Abstract

Material failure by adiabatic shear is analyzed in viscoplastic metals that can demonstrate up to three distinct softening mechanisms: thermal softening, ductile fracture, and melting. An analytical framework is constructed for studying simple shear deformation with superposed static pressure. A continuum power-law viscoplastic formulation is coupled to a ductile damage model and a solid–liquid phase transition model in a thermodynamically consistent manner. Criteria for localization to a band of infinite shear strain are discussed. An analytical–numerical method for determining the critical average shear strain for localization and commensurate stress decay is devised. Averaged results for a high-strength steel agree reasonably well with experimental dynamic torsion data. Calculations probe possible effects of ductile fracture and melting on shear banding, and vice versa, including influences of cohesive energy, equilibrium melting temperature, and initial defects. A threshold energy density for localization onset is positively correlated to critical strain and inversely correlated to initial defect severity. Tensile pressure accelerates damage softening and increases defect sensitivity, promoting shear failure. In the present steel, melting is precluded by ductile fracture for loading conditions and material properties within realistic protocols. For this steel, if conduction, fracture, and damage softening are artificially suppressed, melting is confined to a narrow region in the core of the band. However, for other metals with vastly different physical properties, or for more diverse loading conditions, melting has not been unequivocally ruled out, even if fracture and conduction are permitted.

MSC:

74A15; 74A20; 74C20; 74H10; 74H55; 74R20

1. Introduction

Shear localization is a prevalent failure mode in solid materials that undergo strain-softening mechanisms. In crystalline metals deformed at high rates, near-adiabatic conditions are obtained, promoting a build up of local internal energy and temperature from plastic work, in turn leading to thermal softening as dislocation mobility increases with temperature. A mechanical instability ensues, beyond which localization into a thin band of very high shear strain and strain rate occurs [1,2]. Shear banding is often accompanied by damage mechanisms such as cracking and void growth [3,4,5,6,7], and melting is theoretically possible if temperatures become large enough [8]. In this work, “damage” and “ductile fracture” are used to refer changes in local material structure—distinct from phase transformation and deformation twinning and not captured by thermal softening alone in the context of continuum plasticity theory—that induce degradation of local strength.

Experiments and models on adiabatic shear spanning the previous four decades are reviewed in the monograph [1] and more recent article [2]. Most previous continuum modeling of adiabatic shear localization in metals, be it analytical [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] or numerical [18,19,20,21,22,23,24], did not explicitly address fracture or melting mechanisms. However, several continuum damage mechanics-type models for adiabatic shear [25,26,27,28] represented degradation distinctly from purely thermal softening. Mathematical analyses in Refs. [29,30] considered localization in strain-softening solids, without explicit thermal effects, that could be attributed to damage processes.

More recently, phase-field models [31,32,33,34,35,36,37], extending ideas for depicting brittle fracture and structural transformations in elastic solids [38,39,40,41,42,43], have addressed ductile fracture and adiabatic shear localization in elastic–plastic solids. A common element of many models is a contribution of some fraction of energy from plastic work to the net driving force for fracture [31,32,33,35,36,37,44], supported by experiments revealing the importance of microstructure- and damage-softening relative to thermal softening [45,46]. Furthermore, many continuum damage and ductile-fracture phase-field models include a threshold inelastic energy density at which damage nucleates [27,28,35,36,47], as opposed to classic phase-field fracture mechanics wherein any elastic energy can initiate diffuse cracks [43,48]. Timing of cracking or void nucleation relative to localized flow varies among metals with different compositions and microstructures [4,5,6,7,49,50]. Cited experiments usually suggest damage mechanisms accompany or follow localization, rather than precede it, since cracks and voids are scarcely seen outside shear bands in those materials tested.

Direct evidence of melting has been reported within dynamic shear bands in various titanium and steel alloys [49,51,52,53]. Known prior analyses of adiabatic shear did not include the thermodynamics of melting, even though local temperatures far exceeding the melting point of iron or steel can be predicted inside the shear band [8,11,14,54]. Phase-field models combining mechanics of elasticity and thermodynamics and kinetics of melting and solidification exist [55,56,57,58], but these do not consider plastic deformation or adiabatic shear. A continuum model described flowing material within a shear band using a Bingham model with Newtonian viscosity [59], at temperatures below the ambient melt temperature. Therein, the calibrated viscosity was so low for three different metallic systems that the constant, rate-independent part of the shear stress dominated.

A recent theoretical study [8] advanced the analyses of Molinari and Clifton [11,12,14] to account for influences of superposed pressure, external magnetic fields, and solid-solid phase transformations on adiabatic shear localization. Results showed how loading conditions and solid-solid phase transformations can promote or inhibit strain localization in iron and a high-strength Ni-Cr steel. Herein, treatments of Refs. [8,11,12,14] are further extended to account for damage (i.e., ductile shear fracture) and melting (i.e., solid–liquid transformation) processes. Criteria for localization into a band of infinite shear [11,12] are analyzed, and methods for calculating the average shear strain at which localization ensues are developed. The latter require numerical iteration and numerical integration, as closed-form expressions for critical strain cannot be derived analytically. A ductile fracture component of the model further addresses the additional “average” shear strain accommodated by the sample after localization, accounting for the effective shear displacement jump across the band whose shear strain approaches infinity and width approaches zero. This allows for representation of a gradual softening behavior in the macroscopic shear stress versus shear strain response as regularly witnessed experimentally [5,6,28,47,60]. Overly abrupt drops to zero stress upon localization [8,11,12] were criticized by Molinari and Clifton [12] as a notable deficiency of their original approach, therein speculated a result of poor resolution of defects.

As assumed or justified in prior works [1,8,12,61] for materials (e.g., steels) and average strain rates (e.g., 103–104/s) of present interest, regularization mechanisms of heat conduction and inertia are omitted to enable a tractable analysis without recourse to advanced numerical methods such as finite elements or finite differences. Similarly, to allow localization into a damaged region of infinitesimal thickness, the ductile fracture component of the formulation omits gradient regularization of phase-field theory [62], and Newtonian viscosity of molten material is likewise omitted in the limit of singular surfaces [8,11,12,63]. Any remaining (implicit) regularization is furnished by strain-rate sensitivity [64]. Apart from phase-field methods that introduce regularization via order parameter gradients, other generalized continuum theories, including various strain-gradient, micromorphic, and nonlocal types, can instill material length scales in solid mechanics problems (e.g., [29,30,65,66,67,68,69]). These generalized approaches, though promising with regard to stability and localization problems, are outside the scope of the current analysis. The present results are interpreted as a limiting case: predictions would be expected to underestimate conditions for localization given the absence of other regularization mechanisms [1,61]. An initial defect (e.g., strength perturbation) of greater intensity than imposed or predicted here and in Refs. [8,11,12] would seem needed to instill the same post-peak shear strain.

This article consists of seven more sections. In Section 2, a general 3D continuum framework is outlined, including constitutive fundamentals and thermodynamics. In Section 3, specialization of the framework to simple shear and pressure loading is undertaken. Constitutive model components for viscoelasticity, ductile fracture, and melting are introduced in this context. In Section 4, localization criteria are examined, and methods of calculation of critical shear strain and average stress-strain response are explained. In Section 5, properties and results are reported for a high-strength steel and compared to experimental observation. In Section 6, effects of variations in material parameters and loading conditions on localization behaviors are explored. In Section 7, modeling details, collective results, and limitations are discussed. In Section 8, conclusions consolidate the main developments. A list of notation precedes the bibliography. Standard conventions of continuum mechanics are used (e.g., Refs. [1,70]), with vectors and tensors in bold font and scalars and scalar components in italics. A single Cartesian frame of reference is sufficient for this work.

2. 3D Formulation

The general constitutive framework combines elements from Refs. [8,31,42,43,55,56,57,71]. Electromagnetic effects considered in Refs. [8,71] are excluded, but phase-field concepts for fracture [31,42,43,44] and melting [55,56,57] are now added. The material is isotropic in both solid polycrystalline and liquid amorphous states, and is assumed fully solid in its initial configuration.

Inertial dynamics, heat conduction, and surface energies are included the complete 3D theory, as are thermal expansion and finite elastic shear strain. These features are retained in Section 2 for generality and to facilitate identification and evaluation of successive approximations made later. Furthermore, retainment of such physics in the general formulation will allow a consistent implementation of the complete nonlinear theory in subsequent numerical simulations, for potential future comparison to the results of semi-analytical calculations reported in Section 5 and Section 6.

2.1. Constitutive Model

Denote the motion of a material particle at reference position by spatial coordinates = . Gradients with respect to and are written as and , and a superposed dot denotes the time derivative at fixed . The deformation gradient and its determinant J are decomposed into a product of three terms [70,72,73], with thermoelastic deformation, plastic deformation from dislocation motion, and the total inelastic deformation from damage and melting:

None of need be individually integrable to a vector field [70]. Denote dimensionless order parameter fields for melting by and damage by , where

Deformations of solid and liquid phases are not tracked individually at a point , so each is effectively assigned the same overall deformation gradient at time t. Accordingly, is interpreted equivalently as the local mass fraction or local volume fraction of molten material. On the other hand, need not represent the local volume fraction of voids or free volume, but rather is a generic indicator of local strength loss.

In a body of reference volume , reference conditions are . Calculations do not consider bodies with initial liquid phases or with initial damage represented by nonzero values of and , respectively. If the material contains initial defects associated with damage entities (e.g., pores, micro-cracks, or other intrinsically weak zones), represents only the additional damage incurred after loading begins, potentially nonzero only for . In Section 3.3, a relationship between initial strength perturbation and an initial damage variable physically analogous to, but mathematically distinct from, , is introduced.

Deformation is a function of state (i.e., of order parameters), plasticity is isochoric, and symmetric thermoelastic deformation is measured by with isochoric part :

Denote by a scalar internal state variable field associated with plastic deformation processes (e.g., a dimensionless measure of dislocation density). Let be absolute temperature. Helmholtz free energy per unit reference volume of the solid is , consisting of thermoelastic strain energy W, thermal energy Q, microstructure energy R, and gradient surface energy :

Denoted by is a reference temperature, and . Non-degraded isothermal bulk modulus is assumed the same in solid and liquid phases for neutral and compressive states wherein . Volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion is assumed the same in solid and liquid. The non-degraded shear modulus of the solid is . Thermoelastic strain energy combines a logarithmic equation of state [74] with a polyconvex shear contribution [62]:

Let be an interpolation function between solid and liquid states satisfying . Let be a degradation function satisfying , where is the left-continuous Heaviside function. Moduli are interpolated as follows, noting as and , in tension and :

Constants or , when nonzero, enable remnant strength when a material element is fully fractured or melted, and in compression. Cauchy pressure p and deviatoric Cauchy stress then follow from (5), with the spatial deviatoric lattice strain:

Specific heat per unit volume is assumed the same for solid and liquid phases and is idealized as independent of . Latent heat of fusion per unit reference volume of the solid is the constant , positive for the usual case of higher internal energy of the liquid than the solid coexisting at the same . Herein . An equilibrium transformation temperature is the constant . At this temperature, in the absence of elastic deformation, stored energy of microstructure, and gradient surface energy, the free energy densities of solid and liquid phases are equal, whereby is interpreted as the melt temperature. Thermal energy is

Here is a melt instability temperature, and constant [55] .

Denote as the cohesive energy per unit reference volume [42,62], presumed matching in solid and liquid phases here for simplicity. More generally, could depend on and , to allow for different, temperature-dependent cavitation thresholds in solid and liquid. However, data to justify such generalizations, incurring additional driving and resistive forces for melting and fracture and increasing model complexity and computational burden, appear difficult to measure and do not seem to exist for the material analyzed in Section 5. Microstructure energy is

with a dimensionless function of . The first term on the right in (10), for stored energy of dislocations, is scaled by the shear modulus [70], the second is a double well for phase boundaries [55,56,57], and the third, with a dimensionless function, is for homogeneous fracture [42,43]. Constant is the fraction of stored energy of cold work released upon melting.

Let and be surface energies for solid–liquid boundaries and cracks, respectively, and let be regularization length constants. Gradient energy of internal surfaces is then the usual sum of quadratic forms [43,55], where here surface energies can generally depend on order parameters:

Surface tension [55,56,57] is omitted from R and for brevity; it could be included by multiplying right sides of (10) and (11) by J and replacing with in (11).

For later use, define first Piola–Kirchhoff stress , elastic second Piola–Kirchhoff stress , Mandel stress , and the thermoelastic entropy constitutive relation as

With and U being entropy and internal energy per unit volume, the referential heat flux, and isotropic Fourier conductivity generally dependent on temperature, phase, and damage, the following apply:

2.2. Balance Laws and Dissipation

Standard local forms [70,74] for conservation of mass and momentum are invoked, where and are referential (solid, undeformed and undamaged) and spatial (deformed, possibly molten, and possibly damaged) mass densities, is body force per unit mass, and is particle velocity:

Let be the outward normal to material body on external boundary . Global forms of the balance of energy and entropy inequality are as follows, the first extending classical continuum mechanics to account for surface energetics of order parameters [43,62,75]:

The divergence theorem, (14), and differentiability give local versions of (15) and (16):

Define the internal dissipation as follows, applying the first of (13) and (17):

The second law (18) is, from (1), (3), (12), (13), and chain-rule differentiation of (4),

Expansion of with (9), and (17), then give the temperature rate, where the specific heat per unit volume at constant volume obeys :

3. Dynamic Shear with Pressure

The problem analyzed in Section 3, Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6 is similar to that of Ref. [8]. However, magnetization and magnetic fields considered in that work are omitted here, as are solid–solid phase transformations. Instead, solid–liquid transformations and ductile fracture are now included. It is possible to posit a reduced set of governing equations for shear band analysis from the outset, without referencing the full 3D constitutive model of Section 2 that encompasses thermoelasticity, conduction, gradient regularization, and inertia. However, that full formulation is used as a starting point here to clarify the simplifying assumptions needed for mathematically tractable limit analysis in later sections.

3.1. Geometry, Loading Conditions, and Governing Equations

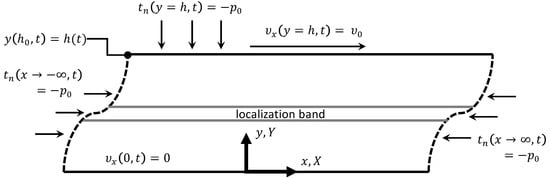

Shown in Figure 1 is the transient boundary value problem of present study. Let and be Cartesian reference and spatial coordinates. The material domain is of initial height and current height . The slab is infinitely extended in - and - directions. The following mixed boundary conditions are invoked. Denote by a constant velocity at , with vanishing velocity at . Constant pressure field is applied as normal traction on all boundaries for . Though not depicted in Figure 1, tangential traction from at each cross section exists. Letting be coordinates minus application of , can be unequal to the Y value of the planar boundary of the stress-free slab due to compressibility (i.e., depends on ). Pressure is applied slowly so is treated as an isothermal and quasi-static pre-loading. Then for dynamic shearing when , and are thermally insulated.

Figure 1.

Boundary value problem for simple shear with superposed static pressure: tangential velocity at is , normal traction is , including . Slab is infinite in directions; initial (current) height of slab is (h). Slab is thermally insulated: at and at for . Initial variable and temperature can vary modestly over .

For , while the body is shearing, h may displace from to maintain at . This would occur if a volume-changing structural change such as melting or void growth is driven by shear. Note is constant for : acceleration from a resting state to an initial velocity gradient is not modeled. For , with infinite boundaries, spatial fields depend at most only on , a common assumption in analytical studies of shear bands [1,11,12,13,76]:

Any single localization band, within which differs from most of the rest of the domain, is oriented as in Figure 1, but multiple parallel bands are allowable. Properties and initial temperature are constant with respect to x and z but need not so with respect to y. Perturbations in initial strength and temperature [14] can trigger localization at critical y locations.

Reference configuration covered by is a model construct for analysis and need not be attained in experimental practice. Pressure is removed instantly at fixed from an unsheared state, before is applied. By construction, , , and in this reference configuration. Almost everywhere, and . Initial perturbations in and are permitted, with magnitudes so small that initial perturbations in J, p, , and can be omitted.

Since the constitutive model of Section 2 is isotropic, the only nonzero Cauchy stress components are , , , and , and the nonzero heat flux component is . Taking henceforth and using (25), the second of (14) and heat conduction expressions in (13) and (24) are

Regarding the deformation gradient, non-vanishing components of are , , , and . For generic differentiable function (e.g., (25)), , and . From the second of (25), compatibility conditions [70] necessitate

Forms of , , , and satisfying (28) are postulated a priori [8], based on Figure 1. The reference configuration is unstressed, and includes the isothermal elastic volume change from initial pressurization by . Motion and deformation gradient terms, written in matrix format, are

The thermoelastic term contains spatially homogeneous volume change and shear . The total shear after thermoelastic volume change in the last of (31) is . Plastic deformation is a simple shear . Inelastic deformation from damage and melting consists of simple shear and strain normal to the band, with volume change , both interpolated as follows [41,43,55]:

Interpolation functions between solid and liquid, and between undamaged and failed states, are

Material constants are , and , any of which can be zero, positive, or negative. These constants are multiplied by or to give any structure change-induced shear strains and volume changes at or . Mass densities of solid and fully liquid states are and , respectively. When damage manifests physically as induced cavities or pores, then the quantity can be interpreted as the void volume fraction at the locally failed state. Notice that accounts only for volume changes induced during deformation, and not for effects of initial defects (e.g., does not account for initial porosity independent of that is implicitly included in ).

Three approximations are introduced to simplify (35) and (36) [8]. First, elastic shear is assumed small so terms of are negligible. Second, thermal expansion in is omitted (e.g., ), typical in analysis of shear bands [1,11,12,76]. Third, terms of , are omitted in the prefactor of (35). This implies local volume changes from melting and porosity remain small. For ferrous metals studied in Section 5 and Section 6, such volume changes, both expansive, cannot exceed %, which would lead to overestimation of stress, at most, by the same percentage. Thus, (35) reduces to

Since , for , consistent with (25).

Initial pressure, if tensile, is assumed small enough that no damage is incurred prior to shear loading, and subsequently, changes in B from shear-induced melting and fracture are ignored in the second of (37). Transient increases to that would be needed to offset reduction of B with increasing when are omitted. Thus, (37) is most accurate for neutral or compressive states with . Since , the second of (26) is now obeyed unconditionally when . The first of (26) is . If is independent of y, then inertial force is negligible.

Through (30)–(37), dissipation allotments from plastic and inelastic structure deformations of melting and fracture in the energy balance of (24) and entropy inequality of (20) are

Conjugate forces and of (21) and (22) become, with and constants for brevity,

Temperature rate (24) becomes, with generally transient Taylor-Quinney factor [77,78] , , , , and for brevity and simplicity,

In (43), accounts for stored energy of cold work but not energies of fracture and melting.

Let an arbitrary rigid body rotation be . Strain energy W and stress are unaffected by transformations of forms with . Different choices of can affect partitioning of dissipation among inelastic deformation modes. Currently setting , motivated by physics specific to Figure 1 and metal plasticity, is not arbitrary [70,79].

Note that hydrostatic pressure is fully applied before application of the shear velocity. Volumetric expansion or contraction in is time-independent during the shear process and does not affect the velocity field. The shear velocity and resulting shear displacement are independent of x and automatically fulfill periodicity conditions. Physically, the problem envisions a torsion or simple-shear experiment conducted in a pressurized chamber. In reality, is defined relative to atmospheric pressure ( kPa); the standard Kolsky-bar experiment is not performed in vacuum. After is applied, the problem is plane strain with respect to the z coordinate.

3.2. Approximations and Reduced Governing Equations

The following additional assumptions are implemented later to facilitate analysis, in conjunction with prior assumptions that , and are small compared to unity, and :

- Inertia is omitted (), as in Refs. [8,11,12];

- The shearing response is idealized as rigid-viscoplastic, as in Refs. [1,8,11,12];

- Gradient regularization is omitted () [42,62], and ;

- Heat conduction is omitted (), as in Refs. [8,11,12];

- Taylor–Quinney factor is constant (); Refs. [8,11,12].

From the first assumption, the lone non-trivial equilibrium equation in the first of (26) becomes

Coordinates of any two material points the slab with shear stresses , are written , . Recall and from (30) and (31) that . Physical suitability of the first and fourth assumptions (i.e., omission of inertia and conduction) for materials and loading conditions of present interest, namely steels deformed in torsion at rates /s/s] is discussed in Refs. [1,8,11,12,61]. Limitations of these assumptions are reconsidered in Section 5.2 and Section 7. Acceleration is more important at much higher rates, conduction at much lower rates.

From the second assumption above, rigid viscoplasticity sets but can remain finite. Consistent with this limit, , , as , and quadratic deviatoric strain energy . With on the order of unity, the shear strain and shear strain rate, with explicit viscoplastic and inelastic structural deformations, reduce to

If , shearing from slip must exceed that from fracture and melting. If , then is not impossible.

The third assumption discards some energetic contributions of boundary layers between solid and liquid and between undamaged and fully fractured material. While this assumption neglects certain physics resolved by phase-field theories of gradient type [43,55,56], it allows for modeling of spatial discontinuities in order parameters, and thus does not implicitly forbid jumps in shear strain and temperature needed for the locally infinite- description of adiabatic shear bands [8,11,12,14] invoked in Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6. Were the gradient energy contribution from included, a sharp spatial change or jump in would be impossible due to the nearly infinite or infinite energetic barrier from of (11). A similar remark applies for the gradient energy contribution from in (11). Since primary driving forces for local increases in and are later identified with and , respectively, the same barriers could restrict large increases in and to zones or bands of finite width. A jump to an extreme value of or for material in an infinitesimal-width band relative to its surroundings would engender a discontinuity in or that is inadmissible in a gradient-regularized theory. Conductivity would also restrict the minimum width of a shear band to avoid infinite contributions to dissipation in (20) and temperature rate in (43), as temperature gradients approach infinite magnitudes.

Combining the third assumption with the second,

Finally, from the fourth and fifth assumptions, the first inequality in (20), the first equality in (43), and the total cumulative plastic work are approximated, respectively, by

From (45) with , if or , then . In that case, the fifth assumption implies can be transient if , the latter implicitly affected by dissipative contributions from inelastic structural shears. In Section 5 and Section 6, .

Models for plasticity, ductile damage, and melting following in Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5 are specialized to the dynamic, adiabatic, pressurized simple shear problem of Section 3.1, simplifying assumptions of Section 3.2, and relatively strong, ductile polycrystalline metals like structural steels. Different models would be needed for other loading regimes and material classes (e.g., quasi-statics, brittle solids).

3.3. Viscoplasticity

A power-law viscoplastic flow rule [8,11,12,13] relates to Kirchhoff shear stress :

Denoted by and are a reference strain rate and rate sensitivity. Flow stress consists of pressure-, phase-, and damage-dependent static yield stress , strain hardening (or softening) function , and thermal softening (or hardening) function .

Internal state variable change is associated with strain hardening, most often linked to increases in dislocation density [70,80]. For monotonically increasing , the simplest realistic representation of associated with dislocations is, with initial value close to unity,

In the rightmost expression, obtained from (43) and the fifth assumption of Section 3.2 with , is an initial condition related to stored energy from initial dislocation density at Y.

Fractured or molten material is assumed to have degraded strength. Classical dislocation plasticity theory [70,80] presumes is proportional to shear modulus . Thus is interpolated akin to in (6) via functions and . As in Refs. [8,11,12,13], h and are power-law forms:

Here, is strength of the solid with pressure scaling, while , n, and are dimensionless constants. Strength depends linearly on via the pressure derivative of shear modulus, [8]:

To avoid unnecessary complexity that would be eliminated by the rigid-viscoplastic assumption, pressure scaling of was omitted in elastic strain energy (5).

Flow stress is, inverting (48), as follows:

In metals, the strain hardening exponent n is usually positive, and thermal softening exponent is usually negative. These conventions are not enforced a priori as restrictions in the theory, however.

The present power-law functions for strain hardening, strain-rate hardening, and thermal softening are sufficient for matching torsion data on steel analyzed in Section 5. Their simple forms facilitate mathematical analysis [8,11,12] while including the necessary basic physical ingredients. Sophisticated models are available elsewhere, for example in Refs. [1,81,82], that may be better-suited for modeling more complicated 3D deformation histories in ductile metals.

Accommodating usual degradation functions from continuum-damage [70,74] and phase-field mechanics [43] the function first introduced in (6) and now entering (50) is

Material constants are and , recalling the latter allows for remnant strength at .

Initial deviation , if positive as assigned by convention in Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6, accounts for strength defects. These could be initial micro-cracks, pores [83], texture variations, weak interfaces at grain boundaries [77], inclusions, or another microstructure feature that reduces strength. Deviation can be related to time-independent “damage” parameter with linear degradation function :

This is akin to (53) with , , and . In the present theory, it is advantageous to assign distinct values to and , whereby is used as the standard initial condition. This allows and to describe different weakening mechanisms (e.g., grains locally oriented favorably for easy slip, unrelated to ductile fracture).

If the solid has mild rate sensitivity (i.e., m small versus unity), an assumption used in some, but not all, steps of prior analyses [8,11,12] replaces local strain rate in (52) with average :

More accurate flow stress expression (52) is used in the momentum balance. Approximation (55) is used to estimate dissipative contributions to temperature [11,12] and structure kinetics [8] if is unknown.

3.4. Shear Fracture

Classical, elastic-brittle phase-field fracture models [39,43,48,84] are inadequate for describing ductile failure in adiabatic shear bands because they do not account for coupling of plastic deformation to effective fracture toughness and fracture kinetics. Rather, similar to Refs. [31,32,35,36,37,44,85,86], here some fraction of plastic working is used as a driving force for shear fracture.

Let be a dimensionless constant quantifying this fraction. Degradation initiates when a threshold level of plastic work has been attained [27,28,35,36,85,87]. Set , where . Accordingly, initial defects and tensile pressure are assumed to linearly reduce threshold , analogously to static yield-strength terms h and in (52) and (51).

Ensuring net non-negative dissipation from plastic work and ductile fracture, the following kinetic law for the order parameter rate, , for dynamic shear degradation is postulated:

Heaviside function limits the solution to physical domain . Substituting (46) into the first of (56) and enforcing gives a nonlinear differential equation at each :

where . The right side of (57) is non-negative since and . The operation on the left ensures (i.e., irreversible damage), and by the factor on the right when resistance within on the left is non-positive. This equation must usually be integrated numerically for using (52) along with evolution equations for and .

To demonstrate model features, apply (55) in each of (47) [8,11,12] and assume , meaning no explicit inelastic shear strain from fracture. For monotonically increasing , assume functional forms and exist. Denote as the value of at t when fracture initiates, as . Then (57) is separable and can be integrated for at fixed , , and y:

Now take , in (53), , and assume . Then (58) produces

Plastic work , . When , the trivial solution is , and when . Resistance to fracture at a given value of is afforded by ; large , and defects promote fracture. If , with ductile damage expansive (i.e., ) tensile pressure causes fracture as soon as via in (57).

Though not exercised in this work, the theory admits to depend on , , and in addition to . Temperature dependence may be useful to capture ductile–brittle transitions. Dependence on is likely redundant since already reduces upon melting via in (50).

3.5. Melting

To ensure non-negative dissipation from melting or solidification, the Allen–Cahn or Ginzburg–Landau equation [55,56,57] is often invoked for kinetics of , especially when modeling boundary layers of partially molten material. Here, since gradient regularization is omitted and solidification is less relevant, a linear relaxation model for phase transformations [71,88], also obeying non-negative dissipation, is instead adapted for melting. Letting be a relaxation time constant,

The metastable melt fraction is . With and kinetic barriers, the following ordinary differential equation (ODE) is posited for melting but not solidification, akin to Refs. [71,88]:

The Heaviside function restricts the solution to . This differential equation must generally be solved numerically for since in (46) depends implicitly on . Dividing by and integrating,

Consider another analytical example to illustrate concepts and model features. When , the left side of (60) is assumed to vanish, whereby . Assume such conditions hold, meaning melting completes at time scales that are fast relative to the loading time. Continuing to assume forms and like those in (58) exist, and choosing

for example, (62) can be solved analytically as

If all terms except the first in vanish, then the local melt fraction for and increases with for . Solidification is possible (i.e., ) in that case if subsequently decreases. However, (61) with ensures non-negative dissipation only when , with . The case when is not ruled out. In calculations, non-negative dissipation can be enforced by a constraint . Solidification is thereby eliminated. A different ODE involving some sign changes to (61) is needed to model dissipative, metastable reverse transitions (i.e., solidification) [71,88].

3.6. Temperature

Substituting (46), (55), and (56) into (47), for and as invoked in Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6, gives

This nonlinear differential equation must generally be solved numerically for at each , in conjunction with (57) for , (60) for , and (49) for . If functional forms , , and exist, then at fixed y (65) gives

This equation likewise must be solved numerically. But if melting never occurs, , and, given function at y, (66) can be separated and integrated from as

The solution for in (67) presumes fracture occurs during the strain history, that is, . If , (67) holds with such that the integral embedded on the right involving vanishes. In the latter case, the analytical solution matches Ref. [8] in the absence of phase transformations.

4. Localization and Numerical Methods

4.1. Failure Modes

Three different shear failure criteria are defined:

- Shear banding. This is the localization definition of Molinari and Clifton [11,12,14] also used in Ref. [8]. With reference to the last of (44), failure by localization of shear strain occurs at material point B with and time when with increasing time for every point A with . If remains bounded, as , meaning shear stress vanishes at some time .

- Shear fracture. As in phase-field and continuum damage mechanics, shear fracture occurs when order parameter . In the present analysis, shear fracture will generally occur earliest at a point due to an initial defect. If in (53), then upon shear fracture. If , some (small) fraction of strength can be maintained, depending on whether shear banding or melting take place concurrently.

- Melting. Failure by melting occurs when order parameter . In the present analysis, melting will tend to occur first where temperature rise is largest, which correlates with high-strain regions triggered by initial defects (e.g., at point ). In (63), as if . But if , then some fraction of strength can be maintained depending on whether shear banding or shear fracture occur simultaneously.

Shear band failure, by definition, requires infinite strain at . Shear fracture and melting may or may not mandate infinite strain, depending on assumptions and parameters entering their governing equations. For example, is required for in (59) if , but not if . The model in (64) requires to approach infinite or for . If infinite strains are not required, fracture or melt failure can precede shear band failure. Depending on constitutive parameters for viscoplasticity, fracture, and melting, one or more failure modes may be impossible. Using a different theory, phase-field simulations [33] suggested a tendency for fracture to dominate shear band instability and failure in steel under dynamic torsion as applied strain rate increases.

First consider failure by shear banding. Equality of (44) is integrated to any time , with integration limits and , initial conditions , , and flow stress function (52). Then changing variables and dividing by , localization integrals are obtained by eliminating :

Dependence of and on Y independently of is permitted but is not written explicitly in (68). If localization occurs, , , and , where is finite:

As explained in Refs. [11,12], because is finite by definition, the integrals on the left, and thus the right, sides of (69) must all be bounded. This means localization occurs if and only if is integrable as . In Refs. [8,11,12], bounds on viscoplastic properties n, , and m were derived for which localization (i.e., shear band failure) is possible. These prior derivations, based on power-law viscoplasticity and analytical solutions for , did not consider shear fracture or melting. In the current setting, three possibilities emerge:

- Order parameters or evolve with as . No definite criteria for the possibility of localization are derived since , , and depend on in forms not known analytically.

- Either (or both of) or occurs at finite with or . In this case, fracture or melt failure precedes shear band failure; the latter never occurs since is finite.

- Both and attain fixed terminal values less than unity, or attain unit values with and , at finite . In this case, since and cease to evolve, they do not influence behavior of in (67) as , and and become nonzero constants. Thus, the original criterion for the possibility of failure applies (see derivations in Refs. [8,11,12]):most valid for . A Newtonian fluid is recovered for and , whereby (70) is violated. A slightly different analysis of non-hardening () materials [12] gives the localization criterion , also violated for any Newtonian fluid with . Hence, Newtonian viscosity of molten material must be omitted for failure, as done herein.

Next consider failure by fracture in the context of (59). If , shear fracture is possible at finite , necessarily preceding failure by shear banding or melting. However, as some strength is maintained when , residual material can still fail by melting, and possibly, shear banding. If , then . Failure by shear fracture, melting, and potential shear banding can take place concurrently as , but criterion (70) does not necessarily hold.

Lastly consider failure by melting in the context of heuristic model (64) with , , and . Since is non-negative by (49), . It is anticipated, but not proven, that melt failure occurs iff with , meaning complete melting at infinite strain if complete strength loss from fracture has not occurred already. In contrast, if at finite , then failure by melting, like failure by shear banding, does not arise, since plastic dissipation supplying a temperature rise ceases and becomes constant after shear fracture. If shear fracture does not occur at finite , then simultaneous shear banding, melt failure, and shear fracture are possible as , but (70) need not necessarily apply for shear banding.

4.2. Homogeneous Solutions

Henceforth, the analysis allows non-uniform and sets . All other physical properties are constant over . If is uniform, localization cannot occur: all points Y are indistinguishable so will share the same stress–strain–temperature history. Failure by shear fracture and melting remains possible. These could occur at finite or infinite . For homogeneous conditions, the entire slab would fracture or melt simultaneously. Average strain and defect parameter in the slab, whose average strain rate is since , with , are

Factor accounts for being the coordinate of the top of the slab after application of in Figure 1 and kinematic ansatz (29)–(31). If , then .

For homogeneous conditions, stress from (52) is, at fixed , , and ,

Order parameters and temperature are uniform, but functions , , and are not known analytically except in degenerate cases. Rather, (57), (61), and (66) comprise a set of three coupled ODEs to be integrated numerically, concurrently with (72), over the strain history :

Initial conditions prescribed for (73) are and .

4.3. Localization Calculations

Among all possible positions Y in the slab, localization ensues at the earliest possible , at point , for which the rightmost integral in (69) is a minimum [11,12]. Shear band failure, if occurring, commences at where is a minimum. This follows from the integrand of in (68) being non-negative and approaching zero only as at B. This threshold integral for localization at drops as decreases because and . For , the localization integral is very sensitive to the perturbation [8,11,12].

A shear band approaches a singular surface at across which displacement has a jump discontinuity as . It is assumed that and are continuous functions of Y except at singular point(s) at . In the shear band, from (68) and (69), at B as . At , since is continuous, at at least one location (that can in principle vary with t) must match . If this is time-independent, then identically. Stress exactly from (52) in that scenario, otherwise approximated by (55) at each , is given by (72) for . From (44), this value of is equally valid for the entire Y-domain for . Equations (73) are likewise valid to the same order of approximation for , with estimate in and [8,12,14], noting does not depend on . With these assumptions, affects the solution only through , and since is uniform over , it follows that , , and are suitably approximate functions only of at each point Y, for given loading and initial conditions , , and .

Computation of average localization strain proceeds as in Ref. [8]. Point is that for which . A numerical value of the right integral in (69) is found as . This integral converges (diverges) if localization is possible (impossible). If converged, the left of (69) is set to this value at all where and solved for at each . Critical strain is lastly found by integrating over Y in (71). Letting be any integrand in (69) and setting at to exclude singularities [11,12],

Numerical iteration is used to solve the first of (74), and numerical integration to solve the second of (74). The localization threshold integral on the right of (69), and thus and , are affected by transients in and ; how so depends on properties and is not obvious from inspection. As strain in the vicinity of the band accommodates more of the average, drops elsewhere for the same .

Previous calculations [8,11,12] did not seek to model degradation and failure within the adiabatic shear band. Therein, for , and the drop to zero stress upon localization was modeled abruptly (e.g., for ). A different approach is taken in the present work, similar to Refs. [27,28,47]. These studies likewise used plastic work-threshold-based damage models for adiabatic shear failure to capture gradual post-localization stress decay as witnessed in torsion experiments on iron and steels (e.g., [5,6,60]). Recall of (74) is the average strain in the slab that numerically excludes the contribution of the core of the fully formed shear band at : this core is infinitesimally wide but supports infinite shear strain . The latter’s contribution, from a discrete zone wherein shear fracture tends to concentrate, is represented by effective jump in shear displacement that can be formally derived using Gauss’s theorem [73,77]:

Post-localization shear displacement jump need not be calculated explicitly, but it can be using and from (74). The average strain in (75) is identified with in (72) to calculate stress for and . Physical consistency of this post-localization stress calculation requires that match the applied strain needed for ductile shear fracture to initiate under macroscopically homogeneous deformation, as in (72) of Section 4.2. Only the average stress decay is continuously depicted for the time history . Transients of local state variable fields , , , and are not modeled for the entire time history . However, the limit analysis does produce contours representing state variables at the final, failed material state as and .

In some demonstrative calculations of Section 5 and Section 6, ductile fracture is suppressed by setting threshold . In those calculations, is imposed and local fields remain static for any . For melt failure, this is consistent with neglecting viscosity of the liquid. For shear banding without resolution of ductile degradation, the predicted abrupt post-localization load drop is consistent with prior numerical implementations of the criterion [8,11,12].

Defect , with a distribution assigned as in Refs. [8,76], instigates localization at a single point at the midsection of the slab in Figure 1. Recall is the coordinate at after application of but preceding shear by . With identified in Figure 1, define having its coordinate origin at the midpoint of : . The initial defect distribution (i.e., yield strength perturbation) of intensity and width is prescribed in dimensionless form as [8,76]

In calculations, and y domains are discretized into dimensionless increments and . Taking is generally sufficient for independent of grid size. In agreement with Refs. [8,11,12], results of the analytical–numerical scheme are grid-size independent so long as the grid is fine enough to evaluate the localization integral (e.g., (74)) over the shape of initial defect. If the initial defect is not too sharp, no special provisions are needed to mitigate mesh dependency. This contrasts with traditional dynamic finite element (FE) simulations lacking any gradient or nonlocal regularization where mesh dependency is problematic in the strain-softening regime. Strain-gradient plasticity and phase-field fracture methods are commonly used elsewhere in such numerical settings, at least in part, to alleviate this numerical issue that does not emerge for the present method of analysis.

With numerical integration limited by machine precision and an infinite number of increments impossible, a large enough upper bound on is consistently used in (74) to enable respectable convergence of toward a constant value if enabled by properties (e.g., (70)) and loading conditions. Convergence quickens with fracture or melting: rapidly with as or for . In such cases, if failure by shear fracture or melting occurs, (74) is still used with singular point excluded from . Infinite strain remains possible at if material has null strength there.

Numerical results include contours of , , , and , where subscript denotes a quantity as and . Contours are restricted to dimensionless -space. They enable comparison of dimensionless widths of high-strain, high-temperature zones centered on singular bands at . Absolute zone widths scale linearly with if , , and are all constants. Minimum widths tend to zero as at fixed since gradient regularization, conduction, and inertia are not modeled. To account for regularizing physics and predict absolute shear band widths, more sophisticated numerical methods (e.g., finite difference [21] or FE [20,32]) are required.

5. Application to Steel

5.1. Properties and Parameters

Behavior of a high-strength, low C, Ni-Cr steel (i.e., a type of RHA steel) is analyzed. Mechanical properties follow from experimental studies of the 1970s–1990s [89,90,91,92,93], and for viscoplastic response, model calibrations to experimental data [8,94]. A typical composition [89,92] comprises Fe with 0.22 wt.% C, 1.06 wt.% Cr, 3.15 wt.% Ni, and other trace elements, rolled to a thickness of 0.5 in (12.7 mm). The dominant crystal structure at room temperature and atmospheric pressure is body centered cubic (BCC). As characterized in Ref. [92], the microstructure contains a mixture of martensite and bainite, heavily banded. Rolling can induce a slight anisotropy in plastic properties that is omitted in the current viscoplastic model and most others used for ballistic simulations of RHA [93,94]. The particular chemistry and processing history of the RHA tested in Ref. [6] are not listed in that reference, so the above characteristics are offered here as representative.

Material properties and parameters are listed in Table 1. Most properties, and most viscoplastic parameters, are repeated from Ref. [8] where original sources and calibrations can be found. Exceptions are static yield strength and rate sensitivity m. Values in Refs. [8,94] provided a best-fit to dynamic compression data optimized for strain rates of /s. Experiments modeled in the present study [6] consider a Ni-Cr steel of RHA type, but at lower average rates (e.g., /s) and for which a lower flow stress was observed than is predicted via past values GPa and . Iron and steels show increasing m for strain rates exceeding /s due to influences of phonon drag and relativistic mechanisms [17,70,80,95]. Logically, m is reduced to better represent rates /s; then, is adjusted to better match experimental torsion data [6] for .

Table 1.

Properties or model parameters for Ni-Cr steel (RHA), K.

In particular, data used to inform n, , and m primarily comprise uniaxial-stress tension experiments at lower rates [89] and uniaxial-stress compression experiments (i.e., Kolsky bar) at higher rates [93] over a range of initial temperatures. Test data and calibrations to Johnson–Cook [96] and power-law models are described in detail in Refs. [8,94]. Specifically, the reader is referred to Section 5.2, Table 1, and Figure 3a,b of Ref. [8] for assessment of the parameter calibrations for RHA (i.e., Ni-Cr steel). Implicit in consolidation of different stress states, parameters are assumed identical in tension, compression, and shear. Neither the standard Johnson–Cook model nor the power-law model, both based on standard flow theory, can discern differences in thermoplastic behaviors among tension, compression, and shear. Because torsion data across a wide range of rates and temperatures do not seem available for RHA, suitability of these assumptions for shear have not been verified. Data conversions among uniaxial tension/compression and shear are accomplished in terms of effective Von Mises stress and its conjugate plastic strain rate :

Recall is deviatoric Cauchy stress and is the traceless plastic velocity gradient referred to the locally relaxed intermediate configuration. For uniaxial stress extension or compression, is the magnitude of axial true stress and the axial true plastic strain rate. Correspondence to simple shear, including plastic work rate and recalling , is

For data or results conversions among different strain variables, time integration of (78) produces .

Like pure Fe, the , , and phases of this steel are BCC, HCP, and FCC. At and K, material is fully of phase. Near , transformation occurs at GPa, and near zero pressure, transformation occurs at K (see Ref. [8] and works cited therein). The present treatment is restricted to GPa, but shear-induced transformations, though not reported in known experiments on RHA, might be possible since they have been inferred for Fe [97]. Evidence of the transition within shear bands has been noted in some experiments [3,98] and models [99], but not others [6,92]. To keep the analysis and interpretation of results tractable, transitions are not modeled herein. If solid–solid transformations do occur, the analysis amounts to assigning each solid phase the same properties and ignoring dissipation from transformations. See Refs. [8,99] for models quantifying solid transformations in shear bands.

For localization calculations, follows from Ref. [8]. Effects of the initial defect width in (76) are explored in Section 5.2 by two choices and . In Refs. [8,11,12], ranges of perturbation intensity spanning were considered in parametric calculations on steels and Fe. Therein, decreased approximately linearly with . In Table 1, , intermediate among prior cited values, is suitable in Section 5.2 for consistently matching to average shear at localization from experiment [6] when . However, as also shown in Section 5.2, is not always a free parameter: , , , and are not all independent. As explained in Section 7, can be assigned uniquely by calculations if and are prescribed a priori. In (70), , so shear band failure is possible for this steel, at least in the absence of melting or fracture.

New parameters not repeated from Ref. [8] are those for the shear fracture model of Section 3.4 and the melting model of Section 3.5. For dynamic shear fracture, the simplest physically admissible choices entering (10), (53), and parameters consistent with experimental data [6] modeled in Section 5.2 are assumed. These include , , , , and as in example (59). The latter assumes isotropic ductile damage (e.g., spherical voids); detailed microscopy data would be needed to justify a nonzero value. The presently consulted data [6] do not allow independent calibration of and ; setting the former to zero is the simplest choice. The value MPa is taken verbatim from Ref. [27] on RHA steel, with the caveat that values ranging from 20 to 350 MPa have been used elsewhere for various structural steels [35,37]. Phase-field studies [31,32,35,37] consistently assign 10% of the plastic work to energy consumed by fracture, giving in Table 1. Cohesive energy is unknown a priori for the specific steel of present study; the value MPa in Table 1 is calibrated in Section 5.2 to the post-localization stress-strain data of Ref. [6]. Values ranging anywhere from 10 to 1600 MPa can be inferred from experimental and phase-field studies on other high-strength steels [4,31,32,35,37]. Induced porosity at fracture quantified by is difficult to quantify precisely for dynamic shear, but voids and cracks have been observed inside shear bands in experiments on steels [3,4,6]. A representative value of 0.05 from Ref. [71] on Fe and other steels is used, most valid for lower or tensile . With this choice and the value of in Table 1, tensile pressure that would induce rupture is GPa. The corresponding uniaxial tensile stress would be GPa. For reference, the static ultimate tensile strength of RHA ranges from 0.8 to 1.2 GPa [7,89], and spall strengths of Fe and steels range from 0.7 to 3.7 GPa [100].

For melting, , , and (63) is used. Metastable equilibrium, , is justified by suitability of shock-wave experiments that complete at timescales on the order of μs to determine melting curves of Fe [101,102]. Omission of is the usual assumption [56,57], satisfactory in the limit of sharp interfaces [55,103]. A nonzero value could be important for modeling nanoscale physics in a regularized phase-field theory [55], but calibration to nm scale data from experiments or atomic simulations is needed. The equilibrium melt temperature at ambient pressure, , is around 1800 K in Fe [104] and the present class of steels [93,94]. Unknown for the current Ni-Cr steel, values of and for Fe [104] are used as a substitute. The model can be considered reasonably accurate only for GPa since a near-linear dependence of melt start temperature on pressure is predicted by (63). At higher , experiments and atomic simulation data show highly nonlinear melt curves for Fe [101,102]. Such data also show mixed-phase regions where liquid and solid coexist at a given and . The width of the mixed-phase region, and dissipation from melting, are controlled by , for which precise values are unknown. Assumed in Table 1 are two choices for : one, for “fast melting” with GPa, one for “slow melting” with GPa. For the former, under purely thermal loading, at . For the latter, at . Redundant in the present setting, null values and are assigned. Admissible minimum and maximum values of are explored in calculations: and .

5.2. Numerical Results

Outcomes of calculations invoking methods of Section 4.2 and Section 4.3, with baseline properties of Ni-Cr steel in Table 1, are reported next. Results in Section 5.2 consider only null external pressure (i.e., ). Results are compared with dynamic torsion data of Ref. [6], specifically data from the experiment on specimen labeled “B6”. In that work [6], a torsional split Hopkinson (i.e., Kolsky) bar was used to determine average dynamic shear stress versus shear strain behavior, and local strains and strain rates were calculated by analyzing high-speed photographs taken in situ on portions of specimens marked beforehand with regularly spaced grids. Data for six specimens of 2 mm length were reported, but local strain distributions were only shown for B6 (hence the reason for first modeling that particular sample; B2 is also modeled later). Among the six samples, average wall thickness varied by %, mean strain rates varied up to a factor of around two, and localization was observed in four of the six experiments. Strains at localization onset were consistent for three of these four. As the material is not extremely rate sensitive, test-to-test variations are attributed to different initial defects that could possibly be linked to thickness perturbations [8,11,12]. Though possible, no attempts were made to customize shapes of initial strength defect distributions (e.g., , ) to better fit results of multiple tests.

Recall the shearing rate of the present framework is , where in the absence of dilatation, the true local strain rate is . The mean shearing rate for test B6 is taken as /s, depicting the average reported by the Hopkinson bar analysis [6]. The strain measure reported in Ref. [6] is interpreted here as true strain; it is not mathematically defined in that work. If, instead, it is interpreted as nominal strain (with rotation), then experimental values of and as quoted herein should be multiplied by . Threshold energy would be similarly reduced. The present true-strain interpretation is supported by consistency of the current model and parameters (i.e., Table 1) with the value of for RHA quoted in Ref. [27] and the Von Mises equivalent strain up to onset of localization for the same steel reported in Figure 3 of Ref. [28]

After localization begins, the mean shear strain rate remains reasonably constant according to the Hopkinson bar analysis, but image analysis suggests it could vary [6]. The former experimental result is used herein; the framework in Section 4 requires , and further omits inertial effects that would seem more prominent if the average, in addition to local, strain rate fluctuated strongly in time. Total average strain from experiment B6 is converted from a start time when the experimental load-time history provided by the Hopkinson bar begins. During the early part of the test (i.e., first s [6]), the stress response is overly compliant and highly oscillatory because the sample has neither loaded fully nor achieved equilibrium needed for a (nearly) uniform stress-strain state [105]. Thus, the oscillatory quasi-elastic offset “strain” contributes to the total calculated this way. For comparison of average stress-strain data with results of the rigid-viscoplastic framework of Section 3 and Section 4, this offset must equivalently be subtracted from the experimental record or added to the model reference datum, since prior to 20 μs, the bulk of the sample has not plastically yielded. Fine-scale oscillations are omitted [28].

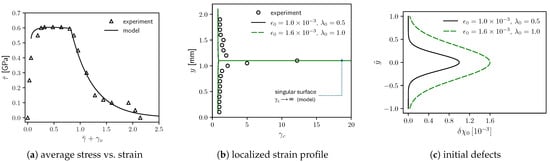

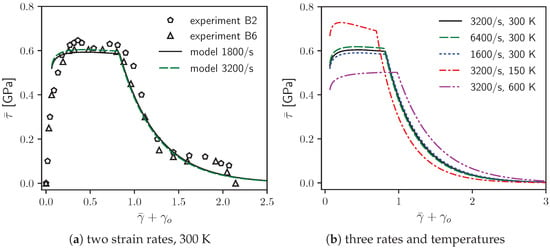

Average stress-strain behaviors are compared in Figure 2a. The model result is offset by as it necessarily excludes the oscillatory elastic ramp-up. Because of its rigid-viscoplasticity assumption (e.g., [1,12]), the model is overly stiff in the small-strain regime where the elastic contribution to strain is omitted by definition. The rapid load drop corresponding to the onset of localization appears at . Recall from Section 5.1 that the model, with prescribed , is able to accurately match the experimental stress-strain record with calibration of only two parameters: (i) initial yield strength for average stress up to localization and (ii) cohesive energy for the rate of post-localization stress decay. Shown in parametric calculations of Section 6, the stress drop becomes more abrupt as is reduced or as tensile pressure is increased. Resulting from the damage model of Section 3.4, shear stress decays exponentially, asymptotically approaching zero at large strain. A drop to absolute zero stress at finite strain is not captured. This limitation can be rectified by using a cut-off failure criterion , whereby flow resistance for . The final fracture strain inferred from data in Figure 2a can be matched by setting .

Figure 2.

Model results and experimental torsion data [6]: (a) average shear stress vs. average shear strain (strain in rigid-plastic model shifted by to compensate for oscillatory elastic ramp-up in experiments, not resolved) (b) localized strain distribution , specimen size mm (c) two initial defect profiles (). Experimental points sample continuous (a) or discrete (b) data from Ref. [6]. Nominal shear strain here in (b), with rotation, is defined as twice the numerical value of strain (e.g., ) in Figure 17 of Ref. [6].

Physically, a monotonic reduction in stress after damage onset is expected. However, data in Figure 2a show a horizontal plateau within a total strain domain between 1.5 and 2. Reasons for this are indefinite in Ref. [6]. A possible explanation is that damage initiates non-uniformly over the circumference of the specimen, then requires a finite time to propagate before the load drop is registered by the experimental apparatus [106]. The simple shear treatment of Section 3.1, in contrast, assumes damage and strain are independent of x and z coordinates and thus uniform around the circumference.

Localized strain distributions from model () and experiment (s) are compared in Figure 2b. Model results are shifted upward by mm so that locations of the centers of the shear bands coincide. This is permissible since -contours are nearly independent of for . Local strains are similarly uniform far from the core at mm, but the model does not capture the strain bulge surrounding the core of the band seen in the experiment. Post-localization strain within the modeled band is depicted by a finite displacement jump via (75) over a zero-width (i.e., singular) surface. In the experimental record, the band is of finite width, but cracks not evident in the data profile were seen around at least some of the perimeter [6]. Discrepancies can be attributed to missing regularization mechanism(s) in the model (e.g., no conduction, inertia, or gradient surface energies) and limits of experimental resolution emphasized in Ref. [6]. Differences between model and experiment are an inherent restriction of the method that cannot predict the true band width. Average shear strain is mainly accommodated by slip on the singular surface in Figure 2b rather than more broadly distributed as in the experiment. Adjustments to the model parameters and initial defect shape cannot resolve these fundamental differences.

The mean stress-strain behavior is the same when a less concentrated initial defect profile is prescribed, but of higher peak intensity, as depicted in Figure 2c. The value of must be tuned in this case to produce the same value of : a less sharp defect requires a larger magnitude to induce the same average localization strain.

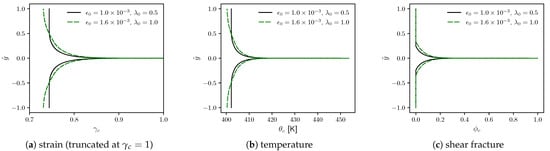

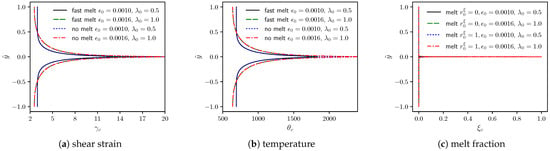

Effects of the two defect profiles on critical strain, temperature, and ductile fracture parameter distributions are further examined in Figure 3a–c. As anticipated, a more diffuse defect produces a wider strain, temperature, and damage distribution away from the infinite-strain band centered at than a narrower initial defect. Maximum temperature does not reach 500 K in either case. Damage-softening from fracture in the shear band reduces to such a low value that plastic working ceases to affect the by any pragmatically calculable amount as . Calculations verify temperature rise is insufficient to induce melting, even at the core of the shear band, recalling K. It also appears insufficient to induce phase transformation (not enabled in the framework of Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4) that occurs at K [8,92]. In the band center, .

Figure 3.

Model results for two initial defect profiles () vs. normalized spatial position : (a) post-localization strain (b) temperature (c) fracture order parameter

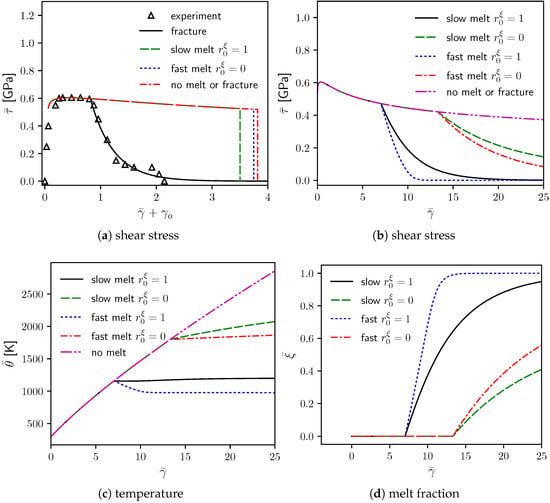

Calculations from the full model, fracture suppressed, and both fracture and melting suppressed are considered in Figure 4. In the full model, labeled “fracture” in Figure 4a, melting never occurs; results here are repeated with experimental data from Figure 2a. Cases in which fracture is deactivated but melting enabled are denoted “fast melt” and “slow melt” for respective small and large values of kinetic factor in Table 1. Different choices of and produce modest differences in the total strain at which localization ensues, beyond which the drop in average stress is abrupt per assumptions in Section 4.3. The largest critical localization strain is predicted when both softening mechanisms (i.e., fracture and melting) are suppressed. Figure 4b–d compare predictions of model renditions under homogeneous deformations (i.e., no initial defects: ). When stored energy of cold work fuels melting, then melting begins at . When it does not, melting begins at . Subsequently, melting occurs at a faster rate with respect to for the lower value of , as evidenced by the homogeneous melt fraction in Figure 4d. Shear stress decays with increasing in Figure 4b. Homogeneous temperature increases monotonically when melting is suppressed. Since melting consumes energy (), the rate of temperature increase is reduced during solid-to-liquid transformation. As seen in Figure 4c, for the case of fast melting fueled by energy from dissolution of dislocations, can even decrease.

Figure 4.

Model results with features activated or suppressed: (a) average shear stress vs. average shear strain and experimental torsion data [6]; (b–d) homogeneous solutions for average shear stress, temperature , and melt order parameter to extreme shear strain. Slow and fast melt correspond to respective large and small values of in Table 1; is fraction of stored energy of cold work released upon melting.

Contours of localized shear strain, temperature, and melt fraction are compared in Figure 5 for different renditions with fracture suppressed. These correspond to any post-localization time . In Figure 5a, local strain differs very little whether or not melting occurs. Differences are larger among the two different choices of . Similar trends are observed for local temperature in Figure 5b, noting that in the core of the shear band at , can exceed 2400 K. Accordingly, as seen in Figure 5c, complete melting is possible in the core. However, temperature and other driving forces (e.g., ) are not large enough outside the core to induce appreciable melting. Even partially liquified material is always confined to a very narrow region near the center of the band.

Figure 5.

Model results without fracture for two initial defect profiles () vs. normalized spatial position : (a,b) strain , temperature for or melt suppressed (c) melt parameter for .

Outcomes of calculations of Section 5.2 are summarized in Table 2, specifically the average stress computed at (i.e., immediately preceding the load drop associated with localization) and the critical average strain from (74) as that, by definition, excludes the contribution of (75). Since the steel is already thermal softening prior to any localization, lower always correlates with larger . A more diffuse defect with larger tends to delay localization. For the same initial defect profile, critical localization strain is reduced 80% by ductile shear fracture, but by no more than 12% by melting. For the considered ranges of material parameters and loading conditions in these calculations, melting never occurs when shear fracture is permitted.

Table 2.

Results summary for high-strength steel, , K, /s.

6. Parameter Variations

Parametric calculations next investigate influences of pressure and values of and entering the ductile fracture theory of Section 3.4. In all calculations of Section 6, the defect width per Table 1, but the intensity can depart from its nominal value of in Table 1. Quantities labeled by an asterisk correspond to nominal property values from Table 1 or to results obtained from calculations using such nominal property values. Pressures are always limited to GPa.

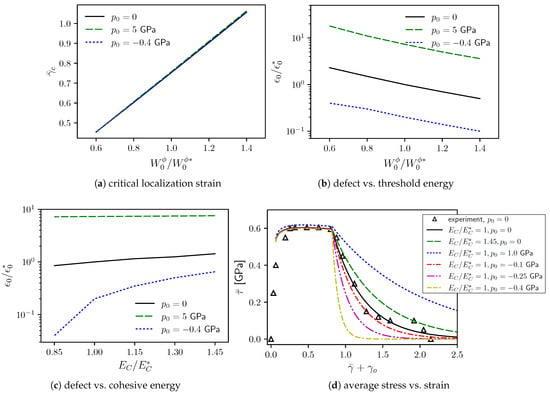

For calculations reported in Figure 6, the full model with fracture and possible melting is invoked, but melting never occurs in these predictions because fracture always takes place first. As in Section 5.2, upon shear fracture, stress drops too quickly to enable a large enough temperature rise from stress power to initiate melting, even in the center of the shear band.

Figure 6.

Effects of threshold fracture energy , cohesive energy , and pressure on (a) average strain for localization and (b,c) initial defect magnitude consistent with (d) average stress vs. strain at with experimental torsion data [6]. Baseline () from Table 1.

Effects of threshold energy on critical localization strain , at fixed , are shown in Figure 6a. Three values of applied pressure are considered: zero, 5 GPa compression, and 0.4 GPa tension. Recall from Section 5.1 that a tensile pressure approaching 0.5 GPa would induce instant cavitation and rupture, so larger tensile pressures not modeled here. The magnitude of each initial defect needed to achieve the corresponding is shown in Figure 6b. Critical average strain increases near linearly with but scantly increases (decreases) with compressive (tensile) pressure at fixed . Initial defect intensity in Figure 6b, in contrast, decreases significantly as tensile stress increases at fixed threshold . Furthermore, perturbation strength must decrease to enable larger threshold energy at fixed pressure. Results are physically viable: sensitivity to defects is greater in tension than compression, and threshold energy drops for sharper defects. Threshold energy and initial defects should not be prescribed independently because results show the two are intrinsically coupled, as discussed more in Section 7. The maximum local temperature in the core of the shear band, among all cases reported in Figure 6, arises for and GPa, with a post-localization value K. Maximum core temperature increases as , , and increase: threshold energy, cohesive energy, and compressive stress all delay final failure from damage-softening and fracture.

Effects of cohesive energy on defect intensity needed to produce a consistent value of , at fixed , are reported in Figure 6c. At any value of , a larger defect intensity is required in compression, a smaller defect strength in tension. Pressure sensitivity increases for lower values of . At fixed , a larger requires a more severe defect to engender the same , especially under tensile stress. For GPa, , whereas for and GPa. Cohesive energy and perturbation strength are nearly independent at high compressive pressure. Effects of and increased are compared with experiment [6] in Figure 6d, where is prescribed to give in all cases shown. Stress decay for accelerates under tensile pressure and decelerates when increases. Compressive pressure slows damage progression because of resistance to void expansion or crack opening.

Barring activation of some catastrophic defect or change in microstructure, adiabatic shear localization should follow, but not precede, instability in a viscoplastic solid [1,10,13,14,107,108]. Therefore, as the shear fracture model of Section 3.4 seeks to represent material degradation within a shear band, a pragmatic lower bound on the threshold plastic work , written as , corresponds to the plastic work accumulated up to the instability strain , that, in homogeneous simple shear, is determined from the condition under adiabatic conditions at a given initial temperature , loading rate , and pressure . This bound is implicit in prior modeling [28,47] that used a similar threshold energy density for the onset of damage softening. In the absence of melting, and with , the power-law flow model of (52) with analytical temperature solution of (67) () yields the following implicit solution for minimum localization strain and energy :

Parameters from Table 1, /s, and give and GPa. The former can be compared with Culver’s critical strain (e.g., [7]), where for calculated peak stress GPa and K.

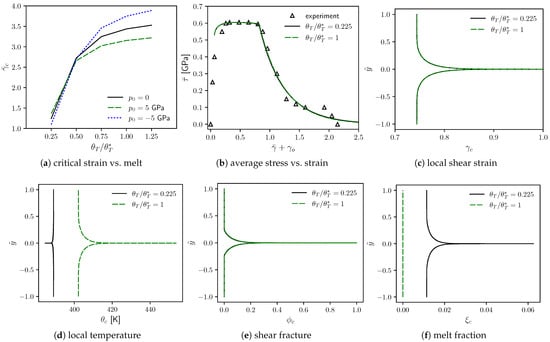

Effects of n, , m, and on and are shown in Figure 7a,b. Both and increase nearly linearly with increasing strain hardening exponent n. Both decrease nonlinearly with decreasing (more strongly negative) , corresponding to more thermal softening. While decreases modestly and nearly linearly with increasing rate sensitivity m, the minimum threshold energy is negligibly affected by m. The latter is likewise insensitive to initial static yield strength , but decreases nonlinearly with increasing . The latter decrease is a result of proportionally more plastic dissipation and temperature rise, leading to thermal softening that overtakes strain hardening at a lower applied strain.

Figure 7.

Effects of viscoplastic parameters for strain hardening , thermal softening , rate sensitivity , and yield strength on minimum localization (i.e., instability) strain and corresponding threshold energy . Baseline () from Table 1 produce and GPa.

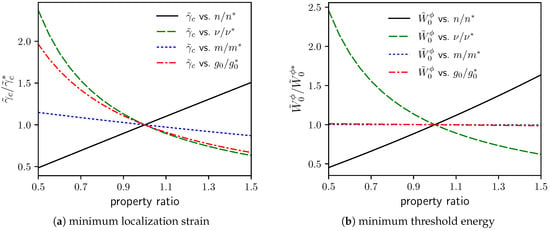

Implications of varying the equilibrium melt temperature are also investigated. Parametric calculations reported in Figure 8a study hypothetical cases when fracture is suppressed (i.e., ). Here, the defect profile is fixed at nominal values from Table 1: . Influences of compressive or tensile pressure GPa are considered, where large tensile pressure is admissible since fracture and cavitation are suppressed. Melt temperature ranges from 450 to 2250 K in Figure 8a. In all cases, increases with increasing at fixed : loss of shear strength is delayed as the requisite temperature rise for melting increases. In Figure 8a, decreases (increases) in tension (compression) at low , with the opposite trend at high . The effect of is greater at high . Opposing effects ensue: compression resists melting due to in (64), but increases strength via (51) and thus dissipative temperature rise that promotes melting.

Figure 8.

Model results for (a) effects of equilibrium melt temperature and pressure on critical localization strain with fracture suppressed (b) average stress vs. strain for reduced and realistic ( from Table 1) melt temperatures (fracture enabled) and experimental data [6] (c–f) post-localization strain , temperature , fracture parameter , melt parameter for reduced and realistic melt temperatures.

A theoretical case in which fracture and melting take place concurrently is now studied. In this case, K is low enough that melting begins in the core of the shear band even when the fracture model is enabled. Here, all parameters except and are nominal values from Table 1, including the set (GPa). The value is reduced from so that localization always ensues at . Average stress-strain behavior differs little in Figure 8b between the nominal case and reduced melting temperature. Contours of local shear strain and damage order parameter are also hardly affected by in Figure 8c,e. The material only partially melts, with nonzero limited to a narrow region near the core of the shear band in Figure 8f. Temperature in Figure 8d decreases slightly, relative to surrounding material, in the core where this transition occurs, as thermal energy is consumed by latent heat.