Abstract

The inclusion of children and young people as co-researchers within mental health research has become increasingly recognised as valuable to improve equity and research quality. These approaches are considered important to shift knowledge and power hierarchies in research that has traditionally marginalised the voices of young people and prioritised positivist ways of knowing. Yet, very little research has explored the value of including youth advisors in research exploring the arts and mental health. This article, co-written intergenerationally, explores the role of a youth advisory (YA) in the design, data collection, and knowledge exchange of the DanceConnect research project: a study exploring if and how online dance classes may improve the social and mental wellbeing of young people (aged 16–24) living with anxiety in the UK. Drawing upon qualitative data (audio recordings of advisory meetings from the study (n = 5 meetings), a youth advisory focus group with an arts-based component (n = 1), and researcher ethnographic fieldnotes from four researchers), this study reflects on the role of a youth advisory in young researchers’ own lives. Through a reflexive analytic approach, we found that the youth advisory constructed meaningful emotional experiences, fostered spaces of learning and growth, and enabled a sense of community. Reflecting on our findings, we also set out key recommendations for researchers working in the field of arts and mental health who may wish to establish youth advisories in the future. This article acts as an important resource that can be used to inform and reflect on improving coproduction processes with youth advisors in arts and mental health research.

1. Introduction

Mental health researchers are increasingly recognising the value of participatory and arts-based approaches, with the expertise and lived experiences of young people becoming a central part of the research process. Participatory research methods have become popular to trouble power relations inherent in traditional hierarchical approaches to health research, supporting research with rather than on participants [,]. Having young people as researchers and advisors has proliferated across research, particularly in qualitative and coproduced research designs, with opportunities for being engaged in consultation, acting as lead or co-researchers (e.g., [,,]), and being key players on advisories (e.g., []). Advisories and committees are also prevalent in policy and programmatic work, with an increased focus on engaging youth “voice” in decision-making processes. Research shows that listening to youth on issues that affect them can improve health research processes and outcomes []. Of note, the shared emotional experiences of collectively engaging in participatory youth research are important to the value and impact of the process, whereby emotional relations between researchers and participants can bridge and link groups together (e.g., []). From a structural perspective, research funding bodies are also increasingly requiring the engagement of participants in the design of proposals (e.g., Medical Research Council, UK Research and Innovation) and throughout the research process (e.g., the inclusion of Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)) and coproduction. There is also growing recognition that involving youth researchers may increase the effectiveness of healthcare systems themselves.

Yet, despite the recognition of the value that youth advisories can bring to mental health research, constraints such as traditional academic structures and scarce resources can limit meaningful collaboration with children and young people throughout a research process. There is also a spectrum of meaningful participation, ranging from tokenistic gestures to in-depth quality processes that build long-term relationships with young people, and involving youth does not necessarily entail equitable engagement. While many disciplines and sectors have had epistemological shifts to conduct research with and for young people, engaging youth meaningfully in research “remains fraught with conceptual, methodological, and practical challenges” [] (p. 1). More research is needed to understand these processes and challenges in greater depth.

Further, within the context of major global mental health challenges, the role of the arts in mental health has increasingly become a priority research and policy area. Research has highlighted the benefits of the arts in the prevention, management, and treatment of a range of mental health conditions [], and global policies have recognised the value of the arts to mental health (e.g., in the UK, USA, Australia, Africa; []), including suggesting that the arts should be an integral part of the EU’s mental health strategy []. Within this landscape, youth mental health is a growing area of interest in view of the increasing psychosocial challenges experienced by young people []. However, despite the recognition of the importance of the role of the arts in youth mental health experiences, very little research has taken a participatory or coproduced approach to research. This is surprising given the potential for participatory methodologies to provide support in terms of equity and inclusion and to contribute to young people’s mental health. A few studies that do exist include a study exploring organisational operations of youth arts for wellbeing, which included a youth advisory for feedback on methods []; a study exploring music therapy assessments, which recruited participants via a youth advisory of a child and youth mental health service [] and a study seeking to develop a group music-making project for mental health recovery, which included a youth advisory board who provided feedback on the research process []. Yet, there is a dearth of studies that have embedded a youth advisory within the whole design and delivery of arts and mental health projects.

There is also a striking lack of detail on youth advisory experiences in arts and health research publications. Barriers to youth advisories tend to include a lack of resources, challenges in recruiting youth, ethical approval issues, and a lack of support systems structurally. Despite scholars advocating for the incorporation of youth voices in research and interest in participatory approaches, many academic institutions are not equipped to effectively embrace the processes of youth-engaged research []. Deeply rooted adultist structures in academia tend to place a higher emphasis on quicker outputs, with ethical review processes placing more value on procedural rather than relational ethics, which is important in coproduced youth research []. Researchers have noted that ethics committees can be highly risk-averse with an overemphasis on children’s ‘vulnerability’ and limited belief in their competency for research participation []. While ethical regulatory bodies intend to support research, their requirements may “dominate, oppress, and overwhelm researchers and advisors” processes due to the “power and privilege inherent in present-day academic structures” [] (p. 5)

Addressing the need to better understand youth coproduction processes within arts and mental health research, this study aimed to draw on learnings from an arts and mental health research project (the DanceConnect study) to

- Construct and explore key processes that underpin inclusive youth advisory groups in arts and mental health research;

- Unpack the role of a youth advisory in supporting the mental health and wellbeing of youth advisors;

- Provide recommendations for researchers working in the field of arts and mental health who wish to work in partnership with young people as co-researchers in the future.

Understanding youth advisory processes and impacts in greater depth within the context of arts and mental health can support optimising future participatory research. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore such processes and their value within the context of the field of ‘arts and health’. Such an endeavour is essential to ensure equitable research processes in this field in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context: The DanceConnect Research Project

DanceConnect was a one-year UKRI-funded interdisciplinary mixed-methods (QUAL + quan) research project led by University College London. The main aim of the study was to explore if and how online dance classes may foster social connections, reduce loneliness, and support the mental health of young people living with anxiety. The study included 27 UK-based participants aged 16–24 across two blocks of online dance classes, with the classes supporting the creation of a shared identity and improvement of mental health symptoms, for full results, see [] Alongside the design and delivery of the research and dance classes, an intergenerational advisory committee (IAC) and sub-group of a youth advisory supported the overall co-design, delivery, and dissemination, which is the central focus of this article. The IAC was made up of expert academics in the field (n = 4), members of the research team (n = 5), and the youth advisory. Five youth aged 18–25 from the UK were recruited for the advisory group, with three youth being active throughout the project in both the IAC and YA meetings. The dance practitioner of the classes also joined occasional meetings, where possible.

Youth advisors were invited to engage in five youth advisory meetings throughout the duration of the project and three intergenerational advisory committee (IAC) meetings. In addition to meetings, we hosted a training session on participatory research methods for the youth advisors, with one going on to co-facilitate a focus group discussion with dance class participants. At our youth advisory meetings, we discussed and co-created aspects of the overall design of the study, logistics for running engaging online dance classes, and the structure of classes and worked together to contextualise the river journey exercise as a creative data collection tool (see Section 2.3). At the IAC meetings, we discussed and co-created aspects of which genre of dance to deliver for young people, our participatory methods, our quantitative methods, theoretical approach, analysis, and dissemination. Particular attention was placed on fostering a trusting, supportive space for youth to be able to actively share their ideas and contribute in partnership with adult advisors. Youth advisors were also active in knowledge exchange by presenting at conferences and webinars, writing blogs, sharing updates on Twitter, and co-writing this academic article.

In this paper, we focus on the role of the youth advisory within the context of the DanceConnect study, including the broader impact the advisory had on the lives of those involved.

2.2. Theoretical Underpinnings

Our underpinning philosophy in this article aligns with recent developments in health research towards a relational approach []. Such an approach recognises that meaning is constituted in social interactions, constructing a holistic view of health that centres on shared meaning-making processes, sense of belonging, purpose, and relationality. Within this approach, affect and emotions are central [].

Participatory research is by its nature relational, with shared emotional experiences central to both doing and participating in co-research. A lack of attention to emotions is often connected with a desire for “research to appear rational, managed, and planned”, which appears contrary to the “subjective nature of relationships” and collective emotional experiences that are central to co-research [] (p. 1). Drawing on Ahmed [] and Burkitt [], we recognise relational definitions of emotions and draw on their connections to wider social constructions of (our) selves in the world.

As such, our research was underpinned by a relational, interpetivist epistemology, recognising and valuing the shared emotional processes of meaning-making and knowledge creation. Drawing from feminist epistemologies, we also aimed to recognise our situated knowledge and our embodied positionality, challenging dominant forms of knowledge construction that suggest ‘objectivity’ is possible within a research process.

2.3. Methodology and Methods

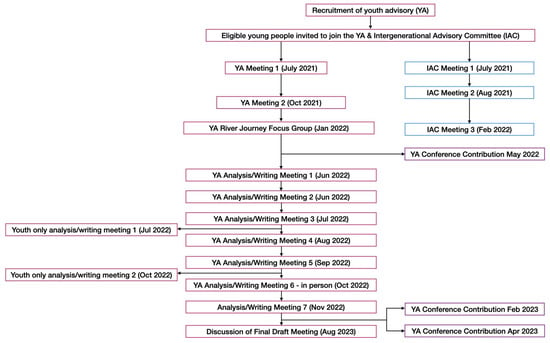

Aligning with our epistemological approach, we employed a qualitative methodology. This included collecting audio recordings of YA and IAC advisory meetings from the DanceConnect study (n = 5), a youth advisory focus group with an arts-based component (n = 1), and researcher ethnographic fieldnotes (n = 4 researchers)). The analysis and co-writing intergenerational team meetings (n = 7) that took place, alongside additional analysis meetings between YA members (n = 2), to construct this article were also a key part of the data generation process.

Youth advisory meetings took place throughout the DanceConnect study, with these meetings recorded and minutes made of the discussions. Although not formally analysed, the recordings and notes were discussed in a series of team meetings, with reflections used to inform the discussion included in this paper. In addition, a participatory focus group that utilised an art-based approach known as ‘the river journey’ was conducted with two members of the youth advisory. The focus group was auto-transcribed for use within this research. One member who was unable to attend the group additionally submitted written reflections on their experiences to be included in this research. Within the multiple team meetings that took place to produce this article, ethnographic reflections were made and discussed as a team, drawing on principles of reflexivity.

The River journey focus group was facilitated by two authors (KW, LW) with two youth advisors and lasted 52 min. The River Journey is similar to the Most Significant Change participatory monitoring and evaluation tool [] and has been adapted in different forms to be used as a reflective research and evaluation tool. It has been used internationally with children, youth, and adults to reflect on experiences over time [,,]). The tool was selected for this study as the youth advisors were familiar with it (due to having been trained on it and using it to facilitate dance participants included in the DanceConnect study), and it allowed for an arts-based process that aligned with the study. Further, it enabled reflection on temporalities and relational and emotional experiences, thereby aligning with our study’s aims to explore co-constructed values and impacts.

The youth advisors were invited to reflect on their experiences from the start, the middle, and the present and future of the research process. Advisors were invited to draw their own river journeys using images and text to reflect on strengths and challenges throughout the youth advisory process, paying particular attention to their emotions. They were then invited to share their rivers (if they chose) with the advisory and researchers. After sharing, a focus group discussion was facilitated probing further on key areas of the journeys.

In addition to the river journey focus group data, reflections were captured through journaling, dialogue, and ethnographic reflections across a 6-month analysis period. As authors and researchers of the study, we included our own autoethnographic experiences through reflexivity, which were discussed between all four authors at regular meetings. In addition to reflecting on the research itself, our process involved reflecting on our lived and living experiences, as well as subject positionality. We reflected on what we brought to the space and how our own relationship with mental health, the arts, and experiences in intergenerational coproduction impacted our roles in the project. See Figure 1 for a flow chart of our stages of the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing key stages of involvement of the youth co-researchers in the study.

2.4. Analysis

To analyse our river journey focus group data, we used a reflexive thematic analysis approach, drawing on Braun and Clarke [] and Daly et al. []. Our process involved engaging with the data and familiarising ourselves by reading and re-reading the data before mapping codes to construct key themes and exploring patterns []. As this was a small-scale reflective process, we used hand coding on shared documents, with the two youth advisors taking leadership. All authors came together in a series of 7 meetings to discuss the findings and collectively co-construct the themes. The two youth authors additionally met several extra times, working together to discuss the co-constructed findings of the research. The findings are a combination of youth advisors’ participant data during the research focus group discussions (e.g., Sophia1 & Caroline1) and the youth advisors’ personal ethnographic reflections (Sophia2 & Caroline2), alongside reflexivity from youth and adult researchers.

Our co-writing process was also a form of collective reflexivity and analysis as we worked together to co-construct and present the themes from our research. Probst [] (p. 38) argues that being reflexive essentially requires “gazing in two directions at the same time”, with the co-writing process enabling the youth advisors to analyse both their past and present selves. Co-writing meetings included time to check in on personal and professional items, explore new reflections and ideas, and silently co-write in a shared online document together. In contrast to the insights offered during the focus group discussion, Caroline2 felt that the co-writing meetings provided her with a more thorough understanding of her experiences.

2.5. Ethics

This study was approved by the University College London (Project ID: 19105/002), and all members of the youth advisory provided written voluntary informed consent. All members of the advisory were informed of the aims of the research prior to consenting and that responses would be pseudonymised for publication. Participants consented to the findings of this study being submitted for publication in peer-reviewed academic journals. Several conversations took place on anonymity, with the co-writing youth researchers (HD and GG) deciding to include their names as authors with pseudonyms being used for all youth advisory data in the article itself (the youth advisors’ quotes are presented with pseudonyms with 1s for river journey focus group discussion (e.g., Caroline1, Sophia1) and 2 s for reflective practice reflections at the start of the writing process (e.g., Caroline2, Sophia2). In addition to anonymity and confidentiality, we adhered to principles of doing no harm and reflected on power dynamics. While our ‘procedural ethics’ were planned meticulously, we were also cognisant and prioritised reflection on everyday ethics [] and were ever mindful of relationships, reciprocity, and care in our processes.

2.6. Participants

The DanceConnect research project recruited youth advisors through diverse recruitment methods, including social media (Twitter, Facebook), posters, and event stands across universities and through reaching out to community-based organisations across the United Kingdom. The call invited those aged 16–24, based in the UK, who have experiences of living with anxiety and/or experiences of research or mental health initiatives in the past. It explained that participation would involve attending a series of online meetings, with the aim of sharing youth experiences and thoughts to inform the design and delivery of online dance classes and research with and for young people. Fourteen people responded to the call and were invited to attend a meeting to discuss participation further. Of these, six people went on to attend the first youth advisory meeting, with two dropping out of the project. Accordingly, four young people aged 18 to 24 participated as advisors, with three being actively engaged throughout the whole project. Advisors’ diverse schedules with balancing school, work, and personal life encouraged us to be flexible with meeting times and styles of engagement (e.g., during meetings, through emails, etc.). As this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic and members lived across the UK, all meetings took place online.

Two YAs took an active role in co-authoring this journal article, engaging in ongoing discussion and experimentation of how best to approach presentation of the research. Although we were keen to have a clear narrative and flow, we also wished to respect and offer space for differing perspectives, not just in the name of equal contribution but for the sake of an accurate representation of data. This was challenging and required intricate negotiation, as we realised that to fully reflect on this would require a mindful recognition of the changes we went through at different stages in the study. We decided on a process that would require consideration of ourselves as plural. We chose landmark moments of the study to return to and unpack our experience of (e.g., the first youth meeting, the first intergenerational meeting, the subsequent meetings and co-design of approaches, facilitating research, analysing data, and writing).

3. Results and Discussion

The following section explores various dimensions of youth advisory engagement by the youth advisors. These are presented under three themes: shared emotional experiences of the youth advisory, creating a youth advisory community, and learning and growth through youth advisory engagement. A golden thread of wellbeing (social, emotional, mental, spiritual, and physical) weaves throughout each section. These themes not only underline the YAs’ experience but are also interconnected with the themes that were constructed for the dance class participants [].

3.1. Shared Emotional Experiences of the Youth Advisory

The first theme in our findings section is the shared emotional experiences of the youth advisory. Different environments and situations across the research process enabled and fostered different kinds of emotional experiences for YA participants.

According to McLaughlin [] (p. 69), the first stage of the research process is “one of the most emotionally demanding”. This was true in this research as the youth felt they experienced an array of mixed emotions when starting the project. Caroline2 felt surprised when the opportunity to engage in a youth advisory was presented because she had never heard of an ‘intergenerational youth advisory committee’ (IAC) and did not know what being a ‘Youth Advisor’ involved. She found the initial communications, which included formal academic terminology, to be complex and its emphasis on being ‘research’ intimidating (see Participant Information Sheet in Figure 1). This worried Caroline2 and made her feel like she did not have the academic capabilities to participate. Sophia1 similarly expressed that she “felt nervous that [she] wouldn’t be able to make valuable enough contributions”. These findings are consistent with the feelings of youth reported by Collins et al. [] (p. 4), who felt the consent form was “lengthy and too complex”. Caroline2 notes that it was her familiarity with the topic area of dance which initially encouraged her to join. These reflections indicate that the recruitment process and onboarding materials need to be tailored to highlight the importance of people with hobbies or interests relevant to the research and minimise the use of potentially complex academic terminology, as well as giving more information regarding what the research involves and the role the youth will play. These experiences also align with broader research exploring the challenges of coproduction, such as in relation to bureaucratic academic structures and academic language that may be perceived as inaccessible [].

However, despite both feeling anxious about undertaking a research-based project, the youth advisors were curious to learn more about research in practice, enhance their research skills, and understand the work of a researcher. These anxieties may have inhibited the youth advisors’ intent to participate, but they also acted as a motivator for participation. This is what Coutu [] recognises as “learning anxiety” and the paradox that anxiety can both impede learning as well as contribute to learning possibilities. The youth advisors reflected that they would need to expose themselves to moderate anxiety in order to learn more about research. Cooper et al. [] (p. 1) have investigated the relatively unexplored construct of research anxiety, and their findings reveal that “feeling underprepared” increases research anxiety, but a “positive lab environment and mentor-mentee relationships” decreases research anxiety. Therefore, it is critical that lead researchers acknowledge these anxieties and help with the preparedness of the youth advisors before starting the project and make an effort to develop positive working relationships.

As an example, before meeting the whole committee, the project’s lead researchers organised a meeting with only the youth advisors. While this may be seen as an unnecessary step (for those not attuned to working with youth advisories) that delays the start of the research, Caroline2 believes that knowing there were others like herself and discussing shared vulnerabilities put her at ease and gave her some comfort. This allowed the youth advisors to gain trust in those involved in the project, enabling deeper engagement in discussions. Salzberger-Wittenberg [] (p. 81) sums this up and states that “our capacity to function intellectually is highly dependent on our emotional state”. Therefore, while emotions are often cast as “subjectivity which clouds vision and impairs judgement”, with proper research requiring us to “[keep] one’s own emotions under control” [] (p. 7), emotions play a critical role in how we engage in research and the relationships that form. However, Caroline2 reflected that at this stage, she still felt slightly confused about where exactly they fit within the research.

The icebreakers in the second meeting, with the full intergenerational committee, provided everyone with an equal opportunity to introduce themselves. The icebreakers, which included verbally introducing oneself and sharing a creative activity that had been engaged in recently that supported mental health, helped facilitate conversation, engaged everyone in the topic of research, and supported everyone to feel comfortable. This encouraged self-disclosure, which Sprecher et al. [] describe as a valuable element of relational development that encourages rapport and connection. It also aided in restructuring “power imbalances that can be prevalent between adult researchers and young people” [] (p. 6) Sophia1 highlighted that she “felt instantly validated… my platform to speak was treated just as equally as their platform”. Lee and colleagues [] similarly highlight the value of vulnerability and recommend that adults be open to “feel[ing] vulnerable and look[ing] human” through fully engaging in games and sharing one’s own strengths and challenges [] (p. 13).

The use of breakout rooms, including a mix of youth advisors and researchers, made contributing to discussions easier and less nerve-wracking. This also enabled more one-to-one conversations to develop organically. A conversation, in particular, stood out for Sophia1 with a researcher, “I said I was an aspiring researcher and then [they] were like no you are a researcher”. This emphasises the lasting impact that these conversations have had. Caroline2 liked that all ideas and suggestions were written down, not just those that were considered ‘good’. Interactive platforms like Google Jamboard aided this by allowing everyone to actively contribute. However, Caroline2 notes that she still felt a bit nervous about making a ‘silly’ suggestion or mentioning something that had already been considered by the researchers. Despite this, the discussions contributed to the personal development of the youth advisors, with Sophia1 expressing that “I gained confidence in what I was saying so I was feeling I had a self-esteem boost”. She reflected that “I’ve started listening to my own ideas a bit more”, while Caroline1 highlighted that “it’s contributed to increased wellbeing” by helping “to get [my]self out of [my] head and thinking about different things”. This aligns with studies such as Cuevas-Parra [] that show the role of co-researching to positively impact the self-esteem and self-confidence of young people.

It has been suggested that participating in a coproduction group connected to a research project may create meaningful rituals underpinned by shared emotional experiences that generate a shared interpersonal momentum []. This interpersonal momentum is constructed through the emotional negotiation of discussions and challenges relating to the research, thereby creating emotional changes. For example, the increased confidence and self-esteem experienced by Caroline and Sophia were a result of their engagement in the youth advisory activities. This is theorised as ‘emotional energy’ in the individual derived from shared engagement in meaningful coproduced group processes [].

3.2. Creating a Youth Advisory Community

The second theme explores the co-creation of a youth advisory community. Whilst varying conceptualisations and understandings of ‘community’ exist, Delanty [] argues that a central uniting idea is that community concerns ‘belonging’, with post-modern communities able to transcend geographic location, including across digital and liminal spaces. This was the case within our research. The shared constructed community broke down physical geographic boundaries and was underpinned by a range of emotions connected to a sense of belonging. For example, Sophia1 and Caroline1 referred to feeling “included”, “involved”, and “connected”, alongside expressing a sense of “networking”, as important dimensions of the youth advisory community.

The central focus on creating an inclusive environment within a coproduced approach aligns with the values of community creation and belonging. One way in which this can be further elucidated is through the theoretical lens of ‘commoning’, which was highlighted by the youth advisors as a meaningful framework for their experiences []. Commoning is a practice of intersectional collaboration and non-discriminatory knowledge production. Developed in the early 1900s, it gained popularity in the cultural sector post-1990 [], aligning with the radical turn towards ‘care’ in institutional and social organisations. Commoning facilitates open-minded listening and mutual validation, establishing an equality of knowledge within the community (the research team + advisory). This created a meaningful dynamic within the team that was beneficial to youth and adults and supported the youth in tackling feelings of inferiority that can be cultivated in young people through frequent actions of dismissal within society. The feeling that young people are not taken seriously, or the notion that they have little to offer, is soothed by this mutual respect, listening, and steering of a project. For the youth advisory to successfully reflect, build confidence, and engage with lived experiences in a rigorous way, safety is foundational. During the focus group, Sophia1 stated that she felt it was particularly “valuable seeing how we had the academic side and then also the representative [from the dance organisation]”, fostering an environment of mutuality and equity.

Further building on this, an important and affirming facet of creating the youth advisory community was meeting each other prior to meeting the full team and IAC. This allowed for a prior understanding of both the different paths that brought individuals to apply as well as highlighting this element of differences in the drive that was now shared. Caroline1 expressed that being from “different backgrounds [she] love [d] that we [could] all contribute in a way that we [felt] valuable”. This shared moment between members of the youth advisory away from the wider research team enabled them to begin to construct their own sense of identity as the youth advisory group. Such a foundation set the stage for later feelings of validation, confidence, and self-worth, aligning with broader theories of social identity and community creation [,].

The subtle element of interpersonal diversity was also important going forward, cultivating awareness from the beginning that our participants were joining the project with different experiences. Thus, through our differences and differing opinions, we had a foundation of empathy that would feed into the design, facilitation, and analysis of the study. This community empowerment and sense of unity through acknowledgement and respect of difference established trust that enabled candid sharing of ideas, research, and experiences. This idea of flourishing communities through difference also aligns with Derrida’s philosophy; as expressed by Corlett [], community entails the mutual appreciation of differences in which all oppositions are broken down [].

Sophia2 and Caroline2 reflect that this interpersonal diversity and empowerment would not have been possible without the recognition of different strengths from varying backgrounds and interests. Especially within the academic landscape, Sophia2 and Caroline2 note the specific barriers that young people face in terms of having their views heard, particularly the exclusion of young women’s perspectives. Centring and valuing differing opinions and experiences enabled a sense of community to form for youth advisory members that were underpinned by the values of inclusion and equity.

3.3. Learning and Growth through Youth Advisory Engagement

The final theme explores processes of learning and growth through youth advisory engagement. Sophia2 and Caroline2 both felt that they had expanded their knowledge of different research methods and approaches, particularly qualitative methods. Short presentations were given at the beginning of some advisory meetings, providing an overview of the various research methods that were planned for use in the project alongside the rationale for their inclusion, setting the stage for discussion and feedback. Caroline2 notes that she learned about approaches that she had never heard of or been taught at university, for example, the illustrative river journey method. Sophia1 stated that being on the advisory, especially during project design and facilitation, allowed her the opportunity to “reflect on previous techniques [that] [she]’d used in [her] past research project”. Moreover, Caroline1 noted that simply being able to observe the study process was beneficial for her to apply to “different aspects of [her] dissertation”. For example, Caroline2 found even the consent form used by the advisory a good reference to help write her own.

Sophia2 and Caroline2 felt that this learning was due to being able to work so closely alongside experienced researchers. Caroline1 expressed that it was “interesting to hear how other people interpreted questions… things [researchers] came up with that [I] had never thought of before”. Specifically, the interdisciplinary constituents of the advisory were integral to this learning. Exemplifying this, Caroline1 highlighted that she was “learning through other researchers”. Each researcher brought their own specialisms and interests, which offered an abundance of perspectives. The language of learning “through” other people here also upholds the underpinning philosophy of our research, acknowledging the importance of relational and inter-subjective experiences to meaning-making and shared growth.

The youth advisors were keen to continue their involvement with the research and the researchers upon completion of the project, providing opportunities for continuing development. Following the identification of areas for ongoing involvement with the research team, the youth advisors participated in numerous dissemination activities (e.g., presenting at conferences and writing articles and blogs). Ahead of these opportunities, Sophia1 remarked that “I’m looking forward to a few opportunities that could be like firsts for me…like journal publication and also the conference[s]”. Therefore, the initial youth advisory has subsequently expanded to provide additional possibilities for growth than was originally intended.

One possible explanation for why the youth advisors were able to access experiences of learning and growth is that they were intrinsically motivated to participate. Both advisors wanted to gain experience in research and felt motivated at each step of the process to engage further out of personal interest. This aligns with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which explains human motivation through a spectrum of extrinsic to intrinsic motivation [,]. When one is extrinsically motivated (i.e., influenced by factors outside of oneself), it may be a transactional experience of wanting to participate in an activity for reward or feeling that one ‘ought to’ engage. On the other hand, being intrinsically motivated is characterised by one participating in an activity due to enjoyment and inherent satisfaction. Being motivated is a predictor of learning because there is an internal drive to want to keep engaging and growing, as experienced by the youth advisors.

Yet, as highlighted in our understanding of emotions, engagement with the youth advisory was not an ‘individual’ experience, and a key part of engagement was participating with others. The motivation to contribute to the youth advisory was also a shared one, whereby the inclusive spaces of the research and the meaningful relationships created enabled shared growth among members. Drawing on social movement theory, it is possible that this motivation could connect to broader social factors, too. As outlined in the Introduction of this article, there has been a burgeoning interest in coproduced methodologies and in working in more equitable ways in mental health research. Through actively engaging in this agenda, the youth advisors also contributed to this broader social movement of seeking to transform hierarchies in academia. For example, the youth advisors learned about the paucity of youth participation in research and how these opportunities are not currently widespread. They recognised that they would not have known where or how to find these opportunities had they not been contacted directly via a university mail-out to their inboxes. Sophia2 and Caroline2 appreciated the value of this experience academically and expressed awareness of how such an experience would be of great benefit to the student body at large. As such, their learning through this project has sparked an interest to advocate for more youth participation in future research, thereby joining a kind of ‘social movement’ that is developing within research to include youth voices. Nonetheless, a key question going forward is how opportunities for youth participation in research can be disseminated and advertised more widely to allow more people to get involved.

However, it must be acknowledged that both time commitments and financial circumstances impeded the youth advisors’ engagement in the project and, therefore, ultimately, their learning. Looking back, Caroline2 wishes she could have done more within the project, but she was limited by competing life demands. Additionally, more youth advisors were involved in the advisory, but their participation diminished throughout the duration. A third youth advisor expressed that “probably if I had engaged more with this project, I could see how I could have learnt a lot more … that I could have brought back into my wider experiences”, whereby limited “time between work and studying” and lack of financial remuneration made ongoing participation challenging. Competing interests, therefore, limited the learning opportunities for the youth involved. As such, the two youth advisors who were highly engaged are not representative of all youth perspectives []. Further, although financial rewards were not offered, both youth advisors felt rewarded by intangible forms, including the provision of references for graduate jobs, handwritten cards, co-authorship, and co-presenting. These contributed to their continued participation and commitment. Yet, it is recognised that payment for time is important to recognise the value of participation and to enable more people to have access to collaborative research opportunities in the future.

3.4. Impact and Reflections on Next Steps

Existing research on coproduction with youth advisories often focuses on the benefits of the research itself or the complexity of the process. While this paper touches on these areas, its primary focus is on the impact and benefit of the youth advisors’ personal and collective experiences, skill development, and mental health and wellbeing. We believe this study is a pivotal contribution to meaningfully exploring such processes within the context of arts and health research specifically. Our findings highlight that constructing an online youth advisory with regular points of connection fostered positive emotions and a sense of community alongside enabling learning and growth for youth advisors. Our study shows the importance of investing in the process, relationship building, and space for honest and vulnerable dialogue, clearly spotlighting the need for future arts and health research to invest time and resources into developing coproduced research with young people.

Further reflecting on the themes presented and reflecting on our intergenerational co-writing experience, we bring together key recommendations for other researchers establishing a similar structure. We humbly share recommendations, with the recognition that each arts and health project and coproduction experience has its own unique format and process. While these recommendations are targeted to researchers, they are also applicable to practitioners engaging in meaningful coproduction alongside young people.

3.5. Recommendations for Arts and Health Researchers Establishing Youth Advisories

- Respect, acknowledge, and value emotions.

- Consider resources available and seek to provide reimbursements (e.g., providing honorariums, budgeting for youth time, identifying intangible benefits).

- Meeting structure:

- ○

- Take time for play, creative engagement, and opening icebreakers;

- ○

- Set up meetings ahead of time and arrange for them to be at times that work for youth researchers while seeking to be flexible and adaptive;

- ○

- Make a community agreement and/or meet with youth researchers ahead of larger team meetings to discuss shared values, aims, and responsibilities;

- ○

- Have debriefs after meetings and provide opportunities for youth to provide feedback on discussions;

- ○

- Provide opportunities for smaller group discussions (e.g., breakout rooms).

- Take time to establish what youth may have in common and to share experiences and vulnerabilities that may foster a shared identity (while respecting diversity in the group).

- Consider relational and institutional ethical practices:

- ○

- Advocate for ethics committees to understand and value iterative participatory project processes and to be responsive to changing project designs;

- ○

- Engage in ongoing reflection on how to ensure mutual respect and meaningful interactions alongside critically appraising research processes in view of how to ensure equity of engagement.

- Move away from adult and youth researcher terminology, considering what other terms could be used to describe those involved (e.g., collaborators, partners).

- Reflect on terminology that may act as a barrier to communication (e.g., using formal research terminology).

- Challenge formal academic or other institutional structures that inhibit coproduction. Be open to advocating and acting for change of systems.

- Formally and publicly recognise the value of youth participation.

- Explore integrating youth advisory opportunities into teaching structures at universities, e.g., offering it as a placement as part of a qualification or sharing data to allow students to write dissertations on their youth advisory experiences and projects.

4. Conclusions

The value constructed through research participation in arts and mental health research is often overlooked in favour of a focus on the ‘impact’ of arts engagement or organisational processes. In this study, we explored what it means to be a youth advisor on a research project focusing on mental health, recognising that the research process itself holds great potential to support young people’s wellbeing and positively impact wider life experiences. Although our study is small in scale and coproduction can provide extra challenges (e.g., time, resources), we see our reflections as a foundation to encourage future participatory arts and mental health research, working towards a more equitable future where youth are central to all aspects of the research process. Such a vision is vital both to ensure quality research and to support youth mental health in a time of societal flux and increasing mental health challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.V.W. and K.W.; Methodology, L.H.V.W., H.D., G.G. and K.W.; Formal analysis, L.H.V.W., H.D., G.G. and K.W.; Investigation, K.W.; Data curation, L.H.V.W.; Writing – original draft, L.H.V.W., H.D., G.G. and K.W.; Writing – review & editing, L.H.V.W., H.D., G.G. and K.W.; Project administration, K.W.; Funding acquisition, K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Research Network, which is funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) (grant reference: ES/S004440/1). Their support is gratefully acknowledged. Any views expressed here are those of the project investigators and do not necessarily represent the views of the Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Research Network or UKRI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the University College of London (UCL) Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 19105/002). All recruitment materials received ethical approval. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were informed of the aims of the research and that responses would be anonymised (quantitative) or pseudonymised (qualitative) for publication. Participants consented to the results of the study being submitted for publication in peer-reviewed academic journals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data from this study are not being publicly archived for use by other researchers because the data contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. The University College of London Research Ethics Committee has restricted the use of the data to University College of London researchers only. To discuss the conditions of this availability further, please email the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the other Co-Investigators of the Dance/Connect project who informed the development of this study, namely Hei Wan (Karen) Mak and Saoirse Finn. Further, the authors would like to thank the other Youth Advisory and Intergenerational Advisory Committee members for their time and contributions to the study that informed this publication, including youth advisors Jamie Brown and Rosie Mackley, and senior academic advisors Liliana Araújo, Julian Edbrooke-Childs, and Bronwyn Tarr. We would also like to extend our gratitude to dance practitioner, Bridie Gane, and Dance Base for their partnership. Finally, the authors would like to thank the UKRI Loneliness & Social Isolation in Mental Health Research Network for providing funding for the Dance/Connect project (Grant reference: ES/S004440/1) and UCL for providing the funding to publish this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Collins, T.M.; Jamieson, L.; Wright, L.H.; Rizzini, I.; Mayhew, A.; Narang, J.; Tisdall, E.K.M.; Ruiz-Casares, M. Involving child and youth advisors in academic research about child participation: The Child and Youth Advisory Committees of the International and Canadian Child Rights Partnership. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmellon, C.; Tisdall, E.K.M. Children and Young People’ s Participation Rights: Looking Backwards and Moving Forwards. Int. J. Child. Rights 2020, 28, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Parra, P.; Tisdall, E.K.M. Child-led research: Questioning knowledge. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Hunleth, J. Beyond on or with: Questioning power dynamics and knowledge production in ‘child-oriented’ research methodology. Childhood 2011, 18, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Currie, V.; Saied, N.; Wright, L.H.V. Journey to hope, self-expression and community engagement: Youth-led arts-based participatory action research. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Scott, S.D.; Campbell, A.; Elliott, S.A.; Brooks, H.; Hartling, L. Research-and health-related youth advisory groups in Canada: An environmental scan with stakeholder interviews. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1763–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.M.; Wright, L.H.V.; Machado, C.; Niyogi, O.; Singh, P.; Shields, S.; Hope, K. Online intergenerational participatory research: Ingredients for meaningful relationships and participation. J. Particip. Res. Methods 2022, 3, 2–17. Available online: https://jprm.scholasticahq.com/article/38764.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, K.; Bowman, D.D.; Coen, S.E.; El-Bagdady, M.A.; Ergler, C.R.; Gilliland, J.A.; Mahmood, A.; Paul, S. Conceptualizing youth participation in children’s health research: Insights from a youth-driven process for developing a youth advisory council. Children 2018, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report no. 67; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/what-is-the-evidence-on-the-role-of-the-arts-inimproving-health-and-well-being-a-scoping-review-2019 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Dow, R.; Warran, K.; Letrondo, P.; Fancourt, D. The arts in public health policy: Progress and opportunities. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e155–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbranca, R.; Dâmaso, M.; Blaga, O.; Kiss, K.; Dascl, M.D.; Yakobson, D.; Pop, O. CultureForHealth Report. Culture’s Contribution to Health and Well-Being. A Report on Evidence and Policy Recommendations for Europe. CultureForHealth. Culture Action Europe. 2022. Available online: https://www.cultureforhealth.eu/app/uploads/2023/02/Final_C4H_FullReport_small.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. The Arts for Health and Wellbeing: Inquiry Report. United Kingdom: All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. 2017. Available online: https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/file/b29823535_Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Mullen, M.; Walls, A.; Ahmad, M.; O’Connor, P. Resourcing the arts for youth well-being: Challenges in Aotearoa New Zealand. Arts Health 2021, 15, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, K.A.; McFerran, K.S. Perceptions of mental health assessment and resource-oriented music therapy assessment in a child and youth mental health service. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 2022, 31, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hense, C. Scaffolding Young People’s Journey from Mental Health Services into Everyday Social Music Making: A Pilot Music Therapy Project. Voices World Forum Music Ther. 2019, 19. Available online: https://voices.no/index.php/voices/article/view/2580/2672 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Teixeira, S.; Augsberger, A.; Richards-Schuster, K.; Sprague Martinez, L. Participatory research approaches with youth: Ethics, engagement, and meaningful action. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 68, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, S.; Wright, L.H.V.; Waen, K.; Astroom, E.; Nicholls, L.; Dingle, G.; Warran, K. Advancing the social cure: A mixed-methods approach exploring the role of online group dance as support for young people (aged 16–24) living with anxiety. Front. Psychol. 2023, 4, 1258967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, S.; McKie, L. Care and caring: An ecological framework. Area 2019, 51, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.H.; Tisdall, K.; Moore, N. Taking emotions seriously: Fun and pride in participatory research. Emot. Space Soc. 2021, 41, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. The Cultural Politics of Emotion; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt, I. Emotions and Social Relations; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Willetts, J.; Crawford, P. The most significant lessons about the Most Significant Change technique. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.H.V. Play-Based Research Approach: Young Researchers’ Conceptualisations, Processes, and Experiences. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Warran, K.; Wright, L.H. Online ‘chats’: Fostering communitas and psychosocial support for people working across arts and play for health and wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1198635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, J.; Kellehear, A.; Gliksman, M. The Public Health Researcher: A Methodological Approach; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, B. The eye regards itself: Benefits and challenges of reflexivity in qualitative social work research. Soc. Work Res. 2015, 39, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M.; Gillam, L. Ethics, reflexivity, and ‘ethically important moments’ in research. Qual. Inq. 2004, 10, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C. The feeling of finding out: The role of emotions in research. Educ. Action Res. 2003, 11, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warran, K.; Greenwood, F.; Ashworth, R.; Robertson, M.; Brown, P. Challenges in co-produced dementia research: A critical perspective and discussion to inform future directions. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutu, D.L. The Anxiety of Learning. The HBR Interview. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K.M.; Eddy, S.L.; Brownell, S.E. Research Anxiety Predicts Undergraduates’ Intentions to Pursue Scientific Research Careers. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2023, 22, ar11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzberger-Wittenberg, I. The Emotional Climate in the Classroom. In Priorities in Education; Alfred, G., Fleming, M., Eds.; Fieldhouse Press/University of Durham: Durham, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K.; Smith, S.J. Emotional geographies. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2001, 26, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S.; Treger, S.; Wondra, J.D. Effects of self-disclosure role on liking, closeness, and other impressions in get-acquainted interactions. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 30, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Parra, P. Co-researching with children in the time of COVID-19: Shifting the narrative on methodologies to generate knowledge. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406920982135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Waring, J.; Timmons, S. The challenge of inclusive coproduction: The importance of situated rituals and emotional inclusivity in the coproduction of health research projects. Soc. Policy Adm. 2019, 53, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanty, G. Community; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, G. Co-Production, Commoning, and Community Empowerment. 2022. Available online: https://mentalhealthresearchmatters.org.uk/commoning-coproduction-mental-health (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Elias, A. Art and the Commons. ASAP 2016, 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity A Read. 1979, 56, 9780203505984-16. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten, J.; Haslam, C.; Alexander, S.H. (Eds.) The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being; Psychology Press: Londun, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Corlett, W.S. Community without Unity: A politics of Derridian Extravagance; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hawke, L.D.; Relihan, J.; Miller, J.; McCann, E.; Rong, J.; Darnay, K.; Docherty, S.; Chaim, G.; Henderson, J.L. Engaging youth in research planning, design and execution: Practical recommendations for researchers. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).