Abstract

Oxidative stress seems to be part of many deranged processes in the organism, affecting multiple degenerative conditions at a cellular and tissue level. Coumarins and flavonoids comprise two main categories of naturally derived compounds with multiple effects and applications. Our aim in this paper is the design of compounds with increased antioxidant activity with the conjugation of two moieties with highly antioxidant potency in the frame of one molecule. A series of novel derivatives, comprising fusion of 7-hydroxycoumarin (Umbelliferone) and Quercetin (flavonol) have been synthesized using classical organic chemistry methods. Additionally, one novel flavone derivative was prepared for comparison. The novel compounds were tested for their radical, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) scavenging, their reductive activity, and their labile metal chelating potency, as well as with in silico tools. All of them were more active, in most cases, than reference molecules Trolox and vitamin C. The most active compound 2 reached IC50 of 4.03 and 43.75 μM for ABTS and DPPH, respectively (up to three times lower than that of Trolox). Compound 1 was of equal to vitamin C activity in H2O2 scavenging, whilst compound 3 was up to 6.4 times more active than Trolox in NO scavenging. Since our designed compounds seem to exhibit high antioxidant potential, scavenging reactive nitrogen and oxygen species, which are accumulated and promote the progression of inflammatory conditions, and have reductive and metal chelating abilities, they can be considered as potential candidates for protection in cases of oxidative stress derived toxicity.

1. Introduction

In recent years, significant research efforts have been focused on the utilization of natural compounds, for the development of novel products and the implementation of large-scale industrial processes [1,2]. Among these compounds, flavonoids, a class of natural polyphenolic substances have garnered increasing attention. Their wide distribution in nature, combined with a broad spectrum of biological activities, makes them highly relevant across multiple scientific disciplines [3]. Flavonoids are secondary plant metabolites widely found in plants, fruits, and seeds, where they contribute to color, fragrance, and flavor. In plants, flavonoids serve various functions, including regulating cell growth and providing protection against biologic and oxidative stress [4].

Flavonoids are characterized by a benzo-γ-pyrone structure. They are synthesized through multiple biosynthetic pathways, including the phenylpropanoid, the shikimate, and the flavonoid pathway [5,6,7,8]. In humans, these compounds are associated with a wide range of health benefits due to their multi-functional properties. These include anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-aging, cardioprotective, neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, antidiabetic, antibacterial, antiparasitic, and antiviral effects [9,10,11]. Thus, accumulating evidence suggests that regular consumption of flavonoid-rich foods may contribute to the prevention of certain chronic diseases [10,11,12]. Among their various biological properties, flavonoids are particularly noted for their antioxidant potential and ability to scavenge free radicals. The antioxidant capacity of flavonoids varies across different classes and is largely influenced by the type, number and arrangement of functional groups attached to their core structure [13]. Specifically, hydroxyl groups on the catechol B-ring, as well as their placement on the pyran C-ring, play a crucial role in enhancing free radical scavenging activity [14]. These hydroxyl groups can donate electrons and hydrogen atoms to neutralize free radicals through resonance stabilization, resulting in the formation of a relatively stable flavonoid radical [5].

Flavonoids exhibit antioxidant activity through several mechanisms: (a) directly scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS); (b) preventing ROS formation, either by chelating trace elements—such as iron, in the case of quercetin, which exhibits both iron-chelating and iron-stabilizing properties—or by inhibiting enzymes involved in free radical generation including glutathione S-transferase, microsomal monooxygenase, mitochondrial succinoxidase, NADH oxidase, and xanthine oxidase; and (c) activation of endogenous antioxidant defenses, for example, by upregulating enzymes with radical-scavenging capabilities [13,15,16]. These mechanisms may act synergistically, allowing flavonoids to simultaneously neutralize radicals and modulate enzymatic activities [15]. Most flavonoids occur in glycosylated forms, and their antioxidant activity is influenced by the number and position of sugar moieties. Although aglycone forms typically possess higher antioxidant capacity, their bioavailability is generally lower [17].

Umbelliferone, a natural coumarin derivative, exhibits notable antioxidant activity by scavenging free radicals and inhibiting lipid peroxidation, directly and indirectly [18]. In addition, it exhibits anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer properties, contributing to its therapeutic potential. Several synthetic derivatives of umbelliferone have been developed, some of which show enhanced pharmacological activity and are also used as imaging tools [19,20].

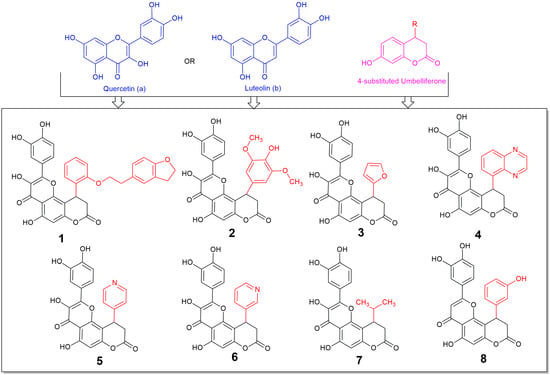

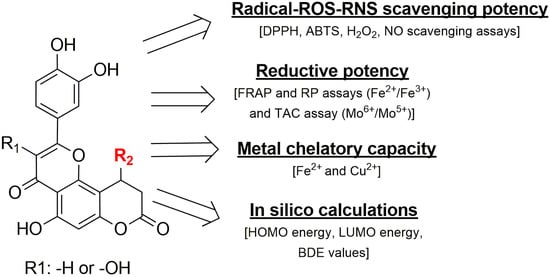

Based on the considerations described above, we present the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a series of polycyclic compounds combining flavonoids (quercetin or luteolin) and 7-hydroxycoumarin (umbelliferone) (Figure 1). This design was guided by efforts for the fusion of flavonoids and coumarins scaffolds as part of the multi-targeting strategy, aiming at minimizing polypharmacology related interactions and pharmacokinetic drawbacks that may derive from the increased polarity of the flavonoids and the poor solubility of the flavonoids and umbelliferone [21,22,23]. The antioxidant activity of the synthesized compounds was assessed using synthetic stable radicals including 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and ABTS (2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), as well as evaluating their NO and hydrogen peroxide scavenging abilities. Additionally, their reducing capacity toward ferric and molybdenum VI ions, as well as their ferrous and bivalent copper chelating potential was determined. Furthermore, in silico evaluation of their molecular behavior and antioxidant capacity, in order to bridge the results of the in vitro assays, was performed.

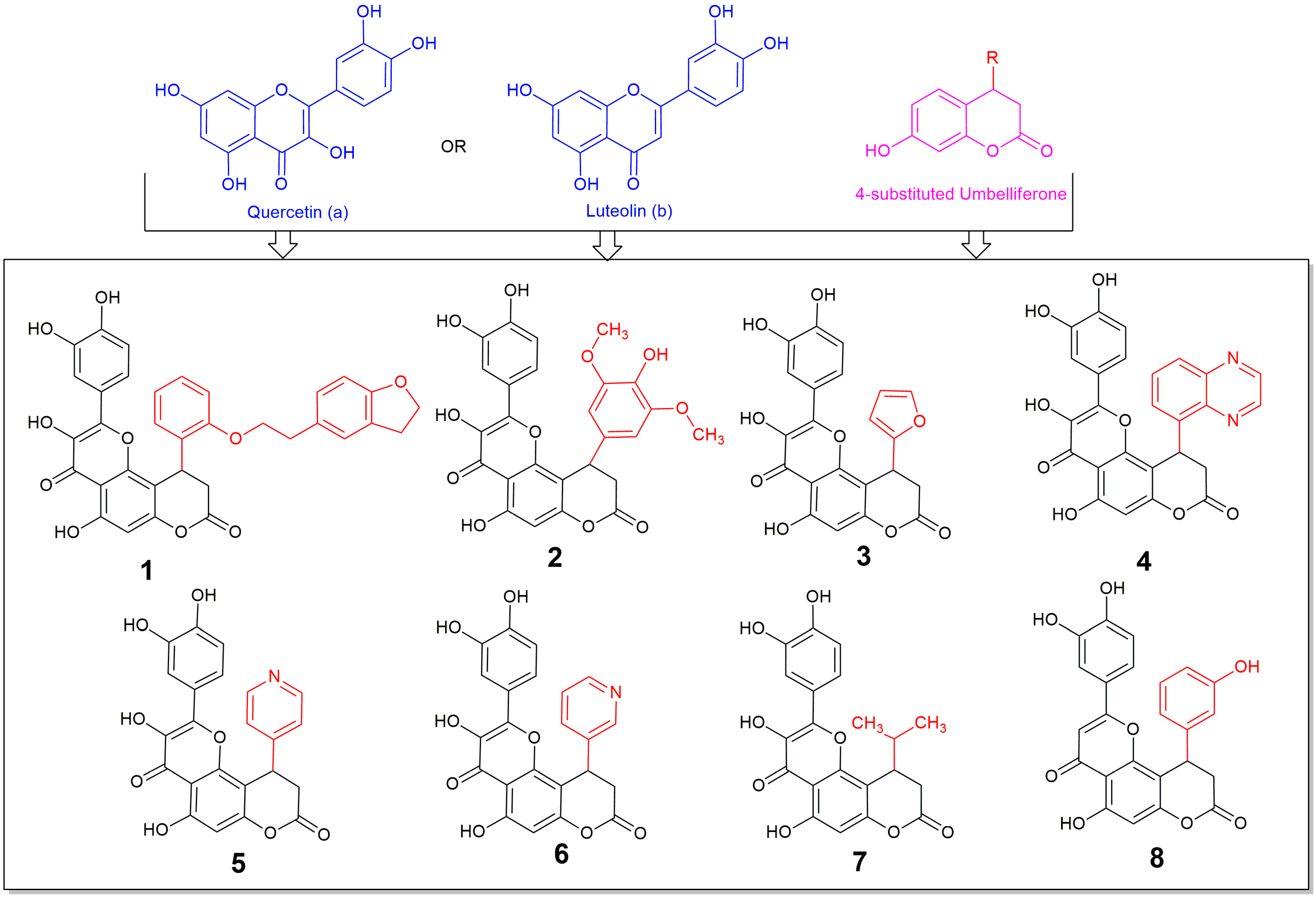

Figure 1.

Structures of the synthesized compounds 1–8, derivatives of (a) quercetin (compounds 1–7) or (b) luteolin (compound 8), and 4-substituted 7-hydroxycoumarin (umbelliferone).

To the best of our knowledge this is the first time in the literature that 4-substituted fused derivatives of umbelliferone with flavonols and flavones are synthesized and tested for their potential biological activity, although some efforts for synthesis of covalently bonded umbelliferone and flavone derivatives or 3-substituted umbelliferone-flavone derivatives have been made, with the first only being tested and showing anti-diabetic potency, accentuating the importance of such incorporations [24,25]. Thus, we expect that this report, which is commenting on the importance and the high activity of the fusion of flavonol or flavone molecular entities with the substituted umbelliferone, may add towards the widely explored area of flavonoids showing the importance of the substitution in these moieties [26].

2. Materials and Methods

All commercially available chemicals of the appropriate purity were purchased from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker AC 300 instrument (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) and 125 (13C) MHz spectrometer. All chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm), and signals are given as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; m, multiplet. Melting points (m.p.) were determined with a MEL-TEMPII (Laboratory Devices, Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA) apparatus. The microanalyses were performed on a Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN elemental analyzer (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC silica gel 60 F254 aluminum sheets, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) was used to monitor the evolution of the reactions and the spots were visualized under UV light.

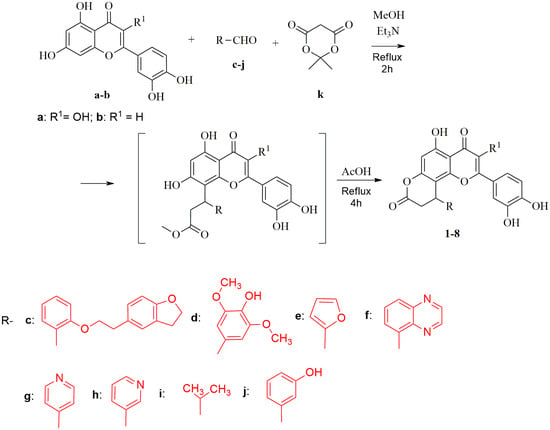

2.1. Synthesis of 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-5-hydroxy-10-phenyl-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano [2,3-f]Chromene-4,8-diones 1–8 (General Procedure)

The mixture of corresponding flavone a or b (0.002 mol), aldehyde (c–j, 0.003 mol), Meldrum’s acid k (0.58 g, 0.004 mol), and triethylamine (0.51 g, 0.005 mol) in MeOH (10 mL) was refluxed for 2 h. Then, reaction mixture was evaporated and the obtained residue was refluxed in AcOH (7 mL) for 4 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and left overnight. The precipitate that formed was collected by filtration, washed with AcOH (3 × 10 mL) and H2O (3 × 20 mL), and dried to afford pure target compounds 1–8.

10-(2-(2-(2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-5-yl)ethoxy)phenyl)-2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 1):

Yield 54%, yellow solid, m.p. 256–258 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.52 (s, 1H), 9.36 (s, 2H), 8.90 (s, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.12 (m, 3H), 7.11–6.97 (m, 2H), 6.80–6.66 (m, 3H), 6.61 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (s, 1H), 5.13 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 4.38–4.18 (m, 2H), 3.30–2.94 (m, 5H), 2.67 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.8, 159.9, 158.7, 157.0, 155.9, 151.8, 148.5, 148.1, 145.5, 136.9, 130.5, 129.0, 128.8, 127.7, 126.1, 122.1, 120.9, 119.8, 116.2, 115.9, 112.4, 108.9, 106.8, 103.5, 98.9, 71.2, 69.4, 34.9, 29.6. Anal. Calc. for C34H26O10: C, 68.68; H, 4.41. Found: C, 68.71; H, 4.38.

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-10-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 2):

Yield 68%, yellow solid, m.p. 269–271 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.55 (s, 1H), 9.50–9.40 (m, 2H), 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.07 (s, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.50 (m, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 6.43 (s, 2H), 4.81 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.66 (s, 6H), 3.35 (dd, J = 15.9, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 2.92 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.6, 167.2, 159.9, 156.2, 151.8, 148.7, 148.1, 145.7, 137.1, 135.3, 132.1, 122.1, 120.7, 116.1, 115.5, 106.9, 104.9, 104.3, 99.0, 56.3. Anal. Calc. for C26H20O11: C, 61.42; H, 3.96. Found: C, 61.52; H, 4.10.

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-10-(furan-2-yl)-3,5-dihydroxy-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 3):

Yield 51%, yellow solid, m.p. 247–249 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.56 (s, 1H), 9.34 (s, 2H), 9.07 (s, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.63–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.43 (s, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (s, 1H), 6.33–6.25 (m, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (dd, J = 16.1, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 3.13–3.02 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 190.2, 176.6, 166.7, 160.2, 156.1, 153.9, 151.8, 148.7, 145.7, 143.5, 137.1, 122.1, 120.6, 116.2, 115.6, 111.0, 106.4, 102.6, 99.2, 28.7. Anal. Calc. for C22H14O9: C, 62.56; H, 3.34; Found: C, 62.50; H 3.29.

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-10-(quinoxalin-5-yl)-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 4):

Yield 56%, yellow solid, m.p. 257–259 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.54 (s, 1H), 9.32 (s, 1H), 9.24 (s, 1H), 9.10–8.99 (m, 2H), 8.78 (s, 1H), 8.03–7.94 (m, 1H), 7.73–7.62 (m, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.04–6.95 (m, 1H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 6.52 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.54 (dd, J = 16.1, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.6, 166.6, 160.2, 157.2, 151.9, 148.5, 148.1, 146.6, 145.4, 143.2, 140.1, 139.8, 137.0, 130.6, 129.3, 127.9, 121.8, 119.7, 116.0, 115.6, 106.9, 103.8, 99.1, 36.2, 29.6. Anal. Calc. for C26H16N2O8: C, 64.47; H, 3.33; N, 5.78. Found: C, 64.58; H 3.30; N,5.65.

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-10-(pyridin-4-yl)-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 5):

Yield 54%, yellow solid, m.p. 241–243 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.60 (s, 1H), 9.44 (s, 1H), 9.33 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.43–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 4.98 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.45 (dd, J = 16.2, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.7, 166.5, 160.4, 156.5, 151.9, 150.8, 150.2, 148.6, 148.2, 145.6, 137.1, 122.3, 121.9, 120.3, 116.1, 115.6, 106.9, 102.9, 99.2, 35.8, 33.8. Anal. Calc. for C23H15NO8: C, 63.75; H, 3.49; N, 3.23. Found: C, 63.65; H 3.30; N, 3.30.

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-10-(pyridin-3-yl)-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 6):

Yield 62%, yellow solid, m.p. 253–255 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.58 (s, 1H), 9.38 (s, 1H), 9.30 (s, 1H), 9.01 (s, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.47–8.39 (m, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.46 (m, 1H), 7.44–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.33–7.23 (m, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.45 (dd, J = 16.1, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.10–2.98 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.7, 166.6, 160.3, 156.4, 153.2, 151.9, 149.2, 148.6, 148.2, 145.6, 137.1, 134.5, 124.5, 122.0, 120.3, 116.1, 115.6, 106.9, 103.4, 99.3, 36.5, 33.2, 21.52. Anal. Calc. for C23H15NO8: C, 63.75; H, 3.49; N, 3.23. Found: C, 63.68; H 3.25; N, 3.28.

2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-10-isopropyl-9,10-dihydro-4H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 7):

Yield 52%, yellow solid, m.p. 224–226 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.53 (s, 1H), 9.30 (s, 3H), 7.73 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.51 (m, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.40 (s, 1H), 3.51–3.41 (m, 1H), 2.98–2.90 (m, 2H), 2.00–1.88 (m, 1H), 1.00 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 0.93 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.8, 168.1, 159.6, 156.1, 152.2, 148.6, 148.1, 145.7, 136.9, 122.2, 120.5, 116.2, 115.5, 106.7, 104.9, 98.9, 35.3, 32.6, 30.9, 20.5, 19.0. Anal. Calc. for C21H18O8: C, 63.32; H, 4.55. Found: C, 63.29; H 4.47. 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5-hydroxy-10-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-9,10-dihydropyrano[2,3-f]chromene-4,8-dione (compound 8):

Yield 63%, yellow solid, m.p. 269–271 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.98 (s, 1H), 9.57 (s, 1H), 9.16–9.10 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.20 (m, 2H), 7.13–7.02 (m, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.70–6.50 (m, 5H), 4.84 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (dd, J = 16.0, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.03–2.90 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.6, 166.8, 164.9, 160.7, 158.3, 156.8, 153.2, 150.7, 146.3, 143.1, 130.6, 121.5, 119.7, 117.7, 116.5, 114.8, 114.1, 113.5, 107.6, 104.9, 103.9, 36.9, 34.5. Anal. Calc. for C24H16O8: C, 66.67; H, 3.73. Found: C, 66.71; H 3.80.

2.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Experiments

Spectrophotometric in vitro analyses were performed by recording the absorbance of each reaction mixture over time and at various concentrations of the compound, according to the specific requirements of each assay. Measurements were obtained using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer equipped with 10 mm wide poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) cuvettes. The antioxidant activity was assessed within the spectral range of 240–734 nm, which includes wavelengths at which some of the tested compounds exhibit intrinsic absorption. To correct this, reference solutions containing only the individual compounds were used as blanks, and their absorbance values were subtracted from the experimentally recorded values. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and results are reported as mean values. Measurement variability consistently remained within ±10% of the mean.

2.2.1. Reactive Species Scavenging Assays

ABTS+ Radical Scavenging

The 2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging assay is based on the reduction in the colored ABTS·+ radical (versatile, soluble in both aqueous and organic solvents, allowing testing of both hydrophilic, lipophilic and amphiphilic antioxidants, less sterically hindered), generated from a 7 mM ABTS stock solution mixed in equal volumes with a 2.45 mM potassium persulfate solution. For each measurement, the resulting ABTS·+ solution was diluted to an absorbance of approximately 0.7 at 734 nm and was subsequently mixed with the test sample, which contained the compounds at final concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 200 μM (dissolved in ethanol). After 30 min of incubation, the absorbance at 734 nm was recorded. The antioxidant activity at each concentration was expressed as the percentage of radical inhibition relative to the control, calculated using the equation: ABTS·+ scavenging activity (%) = [(Ac − As)/Ac] × 100, where Ac represents the absorbance of the control and As is the absorbance in the presence of the compound [27,28].

DPPH Radical Scavenging

The stable DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, a lipid-soluble rigid structure) radical scavenging assay evaluates a compound’s ability to donate a hydrogen atom to the nitrogen-centered DPPH· radical resulting in a visible color change from deep violet to the yellow reduced form. A 0.4 mM DPPH· stock solution was prepared in ethanol, and the test compounds diluted in ethanol to final concentrations ranging from 200 to 5 μM. Equal volumes of the DPPH· working solution and the diluted test solutions were then mixed, resulting in a final DPPH· concentration of 200 μM in the reaction mixtures.

After a 30 min incubation period at room temperature in the dark, absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Ethanol was used as the blank. The scavenging activity of each compound at tested concentrations was expressed as the percentage of DPPH· inhibition, calculated using the equation: DPPH· scavenging activity:

DPPH· scavenging activity (%) = [(A_control − A_sample)/A_control] × 100, where A_control is the absorbance of the DPPH· solution without the test compound, and A_sample is the absorbance in the presence of each compound [29].

H2O2 Interaction Assay

The hydrogen peroxide [belonging to reactive oxygen species (ROS), non-radical] scavenging activity (HPSA) of the tested compounds was evaluated according to an established protocol [30]. A 40 mM hydrogen peroxide solution in 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and stock solutions of the tested compounds (4 mM in ethanol) were diluted with ethanol to obtain working concentrations ranging from 25 to 250 μM. The assay was performed by mixing each compound solution with the hydrogen peroxide solution and phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7.4). Reaction mixtures were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 15 min. Blank samples containing the compound and buffer (without H2O2) were used for the background correction, while a control solution containing only hydrogen peroxide and phosphate buffer (without the test compound) served as the assay blank. Absorbance was recorded at 230 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard antioxidant for comparison. The percentage of hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity was calculated using the equation:

HPSA (%) = {[A_blank − (A_sample − A_blank sample)]/A_blank} × 100, where A_blank is the absorbance of the H2O2 control, A_sample is the absorbance in the presence of each test compound, and A_blank sample is the absorbance of the compound alone.

Nitrogen Monoxide Scavenging Experiment

The nitrogen monoxide [NO, radical belonging to reactive nitrogen species (RNS)] scavenging activity of the tested compounds was evaluated using a modified protocol based on the NO generation by sodium nitroprusside and subsequent nitrite detection via the Griess reaction, as previously described [27,31]. The Griess reagent was freshly prepared by dissolving 1 g of sulfanilamide, 2 g of phosphoric acid (H3PO4), and 100 mg of N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 100 mL of deionized water. A 10 mM sodium nitroprusside solution [in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4] was prepared, and stock solutions of the test compounds in DMSO were obtained. For each experiment, reaction mixtures were prepared by combining sodium nitroprusside solution, PBS, and the test compound solution. Control samples contained DMSO instead of the compound. The mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 150 min, and subsequently, each incubated solution was treated with Griess reagent and left to react for 30 min in the dark. Absorbance was then measured at 546 nm. The percentage of nitric oxide radical scavenging was calculated using the following equation:

NO scavenging (%) = [(A_control − A_sample)/A_control] × 100, where A_control is the absorbance of the control sample without compound, and A_sample is the absorbance of the reaction mixture containing the test compound.

2.2.2. Electron Transfer Assays

Ferric Reducing Assays

- Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Potential (FRAP)

The ferric reducing ability of the tested compounds was evaluated using the FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) assay, which measures the ability of the antioxidants to reduce ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+) ions in an acidic environment. The resulting Fe2+ forms a blue-colored complex with 2,3,5-triphenyl-1,3,4-triaza-2-azoniacyclopenta-1,4-diene chloride (TPTZ), which can be quantified spectrophotometrically. TPTZ solution (10 mM) and 20 mM FeCl3 solution were prepared in deionized water. The FRAP working reagent was freshly prepared by mixing 12.5 mL of acetate buffer, 12.5 mL of methanol, 2.5 mL of the TPTZ solution, and 2.5 mL of the FeCl3 solution. The acetate buffer was prepared by dissolving 1.87 g of sodium acetate (CH3COONa) and 16 mL of glacial acetic acid in deionized water. For each assay, FRAP working reagent, a methanol/water mixture (1:1, v/v), and the test sample were mixed. After an 8 min incubation at room temperature, absorbance was recorded at 593 nm against a blank sample. Trolox was used as reference antioxidant and was tested under identical conditions.

The reducing capacity of each compound was expressed in relation to the reference compound at the same concentration using the equation:

where A_sample is the absorbance of the test compound and A_reference is the absorbance of the standard antioxidant (Trolox or ascorbic acid) at the same concentration [28,32].

Ferric Reducing Power (% of control) = (A_sample/A_reference) × 100,

- Reducing Power Assay (RP)

The ferric reducing activity of the tested compounds was also evaluated using a colorimetric method based on Prussian blue formation, which occurs when ferric ions (Fe3+), generated by the reduction of potassium ferricyanide react with ferrocyanide in the presence of FeCl3. For each assay, the test compound [in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)], phosphate buffer (pH 6.6), and potassium ferricyanide (1% w/v) solution were combined in glass test tubes. The mixtures were incubated at 50 °C for 20 min with gentle stirring. Then, TCA solution (10% w/v) was added to each tube, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for another 30 min. After incubation, deionized water and FeCl3 (0.1% w/v) solution were added and the resulting solutions were transferred into a cuvette, and then the absorbance was recorded at 700 nm [33]. A blank solution, containing all reagents, except for the test compound, was used for baseline correction. The reducing ability of the compounds was assessed compared to standard antioxidant (Trolox) tested under identical conditions. The ferric reducing power was expressed as a percentage relative to the reference compound using the following equation:

Ferric Reducing Power (% of control) = (A_sample/A_reference) × 100, where A_sample is the absorbance of the test compound and A_reference is the absorbance of the standard antioxidant at the same concentration.

Phosphomolybdate Assay

The Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) of the compounds was determined based on their ability to reduce molybdenum (VI) [Mo(VI)] to molybdenum (V) [Mo(V)] under acidic conditions, resulting in the formation of a green-colored phosphomolybdenum (V) complex. The TAC reagent consisting of 0.6 M H2SO4, 28 mM Na3PO4 and 4 mM ammonium molybdate [(NH4)6Mo7O24], and stock solutions of the test compounds in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were prepared. For each assay, the TAC reagent and the test compound (or DMSO for the blank) were combined in glass test tubes and incubated in a water bath at 90 °C for 90 min. After incubation, the samples were cooled to room temperature, and their absorbance was measured at 695 nm against the blank [34,35]. Trolox was included as a reference antioxidant under identical experimental conditions. The antioxidant capacity of each compound was expressed as a percentage of the activity of the reference antioxidant, using the following formula:

Molybdenum Reducing Power (% of control) = (A_sample/A_reference) × 100, where A_sample is the absorbance of the compound and A_reference is the absorbance of the standard antioxidant at the same concentration.

2.2.3. Metal Chelating Assays

Ferrous Chelation Assay

The ability of phenolic compounds to chelate Fe2+ was evaluated using a method based on their capacity to bind iron (II) [36]. The chelating activity of the compounds is determined indirectly by measuring the remaining free Fe2+ ions which form colored complex with the ferrozine. Initially solutions of FeSO4-7H2O (2 mΜ), ferrozine (5 mM) and test compounds (2 mM) in methanol were prepared. The Fe2+ solution was mixed with the compound solution and incubated for 3 min at 25 °C. Afterwards the ferrozine solution was added and the mixture was stirred for an additional 10 min at room temperature. The absorbance of the resulting solution was recorded at 562 nm. EDTA, a well-known metal-chelating agent, was used as a reference. The percentage of iron chelation capacity is deduced by:

Iron Chelation (%) = (Acontrol − Asample/Acontrol) × 100, where A0 and As are the blank (methanol) and the sample absorbance, respectively.

Copper Chelation Assay

The ability of phenolic compounds to chelate the oxidized Cu2+ was determined by the remaining copper ions available to form a complex with murexide [36,37]. This method is a complementary assay to the iron-chelating test. A hexamine buffer solution (10 mM hexamine) was prepared and solutions of the phenolic compounds and EDTA (used as a reference metal-chelating agent) were prepared in the same hexamine buffer, at a final concentration of 2 mM. For each measurement, the test solution was mixed with the copper (II) solution, followed by the addition of murexide solution (1 mM in deionized water). After incubation for 3 min at room temperature (25 °C), the absorbance was recorded at 485 nm and 520 nm, corresponding to the copper (II)–murexide complex and free murexide, respectively. The absorbance ratio A485/A520 was used as an indicator of the amount of free copper (II) ions remaining in the solution.

where

Copper chelation capacity (%) = [(A485/A520)0 − (A485/A520)s]/(A485/A520)0 × 100

- (A485/A520)0 is the absorbance ratio of the blank (no chelator),

- (A485/A520)s is the absorbance ratio in the presence of the sample (chelator).

2.3. In Silico Calculations

The theoretical evaluation of the antioxidant potential of polyphenols relies on computational methods capable of predicting their molecular behavior. In this study, we explored the impact of molecular structure on the frontier molecular orbitals and the heterolytic breaking of the O-H bond, being directly linked to the antioxidant activity of the compounds. Quantum chemical parameters, particularly the energies of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO), were calculated for all compounds, and Bond Dissociation Enthalpy (BDE) values for phenolic hydroxyl groups were determined. These calculations were intended to interpret and support the findings of the in vitro antioxidant assays in relation to structural characteristics. The BDE values assess the bond strength of hydroxyl groups, an important factor in the hydrogen-donating abilities and the radical scavenging efficiency of the derivatives. It also assesses the ease with which this bond cleavage between oxygen and hydrogen occurs, and the subsequent delocalization of the unpaired electron over the phenoxy radical. Because of the asymmetric carbon atom in the position 10 of the pyrano-chromone, for all compounds 1–8 the calculations were performed for both R and S enantiomers.

According to the literature, the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) mechanism, involves the homolytic cleavage of the O–H bond resulting in the release of a hydrogen atom (a proton and an electron), and is considered a primary pathway for the antioxidant action of polyphenols, mechanism which was investigated at the present work for compounds 1–8. The calculation of O-H BDE was made using the equation BDE = H(ArO•) + H(H•) − H(ArOH) [38,39,40,41,42].

All computations were carried out in vacuum using the Spartan 24 version 1.3.1 (Wavefunction, CA, USA), employing the B3LYP functional with the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set [38,43,44].

Because the compounds 1–8 possess multiple phenolic groups that can undergo radicalization and two enantiomers are possible for each compound, the BDEs were calculated individually for each phenolic O–H bond upon radical formation in both enantiomers. The calculations were restricted to monoradical species, since considering all possible multi-radical (di-, tri-, etc.) configurations multiplied by two, by taking into account the two possible enantiomers, would result in an impractically large number of possible combinations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Synthesis

Polycyclic compounds 1–8 were prepared from flavones quercetin (a) or luteolin (b) by the two step reaction presented below (Scheme 1). In the considered case the formed methyl esters intermediates, without isolation, were cyclized into the final products 1–8. The conclusive heterocyclization was performed at reflux in acetic acid leading to dihydropyranone final compounds in 51–68% yields.

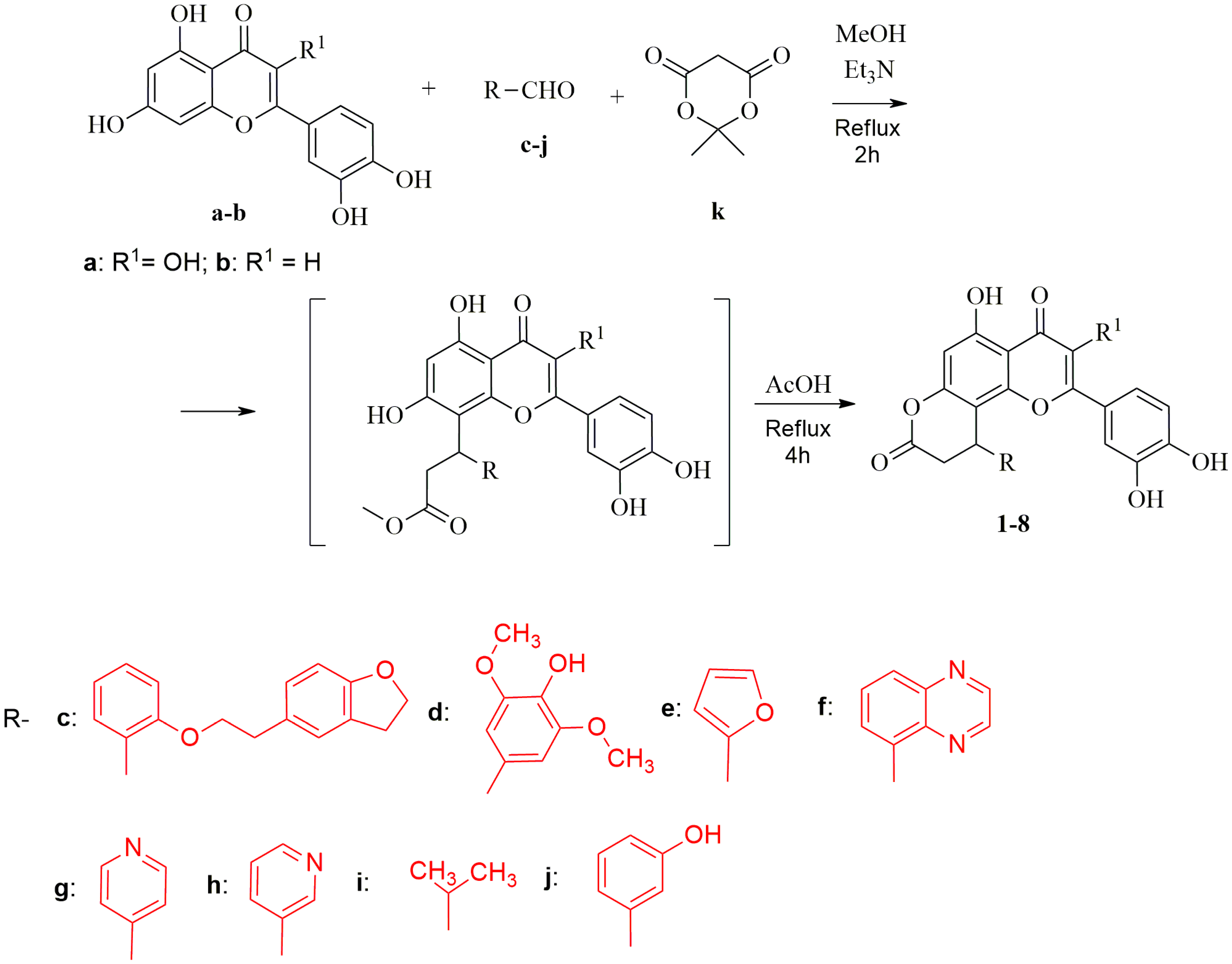

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1–8.

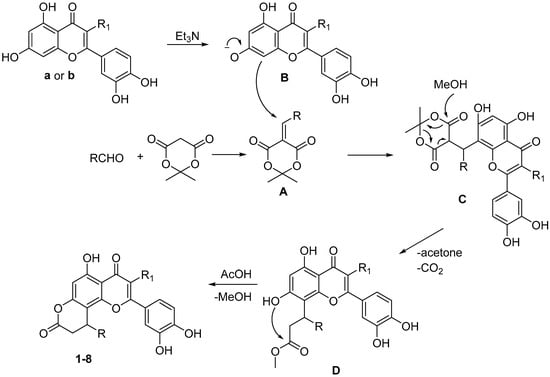

The plausible reaction mechanism is presented in Scheme 2. At first, condensation of aldehyde c–j with Meldrum’s acid leads to the formation of compound A. Further, adduct C is produced by the interaction of chromone anion B with intermediate A. Next cleavage of 1,3-dioxane fragment under action of methanol leads to methyl ester D. Final acid catalyzed intramolecular cyclization accompanied by the release of methanol molecule results in target compounds 1–8.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of formation of products 1–8.

3.2. Antioxidant Experiments

3.2.1. Reactive Species Scavenging Assays

ABTS·+ Radical Scavenging

The synthesized molecules were tested for their ability to reduce ABTS·+ radical (IC50 values after 30min of incubation are shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of compounds 1–8 and Trolox towards ABTS·+ radical.

Most of the derivatives showed similar or even more than threefold increased activity compared to the reference well-known and applied antioxidant Trolox, with the exception of compounds 4 and 6, with the nitrogen containing substituents (quinoxaline and 3-pyridine, respectively). In contrast to those, compound 5 was among the most active, accentuating the potency of the number of substitution in the radical scavenging potential. Between the catechol moiety and the variable substituent from the position 10 a complex interaction can influence the antioxidant activity, for example, π-π stacking between the aromatic rings, intramolecular hydrogen bonding or various steric clashes. Additionally, it seems that the phenolic substituents with electron donating groups contribute to the improvement of the activity, as the potent syringol (2,6-dimethoxyphenol) substituted compound 2 showed. On the other hand, the ortho substitution also provides improved activity as is the case with compound 1 and 3, whilst the meta substitution of the hydroxyl group at the phenyl ring of compound 8 may decrease its potency. However, for compound 8 (the luteolin derivative) the lack of one hydroxyl group is another factor that should be taken into account, although there have not been established rules for the effect of the enol functional group in quercetin and luteolin on antioxidant activity (however, quercetin has been shown to be more active than luteolin in DPPH and ABTS+ radical scavenging, but due to the application of one luteolin derivative safe conclusions cannot be deduced) [45].

These results are rather encouraging, and are in accordance with the activity of quercetin in this experiment, which shows more than 1.5 higher activity than Trolox (luteolin shows slightly lower potency with IC50 1.28 times higher than Trolox), but significantly lower than half of our tested compounds, with umbelliferone exhibiting lower activity (less than 60% inhibition) at concentration of 50 μg/mL (more than 300 µM) [46,47,48].

DPPH Radical Scavenging

Moreover, the compounds were evaluated as potent DPPH radical scavengers and their efficacy is depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reducing potency of compounds 1–8 and Trolox against DPPH radical.

The radical scavenging activity in this assay, similarly to the ABTS·+ radical scavenging assay manner, is depicted via the decolorization of the radical (yellow reduced DPPH compound formation). All the compounds, with the exception of compounds 7 and 8 show similar activity as in the ABTS radical assay; however, compounds 4 and 6 were inactive and not of low potency. This effect may derive from the electron withdrawing effect of quinoxaline and 3-pyridine moieties and their rigid formation that may not allow the close approach of the DPPH radical in order to receive an electron. This effect is also reinforced by the DPPH radical formation, that is more rigid, lipid soluble and sterically hindered than ABTS·+ radical. Thus, the lower steric hindrance, total polar surface area (TPSA), and high lipophilicity (ClogP) (Table 3) of the isopropyl or the phenol moiety may explain the activity of compounds 7 and 8—molecules that were less active at the previous assay. These results show the scavenging potential of radicals with various characteristics (concerning the stereochemical and lipophilic characteristics).

Table 3.

Calculated physicochemical properties of the synthesized compounds: Molecular Weight MW), total polar surface area (TPSA), number of H donors and acceptors, lipophilicity (clogP) and violations of “Lipinsky’s rule of 5”.

H2O2 Interaction Assay

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) belongs to the group of reactive oxygen species (ROS, non-radical) and can generate more dangerous free radicals, such as hydroxyl radical through the Fenton reaction. These species contribute to oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and cellular degeneration [49,50,51]. H2O2 is a naturally occurring ROS produced during normal cell metabolism, either as a reduction product of superoxide anions (O2•−), or through the activity of oxidases such as monoamino oxidases (MAOs) and other flavin-containing oxidases. However, its important role as a signaling molecule, a second messenger, and activator of transcription factors should not be overlooked [52,53].

The antioxidant capacity of the compounds was evaluated based on their ability to interact with H2O2, and the results are shown in Table 4. Due to the extended coordination in the compounds and their low solubility into the medium (due to high lipophilicity), some of them could only be tested at 100 µM, the highest achievable concentration, thus the IC50 of these compounds could not be deduced and their activity in this experiment should be analyzed with caution.

Table 4.

Interaction of compounds 1–8 and ascorbic acid with H2O2.

All the compounds demonstrated hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity. Compounds 1, 2, 7 and 8 showed potency equal or comparable to ascorbic acid, a strong antioxidant used as reference in this assay, whereas compounds 3–6 exhibited lower activity, with compound 4 being approximately two-fold less active. The results of compounds 4 and 6 are consistent with the previous findings obtained using synthetic radicals (ABTS and DPPH); however, this trend was not observed for compounds 3 and 5 (with the solubility issues making the analysis more difficult). The activity of our compounds is at least partially attributable to the behavior of quercetin in this assay, which has shown an IC50 of approximately 229 µM, while three (compounds 1, 7 and possibly compound 2) of the tested compounds displayed significantly higher potency [54].

Nitrogen Monoxide Scavenging Experiment

Table synthesized compounds were examined for their ability to interact with NO and their activity is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Interaction of compounds 1–8 and Trolox with NO.

All compounds displayed strong NO radical scavenging activity with the IC50 ranging from 6.4 to 0.85 fold compared to Trolox. The highest activity was observed for compounds 2 and 3, which is consistent—particularly in the case of compound 2 with the results from the previous assays.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous signaling molecule implicated in inflammation, particularly when produced by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in activated macrophages [55]. NO regulates vascular tone, leukocyte recruitment, and cytokine release. However, excessive NO can contribute directly and indirectly to oxidative stress and tissue injury, further amplifying inflammatory responses. Interestingly, NO also plays an ambivalent role in inflammation by mediating the expression of antioxidant enzymes, which may promote the release of inflammation [55,56,57]. In addition to scavenging nitrogen monoxide activity, flavonoids have been shown to inhibit NO consumption by the reactive radicals, such as O2−., generated by systems like xanthine oxidases, thereby improving vasodilation and enhancing their protective effects at both cellular and tissue protective level [58,59,60,61]. Quercetin, in the presence of NO and O2•−, appears to preferentially scavenge superoxide increasing the bioactivity of NO [58]. Thus, compounds 1–8 could, apart from the direct NO radicals scavenging, potentially reduce inflammatory signaling and modulate the processes that consume NO preventing the formation of toxic intermediates—such as peroxynitrite. These intermediates can generate other reactive species (ROS, RNS, RSS, RCS), which contribute to further oxidative damage [62,63]. Additionally, compounds 1–8 could decrease the consumption rate of NO, by scavenging other reactive species (as the previous reactive species scavenging assays showed), enhancing their potential to mitigate inflammation and oxidative stress.

3.2.2. Electron Transfer Assays

Ferric Reducing Assays

Two experiments were carried out to evaluate the ability of the compounds to reduce ferric cations: one assessing the reduction in FeCl3 (FRAP assay) and the other examining the conversion of ferricyanide to ferrocyanide (RP assay). The results, expressed as a percent activity of Trolox are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ferric ions reducing capacity of compounds 1–8, expressed as % Trolox activity.

All the compounds, in both experiments, with the exception of compounds 4 and 6 at the FRAP assay, displayed remarkable reducing ability with several of them showing activities multiple times higher than that of Trolox. Compounds 2 and 3, which exhibited the higher ABTS and DPPH scavenging activities, were also the most potent reducing agents in both the FRAP and RP assays, followed by compound 7 that also showed high activity in both the assays.

All compounds showed greater potency in the RP assay, where Fe3+ is complexed with cyanides, demonstrating an enhanced ability to reduce complexed ferric ions compared with FeCl3. This shift in activity may also be influenced by the lower pH (3.6) of the FRAP assay, which may hinder the release of hydrogen atoms from the compounds. The results were consistent between the two tested doses in each experiment. However, for compounds 1–4 in the RP assay, a greater increase in activity was observed at the lower dose, potentially indicating higher intrinsic activity and the preservation of the reducing capacity of the compounds, even at reduced concentrations, compared to Trolox.

Phosphomolybdate Assay

In addition to the ferric cation assays, the synthesized molecules were evaluated for their reducing ability towards another cation, the phosphomolybdate cation. The results, expressed as the percentage of Trolox activity, are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Phosphomolybdate reducing capacity of compounds 1–8, expressed as % Trolox activity.

A similar order of potency between the compounds, as in the RP assay, was recorded, although at lower percentage. This may be due to the lower pH of the medium, as was observed in the FRAP assay, while Mo6+ exists in the salt form rather than being complexed. Compound 4 again exhibited the lowest reducing capacity, followed by compound 8 which also demonstrated mediocre activity in both experiments. However, the activity of the compounds was similar to, or up to 1.6 times higher than, that of Trolox. With the exception of compounds 2, 4, and 7, their activity in the TAC (total antioxidant capacity) assay compared to the reference compound increased as their concentration decreased.

3.2.3. Metal Chelation Assays

Finally, all the synthesized compounds were evaluated for their Fe (II) chelation capacity, through their competition with ortho-phenanthroline, and the results are shown in Table 8. Ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) was used as positive reference.

Table 8.

Fe (II) chelation activity of compounds 1–8 and EDTA.

All compounds exhibited approximately 50% inhibition, showing chelating activity comparable to EDTA. The most likely sites of metal chelation are the catechol moieties and the adjacent hydroxyl and ketone groups, as flavonoids structurally similar to those studied here, such as quercetin and luteolin, are known to chelate iron (Fe2+ and Fe3+) and copper (Cu1+ and Cu2+), at 2:1 and 1:1 ligand ratio in a pH dependent manner [64,65,66]. Part of the observed activity may also derive from the nitrogen containing substituents, as seen in compounds 4 and 5 which displayed the highest activity, and may benefit from the intrinsic antioxidant properties of the pyridine scaffold [67]. Moreover, the electron donating effect of the para substitution of the pyridine may render the nitrogen atom a more potent electron donor for the metal chelation and the complex formation, whilst the meta substitution do not seem to offer these properties, an effect that may explain the lower potency of compound 6 (however, their close range of activity limits the deduction of safe conclusions, as is the case with the luteolin derivative compound 8). Additionally, the copper-chelating capacity of compounds 7 and 8 (61.5% and 56.8%, respectively) were nearly equivalent to their ferrous-chelation abilities, accentuating their potential to inhibit the redox cycling of free labile metals.

Thus, our compounds which likely share the same metal chelating sites proposed for quercetin (three proposed positions [68,69]), appear to display strong Fe2+ chelating potency. This activity may contribute to reducing the progression of the Fenton reaction, as previously demonstrated for quercetin and its metabolites [70]. In addition, by virtue of their chelating ability, compounds such as those described herein may also scavenge other metal ions capable of inducing harmful effects, such as Al3+, although this remains to be experimentally confirmed [68].

3.3. In Silico Calculations

The electronic properties of the compounds 1–8 were evaluated by comparing the frontier molecular orbital energies (HOMO and LUMO), HOMO–LUMO energy gaps, and dipole moments for their R and S enantiomers (Table 9). These descriptors provide valuable insight into molecular reactivity, electronic stability, and polarity, which are essential parameters for understanding structure–property relationships.

Table 9.

Frontier molecular levels (eV) and the dipole momentum of the enantiomers of the compounds 1–8.

It is worth mentioning that the intramolecular hydrogen bonding occurs in the present compounds 1–8, which influences the molecular properties of the compounds. In all the compounds the OH groups from the catechol ring grafted on the carbon 2 of the pyranochromene main core, are involved in hydrogen bonding inside the catechol group. Dependent on the substituent from the position 10 and its orientation due to the two possible enantiomers, the acceptor OH group from the position 3 of the catechol may act as hydrogen bond donor to the electronegative atoms (nitrogen or phenol oxygen) from the substituent of the position 10 of compounds 2, 4, 5, 6 and 8. In compounds 1 and 3, with oxygen atoms in the substituent from position 10 of the pyranochromene main core, no internal hydrogen bonding occurs with the respective oxygen atoms due to the high distance between those and the catechol group. The depictions for both the conformations of the compounds 1–8 and the intramolecular hydrogen bonding are depicted in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S8).

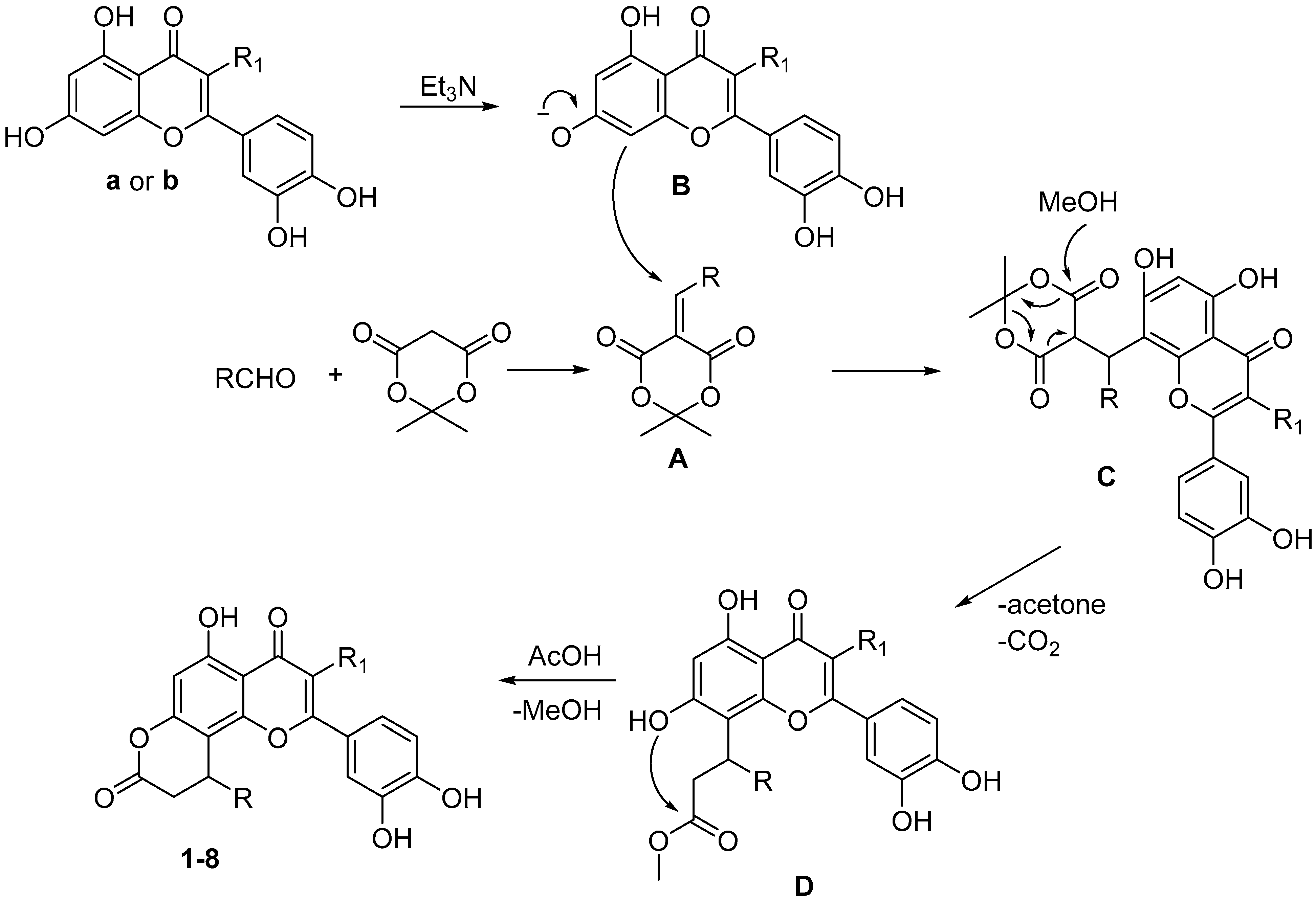

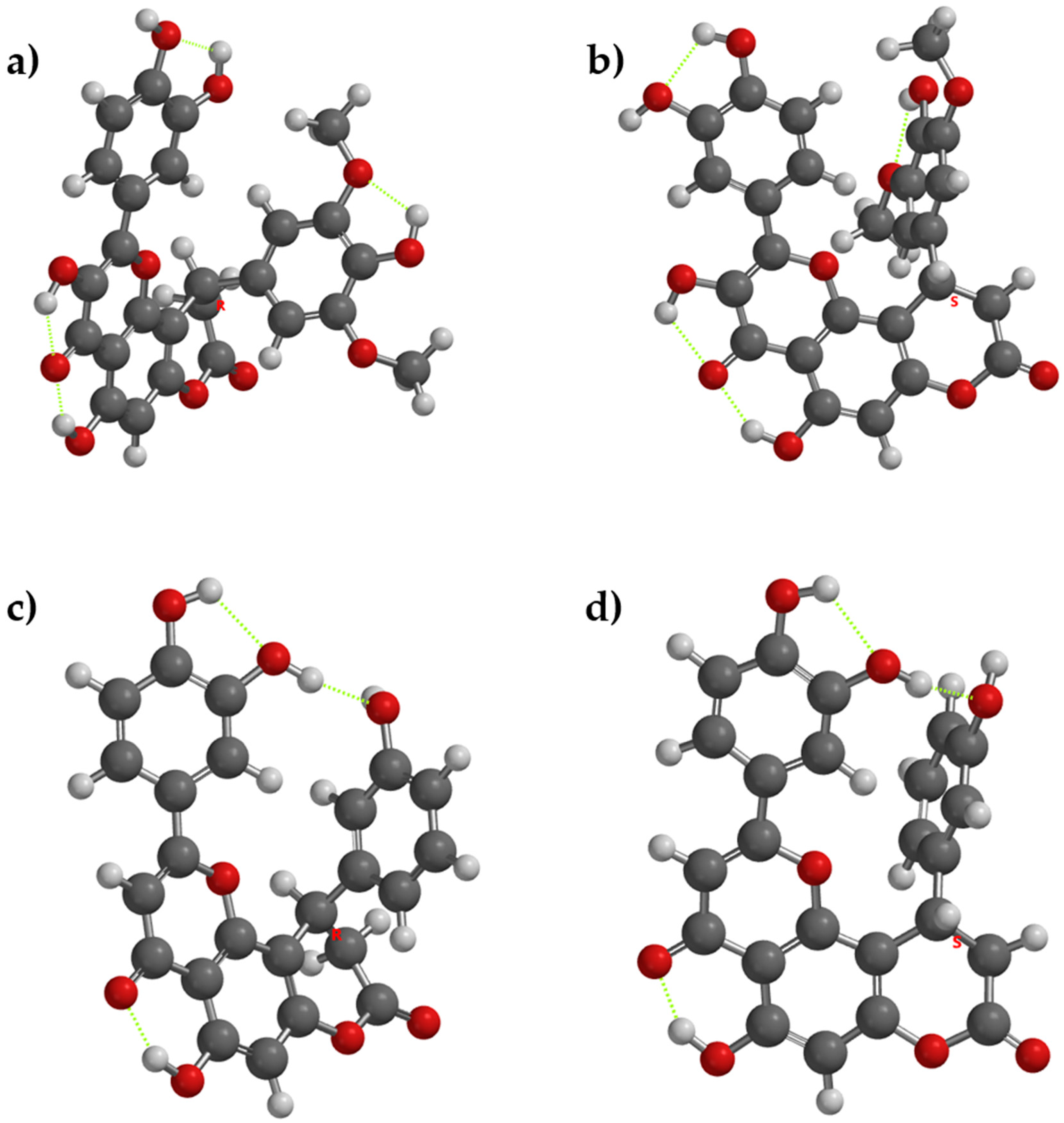

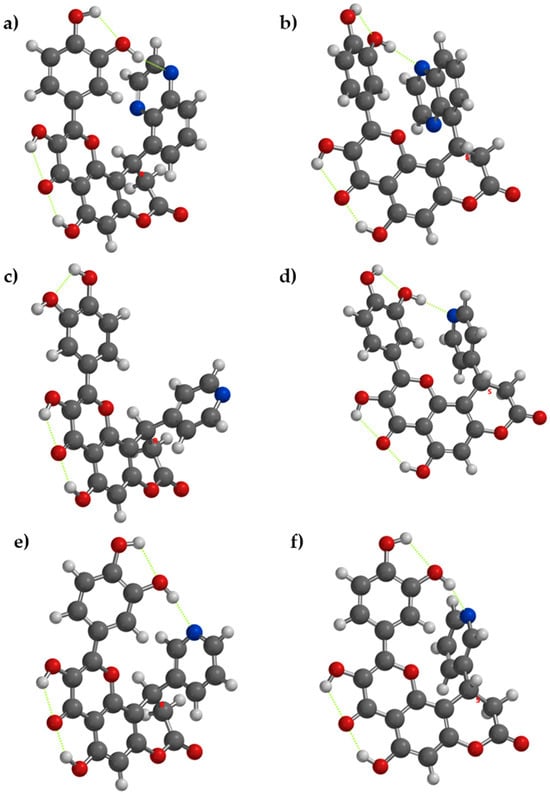

In compounds with nitrogen containing rings (compounds 4, 5, 6) the phenomenon occurs dependent on the enantiomer of the compound. In compounds 4[R], 4[S], 5[S], 6[R] and 6[S], it occurs, while in 5[R] the acceptor nitrogen atom is too far from the donor OH group from the catechol moiety. The respective intramolecular hydrogen bonding will reduce the disponibility of the donor OH groups to release hydrogen atoms, reducing their antioxidant activity, while the lack of internal hydrogen bonding may ease the hydrogen atom release, as in 5[R] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The lowest energy conformation for enantiomers of compounds 4, 5, and 6 and the internal hydrogen bonding (with green dots). (a) Compound 4[R], (b) compound 4[S], (c) compound 5[R], (d) compound 5[S], (e) compound 6[R], and (f) compound 6[S].

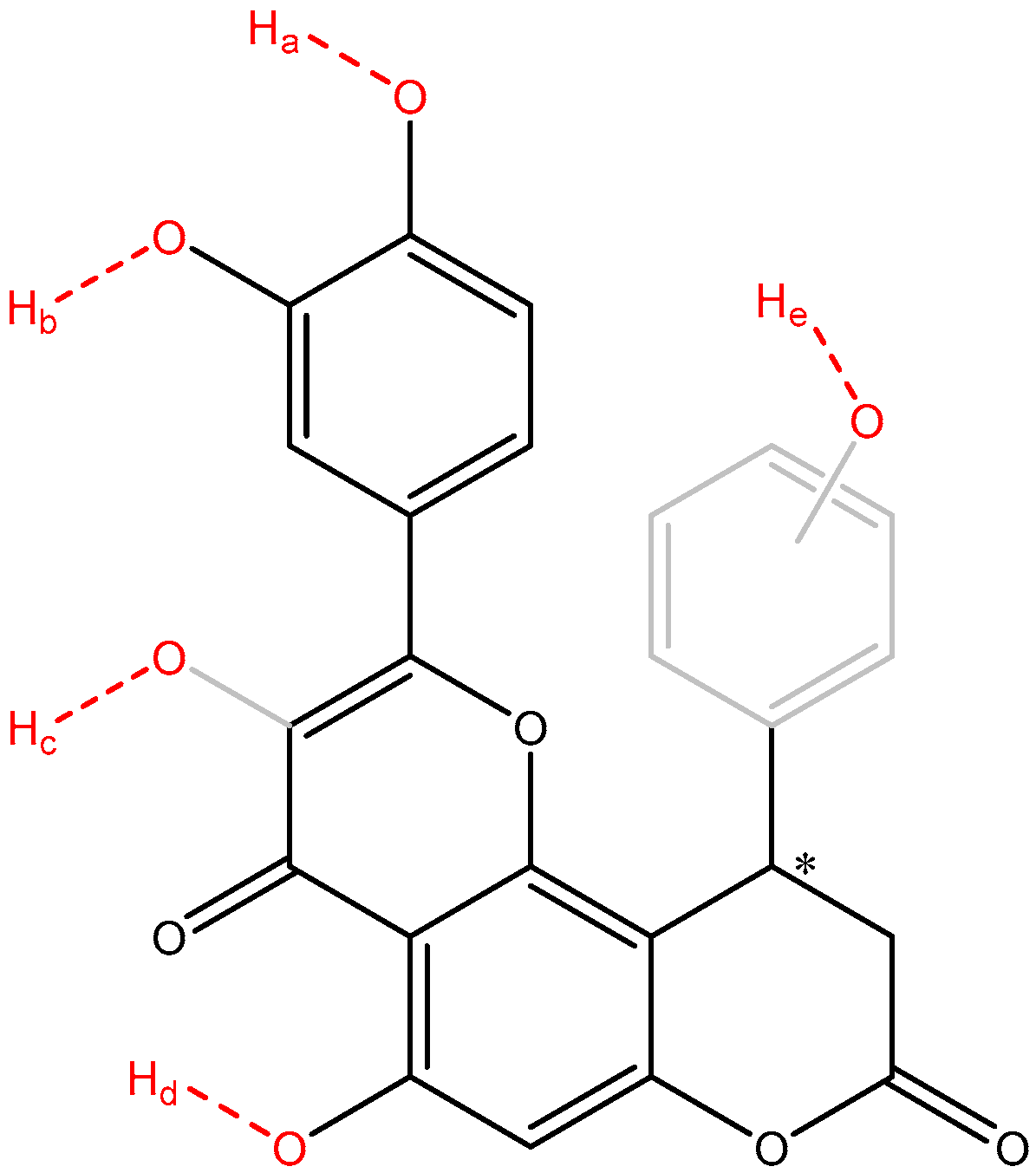

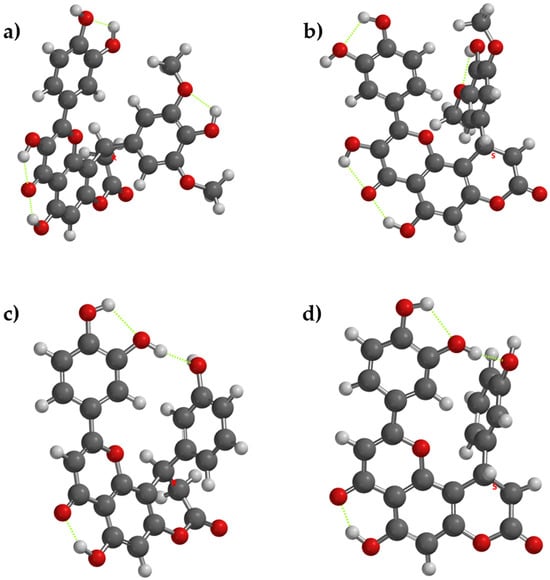

If the acceptor from the substituent ring grafted in position 10 of the core structure is a phenol group (as in compound 8), the acceptor OH group will be more active as an antioxidant, due to internal stabilization of the resulting phenoxyl radical—thanks to the intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Between compounds that have a supplementary phenol group on the substituent from position 10 of the main core (compounds 2 and 8), from a comparative point of view, the respective internal hydrogen appears in both enantiomers of compound 8, but it does not appear in compound 2, due to the steric hindrance with the two methoxy groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The lowest energy conformation for enantiomers of compounds 2 and 8 and the internal hydrogen bonding (with green dots). (a) compound 2[R], (b) compound 2[S], (c) compound 8[R], (d) compound 8[S].

The carbonyl oxygen from the pyran-4-one acts as an acceptor of two intramolecular hydrogen bonds in compounds 1–7 and one intramolecular hydrogen bond in compound 8, from the nearby OH groups from positions 3 and 5.

In compounds 1 and 2, HOMO was found across the 2,3-dihydrobenzofurane and 2,6-dimethoxyphenole, respectively, while in compounds 3–8, HOMO was found across the pyran-4-one and the catechol ring grafted on the carbon 2 of the pyranochromene. LUMO was found in the compounds studied on the pyranochromene, except in compound 4 (both enantiomers), where LUMO was found over the quinoxaline moiety. Overall, the HOMO energies range from −5.84 to −6.40 eV, indicating moderate electronic stability across the series. In most cases, the differences in HOMO energies between R and S enantiomers are small (<0.15 eV), suggesting that chirality has a limited influence on the overall electron-donating ability of the molecules. A similar trend is observed for LUMO energies, which span from −2.33 to −3.21 eV. Minor enantiomeric variations reflect subtle changes in molecular conformation rather than fundamental electronic restructuring. The HOMO–LUMO energy gaps vary between 2.90 and 4.07 eV, highlighting differences in electronic excitation energies and chemical reactivity. For most compounds, the HOMO–LUMO gaps of R and S enantiomers are comparable, reinforcing the conclusion that chirality exerts only a marginal effect on the frontier orbital separation. It is worth mentioning that the lowest HOMO-LUMO gaps were found for enantiomers of compound 4, but it must be mentioned that they are found on different regions of the molecules which may interfere the intramolecular charge transfer. The depiction of the HOMO and LUMO of the compounds 1–8 for both R and S enantiomers is presented in Supplementary Materials (Figures S9–S16).

For the compounds 1–8, for both R and S enantiomers, the analysis of the electrostatic potential maps indicated congruent information with previously presented data. The electrostatic potential maps reveal a strongly polarized molecular surface, with electron-rich regions localized mainly on oxygen and nitrogen atoms and electron-deficient regions around hydrogen atoms. The presence of intramolecular hydrogen bonds as previously presented—particularly involving phenolic OH groups and nitrogen atoms—is clearly indicated by complementary positive and negative electrostatic regions. These interactions stabilize the phenolic O–H bonds, reduce their accessibility, and increase the molecular rigidity. Overall, the maps suggest enhanced intramolecular stabilization and a decreased ability of the phenolic groups to participate in hydrogen-atom transfer reactions, leading to reduced antioxidant reactivity by hydrogen atom transfer. The depiction of the electrostatic potential maps for compounds 1–8 is presented in Supplementary Materials (Figures S17–S24).

In contrast to orbital energies, dipole moments show more pronounced enantiomer-dependent variations. Values range from 2.72 to 9.75 D, reflecting significant differences in molecular polarity. Notably, compound 1 and compound 8 show substantially higher dipole moments for the S enantiomer, while compound 2 exhibits a higher dipole moment for the R enantiomer. These discrepancies suggest that stereochemistry can strongly influence charge distribution, which may affect intermolecular interactions, solubility, and antioxidant activity.

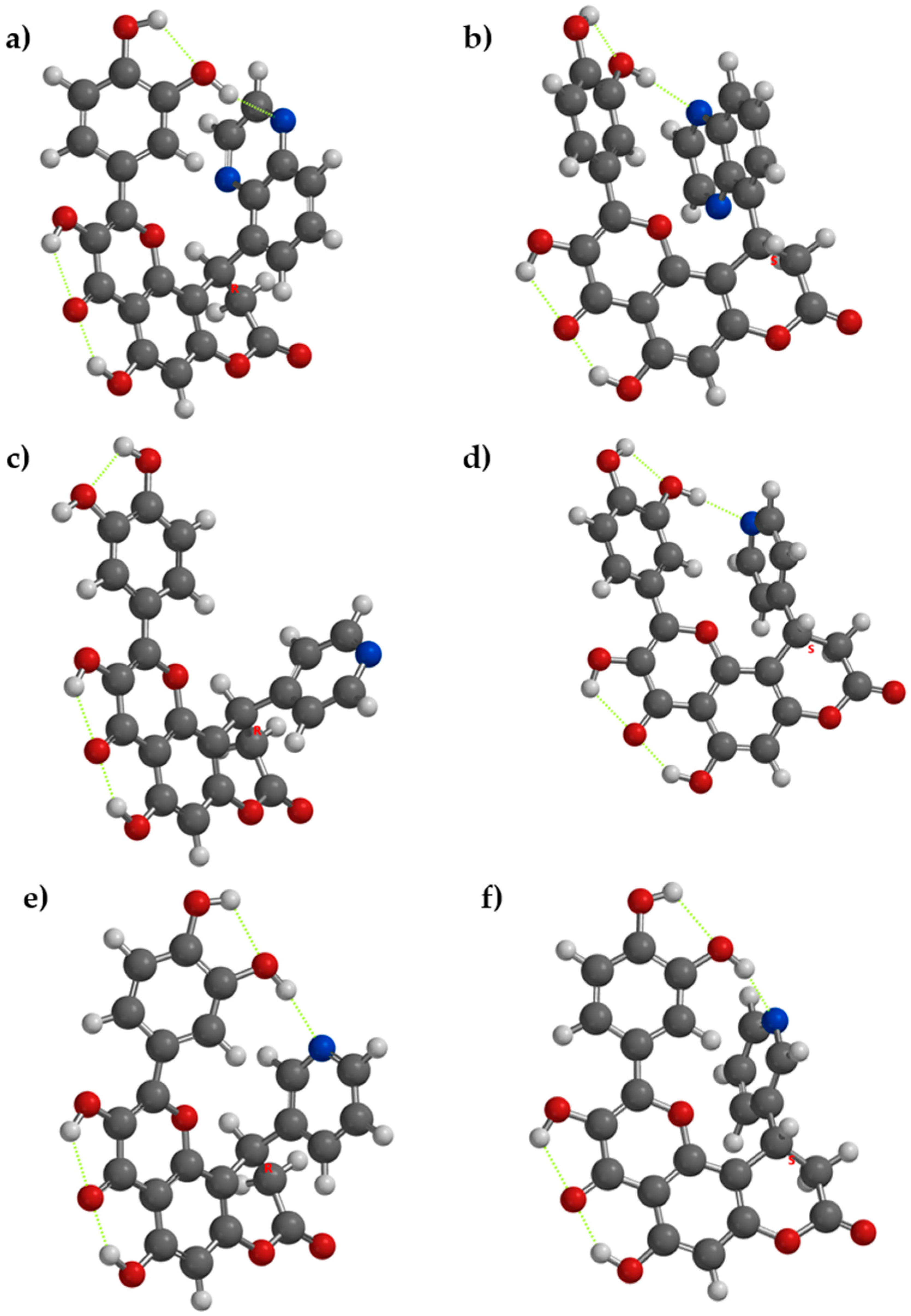

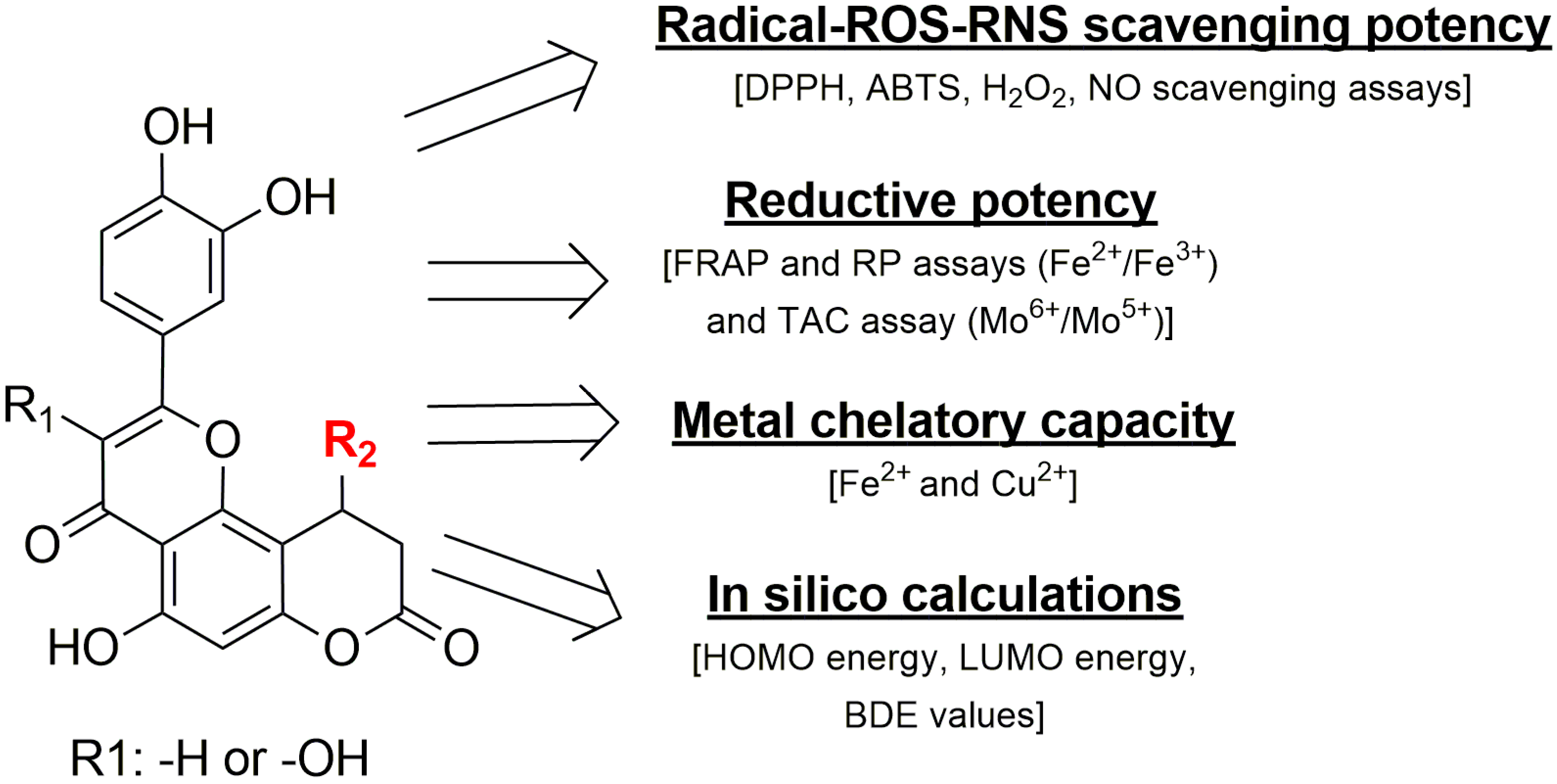

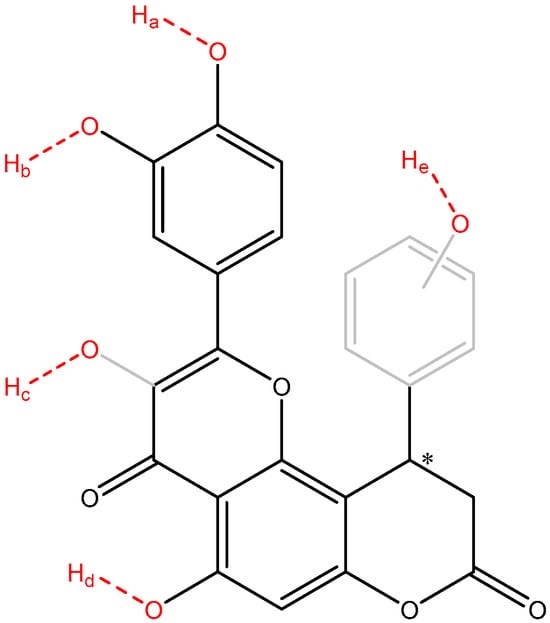

Because the frontier molecular orbitals did not fully characterize the antiradical behavior of the compounds 1–8, the phenol bonds were computed for the O-H bond dissociation enthalpies (Table 10). To have a clear view about the potential sites of the studied molecules which can release hydrogen atoms by heterolytic breaking of the O-H bond, a theoretical molecule is depicted in Figure 4.

Table 10.

The O-H bond dissociation enthalpy (kcal/mol) for phenol groups in compounds 1–8, according to the general structure presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

An overview of the potential O-H bonds which can break and release hydrogen atoms (depicted in red). Sites Ha, Hb, Hd are found in all compounds 1–8, Hc is found in compounds 1–7 only, while site He (ring depicted in gray) is found in compounds 2 and 8 only. The asymmetric carbon atom was labeled with an asterisk.

The analysis of BDE focuses on four distinct types of OH groups—the catechol OHs (sites O-Ha and O-Hb found in compounds 1–8), the enol OH (site O-Hc found in compounds 1–7), the phenol OH (site O-Hd found in compounds 1–8), and the extra phenol group (site O-He found in compounds 2 and 8).

Overall, the most susceptible to release hydrogen atoms OH groups are the ones from catechol (sites O-Ha and O-Hb), with BDEs ranging between 72.45 and 78.03 kcal/mol for site O-Ha and 74.54–79.99 kcal/mol for site O-Hb, respectively, followed by the site O-Hc, with BDEs ranging between 79.82 and 82.17 kcal/mol. The least susceptible group to release hydrogen atoms is the site O-Hd, with all BDEs over 93.96 kcal/mol, in all compounds and in all enantiomers. In both O-Ha and O-Hb sites, a higher susceptibility was found for the R enantiomers to have lower BDEs, except site O-Hb of compound 5, due to the atypical internal hydrogen bonding.

The extra phenol group in compound 2 connected in position 4 of the benzene ring, with two methoxy groups in position 2 and 6 has significantly lower BDE than the one in compound 8, grafted in position 3 of the benzene with no additional methoxy groups. For the O-He 2[R] has a BDE only 0.88 kcal/mol lower than 8[R], but 2[S] have BDE 5.75 kcal/mol lower than 8[S], indicating the high importance of the stereoisomerism in this context. From a comparative point of view, the extra phenol group in compound 2 with two nearby methoxy groups, is significantly better in terms of antioxidant activity, because they hinder the internal hydrogen bonding between the phenol groups between the two rings, when compared to compound 8. BDEs for the site O-Hb are 1.83–1.92 kcal/mol lower while BDEs for the site O-Ha they are 3.88–4.22 kcal/mol lower in compound 2, when compared to compound 8.

The site O-Hc exhibited intermediate BDEs and might contribute per se to the overall antioxidant activity of the compounds. But an interesting finding that is worth mentioning is the influence of O-Hc site on the reactivity of sites O-Ha and O-Hb. In all compounds 1–7 (which have the O-Hc site), the O-Ha site exhibited lower BDEs than O-Hb site, but in compound 8 (which lacks the O-Hc site) the O-Ha sites have higher BDEs than the O-Hb sites. This effect can be attributed to the favorable inductive electronic effects of the O-Hc site to the piranone, where the catechol ring is connected too, reducing the electron withdrawal effects of the piranone from the catechol ring.

4. Conclusions

In this study, novel hybrid molecules combining the structural features of 7-hydroxycoumarin (umbelliferone), quercetin, and luteolin were successfully designed and synthesized, aiming to enhance antioxidant efficacy through molecular conjugation. The synthesized compounds exhibited pronounced radical scavenging activity against ABTS and DPPH (hydrophilic and lipophilic radicals), as well as effective neutralization of biologically relevant ROS and RNS, including hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide. Notably, several derivatives surpassed the antioxidant performance of established reference compounds, such as Trolox and vitamin C. The observed activities were dose dependent and supported by low IC50 values, particularly for the most active hybrids. In addition to free radical scavenging, the compounds demonstrated strong reducing power of various metal ions in various conditions and significant metal chelating capacity toward iron and copper ions. DFT calculations were performed to gain insight into the electronic features governing the observed antiradical activity of the compounds. The single covalent bonds, from position 2 (linking the 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl moiety) and position 10 (variable substituent, depending on the compound) of the pyranochromene, are of particular importance in the geometry of the molecules from this research, because between the two moieties complex interactions can occur, dependent on the enantiomer and type of substituent grafted in position 10 of the main pyranochromene core. These combined properties underline their multifunctional antioxidant profile via several tested assays (Figure 5). Overall, the results suggest that the designed coumarin–flavonoid hybrids represent promising lead compounds for the development of protective agents against oxidative stress-related toxicity and inflammation.

Figure 5.

An overview of the assays and the tested properties of the compounds and their important molecular characteristics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/oxygen6010003/s1, Figure S1. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of compound 1. 1[R]—left, 1[S]—right. Figure S2. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of for compound 2. 2[R]—left, 2[S]—right. Figure S3. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of for compound 3. 3[R]—left, 3[S]—right. Figure S4. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of for compound 4. 4[R]—left, 4[S]—right. Figure S5. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of for compound 5. 5[R]—left, 5[S]—right. Figure S6. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of for compound 6. 6[R]—left, 6[S]—right. Figure S7. The lowest energy conformation of enantiomers of for compound 7. 7[R]—left, 7[S]—right. Figure S8. The lowest energy conformation for compound 8. 8[R]—left, 8[S]—right. Figure S9. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 1. Top left—HOMO of 1[R], top right—LUMO of 1[R], bottom left—HOMO of 1[S], bottom right—LUMO of 1[S]. Figure S10. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 2. Top left—HOMO of 2[R], top right—LUMO of 2[R], bottom left—HOMO of 2[S], bottom right—LUMO of 2[S]. Figure S11. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 3. Top left—HOMO of 3[R], top right—LUMO of 3[R], bottom left—HOMO of 3[S], bottom right—LUMO of 3[S]. Figure S12. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 4. Top left—HOMO of 4[R], top right—LUMO of 4[R], bottom left—HOMO of 4[S], bottom right—LUMO of 4[S]. Figure S13. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 5. Top left—HOMO of 5[R], top right—LUMO of 5[R], bottom left—HOMO of 5[S], bottom right—LUMO of 5[S]. Figure S14. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 6. Top left—HOMO of 6[R], top right—LUMO of 6[R], bottom left—HOMO of 6[S], bottom right—LUMO of 6[S]. Figure S15. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 7. Top left—HOMO of 7[R], top right—LUMO of 7[R], bottom left—HOMO of 7[S], bottom right—LUMO of 7[S]. Figure S16. The frontier molecular orbitals for enantiomers of compound 8. Top left—HOMO of 8[R], top right—LUMO of 8[R], bottom left—HOMO of 8[S], bottom right—LUMO of 8[S]. Figure S17. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 1. Left—1[R], right 1[S]. Figure S18. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 2. Left—2[R], right 2[S]. Figure S19. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 3. Left—3[R], right 3[S]. Figure S20. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 4. Left—4[R], right 4[S]. Figure S21. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 5. Left—5[R], right 5[S]. Figure S22. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 6. Left—6[R], right 6[S]. Figure S23. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 7. Left—7[R], right 7[S]. Figure S24. The electrostatic potential maps of compound 8. Left—8[R], right 8[S].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; software, G.M.; methodology, V.K., B.L., A.K.; investigation, M.F., P.T.-N. and G.P.; data curation, P.T.-N. and A.G.; formal analysis, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.-N. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, P.T.-N., G.M. and A.G.; supervision, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Victor Kartsev was employed by the company InterBioScreen. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Dzobo, K. The role of natural products as sources of therapeutic agents for innovative drug discovery. Compr. Pharmacol. 2022, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, C.L.; Teixeira, M.M.; Adelson, D.L.; Buenz, E.J.; David, B.; Glaser, K.B.; Harata-Lee, Y.; Howes, M.R.; Izzo, A.A.; Maffia, P.; et al. Corrigendum to “Future directions for the discovery of natural product-derived immunomodulating drugs: An IUPHAR positional review” [Pharmacol. Res. 177 (2022) 106076]. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 180, 106207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, H.; Chen, X. A review of classification, biosynthesis, biological activities and potential applications of flavonoids. Molecules 2023, 28, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luna, S.L.; Ramírez-Garza, R.E.; Saldívar, S.O.S. Environmentally friendly methods for flavonoid extraction from plant material: Impact of operating conditions on yield and antioxidant properties. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 6792069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant flavonoids: Chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Šamec, D.; Tomczyk, M.; Milella, L.; Russo, D.; Habtemariam, S.; Suntar, I.; Rastrelli, L.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J. Flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in plants: Versatile targets for metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 38, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, M. Biosynthesis of diverse class flavonoids via shikimate and phenylpropanoid pathway. In Bioactive Compounds; Zepka, L.Q., Nascimento, T.C.D., Jacob-Lopes, E., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2021; Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, H.; Asif, S.; Andleeb, A.; Hano, C.; Abbasi, B.H. Flavonoid production: Current trends in plant metabolic engineering and de novo microbial production. Metabolites 2023, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, N.; Gahlawat, S.K.; Lather, V. Flavonoids: A nutraceutical and its role as anti-inflammatory and anticancer agent. In Plant Biotechnology: Recent Advancements and Developments; Gahlawat, S., Salar, R., Siwach, P., Duhan, J., Kumar, S., Kaur, P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jucá, M.M.; Filho, F.M.S.C.; de Almeida, J.C.; Mesquita, D.S.; Barriga, J.R.M.; Dias, K.C.F.; Barbosa, T.M.; Vasconcelos, L.C.; Leal, L.K.A.M.; Ribeiro, J.R. Flavonoids: Biological activities and therapeutic potential. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, C.; Sánchez-Quesada, C.; Gaforio, J.J. Dietary flavonoids as cancer chemopreventive agents: An updated review of human studies. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, M.; Ahmad, A. Flavonoids as nutraceuticals. In Therapeutic, Probiotic, and Unconventional Foods; Grumezescu, M.A., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelia, V.; Aversano, R.; Chiaiese, P.; Carputo, D. The antioxidant properties of plant flavonoids: Their exploitation by molecular plant breeding. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A.K. Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: An overview. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 162750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justyńska, W.; Grabarczyk, M.; Smolińska, E.; Szychowska, A.; Glabinski, A.; Szpakowski, P. Dietary Polyphenols: Luteolin, Quercetin, and Apigenin as Potential Therapeutic Agents in the Treatment of Gliomas. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, V.; Sanz-Lamora, H.; Arias, G.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D.; Relat, J. Metabolic impact of flavonoids consumption in obesity: From central to peripheral. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghinejad, S.; Mousavi, M.; Zeidooni, L.; Mansouri, E.; Mohtadi, S.; Khodayar, M.J. Ameliorative effects of umbelliferone against acetaminophen-induced hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation in mice. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 19, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kang, Y.H.; Kang, M.K. Umbelliferone attenuates diabetic sarcopenia by modulating mitochondrial quality and the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Phytomedicine 2025, 144, 156930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornicka, A.; Balewski, Ł.; Lahutta, M.; Kokoszka, J. Umbelliferone and its synthetic derivatives as suitable molecules for the development of agents with biological activities. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talevi, A. Multi-target pharmacology: Possibilities and limitations of the skeleton key approach. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, X.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Quercetin nanoformulations: A promising strategy for tumor therapy. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 6664–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Barber, E.; Kellow, N.J.; Williamson, G. Improving quercetin bioavailability: A systematic review and meta-analysis of human intervention studies. Food Chem. 2025, 477, 143630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, N.; Yang, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Q.; Lu, K.; et al. Total synthesis of 8-(6″-umbelliferyl)-apigenin and its analogs as anti-diabetic reagents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 122, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, H.S.P.; Tangeti, V.S. Synthesis of 3-Aroylcoumarin-Flavone Hybrids. Lett. Org. Chem. 2012, 9, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazai, L.; Zsoldos, B.; Halmai, M.; Keglevich, P. Flavone Hybrids and Derivatives as Bioactive Agents. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A.; Ahamed, A.; Ali, D.; Alarifi, S.; Akbar, I. Dopamine-mediated vanillin multicomponent derivative synthesis via grindstone method. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods for evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiouvannis, G.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Rekka, E.A. Nipecotic acid derivatives as potent agents against neurodegeneration. Molecules 2022, 27, 6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolov, S.; Ivanov, I.; Bojilov, D. Synthesis of a new 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline hybrid of ibuprofen. Molbank 2022, 2022, M1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.M.; Boothapandi, M.; Sultan Nasar, A. Nitric oxide, DPPH and hydrogen peroxide radical scavenging activity of TEMPO-terminated polyurethane dendrimers. Data Brief 2019, 28, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, R.P.; Trindade, M.A.; Tonin, F.G.; Lima, C.G.; Pugine, S.M.; Munekata, P.E.; Lorenzo, J.M.; de Melo, M.P. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity of plant extracts by three methods. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. Fe3+ reducing power as a common assay for antioxidants. Processes 2025, 13, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mic, M.; Pîrnău, A.; Floare, C.G.; Marc, G.; Franchini, A.H.; Oniga, O.; Vlase, L.; Bogdan, M. Synthesis and molecular interaction study of a diphenolic hydrazinyl-thiazole compound. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1244, 131278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokwah, D.; Kwatia, E.A.; Amponsah, I.K.; Jibira, Y.; Harley, B.K.; Ameyaw, E.O.; Obese, E.; Biney, R.P.; Mensah, A.Y. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of Aidia genipiflora (DC.) dandy (rubiaceae). Heliyon 2022, 8, e10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, L.; Mutelet, F.; Canabady-Rochelle, L. Antioxidant properties of phenolic surrogates of lignin depolymerisation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Shiau, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-M.; Chiou, T.-K. Antioxidant activities of carnosine and anserine. J. Food Drug Anal. 2003, 11, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, J.; Pal, T.K.; Hasan, T. Theoretical investigations on antioxidant potential of 2,4,5-trihydroxybutyrophenone. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.A.; Baumgartner, M.T. Reaction mechanism of 4-hydroxycoumarins against DPPH. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 601, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zheng, Y.; An, L.; Dou, Y.; Liu, Y. DFT study of polyphenolic deoxybenzoins. Food Chem. 2014, 151, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, C.; Miranda, F.S.; Gonçalves, N.S.; Spinelli, A. Antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds: A DFT study. Redox Rep. 2004, 9, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonijević, M.R.; Simijonović, D.M.; Avdović, E.H.; Ćirić, A.; Petrović, Z.D.; Marković, J.D.; Stepanić, V.; Marković, Z.S. Green synthesis of coumarin-hydroxybenzohydrazide hybrids. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, S.; Tehrani, A.D.; Shamlouei, H. Antioxidant activities of carbohydrate-based gallate derivatives. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 377, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, G.; Stana, A.; Tertiş, M.; Cristea, C.; Ciorîţă, A.; Drăgan, Ș.-M.; Toma, V.-A.; Borlan, R.; Focșan, M.; Pîrnău, A. Discovery of new hydrazone–thiazole polyphenolic antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Liu, X.; Chang, Y.; Wang, R.; Lv, T.; Cui, C.; Liu, M. Investigation of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of luteolin, kaempferol, apigenin and quercetin. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 137, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittasupho, C.; Manthaisong, A.; Okonogi, S.; Tadtong, S.; Samee, W. Effects of quercetin and curcumin combination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 23, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, B.; Singh, S.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S.; Arora, S. Umbelliferone isolated from Acacia nilotica. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Sun, M.; Cen, J.; Xu, J. Role of luteolin in protection against oxidative stress. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 74, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, A.R.; Pargalava, N.; Sadun, A.A. Blindness following hydrogen peroxide ingestion. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodosis-Nobelos, P.; Rekka, E.A. Antioxidant potential of vitamins. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Fee, M.; McGlynn, E.; Marshall, B.; Akers, K.G.; Hatten, B. Embolic phenomena after hydrogen peroxide exposure. Clin. Toxicol. 2023, 61, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Role of metabolic H2O2 generation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 8735–8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Kim, S.; Kang, D. Hydrogen peroxide and peroxiredoxins in the cell cycle. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolov, S.; Bojilov, D.; Ivanov, I.; Marc, G.; Bataklieva, N.; Oniga, S.; Oniga, O.; Nedialkov, P. Biofunctional ketoprofen derivatives. Processes 2023, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.E.; Lee, J.S. Regulation of inflammatory mediators in nitric oxide synthase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, M.; Inoue, T.; Asai, Y.; Hori, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Matsuo, S.; Tsuchida, W.; Suzuki, S. Protective role of localized nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 23, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, N. Plant-derived phenolics as regulators of nitric oxide production. Med. Gas Res. 2026, 16, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, G.; Moreno, L.; Cogolludo, A.; Galisteo, M.; Ibarra, M.; Duarte, J.; Lodi, F.; Tamargo, J.; Perez-Vizcaino, F. Nitric oxide scavenging by quercetin. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtová, M.; Brdová, D.; Křížkovská, B.; Tedeschi, G.; Nejedlý, T.; Strnad, O.; Dobiasová, S.; Osifová, Z.; Kroneislová, G.; Lipov, J.; et al. Nitrogen-containing flavonoids. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 34938–34950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaisankar, D.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Ramasamy, J. Therapeutic potential of flavonoid-enriched Chinese medicinal herbs in atherosclerosis, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Pharmacol. Res.—Mod. Chin. Med. 2025, 17, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachelska, M.A.; Karpiński, P.; Kruszewski, B. A Comprehensive Review of Biological Properties of Flavonoids and Their Role in the Prevention of Metabolic, Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Sueta, G.; Campolo, N.; Trujillo, M.; Bartesaghi, S.; Carballal, S.; Romero, N.; Alvarez, B.; Radi, R. Biochemistry of peroxynitrite. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1338–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalenikhina, Y.V.; Kosmachevskaya, O.V.; Topunov, A.F. Peroxynitrite: Toxic agent and signaling molecule. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2020, 56, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumilaar, S.G.; Hardianto, A.; Dohi, H.; Kurnia, D. Free radicals, oxidative stress and antioxidants. J. Chem. 2024, 2024, 5594386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, M.M.; Erxleben, A.; Ochocki, J. Properties and applications of flavonoid metal complexes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 45853–45877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torreggiani, A.; Trinchero, A.; Tamba, M.; Taddei, P. Raman and pulse radiolysis studies of quercetin. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2005, 36, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, T.; Ashfaq, M.; Saleem, M.; Rafiq, M.; Shahzad, M.I.; Kotwica-Mojzych, K.; Mojzych, M. Pyridine scaffolds and phenols. Molecules 2021, 26, 4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Oniszczuk, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Combrzyński, M.; Nowakowska, D.; Matwijczuk, A. Influence of in vitro digestion on food polyphenols. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primikyri, A.; Mazzone, G.; Lekka, C.; Tzakos, A.G.; Russo, N.; Gerothanassis, I.P. Zinc(II) chelation with quercetin and luteolin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomozová, Z.; Catapano, M.C.; Hrubša, M.; Karlíčková, J.; Macáková, K.; Kučera, R.; Mladěnka, P. Chelation of iron and copper by quercetin metabolites. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 5926–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.