Abstract

This review indicates that microalgae may serve as a sustainable supply of bioactive compounds and lipids over the long run. It also discusses the significance of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in biotransformation processes. Microalgae contribute to food security and environmental sustainability due to their rapid growth and diverse applications, including food, feed, and biofuels. Fermentation with LAB and S. cerevisiae enhances the nutritional and functional properties of microalgal biomass, rendering it more digestible, bioactive, and palatable. This review discusses the metabolic characteristics of LAB and S. cerevisiae, their ability to modify microalgal components through enzymatic action, and the resultant products, including enhanced fatty acid profiles and bioactive compounds. Furthermore, the biotransformation of pigments during LAB fermentation is examined, revealing significant alterations in the hue and bioactivity of the pigments, hence enhancing the appeal of microalgal products. Future perspectives emphasize the necessity for further investigation to identify optimal fermentation conditions and to explore the synergistic interactions between LAB and S. cerevisiae in the production of novel beneficial components from microalgae using both microbes.

1. Introduction

It is necessary to incorporate alternative biomass to ensure the security of our food supply and to sustain our expanding human and animal populations. Population growth, resource diminution, climate change, and rapid urbanization all pose significant challenges to ensuring a sustainable food supply for the future [1].

Depending on their size, there are two types of algae: macroalgae and microalgae. While macroalgae are huge, multicellular organisms that are visible to the unaided eye, microalgae are unicellular organisms that can be either prokaryotic (such as cyanobacteria or chloroxybacteria) or eukaryotic (such as Chlorophyta) [2]. Although the usage of microalgae as food has been around since the Aztec era (1345 to 1521 CE) [3], there is a growing market for algal-derived food ingredients [4], feed ingredients [5], and water-purifying agents [6]. Under optimal conditions, microalgae are expected to develop up to ten times faster than conventional crops cultivated on land [7], making them a potentially sustainable source of feed components.

Microalgae are rich in carbon compounds, which can be utilized in biofuels, dietary supplements, medications, and personal care products [8]. They also help reduce atmospheric CO2 and are used in wastewater treatment. Microalgae manufacture many bioproducts, including lipids, proteins, vitamins, carotenoids, and bioactive molecules, among many others [9]. Microalgae have recently attracted much attention as a potential renewable feedstock for biodiesel production; therefore, biorefineries have decided to try something new. Their capacity as a future resource of renewable and eco-friendly bioproducts could be fostered using growth-promoting techniques and genetic engineering.

Furthermore, a variety of health-promoting products are derived from biologically active extracts from different microalgae as seen in Table 1. Sulphate polysaccharides, immunomodulatory substances generated from algae, are one example. They show great promise as potential pharmacological alternatives. Furthermore, sulfolipids are used as adjuvants in vaccines to boost the immune system’s ability to fight cancer cells [10].

Table 1.

Examples of health benefits of some bioactive compounds from different microalgal species.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized the use of astaxanthin, a pigment produced from the microalga Haematococcus pluvialis that is widely recognized as a health-promoting dietary supplement [24]. Accurate assessments of microalgae’s bioactive components and nutrient content are required before they can be used for food. Bioactive chemicals produced by microalgae have demonstrated promising efficacy in the treatment of numerous diseases and conditions, such as diabetes, AIDS, malaria, and obesity [25].

Desiccated, intact microalgal biomass of Spirulina sp. and Chlorella sp. is currently used as food in the European Union, but it also has applications in human health. Spirulina and Chlorella species have been used extensively and historically; hence, they need further in-depth discussion. Spirulina, scientifically referred to as Arthrospira or Limnospira, is a multicellular creature classified within the phylum Cyanobacteria, an ancient group of life forms on earth [26,27]. It lacks a nucleus and other cellular organelles, having its cells densely populated with photosynthetic thylakoid membranes and encased by cytoplasmic and outer membranes [27]. Spirulina served as a nutritional resource for the Aztecs and Mesoamericans until the 16th century [28]. In 1852, Arthrospira was the new classification for spirulina due to considerations related to morphology [27]. Spirulina/Arthrospira was detected once again as the most prevalent phytoplankton in the lakes of East Africa in the year 1931 [27]. The name Arthrospira was declared invalid and all regularly helically coiled oscillatorian animals were assigned to the already existing genus Spirulina in 1932, when the class Cyanophyceae was reorganized [29].

Modern polyphasic approaches and DNA sequencing technology have made taxonomic problems more straightforward and have made phylogenetic investigations of cyanobacterial species more accurate [27]. Subsequent investigations disclosed significant disparities between the type strain Arthrospira jenneri and commercially cultivated strains. The designation Limnospira is suggested for species of economic significance, including the previously recognized Arthrospira maxima, Arthrospira fusiformis, and Arthrospira platensis [30]. At the moment, three distinct groups of organisms are known to exist: Spirulina spp., Arthrospira spp., and Limnospira spp.

The two most widely available commercial species of Spirulina are the filamentous, brackish cyanobacterial species A. platensis and A. maxima. Numerous positive health impacts of spirulina have been found, such as its antihypertensive and antioxidant properties [31]. Also, the Spirulina methanolic extract showed a promising inhibitory action on some food-borne pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella spp. [32], Escherichia coli [33], and Bacillus cereus [34].

In a study, Chuang et al. (2014) [35] investigated the antileukemia effects of the microalgae Dunaliella salina in mice with leukemia implants. Research indicates that Dunaliella salina synthesizes both all-trans-β-carotene and 9-cis-β-carotene, which possess distinct chemical structures and influence biological functions, including antioxidant activity and the prevention of carcinogenesis. All-trans-β-carotene functions as an antioxidant and a precursor to vitamin A, whereas 9-cis-β-carotene modulates cell proliferation and neoplastic transformation, but perhaps exhibits diminished efficacy in some cellular responses [36].

Levin and Mokady’s 1994 study aimed to compare the in vivo antioxidative capability of a Dunaliella β-carotene extract abundant in the 9-cis isomer with that of synthetic all-trans β-carotene [37]. Oxidized dietary oil was utilized to provoke peroxidation activities within the body. Hepatic reserves of β-carotene and vitamin A were preserved solely in rats administered Dunaliella extract in conjunction with oxidized oil. The increased degradation of 9-cis β-carotene noted in the livers of these animals may suggest that, similar to the effects observed in vitro, this isomer exhibits a higher affinity for free radicals, and consequently, may serve as a more effective antioxidant than the all-trans form in vivo [36].

On the other side, Hu et al., 2008 discovered that the algal carotenoid extract exhibited much greater antioxidant activity compared to all-trans versions of α-carotene, β-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin [38]. The cis isomers of carotenoids in the extract, particularly 9- or 9′-cis-β-carotene, may be crucial to the antioxidant activity. Consequently, our research supplies the essential data to utilize D. salina as a health food [38].

Levin and Mokady evaluated the antioxidant efficiency of 9-cis to all-trans/β-carotene in a 1994 in vitro investigation. Dunaliella bardawil yielded the 9-cis isomer [37]. The concentration of 9-cis/3-carotene in various systems correlated negatively with hydroperoxide levels and positively with residual β-carotene levels. The ratio of 9-cis to all-trans isomers decreased consistently in HPLC examinations of the system, with both isomers present. The results show that 9-cis/β-carotene is more effective as an antioxidant than the all-trans isomer, protecting both methyl linoleate and the all-trans isomer against oxidation. The isomeric difference may be due to the higher reactivity of cis bonds compared to trans ones.

This result was consistent with their previous research, which indicated that D. salina boosted the antioxidant enzyme activities in mice resistant to oxidative corneal injury and hepatotoxicity induced by UV-B and CCl4 [39,40]. Additionally, prior in vivo investigations have shown that D. salina stimulates antioxidant enzyme activity against carcinogen-induced fibrosarcoma in rodents, similar to the effects of a cisplatin-vitamin E combination treatment [41]. In mice, D. bardawile promotes normal cell growth but inhibits tumor progression [42].

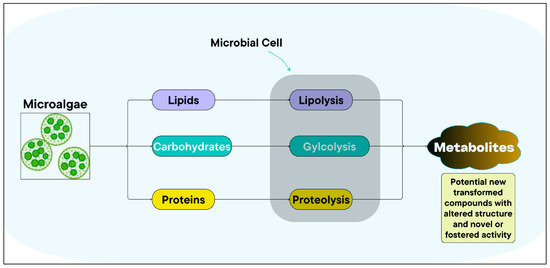

Under particular nutritional conditions, microorganisms can produce a wide range of enzymes and chemicals that are difficult to synthesize, and the pharmaceutical industry is increasingly recognizing microbial transformation (Figure 1) as a manufacturing strategy [43]. The production of various drugs and intermediates can be made less challenging with the aid of biocatalysis.

Figure 1.

Possible metabolic processes employed by microorganisms for nutrient transformation. The figure was obtained with modification from Mazguene (2023) [44].

In contrast to chemical synthesis, they preferentially produce the desired product under mild fermentation conditions, avoiding complex separation and purification [45]. The synthesis of chemicals needs severe circumstances, while microbial transformation occurs in settings that are almost neutral in terms of pH, temperature, and atmospheric pressure. The characteristics of microbial transformation include significant response accuracy, spatial specificity, and enantioselectivity [46,47,48].

Biological systems are responsible for generating natural products, also known as organic chemicals. These natural compounds can be divided into two categories: primary and secondary metabolites. Among these, secondary metabolites have received a lot of interest due to the diverse biological effects they have on other species [49]. Over the past few years, the pharmaceutical industry has begun to recognize microbial transformation as a crucial manufacturing process. Through biocatalysis, it is possible to have the production of particular drugs or intermediates made more straightforward. They eliminate the tedious separation and purification processes that are associated with chemical synthesis by selectively creating the product that is sought under circumstances of mild fermentation [45,47].

A classic technique utilized all around the world for food preparation and preservation is fermentation [50,51]. Algae fermentation is a cost-effective and low-waste alternative to incineration and landfilling [52]. One viable approach to reducing blooms and generating high-value products is through the utilization of algal biomass to generate biofuels and bioactive compounds [53]. These compounds comprise an array of beneficial constituents, including polyphenols and polyunsaturated fatty acids [51,54].

Different types of fermentation can be generally classified especially with the usage of microorganisms and algae under various fermentation conditions leading to different products, for example; methane fermentation, alcoholic fermentation, lactic acid fermentation, hydrogen fermentation, and butyric acid and acetone-butanol fermentation [55]. Microbial fermentations can generate lactic acid through lactic acid fermentation (LAF). There are two main categories of LAF processes: homofermentative (lactic acid yield maximum of 90%) and heterofermentative (lactic acid production maximum of 50%). Many different kinds of microbes, such as lactic acid bacteria and fungus, carry out LAF. For lactic acid bacteria to grow and multiply, an acidic environment (pH 5.5–6.5) is optimal.

With an estimated 80 species, Lactobacillus dominates the lactic acid bacteria genus [56]. Niccolai et al., 2019, 2020 [57,58] investigated the impact of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 on Arthrospira platensis F&M-C256 to yield Lactic acid and functional beverages. The fermentation occurred in the liquid phase at 37 °C, 72 h. In another study by [59], the authors tested the fermentation in liquid phase at 37 °C, 24 h by Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 43,121 on Ar. platensis to produce Lactic acid, while the Solid phase fermentation by Lacticaseibacillus casei 2240, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG on A. platensis to produce fermented freeze-dried spirulina concentrate was approved [60]. On the other hand, Saccharomyces cerevisiae LPB-287 was examined on A. platensis to produce Bioethanol through Fermenting in liquid phase at 30 °C, 24 h [59], while the fermentation effect of S. cerevisiae on A. platensis was examined to produce Ethanol using the anaerobic fermentation for 3 days at 38 °C [61].

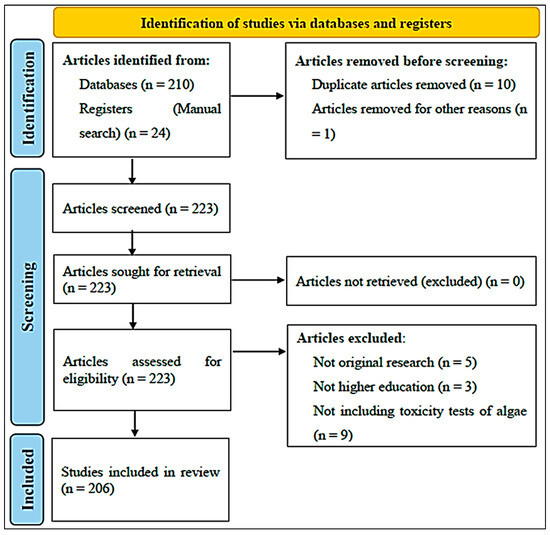

Previously, the fermentation effect of S. cerevisiae on Spirulina platensis to produce ethanol was also examined by Hossain et al. (2015) [62]. The main aim of the present review article is to highlight recent research and studies that cover the real and projected uses of microalgae and cyanobacteria in various industries and fields, and demonstrate some examples of biotransformation processes and the resulting products proving the capability of lactic acid bacteria and S. cerevisiae in bio-transforming the phenolic compounds in those microalgae. Figure A1 represents the PRISMA flow diagram of the current review, which includes a report of the searches of databases and registers.

2. Metabolic Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae

2.1. Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) in Metabolizing Different Vital Compounds

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and S. cerevisiae are essential microorganisms in diverse biotechnological applications, such as food fermentation, biofuel synthesis, and chemical biotransformation [63,64]. Lactic acid bacteria can metabolize carbohydrates, particularly glucose, via glycolysis, resulting in the synthesis of lactic acid. This fermentation process is anaerobic, indicating that it takes place in the absence of oxygen [65].

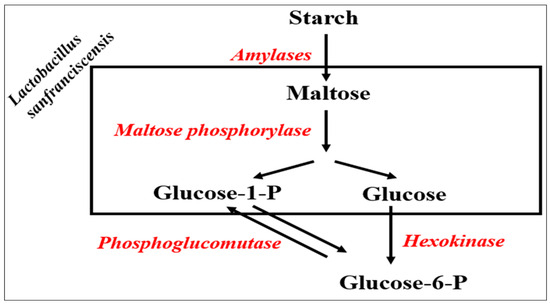

Lactic acid is produced by LAB by the action of enzymes like lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), this process converts pyruvate, a by-product of glycolysis, into lactic acid. The regeneration of NAD+ is necessary for glycolysis to proceed [66]. In addition, LAB can metabolize additional sugars, such as maltose and fructose. However, the efficiency of this process may vary according to the species and strains [67]. Regarding maltose sugar, the efficient breakdown of maltose, the most abundant sugar in this setting, depends on its dedicated catabolic route. Ehrmann and Vogel (1998) described how the genes encoding two crucial enzymes involved in Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis’s maltose metabolism were cloned and sequenced [68]. These enzymes are responsible for catalyzing the reactions mentioned in Figure 2 [68]:

Figure 2.

The crucial enzymes involved in Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis’s maltose metabolism [69].

In the previous study, the authors used the plasmid library containing largely Sau3A-digested L. sanfranciscensis chromosomal DNA in plasmid pSU1 to transform E. coli TSM90. Transformed cells that were able to produce acid while growing on media contained solely maltose as a carbon source were recognized as maltose-positive.

Lactobacillus kunkeei is categorised as a heterofermentative LAB (lactic acid bacterium) for fructose sugar, meaning that it is a lactic acid bacterium that produces lactate, ethanol, and acetic acid as outcomes of the metabolism of fructose (a hexose sugar) [70]. This metabolic pathway generates energy through the production of lactic or acetic acid, but not through the production of ethanol. Ethanol is produced exclusively for the purpose of restoring oxidized cofactors.

Bisson et al. (2017) showed that L. kunkeei regenerates NAD+ differently [71]. L. kunkeei produces more acetic acid and less ethanol from sugars than traditional lactic acid bacteria that heteroferment in the absence of oxygen. When fructose is available, L. kunkeei produces mannitol in large amounts [71]. The conversion of fructose into mannitol supplies NAD+, facilitating metabolism. L. kunkeei is “fructophilic” due to the rapid metabolism and preference for fructose over glucose [71]. L. kunkeei needs pyruvate to grow on glucose. This may be because L. kunkeei cannot synthesize cofactors from ethanol, and L. kunkeei prefers fructose and produces mannitol because it can directly renew cofactors. Direct reduction in fructose yields the same quantity of mannitol as energy [71].

Since it grows on glucose and fructose, L. kunkeei, an obligate fructophilic lactic acid bacterium, can use fructose as an electron acceptor to produce energy levels comparable to aerobic bacteria. A genetic mutation in the alcohol/acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (adhE) gene prevents NAD+/NADH regeneration during glucose metabolism, thereby preventing the production of sufficient ATP for development without an electron acceptor [72].

Particular LAB species can metabolize citrate, transforming it into diacetyl, acetoin, and other taste compounds. This process contributes to the sensory characteristics of fermented food [73]. Lactic acid bacteria are employed in biotechnological processes such as fermenting dairy goods, including yogurt and cheese, sourdough bread, and pickles, among other applications [74]. They have a vital function in improving food safety, boosting flavor, and optimizing texture [75].

2.2. The Flexible Metabolic System of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Utilization of Different Carbon Sources

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sometimes referred to as baker’s yeast, is a eukaryotic microbe widely utilized in many biotechnological applications, particularly in the manufacturing of alcoholic drinks such as beer and wine, as well as in baking [63]. It is employed in various biotechnological applications, including alcoholic fermentation [76], biofuel generation [77], pharmaceutical manufacturing [78], and as a model organism for understanding eukaryotic cell biology and genetics [79].

In addition, S. cerevisiae has a flexible metabolism that can efficiently utilize a diverse array of carbon sources, such as different sugars, alcohols, and organic acids [80]. It also can carry out several metabolic functions, including the production of vitamins, amino acids, and lipids [81]. S. cerevisiae is capable of performing aerobic fermentation, often known as alcoholic fermentation or ethanol fermentation. In this process, glucose is transformed into ethanol and carbon dioxide (CO2) [82]. This process entails glycolysis, close to LAB, subsequently followed by the enzymatic conversion of pyruvate into ethanol and CO2, facilitated by enzymes like pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC) and alcohol dehydrogenase (PDH) [83].

Based on some studies and the additional characteristics of S. cerevisiae, such as its natural resistance to solvents [84,85], extensive application in ethanol production for industry, and capacity to endure oxygen (unlike Clostridia), S. cerevisiae appears to be a suitable candidate for industrial n-butanol synthesis. While it is important to raise the product titer, there have been other instances where increases in this magnitude and even more have been achieved [86].

3. Demonstration of the Capability of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Bio-Transforming Phenolic Compounds in Microalgae and Examples of Resulting Products from Microalgae

The process of biotransformation in microalgae, carried out by LAB and S. cerevisiae, entails the enzymatic alteration of some bioactive primary compounds including; lipids [87], proteins [88,89], pigments [88], and polysaccharides [90] to yield useful products. Besides LAB and S. cerevisiae can break down sugars found in microalgae biomass, resulting in the creation of organic acids, alcohols, and other substances, they can facilitate the decomposition of intricate structures such as proteins and lipids, resulting in the liberation of amino acids, fatty acids, and other biologically active substances [91].

3.1. Spirulina as an Encounter for Bio-Transformation

Spirulina, also referred to as A. platensis, is a kind of cyanobacteria. It shares similarities with microalgae in terms of being a repository of bioactive compounds [92]. Both lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae play crucial roles in metabolizing compounds derived from A. platensis, hence enhancing its nutritional and functional characteristics [93]. The sugars found in A. platensis biomass can undergo fermentation by LAB, resulting in lactic acid and various other organic acids synthesis. The method of fermentation can aid in the preservation of Spirulina biomass and improve its taste [57].

Lactic acid bacteria possess the capacity to synthesize several bioactive substances, including antimicrobial peptides, vitamins (such as B vitamins), and exopolysaccharides. These chemicals can enhance the nutritional value and promote the health advantages of items derived from Spirulina [53] (Table 2). Lactic acid bacteria have proteolytic enzymes capable of breaking down proteins found in Spirulina biomass, resulting in the release of peptides and amino acids. These peptides can have bioactive characteristics, including antioxidant, antihypertensive, and immunomodulatory actions [94]. The process of lactic acid bacteria fermentation enhances the digestibility of Spirulina biomass by enzymatically breaking down intricate carbs and proteins into simpler forms that may be readily assimilated by the human body [93].

Table 2.

General nutritional composition and value in some microalgae.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae can convert the sugars found in Spirulina biomass into ethanol and CO2 through fermentation. Although it may not directly improve the nutritional value of Spirulina, it can be beneficial for producing biofuels or extracting bioactive chemicals using ethanol extraction methods [103]. S. cerevisiae harbors multitude of enzymes responsible for the metabolism of carbohydrates and proteins. The enzymes included in Spirulina biomass can facilitate the decomposition of intricate carbohydrates and proteins, facilitating the liberation of sugars, amino acids, and peptides.

S. cerevisiae can produce metabolites such as organic acids, vitamins, and aroma compounds during fermentation. These metabolites may enhance the sensory properties and nutritional value of Spirulina-derived products [104]. Both LAB and S. cerevisiae have metabolic capacities that can be used to change chemicals found in Spirulina biomass. This leads to the creation of valuable products that have enhanced nutritional, sensory, and functional qualities. Due to their enzymatic activities, fermentation capacities, and metabolic routes, they are highly useful in the advancement of biotechnological applications centered on Spirulina.

3.2. Targeting Chlorella in the Bio-Transformation Processes

Csatlos et al. (2023) employed Chlorella vulgaris (microalgae) as a reservoir of biological constituents, encompassing a wide range of beneficial chemicals, including oleic acid, peptides, astaxanthins, and canthaxanthins [105]. Their investigation sought to examine the appropriateness of C. vulgaris nutrients (biomass) as a medium for the growth and fermentation of Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus in vegetative soy drinks. Additionally, they aimed to assess the brewed produce’s in vitro bio-accessibility, antioxidant capability, and bacterial viability.

The study’s findings revealed that the fermentation of drinks led to an increase in total polyphenols and antioxidant activity. When compared to the control sample, the samples cultured with L. rhamnosus and powdered C. vulgaris showed the most significant levels in polyphenols. According to the study, samples inoculated with L. rhamnosus (327.26 µg GAE/mL) and L. fermentum (306.72 µg GAE/mL) had considerably higher levels of total polyphenols than the control one (267.08 µg GAE/mL). The antioxidant effect levels varied between 301.76 ± 2.53 µM Trolox/g DW and 497.43 ± 1.28 µM Trolox/g DW. The drink including C. vulgaris, xylitol, and L. rhamnosus exhibited the most effective scavenging action against DPPH radical, which was substantially different from the beverage containing C. vulgaris, xylitol, and L. fermentum (p < 0.05). The control sample had the lowest concentration of antioxidants [105].

The outcomes of the previous study aligned with the data published by Zhao and Shah (2016), who revealed that adding 3.3 g/L of C. vulgaris raised the beer’s polyphenol concentration to 257.81 ± 15.20 µg GAE/mL [106]. Furthermore, the fermentation process and the introduction of probiotics into the drink play a crucial role in enhancing the overall levels of polyphenols and antioxidant activity [107].

Bioconversion of phenolic compounds using LAB was investigated in many other studies such as; in green tea with the conversion of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin (EC) into gallocatechin gallate (GCG) and gallocatechin (GC), using Lactobacillus plantarum 62901 and Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides K200132 [108,109].

Sahin et al. (2022) conducted a study to examine the characteristics of unfermented (unFS) and fermented Spirulina (FS) samples using various yeast species, namely Debaryomyces hansenii Y-7426, Kluyveromyces marxianus Y-329, and S. cerevisiae Y-369 [110]. The researchers generated protein fragmentation pictures of spirulina products employing SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) technique. Distinct variations in the breakdown of proteins were noted across various yeast species following 48 h fermentations, as seen by the SDS-PAGE profile.

This profile facilitated the identification of soluble proteins spanning a range of 175 to 10.5 kDa. Multiple bands with molecular weights ranging from 10 to 51 kDa and less than 10.5 kDa were seen for the unFS product. The protein profiles obtained from SDS-PAGE analysis exhibited similarities to those documented in prior research on Spirulin [50]. The presence of three bands ranging from 14 to 22 kDa could potentially indicate the presence of biliproteins, specifically C-phycocyanin (with subunits weighing 19.5 kDa and 21.5 kDa) and allophycocyanin (with subunits weighing 19.6 kDa and 17.7 kDa for the a and b subunits, respectively) [111].

4. Biotransformation of Fatty Acid (FA) Profiles in Microalgae

Microalgae-Derived Lipids

Research on microbial production of lipids was primarily sparked decades ago. The employment of microorganisms to synthesize lipids has several advantages over the conventional production of vegetable or bean oils, including a shorter life cycle, lower manpower needs, less reliance on geography and climate, and simpler scaling up. Microbial strains classified as oleaginous are those that can produce lipids at levels more than 20% of their dry weight [112].

Many microalgae species have a high lipid content, distinctive lipid structure, an ability to grow quickly in a variety of environmental conditions, and can be harvested daily [113]. Based on these features, microalgae strains have been identified as commercially promising sources of the third-generation feedstocks for bioproducts as well as for use in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical industries [114]. It is thought that the lipid content of microalgae results from their adaptation to various environmental factors.

To illustrate, certain microalgae that have drawn more economic interest can produce large amounts of long-chain polyunsaturated FAs responding to environmental stimuli, including s light, temperature or nutrient constraint. Moreover, microalgae can be distinguished from higher plant- or other animal-based alternatives due to the presence of unusual lipids and fatty acids [115].

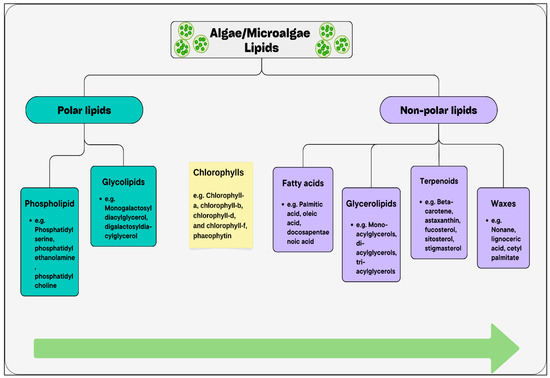

Microalgae possess two primary ways for synthesizing lipids. The first is the chloroplast’s acetate pathway, which produces fatty acids and their derivatives by de novo synthesis. The second pathway is the methylerythritol phosphate deoxy-xylulose phosphate pathway, which produces terpenoids, including carotenoids and sterols. There are several different types of microalgal lipids, ranging from polar to nonpolar, exhibiting possible uses in specialty chemicals, food, and energy.

Polar lipids are characterized by having more oxygen and charged side groups such as phospholipids and glycolipids. These characteristics permit them to interact with water molecules in a moderate manner. In contrast, nonpolar lipids are hydrocarbon compounds such as waxes, terpenoids, fatty acids (FAs), and their derivatives. these lipids are characterized by lacking the ability to interact with water molecules and have few or no of both oxygen and charges [116]. Figure 3 classifies lipids according to their polarity along with some representative metabolites.

Figure 3.

Lipid classification of algae/microalgae including some representative metabolites. Green arrow represents polarity. According to the green arrow, lipid classes are arranged from left to right, from polar to non-polar, based on their interaction with water molecules [116].

Microalgal species can yield biomass with a high lipid content of up to 70% of cell dry mass (CDM) [113]. Lipid content can be maximized by exposing microalgae to environmental stresses (e.g., abiotic stress). Even though numerous abiotic methods, such as nutrient limitation, high salinity, and intense illumination, have been investigated to raise the FA levels in microalgae biomass, there are currently few quantifiable effects of significant abiotic stress on biomass and lipid levels [117]. However, lipid content can reach 90% of CDM under certain conditions [113]. These lipids are usually characterized by chromatographical analytical approaches like GC-MS and LC-MS to reveal the lipid composition, lipid classification, fatty acids, and unsaponifiable composition (including sterols and hydrocarbons) [114].

Microalgae lipids and fatty acids profiles exhibit significant variations in their chemistry, both among species and within the same species [118]. Accordingly, certain fatty acid compositions can define distinct groups of microalgae. For example, Bacillariophyceae are rich in 14:0, 16:0, 16:1, and 20:5, whereas Chrysophyceae are known to have 14:0, 16:0, 18:3, and 22:6, and Chlorophyceae have 16:0, 16:1, and 18:1 [119]. Furthermore, saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) are the most prevalent lipid components in eukaryotic microalgae, accounting for about 80% of the total lipids, while poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are found in high levels (20–60%) in some cyanobacterial classes.

Long-chain PUFAs like docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6n−3) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5n−3) are abundant in the lipid segments of certain marine microalgae strains. When grown under comparable conditions, the marine Phaeodactylum tricornutum contained long-chain PUFAs, and the freshwater Chlorella vulgaris exhibited high quantities of PUFAs [118].

Table 3 Lists selected microalgal strains with their lipid content and related lipid classes. For a thorough review and discussion of microalgal lipids, their synthesis, and classification, the reader is referred to [87].

Table 3.

Selected species of microalgae, their lipid content, and related lipid groups isolated.

5. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Have the Potential to Transform Lipid Profile of Microalgae

5.1. Transformation of Lipid Profile by Lactic Acid Bacteria

Utilizing microalgae biomass to produce medicinal and nutraceutical lipids and fatty acids (FAs) is becoming more and more popular [114]. These lipids can be utilized to improve fish food in a variety of ways, including aquiculture, biodiesel production, human food as food additives and as essential FAs, biological carbon sequestration, and sewage treatment [118]. However, using lactic acid bacteria for fermentation/biotransformation is a promising area of study as they can enhance functionality of algal-derived nutrients.

These bacterial strains can hydrolyse both plant and microalgal cell walls. This process breaks down and solubilize complex cellular compounds such as proteins, lipids and carbohydrates, uncovering fostered biological activities like antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activity, among others [50]. Although the high potential of microalgae derivatives for various applications, research in this area is still relatively underexplored, especially using biotransformation of algal biomass into value added bioactive molecules [139].

Using a zebrafish model, Matsuura et al. investigated the efficacy of Sparassis crispa fermented by LAB, commonly referred to as cauliflower mushroom, against obesity. According to their findings, LAB-fermented cauliflower mushrooms reduce their lipid content and can stop hepatic steatosis by triggering beta-oxidation. Additionally, adding LAB-fermented cauliflower mushrooms to the diet as a functional food may help prevent obesity and lessen the incidence of disorders linked to obesity [140].

A study was carried out to further develop the biomass bioactivity profile of Spirulina because of the high concentration of beneficial and nourishing chemicals in its biomass. For 72 h, the researchers fermented the microalgal biomass of Ar. platensis (microalgae) using L. plantarum (LAB), monitoring and comparing several parameters to guarantee accurate results of enhanced bioactivities. The results revealed that following 36 h of fermentation, the total phenolic content increased by 112%, the ferric reducing antioxidant activity by 85%, and the oxygen radical absorption capacity by 36%.

Additionally, the free methionine level rose up by 94% after 72 h, while the DPPH radical scavenging capacity improved by 60% after 24 h. Remarkably, during fermentation, microalgal bioactive substances that were bound in the cell walls were released. These substances offer a great potential as a functional element in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications, ensuring the significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase in the bioactivity [50]. Therefore, the bioactivity of microalgae biomass can be significantly fostered by the biotransformation using lactic acid bacteria.

Another study investigated the impact of chlorella vulgaris (C. vulgaris) on the growth and metabolic activity of lactobacillus spp. bacteria. The research team studied the impact of C. vulgaris as a fermentation matrix to four different strains of Lactobacillus brevis at two different concentrations (0.1% and 1.5% [w/v]). They next assessed the strains’ growth, acidifying activity, fraction of lactic acid isomers, and enzymatic profile. The results exhibited that supplying chlorella to culture media of the tested strains led to a significant effect on all tested parameters. Briefly, adding algae to the growth media of Lactobacillus spp. decreased the logarithmic phase of the bacteria and increased their growth. After introducing C. vulgaris, the LAB’s overall acidity and acidifying activity rose, and its yield of l-lactic acid exceeded that of d-lactic acid.

Furthermore, the enzymatic activity of the LAB strains studied was altered by 1.5% (w/v) C. vulgaris. To illustrate, Lactobacillus brevis ŁOCK 0980 had increased enzymatic activity for valine arylamidase, α-galactosidase, and α-glucosidase [141]. Accordingly, LAB can efficiently ferment algae biomass (carbohydrates, lipid, and protein) to create novel, useful compounds that give the final product advantageous qualities and create novel prospects for different industries.

Spirulina and Chlorella are well-studied microalgal strains as a feedstock for microbial fermentation processes. However, there are limited studies on many other microalgal strains as a fermentable matrix for LAB fermentation such as Chlorococcum sp. among others, which calls for more investigations on the untapped strains. Furthermore, fermentation of algal lipids using LAB is limited in the literature and more investigations are needed to address this gap and unlock the potential of these functional compounds.

Interestingly, through biotransformation, the lipid profile of microalgae was physiologically altered for the first time to produce molecules with related bioactivities. To investigate the metabolites generated, the research team fermented three microalgal biomasses (C. vulgaris, Chlorococcum sp., and A. platensis) using seven LAB strains. The findings showed that a number of relevant chemical families, such as fatty acids, fatty amides, triterpene saponins, chlorophyll derivatives, and purine nucleotides, are present in the fermented extracts. This research makes it possible to create new bioactive molecules using microalgae as feedstock materials for bioconversion processes [139].

Spirulina was added to yogurt, which primarily contains several types of LAB that cause fermentation, to examine its effects on the fermentation procedure, texture, sensory, nutraceutical features of the final product. The nutritional content of spirulina-fortified yogurt was greater than that of the yogurt control. Yogurts supplemented with spirulina had the highest levels of total solids, protein, lipids, and ash. The control and spirulina yogurts had respective total solids of 22.47% and 22.62%. The lipid content of the control (3.38 g) and fortified (3.4 g) yogurt samples did not vary significantly (p > 0.05), although there was a significant difference in total solids between these two yogurts (p < 0.05).

However, the most prevalent FAs in control yogurt were palmitic acid, oleic acid, lauric acid, and stearic acid. In contrast, spirulina yogurt contained six different FAs in addition to these four FAs in the control: linoleic acid, linolenic acid, octadecanoic acid, palmitoleic acid, myristic, capric, and caprylic. Nevertheless, the study showed that adding 0.25% spirulina was considerably enough to speed up the fermentation process (p < 0.05) while maintaining the final product’s textural qualities and sensory acceptability [142].

5.2. Transformation of Lipid Profile by Saccharomyces cerevisiae

One of the common processes in all living organisms, involving bacteria, fungi, algae, plants, etc., is fatty acid synthesis. The majority of bacteria manufacture FAs and use them as membrane constituents, in contrast to eukaryotes that use triacylglycerols (TAG) to store energy in lipid droplets. Approximately 60 species of oleaginous yeasts, including Yarrowia lipolytica, Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus, Lipomyces starkeyi, and Rhodosporidium toruloides, can produce significant amounts of TAG, exceeding 20% DCW, compared to the few bacterial strains that can produce TAG. Naturally, these oleaginous yeasts have developed high-flux routes for FAs that comprise neutral lipids, which are potentially transformed into a range of drop-in fuels and oleochemicals, which are potential sources for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications.

Despite not being categorized as oleaginous yeast, S. cerevisiae has been extensively researched due to its many potential benefits when employed for lipid production. To illustrate, it is very manipulable and comes in a variety of genetic families; it has many readily available deletion strains, a lot of molecular tools, a quick generation cycle, is simple to cultivate, and has a history of success in a variety of uses in industry [143,144,145]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that certain species, including the industrial wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae D5A, can produce more than 20% of stored lipids from glucose under nitrogen-limited culturing [146].

Yeasts, especially oleaginous yeasts, can produce large amounts of lipids, thus it is beneficial to harness this capacity to increase and/or alter the structure of algal lipids. To increase the biomass and lipid content of Trichosporonoides spathulate (a yeast), it was co-cultivated with three microalgal Chlorella spp. species. The findings revealed a notable variation in the composition of FAs and a 1.6-fold increase in lipid content as well as the overall biomass compared to the yeast pure culture after 48 h of cultivation. Briefly, Linoleic acid (19.16%), palmitic acid (17.96%), and oleic acid (48.91%) made up the majority of the yeast’s lipid, whereas oleic acid made up most of the Chlorella spp. lipids (37.49%), followed by palmitic acid (32.32%) and linoleic acid (15.69%).

Compared to the lipids from the pure cultures, mixed culture had higher amounts of saturated fatty acids, involving stearic acid (17.15%), oleic acid (21.30%), and palmitic acid (40.52%). The constituents of this yeast and microalgal lipid is comparable to that of plant oil, suggesting that it could be used as a feedstock bioprocesses like biodiesel [112].

Another study cultured the microalgae Spirulina platensis with the yeast Rhodotorula glutinis to enhance lipids yield. The results demonstrated that co-culturing can significantly boost the accumulation of total lipid yield and biomass. Compared to pure cultures, the mixed cultivation yielded the maximum total lipid production of 467 mg/L, which was 3.18- and 3.92-times of R. glutinis and S. platensis biomasses, respectively [147].

Commercial enzymes, vitamins, and important medicinal polypeptides have all been produced using yeast with efficiency. Furthermore, these eukaryotic cells are becoming a flexible host to produce lipid molecules with significant industrial significance, such as phospholipids, ceramides, fatty acids, and sterols. Research attention has switched to the use of lipids for preventing and treating illnesses as well as the promotion of healthy lifestyles due to the increased knowledge of their impact on human metabolism and health. A wide variety of lipid molecules have been developed recently by metabolic engineering or biotransformation techniques [148].

However, a lot of research on fermentation/transformation still focuses on using S. cerevisiae to consume carbohydrates (from algae or other sources) rather than lipids in order to produce biofuel like biodiesel, bioethanol [149,150,151] as well as chemicals such as isoprenoids and organic acids [152].Therefore, more research is needed to investigate this yeast’s potential to transform algal lipids into more valuable and functional molecules. S. cerevisiae can be a promising chassis to produce functional lipids using nutrients derived from algae because of its well-characterized and detailed lipid pathways, high production rate, accelerated life cycle, and track record of success in numerous applications.

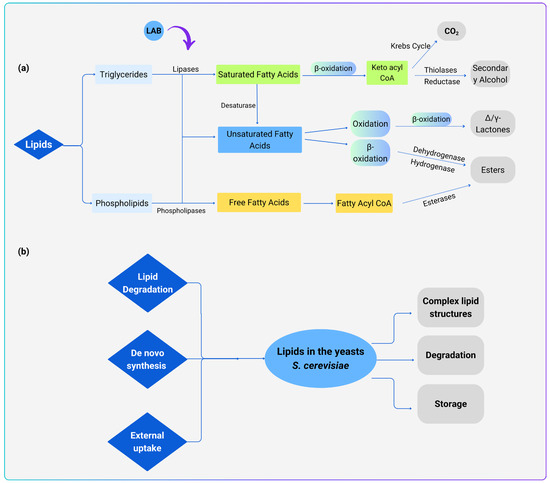

6. Potential Transformation of Microalgal Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs)

Fatty acid (FA) identification and analysis in microalgae is becoming more popular and helps to identify new molecules with various functional groups. Figure 4a illustrates the LAB mediating the lipid metabolism pathway. Lipase and phospholipase work to produce free fatty acids (FFAs) from triglycerides and phospholipids, with phospholipids serving as the primary source of FFAs involving both saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. FA-desaturase converts some saturated fatty acids into unsaturated fatty acids, β-oxidation is responsible for converting some saturated fatty acids into ketoesteryl CoA, thiolytic enzymes convert ketoesteryl CoA into acetyl CoA and β-keto acids, β-ketoacyl decarboxylase converts β-keto acids into methyl ketones, and reductase converts them into secondary alcohols. Acetyl CoA then enters the metabolism of sugars and lipids, and is ultimately oxidised and broken down into hydrocarbons, ketones, aldehydes, and other aromatic products. 4/5-hydroxy acids and hydroperoxides are produced by oxidising unsaturated fatty acids, while esters are produced by further oxidising 4/5-hydroxy acids. Enzymes that hydroperoxide-cleave produce aldehydes from hydroperoxides, whereas hydrogenases and dehydrogenases convert aldehydes into acids and alcohols. Additional esterification processes then produce esters. On the contrary, esterase, a bifunctional enzyme that can hydrolyze triglycerides to produce fatty acids, directly converts FFAs into fatty acyl CoA and produces esters [153]. For example, Lactilactobacillus plantarum can function as a producer of lipase to break down lipid and facilitate esterification to create short-chain fatty acids like 2,3,4-hydroxybenzyl acetate [154].

In the yeast, lipid metabolism is a big topic and can be divided into three categories: fatty acids, storage lipids and membrane lipids. FAs are fundamental components of complex lipids. Triacylglycerols (TG) and steryl esters (SE) stored in lipid droplets (LD) can contain them as an energy reservoir, or they can be integrated into phospholipids and sphingolipids. Carboxylic acids with hydrocarbon tails that vary in length and degree of unsaturation are known as free fatty acids. These differences result in a wide range of FAs and, consequently, the production of several lipid classes. FAs can enter S. cerevisiae cells through (1) de novo synthesis, (2) complicated lipid hydrolysis and protein delipidation, or (3) FA intake from outside sources [155] (Figure 4b). FA synthesis by De novo production in the cytosol and mitochondria, then they undergo elongation and desaturation in the endoplasmic reticulum. The acyl-CoA D9-desaturase Ole1p is responsible for adding double bonds to the acyl chains and then desaturating them [156]. However, as mentioned earlier, it can only add two double bonds. Lipotoxicity can occur in S. cerevisiae due to an overabundance of cellular lipids, which can be detrimental to the cell. Thus, lipids are kept in specialised organelles (LD) to counteract this undesirable consequence. Later, these stored lipids can be released when needed for complicated lipid synthesis or energy production [157]. Klug and Daum (2014) had widely discussed the lipid metabolism in S. cerevisiae, covering lipid synthesis, degradation, and storage, as well as the function of enzymes in controlling crucial stages of the many lipids metabolic pathways and the connection between lipid metabolic and dynamic processes [157].

Because of their structural diversity and increased significance as a result of their taxonomic specificity, FAs are the most significant constituents of microalgae strains. Based on their carbon numbers, microalgal FAs are divided into two categories: PUFAs (with more than 20 carbons) are utilized in nutraceutical and pharmaceutical applications. In contrast, fatty acids with 14–20 carbons are used to produce biodiesel.

PUFAs contain several double bonds in their lengthy carbon chain architecture, and the two types of PUFAs, ω-6 and ω-3, are made from linoleic acid and linolenic acid, respectively. Furthermore, the vital ω-3 FAs include α-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6), whereas the ω-6 FAs are γ-linoleic acid and arachidonic acid (ARA). Microalgae have been demonstrated to be a promising potential source of these important FAs [158,159].

A variety of microalgae can accumulate more than 20% of their FAs in the form of omega-3-long chain PUFAs. PUFAs are esterified with an alcohol, typically glycerol, in microalgal cells to produce TAGs or polar lipids (phospholipids, glycolipids) with remarkable structure that control the fluidity and function of membranes. Relying on the microalgae species, the industrial synthesis of lipids can be coupled with the synthesis of other value-added by-products including astaxanthin and beta-carotene to foster process profitability [160].

Figure 4.

(a) LAB and yeasts mediated lipid metabolism pathways, modified from Xia et al. (2023) [153]. Doted arrows indicate more than one process or subsequent steps, while solid arrows indicate one process. (b) Lipid metabolism pathways in yeast S. cerevisiae. The synthesized FAs can be integrated into storage lipids or complex membrane lipids or degraded by beta-oxidation. Enzymes catalysing these processes are discussed in detail in the study by Klug and Daum (2014) [157].

However, the primary weakness of employing microalgae to manufacture PUFA-rich lipid on a large scale is the low lipid content and the low biomass density in the reactor, which typically does not surpass 400–600 mg/L under commercial growing settings. This significantly raises the cost of harvesting [161]. This low lipid (PUFAs) content of microalgae can, alternatively, be utilized indirectly in the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical sectors following a microbial biotransformation process to create more valuable and functional PUFAs molecules. Microbial strains also provide easier engineering, faster growth, increased productivity, and the ability to produce significant levels of novel and distinctive lipid molecules.

Numerous microbial strains exhibit potential for producing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) as well as serving as a catalyst to bio-transform them into distinct molecular structures like conjugated fatty acids. As a new class of functional lipids that are biologically active, these molecules have received much interest [162]. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), for instance, is anticipated to be a possible substance in medications and nutritional supplements. CLA lowers body fat, atherosclerosis, and carcinogenesis.

A study that screened microbial reactions useful for producing CLA discovered that LAB formed CLA from linoleic acid, which was acquired as the free FA form and consisted of a combination of trans-9, trans-11-18:2 and cis-9,trans-11-octadecadienoic acid (18:2). LAB also converted ricinoleic acid [12-hydroxy-cis-9-octadecenoic acid (18:1)] to CLA, which is a combination of trans-9, trans-11-18:2 and cis-9, trans-11-18:2. It was also discovered that castor oil, which is high in the triacylglycerol (TAG) form of ricinoleic acid, can serve as a substrate for LAB to produce CLA through the hydrolysis of TAG, which is triggered by lipase. α- and γ-linolenic acid were also converted into conjugated trienoic fatty acids by LAB. The authors concluded that microbial strains exhibit unique FA biotransformation processes, including isomerization, dehydration, and desaturation, all of which are effective for conjugated FA manufacturing [163].

Another study produced CLA from linoleic acid using Lactobacillus acidophilus AKU 1137 in a microaerobic system. After a four-day incubation period, the results demonstrated that LAB could convert over 95% of the supplied linoleic acid into CLA, and the amount of CLA in the total FAs recovered surpassed 80% (w/w). Nearly all the CLA generated was either present in the cells or was connected to them as free FAs [164].

The metabolic response of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to linoleic acid (LA) was investigated utilizing metabolomics and isotope labelling techniques. It was found that the use of LA by S. cerevisiae significantly affected the primary carbon metabolism. Under anaerobic conditions, LA promotes the consumption of glucose and the synthesis of ethanol. Consequently, the cell’s energy state was impacted, and there was an up-regulation of the TCA cycle, the generation of amino acids and the glycolytic pathway. Interestingly, even in anaerobic conditions, the researchers noticed that linoleic acid was carried into the cell and transformed into other fatty acids, influencing their composition. Briefly, the authors found 64 intracellular metabolites, involving FAs, amino acids, and TCA cycle intermediary molecules in S. cerevisiae. Central carbon metabolism was influenced by LA and CLA administration.

Researchers monitored the biotransformation of LA inside S. cerevisiae under both anaerobic and aerobic settings using 13C-labeled LA. Even in anaerobic settings, the yeast mostly converted LA into oleic (56.5%) and palmitoleic (53.9%) acids, indicating an unknown mechanism for β-oxidation in oxygen-constrained settings [165]. However, this process has not yet been found in S. cerevisiae, even though some microorganisms, like E. coli, have evolved unique anaerobic β-oxidation pathways by using alternative electron transport chains with different terminal electron acceptors such as nitrate [166]. Moreover, Schizosaccharomyces pombe was found to increase the amount of oleic acid while decreasing stearic acid amounts under anaerobic conditions during ethanol stress, despite the fact that it is known that FA desaturation is inhibited in most yeasts under anaerobiosis. However, the opposite was seen when oxygen was existing [167]. Furthermore, PUFAs were found, particularly eicosadienoic acid, α-linolenic acid, and a conjugated linoleic acid isomer. S. cerevisiae does not have the desaturase to convert LA to ALA (a fatty acid with three double bonds), it only has OLE1 gene that is not capable of producing polyunsaturated fatty acids with more than two double bonds. Accordingly, the researchers have attributed this conversion to whether the CLA synthesis in S. cerevisiae may be mediated by an unexplored enzyme (isomerase) or an oxygen-independent desaturation process. They further confirmed they proposition by the fact that S. cerevisiae lacks the desaturase and that the desaturation process involves molecular oxygen, confirming that strict precautions have been taken to ensure zero oxygen leak in the flasks [165]. Notwithstanding these results about the synthesis of fatty acids in yeasts during anaerobiosis, no additional research has been performed in this field, thus more research is required to verify that yeasts are capable of synthesising fatty acids in anaerobic environments.

7. Biotransformation of Pigments in Microalgae via Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation

Microalgae are a diverse group of photosynthetic microorganisms that thrive in aquatic environments and are increasingly valued for their rapid growth, efficient carbon dioxide utilization, and rich biochemical profiles. They serve as sustainable sources of proteins, polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, and various bioactive compounds, notably pigments such as chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins. These pigments not only contribute to photosynthesis and photoprotection but also offer health benefits and natural colorants for foods [168,169]

However, the direct use of microalgal biomass in food products is often limited by the presence of strong, undesirable flavors and rigid cell walls, which reduce digestibility and bioavailability [170,171]. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermentation has emerged as a promising method to overcome these challenges by improving sensory qualities, enhancing nutritional value, and increasing the release of functional compounds [57,169,172,173,174].

During LAB fermentation, metabolic activities such as carbohydrate conversion to lactic acid result in pH reduction and enzyme production, which can significantly affect the stability, structure, and extractability of microalgal pigments. These biotransformations influence the color, sensory profile, and health benefits of the final products. Understanding the responses of chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins to fermentation across different species and processing conditions is crucial for optimizing microalgae-based functional foods and beverages.

8. Overview of Microalgal Pigments

Microalgae possess a diverse array of pigments essential for their survival and photosynthetic activity. These pigments can be broadly categorized into three main classes: chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins, each contributing unique colors and functionalities. Chlorophylls, primarily chlorophyll a and b, are the principal pigments responsible for capturing light energy for photosynthesis and impart the characteristic green color to many algae and plants. Their concentration and type can vary significantly depending on the algal species and cultivation conditions, such as phototrophic versus heterotrophic growth [171].

Chlorophylls are often implicated in the undesirable grassy or fishy off-flavors associated with microalgal biomass, making their fate during processing a key consideration for food applications [175]. Carotenoids constitute another major group, acting as accessory light-harvesting pigments and providing crucial photoprotection against excess light energy and oxidative stress through their antioxidant capabilities. This class includes pigments like β-carotene (pro-vitamin A), astaxanthin (a potent antioxidant often found in Haematococcus pluvialis), lutein, and fucoxanthin (characteristic of brown algae). They contribute a spectrum of colors ranging from yellow and orange to red. The stability of carotenoids during processing, including fermentation, is variable and depends on the specific carotenoid structure and the processing conditions employed.

Phycobiliproteins are unique, water-soluble pigment-protein complexes found predominantly in cyanobacteria (like Arthrospira platensis, known as Spirulina) and red algae. This class includes phycocyanin (blue), phycoerythrin (red), and allophycocyanin (blue-green). These pigments serve as highly efficient accessory light-harvesting antennae and are also recognized for their potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other health-promoting properties. However, the stability of phycobiliproteins during processing techniques like fermentation may be impacted by their sensitivity to environmental conditions like pH, temperature, and light [57].

9. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentation of Microalgae

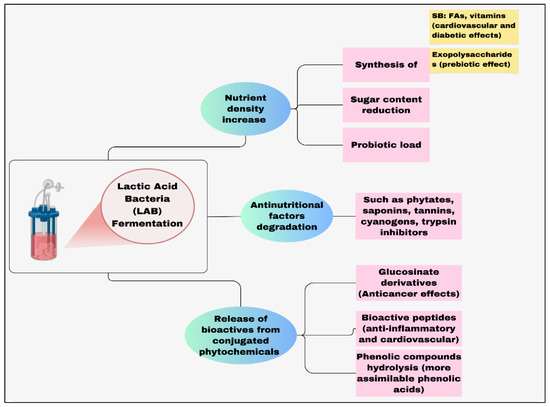

LAB fermentation is an age-old biotechnology employed for food preservation and the enhancement of sensory and nutritional qualities (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermentation on altering organic compounds such as food components. SB: Secondary metabolites, FAs: Fatty acids [50].

The process primarily involves the conversion of carbohydrates present in the substrate into lactic acid by LAB, resulting in a significant decrease in pH. Depending on the LAB species and strain, fermentation can be homofermentative (producing mainly lactic acid) or heterofermentative (producing lactic acid along with other metabolites like acetic acid, ethanol, and carbon dioxide).

Common LAB species utilized in food fermentations, including those applied to microalgae, belong to genera such as Lactiplantibacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Lactobacillus, and Leuconostoc [169,171] (Table 4). Microalgal biomass, with its rich composition of carbohydrates and proteins, serves as a suitable substrate for the growth and metabolic activity of LAB [57,171]. Fermenting microalgae with LAB offers several potential benefits. It can significantly improve the sensory profile by reducing or masking the characteristic off-flavors often associated with raw biomass [171]. Fermentation can also enhance the consumption of the microalgal components, potentially by partially breaking down intricate cell wall structures [57].

Table 4.

Fermentation-assisted valorization of microalgae biomass using different lactobacillus strains.

Furthermore, LAB fermentation has been shown to increase the bioactivity of microalgal biomass, including antioxidant capacity, which may result from the release of bioactive compounds, the transformation of existing compounds, or the production of new metabolites by the bacteria [57,169]. The mechanisms underlying these changes involve not only acidification but also the enzymatic activities of LAB (e.g., proteases, lipases, glycosidases) and potentially the activation of endogenous algal enzymes, leading to complex biochemical transformations within the biomass matrix [57].

10. Biotransformation of Microalgal Pigments During LAB Fermentation

The interaction between LAB and microalgal biomass during fermentation initiates a cascade of biochemical changes that significantly impact the native pigment composition. These transformations are driven by factors such as pH reduction due to organic acid production, enzymatic activities originating from both the LAB and potentially the algae themselves, and changes in the redox environment. The extent and nature of pigment biotransformation affected by the particular pigment class, the microalgal species, the LAB strains employed, and the conditions of fermentation [57,169,173].

10.1. Effects of Biotransformation on Chlorophylls

Chlorophylls, the ubiquitous green pigments, are often susceptible to degradation under the acidic conditions generated during LAB fermentation. The drop in pH can lead to the non-enzymatic conversion of chlorophylls into their derivatives. One common pathway involves the displacement of the central magnesium ion by protons, forming pheophytins, which typically exhibit an olive-brown color. Further degradation, potentially involving the enzymatic cleavage of the phytol tail by chlorophyllase enzymes (either endogenous to the algae or produced by LAB, though LAB chlorophyllase activity is less common), can yield pheophorbides.

These degradation processes contribute to a loss of the vibrant green color and can potentially mitigate the grassy off-flavors often associated with chlorophyll-rich biomass [171,175]. Studies focusing on the aroma profile of fermented Chlorella vulgaris have indicated a substantial reduction in composites responsible for off-flavors, like hexanal, which, while not directly measuring chlorophyll, supports the hypothesis that fermentation modifies components contributing to undesirable sensory notes, potentially including chlorophylls or their breakdown products [171]. Furthermore, observations of color shifts, such as from green to red during the fermentation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, strongly suggest substantial chlorophyll degradation, unmasking or revealing other pigments like carotenoids.

10.2. Effects of Biotransformation on Carotenoids

Carotenoids, known for their antioxidant properties and yellow-to-red colors, exhibit variable stability during LAB fermentation. The acidic environment can promote isomerization (e.g., conversion between trans and cis forms) or degradation of certain carotenoids. However, the overall impact is complex. In some cases, fermentation might enhance the extractability or apparent concentration of carotenoids. This could occur through the partial breakdown of the algal cell–matrix by LAB enzymes, making the pigments more accessible. The observed color shift from green to red in fermented Chlamydomonas could be partly attributed to the increased relative concentration or visibility of carotenoids as chlorophyll degrades [57,169].

While fermentation aims to improve overall product quality, the specific impact on the profile and bioactivity of valuable carotenoids like astaxanthin or lutein requires careful evaluation in each specific microalga-LAB system. The overall antioxidant capacity of fermented microalgae has been reported to increase in some studies, even when certain pigments degrade, suggesting a complex interplay where the formation or release of other antioxidant compounds (like phenolics) might compensate for or outweigh pigment loss [57].

10.3. Effects of Biotransformation on Phycobiliproteins

Phycobiliproteins, particularly phycocyanin found in cyanobacteria like Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina), are known to be relatively sensitive to processing conditions, especially pH and temperature. Research on the LAB fermentation of A. platensis has provided direct evidence of significant phycocyanin transformation. Niccolai et al. (2020) reported a substantial decrease, averaging around 40% [57], in phycocyanin content after 72 h of fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. This degradation is likely driven by the acidic conditions developed during fermentation, potentially coupled with enzymatic activity.

The loss of phycocyanin impacts the characteristic blue color of Spirulina extracts and may alter the profile of its associated bioactivities. Despite this pigment loss, the same study observed an increase in the overall in vitro and in vivo antioxidant action of the fermented product, highlighting that fermentation induces multifaceted changes in the biomass, potentially releasing or generating other antioxidant compounds that contribute to the enhanced functional properties [57]. This underscores the need to consider the net effect of fermentation on the overall bioactivity profile, rather than focusing solely on the stability of a single pigment class.

10.4. Factors Influencing Pigment Biotransformation

The extent and specific pathways of pigment biotransformation during the LAB fermentation of microalgae are influenced by a complex interplay of factors related to the feedstock, the microorganisms, and the process settings [180]. Understanding these parameters is crucial for controlling and optimizing the fermentation outcome in terms of pigment stability, color development, and overall product quality. One primary factor is the microalgal species itself.

Different species possess unique biochemical compositions, varying pigment profiles (e.g., Chlorella rich in chlorophylls, Spirulina rich in phycocyanin, Haematococcus rich in astaxanthin), and distinct cell wall structures. The inherent stability of the pigments and the accessibility of intracellular components to LAB enzymes or acidic conditions can differ significantly between species. The choice of LAB strain(s) is another critical determinant [181].

Different species of LAB and even strains within the same species demonstrate diverse metabolic capabilities. This includes variations in the rate and extent of acid production (influencing pH drop), the profile of organic acids produced (lactic vs. acetic), and the repertoire of enzymes they secrete (e.g., glycosidases, proteases, potentially enzymes acting on pigments). Some strains might be more effective at degrading certain pigments or releasing bioactive compounds than others [171].

Fermentation conditions play a pivotal role. Temperature affects LAB growth rates and enzymatic activities. The duration of fermentation determines the extent of microbial growth, acid accumulation, and enzymatic action [57]. The starting pH and the medium’s buffering ability influence the final pH achieved. Oxygen availability can impact both LAB metabolism (facultative anaerobes) and the oxidative stability of pigments. The composition of the fermentation medium, including the microalgal biomass concentration and the potential addition of supplementary carbohydrate sources, also affects LAB growth and metabolic output.

Finally, biomass pre-treatment methods applied before fermentation can influence pigment transformation. Techniques such as drying (method and temperature), cell disruption (e.g., homogenization, sonication), or enzymatic pre-treatment can alter the initial state of the pigments and the structure of the algal matrix, thereby affecting their susceptibility to changes during subsequent fermentation.

11. Potential Outcomes and Applications of Biotransformation of Microalgae

The biotransformation of pigments during LAB fermentation of microalgae leads to various outcomes with significant implications for food applications. A primary driver for fermenting microalgae is the improvement of sensory properties and the other factors affecting customer acceptance, as seen in Table 5. The degradation of chlorophylls and potentially other volatile compounds contributing to off-flavors can lead to a more neutral or even pleasant taste profile, facilitating the integration of microalgal biomass into a wider range of food produce [57]. Fermentation can also lead to enhanced bioactivity.

Table 5.

Factors influencing consumer acceptance of microalgae-based products.

While some pigments like phycocyanin may degrade, the overall antioxidant capacity of the fermented biomass can increase, as observed in fermented Spirulina [57]. This enhancement might stem from the release or increased bioavailability of other antioxidant compounds (e.g., phenolics, carotenoids) due to cell–matrix breakdown, the transformation of pigments into derivatives with altered activity, or the production of bioactive metabolites by the LAB themselves.

The changes in pigment profiles inevitably result in modified color characteristics. The loss of green from chlorophyll degradation or blue from phycocyanin degradation, potentially accompanied by the unmasking or relative increase in yellow/orange/red carotenoids, can substantially modify the visual appearance of the final produce. This needs to be considered depending on the desired aesthetic attributes of the food application.

Ultimately, LAB fermentation offers a pathway to develop novel functional ingredients from microalgae. Fermented biomass with improved flavor, enhanced digestibility, potentially boosted bioactivity, and modified pigment profiles can be utilized in formulating functional foods, beverages (like the lactose-free options explored by Niccolai et al. (2020), supplements, and feed ingredients, adding value beyond the nutritional contribution of the raw biomass [57].

12. Future Perspectives

Lactic acid bacteria fermentation represents a valuable and versatile tool for modifying microalgal biomass, offering significant potential to enhance its suitability for food applications. This review has synthesized current understanding regarding the biotransformation of key pigment classes—chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins—during this process. The evidence indicates that fermentation induces notable changes in pigment profiles, driven primarily by acidification and enzymatic activities.

Chlorophylls often undergo degradation, potentially leading to reduced green color intensity and mitigation of associated off-flavors, a significant advantage for sensory acceptance. Carotenoid stability appears variable, with possibilities for degradation, isomerization, or enhanced extractability depending on the specific conditions and algal matrix. Phycobiliproteins, such as phycocyanin in Spirulina, can experience significant degradation under fermentation conditions, impacting color and potentially specific bioactivities, although overall antioxidant capacity may still increase due to other biochemical changes.

The outcomes of pigment biotransformation are impacted by a confluence of factors, including the choice of microalgal species, the specific LAB strains employed, fermentation parameters (temperature, time, pH), and any pre-treatment applied to the biomass. These transformations have direct consequences for the final product’s characteristics, leading to modified colors, improved sensory profiles, and altered bioactivity landscapes.

The ability to modulate these changes through careful selection of strains and process optimization opens avenues for developing novel microalgae-based functional ingredients tailored for specific applications in foods, beverages, and supplements. While progress has been made, further research is warranted to fully elucidate the complex mechanisms underlying pigment biotransformation during microalgal fermentation.

Detailed studies correlating specific enzymatic activities of LAB strains with pigment degradation pathways are needed. Investigating the influence of fermentation on the bioavailability and bioactivity of various pigment derivatives (e.g., chlorophyll degradation products, carotenoid isomers) is also crucial. Moreover, exploring synergistic effects of LAB fermentation combined with other processing techniques could unlock new possibilities. Continued research in this area will be vital for harnessing the full potential of LAB fermentation to create value-added, sensorially appealing, and nutritionally enhanced products from sustainable microalgal resources.

13. Biotransformation of Microalgal Pigments During Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentation

The fermentation of microalgal biomass by Saccharomyces cerevisiae initiates a chain of metabolic changes that significantly change the native pigment profile of microalgae. This process is crucial for enhancing the nutritional, functional, and sensory features of microalgae-based products, making them more suitable for food and nutraceutical applications, and biofuel production [55,59].

13.1. Mechanisms of Pigment Biotransformation

Microalgal cell walls are made of robust polysaccharides and glycoproteins that limit the release of intracellular pigments such as chlorophylls and carotenoids. During fermentation, S. cerevisiae secretes hydrolytic enzymes and produces ethanol, both of which facilitate the breakdown of these cell walls, thereby liberating pigments into the fermentation medium [55,59]. Pre-treatments like microwave irradiation can further enhance pigment extractability [61].

The metabolic processes of S. cerevisiae lead to the synthesis of organic acids and ethanol, causing a drop in pH and changes in the redox environment. Acidic conditions promote the conversion of chlorophylls to pheophytins and pheophorbides, resulting in a visible color shift from green to olive or brown hues and reducing the bioactivity of chlorophylls. Carotenoids may undergo isomerization (trans to cis forms) or oxidative degradation, but the breakdown of the cell–matrix can increase their extractability and apparent concentration [61]. Ethanol produced by yeast acts as a solvent for hydrophobic pigments, facilitating their extraction and increasing their bioavailability in the final product [59,61,185].

13.2. Specific Pigment Transformations

Chlorophylls are highly sensitive to acidic and oxidative environments. During fermentation, they are converted to pheophytins and pheophorbides, leading to a color shift from green to olive or brown. These transformations reduce the antioxidant activity of chlorophylls but can improve the digestibility and sensory properties of the biomass [55,186].

Carotenoids such as β-carotene [187], lutein [188], and astaxanthin [97] are valued for their antioxidant features and vibrant yellow-to-red hues. Although fermentation can cause partial breakdown or isomerization of carotenoids, ethanol presence and cell wall rupture commonly improve their extractability and bioavailability. The overall impact on carotenoid content is complex: while some loss may occur due to degradation, the enhanced release from the cell–matrix can result in higher measurable levels in the product [55,59].

The water-soluble pigments, mainly present in cyanobacteria and red algae, are susceptible to proteolytic degradation during fermentation [58,189,190,191]. While S. cerevisiae does not produce high levels of proteases, acidification and cell wall disruption can reduce phycobiliprotein stability, leading to color loss and diminished bioactivity [55,192].

13.3. Functional and Nutritional Implications

Enhanced release of carotenoids and formation of certain chlorophyll derivatives can increase the antioxidant potential of fermented microalgae-based products [59,193]. Digestibility and Bioavailability: The breakdown of cell walls and release of intracellular nutrients improve the digestibility and nutritional value of the biomass [55,88].

Reduction in chlorophyll content and increased carotenoid visibility result in more appealing colors and milder flavors, which are important for consumer acceptance [55]. The simultaneous production of bioethanol and value-added pigments during fermentation supports the bio-refinery concept, maximizing economic and environmental benefits [59].

13.4. Applications and Recent Advances

Fermented microalgal products are being developed as functional foods and dietary supplements, with improved pigment profiles and enhanced health benefits [55,59]. Enhanced lipid and pigment extraction during fermentation supports efficient biofuel production from microalgal biomass [55]. Biorefinery Integration: Multi-product biorefineries utilize S. cerevisiae fermentation to simultaneously produce bioethanol, pigments, and other high-value compounds from microalgae [59].

14. General Challenges and Future Perspectives and Regulations of Using Fermented Spirulina in Food Sector

Maintaining the stability of sensitive pigments during fermentation and downstream processing remains a challenge [55]. The choice of pre-treatments, fermentation parameters (temperature, pH, and duration), and yeast strains can significantly influence pigment outcomes. Variability in microalgal species, cultivation conditions, and biomass composition necessitates robust standardization protocols for consistent product quality. Ongoing research is focused on developing targeted fermentation strategies, including the use of genetically engineered yeast strains and integrated bioprocessing, to further enhance the value of microalgal pigments in food, feed, and health-related industries.

Foods derived from microorganisms, such as microalgae-based products, require precise organism identification and confirmation of safety status. Similarly to the USA’s Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) designation, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) established a concept in 2007 referred to as Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS), which differs slightly by assigning the decision-making authority to risk assessors rather than to food business operators (FBOs) [194].