21(11), 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaee, S. (2018). Environmentalism and social change in Iran. In R. Barlow, & S. Akbarzadeh (Eds.), Human rights and agents of change in Iran: Towards a theory of change. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorenko, I. (2017). Environmental activism, non-governmental organisations and the new generation of civil society in Russia and China. University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, T. (2007). Are environmental social movements socially exclusive? An historical study from Thailand. World Development, 35(12), 2110–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, M. (2015). The Dalian chemical plant protest, environmental activism, and China’s developing civil society. In C. Hager, & M. A. Haddad (Eds.), NIMBY is beautiful: Cases of local activism and environmental innovation around the world. Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, A. F. (2005). Unlocking the hegemonic power of ‘The People’s Democratic Dictatorship’: An analysis of civil society and the state in the PRC. China Report, 41(3), 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. (2014). Policy deliberation as a goal: The case of Chinese ENGO activism. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 19, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. (2011). Environmental movement in democratizing Taiwan (1980–2004): A political opportunity structure perspective. In J. Broadbent, & V. Brockman (Eds.), East Asian social movements: Power, protest, and change in a dynamic region. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. (2019). Iran: Environmentalists sentenced. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/22/iran-environmentalists-sentenced (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Inglehart, R. (1995). Public support for environmental protection: Objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. PS: Political Science and Politics, 28(1), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz-Gerro, T., Greenspan, I., Handy, F., Hoon-Young, L., & Frey, A. (2015). Environmental philanthropy and environmental behavior in five countries: Is there convergence among youth? Voluntas, 26, 1485–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatam, A. (2023). Mahsa Amini’s killing, state violence, and moral policing in Iran. Human Geography, 16(3), 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, S. (2016). Protests against energy projects in Turkey: Environmental activism above politics? British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 43(3), 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, A. (2014). The mother of the world? Atlantic Council. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/the-mother-of-the-world/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Ku, D. (2011). The korean environmental movement: Green politics through social movement. In J. Broadbent, & V. Brockman (Eds.), East asian social movements: Power, protest, and change in a dynamic region. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon-Callo, V., & Hyatt, S. B. (2003). The neoliberal state and the depoliticization of poverty: Activist anthropology and “Ethnography from below”. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic, 32(2), 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, C., & Yanhua, B. (2018). The paradox of responsive authoritarianism: How civic activism spurs environmental penalties in China. Organization Science, 29(5), 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, A. (2023). Activists stage rare UAE politics protest during COP28 climate summit. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/activists-stage-rare-uae-politics-protest-during-cop28-climate-summit-2023-12-09/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Melucci, A. (1989). Nomads of the present: Social movements and individual needs in contemporary society. Hutchinson Radius. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, C., & Staeheli, L. (2016). Nature, environmentalism, and the politics of citizenship in post-civil war Lebanon. Cultural Geographies, 23(2), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K. (2007). Democratisation and environmental nongovernmental organisations in Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 37(4), 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, A. (1981). Interviewing women: A contradiction in terms. In H. Roberts (Ed.), Doing feminist research (pp. 30–61). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters. (2022). Egyptian security arrests dozens ahead of COP27 climate summit-rights group. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/egyptian-security-arrests-dozens-ahead-cop27-climate-summit-rights-group-2022-11-01/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Scharenberg, A. (2023). Contested knowledges: Negotiating the epistemic politics of engaged activist ethnography. Ethnography. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, J. (2018). Environmental activism in the MIDDLE East and North Africa. In H. Verhoeven (Ed.), Environmental politics in the Middle East: Local struggles, global connections. Hurst Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, N. (2012). Social movements and activist ethnography. Organization, 20(4), 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J. W. (2015). Building civil society in authoritarian China importance of leadership connections for establishing effective nongovernmental organizations in a non-democracy. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Telmissany, M. (2014). The utopian and dystopian functions of Tahrir Square. Postcolonial Studies, 17(1), 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, C., Thang, S., & Chiu, C. (2011). Inclusion, identity, and environmental justice in new democracies: The politics of pollution remediation in Taiwan. Comparative Politics, 43(3), 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Globe and Mail. (2018). Globe editorial: Once again, a Canadian dies in an Iran jail. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/editorials/globe-editorial-once-again-a-canadian-dies-in-an-iran-jail/article37984009/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- The Guardian. (2022). Egyptian regime criticized as climate activist arrested in run-up to Cop27. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/02/egypt-human-rights-climate-crisis-cop27 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Thompson, J. (2001). Planetary citizenship: The definition and defence of an Ideal. In G. Brendan, & N. Low (Eds.), Governing for the environment: Global problems, ethics and democracy. Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Tigue, K. (2022, October 25). Coke sponsoring COP27 is the definition of ‘Greenwashing,’ activists say. Inside Climate News. Available online: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/25102022/coke-sponsoring-cop27-is-the-definition-of-greenwashing-activists-say/#:~:text=Activists%20are%20calling%20on%20the,role%20in%20perpetuating%20climate%20change (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Tullius, J. D. (1997). Environmental groups as catalysts for political liberalization in authoritarian societies: Bulgaria and Taiwan during the 1980s. University of Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- Tuna, M. (1998). Environmentalism: An empirical test of multi-level effects on environmental attitudes in more and less developed countries. Mississippi State University. [Google Scholar]

- UNCHR. (2022, October 7). Egypt: UN experts alarmed by restrictions on civil society ahead of climate summit. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/10/egypt-un-experts-alarmed-restrictions-civil-society-ahead-climate-summit (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- UNFCCC. (2022, November 11). A day in the life of an observer at COP: An observer handbook for COP 27. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Observer%20handbook%20for%20COP27.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Vu, N. A. (2017). Grassroots Environmental Activism in an Authoritarian Context: The Trees Movement in Vietnam. Voluntas, 28, 1180–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M., & Shulman, H. (2008). Placing dialogical ethics at the center of psychological research. In Toward psychologies of liberation. Critical theory and practice in psychology and the human sciences. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Yew, W. L. (2016). Constraint without Coercion: Indirect repression of environmental protest in Malaysia. Pacific Affairs, 89(3), 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z., & Startup, A. (2024). Reclaiming narratives—MUSLIM women navigating activism in educational research implications and recommendations for educators. Journal of Culture and Values in Education, 7(3), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erfani, R. Climate Activism in Our Part of The World and Methodological Insights on How to Study It. Youth 2025, 5, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030080

Erfani R. Climate Activism in Our Part of The World and Methodological Insights on How to Study It. Youth. 2025; 5(3):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030080

Chicago/Turabian StyleErfani, Rezvaneh. 2025. "Climate Activism in Our Part of The World and Methodological Insights on How to Study It" Youth 5, no. 3: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030080

APA StyleErfani, R. (2025). Climate Activism in Our Part of The World and Methodological Insights on How to Study It. Youth, 5(3), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030080