Translation Can Distort the Linguistic Parameters of Source Texts Written in Inflected Language: Multidimensional Mathematical Analysis of “The Betrothed”, a Translation in English of “I Promessi Sposi” by A. Manzoni

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Within the framework of fidelity to I promessi sposi, I felt adjustments were needed due to fundamental stylistic and grammatical differences between English and Italian conventions. For example, Manzoni often adopts the periodic structure for his sentences, stringing together clause after clause with a series of semicolons. Italian enables and even encourages this style, since as an inflected language, Italian embeds the person and number of the subject—the I, you, or we—in the verb. Subject pronouns are used minimally, so a series of clauses with the same subject can result in a sentence the length of a page. The period, or “full stop”, is regarded with barely concealed horror, as if it truncates an otherwise beautiful sentence. English is not as economical in its use of subject pronouns, and actually requires them, so rather than mimic the periodic style at full length, I broke his sentences up into smaller parcels, sometimes (but not always) using periods where he used semicolons, feeling that they do not impose the same sense of finality in English as they do in Italian.”

2. Example of Translation: Incipit

3. Total Statistics

4. Exploratory Data Analysis: Relationships Between Italian and English Linguistic Variables

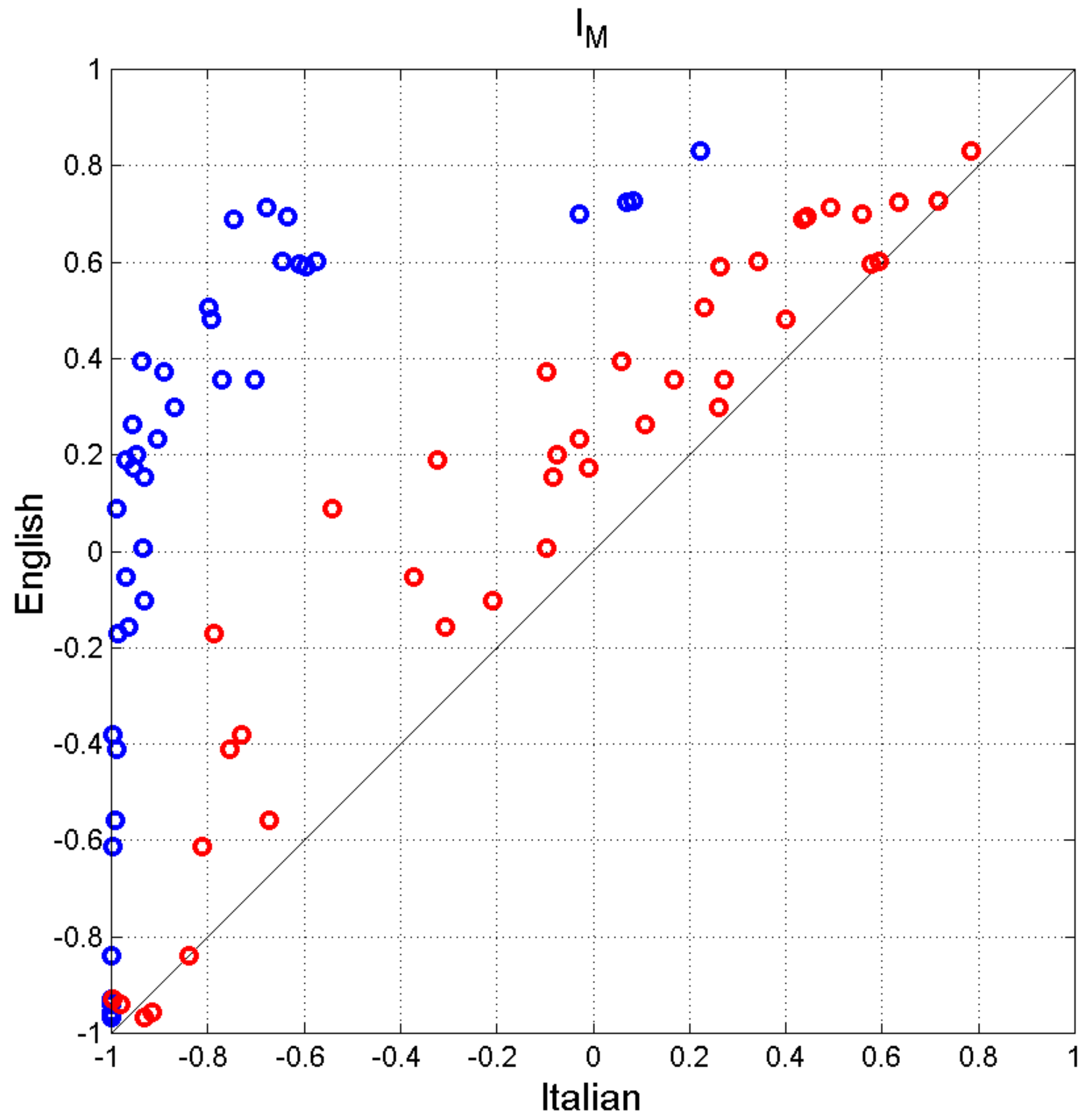

5. Deep Language Variables

- (a)

- is very similar in both languages, for the reason detailed in Section 4.

- (b)

- in Italian is, as expected, quite a bit larger than in English. It becomes smaller and very similar to English only if semicolons are replaced by periods (Italian–E).

- (c)

- is significantly smaller in Italian than in English, due to the large number of interpunctions present in Italian. This parameter does not depend on the type of interpunctions; therefore, it is the same also in Italian–E.

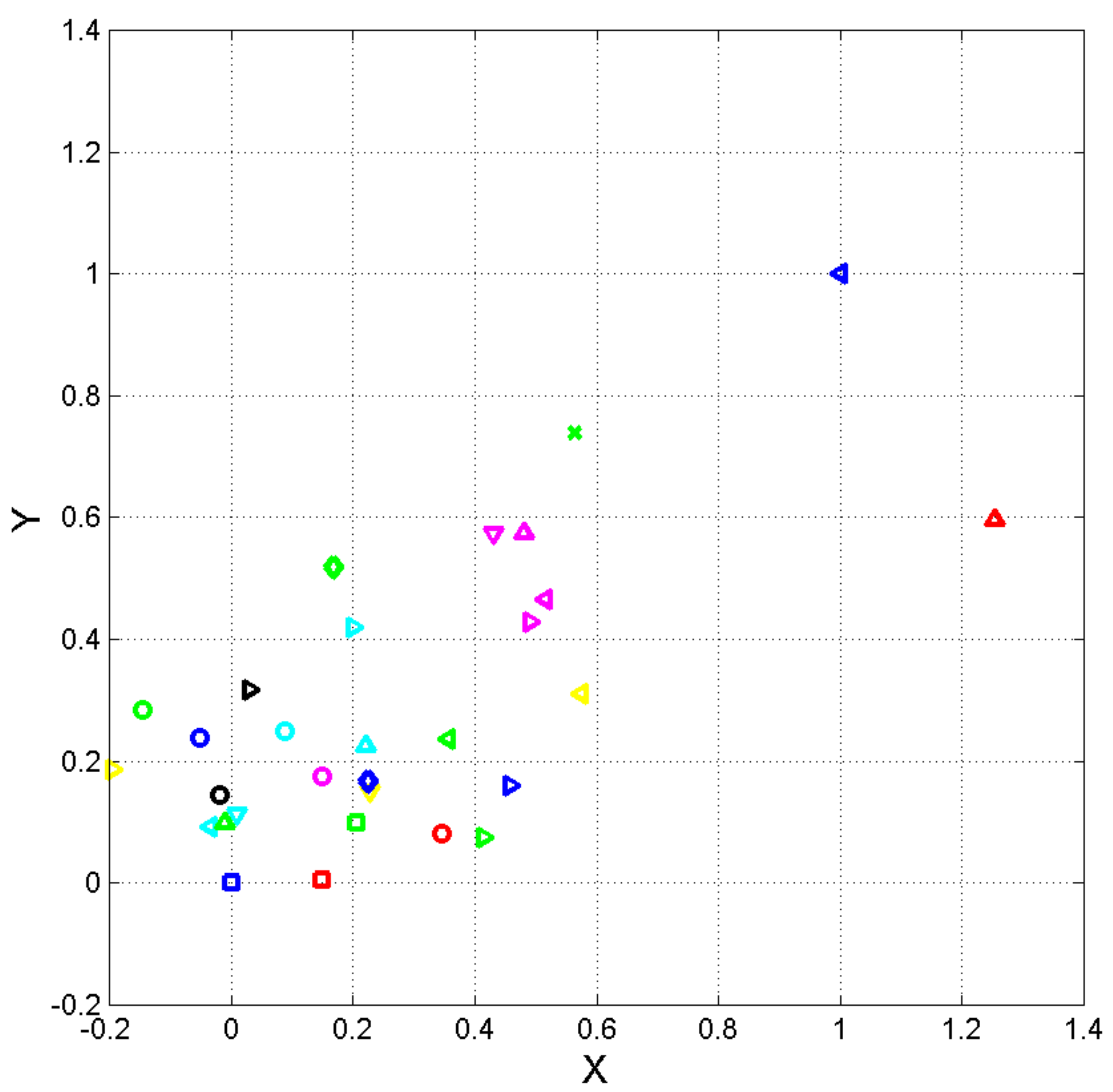

6. Geometrical Representation of Alphabetical Texts

6.1. Vector Representation of Texts

6.2. Error Probability

7. Short–Term Memory of Writers/Readers

- (a)

- ranges approximately within Miller’s bounds.

- (b)

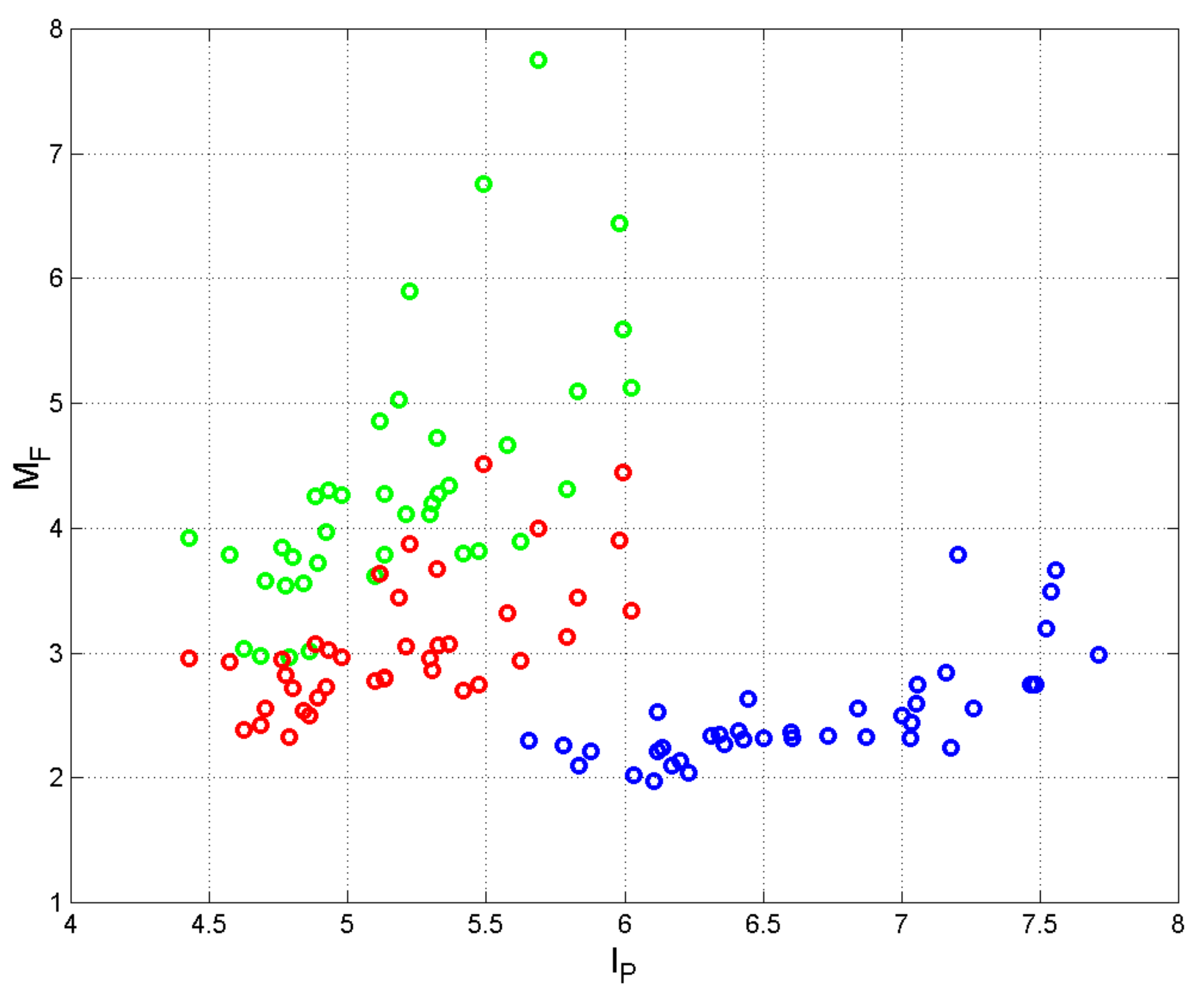

- As the number of words in a sentence, increases, can increase but not linearly, because the first buffer cannot hold, approximately, a number of words larger than that empirically predicted by Miller’s Law; therefore, saturation must occur. Scatterplots like that shown in Figure 9 provide an insight into the short–term memory capacity engaged when reading/writing a text, because a writer is also a reader of their own text.

8. Linguistic Channels

8.1. Four Linguistic Channels

- (a).

- Sentence channel (S–channel);

- (b).

- Interpunctions channel (I–channel);

- (c).

- Word interval channel (WI–channel);

- (d).

- Characters channel (C–channel).

8.2. General Theory of Linear Channels

8.3. The Channel with a Single Scatterplot: One–to–One Correspondence

8.4. Performance of Linguistic Channels in Italian and in English

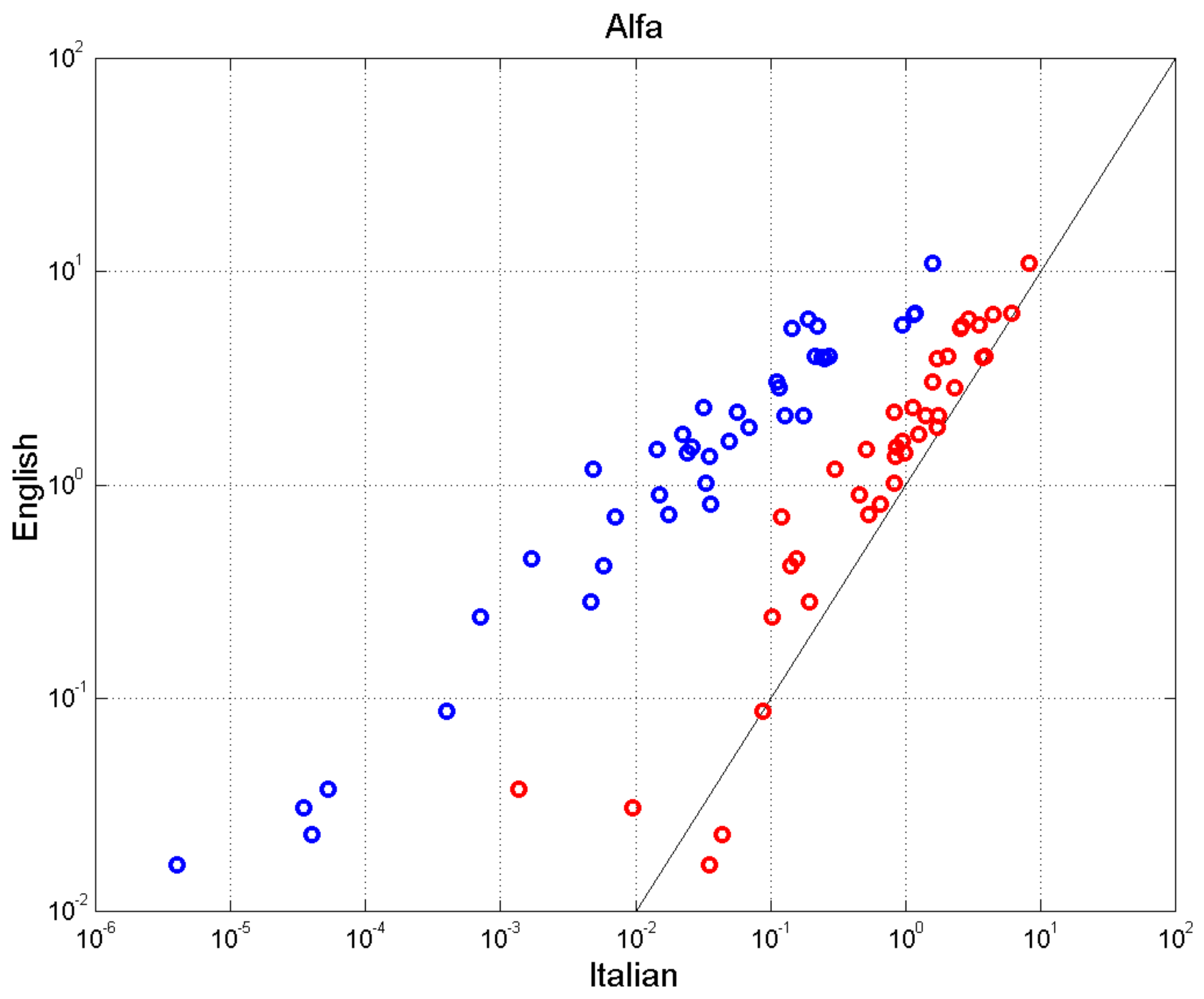

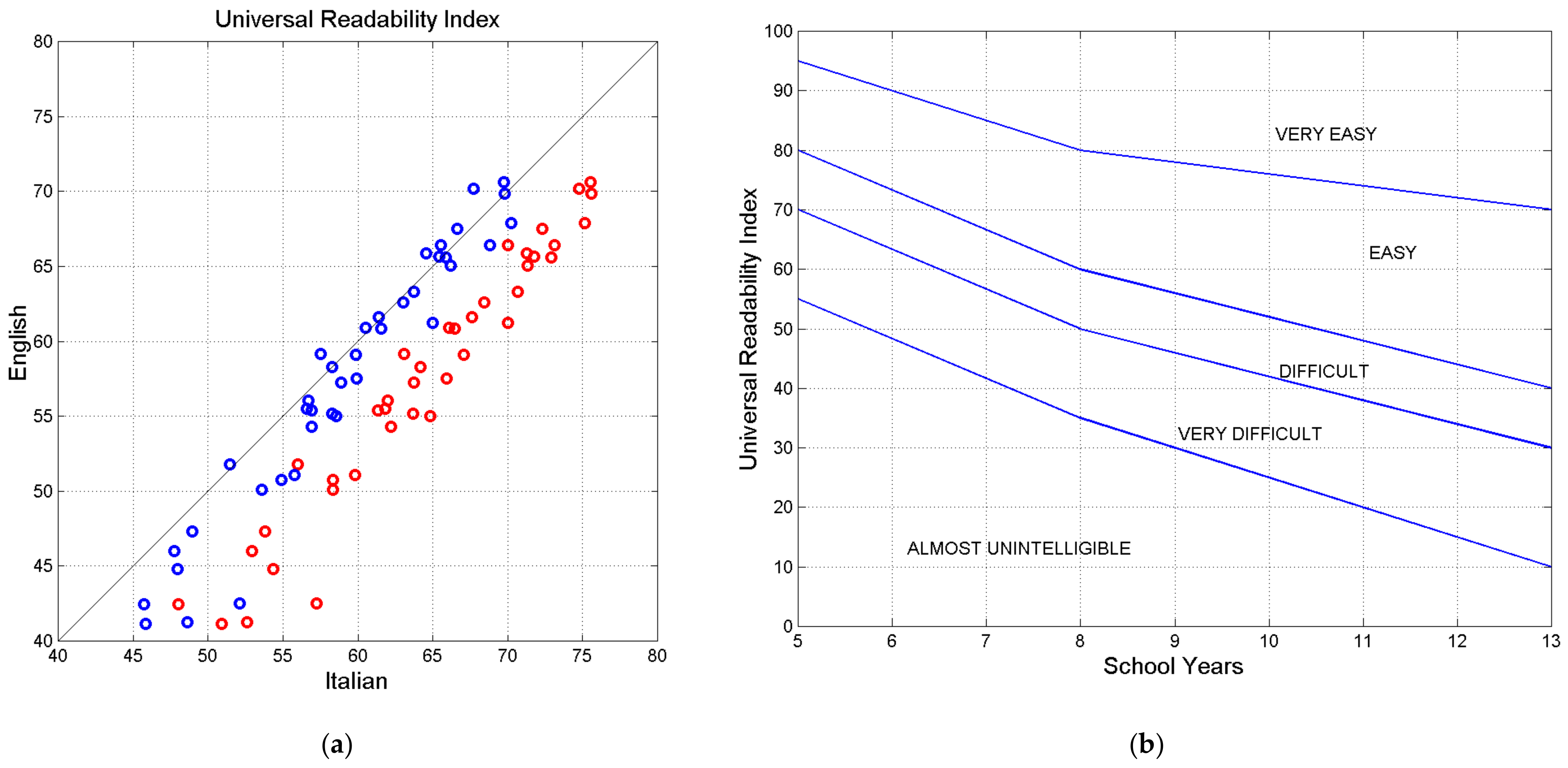

9. Universal Readability Index

- (a)

- For , the readability of English is lower than that of Italian; for , the two values agree more, as they align more with the 45° line (in Italian, in this range, the lower values of in Equation (32) balance the larger values of ).

- (b)

- If semicolons are replaced by periods, the Italian–E text is much more readable than the English text, because is noticeably reduced while does not change.

10. Summary and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Incipit Paragraph

“Quel ramo del lago di Como, che volge a mezzogiorno, tra due catene non interrotte di monti, tutto a seni e a golfi, a seconda dello sporgere e del rientrare di quelli, vien, quasi a un tratto, a ristringersi, e a prender corso e figura di fiume, tra un promontorio a destra, e un’ampia costiera dall’altra parte; e il ponte, che ivi congiunge le due rive, par che renda ancor più sensibile all’occhio questa trasformazione, e segni il punto in cui il lago cessa, e l’Adda rincomincia, per ripigliar poi nome di lago dove le rive, allontanandosi di nuovo, lascian l’acqua distendersi e rallentarsi in nuovi golfi e in nuovi seni. La costiera, formata dal deposito di tre grossi torrenti, scende appoggiata a due monti contigui, l’uno detto di san Martino, l’altro, con voce lombarda, il Resegone, dai molti suoi cocuzzoli in fila, che in vero lo fanno somigliare a una sega: talché non è chi, al primo vederlo, purché sia di fronte, come per esempio di su le mura di Milano che guardano a settentrione, non lo discerna tosto, a un tal contrassegno, in quella lunga e vasta giogaia, dagli altri monti di nome più oscuro e di forma più comune. Per un buon pezzo, la costa sale con un pendìo lento e continuo; poi si rompe in poggi e in valloncelli, in erte e in ispianate, secondo l’ossatura de’ due monti, e il lavoro dell’acque. Il lembo estremo, tagliato dalle foci de’ torrenti, è quasi tutto ghiaia e ciottoloni; il resto, campi e vigne, sparse di terre, di ville, di casali; in qualche parte boschi, che si prolungano su per la montagna. Lecco, la principale di quelle terre, e che dà nome al territorio, giace poco discosto dal ponte, alla riva del lago, anzi viene in parte a trovarsi nel lago stesso, quando questo ingrossa: un gran borgo al giorno d’oggi, e che s’incammina a diventar città. Ai tempi in cui accaddero i fatti che prendiamo a raccontare, quel borgo, già considerabile, era anche un castello, e aveva perciò l’onore d’alloggiare un comandante, e il vantaggio di possedere una stabile guarnigione di soldati spagnoli, che insegnavan la modestia alle fanciulle e alle donne del paese, accarezzavan di tempo in tempo le spalle a qualche marito, a qualche padre; e, sul finir dell’estate, non mancavan mai di spandersi nelle vigne, per diradar l’uve, e alleggerire a’ contadini le fatiche della vendemmia. Dall’una all’altra di quelle terre, dall’alture alla riva, da un poggio all’altro, correvano, e corrono tuttavia, strade e stradette, più o men ripide, o piane; ogni tanto affondate, sepolte tra due muri, donde, alzando lo sguardo, non iscoprite che un pezzo di cielo e qualche vetta di monte; ogni tanto elevate su terrapieni aperti: e da qui la vista spazia per prospetti più o meno estesi, ma ricchi sempre e sempre qualcosa nuovi, secondo che i diversi punti piglian più o meno della vasta scena circostante, e secondo che questa o quella parte campeggia o si scorcia, spunta o sparisce a vicenda. Dove un pezzo, dove un altro, dove una lunga distesa di quel vasto e variato specchio dell’acqua; di qua lago, chiuso all’estremità o piuttosto smarrito in un gruppo, in un andirivieni di montagne, e di mano in mano più allargato tra altri monti che si spiegano, a uno a uno, allo sguardo, e che l’acqua riflette capovolti, co’ paesetti posti sulle rive; di là braccio di fiume, poi lago, poi fiume ancora, che va a perdersi in lucido serpeggiamento pur tra’ monti che l’accompagnano, degradando via via, e perdendosi quasi anch’essi nell’orizzonte. Il luogo stesso da dove contemplate que’ vari spettacoli, vi fa spettacolo da ogni parte: il monte di cui passeggiate le falde, vi svolge, al di sopra, d’intorno, le sue cime e le balze, distinte, rilevate, mutabili quasi a ogni passo, aprendosi e contornandosi in gioghi ciò che v’era sembrato prima un sol giogo, e comparendo in vetta ciò che poco innanzi vi si rappresentava sulla costa: e l’ameno, il domestico di quelle falde tempera gradevolmente il selvaggio, e orna vie più il magnifico dell’altre vedute.Per una di queste stradicciole, tornava bel bello dalla passeggiata verso casa, sulla sera del giorno 7 novembre dell’anno 1628, don Abbondio…”

“The branch of Lake Como that turns south between two unbroken mountain chains, bordered by coves and inlets that echo the furrowed slopes, suddenly narrows to take the flow and shape of a river, between a promontory on the right and a wide shoreline on the opposite side. The bridge that joins the two sides at this point seems to make this transformation even more visible to the eye and mark the spot where the lake ends and the Adda begins again, to reclaim the name lake where the shores, newly distant, allow the water to spread and slowly pool into fresh inlets and coves. Formed from the sediment of three large streams, the shoreline lies at the foot of two neighboring mountains, the first called San Martino, the second, in Lombard dialect, the “Resegone”—the big saw—after the row of many small peaks that really do make it look like one. So clear is the resemblance that no one—provided they are directly facing it, from the northern walls of Milan, for example—could fail to immediately distinguish this summit from other mountains in that long and vast range with more obscure names and more common shapes. For a good stretch the shore rises upward into a smooth rolling slope. Then it breaks off into small hills and ravines, steep inclines and flat terraces, molded by the contours of the two mountains and the erosion of the waters. The water’s edge, cut by the outlets of the streams, is almost all pebbles and stones. The rest is fields and vineyards, dotted with towns, villages, and hamlets. Here and there a woods climbs up the side of the mountain.Lecco, the capital that lends its name to the province, stands at a short remove from the bridge, and is on and indeed partly inside the lake when the water rises. Nowadays it is a large town well on its way to becoming a city. At the time of the events I am about to relate, this already good–sized village was also fortified, which conferred upon it the honor of a commander in residence, and the benefit of a permanent garrison of Spanish soldiers, who taught modesty to the girls and women of the town, gave an occasional tap on the back to a husband or father, and, at summer’s end, never failed to spread out into the vineyards to thin the grapes and relieve the peasants of the trouble of harvesting them.Roads and footpaths used to run—and still do—from town to town, from summit to shore, from hill to hill. Some are more or less steep; some are level. In places they dip, sinking between two walls, and all you can see when you look up is a patch of sky and a mountaintop. In others they climb to open embankments, where the view encompasses a broader panorama, always rich, always new, depending on the vantage point and how much of the vast expanse can be seen, and on whether the landscape protrudes or recedes, stands out from or disappears into the horizon.One piece, then another, then a long stretch of that vast and varied mirror of water. Over here, the lake—terminating at the far end or vanishing into a cluster, a procession of mountains—slowly growing wider between yet more mountains that unfold before the eyes, one by one, whose image, alongside that of the towns by the lake, is reflected upside down in the water. Over there, a bend in the river, then more lake, then river again disappearing into a shiny ribbon curling between the mountains on either side, and slowly descending to vanish on the horizon.The place from which you contemplate these varied sights offers its own display on every side. The mountain along whose slopes you walk unfolds its peaks and crags above and around you, distinct, prominent, changing with every step, opening and then circling into ridges where a lone summit had at first appeared. The shapes that were reflected in the lake only minutes before now appear close to the summit. The tame, pleasant foothills temper the wild landscape and enhance the magnificence of the other vistas.Along one of these footpaths, on the evening of the seventh day of November in 1628, Don Abbondio…”

Appendix B. Example of Texts

“Oh Signore! pretendere! Cosa posso pretendere io meschina, se non che lei mi usi misericordia? Dio perdona tante cose, per un’opera di misericordia! Mi lasci andare; per carità mi lasci andare! Non torna conto a uno che un giorno deve morire di far patir tanto una povera creatura. Oh! lei che può comandare, dica che mi lascino andare! M’hanno portata qui per forza. Mi mandi con questa donna a *** dov’è mia madre. Oh Vergine santissima! mia madre! mia madre, per carità, mia madre! Forse non è lontana di qui... ho veduto i miei monti! Perché lei mi fa patire? Mi faccia condurre in una chiesa. Pregherò per lei, tutta la mia vita. Cosa le costa dire una parola? Oh ecco! vedo che si move a compassione: dica una parola, la dica. Dio perdona tante cose, per un’opera di misericordia!”

“Oh, sir! What do I expect? What can a poor girl like me expect? Only your mercy. God will forgive many things for an act of mercy! Let me go, for the love of God, let me go! You, who will also have to face your maker one day: What do you have to gain from causing a poor creature so much suffering? You have the power to give orders: So tell them to let me go! They brought me here by force. Send me with this woman to ***, where my mother lives. Oh Blessed Virgin! My mother! My mother, for goodness’ sake, my mother! Perhaps it is not far from here. I saw my mountains! Why are you making me suffer? Tell them to take me to a church. I will pray for you for the rest of my life. What would it cost you to say one word? Ah, yes! I can see that you are moved to pity: Say the word, say it. God will forgive many things for an act of mercy!”

Appendix C. List of Mathematical Symbols and Meaning

| Symbol | Definitions |

| Cp | Characters per word |

| D | Domestication index |

| GU | Universal readability index |

| IM | Mismatch index |

| Ip | Word interval |

| MF | Word intervals per sentence |

| PF | Words per sentence |

| R | Noise–to–signal ratio |

| Rm | Regression noise–to–signal ratio |

| Rr | Correlation noise–to–signal ratio |

| S | Total number of sentences |

| W | Total number of words |

| nC | Number of characters |

| nW | Number of words |

| nS | Number of sentences |

| nI | Number of interpunctions |

| Number of word intervals | |

| 𝛾 | Signal–to–noise ratio |

| Γ | Signal–to–noise ratio (dB) |

| mjk | Slope of regression line of text j versus text k |

| rjk | Correlation coefficient between text j and text k |

Appendix D. Inequalities

References

- Matricciani, E. Deep Language Statistics of Italian throughout Seven Centuries of Literature and Empirical Connections with Miller’s 7 ∓ 2 Law and Short−Term Memory. Open J. Stat. 2019, 9, 373–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. A Statistical Theory of Language Translation Based on Communication Theory. Open J. Stat. 2020, 10, 936–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Multiple Communication Channels in Literary Texts. Open J. Stat. 2022, 12, 486–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Linguistic Mathematical Relationships Saved or Lost in Translating Texts: Extension of the Statistical Theory of Translation and Its Application to the New Testament. Information 2022, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Capacity of Linguistic Communication Channels in Literary Texts: Application to Charles Dickens’ Novels. Information 2023, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Linguistic Communication Channels Reveal Connections between Texts: The New Testament and Greek Literature. Information 2023, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Is Short−Term Memory Made of Two Processing Units? Clues from Italian and English Literatures down Several Centuries. Information 2024, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. A Mathematical Structure Underlying Sentences and Its Connection with Short–Term Memory. Appl. Math 2024, 4, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catford, J.C. A Linguistic Theory of Translation—An Essay in Applied Linguistics; Oxford Univeristy Press: Oxford, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, T.R. Translation and Translating: Theory and Practice; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Proshina, Z. Theory of Translation; Far Eastern University Press: Manila, Philippines, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, R. (Ed.) The Art of Translation: Voices from the Field; North-eastern University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wilss, W. Knowledge and Skills in Translator Behaviour; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, G.M. Literary Translation. Hung. Stud. Engl. 1991, 22, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, T. Literary Translation: Old and New Challenges. Int. J. Arab.—Engl. Stud. 2012, 13, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nũñez, K.J. Literary translation as an act of mediation between author and reader. Estud. Traducción 2012, 2, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaerts, L.; De Bleeker, L.; De Wilde, J. Narration and translation. Lang. Lit. 2014, 23, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazala, H.S. Literary Translation from a Stylistic Perspective. Stud. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2015, 3, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, X. A New Perspective on Literary Translation. Strategies Based on Skopos Theory. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2015, 5, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, J. (Ed.) The Routledge Companion to Translation Studies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Munday, J. Introducing Translation Studies. Theories and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Panou, D. Equivalence in Translation Theories: A Critical Evaluation. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2013, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Saule, B.; Aisulu, N. Problems of translation theory and practice: Original and translated text equivalence. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 136, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krein-Kühle, M. Translation and Equivalence. In Translation: A Multidisciplinary Approach; House, J., Ed.; Palgrave Advances in Language and Linguistics: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani, E. Multi–Dimensional Data Analysis of Deep Language in J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Reveals Tight Mathematical Connections. AppliedMath 2024, 4, 927–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuti, L. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni, A. The Betrothed; Moore, M.F., Translator; The Modern Library: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cella, R. Storia dell’italiano; Società Editrice Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frare, P. Una struttura in movimento: Sulla forma artistica dei «I promessi sposi». Italianist 1996, 16, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboni, G. La scrittura purgata: Sulla cronologia della seconda minuta dei Promessi sposi. Filol. Ital. 2008, 5, 1000–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Frare, P. La scrittura Dell’inquietudine: Saggio su Alessandro Manzoni; L.S. Olschki: Firenze, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frare, P.; Salvioli, M. Prodigi di misericordia e forza del linguaggio. Sui capitoli XXI e XXIII dei «Promessi sposi». Munera 2016, 3, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bruthiaux, P. The Rise and Fall of the Semicolon: English Punctuation Theory and English Teaching Practice. Appl. Linguist. 1995, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M. Whatever Happened to the Paragraph? Coll. Engl. 2007, 69, 470–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C. Points of Contention: Rethinking the Past, Present, and Future of Punctuation. Crit. Inq. 2012, 38, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Readability Indices Do Not Say It All on a Text Readability. Analytics 2023, 2, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulis, A. Probability & Statistics; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, B.W. Statistical Theory, 2nd ed.; MacMillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.A. The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information. Psychol. Rev. 1955, 101, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, R.G. Short–term memory: Where do we stand? Mem. Cogn. 1993, 21, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, J.E.; Idiart, M.A.P. Storage of 7 ± 2 Short–Term Memories in Oscillatory Subcycles. Science 1995, 267, 1512–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. The magical number 4 in short−term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 24, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelder, B.L. The Magical Number 7 ± 2: Span Theory on Capacity Limitations. Behav. Brain Sci. 2001, 24, 116–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Ozdemir, M.S. Why the Magic Number Seven Plus or Minus Two. Math. Comput. Model. 2003, 38, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N.; Hitch, G.J. A revised model of short–term memory and long–term learning of verbal sequences. J. Mem. Lang. 2006, 55, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Measures of Short–Term Memory: A Historical Review. Cortex 2007, 43, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathy, F.; Feldman, J. What’s magic about magic numbers? Chunking and data compression in short−term memory. Cognition 2012, 122, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melton, A.W. Implications of Short–Term Memory for a General Theory of Memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1963, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.C.; Shiffrin, R.M. The Control of Short–Term Memory. Sci. Am. 1971, 225, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, B.B. Short–Term Memory. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 1972, 5, 67–127. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A.D.; Thomson, N.; Buchanan, M. Word Length and the Structure of Short−Term Memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1975, 14, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, R.; Midian Kurland, D.; Goldberg, J. Operational efficiency and the growth of short–term memory span. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1982, 33, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, S. A temporal account of the limited processing capacity. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 24, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothos, E.M.; Joula, P. Linguistic structure and short−term memory. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 124, 138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, A.R.A.; Cowan, N.; Michael, F.; Bunting, M.F.; Therriaulta, D.J.; Minkoff, S.R.B. A latent variable analysis of working memory capacity, short−term memory capacity, processing speed, and general fluid intelligence. Intelligence 2002, 30, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonides, J.; Lewis, R.L.; Nee, D.E.; Lustig, C.A.; Berman, M.G.; Moore, K.S. The Mind and Brain of Short–Term Memory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 69, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, M.C. Conceptual short–term memory in perception and thought. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Macken, B. Questioning short−term memory and its measurements: Why digit span measures long−term associative learning. Cognition 2015, 144, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekaf, M.; Cowan, N.; Mathy, F. Chunk formation in immediate memory and how it relates to data compression. Cognition 2016, 155, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, D. Short–Term Memory and Long–Term Memory Are Still Different. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdt, G.V.; Mosquera, C.; Napoles, G. A review on the long short–term memory model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2020, 53, 5929–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Sarkar, A.; Hossain, M.; Ahmed, M.; Ferdous, A. Prediction of Attention and Short–Term Memory Loss by EEG Workload Estimation. J. Biosci. Med. 2023, 11, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Readability across Time and Languages: The Case of Matthew’s Gospel Translations. AppliedMath 2023, 3, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Formulas, 9th ed.; Dover publications: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

| Paragraphs | Words | Periods (Sentences) | Commas | Semicolons | Colons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian | 1 | 682 | 9 | 103 | 9 | 5 |

| English | 5 | 701 | 23 | 58 + 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Paragraphs | Words per Paragraph | Characters | Characters per Word | Words | Words per Sentence | Sentences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian | 2732 | 82.1 | 1,036,560 | 4.62 | 224,234 | 21.1 | 10,627 |

| Italian–E | 2732 | 82.1 | 1,036,560 | 4.62 | 224,234 | 15.3 | 14,647 |

| English | 3029 | 77.5 | 1,022,239 | 4.36 | 234,646 | 16.0 | 14,676 |

| English–I | 3029 | 77.5 | 1,022,239 | 4.36 | 234,646 | 30.6 | 7672 |

| Periods | Question Marks | Exclamation Marks | Commas | Semicolons | Colons | Interpunctions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian | 7795 | 1335 | 1497 | 26,316 | 4020 | 2633 | 43,596 |

| English | 11,692 | 1558 | 1426 | 20,003 | 263 | 540 | 35,482 |

| Linguistic Variable | Correlation Coefficient | Slope |

|---|---|---|

| Characters | 0.9973 | 0.9861 |

| Paragraphs | 0.9809 | 1.0897 |

| Words | 0.9967 | 1.0470 |

| Sentences | 0.9771 | 1.3704 |

| Sentences (Italian–E) | 0.9868 | 1.0047 |

| Question Marks | 0.9820 | 1.1581 |

| Exclamation Marks | 0.9237 | 0.9215 |

| Commas | 0.9477 | 0.7572 |

| Interpunctions | 0.9826 | 0.8143 |

| Italian | 4.62 0.12 | 22.7 6.24 | 5.18 0.41 | 4.34 1.03 |

| Italian–E | 4.62 0.12 | 16.01 3.57 | 5.18 0.41 | 3.07 0.50 |

| English | 4.36 0.15 | 16.82 4.56 | 6.66 0.56 | 2.50 0.43 |

| English–I | 4.36 0.15 | 30.30 –– | 6.66 0.56 | 4.53 –– |

| Text | S–Channel Sentences vs. Words | I–Channel Words vs. Interpunctions | WI–Channel Word Intervals vs. Sentences | C–Channel Characters vs. Words | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient | Slope | Correlation Coefficient | Slope | Correlation Coefficient | Slope | Correlation Coefficient | Slope | |

| Italian | 0.5978 | 0.0470 | 0.9357 | 5.1220 | 0.7863 | 3.9374 | 0.9926 | 4.6263 |

| Italian–E | 0.6980 | 0.0649 | 0.9357 | 5.1220 | 0.8573 | 2.9070 | 0.9926 | 4.6263 |

| English | 0.7106 | 0.0623 | 0.9322 | 6.5785 | 0.8932 | 2.3587 | 0.9884 | 4.3560 |

| S–Channel | I–Channel | WI–Channel | C–Channel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ita | Ita–M | Eng | Ita | Ita–M | Eng | Ita | Ita–M | Eng | Ita | Ita–M | Eng | |

| Italian | ∞ | 10.69 | 11.35 | ∞ | ∞ | 13.09 | ∞ | 8.11 | 2.50 | ∞ | ∞ | 23.08 |

| Italian–E | 7.48 | ∞ | 26.81 | ∞ | ∞ | 13.09 | 11.13 | ∞ | 12.04 | ∞ | ∞ | 23.08 |

| English | 8.36 | 27.22 | ∞ | 10.91 | 10.91 | ∞ | 7.56 | 14.06 | ∞ | 23.71 | 23.71 | ∞ |

| Variable | (dB) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characters | 22.62 | 182.97 |

| Paragraphs | 12.62 | 18.27 |

| Words | 20.23 | 105.49 |

| Sentences | 6.45 | 4.42 |

| Sentences (Italian–E) | 15.65 | 36.75 |

| Question Marks | 11.27 | 13.40 |

| Exclamation Marks | 8.17 | 6.57 |

| Commas | 9.07 | 8.07 |

| Interpunctions | 12.35 | 17.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matricciani, E. Translation Can Distort the Linguistic Parameters of Source Texts Written in Inflected Language: Multidimensional Mathematical Analysis of “The Betrothed”, a Translation in English of “I Promessi Sposi” by A. Manzoni. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010024

Matricciani E. Translation Can Distort the Linguistic Parameters of Source Texts Written in Inflected Language: Multidimensional Mathematical Analysis of “The Betrothed”, a Translation in English of “I Promessi Sposi” by A. Manzoni. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatricciani, Emilio. 2025. "Translation Can Distort the Linguistic Parameters of Source Texts Written in Inflected Language: Multidimensional Mathematical Analysis of “The Betrothed”, a Translation in English of “I Promessi Sposi” by A. Manzoni" AppliedMath 5, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010024

APA StyleMatricciani, E. (2025). Translation Can Distort the Linguistic Parameters of Source Texts Written in Inflected Language: Multidimensional Mathematical Analysis of “The Betrothed”, a Translation in English of “I Promessi Sposi” by A. Manzoni. AppliedMath, 5(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5010024