Abstract

This research focuses on ontology-driven conversational agents (CAs) that harness large language models (LLMs) and their mediating role in performing collective tasks and facilitating knowledge-sharing capabilities among multiple healthcare stakeholders. The research addresses how CAs can promote a therapeutic working alliance and foster trustful human–AI collaboration between emergency department (ED) stakeholders, thereby supporting collaborative tasks with healthcare professionals (HPs). The research contributes to developing a service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF) to promote co-creation and collaborative learning among patients, CAs, and HPs, and improve information flow procedures within the ED. The research incorporates agile heavy-weight ontology engineering methodology (OEM) rooted in the design science research method (DSRM) to construct an ontological metadata model (PEDology), which underpins the development of semantic artifacts. A customized OEM is used to address the issues mentioned earlier. The shared ontological model framework helps developers to build AI-based information systems (ISs) integrated with LLMs’ capabilities to comprehend, interpret, and respond to complex healthcare queries by leveraging the structured knowledge embedded within ontologies such as PEDology. As a result, LLMs facilitate on-demand health-related services regarding patients and HPs and assist in improving information provision, quality care, and patient workflows within the ED.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) advancements with generative AI [1] are increasingly impacting many aspects of life and work and have led to the rise in human–AI collaboration or augmentation to keep humans in the loop and create responsible AI [2]. As intelligence technologies rapidly advance and become more ubiquitous, different autonomous technology-based agents are utilized with their functional capabilities and differentiated through implications into broader categories for human–machine setups as intelligence technologies quickly improve and become more widespread. There are three types of agents that can be used to establish human–machine configurations, interactions, and collaborations: (i) disembodied agents, like chatbots [3]; (ii) embodied agents, like humanoid or social robots [4]; and (iii) virtual agents or avatars [5]. In addition, the inclusion of AI-driven applications, such as intelligent conversational agents (CAs) with the advancement in large language models (LLMs) [6,7], marks a significant milestone in AI, showing transformative improvement over traditional AI models [2]. LLMs have revolutionized and achieved significant heights in almost every industry, especially in healthcare, to thoroughly understand how humans can collaborate successfully with increasingly intelligent systems to encourage the concepts of digitization and digitalization within organizations. CAs provide users with natural language interfaces that simplify use, expedite the fulfillment of user inquiries, and aid in converting physical information into digital form [8]. Digitalization reflects the socio-technical process of leveraging CAs to achieve digital transformation within the healthcare context. Once developed, these sophisticated, individualized technologies offer standardized treatment regardless of moral judgment, are scalable, have low operating costs, and are easily linked with legacy healthcare systems [9].

LLMs have significantly transformed and differed from traditional AI models in four ways: (1) a general-purpose AI model is adept at various tasks, such as language understanding, generation, and reasoning. In contrast, traditional AI models are generally task-specific and dedicated only to singular tasks [2]. (2) LLMs have superior scale and learning capabilities and handle the exponential influx of industry data. (3) LLMs specialize in understanding unstructured data (i.e., text), whereas traditional AI systems tend to be geared towards processing structured data (i.e., ontological data). (4) LLMs revolutionize user interaction by enabling end-to-end conversational engagements, closely simulating real-world human conversations [2].

Research on CAs has been considered to be among the most active recently. Well-known, important manufacturers have introduced CAs that cover the general natural language conversational interface with people, such as Google Assistant (https://assistant.google.com/), Amazon’s Alexa (https://developer.amazon.com/en-US/alexa), and Apple’s Siri (https://www.apple.com/siri/) [10]. These human-centered AI systems are fully capable of performing and carrying out a wide range of tasks, including responding to inquiries; giving users access to intricate data about particular diseases, like diabetes [11]; carrying out digital tasks, like scheduling patient appointments and performing medical assessments; making recommendations for goods and services; and understanding the context of conversations. They can also act as a mediator to help end users share knowledge and learn across various domains, particularly in the healthcare industry [12].

According to [13], CAs are social robots with intelligence that engage in human-to-human conversations using natural language. They are equipped with machine learning (ML) skills to manage domain and contextual knowledge and its representation. Their use in the healthcare setting to address several issues during and after the pandemic situation (e.g., COVID-19), such as a shortage of qualified clinical workers and healthcare professionals (HPs), supporting overburdened HPs, and improving care-related services and quality, is auspicious given their relatively recent and promising potential contribution [14]. Healthcare organizations mainly strive to incorporate innovative human-centered AI solutions to automatically manage users’ inquiries and experiences, stimulate human-like mimics, and respond to information related to a specific domain. AI-driven solutions frequently serve as the initial touch point for patients, triaging and preventing the overburdening of healthcare resources [9].

The healthcare applications of CAs do more than only provide patients with answers to particular health-related questions through various interactive texting and voice patterns. They also create value and facilitate HPs as a mediating tool or agent for teamwork collaboration and performing collaborative tasks with shared knowledge, reduced administrative overhead, and improved decision support by offering evidence-based recommendations in a panic situation or during peak hours, especially in the emergency departments (EDs) of hospitals [15]. It also reduces physicians’ administrative workload during peak hours [16]. CAs help in improving social isolation and loneliness and help in avoiding depression and anxiety among hospital patients [17].

CAs in the healthcare sector cover closed context-based knowledge and domain experts’ knowledge, such as competencies, skills, and manageability. Establishing a platform for knowledge exchange in healthcare systems is one of the complex tasks that is still vital due to the requirement for data interoperability and uniform healthcare language throughout healthcare information systems (ISs) [18], especially in the ED context. The literature research reveals several encouraging gaps, including differences in pediatric clinical practice [19] and pediatric preparedness in the emergency room [20], and knowledge translation (KT) [21], which show a need to design CAs designated to ED (e.g., pediatric emergency department (PED)) care and for apparent outcomes.

The ED is a central point and a critical care entity that facilitates and provides health-related services to individuals with diverse healthcare needs. In this setting, managing patients can pose considerable challenges, particularly in addressing significant overcrowding issues within hospital premises. In the literature, many studies have addressed and investigated healthcare providers’ and patients’ perspectives and explored their experiences in navigating these demanding environments. It is necessary to optimize the ED care center and try to overcome unwanted barriers, which necessitate attention to include different factors of interpersonal, environmental, and system levels. Optimizing ED care and overcoming barriers necessitates attention to interpersonal, environmental, and system-level factors. These factors categorically target seamless communication, positive interaction with natural language, and minimized waiting times. These include effective communication, positive interactions and attitudes, minimizing wait times, judicious use of restraints, and normalizing stress traumas in waiting areas through patient medical and discharge planning and knowledge sharing, particularly in high-stress situations like the PED. These seemingly insignificant factors can enhance care strategies, policies, resource allocation, and expertise, improving the quality of care delivered [22].

Unlike prior research, which usually focuses on ontology-driven knowledge representation for domain-centric applications, LLMs empower AI-powered systems, especially CAs, which emphasize linguistic competence alone. This research bridges these two paradigms and showcases the integration of an ontology-driven and LLM-enabled framework. We proposed service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF) establishes a foundation at two levels: first, for ontologies that provide structured, semantic interpretable domain and contextual knowledge; second, LLMs enhance adaptability, reasoning, and natural conversational fluency in CAs. Integrating two paradigms allows knowledge to be created and shared dynamically, adapts to different healthcare contexts, and ensures reliable responses—moving beyond traditional CAs by supporting human-centered collaboration in emergency care settings. Hence, the novelty of this research artifact lies in combining ontology-driven and semantic interpretability with generative adaptability (LLM-driven) to achieve a trustworthy, transparent, and explainable human–AI collaboration in ED contexts.

This research focuses on twofold research questions, which are interlinked for better understanding and realization of the domain’s discourse, as follows:

RQ1.

How does CA design induce therapeutic working alliance and develop trustful collaboration between multi-stakeholders using shared knowledge within EDs?

RQ2.

How does an ontology-driven framework leveraging LLMs enhance CA’s shared collaboration with healthcare professionals (HPs) to perform collaborative tasks and shared knowledge to avoid overcrowding issues within EDs?

The research proposes an ontology-driven framework for building an integrated data repository to organize domain, contextual knowledge, and domain-expert expertise in healthcare. The ontology-driven framework facilitates showcasing co-working alliance patterns between patients and HPs through knowledge sharing and learning abilities within the PED. The ontology-driven approach helps deploy a service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF) leveraging LLMs that promote shared knowledge among multidisciplinary healthcare clinicians and patients to improve EDs’ care. SHAICF emphasizes shared knowledge engineering principles through semantic techniques such as ontologies. It helps to disseminate contextual, personalized, and domain-expert knowledge. The proposed framework addresses existing barriers and advocates for achieving desirable goals for improving healthcare services. The proposed framework that harnesses LLM capabilities can be linked with interlinked Health Information Systems (HISs) to support the shared mechanism of dispersing knowledge and provide appropriate advice or recommendations to verify the knowledge base.

This research proposes an ontology-driven approach to building intelligent knowledge bases (KBs) that support collaborative assistance CAs leveraging LLMs’ capabilities for better interaction between HPs, patients, and family members. The proposed ontology-driven framework supports threefold goals: (i) develop a domain-centric ontological model that covers contextual knowledge and conversational modeling that reflects the domain discourse; (ii) follow a systematic procedure of shareable ontology engineering methods (OEMs) using Ontology Design Patterns (ODPs) [23]; and (iii) focus on evaluation and refinement through competence questions (CQs) and information retrieval (IR) using LLMs and generating customized query structures to showcase which type of services can be offered by CAs in PED upon arrival and interlinked with other ISs and also used by multidisciplinary teams in a specific context like PED.

The proposed ontology-driven framework leveraging LLMs helps to integrate different applied ontologies, such as Conversational Ontology (Convology) [24], Service Ontology (SO), Resource Ontology (RO), Personalized Ontology (PO), and Disease Ontology (DO) (https://disease-ontology.org/ (accessed on 5 July 2025)) in value creation. The framework also helps to accommodate and provide synergy among various knowledge models (KMs), including the Domain Model (DM), context model (CM), Role Model (RM), and Competencies Model (CompM) related to the PED to build an intelligent knowledge base to manage patient consultation and monitoring services in the development of intelligent CAs. The framework also enables improving patient workflows, avoiding overcrowding in the PED, and facilitating multidisciplinary HP teams in specific contexts. The ontology-driven approach lays a foundation for better collaboration between CAs and HPs and controlled interaction with patients and family members through texting and speech recognition abilities in AI-powered applications like CAs. In addition, it contributes to developing health services related to patient consultation and monitoring, which are crucial to preventing overcrowding in the PED. The LLMs help generate the initial assessment report and provide appropriate advice or recommendations verified from the knowledge base (ontological model).

We followed the design science research methodology (DSRM) and its guiding principles [25,26] to develop service-oriented semantic artifacts that reflect the discussion of PED in a systematic way. The paper is structured and arranged as follows: Section 2 briefly displays the theoretical foundation of CAs in digital health; patient empowerment; and applied ontologies, frameworks, and LLMs in the HMI domain. Section 3 presents a methodology rooted in the DSRM. Section 4 describes the anatomy of the ontology-driven service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF), the implementation, and the evaluation and testing results. Section 5 defines the discussion part, and Section 6 ends with the conclusion part.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conversational Agents in Digital Health

Proactive CAs are more beneficial and challenging to create and execute in the context of digital health because they consider users’ opinions and experiences [27]. A study conducted in 2020 found that over 83 million Americans utilized voice assistants in the United States, including Google Home, Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Cortana, and CAs. We discussed how CAs may allow these trends to combine user requirements, data, and health services smoothly. In healthcare, various CAs are helpful, ranging from bi-directional dialogue systems like CAs (e.g., a standard hospital system to triage incoming phone calls regarding severity, urgency, and pathology) and embodied agents. The proactiveness of these goal-oriented CAs can be demonstrated in several areas of training, education, assistance, prevention, diagnosis, and senior support, where these goal-oriented CAs show their proactive nature [28]. Therefore, we included certain Design Principles (DPs) consisting of certain recognized Meta-requirements (MRs) [29] acquired from the knowledge acquisition (KA) process (e.g., interviews, etc.) when creating focused, goal-oriented CAs, especially in PED. These identifiers include sociability, proactive communication ability, transparency, flexibility, seamless usability, and error handling in the development phase [30].

2.2. Conversational Agents for Patient Empowerment

In addition to enhancing information flow and provision (IP) inside the medical unit, the function of CAs addresses self-diagnosis and self-management of health issues, particularly in EDs (e.g., PED). Distinct indications indicate distinct requirements for health CAs that enable patients and family members to comprehend health information, make educated decisions, take charge of their health and well-being, and communicate more effectively with HPs. First, it dialogues with the users most naturally. Second, it can comprehend, interpret, and integrate health data from various sources, including health information, health conditions, empowerment level, and needs. Third, it gives patients their current status with relevant, specialized, and suited information. Fourth, it also serves as a guide for selecting information understandable to patients and their families, boosting acceptance and trust. It enables patients and their families to ask questions in natural language about complaints, illnesses, and present health status (e.g., symptoms, conditions, etc.). It empowers ways to enhance health and well-being [13].

2.3. Applied Ontologies in Human–AI Collaboration and Value Creation

According to Pulido et al. (2006) [31], the definition of ontology engineering (OE) is “a formal, explicit specification of a conceptualization” that explains how to construct an applied ontology from a variety of knowledge sources. Its six phases are gathering, extracting, organization, combining, refining, and retrieval. Five steps of the process are linked to building an ontology, and the sixth step is reserved for ontology development [32]. Ontology offers a shared comprehension of the norm. An ontology establishes a shared comprehension using standardized terminology within a specific domain, facilitating communication among individuals and diverse, dispersed systems. Ontologies provide a unique representation of knowledge and help in sharing and collaboration. It makes it possible to unambiguously record data in a knowledge base [18]. Several medical applied ontologies might enhance privacy in electronic patient data access, including Medical Language Systems (UMLS) and SNOMED-CT [33]. Through semantic access to electronic health records (EHRs), the ontology facilitates the sharing of healthcare knowledge, i.e., [18] created clinical terminology for specific and interchangeable terms in EHRs. Moreover, ontology’s hierarchical structure improves control over who may access and use personalized medical data. Ontologies play a significant role in value creation, especially in health data integration and interlinking, information management, semantic understanding and interoperability challenges, knowledge representation, and enhanced decision-making capabilities that enable AI systems to understand and interpret information [34,35].

Human–machine interaction (HMI) and collaboration [36] have emerged as an ideal wave for developing a co-working phenomenon between humans and machines as a mediating tool or agent for supporting human capacity improvement and efficiency at work. The collaboration canvas efficiently covers interaction, cognition, and metrics. Several examples of how CAs from the literature have improved people’s lives include biofeedback systems, schooling and learning environments, healthcare, entertainment, and geriatric monitoring systems [37]. Here, the role of ontologies such as context model-focused ontology [38] encourages the HMI phenomenon to the next level by sharing conceptual knowledge with reasoning abilities. The ontologies, including conceptual models and computational semantic artifacts, are mainly used to structure entities and relationships to cover real-world discussions. Ontologies also infer knowledge, support reasoning, and effectively develop intelligent interactive systems (e.g., CAs and recommended systems). It also supports developing some embedded systems and other approaches involved in developing frameworks (e.g., service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework), which are helpful in the HCI domain [39].

Similarly, Umbrico et al. (2020) [40] suggested “sharing-work ontology”, which was inspired by “Share-work” (https://sharework-project.eu/ (accessed on 5 July, 2025)) (a H2020 research project funded by the European Commission within Factories of the Future) that efficiently captures the contextual and domain knowledge related to specific scenarios like PED. It may lead to the development of a service-oriented framework that supports human–machine interaction and collaboration.

2.4. Ontology-Driven Frameworks and Large Language Models

In the realm of AI, ontologies and LLMs have gained significant attention, especially in academia and industry. Ontology-driven frameworks provide a structured mechanism for organizing and reasoning about information [31]. Recently, several studies have explored the inclusion of LLMs such as BERT [41] and GPT-4 in healthcare applications, including conversational agents in patient triage and clinical decision support. These LLMs execute strong capabilities in understanding natural language and maintaining conversational contexts, especially interpreting patient queries and generating contextually appropriate responses across various domains [42,43]. Both methodologies have unique roles in supporting conversational agents, intelligent decision-making, and intelligent interface construction in recent times.

The ontology-driven framework offers a robust way of modeling knowledge, ensuring precision, compliance with standards, and interoperability [34] in health applications like emergency department triage, diagnostics, and decision support systems. Ontology-driven frameworks help to construct domain-centric knowledge [44], allow rule-based reasoning for decision-making [45], and follow standardized medical vocabularies and coding systems such as ICD-10 or SNOMED CT [46]. It also contains some limitations, such as limited flexibility due to its rigidity [47] and labor-intensive development [45].

Similarly, LLMs are based on the transformer model and built using deep learning architectures. These models are pre-trained based entirely on unstructured data and can perform various language tasks, including question-answering, task summarization, translation, and language generation. These tasks are fulfilled using different characteristics of natural language understanding [42] and generalization across domains [43]. LLMs also contain limitations in terms of a lack of domain-centric precision or non-compliant information [47] and explainability challenges, as LLMs operate as black boxes where the reasoning behind their outputs is not easily interpretable [48], and inconsistent compliance with standards [45].

Both approaches are used in constructing intelligent systems like CAs, particularly in healthcare. Ontology-driven systems rely on explicit knowledge and rule-based schemes to ensure compliance, explainability, and precision. At the same time, LLMs strictly follow statistical patterns and considerable datasets to generate responses and handle natural language, offering unmatched flexibility [49].

3. Methodology

This section illustrates the systematic steps to build a service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF). We customized DSRM [25,26,27,28,29] activities and their guiding principles to create an ontology-driven framework as an artifact for improved collaboration between patients and HPs. We also highlighted the invaluable importance of the shareable ontology engineering methods (OEMs) in the ontology development process, with tight coupling to promote seamless information integration and interoperability. By adhering to these principles, we created an ontology-driven framework that supports effective collaboration, creating value, knowledge sharing, and better healthcare outcomes. Table 1 in our research illustrates the construction of agile OEMs and the activities’ analogies based on established methodologies like DSRM [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

Table 1.

Heavyweight shareable ontology engineering methodology (OEM) rooted in the DSRM process.

3.1. Case Study: The Karolinska University Hospital

The case study “Organizational Transformation at a Pediatric Emergency Department,” from US Acute Care Solutions (USACS) (https://www.usacs.com/services/case-studies/organizational-transformation-at-a-pediatric-emergency-department (accessed on 21 June 2025)) served as the model for this. It is based on real-time observations at the Karolinska Hospital’s Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) in Stockholm, Sweden. We organized and designed modeling workshops with multidisciplinary experts at the hospital. We outlawed specific steps [51] to improve communication with domain users, healthcare providers, and specialists in charge of emergency patient treatment protocols. They also explained ED processes. We examined the information flow mechanisms of the patient’s care and admission process at PED. We came to some critical conclusions on patient-centric treatment approaches after performing more analysis and reaching an agreement. According to Fareedi et al. (2023) [52], the author’s goal was to change the ED from an “As-Is situation” to a “To-Be situation”. A comprehensive desktop research indicates that patients make up “75%” of ED visits annually, and those affected are used to handling unanticipated circumstances like long wait times and crowding [52].

From the standpoint of a hospital, an inefficient ED has an impact on all of the operations and processes in the ED. Thus, it has to be well-organized. We must use classified ISs, such as electronic health records (EHRs) and triage (referred to as a decision support system (DSS), to obtain the proper medical aid. The patient’s health and information exchange with other medical professionals are the main priorities of the EHR. Similarly, the patient’s medical and treatment history is contained in the EMR. Because it assists in setting patient priorities for care and treatment, the function of triage is auspicious in this situation. Unfortunately, there is a bottleneck at triage in the ED due to the large number of patients and the lengthy waiting list. Hence, CAs—chatbots, social robots, etc.—that enable numerous phases in inconsistently practiced front-end triage procedures are necessary for healthcare stakeholders. These also lessen the high proportion of patients handled in the ED waiting area during busy times. To address communication problems and maintain data silos inside departments and treatment areas, they also assist in launching single-window operations [52,53].

From the standpoint of the patient, prolonged ED wait times, combined with elevated anxiety levels, might cause patients to lose faith in medical services. Poor ED performance jeopardizes patient safety and health and erodes public trust in the medical community [52].

We developed the “shareable ontology” customized with the help of agile ontology engineering methodologies (OEMs) called (PEDology), representing the PED environment and the overcrowding situation. PEDology provides a case of model metadata based on the Overcrowding Estimation Score (OES) [54] to evaluate the overcrowding situation in the ED and showcase the court-score-coloring scheme to highlight the urgency of medical assistance in the waiting area of the ED. The details and description of the case study can be seen [52,53,54,55], and data is taken from Barata et al. 2018 [56] to make it more convincing as a global challenge [57]. In shared collaborative ontology development, we tried to incorporate different concepts and values related to the EDs [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] to make it a more realistic contribution and define a real-world ED scenario in the hospital’s medical unit to build up the case model.

3.2. A Heavy-Weight Methodology for Shareable Ontology Engineering

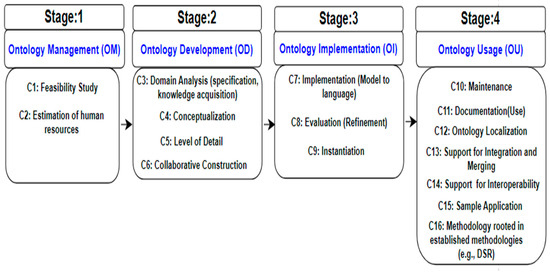

Various mature ontology development methodologies, such as Methontology [59], TOVE [60], and Collaborative Methodology (CM) [61], have been proposed in the literature based on context and requirement elicitation in different domains. These methodologies provide systematic and standardized ontological development procedures, ensuring quality results. In the ontology development process, ontology developers should select an appropriate method based on the metadata requirements and nature of the domain to streamline the ontology construction process and improve ontology quality. However, these methodologies are benchmarks for developing domain ontologies and knowledge bases as semantic artifacts. In this research, we used agile ontology engineering methodologies (OEMs) to help customize shareable ontology development, which is a challenging task in a collaborative, decentralized environment where domain knowledge can be added and modified based on user demands and heavily inspired by agile software development paradigms [62]. Figure 1 describes the systematic way of developing shareable ontology engineering, which is customized [62] and divided into four stages such as Ontology Management (OM), ontology development (OD), Ontology Implementation (OI), and Ontology Usage (OU) [50]. These four stages of shared ontology development engineering are based on specific criteria for creating domain ontologies at each level, as follows:

Figure 1.

Shareable ontology engineering development process.

- 1.

- Stage 1 explains the feasibility and viability of the research and defines the cost estimation of human resource assessment. Drawing on the knowledge and expertise of knowledge engineers, software engineers, ontologists, qualified domain specialists, and a technical writer for the documentation, this describes the team’s skills, experience, and size needs.

- 2.

- Stage 2 covers the amount of depth, conceptualization, collaborative building, and domain analysis (specification and knowledge acquisition (KA)). Domain analysis must include advice about a specific domain and require many resources. Extracting the maximum information from the domain experts is a challenging task, so it is essential to utilize KA techniques such as modeling workshops and seminars to better understand the ontologies’ terminologies and core parts for team members. The conceptualization phase ensures that the suggested methodology includes or supports the conceptualization activities. Does the methodology include information on methods, and what do they entail? Furthermore, in the collaborative construction, various sub-ontologies are interlinked and aligned using ODPs within seed ontology (a federated ontology) related to the domain, such as PED.

- 3.

- Stage 3 describes how to put the shared ontology and model into practice, transform it into a conceptual ontology model to create a machine-readable ontology, and represent the knowledge in various formats for data rendering (e.g., RDF/XML (https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)), OWL/XML (https://www.w3.org/TR/owl-xmlsyntax/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)), Turtle (https://www.w3.org/2007/OWL/wiki/PrimerExampleTurtle (accessed on 20 June 2025)), and JSON-LD (https://www.w3.org/TR/json-ld11/ (accessed on 20 June 2025))). This step also specifies the evaluation component, which calls for the evaluator to use appropriate instantiation techniques and procedures while also improving their understanding of the ontology and installation.

- 4.

- Stage 4 serves for maintenance, where applied ontologies and keeping documentation with versions continuously face the evolution challenge. This phase also ensures that the developed ontology is constructed in a natural language that supports the localization concept. Furthermore, diverse applied ontologies and heterogeneous knowledge models are integrated, interlinked, and consolidated into a unified seed ontology (a federated ontology) using this systematic, rigorous procedure, enabling interoperability and facilitating seamless integration into the planned project.

4. Results: Implementation and Testing

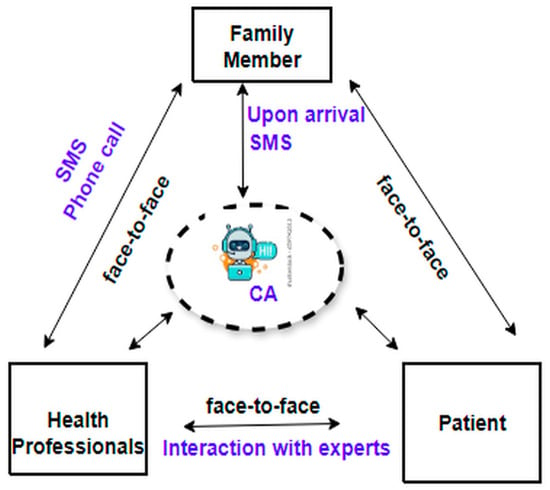

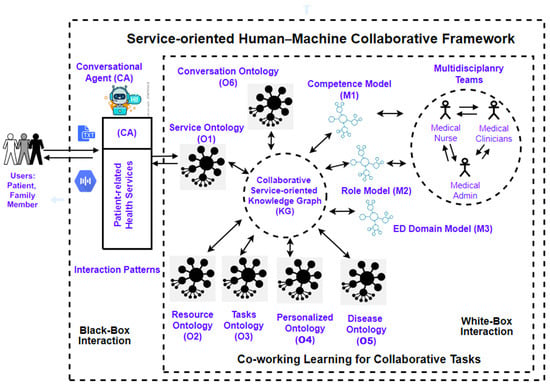

Figure 2 and Figure 3 are inspired by Kowatsch et al. (2021) [63] and describe the interaction and co-working patterns between multi-stakeholders such as patients, family members, and EDs. Here, CAs can be a mediating tool or agent to support the patient in interactions, stimulate users’ queries, and give answers efficiently upon arrival. It also facilitates contact with family members before arrival at the ED through SMS or phone call for demanding medical urgency straight away. It also allows HPs to mitigate CAs in overcrowding situations and simultaneously works as a helping hand to enhance patient flows efficiently.

Figure 2.

Human–AI collaboration.

Figure 3.

Service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF).

4.1. Service-Oriented Human–AI Collaborative Framework (SHAICF)

The anatomy of the service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF) (see Figure 3) contains two components: (i) the White-box Interaction Container and (ii) the Black-box Interaction Container. The White-box Container explains the inside mechanism of the co-working learning used for performing some collaborative tasks by using different ingredients of knowledge models (KMs), including the context model (CM), Competence Model (CompM), Role Model (RM), Domain Model (DM) along with various applied ontologies such as Service Ontology (O1), Resource Ontology (O2), Task Ontology (O3), Personalized Ontology (O4), Disease Ontology (O5), and Convology developed for the conversation between human and machine.

The White-box Interactive Container is beyond the expectations of naive users, such as patients and family members, but it is evident to technical and domain users. The CM describes the context of PEDs. The CompM models describe the competencies of the multidisciplinary HPs and their criteria for serving in the EDs (e.g., PED). The RM explains specific roles (e.g., pediatric nurse) in performing collaborative tasks related to PEDs and their environment. The DM explains vital concepts and their relationships to cover the understanding of ED scenarios like PEDs effectively.

Similarly, “O1” capitalizes all the necessary information related to the health-related queries and services CAs can offer in an emergency at PED. “O2” explains the resources utilized during the pre-assessment medication and after medication at PED. “O3” defines some dedicated tasks at the time of patient arrival and during the detailed examinations of the patient’s current situation at PED. “O4” designs services to meet individual requirements and is related to HPs. Convology explains the analogy of conversation between humans and machines and how CAs follow interaction patterns to communicate with patients or family members upon arrival. Using applied ontologies, healthcare organizations can achieve a common platform for understanding terminologies and relationships between various concepts. This semantic clarity can lead to more effective communication and collaboration among stakeholders, potentially creating value.

The Black-box Interactive Container offers interaction patterns for text and speech capabilities, facilitating natural communication with CAs. It also provides a range of patient health-related services, activating them for end-users upon request, whether in emergencies or otherwise (refer to Figure 3). Figure 2 explains the interaction pattern between stakeholders with different communication channels according to their ease and convenience with CA. CAs help to establish seamless communication, either via the web or in person, without any delay, especially during panic and peak times in a PED.

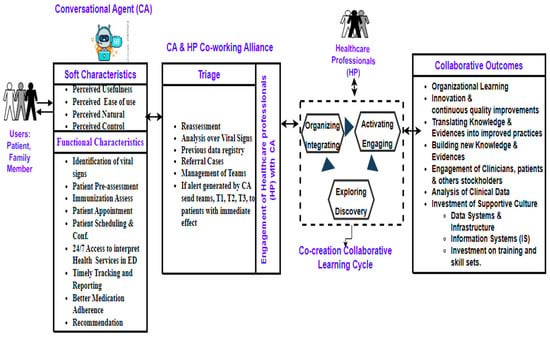

4.2. Conversational Agents and Healthcare Professionals Co-Working Alliance

Figure 4 illustrates the phenomenon of mediation between the patient’s family members and HPs. It works layer to layer and creates a synergy between multidisciplinary HPs, CAs, and patients or family members in seamless communication and access to health-related services whenever needed, potentially resulting in value creation. This conceptual model also explains the characteristics of CAs, including functional and soft characteristics. Here, soft characteristics are classified into usefulness, ease of use, behaving naturally, and complete control to operate and access relevant information from CAs efficiently.

Figure 4.

Conversational agent and healthcare professionals’ co-working alliance workflow.

Similarly, it offers some patient-centric health-related available functional services at the time of arrival, such as identifying vital signs, patient pre-assessment, immunization assessment, patient appointment, patient scheduling and confirmation, 24/7 access to interpreting, health services in EDs, timely tracking and reporting, better medication adherence, recommendations, and potentially service-oriented value creation. It is also interlinked with triage to generate alerts in case of severe patient health conditions upon arrival. Simultaneously, HPs are more benefited by using CAs and the co-working alliance phenomenon to improve the patient information flow and IP procedures in EDs. They also receive some relief, especially during peak times in the ED, using the collaboration of CAs. HPs also make quality time to perform their delicate tasks without fatigue and stress to organize, integrate, activate some tasks, engage resources, and explore patient-related data efficiently. The healthcare stakeholders came across tremendous outcomes after following the CAs and HPs’ co-working alliance procedure and collaboration.

These results are interpreted as organizational learning; innovation; ongoing quality improvements; converting clinical data into better practices; creating new knowledge and evidence; analyzing clinical data for better decision-making; and investing in a supportive culture that includes infrastructure and data systems, IS, training, and skill set enhancements that add value.

4.3. Ontological Metadata Model of Pediatric Emergency Department (PEDology)

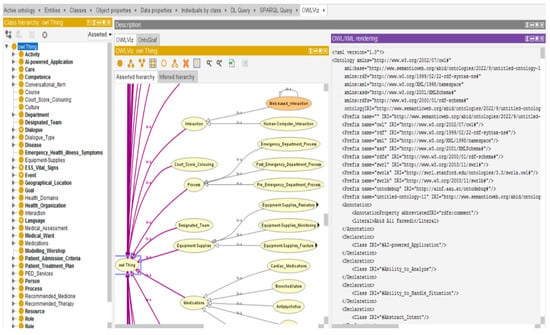

The ontological metadata model (PEDology) is designed based on the Karolinska University Hospital case study, and USACS discussed in Section 3.1, to better understand and realize the ED situation (case scenario) in a hospital’s medical unit. This PEDology metadata model is constructed in an ontology editor (e.g., Protégé, Topbraid Composer (https://allegrograph.com/topbraid-composer/ (accessed on 18 June 2025)).

Figure 5 depicts the semi-automated way of conversation from textual or contextual knowledge that reflects PED discussion and incorporates USACS data related to the ED’s context in standard structured data, which can be used in different data formats and reusable for data interoperability in other interlinked healthcare systems. In the ontology development process, we followed the agile OEM principles. We generated key concepts, defined entities and their relationships (object properties) between concepts, defined data characteristics, and proposed business rules. They provided class axioms for reasoning to construct an intelligent knowledge base (KB). Knowledge engineering’s (KE) objective is to develop a domain-oriented knowledge graph (KG) (an integrated data repository) that can create value through integrated data that focuses more on the emergency context.

Figure 5.

Ontological metadata model (OntoM) of pediatric emergency department (PEDology).

There are 271 classes, 6242 axioms, 5273 logical axiom counts, 959 declaration axiom counts, 247 object property counts, 26 data property counts, 413 individual counts, and 6 annotative property counts in the PEDology (https://github.com/abid-fareedi/EmergencyDepartmentOntology (accessed on 18 June 2025)) metadata model statistics. Using ODP and other applicable ontologies like “O1,” “O2,” “O3,” “O4”, “O5”, and Convology (https://github.com/kastle-lab/kg-chatbot/blob/master/schemas/convology.owl (accessed on 15 June 2025)), we developed the conceptual model into a machine-readable structure using a formal OEM. The PEDology metadata model depicts the ED situation and rationally targets overcrowding with improved information flow processes and information provision, presented in Figure 5.

As a novel data paradigm, the ontological metadata model (PEDology) combines technologies, terminologies, and data cultures that reflect domain knowledge in a human- and machine-readable format. The ontology-driven framework is one of the potential solutions for creating common terminology. With several forms, including Turtle, RDF/XML, OWL/XML, and JSON-LD, it facilitates data interchange and reuse.

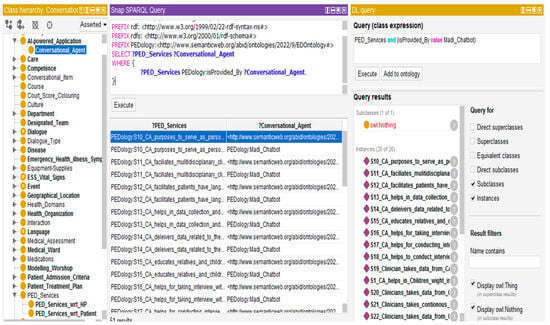

4.4. Using SPARQL and Description Logic (DL) Queries to Verify Ontology-Related Competence Questions (OCQs)

In this section, we used the SPARQL (https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-sparql-query/ (accessed on 12 June 2025)) query and the description logic (DL) (https://www.cs.ox.ac.uk/people/ian.horrocks/Publications/download/2014/KrSH14.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025) query plug-ins in Protégé 0.5 editor to verify the ontology metadata model with ontology-related competence questions (OCQs). Additionally, we aided in confirming that the ontological model contains sufficient information to address these inquiries about domain issues such as PED. Figure 6 displays the output of running the queries in the Protégé editor and provides an example of an OCQ using SPARQL and DL-Query. We loaded this ontology model into a knowledge graph (KG) (https://www.ontotext.com/knowledgehub/fundamentals/what-is-a-knowledge-graph/ (accessed on 10 June 2025)) database like Neo4j to enable ontology-driven application development and personalized information retrieval.

Figure 6.

Expected results verified through competency questions.

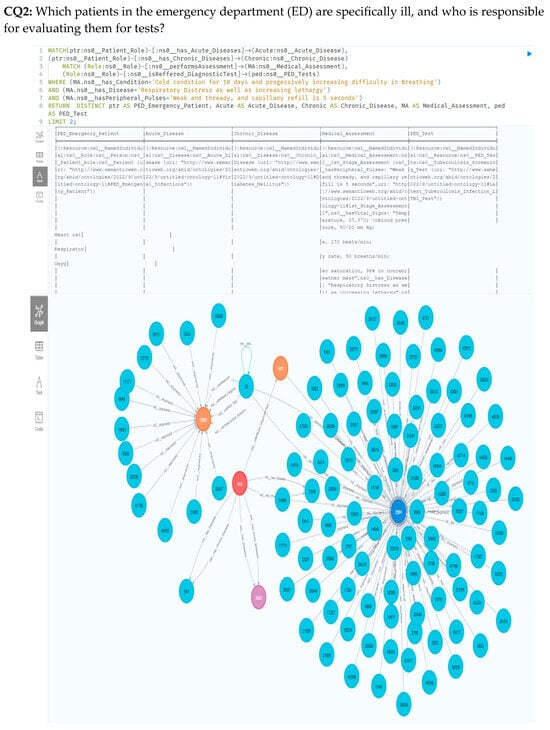

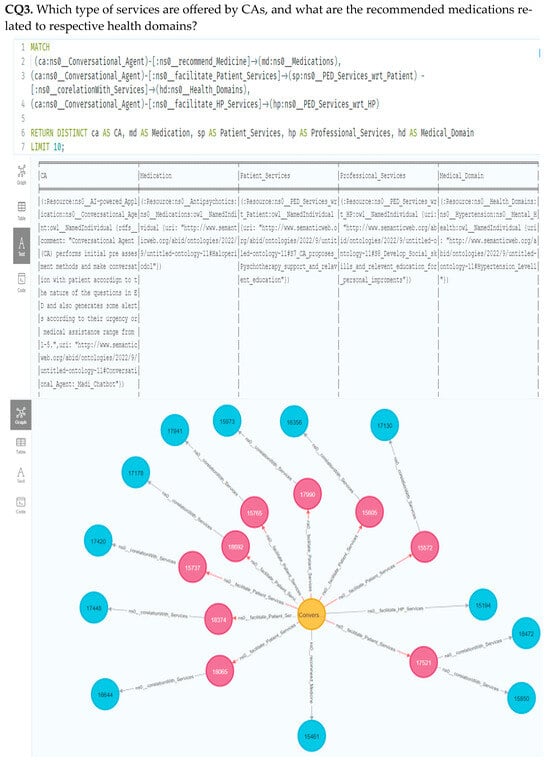

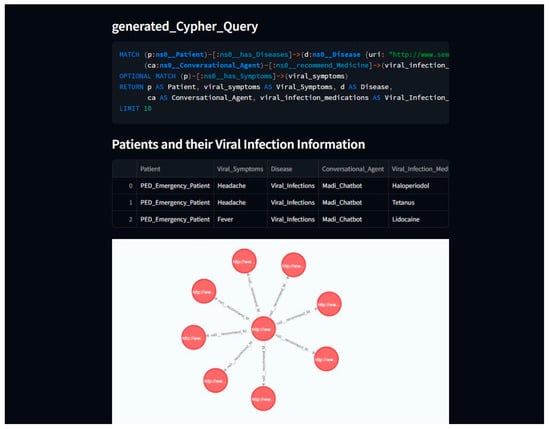

4.5. Using Cypher Queries to Retrieve Personalized Knowledge in Neo4j

RDF N-triples (https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf12-n-triples/ (accessed on 8 June 2025)) were stored by the authors using Neo4j, a KG (integrated knowledge repository). We imported the OntoM with RDF file extensions (e.g., filename.rdf) using the Neosemantics plug-in in the Neo4j (https://neo4j.com/labs/neosemantics/ (accessed on 8 June 2025)). This model is parsed into the Neo4j graph database, resulting from work based on 15,590 triples loaded and 15,590 parsed, showing the loaded model’s quality and consistency. It is also called the semi-automated approach of KGs, demonstrated in this paper (see Figure 7), a rule-based information retrieval result against CQ2, and (see Figure 8) retrieved results against CQ3.

Figure 7.

Structure of cypher query and acquired outcomes from PEDology model.

Figure 8.

PEDology model results and the structure of cypher query.

4.6. Testing with Domain Experts During Modeling Discussion

In this section, we delineated a holistic view of the ontological meta-model based on the case study and observations that thoroughly illustrated the PED discussion. We confirmed with domain experts related to the key concepts and their synergy with the discourse of ED in modeling discussion sessions. We also discussed the ontology development design methodology with technical experts and the strategy to develop a shareable ontology, inviting multi-stakeholders to facilitate knowledge-sharing on demand in an emergency. In this session, testing experts tried to test the ontology with OCQs and perform some ontology consistency tests when the ontology was inconsistent and incoherent. Some exceptions will come using the “OntoDebug” option in the ontology editor (e.g., Protégé version 5.6.0). OntoDebug is a free and open-source interactive ontology debugger plugin that resolves and repairs inconsistent and incoherent ontologies. This testing exercise also helped us receive feedback from domain experts.

4.7. Sequence Diagram of the Proposed Solution

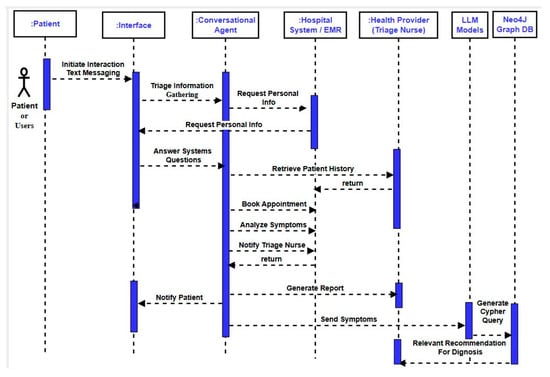

Figure 9 provides a sequential diagram illustrating the workflow of CAs and their interaction with a patient or relatives in an ED setting. It also illustrates how including LLMs helps HPs improve the information flow and provision during the diagnosis process in PED settings. The interaction flow is classified and broken down into different levels, including the patient (users), interface, conversational agent, hospital system or EMR, healthcare providers (e.g., triage nurse, etc.), large language models (LLMs), and a graph database (e.g., Neo4j):

Figure 9.

Sequence flow of the proposed solution of MediBot.

- 1.

- The Patient Initiates Interaction: First, patients or relatives initiate interactions using an interface, preferably in the text messaging mode. Although users can also prefer voice messaging, this is not discussed in this work and is a limitation of this work; the authors can extend this in future work.

- 2.

- Triage Information Gathering: Second, CAs initiate the question and answer session with patients or users and request the patient’s personal information, including name, age, and contact details.

- 3.

- The Patient Provides Personal Information: Third, patients provide the requested demographic information to the agent using text messaging.

- 4.

- Conversational Agent Analyzes Symptoms: Fourth, CAs perform multidisciplinary tasks such as analyzing symptoms, providing initial assessment, and facilitating patient scheduling doctor appointments for patients at the time of their arrival in EDs. CAs analyze the patient-reported symptoms by combining rule-based systems, machine learning algorithms, and natural language techniques. Similarly, CAs can ask some more questions for clarity to assess the urgency of the medical treatment in the waiting area. In addition, CAs schedule a virtual or in-person appointment with a healthcare provider through an electronic health record (EHR) or triage system.

- 5.

- Conversational Agent Notify Healthcare Worker: Fifth, CAs generate the signals after making an initial assessment based on question-and-answer sessions with patients, medical history, vital signs, and personal observations. These signaling phenomena highlight the severity of medical urgency within the long waiting queue structure in the waiting area. These signals are classified into red, blue, and green and forwarded to the triage for necessary actions. A team is allocated to take the patient into the emergency room without queue protocols. The red signal mentions a severe condition of the patient, the blue signal highlights some critical condition of the patient, and the green signal describes the routine checkup.

- 6.

- Conversational Agent Generates Report and Sends to Healthcare Worker: Sixth, CAs generate assessment reports and send them to the healthcare workers, especially the triage nurse, for further action. If the report mentions some critical signaling, then a reserve team of practitioners is ready to take the patient directly to the emergency room without obeying the queue structure.

4.8. MediBot: The Anatomy of the Proposed Solution

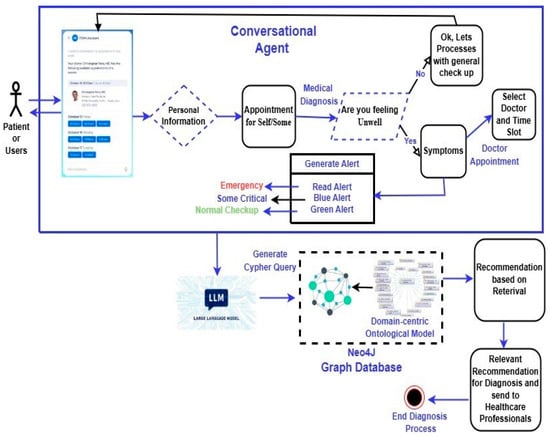

Figure 10 demonstrates the systematic workflow of CAs suggested in EDs, aiming to improve the information flow and provision to minimize the consultation time in the emergency healthcare unit. The proposed solution will facilitate the arrival of patients or relatives in the emergency unit. It initiates and requests to ask for essential and critical information related to the patient’s personal information, previous medical history, and current observations within the panic time for better initial assessment. It provokes and fosters the need for timely medical assistance procedures in the waiting area of the healthcare unit. In this work, the anatomy of the systematic workflow is categorized into various sections: (i) patient interaction, (ii) agent’s processing and decision-making, (iii) alert generation and notification, and (iv) diagnosis process and recommendation (see Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Systematic workflow of the proposed solution in PED setting.

- 1.

- Patient Interaction Phase: In this phase, patients initiate the interaction mode with CAs via texting or voice-activated devices. CAs request and collect relevant patient demographic information and other observational information during the panic or stroke. CAs inquire about patients’ symptoms using the question-and-answer method for initial assessment.

- 2.

- Conversational Agent and Decision-Making Phase: In this phase, CAs are responsible for performing symptom analysis and analyzing patients’ reported health conditions using a variety of data analysis methods, such as rule-based systems, machine learning algorithms, and natural language processing techniques. For an accurate assessment, CAs request additional information to assess patients’ conditions accurately. The initial assessment and recommendation target a potential diagnosis. They recommend a course of action that helps with self-care advice and scheduling a virtual or in-person consultation with suitable time slots with a healthcare provider in healthcare settings.

- 3.

- Alert Generation and Notification Phase: This phase is crucial based on the severity of the patient’s health conditions. CAs generate an appropriate alert and forward it to the triage system in the ED unit for necessary actions and evaluation to rescue patients in severe health conditions and needing prior medical attention.

- 4.

- Diagnosis Process and Recommendation Phase: In this phase, CAs forward the symptom reports to LLMs, which intelligently generate a customized cypher query to retrieve relevant information from the Neo4j graph database. The graph database stores the domain-centric ontological models representing medical knowledge and relationships between entities and properties. LLMs help retrieve relevant information from the database using a sophisticated query, allowing HPs to make potential diagnoses and treatment recommendations.

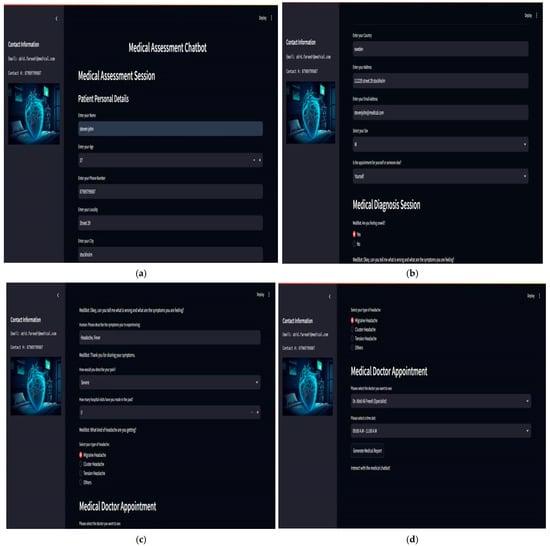

4.9. Prototyping: Physical Instantiation Artifact

Figure 11 demonstrates different stages of the prototyping (https://github.com/Shehzad05/medical-chat-bot (accessed on 5 June 2025)) interface to showcase the narrative of this research work, how CAs as assistive technologies elevate the traditional working pattern and foster therapeutic working alliance and trustful collaboration between multidisciplinary HPs in EDs of the healthcare organization. It also emphasizes transforming from the “As-Is” situation to the “To-Be” situation to incorporate innovative AI-powered solutions to create value in the healthcare sector. The physical instantiation artifact followed the working flow of Figure 11 and Figure 12 as reference points. The stages are categorized into five sections: (i) medical assessment section, (ii) medical diagnosis section, (iii) medical doctor appointment, (iv) generate initial assessment report, (v) facilitation to the healthcare practitioners empowering LLMs that is forwarded to the healthcare worker (e.g., triage nurse, etc.) for further necessary actions and alerting the medical team to bring the patient who needs urgent medical assistance in the waiting area in ED.

- 1.

- Medical Assessment Section: This section covers patients’ (users) demographic information, such as name, age, personal contact information, etc. For technical considerations, this prototype follows front-end technologies such as CSS for styling; back-end technologies are also good, and CAs likely communicate with a back-end server to process user input, perform medical assessment, and provide recommendations. For data storage, we used a light database to collect and store the patient information for future reference or analysis. Overall, the interface offers a user-friendly way for patients (users) to interact with a CA for medical assessment, collecting essential information to facilitate patients’ in-person or virtual consultation to improve the information flow procedures and minimize the fatigue and stress traumas in waiting areas of EDs.

- 2.

- Medical Diagnosis Section: This section highlights one of the core parts of the discussion. It explains the procedure, how CA initiates and interacts with the patients (users), and collects necessary information, such as previous hospital visit history, observational symptoms, and patient pain severity, using question-answering exercises. It also assesses and initially evaluates the urgency of medical assistance. It acts as a helping hand, provides a virtual medical consultation, and supports HPs and medical workers, especially during peak ED hours in EDs.

- 3.

- Medical Doctor Appointment: Another salient feature of this work is that it provides a medical doctor appointment with specialization and available time slots. It also features cancellation at any time at the patient’s convenience.

- 4.

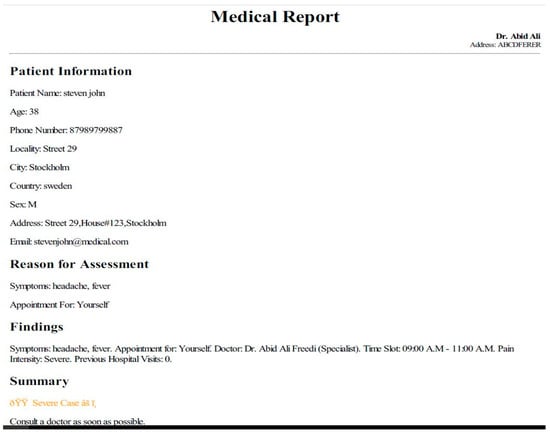

- Generate Initial Assess Report: This section breaks down reports forwarded to healthcare workers, especially triage nurses. It generates signaling to prompt the patient’s medical condition and status, alarming the urgency of medical assistance on a prior basis. This automatically generated report covers the patient’s demographic information, the reason for assessment based on prior question-answering sessions, initial findings, and assessment. It also sends the summary with signaling signs.

- 5.

- Facilitation to the Healthcare Practitioners Empowering LLMs: This section also benefits HPs and medical workers, especially in patient–doctor meetings. Here, CAs leverage LLMs to help generate potential diagnosis options, treatment recommendations, and medication advice for HPs. CAs generate automated queries to retrieve the relevant information from the knowledge graphs (KGs) stored in graph databases like Neo4j. They also leverage supplementary information using LLMs to provide a suitable choice to HPs during their consultations with patient–doctor appointments.

Overall, the contribution of this work is twofold: first to patients and then to healthcare professionals. This assistive technology, like CAs, allows patients (users) to avoid long waiting times, normalizing frustration levels, doctors’ appointments, and further medical assistance and advice without communication with HP. CAs also enable the fostering of information flow and provision within EDs. Simultaneously, these solutions act as helping hands to support HPs and practitioners in reducing workload and making them more efficient and vigilant during consultation. They also improve their working skills and learning, and therapeutic procedures during consultation.

Figure 11.

Blueprints of the prototype (medical bot). The blueprints mentioned above are listed as follows: (a) description of patient information details; (b) description of medical diagnosis assessment with patient details; (c) description of medical doctor patient diagnosis and assessment session; (d) description of medical doctor appointment and its confirmation.

Figure 12.

Prototyping (physical instantiation artifact) of the proposed solution, Madibot.

4.10. Prototyping Evaluation

In this research contribution, we followed a customized DSR evaluation strategy, Purely Technical Artifact proposed by the work of Venable et al. (2016) [64], and different evaluation methods to evaluate the prototype, such as scenario-based evaluation [65], usability inspection [66], expert reviews [67], and modeling workshop sessions [51].

4.10.1. Evaluation Strategy

In this research work, we followed the proposed strategy by Venable et al. (2016) [64] because the artifact is purely technical (no social aspects). Future work will incorporate empirical or pilot studies. We utilized non-empirical artificial evaluation, which is nearly always positivist. The artificial evaluation strategy includes laboratory experiments, simulations, criteria-based analysis and theoretical arguments, and mathematical proofs [64].

4.10.2. Scenario-Based Evaluation

In the scenario-based evaluation process, we established and wrote a scenario from the case research (see Section 3.1). Scenario: A patient has been diagnosed with a viral infection. Viral infections are typically caused by influenza, the common cold, or even more serious ones like COVID-19. Let us assume the patient suffers from a common viral infection like the flu (influenza). We also tested this scenario in the laboratory. The goal was to assess the effectiveness of ontology-driven LLMs in supporting HPs in providing timely and accurate consultations. To evaluate the LLM’s performance, we employed a scenario-based approach following specific steps (see Figure 13):

Figure 13.

Scenario-based evaluation of the proposed solution, Madibot.

- 1.

- Construction of Ontological Model: The ontological model served as a backbone of the system, facilitating medical knowledge in a structured form and efficient knowledge retrieval, improving the clinical decision-making process, and enhancing LLMs’ performance.

- 2.

- Knowledge base Querying: Using knowledge representation language like description logic (DL) and SPARQL, we queried the ontological model to retrieve relevant information.

- 3.

- LLM Interaction: The LLM presented the initial assessment report and was tasked with providing appropriate advice or recommendations verified from the knowledge base (ontological model).

- 4.

- Performance Evaluation: The LLM’s responses were evaluated against the gold standard, which could be domain experts’ opinions or established clinical guidelines.

4.10.3. Expert Review

In the expert review evaluation process, we followed the excellent practices proposed by Molich et al., 1990 [67], and conducted technical sessions (unofficial) with industry subject matter experts, incredibly generative AI, and machine learning experts to assess the prototype for domain-specific requirements, relevance, and usability.

The experts gave a high-level overview of the prototype’s goals and functionalities to target this research’s narrative and align it with industry standards, functionality, and user needs.

4.11. Modeling Workshop Sessions

In this research, we followed specific steps Fareedi and Tarasov (2011) [51] proposed during the modeling workshop sessions. During the workshops, we presented the holistic view of the ontological model (data) model design that illustrates how domain knowledge is mapped and how user requirements are well elaborated. We developed some CQs to verify the knowledge base and overall application response against queries (written in SPARQL, and LLMs will generate automated cypher queries, which are responsible for fetching the data from the graph database, like Neo4j). This domain-centric information retrieval helps HPs during their consultation and overall in the learning process. The development of the domain-centric prototype is evident in justifying the proof of concept and how CAs can revolutionize in some way to improve the information flow and provision in EDs and engage patients at arrival time in EDs. These solutions also help HPs as assistive technologies and normalize the workload of healthcare workers, especially in peak hours of EDs in healthcare organizations.

5. Discussion

The rise in AI-powered healthcare technologies like CAs, especially in environments like emergency departments (EDs), presents a significant advancement in leveraging AI to enhance patient care and alleviate burdens on HPs [10]. This research proposes an ontology-driven framework to optimize the collaboration between CAs, HPs, patients, and family members within the PED context [14]. In addition, this research evaluates the viability of an ontology-driven framework leveraging LLMs supporting CAs, the effectiveness of CAs, and their use in collaborative settings, particularly EDs. It highlights how these new technologies, like CAs, contribute to better patient information flows and information provision (IP) and facilitate HPs during peak ED hours. This research focused on the questions narrated in Section 1: How does the proposed ontology-driven framework support CA design, which helps to induce therapeutic working alliances and develop trustful collaboration between multi-stakeholders using shared knowledge with LLMs capabilities within EDs?

In addition to the SHAICF and PEDology metadata model, the results discussed in Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 provide well-qualified evidence to address the problems mentioned earlier and significantly contribute to enhancing processes in the PED context. They look at the views of several stakeholders, including patients, HPs, and experiences, and the advantages of having CAs on site, particularly in an emergency department setting.

This section also covers the risks and challenges CAs present in the healthcare sector. The advantages that end users believe they have gained are the primary factors determining how successful it is to integrate CAs into the healthcare sector. Simultaneously, HPs and domain specialists are keen to integrate CAs into ED facilities to accomplish specific goals and enhance patient workflow processes. Through the systematic development of semantic artifacts, such as domain ontologies and knowledge models, the framework facilitates the dissemination of personalized, contextual, and domain-expert knowledge to support collaborative decision-making and task execution [68].

One of the key contributions of this research lies in its emphasis on fostering therapeutic working alliances and trustful collaborations between multi-stakeholders using generative AI advancements within the context of EDs [22]. Integration of AI-powered CAs with an ontology-based methodology, the framework leveraging LLMs, facilitates effective knowledge exchange and learning capabilities, ultimately improving stakeholder communication and engagement. In high-stress settings like PEDs, efficient provider teamwork is essential to provide patients with high-quality treatment [9]. The stress levels and coping mechanisms of clinicians have a direct effect on how well they function, especially during surgeries. Therefore, addressing the causes of stress and using HP’s practical coping techniques are crucial to providing the best possible patient care. According to the vision of Lanham et al. (2009) [69], strengthening the bond between HPs and putting in place training initiatives can equip healthcare workers to promote interdependence and raise quality patient treatment in the ED.

Proactive and innovative human-centered solutions assist HPs and support clinical workers in high-stress settings, especially in the ED. These technologies streamline healthcare providers’ interactions, facilitating more effective care delivery. These technological solutions, like CAs, help to streamline HPs and providers and improve their interactions with machines to support quality care delivery in the peak time of EDs. Furthermore, CAs help patients manage their personalized care. These technological landscapes enable patients to take charge of their health with customized features to improve their lifestyle. CAs also support HPs and may enhance the efficacy, safety, efficiency, and quality of care using electronic medical records. CAs also help to avoid unwanted ED visits and overcrowding situations, offering remote treatment alternatives and monitoring. CAs support a coordinated, service systems-oriented approach to healthcare providers and aim to improve well-being, chronic illness management, disease prevention, and improved communication via communication channels (e.g., SMS, email, etc.).

In the literature, published research mentions some significant facts that, on average, 65% (SD = 13.24) of respondents agree (or somewhat disagree) that health CAs are value-added and a game-changer in improving patient-centric treatment in a hospital setting, whereas 17% (SD = 6.12) disagree (or somewhat disagree) with the potential advantages of health CAs [70]. Additionally, intelligent CAs contribute to fostering and assisting HPs in collaborating on crucial and repetitive tasks, including self-management, education, training, diagnosis, counseling, and screening.

From the patient’s perspective, CAs are the enabling tools for improving individuals’ healthcare experience in various application contexts. First, by interactive questioning, CAs help patients educate, suggest their diseases, and follow symptoms for self-diagnosis and personalized treatment. Furthermore, CAs provide confidence and enhance trust in patients acquiring comprehensive medical histories. CAs empower HPs and clinicians to make better judgments regarding their treatment and support better decision-making in critical health situations.

CAs, as assistant tools, serve as a digital doctor and suggest pharmaceutical advice based on the patient’s drug consumption and their needs in their daily routine. CAs coordinate triage and prioritize patients’ urgency for medical assistance in EDs and also provide care and rich mental therapy support to individuals in panic situations. In addition, CAs expedite administrative repetitive tasks, including taking vital signs, placing food orders for patients, and improving their overall hospital experience.

Above all, CAs are primarily employed in healthcare settings to ensure that information flows and is provided seamlessly across the healthcare system to improve patient treatment’s effectiveness and efficiency. Patients place a high value on natural, concise, and precise communication, which is essential to CA efficacy. Patients who are placed in restraints while in the hospital after an ED visit frequently request that healthcare professionals communicate and comprehend their choice to use restraints better. Furthermore, many patients and those who assist them in emergency departments need help understanding medical jargon, making them feel more stressed and like they are losing control [15].

From the standpoint of healthcare professionals, CAs play a crucial role in supporting HPs across various application scenarios:

- 1.

- AI-powered CAs, as an assistive technology, are invaluable tools used in alliance with HPs to enhance diagnostic accuracy and support decision-making by providing reliable diagnostic assistance.

- 2.

- CAs contribute significantly to interpreting clinical images such as computer tomography and X-ray, enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

- 3.

- AI-powered CAs offer multiple functionalities, such as medical assistants, providing seamless access to critical patient information, including medical history, updated diagnoses, and different symptoms, such as allergies. They support physicians in making informed decisions and enable regular monitoring of disease progression, particularly in Emergency Departments (EDs). CAs help doctors prepare for surgery in the operating room by giving vital information on the patient’s medical history and current blood samples.

- 4.

- These assisting tools serve as interactive knowledge bases that let users ask questions about new treatments and illnesses that are currently effective and encourage HPs to keep learning and improving their skills.

- 5.

- CAs also help physicians accomplish enormous documentation duties, and CAs lessen the workload associated with documentation activities. This support improves healthcare delivery’s overall efficacy and efficiency by assisting doctors in devoting more time to important patient care tasks and providing invaluable support to enhance patient outcomes.

ED reveals that most HPs struggle with typical patients suffering from various ailments for seamless communication and efficient diagnosis. When many related diseases and symptoms are present, it can be challenging for HPs to address the core concerns of these patients successfully. HPs wish to incorporate mediating tools like CAs as co-worker alliances to enhance value creation in EDs during peak ED hours [15]. This research’s proposed ontology-driven approach handles several issues, providing an intelligent knowledge base to address overcrowding and resource allocation in healthcare systems, especially ED [16]. The framework develops several healthcare services using LLMs, including patient consultation and monitoring service coordination easier by streamlining patient processes, lowering administrative costs on HPs, and organizing domain knowledge and contextual data into structured ontologies [11]. CAs can further optimize resource utilization and improve patient experiences by offering customized support and suggestions by integrating conversational ontologies and service-oriented semantic artifacts [12].

Sweeney et al. (2021) [71] emphasize some critical challenges and hurdles linked with CA usage and their implementation in hospital settings. These challenges are well-categorized: First, the statistics show that almost “86%” of respondents participated in the survey and said that including CAs in healthcare settings caused difficulties in understanding or expressing human emotions. Second, over “77%” of respondents realize that including digital tools is an added value to performing health-related services in terms of satisfying patient requests on demand and indicating potential deficiencies in responsiveness. Furthermore, almost “73%” of participants believe and recommend that CAs can interact with patients effectively, especially in panic situations. These characteristics also establish essential responsibilities concerning the reliability and efficacy of these methods in different clinical contexts for diagnosing and treating chronic diseases. Healthcare providers worry about patient data security after working in health institutions because more than “59%” of participants polled expressed their reservations about patient data confidentiality and privacy issues, which are noticeable.

Reis et al. (2020) [16] mention that domain-specific constraints lead to the severe challenges associated with CA deployment in healthcare settings. These limitations include preparing for regret resulting from errors or malfunctions in the CA, mainly if the recommendations are faulty due to mistakes or erroneous inputs. According to the healthcare stakeholders’ and end-users’ judgments, handling private medical data is very tricky and risky, which impedes the adoption of CAs. As technology constraints, privacy issues, and user attitudes become more apparent in ED settings, it is critical to integrate CAs into the healthcare environment to optimize healthcare operations and efficacy.

As per technology advancement, semantic-oriented (ontology-driven) and generative AI (LLM-powered) paradigms enable and foster domain-centric healthcare services and their development. The deployment procedures of CAs mention noticeable ethical and practical data privacy and security challenges in healthcare contexts. CAs process patient-related critical information that must comply with regulations, including GDPR and HIPAA, in real-time scenarios [71]. Improving decision-making, transparency, and accountability in AI-assisted decisions is crucial, particularly when CAs affect clinical reasoning or patient triage processes. Moreover, large language models (LLMs) are used for data pruning and removing redundant, irrelevant, or low-value data points to streamline training, reduce costs, and improve data model accuracy; and resolving language biases that can lead to unequal treatment or misleading recommendations if not validated adequately against domain ontologies and expert-reviewed datasets. Therefore, there is a need to establish ethical safeguards such as bias detection, explainability features, and ongoing human oversight as salient features in AI-driven healthcare.

Barwick et al. (2020) [21] mention that customized treatments are still valuable for achieving quality results in the healthcare domain. For this purpose, this research depicts the evaluation process of the proposed ontological framework through CQs and accurately retrieves results through information retrieval (IR) procedures, demonstrating its potential efficacy in practical settings. This research also advocates the proposed methodology for developing a service-oriented ontological sharing framework, which is helpful in flexibility and scalability in various healthcare environments, especially integrating with legacy HISs and supporting multidisciplinary teams within the PED settings. Of course, the adaptation is a crucial process and addressing specific gaps in pediatric readiness, clinical practice, and information dissemination related to various tasks, especially eating disorders in EDs.

Ultimately, we emphasized ontology-driven methodology for developing a service-oriented framework (e.g., SHAICF) harnessing LLMs’ capabilities in a human–computer interaction context. We mentioned value-added contributions and their potential for improving information sharing and provision inside healthcare systems and promoting the human–AI cooperation and collaboration phenomenon, particularly in critical care environments, especially in PED. Through AI-driven systems such as CAs and the semantic technology landscape, most organizations have experienced exponential improvements in communication, optimizing workflow processes, and providing quality patient care efficiently and effectively. Hamounda et al. (2016) [18] suggest that more research, investigation, and validation in real-world contexts are needed to evaluate the impact and viability of implementing such frameworks.

6. Conclusions

This research demonstrates interaction patterns between different healthcare stakeholders and recommends tripartite CAs, patients, or family members, and HPs as part of a structured cooperation process. It also emphasizes the role of CAs harnessing LLMs’ capabilities as a mediating instrument or agent. Here, the service-oriented collaborative framework is based on the shareable ontology (a formal ontological metadata model), showcasing the declarative knowledge of PED. It also provides a platform to serve the maximum health-related services CAs offer patients upon arrival. It helps HPs perform crucial collaborative tasks on demand to avoid overcrowding situations during peak hours in the EDs. We followed a tailored agile OEM approach rooted in the DSRM approach using ODPs to build the semantic artifacts of a formal shareable, collaborative model (PEDology), which helps to develop CAs containing explicit services for performing some collaborative tasks with HPs. The proposed framework explains a systematic way to create service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework (SHAICF) working pathways. It highlights how HPs can be facilitated through co-working alliance development and create co-working value using CAs in EDs. The proposed work follows an ontology-driven approach to transform machine-readable information into a structured form and store it in knowledge graphs (KGs) (an integrated knowledge repository). It encourages developers to build human-centered AI-based systems like CAs or services related to the specific domain and context to deal with PED overcrowding situations. The ontology-driven approach helps to develop IS with LLM capabilities in healthcare organizations to automate their crucial tasks and improve processes using information-sharing strategies and creating synergy between different communication channels within the health unit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.F. and Z.A.; data curation, A.A.F. and Z.A.; data gathering and investigation, A.A.F. and Z.A.; methodology, A.A.F. and M.I.; project administration, S.G. and H.N.; supervision, A.G. and H.N.; software, A.A.F., S.A. and M.I.; validation, A.A.F., S.A. and M.I.; writing—original draft, A.A.F.; writing—review editing, A.A.F. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We would like to clarify that our research does not involve real human participants or the use of actual patient data. Instead, we employed fictitious (dummy) data solely for the purpose of demonstrating the technical feasibility and proof of concept of our proposed approach. Our study focuses on semantic techniques to address challenges in data integration and interoperability within clinical systems. The data used in our experiments was synthetically generated to simulate realistic healthcare scenarios without compromising privacy or involving real individuals. Accordingly, the ethical approval is exempt.

Informed Consent Statement

As mentioned above, our research does not involve real human participants or the use of actual patient data. As such, informed consent was not required, and no actual participants were enrolled in the study. Accordingly, there is no signed consent form to submit. We hope this clarifies the nature of the data used in our work.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shehzad Ahmed is employed by Tafsol Technologies. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

List of acronyms:

| Acronym | Meaning |

| CAs | Conversational agents |

| LLMs | Large language models |

| ED | Emergency department |

| SHAICF | Service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework |

| OEM | Ontology engineering methodology |

| DSRM | Design science research method |

| PED | Pediatric emergency department |

| PEDology | Ontological metadata model PED |

| KT | Knowledge translation |

| ODPs | Ontology design patterns |

| Convology | Conversational ontology |

| SO | Service ontology |

| RO | Resource ontology |

| PO | Personalized ontology |

| DO | Disease ontology |

| KMs | Knowledge models |

| DMs | Domain models |

| CM | Context model |

| RM | Role model |

| CompM | Competencies model |

| KGs | Knowledge graphs |

References

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Li, D.; Raymond, L.R. Generative AI at Work; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]