Abstract

Incidental capture (bycatch) is a major threat to all seven marine turtle species worldwide. This systematic review assessed (i) research trends over the past 20 years; (ii) relationships between fishery types, gear, and species caught; (iii) post-capture outcomes; and (iv) challenges in bycatch mitigation. A systematic search of Web of Science and Scopus up to April 2024 identified 236 studies, comprising 336,616 global bycatch records. Publications on turtle bycatch increased significantly (p < 0.001), peaking in 2020. Reported captures also rose (ρ = 0.45; p = 0.026), with Caretta caretta most frequently documented (74.8%). Methodology influenced outcomes: aerial monitoring and direct observation underestimated captures of Chelonia mydas, Lepidochelys kempii, and Eretmochelys imbricata compared with mixed methods; interviews only affected the latter. Regarding fishery interactions, Dermochelys coriacea was more susceptible to hook-and-line fishing (p = 0.0079), while C. mydas was more associated with small-scale fisheries (p = 0.0115). Most turtles were released after capture (60.6%), with no significant temporal variation in outcomes (p > 0.05). Despite growing monitoring, knowledge gaps remain in standardized reporting, regional and species coverage, and methodological integration. Addressing these issues is essential to guide effective, collaborative conservation strategies.

1. Introduction

Oceans play a central role in global socioeconomic development, providing essential ecosystem services such as climate regulation, food resources, and support for tourism and recreational activities [1,2]. Their biodiversity, which is fundamental to ecological balance, faces increasing pressures including overfishing, pollution, habitat destruction, and climate change, all of which accelerate the loss of marine species [3,4].

Fishing is one of the most widely practiced human activities in the oceans and plays a key role in the livelihoods of coastal communities, food security, and economies of millions of people [5,6]. According to FAO [7] data, 61.8 million people work in the primary fishing sector, 113 million are engaged in small-scale fisheries and 174.5 million in recreational fishing. However, this activity varies significantly in scale and method, generating distinct impacts [5,8].

Industrial fishing employs advanced technologies and operates on a large scale, resulting in high bycatch rates. In contrast, artisanal and recreational fishing, although locally important, often lacks effective regulation [9,10]. Regardless of the type, fishing activities can lead to ecological imbalances, such as overfishing and incidental capture of threatened species, including marine turtles [11].

Species such as Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758), Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758), and Lepidochelys kempii (Garman, 1880) are particularly vulnerable to bycatch in gear types such as longlines, gillnets, and trawls [12], all of which are listed as threatened [13]. Their incidental capture not only hinders population recovery, but also results in indirect mortality due to injuries and post-release stress [14]. In addition, the traditional use of their by-products persists in some regions, further intensifying the pressure on these species [15].

International initiatives, such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (COP15), aim to reverse this scenario by committing to protect 30% of the planet’s marine and terrestrial areas by 2030 [16]. However, unilateral measures focused on specific species or fisheries have shown limited effectiveness, and may lead to negative socioeconomic impacts [17]. Sustainable management requires integrated approaches that consider local complexities and trade-offs between conservation and livelihood [18]. In the scientific domain, studies have evaluated isolated mitigation factors, such as modifications to fishing gear or the establishment of protected areas, but have often neglected interactions between these factors [19,20]. Peer-reviewed publications are crucial for informing feasible policies and practices in the face of fragmented evidence [21].

Therefore, the interaction among these factors may be crucial for understanding bycatch dynamics and developing more effective mitigation measures. In this context, systematic reviews represent an essential tool for synthesizing fragmented evidence, enabling the integration and critical analysis of existing experimental and observational data [22]. Conducting such integrative analyses allows for the identification of appropriate solutions tailored to different ecological and socioeconomic contexts, supporting the implementation of more sustainable management and conservation strategies grounded in a holistic understanding of the impacts on sea turtles [23,24].

Accordingly, this review builds upon previous studies and aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of global data on sea turtle bycatch, examining temporal, methodological, and operational patterns across fisheries. As a systematic review, it seeks to: (i) quantify the evolution of scientific output, (ii) identify temporal trends in bycatch, (iii) compare frequencies across species and fishing methods, (iv) assess the effects of fisheries and gear types, and (v) examine post-capture outcomes. The results provide relevant input for the development of public policies and management strategies, contributing to the sustainability of fishing activities and conservation of marine ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review included empirical studies that addressed sea turtle bycatch in fisheries, regardless of oceanic region or methodology used. Both short- and long-term studies were eligible. We excluded reviews, book chapters, notes, letters, editorials, conference proceedings, preprints, abstracts, and data papers to focus on primary research reporting original data.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search in the Web of Science and Scopus databases up to April 28, 2024, using the search terms: “fishing” AND “sea” AND “turtle” AND “bycatch.” The search identified 830 documents. After removing duplicates (n = 196) and applying eligibility criteria (n = 89), 545 articles were manually screened.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

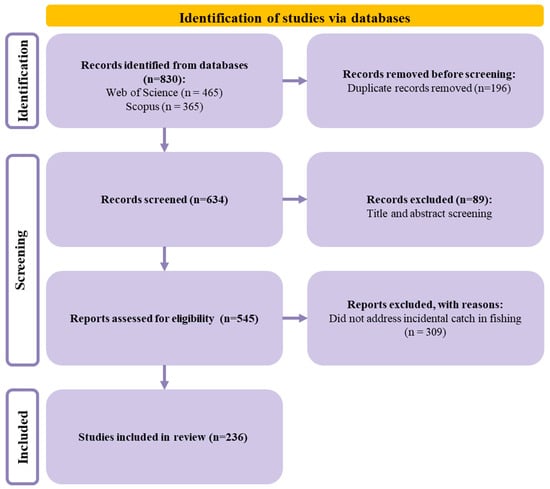

A total of 830 records were initially identified through database searches (Web of Science, n = 465; Scopus, n = 365). After removing 196 duplicate records, 634 unique studies remained for title and abstract screening. During this stage, 89 records were excluded for not meeting the predefined inclusion criteria. The remaining 545 full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility, resulting in the exclusion of 309 studies that did not specifically address incidental catch in fishing activities. Consequently, 236 studies met all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the final review (Figure 1 and Supplementary Material S1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the study selection process.

For each included study, data were extracted on the title, year of publication, methodology, fishery category, gear type, species caught, capture frequency, and fate of the captured animals.

The PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided as Supplementary Material S2 to ensure transparency and completeness in reporting the systematic review process.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

A formal risk of bias assessment was not performed due to the descriptive and integrative nature of this review. However, inclusion was limited to peer-reviewed empirical studies with clearly reported methodologies and data collection procedures. No data extrapolation or adjustment was conducted, preserving the integrity of the original data.

2.5. Data Organization and Processing

Analyses were conducted exclusively on reported data, without extrapolation, estimation, or standardisation of fishing effort, due to the high variability and frequent absence of effort-related information across studies. As a result, catch rates and spatial trends could not be reliably calculated. Instead, capture frequencies were analysed based on combinations of fishing gear and data structure, without applying corrections for gear-specific selectivity or sampling effort.

Fisheries were categorised into two main groups: Industrial Fisheries (n = 234) and Small-Scale Fisheries (SSF), the latter encompassing both artisanal (n = 90) and recreational (n = 11) fisheries, due to operational similarities. It is important to note that these values represent species-level bycatch records rather than study counts, as individual studies often reported multiple species captured under different fishery types.

Research methodologies were grouped into four categories (Table 1). Gear types were classified into three FAO-based categories (Table 2), and bycatch outcomes were organised into four thematic categories (Table 3).

Table 1.

Data collection methods used in studies on sea turtle bycatch.

Table 2.

Classification of fishing gear and associated fishing methods identified in the analyzed studies.

Table 3.

Categories of sea turtle bycatch outcomes based on the most frequently reported subcategories in the reviewed studies.

2.6. Statistical Analyses and Synthesis of Results

Scientific output over time was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, showing a non-normal distribution. Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to analyze the association between publication year and number of studies. A Poisson-distributed Generalized Linear Model (GLM) was fitted to assess publication trends, and segmented regression identified breakpoints and slope changes over time.

Spearman’s correlation was also used to examine the relationship between year and bycatch frequency. Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) evaluated effects of research methodology on bycatch frequency, with “Year” as a random effect. A separate GLMM assessed the effects of fishing gear and fishery category due to data heterogeneity.

A chi-square test examined associations between capture year and bycatch outcome categories using contingency tables. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.1; R Core Team, 2024). A complete list of R packages used is provided in Supplementary Material S3.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of Studies on Bycatch

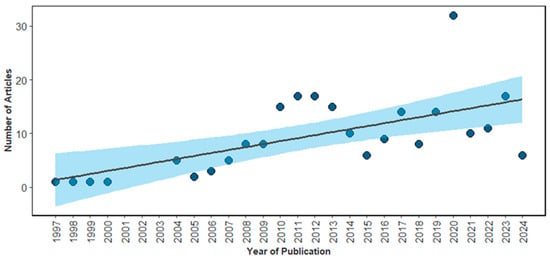

Based on the selected studies, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis indicated a positive and significant relationship between publication year and the number of articles on sea turtle by-catch (p < 0.05), highlighting a steady increase in scientific output over the analyzed period. Moreover, an intensification of the trend line was observed starting in 2010 and peaking in 2020 (n = 32 publications) (Figure 2). The results of the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) revealed an average annual increase of 6.7% in publications (Estimate = 0.065; p < 0.001), with segmented regression indicating a significant breakpoint in 2010.63 (~2011) and a subsequent reduction in the slope of the curve (Estimate before = 0.23; after = −0.24), demonstrating a deceleration in the growth rate.

Figure 2.

Number of articles on bycatch of sea turtles published between 1997 and 2024. The solid black line represents the linear trend over time, with the shaded area indicating the confidence interval of the regression model. The dots represent the number of publications per year.

The increase in scientific output on sea turtle bycatch, particularly after 2010, reflects the convergence of institutional and political efforts in favor of marine conservation and the prioritization of conservation strategies for these animals, especially focusing on Regional Management Units [25]. The adoption of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets in 2010 was a key milestone, establishing international commitments such as the protection of coastal and marine areas by at least 10% by 2020, thereby encouraging research aimed at the sustainable management of marine resources [26,27,28]. During the same period, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) released voluntary guidelines for bycatch management, promoting the use of selective fishing gear and standardization of bycatch data collection, which also fostered new research initiatives [29,30,31]. The Manila Declaration (2011) reinforced the integration of ecosystem-based approaches into fisheries policy, while the United Nations-led World Ocean Assessment (2015) identified bycatch as one of the main threats to marine biodiversity, elevating the issue’s visibility on the international scientific agenda [32,33].

Since 2017, negotiations surrounding the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Treaty have placed high sea conservation at the forefront of global debate [34]. In parallel, technological advances in fishery monitoring, the expansion of marine protected areas, and growing public awareness of fishing impacts have all contributed to the intensification of research on bycatch mitigation [35,36,37,38]. Thus, the observed growth in publications not only reflects increased scientific attention to the issue, but also a global context that is more conducive to the adoption of sustainable marine management policies.

3.2. Temporal Patterns in Sea Turtle Bycatch

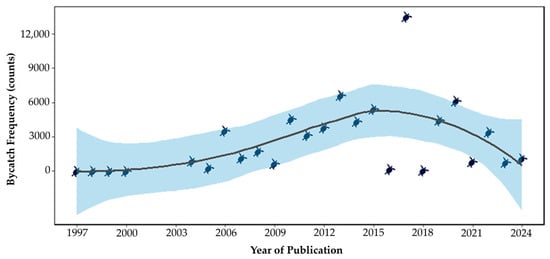

Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a moderate positive association between the year and the number of recorded sea turtle bycatch events (ρ = 0.45; p = 0.026), suggesting a significant increase in reported cases over time (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between publication year and reported sea turtle bycatch. The figure shows the temporal trend in the number of individual turtles reported as bycatch in scientific publications from 1997 to 2024. The solid line represents the fitted trend, and the shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval. Each point corresponds to the number of individuals reported in a given study. Y-axis values are presented in raw counts (not log-transformed).

From a fisheries perspective, this increase may reflect the intensification of global fishing efforts, driven by both the expansion of industrial fisheries and the growing participation of small-scale fisheries, particularly in the coastal areas of tropical countries [39]. Although global fish production has stabilized since the late 1980s [40], fishing efforts have continued to increase [41], increasing the spatial overlap between fishing activities and critical sea turtle habitats [42,43]. Advances in monitoring technologies and systematization of data have also contributed to the improved reporting of these interactions in recent years [37,44].

In parallel, an increase in the number of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing nets, called ghost nets, represents a growing threat to marine fauna, including sea turtles [45,46]. Millions of tons of fishing gear are estimated to enter the oceans annually, with many remaining active for years, continuing to entangle marine species [47,48]. This issue is exacerbated by structural failures in waste management systems and the enforcement of public policies that promote recycling and safe disposal of fishing gear [49,50]. The continued release of such materials into marine ecosystems contributes to the increase in unintentional capture [51] and underscores the urgent need for integrated strategies involving fisheries management, waste collection, and marine conservation.

3.3. Proportion of Bycatch by Sea Turtle Species

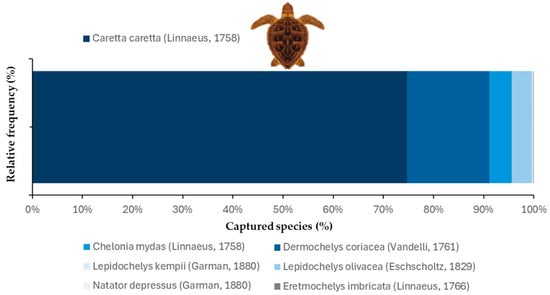

Among the sea turtles recorded in the analyzed studies (n = 336,616), Caretta caretta was the most frequently captured species, accounting for 74.8% of the total (n = 251,742). It was followed by Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761), which represented 16.4% (n = 55,352), while Chelonia mydas and Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829) accounted for 4.4% (n = 14,791) and 4.0% (n = 13,465) of the bycatch, respectively. The remaining species, Lepidochelys kempii (0.3%, n = 1009), Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766) (0.1%, n = 337), and Natator depressus (Günther, 1867) (0.005%, n = 17), were recorded in much lower proportions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proportion of sea turtle species captured, as recorded in the studies analyzed. The figure shows the relative frequency (%) of each species reported in by-catch records across the reviewed studies. The x-axis represents the percentage of total capture records, and the y-axis shows the frequency distribution.

Although extensively studied, particularly in the Mediterranean [52], the loggerhead turtle (C. caretta) continues to face major conservation challenges, largely because of its high susceptibility to bycatch across various fishing methods [53,54,55]. This vulnerability is linked to life-history traits, including ontogenetic shifts between oceanic and coastal habitats [56], with strong fidelity to migratory routes, foraging grounds, and overwintering areas [57]. The demersal phase, during which individuals inhabit shallow waters at depths less than 100 m, is particularly critical, as it increases the spatial overlap with zones of intense fishing activity, such as pelagic and bottom longlines and trawl fisheries [58,59]. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that these habitat shifts are reversible [60,61], and migratory behavior exhibits intra- and inter-annual variability linked to reproductive factors [62], further complicating bycatch risk prediction and management.

Despite advances in the understanding of species’ ecological traits, initiatives to reduce bycatch remain insufficient [63]. Studies indicate that simple measures, such as replacing J-hooks with circle hooks and substituting squid bait with alternative species, such as Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus Linnaeus, 1758), can reduce C. caretta bycatch by up to 90% [64,65,66]. Additionally, the use of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in trawl nets has shown moderate effectiveness [67], while illuminating gillnets with LEDs has significantly reduced turtle bycatch in areas such as Sechura Bay (Peru) and the northern Adriatic Sea [68]. These technologies represent promising alternatives, particularly because they have proven feasible to implement without substantially compromising the catches of target species [67].

These findings underscore the need for more comprehensive conservation efforts to account for the spatial and behavioral complexity of the species [69]. The implementation of mitigation technologies must be supported by adaptive management, enforcement, and conservation policies that recognize the migratory and transboundary nature of loggerhead turtles and other species [70,71]. Moreover, regional initiatives and multilateral agreements are essential to ensure the effective protection of these animals, especially when coordinated with integrated strategies that include reducing fishing efforts, protecting critical habitats, and employing more selective fishing technologies. These combined actions represent the most promising path toward long-term conservation of C. caretta [72,73].

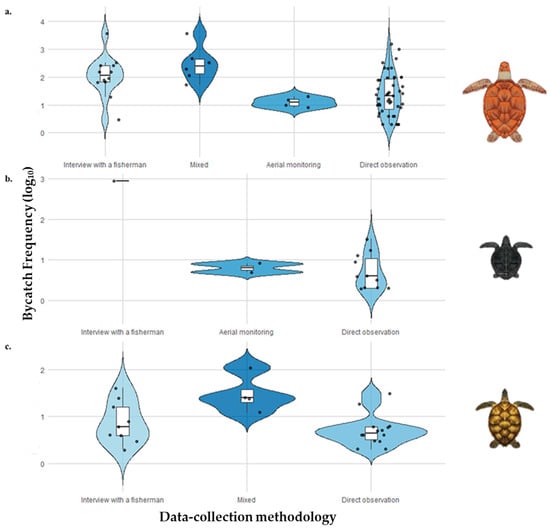

3.4. Relationship Between Methodology and Species Bycatch

The Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) revealed that certain sampling methodologies were significantly associated with the bycatch of specific species. Aerial monitoring showed significant negative effects on C. mydas (p = 0.0157) and L. kempii (p = 0.00146), indicating lower recorded bycatch frequencies for these species when this technique was used. Direct observation was also significantly associated with reduced bycatch frequencies for C. mydas (p = 0.0014), L. kempii (p = 0.00103), and E. imbricata (β = −0.77; p = 0.0016). Interviews with fishers showed a significant negative effect only for E. imbricata (β = −0.60; p = 0.0146). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the sampling methodologies and bycatch frequency for C. caretta, D. coriacea, L. olivacea, and N. depressus (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Distribution of sea turtle by-catch frequency (log10-transformed) according to different data-collection methodologies. The figure shows the variation in by-catch frequency among studies that applied distinct monitoring approaches: interviews with fishermen, mixed methods, aerial monitoring, and direct observation. Each violin plot illustrates the data distribution, median, and interquartile range. (a) Chelonia mydas; (b) Lepidochelys kempii; (c) Eretmochelys imbricata.

The negative association between aerial monitoring and the bycatch frequency of C. mydas and L. kempii can be explained by the inherent characteristics of the technique itself. As it relies on drone or aircraft imagery, it does not directly register bycatch events [74]. Although effective for estimating the presence and abundance of individuals over large areas, this approach tends to underestimate actual bycatch events, leading to biased frequencies in databases structured based on such observations [75]. Environmental factors, such as low visibility and high water turbidity, can further hinder the detection of turtles in aerial images, increasing the underdetection bias associated with this method [76]. However, this limitation should not be interpreted as an indicator of low species abundance but rather as a reflection of methodological constraints.

In contrast, mixed approaches that integrate multiple observation sources tend to offer broader and more robust estimates [77]. Moreover, aerial monitoring is typically not linked to active fishing efforts, unlike methodologies that gather data in real fishing contexts, where exposure intensity and spatial coverage are higher [78,79,80]. Therefore, part of the variation in observed bycatch frequency may be attributed not only to detectability, but also to differences in the actual exposure of turtles to fishing activity across methodologies.

Direct observations also present important limitations, even when conducted within the context of fishing operations. One of these limitations is the underreporting of bycatch events, which can occur because of failures in recording by observers or interactions that go unnoticed or are concealed by the crew, such as discards made before documentation [81,82]. Moreover, monitoring efforts tend to be limited to specific vessels, areas, or periods, thereby reducing the representativeness of the data when compared with more integrative methodologies [83,84]. Even when fishers are encouraged to cooperate, factors such as the operational dynamics of the vessels, characterized by a high turnover of activities and limited physical space, and adverse working conditions, including poor weather and observer overload, hinder the mitigation of such biases [85]. Thus, although it is widely used to estimate mortality and bycatch frequency, direct observation requires caution in the interpretation of its results given the methodological and operational challenges that affect data accuracy [86,87].

Interviews based on fishers’ Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK), while a valuable tool, particularly in regions where direct monitoring is unfeasible, are also subject to various biases [88,89]. For instance, respondents’ memory can be influenced by the time elapsed since the event, familiarity with the area, personal characteristics, such as age and gender, and even the nature of their relationship with the interviewer. These factors can compromise the accuracy of retrospective methods [90,91,92]. The reliability of estimates may also be affected by broader issues common to fishery-dependent data, such as gear selectivity, underreporting of bycatch, and unrecorded discards [92]. Additionally, the spatial distribution of fishing effort is a critical factor because effort is not homogeneous and may be concentrated in specific areas [93,94,95]. In such cases, combining different methodologiessuch as aerial monitoring, direct observation, and interviewscan be an effective strategy to reduce the biases inherent in each technique and broaden the scope of the information gathered [77].

Thus, our findings underscore the importance of considering methodological biases when interpreting bycatch patterns, and highlight the need to integrate multiple survey approaches. This integration is essential to generate more robust and reliable estimates of sea turtle occurrence and abundance, particularly in small-scale fisheries, where fishing efforts are rarely well-documented and often underestimated [96,97].

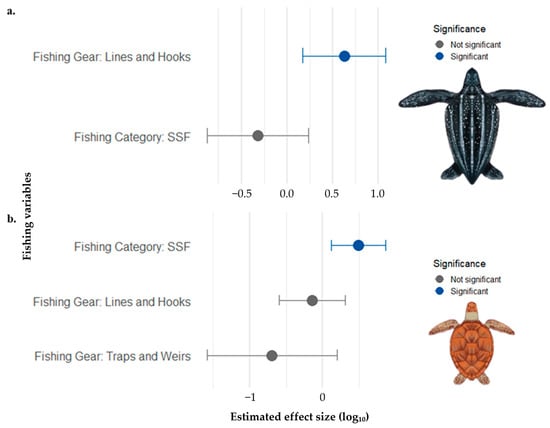

3.5. Relationship Between Fishery Types, Gear Used, and Species Caught

In mixed-effects modeling of fishery-related factors influencing sea turtle bycatch, significant effects were detected for certain species. For Dermochelys coriacea, the GLMM showed that hook-and-line fishing was associated with a higher bycatch frequency (p = 0.0079) than net-based fishing. For Chelonia mydas, small-scale fisheries (SSF) were associated with a higher bycatch frequency (p = 0.0115) than that of industrial fisheries. For the remaining species analyzed (Caretta caretta, Lepidochelys olivacea, Lepidochelys kempii, Eretmochelys imbricata, and Natator depressus), no statistically significant effects of fishery category or gear type on bycatch frequency were observed (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Estimated effects of fishing category and gear type on sea turtle by-catch frequency, based on Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM). Points represent the estimated coefficients on a log10-transformed scale, and horizontal bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant effects (p < 0.05) are shown in blue. (a) Effects on Dermochelys coriacea; (b) Effects on Caretta caretta.

The strong bycatch effect observed for D. coriacea in hook-and-line fisheries can be attributed to a combination of behavioral and ecological factors [12]. The diet of this species, which consists primarily of gelatinous organisms such as jellyfish, increases the likelihood of interaction with similar-looking bait types such as squid and cut bait fish commonly used in longline fisheries [98,99]. In addition, D. coriacea frequently dives to depths greater than 300 m, which overlaps with the operational depth of many pelagic longlines [100]. These dives also align with the diurnal vertical migration of gelatinous prey, which move to deeper waters during the day, thereby increasing turtle exposure to fishing gear [101]. Recent studies have reported that high bycatch rates of this species are closely associated with areas of high biological productivity, where jellyfish abundance attracts turtles to zones of intense fishing activity, thereby intensifying bycatch risk [102,103].

These findings emphasize the need for more targeted mitigation approaches for D. coriacea, considering its foraging behavior and spatial distribution patterns. Implementing mitigation strategies, such as modifying bait or hook type, may effectively reduce bycatch without significantly affecting target species catch [65,104]. Adjusting the depth at which longlines are deployed and using more selective gear technologies can also help reduce incidental capture without compromising fishing efficiency [30,105]. Moreover, establishing protected fishing zones that avoid overlap with key foraging habitats could further minimize the risk of unintended capture [106,107].

In the case of Chelonia mydas, the higher bycatch frequency observed in small-scale fisheries may be explained by the spatial overlap between the foraging areas of the species and zones of artisanal fishing [108]. These fisheries, mostly located in shallow coastal waters, are particularly prone to interactions with gillnets, traps, and fishing lines that are commonly used in such regions [109,110]. Although industrial fisheries also pose a threat, bycatch rates in small-scale fisheries may be even higher, especially in areas with limited enforcement and regulation [111]. Studies have reported that, in several tropical and Mediterranean regions, artisanal fisheries represent a significant threat to C. mydas, with bycatch rates comparable to or even higher than those observed in industrial fisheries [112,113,114].

Informal fishing practices, which typically lack mitigation technologies, such as circle hooks or escape devices, make it more difficult to implement bycatch reduction strategies [30,115,116]. This highlights the urgency of policies focused on artisanal fisheries, extending beyond fisher training, to include stronger governmental oversight of these activities [117,118,119]. In this context, it is essential to invest in sustainable alternatives that provide direct benefits to local communities, such as payments for ecosystem services, certifications for responsible fishing, and access to differentiated markets [120,121]. Integrating local communities into participatory management strategies, along with incentives for more selective practices and ongoing technical support, may be a promising path to reconcile the conservation of vulnerable species, such as C. mydas, with the maintenance of food security and income for these populations.

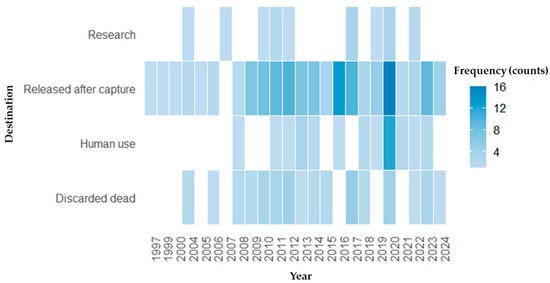

3.6. Post-Capture Outcomes over Time

The majority of captured turtles were released after capture (n = 126; 60.6%), followed by individuals found dead and discarded (n = 38; 18.3%), used for human consumption (n = 18; 8.7%), for research purposes (n = 15; 7.2%), sold (n = 8; 3.8%), used in religious practices (n = 2; 1.0%), and used for handicrafts (n = 1; 0.5%). Percentages were calculated based on the total number of post-capture outcome records (n = 208), rather than the number of studies. It is important to note that some studies reported more than one type of outcome for the captured species; therefore, each outcome category was counted separately, and totals may exceed 100%. Additionally, the chi-square test did not reveal a significant association between the year of publication and post-capture outcome categories (χ2, p > 0.05), indicating no temporal variation in the reported outcomes of captured turtles over the analysed period (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Heatmap showing the annual frequency of sea turtle bycatch outcomes between 1997 and 2024. Each cell represents the number of records (count of occurrences) for a given destination type per year. The colour gradient indicates frequency (number of cases), with darker shades representing higher values.

The predominance of turtles released after capture partly reflects the growth of scientific output and study coverage on the subject as well as the increasing recognition of the importance of sea turtle conservation in fishing environments, with reported improvements in release practices in both artisanal and industrial fisheries [122,123,124]. However, it is important to note that release does not necessarily guarantee survival [125]. Post-release mortality caused by stress from capture, improper handling, or physical injuries can be substantial and may undermine conservation efforts [126,127]. Studies have indicated that the survival rate of turtles after release depends on several factors, including immersion time, capture conditions, and handling methods [22,71]. Therefore, although release is a positive practice, it must be accompanied by proper handling protocols to minimize the negative effects of bycatch.

Conversely, the use of captured turtles for research suggests their involvement in monitoring or rehabilitation programs, although this practice is still not well established in many regions [128]. However, the high proportion of turtles discarded dead or destined for human consumption indicates that harmful practices persist, particularly in areas with limited enforcement [129,130]. Furthermore, commercialization, religious use, and use for handicrafts demonstrate that socioeconomic and cultural factors continue to shape human interactions with sea turtles [131]. As noted by Vieira et al. [132], while conservation efforts provide social benefits, such as environmental education and community empowerment, traditional practices and economic pressures remain significant challenges for species protection.

These findings reinforce the need to expand environmental education initiatives, fisher training programs, and the implementation of safe-release protocols, while promoting public policies that encourage more sustainable fishing practices. For these strategies to be effective, it is essential to actively involve local communities in dialogue, decision making, and resource management by integrating community development projects, education, and awareness campaigns [133]. Approaches such as promoting microfinance, implementing mariculture projects, and creating community-based monitoring programs can offer alternative income sources, reduce dependence on subsistence fishing, and help mitigate the pressure on sea turtle populations [134,135,136,137].

4. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate a significant increase in scientific output on sea turtle bycatch, particularly since 2010. This growth reflects the strengthening of international conservation agendas and rising global concern regarding the impacts of fishing on threatened species. In addition, a growing trend in bycatch frequency was observed over time, raising concerns about ongoing fishing pressure, including the intensified use of fishing gear and highlighting the limited effectiveness of current mitigation measures.

Moreover, we identified heterogeneity in bycatch patterns across species and sampling methods. Techniques such as aerial monitoring and direct observation proved less effective in detecting bycatch of certain species, including C. mydas, L. kempii, and E. imbricata. These differences underscore the need for combined and adaptive monitoring strategies that consider both the ecological behaviors of species and the operational characteristics of regional fishing contexts. In this regard, the predominance of C. caretta in bycatch records points to the urgent need for targeted mitigation measures for this species, while also increasing attention to less frequently reported but potentially underestimated at-risk species.

Despite recent advances, several research gaps persist in the literature, such as the lack of standardized data on the fate of captured turtles, underrepresentation of certain regions and species, and limited integration of complementary monitoring methods. Future research should prioritize more integrated and collaborative approaches, focusing on the evaluation of exclusion technologies, cumulative impact of ghost fishing, and engagement of local fishing communities. Only with consistent data that are sensitive to regional and ecological specificities will it be possible to guide more effective and equitable conservation policies for sea turtle protection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/coasts6010002/s1 [138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148], Table S1: Articles included in the analyses; Supplementary File S2: PRISMA 2020 checklist; Supplementary File S3: R packages and versions used in the analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C.d.S.; methodology, B.C.d.S.; validation, B.C.d.S.; formal analysis, B.C.d.S. and L.G.M.; investigation, B.C.d.S.; data curation, B.C.d.S. and L.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C.d.S.; writing—review and editing, B.C.d.S., L.G.M., J.H.d.S., Y.C.B.B.d.O. and R.R.N.A.; visualization, B.C.d.S.; supervision, Y.C.B.B.d.O. and R.R.N.A.; project administration, B.C.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), which provided graduate fellowships to BCS, LGM, and JHS. This study was financed in part by Paraiba State University, grant #02/2024. Additional financial support was provided by the Programa de Pesquisas Ecológicas de Longa Duração (PELD)–Rio Paraíba Integrado (RIPA) (FAPESQ/PELD Call No. 21/2020, grant agreement No. 1041403/2021) and by the Fundo Setorial de Recursos Hídricos (CT-Hidro) (Process No. 409348/2022-8). We also thank the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for granting a Research Productivity Fellowship to Rômulo Romeu Nóbrega Alves (Grant No. 307011/2022-4). The article was invited, and the Article Processing Charge (APC) was fully waived by the journal.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia) (PPGCB) at the Universidade Federal da Paraíba (UFPB), the Instituto Parahyba de Sustentabilidade through the Observatório Marinho project, and the Laboratório de Ecologia de Bentos (LEB) for institutional and logistical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Yang, Q.; Luo, T.; He, P.; Franzese, P.P.; Lombardi, G.V. Emergy-based evaluation of world coastal ecosystem services. Water Res. 2021, 204, 117656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N.; Rossi, A.; Pavel, A.B. The coastal tourism industry in the Mediterranean: A critical review of the socio-economic and environmental pressures & impacts. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, V.P.; Mega, V.P. Threatened urban and ocean biodiversity: The imperative of resilience. In Eco-Responsible Cities and the Global Ocean: Geostrategic Shifts and the Sustainability Trilemma; Wiley: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 43–84. [Google Scholar]

- Saengsupavanich, C.; Agarwala, N.; Magdalena, I.; Ratnayake, A.S.; Ferren, V. Impacts of a growing population on the coastal environment of the Bay of Bengal. Anthr. Coasts 2024, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, M.J.; Duplisea, D.E.; Hunter, K.L.; Rice, J. Consistent risk management in a changing world: Risk equivalence in fisheries and other human activities affecting marine resources and ecosystems. Front. Clim. 2022, 3, 781559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambon, M.; Ziveri, P.; Alvarez Fernandez, S.; Chevallier, A.; Dupont, J.; Ngunu Wandiga, J.; Wambiji, N.; Reyes-Garcia, V. The gendered dimensions of small-scale fishing activities: A case study from coastal Kenya. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 257, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Illuminating the Multi-Dimensional Contributions of Small-Scale Fisheries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/13887065 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Basurto, X.; Gutierrez, N.L.; Franz, N.; Mancha-Cisneros, M.D.M.; Gorelli, G.; Aguión, A.; Funge-Smith, S.; Harper, S.; Mills, D.J.; Nico, G.; et al. Illuminating the multidimensional contributions of small-scale fisheries. Nature 2025, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campling, L.; Kim, H. Labour regimes in industrial tuna fisheries: Exploitation, ecology and global production networks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2025, lbaf018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Escauriaza, R.; Gizzi, F.; Gouveia, L.; Gouveia, N.; Hermida, M. Small-scale fisheries in Madeira: Recreational vs artisanal fisheries. Sci. Mar. 2021, 85, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánovas-Molina, A.; García-Frapolli, E. A review of vulnerabilities in worldwide small-scale fisheries. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2022, 29, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.C.; Rosa, D.; Gonçalves, J.M.; Coelho, R. A review of reported effects of pelagic longline fishing gear configurations on target, bycatch and vulnerable species. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2024, 34, e4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2024-2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2024. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Reavis, J.L.; Witherington, B.E.; Bresette, M.J.; Ragan, K.; Wang, J.H.; Pratt, S.C.; Demir, H.S.; Blain, J.; Ozev, S.; DeNardo, D.F.; et al. Novel behavioral responses of sea turtles to gillnet fishing gear. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 306, 111161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.; Heilweck, M.; Petros, P. Saving the planet with appropriate biotechnology: 2. Cultivate shellfish to remediate the atmosphere. Mex. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 6, 31–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streck, C. Synergies between the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the Paris Agreement: The role of policy milestones, monitoring frameworks and safeguards. Clim. Policy 2023, 23, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanger, M.; Dudouet, B.; Gourguet, S.; Thébaud, O.; Ballance, L.T.; Becu, N.; Bisack, K.D.; Cudennec, A.; Daurès, F.; Lehuta, S.; et al. A practical framework to evaluate the feasibility of incentive-based approaches to reduce bycatch of marine mammals and other protected species. Mar. Policy 2025, 177, 106661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallwood, P. Why do countries knowingly sign ineffective treaties? The case of high seas fishing. KMI Int. J. Marit. Aff. Fish. 2021, 13, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Chaloupka, M.; Benaka, L.R.; Bowlby, H.; Fitchett, M.; Kaiser, M.; Musyl, M. Phylogeny explains capture mortality of sharks and rays in pelagic longline fisheries: A global meta-analytic synthesis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne, C.; Lam, S.S.; Foong, S.Y.; Mahari, W.A.W.; Ma, N.L.; Bank, M.S. A global meta-analysis of gillnet bycatch of toothed whales: Mitigation measures and research gaps. iScience 2024, 27, 111482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäck, A.; Asper, M.M.; Madsen, S.; Eriksson, L.; Costea, V.A.; Hasson, H.; Bergström, A. Collaboration between local authorities and civil society organisations for improving health: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e092525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhou, C.; Gilman, E.; Cao, J.; Wan, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, J.; Xu, L.; Song, L.; Dai, X.; et al. A meta-analysis of bycatch mitigation methods for sea turtles vulnerable to swordfish and tuna longline fisheries. Fish. Fish. 2025, 26, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, E.; Fanning, L. Implementing adaptive management within a fisheries management context: A systematic literature review revealing gaps, challenges, and ways forward. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.W.; Viana-Junior, A.B.; Araújo, M.E.; Mourão, J.S. Environmental risk perception and adaptative strategies in a neotropical fishing population: Socioeconomic aspects and community participation. Mar. Policy 2025, 175, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, B.P.; Posnik, Z.A.; Hurley, B.J.; DiMatteo, A.D.; Bandimere, A.; Rodriguez, I.; Maxwell, S.M.; Meyer, L.; Brenner, H.; Jensen, M.P.; et al. Marine turtle regional management units 2.0: An updated framework for conservation and research of wide-ranging megafauna species. Endang. Species Res. 2023, 52, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiteh, V.; Peatman, T.; Lindfield, S.; Gilman, E.; Nicol, S. Bycatch estimates from a Pacific tuna longline fishery provide a baseline for understanding the long-term benefits of a large, blue water marine sanctuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 720603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.M.; Rice, J.; Himes-Cornell, A.; Friedman, K.J.; Charles, A.; Diz, D.; Appiott, J.; Kaiser, M.J. OECMs in marine capture fisheries: Key implementation issues of governance, management, and biodiversity. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 920051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, A.; Ishii, A. Pursuing sustainability? Ecosystem considerations in Japan’s fisheries governance. Mar. Policy 2023, 152, 105603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.L. Bycatch governance and best practice mitigation technology in global tuna fisheries. Mar. Policy 2011, 35, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.; Sato, M.; Small, C.; Sullivan, B.; Inoue, Y.; Ochi, D. Bycatch in Longline Fisheries for Tuna and Tuna-Like Species: A Global Review of Status and Mitigation Measures; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 588; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–199. [Google Scholar]

- Takyi, R.; Addo, C.; El Mahrad, B.; Adade, R.; ElHadary, M.; Nunoo, F.K.E.; Essandoh, J.; Chuku, E.O.; Iriarte-Ahon, F. Marine fisheries management in the eastern central Atlantic Ocean. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 244, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawkes, K.W.; Cummins, V. Beneath the surface of the first world ocean assessment: An investigation into the global process’ support for sustainable development. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turra, A. The Ocean Decade in the perspective of the Global South. Ocean Coast. Res. 2021, 69, e21048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.S.; Devereaux, S.G.; Gjerde, K.; Chand, K.; Martinez, J.; Crowder, L.B. The diverse benefits of biodiversity conservation in global ocean areas beyond national jurisdiction. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1001240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Wu, Q.; Peng, C.; Jefferson, T.A.; Long, Z.; Luo, F.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S.L. Bycatch mitigation requires livelihood solutions, not just fishing bans: A case study of the trammel-net fishery in the northern Beibu Gulf, China. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón, M.; Defeo, O. Perceptions and attitudes of residents toward small-scale longline tuna fishing in the Galapagos Marine Reserve: Conservation and management implications. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1235926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, C.M.; Fortibuoni, T.; Bueno-Pardo, J.; Coll, M.; Franco, A.; Giménez, J.; Stranga, Y.; Peck, M.A.; Claver, C.; Brasseur, S.; et al. Top predator status and trends: Ecological implications, monitoring and mitigation strategies to promote ecosystem-based management. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1282091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ullah, M. The Pakistan-China FTA: Legal challenges and solutions for marine environmental protection. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1478669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.; Pauly, D.; Sumaila, U.R. Hope or despair revisited: Assessing progress and new challenges in global fisheries. Fish Fish. 2025, 26, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afewerki, S.; Asche, F.; Misund, B.; Thorvaldsen, T.; Tveteras, R. Innovation in the Norwegian aquaculture industry. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayilu, R.K.; Fabinyi, M.; Barclay, K.; Bawa, M.A. Blue economy: Industrialisation and coastal fishing livelihoods in Ghana. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2023, 33, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, J.M.; Murray, K.T.; Patel, S.; Smolowitz, R.; Haas, H.L. Evaluating simple measures of spatial-temporal overlap as a proxy for encounter risk between a protected species and commercial fishery. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 4, 1118418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labastida-Estrada, E.; Machkour-M’Rabet, S. Unraveling migratory corridors of loggerhead and green turtles from the Yucatán Peninsula and its overlap with bycatch zones of the Northwest Atlantic. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno-Chaves, A.; Marrari, M.; Arias-Zumbado, F.; García-Rojas, A.; Mug-Villanueva, M. Composition of pelagic fish in commercial landings of the longline fishery in the Costa Rica Pacific during 2015–2021. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1490883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzanna, K.; Tomasz, U.; Michał, G.; Robert, P. How high-tech solutions support the fight against IUU and ghost fishing: A review of innovative approaches, methods, and trends. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 112539–112554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.L.; Armstrong, C.W. Ghost fishing gear and their effect on ecosystem services—Identification and knowledge gaps. Mar. Policy 2023, 150, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, R.J. Status, trends and best management practices for abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) in Asia and the Pacific. Mar. Plast. Pollut. Rule Law 2021, 168, 168–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ssempijja, D.; Einarsson, H.A.; He, P. Abandoned, lost, and otherwise discarded fishing gear in world’s inland fisheries. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2024, 34, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, T.A. Managing abandoned, lost and otherwise discarded fishing gear (Derelict Gear) in Eastern Caribbean small-scale fisheries: An assessment of legislative, regulatory and policy gaps. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Dan, H.; Lee, C. Recommendations and challenges for the regulations of ghost fishing gears. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.Z.; Wilcox, C. Global causes, drivers, and prevention measures for lost fishing gear. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 690447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, P.; Broderick, A.C.; Camiñas, J.A.; Cardona, L.; Carreras, C.; Demetropoulos, A.; Fuller, W.J.; Godley, B.J.; Hochscheid, S.; Kaska, Y.; et al. Mediterranean sea turtles: Current knowledge and priorities for conservation and research. Endang. Species Res. 2018, 36, 229–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Tiwari, M.; Rocha, F.; Rodrigues, E.; Monteiro, R.; Araújo, S.; Abella, E.; Loureiro, N.S.; Clarke, L.J.; Marco, A. Evaluating loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) bycatch in the small-scale fisheries of Cabo Verde. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2022, 32, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroluongo, G.; Centelleghe, C.; Sciancalepore, G.; Ceolotto, L.; Danesi, P.; Pedrotti, D.; Mazzariol, S. Environmental and pathological factors affecting the hatching success of the two northernmost loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) nests. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Parraga, D.; Crespo-Picazo, J.L.; Sterba-Boatwright, B.; Marco, V.; Muñoz-Baquero, M.; Robinson, N.J.; Stacy, B.; Fahlman, A. New insights into risk variables associated with gas embolism in loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) caught in trawls and gillnets. Conserv. Physiol. 2023, 11, coad048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatase, H. Mechanisms that produce and maintain a foraging dichotomy in adult loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta): Which tactic has higher fitness, oceanic or neritic? J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2021, 541, 151586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.C.; Rosengarten, S.; Hooper, C.; Fuentes, M.M. Post-release changes in the fine-scale diving behavior and activity of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) from the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Anim. Biotelemetry 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.F.; Tucker, A.D.; Foley, A.M.; Schroeder, B.A.; Giove, R.J.; Meylan, A.B. Spatiotemporal occurrence of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) on the West Florida Shelf and apparent overlap with a commercial fishery. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 71, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massutí, E.; Sánchez-Guillamón, O.; Farriols, M.T.; Palomino, D.; Frank, A.; Bárcenas, P.; Rincón, B.; Martínez-Carreño, N.; Keller, S.; López-Rodríguez, C.; et al. Improving scientific knowledge of Mallorca Channel seamounts (Western Mediterranean) within the framework of Natura 2000 Network. Diversity 2021, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.C.; Kyritsis, N.; Mills, M.; Godfrey, M.H.; Harms, C.A.; Anderson, P.E.; Shedlock, A.M. Tissue and temperature-specific RNA-seq analysis reveals genomic versatility and adaptive potential in wild sea turtle hatchlings (Caretta caretta). Animals 2021, 11, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, M.F.; Avino, P.; Notardonato, I.; Di Fiore, C.; Mattei, D.; Gauger, M.F.W.; Gelippi, M.; Cicala, D.; Hochscheid, S.; Camedda, A.; et al. Phthalate esters (PAEs) concentration pattern reflects dietary habitats (δ13C) in blood of Mediterranean loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriani, S.A.; Murasko, S.; Addison, D.S.; Anderson, D.; Curry, G.; Desjardin, N.A.; Eastman, S.F.; Evans, D.R.; Evou, N.; Fuentes, M.M.P.B.; et al. Monitoring population-level foraging distribution of a marine migratory species from land: Strengths and weaknesses of the isotopic approach on the Northwest Atlantic loggerhead turtle aggregation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1189661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, D.; Ballance, L.T.; Dagorn, L.; Dutton, P.H.; Lent, R. Mitigating bycatch: Novel insights to multi-disciplinary approaches. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 613285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Zollett, E.; Beverly, S.; Nakano, H.; Davis, K.; Shiode, D.; Dalzell, P.; Kinan, I. Reducing sea turtle by-catch in pelagic longline fisheries. Fish Fish. 2006, 7, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Gilman, E.; Minami, H.; Mituhasi, T.; Carruthers, E. Mitigating bycatch in tuna fisheries. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2017, 27, 881–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Chaloupka, M.; Bach, P.; Fennell, H.; Hall, M.; Musyl, M.; Piovano, S.; Poisson, F.; Song, L. Effect of pelagic longline bait type on species selectivity: A global synthesis of evidence. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2020, 30, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiners-Mandujano, C.; Tovar-Ávila, J.; Jiménez-Badillo, L.; Oviedo-Pérez, J.L. Population structure dynamics of elasmobranchs susceptible to shrimp trawling along the southern Gulf of Mexico. Fishes 2025, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgili, M.; Vasapollo, C.; Lucchetti, A. Can ultraviolet illumination reduce sea turtle bycatch in Mediterranean set net fisheries? Fish. Res. 2018, 199, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalo-Morla, S.; Belda, E.J.; March, D.; Revuelta, O.; Cardona, L.; Giralt, S.; Crespo-Picazo, J.L.; Hochscheid, S.; Marco, A.; Merchán, M.; et al. Assessing the use of marine protected areas by loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) tracked from the western Mediterranean. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 38, e02196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez-Tapia, L.A.; Ponce-Díaz, G.; Pedroza-Páez, D.; Díaz-de-León, A.J.; Arreguín-Sánchez, F. Application of exploratory modeling in support of transdisciplinary inquiry: Regulation of fishing bycatch of loggerhead sea turtles in Gulf of Ulloa, Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 643347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baéz, J.C.; Domingo, A.; Murua, H.; Macías, D.; Camiñas, J.A.; Poisson, F.; Jorda, M.J.J.; López, J.; Griffiths, S.; Roman, M.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in monitoring and mitigating sea turtle bycatch in tuna regional fisheries management organizations. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2024, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.A. Protection of the marine environment: Rights and obligations in trade agreements. Korean J. Int. Comp. Law 2021, 9, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, E.; Kotera, M.; Phillott, A.D. The roles of sea turtles in ecosystem processes and services. Indian Ocean Turt. Newsl. 2022, 36, 23–31. Available online: https://www.iotn.org/iotn36-06-the-roles-of-sea-turtles-in-ecosystem-processes-and-services/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Corcoran, E.; Winsen, M.; Sudholz, A.; Hamilton, G. Automated detection of wildlife using drones: Synthesis, opportunities and constraints. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, G.; Lawrence, M.J.; McKindsey, C.W.; Lacoursière-Roussel, A.; Bergeron, H.; Gauthier, S.; Wringe, B.F.; Trudel, M. A review of data collection methods used to monitor the associations of wild species with marine aquaculture sites. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1160–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odzer, M.N.; Brooks, A.M.; Heithaus, M.R.; Whitman, E.R. Effects of environmental factors on the detection of subsurface green turtles in aerial drone surveys. Wildl. Res. 2022, 49, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, P.; Chiarini, M.; Romagnoni, G.; Toomey, L.; Lucchetti, A.; Neglia, C.; Spedicato, M.T.; Zupa, W.; Astarloa, A. Turtle bycatch from trawlers: What modelling is telling us in the southern Adriatic Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 319, 109293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.M.P. Fisheries oceanography using satellite and airborne remote sensing methods: A review. Fish. Res. 2000, 49, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, L.C.; Tugwell, H.; Katselidis, K.A.; Schofield, G. Aerial drones reveal the dynamic structuring of sea turtle breeding aggregations and minimum survey effort required to capture climatic and sex-specific effects. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 864694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantonio, N.; Panigada, S.; Lauriano, G. Quantifying abundance and mapping distribution of logger-head turtles in the Mediterranean Sea using aerial surveys: Implications for conservation. Diversity 2023, 15, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeyer, L.C.; McKinley, T.J.; Bréheret, N.; Bal, G.; Petchell Balchin, G.; Bitsindou, A.; Chauvet, E.; Collins, T.; Curran, B.K.; Formia, A.; et al. Missing data in sea turtle population monitoring: A Bayesian statistical framework accounting for incomplete sampling. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 817014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precoda, K.; Orphanides, C.D. Impact of fishery observer protocol on estimated bycatch rates of marine mammals. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2024, 81, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, S.M.; Lewison, R.L. Quantifying fishing effort: A synthesis of current methods and their applications. Fish Fish. 2008, 9, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Ruttenberg, B.I.; Walter, R.K.; Pendleton, F.; Samhouri, J.F.; Liu, O.R.; White, C. High resolution assessment of commercial fisheries activity along the US West Coast using Vessel Monitoring System data with a case study using California groundfish fisheries. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, F.; Domeh, V.; Khan, F.; Bose, N.; Sanli, E. Analyzing operational risk for small fishing vessels considering crew effectiveness. Ocean Eng. 2022, 249, 110512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Weber, A.; Pipitone, C.; Leopold, M.; Cronin, M.; Scheidat, M.; Doyle, T.K.; BuhlMortensen, L.; Buhl-Mortensen, P.; D’Anna, G.; et al. Monitoring marine populations and communities: Methods dealing with imperfect detectability. Aquat. Biol. 2012, 16, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanisi, E.; Pace, D.S.; Orasi, A.; Vitale, M.; Arcangeli, A. A global systematic review of species distribution modelling approaches for cetaceans and sea turtles. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbleyth-Evans, J.; Lacy, S.N. Feedback between fisher local ecological knowledge and scientific epistemologies in England: Building bridges for biodiversity conservation. Marit. Stud. 2019, 18, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnino, F.; Estévez, R.A.; Caillaux, M.; Velez-Zuazo, X.; Gelcich, S. Local ecological knowledge (LEK) suggests overfishing and sequential depletion of Peruvian coastal groundfish. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2023, 15, e210272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E.; Cox, T.M.; Lewison, R.L.; Read, A.J.; Bjorkland, R.; McDonald, S.L.; Crowder, L.B.; Aruna, E.; Ayissi, I.; Espeut, P.; et al. An interview-based approach to assess marine mammal and sea turtle captures in artisanal fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikecz, R. Interviewing elites: Addressing methodological issues. Qual. Inq. 2012, 18, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessesen, B.L.; González-Suárez, M. The value and limitations of local ecological knowledge: Longitudinal and retrospective assessment of flagship species in Golfo Dulce, Costa Rica. People Nat. 2021, 3, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, O.; Elouaer, A.; Maffucci, F.; Karaa, S.; Bradai, M.N.; ElHili, H.; Bentivegna, F.; Said, K.; Chatti, N. Population structure and dispersal patterns of loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta in Tunisian coastal waters, central Mediterranean. Endang. Species Res. 2012, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutniczak, B. Increasing pressure on unregulated species due to changes in individual vessel quotas: An empirical application to trawler fishing in the Baltic Sea. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2014, 29, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.C. Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Herpetofauna in Southeast Asia from Broad Scale Responses to Fine Scale Responses in an Ever-Changing Anthropogenic Landscape. Ph.D. Thesis, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitaet Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://bonndoc.ulb.uni-bonn.de/xmlui/handle/20.500.11811/11638 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Kleiber, D.; Harris, L.M.; Vincent, A.C. Gender and small-scale fisheries: A case for counting women and beyond. Fish Fish. 2015, 16, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, D.; Vianna, G.M.; Ansell, M.; Coulter, A.; Derrick, B.; Greer, K.; Noël, S.L.; Palomares, M.L.D.; Zhu, A.; Pauly, D. Fishing effort and associated catch per unit effort for small-scale fisheries in the Mozambique Channel region: 1950–2016. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 707999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.S.; Noernberg, M.A.; Bleninger, T.B.; Hausen, V.; Pozo, A.; Camargo, L.S.; Hara, S.; Nogueira Júnior, M. Social media in service of marine ecology: New observations of the ghost crab Ocypode quadrata scavenging on Portuguese man-of-war Physalia physalis. Aquat. Ecol. 2022, 56, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanucci, R.M.; Goldberg, D.W.; Maranho, A.; Giffoni, B.D.B.; Boaventura, I.C.D.R.; Dias, R.B.; Leonardi, S.B.; Gallo Neto, H.; Silva, B.M.G.; Rogerio, D.W.; et al. Impacts of pelagic longline fisheries on sea turtles in the Santos Basin, Brazil. Front. Amphib. Reptile Sci. 2024, 2, 1385774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, N.; Robillard, A.J.; Shillinger, G.L.; Lyubchich, V.; Secor, D.H.; Fagan, W.F.; Bailey, H. Clustering and classification of vertical movement profiles for ecological inference of behavior. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, M.J.; Avens, L.; Haas, H.L.; Harms, C.A.; Patel, S.H.; Snodgrass, D.; Sasso, C.R. Regional variation in leatherback dive behavior in the northwest Atlantic. Endanger. Species Res. 2024, 55, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.H.; Morreale, S.J.; Paladino, F.V.; Shillinger, G.L.; Benson, S.R.; Eckert, S.A.; Bailey, H.; Tomillo, P.S.; Bograd, S.J.; Eguchi, T.; et al. Predicting bycatch hotspots for endangered leatherback turtles on longlines in the Pacific Ocean. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20132559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, B.; James, M.C.; Worm, B. Jellyfish distribution in space and time predicts leatherback sea turtle hot spots in the Northwest Atlantic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, D.; Okamoto, K.; Ueno, S. Multifaceted effects of bycatch mitigation measures on target or non-target species for pelagic longline fisheries and consideration for bycatch management. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2024, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, F.; Budan, P.; Coudray, S.; Gilman, E.; Kojima, T.; Musyl, M.; Takagi, T. New technologies to improve bycatch mitigation in industrial tuna fisheries. Fish Fish. 2022, 23, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.A.; Kennelly, S.J. Bycatches of endangered, threatened and protected species in marine fisheries. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2018, 28, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, G.E.; Price, C.A.; Riley, K.L.; Morris, J.A., Jr. A global review of protected species interactions with marine aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 1686–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Y.C.B.B.; Rivera, D.N.; Querido, L.C.A.; Mourão, J.S. Critical areas for sea turtles in Northeast Brazil: A participatory approach for a data-poor context. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, V.S.; Fabré, N.N.; Malhado, A.C.; Ladle, R.J. Tropical artisanal coastal fisheries: Challenges and future directions. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2014, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, S.; Marçalo, A.; Marques, T.A.; Pires, A.; Rangel, M.; Ressurreição, A.; Monteiro, P.; Erzini, K.; Gonçalves, J.M. Interactions between air-breathing marine megafauna and artisanal fisheries in Southern Iberian Atlantic waters: Results from an interview survey to fishers. Fish. Res. 2022, 254, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwan, A.; Favero, M.; Van Putten, I.E.; Arqueros Mejica, M.S.; Bergseth, B.J.; Lau, J.D.; Copello, S. Reducing bycatch in offshore commercial fisheries: Stakeholder perspectives on mitigation measures. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2025, 38, 710–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.H.; Awabdi, D.R.; Melo, M.T.D.; Giffoni, B.; Bugoni, L. Nonlethal capture of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in fishing weirs as an opportunity for population studies and conservation. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 170, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpio, A.J.; Alvarez, Y.; Serrano, R.; Vergara, M.B.; Quintero, E.; Tortosa, F.S.; Rivas, M.L. By-catch of sea turtles in Pacific artisanal fishery: Two points of view: From observer and fishers. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 936734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhichi, M.; Girard, A.; Jribi, I. Fishermen interviews: A cost-effective tool for evaluating the impact of fisheries on vulnerable sea turtles in Tunisia and identifying levers of mitigation. Animals 2023, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidu, I.; Brobbey, L.K.; Paul, O.T.; van Beuningen, D.; Seidu, M.; Dulvy, N.K. Practices and informal institutions governing artisanal gillnet fisheries in Western Ghana. Marit. Stud. 2024, 23, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimu, T.; Williams, S.; Spocter, M. Analysing informal governance arrangements in small-scale fisheries: A case study of Norton, Zimbabwe. Int. J. Commons 2025, 19, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, A.S.; Rajiani, I.; Arisanty, D. Sustainability of floodplain wetland fisheries of rural Indonesia: Does culture enhance livelihood resilience? Sustainability 2022, 14, 14461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svolkinas, L.; Holmes, G.; Dmitrieva, L.; Ermolin, I.; Suvorkov, P.; Goodman, S.J. Stakeholder consensus suggests strategies to promote sustainability in an artisanal fishery with high rates of poaching and marine mammal bycatch. People Nat. 2023, 5, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussellaa, W.; Bradai, M.N.; Mallat, H.; Enajjar, S.; Saidi, B.; Jribi, I. Ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia): An urgent need for a conservation code of conduct. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.M.; Himes-Cornell, A.; Pita, C.; Arton, A.; Favret, M.; Averill, D.; Stohs, S.; Longo, C.S. Social and economic outcomes of fisheries certification: Characterizing pathways of change in canned fish markets. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 791085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ercilla, I.; Rocha-Tejeda, L.; Fulton, S.; Espinosa-Romero, M.J.; Torre, J.; Rivera-Melo, F.F. Who pays for sustainability in the small-scale fisheries in the global south? Ecol. Econ. 2024, 226, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Gearhart, J.; Price, B.; Eckert, S.; Milliken, H.; Wang, J.; Swimmer, Y.; Shiode, D.; Abe, O.; Peckham, S.H.; et al. Mitigating sea turtle by-catch in coastal passive net fisheries. Fish Fish. 2010, 11, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlidge, W.N.; Squires, D.; Alfaro-Shigueto, J.; Booth, H.; Mangel, J.C.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. A mitigation hierarchy approach for managing sea turtle captures in small-scale fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, H.; Olivas, T.; Gumbleton, S.; Beckham, N.; Steury, T.D.; Willoughby, J.R.; Dunning, K. Willingness of recreational anglers to modify hook and bait choices for sea turtle conservation in Mobile Bay, Alabama, Gulf of Mexico. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2025, 32, e12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimple, R.J.; Kohl, M.T.; Buhlmann, K.A.; Tuberville, T.D. Translocation of long-term captive eastern box turtles and the efficacy of soft-release: Implications for turtle confiscations. Northeast. Nat. 2024, 31, T37–T54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoddy, J.E.; Williard, A.S. Movements and post-release mortality of juvenile sea turtles released from gillnets in the lower Cape Fear River, North Carolina, USA. Endanger. Species Res. 2010, 12, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewardena, T.; Mandrak, N.E.; Paterson, J.E.; Davy, C.M.; Edge, C.B.; Lentini, A.M.; Litzgus, J.D. Effects of release method on the survival, somatic growth, and body condition of headstarted turtles. J. Wildl. Manag. 2024, 88, e22505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Bonilla, C.M.; Quiros-Rojas, N.M.; Rudín-Salazar, E. Rehabilitation of marine turtles and welfare improvement by application of environmental enrichment strategies. Animals 2022, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollett, E.A.; Swimmer, Y. Safe handling practices to increase post-capture survival of cetaceans, sea turtles, seabirds, sharks, and billfish in tuna fisheries. Endanger. Species Res. 2019, 38, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easter, T.; Trautmann, J.; Gore, M.; Carter, N. Media portrayal of the illegal trade in wildlife: The case of turtles in the US and implications for conservation. People Nat. 2023, 5, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemelikova, A.; Chajma, P.; Ferasyi, T.R.; Awaluddin, A.; Fadli, N.; Sari, W.; Hof, C.; Riskas, K.; Vojar, J. Sea turtle exploitation in Sumatra, Indonesia: Disentangling the roles of religion, culture and socio-demographics to support effective conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.; Jiménez, V.; Ferreira-Airaud, B.; Pina, A.; Soares, V.; Tiwari, M.; Teodósio, M.A.; Castilho, R.; Nuno, A. Perceived social benefits and drawbacks of sea turtle conservation efforts in a globally important sea turtle rookery. Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 1185–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden Hof, C.A.; Smith, C.; Miller, S.; Ashman, K.; Townsend, K.A.; Meager, J. Delineating spatial use combined with threat assessment to aid critical recovery of northeast Australia’s endangered hawksbill turtle, one of western Pacific’s last strongholds. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1200986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olendo, M.I.; Okemwa, G.M.; Munga, C.N.; Mulupi, L.K.; Mwasi, L.D.; Mohamed, H.B.; Sibanda, M.; Ong’anda, H.O. The value of long-term, community-based monitoring of marine turtle nesting: A study in the Lamu archipelago, Kenya. Oryx 2019, 53, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, C.; Sethi, S.A.; Rice, A.N.; Warren, J.D.; Fujita, R.; Ingles, J.; Flores, J.; Garchitorena, E.; Mesa, S.V. Marine ecotourism for small pelagics as a source of alternative income generating activities to fisheries in a tropical community. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 261, 109242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Rosas, O.; Hernández-López, J.; Verduzco-Zapata, G.M.; Pérez-Morales, A.; García-Villalvazo, P.; Quijano-Scheggia, S.I.; Olivos-Ortiz, A. Citizen science contributions to the conservation of sea turtles facing port city and land use stressors in the Mexican Central Pacific. Coasts 2022, 2, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palash, M.S.; Haque, A.M.; Rahman, M.W.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Hossain, A. Economic well-being induced women’s empowerment: Evidence from coastal fishing communities of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means; R package version 1.8.9. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Lüdecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science; R package version 2.8.12. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Lüdecke, D.; Makowski, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.S.; Patil, I.; Waggoner, P. performance: Assessment of Regression Models Performance; R package version 0.10.8. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=performance (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Muggeo, V.M.R. segmented: An R package to fit regression models with broken-line relationships. R News 2008, 8, 20–25. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=segmented (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation; R package version 1.1.4. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 2 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.