Abstract

Rankings drive consequential decisions in science, sports, medicine, and business. Conventional evaluation methods typically analyze rank concordance, dispersion, and extremeness in isolation, inviting biased inference when these properties co-move. We introduce the Concordance–Dispersion–Extremeness Framework (CDEF), a copula-based audit that treats dependence among these properties as the object of interest. The CDEF automatically detects forced versus non-forced ranking regimes, then screens dispersion mechanics via tests that distinguish independent multinomial structures from without-replacement structures and, for forced dependent data, compares Mallows structures against appropriate baselines. The framework estimates upper-tail agreement between raters by fitting pairwise Gumbel copulas to mid-rank pseudo-observations, summarizing tail co-movement alongside Kendall’s W and mutual information, then reports likelihood-based summaries and decision rules that distinguish genuine from phantom agreement. Applied to pre-season college football rankings, the CDEF reinterprets apparently high concordance by revealing heterogeneity in pairwise tail dependence and dispersion patterns that inflate agreement under univariate analyses. In simulation, traditional Kendall’s W fails to distinguish scenarios, whereas the CDEF clearly separates Phantom from Genuine and Clustered agreement settings, clarifying when agreement stems from shared tail dependence rather than stable consensus. Rather than claiming probabilities from a monolithic trivariate model, the CDEF provides a transparent, regime-aware diagnosis that improves reliability assessment, surfaces bias, and supports sound decisions in settings where rankings carry real stakes.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Problem of Ranking Analysis

Ranking analysis underpins consequential decisions across domains [1,2]. In academia, peer review allocates resources and recognizes contributions [3,4]. In sports, rankings drive championships and seedings [5,6]. In medicine, ordered risk stratification informs diagnosis and treatment [7,8]. In business, rankings shape performance evaluation and strategic decisions [9,10]. Examples of rank-based decision-making are therefore both pervasive and consequential.

Despite this ubiquity, methodological practice remains fragmented [11,12]. Analysts routinely summarize concordance (agreement among raters), dispersion (concentration of rank usage), and extremeness (prevalence of unusually high/low ranks) as if these were independent. In real systems, however, these properties co–move: patterns that boost agreement can also compress dispersion and alter the frequency of extremes and vice versa. Treating them in isolation risks mischaracterizing the integrity of the ranking process.

1.2. Limitations of Current Approaches

Classical measures—Kendall’s W for multi-rater concordance [13] and rank correlations in the Spearman family [14]—are informative but siloed. When multiple characteristics are considered, they are typically tested separately under implicit independence. This creates three well–known pitfalls.

First, summary indices ignore constraints among ranking properties: high agreement mechanically restricts allowable dispersion and alters the chance of extreme scores. Second, separate testing inflates false positives when dependence is present [15,16]. Third, independence-based reporting obscures whether “agreement” reflects genuine consensus or shared structure in how ranks are distributed and how extremes co-occur across raters.

Copula ideas have appeared around ranking problems, but prior uses generally address pairwise association or specialized tasks rather than a system-level diagnosis of how agreement, dispersion, and extremeness interact. To our knowledge, no widely adopted framework operationalizes these interactions to audit ranking reliability and surface dependence-driven artifacts.

1.3. The Copula Perspective

Copula theory separates marginal behavior from dependence [17], enabling flexible multivariate modeling with appropriate margins [18,19]. It has proven effective in finance [20,21], environmental extremes [22,23], and risk settings where tail co-movements matter [24,25]. For ranking systems, this perspective is compelling because the events with the greatest practical weight are often joint extremes (e.g., multiple raters pushing the same items to the top or bottom).

In the present work, copulas are not used to posit a monolithic trivariate latent model of “concordance–dispersion–extremeness.” Instead, we take a pragmatic, data-driven dependence view: estimate upper-tail association pairwise between raters using Gumbel copulas on mid-rank pseudo-observations, summarize tail dependence with both pairwise parameters and an aggregate scaled measure, and read them in concert with global concordance and information-theoretic screening.

1.4. Research Contribution and Novelty

We introduce the Concordance–Dispersion–Extremity Framework (CDEF), a pipeline that reinterprets ranking reliability through the lens of dependence. Its novelty lies not in proposing a new copula family but in providing a ranking-specific diagnostic that (i) identifies the appropriate dispersion structure through regime detection, (ii) quantifies tail-dependent agreement between raters, and (iii) integrates these elements to separate genuine consensus from dependence-induced artifacts:

- Regime and dispersion analysis. The CDEF first classifies the ranking regime as forced or non-forced, then selects an appropriate dispersion mechanism. For forced permutations with dependence, it fits a Mallows structure; for forced independence, it compares against the uniform permutation baseline. For non-forced rankings, a test distinguishes between independence (modeled using a multinomial allocation) and dependence, aligning inference with the data-generating structure.

- Tail dependence estimation. Using mid-rank pseudo-observations and the Kendall link , where is Kendall’s , the CDEF fits bivariate Gumbel copulas to every rater pair. These fits are aggregated into an extremeness summary that captures upper-tail co-movement [17,18,19,21,24,25].

- Screening and reporting. Global concordance (W), mutual information across representative pairs, and likelihood summaries provide complementary views of dependence. Decision rules then diagnose Genuine versus Phantom concordance—Phantom when high apparent concordance is primarily driven by tail dependence and shared dispersion patterns rather than stable consensus across raters.

This system-level reading of dependence addresses the core failure mode of traditional practice: high W by itself can be an echo of coordinated extremes or constrained rank usage. By design, the CDEF shows when apparent agreement dissolves once tail co-movement and dispersion mechanics are made explicit—delivering a practically actionable notion of Phantom concordance that classical summaries miss while remaining compatible with established copula methodology [20,21,22,23,24,25] and long-standing rank theory [13,14].

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Ranking Analysis Fundamentals

Ranking analysis concerns the statistical evaluation of ordered preferences or performance assessments across multiple entities [26,27]. Work in this area spans pairwise and multivariate formulations, from classic correlation measures to dependence models that handle complex rater systems.

Three characteristics organize the behavior of ranking systems. Concordance captures overall agreement among m raters ranking n entities, commonly summarized by Kendall’s W [13]:

where is the sum of ranks for entity i, and is the expected sum under random assignment.

Dispersion (or concentration) refers to how rank assignments are distributed across the available scale, independent of inter-rater agreement [26,28]. Depending on the underlying mechanism, dispersion may arise from independent draws, which can be modeled by a multinomial process; from allocation without replacement, which can be theoretically described using multivariate hypergeometric models [29]; or from structured permutation clustering around a consensus ranking, as captured by the Mallows distribution [30]. Because the choice of regime has direct inferential consequences, the CDEF treats it as a data-driven decision rather than fixing a single dispersion index a priori, and the hypergeometric structure is referenced conceptually rather than fitted in the current implementation.

Extremeness describes the prevalence and influence of unusually high or low ranks. Beyond marginal “extreme response styles” [31], the phenomena that most affect downstream decisions often involve co–occurring extremes across raters. This motivates a tail dependence view rooted in extreme value ideas [32,33,34,35,36] and copula modeling [24,25], where extremeness is operationalized through the strength of upper-tail association rather than only marginal outliers.

2.2. Traditional Ranking Evaluation Methods

2.2.1. Concordance Measures

Kendall’s W is the standard for multi-rater concordance [13]. Related agreement coefficients (e.g., Fleiss’s [37] and Krippendorff’s [38]) assess agreement beyond chance but can be challenging to interpret in rank permutation settings and may have non-Gaussian asymptotics that complicate inference in discrete data analysis [39].

2.2.2. Dispersion Analysis

Dispersion in ranking data can arise from fundamentally different stochastic mechanisms. When rank assignments are independent, category counts follow a multinomial law [40]:

where N is the total number of assigned ranks, is the observed count in category i (), and is the corresponding probability of assignment to category i under the null of independent allocation.

When assignments are dependent through sampling without replacement, a multivariate hypergeometric model would in principle provide an appropriate theoretical framework [29]:

where is the number of available items (or positions) in category i, is the number of items assigned to that category, is the total number of available positions, and is the total number of assignments. This structure reflects a dependent allocation process in which each assignment reduces the pool of remaining possibilities. Although this regime is theoretically important for distinguishing allocation mechanisms, it is not used in the present implementation, which operationalizes dispersion through multinomial and Mallows structures.

When rankings are forced permutations, dispersion is structured not by sampling frequencies but by proximity to a modal (or consensus) ranking. In this setting, the Mallows model [30] provides a principled baseline:

where denotes a particular ranking of n items, and is the modal or consensus ranking. The function measures the distance between and . A common choice is Kendall’s tau distance, defined as the number of pairwise discordances between the two orderings. The parameter is a concentration parameter: larger values correspond to rankings that are more tightly clustered around , while recovers a uniform distribution over all permutations. The term is the normalizing constant that ensures probabilities sum to one across all permutations:

where is the set of all permutations of n items. Closed-form expressions for exist when d is Kendall’s tau, making the Mallows model computationally tractable. The estimation of typically proceeds via the calculation of the maximum likelihood or method of moments using observed distances from . Misspecifying this structured dependence as multinomial or hypergeometric can lead to inflated or deflated dispersion estimates, masking the underlying mechanism and distorting subsequent inference.

2.2.3. Extremeness Detection

Extreme value theory provides limiting models for maxima and minima [32,33,34,35,36]. While marginal Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) families are informative, ranking systems often hinge on joint extremes—e.g., distinct raters simultaneously producing very high (or very low) ranks. This motivates tail-dependent multivariate models [24,25] in which extremeness is assessed through the probability of co-occurring extremes rather than only the marginal tail thickness.

2.3. Copula Theory in Dependence Modeling

2.3.1. Theoretical Foundations

Sklar’s theorem provides the theoretical foundation for copula-based modeling by decomposing any multivariate distribution into its marginal distributions and a copula that encodes their dependence [17,41,42]:

where is the joint cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the random vector , and is the marginal CDF of for . The function is a copula—a multivariate CDF with uniform margins—obtained by transforming each original variable through its marginal CDF, which maps the data into the unit hypercube while preserving their dependence structure.

This transformation cleanly separates marginal behavior from joint dependence, allowing the copula C to model the dependence structure independently of the marginal distributions . This property is particularly advantageous for ranking data, where the marginals are inherently discrete, but the dependence structure—especially in the tails—often carries the substantive signal [24,25].

To operationalize this for rankings, we map integer ranks to pseudo-observations on the unit interval . Each item receives a rank where r denotes the rank of an observation, and n is the total number of ranked items. A mid-rank transformation converts these to uniform pseudo-observations:

where U is the transformed value associated with rank r. The offset of centers the transformed values and avoids boundary effects at 0 and 1. For d raters, the vector lies in and forms the empirical basis for estimating the copula C. This transformation aligns with standard practice in empirical copula theory and order-statistic methods [43,44,45].

2.3.2. Copula Families for Ranking Applications

Different copula families encode different shapes of dependence. Elliptical copulas such as the Gaussian and Student-t copulas model symmetric dependence structures [46], while Archimedean copulas allow for flexible, often asymmetric tail behavior. Among the latter, the Gumbel copula is particularly well-suited to ranking applications in which upper-tail agreement—extremely high or concordant ranks—plays a dominant role in decision-making [18,19,21].

The d-dimensional Gumbel copula has the closed-form expression

where

- is the copula cumulative distribution function evaluated at the point .

- is the pseudo-observation corresponding to the i-th rater’s rank for a given item (obtained via the mid-rank transformation defined above).

- d is the number of raters.

- ln denotes the natural logarithm.

- is the Gumbel dependence parameter controlling the strength of upper-tail dependence, with corresponding to independence and to perfect upper-tail dependence.

In practice, system-level dependence can be characterized by fitting pairwise bivariate Gumbel copulas between rater pairs using the pseudo-observations [19]. The dependence parameter can be estimated through the relationship

where is Kendall’s rank correlation coefficient between the two raters. Aggregating pairwise estimates provides a summary of extremeness across the system.

To reflect both local (pairwise) and global (multi-rater) agreement, an auxiliary system-level index can be constructed by scaling by , where W is Kendall’s coefficient of concordance. This joint summary captures the extent to which overall concordance and tail dependence reinforce one another.

2.3.3. Recent Advances in Copula Applications

Copulas have proven effective in finance and risk [20,21], environmental extremes [22,23], and biostatistics [47,48]. High-dimensional extensions leverage vine copulas, hierarchical constructions that decompose multivariate dependence into a structured sequence of linked bivariate copulas, enabling flexible modeling in large dimensions [49,50], as well as factor copulas, which introduce latent variables to parsimoniously capture dependence structures in high-dimensional settings [51]. Meanwhile, goodness-of-fit procedures for copulas continue to mature [52,53,54]. Despite this breadth, direct applications to system-level ranking evaluation remain rare; most existing work focuses on pairwise rank association or theoretical properties of permutations [55] rather than the comprehensive diagnostics of ranking systems.

2.4. Comparison with Recent Multivariate Ranking and Copula-Based Methods

Table 1 positions the Concordance–Dispersion–Extremity Framework (CDEF) within the broader landscape of recent work on multivariate ranking and copula-based methods [55,56,57,58,59]. Whereas most existing approaches emphasize pairwise association or marginal dependence features, the CDEF targets the joint evaluation of concordance, dispersion, and extremeness in ranking systems. Its contribution is not the introduction of a new copula family but rather a ranking-specific diagnostic that places the dependence structure at the center of inference.

Table 1.

Comparison of CDEF with recent related methods.

2.5. Gaps in the Current Literature and the CDEF’s Unique Contribution

Although ranking analysis and copula methodology are both mature, we found no prior framework that jointly models concordance, dispersion mechanism, and tail-dependent extremeness for system-level evaluation. Traditional reliability metrics [39] often treat high inter-rater correlation as genuine consensus, even when shared dispersion patterns or tail behaviors drive much of the apparent agreement. Existing copula work in ranking contexts emphasizes estimation procedures [43], software and algorithms [60,61,62], asymptotics [44], and special domains [56,57,58,59] but not the overarching diagnostic question of whether “consensus” is genuine or dependence-induced.

The CDEF fills this gap with a theoretically grounded yet tractable pipeline: mid-rank pseudo-observations [43,44,45], pairwise Gumbel copulas for upper-tail dependence with the link [18,19,21], a data-driven dispersion regime choice (multinomial, without replacement, or Mallows) [26,29,30], and model comparison using likelihood summaries and dependence-aware diagnostics [24,25]. This combination provides practical tools for identifying Phantom reliability—apparent agreement explained by shared dependence—versus genuine consensus while remaining compatible with advances in high-dimensional dependence (vines [49,50]) and goodness-of-fit testing [52,53,54].

3. The Concordance–Dispersion–Extremeness Framework (CDEF)

3.1. Conceptual Foundation

The CDEF tackles a core limitation in ranking analysis: treating concordance, dispersion, and extremeness as if they were independent features. In many applied settings, dependence among these components is structural, not incidental [26,27]. Ignoring it can inflate evidence of “agreement” and misstate uncertainty [48].

The CDEF therefore (i) quantifies global agreement via Kendall’s W [13], (ii) diagnoses cross-rater information sharing and (in)dependence via mutual information and tests [15,16], and (iii) models the tail co-movement of raters using a copula layer that is sensitive to upper-tail clustering (Gumbel) [17,18,19,20,21]. The framework then chooses an appropriate dispersion model and baseline likelihood according to the ranking regime (forced vs. non-forced) and dependence diagnostics. Rather than reporting pseudo-conditional probabilities across heterogeneous scales, the CDEF summarizes the three components as normalized contributions that reveal where the dependence “mass” resides [18,21].

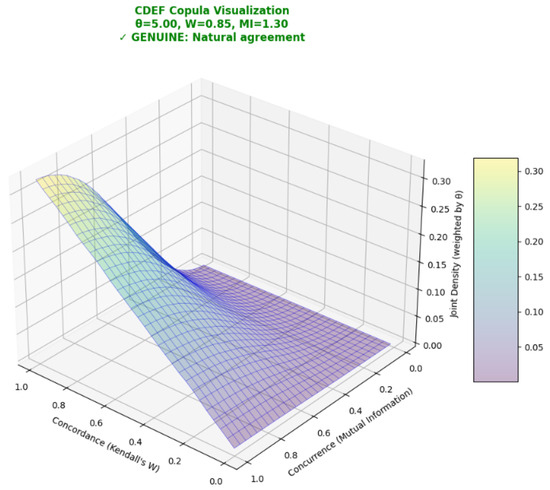

Figure 1 visualizes the CDEF joint surface for a Gumbel dependence regime with , evaluated at observed concordance and concurrence . Here denotes mutual information, a measure of concurrence that quantifies the reduction in uncertainty about one rater’s ranking given knowledge of another’s. Formally,

where X and Y denote the ranks assigned by two raters, is the set of ranked positions, is the joint probability mass function over rank pairs , and and are the corresponding marginal distributions. The logarithm is taken with respect to the natural base, so is expressed in natural units. Mutual information is zero when rankings are independent and grows as the joint distribution diverges from the product of marginals, capturing both linear and nonlinear association.

Figure 1.

The CDEF copula surface under a Gumbel model () showing joint density over concordance W and concurrence . Higher ridges indicate stronger upper-tail co-movement (greater dependence). The interactive code that produced this figure is available at https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/dustoff06/CDEF/cdef_analyzer?filepath=src/visualization/visualization.ipynb (accessed on 24 October 2025).

The surface exhibits its peak density at high concordance (W close to 1) and moderate concurrence ( around ), forming a ridge that slopes downward as concurrence decreases. This geometry reflects how upper-tail dependence in the Gumbel copula amplifies joint structure the most strongly when agreement is concentrated at the top of the ranking scale, rather than being uniform across all ranks. High W reflects strong alignment in the ordering of items, while captures the amount of shared information between raters’ assignments. The surface height corresponds to the joint copula density weighted by , the Gumbel dependence parameter. As increases, the ridge becomes sharper and more pronounced, indicating the stronger clustering of probability mass in the joint upper tail—that is, raters are more likely to agree on extreme (top-ranked) positions.

3.2. Operational Formulation

3.2.1. Data Layout and Regime Detection

Rankings are initially received in long format with columns Rater, Ratee, and Ranking. These are reshaped into a wide matrix (items × raters), and rows containing missing ranks are removed [26,27]. For each rater j, if the corresponding column is a strict permutation of (i.e., no ties), the dataset is labeled forced; otherwise, it is labeled non-forced.This classification determines both the dispersion baseline and the likelihood function used in subsequent inference.

3.2.2. Concordance

Global agreement among raters is captured by Kendall’s W [13,26], which quantifies the degree of concordance across rankings. This coefficient provides a normalized measure of agreement, taking values in the interval , where indicates complete randomness and perfect concordance. Formally, W is defined in Equation (1).

3.2.3. Concurrence Diagnostics: Mutual Information and

For each rater pair , we form a joint contingency of their rank columns and compute two dependence measures: mutual information (MI, in natural units) and Pearson , calculated in a test of independence. In the current implementation, we use an adaptive binned two-dimensional histogram for both forced and non-forced data with a capped square-root rule,

where is the number of items jointly ranked by raters j and k, and b is the number of bins along each axis.

Before hypothesis testing, we prune any all-zero rows and/or columns from the contingency table used for in order to avoid undefined expected counts. If pruning yields a table smaller than 2 × 2, we report and (no evidence of dependence). MI is still computed on a smoothed table for descriptive comparison.

To compute MI, we add a small Laplace constant to each cell to prevent , normalize the table to probabilities, and evaluate Equation (10) (units: nats). This yields for the pair .

For the test of independence, we use the unsmoothed counts after zero-row/column pruning, without continuity correction, following [15,16]. The resulting p-value for pair is denoted as .

Panel-level MI is summarized by the mean across all pairs (optionally reporting range or IQR). Global independence may be assessed by aggregating the pairwise p-values using Fisher’s method,

under the global null. For reproducibility, we fix the binning rule in Equation (11) and the smoothing level , and we report MI units (nats).

3.2.4. Extremeness via Copulas (Upper-Tail Co-Movement)

Ranks are converted to pseudo-uniforms by the empirical CDF, as previously explicated, which centers each order statistic in its probability interval and aligns with empirical copula practice and order-statistic theory [43,44,45]. For each rater pair, we fit a Gumbel copula capturing upper-tail dependence [17,18,19]. The Gumbel parameter relates to Kendall’s via Equation (9), and we also compute the average copula log-likelihood per observation as a fit diagnostic [18,21]. To reflect interaction between global concordance and tail dependence, we report

a scalar summary that rises when both pairwise tail co-movement and system-wide agreement are high [24,25].

3.2.5. Dispersion Baselines and Model Selection

The CDEF selects the appropriate dispersion or likelihood branch by combining the regime label (forced or non-forced) with the and mutual information diagnostics. For forced rankings with dependence detected, we fit a Mallows model in which the likelihood of a ranking is proportional to the exponential of the negative Kendall distance from the consensus ranking :

where is the Kendall distance, and is the Borda-based consensus—the ranking obtained by ordering items according to their mean rank across all raters [26]. We report both the approximate Mallows log-likelihood and the average distance to consensus. For forced rankings without dependence, the baseline is the uniform distribution over , with log-likelihood (using Stirling’s approximation for large N) [26,63].

For non-forced rankings without dependence, the baseline is a multinomial likelihood over the observed cells, with the maximum likelihood estimated via empirical frequencies [15,16]. For non-forced rankings with dependence, dispersion is treated nonparametrically: we characterize the dependence structure through the copula layer and report diagnostics, including pairwise estimates and the average copula log-likelihood. In cases where draws are highly concentrated, we note the theoretical connection to multivariate hypergeometric sampling [29], but no hypergeometric model is actually fitted in the current implementation.

3.2.6. Copula Selection and Tail Dependence

While several copula families can model dependence structures in multivariate distributions, the Gumbel copula was selected for this analysis based on its theoretical properties and alignment with the characteristics of extreme outcomes in competitive rankings. The Gumbel copula exhibits upper-tail dependence, capturing the probability that multiple raters jointly assign extreme high rankings to the same teams or athletes, which is particularly relevant in ranking analysis where the primary concern is the simultaneous occurrence of exceptional performance at the top of the leaderboard—such as the clustering of championship-level outcomes—driving competitive dynamics and ranking stability [18,19,22].

In contrast, the Clayton copula exhibits lower-tail dependence, focusing on joint occurrences of extreme low values, which is less pertinent since ranking systems place greater analytic weight on the behavior of top performers than on lower-ranked participants [19]. The Frank copula, exhibiting symmetric dependence without tail dependence in either extreme, fails to capture the asymmetric nature of competitive outcomes where joint extreme high performance differs fundamentally from lower-tail behavior [18]. The Student-t copula, while offering both upper- and lower-tail dependence, imposes symmetric tail behavior that inappropriately weights lower-tail events equally with upper-tail events, potentially obscuring the critical patterns of joint elite-level performance that this analysis aims to identify [46].

Furthermore, the Gumbel copula’s single parameter () provides a parsimonious model with clear interpretation—larger values indicate stronger upper-tail dependence—facilitating comparison across multiple ranking relationships [19,42]. Empirical validation through goodness-of-fit testing confirmed that this upper-tail dependence structure aligns with the observed patterns of extreme co-occurrence in the analyzed ranking datasets [52,53].

3.2.7. Reporting: Normalized Contributions

Because W, , and live on different scales or units, the CDEF reports

which sum to one and serve as a decomposition of where dependence is concentrated [18,21]. These are indices, not conditional probabilities.

We denote this normalized triple as the CDEF dependence index:

a point on the 2-simplex that summarizes the relative contributions of concordance, concurrence, and extremeness. For interpretability, we also report the concordance-weighted component as a scalar summary, with values near 0 indicating Phantom concordance (extremeness-dominated) and values near 1 indicating genuine consensus (concordance-dominated).

3.3. Estimation, Algorithms, and Numerical Safeguards

Regime Detection and Dispersion Model Selection

Given a cleaned pivoted input, we detect the dependence regime and deterministically select the dispersion model in a single step. Let denote the average pairwise Gumbel log-likelihood relative to the independence copula baseline (which has 0 average log-likelihood) [21], and let summarize upper-tail strength from the fitted pairwise Gumbel copulas [18]. We also compute W (rank concordance) and pairwise mutual information .

Decision boundaries are not arbitrary tuning parameters but are calibrated under null dependence via permutation or bootstrap procedures. Specifically, each threshold corresponds to a fixed quantile (e.g., the 95th percentile) of the statistic under an empirical null distribution generated by randomly permuting the input. This ties regime classification to a fixed Type I error rate, ensuring that Mallows or multinomial branches are only activated when dependence exceeds what is expected under independence. The dispersion branch is then chosen deterministically according to

Definitions.

- : Average pairwise Gumbel copula log-likelihood, centered relative to the independence copula (baseline ).

- : Scaled upper-tail dependence parameter from fitted pairwise Gumbel copulas, summarizing the strength of joint extreme behavior.

- W: Rank concordance statistic (e.g., Kendall-type) capturing the degree of ordering agreement across variables.

- : Pairwise mutual information, capturing nonlinear dependence between variables.

- : p-value from a chi-squared test on the joint contingency table.

Statistical calibration of thresholds.

- : Upper-tail dependence threshold, set as the qth percentile (e.g., ) of under the null of independence.

- : Concordance threshold, defined analogously for W under the null.

- : Mutual information threshold, defined as the qth percentile under permuted samples.

- : Significance level for rejecting independence in the test, typically .

Each threshold is therefore grounded in an empirical null distribution rather than subjective tuning. This effectively turns regime detection into a sequential hypothesis testing framework: if the observed statistic exceeds the expected value under independence, the corresponding branch is activated. The uniform branch serves as the null model, while Mallows or multinomial branches are triggered only when there is statistically meaningful dependence. This construction preserves determinism, enhances interpretability, and eliminates arbitrary decision rules. For numerical stability, we use small-cell smoothing in contingency tables, a Gumbel fallback to = 1 when the fit is ill-posed, and Stirling’s approximation for where needed [63].

3.4. Model Validation and Extensions

Goodness-of-fit for the copula layer is currently assessed indirectly via tests of independence and mutual information measures on each rater pair, providing evidence of the dependence structure to be modeled. Direct goodness-of-fit can also be evaluated using empirical copula methods and Cramér–von Mises (CvM)- and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS)-type tests, which compare the empirical copula to the fitted copula model [44,52,53,54]. Alternative copulas (e.g., t) and higher-dimensional constructions (vines) are natural extensions when lower-tail or asymmetric dependence is of interest or when many raters must be modeled jointly [46,49,50,51,64,65]. In longitudinal settings, time-varying (dynamic) copulas may capture evolving dependence [66]. Extreme value perspectives remain relevant for tail behavior [22,25,32,33,34,35,36].

4. Materials and Methods: Empirical Application

To demonstrate the CDEF’s practical utility, we analyze NCAA pre-season college football rankings from four polling organizations: the Associated Press (AP) Poll, Coaches Poll, Congrove Computer Rankings, and Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (ESPN) Power Index [67,68,69,70]. These sources form a multi-rater system in which human judgment and algorithmic models coexist. We also incorporate a simulation of exemplar scenarios to illustrate the utility of the CDEF approach. All analytical components are implemented through the RankDependencyAnalyzer class, which unifies regime detection, dispersion analysis, copula modeling, and concordance diagnostics in a reproducible workflow.

4.1. Data, Structure, and Preprocessing

4.1.1. Data Scope and Layout

The empirical application aggregates the four pre-season rankings for teams and raters (AP, Coaches, Congrove, and ESPN) [67,68,69,70]. Data are ingested in long format with columns Rater, Ratee (team identifier), and Ranking (rank as a positive integer). The data are then pivoted to wide format, with teams represented as rows and raters as columns. Rows containing any missing ranks are dropped, and the ranks are coerced to integer values in line with standard rank data practices [26,27]. This procedure yields a complete rank matrix, which serves as the empirical exemplar for subsequent analysis.

To evaluate the method’s sensitivity to different dependence structures, four simulated scenarios are constructed, each designed to stress a distinct facet of the joint ranking behavior. The Phantom (Extreme Bias) scenario imposes an alternating top–bottom ranking pattern shared across all raters, with only two random swaps per rater to avoid perfect identity, thereby inducing extremely high concordance and strong upper-tail co-movement. The Genuine (Natural Agreement) scenario begins with the identity permutation and introduces moderate noise through twelve random pair swaps per rater, producing high but not extreme agreement without engineered tail behavior. The Random (No Agreement) scenario assigns independent random permutations to each rater, creating a structure that approximates independence. Finally, the Clustered (Outlier) scenario forms a tight cluster among three raters (AP, Coaches, and ESPN) with eight swaps each while deliberately making one rater (Congrove) divergent through forty swaps, injecting a structured discordant element into the system. All simulations used a fixed seed for reproducibility.

4.1.2. Forced vs. Non-Forced Detection

For each rater j, we test whether the observed ranks are a permutation of without ties. If all columns pass this test, the dataset is labeled forced (strict permutations); otherwise it is non-forced (ties/duplicates allowed), consistent with treatments in the rank data literature [26,27].

4.2. Reproducibility

This section specifies the full data schema, analysis pipeline, model components, simulation design, and paper↔code mapping needed to exactly reproduce the empirical and exemplar results. The workflow follows established rank data and copula practice [17,18,19,21,26,27], with pseudo-observation construction aligned to empirical copula estimation and order statistics [43,44,45] and distributional choices for dispersion grounded in standard discrete models [29]. Tail dependence and risk interpretation conventions follow [18,25]. Where relevant, we note options for high-dimensional extensions via vines [49,50].

4.2.1. Data Schema and Ingestion

The analyzer reads a single Excel worksheet with columns Rater, Ratee, and Ranking. Rows are stored in long format, with one row per rater–ratee pair. The script validates the required columns and pivots the data to wide format, using ratees as rows and raters as columns. Complete-case rows are retained (dropna), and ranks are coerced to integers. A forced versus non-forced check evaluates whether each rater’s column is a permutation of with no ties. The empirical data are drawn from NCAA pre-season ranking sources [67,68,69,70].

4.2.2. End-to-End Analysis Pipeline

- Load and reshape. Excel→DataFrame; pivot to wide (ratees × raters).

- Ranking-type detection. Forced (strict permutations) vs. non-forced (ties allowed).

- Core concordance. Compute Kendall’s W from row-sum dispersion (closed form).

- Pairwise association. Compute pairwise Kendall’s and the full matrix.

- Copula dependence. Create pseudo-uniforms via per rater and fit pairwise Gumbel copulas; aggregate average log-likelihood across observations [43,44].

- Global tail parameter. Map and scale by for a concordance-aware extremeness index.

- Independence test and dispersion model. A test on binned pairs yields p; if , treat as dependent, and for forced rankings, fit a Mallows model; otherwise use the appropriate independence baseline (uniform permutations for forced, multinomial for non-forced) [26,29].

- Model selection summary. Report the selected distributional family and its (approximate) log-likelihood, alongside the copula average log-likelihood baseline.

- Relative importance decomposition. Report normalized weights over {Concordance W, Concurrence (MI), Extremeness }; these are interpretable as contribution weights, not probabilities.

4.2.3. Model Components and Estimation

Concordance. Kendall’s W is computed in closed form from row-sum dispersion [13].

Pairwise and Gumbel . For Gumbel copulas, with ; pairwise fits are performed on pseudo-uniforms from mid-rank transforms , consistent with empirical copula theory and order-statistic centering [18,19,43,44,45]. The average provides a global , which is then scaled by to reflect global concordance.

Dispersion family choice. The independence test on a 2D histogram of two raters’ ranks (square-root bin rule, lower bound 5) returns . For forced rankings with , a Mallows model with Kendall distance to the Borda consensus is fit (approximate MLE and log-likelihood); for forced independent, the uniform permutation baseline uses an exact or Stirling-approximate ; for non-forced independent, a multinomial log-likelihood is computed [26,29].

Mutual information (MI). MI is computed from the smoothed joint histogram of two raters’ ranks (additive constant to avoid ).

Diagnostics. Average copula log-likelihood, independence baseline (uniform copula), and the pairwise range provide goodness-of-fit context [52,53,54].

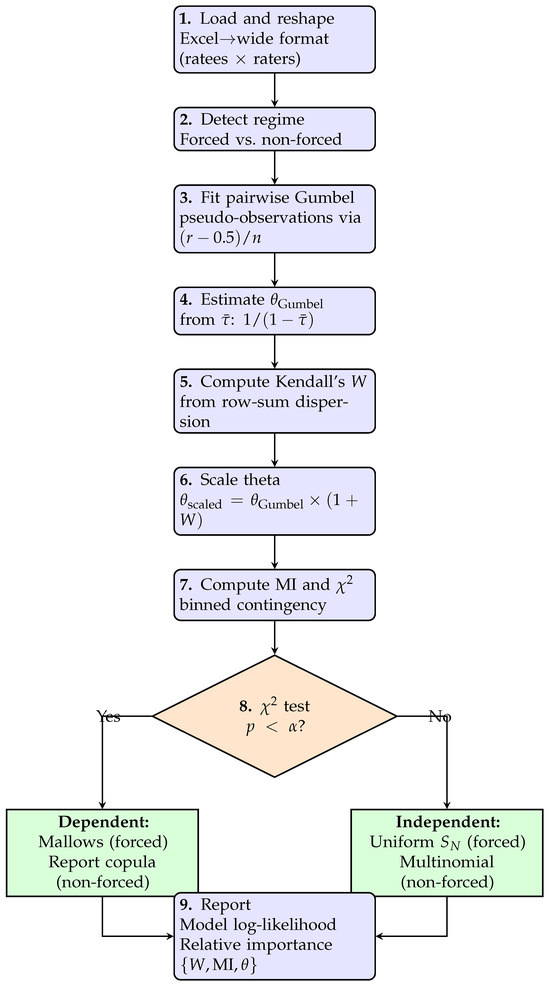

Figure 2 presents the overall flowchart of the analysis. This diagram summarizes the key stages of the end-to-end pipeline, beginning with data preparation and ranking-type detection, proceeding through concordance and dependence modeling, and concluding with model selection and interpretation. Each component in the flowchart corresponds to a specific statistical operation described in the methodology, providing a clear visual structure that mirrors the analytical sequence used in this study.

Figure 2.

CDEF workflow as implemented. Steps 1–7 compute statistics sequentially; step 8 tests independence and branches to regime-specific models; step 9 synthesizes results. For non-forced dependent rankings, framework relies on copula diagnostics rather than parametric dispersion models.

4.2.4. Simulation Scenarios (Exemplar Study)

We generate four stylized scenarios to stress-test interpretability under distinct dependence profiles—Phantom (Extreme Bias), Genuine (Natural Agreement), Random (No Agreement), and Clustered (Outlier)—using the same pipeline and fixed seed. Construction follows tail dependence logic [18,25]: (i) create_phantom_scenario induces a shared extreme pattern with tiny swaps (very high W and ), (ii) create_genuine_scenario applies moderate perturbations to a common baseline (high W, moderate ), (iii) create_random_scenario draws independent permutations (low W, low ), and (iv) create_clustered_scenario keeps three raters close and one divergent (heterogeneous ). Each scenario is persisted to long-format Excel via save_scenario_to_excel and analyzed by the same one-pass routine run_cdef_demonstration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exemplar simulations and interpretation: paper concepts to concrete code functions, files, and outputs. All simulations use the same pipeline and the mid-rank transform consistent with empirical copula practice [43,44,45].

4.2.5. Software, Determinism, and Environment

Code and Data Availability

All analysis code, exemplar simulation scripts, and reproduction notebooks are hosted at github.com/dustoff06/CDEF (accessed on 24 October 2025). The repository provides a complete Python package (cdef_analyzer) with both programmatic and command-line interfaces for CDEF analysis. Core components include the following: (i) RankDependencyAnalyzer, the main analysis engine implementing regime detection, concordance computation, pairwise Gumbel copula fitting, and model selection; (ii) exemplar scenario generators for Phantom, Genuine, Random, and Clustered ranking patterns (run_cdef_demonstration.py); (iii) interactive visualization tools for copula surface exploration (Figure 1); (iv) comprehensive unit tests validating numerical accuracy; and (v) a reproducibility guide with usage examples. Synthetic scenario outputs (e.g., scenario_phantom_extreme_bias.xlsx) are programmatically generated and saved alongside summary CSV reports (cdef_summary_fixed.csv). The empirical NCAA ranking input (long format with columns Rater, Ratee, Ranking) is provided in the repository with instructions on how to reconstruct it from public sources [67,68,69,70].

Software Usage

The package supports three interaction modes:

- Programmatic: RankDependencyAnalyzer.analyze_from_excel("data.xlsx").

- Command-line: cdef_analyzer –input rankings.xlsx –output report.json.

- Interactive: Jupyter notebooks for parameter exploration and visualization customization.

The analysis results include concordance metrics, extremeness parameters, model selection summaries, normalized indices, and interpretation labels (GENUINE/PHANTOM/CLUSTERED/RANDOM). The typical performance is as follows: <1 s for N = 136, m = 4 (NCAA example); ∼5 s for N = 500, m = 10; ∼45 s for N = 1000, m = 20 on commodity hardware. Computational complexity is , dominated by pairwise copula fitting. Interactive graphics are available via Binder (https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/dustoff06/CDEF/cdef_analyzer, accessed on 24 October 2025) to allow for experimentation without local installation. A Python API is available on GitHub (https://github.com/dustoff06/CDEF, accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Interpreter and OS. Experiments were run with Python 3.12 (package supports Python ≥ 3.12). The pipeline is OS-agnostic; example paths use Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) mounts for convenience (e.g., /mnt/c/Users/…). Docker containerization is available for isolated execution environments.

- Random seeds. All exemplars fix the numpy RNG seed prior to any random draws. The analyzer optionally accepts random_seed at initialization to enforce determinism end-to-end.

- Key libraries. Core dependencies are numpy, pandas, and scipy (Kendall’s , , entropy/MI), plus copulas for Gumbel fits; openpyxl/xlsxwriter are used for Excel I/O; matplotlib supports visualization. Full, pinned versions are listed in requirements.txt at the repository root.

- Artifacts and logs. Each scenario is exported as a long-format Excel file, analyzed once, and summarized; the script writes a CSV comparison table. Console output records: ranking type, selected distribution, W, , , , MI, copula average log-likelihood, independence baseline, relative importance weights, pairwise range, and the interpretation label. The results can be exported to JSON, CSV, or formatted text reports.

- Environment capture. For exact replication, a fresh virtual environment is created and installed from the repository’s requirements.txt.

- python -m venv .venv

- source .venv/bin/activate # Windows: .venv\Scripts\activate

- pip install -r requirements.txt

4.2.6. Diagnostics and Validation

Goodness-of-fit follows copula testing practice [52,53,54]. We report the pairwise spread, average copula log-likelihood, and an independence baseline (uniform copula). For forced dependent data, the Mallows fit (approximate log-likelihood) provides a dispersion model check [26]. For non-forced independent cases, the multinomial baseline is reported [29]. When dimensionality increases, vine constructions and factor copulas provide scalable alternatives [49,50,51] while preserving reproducibility.

4.2.7. From Paper to Code

The pipeline implements Sklar’s theorem for separating margins and dependence [17] with a Gumbel copula for upper-tail focus [18,19,21]. Pseudo-observations follow the empirical copula literature [43,44]; dispersion baselines and Mallows scoring follow standard rank data texts [26,27]. The exemplar generators instantiate edge cases that illuminate tail dependence effects central to risk and reliability arguments [25]. All steps are one-pass and scriptable, ensuring exact reproducibility across machines given identical inputs and seeds.

4.3. CDEF Components and Estimation

4.3.1. Concordance (Global Agreement)

We summarize global agreement via Kendall’s coefficient of concordance W (see Equation (1)) [13,26].

4.3.2. Concurrence (Information-Sharing)

Pairwise dependence in rater assignments is quantified using mutual information (MI) computed from the empirical contingency of two rank columns and a test for independence on the same table (finite-sample cells are smoothed by a small constant to avoid zeros) [15,16]. For the exemplar, a typical pair yields strong dependence (e.g., , ) and aggregate MI nats.

4.3.3. Extremeness (Upper-Tail Co-Movement)

We characterize tail co-movement using a Gumbel copula for each rater pair [17,18,19,20,21]. Gumbel copulas were chosen because their asymmetric structure captures upper-tail dependence, which aligns with ranking scenarios where agreement is the strongest among top-ranked items and disagreement grows toward the lower ranks. Ranks are converted to pseudo-observations (empirical CDF; see [43,44] for pseudo-observation theory). For a pair , we fit a bivariate Gumbel copula; its Kendall’s links to by , so [18]. We report the following:

- Pairwise for each rater pair (heterogeneity reveals clusters/outliers) [18,19].

- A scaled summary to reflect global concordance interacting with tail dependence (conceptually aligned with dependence modeling guidance in [24,25]).

- A dependence-aware average copula log-likelihood (per observation) computed from fitted pairwise densities [18,21].

In the exemplar, ; pairwise ranges from (weak) to (strong), with average copula log-likelihood per observation.

4.4. Model Selection for the Ranking Regime

Forced versus non-forced detection determines the modeling regime in the following fashion.

4.4.1. Forced Rankings

When the data are forced and exhibit dependence (significant /MI), we fit a Mallows model with Kendall distance to a consensus (Borda-based) [26]. We report an approximate log-likelihood score and the average distance to consensus. If independence were not rejected, the baseline is the uniform distribution on with log-likelihood (computed via Stirling when N is large), standard in permutation modeling [26,63]. In the exemplar, selection favors Mallows (dependent, forced) with log-likelihood .

4.4.2. Non-Forced Rankings

When ties or duplicate rankings are present and independence is not rejected, we use a multinomial baseline over the observed pairs, with maximum likelihood probabilities estimated via empirical frequencies [15,16]. When dependence is detected, the copula layer is used to characterize the dependence structure without imposing a fully specified discrete joint model. Although multivariate hypergeometric formulations provide a theoretical framework for modeling concentrated draws [29], no such model is currently fitted in the implementation; the copula layer serves as the primary diagnostic and inferential tool in these cases.

4.5. Composite Reporting: Indices, Not Conditional Probabilities

The CDEF reports a normalized triad of indices—concordance , concurrence (MI), and extremeness —as relative contributions (each divided by the sum ). These are not conditional probabilities (different units/scales); they serve as an interpretable decomposition of where the “signal” resides [18,21]. In the exemplar, the triad is , indicating that extremeness dominates the joint structure.

4.6. Exemplar Outputs and Diagnostics

We implement the following: (i) small-cell smoothing for contingency tables; (ii) copula density clipping and vectorized evaluation; (iii) Gumbel fallback to when a fit is ill-posed; and (iv) Stirling’s approximation for [63]. Near-independence runs (e.g., fully random permutations) can trigger harmless numerical warnings; when this occurs, the independence baseline (average copula log-likelihood ) provides a stable reference [21].

5. Results

5.1. NCAA Analysis Results

The traditional univariate analysis of the NCAA football ranking data suggests a highly coherent system. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was , indicating substantial to near-unanimous agreement across the four raters. A Pearson chi-square test on the (discrete) rank contingency yielded , rejecting independence by a wide margin. The analyzer detected the ranking type as forced (strict permutations), which is consistent with the polling protocol and motivates a Mallows family model for dispersion around a consensus ordering.

5.1.1. CDEF Analysis Results

The CDEF models the joint structure of concordance, concurrence, and extremeness. Pairwise Gumbel copulas are fitted to the pseudo-observations obtained from the empirical CDF ranks, capturing upper-tail dependence across raters. From these fits, the unscaled Gumbel parameter is estimated as , and the concordance-weighted index is . The average copula log-likelihood across all rater pairs is per observation, compared to the independence baseline of . Based on the dispersion and dependence diagnostics, the model selection procedure favors the Mallows branch for forced rankings with dependence, yielding an approximate log-likelihood of as a fit score.

The pairwise dependence is heterogeneous but consistently positive. Estimated pairwise Gumbel parameters for the rater pairs are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimated pairwise Gumbel parameters for rater pairs.

The corresponding Kendall’s matrix shows strong alignment among CBS/CFN/NYT and weaker (but still positive) alignment with Congrove (Table 4).

Table 4.

Upper triangular Kendall’s matrix for rater pairs.

To summarize joint contributions without conflating units, we report normalized indices (not probabilities) based on concordance (W), concurrence (mutual information, nats), and extremeness (). These weights indicate the relative dominance of each component in the observed dependence (Table 5).

Table 5.

Normalized dependence indices and corresponding metrics.

Extremeness (tail dependence) dominates the joint structure.

5.1.2. Comparative Interpretation: Revealing Phantom Concordance

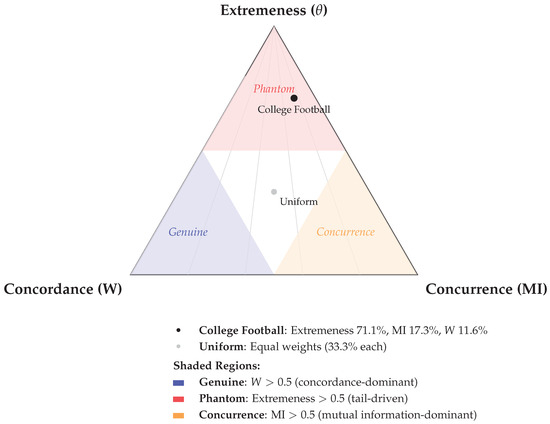

A W-only reading would conclude “strong consensus” (). The CDEF shows why this conclusion is incomplete. The fitted copulas deliver substantial likelihood gain over independence, but the dominance of the extremeness index (71.1% of the normalized triad) reveals that much of the apparent agreement is driven by shared tail behavior rather than uniform alignment over the full rank spectrum. The CBS/CFN/NYT cluster exhibits strong pairwise dependence (Gumbel –; –), whereas Congrove’s alignment is materially weaker (Gumbel –; –). This pattern is consistent with Phantom concordance: high global W coexisting with dependence concentrated in extremes and uneven pairwise structure. See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A ternary diagram of CDEF decomposition showing the relative importance of concordance (W), concurrence (MI), and extremeness (). Three regions partition the space: Genuine (concordance-dominant, ), Phantom (extremeness-driven, ), and concurrence (MI-dominant, ). College football rankings fall in the Phantom zone with 71.1% weight on extremeness, revealing that the high absolute masks tail-driven rather than uniform consensus.

5.1.3. Quantifying the Cost of Ignoring Dependencies

If one were to treat concordance, dispersion, and extremeness independently, the system would appear exceptionally reliable. Joint modeling tells a stricter story. The copula-based fit (average log-likelihood vs. under independence) confirms genuine dependence, but the normalized decomposition (concordance , concurrence , extremeness ) indicates that tail-driven co-movement is the dominant driver of alignment. In practical terms, univariate summaries overstate “agreement”—they absorb extremal co-movement into a single headline number. The CDEF separates these mechanisms, preventing overconfidence in ranking-based decisions when the agreement is disproportionately concentrated in the tails.

5.2. Simulation Study

5.2.1. Analysis Pipeline

Each scenario was converted to the original long format (Ratee, Rater, Ranking) and analyzed with the fixed RankDependencyAnalyzer. The analysis pipeline detected ranking type (forced vs. non-forced), fit pairwise Gumbel copulas on pseudo-observations derived from empirical CDF ranks, and computed concordance (W), Kendall’s matrix, mutual information (MI), and average copula log-likelihood per observation relative to an independence baseline. Model selection applied the Mallows model for forced rankings under dependence, reporting log-likelihood as an approximate fit score. Finally, normalized indices for concordance (W), concurrence (MI), and extremeness () were computed as relative importance weights; these are indices, not probabilities.

5.2.2. Results by Scenario

Table 6 summarizes the results across all four scenarios.

Table 6.

CDEF simulation summary across four scenarios.

- Phantom. Forced rankings with overwhelming tail-driven agreement yielded , , , and . The average copula log-likelihood was (independence baseline ). Pairwise Gumbel ranged from to . CDEF classification: Phantom (). Normalized indices: concordance , concurrence , extremeness .

- Genuine (Natural Agreement). High agreement without engineered extremes yielded , , , and . The average copula log-likelihood was (independence ). Pairwise Gumbel fell in a narrow band: –. CDEF label: Genuine (). Normalized indices: concordance , concurrence , extremeness .

- Random (No Agreement). In the Random scenario, near-independence is obtained by construction. Under these conditions, the run aborted with a numerical error during log-density evaluation, reflecting the inherent instability of copula likelihood estimation when dependence approaches zero. This is expected: as the system nears independence, the log-likelihood surface flattens and provides little information for parameter identification, particularly for tail-dependent families such as Gumbel. In such cases, the intended baseline interpretation is , , and , with pairwise centering near 0. We treat this as the independence reference, not as a model failure but as a signal that the CDEF has correctly encountered the lower bound of interpretable dependence.

- Clustered (Outlier). The three-rater cluster with one divergent rater produced , , , and . The average copula log-likelihood was (independence ). Pairwise Gumbel range: – (stronger within-cluster, weaker with the outlier). CDEF classification: Genuine (). Normalized indices: concordance , concurrence , extremeness .

5.2.3. Takeaways

A concordance-only reading would classify all three successful runs as showing strong agreement (, , and ). The CDEF clarifies the mechanism: in the Phantom case, extremeness accounts for of the normalized triad, revealing tail-driven co-movement masquerading as consensus, whereas in Genuine and Clustered, extremeness contributes and , respectively—indicating tail effects that complement rather than dominate substantive agreement. The average copula log-likelihoods ( for Phantom vs. and for Genuine and Clustered) confirm the stronger dependence structure in the Phantom case despite only marginally higher W. The Random scenario serves as the independence baseline. These results demonstrate that the CDEF successfully distinguishes Phantom from genuine consensus where traditional concordance measures conflate mechanistically distinct agreement patterns.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The CDEF contributes a principled framework for evaluating rankings by explicitly modeling dependencies among concordance, concurrence, and extremeness, rather than inferring “reliability” from any single index. While copulas and extreme value methods are established, their joint deployment for ranking evaluation shifts the theoretical lens from marginal agreement to dependence structure. The notion of Phantom concordance—high apparent agreement that is largely a byproduct of shared tail behavior or concentrated co-movement—emerges naturally when copula-based dependence is considered alongside concordance and information sharing. In the empirical application and simulations, the CDEF reveals hierarchical dependence: extremeness (upper-tail co-movement) persists more strongly than concordance or dispersion, and agreement is heterogeneous across rater pairs (e.g., strong CBS/CFN/NYT alignment vs. weaker ties with Congrove). This hierarchy suggests that “reliability” is multi-mechanistic: global concordance can be inflated by tail dependence, and genuine consensus should therefore be interpreted in light of the full dependence profile, not just Kendall’s W.

6.2. Methodological Advances

To our knowledge, the CDEF is the first framework to jointly model concordance, dispersion, and extremeness for ranking evaluation. While copula methods are well-established for multivariate dependence [17,18,19] and there is extensive literature on rank-based inference [13,26,27], existing ranking diagnostics treat concordance (e.g., Kendall’s W, Spearman’s ) and extremeness separately. Standard approaches compute concordance metrics without assessing whether agreement arises from uniform alignment or concentrated tail co-movement, leaving Phantom concordance undetected. The CDEF addresses this gap by explicitly modeling the dependence structure among ranking characteristics through copulas, enabling practitioners to distinguish mechanistically distinct sources of apparent agreement.

Methodologically, the CDEF integrates the following: (i) discrete, rank-based contingency inference (mutual information and tests on exact tables rather than binned counts); (ii) pairwise Gumbel copulas fit to pseudo-observations to capture upper-tail dependence; and (iii) model selection tailored to the observed ranking regime. For forced rankings (strict permutations), dependence triggers a Mallows family fit (with reported log-likelihood used as an approximate score), whereas independence defaults to a uniform permutation baseline (with a Stirling-safe computation of ). For non-forced settings, independence favors a multinomial baseline, while dependence is represented through the copula layer. Crucially, the framework reports normalized indices for concordance (W), concurrence (MI), and extremeness () to summarize joint contribution without implying spurious conditional probabilities. This design reduces arbitrary modeling choices, aligns distributional assumptions with the observed data structure, and prevents the overinterpretation of a single summary statistic.

6.3. Practical Applications

The CDEF’s capacity to distinguish genuine consensus from tail-driven co-movement has direct implications for peer review, sports analytics, and performance evaluation. In sports contexts, it can flag coordinated or structurally biased ranking behavior that eludes univariate concordance metrics. In business evaluation, the CDEF clarifies whether inter-rater alignment reflects robust assessment or systematic dispersion/extremeness patterns. By modeling tail behavior explicitly, the framework supports risk-sensitive contexts where extremes are disproportionately consequential. The simulation study underscores these points: a W-only analysis rated multiple scenarios as “strong agreement,” whereas the CDEF separated Phantom (extremeness-dominated) from Genuine and Clustered structures with heterogeneous pairwise dependence.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations suggest directions for extension. First, the current implementation prioritizes the Gumbel family (upper-tail dependence); lower-tail or asymmetric features may warrant alternative copulas or semiparametric fits. Second, while the normalized index provides a useful decomposition of dependence contributions, it is not a calibrated probability; future work could bootstrap scenario libraries to establish empirical thresholds for Phantom versus Genuine concordance and apply isotonic or Platt calibration to the extremeness component. Third, numerical stability near independence (as observed in the Random scenario) motivates robust density clipping and vectorized likelihood evaluation. Beyond pairwise modeling, higher-dimensional structures (e.g., vine copulas) could encode rater clusters, temporal stability, or expertise effects [49,50], and dynamic copula models could capture evolution in dependence over time [66]. Finally, nonparametric marginals and broader copula classes may further reduce modeling bias, at the cost of additional computation and the need for careful selection procedures. Despite these challenges, the CDEF furnishes a tractable and interpretable foundation that advances beyond traditional, univariate treatments of ranking reliability.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Key Contributions

This work introduced the Concordance–Dispersion–Extremeness Framework (CDEF), a copula-based approach that evaluates rankings by jointly modeling concordance (W), concurrence (mutual information, MI), and extremeness (upper-tail dependence via Gumbel ). The central contribution is conceptual and diagnostic: traditional univariate summaries (e.g., Kendall’s W) can overstate reliability when dependence across ranking characteristics goes unmodeled. In our NCAA application with four raters and N = 136 teams, a univariate reading suggests robust agreement (). The CDEF clarifies the mechanism: strong upper-tail dependence () and a dominance of the extremeness index in the normalized triad (extremeness of the total) indicate that the apparent consensus is driven disproportionately by shared tail behavior rather than consistent alignment across ranks.

The simulation study reinforces this distinction. The CDEF separates a Phantom scenario (very high W, extreme tail co-movement; ) from Genuine and Clustered scenarios where agreement is substantial but not dominated by extremes. Taken together, these results show that the credible assessment of ranking integrity requires modeling the dependence structure, not just marginal agreement—a perspective consistent with the copula literature [17,18,19,20,21] and with rank-based inference more broadly [13,26,27].

7.2. Implications for Practice

The CDEF distinguishes genuine consensus from artifacts of shared dispersion and extremeness patterns through quantifiable thresholds. Based on our simulation results (Table 6) and the ternary decomposition (Figure 3), we recommend the following diagnostic criteria:

- Flag for Phantom concordance when extremeness exceeds of the normalized triad, even if W appears high. In the college football application, extremeness accounted for despite , revealing tail-driven rather than uniform consensus. The simulation’s Phantom scenario showed extremeness at with = 30.7, whereas Genuine consensus exhibited only extremeness with = 4.2.

- Examine pairwise heterogeneity when Gumbel varies substantially across rater pairs. In our empirical case, the CBS/CFN/NYT cluster showed 3.6–5.6, while Congrove’s alignment was weaker ( 1.85–2.12), indicating a subgroup structure that global W obscures.

- Compare copula log-likelihood gains against independence. Small gains (<0.5 per observation) suggest weak dependence structure; large gains (>2.0) coupled with high extremeness indicate coordinated tail behavior requiring scrutiny.

These criteria apply directly to peer review (detecting synchronized use of extreme accept/reject scores), sports analytics (identifying structural ranking bias), and performance evaluation (distinguishing robust assessment from shared dispersion patterns). Modeling tail behavior is especially valuable in risk-sensitive contexts where extremes carry disproportionate weight [22,24,25,32,33].

7.3. Future Research Directions

Three extensions would address current limitations. First, the Random scenario abort highlights the need for robust numerical safeguards near independence: density clipping, vectorized likelihood evaluation, and adaptive switching to empirical copulas when parametric fits fail [43,44]. Second, lower-tail copulas (e.g., Clayton) or asymmetric families (e.g., BB1, BB7) could capture phenomena where disagreement concentrates at the bottom of rankings rather than the top—relevant for identifying systematic undervaluation in hiring or grant review [18,19]. Third, vine copulas could decompose observed heterogeneity (e.g., the CBS/CFN/NYT cluster vs. Congrove) into explicit subgroup structures, enabling the detection of coordinated behavior within reviewer coalitions or regional biases in sports rankings [49,50,64].

7.4. Final Remarks

By embedding dependence modeling into ranking analysis, the CDEF advances beyond univariate reliability measures and offers a sharper lens on how consensus and bias actually arise. As rankings continue to shape consequential decisions across science, sports, and management [3,4,9,10,11], methods that account for concordance, concurrence, and extremeness together will be essential for robust, transparent, and trustworthy inference.

7.5. Generative Artificial Intelligence Disclosure

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4.5 in order to edit prose and format the paper. The authors used Claude.ai for programming support in Python. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.; methodology, L.F.; software, L.F. and A.S.; validation, R.S.; formal analysis, L.F. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F., A.S., A.T. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, L.F., A.S., A.T. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The NCAA football ranking data used in this study are publicly available from the respective polling organizations. Data are also available at https://github.com/dustoff06/CDEF (accessed 22 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arrow, K.J. Social Choice and Individual Values, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1963; ISBN 978-0-300-01364-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Collective Choice and Social Welfare; Holden-Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1970; ISBN 978-0-8162-2158-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann, L. Scientific peer review. Annu. Rev. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 197–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, M. How Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic Judgment; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engist, O.; Merkus, E.; Schafmeister, F. The effect of seeding on tournament outcomes. J. Sports Econ. 2021, 22, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csató, L. Tournament design: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 318, 800–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems. Npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawazoe, Y.; Ohe, K. A clinical decision support system. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.C.; O’Kane, P.; Mazumdar, B.; McCracken, M. Performance management: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scullen, S.E.; Bergey, P.K.; Aiman-Smith, L. Forced distribution rating systems and the improvement of workforce potential: A baseline simulation. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Saberi, M.; Chang, E. Analysing academic paper ranking algorithms using test data and benchmarks: An investigation. Scientometrics 2022, 127, 4045–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.; Friedman, L.; Sinuany-Stern, Z. Review of ranking methods in the data envelopment analysis context. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 140, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Y.; Tamhane, A.C. Multiple Comparison Procedures; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-0-471-82222-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, P.H.; Young, S.S. Resampling-Based Multiple Testing: Examples and Methods for p-Value Adjustment; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-471-55761-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sklar, A. Fonctions de répartition à n dimensions et leurs marges. Publ. Inst. Stat. Univ. Paris 1959, 8, 229–231. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, H. Dependence Modeling with Copulas; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4665-8322-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, R.B. An Introduction to Copulas, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-28678-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, U.; Luciano, E.; Vecchiato, W. Copula Methods in Finance; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-470-86344-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.J. A review of copula models for economic time series. J. Multivar. Anal. 2012, 110, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, G.; De Michele, C.; Kottegoda, N.T.; Rosso, R. Extremes in Nature: An Approach Using Copulas; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4020-4415-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Bárdossy, A.; Habib, E. Conditional simulation of remotely sensed rainfall data using a non-Gaussian v-transformed copula. Adv. Water Resour. 2010, 33, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrechts, P.; McNeil, A.; Straumann, D. Correlation and dependence in risk management: Properties and pitfalls. In Risk Management: Value at Risk and Beyond; Dempster, M.A.H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 176–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, A.J.; Frey, R.; Embrechts, P. Quantitative Risk Management: Concepts, Techniques and Tools, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-691-16627-8. [Google Scholar]

- Marden, J.I. Analyzing and Modeling Rank Data; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 978-0-412-99521-2. [Google Scholar]

- Critchlow, D.E. Metric Methods for Analyzing Partially Ranked Data; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985; ISBN 978-0-387-96137-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastle, W.J.; Wierman, M.J. Consensus and dissention: A measure of ordinal dispersion. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2007, 45, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L.; Kotz, S.; Balakrishnan, N. Discrete Multivariate Distributions; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-471-12844-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mallows, C.L. Non-null ranking models. I. Biometrika 1957, 44, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, E.A. Measuring extreme response style. Public Opin. Q. 1992, 56, 328–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S. An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values; Springer: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-1-85233-459-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, L.; Ferreira, A. Extreme Value Theory: An Introduction; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-23946-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A.; Tippett, L.H.C. Limiting forms of the frequency distribution of the largest or smallest member of a sample. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1928, 24, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, R.D.; Thomas, M. Statistical Analysis of Extreme Values: With Applications to Insurance, Finance, Hydrology and Other Fields, 3rd ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2007; ISBN 978-3-7643-7230-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirlant, J.; Goegebeur, Y.; Segers, J.; Teugels, J. Statistics of Extremes: Theory and Applications; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-471-97647-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K.L. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2008, 61, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchlow, D.E.; Fligner, M.A.; Verducci, J.S. Probability models on rankings. J. Math. Psychol. 1991, 35, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; MacKay, J. The joy of copulas: Bivariate distributions with uniform marginals. Am. Stat. 1986, 40, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, F.; Sempi, C. Principles of Copula Theory; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4398-8444-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; Ghoudi, K.; Rivest, L.P. A semiparametric estimation procedure of dependence parameters in multivariate families of distributions. Biometrika 1995, 82, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, J. Asymptotics of empirical copula processes under non-restrictive smoothness assumptions. Bernoulli 2012, 18, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.C.; Balakrishnan, N.; Nagaraja, H.N. A First Course in Order Statistics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-471-57321-3. [Google Scholar]

- Demarta, S.; McNeil, A.J. The t copula and related copulas. Int. Stat. Rev. 2005, 73, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emura, T.; Chen, Y.H. Gene selection for survival data under dependent censoring: A copula-based approach. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2016, 25, 2840–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emura, T.; Sofeu, C.L.; Rondeau, V. Conditional copula models for correlated survival endpoints: Individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2021, 30, 2634–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, K.; Czado, C.; Frigessi, A.; Bakken, H. Pair-copula constructions of multiple dependence. Insur. Math. Econ. 2009, 44, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czado, C. Analyzing Dependent Data with Vine Copulas: A Practical Guide with R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-13784-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.H.; Patton, A.J. Modeling dependence in high dimensions with factor copulas. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2017, 35, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermanian, J.D. Goodness-of-fit tests for copulas. J. Multivar. Anal. 2005, 95, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genest, C.; Rémillard, B.; Beaudoin, D. Goodness-of-fit tests for copulas: A review and a power study. Insur. Math. Econ. 2009, 44, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojadinovic, I.; Yan, J. Goodness-of-fit test for multiparameter copulas based on multiplier central limit theorems. Stat. Comput. 2011, 21, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grübel, R. Ranks, copulas, and permutons: Three equivalent ways to look at random permutations. Metrika 2024, 87, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, J.; Oualkacha, K. A copula-based set-variant association test for bivariate continuous, binary or mixed phenotypes. Int. J. Biostat. 2023, 19, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, D.; Gardini, A.; Belloni, P. Variable selection in bivariate survival models through copulas. In Book of Short Papers CLADAG 2023; Visentin, F., Simonacci, V., Eds.; Pearson: Milano, Italy, 2023; pp. 481–484. Available online: https://repository.essex.ac.uk/36703/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Akpo, T.G.; Rivest, L.P. Hierarchical copula models with D-vines: Selecting and aggregating predictive cluster-specific cumulative distribution functions for multivariate mixed outcomes. Can. J. Stat. 2025, 53, e11830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Hohberger, J. Addressing endogeneity without instrumental variables: An evaluation of the Gaussian copula approach for management research. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 1460–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojadinovic, I.; Yan, J. Modeling multivariate distributions with continuous margins using the copula R package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofert, M.; Kojadinovic, I.; Mächler, M.; Yan, J. Elements of Copula Modeling with R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-89635-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, J.F.; Scherer, M. Simulating Copulas: Stochastic Models, Sampling Algorithms, and Applications; World Scientific: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84816-874-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]