Abstract

Microalgae have garnered increasing attention as promising sources of diverse natural anti-inflammatory compounds, including carotenoids, phenolics, and unsaturated fatty acids. In this study, we aimed to examine the anti-inflammatory properties of the methanol extract of Nannochloropsis sp. G1-5 (NG15), a strain of marine microalgae isolated from the southern West Sea of the Republic of Korea. Pigment and metabolite analyses revealed that the extract contained various carotenoids and polyunsaturated fatty acids alongside significant quantities of phenolic and flavonoid compounds, which are known to have anti-inflammatory activities. Cytotoxicity assays confirmed that the extract was non-toxic to RAW 264.7 macrophage cells at concentrations up to 1 mg/mL. Upon lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of the macrophage cells, the NG15 extract significantly inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production in a dose-dependent manner up to 81%. In addition, the NG15 extract reduced the expression of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the LPS-stimulated cells. These findings suggest that NG15 methanol extract exerts anti-inflammatory effects primarily through the suppression of NO generation without inducing cytotoxicity. Overall, these results underscore NG15 as a promising natural resource for the development of non-toxic and effective anti-inflammatory agents with potential applications in the biomedical and cosmeceutical industries.

1. Introduction

Inflammation serves as a crucial host defense mechanism activated by physical trauma, exposure to toxic substances, microbial invasion, and tissue damage resulting from endogenous metabolites [1]. As an integral part of the innate immune system, inflammation is triggered by various chemical mediators released from injured tissues and infiltrating immune cells [2]. However, if the inflammatory response becomes excessive or does not resolve, it can transition to a chronic state, leading to the onset of various pathological conditions [3].

Macrophages are integral to the initiation of innate immune responses [4]. Upon activation, these cells engage in phagocytosis of invading microorganisms and secrete a range of proinflammatory mediators, including vasoactive amines, arachidonic acid derivatives, cytokines, platelet-activating factors, nitric oxide (NO), and reactive oxygen species. NO is synthesized from L-arginine by nitric oxide synthase (NOS), which is present in three isoforms: neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS), and inducible NOS (iNOS) [5]. The nNOS and eNOS forms are constitutively expressed and are involved in physiological functions by producing low, sustained levels of NO. The former is implicated in neurotransmission and skeletal muscle function, while the latter is involved in vasodilation. On the other hand, iNOS is robustly induced in response to stimuli such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and proinflammatory cytokines [6]. The excessive NO produced by iNOS rapidly reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant implicated in cellular injury, oxidative stress, carcinogenesis, and chronic inflammatory diseases [7].

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) engages Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), thereby activating NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways. This activation leads to the transcriptional upregulation of iNOS, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [8]. These mediators are crucial in intensifying the inflammatory responses characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, Sjögren’s syndrome, and other chronic immune-related disorders. Cyclooxygenase enzymes are pivotal in the regulation of prostaglandin biosynthesis [5]. COX-1 maintains physiological homeostasis through its constitutive function, whereas COX-2 is swiftly induced during inflammation to facilitate the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and other prostanoids that exacerbate pain, fever, and edema [9]. Interleukin-6, a key inflammatory cytokine, triggers the JAK–STAT signaling pathway, resulting in STAT3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, which further augments the transcription of COX-2, iNOS, and various cytokines, thereby sustaining inflammation [10,11].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are extensively employed in the management of inflammatory diseases, but their therapeutic effectiveness is frequently limited by adverse effects, including gastrointestinal damage, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, immunosuppression, and metabolic complications [12,13]. These limitations emphasize the importance of exploring safer alternatives, such as natural compounds capable of suppressing NO and PGE2 production, downregulating iNOS and COX-2 expression, and modulating the upstream inflammatory regulators [14,15].

Microalgae are increasingly recognized as significant biological resources because of their abundant carotenoids, phenolic compounds, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and other bioactive metabolites, which exhibit various biological activities such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [16,17]. The genus Nannochloropsis is particularly distinguished by its high levels of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), violaxanthin, and other xanthophylls, which exhibit immunomodulatory effects [18,19]. These metabolites have been shown to decrease the production of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), to inhibit proinflammatory cytokines, and to influence pathways related to nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) [5,20].

In this study, we analyzed the biochemical composition of the methanol extract of Nannochloropsis sp. G1-5 (NG15), including carotenoids, fatty acids, and phenolic compounds. We further examined the anti-inflammatory potential of the extract by assessing its effects on nitric oxide (NO) production and the expression of inflammation-associated mediators in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation of the Microroalgal Species

The microalgal strain Nannochloropsis sp. G1-5 (NG15), used in a previous study [17], was cultivated in a modified F/2 medium containing a twofold higher concentration of the primary macronutrients, NaNO3 and NaH2PO4·2H2O [17]. The cells were cultivated for 10 days in 300 mL of medium in 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks with an agitation rate of 115 rpm, continuous illumination at 80 μmol photons/m2/s at 23 °C, and 5% CO2 using a CO2-controlled incubator. Cell growth kinetics were quantified by measuring the optical density at 800 nm (OD800) using a spectrophotometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Subsequently, the cells were transferred to a modified F/2 medium supplemented with an additional 27 g/L NaCl to induce salt stress and cultured for an additional 20 days under identical physicochemical conditions. For downstream analyses, a 30 mL aliquot of the culture was harvested by centrifugation at 5000× g for 15 min, and the resulting cell pellet was immediately stored at −80 °C. All chemicals purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Preparation of the NG15 Extract

The frozen cell pellet obtained from 30 mL of culture was extracted with 15 mL of absolute methanol by vortexing at maximum speed for 15 min in each extraction, repeated twice at room temperature. The resulting supernatant was passed through a PTFE syringe filter (0.2 μm pore size) to remove residual cell debris. The filtrate was then concentrated to dryness using a centrifugal evaporator to obtain 55.8 mg of the dried NG15 extract, which was resuspended in ethanol to a desired concentration prior to cell treatment.

2.3. Analysis of Carotenoids and Fatty Acid Methyl Esters

The carotenoids in the crude extract of NG15 were analyzed using an HPLC system (1260 Infinity, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a Horizon C18/PFP column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 3 μm; Horizon Chromatography, Halifax, UK) using a binary gradient system with the mobile phases A, consisting of methanol:225 mM ammonium acetate (82:18, v:v), and B, consisting of ethanol. The gradient was set as follows: 0–20 min 100% A; 20–22 min 61.8% B; 22–33 min 25% A, 33–36 min 20% A, 36–37 min 10% A, 37–42 min 100% B, and 42 min 100% A. The flow rate was 0.9 mL/min and the column temperature was 33 °C [21]. Chlorophyll a and carotenoids were detected using a diode-array detector (300–720 nm). LC-MS analysis was conducted using an Agilent 1290 Infinity II HPLC system equipped with a diode array detector and an ISQ EC mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with an HESI-II electrospray ionization source. Carotenoids and chlorophyll a were separated using the same Horizon C18/PFP column as above, except that 0.1% (v/v) formic acid was added to the mobile phase solvents. The MS conditions were as follows: vaporizer temperature, 317 °C; ion transfer tube temperature, 350 °C; sheath gas pressure, 58.8 psig; auxiliary gas pressure, 5.2 psig; sweep gas pressure, 2 psig; positive ion mode; source voltage, 4 kV; and variable CID voltage. Pigment identification was performed based on retention times and UV-visible and mass spectral characteristics compared with authentic standards and literature data. Quantification was performed using calibration curves prepared from commercial standards (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and vaucheriaxanthin ester was calibrated using a violaxanthin standard [22,23].

FAME (fatty acid methyl ester) was prepared by acid-catalyzed transesterification of the crude extract of NG15 [17]. Briefly, 2 mL of methanolic sulfuric acid (3%, v/v) was added to a 15 mL, screw-capped, glass tube containing 5 mg of the crude extract in 1 mL of hexane. The mixture was vortexed and heated at 95 °C for 1.5 h. After cooling, 2 mL of water and hexane were added, and FAMEs were separated by collecting the organic phase. The extracted FAMEs were analyzed using a gas chromatograph (7890A GC, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a DB-FastFAME column (30 m × 0.25 mm, and 0.25 μm; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with the following conditions: injection volume 1 μL; split ratio 1:50; injector temperature 250 °C; detector temperature 280 °C; and oven temperature held at 50 °C for 0.5 min, increased to 194 °C at 30 °C/min, and increased to 240 °C at 5 °C/min. The FAMEs were identified and quantified by retention time and comparison with Supelco 37 Component FAME Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic and Total Flavonoid Content

The total phenolic content (TPC) of the NG15 extract was determined using the colorimetric Folin–Ciocalteu method, as previously described [24]. Briefly, 100 μL of the sample extract or gallic acid standard (dissolved in methanol at various concentrations) was mixed with 200 μL of 10% (v/v) Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Subsequently, 800 μL of Na2CO3 (700 mM) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 2 h. After incubation, 200 μL of the reaction mixture was transferred to a 96-well microplate, and the absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Gallic acid was used as the calibration standard, and TPC was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/g dry weight (DW).

The total flavonoid content (TFC) was quantified using the classical aluminum chloride colorimetric method [24]. Briefly, 100 μL of 2% (w/v) AlCl3 in methanol was mixed with 100 μL of the sample extract. After 10 min of incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 415 nm against a blank solution composed of 100 μL of extract mixed with 100 μL of methanol without AlCl3. A calibration curve was constructed using quercetin standards (0–250 μg/mL) prepared in methanol. TFC was expressed as mg quercetin equivalent (QE)/g DW.

2.5. Cell Culture and Viability Assay

RAW 264.7 macrophages (derived from BALB/c mice, obtained from Korean Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Republic of Korea: KCLB NO 40071) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h, followed by treatment with the NG15 extract for 72 h in a serum-free medium. Cell viability was assessed using the WST-1 assay. Each well was supplemented with 10% (v/v) WST-1 reagent (EZ-Cytox; DOGEN, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and incubated for 1 h, after which the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.6. NO Production Assay

Nitric oxide (NO) production was evaluated to assess the anti-inflammatory potential of NG15 extract. RAW 264.7 macrophages were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL and pre-incubated with the extract (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL) for 1 h. Subsequently, lipopolysaccharide (L6529, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added at a final concentration of 1 µg/mL, followed by incubation for 24 h. A sample of the culture supernatant (150 µL) was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was then measured at 548 nm, and nitrite levels were quantified using a sodium nitrite standard curve.

2.7. Inhibition of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-6 Expression

RAW 264.7 cells (derived from BALB/c mice) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well and were incubated for 24 h. The cells were pre-treated with extract at concentrations of 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 mg/mL for 1 h, followed by stimulation with LPS (1 µg/mL) for an additional 24 h. After incubation, cells were harvested, and total RNA was isolated using the easy-spin Total RNA Extraction Kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the SuperiorScript III RT Master Mix (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). qRT-PCR was performed with gene-specific primers (Table 1) and TOPreal SYBR Green qPCR premix (Enzynomics) using a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 12 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The melting curves were generated by increasing the temperature by 0.5 °C every 5 s from 65 °C to 95 °C. The cycle threshold value (CT) and differential expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [25], β-actin used as a housekeeping gene to normalize gene expression.

Table 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. All statistical analyses were based on paired Student’s t test using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biochemical Composition of the Methanol Extract of NG15

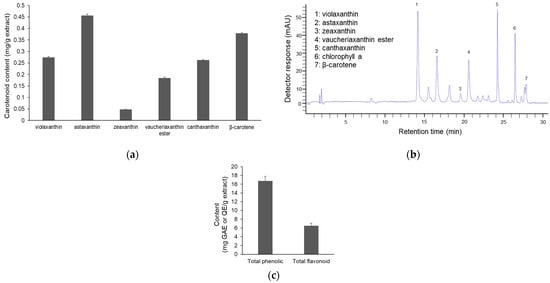

The methanol extract of NG15 revealed a distinct pigment composition characterized by six carotenoids: violaxanthin, astaxanthin, zeaxanthin, vaucheriaxanthin ester, canthaxanthin, and β-carotene (Figure 1a,b and Figures S1 and S2). The content of astaxanthin and β-carotene was 0.46 mg/g extract and 0.38 mg/g extract, respectively, followed by violaxanthin (0.27 mg/g), canthaxanthin (0.26 mg/g), vaucheriaxanthin ester (0.18 mg/g) and zeaxanthin (0.05 mg/g). This pigment distribution pattern is similar to those reported in previous studies on Nannochloropsis species [17,26,27]. Under environmental stress, such as high light intensity, high salinity and nutrient deprivation, these microalgae typically accumulate violaxanthin, astaxanthin, β-carotene, canthaxanthin and vaucheriaxanthin as the major carotenes and xanthophylls [18,28,29]. Violaxanthin has been reported to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activity against human cancer cells [29]. β-carotene is known to possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, inhibiting key inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB and MAPKs [30]. Additionally, canthaxanthin and astaxanthin are also well known for their strong antioxidant capabilities [17]. This result indicates that various carotenoids work synergistically to enhance the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of the extract.

Figure 1.

Pigment content of the NG15 methanol extract. (a) The content of major carotenoids in the NG15 methanol extract. (b) HPLC chromatogram of carotenoids in the NG15 methanol extract. (c) Total phenolic and flavonoid content of the NG15 methanol extract. Data and error bars are mean ± SD (n = 3).

Moreover, the methanol extract of NG15 exhibited high levels of total phenolics and flavonoids, quantified as 16.76 ± 1.0 mg GAE/g extract and 6.50 ± 0.57 mg QE/g extract, respectively (Figure 1c). Phenolic compounds are recognized for their radical-scavenging and metal-chelating properties. Flavonoids are noted for hydrogen-donating and resonance-stabilizing abilities and for contributing to the neutralization of free radicals and the inhibition of oxidative stress [31,32]. The extract of NG15 also contained various fatty acids in the lipid content, including polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) like linoleic acid, γ-Linolenic acid, Arachidonic acid, and EPA (Table 2), which are known to have anti-aging and anti-inflammatory activities [17]. Hence, the coexistence of phenolic and flavonoid classes suggests a complementary hydrophilic antioxidant system that potentially interacts synergistically with the identified PUFAs and lipid-soluble carotenoids [33].

Table 2.

Fatty acid composition of the NG15 methanol extract.

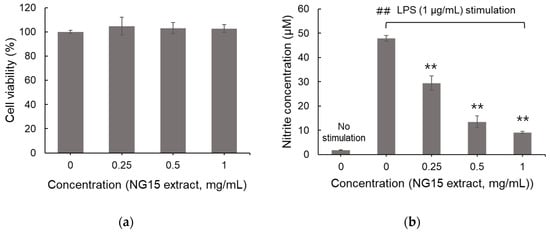

3.2. Effects of NG15 Extract on Cell Viability and LPS-Induced NO Production in RAW 264.7 Cells

As shown in Figure 2a, the methanol extract of NG15 did not exhibit cytotoxicity towards RAW 264.7 macrophages at concentrations ranging from 0 to 1 mg/mL. These results suggest that the extract is biocompatible and non-toxic to macrophages under the employed experimental conditions. Upon LPS stimulation (1 µg/mL), nitrite accumulation markedly increased up to 47.8 μM, reflecting enhanced nitric oxide (NO) production resulting from the inflammatory response to LPS stimulation. However, co-treatment with NG15 extract significantly and dose-dependently reduced nitrite levels to as low as 9.1 μM, demonstrating strong inhibition of NO synthesis in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Figure 2b). These results suggest that the NG15 extract effectively suppresses the activity of iNOS, a key enzyme responsible for NO overproduction during inflammation [34]. The simultaneous maintenance of cell viability and reduction in nitrite levels highlights the selective anti-inflammatory potential of the NG15 methanol extract, which mitigates inflammatory signaling without inducing cytotoxicity.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxicity and effect on NO production of the NG15 methanol extract. The effect of NG15 methanol extract (0–1 mg/mL) on (a) the viability of RAW 264.7 macrophages. (b) NO production in LPS (1 μg/mL)-stimulated macrophages. Data and error bars are mean ± SD (n = 3). ## denotes a p value < 0.01 versus non-stimulated control sample. ** denotes a p value < 0.01 versus the LPS-stimulated sample without NG15 extract.

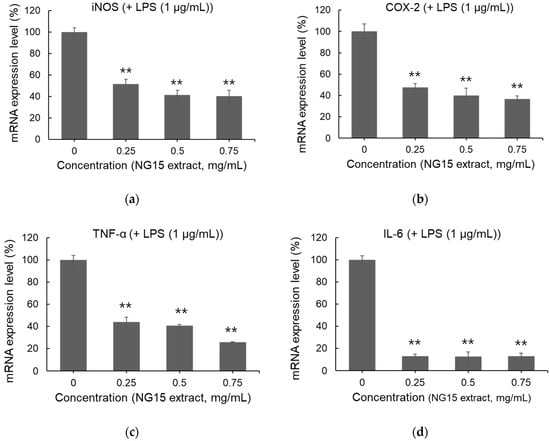

3.3. Effects of NG15 Extract on mRNA Expression of iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-6

The NG15 methanol extract significantly suppressed the mRNA expression of critical inflammatory mediators, including iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-6, in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages (Figure 3a–d). The application of LPS at a concentration of 1 μg/mL led to a pronounced increase in the transcription of these genes compared to that in the unstimulated control, confirming the activation of the inflammatory response. Conversely, NG15 extract treatment resulted in a notable, dose-dependent reduction in the expression of these genes. The expression levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were reduced to below 30% and 20% at an extract concentration of 0.75 mg/mL, highlighting a substantial reduction in proinflammatory cytokine production.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effect of the NG15 methanol extract on the expression of proinflammatory enzymes and cytokines in the LPS (1 μg/mL)-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Effect of NG15 methanol extract (0–0.75 mg/mL) on mRNA expression of (a) iNOS, (b) COX-2, (c) TNF-α and (d) IL-6. The mRNA expression level of each gene was normalized to that of the β-actin gene. Data and error bars are mean ± SD (n = 3). ** denotes a p value < 0.01 versus the LPS-stimulated sample without NG15 extract.

These results demonstrate that the NG15 methanol extract mitigates macrophage-driven inflammation by simultaneously suppressing upstream cytokine production and downstream effector enzymes involved in nitric oxide and prostaglandin biosynthesis. The downregulation of iNOS and COX-2 suggests that the extract reduces the level of nitric oxide, which is a critical mediator of inflammation and oxidative stress [35]. This inhibition is consistent with the result of NO reduction by treatment with the NG15 extract (Figure 2b) and with findings of a previous study [17], in which Nannochloropsis-derived extracts were reported to alleviate oxidative and inflammatory stress. These results further support the notion that carotenoids and phenolic compounds in the NG15 extract act cooperatively to suppress inflammation [36,37].

The selective suppression of inflammatory mediators without cytotoxic effects implies that the extract modulates immune responses through regulatory rather than destructive mechanisms. This property distinguishes the NG15 extract from synthetic anti-inflammatory agents, which often induce cellular stress or nonspecific inhibition [38]. The NG15 methanol extract possesses a well-balanced antioxidant profile comprising carotenoids, PUFAs, phenolics, and flavonoids, which supports the potential of NG15 as a multifunctional bioresource for cosmeceutical and nutraceutical applications aimed at mitigating photooxidative damage and inflammation-related cellular responses. Hence, NG15 extract effectively modulates inflammatory responses at both enzymatic and cytokine levels. Overall, our results support the potential of the NG15 methanol extract as a non-cytotoxic, naturally derived anti-inflammatory agent with promising applications in the biomedical and cosmeceutical fields.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory potential of methanol extract of NG15. The NG15 extract was composed of carotenoids, PUFAs, phenolic and flavonoids compounds, which are known to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. We found that the NG15 extract significantly inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-stimulated macrophages without cytotoxicity and mitigated inflammatory signaling by simultaneously suppressing upstream cytokine production and downstream effector enzymes involved in nitric oxide and prostaglandin biosynthesis. Our results indicate that NG15 has great potential to contribute to the development of anti-inflammatory agents with biomedical and cosmeceutical applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/phycology6010003/s1, Figure S1: Calibration curve of carotenoid standard; Figure S2: HPLC chromatogram, UV-vis spectrum of carotenoid standard and vaucheriaxanthin ester.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.H.K.; methodology, H.M. and J.Y.H.K.; validation, H.M. and J.Y.H.K.; formal analysis, H.M. and J.Y.H.K.; investigation, H.M. and J.Y.H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.H.K.; supervision, J.Y.H.K.; project administration, J.Y.H.K.; Funding Acquisition, J.Y.H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the institutional project (Grant No. 2025M00500) from the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea and the ‘regional innovation mega project’ program through the Korea Innovation Foundation, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Project Number: 2023-DD-UP-0007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Leiba, J.; Özbilgiç, R.; Hernández, L.; Demou, M.; Lutfalla, G.; Yatime, L.; Nguyen-Chi, M. Molecular Actors of Inflammation and Their Signaling Pathways: Mechanistic Insights from Zebrafish. Biology 2023, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megha, K.B.; Joseph, X.; Akhil, V.; Mohanan, P.V. Cascade of Immune Mechanism and Consequences of Inflammatory Disorders. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderton, H.; Wicks, I.P.; Silke, J. Cell death in chronic inflammation: Breaking the cycle to treat rheumatic disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.E.; Lee, J.S. Advances in the Regulation of Inflammatory Mediators in Nitric Oxide Synthase: Implications for Disease Modulation and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Hernández, T.; Rustioni, A. Expression of three forms of nitric oxide synthase in peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999, 55, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, R. Peroxynitrite, a stealthy biological oxidant. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26464–26472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Naka, T.; Nakahama, T.; Chinen, I.; Masuda, K.; Nohara, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Kishimoto, T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in combination with Stat1 regulates LPS-induced inflammatory responses. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesza, A.; Paczek, L.; Burdzinska, A. The Role of COX-2 and PGE2 in the Regulation of Immunomodulation and Other Functions of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganster, R.T.; Bradley, S.; Shao, L.; Geller, D. Complex regulation of human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene transcription by Stat 1 and NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8638–8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W.; Shin, J.-S.; Chung, K.-S.; Lee, Y.-G.; Baek, N.-I.; Lee, K.-T. Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Koreanaside A, a Lignan Isolated from the Flower of Forsythia koreana, against LPS-Induced Macrophage Activation and DSS-Induced Colitis Mice: The Crucial Role of AP-1, NF-κB, and JAK/STAT Signaling. Cells 2019, 8, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, S.; Palumbo, P.; Sponta, A.; Coppolino, M.F. Clinical pharmacology of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A review. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 11, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harirforoosh, S.; Asghar, W.; Jamali, F. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: An update of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal complications. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 16, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaylova, R.; Elincheva, V.; Gevrenova, R.; Zheleva-Dimitrova, D.; Momekov, G.; Simeonova, R. Targeting Inflammation with Natural Products: A Mechanistic Review of Iridoids from Bulgarian Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2025, 30, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.L.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, T.J.; Sun, J.; Rim, D.; Kim, Y.J.; Ko, S.B.; Jang, H.; Yoon, B.W. Anti-inflammatory effects of fimasartan via akt, erk, and nfkappab pathways on astrocytes stimulated by hemolysate. Inflamm. Res. 2016, 65, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Romero, S.; Torrella, J.R.; Pagès, T.; Viscor, G.; Torres, J.L. Edible microalgae and their bioactive compounds in the prevention and treatment of metabolic alterations. Nutrients 2021, 13, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, Y.M.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, J.Y.H. Exploring the Potential of Nannochloropsis sp. Extract for Cosmeceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forján, E.; Garbayo, I.; Henriques, M.; Rocha, J.; Vega, J.; Vílchez, C. UV-A mediated modulation of photosynthetic efficiency, xanthophyll cycle and fatty acid production of Nannochloropsis. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011, 13, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-N.; Chen, T.-P.; Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, F. Lipid Production from Nannochloropsis. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.L.; Huang, Z.; Mashimo, H.; Bloch, K.D.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Bevan, J.A.; Fishman, M.C. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature 1995, 377, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, N.; García-Blanco, A.; Gavalás-Olea, A.; Loures, P.; Garrido, J.L. Phytoplankton pigment biomarkers: HPLC separation using a pentafluorophenyloctadecyl silica column. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeland, E.S.; Garrido, J.L.; Clementson, L.; Andersen, K.; Thomas, C.T.; Zapata, M.; Airs, R.; Llewellyn, C.; Newman, G.L.; Rodríguez, F.; et al. Data sheets aiding identification of phytoplankton carotenoids and chlorophylls. In Phytoplankton Pigments: Characterization, Chemotaxonomy and Applications in Oceanography; Roy, S., Llewellyn, C., Egeland, E.S., Johnsen, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 665–822. [Google Scholar]

- Faé Neto, W.A.; Borges Mendes, C.R.; Abreu, P.C. Carotenoid production by the marine microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata in different low-cost culture media. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 2527–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X. Phenolic compounds and bioactivity evaluation of aqueous and methanol extracts of Allium mongolicum Regel. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forján Lozano, E.; Garbayo Nores, I.; Casal Bejarano, C.; Vílchez Lobato, C. Enhancement of carotenoid production in Nannochloropsis by phosphate and sulphur limitation. In Communicating Current Research and Educational Topics and Trends in Applied Microbiology; Formatex: Badajoz, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zanella, L.; Vianello, F. Microalgae of the genus Nannochloropsis: Chemical composition and functional implications for human nutrition. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 68, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubián, L.M.; Montero, O.; Moreno-Garrido, I.; Huertas, I.E.; Sobrino, C.; Valle, M.G.-D.; Parés, G. Nannochloropsis (Eustigmatophyceae) as source of commercially valuable pigments. J. Appl. Phycol. 2000, 12, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Moon, H.; Kwon, Y.M.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, J.Y.H. Comparative Analysis of the Biochemical and Molecular Responses of Nannochloropsis gaditana to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation: Phosphorus Limitation Enhances Carotenogenesis. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.; Yang, N.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R. Study of the Anti-Inflammatory Mechanism of β-Carotene Based on Network Pharmacology. Molecules 2023, 28, 7540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoujar, I.; Cacciola, F.; Abrini, J.; Mangraviti, D.; Giuffrida, D.; Oulad El Majdoub, Y.; Kounnoun, A.; Miceli, N.; Fernanda Taviano, M.; Mondello, L.; et al. The Contribution of Carotenoids, Phenolic Compounds, and Flavonoids to the Antioxidative Properties of Marine Microalgae Isolated from Mediterranean Morocco. Molecules 2019, 24, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.-M.; Zhang, J.-P.; Skibsted, L.H. Reaction Dynamics of Flavonoids and Carotenoids as Antioxidants. Molecules 2012, 17, 2140–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktan, F. iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production and its regulation. Life Sci. 2004, 75, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vliet, A.; Eiserich, J.P.; Cross, C.E. Nitric oxide: A pro-inflammatory mediator in lung disease? Respir. Res. 2000, 1, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calniquer, G.; Khanin, M.; Ovadia, H.; Linnewiel-Hermoni, K.; Stepensky, D.; Trachtenberg, A.; Sedlov, T.; Braverman, O.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Combined Effects of Carotenoids and Polyphenols in Balancing the Response of Skin Cells to UV Irradiation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, N.; Levy, R. The synergistic anti-inflammatory effects of lycopene, lutein, β-carotene, and carnosic acid combinations via redox-based inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, A.K.; Gurjar, V.; Kumar, S.; Singh, N. Molecular basis for nonspecificity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.