Treatment of Wastewater from the Fish Processing Industry and Production of Valuable Algal Biomass with a Biostimulating Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater and Microalgal Strains

2.2. Cultivation Conditions

2.3. Analysis of Algal Growth Parameters

2.4. Evaluation of Pigment, Protein, and Lipid Content

2.5. Microbial Community Structure Analysis

2.6. Evaluation of the Biostimulant Potential

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

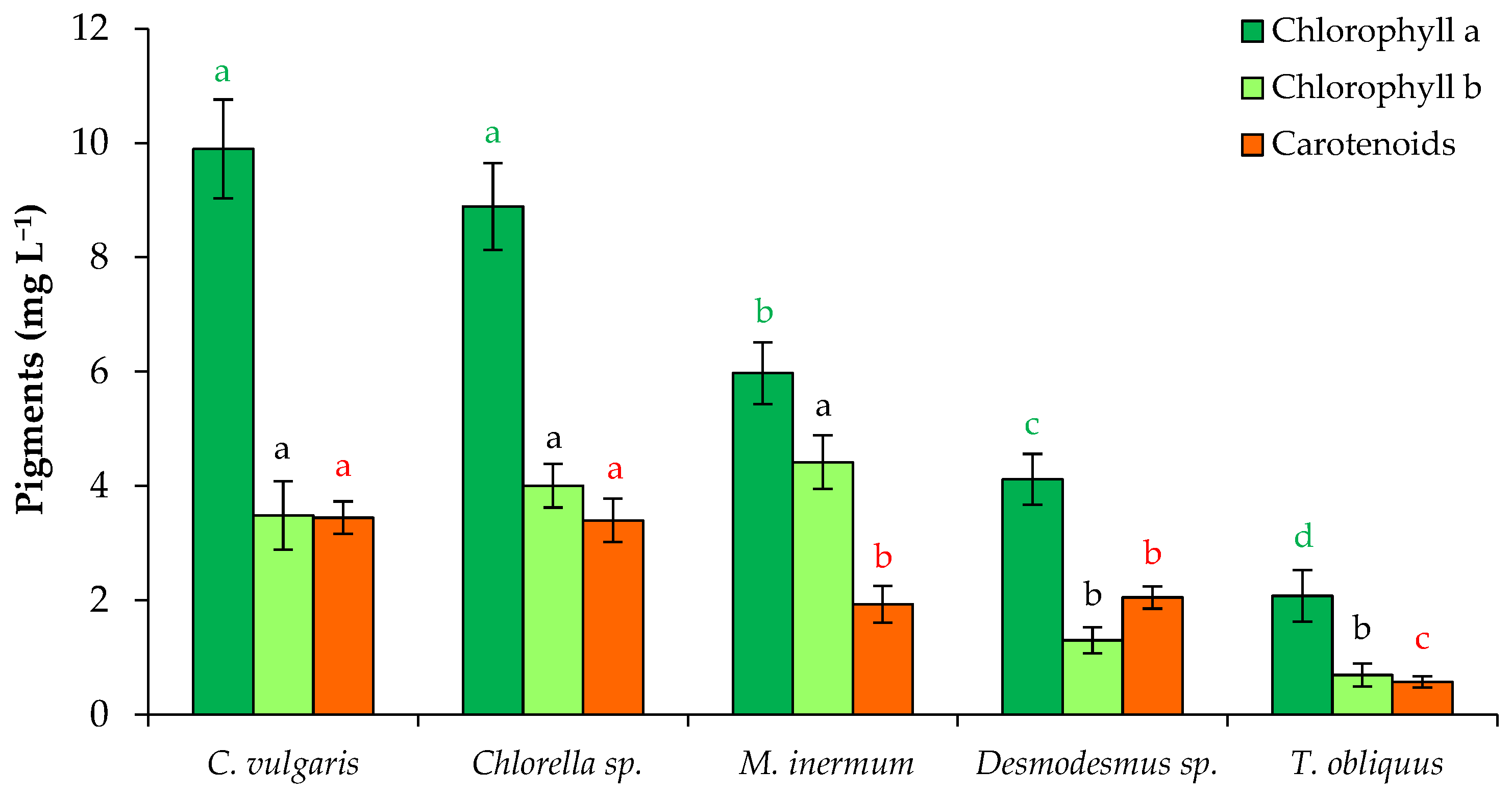

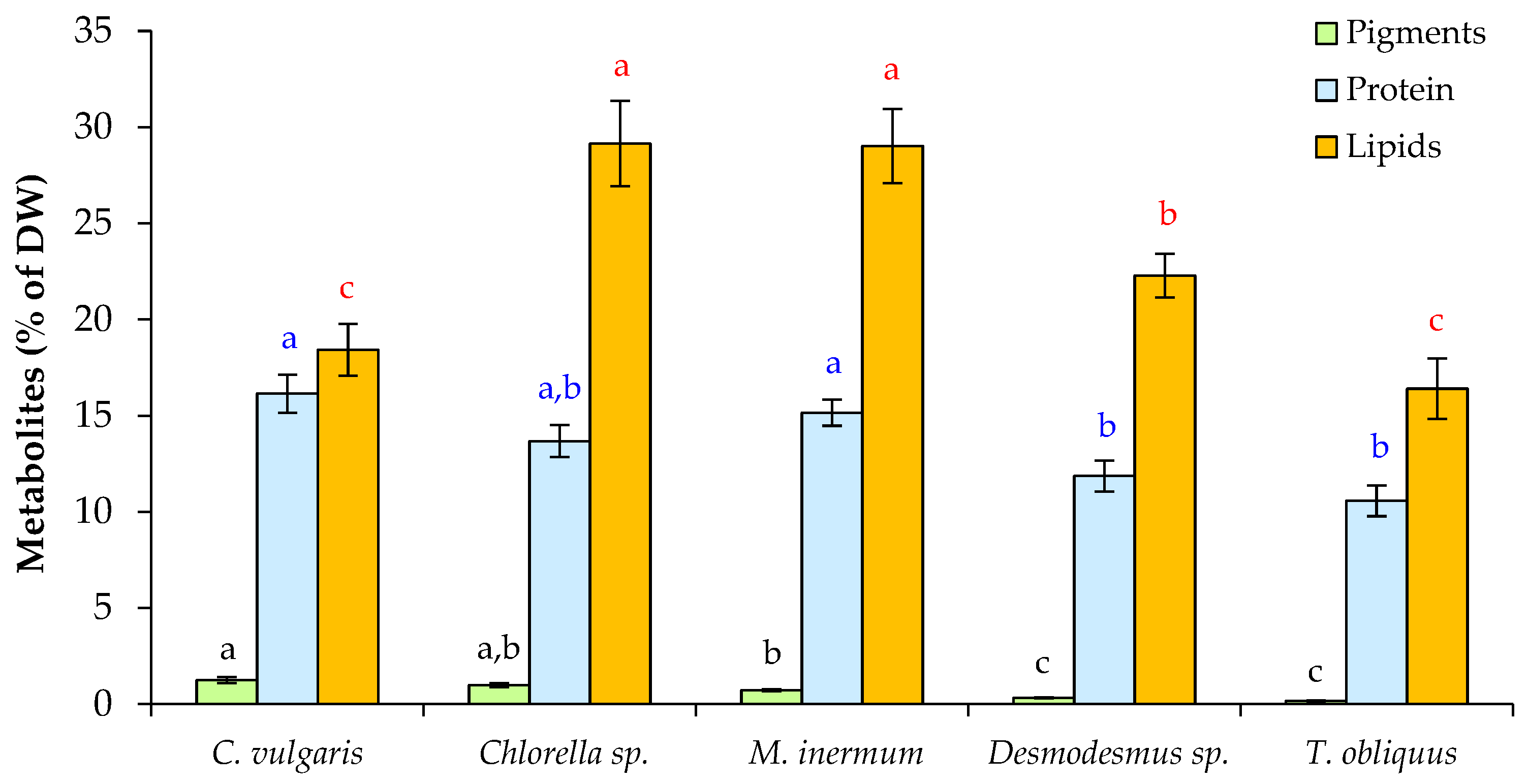

3.1. Growth and Productivity of Microalgae When Grown in FPWW

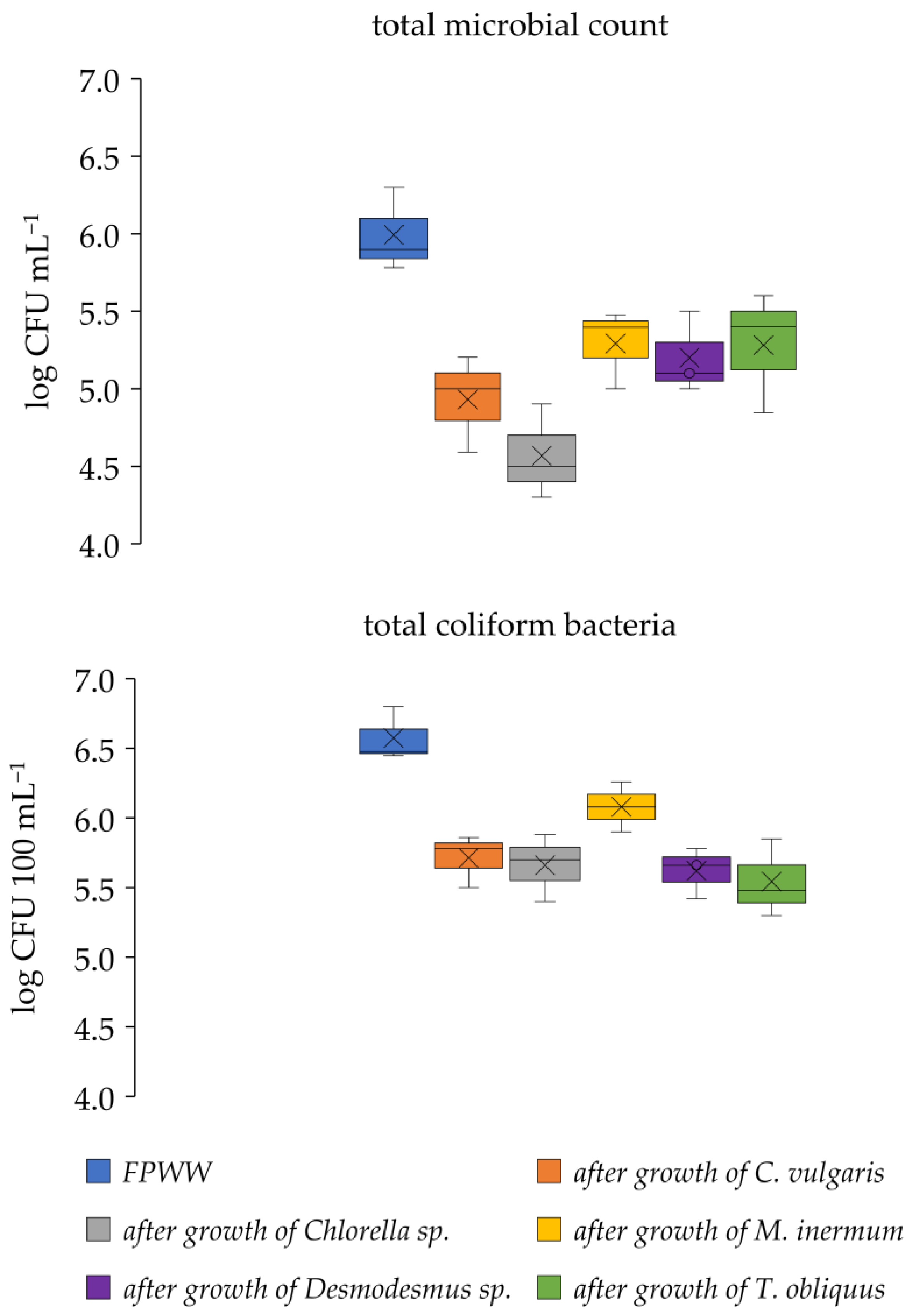

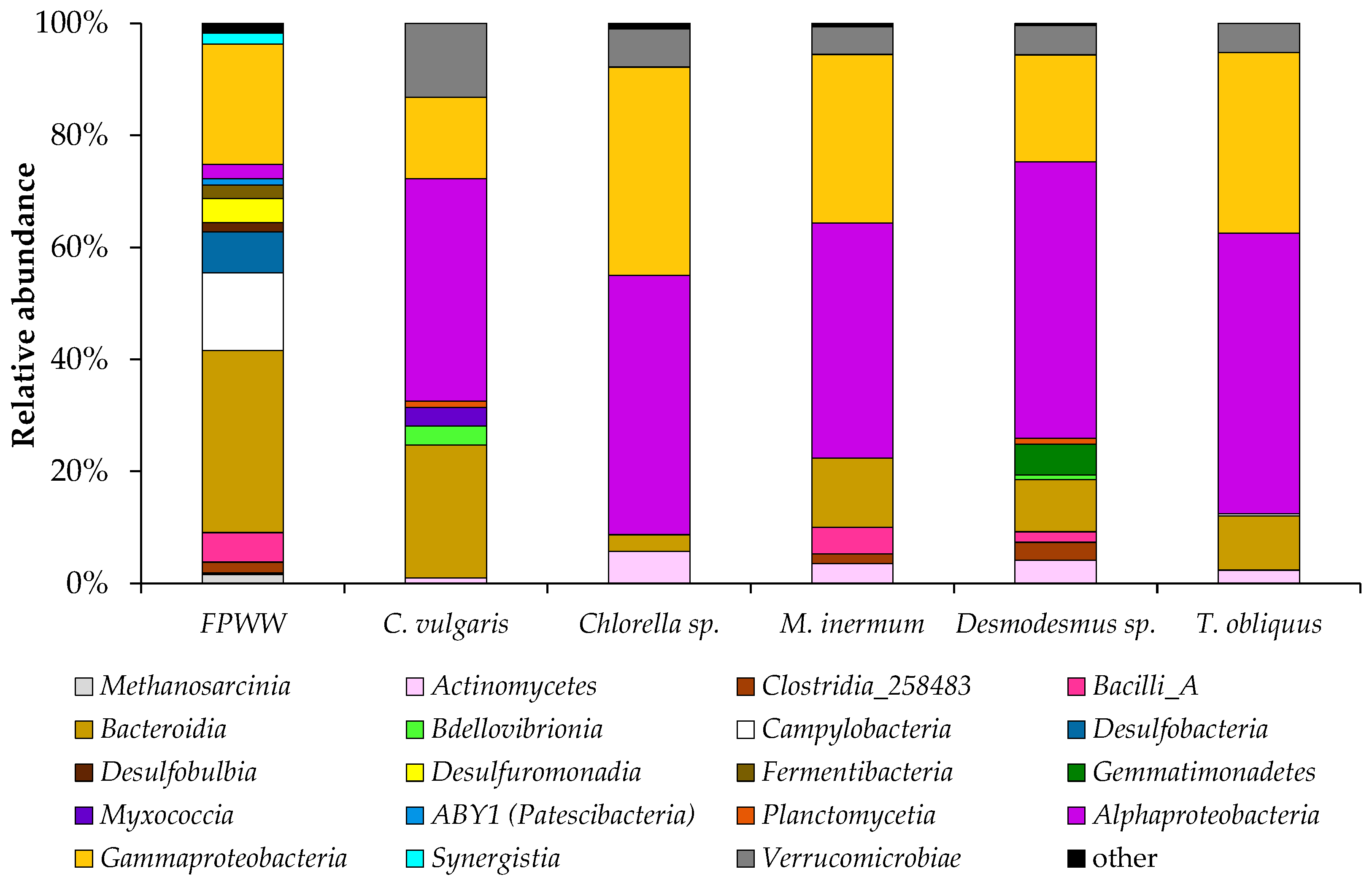

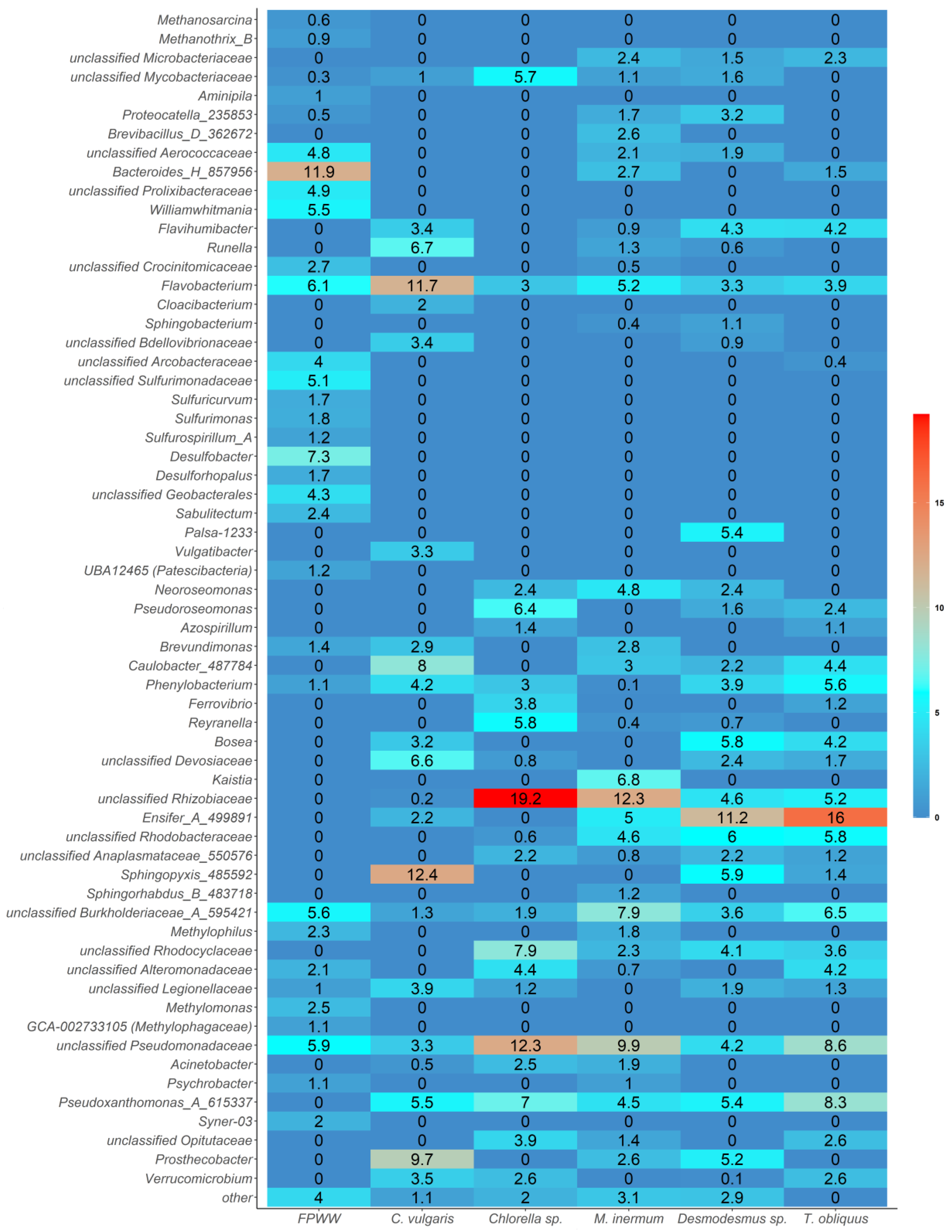

3.2. Microbial Community Structure of FPWW

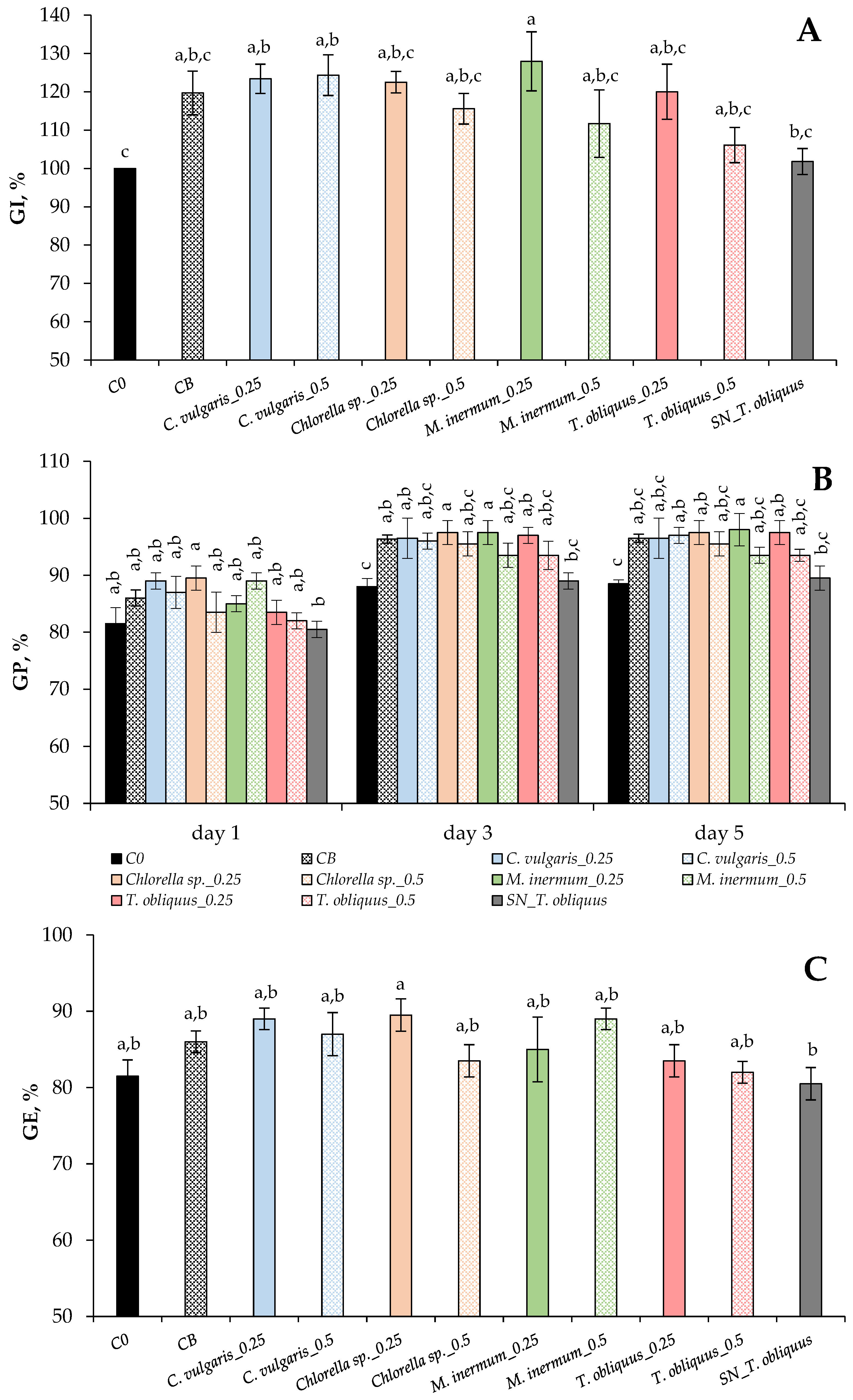

3.3. Biostimulant Activity of Microalgal/Bacterial Consortia

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Dawery, S.K.; AL-Yaqoubi, G.E.; Al-Musharrafi, A.A.; Harharah, H.N.; Amari, A.; Harharah, R.H. Treatment of fish-processing wastewater using polyelectrolyte and palm anguish. Processes 2023, 11, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honrado, A.; Miguel, M.; Ardila, P.; Beltrán, J.A.; Calanche, J.B. From waste to value: Fish protein hydrolysates as a technological and functional ingredient in human nutrition. Foods 2024, 13, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóvão, R.O.; Botelho, C.M.; Martins, R.J.E.; Loureiro, J.M.; Boaventura, R.A.R. Fish canning industry wastewater treatment for water reuse—A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliaga, P.; Felja, I.; Budiša, A.; Ivančić, I. The impact of a fish cannery wastewater discharge on the bacterial community structure and sanitary conditions of marine coastal sediments. Water 2019, 11, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Sasidharan, A. Seafood industry effluents: Environmental hazards, treatment and resource recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A. Wastewater treatment and reuse for sustainable water resources management: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.F.; Campo, R.; Val del Rio, A.; Amorim, C.L. Wastewater valorization: Practice around the world at pilot- and full-scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Lauritano, C.; Palma Esposito, F.; Riccio, G.; Rizzo, C.; de Pascale, D. Fish Waste: From Problem to Valuable Resource. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.M.; Hussain, S.M.; Ali, S.; Ghafoor, A.; Adrees, M.; Nazish, N.; Naeem, A.; Naeem, E.; Alshehri, M.A.; Rashid, E. Fish waste biorefinery: A novel approach to promote industrial sustainability. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 419, 132050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, T.; Ferreira, J.A.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Conversion of fish processing wastewater into fish feed ingredients through submerged cultivation of Aspergillus oryzae. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2021, 1, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiszewska, A.; Wierzchowska, K.; Nowak, D.; Wołoszynowska, M.; Zieniuk, B. Brine and post-frying oil management in the fish processing industry—A concept based on oleaginous yeast culture. Processes 2022, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urreta, I.; Suárez-Alvarez, S.; Virgel, S.; Orozko, I.; Aranguren, M.; Pinto, M. Recycling saline wastewater from fish processing industry to produce protein-rich biomass from a Thraustochytrid strain isolated in the Basque country. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 29, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom, A.P.; Jayakumar, J.S.; Biju, M.; Somarajan, J.; Ibrahim, M.A. Aquaculture wastewater treatment technologies and their sustainability: A review. Energy Nexus 2021, 4, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbari, S.; Sotaniemi, V.-H.; Suokas, M.; Taipale, S.; Leiviskä, T. Microalgae technology for polishing chemically-treated fish processing wastewater. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 24, 101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmann, F.; Dietze, S.; Ackermann, J.U.; Bley, T.; Walther, T.; Steingroewer, J.; Krujatz, F. Microalgae wastewater treatment: Biological and technological approaches. Eng. Life Sci. 2019, 19, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Bulynina, S.S.; Yureva, K.A.; Ziganshin, A.M. Optimization of photoautotrophic growth regimens of Scenedesmaceae alga: The influence of light conditions and carbon dioxide concentrations. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, H.M.; Salgado, E.M.; Nunes, O.C.; Pires, J.C.M.; Esteves, A.F. Microalgae systems—Environmental agents for wastewater treatment and further potential biomass valorisation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 337, 117678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Ziganshin, A.M. Influence of nutrient medium composition on the redistribution of valuable metabolites in the freshwater green alga Tetradesmus obliquus (Chlorophyta) under photoautotrophic growth conditions. BioTech 2025, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Yureva, K.A.; Ziganshin, A.M. Poultry slaughterhouse wastewater treatment by green algae: An eco-friendly restorative process. Environments 2025, 12, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.; Ali, S.S.; Ramadan, H.; El-Aswar, E.I.; Eltawab, R.; Ho, S.-H.; Elsamahy, T.; Li, S.; El-Sheekh, M.M.; Schagerl, M.; et al. Microalgae-based wastewater treatment: Mechanisms, challenges, recent advances, and future prospects. Environ. Sci. Ecotech. 2023, 13, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremia, E.; Ripa, M.; Catone, C.M.; Ulgiati, S. A review about microalgae wastewater treatment for bioremediation and biomass production—A new challenge for Europe. Environments 2021, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Lu, Q.; Fan, L.; Zhou, W. A Review on the use of microalgae for sustainable aquaculture. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, P.; Dutta, N.; Bhattacharya, S. Application of microalgae in wastewater treatment with special reference to emerging contaminants: A step towards sustainability. Front. Anal. Sci. 2024, 4, 1513153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Kazmi, S.F.; Irshad, M.; Bilal, M.; Hafeez, F.; Ahmed, J.; Shaheedi, S.; Nazir, R. Microalgae-assisted treatment of wastewater originating from varied sources, particularly in the context of heavy metals and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Water 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhzadeh, N.; Soltani, M.; Heidarieh, M.; Ghorbani, M. Role of dietary microalgae on fish health and fillet quality: Recent insights and future prospects. Fishes 2024, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Hu, Q. Microalgae as feed sources and feed additives for sustainable aquaculture: Prospects and challenges. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 16, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Kumar, R.; Neha, Y.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as next generation plant growth additives: Functions, applications, challenges and circular bioeconomy-based solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1073546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alling, T.; Funk, C.; Gentili, F.G. Nordic microalgae produce biostimulant for the germination of tomato and barley seeds. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglisi, I.; Barone, V.; Fragalà, F.; Stevanato, P.; Baglieri, A.; Vitale, A. Effect of microalgal extracts from Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus quadricauda on germination of Beta vulgaris seeds. Plants 2020, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollo, L.; Norici, A. Biostimulant potential of three Chlorophyta and their consortium: Application on tomato seeds. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-López, E.; Ruíz-Nieto, A.; Ferreira, A.; Acién, F.G.; Gouveia, L. Biostimulant potential of Scenedesmus obliquus grown in brewery wastewater. Molecules 2020, 25, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Gouveia, L.; Gonçalves, M. Bioremediation of cattle manure using microalgae after pre-treatment with biomass ash. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 14, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Padilla, B.L.; Romero-Villegas, G.I.; Sánchez-Estrada, A.; Cira-Chávez, L.A.; Estrada-Alvarado, M.I. Effect of marine microalgae biomass (Nannochloropsis gaditana and Thalassiosira sp.) on germination and vigor on bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Seeds “Higuera”. Life 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Bulynina, S.S.; Ziganshin, A.M. Comparison of the photoautotrophic growth regimens of Chlorella sorokiniana in a photobioreactor for enhanced biomass productivity. Biology 2020, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucconi, F.; Forte, M.; Monac, A.; De Beritodi, M. Biological evaluation of compost maturity. Biocycle 1981, 22, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.K.M.M.; Kato-Noguchi, H. Phytotoxic activity of Ocimum tenuiflorum extracts on germination and seedling growth of different plant species. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 676242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, S.; Xue, Q.; Tylkowska, K. Effects of seed priming on germination and health of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 2002, 30, 451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Jin, W.; Li, Z.; Wei, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, C.; Qin, C.; Chen, Y.; Tu, R.; Zhou, X. Cultivation of microalgae for lipid production using municipal wastewater. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 155, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagerl, M.; Siedler, R.; Konopáčová, E.; Ali, S.S. Estimating biomass and vitality of microalgae for monitoring cultures: A roadmap for reliable measurements. Cells 2022, 11, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shao, S.; He, Y.; Luo, Q.; Zheng, M.; Zheng, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, M. Nutrients removal from piggery wastewater coupled to lipid production by a newly isolated self-flocculating microalga Desmodesmus sp. PW1. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 302, 122806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Shao, Y.; Geng, Y.; Mushtaq, R.; Yang, W.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, G. Advanced treatment of secondary effluent from wastewater treatment plant by a newly isolated microalga Desmodesmus sp. SNN1. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1111468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Barboza, J.; Herrera-Rengifo, K.; Aguirre-Bravo, A.; Ramírez-Iglesias, J.R.; Rodríguez, R.; Morales, V. Pig slaughterhouse wastewater: Medium culture for microalgae biomass generation as raw material in biofuel industries. Water 2022, 14, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani Condori, M.A.; Mamani Condori, M.; Villas Gutierrez, M.E.; Choix, F.J.; García-Camacho, F. Bioremediation potential of the Chlorella and Scenedesmus microalgae in explosives production effluents. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 171004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedane, D.T.; Asfaw, S.L. Microalgae and co-culture for polishing pollutants of anaerobically treated agro-processing industry wastewater: The case of slaughterhouse. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2023, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onay, M.; Aladag, E. Production and use of Scenedesmus acuminatus biomass in synthetic municipal wastewater for integrated biorefineries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 15808–15820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarponi, P.; Frongia, F.; Cramarossa, M.R.; Roncaglia, F.; Arru, L.; Forti, L. Bioremediation of basil pesto sauce-manufactured wastewater by the microalgae Chlorella vulgaris Beij. and Scenedesmus sp. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göncü, S.; Şimşek Uygun, B.; Atakan, S. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal from wastewater using Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus quadricauda microalgae with a batch bioreactor. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 11877–11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Betancur, J.J.; Herrera-Ochoa, M.S.; García-Martínez, J.B.; Urbina-Suarez, N.A.; López-Barrera, G.L.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Bryan, S.J.; Zuorro, A. Application of Chlorella sp. and Scenedesmus sp. in the bioconversion of urban leachates into industrially relevant metabolites. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, Y.; Zaharieva, M.M.; Kroumov, A.D.; Najdenski, H. Antimicrobial and ecological potential of Chlorellaceae and Scenedesmaceae with a focus on wastewater treatment and industry. Fermentation 2024, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, A.; Hajinajaf, N.; Tavakoli, O.; Sarrafzadeh, M.H. Cultivation of mixed microalgae using municipal wastewater: Biomass productivity, nutrient removal, and biochemical content. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 18, e2586. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Amenorfenyo, D.K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, C.; Huang, X. Cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris in membrane-treated industrial distillery wastewater: Growth and wastewater treatment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 770633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrojo, M.Á.; Regaldo, L.; Calvo Orquín, J.; Figueroa, F.L.; Abdala Díaz, R.T. Potential of the microalgae Chlorella fusca (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) for biomass production and urban wastewater phycoremediation. AMB Expr. 2022, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.F.; Salgado, E.M.; Vilar, V.J.P.; Gonçalves, A.L.; Pires, J.C.M. A growth phase analysis on the influence of light intensity on microalgal stress and potential biofuel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 311, 118511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.C.; Lombardi, A.T. Chlorophylls in microalgae: Occurrence, distribution, and biosynthesis. In Pigments from Microalgae Handbook, 1st ed.; Jacob-Lopes, E., Queiroz, M., Zepka, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Sun, H.; Deng, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, F. Carotenoid production from microalgae: Biosynthesis, salinity responses and novel biotechnologies. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolganyuk, V.; Belova, D.; Babich, O.; Prosekov, A.; Ivanova, S.; Katserov, D.; Patyukov, N.; Sukhikh, S. Microalgae: A promising source of valuable bioproducts. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, H.; Yusoff, F.M.; Banerjee, S.; Khatoon, H.; Shariff, M. Availability and utilization of pigments from microalgae. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2209–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Deng, X.; Ji, X.; Liu, N.; Cai, H. Sources, dynamics in vivo, and application of astaxanthin and lutein in laying hens: A review. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 13, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruales, E.; Bellver, M.; Álvarez-González, A.; Carvalho Fontes Sampaio, I.; Garfi, M.; Ferrer, I. Carotenoids and biogas recovery from microalgae treating wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 428, 132427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.S.; Maia, C.; Sousa, S.A.; Tavares, T.; Pires, J.C.M. Amino acid and carotenoid profiles of Chlorella vulgaris during two-stage cultivation at different salinities. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Cui, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Ge, B.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Wei, Z.; et al. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology strategies for producing high-value natural pigments in microalgae. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 68, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit; Dahiya, D.; Ghosh, U.K.; Nigam, P.S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Food industries wastewater recycling for biodiesel production through microalgal remediation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.M.; Galal, H.R.; Mousa, A.S.H.; Farghl, A.A.M. Coupling wastewater treatment, biomass, lipids, and biodiesel production of some green microalgae. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 35492–35504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silambarasan, S.; Logeswari, P.; Sivaramakrishnan, R.; Incharoensakdi, A.; Kamaraj, B.; Cornejo, P. Scenedesmus sp. strain SD07 cultivation in municipal wastewater for pollutant removal and production of lipid and exopolysaccharides. Environ. Res. 2023, 218, 115051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmayadi, A.; Lu, P.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Leong, Y.K.; Yen, H.W.; Chang, J.S. Integrating anaerobic digestion and microalgae cultivation for dairy wastewater treatment and potential biochemicals production from the harvested microalgal biomass. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 133057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, C. Nutrient removal and microalgal biomass production from different anaerobic digestion effluents with Chlorella species. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, I.; Tyagi, K.; Ahamad, F.; Bhutiani, R.; Kumar, V. Assessment of bacterial community structure, associated functional role, and water health in full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plants. Toxics 2025, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Ibragimov, E.M.; Ilinskaya, O.N.; Ziganshin, A.M. Bacterial communities inhabiting toxic industrial wastewater generated during nitrocellulose production. Biologia 2016, 71, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziganshina, E.E.; Mohammed, W.S.; Ziganshin, A.M. Microbial diversity of the produced waters from the oilfields in the Republic of Tatarstan (Russian Federation): Participation in biocorrosion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, R.; Oon, Y.-L.; Oon, Y.-S.; Bi, Y.; Mi, W.; Song, G.; Gao, Y. Diverse interactions between bacteria and microalgae: A review for enhancing harmful algal bloom mitigation and biomass processing efficiency. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Ramanan, R.; Cho, D.-H.; Oh, H.-M.; Kim, H.-S. Role of Rhizobium, a plant growth promoting bacterium, in enhancing algal biomass through mutualistic interaction. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 69, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, C.; Wang, T.; Woldemicael, A.; He, M.; Zou, S.; Wang, C. Nitrogen supplemented by symbiotic Rhizobium stimulates fatty-acid oxidation in Chlorella variabilis. Algal Res. 2019, 44, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Li, Y.; Tian, K.; Wang, M.; Tan, D.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Enhanced photosynthetic CO2 fixation in mutualistic Chlorella sp. and Mesorhizobium loti co-cultures. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 163671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Yin, Y.; Xi, L.; Ge, B.; Qin, S. Enhanced biomass and lipid production by co-cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris with Mesorhizobium sangaii under nitrogen limitation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 32, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.H.; Ramanan, R.; Heo, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.H.; Oh, H.M.; Kim, H.S. Enhancing microalgal biomass productivity by engineering a microalgal–bacterial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 175, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, J.; Wan, N.; Huang, W. Efficiency and mechanism of moving bed bacterial-algal biofilm reactor (MB-BA-BR) in treating simulated coal chemical wastewater. Fuel 2025, 394, 135176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Je, K.W.; Lee, K.; Jung, S.-E.; Choi, T.-J. Growth promotion of Chlorella ellipsoidea by co-inoculation with Brevundimonas sp. isolated from the microalga. Hydrobiologia 2008, 598, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, T.; Mori, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Ike, M.; Morikawa, M. Growth promotion of giant duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza (Lemnaceae) by Ensifer sp. SP4 through enhancement of nitrogen metabolism and photosynthesis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2022, 35, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Naeimpoor, F. Single and co-cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Efficient nutrient removal and lipid/starch formation by photoperiodic co-culture. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 436, 132983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.M.; Scheer, D.; Hou, Y.; Hotter, V.S.; Komor, A.J.; Aiyar, P.; Scherlach, K.; Vergara, F.; Yan, Q.; Loper, J.E.; et al. The bacterium Pseudomonas protegens antagonizes the microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii using a blend of toxins. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 5525–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Mori, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Toyama, T. Isolation and characterization of bacteria from natural microbiota regrown with Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in synthetic co-cultures. Algal Res. 2025, 86, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillas-España, A.; Ruiz-Nieto, Á.; Lafarga, T.; Acién, G.; Arbib, Z.; González-López, C.V. Biostimulant capacity of Chlorella and Chlamydopodium species produced using wastewater and centrate. Biology 2022, 11, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 6.9 ± 0.08 |

| TS (%) | 0.16 ± 0.1 |

| VS (%) | 0.11 ± 0.1 |

| NH4+–N (mg L−1) | 62.5 ± 3.7 |

| PO43−–P (mg L−1) | 10.7 ± 1.2 |

| SO42−–S (mg L−1) | 8 ± 1.7 |

| NO2−–N (mg L−1) | trace amounts |

| NO3−–N (mg L−1) | trace amounts |

| Urea | trace amounts |

| Strain | DW, g L−1 | Biomass Productivity, g L−1 day–1 | Ash-Free DW, g L−1 | NH4+/PO43−/ SO42− Removal, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. vulgaris SB-M4 | 1.42 ± 0.10 d | 0.28 ± 0.02 d | 1.35 ± 0.09 d | 100 |

| Chlorella sp. EE-P5 | 1.61 ± 0.05 c,d | 0.32 ± 0.01 c,d | 1.53 ± 0.05 c,d | 100 |

| M. inermum EE-M2 | 1.70 ± 0.09 c | 0.34 ± 0.02 c | 1.61 ± 0.09 c | 100 |

| Desmodesmus sp. EE-M8 | 2.21 ± 0.09 a | 0.44 ± 0.02 a | 2.12 ± 0.08 a | 100 |

| T. obliquus EZ-B11 | 1.96 ± 0.06 b | 0.39 ± 0.01 b | 1.89 ± 0.06 b | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bulynina, S.S.; Ziganshina, E.E.; Terentev, A.D.; Ziganshin, A.M. Treatment of Wastewater from the Fish Processing Industry and Production of Valuable Algal Biomass with a Biostimulating Effect. Phycology 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010002

Bulynina SS, Ziganshina EE, Terentev AD, Ziganshin AM. Treatment of Wastewater from the Fish Processing Industry and Production of Valuable Algal Biomass with a Biostimulating Effect. Phycology. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleBulynina, Svetlana S., Elvira E. Ziganshina, Artem D. Terentev, and Ayrat M. Ziganshin. 2026. "Treatment of Wastewater from the Fish Processing Industry and Production of Valuable Algal Biomass with a Biostimulating Effect" Phycology 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010002

APA StyleBulynina, S. S., Ziganshina, E. E., Terentev, A. D., & Ziganshin, A. M. (2026). Treatment of Wastewater from the Fish Processing Industry and Production of Valuable Algal Biomass with a Biostimulating Effect. Phycology, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/phycology6010002