Abstract

This paper presents a novel and computationally efficient numerical method for solving systems of fractional-order differential equations using orthogonal hybrid functions (HFs). The proposed HFs are constructed by combining piecewise constant orthogonal sample-and-hold functions with piecewise linear orthogonal right-handed triangular functions, resulting in a flexible and accurate approximation basis. A central innovation of the method is the derivation of generalized one-shot operational matrices that approximate the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral, enabling direct integration of differential operators of arbitrary order. These matrices act as unified integrators for both integer and non-integer orders, enhancing the method’s applicability and scalability. A rigorous convergence analysis is provided, establishing theoretical guarantees for the accuracy of the numerical solution. The effectiveness and robustness of the approach are demonstrated through several benchmark problems, including fractional-order models related to smoking dynamics, lung cancer progression, and Hepatitis B infection. Comparative results highlight the method’s superior performance in terms of accuracy, numerical stability, and computational efficiency when applied to complex, nonlinear, and high-dimensional fractional-order systems.

Keywords:

orthogonal hybrid functions; sample-and-hold functions; triangular orthogonal functions; generalized one-shot operational matrices; system of fractional-order differential equations MSC:

26A33; 42C05; 93C15; 74H15

1. Introduction

Fractional calculus extends the conventional concepts of differentiation and integration to arbitrary (non-integer or complex) orders, offering a powerful framework for modeling memory-dependent and hereditary phenomena in natural and engineered systems [1,2,3]. Although its mathematical foundation dates back more than three centuries, fractional calculus has only recently gained prominence as a practical modeling tool across a wide spectrum of disciplines, including rheology, biomedicine, chemical engineering, viscoelasticity, and geophysics [4,5,6,7]. Its flexibility in capturing anomalous behaviors and long-range temporal correlations—features often missed by classical models—has established it as a cornerstone in contemporary applied mathematics [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Despite its advantages, the analytical solution of fractional differential equations (FDEs) is notoriously challenging due to the nonlocal nature of fractional operators. While some analytical approaches, such as perturbation methods and transform-based techniques, have been developed [16], they often fall short when applied to nonlinear or complex systems. Consequently, the pursuit of robust numerical methods has become central to advancing the applicability of fractional models. Techniques like the Adomian Decomposition Method [17], variational iteration method [18,19], and homotopy-based schemes [20], along with numerical schemes such as those by [21,22], have made notable contributions by approximating solutions with acceptable accuracy.

In recent years, various polynomial- and basis-function-based methods have emerged as promising tools for the numerical simulation of FDEs. These methods convert the original system into an algebraic structure, significantly reducing computational complexity. Among these, approaches based on Bernstein polynomials, Legendre collocation, Haar wavelets, and conformable fractional derivatives have demonstrated considerable success in terms of both accuracy and efficiency. For instance, ref. [23] applied Bernstein operational matrices to a fractional chemical kinetics model; ref. [24] employed the Adomian Decomposition Method for systems with deviated arguments; and [25] proposed a modified variational iteration framework using conformable derivatives. Other notable developments include Haar-based collocation [26], differential transform methods [27], and hybrid polynomial collocation strategies [28] for handling singularities in time-fractional diffusion models. Several studies have also addressed multi-order systems, fuzzy fractional modeling, and matrix-based fractional systems using tools like Laplace transforms, Kronecker products, and fuzzy logic extensions. These contributions reflect an ongoing trend toward generalizing and optimizing numerical schemes for greater stability, precision, and applicability. For example, ref. [29] formulated operational matrix strategies tailored to multi-physics applications, while ref. [30] incorporated imprecise information using Grünwald–Letnikov derivatives in fuzzy environments. Ref. [31] demonstrated matrix-based exact solutions using Caputo definitions, and ref. [32] leveraged Müntz polynomial expansions to handle complex multi-term FODEs and fractional PDEs.

Nevertheless, fractional models continue to present significant computational demands, particularly in biological systems, reaction–diffusion transport, and control dynamics, where the governing equations are highly nonlinear and multi-scale. As no single method can universally address all classes of FDEs, the development of adaptable and efficient numerical techniques remains an active area of research. Motivated by these challenges, this study proposes a numerical framework for solving a system of fractional-order ordinary differential equations of the general form:

Here is the unknown function, can be linear or nonlinear and the fractional derivative, and , is the Caputo fractional-order derivative

where is the Riemann–Liouville fractional-order integral, .

Our numerical technique is entirely based on the new orthogonal hybrid functions (HF) formed by combining the piecewise constant orthogonal sample-and-hold functions and the piecewise linear orthogonal right-handed triangular functions [33]. The new orthogonal hybrid functions were fruitfully employed for analysis and identification of time-invariant, time-varying delay and delay-free systems [33] and network analysis [34] (Sarkar et al. (2014)). In [33,35], linear ordinary differential equations up to the third order were only solved using orthogonal HFs, but we anticipate that HFs are sufficiently capable of being utilized to solve nonlinear ordinary differential equations, integral equations, integro-differential equations, partial differential equations, stochastic differential equations, etc. Since the integer-order calculus is a special case of the fractional calculus and orthogonal HFs possess possible applications in the classical calculus, i.e., integer-order calculus, we trust that orthogonal HFs may find useful applications even in fractional calculus. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to use orthogonal HFs to solve a complex system of nonlinear fractional-order differential equations. The remaining part of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces orthogonal HFs. The generalized one-shot operational matrices, which are the basis of our numerical method, approximating the Riemann–Liouville fractional-order integral in the orthogonal HF domain, are derived in Section 3. The numerical method based on the generalized one-shot operational matrices is developed in Section 4. Section 4 proves theoretically that the proposed numerical method converges the approximate solution of the system of nonlinear fractional-order differential equations to its actual solution. The proposed numerical method is tested in Section 6. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Hybrid Functions (HF)

Let us define the component of a set of orthogonal hybrid functions containing component functions in the semi-open interval as [33]

where and are constants defined as and , is the sample-and-hold function (SHF) defined as (Deb et al. [33])

and is the right-handed triangular function (TF) defined as [35]

Consider a time function, , of Lebesgue measure defined on the interval . Let us take equidistant nodes in the given interval with the constant step size as , .

The function can be expressed in terms of orthogonal HFs as follows:

where

, , , , .

The first-order integral of can be approximated on in the orthogonal HF domain as [20]

where

, , , , .

The complementary operational matrices, , , , and , are acting as a first-order integrator in the orthogonal HF domain. The orthogonal and operational properties of HFs are given in Appendix A.

3. Generalized One-Shot Operational Matrices for the Fractional-Order Integral of

In this section, we shall derive an HF estimate for the Riemann–Liouville integral of arbitrary order ( can be an integer or a non-integer (real number)) of via the generalized one-shot operational matrices.

Let us recall the definition of the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of order of .

Equation (8) can be written as

Substituting the HF estimate of ,

where signifies transpose.

Utilization of the orthogonal HFs for approximating in (10) transforms the fractional integration of to the fractional integration of the SHF set and the TF set.

Performing fractional integration on the first member of the SHF set ,

Evaluating (11) at provides the samples of at , , , , , . Using these samples, we can approximate in the orthogonal HF domain as given in the following equation.

where , .

Similarly,

From Equations (12)–(15),

where

, .

Following the same procedure, we can estimate in the orthogonal HF domain as bestowed in the next equation.

where

, , , .

The HF estimate of the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of order of the function is

where , , , and are the generalized one-shot operational matrices and act as a fractional (generalized) integrator in the orthogonal HF domain.

If the order of a fractional integral is one, then , , , , i.e., the generalized one-shot operational matrices become the classical one-shot operational matrices, as when the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of reduces to the first-order integral of when .

We now verify the derived HF estimate of the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of order of . Let us take a time function . We choose the step size as 0.125 ().

The exact Riemann–Liouville fractional integral of is

We use to denote the HF estimate of . As we notice in Table 1, the expression in (18) formulated using the generalized one-shot HF operational matrices is able to give a highly accurate approximation of even for a small value of . It is, therefore, confirmed that the derived generalized one-shot HF operational matrices are precise and indeed act as a generalized integrator in the orthogonal HF domain.

Table 1.

Absolute error produced by HFs.

It is found (Table 2) that the one-shot operational matrices presented in [35] for ( is an integer) times repeated integration become incorrect when . So they fail to act as an integrator in the HF domain for . Using these one-shot operational matrices for solving integral or differential equations involving integrals and/or derivatives of an order greater than or equal to three introduces a larger error than the error produced via our approach (Equation (18)). To prove this fact, let us consider the numerical example from Section 9 of [35].

Table 2.

Comparison of the accuracy of our approach and the approach in [35].

The approximate solution of (20) is computed by using (18) and the percentage error is calculated and compared (Table 3) to that obtained in [35]. As the third-order one-shot operational matrices are inaccurate, the approximate solution in [35] is less accurate than the approximate solution acquired by our approach.

Table 3.

Comparison of % error produced by two approaches.

4. Numerical Method to Solve the System of Fractional-Order Differential Equations

We develop here a numerical method (the pseudo code is given in Appendix B) to find the approximate solution of the system of fractional-order differential equations via the orthogonal HFs.

Let us consider the following general form of the system of fractional-order differential equations

with the initial conditions , .

We describe the unknown function, , of the system of fractional-order differential equations in (21) as

where is a new unknown function, can be chosen such that .

Employing (22) and carrying out fractional integration on (21) results in the form given below.

This modified system of fractional Volterra integral equations owns zero initial conditions.

Expanding the unknown function, , and the nonlinear function, , into orthogonal HFs,

where , , .

.

where , , .

From (23) to (25),

Employing the generalized one-shot operational matrices,

Equating the coefficients of the SHF set, , and the TF set, ,

Solving the above system of nonlinear algebraic equations gives the coefficient vectors , and .

From Equation (24), we have the HF estimate of the new unknown function .

The actual unknown, , is approximated in the orthogonal HF domain as

5. Convergence Analysis

In this section, we shall prove that the HF approximate solution of the system of fractional-order differential equations in (21) converges to its exact solution when is large enough.

Let and be the exact and the approximate solution of (21), respectively.

Let us define an error between and as

Let us suppose that the nonlinear function satisfies the Lipschitz condition uniformly in . Therefore, there exists a positive constant, , called the Lipschitz constant, such that

Under these assumptions, we state the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

The HF approximate solution of (21) converges to its exact solution if and only if

Proof.

Equation (30) can be written as

Therefore,

If , the error tends to zero when a sufficiently large number of subintervals is considered. This completes the proof. □

6. Numerical Examples

In this section, the numerical method devised in Section 4 is applied to the systems of linear and nonlinear fractional-order differential equations. All numerical experiments presented in this study were performed using MATLAB (version R2021b and later) on a personal computer equipped with a 13th-generation Intel® Core™ i7-1355U processor and 1.70 GHz RAM. The proposed numerical algorithm was implemented through original source code written by the authors. The resulting system of algebraic equations, obtained via the hybrid function-based formulation, was solved using MATLAB’s built-in fsolve function. The default trust-region dogleg algorithm was used. The only adjustable parameter in the method is the step size h, which determines the time discretization level and resolution of the hybrid basis functions. The value of h was selected based on the complexity of the test problems. For simpler systems, a moderate step size (e.g., h = 1/10) was sufficient to achieve high accuracy, whereas more complex problems involving nonlinearities or variable coefficients required smaller step sizes (e.g., h = 1/300 to h = 1/500) to maintain solution fidelity and numerical stability.

Example 1.

Consider the following system of nonlinear fractional-order differential equations.

The analytical solution is unknown.

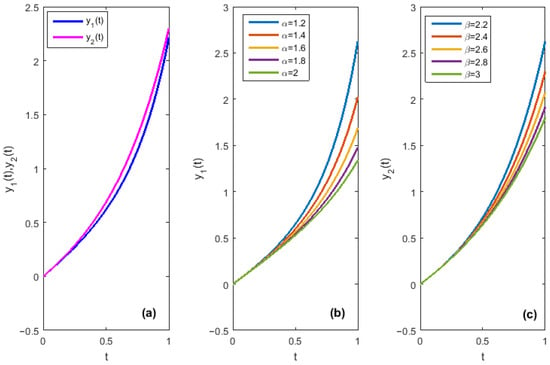

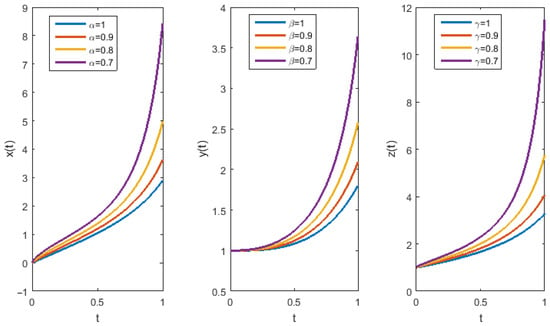

The piecewise linear HF solutions (Figure 1a) obtained by our numerical method using the step size of 0.001 for and are in good accordance with the solutions acquired via the fractional differential transform method in [36] (see Example 2 in [36]) and by the Legendre wavelet-based numerical method in [37] (see Example 5.2 in [37]). For different and , our numerical method (with ) produced the same results (Figure 1b,c) as the Legendre wavelet-based numerical method provided in [37] (see Example 5.2 in [37]).

Figure 1.

HF solutions of Example 6.1 for and (Subplot (a)) and for other values of and (Subplots (b,c)).

Example 2.

Consider the system of linear fractional-order differential equations

The exact solution when and is , .

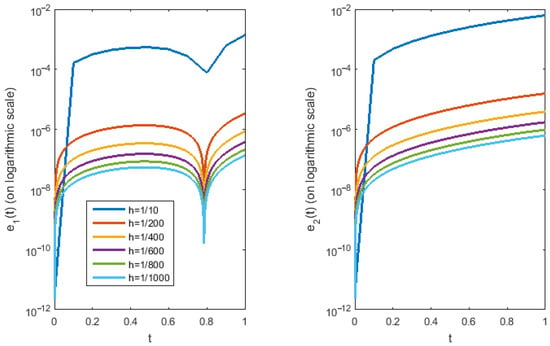

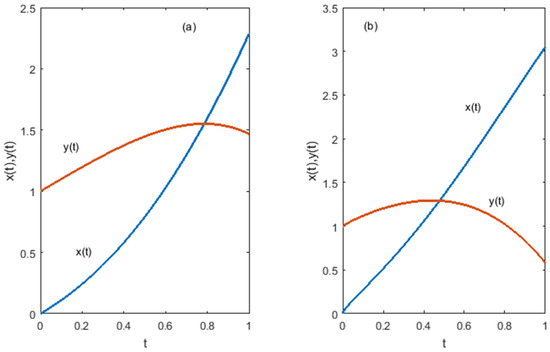

The absolute error between the exact solution and the HF solution is computed for different values of and displayed in Figure 2. Table 4 presents the -norm of the absolute error. The HF solutions for the integer-order case (, ) and the fractional-order case (, ) shown in Figure 3 are in good agreement with the approximate solutions obtained in [36] (see Example 1 in [36]), [22] (see Example 6.2 in [22]), and [20] (see Example 4.1 in [20]).

Figure 2.

Absolute error produced via our numerical method for .

Table 4.

Error analysis of Example 2.

Figure 3.

HF solution of Example 2 for (a) and (b).

Example 3.

The system of nonlinear fractional-order differential equations is

The given problem has no closed-form solution.

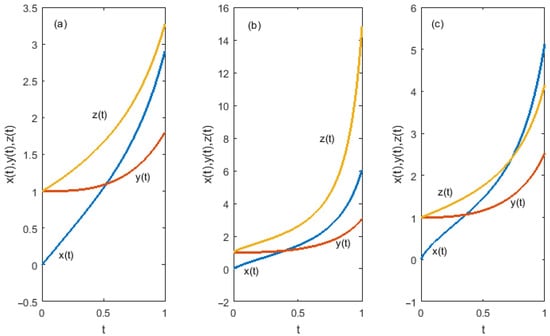

For (Figure 4a) and (Figure 4b), our numerical method (with step size of 0.001) produced the same results as obtained in [37] (see Example 5.3 in [37]). The piecewise linear HF solution (Figure 4c) for is in accordance with the solution of the Adomian decomposition method and the variational iteration method in [22] (see Example 6.4 in [22]). Figure 5 shows the results of our method for other values of , , and , which exactly match the solutions obtained in [37].

Figure 4.

HF solution of Example 3 for (a), (b), and (c).

Figure 5.

HF solutions of Example 3 for other values of , , and .

Example 4

[38]. The fractional-order mathematical model describing the effects of smoking in a population is given as

where , , , .

Here is the number of potential smokers reacting to pro-smoking advertisements, is the number of potential smokers responding to anti-smoking ads, is the number of light smokers, is the number of chain smokers, and is the number of quitters.

We use the following model parameters and initial conditions:

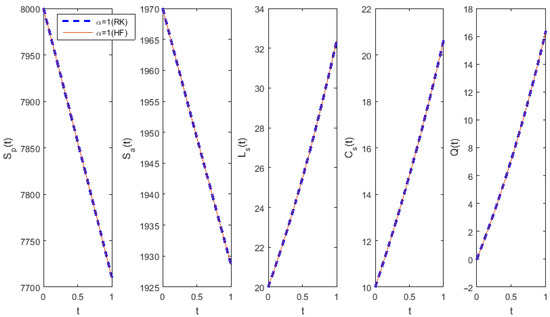

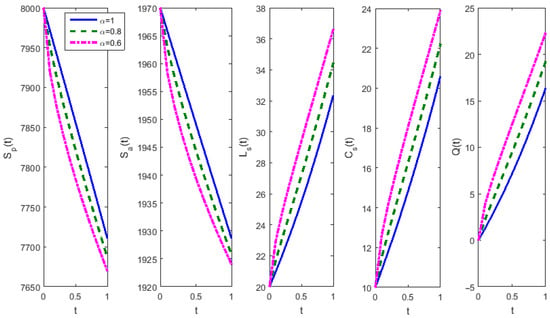

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

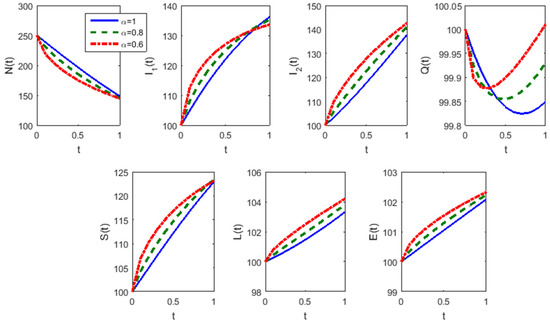

The fractional-order smoking model is slightly more complex than the fractional-order model bestowed in the preceding subsection. Figure 6 displays the comparison of the HF solution and the solution via RK fourth-order method, and Figure 7 presents the numerical solutions of the fractional-order smoking model obtained for different values of . The step size of 0.002 is employed for performing all numerical simulations. Despite the complexity and nonlinearity, the proposed numerical method demonstrates its competence to solve high-dimensional systems of nonlinear fractional-order differential equations.

Figure 6.

Numerical solution of the smoking model of order 1.

Figure 7.

Piecewise linear HF solution of the fractional-order smoking model.

Example 5

[39]. The fractional-order mathematical model for lung cancer is

where , , .

In the above fractional model, signifies the number of non-smokers, the number of light smokers, the number of heavy smokers, individuals who quit smoking permanently, individuals who stop smoking temporarily, the number of smokers who develop lung cancer, and educated individuals.

The following data is considered for numerical simulations:

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

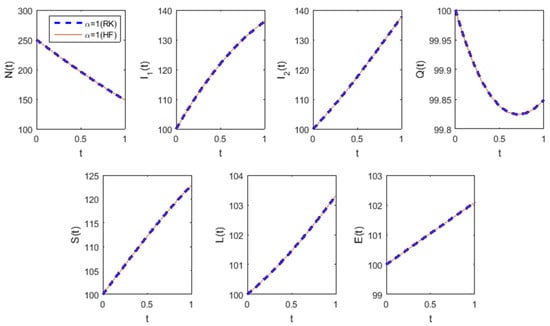

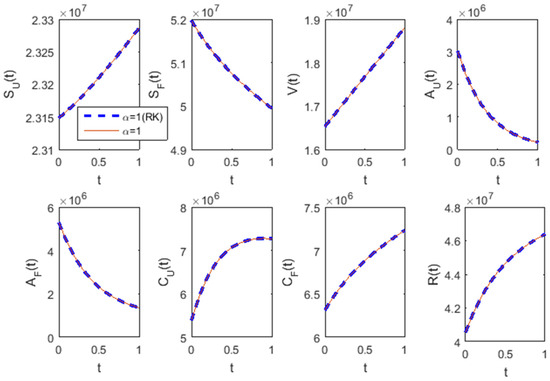

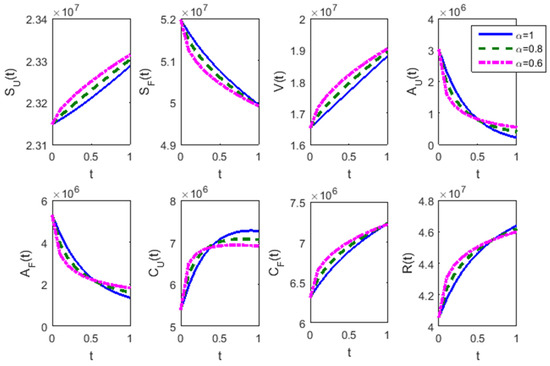

Figure 8 and Figure 9 express the fact that the proposed numerical method is so powerful that it can solve even more complicated and higher-dimensional systems of nonlinear fractional-order differential equations.

Figure 8.

Comparison of approximate solutions of the integer-order () model for lung cancer. HF solution—solid line, RK solution—dashed line.

Figure 9.

Comparison of piecewise linear HF solutions of the fractional-order model for lung cancer.

Example 6

[40]. The generalized mathematical model of Hepatitis B infection is

where is susceptible individuals under 15 years of age, is susceptible individuals at or above 15 years of age, is vaccinated individuals, is acutely infected individuals under 15 years of age, is acutely infected individuals at or above 15 years of age, is chronically infected individuals under 15 years of age, is chronically infected individuals at or above 15 years of age, and is individuals removed due to recovery from infection.

The model parameters and the initial conditions are

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

The fractional-order model of Hepatitis B infection is the most intricate of four problems we have solved so far in this paper. Using the step size of 0.002, the piecewise linear HF approximate solution is obtained via the proposed numerical method for (Figure 10) and (Figure 11). It is manifestly proved in Figure 10 that the proposed numerical method competes with a well-known numerical technique (the Runge–Kutta fourth-order method) by offering an acceptable numerical solution to such a high-dimensional nonlinear system (Equations (58)–(66)). The proposed numerical method can, therefore, be used to solve highly nonlinear and high-dimensional systems of ordinary differential equations of integer order representing complex biological processes. In the case of non-integer values of , the developed numerical method yields correct solutions that proves its suitability to real complex fractional-order mathematical models.

Figure 10.

Numerical solution of the integer-order model () of Hepatitis B infection. HF solution--solid line, RK solution--dashed line.

Figure 11.

Piecewise linear HF solutions of the fractional-order model of Hepatitis B infection.

Balancing Accuracy and Computational Cost Through Step Size Control

The resolution of the time grid, determined by the choice of step size h, has a direct impact on the effectiveness of the proposed HF-based numerical scheme. A finer discretization (smaller h) increases the density of collocation nodes, leading to a more precise capture of the system’s behavior—especially in cases involving memory effects or sharp transients, which are typical in fractional systems. In the experiments conducted, it was observed that even moderately coarse step sizes produced accurate results for lower-order and linear systems, indicating the inherent strength of the approximation framework. In more intricate examples with strong nonlinearities and variable coefficients, finer steps were employed to maintain solution accuracy, but the increase in computational cost was minimal. This favorable performance can be attributed to the one-shot operational matrices, which transform the governing equations into algebraic systems without iterative time-stepping. This transformation not only accelerates the overall computation but also ensures numerical stability, regardless of the order of the derivative or system complexity. Performance comparisons with traditional schemes suggest that the HF method achieves high accuracy with fewer discretization points, offering a significant reduction in execution time for equivalent or superior solution quality. This is particularly beneficial in applications involving high-dimensional systems or real-time requirements, where both speed and reliability are critical.

Overall, the sensitivity analysis across different step sizes confirms that the method scales gracefully with resolution. It provides a stable and efficient tool for practitioners working with multi-order differential models, offering high fidelity with relatively low computational demand.

7. Conclusions

This article introduced a unified and efficient numerical framework based on orthogonal hybrid functions (HFs) for solving systems of differential equations of arbitrary order, covering both integer and fractional derivatives. By integrating orthogonal sample-and-hold and triangular basis functions, a new class of HFs was constructed, facilitating the development of generalized one-shot operational matrices that serve as accurate and compact fractional integrators. The proposed method exhibited strong numerical performance across a diverse set of benchmark problems, including linear, nonlinear, and high-dimensional systems, as demonstrated in Examples 6.1–6.6. For integer-order cases, the method achieved accuracy comparable to the classical fourth-order Runge–Kutta scheme, while for fractional-order systems—particularly those arising in biological and epidemiological modeling—it offered enhanced stability, precision, and computational scalability. These findings highlight the versatility and robustness of the proposed approach and affirm its potential as a practical tool for applied scientists and engineers working with complex dynamical models. Furthermore, the methodology significantly broadens the application of orthogonal HFs in the realm of fractional calculus and provides a solid foundation for future extensions. As part of ongoing and future work, the proposed method will be further evaluated on stiff systems of fractional-order differential equations, which present additional challenges due to their rapidly changing solution components. The aim is to explore the method’s stability, convergence, and efficiency under stiff dynamics and to enhance its applicability to a wider class of real-world problems involving multi-scale and stiff fractional behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, S.K.D.; writing—review and editing, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Basic Properties of HFs

The components of the SHF vector, , and the TF vector, , have orthogonal property.

The product, , where , is expressed via HFs

Similarly,

whereas the product, , is estimated in the orthogonal HF domain as

The product of two functions can be approximated by HFs as given in the next equation:

The power of function, , () is expanded into orthogonal HFs using the following expression:

where , , .

Appendix B. Pseudo Code for the Proposed Method

%HF-Based Solver for Fractional Differential Equations

%This script demonstrates the implementation of the proposed method using orthogonal

%hybrid functions (HFs) and one-shot operational matrices.

%Inputs

%tspan: [0, T] (Time interval)

%N: Number of subintervals

%r: Fractional order of the derivative

%f: Function handle representing system of equations

%x0: Initial conditions

function x_approx = hf_method_solver(f, x0, r, T, N)

% Step 1: Time discretization

h = T / N;

t = linspace(0, T, N+1);

% Step 2: Construct hybrid functions (sample-and-hold + triangular)

Phi = construct_hf_basis(N, t); % [2N x (N+1)] matrix

% Step 3: Construct operational matrix for fractional integration

P_r = fractional_operational_matrix(N, r, h); % [2N x 2N] matrix

% Step 4: Initial approximation (assume solution is C' * Phi)

C0 = zeros(size(Phi, 1), 1);

% Step 5: Solve algebraic system using fsolve

opts = optimoptions('fsolve','Display','iter','FunctionTolerance',1e-10);

C_sol = fsolve(@(C) residual(C, f, Phi, P_r, t, x0), C0, opts);

% Step 6: Reconstruct approximate solution

x_approx = Phi' * C_sol;

end

%%Residual Function for FSOLVE

function R = residual(C, f, Phi, P_r, t, x0)

% Evaluate approximate x(t)

x_approx = Phi' * C;

n = length(x_approx);

R = zeros(n,1);

for i = 1:n

R(i) = P_r(i,:) * C - f(t(i), x_approx(i));

end

R(1) = x_approx(1) - x0; % Apply initial condition

end

%%Construct Hybrid Function Basis (Sample-and-hold + triangular)

function Phi = construct_hf_basis(N, t)

% For simplicity, we use identity + ramp basis as a mock-up

Phi = [eye(N+1); tril(ones(N+1))];

end

%%Generate Operational Matrix of Fractional Integration

function P_r = fractional_operational_matrix(N, r, h)

alpha = r;

P_r = zeros(2*N, 2*N);

for j = 1:2*N

for i = 1:j

P_r(i,j) = h^alpha * ((i+j+1)^alpha - (i-j)^alpha) / gamma(alpha+1);

end

end

end

References

- Oldham, K.B.; Spanier, J. The Fractional Calculus: Theory and Applications of Differentiation and Integration to Arbitrary Order; Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Atanackovic, T.M.; Pilipovic, S.; Stankovic, B.; Zorica, D. Fractional Calculus with Applications in Mechanics: Vibrations and Diffusion Processes; Wiley: London, UK; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, R. Fractional Calculus: An Introduction for Physicists; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Losa, G.A.; Merlini, D.; Nonnenmacher, T.F.; Weibel, E.R. Fractals in Biology and Medicine; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi, F. Fractional Calculus and Waves in Linear Viscoelasticity; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Golmankhneh, A.K.; Yang, X.J.; Baleanu, D. Einstein field equations within local fractional calculus. Rom. J. Phys. 2015, 60, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, W.M.; El-Khazali, R. Fractional-order dynamical models of love. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 2007, 33, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Xu, S.; Yang, J. Dynamical models of happiness with fractional order. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2010, 15, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Approximate solution of nonlinear fractional order biochemical reaction model by multistage new iterative method. J. Fract. Calc. Appl. 2014, 5, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Numerical solution of fractional order differential-algebraic equations using generalized triangular operational matrices. J. Fract. Calc. Appl. 2015, 6, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Numerical solution of multi-order fractional differential equations using generalized triangular function operational matrices. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 263, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Design of robust fractional PID controller using triangular strip operational matrices. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2015, 18, 1291–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Generalized mathematical model of chronic hepatitis C infection. J. Fract. Calc. Appl. 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Fractional Order Processes: Simulation, Identification and Control; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781138586741. [Google Scholar]

- Damarla, S.K.; Kundu, M. Piecewise linear approximate solution of fractional order non-stiff and stiff differential-algebraic equations by orthogonal hybrid functions. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 2020, 6, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Adomian, G. Solving Frontier Problems of Physics: The Decomposition Method; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H. Variational iteration method–a kind of non-linear analytical technique: Some examples. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 1999, 34, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.H. Homotopy perturbation technique. Comput. Method Appl. Mech. Eng. 1999, 178, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurigat, M.; Momani, S.; Odibat, Z.; Alawneh, A. The homotopy analysis method for handling systems of fractional differential equations. Appl. Math. Modell. 2010, 34, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K.; Ford, N.J.; Freed, A.D. A predictor-corrector approach for the numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 2002, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odibat, Z.M.; Momani, S. An algorithm for the numerical solution of differential equations of fractional order. J. Appl. Math. Inform. 2008, 26, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sheybak, M.; Tajadodi, H. Numerical solutions of fractional chemical kinetics system. Nonlinear Dyn. Syst. Theory 2019, 19, 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Afreen, A.; Raheem, A. Study of a nonlinear system of fractional differential equations with deviated arguments via Adomian decomposition method. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 2022, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habahbeh, A. Numerical solution of a system of fractional ordinary differential equations by a modified variational iteration procedure. WSEAS Trans. Math. 2022, 21, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, T.; Amin, R.; Shah, K.; Al-Mdallal, Q.; Jarad, F. Efficient sustainable algorithm for numerical solutions of systems of fractional order differential equations by Haar wavelet collocation method. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 2391–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İbiş, B.; Bayram, M.; Ağargün, A.G. Applications of fractional differential transform method to fractional differential-algebraic equations. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2011, 4, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrás, L.L.; Ford, N.; Morgado, M.L.; Rebelo, M. High-order methods for systems of fractional ordinary differential equations and their application to time-fractional diffusion equations. Math. Comput. Sci. 2020, 15, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syam, S.M.; Siri, Z.; Altoum, S.H.; Kasmani, R.M. An efficient numerical approach for solving systems of fractional problems and their applications in science. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Razzaq, O.A.; Ara, A.; Riaz, F. Numerical solution of system of fractional differential equations in imprecise environment. In Numerical Simulations in Engineering and Science (Chapter 8); IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alzuheiri, Z.H. Solving of Certain Systems of Fractional Differential Equations. Master’s Thesis, Zarqa University, Zarqa, Jordan, 2015. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Reutskiy, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Pubu, C. A novel method for linear systems of fractional ordinary differential equations with applications to time-fractional PDEs. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 139, 1583–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, A.; Roychoudhury, S.; Sarkar, G. Analysis Identification of Time-Invariant Systems Time-Varying Systems Multi-Delay Systems Using Orthogonal Hybrid Functions Theory Algorithms with MATLAB; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.; Purkait, A.; Ganguly, A.; Saha, K. Hybrid function based analysis of simple networks. In Advanced Computing Networking and Informatics; Kundu, M.K., Mohapatra, D.P., Konar, A., Chakraborty, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, A.; Ganguly, A.; Sarkar, G.; Biswas, A. Numerical solution of third order linear differential equations using generalized one-shot operational matrices in orthogonal hybrid function domain. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 219, 1485–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturk, V.S.; Odibat, Z.M.; Momani, S. An approximate solution of a fractional order differential equation model of human T-cell lymphotropic virus I (HTLV-I) infection of CD4+ T-cells. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ke, X.; Wei, Y. Numerical algorithm to solve system of nonlinear fractional differential equations based on wavelets method and the error analysis. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 251, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhaya, K. Mathematical Modelling on the Effects of Passive Smoking in the Presence of Pro and Anti-Smoking Campaigns. Master’s Thesis, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam Region, Tanzania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Estefania, C.A.; Gonzalez, C.; Rios-Soto, K.R.; Summerville, E.D.; Song, B.; Castillo-Chavez, C. A Mathematical Model for Lung Cancer: The Effects of Second-Hand Smoke and Education; Biometrics Unit Technical Report BU-1525-M.; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrahman, S.; Akinwande, N.I.; Abubakar, U.Y. Mathematical solutions for hepatitis b virus infection in Nigeria. J. Res. Natl. Dev. 2013, 11, 302–313. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).