Abstract

Background: Environmental surfaces are key reservoirs for pathogen transmission, with the survival of bacteria on fomites influenced by factors such as temperature, humidity, and microbial interactions. This study aimed to determine microbial surface contamination and to determine the antimicrobial resistance profile of bacteria isolated from the indoor surface where the presence of cockroaches was observed in households of the Greater Letaba Municipality (GLM), South Africa. Methods: Swab samples were collected from kitchen countertops and food storage areas with visible cockroach activity. Bacteria were isolated and identified using standard microbiological methods, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was conducted with the Vitek® Automated 2 system. Results: Of the 120 samples collected, 82 (68%) showed bacterial growth, resulting in 190 isolates. The majority of isolates (93%) were Gram-negative, comprising Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Escherichia, Serratia, Stenotrophomonas, Pantoea, Raoultella, and Salmonella species, with 98% demonstrating multidrug resistance (MDR) to multiple antibiotics. Resistance was particularly high against gentamicin (94%), fluoroquinolones (88%) and amikacin (77%). Among Gram-positive isolates, all belonged to the Enterococcus species, with 22% being resistant to one or two of the tested antimicrobial agents and 78% exhibiting MDR. Conclusions: The study revealed a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria isolated from household surfaces. The spread of antibiotic-resistant pathogens via environmental surfaces presents a significant risk to human health, safety, and well-being.

1. Introduction

Microorganisms exist in nearly all natural environments. Their populations typically thrive in environments where favourable temperatures, moisture, and nutrients support their development and reproduction [1,2]. In societies where fecal waste is inadequately managed and released into the environment untreated, pathogenic microorganisms can accumulate in high concentrations and are readily disseminated through various reservoirs [3,4]. Moreover, research has demonstrated that cockroaches act as carriers of pathogenic microorganisms. Their actions enable them to contaminate foods, utensils, kitchen areas, and other household environments as well as surfaces [5]. Cockroach droppings may harbour bacteria that cause foodborne illnesses, as well as fungi and other harmful pathogens [5,6,7].

Environmental surfaces constitute critical reservoirs for pathogen transmission. Pathogenic bacteria can persist on fomites for extended time periods, with their survival influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and the presence of other microorganisms. Fecal contamination from both human and animal sources is prevalent on household surfaces, including floors, in low-income communities, elevating the risk of human disease. Prior research has documented the presence of Escherichia coli on various fomites, such as kitchen surfaces and cloths, toilet fixtures, door handles, and bathroom surfaces [4,8,9]. These contaminated surfaces act as vectors for transmission, posing a significant health risk, particularly for foodborne illnesses.

Foodborne diseases constitute a significant and increasingly prevalent global public health challenge, encompassing a wide range of illnesses. While often manifesting as gastrointestinal symptoms, these diseases can also present with neurological, immunological, and other systemic effects [10]. The ingestion of contaminated food can lead to multi-organ failure, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality [11]. Observed globally and continuing to rise, the emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is driven by factors such as the inappropriate use of antimicrobials, inadequate infection prevention and control measures, and the weak regulation of antimicrobial use [12,13]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has revised its Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL), identifying 24 bacterial families as significant drug-resistant threats to human health [14]. Frequently used household cleaning products may not effectively eliminate common household bacteria [15,16]. Furthermore, research indicates that sporadic or inconsistent use of disinfectants is ineffective in reducing bacterial counts in kitchen environments. In contrast, adherence to a prescribed, regular cleaning, and disinfection protocol has been shown to be effective in reducing such counts [16]. Published data on AMR profiles of bacteria isolated specifically from household environments in South Africa are extremely limited. Most available studies have a disproportionate focus on urban or hospital-associated environments, while rural and low-resource households remain under-represented.

The study aim was to determine microbial surface contamination and antimicrobial resistance profiles of bacteria isolated from indoor surfaces where the presence of cockroaches was observed in rural households of Greater Letaba Municipality (GLM), South Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

An exploratory study was undertaken in March 2021 across six villages located in the rural areas of the Greater Letaba Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. The study formed part of a larger study entitled “The assessment of the role of cockroaches in bacterial dissemination in relation to sanitary—hygienic conditions in ward 2 villages of Bolobedu area, Limpopo Province”. Research assistants were recruited and received comprehensive training on sample collection, storage and transportation. They were equipped with standardized guidelines and operating procedures (SOPs) to ensure the integrity and consistency of the collected samples. A multistage sampling methodology was employed to select households due to the geographically dispersed nature of the population across multiple villages. This approach facilitated systematic selection at different levels, ensuring representativeness while maintaining logistical efficiency. Each research assistant was assigned to one village. The assistants initiated their route by randomly selecting a cardinal direction. Subsequently, samples were collected from every fifth household along the designated path to ensure a representative and unbiased selection.

2.2. Surface Sampling

Sterile, single-use, regular-sized traditional rayon swabs containing Amies Agar Gel (COPAN, LASEC SA) were utilized for sample collection. These swabs were employed to gather specimens from strategically selected sites, including kitchen countertops and food storage areas exhibiting evidence of cockroach activity. Indicators of such activity included the presence of live cockroaches, their exoskeletons, fecal matter, eggs, egg cases, and proximity to cockroach traps. To ensure thorough sampling, each swab was rotated across the surface to collect material from all sides, covering an area of at least 10 cm × 10 cm. To maintain anonymity, the swabs were assigned unique identification numbers. Following collection, the swabs were placed in transport media and maintained at a controlled temperature of 2–8 °C. The samples were then securely transported to the Water and Health Research Centre (WHRC) laboratory at the University of Johannesburg, where they were stored under appropriate conditions for subsequent bacterial analysis.

2.3. Microbial Testing

Standard microbiological methods were employed for the isolation and identification of bacterial species. Initially the ESKAPE group of pathogens were chosen as target species as they are common agents of both community-acquired and healthcare-associated infections. Additionally, they were previously isolated from environmental sources [17,18], but their spread in the non-healthcare environment by vectors such as cockroaches has not been fully investigated. As the study progressed, other Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial species were included for selection.

Swab samples were inoculated onto seven types of selective agar media to facilitate the isolation of specific bacterial species: Mannitol Salt agar (for Staphylococcus aureus) (Oxoid, UK), Slanetz and Bartley agar (for Enterococcus faecium) (Oxoid, UK), Coliform Chromoselect agar (for Escherichia coli) (Oxoid, UK), MacConkey agar for (Enterobacter spp.), Campylobacter agar base (for Acinetobacter baumannii), Pseudomonas Cetrimide agar (for Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and Klebsiella Chromoselect agar (for Klebsiella pneumoniae) (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). These media were selected as they have previously been shown to be reliable in the isolation of the target species from clinical and environmental samples as well as in recovering control strains from spiked samples [19,20]. Cultures were incubated for 24–48 h at 37 °C. Presumptive colonies were sub-cultured on nutrients or Mueller Hinton agar to obtain pure isolates (Oxoid, UK). Isolates were further cultured on Mueller Hinton agar and identified using the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., Marcy-l’Étoile, France). Prior to Vitek® 2 analysis, Gram staining was performed to confirm Gram-stain characteristics. Isolates were suspended in 0.45% saline solution to achieve a 0.5–0.63 McFarland standard, as per manufacturer’s instructions, before using the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., France) and GP and GN identification cards for Gram-positive and Gram-negative isolates, respectively [21].

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for each antimicrobial under test were determined by the system after testing using AST-N256 and AST-P645 cards for Gram-negative and Gram-positive isolates, respectively. The MICs were then interpreted by the system using Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [22]. Individual results for each antimicrobial under test were reported as susceptible, intermediately resistant or resistant by the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., France). As is the usual convention for standardized reporting methods by the CLSI [22]. Only acquired resistances were reported by the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., France) which is programmed with the latest CLSI standards for each antimicrobial tested against each bacterial species. For the Gram-negative bacilli: susceptibility, intermediate resistance or resistance to 19 antimicrobials in 12 antimicrobial categories were tested. For The Gram-positive isolates: susceptibility, intermediate resistance or resistance to 22 antimicrobials in 16 antimicrobial categories were tested. In accordance with the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention guidelines for standardized reporting of antimicrobial resistance [23], isolates were defined as multidrug-resistant (MDR) if they tested non-susceptible (resistant or intermediately resistant) to one or more antimicrobials in three or more antimicrobial categories; as extensively drug resistant (XDR) if non-susceptible to one or more antimicrobials in all but two antimicrobial categories or pan drug resistant (PDR) if non-susceptible to one or more antimicrobials in all antimicrobial categories tested.

2.5. Quality Assurance

Reference strains were used for quality control purposes for both isolation and for routine maintenance of the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., France).

Reference strains used for isolation included:

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 33592

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922

Enterococcus faecium ATCC 27270

Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 10031

Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606

Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13406

In addition to the details for reference strains already provided for identification purposes, the accuracy and validity of results generated by the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., France) is assured by regular maintenance as well as the regular analysis of the following AST Quality Control Strain Sets: AST-GN QC Set 5189P [Escherichia coli ATCC 25922; Escherichia coli ATCC 35218; Klebsiella quasipneumoniae ATCC 700603; Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853] and AST-GP QC Set 5220P [Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212; Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 51299; Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC 29213; Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC BAA-976; Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC BAA-977; Staphylococcus aureus ATCC® BAA-1026] (Microbiologics, St. Cloud, MN, USA). All Vitek identification cards have built-in quality controls. In addition, each anti-microbial test well in each antimicrobial susceptibility testing card has a matched positive control growth well to ensure internal quality control of the Vitek 2® Automated System (BioMerieux Inc., France). Furthermore, strict adherence to standardized protocols and manufacturer’s recommendations was maintained to ensure the consistency and reproducibility of the research. The laboratory adheres to a quality policy in line with good laboratory practice as well as several measures standard in ISO/IEC 17025:2017. Quality control measures are in place for all media production as well as all analysis undertaken.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data entry and analysis were carried out with Microsoft Excel 2016. Cross-tabulations were utilized to calculate the percentage of isolates of each species exhibiting susceptibility, intermediate resistance, or resistance to the tested antimicrobial agents. Drug termination refers to the discontinuation or interruption of the test reaction, resulting in an incomplete evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility.

3. Results

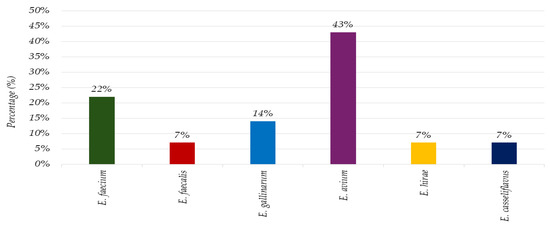

One hundred and twenty swab samples were collected, of which 82 (62%) exhibited bacterial growth. From these samples, 190 bacterial isolates were identified. Among the identified isolates, 176 (93%) were classified as Gram-negative species, while 14 (7%) were identified as Gram-positive species (Tables S1 and S2). All 14 (100%) Gram-positive isolates recovered from the sampled surfaces were identified as Enterococcus spp. as depicted in Figure 1. Among these, Enterococcus faecium was classified in 3 isolates (22%), Enterococcus faecalis in 1 (7%) isolate, Enterococcus gallinarum in 2 (14%) Enterococcus avium in 6 (43%) isolates, Enterococcus hirae in 1 (7%) isolate, and Enterococcus casseliflavus in 1 (7%) isolate.

Figure 1.

The microbial landscape: prevalence of Gram-positive isolates on environmental surfaces in a household setting.

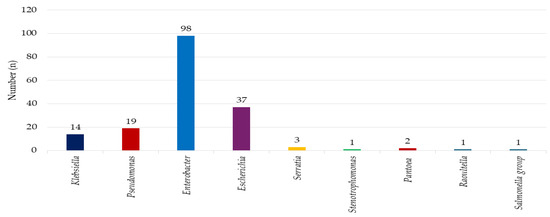

Among the 176 Gram-negative bacterial isolates, Klebsiella species were identified in 14 (7%) isolates, Pseudomonas species in 19 (11%) isolates, Enterobacter species in 98 (55%) isolates, Escherichia species in 37 (21%) isolates, Serratia species in 3 (2%) isolates, Stenotrophomonas in 1 (1%) isolate, Pantoea in 2 (1%) isolates, Raoultella in 1 (1%) isolate, and Salmonella species in 1 (1%) isolate, as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The microbial landscape: prevalence of Gram-negative isolates on environmental surfaces in a household setting.

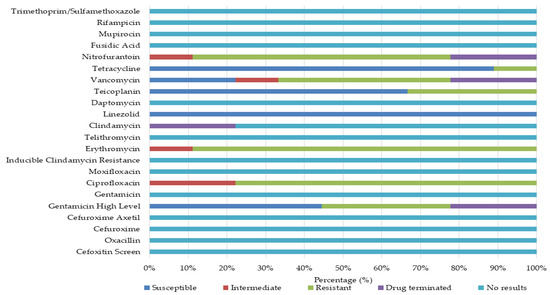

Isolates of Enterococcus spp. (n = 9) were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Among these, 7 (78%) isolates exhibited MDR. The remaining 2 (22%) of the isolates displayed non-susceptibility to one or two antimicrobials. Of the MDR isolates, 4 (57%) were identified as Enterococcus faecium, 2 (29%) as E. gallinarum, and 1 (14%) as E. hirae. Of the 2 isolates that were non-susceptible to one or two antimicrobials, 1 (50%) was E. avium, and the other 1 (50%) was E. casseliflavus. Figure 3 indicates the results of antimicrobial susceptibility screening of Gram-positive isolates from environmental surfaces. Complete susceptibility was observed for linezolid.

Figure 3.

Phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and resistance rates of Gram-positive isolates from household surfaces.

In contrast, high levels of resistance were documented for erythromycin (89%), ciprofloxacin (78%), nitrofurantoin (67%), and vancomycin (44%), with some isolates demonstrating intermediate susceptibility. The E. faecium isolates demonstrated complete resistance to erythromycin and nitrofurantoin, with high levels of resistance also being observed to ciprofloxacin and vancomycin (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative antimicrobial resistance patterns of Gram-positive bacteria by species.

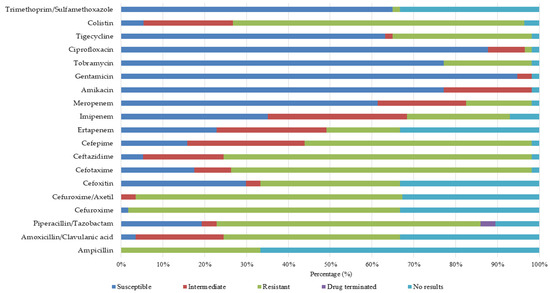

All isolates exhibited susceptibility to linezolid and tetracycline, while a significant proportion displayed high-level susceptibility to gentamicin (synergistic effects) (75%) and teicoplanin (67%). The E. gallinarum isolates exhibited a pan-resistant phenotype, demonstrating 100% resistance to ciprofloxacin, teicoplanin, erythromycin, and vancomycin, along with resistance to three other antimicrobials. Only intermediate susceptibility was observed against nitrofurantoin. The E. hirae isolates displayed a multidrug-resistant (MDR) pattern, exhibiting high-level resistance to gentamicin, erythromycin, teicoplanin, and nitrofurantoin. In contrast, 100% susceptibility was observed for linezolid and tetracycline. Enterococcus casseliflavus isolates exhibited resistance to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and teicoplanin, while remaining susceptible to linezolid and tetracycline. The E. avium isolates exhibited non-susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and were ineffective against macrolides. Conversely, 100% susceptibility was observed for linezolid, teicoplanin, and tetracycline. A total of 57 Gram-negative bacterial isolates were recovered and subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The predominant species identified were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32%), Klebsiella oxytoca (16%), and Enterobacter cloacae complex (11%). Other species encountered included Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterobacter cancerogenus, Serratia fonticola, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, Citrobacter amalonaticus, Raoultella planticola, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Pantoea agglomerans, and Salmonella spp. A high prevalence of MDR was observed, with 56 (98%) of the isolates exhibiting non-susceptibility to one or more antimicrobial agents. Figure 4 summarizes the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Gram-negative isolates. Significant resistance levels were observed against a broad spectrum of antibiotics, including polymyxin, penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors, colistin, anti-pseudomonal penicillins, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and second-generation cephalosporins.

Figure 4.

Phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and resistance rates of Gram-negative isolates from household surfaces.

Overall, high levels of susceptibility were observed for amikacin (77%), gentamicin (94%), and tobramycin (77%), carbapenems (61%), glycylcyclines (63%), fluoroquinolones (88%), and folate pathway inhibitors across (65%) multiple species. Conversely, significant resistance was observed against various antimicrobial classes, including carbapenems, cephalosporins, and polymyxins. Enterobacter aerogenes demonstrated complete resistance to polymyxins, imipenem, second-generation cephalosporins, cephalomycins, ceftazidime, and antipseudomonal penicillin (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparative antimicrobial resistance patterns of Gram-negative bacteria by species.

Table 3.

Comparative antimicrobial resistance patterns of Gram-negative bacteria by species.

Enterobacter cancerogenus showed complete resistance to carbapenems, anti-pseudomonal penicillins, second-generation and third-generation cephalosporins, polymyxin, penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors. Serratio fonticola demonstrated complete resistance to carbapenems, second-generation cephalosporins, penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors. Citrobacter amalonaticus displayed complete resistance to second-generation cephalosporins, polymyxin, anti-pseudomonal penicillins, penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors, and carbapenems. Serratio marcescens displayed non-susceptibility to polymyxin, penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors and second- and third-generation cephalosporins, with 77% susceptibility to aminoglycosides and fourth-generation cephalosporins. Klebsiella oxytoca demonstrated complete (100%) non-susceptibility to aminopenicillin and second-generation cephalosporins. Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae demonstrated complete resistance to aminopenicillin, polymyxin, and second-generation cephalosporins. Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae exhibited total resistance to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, aminopenicillin, and polymyxin. Raoultella planticola was completely resistant to polymyxin, carbapenems, and aminopenicillin. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displayed 100% resistance to extended spectrum cephalosporins, glycylcyclines, and antipseudomonal penicillin. Pseudomonas agglomerans was entirely non-susceptible to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins, with notable non-susceptibility to third-generation cephalosporins and carbapenem. Salmonella spp. exhibited 100% resistance to glycylcycline, carbapenem, cephalomycins, aminopenicillin, extended spectrum cephalosporins, glycylcycline, second-generation cephalosporins and penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia demonstrated complete resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

4. Discussion

Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are known to persist on dry, inanimate surfaces under humid and adverse conditions for extended periods, thereby acting as reservoirs for transmission [24]. This persistence poses a public health concern as these surfaces can serve as contact points, potentially causing infections in individuals exposed to them. This study observed a higher prevalence of microbial contamination (86%) on indoor surfaces compared to findings in previous research. For instance, a publication reported contamination with pathogenic microorganisms in 84% of kitchens sampled, with swabs collected from items such as kitchen towels, gas stove knobs, refrigerator handles, water taps, and sponges [25]. Similarly, another report found that 28% of surfaces and items examined exhibited moderate to heavy bacterial growth, with kitchen cloths (86%) and taps (52%) demonstrating the highest levels of contamination [16]. In support these findings, research indicated that 64% of 50 samples collected from 10 kitchens harbouring pathogenic microorganisms [26]. These results collectively emphasize the significant microbial burden associated with inanimate objects within kitchen environments. This study aligns with previous published research [16,25,27] that reported bacterial contamination on indoor surfaces and within kitchen environments. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria exhibited a higher prevalence in the present investigation. Enterobacter spp. was frequently isolated, followed by Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Escherichia spp., and Serratia spp. In contrast, Enterococcus spp. dominated the Gram-positive isolates, with E. avium being the most prevalent.

Previous studies have also identified a range of bacterial contaminants with reports of isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Salmonella spp., S. aureus, Shigella spp., S. epidermidis, and Micrococcus spp. [25], K. pneumoniae, Proteus species, S. epidermidis, E. coli, S. aureus, and Enterobacter spp. [26], and S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, Shigella spp., E. coli, and K. pneumoniae isolated from household surfaces [22]. Further illustrating the diversity of bacterial contaminants, further research demonstrated the presence of Pseudomonas, Pantoea, Bacillus, Firmicutes, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus species on contaminated surfaces [21]. Similarly, research identified bacteria associated with Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria [23]. These findings collectively highlight the persistent and diverse bacterial contamination of indoor environments, particularly in kitchen areas. The bacterial species identified in this study including Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, Escherichia, and Salmonella that are recognized as AMR pathogens of major clinical and public health importance. These organisms are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, demonstrate increasing resistance trends, and are often difficult to prevent and control due to their high transmissibility and limited treatment options [28]. While not all are classified as globally critical pathogens, their impact may be critical in certain populations and geographic regions where healthcare resources are constrained [29].

In particular, members of the Enterobacterales family, which were most frequently observed in this study, are designated as “critical” priority pathogens by the WHO. They represent the highest level of public health concern because of their limited therapeutic options, rising rates of multidrug resistance, and lack of effective agents in the development pipeline [28,30]. Infections caused by pathogens in this critical category are not only difficult to treat but also uniquely challenging to prevent, with resistance mechanisms that may spread globally or manifest as MDR strains within specific populations or settings [31,32]. Gram-negative bacteria predominantly develop antimicrobial resistance through multiple mechanisms, including reduced permeability of the outer membrane that restricts drug uptake, structural modification of drug targets, enzymatic inactivation of antimicrobial agents, and active efflux mediated by specialized transporter systems [33]. The presence of an additional outer membrane, combined with a broad repertoire of efflux pumps, enables these organisms to effectively minimize intracellular drug accumulation, thereby diminishing antimicrobial efficacy. These mechanisms are particularly relevant to the isolates identified in this study, such as Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella species, which are well known for harbouring extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), carbapenemases, and multidrug efflux systems [34,35]. The widespread distribution of such resistance determinants in these taxa not only complicates treatment but also facilitates the persistence and dissemination of multidrug-resistant strains within community and household environments [34,35,36].

An analysis of nine bacterial isolates obtained from this current study revealed that 78% of the isolates demonstrated resistance to three or more antimicrobial agents, meeting the definition MDR. The MDR isolates were predominantly E. faecium (57%), followed by E. gallinarum (29%) and E. hirae (14%). In contrast, isolates showing non-susceptibility to one or two antimicrobial agents were evenly distributed and identified as E. avium as well as E. casseliflavus. The study highlighted erythromycin resistance as the most common (89% of isolates), followed by resistance to ciprofloxacin (77%), nitrofurantoin (67%), vancomycin (67%), teicoplanin (33%), and high-level gentamicin (33%). These findings underscore the concerning prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among Enterococcus species isolated from kitchen environments. Such resistance poses a significant public health risk, especially in kitchens where food is prepared and consumed, as it increases the potential for cross-contamination and foodborne illness in rural households. Poor hygiene practices may contribute to the presence of MDR Enterococcus in kitchens. Likewise, insufficient handwashing and inadequate cleaning and disinfection of surfaces can facilitate the spread of pathogenic bacteria.

The data further revealed that Gram-positive bacteria predominantly exhibited resistance to erythromycin, fluoroquinolones, nitrofuran, glycopeptides, and aminoglycosides. Among Gram-negative bacteria, MDR was widespread. Resistance to key antimicrobial agents, including penicillins, polymyxins, penicillin and β-lactam inhibitors, anti-pseudomonal penicillins, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, and non-extended-spectrum cephalosporins, was particularly pronounced. These findings align with previous research documenting the persistence and dissemination of MDR bacteria in household environments, emphasizing the need for improved hygiene practices and pest control measures to mitigate the risks associated with antimicrobial resistance [16,27,33]. Although household studies remain limited for comparison with the current study, clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Pretoria were confirmed both phenotypically and genomically, with all strains exhibiting ESBL production. The isolates were resistant to nearly all β-lactams except carbapenems and certain β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Resistance was universal against aztreonam, first- to fourth-generation cephalosporin, while resistance to anti-pseudomonal penicillins was also highly prevalent. Sixteen isolates exhibited cefoxitin, suggestive of AmpC-mediated resistance [37]. While Pretoria isolates remained susceptible to carbapenems, the current results documented complete carbapenem resistance in several Enterobacterales, including Enterobacter cancerogenus, Serratia fonticola, Raoultella planticola, and Salmonella spp. Similarly, polymyxin resistance was absent in the Pretoria dataset but widespread in the attached results, particularly among K. pneumoniae subspecies and Citrobacter. These findings suggest that resistance in Pretoria, though severe, may represent an earlier stage in the evolutionary trajectory compared to the broader resistance profiles documented in this study. Comparative findings from the Eastern Cape revealed resistance to ampicillin (86.2%), and a study in Maputo noted that ampicillin resistance was above 50% in all bacterial groups except Enterobacter spp. The attached study also documented significant resistance to penicillins and β-lactam inhibitors [38,39]. Resistance to cephalosporins is another shared trend. The study shows 100% resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and total resistance to non-extended spectrum cephalosporins in Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae. This mirrors findings from a study in Kadangaru, Nigeria, where P. aeruginosa isolates showed 100% resistance to cephalosporins, and a Miami study which reported 95% resistance to ceftazidime [40]. Despite the similarities, there are notable differences in antimicrobial susceptibility. The results show high levels of susceptibility to amikacin (77%), gentamicin (94%), and tobramycin (77%) in Gram-negative isolates. Conversely, while a North Carolina study found that Pseudomonal strains were uniformly susceptible to gentamicin and tobramycin, it is important to note that the current study found complete resistance to high-level gentamicin in E. hirae isolates [41]. Furthermore, a lower susceptibility rate to gentamicin (76.6%) was also found compared to the findings [38]. Resistance to carbapenems also varied. The study findings show significant resistance to carbapenems in several species, including Enterobacter cancerogenus, Serratia fonticola, and Citrobacter amalonaticus. In contrast, the North Carolina study found that Pseudomonal strains were uniformly susceptible to imipenem, and resistance to imipenem among Enterobacter isolates was rare (0.7%) [41]. This highlights that resistance to certain last-resort antibiotics can vary significantly depending on the bacterial species and the environmental context. Lastly, resistance to vancomycin in Enterococcus spp. also presents a difference. While the current results reported a high level of vancomycin resistance (44%) in Enterococcus spp., a study from North Carolina found a much lower resistance rate of 6.2%, which was limited to a single strain [41]. This suggests a potentially higher prevalence or different clonal spread of vancomycin-resistant strains in the Greater Letaba Municipality.

Clinically, the resistance profiles observed in this study significantly hinder treatment effectiveness. The high prevalence of vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance eliminates essential first-line options for managing invasive Enterococcus infections, notably bloodstream and endocarditis cases [42,43]. High-level gentamicin resistance further undermines combination therapy (aminoglycoside + β-lactam/glycopeptide), which has traditionally been a mainstay for severe infections [43,44]. Resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones additionally limits therapeutic alternatives, compelling reliance on last-resort agents such as linezolid, daptomycin, or tigecycline that may be less accessible, costlier, or carry greater toxicity risks [45,46,47]. Moreover, such resistance in kitchen-derived Enterococcus spp. likely contributes to treatment failures in clinical settings by fostering environmental reservoirs of MDR strains.

The findings of this study are clinically relevant because isolates recovered from household surfaces mirror resistance phenotypes that are increasingly encountered in healthcare-associated infections. If such organisms are transmitted from domestic environments into vulnerable individuals such as children, the elderly, or immunocompromised patients, they may complicate treatment, delay recovery, and elevate the risk of severe outcomes [29]. Household transmission of these pathogens also provides a potential bridge between the community and healthcare facilities, thereby amplifying the risk of nosocomial outbreaks driven by multidrug-resistant strains [31,43]. This reinforces the importance of considering household environments within the One Health surveillance framework and integrating them into broader AMR control strategies. Additionally, studies suggested that pests, particularly cockroaches, could play a role in disseminating antimicrobial-resistant bacteria [5,6,7]. Samples were collected from areas where cockroach activity was evident. It is likely that cockroaches that come into contact with the contaminated surfaces may also acquire these pathogens and transfer them to other fomites, including food and water, exacerbating the risk of disease transmission.

Enhanced public health strategies are essential to address this growing concern and to reduce the potential for foodborne illnesses and the spread of resistant pathogens. This includes: environmental hygiene and pest control strategies by promoting routine disinfection of surfaces and integrated pest control to remove mechanical vectors; community education on safe food handling, hand hygiene, and rational antibiotic use; targeted antimicrobial stewardship workshops to avoid empiric cephalosporins for Enterobacterales and polymyxins for Serratia; to limit carbapenems for non-carbapenemase P. aeruginosa and to use confirmatory AST before deploying last-line β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors.

This study provides valuable insights into the antimicrobial resistance profiles of bacteria isolated from household surfaces in the Greater Letaba Municipality, South Africa.

Study Strength and Limitation

A key strength lies in its focus on a rural setting where limited AMR data exist, thus contributing novel evidence with direct relevance to public health interventions. Despite these strengths, samples were collected from areas with evident cockroach activity, no comparative sampling was conducted in regions without such activity. Consequently, it is not possible to definitively attribute increased contamination rates to cockroach presence. Furthermore, microbial isolation was limited to specific target organisms using selective media, which may have excluded the detection of other clinically relevant pathogens or AMR bacteria.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed alarmingly high levels of MDR among the bacteria isolated from household surfaces. The detection of resistance to clinically important antibiotics such as colistin, carbapenems, and vancomycin has direct clinical relevance, as these drugs are often reserved as last-line therapies for severe infections. The persistence of such resistant organisms in domestic environments raises the likelihood of therapeutic failure should exposed individuals develop infections, thereby complicating treatment outcomes and increasing morbidity and mortality risks. From a public health perspective, these findings underscore the urgent need to strengthen household hygiene practices, pest control interventions, and community-level AMR awareness campaigns. Within the One Health framework, contaminated surfaces as reservoirs and vectors of resistant pathogens highlights the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. The dissemination of MDR bacteria across these domains not only threatens individual households but also contributes to the broader cycle of resistance in communities. The infection control implications are particularly significant. Surfaces that harbour MDR pathogens can serve as foci for repeated cross-contamination, facilitating outbreaks of foodborne disease and reducing the effectiveness of routine disinfection. These results therefore call for the adoption of evidence-based cleaning protocols, the integration of household-level AMR surveillance into public health programmes, and the reinforcement of global AMR containment strategies in line with WHO recommendations. The high prevalence of AMR documented in this study provides critical evidence for policymakers, clinicians, and environmental health practitioners. It highlights the need for multidisciplinary approaches that bridge clinical care, public health interventions, and environmental management to reduce the burden of resistant infections and safeguard treatment efficacy in vulnerable communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hygiene5040055/s1, Table S1: Gram Negative; Table S2: Gram Positives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; methodology, M.L.M., L.H., T.G.B. and N.N.; software, M.L.M., L.H. and T.G.B.; validation M.L.M.; formal analysis, M.L.M., L.H., T.G.B. and N.N.; investigation, M.L.M. and L.H.; resources, T.G.B.; data curation, M.L.M. and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.M.; writing—review and editing, M.L.M., L.H., T.G.B. and N.N.; visualization, M.L.M., T.G.B. and N.N.; supervision, T.G.B. and N.N.; project administration, M.L.M.; funding acquisition, T.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Water and Health Research Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Johannesburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by University of Johannesburg Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS) Research Ethics Committee (REC-866-2020, 7 December 2020), the Higher Degree Committee (HCD-01-105-2020, 7 December 2020), and the Greater Letaba Municipality (10 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all family representatives of the households involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of all the data collectors and households from Ward 2 of Bolobedu, Greater Letaba Municipality and the laboratory assistants from the Water and Health Research Centre at the University of Johannesburg.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GLM | Greater Letaba Municipality |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| BPPL | Bacterial Priority Pathogens List |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistance |

| WHRC | Water and Health Research Centre |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum β-lactamases |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Greenwood, D.; Slack, R.C.B.; Peutherer, J.F. Medical Microbiology, 16th ed.; Elsevier Science Limited: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; ISBN 978-81-312-0100-8. [Google Scholar]

- Otu-Bassey, I.B.; Ewaoche, I.S.; Okon, B.F.; Ibor, U.A. Microbial Contamination of House Hold Refrigerators in Calabar Metropolis-Nigeria. Am. J. Epidemiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 51, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Julian, T.R. Environmental Transmission of Diarrheal Pathogens in Low and Middle Income Countries. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2016, 18, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exum, N.; Kosek, M.; Davis, M.; Schwab, K. Surface Sampling Collection and Culture Methods for Escherichia coli in Household Environments with High Fecal Contamination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moges, F.; Eshetie, S.; Endris, M.; Huruy, K.; Muluye, D.; Feleke, T.; G/Silassie, F.; Ayalew, G.; Nagappan, R. Cockroaches as a Source of High Bacterial Pathogens with Multidrug Resistant Strains in Gondar Town, Ethiopia. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2825056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajka, E.; Pancer, K.; Kochman, M.; Gliniewicz, A.; Sawicka, B.; Rabczenko, D.; Stypułkowska-Misiurewicz, H. Characteristics of bacteria isolated from body surface of German cockroaches caught in hospitals. Prz. Epidemiol. 2003, 57, 655–662. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, H.-H.; Chen, W.-C.; Peng, C.-F. Isolation of Bacteria with Antibiotic Resistance from Household Cockroaches (Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica). Acta Trop. 2005, 93, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, L.D.; Levy, K.; Menezes, N.P.; Freeman, M.C. Human Diarrhea Infections Associated with Domestic Animal Husbandry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 108, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.R.; Pickering, A.J.; Harris, M.; Doza, S.; Islam, M.S.; Unicomb, L.; Luby, S.; Davis, J.; Boehm, A.B. Ruminants Contribute Fecal Contamination to the Urban Household Environment in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4642–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, V.N.; Aleru, C.P.; Uweh, E.J. Bacterial Contamination of Some Domestic and Laboratory Refrigerators in Port Harcourt Metropolis. Eur. J. Health Sci. 2021, 6, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases: Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group 2007–2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-4-156516-5. [Google Scholar]

- Moghnieh, R.; Araj, G.F.; Awad, L.; Daoud, Z.; Mokhbat, J.E.; Jisr, T.; Abdallah, D.; Azar, N.; Irani-Hakimeh, N.; Balkis, M.M.; et al. A Compilation of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Data from a Network of 13 Lebanese Hospitals Reflecting the National Situation during 2015–2016. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, Y.A.; Mengistie, E.; Tolcha, A.; Birhan, B.; Asmare, G.; Gebeyehu, N.A.; Gelaw, K.A. Indoor Air Bacterial Load and Antibiotic Susceptibility Pattern of Isolates at Adare General Hospital in Hawassa, Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1194850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Erdogrul, O.; Erbilir, F. Microorganisms in Kitchen Sponges. Internet J. Food Saf. 2005, 6, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford, J.; Berezin, E.N.; Courvalin, P.; Dwyer, D.; Exner, M.; Jana, L.A.; Kaku, M.; Lee, C.; Letlape, K.; Low, D.E.; et al. An International Survey of Bacterial Contamination and Householders’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions of Hygiene. J. Infect. Prev. 2013, 14, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastmeier, P. From “one Size Fits All” to Personalized Infection Prevention. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 104, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE Pathogens in the Environment: Antibiotic Resistance Status, Community-Acquired Infection and Risk to Human Health. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 244, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, D.M.; Khan, I.U.H.; Patidar, R.; Lapen, D.R.; Talbot, G.; Topp, E.; Kumar, A. Isolation and Characterization of Acinetobacter Baumannii Recovered from Campylobacter Selective Medium. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havenga, B.; Clements, T.; Reyneke, B.; Waso, M.; Khan, W. Exploring the Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of WHO Critical Priority List Bacterial Strains|BMC Microbiology|Full Text. Available online: https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12866-019-1687-0 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Pincus, D.H. Microbial Identification Using the bioMérieux VITEK® 2 System. In Encyclopedia of Rapid Microbiological Methods; bioMérieux, Inc.: Hazelwood, MO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI M100 31st Edition Released|News|CLSI. Available online: https://clsi.org/about/news/clsi-publishes-m100-performance-standards-for-antimicrobial-susceptibility-testing-31st-edition/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birru, M.; Mengistu, M.; Siraj, M.; Aklilu, A.; Boru, K.; Woldemariam, M.; Biresaw, G.; Seid, M.; Manilal, A. Magnitude, Diversity, and Antibiograms of Bacteria Isolated from Patient-Care Equipment and Inanimate Objects of Selected Wards in Arba Minch General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2021, 12, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.S. Isolation and Microbiological Identification of Bacterial Contaminants in Food and Household Surfaces: How to Deal Safely. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2015, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiga, I.; Shobha, K.; Mustaffa, M.; Bismi, N.; Yusof, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Nor, N. Bacterial Contamination in the Kitchen: Could It Be Pathogenic? WebmedCentral Med. Educ. 2012, 3, WMC003256. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.S.; Choi, J.K.; Jeong, I.S.; Paek, K.R.; In, H.-K.; Park, K.D. A nationwide survey on the hand washing behavior and awareness. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2007, 40, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founou, R.C.; Founou, L.L.; Essack, S.Y. Clinical and Economic Impact of Antibiotic Resistance in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. No Time to Wait: Securing the Future from Drug-Resistant Infections. Report to the Secretary-General of the United Nations; Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (IACG): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, K.; Molinier, L.; Hallit, S.; Sartelli, M.; Catena, F.; Coccolini, F.; Craig Hardcastle, T.; Roques, C.; Salameh, P. Drivers of Antibiotic Resistance Transmission in Low- and Middle-Income Countries from a “One Health” Perspective—A Review. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, C.M.; Alm, R.A.; Årdal, C.; Bandera, A.; Bruno, G.M.; Carrara, E.; Colombo, G.L.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; Essack, S.; Frost, I.; et al. A One Health Framework to Estimate the Cost of Antimicrobial Resistance. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.E.; Bates, S.T.; Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Leff, J.W.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Diversity, Distribution and Sources of Bacteria in Residential Kitchens. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Epidemiology of β-Lactamase-Producing Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00047-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Lin, T.-J.; Cheng, Z. Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Mechanisms and Alternative Therapeutic Strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reygaert, W.C. An Overview of the Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms of Bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbelle, N.M.; Feldman, C.; Sekyere, J.O.; Maningi, N.E.; Modipane, L.; Essack, S.Y. Pathogenomics and Evolutionary Epidemiology of Multi-Drug Resistant Clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Pretoria, South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, J.U.; Nwodo, U.U. Molecular Characterization of Antibiotic Resistance Determinants in Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates Recovered from Hospital Effluents in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphossa, V.; Langa, J.C.; Simbine, S.; Maússe, F.E.; Kenga, D.; Relvas, V.; Chicamba, V.; Manjate, A.; Sacarlal, J. Environmental Bacterial and Fungal Contamination in High Touch Surfaces and Indoor Air of a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit in Maputo Central Hospital, Mozambique in 2018. Infect. Prev. Pract. 2022, 4, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesoji, A.T.; Onuh, J.P.; Palang, I.P.; Liadi, A.M.; Musa, S. Prevalence of Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Selected Residential Sewages in Dutsin-Ma, Katsina State, Nigeria. J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutala, W.A.; Weber, D.J.; Barbee, S.L.; Gergen, M.F.; Sobsey, M.D.; Samsa, G.P.; Sickbert-Bennett, E.E. Evaluation of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Home Kitchens and Bathrooms: Is There a Link between Home Disinfectant Use and Antibiotic Resistance? Am. J. Infect. Control 2023, 51, A158–A163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichel, V.M.; Last, K.; Brühwasser, C.; von Baum, H.; Dettenkofer, M.; Götting, T.; Grundmann, H.; Güldenhöven, H.; Liese, J.; Martin, M.; et al. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 141, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Monte, M.; Kaleci, S.; Chester, J.; Zerbato, V.; Remitti, M.; Tili, A.; Dessilani, A.; Baldisserotto, I.; Esperti, S.; Di Trapani, M.D.; et al. Impact of Vancomycin Resistance on Attributable Mortality among Enterococcus faecium Bloodstream Infections: Propensity Score Analysis of a Large, Multicentre Retrospective Study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, dkaf242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Luo, H.; Dai, H.; Huang, W. Infective Endocarditis Due to High-Level Gentamicin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis Complicated Multisystemic Complications in an Elderly Patient. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, J.K.; Cattoir, V.; Hegstad, K.; Sadowy, E.; Coque, T.M.; Westh, H.; Hammerum, A.M.; Schaffer, K.; Burns, K.; Murchan, S.; et al. Update on Prevalence and Mechanisms of Resistance to Linezolid, Tigecycline and Daptomycin in Enterococci in Europe: Towards a Common Nomenclature. Drug Resist. Updates 2018, 40, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.-C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wang, J.-T.; Chang, S.-C. Daptomycin versus Linezolid for the Treatment of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcal Bacteraemia: Implications of Daptomycin Dose. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 890.e1–890.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwart, R.; Willrich, N.; Eckmanns, T.; Werner, G.; Ayobami, O. Low Proportion of Linezolid and Daptomycin Resistance Among Bloodborne Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecium and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Europe. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 664199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).