Enriching Human–AI Collaboration: The Ontological Service Framework Leveraging Large Language Models for Value Creation in Conversational AI

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conversational Agents in Digital Health

2.2. Conversational Agents for Patient Empowerment

2.3. Applied Ontologies in Human–AI Collaboration and Value Creation

2.4. Ontology-Driven Frameworks and Large Language Models

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study: The Karolinska University Hospital

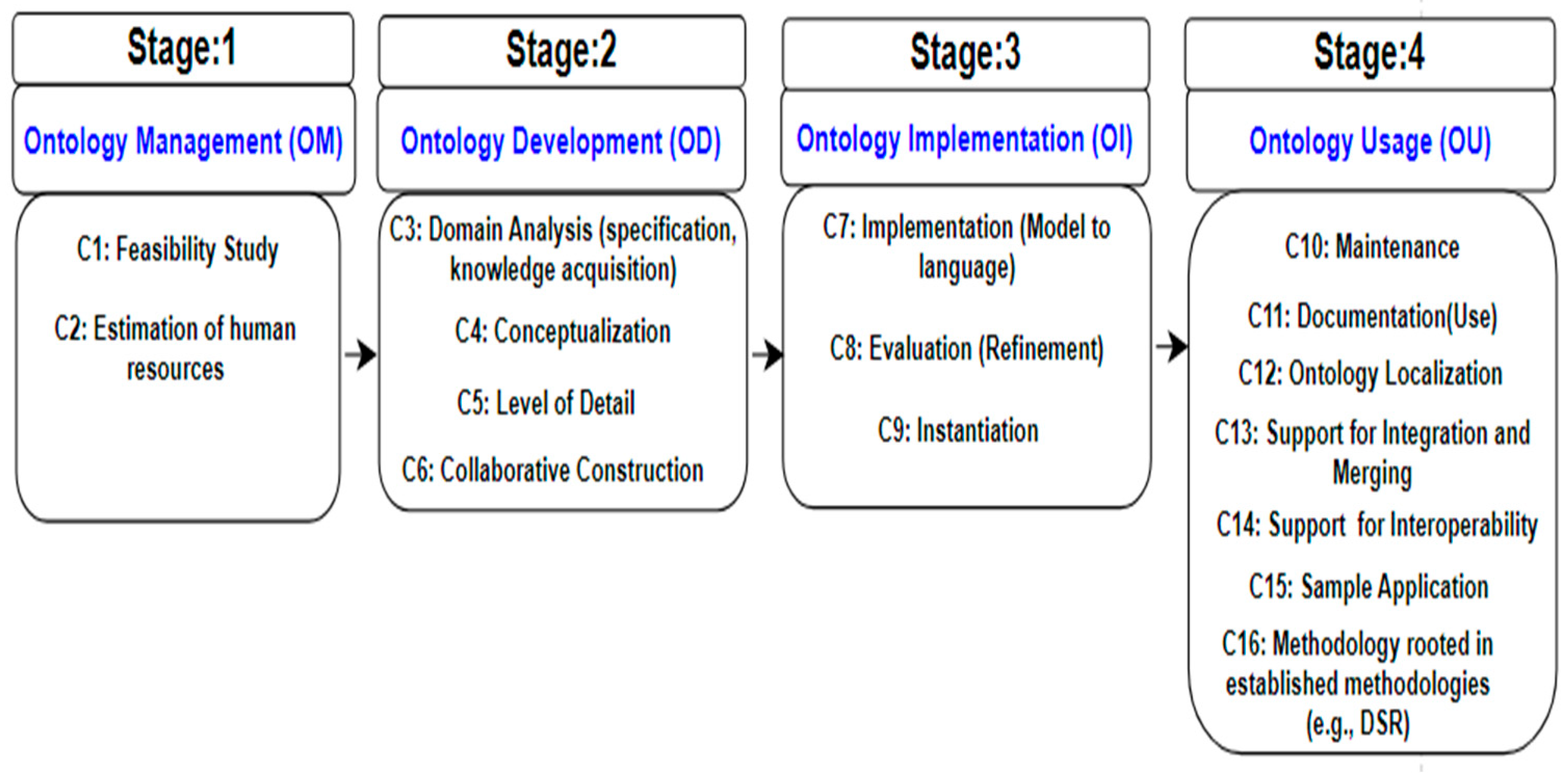

3.2. A Heavy-Weight Methodology for Shareable Ontology Engineering

- 1.

- Stage 1 explains the feasibility and viability of the research and defines the cost estimation of human resource assessment. Drawing on the knowledge and expertise of knowledge engineers, software engineers, ontologists, qualified domain specialists, and a technical writer for the documentation, this describes the team’s skills, experience, and size needs.

- 2.

- Stage 2 covers the amount of depth, conceptualization, collaborative building, and domain analysis (specification and knowledge acquisition (KA)). Domain analysis must include advice about a specific domain and require many resources. Extracting the maximum information from the domain experts is a challenging task, so it is essential to utilize KA techniques such as modeling workshops and seminars to better understand the ontologies’ terminologies and core parts for team members. The conceptualization phase ensures that the suggested methodology includes or supports the conceptualization activities. Does the methodology include information on methods, and what do they entail? Furthermore, in the collaborative construction, various sub-ontologies are interlinked and aligned using ODPs within seed ontology (a federated ontology) related to the domain, such as PED.

- 3.

- Stage 3 describes how to put the shared ontology and model into practice, transform it into a conceptual ontology model to create a machine-readable ontology, and represent the knowledge in various formats for data rendering (e.g., RDF/XML (https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-syntax-grammar/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)), OWL/XML (https://www.w3.org/TR/owl-xmlsyntax/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)), Turtle (https://www.w3.org/2007/OWL/wiki/PrimerExampleTurtle (accessed on 20 June 2025)), and JSON-LD (https://www.w3.org/TR/json-ld11/ (accessed on 20 June 2025))). This step also specifies the evaluation component, which calls for the evaluator to use appropriate instantiation techniques and procedures while also improving their understanding of the ontology and installation.

- 4.

- Stage 4 serves for maintenance, where applied ontologies and keeping documentation with versions continuously face the evolution challenge. This phase also ensures that the developed ontology is constructed in a natural language that supports the localization concept. Furthermore, diverse applied ontologies and heterogeneous knowledge models are integrated, interlinked, and consolidated into a unified seed ontology (a federated ontology) using this systematic, rigorous procedure, enabling interoperability and facilitating seamless integration into the planned project.

4. Results: Implementation and Testing

4.1. Service-Oriented Human–AI Collaborative Framework (SHAICF)

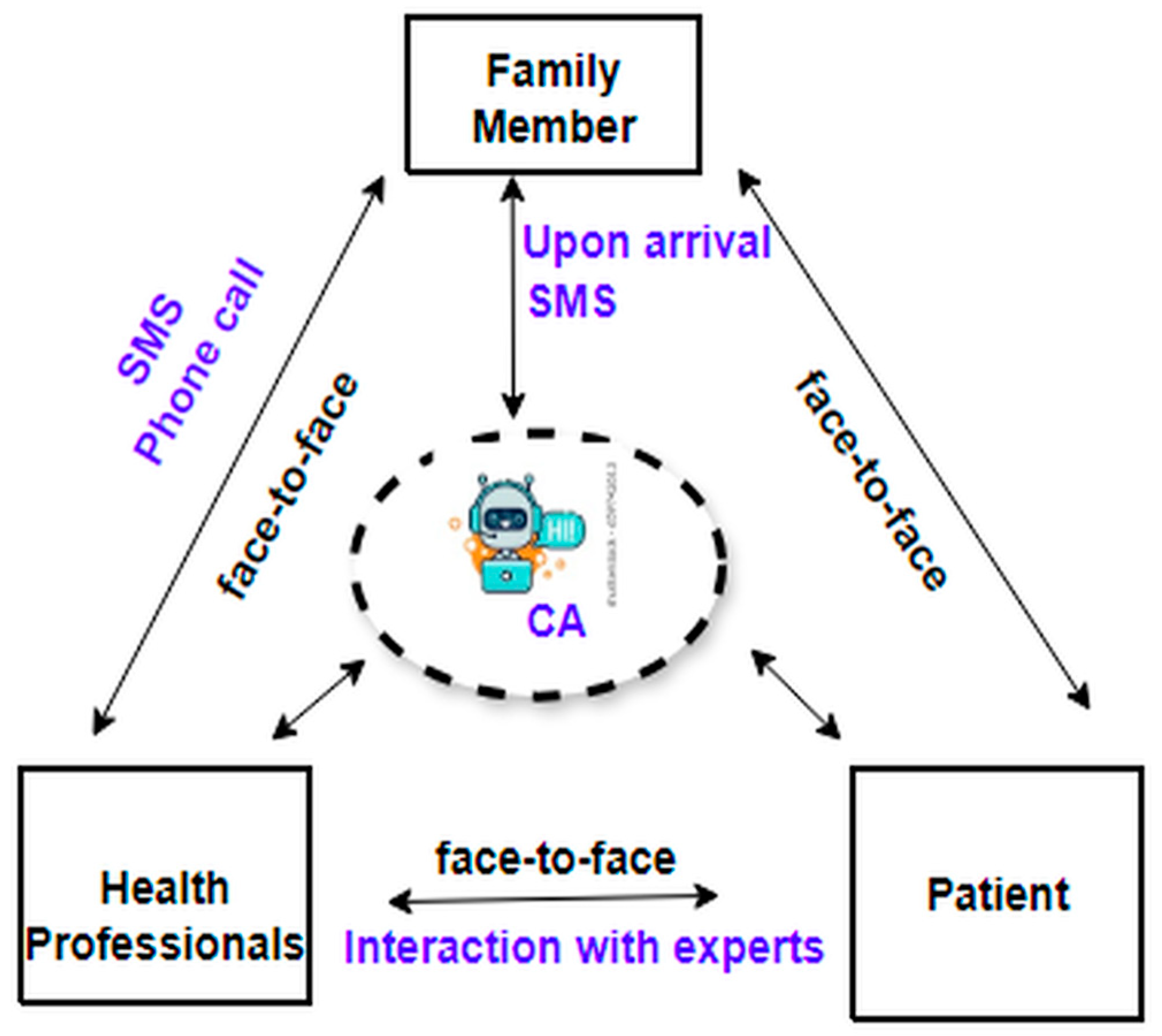

4.2. Conversational Agents and Healthcare Professionals Co-Working Alliance

4.3. Ontological Metadata Model of Pediatric Emergency Department (PEDology)

4.4. Using SPARQL and Description Logic (DL) Queries to Verify Ontology-Related Competence Questions (OCQs)

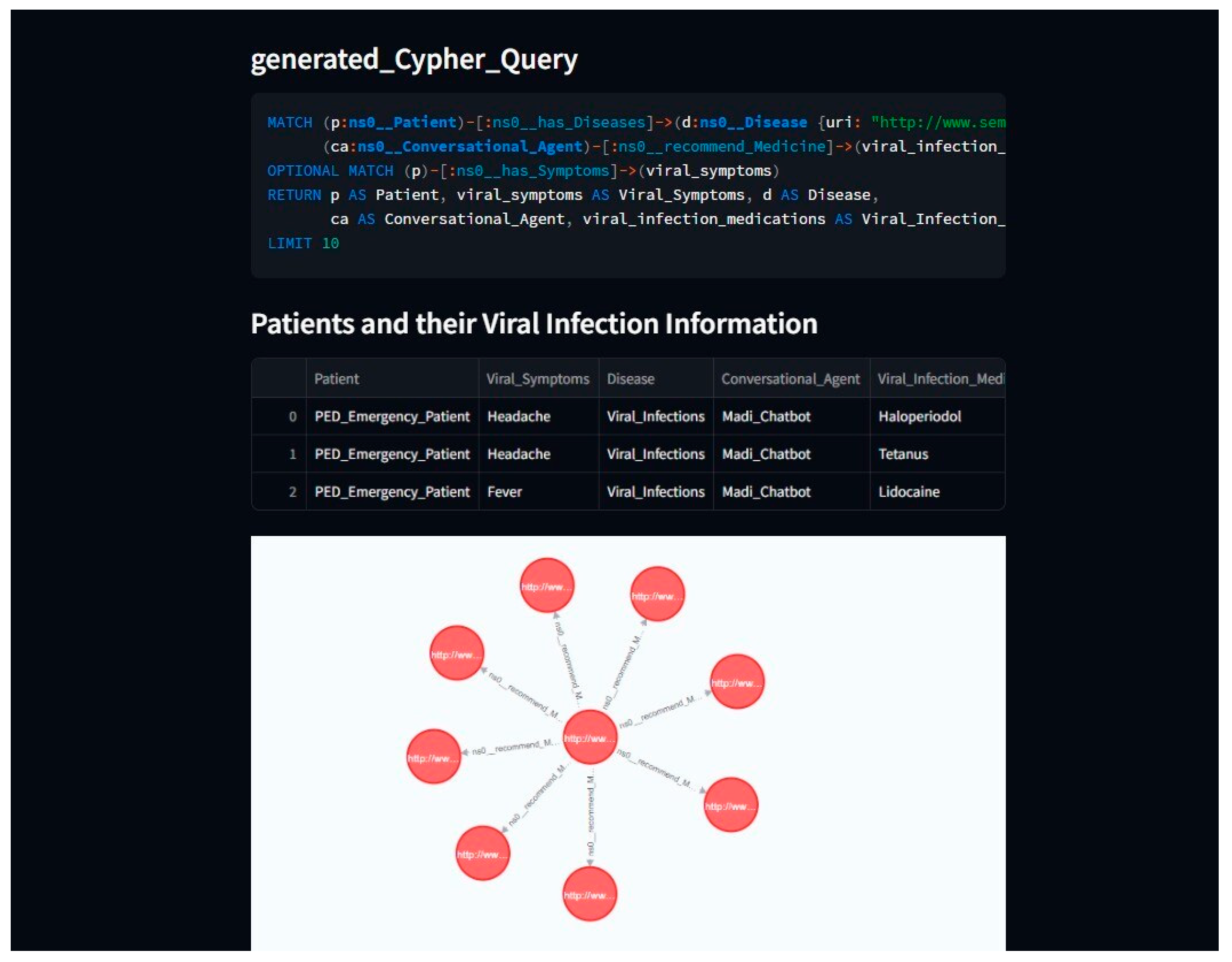

4.5. Using Cypher Queries to Retrieve Personalized Knowledge in Neo4j

4.6. Testing with Domain Experts During Modeling Discussion

4.7. Sequence Diagram of the Proposed Solution

- 1.

- The Patient Initiates Interaction: First, patients or relatives initiate interactions using an interface, preferably in the text messaging mode. Although users can also prefer voice messaging, this is not discussed in this work and is a limitation of this work; the authors can extend this in future work.

- 2.

- Triage Information Gathering: Second, CAs initiate the question and answer session with patients or users and request the patient’s personal information, including name, age, and contact details.

- 3.

- The Patient Provides Personal Information: Third, patients provide the requested demographic information to the agent using text messaging.

- 4.

- Conversational Agent Analyzes Symptoms: Fourth, CAs perform multidisciplinary tasks such as analyzing symptoms, providing initial assessment, and facilitating patient scheduling doctor appointments for patients at the time of their arrival in EDs. CAs analyze the patient-reported symptoms by combining rule-based systems, machine learning algorithms, and natural language techniques. Similarly, CAs can ask some more questions for clarity to assess the urgency of the medical treatment in the waiting area. In addition, CAs schedule a virtual or in-person appointment with a healthcare provider through an electronic health record (EHR) or triage system.

- 5.

- Conversational Agent Notify Healthcare Worker: Fifth, CAs generate the signals after making an initial assessment based on question-and-answer sessions with patients, medical history, vital signs, and personal observations. These signaling phenomena highlight the severity of medical urgency within the long waiting queue structure in the waiting area. These signals are classified into red, blue, and green and forwarded to the triage for necessary actions. A team is allocated to take the patient into the emergency room without queue protocols. The red signal mentions a severe condition of the patient, the blue signal highlights some critical condition of the patient, and the green signal describes the routine checkup.

- 6.

- Conversational Agent Generates Report and Sends to Healthcare Worker: Sixth, CAs generate assessment reports and send them to the healthcare workers, especially the triage nurse, for further action. If the report mentions some critical signaling, then a reserve team of practitioners is ready to take the patient directly to the emergency room without obeying the queue structure.

4.8. MediBot: The Anatomy of the Proposed Solution

- 1.

- Patient Interaction Phase: In this phase, patients initiate the interaction mode with CAs via texting or voice-activated devices. CAs request and collect relevant patient demographic information and other observational information during the panic or stroke. CAs inquire about patients’ symptoms using the question-and-answer method for initial assessment.

- 2.

- Conversational Agent and Decision-Making Phase: In this phase, CAs are responsible for performing symptom analysis and analyzing patients’ reported health conditions using a variety of data analysis methods, such as rule-based systems, machine learning algorithms, and natural language processing techniques. For an accurate assessment, CAs request additional information to assess patients’ conditions accurately. The initial assessment and recommendation target a potential diagnosis. They recommend a course of action that helps with self-care advice and scheduling a virtual or in-person consultation with suitable time slots with a healthcare provider in healthcare settings.

- 3.

- Alert Generation and Notification Phase: This phase is crucial based on the severity of the patient’s health conditions. CAs generate an appropriate alert and forward it to the triage system in the ED unit for necessary actions and evaluation to rescue patients in severe health conditions and needing prior medical attention.

- 4.

- Diagnosis Process and Recommendation Phase: In this phase, CAs forward the symptom reports to LLMs, which intelligently generate a customized cypher query to retrieve relevant information from the Neo4j graph database. The graph database stores the domain-centric ontological models representing medical knowledge and relationships between entities and properties. LLMs help retrieve relevant information from the database using a sophisticated query, allowing HPs to make potential diagnoses and treatment recommendations.

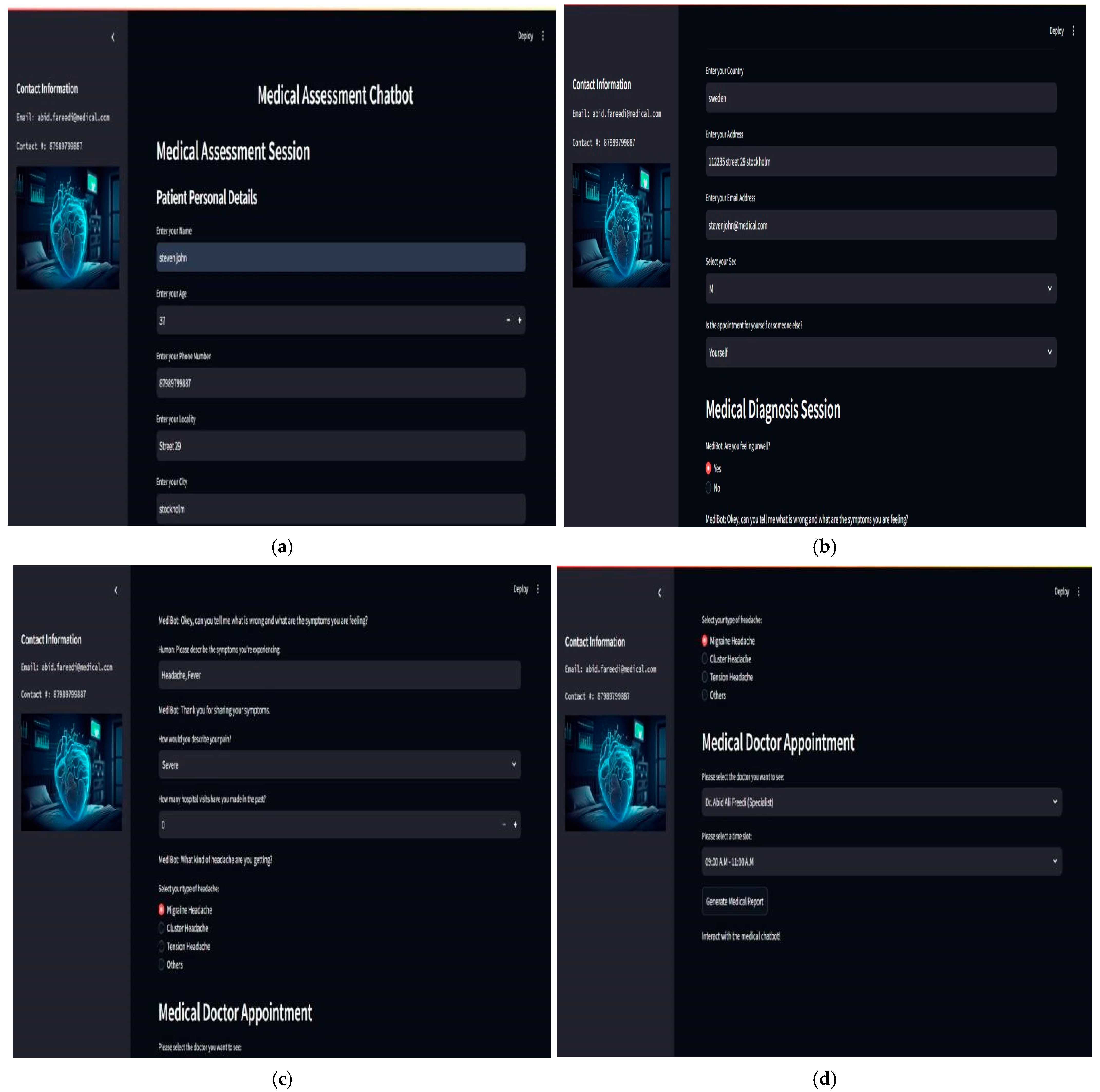

4.9. Prototyping: Physical Instantiation Artifact

- 1.

- Medical Assessment Section: This section covers patients’ (users) demographic information, such as name, age, personal contact information, etc. For technical considerations, this prototype follows front-end technologies such as CSS for styling; back-end technologies are also good, and CAs likely communicate with a back-end server to process user input, perform medical assessment, and provide recommendations. For data storage, we used a light database to collect and store the patient information for future reference or analysis. Overall, the interface offers a user-friendly way for patients (users) to interact with a CA for medical assessment, collecting essential information to facilitate patients’ in-person or virtual consultation to improve the information flow procedures and minimize the fatigue and stress traumas in waiting areas of EDs.

- 2.

- Medical Diagnosis Section: This section highlights one of the core parts of the discussion. It explains the procedure, how CA initiates and interacts with the patients (users), and collects necessary information, such as previous hospital visit history, observational symptoms, and patient pain severity, using question-answering exercises. It also assesses and initially evaluates the urgency of medical assistance. It acts as a helping hand, provides a virtual medical consultation, and supports HPs and medical workers, especially during peak ED hours in EDs.

- 3.

- Medical Doctor Appointment: Another salient feature of this work is that it provides a medical doctor appointment with specialization and available time slots. It also features cancellation at any time at the patient’s convenience.

- 4.

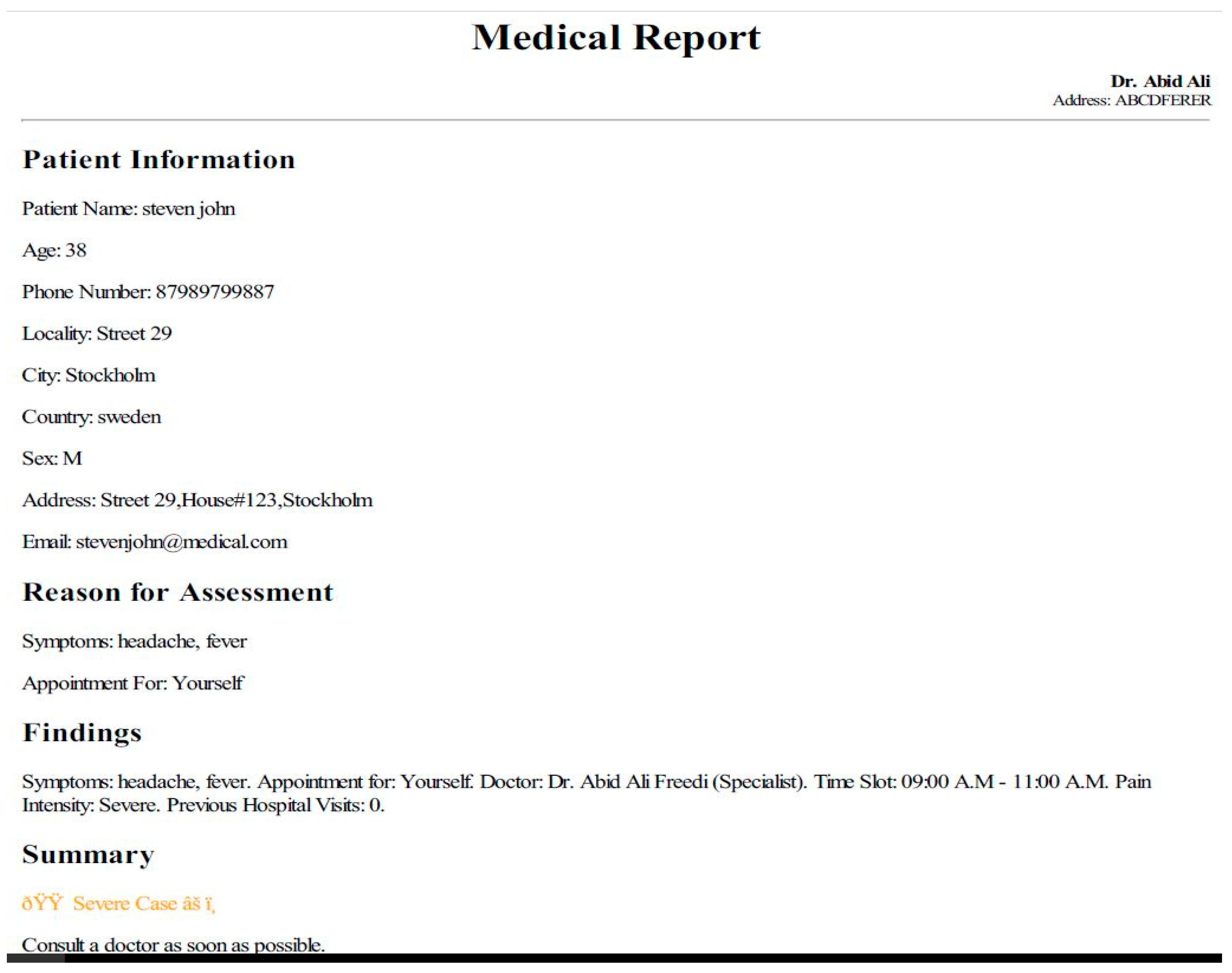

- Generate Initial Assess Report: This section breaks down reports forwarded to healthcare workers, especially triage nurses. It generates signaling to prompt the patient’s medical condition and status, alarming the urgency of medical assistance on a prior basis. This automatically generated report covers the patient’s demographic information, the reason for assessment based on prior question-answering sessions, initial findings, and assessment. It also sends the summary with signaling signs.

- 5.

- Facilitation to the Healthcare Practitioners Empowering LLMs: This section also benefits HPs and medical workers, especially in patient–doctor meetings. Here, CAs leverage LLMs to help generate potential diagnosis options, treatment recommendations, and medication advice for HPs. CAs generate automated queries to retrieve the relevant information from the knowledge graphs (KGs) stored in graph databases like Neo4j. They also leverage supplementary information using LLMs to provide a suitable choice to HPs during their consultations with patient–doctor appointments.

4.10. Prototyping Evaluation

4.10.1. Evaluation Strategy

4.10.2. Scenario-Based Evaluation

- 1.

- Construction of Ontological Model: The ontological model served as a backbone of the system, facilitating medical knowledge in a structured form and efficient knowledge retrieval, improving the clinical decision-making process, and enhancing LLMs’ performance.

- 2.

- Knowledge base Querying: Using knowledge representation language like description logic (DL) and SPARQL, we queried the ontological model to retrieve relevant information.

- 3.

- LLM Interaction: The LLM presented the initial assessment report and was tasked with providing appropriate advice or recommendations verified from the knowledge base (ontological model).

- 4.

- Performance Evaluation: The LLM’s responses were evaluated against the gold standard, which could be domain experts’ opinions or established clinical guidelines.

4.10.3. Expert Review

4.11. Modeling Workshop Sessions

5. Discussion

- 1.

- AI-powered CAs, as an assistive technology, are invaluable tools used in alliance with HPs to enhance diagnostic accuracy and support decision-making by providing reliable diagnostic assistance.

- 2.

- CAs contribute significantly to interpreting clinical images such as computer tomography and X-ray, enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

- 3.

- AI-powered CAs offer multiple functionalities, such as medical assistants, providing seamless access to critical patient information, including medical history, updated diagnoses, and different symptoms, such as allergies. They support physicians in making informed decisions and enable regular monitoring of disease progression, particularly in Emergency Departments (EDs). CAs help doctors prepare for surgery in the operating room by giving vital information on the patient’s medical history and current blood samples.

- 4.

- These assisting tools serve as interactive knowledge bases that let users ask questions about new treatments and illnesses that are currently effective and encourage HPs to keep learning and improving their skills.

- 5.

- CAs also help physicians accomplish enormous documentation duties, and CAs lessen the workload associated with documentation activities. This support improves healthcare delivery’s overall efficacy and efficiency by assisting doctors in devoting more time to important patient care tasks and providing invaluable support to enhance patient outcomes.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Meaning |

| CAs | Conversational agents |

| LLMs | Large language models |

| ED | Emergency department |

| SHAICF | Service-oriented human–AI collaborative framework |

| OEM | Ontology engineering methodology |

| DSRM | Design science research method |

| PED | Pediatric emergency department |

| PEDology | Ontological metadata model PED |

| KT | Knowledge translation |

| ODPs | Ontology design patterns |

| Convology | Conversational ontology |

| SO | Service ontology |

| RO | Resource ontology |

| PO | Personalized ontology |

| DO | Disease ontology |

| KMs | Knowledge models |

| DMs | Domain models |

| CM | Context model |

| RM | Role model |

| CompM | Competencies model |

| KGs | Knowledge graphs |

References

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Li, D.; Raymond, L.R. Generative AI at Work; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, T. GPT-doctor: Customizing large language models for medical consultation. In Proceedings of the 45th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Bangkok, Thailand, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, T. Living up to the Chatbot hype: The influence of anthropomorphic design cues and communicative agency framing on conversational agent and company perceptions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, C.; Sidner, C.L. Robots and avatars as hosts, advisors, companions, and jesters. AI Mag. 2017, 30, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, K.; Gillespie, A. Co-constructing intersubjectivity with artificial conversational agents: People are more likely to initiate repairs of misunderstandings with agents represented as human. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large language models: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Zhou, L.; Fang, X. Generative AI for intelligence augmentation: Categorization and evaluation frameworks for large language model adaptation. Trans. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 6, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, S.; Brendel, A.B.; Morana, S.; Kolbe, L. On the design of and interaction with conversational agents: An organizing and assessing review of human-computer interaction research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 23, 96–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madeira, J. Use of chatbots in the covid-19: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the Conferência da Associação Portuguesa de Sistemas de Informação (CAPSI’2022), Bolanha, Portugal, 3–5 November 2022; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, K. Conversational AI: Open domain question answering and commonsense reasoning. Electron. Proc. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2019, 306, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Sim, K.; Kuen, A.T.Y.; O’donnell, R.R.; Lim, S.T.; Wang, W. Designing AI-based conversational agent for diabetes in a multilingual context. In Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 12–14 July 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Isabella, S.I.; Waizenegger, L.; Seidel, S.; Morana, S.; Benbasat, I.; Lowry, P.B. Reinventing collaboration with autonomous technology-based agents. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh European Computer Information Systems (ECIS), Stockholm & Uppsala, Sweden, 8–14 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, M.; Kellett, J.; Lenzitti, B.; Helfert, M. Proposed use of a conversational agent for patient empowerment. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2021), Online, 11–13 February 2021; pp. 817–824. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Kankanhalli, A.; Ong, D.C. Human-AI collaboration in healthcare: A review and research agenda. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Grand Wailea, HI, USA, 5 January 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, C.; Wells, L.; Bartels, S.A.; Walker, M. Patient and provider perspectives on emergency department care experiences among people with mental health concerns. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, L.; Maier, C.; Mattke, J.; Weitzel, T. ChatBots in healthcare: Status quo, application scenarios for physicians and patients and future directions. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eight European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS2020), Marrakech, Morocco, 15–17 June 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Bhandari, A.; Yuksel, B.; Kocaballi, A.B. An emboided conversational agent to minimize the effects of social isolation during hospitalization. In Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Melbourne, Australia, 12 July 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hamounda, I.B.; Tantan, O.C.; Boughzala, I. Towards an ontological framework for knowledge sharing in healthcare systems. In Proceedings of the 20th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chaiyi, Taiwan, 27 June 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock, H.; Perera, P.; McLean, K.; Roberts, G. Variation in paediatric clinical practice: An evidence check review. Sax Inst. Aust. 2014, 1, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remick, K.; Gausche-Hill, M.; Joseph, M.M.; Brown, K.; Snow, S.K.; Wright, J.L. Pediatric readiness in the emergency department. Pediatrics 2018, 142, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwick, M.; Dubrowski, R.; Petricca, K. Knowledge Translation: The Rise of Implementation; American Institute for Research (AIR): Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kadariya, D.; Venkataramanan, R.; Yip, H.Y.; Karl, M.; Thirunarayanan, K.; Sheth, A. Kbot: Knowledge-enabled personalized chatbot for asthma self-management. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), Washington, DC, USA, 12–15 June 2019; pp. 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi, A.; Presutti, V. Ontology design patterns. In Proceeding of the International Handbooks on Information Systems, 2nd ed.; Springer Germany: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dragoni, M.; Rizzo, G.; Senese, M.A. Convology: An Ontology for Conversational Agents in Digital Health. In Proceedings of the Web Semantic: Cutting Edge and Future Directions in Healthcare; Academic Press: West Bengal, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peffers, K.; Tunnanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A. A design science research methodology for information systems research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgund, P.; Sharman, R.; Thimmanayankanaplaya, S.S. Design science approach to developing using chatbot for sexually transmitted diseases. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Americas Conference on Information Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 9–13 August 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Aurisicchio, M. Designing conversational agents: A self-determination theory approach. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dingler, T.; Kwasnicka, D.; Wei, J.; Gong, E.; Oldenburg, B. The use of promise of conversational agents in digital health. IMIA Yearb. Med. Inform. 2021, 30, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregor, S.; Seidel, S.; Kruse, L.C. The Anatomy of a design principle. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stieglitz, S.; Hofeditz, L.; Brunker, F.; Ehnis, C.; Mirbabaie, M.; Ross, B. Design principles for conversational agents to support emergency management agencies. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, J.R.G.; Ruiz, M.A.G.; Herrera, R.; Cabello, E.; Legrand, S.; Elliman, D. Ontology languages for the semantic web: A never completely updated review. Knowl. Based Syst. 2006, 19, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zacharewicz, G.; Chen, D. An ontology-driven framework towards building enterprise semantic information layer. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2013, 2727, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brut, M.; Al-Kukhun, D.; Péninou, A.; Canut, M.F.; Sèdes, F. Structuration et Accès au Dossier Patient Médical Personnel: Approche par Ontologie et politique d’accès XACML. In Proceedings of the 1ère Édition du Symposium sur l’Ingénierie de l’Information Médicale, SIIM 2011, Toulouse, France, 9–10 June 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Roy, P.; Paramesh, N. An ontology-based framework for managing semantic interoperability issues in e-Health. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on e-Health Networking, Application and Service (HEALTHCOM 2008), Singapore, 7–9 August 2008; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, W.; Wimalasiri, J.; Ray, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Wilson, C. An ontology driven multi-agent approach to integrated eHealth systems. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. 2010, 1, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, H.J.; Sen, S.; Hausler, R.A. Roadmap for the future design of human-robot collaboration. IFAC Pap. 2020, 53, 10196–10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Silva, F.; Santos, V. Trends of human-robot collaboration in industry contexts: Handover, learning, and metrics. Senors 2021, 21, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z. Architecture support for context-aware adaptation of rich sensing smartphone applications. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2018, 12, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.D.; Barcellos, M.P.; Falbo, R.D.A. Ontologies in human-computer interaction: A systematic literature review. Appl. Ontol. 2021, 16, 421–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbrico, A.; Orlandini, A.; Cesta, A. An ontology for human-robot collaboration. In Proceedings of the 53rd CRIP Conference on Manufacturing Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 1097–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Hum. Lang. Technol. 2019, 1, 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020), Online, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Min, S.; Hoi, S. Ontology-based system for emergency department triage using ICD-10. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2021, 27, 198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kouame, G.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; Exposito, E.; Peres, F. A semantic approach based on ontologies for healthcare emergency systems. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 123, 106289. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Rathore, V.S.; Kalla, A. Ontology-driven clinical decision support system for emergency medical services. Int. J. E-Health Med. Commun. (IJEHMC) 2019, 10, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Cao, S.; Zhu, S.; Yang, Z. Evaluating the performance of GPT-3 in medical education and clinical decision-making: A pilot research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e29973. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.08608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.R. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowl. Acquis. 1993, 5, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Mat-Surin, E.S.; Mahmood, A.K. An improved methodology for collaborative construction of reusable, localized, and shareable ontology. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareedi, A.A.; Tarasov, V. Modelling of the ward round process in a healthcare unit. In Proceedings of the Practice of Enterprise Modeling (PoEM 2011), Oslo, Norway, 2–3 November 2011; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fareedi, A.A.; Ismail, M.; Ghazawneh, A.; Bergquist, M.; Ortiz-Rodriguez, F. The utilization of artificial intelligence for developing autonomous social robots within health information systems. In Proceedings of the TEXT2KG 2023: Second International Workshop on Knowledge Graph Generation from Text, ESWC, Hersonisson, Greece, 28–29 May 2023; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Solutions, U.S.A. Organizational Transformation at a Pediatric Emergency Department. Available online: https://www.usacs.com/services/case-studies/organizational-transformation-at-a-pediatric-emergency-department/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Maala, K.F.; Ben-Othman, S.; Jourdan, L.; Smith, G.; Renard, J.M.; Hammadi, S.; Biau, H.Z. Ontology for Overcrowding Management in Emergency Department; International Medical Informatics Association (IMIA) and IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 947–952. [Google Scholar]

- Fareedi, A.A.; Ghazawneh, A.; Bergquist, M. Artificial intelligence agents and knowledge acquisition in health information system. In Proceedings of the 14th Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS), Catanzaro, Italy, 14–15 October 2022; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barata, I.; Auerbach, M.; Badaki-Makun, Q.; Benjamin, L.; Joseph, M.M.; Lee, M.O.; Mears, K.; Petrack, E.; Wallin, D.; Ishimine, P.; et al. A Research agenda to advance pediatric emergency care through enhanced collaboration across emergency departments. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, B.; Kunt, M.M.; Damarsoy, F.F.; Demir, M.C.; Aksu, N.M. NEDOCS: Is it really useful for detecting emergency department overcrowding today? Medicine 2020, 99, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjo, L.; Dunn, A.G.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chen, J.; Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Gallego, B.; Magrabi, F.; YS Lau, A.; et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcho, O.; Fernandez-Lopez, M.; Gomez-Perez, A.; Lopez-Cima, A. Building Legal Ontologies with Methontology and Webode. In Law and the Semantic Web: Legal Ontologies, Methodologies, Legal Information Retrieval, and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heiderberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.; Bench-Capon, T.; Visser, P. Methodologies for Ontology Development; Department of Computer Science, University of Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zeginis, D.; Hasnain, A.; Loutas, N.; Deus, H.F.; Fox, R.; Tarabanis, K. A collaborative methodology for developing a semantic model for interlinking cancer chemoprevention linked-data sources. Semant. Web 2014, 5, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoladore, D.; Pessot, E. Collaborative ontology engineering methodologies for the development of decision support systems: Case studies in the healthcare domain. Electronics 2021, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowatsch, T.; Schachner, T.; Harperink, S.; Barata, F. Conversational agents as mediating social actors in chronic disease management involving health care professionals, patients, and family members: Multisite single-arm feasibility research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, J.; Pries-Heje, J.; Baskerville, R. FEDS: A framework for evaluation in design science research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.M. Making Use: Scenario-Based Design of Human-Computer Interaction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–382. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 1–362. [Google Scholar]

- Molich, R.; Nielsen, J. Improving a human-computer dialogue. Commun. ACM 1990, 33, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnefaie, A.; Singh, S.; Kocaballi, B.; Prasad, M. An overview of conversational agent: Applications, challenges and future directions. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST), Online, 26–28 October 2021; pp. 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Lanham, H.J.; Jr McDaniel, R.R.; Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.L.; Stange, K.C.; Tallila, A.F.; Nutting, P. How improving practice relationship among clinicians and nonclinicians can improve quality in primary care. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2009, 35, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.; Haupt, C.E. AI chatbots, health privacy, and challenges to HIPPA compliance. JAMA 2023, 330, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, C.; Potts, C.; Ennis, E.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.D.; O’Neill, S.; Malcolm, M.; Kuosmanen, L.; Kostenius, C.; Vakaloudis, A.; et al. Can chatbot help support a person’s mental health? Perceptions and views from mental healthcare professionals and experts. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. 2021, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DSRM Activities | Activities Description | Activities/Techniques | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity 1: Problem Identification | Describe the research issue and provide evidence for the solutions’ usefulness, like ontology-driven CA to bring transformation from the “As-Is” situation to the “To-Be” situation to support digitalization. | Understanding and identifying a research problem using modeling workshops [51] and observations. | |

| Activity 2: Define Objectives | In what way should the issue be resolved? | Adjust the applications related to the domain, like the CA system development. | |

| Activity 3: Design and Development | Creation of design artifacts that solve the problem. Construct an ontological service-oriented framework using agile ontology engineering methodologies. | ||

| Phase 1: (OM) | Feasibility of the research. Human resource estimation. | Identify the purpose, scope, and case related to PED. How many knowledge engineers, ontologists, domain specialists, technical writers, and developers are needed to construct a domain-oriented ontology? [50]. | |

| Activity 4: Demonstration | Phase 2: (OD) | Domain Analysis Knowledge Acquisition (KA) Conceptualization Level of detail Agile OEM Construction | Comprehension of a discourse domain (PED). Conduct interviews, surveys, observations, and discussions to identify resources. Construct specification using OntoUML (https://ontouml.org/ (accessed on 25 June 2025)), etc. Define the level of detailing of discourse. Agile OEM construction follows design patterns (OPDs) (http://ontologydesignpatterns.org/wiki/Main_Page (accessed on 25 June 2025)). |

| Activity 5: Evaluation | Phase 3 (OI) Phase 4 (OU) | Implementation (Model to language) Evaluation (Refinement) Instantiation Maintenance Ontology Localization Integration and Merging Interoperability Sample Application | Initiate the implementation process for Agile OEMs. Evaluate the Agile OEMs and follow the refinement process from time to time. Populate shared ontology using an ontology tool (e.g., Protégé (https://protege.stanford.edu/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)), etc.) The creation of ontologies is an evolutionary process and must be maintained according to new requirements. Translate an ontology into local natural language. Integrate Agile OEMs with other sub-domains’ ontologies. Support Interoperability characteristics between different systems using a global conceptual structure. Usage in domain-related applications (e.g., CAs) |

| Activity 6: Communication | Stage 4 (OU) | Documentation | Document all necessary concepts and their relationship to the developed Agile OEMs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fareedi, A.A.; Ismail, M.; Ahmed, S.; Gagnon, S.; Ghazawneh, A.; Arooj, Z.; Nazir, H. Enriching Human–AI Collaboration: The Ontological Service Framework Leveraging Large Language Models for Value Creation in Conversational AI. Knowledge 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge6010002

Fareedi AA, Ismail M, Ahmed S, Gagnon S, Ghazawneh A, Arooj Z, Nazir H. Enriching Human–AI Collaboration: The Ontological Service Framework Leveraging Large Language Models for Value Creation in Conversational AI. Knowledge. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleFareedi, Abid Ali, Muhammad Ismail, Shehzad Ahmed, Stephane Gagnon, Ahmad Ghazawneh, Zartashia Arooj, and Hammad Nazir. 2026. "Enriching Human–AI Collaboration: The Ontological Service Framework Leveraging Large Language Models for Value Creation in Conversational AI" Knowledge 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge6010002

APA StyleFareedi, A. A., Ismail, M., Ahmed, S., Gagnon, S., Ghazawneh, A., Arooj, Z., & Nazir, H. (2026). Enriching Human–AI Collaboration: The Ontological Service Framework Leveraging Large Language Models for Value Creation in Conversational AI. Knowledge, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge6010002