Abstract

Unprecedented quantities of pelagic sargassum since 2011 have demanded technical and management responses. Inappropriate measures might worsen environmental impacts, particularly in low-income regions and protected natural areas that also require low-cost, socio-ecologically integrated alternatives. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness and local perception of sargassum clean-up treatments developed through a community–academic collaboration within a socio-ecological systems framework in the marine protected area Xcalak Reefs National Park (PNAX), at the southernmost Mexican Caribbean coast. In 2019 and 2021, clean-up efforts were implemented through the national PROREST program and a self-organized community group of 35–40 members supported by a multidisciplinary research advisory team. Monitoring in 2021 estimated sargassum removal at 4012 m2 over 50–75 work hours. Although average shoreline retreat was obtained (δmean = −0.22 m), final accretion of ~0.96 m alleviated community concerns about erosion linked to clean-up activities. The most effective and socially accepted clean-up treatment involved sargassum spreading, collection, drying, and revetment-type beach protection, reducing odors and harmful fauna. However, treatments aimed at shoreline stabilization were impractical, raising doubts about their long-term efficacy. These findings highlight the relevance of integrating ecological performance and social perception in sargassum management, especially where co-management with local communities in marine protected areas is needed.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, macroalgal blooms, particularly those of sargassum, have increased in frequency, scale, and global impact. These blooms have transformed coastal social-ecological systems, being considered a new type of natural disaster [1,2,3,4]. In the Caribbean, this issue is especially severe, with massive accumulations of pelagic sargassum creating persistent challenges since their significant onset in 2011 [5,6]. These events have disrupted ecological and biogeochemical processes across reef systems, beaches, wetlands, and coastal lagoons [7,8]. Sargassum accumulates in open waters, nearshore areas, and coastlines, causing environmental degradation, economic losses, and social burdens [9]. These impacts continuously threaten coastal ecosystems and communities [10,11,12,13].

The Mexican Caribbean first experienced major sargassum influxes in 2014 [14], with subsequent years showing increasing volumes [5,13,15], and documented impacts on coastal ecosystems [10,16,17,18,19]. Government, private, and civil society efforts have focused on methods and guidelines for sargassum management and removal strategies [20]. These include vessel-based collection, floating barriers, and mechanized or manual beach clean-up [12,13,21]. However, improper removal methods could damage beach ecosystems, alter profiles and cause soil compaction or erosion [22,23]. Also, insufficient knowledge of sargassum influxes has made management decisions difficult [24].

Most sargassum management efforts have prioritized massive tourism-based regions, central to the Caribbean economy [11,12]. However, these strategies are often unsuitable for economically constrained regions. Rural communities and natural protected areas in the southern Mexican Caribbean, lacking tourism revenue and private investment, remain particularly vulnerable. Although they experience similar or even greater sargassum influxes than northern tourist zones [25], they receive less institutional support. Their socio-ecological vulnerabilities are often underestimated due to smaller populations and limited infrastructure.

Community–academic collaborations have emerged as a powerful strategy integrating coastal residents’ traditional knowledge and scientific expertise to address sustainable responses to coastal challenges [26]. Public participation in scientific research and knowledge production—commonly framed as citizen science—has become an increasingly acknowledged approach across environmental and ecological sciences, as demonstrated by its global application in monitoring and management programs [27,28,29]. These partnerships enhance data collection, encourage community engagement, and support adaptive, locally relevant sargassum management [9]. Community participation has also proven essential for monitoring macroalgal blooms and informing policies [30]. Given that massive sargassum influxes are a relatively recent yet intensifying socio-ecological issue, it is critical to assess sargassum management alternatives that are technical, ecological, and economically feasible while considering community perception and collaboration.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness and local perception of sargassum clean-up treatments developed through a community–academic collaboration within a socio-ecological systems framework in Xcalak Reefs National Park (PNAX), a marine protected area on the southernmost Mexican Caribbean coast. The collaboration, implemented under the “Protection and Restoration of Ecosystems and Priority Species” (PROREST) program, considered the ecosystem restoration through locally driven sargassum clean-up treatments and monitoring. A design-thinking approach guided treatment development, which also aligned with PNAX management policies and incorporated ecological and social considerations. Effectiveness was assessed using quantitative indicators of community contributions to sargassum clean-up and shoreline displacements, addressing local concerns about erosion. Community perceptions were further documented to evaluate the social viability and acceptance of the implemented clean-up treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted within the PNAX, a marine protected area designated as a national park in 2000 [31,32] and recognized as a RAMSAR site by the Convention on Wetlands in 2003 [33]. The PNAX comprises interconnected ecosystems, including shallow tropical waters, coastal beaches, mangrove areas, tropical forests, and coral reefs (Figure 1). These habitats provide refuge for vulnerable or endangered marine and terrestrial species [34]. The primary local village within the PNAX is Xcalak, home to approximately 450 inhabitants living in a moderately marginalized socioeconomic context (i.e., in contrast to urban centers like Cancún) [35].

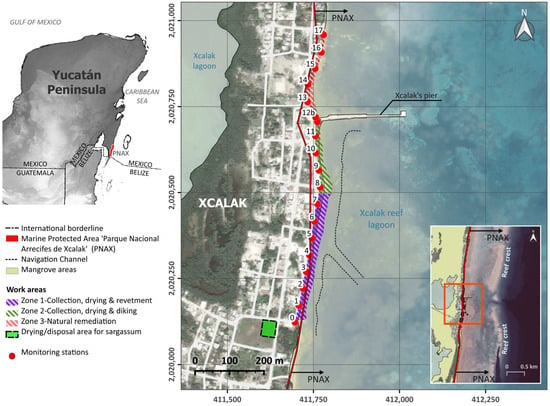

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in the southernmost Mexican Caribbean, near the Mexico–Belize border (WGS-84/UTM16N coordinates). The limits of Xcalak Reefs National Park (PNAX), mangrove area navigation channels, and designated work areas for sargassum clean-up activities conducted during 2019 and 2021 are also shown.

The Xcalak coast, oriented from south to north, is protected by a barrier reef that runs parallel to the shoreline. This natural barrier features a discontinuity of approximately 150 m wide, located near a concrete pier that extends ~250 m seaward (Figure 1). A dredged navigation channel is found within the reef lagoon, spanning 50–60 m in width with water depths of ~1.5 to 2.0 m. The channel connects to the open sea in front of the pier and roughly 400 m south of it, providing an anchorage area for fishing vessels (Figure 1).

The study area, where clean-up treatments were tested, comprised a 900 m section of Xcalak’s coastline (Figure 1). This area serves as the primary beach for the community’s social and economic activities. It is also featured by extensive mangrove areas and coastal dunes that host native flora species such as Sesuvium portulacastrum, Cordia sebestena, Ipomea sp., Canavalia rosea, and Cocoloba uvifera. Invasive species like coconut palms (Cocos nucifera) and casuarinas (Casuarina equisetifolia) are also present. Vegetation intermingles with sandy areas and dwellings established along the shoreline, with the village’s main thoroughfare located less than 20 m from the backshore.

2.2. Community–Academic Collaboration and Perception

In 2019 and 2021, a community group from Xcalak applied for funding through PROREST, a national public program coordinated by the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP) at PNAX [36]. The self-organized group of 35–40 members aimed to carry out sargassum clean-up activities in response to coastal erosion, unpleasant odors, and disruption of coastal activities. Unlike other public programs such as the Temporary Employment Program (PET in Spanish), which provides direct economic support to individuals affected by adverse events like massive sargassum influxes, the PROREST program promotes conservation and restoration through active community participation.

Following CONANP’s recommendation to the community’s proposal, technical support was requested in 2019 to encourage collaboration between the community and academic institutions. Planning workshops in early 2019, led by CONANP, were held between researchers and community members to identify local needs and challenges. From these discussions, a Design-Thinking approach [37,38] was adopted to empathize, ideate, implement, and evaluate sargassum clean-up alternatives. This approach was embedded in a socio-ecological systems framework [39], based on the Resource System Approach [40], which integrates natural, social, and management system components.

The research advisory group—specialized in oceanography, marine ecology, and coastal engineering—translated workshop outcomes into practical actions, tailored to local conditions and PROREST objectives. Three key priorities were identified for sargassum management and monitoring of its impacts:

- (i)

- Baseline beach characterization using field observations, photographic records and community descriptions to assess natural conditions and past changes.

- (ii)

- Critical zone identification for developing sargassum clean-up treatments based on sargassum accumulation and impacts on primary community-use beaches.

- (iii)

- Mitigation of management impacts, addressing prior clean-up practices that caused sand loss, improper storage, unpleasant odors, leachates, disruptions to coastal activities, and the spread of harmful fauna.

From (i), (ii) and (iii), the beach was divided by the advisory research group into specific zones for implementing different clean-up treatments. Methods such as manual beach sargassum scraping [41], or nature-based shore revetments were considered [42]. During a workshop (9 August 2019) the advisory group presented technical alternatives, tools, work schedules, cost-effective practices, and scientific background on sargassum influxes. Initiatives from community members to engage in these efforts were regarded as suggestions for the implementation of the treatments.

As the funding source, CONANP supervised initial implementation of the clean-up activities. Further field supervision and follow-up meetings were held between CONANP, the community and the advisory research group (12–16 September 2019). Final joint decisions on the clean-up methods were made during a meeting and field observation sessions (26–30 September 2019). A project closure meeting was held on 10 December 2019, attended by CONANP, the community and the advisory research group. Outcomes offered recommendations and highlighted achieved benefits.

No clean-up occurred in 2020 due to COVID-19 restrictions, but a renewed PROREST proposal was submitted in 2021, integrating monitoring efforts. A coordination meeting on 15 September 2021 brought together the community group, CONANP, PNAX rangers, PROREST coordinators, and the advisory research team. This also included the first training session, based on a community participatory approach, for monitoring sargassum arrival and shoreline changes associated with the treatments. Technical guidance from the advisory research group was provided throughout project implementation.

By the end of the project, community perceptions were assessed during the final workshop held on 8 December 2021. These perceptions were understood as expressions of human-environment interactions shaped by internal and external factors [43,44] to evaluate social acceptance and perceived effectiveness of clean-up treatments. Each of the 35 community members involved in the clean-up activities completed an evaluation matrix presented on a board during the workshop. The matrix employed a 5-point Likert scale for each evaluated item [45]: ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘neither’, ‘agree’, and ‘strongly agree’. Survey items addressed key aspects of the clean-up treatments, such as the prevention of sand extraction, appropriate sargassum storage, reduction in unpleasant odors, minimization of disruptions to coastal activities, avoidance of leachates, beach condition assessment, generation of economic benefits, community engagement, and overall feasibility of clean-up treatment efforts. For each clean-up treatment and its items, response frequencies on the Likert scale were registered, and percentages were calculated for each category. All participants provided informed consent, and the activity complied with CONANP’s ethical guidelines. Additionally, community members shared opinions about the treatments’ implementation. The feedback helped to identify the most suitable approach for the community following the methods described by [46].

The analysis evaluated the perceived social applicability, including the utility of acquired knowledge and potential conflicting motivations [47]. This is closely related to the community satisfaction with the sargassum clean-up treatments and the social benefits and constraints influencing implementation success.

2.3. Clean-Up Efforts: Monitoring of Sargassum Influxes and Shoreline Changes

Best practices for sargassum clean-up identified in 2019 were further implemented in 2021. These practices were accompanied by monitoring activities designed to: (a) assess sargassum extent and shoreline changes during community work journeys; (b) quantitatively evaluate changes in relation to the clean-up treatments applied; and (c) differentiate the effects of clean-up treatments (i.e., sargassum removal and shoreline displacements) from natural environmental variations. The monitoring followed a participatory community-based approach adapted from [48]. For this purpose, 17 georeferenced fixed monitoring stations were established between 6 October and 8 December 2021, along Xcalak’s shoreline at regular 50 m intervals (Figure 1). Measurements of sargassum influxes and shoreline changes were taken during 25 monitoring surveys (n = 25) within the working period. Field measurements were conducted by nine trained community collaborators under the technical guidance of researchers.

The position of the shoreline and the sargassum extent from the shoreline seaward were measured relative to the fixed monitoring stations. The sargassum extent (SEi,j) at the ith station and jth survey was calculated according to Equation (1), with measurements taken before (SEi,j,before) and after (SEi,j,after) the application of the clean-up treatment within a journey. This allowed the identification of sargassum removal or influx within the journey. A negative SEi,j value indicates sargassum clean-up during the survey, whereas a positive value reflects the influx of new sargassum. The difference between the minimum (SEi,j,min) and maximum (SEi,j,max) sargassum extent at each survey was also evaluated.

The average sargassum extent (SEAv) and the total accumulated (SEAcc) during the monitoring period were also calculated (Equations (2) and (3)). The average area of the cleaned-up sargassum (AAv) and its total extension (AAcc) were calculated by multiplying SEAv and SEAcc by the distance between monitoring stations (i.e., 50 m). The volume of the sargassum (VAcc) over the monitoring period was estimated by multiplying AAcc by an assumed sargassum layer thickness of 0.05 m, which corresponded to the typical thickness of a sargassum layer in the area.

Shoreline changes were measured simultaneously considering a community concern related to the coastal erosion, possibly related to clean-up activities [2]. Thus, the shoreline position was measured at each station before the commencement of clean-up treatment activities at each survey. Shoreline displacement was assessed using as a reference the initial shoreline position at each ith station on 6 October 2021 (i.e., δi,0). The shoreline displacement (Δδi,j) at any given station and date was then calculated by subtracting δi,0 from the shoreline position at the jth survey (δi,j) (Equation (4)):

The mean shoreline displacement (δmean) was calculated for each monitoring station by averaging the Δδi,j values. Additionally, the final shoreline position (δi,final) is reported to indicate the final advance or retreat of the shoreline at the end of the monitoring period. The range of shoreline changes (Δδmax) at each station was also examined, considering the difference between the maximum and minimum Δδi,j values at each location.

3. Results

3.1. The Sargassum Clean-Up Treatments

The final clean-up treatments resulted from adjustments based on the experiences gained during 2019. A schematic representation of the treatments applied is provided in Figure 2. In accordance with PNAX’s conservation and natural protection policies, no heavy machinery was used to prevent soil compaction. Consequently, basic manual tools such as wheelbarrows, rakes, pitchforks, shovels, ropes, tape measures, levels, cameras, and notebooks were used. This approach facilitated the adoption of low-cost monitoring actions and clean-up activities suitable for rural Caribbean coastal communities, in contrast to the resource-intensive methods used by local government and the tourism sectors in the northern Mexican Caribbean coast [49].

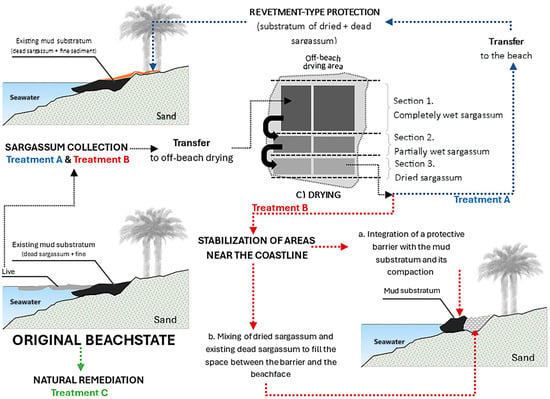

Figure 2.

Clean-up treatments applied along the designated work areas. Common activities related to sargassum collection and drying are shown with black arrows. Blue arrows represent specific activities unique to treatment A, while red arrows denote those for Treatment B. Natural remediation was only monitored in treatment C.

An advisory for organizing the community into brigades enabled the efficient implementation of the clean-up activities. Each brigade, consisting of 7–10 individuals, was assigned specific tasks: (a) collecting live sargassum from nearshore waters, (b) transporting the sargassum to designated disposal areas or spreading it over the beach face, (c) managing the drying process from wet to desiccated material, (d) mixing dry sargassum with existing decomposed organic matter on the beach to reinforce the beachfront, and (e) recording field measurements.

The clean-up treatments were spatially distributed along the beachfront to address localized issues (Figure 1). This zoning strategy was guided by community observations concerning shoreline erosion, excessive sargassum accumulation, interference with local activities, and the varying levels of effort required for each treatment:

- Treatment A. Sargassum spreading, collection, drying, and revetment-type beach protection. This treatment received the highest level of community approval due to its “natural cycle” approach for sargassum management. It consisted of collecting sargassum, transporting it to designated areas for drying and natural aeration, and later reintegrating it into the beachfront as a protective revetment layer (Figure 2). Zone 1 was chosen for implementing this treatment, as it was expected to experience limited shoreline displacements due to reef protection. It also met community preferences for short transport distances between work and drying sites (i.e., <500 m) (Figure 1). The collection process primarily focused on live sargassum floating nearshore, minimizing sand adhesion and reducing potential beach erosion. Unlike the common practice prior to 2019 that involved piling sargassum into mounds (Figure 3), this method emphasized spreading sargassum in thin layers (<0.10 m thick) across designated drying/disposal areas (Figure 1).

Figure 3. Images showing the different working zones with contrasts between the initial, intermediate and final conditions of the coastline, as well as of the community’s organization and involvement.This treatment qualitatively succeeded in reducing unpleasant odors, harmful fauna, and heat associated with decomposition while facilitating aeration and sun drying (Figure 2). Once dried, the sargassum was reincorporated into the beach face to serve as a protective revetment layer. Using the beach face as a drying site also minimized transportation needs, improving overall efficiency.

Figure 3. Images showing the different working zones with contrasts between the initial, intermediate and final conditions of the coastline, as well as of the community’s organization and involvement.This treatment qualitatively succeeded in reducing unpleasant odors, harmful fauna, and heat associated with decomposition while facilitating aeration and sun drying (Figure 2). Once dried, the sargassum was reincorporated into the beach face to serve as a protective revetment layer. Using the beach face as a drying site also minimized transportation needs, improving overall efficiency. - Treatment B. Sargassum collection, drying, and stabilization of areas near the shoreline. The activities under this treatment aimed to mitigate coastal erosion caused by wind-driven waves in Zone 2 (Figure 1), where no reef protection exists. A secondary goal was to preserve the integrity of existing plant root systems. The sargassum collection and drying methods employed followed the same principles as Treatment A but focused on using dried sargassum to create a protective barrier (Figure 2). The strategy combined decomposing sargassum—which normally forms a muddy substrate along the shoreline and is left in place due to its sand and fine material content—with freshly dried sargassum. This mixture produced a workable substratum to build a barrier ~1 m parallel to the shoreline and 0.20 m above the water level. The space between the barrier and the beach was filled with layers composed of a combination of dry sargassum and the existing sargassum–sand mixture. Regular maintenance was necessary to prevent the barrier from being washed away by wave action.

- Treatment C. Natural clean-up and observation. The treatment was implemented in Zone 3, an area without settlements or beaches but containing sparse mangrove patches. This approach involved the passive observation of the natural clean-up and sargassum influx process without human intervention.

The clean-up treatments facilitated environmental recovery and enhanced the community’s organizational capacity (Figure 3). Consequently, the treatments developed in 2019 were replicated in 2021 and continued to be implemented in areas with a self-organized community (Figure 3, top panels).

Guidance provided to the community proved effective for managing sargassum influxes. Before the treatments, clean-up practices involved complete removal of sargassum, which often worsened shoreline erosion. Additionally, decomposing sargassum mixed with sand formed mounds associated with foul odors, heat, and pests. Comparative observations across project stages showed that reintegrating sargassum into the landscape contributed to the recovery of the sand beach face, serving as a protective layer. After natural events (e.g., rain or rising water) or selective removal, the beach remained stable. Key elements identified for managing massive influxes included: (i) continuous sargassum and litter removal; (ii) designation of specific areas for sargassum drying and disposal; (iii) extraction before contact with beach sand; (iv) preservation of native vegetation and promotion of coastal dune reforestation; and (v) systematic monitoring of shoreline changes and clean-up efforts.

3.2. Sargassum Collection and Shoreline Displacements

The monitoring actions implemented in 2021, comprising 25 surveys, enabled the estimation of the mean sargassum removed/accumulated (SEAv), the cross-shore distance of total sargassum extent (SEAcc), area (AAcc) and volume (VAcc), as well as the mean (δmean), final (δfinal) and range of shoreline displacements (Δδmax) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of shoreline displacements of the mean sargassum removed per survey (), as well as cross-shore distance (), area () and volume () of total sargassum removed in 2021. The mean (δmean), final (δfinal) and range of maximum shoreline changes (Δδmax) are also shown.

During the analyzed period, the removed sargassum covered a total area of 4012 m2 and a total volume of VAcc ~ 208.1 m3, considering only the working hours of the monitoring surveys. Sargassum removal was concentrated in the zones where treatments A and B were implemented (i.e., negative values in Table 1). The mean total sargassum removed per station was between 258 and 288 m2, primarily due to the community’s clean-up efforts. In Zone 3, the mean Sargassum removal per survey was minimal (32.3 m2), highlighting the contrast between natural and active clean-up approaches.

Treatments A and C showed comparable levels of final shoreline displacement, with values of 0.43 ± 0.9 m and 0.58 ± 0.4 m, respectively. The higher standard deviation observed in Zone 1 suggests greater spatial variability in shoreline displacement among stations in that area. In Zone 2, where treatment B was applied due to increased wave impact effects, a final inland shoreline displacement (δmean = −0.49 m) was recorded. The range of shoreline changes (Δδmax= 5.74 m) was 1.5 times higher than in Zones 1 and 3, reflecting stronger hydrodynamic influence.

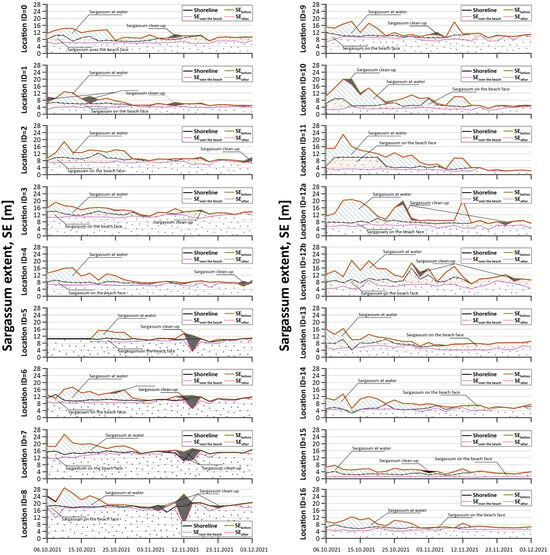

The time series of sargassum conditions from October to December 2021 in Figure 4 shows measured values of and , along with observed shoreline displacements. The community’s effective sargassum clean-up efforts and the redistribution of sargassum over the beach face are also identifiable. Furthermore, natural fluctuations in the extent of sargassum in nearshore waters indicate temporal variations in sargassum influxes, with notable decline toward the end of October 2021.

Figure 4.

Time series describing the sargassum extent and shoreline variation at each ID location along the Xcalak beachfront from October to December 2021. Sargassum present in water is denoted by green backwards slashes, while sargassum on the beach face is represented by orange forward slashes. Areas where sargassum removal occurred, whether through natural processes or artificial interventions, are shaded in gray.

During the initial period (6–20 October 2021), sargassum clean-up activities were concentrated in Zones 1 and 2, particularly at locations ID = 1 and ID = 10. This resulted in a significant reduction in the extent of seaward sargassum. During the first surveys, the sargassum was spread across the beach face. Subsequently, the landward sargassum extent stabilized, especially between locations ID = 1 and ID = 11, where treatments A and B were applied. After 23 October, the shoreline displacement became negative, particularly at ID = 10 and ID = 11 in Zone 2, limiting the potential for further sargassum spread along the beach face. Sargassum spread displayed greater variability at ID = 12b and ID = 13, closer to Xcalak’s pier, while it remained minimal at ID = 14–16, where natural clean-up (treatment C) was applied.

Increased sargassum influxes were observed before 28 October 2021, with peaks around 9 October and between 20 and 26 October. An important natural reduction in sargassum inside water was recorded after 28 October. However, a new peak in sargassum influxes and accumulation was recorded from ID = 5 to ID = 12b between 10 and 13 November. After 13 November, natural processes cleared sargassum from all monitored sites along the Xcalak coastline.

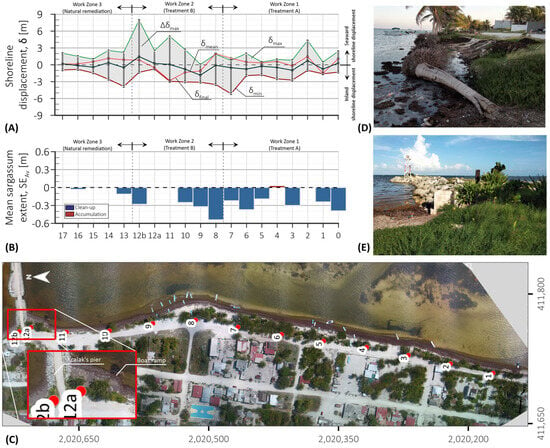

The results (between October and December 2021) of the mean, maximum, and range of shoreline displacements per location and comparison with the mean sargassum removal/accumulation are given in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Shoreline displacements considering the measurements of 10.06.2021 as a reference. (A) Maximum inland (δmin), seaward (δmax), mean (δmean) and final (δfinal) shoreline displacements, as well as maximum range of shoreline changes (Δδmax) per point location. (B) Average sargassum clean-up/accumulation during the monitoring period. (C) Aerial drone image of Xcalak’s coastline taken in 2023 (WGS-84/UTM16N coordinates). (D) Images depicting coastal erosion insights at ID = 12a and (E) shoreline stabilization from pioneer vegetation at ID = 12b in 2021.

Shoreline displacement during the monitoring period displayed considerable variability. Inland (negative) shoreline displacements reached an average of δmean = −1.84 m, while seaward (positive) shoreline displacements reached δmean = 1.46 m (Figure 5). The largest negative δmean value was observed at ID = 9, where a concave shoreline shape started to develop. A general trend of negative shoreline displacements was identified, primarily concentrated in Zone 1 and the southern section of Zone 2 (ID = 3–9). In these areas, SEAcc values were positive, indicating that sargassum clean-up could have contributed to the shoreline retreat.

Treatments that involved the reincorporation of dried sargassum onto the beachfront followed several cycles of accumulation, removal, and reapplication, ultimately resulting in a final shoreline positive displacement. This is evidenced by the differences between δmean and δfinal, reflecting the final state of the beach following the last reincorporation of sargassum in December 2021 (Table 1).

By the end of the monitoring period, a final seaward shoreline displacement (δfinal > 1.0 m) was recorded at sites ID = 0, 2, and 7–11. For the remainder of the monitored area, positive shoreline displacements were in the range 0.0 < δfinal < 1.0 m, remaining relatively uniform along Zone 1, particularly at sites ID = 3–6.

A significant negative final shoreline displacement occurred in Zone 2, with maximum δfinal = −2.80 m. This finding indicates intensified shoreline retreat near Xcalak’s pier (Figure 5C), where the coastline lacks direct reef protection (Figure 1 and Figure 5A,C). This shoreline retreat is mainly attributed to the collapse of palm trees (Figure 5D), which resulted from a weakened root system under continuous wave exposure, thus diminishing their stabilizing effect on the shore. While some vegetation regeneration was observed near the palm trees (Figure 5D), erosion outpaced stabilization efforts. Notably, after field visits in 2022 and 2023 at ID = 12a, remnants of an old concrete boat ramp were exposed (Figure 5C), potentially marking the location of a former and historical shoreline position.

A greater positive shoreline displacement was observed at ID = 12b, located adjacent to the northern side of the Xcalak pier. This area presented work restrictions due to the pier’s infrastructure and described a notable sargassum accumulation in 2019 and 2021 (Figure 5E). The shoreline at ID = 12b was vegetated with grass and pioneer native species and benefited from partial shelter provided by the pier structure. In this regard, important shoreline displacements were recorded at distances between 20 and 100 m from the pier, with maximum displacement ranges of Δδ = 7.95 m and Δδ = 9.19 m (Figure 5A). This variability likely results from local hydrodynamic conditions around the pier structure, combined with limited protection from the reef barrier.

The mean sargassum removal activities reached their maximum at ID = 8 (Figure 5B), though clean-up efforts were constrained to avoid potential conflicts with fishery-related activities. Nevertheless, sargassum removal efforts concentrated south of Xcalak’s pier (Figure 5B), mostly due to the proximity of the designated drying area and the availability of a beach face for spreading the sargassum.

3.3. Community Group Perception

Treatment A was the most accepted approach, with 83% of participants selecting “strongly agree” or “agree” (Table 2). In contrast, Treatments B and C received only 22.5% and 26% agreement, respectively. Treatment A stood out for its effectiveness in “minimizing unpleasant odors” and supporting the continuation of activities, both rated 100% as “strongly agree.” These same aspects received mixed ratings for Treatments B and C.

Table 2.

Results from the community perception analysis (n = 35). Columns describe the question (parameter) assessed, and rows indicate the average ratings (as percentages) for each treatment. The ‘total’ column shows the average percentage across rating categories.

Treatment C achieved more than 91% agreement for “avoiding sand extraction” and “beach has improved,” reflecting environmental benefits. However, community engagement was low due to the passive nature of the method. Treatment B showed perceived benefits only at the individual level, with agreement on “my income has improved” and “my social activity has diversified.”

Community perceptions combined optimism and caution. Several participants valued the actions—especially proactive sargassum removal—for preventing odors and promoting local, self-organized solutions. These efforts increased awareness of coastal ecosystems supported by cognitive and social engagement. Economic and social benefits also strengthened community ties. However, concerns arose over the need for more effective methods, better understanding of resilient ecosystems, and responsible resource management. While Treatment A inspired confidence, Treatment B was hindered by wave damage to protective barriers, which reduced its perceived effectiveness despite recognition of its purpose. Challenges did emerge, leading to a more cautious outlook. The necessity for a more efficacious clean-up methodology, a deeper comprehension of resilient ecosystem processes, and the prudent administration of financial and technical resources by funders were identified as areas of concern.

In summary, Treatment A was met with widespread acceptance and strengthened community confidence among the proposed treatments, whereas Treatment B encountered setbacks. The persistent wave damage to the protective barriers limited their effectiveness, leading the community to perceive these efforts as ultimately futile despite acknowledging their importance in shoreline protection.

4. Discussion

This study explored a community–academic collaboration embedded within a socio-ecological systems framework. This collaboration contributed to the design, implementation, and appraisal of sargassum management strategies in the marine protected area of the PNAX. Unlike conventional top-down interventions, this initiative was built on community-led project proposals to the national public PROREST program [36], emphasizing community involvement for environmental conservation. It contrasts with reactive assistance programs such as PET and aligns more closely with long-term initiatives like PROCODES (i.e., Conservation Program for Sustainable Development). Despite their relevance, only 19% of publications related to PROREST or PROCODES are of practical application [50]. Therefore, the co-developed, context-sensitive, low-impact sargassum management strategies herein described sum up to address and document local priorities and mitigate ecological and social impacts.

The design-thinking approach used in this study was novel to all participants (including the community and the multidisciplinary research group) to reach the target goal. The community–academic collaboration evolved along the project (2019–2021) towards more reflexive practices as similarly described in [51] and favored by the specific contextual condition [52]. This collaborative approach not only built local capacities but also enhanced perceptions of co-management, as described by [53], and promoted local governance [54]. The project’s complexity stems from the need to account for anthropogenic impacts and social perception; however, it should be recognized that environmental factors could simultaneously disrupt the ecosystem’s resilience [55].

The derived indicators in 2021, related to sargassum extent (4012 m2) [56] showed the operational feasibility of these methods. Zones treated with active clean-up strategies (Treatments A and B) showed more pronounced shoreline displacements, both inland and seaward, than zones left to natural processes (Zone 3). Although a mean shoreline retreat (δmean = −0.22 m) was registered, a final shoreline accretion of ~0.96 m was observed by the end of the study period, a positive result on preserving the natural beach profile. Several factors, including the chosen clean-up treatments, collectively shaped the area’s final condition (Figure 5). Community observations highlighted the impact of natural, temporal variations in waves, currents, and wind on sargassum influx or removal. This aligns with [57], who reported that high-energy events, marked by strong waves and winds, often remove sargassum from northern Mexican beaches, while low-energy conditions, associated with eastern winds, tend to promote its influx and accumulation.

Local communities are normally aware of the marine and coastal disturbances but could lack the technical or holistic background to support their perception and knowledge [56]. Therefore, monitoring is a valuable tool found to be required to further develop adaptive management actions [58].

The reincorporation of dried sargassum onto the beach (Treatment A) proved to be the most effective and gained the highest community approval. The method appears to play a significant role in stabilizing and even advancing the shoreline seaward, particularly when applied consistently over time. This practice, as evidenced by differences between δmean and δfinal, offers a promising nature-based solution for shoreline maintenance. In contrast, Treatment B faced practical limitations, whereas passive approaches such as Treatment C were associated with prolonged negative impacts on local activities. Similar outcomes have been documented in other studies [1,13]. Thus, results highlight the relevance of community participation and collaboration processes, particularly in marine protected areas [59]. Also, findings reinforce the need for timely, community-tailored interventions in ecologically sensitive yet underserved coastal zones in marine protected areas [60].

The participatory monitoring approach, adapted from [48], strengthened community ownership, enhanced trust in scientific processes, and promoted adaptive learning. The estimated clean-up cost was USD 78 per m3, derived from the average removed sargassum during working hours (VAcc = 200.6 m3) and the PROREST project funding provided (~USD 15650). This investment relates to advisory and technical guidance, as well as materials to perform both specific local clean-up and monitoring activities. Community members’ personal incomes are also considered within the overall cost provided. This estimate remains competitive compared with government-led initiatives, demonstrating the cost-efficiency of community-driven responses in resource-limited contexts under collaborative and informed frameworks [49]. Further sargassum clean-up methods could be enhanced by introducing Littoral Collection Modules as proposed by [12], to facilitate effective water-based clean-up efforts, rather than focusing solely on land-based methods.

Finally, structured collaboration improved environmental outcomes and community acceptance. Future research should develop integrative frameworks, for which further collaborations from different sectors are needed (e.g., economic or health areas). Such cooperation could bring different elements to overcome complex-related problems, accepting social involvement, breaking interdisciplinary scientific barriers, and generating social capital and cohesion [61] while fostering community and environmental resilience through adaptive and evidence-based practice.

5. Conclusions

This study showed how a community–academic collaboration can enable effective and locally adapted sargassum management in natural protected coastal areas. Participatory design, technical monitoring, and perception analysis ensured ecologically and socially acceptable sargassum clean-up methods. Collaboration among local actors and researchers, backed by PROREST funding and government support, fostered knowledge exchange, trust, and lasting community engagement. Currently (2025), sargassum clean-up treatments are still implemented by the Xcalak community.

By transforming sargassum from an uncontrolled issue into a shared management challenge, the study showed that local communities could strengthen coastal resilience through adaptive, evidence-based practices. Findings show that simple, low-impact treatments, including monitoring and perception-based feedback, could be useful to mitigate negative effects linked to sargassum influxes. Quantitative and qualitative indicators based on community participation approaches identified best practices appropriate to the local context while also flagging socially unfeasible methods. Implications for sargassum clean-up practice could therefore be strengthened by:

- Promoting the role of community groups and scaling participatory frameworks for sargassum management and monitoring in similar protected and rural areas, especially where institutional response is limited.

- Supporting community–academic collaborations that integrate scientific guidance with local knowledge to co-design context-specific management strategies and adaptive coastal governance.

- Prioritizing nature-based, low-cost solutions to enhance coastal resilience and community livelihoods in natural protected areas.

- Aligning funding mechanisms with ecological and social outcomes, reorienting national public programs considering community and academic initiatives. This could incentivize long-term restoration, social acceptance, transparency, and responsibility.

These outcomes suggest that sargassum clean-up strategies are most effective when tailored to site-specific ecological conditions and community priorities. As sargassum influxes are expected to intensify with changing ocean conditions, future policies should embed participatory, ecosystem-based approaches into broader coastal management plans. Therefore, management requires context-specific approaches, as effectiveness depends on factors such as biomass, site accessibility, ecological sensitivity, coastal hydrodynamics, and local socioeconomic activities [22]. Several Caribbean countries have adopted learning-by-doing approaches [62,63], achieving mixed results depending on the urgency of mitigation needs. A global vision on clean-up treatments is also needed, since similar removal practices are not exclusive to sargassum. Comparable strategies have been applied for Posidonia oceanica removal on Mediterranean beaches [64,65] and for marine debris management in Southeast Asia [66]. In this regard, the Xcalak case provides a valuable model for bottom-up environmental management within marine protected areas and local communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M., M.E.C.-J. and L.C.; methodology, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M., M.E.C.-J. and V.G.-G.; software, J.C.A.-H. and O.F.R.-M.; validation, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M. and M.E.C.-J.; formal analysis, J.C.A.-H. and M.E.C.-J.; investigation, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M. and L.C.; resources, O.F.R.-M. and L.C.; data curation, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M. and V.G.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M. and V.G.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.C.A.-H., O.F.R.-M., M.E.C.-J., V.G.-G. and L.C.; visualization, J.C.A.-H. and O.F.R.-M.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, L.C.; funding acquisition, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by the Xcalak community, which receives resources from Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas—Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Xcalak, PRODERS PROREST/CC/258/2021. The APC was funded by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration with the Xcalak community and the involvement of CONANP through their support during the study and project development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- García-Sánchez, M.; Graham, C.; Vera, E.; Escalante-Mancera, E.; Álvarez-Filip, L.; van Tussenbroek, B.I. Temporal Changes in the Composition and Biomass of Beached Pelagic Sargassum Species in the Mexican Caribbean. Aquat. Bot. 2020, 167, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louime, C.; Fortune, J.; Gervais, G. Sargassum Invasion of Coastal Environments: A Growing Concern. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 13, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.M.; Taylor, M.; Huston, G.; Goodwin, D.S.; Schell, J.M.; Siuda, A.N.S. Pelagic Sargassum Morphotypes Support Different Rafting Motile Epifauna Communities. Mar. Biol. 2021, 168, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Martínez, A.; Berriel-Bueno, D.; Chávez, V.; Cuevas, E.; Almeida, K.L.; Fontes, J.V.H.; van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Mariño-Tapia, I.; Liceaga-Correa, M.d.l.Á.; Ojeda, E.; et al. Multiscale Distribution Patterns of Pelagic Rafts of Sargasso (Sargassum spp.) in the Mexican Caribbean (2014–2020). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 920339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Mitchum, G.; Lapointe, B.; Montoya, J.P. The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Science 2019, 365, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, C. Mapping and Quantifying Sargassum Distribution and Coverage in the Central West Atlantic Using MODIS Observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 183, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Medina-Valmaseda, A.E.; Blanchon, P.; Monroy-Velázquez, L.V.; Almazán-Becerril, A.; Delgado-Pech, B.; Vásquez-Yeomans, L.; Francisco, V.; García-Rivas, M.C. Faunal Mortality Associated with Massive Beaching and Decomposition of Pelagic Sargassum. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Roy, P.D.; Torrescano-Valle, N.; Cabanillas-Terán, N.; Carrillo-Domínguez, S.; Collado-Vides, L.; García-Sánchez, M.; van Tussenbroek, B.I. Element Concentrations in Pelagic Sargassum along the Mexican Caribbean Coast in 2018–2019. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, K.; Garcia-Quijano, C.; Jin, D.; Dalton, T. Perceived Sargassum Event Incidence, Impacts, and Management Response in the Caribbean Basin. Mar. Policy 2024, 165, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, V.; Uribe-Martínez, A.; Cuevas, E.; Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Francisco, V.; Estévez, M.; Celis, L.B.; Monroy-Velázquez, L.V.; Leal-Bautista, R.; et al. Massive Influx of Pelagic Sargassum spp. on the Coasts of the Mexican Caribbean 2014–2020: Challenges and Opportunities. Water 2020, 12, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, L.A.; Li Ng, J.J. El Riesgo Del Sargazo Para La Economía y Turismo de Quintana Roo y México. BBVA Res. 2020, 20, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, L.A.; Bisonó León, A.G.; Rojas, F.E.; Veroneau, S.S.; Slocum, A.H. Caribbean-Wide, Negative Emissions Solution to Sargassum spp. Low-Cost Collection Device and Sustainable Disposal Method. Phycology 2021, 1, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Jordán-Dahlgren, E.; Hu, C. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Pelagic Sargassum Landings on the Northern Mexican Caribbean. Remote Sens. Appl. 2022, 27, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Jordán-Dahlgren, E. Afluencia Masiva de Sargazo Pelágico a La Costa Del Caribe Mexicano (2014–2015). In Florecimientos Algales Nocivos en México; Mendoza, E., Quijano-Scheggia, S.I., Olivos-Ortiz, A., Núñez-Vázquez, E.J., Eds.; CICESE: Ensenada, México, 2016; pp. 352–365. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Verdejo, J.; Lazcano-Hernandez, H.E.; Cabanillas-Terán, N. ERISNet: Deep Neural Network for Sargassum Detection along the Coastline of the Mexican Caribbean. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Hernández Arana, H.A.; Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Espinoza-Avalos, J.; Canizales-Flores, H.M.; González-Godoy, C.E.; Barba-Santos, M.G.; Vega-Zepeda, A.; Collado-Vides, L. Severe Impacts of Brown Tides Caused by Sargassum spp. on near-Shore Caribbean Seagrass Communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 122, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas-Terán, N.; Hernández-Arana, H.A.; Ruiz-Zárate, M.-Á.; Vega-Zepeda, A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, A. Sargassum Blooms in the Caribbean Alter the Trophic Structure of the Sea Urchin Diadema antillarum. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, L.C.; Hertkorn, N.; McDonald, N.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Del Vecchio, R.; Blough, N.V.; Gonsior, M. Sargassum sp. Act as a Large Regional Source of Marine Dissolved Organic Carbon and Polyphenols. Glob. Biogeochem Cycles 2019, 33, 1423–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Quintana-Pali, G.; Trujano-Rivera, K.I.; Herrera, R.; García-Rivas, M.d.C.; Ortíz, A.; Castañeda, G.; Maldonado, G.; Jordán-Dahlgren, E. Sargassum Landings Have Not Compromised Nesting of Loggerhead and Green Sea Turtles in the Mexican Caribbean. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEMARNAT-INECC. Lineamientos Técnicos y de Gestión Para La Atención de La Contingencia Ocasionada Por Sargazo En El Caribe Mexicano y El Golfo de México; SEMARNAT-INECC: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Desrochers, A.; Cox, S.A.L.; Oxenford, H.A.; van Tussenbroek, B. Pelagic Sargassum—A Guide to Current and Potential Uses in the Caribbean; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-137320-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, C.; Oxenford, H.; Cumberbatch, J.; Fardin, F.; Doyle, E.; Cashman, A. Golden Tides: Management Best Practices for Influxes of Sargassum in the Caribbean with a Focus on Clean-Up; Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies (CERMES)-The University of the West Indies: Cave Hill Campus, Barbados, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti, R.A.; Feagin, R.A.; Huff, T.P. The Role of Sargassum Macroalgal Wrack in Reducing Coastal Erosion. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 214, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plank, S.; Cox, S.-A.; Cumberbatch, J.; Mahon, R.; Thomas, B.; Tompkins, E.L.; Corbett, J. Polycentric Governance, Coordination and Capacity: The Case of Sargassum Influxes in the Caribbean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 50, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Hernández, J.A.; Enriquez, C.; Zavala-Hidalgo, J.; Cuevas, E.; van Tussenbroek, B.; Uribe-Martínez, A. Sargassum Transport towards Mexican Caribbean Shores: Numerical Modeling for Research and Forecasting. J. Mar. Syst. 2024, 241, 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celliers, L.; Mañez Costa, M.; Rölfer, L.; Aswani, S.; Ferse, S. Social Innovation That Connects People to Coasts in the Anthropocene. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futures 2023, 1, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittinger, J.N.; Bambico, T.M.; Minton, D.; Miller, A.; Mejia, M.; Kalei, N.; Wong, B.; Glazier, E.W. Restoring Ecosystems, Restoring Community: Socioeconomic and Cultural Dimensions of a Community-Based Coral Reef Restoration Project. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.; Campbell, L.; Norwood, C.; Ranger, S.; Richardson, P.; Sanghera, A. Putting Stakeholder Engagement in Its Place: How Situating Public Participation in Community Improves Natural Resource Management Outcomes. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, V.J.; Colla, S.R. Power of the People: A Review of Citizen Science Programs for Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 249, 108739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, R.E.J.; Alboiu, V.; Chaudhary, M.; Corbett, R.A.; Quanz, M.E.; Sankar, K.; Srain, H.S.; Thavarajah, V.; Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. Reducing Marine Pollution from Single-Use Plastics (SUPs): A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOF. Decreto Por El Que Se Declara Área Natural Protegida Con El Carácter de Parque Nacional, La Región Conocida Como Arrecifes de Xcalak, Que Se Encuentra Localizada En La Costa Caribe Del Municipio de Othón P. Blanco, En El Estado de Quintana Roo; Secretaría de Gobernación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CONANP-SEMARNAT. Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Xcalak; CONANP-SEMARNAT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- RAMSAR. Servicio de Información Sobre Sitios Ramsar. Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Xcalak. Available online: https://rsis.ramsar.org/es/ris/1320 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- López Jiménez, L.N. Conservación En El Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Xcalak. Teoría Y Prax. 2017, 13, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Principales Resultados Del Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020-Quintana Roo; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CONANP. Programa Para La Protección y Restauración de Ecosistemas y Especies Prioritarias (PROREST). Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conanp/acciones-y-programas/programa-para-la-proteccion-y-restauracion-de-ecosistemas-y-especies-prioritarias-prorest (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Brown, T.; Wyatt, J. Design Thinking for Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2009, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenderfer, H.L.; Thom, R.M.; Adkins, J.E. Systematic Approach to Coastal Ecosystem Restoration; NOAA Coastal Services Centre: Charleston, SC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Arce-Ibarra, M.; Armitage, D.; Charles, A.; Loucks, L.; Makino, M.; Satria, A.; Seixas, C.; Abraham, J.; Berdej, S. Analysis of Social-Ecological Systems for Community Conservation; Community Conservation Research Network: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, A. Sustainable Fishery Systems; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun, P. Beach Scraping—Is It Damaging to Beach Stability? Coast. Eng. 1983, 7, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonees, T.; Gijón Mancheño, A.; Scheres, B.; Bouma, T.J.; Silva, R.; Schlurmann, T.; Schüttrumpf, H. Hard Structures for Coastal Protection, Towards Greener Designs. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 1709–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrowitz, L.A. Social Perception; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-González, G.; Paredes-Chi, A.; Méndez-Funes, D.; Giraldo, M.; Torres-Irineo, E.; Arancibia, E.; Rioja-Nieto, R. Perceptions and Social Values Regarding the Ecosystem Services of Beaches and Coastal Dunes in Yucatán, Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Rosellón-Druker, J.; Calixto-Pérez, E.; Escobar-Briones, E.; González-Cano, J.; Masiá-Nebot, L.; Córdova-Tapia, F. A Review of a Decade of Local Projects, Studies and Initiatives of Atypical Influxes of Pelagic Sargassum on Mexican Caribbean Coasts. Phycology 2022, 2, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Bargh, J.A. Social Cognition and Social Perception. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1987, 38, 369–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzard, R.M.; Overbeck, J.R.; Maio, C.V. Community-Based Methods for Monitoring Coastal Erosion; Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E.; Torres-Conde, E.G.; Jordán-Dahlgren, E. Pelagic Sargassum Cleanup Cost in Mexico. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 237, 106542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garza, C.; Ceccon, E.; Méndez-Toribio, M. Ecological and Social Limitations for Mexican Dry Forest Restoration: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V.P.; Fixson, S.K. Adopting Design Thinking in Novice Multidisciplinary Teams: The Application and Limits of Design Methods and Reflexive Practices. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verganti, R.; Dell’Era, C.; Swan, K.S. Design Thinking: Critical Analysis and Future Evolution. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2021, 38, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D. Institutional Legitimacy and Co-Management of a Marine Protected Area: Implementation Lessons from the Case of Xcalak Reefs National Park, Mexico. Hum. Organ. 2009, 68, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce-Ibarra, A.M.; Seijo, J.C.; Headley, M.; Infante-Ramírez, K.; Villanueva-Poot, R. Rights-Based Coastal Ecosystem Use and Management. In Governing the Coastal Commons: Communities, Resilience and Transformation; Armitage, D., Charles, A., Berkes, F., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017; p. 271. ISBN 1138918431. [Google Scholar]

- Masselink, G.; Lazarus, E. Defining Coastal Resilience. Water 2019, 11, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Talib, C.; Aliyu, F.; Aabdul Malik, A.M.; Kang, H.S.; Chin, C.K.; Ismail, M.E.; Samsudin, M.A. Effect of Design-Thinking to Develop Marine and Coastal Environmental Attitudes. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2023, 18, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, J.; Arriaga, J.; Montoya, L.D.; Mariño-Tapia, I.J.; Escalante-Mancera, E.; Mendoza, E.T.; van Tussenbroek, B.I.; Appendini, C.M. Beaching and Natural Removal Dynamics of Pelagic Sargassum in a Fringing-Reef Lagoon. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2021, 126, e2021JC017636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.; Carter, R.W.; Thomsen, D.C.; Smith, T.F. Monitoring and Evaluation for Adaptive Coastal Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 89, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, M.; Gollan, N.; Barclay, K.; Gladstone, W. ‘It’s Part of Me’; Understanding the Values, Images and Principles of Coastal Users and Their Influence on the Social Acceptability of MPAs. Mar. Policy 2015, 52, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K. Viability of Community Participation in Coastal Conservation: A Critical Analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1095, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumuni, E.; Kaliannan, M.; O’Reilly, P. Approaches for Scientific Collaboration and Interactions in Complex Research Projects under Disciplinary Influence. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DCNA. Prevention and Clean-Up of Sargassum in the Dutch Caribbean; Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance: Bonaire, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Devault, D.A.; Pierre, R.; Marfaing, H.; Dolique, F.; Lopez, P.-J. Sargassum Contamination and Consequences for Downstream Uses: A Review. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 567–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pujol, L.; Orfila, A.; Álvarez-Ellacuría, A.; Terrados, J.; Tintoré, J. Posidonia Oceanica Beach-Cast Litter in Mediterranean Beaches: A Coastal Videomonitoring Study. J. Coast. Res. 2013, 165, 1768–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, G.; Simeone, S.; Baroli, M. Management of Beach-Cast Posidonia Oceanica Seagrass on the Island of Sardinia (Italy, Western Mediterranean). J. Coast. Res. 2008, 4, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, N.P.; Pasaribu, B.; Faizal, I.; Martasuganda, M.K.; Ilmi, M.H.; Febriani, C.; Alfarez, R.R. Coastal Clean-up in Southeast Asia: Lessons Learned, Challenges, and Future Strategies. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1250736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).