Abstract

Light and antioxidant systems play a crucial role in the life activities of algal cells. This study investigates the algicidal efficacy of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) against the harmful algal bloom (HAB)-forming dinoflagellate Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu, with a focus on the modulating roles of light conditions and iron ion environments. Within 180 min, dark-adapted cells showed 78% greater viability loss than light-exposed ones, and Fe3O4 nanoparticles synergistically enhanced H2O2 inhibition. Imaging and cytometry confirmed cell damage, including membrane rupture. Mechanistically, H2O2 penetrated cells, induced severe oxidative stress, suppressed photosynthesis, and compromised membrane integrity. Darkness likely exacerbated toxicity by depleting antioxidant reserves. This study elucidates an apoptosis-like pathway underlying H2O2-induced cell death and highlights the critical influence of ambient light on treatment efficiency. These findings reveal an apoptosis-like death pathway and highlight ambient light’s critical role, suggesting that optimized nighttime H2O2 application with nanomaterial synergists could improve HAB control strategies.

1. Introduction

Due to eutrophication, climate anomalies, altered ocean currents, and species invasion via ballast water discharge, HABs occur frequently in coastal waters worldwide, posing significant threats to marine fisheries, aquaculture, and ecological balance [1,2]. Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu (P. donghaiense Lu), a bloom-forming dinoflagellate prevalent in the East China Sea (especially near the Yangtze River estuary), causes annual HABs from April to August [3]. Between 2008 and 2022, 81 outbreaks covering 49,407 km2 were recorded [4]. Furthermore, P. shikokuense and P. donghaiense should be regarded as junior synonyms of P. obtusidens [5]. During HABs, rapid proliferation of algae depletes dissolved oxygen, limiting growth and causing mortality of other marine organisms [6,7], which can lead to growth restriction and even death [8,9]. Additionally, daytime migration of HABs to surface waters reduces water transparency, preventing light-dependent photosynthesis in aquatic plants, which will impede the normal metabolic processes of aquatic organisms and even cause their death [10,11]. As a common non-toxic HAB, understanding P. donghaiense Lu’s inactivation is crucial. However, effective, economical, feasible, and environmentally safe HAB control remains challenging.

Chemical agents such as copper sulfate (CuSO4), sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ozone (O3) and modified clay exhibit algicidal properties. NaClO and CuSO4 inactivated Cochlodinium polykrikoides with 72-h EC50 values of 0.584 and 0.633 mg L−1, respectively, inducing ROS generation and pigment degradation [12]. However, their environmental persistence and toxicity to non-target organisms limit their application. O3 inactivated C. polykrikoides (3.0 × 103 cells/mL) within 300 s via oxidative damage, but produces carcinogenic bromate and disinfection by-products (DBPs) [13]. Modified clay could control the algae population of Prorocentrum donghaiense (P. donghaiense) through indirect effects such as oxidative stress, while the maximum mortality rates reached 50% [14]. Various doses of ozone were used to pre-ozonate Microcystis aeruginosa and Anabaena flosaquae at concentrations of 2.5 × 105 cells mL−1 and 1.5 × 106 cells mL−1 [15].

For H2O2 inactivation of five marine species (Corophium volutator, Artemia salina, Brachionus plicatilis, Dunaliella teriolecta, and Skeletonema costatum), with H2O2 concentration of 145 mg/L and a exposure time of longer than 50 d, a 50% likelihood exists that 95% of the species will be affected [16]. Previous studies have used H2O2 to treat Scripsiella trochoidea (S. trochoidea), with the result that H2O2 (100 mg/L) exhibited 87.2% inactivation efficiency after 5 min treatment [17]. A concentration of 50 mg·L−1 of H2O2 was brought into an entire creek system with a special device for optimal dispersal of the added H2O2 over 24 h, with the result that 99.8% Alexandrium ostenfeldii cells and pellicle cysts were inactivated and concentrations of PSP in the water were reduced below local regulatory levels of 15 μg·L−1 [18]. A water harrow setup, dispersing 2 mg L−1 (60 mu M) of H2O2 homogeneously into the entire water volume of the lake with a special dispersal device, inactivated cyanobacterial population by 99% within a few days [19]. Dispersal of 14 mg/L H2O2 reduced P. parvum biomass and prymnesin concentrations, with limited negative impact on other phytoplankton [20]. A key advantage of H2O2 is its lack of persistent chemical residues, though high doses and prolonged treatments increase operational costs.

In the context of algal inactivation technologies based on Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), such as photocatalysis, the Fenton process, O3/H2O2, and UV/H2O2, hydroxyl radicals (•OH) have been identified as the key agent responsible for efficient inactivation [21,22,23]. Beyond these methods, ferrate(VI) can serve as a pre-oxidant to enhance conventional Fe(II) coagulation, thereby improving the removal of Microcystis aeruginosa. For instance, one study applied 20 µM ferrate(VI) combined with 80 µM Fe(II), achieving effective coagulation enhancement. However, the dosage of ferrate(VI) requires careful optimization, as higher concentrations treating Microcystis aeruginosa at 2.0 × 106 cells/mL can achieve an inactivation rate of 88.4% but may also cause significant damage to algal cells [24]. This confirms the potential cell disruption effect of high-dose ferrate, indicating that precise dosing control is crucial in practical algal removal applications.

On the other hand, ozonation also serves as an effective method for algal inactivation. Research shows that a relatively low ozone dose (0.2 mg·min/L) can inactivate Microcystis aeruginosa (2.5 × 105 cells/mL) and Anabaena flosaquae (1.5 × 106 cells/mL) [15]. However, this technique may introduce notable environmental trade-offs: post-ozonation, the formation of disinfection by-products (DBPs) increases significantly, with trihalomethanes (THM) and haloacetic acids (HAA) rising by 174% and 65%, respectively [15]. These results suggest that while ozonation effectively inactivates algae, it may concurrently elevate environmental risks, raising concerns about its overall environmental friendliness.

This study investigates the algicidal efficacy of H2O2 against the HAB-forming dinoflagellate P. donghaiense Lu, with a focus on the modulating roles of light conditions and iron ion environments. In this study, the process of H2O2 apoptosis of algal cells was simulated in different iron-containing environments to further understand the mechanism of H2O2 on marine algae, which provides a theoretical basis for understanding the self-extinction of HABs and emergency management methods for HABs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algae Cultivation

Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu was obtained from Xiamen University Algae Collection Center, which was collected from Yangtze River Estuary in the East China Sea and is a harmful alga known to cause red tide [25]. The alga has an average cell size of 15~25 μm long and 8~15 μm broad, which shows an oval shape.

P. donghaiense Lu were cultured in f/2 culture medium [26], f/2 culture medium with twice the concentration of iron ions and f/2 culture medium without iron ions at 22 °C under 2200 lax light intensity with a light–dark cycle of 12 h/12 h in an incubator (Safe, Shanghai, China). After 20 days of culturing, P. donghaiense were at the plateau phase of growth with a final cell yield of 6 × 104 cells/mL. To simulate an algae bloom in high algae density, the algae cultured at the stationary phase of growth were diluted to achieve a final cell density of in total 1 × 104 cells/mL using seawater from Xiamen Bay.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

Five experimental groups and one control (n = 3) were established:

(a) Control, growth in f/2 medium; (b) 1 mg L H2O2, (c) 1 mg L H2O2 + 4 mL Fe3O4 NPs (10–30 nm, 25% in H2O), (d) 4 mL Fe3O4 NPs (10–30 nm, 25% in H2O), (e) 1 mg L H2O2 in Fe-enriched f/2, (f) 1 mg L H2O2 in Fe-depleted f/2.

H2O2 and Fe3O4 NPs (Haohe, Xiamen, China) were added to algae samples. Treatments were applied to algae pre-adapted to dark or light conditions. To evaluate the influence of illumination on H2O2 inactivation of algae, after a 12-h dark culture period, one group was immediately treated with H2O2 under visible light, while the other group was exposed to H2O2 following 3 h of incubation under illumination. Samples were quenched with Na2S2O3 (saturated concentration) (Haohe, Xiamen, China) post-exposure, shown in Figure S1.

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. TRO Concentration Determination

TRO concentration is the abbreviation of the total reactive oxidants, which include •OH, H2O2 and other active oxygen. The total reactive oxidant in the liquid was combined with potassium iodide, which react with N, N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DPD, 1 g/L) (Haohe, Xiamen, China) to emit light at the wavelength of 525 nm. The absorbance of the samples was measured with an Agilent G6860A spectrophotometer (Agilent Instruments Ltd., Santa Clara, CA, USA) with the US EPA’s Standard Method 330.5 [27].

2.3.2. Counts and Identification of Algal Cellular Viability

Flow cytometry (Accuri C6, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used for all fluorescence measurements and the activity of algae cells at a fixed wavelength of 488 nm. Channel FL1 (530 nm) collected SYTOX Green (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) fluorescence emitted by nonviable cells; simultaneously, channel FL3 (675 nm) collected red chlorophyll fluorescence emitted by viable cells. According to the fluorescence measurements, viable and nonviable cells could be distinguished. All the samples were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Haohe, Xiamen, China) and then loaded for analysis. Meanwhile, algae were counted with flow cytometry.

2.3.3. Cell Surface Morphology Analysis

The morphology of Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu was detected with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, SU-70, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm cellular integrity. Prior to observation, the algal suspension was concentrated through centrifugation and then fixed overnight in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution (Haohe, Xiamen, China). Following fixation, the samples were rinsed with PBS and centrifuged again to further enrich the algal cells. These enriched cells were then adhered to coverslips with an approximate area of 25 mm2. The adhered samples were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (Haohe, Xiamen, China) overnight at 4 °C, and were gradually dehydrated with ethanol. The slides with samples were immersed in ethanol for gradient dehydration, dried using a critical point dryer (Leica EM CPD300, Wetzlar, Germany), and coated with platinum using a metal sputtering device (JEOL JFC-1600, Tokyo, Japan). Finally, the prepared samples were observed and photographed using a field emission scanning electron microscope.

2.3.4. Photosynthetic Parameters

Different chlorophyll fluorescence parameters are obtained by irradiating algae with different excitation lights, which can reflect the physiological state of the algal photosynthesis system.

The photosynthetic activity of the algae was detected by pulse amplitude modulation (PHYTO-PAM, Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). Fv/Fm is maximal photochemical efficiency, determined as:

Fv/Fm = (Fm − F0)/Fm

The minimum fluorescence (F0) was obtained after dark adaptation for 10 min and the maximum fluorescence (Fm) was obtained after the first saturation pulse.

Fv/Fm reflects algae maximal photochemical efficiency, which proves algal cell viability.

2.3.5. Measurement of Intracellular •OH and ROS

The intracellular •OH and ROS levels were quantified using fluorescent probes 3′-(p-hydroxyphenyl) fluorescein (HPF, Invitrogen, USA) and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Invitrogen, USA). For detection, 1.5 μL HPF (10 mM) or 15 μL DCFH-DA (1 mM) was immediately added to 1.5 mL of algae suspension, and incubated in darkness for 30 min. Subsequently, the algae were pelleted by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 5 min, washed and resuspended in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to a final volume of 200 μL for flow cytometric analysis. Measurements were performed using a 488 nm excitation wavelength with emission detection at 530 nm. Data acquisition and analysis were conducted using the BD Accuri software platform (C6 version), with further processing performed in FlowJo V10.4.

3. Results

3.1. Cell Viabilities of Algae with H2O2 Exposure

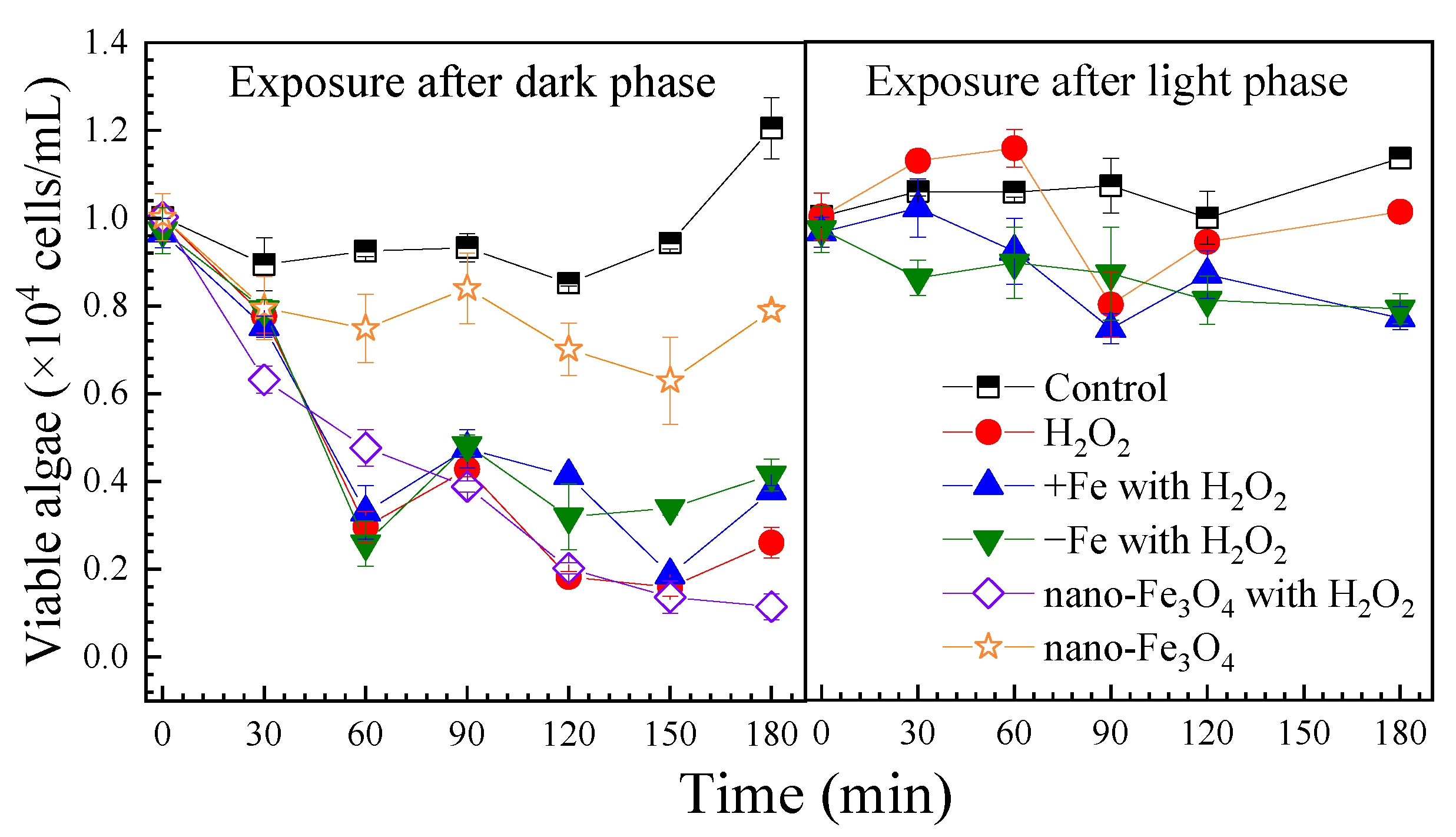

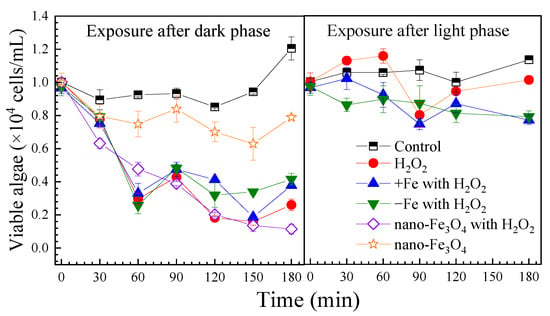

H2O2 exposure caused a rapid decrease in viable algal cells to 3.0 × 103 cells/mL within 60 min, followed by regrowth to 2.6 × 103 cells/mL by 180 min. In the control group, the viable algal cell count increased to 1.2 × 104 cells/mL after 180 min. Neither iron-excess nor iron-depleted treatments enhanced algae inhibition (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of H2O2 on cell viabilities of the algae under the different exposure conditions. Notes: Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu after a 7-day batch culture with normal f/2 medium, iron-excess treatment (+Fe) and iron-depleted treatment (−Fe), exposed to H2O2 (1 mM). For all exposure conditions, the initial algae content was 1.0 × 104 cells/mL.

Following light exposure, control group algal cells increased to 1.1 × 104 cells/mL by 180 min. With H2O2 treatment, viable cells dropped to 8.0 × 103 cells/mL at 90 min then recovered to 1.0 × 104 cells/mL by 180 min. Under both iron-excess and iron-depleted conditions, inhibition was stronger, with final counts of 7.7 × 103 and 7.9 × 103 cells/mL, respectively. Viable algae decreased significantly over time (p < 0.05) (Figure S2).

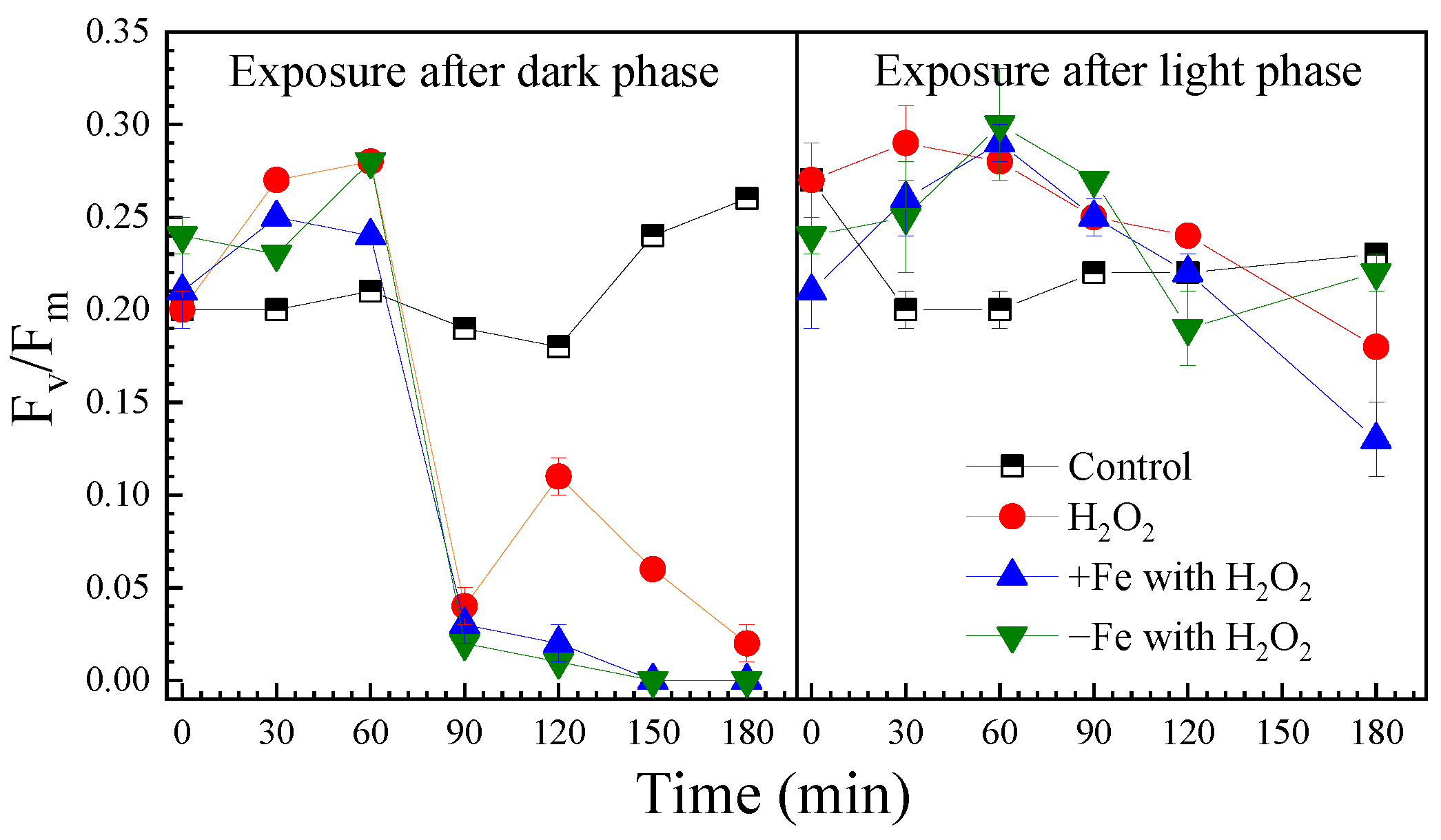

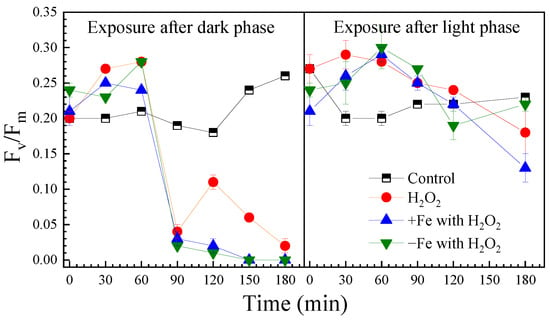

3.2. Variation in Photosynthetic Activity of Algal Cells

H2O2 can diffuse into cells, causing structural damage to intracellular components [28]. In algal cells, H2O2 has the ability to cause oxidation damage to photosynthesis [29,30,31]. The Fv/Fm value is the maximal photochemical efficiency, an indicator of the underlying growth ability of algal cells [32]. The Fv/Fm values under the different exposure conditions are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The effect of H2O2 on Fv/Fm of algal cells under the different exposure conditions.

After the dark phase, the initial Fv/Fm was 0.20 in the control and increased to 0.26 after 180 min illumination. H2O2 exposure initially raised Fv/Fm within 60 min, but then it sharply declined to 0.01 by 90 min. Both iron-excess and iron-depleted treatments reduced Fv/Fm to 0 after 180 min of H2O2 exposure. Fe3O4 nanoparticles interfered with the measurements, preventing data acquisition.

In the control group after light-phase H2O2 exposure, the initial Fv/Fm was 0.27 and declined to 0.18 after 180 min. Under iron-excess and iron-depleted conditions, the initial values were lower at 0.13 and 0.22, respectively. H2O2 exhibited a biphasic effect—transient photosynthetic stimulation followed by sustained inhibition after 60 min, which corresponded with the timing of significant cell inactivation shown in Figure 1.

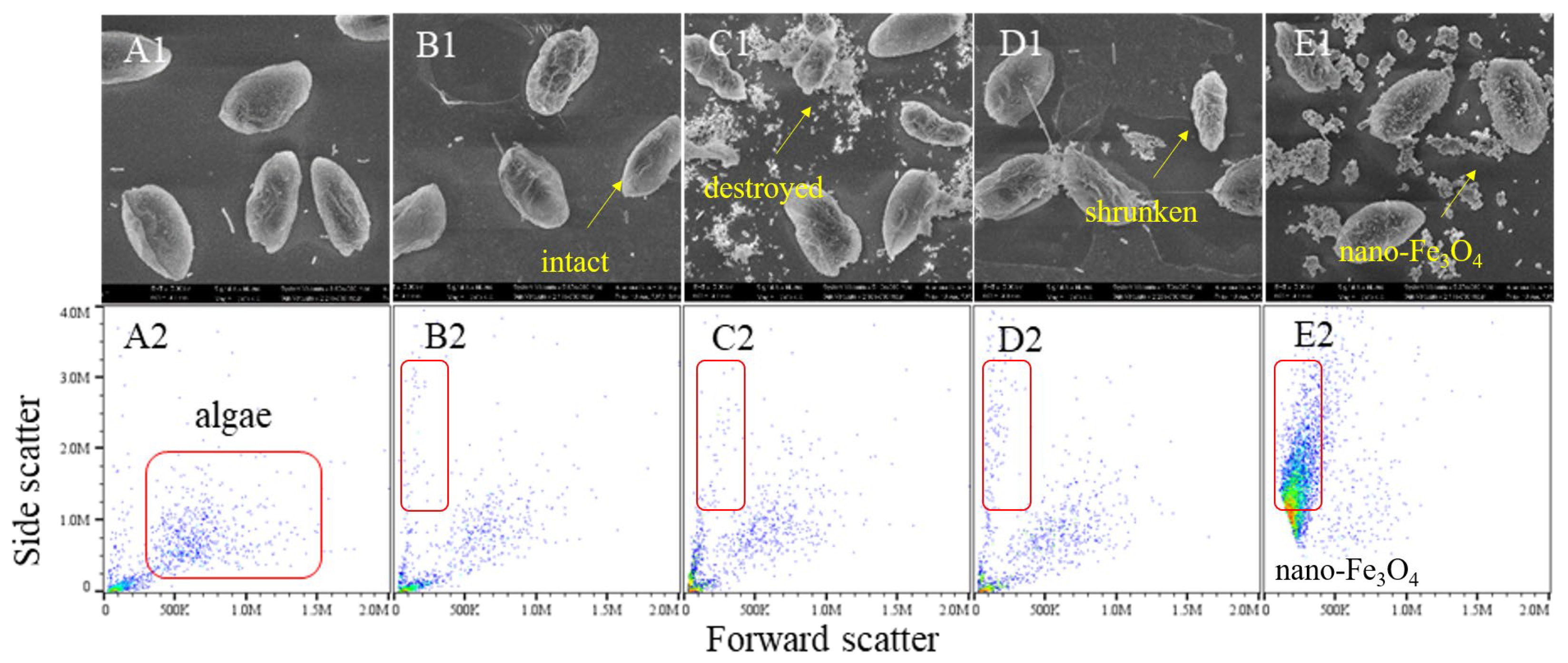

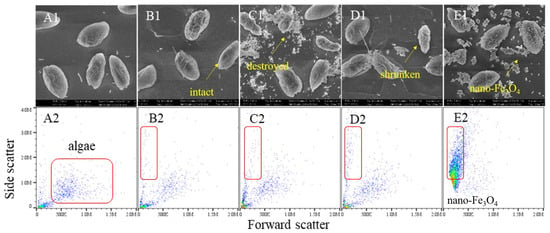

3.3. Variation in Cell Morphology of Algae

Scanning electron microscopy and flow cytometry revealed significant H2O2-induced morphological changes (Figure 3). Control cells maintained a plump spindle shape, while after 180 min of H2O2 exposure, widespread cell shrinkage, rupture, and reduced side scatter were observed. Both iron-excess and iron-depleted conditions caused similar damage. Notably, iron-excess treatment produced flocculent substances, and Fe3O4 nanoparticles attached to cell surfaces, inducing lysis-indicating ROS generation and flocculation potential by the nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

The effect of H2O2 on cell morphology of the algae under the different exposure conditions. Notes: (A1–E1) SEM images of the control algae, the H2O2 group algae, the Fe iron-treatment (+Fe) group algae, the iron-depleted treatment (−Fe) group algae and the nano-Fe3O4 group algae. (A2–E2) Flow cytometry results of the control algae, the H2O2 group algae, the Fe iron-treatment (+Fe) group algae, the iron-depleted treatment (−Fe) group algae and the nano-Fe3O4 group algae.

Flow cytometry analysis revealed two critical parameters: elevated forward scatter (FS) correlates with higher intracellular granularity, while increased side scatter (SS) reflects larger cell size. Compared to the control, H2O2-exposed cells exhibited decreased FS/SS profiles, indicating reduced cellular content and diminished cell volume. Notably, Fe3O4 nanoparticles caused severe signal interference during flow cytometric detection due to nanoparticle aggregation.

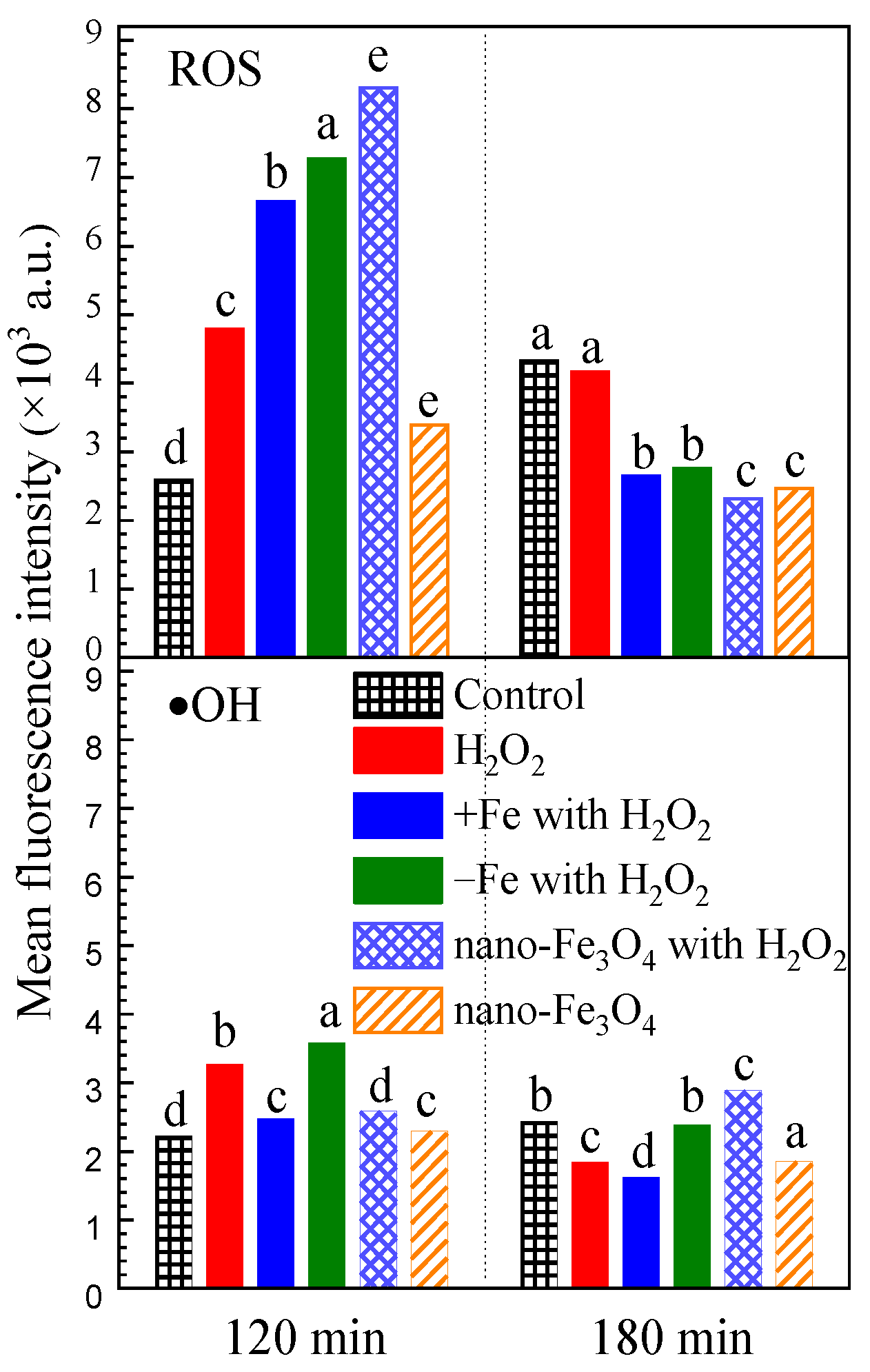

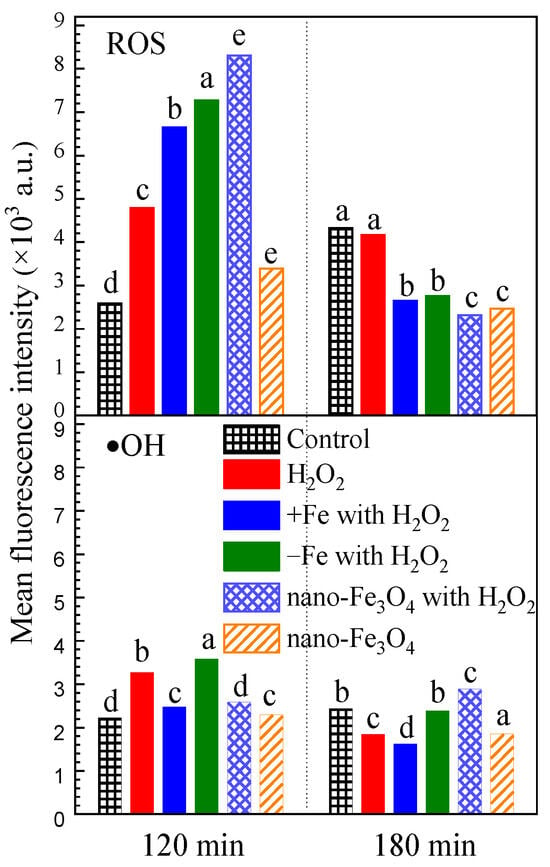

3.4. Accumulation of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species

For H2O2 exposure after the dark phase, the H2O2 exposure induced intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and hydroxyl radical (•OH) to increase to 1.85 times and 1.47 times the control group after 120 min (Figure 4). Iron-excess treatment, iron-depleted treatment and nano-Fe3O4 treatment all had a promoting effect on intracellular ROS accumulation, but not on •OH accumulation. However, after 180 min, the intracellular ROS and •OH reduced to the lower level of the control group.

Figure 4.

The effect of H2O2 on intracellular reactive oxygen species under the different exposure conditions. Notes: The mean fluorescein was detected from 1000 algal cells. The letters a, b, c, d and e indicate significant differences between groups, p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

4.1. Causes of Inhibition of Algal Activity

Dark-adapted algae showed rapid viability loss (78% within 180 min) with H2O2 exposure (Figure 1). Fe3O4 NPs enhanced this effect, while iron-altered media had minimal impact. Light-adapted cells exhibited higher resistance, with viability recovering after 180 min. According to the experimental results, iron-excess treatment, iron-depleted treatment and Fe3O4 nanoparticles had no outstanding effect on the inactivation effect of H2O2 on P. donghaiense Lu. However, Fe3O4 nanoparticles significantly potentiated the inhibitory effect of H2O2. Notably, when algae were exposed solely to Fe3O4 nanoparticles, growth was suppressed but the viable cell count remained stable. In addition, the results in this paper showed that the cells of P. donghaiense Lu were more sensitive to H2O2 after the dark phase, which conform with previous findings. Erbes et al. found that Chlamydomonas reinhardtii exposed to H2O2 in light for 180 min had no dramatic effects on cell viability, while exposure to H2O2 in darkness resulted in a clear dose-related decrease in cell viability [33]. Volpert et al. found that cells of Thalassiosira pseudonana in the dark exhibited higher sensitivity to oxidative stress than cells in light, and suggested that the dark-dependent sensitivity to oxidative stress was a result of a depleted pool of reduced glutathione that accumulated during the light period [34]. However, information on algae sensitivity to oxidative stress under dark conditions is very limited.

4.2. The Mechanisms Influencing the Photosynthetic System

Photosynthesis is a complex process that involves the conversion of light energy into chemical energy for cellular metabolism. The results of this research showed that the destruction of the photosynthetic system is an important condition for H2O2 to lead to cell death, which demonstrates greater sensitivity to H2O2 than cellular viability. In addition, previous studies have shown that H2O2 can influence photosynthesis at various levels. When algal cells are exposed to H2O2, H2O2 in the water can enter the cell through the water channel in the cell membrane, but only if enough H2O2 is accumulated to play a destructive role. This biphasic response suggests initial PSII stimulation followed by irreversible damage. At low concentrations, H2O2 can enhance the efficiency of photosystem II (PSII], the primary photosynthetic apparatus, by accelerating the electron transport rate and decreasing nonphotochemical quenching [1,14].

Additionally, H2O2 can inhibit photosynthesis by damaging PSII and other photosynthetic pigments like chlorophyll and carotenoids. The severity of inhibition depends on the duration and concentration of H2O2 treatment, as well as the algal species and growth conditions [29]. Chloroplasts showed a rate of H2O2 generation of 5 μmol·mg chlorophyll−1·hr−1 under illumination. In the cellular environment, the decomposition of H2O2, catalyzed by reduced metal ions (Fe2+), results in the formation of hydroxyl radicals, which can affect a variety of macromolecules, such as proteins, fatty acids, and nucleic acids. This leads to decreased photosynthetic efficiency, photoinhibition, and accumulation of ROS [32]. H2O2 concentrations ≥ 200 mg L−1 negatively affected photosystem II (PSII) in coralline alga Lithothamnion soriferum immediately after exposure, which was observed through a significant decline in Fv/Fm [35]. Meanwhile, reaction in darkness enhances the inhibitory effect of H2O2 on algae. This is consistent with previous studies [36]. Exposure of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells to H2O2 in light for 2 h had no dramatic effects on cell viability, while exposure to H2O2 in darkness resulted in a clear dose-related decrease of cell viability [33]. Light can regulate the photosynthetic activity of algal cells and impact the intracellular redox state. Under light conditions, the active processes of photosynthesis and electron flow lead to a more reduced state in cells [37]. In contrast, under dark conditions, the absence of light-induced reactions causes a decline in electron flow and a shift towards a more oxidized state. This could be a reason why H2O2 is more likely to induce cell inactivation under dark conditions.

4.3. Causes of Changes in Algal Surface Structure

Numerous studies have shown that exposure of algae to oxidants can alter cellular morphology and even lead to cell lysis. Cell membrane damage was observed on K. mikimotoi and P. donghaiense surfaces post ClO2 treatment [38]. The mechanism of ClO2 inactivation is that ClO2 attacks cell wall and plasma membrane glycoproteins, glycolipids, or certain amino acids [39]. Cell surface damage to M. aeruginosa was also shown via SEM after 5 min of treatment with UV/H2O2 treatment, which led to the release of IOM [40]. H2O2 is a relatively strong oxidant with an oxidation potential of 1.76 V, which can easily pass through cell membranes by diffusion. Inside the cells, H2O2 induces oxidative stress, which causes damage to proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, and thereby changes in cell morphology and compromised cell viability.

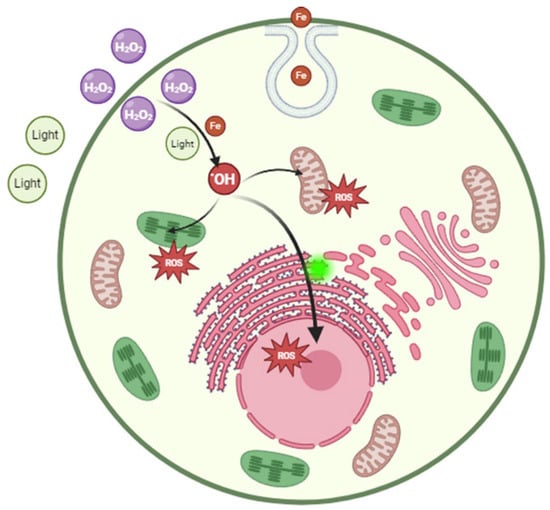

4.4. Mechanism of Algae Inhibition by Hydrogen Peroxide

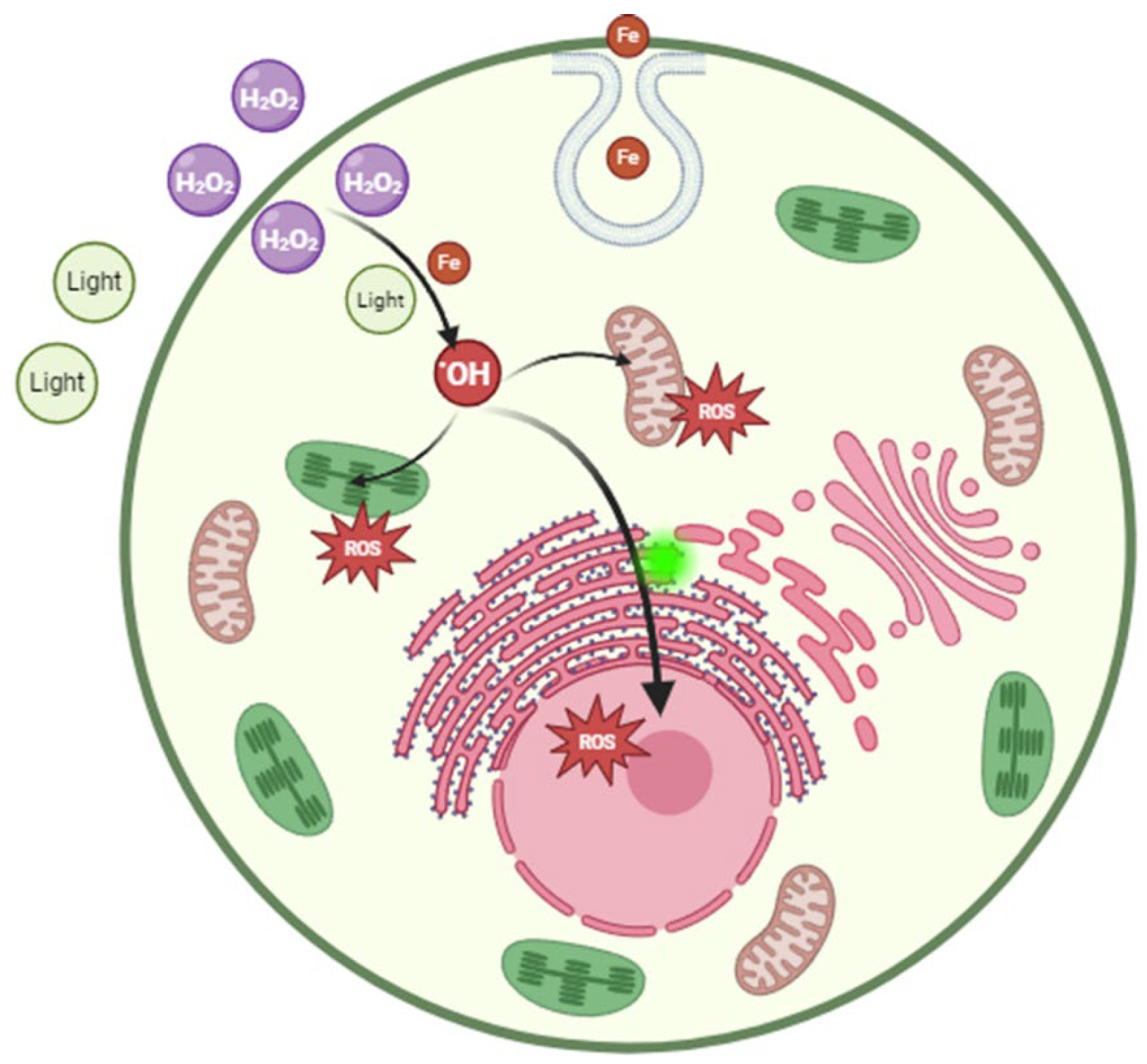

H2O2 can penetrate the cell membrane and enter the cell, leading to an elevation of intracellular ROS levels. This can trigger oxidative stress and tissue damage [41]. Apoptosis is an important mechanism of H2O2 lethal algal cells. H2O2 could inhibit M. aeruginosa growth after 24~48 h of treatment, which induced several classic parameters associated with apoptosis in cells, such as membrane deformation, cytoplasmic vacuolation, chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation and increasing caspase-3-like activity [42]. Although it has been found that H2O2 can cause algal cell death by inducing apoptosis-like pathways, it is generally believed that cell membrane rupture is the main mechanism of cell death by conventional oxidants. Moreover, H2O2 can induce reactions between the lipid substances and proteins present with intracellular iron ions, giving rise to •OH and other free radicals [43,44]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the time required for H2O2 treatment to eliminate algal cells typically ranges from a few hours to several days [18]. This may depend on the accumulation of H2O2 within the algal cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Biological mechanism of H2O2 on Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu.

The oxidizing properties, rapid degradation, environmentally friendly degradation products (water and oxygen), and the fact that it can be produced electrochemically make H2O2 a promising candidate for algicide of HABs and ballast water [30]. Based on the results of this study, when using H2O2 as an algicide, the impact of light should be taken into consideration. Since algae produce H2O2 and other ROS during photosynthesis, they possess mechanisms to regulate intracellular oxidative stress. The data presented provide support for the idea that algae have evolved mechanisms that allow maintenance of a certain level of H2O2. H2O2 released from chloroplasts under high light is transported along the cell with the cytoplasmic flow. Ice algae can efficiently photo-acclimate to increased irradiance by modifying their photosynthetic machinery and light-harvesting pigments over hours to days [45,46]. This regulatory effect of algal cells is related to photoprotection. Light, as a regulatory factor, will affect the redox state of cells [47,48,49].

5. Conclusions

HABs have appeared frequently and pose a significant threat to marine ecology and security. H2O2 is a potential algicide due to its eco-friendly nature, environmental protection qualities, and strong oxidizing properties. This investigation revealed an apoptosis-like mechanism underlying H2O2-induced cell death in algal cultures. H2O2 exposure in darkness induced a rapid 78% reduction in algal cell viability within 180 min, significantly exceeding the effect observed under light conditions. Fe3O4 nanoparticles synergistically enhanced H2O2 efficacy, achieving significant cell inactivation after 180 min. Mechanistically, H2O2, after penetrating algal cells, induced intracellular reactive oxygen species accumulation, triggered oxidative stress, suppressed photosynthetic activity, and altered cell membrane permeability. To deal with toxic HABs, this method can effectively prevent the leakage of toxins. This method is suitable for HABs with a relatively small outbreak area and where the toxic algae species are the dominant ones. It enables the HABs to gradually disappear. These effects were exacerbated under dark adaptation, likely due to depletion of antioxidant reserves and cessation of photoprotective processes. This study provides theoretical insights into optimizing H2O2-based algal mitigation strategies, highlighting nighttime application and nanomaterial synergism to improve cost-effectiveness and environmental safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/phycology6010022/s1, Figure S1: Fluorescence intensity of ROS and OH detected by flow cytometry. Figure S2: The effect of H2O2 on cell viabilities of the algae under the different exposure conditions. Figure S3: Fluorescence intensity of ROS and •OH detected by flow cytometry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z.; methodology, Q.Z. and P.L.; validation, P.L. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, P.L. and Z.Z.; data curation, P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L. and Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, P.L., Z.Z. and Q.Z.; supervision, Q.Z.; project administration, P.L. and Q.Z.; funding acquisition, P.L. and Q.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2024M752764, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2021M691868, and Huzhou Science and Technology Foundation, grant number 2025GY075.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HABs | Harmful algae blooms |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

References

- Gu, H.F.; Wu, Y.R.; Lu, S.H.; Lu, D.D.; Tang, Y.Z.; Qi, Y.Z. Emerging harmful algal bloom species over the last four decades in China. Harmful Algae 2022, 111, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, A.; Escalera, L.; Aligizaki, K.; Fernández-Tejedor, M.; Ismael, A.; Montresor, M.; Mozetic, P.; Tas, S.; Totti, C. Toxic marine microalgae and noxious blooms in the Mediterranean Sea: A contribution to the Global HAB Status Report. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.R.; Zheng, J.J.; Lu, D.D.; Dai, X.F.; Wang, R.F.; Zhu, Y.L.; Park, B.S.; Li, C.P.; Kim, J.H.; Guo, R.Y.; et al. Mapping the main harmful algal species in the East China Sea (Yangtze River estuary) and their possible response to the main ecological status and global climate change via a global vision. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.M.; Tang, Y.Z.; Gobler, C.J. Harmful algal blooms in China: History, recent expansion, current status, and future prospects. Harmful Algae 2023, 129, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Li, Z.; Mertens, K.N.; Seo, M.H.; Gu, H.F.; Lim, W.A.; Yoon, Y.H.; Soh, H.Y.; Matsuoka, K. Prorocentrum shikokuense Hada and P. donghaiense Lu are junior synonyms of P. obtusidens Schiller, but not of P. dentatum Stein (Prorocentrales, dinophyceae). Harmful Algae 2019, 89, 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresnan, E.; Arévalo, F.; Belin, C.; Branco, M.A.C.; Cembella, A.D.; Clarke, D.; Correa, J.; Davidson, K.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Lozano, R.F.; et al. Diversity and regional distribution of harmful algal events along the Atlantic margin of Europe. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, C.H.; Bates, S.S.; Martin, J.L.; Haigh, N.; Howland, K.L.; Lewis, N.I.; Locke, A.; Peña, A.; Poulin, M.; Rourke, W.A.; et al. Three decades of Canadian marine harmful algal events: Phytoplankton and phycotoxins of concern to human and ecosystem health. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purz, A.K.; Hodapp, D.; Moorthi, S.D. Dispersal, location of bloom initiation, and nutrient conditions determine the dominance of the harmful dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella: A meta-ecosystem study. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 3928–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.Y.; Fan, H.Y.; Yao, H.; Wang, C.Y. Recent progress and prospect of graphitic carbon nitride-based photocatalytic materials for inactivation of Microcystis aeruginosa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Waal, D.B.; Gsell, A.S.; Harris, T.; Paerl, H.W.; de Senerpont Domis, L.N.; Huisman, J. Hot summers raise public awareness of toxic cyanobacterial blooms. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.J.; Yoo, Y.D.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, T.H.; Seong, K.A.; Kang, N.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.; Yih, W.H. Red tides in Masan Bay, Korea in 2004–2005: I. Daily variations in the abundance of red-tide organisms and environmental factors. Harmful Algae 2013, 30, S75–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenezer, V.; Lim, W.A.; Ki, J.S. Effects of the algicides CuSO4 and NaOCl on various physiological parameters in the harmful dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 2357–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, M.S.; Park, N.B.; Lee, C. Control of the red tide dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides by ozone in seawater. Water Res. 2017, 109, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.N.; Yu, Z.M.; He, L.Y.; Zhu, J.N.; Cao, X.H.; Song, X.X. Programmed cell death induced by modified clay in controlling Prorocentrum donghaiense bloom. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 109, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coral, L.A.; Zamyadi, A.; Barbeau, B.; Bassetti, F.J.; Lapolli, F.R.; Prévost, M. Oxidation of Microcystis aeruginosa and Anabaena flos-aquae by ozone: Impacts on cell integrity and chlorination by-product formation. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2983–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.G.D.; Ebbens, E.; Jak, R.G.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Time and concentration dependency in the potentially affected fraction of species: The case of hydrogen peroxide treatment of ballast water. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.S.; Jiang, W.J.; Zhang, Y.; Lim, T.M. Inactivation of dinoflagellate Scripsiella trochoidea in synthetic ballast water by advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Technol. 2015, 36, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burson, A.; Matthijs, H.C.P.; de Bruijne, W.; Talens, R.; Hoogenboom, R.; Gerssen, A.; Visser, P.M.; Stomp, M.; Steur, K.; van Scheppingen, Y.; et al. Termination of a toxic Alexandrium bloom with hydrogen peroxide. Harmful Algae 2014, 31, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijs, H.C.P.; Visser, P.M.; Reeze, B.; Meeuse, J.; Slot, P.C.; Wijn, G.; Talens, R.; Huisman, J. Selective suppression of harmful cyanobacteria in an entire lake with hydrogen peroxide. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1460–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasser, I.; Aykut, T.O.; Crucitti-Thoo, R.; Pasztaleniec, A.; Konkel, R.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Combating Toxic Blooms of Prymnesium parvum: Hydrogen Peroxide Influence on the Haptophyte, Other Phytoplankton Taxa, and Concentrations of Prymnesins Under Experimental Conditions. Water 2025, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, V.J.; Malato, S.; Dionysiou, D.D. Advanced oxidation technologies: Advances and challenges in Iberoamerican countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 759–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. TiO2 photocatalyst for water treatment applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Lin, Q.; Li, C.; He, G.; Deng, Y. Impacts of pre-oxidation on the formation of disinfection byproducts from algal organic matter in subsequent chlor(am)ination: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 141955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.H.; Zhao, Z.W.; Liu, J.; Peng, W.; Peng, X.; Han, Y.T.; Xiao, P. Removal of Microcystis aeruginosa and control of algal organic matters by potassium ferrate(VI) pre-oxidation enhanced Fe(II) coagulation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 36, 1587–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effiong, K.; Hu, J.; Xu, C.C.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Yu, S.M.; Tang, T.; Huang, Y.Z.; Lu, Y.L.; Li, W.; Zeng, J.N.; et al. 3-Indoleacrylic acid from canola straw as a promising antialgal agent—Inhibition effect and mechanism on bloom-forming Prorocentrum donghaiense. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 178, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillard, R.R.; Ryther, J.H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. 1. Cyclotella nana hustedt, and detonula confervacea (cleve) gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 1962, 8, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Chlorine, Total Residual (Spectrophotometric, DPD), Method 330.5; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1978.

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.H.; Hendry, G.A.F. Iron-catalyzed oxygen radical formation and its possible contribution to drought damage in 9 native grasses and 3 cereals. Plant Cell Environ. 1991, 14, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontani, J.F. Visible light-dependent degradation of lipidic phytoplanktonic components during senescence: A review. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.T.; Bai, M.D.; Bai, X.Y.; Yang, B.; Bai, M.D.; Zhou, X.J. Studies of the effect of hydroxyl radicals on photosynthesis pigments of phytoplankton in ship’s ballast water. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2004, 7, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll fluorescence—A practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbes, M.; Wessler, A.; Obst, U.; Wild, A. Detection of primary DNA damage in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by means of modified microgel electrophoresis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1997, 30, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpert, A.; van Creveld, S.G.; Rosenwasser, S.; Vardi, A. Diurnal fluctuations in chloroplast GSH redox state regulate susceptibility to oxidative stress and cell fate in a bloom-forming diatom. J. Phycol. 2018, 54, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, E.; Parsons, A.E.; Escobar-Lux, R.H.; Freytet, F.; Agnalt, A.L.; Samuelsen, O.B.; Husa, V. Effect of sea lice chemotherapeutant hydrogen peroxide on the photosynthetic characteristics and bleaching of the coralline alga Lithothamnion soriferum. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 247, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermilyea, A.W.; Dixon, T.C.; Voelker, B.M. Use of H218O2 To Measure Absolute Rates of Dark H2O2 Production in Freshwater Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3066–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X.; Chen, J.; Che, H.A.; Wang, P.F.; Ao, Y.H. Flexible g-C3N4-based photocatalytic membrane for efficient inactivation of harmful algae under visible light irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 601, 154270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.Y.; Bian, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.B.; Wei, C.Z.; Bai, M.D. Biological effects of hydroxyl radical inactivation for typical red tide algae Alexandrium tamarense. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shao, Y.; Gao, N.; Li, L.; Deng, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, S. Effect of chlorine dioxide on cyanobacterial cell integrity, toxin degradation and disinfection by-product formation. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482–483, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, R. Cyanobacterium removal and control of algal organic matter (AOM) release by UV/H2O2 pre-oxidation enhanced Fe(II) coagulation. Water Res. 2018, 131, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potukuchi, A.; Addepally, U.; Sindhu, K.; Manchala, R. Increased total DNA damage and oxidative stress in brain are associated with decreased longevity in high sucrose diet fed WNIN/Gr-Ob obese rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gan, N.Q.; Li, J.; Sedmak, B.; Song, L.R. Hydrogen peroxide induces apoptotic-like cell death in Microcystis aeruginosa (Chroococcales, Cyanobacteria) in a dose-dependent manner. Phycologia 2012, 51, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashi, Y.; Tomita, K.; Kuwahara, Y.; Roudkenar, M.H.; Roushandeh, A.M.; Igarashi, K.; Nagasawa, T.; Nishitani, Y.; Sato, T. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes aquaporin expression that controls hydrogen peroxide permeability and ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgenidou, E.; Konstantinou, I.; Fytianos, K.; Poulios, I. Oxidation of two organophosphorous insecticides by the photo-assisted Fenton reaction. Water Res. 2007, 41, 2015–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, T.; Murata, A.; Taguchi, S. Responses of pigment composition of the marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii to silicate availability during dark survival and recovery. Plankton Benthos Res. 2011, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynska, P.; Jemiola-Rzeminska, M.; Strzalka, K. Photosynthetic Pigments in Diatoms. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5847–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrou, K.; Doblin, M.A.; Ralph, P.J. Heterogeneity in the photoprotective capacity of three Antarctic diatoms during short-term changes in salinity and temperature. Mar. Biol. 2011, 158, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Milios, E. Establishment and survival of Pinus brutia Ten. seedlings over the first growing season in abandoned fields in central Cyprus. Plant Biosyst. 2012, 146, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.V. Nonphotochemical Chlorophyll Fluorescence Quenching: Mechanism and Effectiveness in Protecting Plants from Photodamage. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.