Abstract

Geosmin contamination in water is a worldwide concern, owing to its strong odor at trace levels and limited removal by typical water treatment methods. In this study, bentonite–alginate–magnetic (Bent-alg-mag) beads were prepared using the ionic gelation method for the removal of geosmin from aqueous solutions. The adsorbent’s physicochemical properties were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The influence of factors such as contact time, solution pH, initial geosmin concentration, and adsorbent dosage on adsorption performance was systematically investigated. Under optimal conditions, over 96% of geosmin was removed within 480 min. The adsorption kinetics were best described by the pseudo-first-order model (R2 = 0.9918), indicating that the process is primarily controlled by surface adsorption. Adsorption equilibrium data were well fitted by the Langmuir isotherm model (R2 = 0.9705) and a maximum monolayer capacity of 16.064 ng/g. The adsorbent exhibited 70% removal efficiency after three adsorption–desorption cycles, showing good regeneration potential, though long-term stability may be limited. Overall, the Bent-alg-mag beads proved to be an effective and promising material for the removal of geosmin from water.

1. Introduction

The occurrence of unpleasant taste and odor (T&O) in drinking water has emerged as a significant global concern [1]. Geosmin has been identified as one of the primary compounds responsible for taste and odor issues in drinking water [2]. It is a naturally occurring volatile compound produced as a secondary metabolite by a wide range of microorganisms, including cyanobacteria, actinomycetes and fungi [3,4,5]. Humans can perceive the earthy smell of geosmin, even at extremely low odor thresholds ranging from 6 to 10 ng/L [6]. Although geosmin does not pose a direct public health risk, its presence in drinking water can undermine public confidence in water quality and decrease consumption. Even when the water meets regulatory standards for chemical and microbial safety, noticeable taste and odor often cause consumers to consider it unfit for drinking. Several studies have demonstrated that traditional drinking water treatment methods, including coagulation, sedimentation, and filtration, are generally ineffective in eliminating geosmin [7,8]. To achieve effective removal of geosmin, water treatment facilities often employ advanced oxidation processes such as ozonation, hydrogen peroxide, and UV treatment [9,10,11,12,13]. These methods can effectively reduce geosmin; however, they are costly and may generate harmful by-products requiring additional treatment [14]. Biofiltration offers a sustainable alternative, though its performance is often constrained by long acclimation periods and dependence on microbial community composition [15]. Adsorption using activated carbon (AC) remains one of the most common and effective techniques for removing geosmin from water [8,16,17,18,19]. Despite its efficiency, AC has limited capacity and requires frequent replacement, increasing operational costs. These limitations underscore the need for alternative, cost-effective, and efficient removal strategies, which has led to increasing interest in adsorption-based methods as a practical solution for geosmin removal.

Adsorption has emerged as a preferred approach due to its low cost, ease of operation, high treatment efficiency, availability of diverse adsorbent materials, and broad applicability. Various adsorbents, including activated carbon [20,21,22], biochar [23], porous coordination polymers [24], zeolite [25], ceramic composites [26] and activated fly ash and bentonite hybrid composites [27], have been investigated for geosmin removal. Despite the wide range of materials studied, many conventional adsorbents face limitations such as finite adsorption capacity, difficult separation from water, and challenges in regeneration. These constraints highlight the need for the development of novel adsorbents that combine high efficiency and ease of recovery, paving the way for more sustainable and cost-effective geosmin removal strategies.

Bentonite is a naturally occurring clay mineral composed primarily of montmorillonite. Its structure, consisting of two Si–O tetrahedral sheets sandwiching an Al–O octahedral layer, provides a large surface area, cation exchange and notable swelling ability, which favor adsorption processes [28]. Due to its abundant availability, low cost, and excellent adsorption capacity, bentonite has emerged as a promising adsorbent for water treatment applications [29]. Despite its high adsorption capacity, recovering suspended bentonite from aqueous solutions after contaminant removal is often difficult. This challenge can be addressed by integrating bentonite with alginate to form composite beads, which enhance structural stability and allow easy solid–liquid separation.

Alginate is a natural anionic polysaccharide extracted from brown seaweed [30]. Due to its natural abundance, low cost, nontoxicity, biodegradability, hydrophobic nature, pH sensitivity, and abundance of functional groups, alginate has been extensively applied in diverse fields such as medical, environmental remediation, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and food processing [31]. Alginate forms a three-dimensional “egg-box” structure through ionic crosslinking between its guluronic acid (G) blocks and divalent cations, most commonly calcium ions (Ca2+) [32]. The carboxylate groups of adjacent G-blocks bind to the cations, creating bridges that link polymer chains and generate a stable gel network [32]. This unique configuration imparts mechanical strength and structural stability, making calcium alginate beads suitable for applications such as adsorbent supports. Embedding magnetite nanoparticles within the alginate–bentonite framework further enables magnetic separation, facilitating rapid adsorbent retrieval and improving reusability.

Magnetically separable adsorbents have emerged as promising materials for efficient solid–liquid separation in water treatment. Conventional adsorbents are often difficult to recover, requiring complex filtration or centrifugation processes that cause adsorbent loss and reduced efficiency. In contrast, magnetic separation enables rapid and environmentally friendly recovery under an external magnetic field without additional chemicals. Magnetite (Fe3O4) and related ferrites (γ-Fe2O3, MnFe2O4) are widely used in such composites for their strong magnetism, stability, and surface reactivity [33,34,35]. To improve adsorption capacity and structural integrity, these nanoparticles are commonly integrated with natural polymers or inorganic materials. In this context, the integration of bentonite, a layered aluminosilicate with high surface area, and alginate, a biopolymer capable of forming cross-linked hydrogel networks, provides an ideal matrix for dispersing Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The resulting alginate–bentonite–magnetic composite not only offers abundant active sites and strong adsorption affinity for geosmin but also allows facile magnetic recovery, reusability, and environmental compatibility, addressing key challenges in sustainable water purification.

In this work, we present the synthesis of alginate–bentonite–magnetic beads as a novel adsorbent system for the efficient removal of geosmin from water. The prepared beads were characterized using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm their structural and functional properties. Batch experiments were conducted to evaluate the influence of operational parameters such as contact time, adsorbent dosage, initial geosmin concentration, and pH on adsorption performance. In addition, adsorption kinetics, equilibrium isotherms, and reusability studies were conducted to elucidate the adsorption behavior and assess the potential of Bent-alg-mag as an efficient and reusable adsorbent for geosmin removal.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Sodium alginate, bentonite, calcium chloride, ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4.7H2O), aqueous ammonia (NH4OH), hydrochloric acid, and sodium hydroxide were obtained from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan. Analytical grade chemicals were used as received, and all solutions were prepared with deionized water. During the synthesis, nitrogen (N2) gas was continuously bubbled through the reaction medium to maintain an inert atmosphere.

2.2. Synthesis of Magnetite Nanoparticles

Magnetite nanoparticles were synthesized via hydrothermally assisted co-precipitation under an inert nitrogen atmosphere, using a modified protocol based on the method of Chen et al. [36]. FeSO4.7H2O (5.004 g) was dissolved in deionized water with continuous nitrogen bubbling, followed by dropwise addition of 20 mL of aqueous ammonia (2.5%) and slow introduction of 0.54 mL of H2O2 under stirring. The homogenous mixture was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 160 °C for 12 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, the black precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed thoroughly with deionized water, and dried at 35 °C to yield uniform magnetite nanoparticles.

2.3. Preparation of Bent-alg-mag Beads

Bent-alg-mag composite beads were fabricated via ionic gelation method [37]. Approximately 3 g of sodium alginate was dissolved in 200 mL of deionized water at 60 °C and stirred vigorously for 1 h to obtain a homogenous solution. In a separate preparation, 1.2 g of bentonite powder and 1 g of Fe3O4 were dispersed in 100 mL of deionized water under continuous stirring. The mixture was slowly introduced into the alginate solution while stirring and subsequently homogenized using a Astrason XL ultrasonic processor (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY, USA). The resulting bentonite–alginate–Fe3O4 mixture was then added dropwise into a 0.5 M calcium chloride solution via a peristaltic pump (EYELA MP-1000, Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to form composite beads through ionic gelation. The beads were allowed to remain in the calcium chloride solution for 24 h to ensure complete crosslinking, followed by washing with deionized water to remove residual CaCl2. The prepared Bent-alg-mag beads were stored in deionized water for subsequent characterization and adsorption experiments.

2.4. Characterization of Adsorbent

The surface morphologies of the prepared Bent-alg-mag beads and magnetite nanoparticles were examined using SEM (SU1510, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The FTIR analysis was performed using a Tensor II FT-IR spectrometer (Burker Optics, Tokyo, Japan) over the range of 400–4000 cm−1. The XRD analysis was performed using an XRD diffractometer (Ultima III, Rigaku corporation, Tokyo, Japan) operating at 40 kV and 40 mA with Cu Kα radiation. Radial scans were recorded in the regions of 2θ from 10 to 100°. The point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the composite beads was determined by the pH drift method. A set of 50 mL solutions of 0.01 M NaCl was prepared and adjusted to pH values ranging from 1 to 12 using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH. Each solution was treated with 2.0 g of the composite beads and shaken for 24 h. The equilibrium pH was measured, and the pHpzc was determined from the point where the pHfinal-pHinitial plot intersects the line pHfinal = pHinitial [38].

2.5. Adsorption Experiments

Adsorption experiments were systematically performed to investigate the effects of contact time, adsorbent dosage, initial geosmin concentration, and solution pH on the adsorption performance of the beads. The effect of contact time was evaluated over a range of 0–480 min. The influence of adsorbent dosage was examined by varying the bead mass from 0.1 to 4.0 g, while the role of initial geosmin concentration was evaluated using geosmin solutions prepared in the range of 250–1250 ng/L. The effect of solution pH on geosmin adsorption was investigated by adjusting the pH between 1 and 11 using 0.1 M HCl or NaOH. Each experiment was conducted by varying one parameter at a time while keeping all other conditions constant. All adsorption experiments were performed at room temperature under constant agitation at 100 rpm. At the end of each experiment, the magnetic beads were separated from the solution using an external magnet, and 2 mL of the supernatant was collected to determine the residual geosmin concentration. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results shown in the graphs represent the mean values.

2.6. Kinetic and Isotherm Studies

Adsorption kinetics were investigated to elucidate the geosmin uptake mechanism by the beads. For the kinetic study, 2.0 g of adsorbent was contacted with 50 mL of geosmin solution (500 ng/L) at pH 9. The suspensions were agitated at 100 rpm and aliquots were collected at predetermined time intervals ranging from 0 to 480 min. The experimental data were analyzed using pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models.

Adsorption isotherm experiments were conducted to evaluate the equilibrium behavior of geosmin adsorption. Geosmin solutions with initial concentrations ranging from 250 to 1250 ng/L were equilibrated with 2.0 g of beads for 480 min under constant conditions of pH 9, room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) and 100 rpm. The equilibrium data obtained were fitted to the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models to determine the adsorption capacity and adsorption characteristics of the beads. The adsorption capacity at time t (qt, ng/g) and the removal efficiency (R%) were calculated by the following Equations (1) and (2).

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium geosmin concentrations (ng/L), respectively. Ct (ng/L) is the concentration of adsorbate at time t, V is the solution volume (L), and m is the adsorbent mass (g).

2.7. Regeneration Experiments

The potential of the adsorbent for repeated use was assessed through regeneration experiments. In each trial, 2.0 g of the composite beads was contacted with 50 mL of geosmin solution (500 ng/L, pH 9) and agitated at 25 °C under 100 rpm for 6 h. Following adsorption, the spent beads were retrieved and subjected to desorption using 0.5 M NaCl prepared in 30% (v/v) ethanol. This treatment was carried out at 25 °C with continuous stirring (100 rpm) for 30 min. The regenerated beads were subsequently rinsed thoroughly with deionized water and applied again to fresh adsorption experiments under the same conditions. The adsorption–desorption sequence was performed for four consecutive cycles to evaluate reusability.

2.8. Geosmin Determination

Geosmin determination was performed by headspace gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-GC/MS) employing a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 system (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a Restek Rtx-5ms capillary column (Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Volatile extraction from the sample headspace was achieved using solid-phase microextraction (SPME) with a Supelco fiber (572933-U, Sigma Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan). During extraction, sample vials were maintained at 70 °C and agitated at 700 rpm for 30 min to facilitate equilibrium of geosmin between the liquid and gas phases. Following extraction, the SPME fiber was inserted into the GC injection port and thermally desorbed at 230 °C for 3 min under spitless conditions. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 5 mL/min. The GC oven program consisted of an initial hold at 40 °C for 3 min, a temperature ramp at 15 °C/min to 250 °C, and a final hold for 5 min, giving a total analysis time of approximately 20 min. The transfer line was maintained at 250 °C. Detection was conducted by monitoring the characteristic ion (m/z 112) specific to geosmin [37,39]. Quantification was based on calibration curves prepared from geosmin standard solutions (CRM47522, Sigma Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan) covering concentrations of 5–1250 ng L−1. For each level, 50 mL of standard solution was prepared, and 2 mL aliquots were analyzed in triplicate to ensure precision and reproducibility.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Magnetic Adsorbent

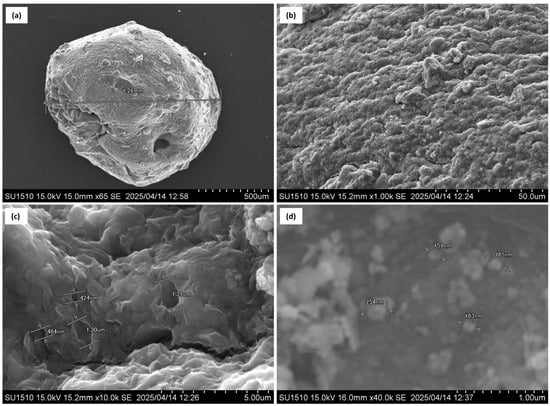

3.1.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

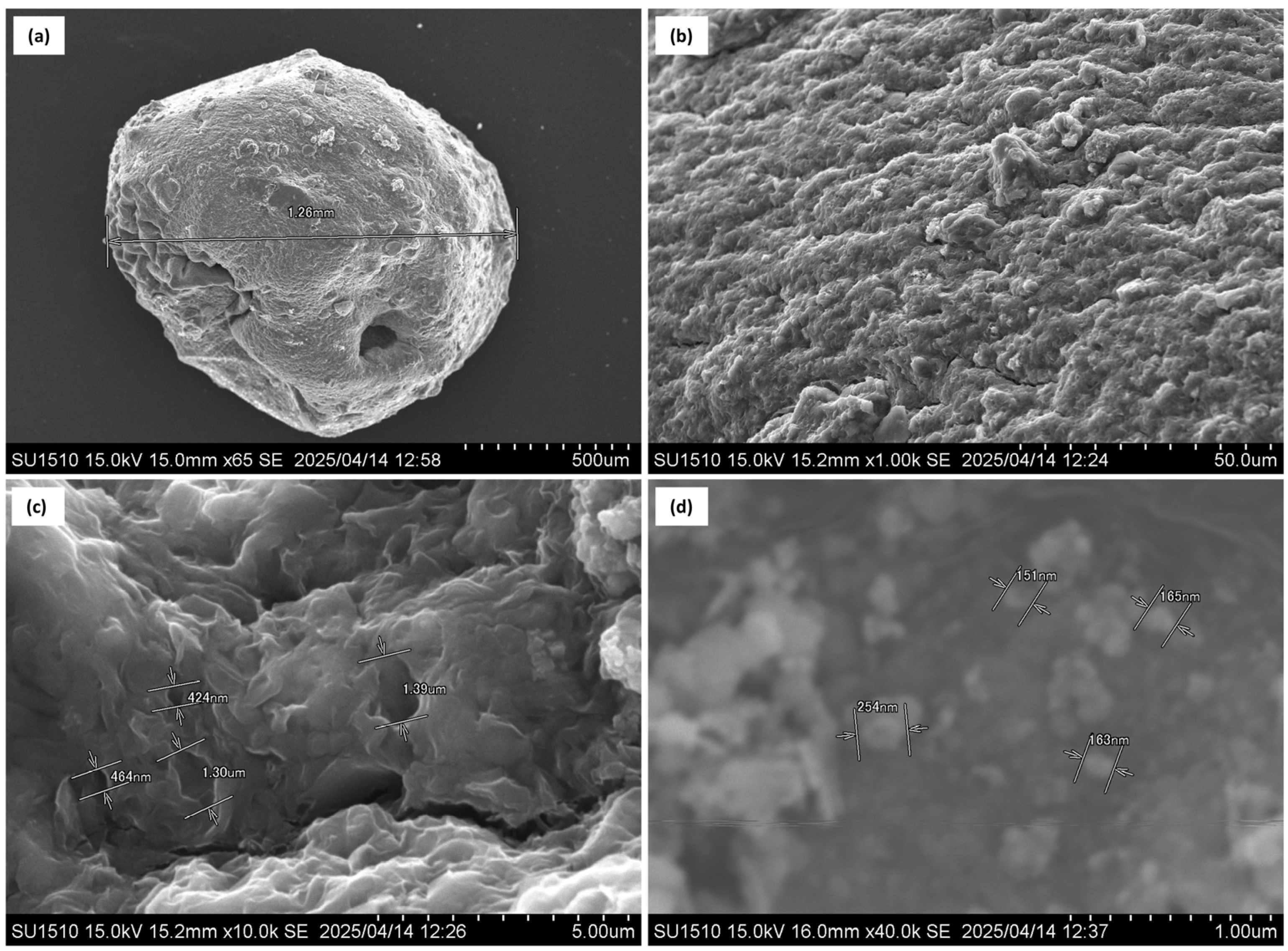

The surface morphology of the Bent-alg-mag composite beads and pure Fe3O4 nanoparticles were analyzed using SEM, as shown in Figure 1. The low-magnification image (Figure 1a) shows that the composite beads exhibit a nearly spherical morphology with an average diameter of approximately 1.26 mm. The surface of the bead (Figure 1b) appears rough and irregular, which may contribute to improved adsorption by increasing the surface area and providing more accessible active sites. At higher magnification (Figure 1c), the surface structure of the Bent-alg-mag composite reveals a highly irregular and rough surface morphology, indicating the presence of a well-developed porous network. The structure exhibited pore sizes ranging approximately from 400 nm to 1.4 µm. These pores may contribute to a large specific surface area. The SEM image of pure Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Figure 1d) shows nearly spherical particles with sizes ranging from 151 to 254 nm, confirming the formation of nanosized magnetite. The observed morphology indicates that the composite beads possess a porous and heterogenous surface suitable for adsorption applications.

Figure 1.

SEM images of Bent-alg-mag composite bead (a), composite surface (b), porous structure of the composite (c), Fe3O4 nanoparticles (d).

3.1.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

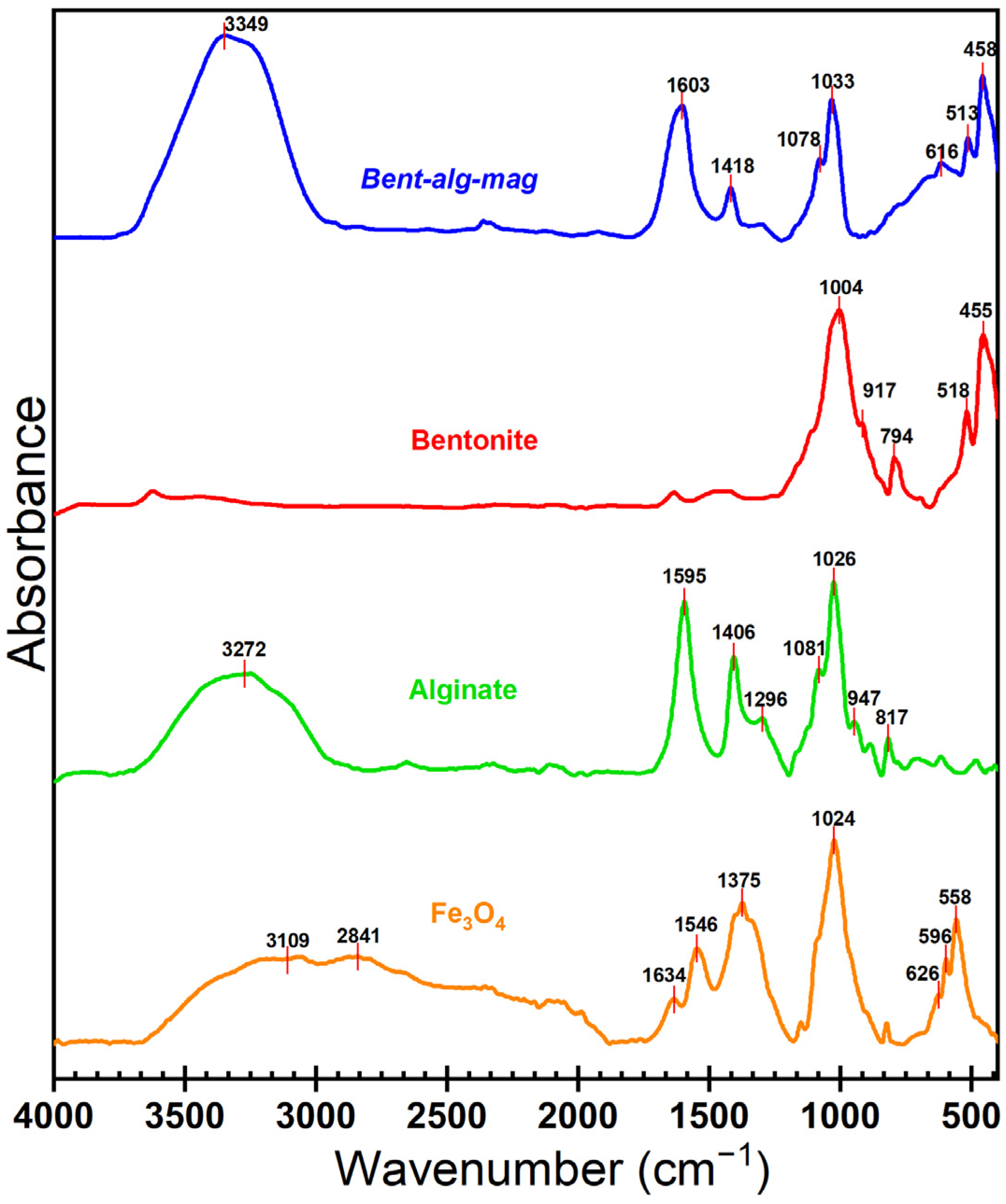

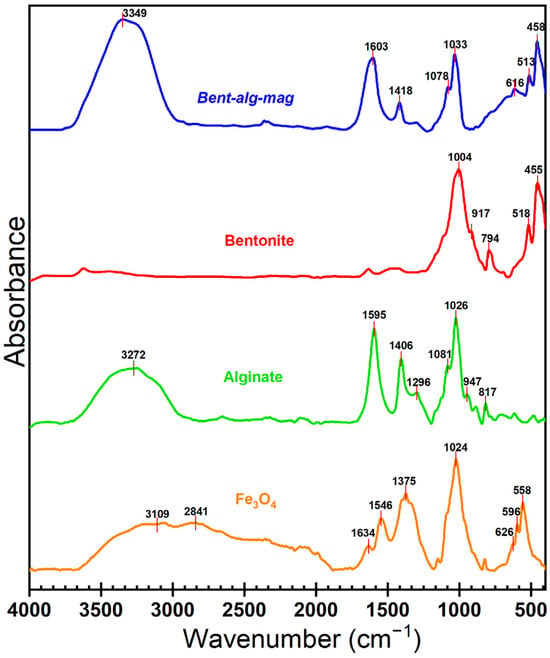

The FTIR spectra of alginate, bentonite, magnetite (Fe3O4), and the Bent-alg-mag composite were analyzed in the range of 400 and 4000 cm−1 (Figure 2). Bentonite exhibited multiple absorption peaks at 1004, 917, 794, 518, and 455 cm−1. The band at 1004 cm−1 corresponds to Si–O stretching of the tetrahedral silicate framework [40], while the peak at 917 cm−1 arises from Al–Al–OH bending vibrations in the octahedral sheet of montmorillonite [40]. The peaks at 794, 518 and 455 cm−1 are attributed to Si–O–Al symmetric stretching and Si–O–Si bending modes, which are characteristic of layered aluminosilicate structure of bentonite [41].

Figure 2.

FTIR spectrum of components and Bent-alg-mag composite.

For alginate, the absorption bands at 3272 cm−1 correspond to O–H stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups [42], while the peaks at 1595 cm−1 and 1406 cm−1 are attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate (–COO–) groups, respectively [43]. The bands at 1296, 1081, 1026, 947, and 817 cm−1 are assigned to C–O–C stretching and C–O vibrations within the polysaccharide backbone, confirming the presence of alginate’s characteristic functional groups [44].

The FTIR spectrum of magnetite (Fe3O4) displayed characteristic adsorption peaks at 626, 596, and 558 cm−1, corresponding to the Fe–O stretching vibrations in the tetrahedral and octahedral sites of the spinel structure, confirming the successful synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles [44,45]. Additional weak bands at 3109, 2841, 1634, 1546, 1375, and 1024 cm−1 may be attributed to adsorbed moisture, surface hydroxyl groups, or trace organic residues from the synthesis medium [45].

The Bent-alg-mag composite spectrum exhibited combined characteristic bands of all components, confirming successful integration. The broad band at 3349 cm−1 was assigned to O–H stretching vibrations from alginate, bentonite, and absorbed water molecules [42]. The peaks at 1603 and 1418 cm−1 corresponded to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching of carboxylate (–COO–) groups of alginate [43], indicating interactions between alginate and Fe ions on the magnetite surface. The bands at 1078 and 1033 cm−1 were associated with C–O–C and Si–O–Si stretching, respectively [29,44], confirming the coexistence of organic and inorganic components. The low-frequency bands at 615, 513, and 458 cm−1 corresponded to Fe–O vibrations of magnetite and Si–O–Al/Si–O–Si bending of bentonite [41,46]. The observed shifts and overlapping of characteristic peaks indicate strong intermolecular interactions among alginate, bentonite, and magnetite, confirming the successful formation of the Bent-alg-mag composite.

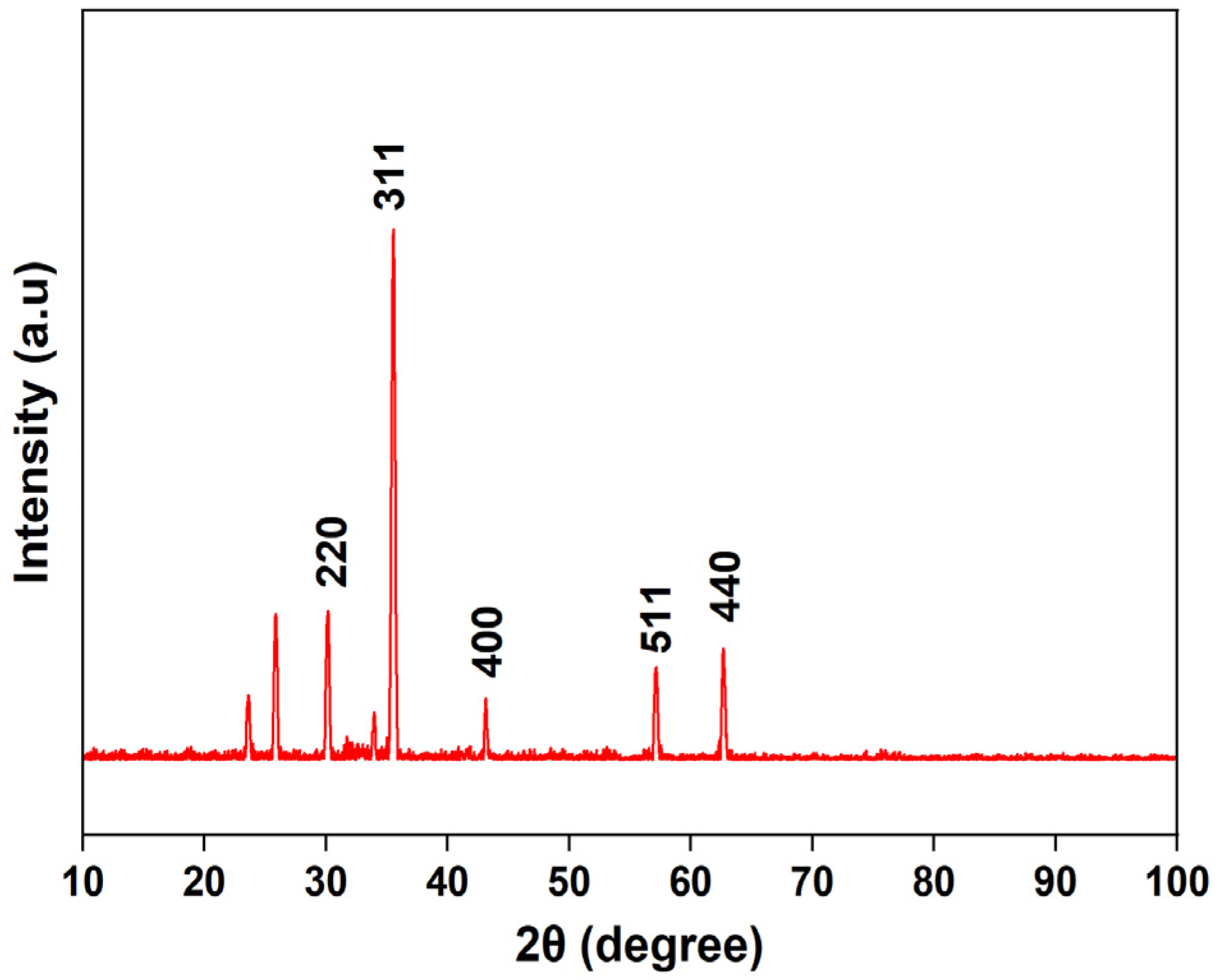

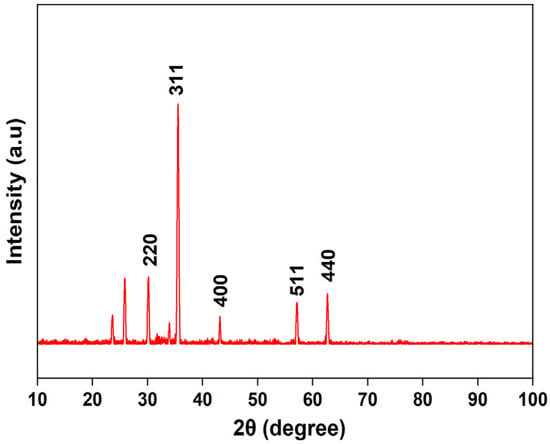

3.1.3. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

The XRD pattern of the synthesized magnetic nanoparticles (Figure 3) exhibits characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 30.18, 35.55, 43.14, 57.16, and 62.67, corresponding to the (220), (311), (400), (511), and (440) planes, respectively. These reflections are consistent with the cubic spinel structure of magnetite (Fe3O4), showing good agreement with the standard data (JCPDS PDF No. 01-071-6336). The presence of these characteristic peaks confirms the formation of pure crystalline Fe3O4 nanoparticles, as similarly observed in previous studies on magnetite synthesis [47,48]. Additional weak peaks observed at lower angles may be attributed to residual precursor species or minor impurities.

Figure 3.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles.

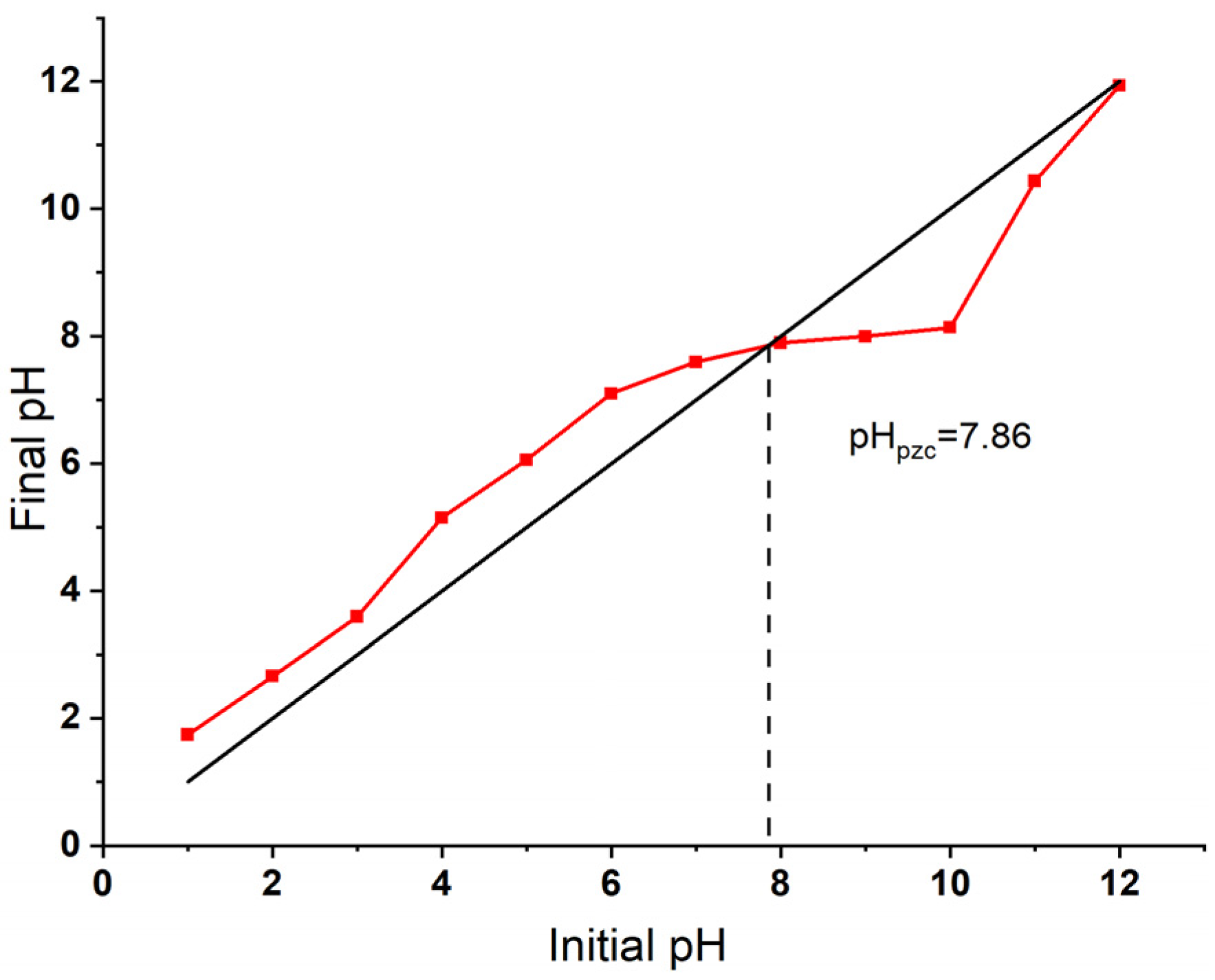

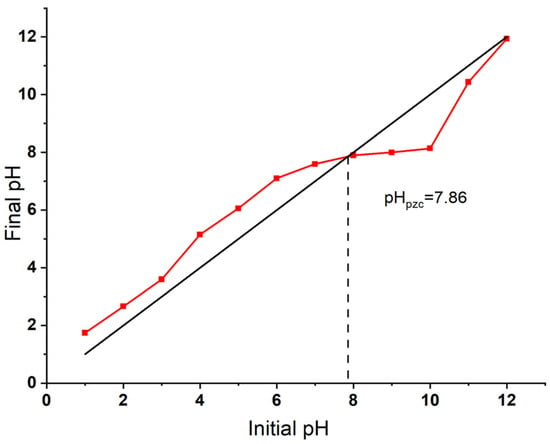

3.1.4. Point of Zero Charge (pHpzc)

The point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the Bent-alg-mag beads was determined using the pH drift method and found to be 7.86 (Figure 4). This value indicates that the surface pH of the adsorbent is positively charged at solution pH below 7.86 and negatively charged at pH above this point. The pHpzc plays a crucial role in controlling the surface charge characteristics and, consequently, the adsorption behavior of the composite. This result aligns well with a previous study on activated bentonite/alginate composites, which reported a slightly lower pHpzc of 7.04, further supporting the influence of surface charge on adsorption efficiency [49].

Figure 4.

Point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the Bent-alg-mag composite, determined by the pH drift method.

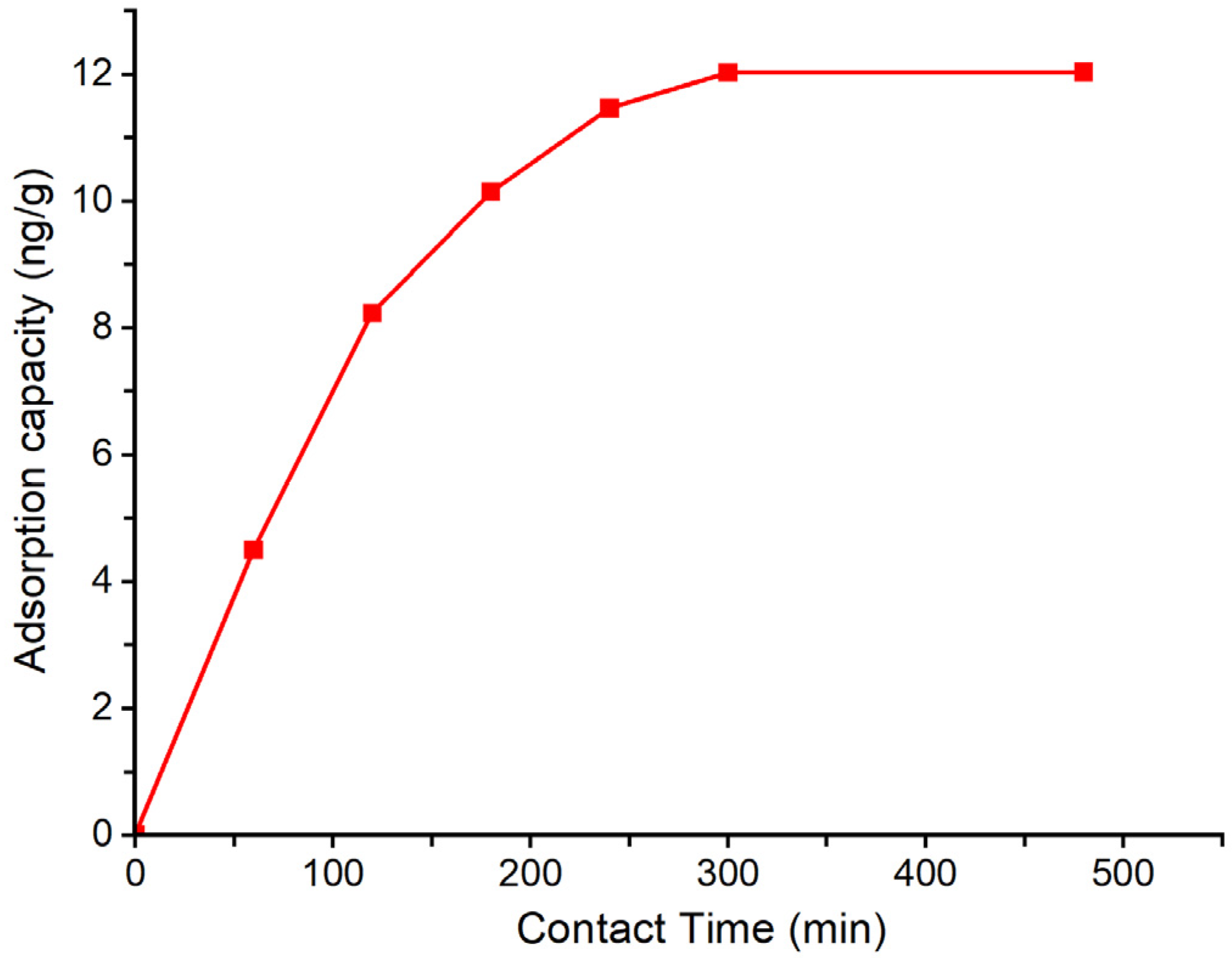

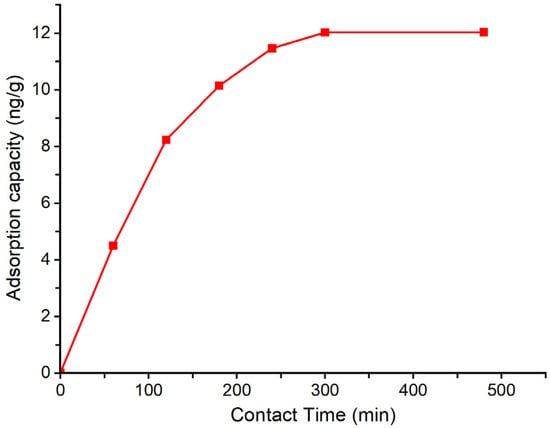

3.2. Effect of Contact Time

The influence of contact time on the removal efficiency of geosmin by the Bent-alg-mag was investigated by varying the adsorption duration from 0 to 480 min (Figure 5). A fixed adsorbent dose of 2.0 g was added to 50 mL of 500 ng/L geosmin solution at pH 9 and agitated at 100 rpm. The results indicated that the adsorption capacity increased rapidly during the initial phase, reaching a plateau as equilibrium approached, suggesting that the majority of active sites were occupied within the first few hours. This behavior highlights the importance of optimizing contact time to achieve maximum removal efficiency without unnecessary prolongation of the process.

Figure 5.

Effect of contact time on the adsorption capacity of Bent-alg-mag composite.

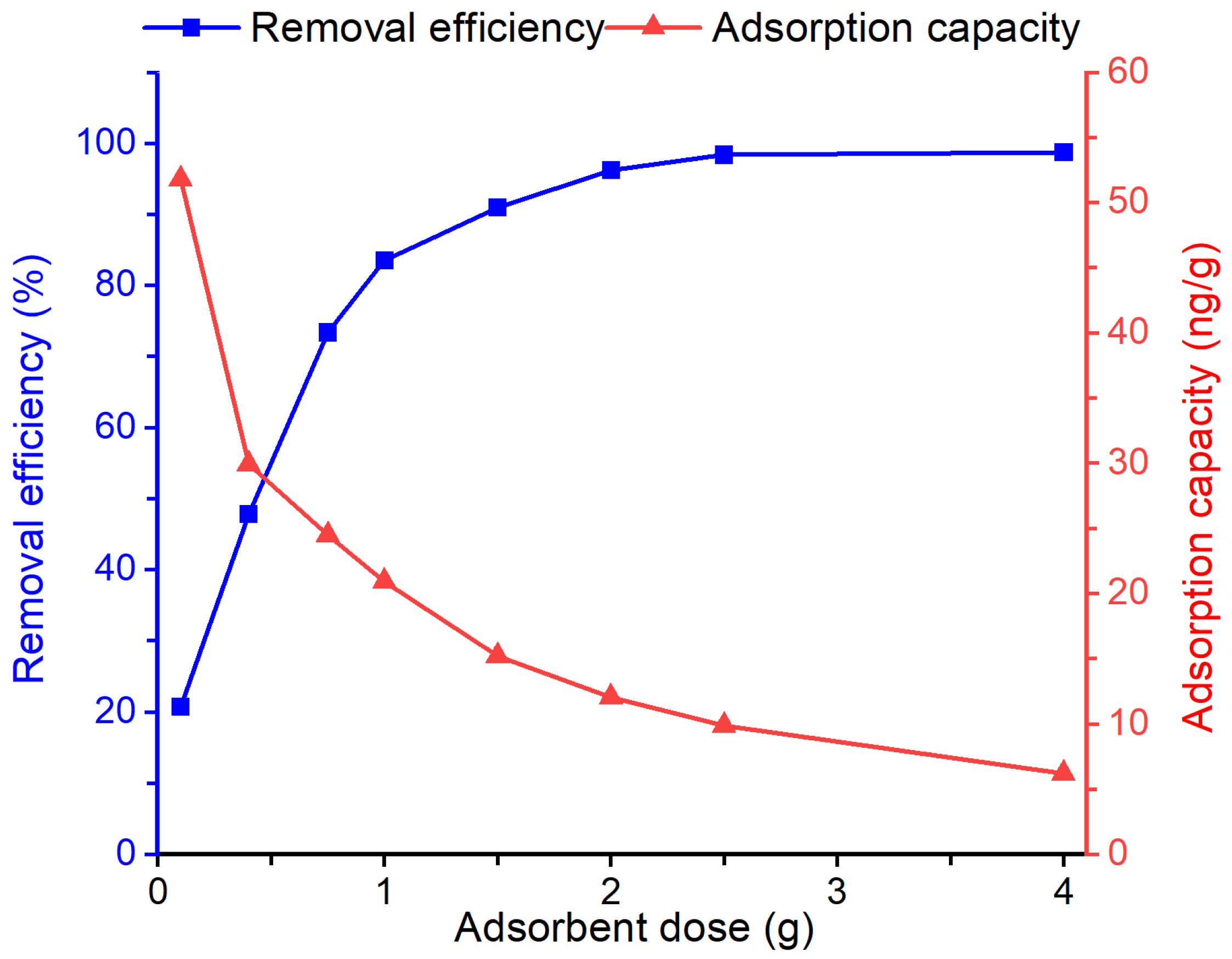

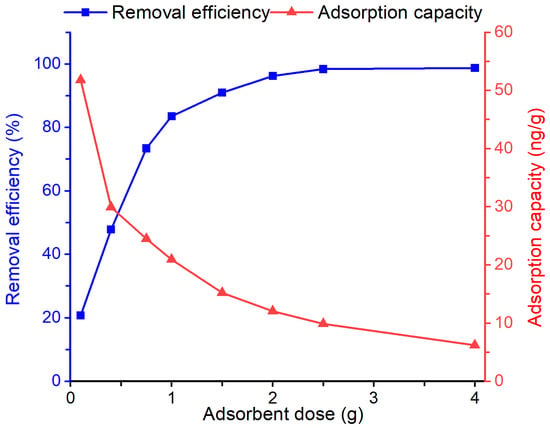

3.3. Effect of Dosage

The effect of adsorbent dosage on the removal efficiency and adsorption capacity of the Bent-alg-mag toward geosmin was examined by varying the dose from 0.25 to 4.0 g in 50 mL of 500 ng/L geosmin solution at pH 9 and agitated at 100 rpm for 480 min (Figure 6). Increasing the adsorbent dosage resulted in a substantial enhancement in removal efficiency, attaining almost complete geosmin elimination at higher doses. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the increased availability of active adsorption sites and larger surface area, which enhances the interaction between geosmin molecules and the composite surface. In contrast, the adsorption capacity (ng/g) decreased with increasing adsorbent mass, likely due to the unsaturation of active sites at higher dosage under constant initial geosmin concentration. These findings reflect common adsorption characteristics, where higher adsorbent dosages yield greater overall removal but lower capacity per unit mass. An adsorbent dosage of 2.0 g was selected as the optimal dosage for subsequent experiments, as it achieved near complete geosmin removal (>95%) while ensuring efficient adsorbent utilization.

Figure 6.

Effect of adsorbent dose on the removal efficiency and adsorption capacity of the Bent-alg-mag composite.

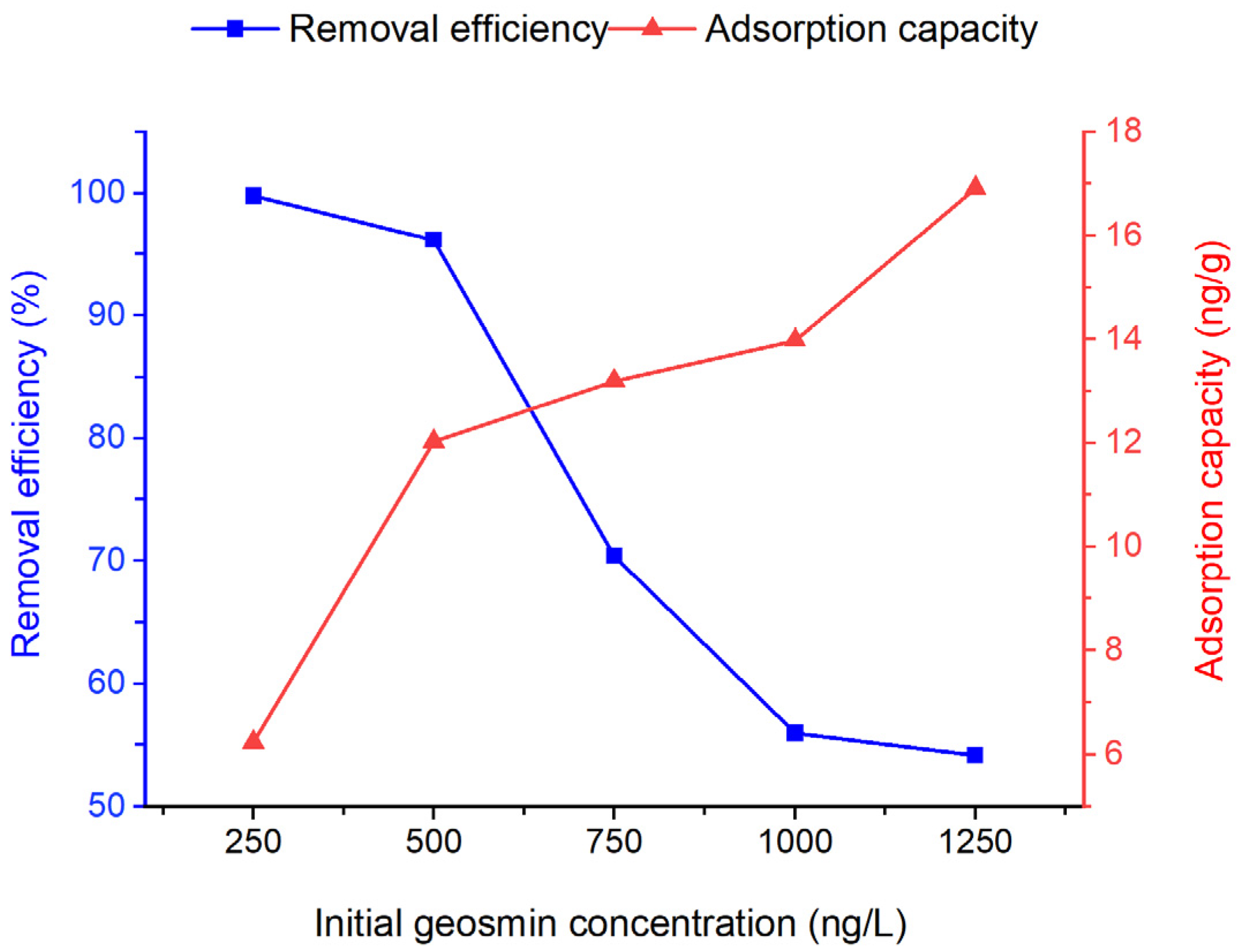

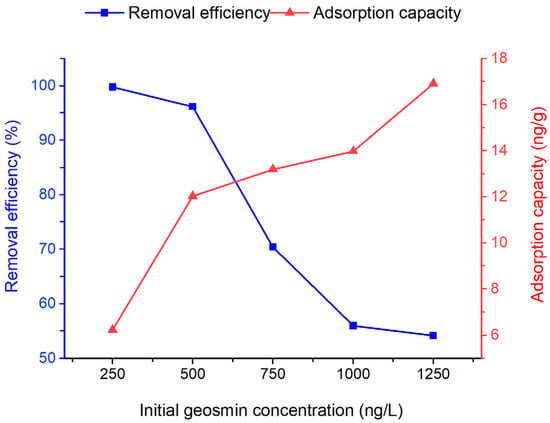

3.4. Effect of Initial Concentration of Geosmin

The effect of initial geosmin concentration on the adsorption by Bent-alg-mag beads was evaluated using concentrations ranging from 250 to 1250 ng/L, with a constant adsorbent dose of 2.0 g for 480 min at 100 rpm under pH 9 (Figure 7). The geosmin concentration range of 250–1250 ng/L was selected based on its consistency with concentration ranges reported in previous studies examining geosmin removal using various adsorbents [17,26,50,51,52]. The results showed that removal efficiency decreased from 99.79% at 250 ng/L to 54.16% at 1250 ng/L. At low geosmin concentrations, efficient adsorption occurs due to plentiful active sites; however, as concentration rises, site saturation restricts further uptake and reduces removal efficiency. Nonetheless, the increase in adsorption capacity at higher initial concentrations is due to the greater abundance of geosmin molecules, which provides a stronger mass-transfer driving force toward the adsorbent surface.

Figure 7.

Effect of initial geosmin concentration on removal efficiency of the Bent-alg-mag composite.

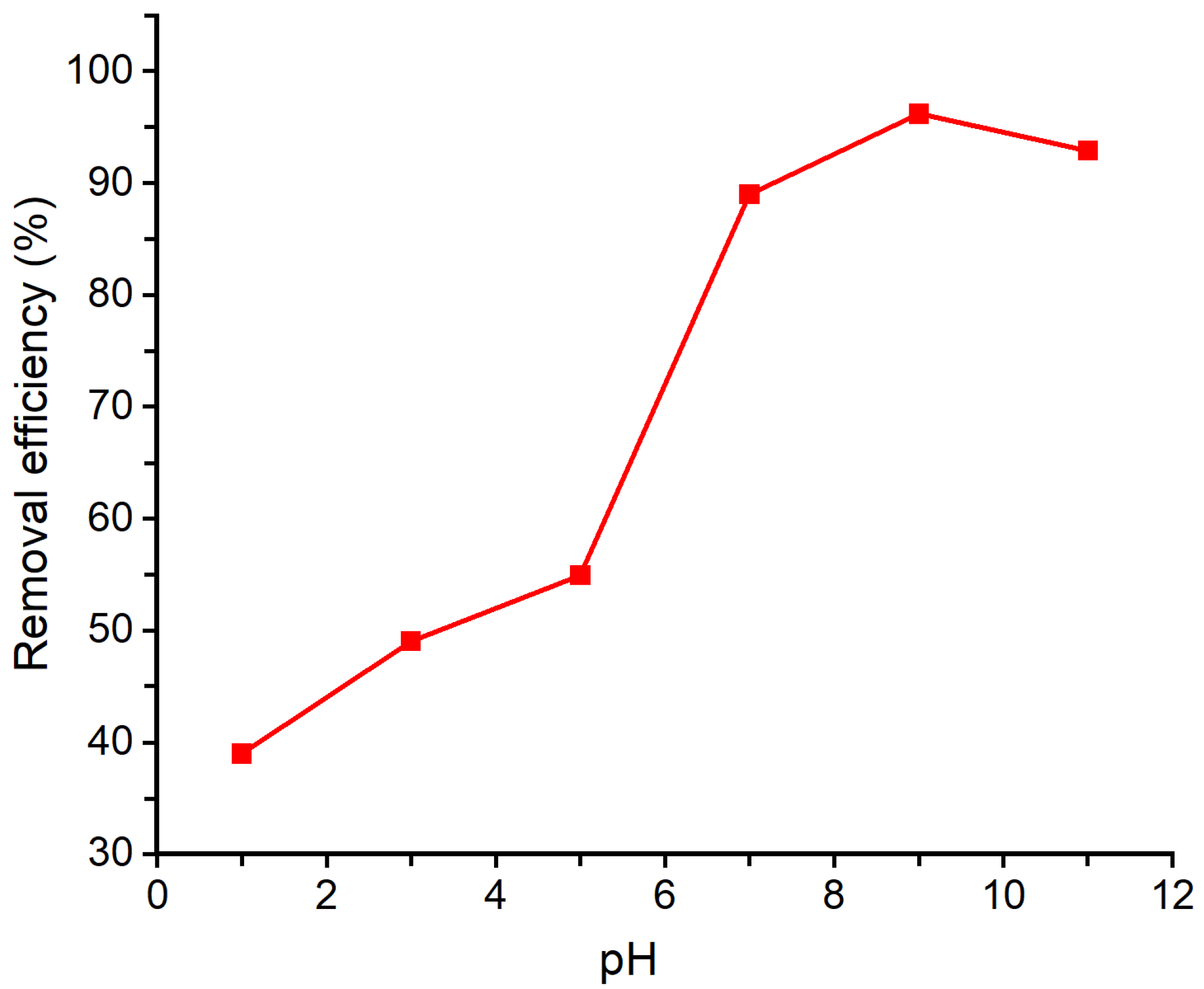

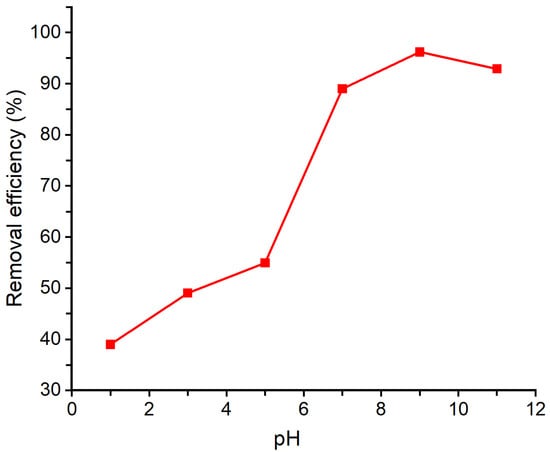

3.5. Effect of Initial pH

The effect of pH on the adsorption of geosmin onto Bent-alg-mag beads was evaluated within the pH range of 1–11 (Figure 8). In each experiment, 2.0 g of the adsorbent was introduced into 50 mL of a 500 ng/L geosmin solutions, and the pH was adjusted to 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11. The suspensions were then agitated at 100 rpm for 480 min. The highest geosmin removal was observed at pH 9, corresponding to a removal efficiency of 96.18%. The results showed that the geosmin removal efficiency increased from around 39% at pH 1 to 96.18% at pH 9, followed by a slight decrease to about 93% at pH 11. This trend is closely related to the surface charge characteristics of the composite, which has a pHpzc of 7.86. When the solution pH is below the pHpzc, the surface of the adsorbent is positively charged, resulting in reduced interaction with geosmin molecules due to electrostatic repulsion and surface protonation. As the pH increases beyond the pHpzc, the adsorbent surface becomes negatively charged, favoring stronger interactions through hydrophobic attractions and van der Waals forces. The increased negative surface charge also enhances the dispersion of magnetic particles and the accessibility of active sites, improving adsorption efficiency up to pH 9. Since the pHpzc of the Bent-alg-mag beads is 7.86, the surface remains negatively charged at pH > 7.86, and at pH above 9, further deprotonation may slightly reduce the accessibility of hydrophobic regions, leading to a minor decline in geosmin adsorption efficiency between pH 9 and 11.

Figure 8.

Effect of pH on removal efficiency of the Bent-alg-mag composite.

The behavior of geosmin across the pH range further supports this trend. Geosmin, being a neutral and hydrophobic molecule, remains largely uncharged across the studied pH range. Thus, its adsorption is primarily governed by hydrophobic interactions. Under alkaline conditions, where the adsorbent surface is negatively charged and less protonated, the environment becomes more favorable for hydrophobic adsorption due to reduced competition from protons and enhanced surface availability. Conversely, under acidic conditions, the protonated adsorbent surface reduces available hydrophobic regions and active sites, leading to lower adsorption. Therefore, the combined influence of the adsorbent’s surface charge (pHpzc = 7.86) and geosmin’s neutral character explains the enhanced removal observed near pH 9. Although geosmin adsorption is predominantly driven by hydrophobic interactions, weak hydrogen bonding between the –OH group of geosmin and oxygen-containing surface functional groups of the Bent-alg-mag composite may also contribute to the overall interaction. Such interactions are expected to be minor due to geosmin’s tertiary alcohol structure but could provide additional stabilization at pH values near and above the pHpzc.

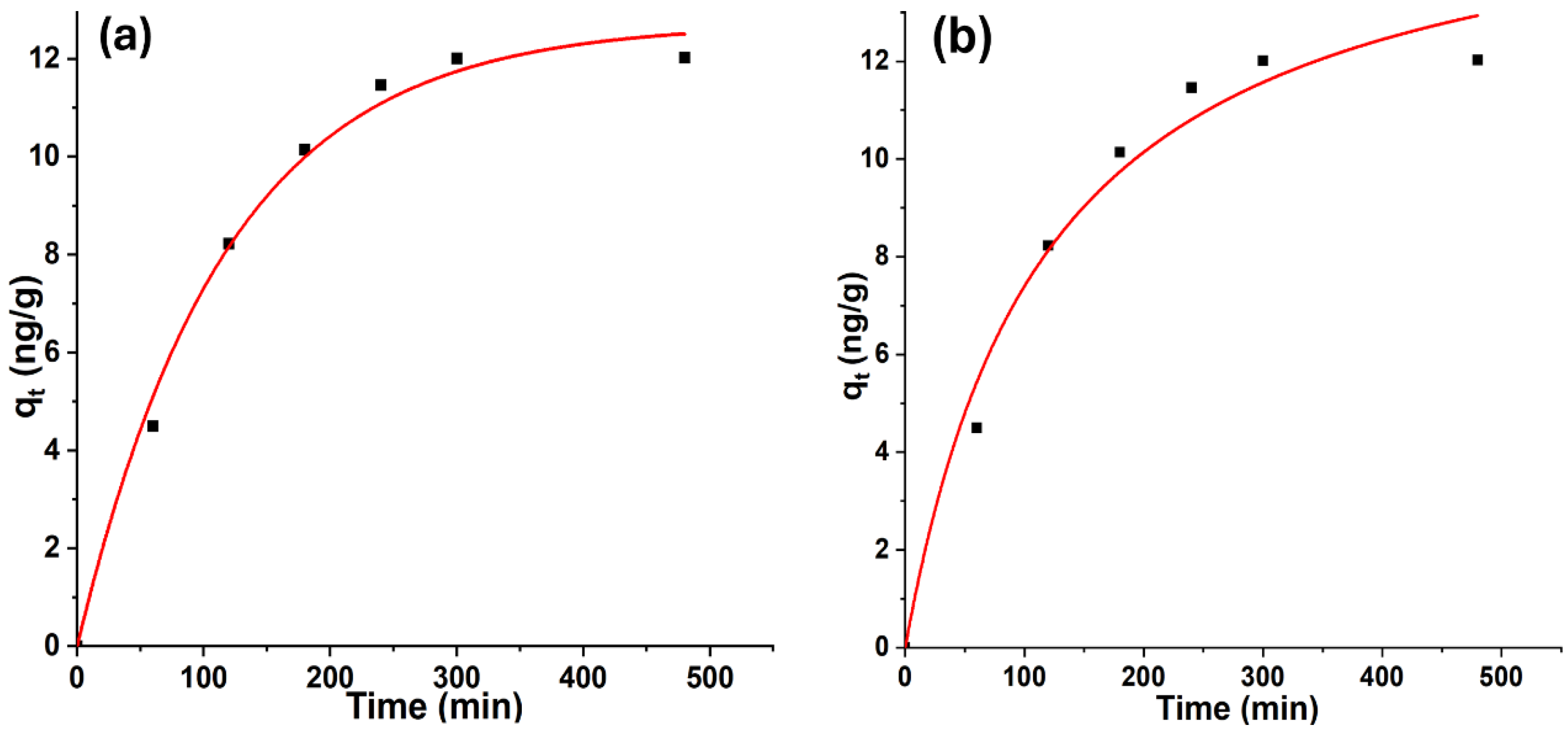

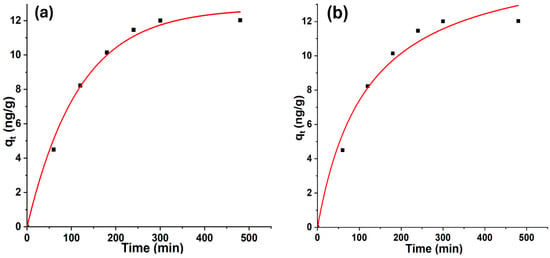

3.6. Adsorption Kinetic Study

The kinetic behavior of geosmin adsorption onto Bent-alg-mag beads was examined using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models. The nonlinear fitting curves for both models are presented in Figure 9, and the corresponding kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. The PFO model provided a better fit, as indicated by a higher correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.9918) compared to that of the PSO model (R2 = 0.9757). The equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) predicted by the PFO model (12.72 ng/g) was also closer to the experimentally observed value (12.02 ng/g), confirming its suitability for describing the geosmin adsorption behavior. The higher rate constant (K1 = 8.56 × 10−3) suggests a relatively rapid initial adsorption phase, which may be attributed to the abundance of available active sites on the composite surface. These findings indicate that geosmin adsorption onto the Bent-alg-mag beads is primarily governed by a physical adsorption mechanism, consistent with the PFO model assumption of diffusion-controlled uptake. The relatively lower R2 value and smaller rate constant obtained for the PSO model suggest that chemisorption plays a lesser role in this system. Therefore, the adsorption process can be described as predominantly physisorptive, involving interactions such as van der Waals forces and hydrophobic attraction between geosmin molecules and the composite surface.

Figure 9.

Nonlinear kinetic adsorption models: (a) pseudo-first-order kinetic model, (b) pseudo-second-order kinetic model.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for geosmin adsorption onto Bent-alg-mag beads based on pseudo-first- order and pseudo-second-order.

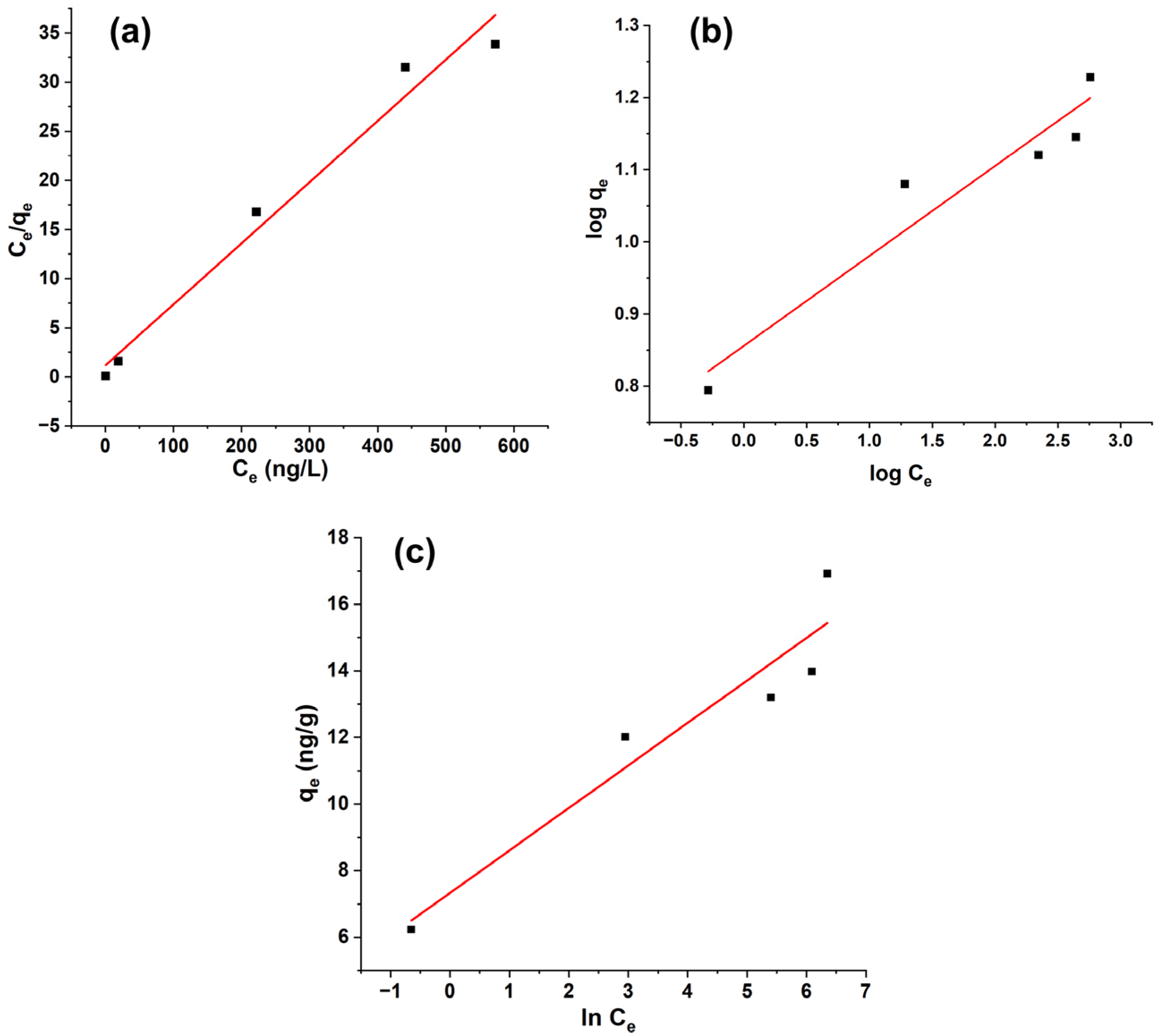

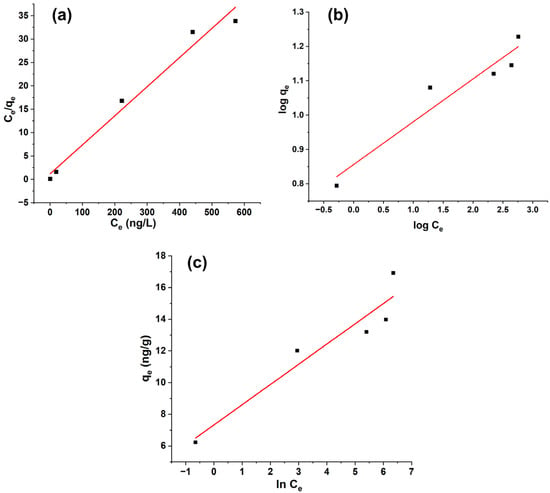

3.7. Adsorption Isotherm Study

The equilibrium data for geosmin adsorption onto Bent-alg-mag beads were analyzed using the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models (Figure 10, Table 2). Among the three models, the Langmuir model provided the best representation of the experimental data, as indicated by the highest correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.9705), compared with lower correlation values for the Freundlich (R2 = 0.902) and Temkin (R2 = 0.8824) models. The maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (qmax) obtained from the Langmuir model was 16.064 ng/g, suggesting the formation of a uniform monolayer of geosmin molecules on the composite surface. The separation factor (RL < 1) further confirmed that the adsorption process was favorable under the studied conditions.

Figure 10.

Linear isotherm models: (a) Langmuir isotherm model, (b) Freundlich isotherm model, and (c) Temkin isotherm model.

Table 2.

Isotherm parameters for geosmin adsorption onto Bent-alg-mag beads based on Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin isotherm models.

In contrast, the relatively poorer performance of the Freundlich and Temkin models provides additional insight that reinforces the Langmuir-based mechanism. The lower correlation coefficients (R2 = 0.902 and 0.8824, respectively) imply that surface heterogeneity, multilayer adsorption, or progressive changes in adsorption energy assumptions embedded in those models do not predominantly govern geosmin uptake on this composite. The lack of strong adsorbate–adsorbate interactions, as suggested by the Temkin deviation, further corroborates the monolayer, site-specific nature of the process.

Overall, the results indicate that geosmin adsorption onto the Bent-alg-Mag beads predominantly follows the Langmuir isotherm, characterized by monolayer coverage, localized interactions, and limited adsorbate–adsorbate interaction, consistent with adsorption occurring on a structurally homogeneous surface.

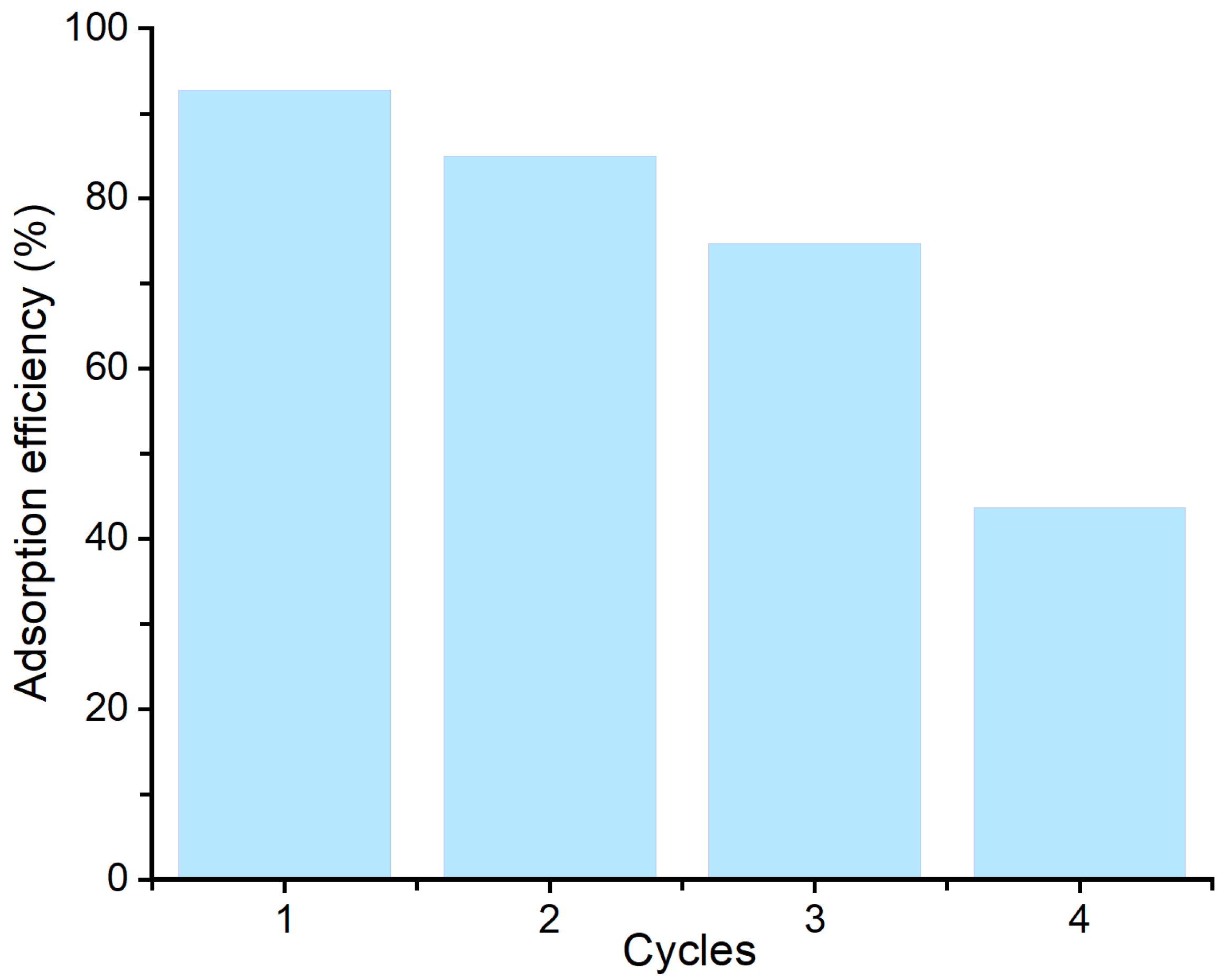

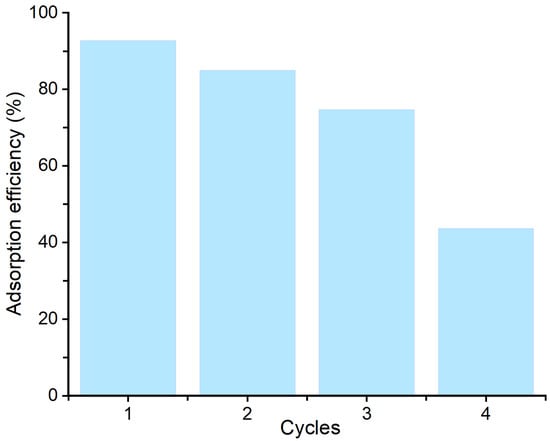

3.8. Reusability Studies

Regeneration and reusability of the Bent-alg-mag beads were evaluated over four consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles to assess their stability and potential for repeated use (Figure 11). The geosmin sorption efficiencies of Bent-alg-mag beads showed a gradual decline from 92.7% in the first cycle to 43.7% after the fourth cycle. This reduction can be attributed to several factors, including incomplete desorption of geosmin molecules leading to pore blockage, partial loss of active sites, and leaching of bentonite particles from the alginate matrix during regeneration. In addition, repeated handling and exposure to regeneration agents may have physically or chemically damaged the beads, compromising their structural integrity and thus diminishing adsorption efficiency. Despite this decline, the beads maintained a high adsorption performance during the first three cycles, retaining more than 70% of their initial efficiency, which demonstrates good regeneration potential for practical water treatment applications. However, the noticeable loss in in performance after multiple cycles highlights the need for improving the mechanical and chemical stability of the composite.

Figure 11.

Adsorption efficiency of the adsorbent over multiple regeneration cycles.

3.9. Comparison of the Adsorption Efficiency of Various Adsorbents for Geosmin

The removal efficiency of Bent-alg-mag beads has been compared with other adsorbents reported in the literature as presented in Table 3. Previous studies have reported considerable variation in geosmin adsorption efficiency depending on the structural and surface properties of the adsorbents used. Traditional adsorbents such as powdered or granular activated carbon generally achieve high removal efficiencies (≈90–99%), although they often require relatively low doses and operate at higher initial geosmin concentrations (e.g., 700–10,000 ng/L). Engineered materials such as metal-doped TiO2 or KOH-activated biochars also demonstrate strong performance, with removals commonly exceeding 90%.

Table 3.

Comparison of the adsorbents reported for geosmin removal from aqueous solution.

In comparison, the Bent-alg-mag composite beads developed in the present study achieved 96.18% geosmin removal within 480 min, ranking among efficient materials reported to date. Although the required dosage appears higher, this is due to the hydrogel nature of the beads, which contain a substantial water fraction and therefore have a higher wet mass relative to their effective dry mass. Despite this structural difference, the removal efficiency remains highly competitive. Beyond their high adsorption capacity, these beads offer a distinct operational advantage; the embedded Fe3O4 nanoparticles impart strong magnetic responsiveness, enabling rapid and simple magnetic separation from aqueous media without the need for filtration or centrifugation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, Bent-alg-mag composite beads were successfully synthesized with a uniform spherical morphology and a rough, porous surface. FTIR spectra verified strong intermolecular interactions among alginate, bentonite, and magnetite, confirming successful composite formation, while XRD analysis revealed the presence of crystalline Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The composite exhibited optimal geosmin removal of 96.18% at pH 9 for an initial concentration of 500 ng/L within 480 min. Kinetic analysis showed that the adsorption process followed a pseudo-first-order model (R2 = 0.9918), signifying physisorption as the dominant mechanism, whereas the Langmuir isotherm best described the equilibrium data (qmax = 16.064 ng/g), indicating monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface. The Bent-alg-mag beads maintained over 70% removal efficiency after three reuse cycles, reflecting good regeneration potential though somewhat limited long-term stability. Overall, this magnetically separable composite offers a cost-effective, reusable, and environmentally friendly adsorbent for geosmin removal in drinking water treatment, with potential for further optimization toward enhanced durability and large-scale application. Future work will assess the impact of natural organic matter (NOM) and co-existing ions, conduct pilot- or full-scale column studies, evaluate the structural stability of the beads under varying water-quality conditions, and develop more environmentally sustainable regeneration methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L.B. and M.D.H.J.S.; Investigation, I.L.B.; Methodology, M.D.H.J.S.; Formal Analysis, I.L.B.; Resources, M.D.H.J.S.; Supervision, M.D.H.J.S.; Visualization, I.L.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, I.L.B.; Writing—review and editing, M.D.H.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Comprehensive Analysis Center for Science, Saitama University, for providing FTIR and XRD analyses and expert guidance. We also thank Weiqian Wang, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Saitama University, for her support in the SEM analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Bent-alg-mag | Bentonite–alginate–magnetic |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GCMS | Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| PFO | Pseudo-first-order |

| PSO | Pseudo-second-order |

| NOM | Natural organic matter |

References

- Li, L.; Yang, S.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y. Variation and Removal of 2-MIB in Full-Scale Treatment Plants with Source Water from Lake Tai, China. Water Res. 2019, 162, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffet, I.M.; Khiari, D.; Bruchet, A. The Drinking Water Taste and Odor Wheel for the Millennium: Beyond Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, F.; Watson, S.B. Biochemical and Ecological Control of Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol in Source Waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4395–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Boyer, G.L.; Zimba, P.V. A Review of Cyanobacterial Odorous and Bioactive Metabolites: Impacts and Management Alternatives in Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2008, 280, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godo, T.; Saki, Y.; Nojiri, Y.; Tsujitani, M.; Sugahara, S.; Hayashi, S.; Kamiya, H.; Ohtani, S.; Seike, Y. Geosmin-Producing Species of Coelosphaerium (Synechococcales, Cyanobacteria) in Lake Shinji, Japan. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ömür-Özbek, P.; Little, J.; Dietrich, A. Ability of Humans to Smell Geosmin, 2-MIB and Nonadienal in Indoor Air When Using Contaminated Drinking Water. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, D.; Westerhoff, P.; Brawley-Chesworth, A. Removal of 2-Methylisoborneol and Geosmin in Surface Water Treatment Plants in Arizona. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 2002, 51, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Cui, Y.; Xu, L.; Huo, S.; Zou, B.; Qian, J.; Ma, A.; et al. Removal of Taste and Odor Compounds from Water: Methods, Mechanism and Prospects. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausen, M.; Grønborg, O. Pilot Scale Testing of Advanced Oxidation Processes for Degradation of Geosmin and MIB in Recirculated Aquaculture. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2010, 10, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Evgenidou, E.; Lambropoulou, D.; Konstantinou, I. A Review on Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Removal of Taste and Odor Compounds from Aqueous Media. Water Res. 2014, 53, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Xu, D.; Li, F.; Fu, M.-L. Removal Efficiency and Possible Pathway of Odor Compounds (2-Methylisoborneol and Geosmin) by Ozonation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 117, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeldt, E.J.; Melcher, B.; Linden, K.G. UV and UV/H2O2 Treatment of Methylisoborneol (MIB) and Geosmin in Water. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 2005, 54, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Bolton, J.R.; Andrews, S.A.; Hofmann, R. UV/Chlorine Control of Drinking Water Taste and Odour at Pilot and Full-Scale. Chemosphere 2015, 136, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.; Tijani, J.; Ndamitso, M.; Abdulkareem, A.; Shuaib, D.; Mohammed, A. A Critical Review on Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol in Water: Sources, Effects, Detection, and Removal Techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, S.; Huck, P.; Slawson, R. Removal of Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol by Biological Filtration. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 49, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Tzamaria, A.; Pedrosa, M.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Silva, A.M.; Kaloudis, T.; Hiskia, A.; Vlastos, D. Spirulina-Based Carbon Materials as Adsorbents for Drinking Water Taste and Odor Control: Removal Efficiency and Assessment of Cyto-Genotoxic Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, T.; Kang, J.-K.; Yargeau, V.; Nam, H.-L.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, J.-W.; Kim, S.-B.; Park, J.-A. Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol Adsorption Using Different Carbon Materials: Isotherm, Kinetic, Multiple Linear Regression, and Deep Neural Network Modeling Using a Real Drinking Water Source. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoschke, K.; Engel, C.; Börnick, H.; Worch, E. Adsorption of Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol onto Powdered Activated Carbon at Non-Equilibrium Conditions: Influence of NOM and Process Modelling. Water Res. 2011, 45, 4544–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.; Newcombe, G.; Sztajnbok, P. The Application of Powdered Activated Carbon for MIB and Geosmin Removal: Predicting PAC Doses in Four Raw Waters. Water Res. 2001, 35, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, Y.; Nakao, S.; Sakamoto, A.; Taniguchi, T.; Pan, L.; Matsushita, T.; Shirasaki, N. Adsorption Capacities of Activated Carbons for Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol Vary with Activated Carbon Particle Size: Effects of Adsorbent and Adsorbate Characteristics. Water Res. 2015, 85, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Huang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Hofmann, R. The Effect of Water Temperature on the Removal of 2-Methylisoborneol and Geosmin by Preloaded Granular Activated Carbon. Water Res. 2020, 183, 116065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, Y.; Nakano, Y.; Hiroshi, H.; Ando, N.; Matsushita, T.; Ohno, K. Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol Adsorption on Super-Powdered Activated Carbon in the Presence of Natural Organic Matter. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62, 2664–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Qiu, L.; Xu, H.; Fan, L.; Meng, S.; Jiang, Z.; Song, C. N-Doping/KOH Synergy in Waste Moss Biochar for Geosmin Removal in Aquaculture Water: Elucidating Surface Functionalization and Activation Mechanisms. Biology 2025, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosa, K.; Nakamura, G.; Miyabayashi, K.; Ishisaki, H.; Takahashi, Y. Adsorption of Geosmin and 2-MIB to Porous Coordination Polymer MIL-53 (Al). J. Water Environ. Technol. 2022, 20, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, W.-J.; Park, H.-G.; Cho, J.-S.; Heo, J.-S. Adsorptive Removal of 2-Methylisoborneol and Geosmin in Raw Water Using Activated Carbon and Zeolite. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2001, 20, 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Xue, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sugiura, N.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, N.; Ying, Z.; Lei, Z. Development of Long-Life-Cycle Tablet Ceramic Adsorbent for Geosmin Removal from Water Solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, L.; Zuo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, L. Adsorption of 2-Methylisoborneol and Geosmin by a Low-Cost Hybrid Adsorbent Synthesized from Fly Ash and Bentonite. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 2011, 60, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.A.; Ahmad Zaini, M.A.; Surajudeen, A.; Aliyu, E.-N.U.; Omeiza, A.U. Surface Modification of Low-Cost Bentonite Adsorbents—A Review. Part. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Developments in Bentonite-Based Materials Used as Adsorbents for Wastewater Treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 241, 1091–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Xie, C.; Agar, O.T.; Barrow, C.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A. Alginates from Brown Seaweeds as a Promising Natural Source: A Review of Its Properties and Health Benefits. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 2682–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-Khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braccini, I.; Pérez, S. Molecular Basis of Ca2+-Induced Gelation in Alginates and Pectins: The Egg-Box Model Revisited. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-M.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; He, T. Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Application in Water Treatment. Nanosci. Nanotechnol.-Asia 2011, 1, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akchiche, Z.; Abba, A.; Saggai, S. Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Industrial Wastewater. Alger. J. Chem. Eng. AJCE 2021, 1, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi, N.; Najafpour-Darzi, G. Manganese Ferrite (MnFe2O4) Nanoparticles: From Synthesis to Application—A Review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 103, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S. Preparation of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles with Adjustable Morphology. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 475, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasooriya, I.L.; Senavirathna, M.D.H.J.; Wang, W. Application of Activated Carbon/Alginate Composite Beads for the Removal of 2-Methylisoborneol from Aqueous Solution. AppliedChem 2025, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davranche, M.; Lacour, S.; Bordas, F.; Bollinger, J.-C. An Easy Determination of the Surface Chemical Properties of Simple and Natural Solids. J. Chem. Educ. 2003, 80, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senavirathna, M.D.H.J.; Jayasekara, M.A.D.D. Temporal Variation of 2-MIB and Geosmin Production by Pseudanabaena Galeata and Phormidium Ambiguum Exposed to High-intensity Light. Water Environ. Res. 2023, 95, e10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati-Ashtiani, M. Characterization of Nano-Porous Bentonite (Montmorillonite) Particles Using FTIR and BET-BJH Analyses. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2011, 28, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.R.; Lalhmunsiama; Bajaj, H.C.; Lee, S.-M. Activated Bentonite as a Low-Cost Adsorbent for the Removal of Cu(II) and Pb(II) from Aqueous Solutions: Batch and Column Studies. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 34, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Loh, M.; Aziz, J. Preparation and Characterization of Activated Carbon from Oil Palm Wood and Its Evaluation on Methylene Blue Adsorption. Dye. Pigment. 2007, 75, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarai, A.; Kasparkova, V.; Sedlacek, T.; Sáha, P. On the Development and Characterisation of Crosslinked Sodium Alginate/Gelatine Hydrogels. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 18, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollah, M.Z.; Faruque, M.R.; Bradley, D.; Khandaker, M.U.; Al Assaf, S. FTIR and Rheology Study of Alginate Samples: Effect of Radiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 202, 110500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, N.C.C.; Mansur, M.B.; de Mello Ferreira, A. Characterization and Chemical Stability of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Magnetic Nanoparticles. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, R. Infrared Spectra of Ferrites. Phys. Rev. 1955, 99, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipunova, V.O.; Nikitin, M.P.; Lizunova, A.A.; Ermakova, M.A.; Deyev, S.M.; Petrov, R.V. Polyethyleneimine-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Cell Labeling and Modification. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 452, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, L.; Jiang, W.; Xuan, Y.; Lu, W.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Gu, Z. Adsorption Mechanism of Rhein-Coated Fe3O4 as Magnetic Adsorbent Based on Low-Field NMR. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aichour, A.; Zaghouane-Boudiaf, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Activated Bentonite/Alginate Composite to Improve Its Effective Elimination of Dyes Stuff from Wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaria, S.; Nussinovitch, A.; Nir, S.; Mordechai, S.; van Rijn, J. Removal of Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol from Aquaculture Water by Novel, Alginate-Based Carriers: Performance and Metagenomic Analysis. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 42, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafuka, A.; Nagasato, T.; Yamamura, H. Application of Graphene Oxide for Adsorption Removal of Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol in the Presence of Natural Organic Matter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; An, B.M.; So, S.; Chae, A.; Song, K.G. Simultaneous Control of Algal Micropollutants Based on Ball-Milled Powdered Activated Carbon in Combination with Permanganate Oxidation and Coagulation. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alver, A.; Baştürk, E.; Altaş, L.; Işık, M. A Solution of Taste and Odor Problem with Activated Carbon Adsorption in Drinking Water: Detailed Kinetics and Isotherms. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 252, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.; Khan, Z.; Maqbool, N.; Qazi, I.A.; Awan, M.A. Comparison of Adsorption Capability of Activated Carbon and Metal Doped TiO2 for Geosmin and 2-MIB Removal from Water. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 479103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.; Losso, J.N.; Marshall, W.E.; Rao, R.M. Physical and Chemical Properties of Selected Agricultural Byproduct-Based Activated Carbons and Their Ability to Adsorb Geosmin. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 84, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Peng, F.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, Z. Adsorption of Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol onto Granular Activated Carbon in Water: Isotherms, Thermodynamics, Kinetics, and Influencing Factors. Water Sci. Technol. 2019, 80, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.