Abstract

Conventional petroleum-based protective coatings release high levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and contribute to resource depletion, urging the development of environmentally responsible alternatives. Among the bio-based candidates, microalgae and Cyanobacteriophyta have recently gained attention for their ability to produce diverse biopolymers and pigments with intrinsic protective functionalities. However, existing literature has focused mainly on algal biofuels and general biopolymers, leaving a major gap in understanding their application as sustainable coating materials. This review addresses that gap by providing the first integrated assessment of algae-based protective coatings. It begins by defining abiotic and biotic surface degradation mechanisms, including microbiologically influenced corrosion, to establish performance benchmarks. The review then synthesizes recent findings on key algal components, including alginate, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and phycocyanin, linking biochemical composition to functional performance, techno-economic feasibility, and industrial scalability. It evaluates their roles in adhesion strength, UV stability, corrosion resistance, and antifouling activity. Reported performance metrics include adhesion strengths of 2.5–3.8 MPa, UV retention above 85% after 2000 h, and corrosion rate reductions of up to 40% compared with polyurethane systems. Furthermore, this study introduces the concept of carbon-negative, multifunctional coatings that simultaneously protect infrastructure and mitigate environmental impacts through CO2 sequestration and pollutant degradation. Challenges involving biomass variability, processing costs (>USD 500/ton), and regulatory barriers are critically discussed, with proposed solutions through hybrid cultivation and biorefinery integration. By bridging materials science, environmental engineering, and sustainability frameworks, this review establishes a foundation for transforming algae-based coatings from laboratory research to scalable, industrially viable technologies.

1. Introduction

The global construction sector continues to expand rapidly due to accelerating urbanization and economic growth. While this development supports housing and infrastructure demands, it also contributes heavily to environmental degradation. The construction industry accounts for nearly one third of global primary energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, making it a key driver of climate change and resource depletion [1]. For instance, China alone is projected to experience urban migration of more than 300 million people by 2050, increasing the need for sustainable infrastructure solutions [2]. Extending the lifespan of construction materials through effective surface protection has therefore become an important strategy for reducing environmental impacts.

Conventional protective coatings are mainly derived from petroleum-based polymers and solvents. These coatings pose serious ecological and health risks due to their high emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). In 2019, industrial coatings emitted over 28.8 Tg of VOCs, contributing to atmospheric pollution and increasing the risks of respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer [3,4]. Many of these systems contain synthetic polymers such as diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A (DGEBA), which are non-biodegradable and have a high carbon footprint throughout their life cycle [5].

To overcome these drawbacks, bio-based coatings derived from natural oils such as linseed and soybean have been explored. In addition to plant oils, biopolymers such as lignin, cellulose, and chitosan have recently gained attention as sustainable alternatives for surface protection [6]. However, these alternatives often lack the mechanical durability, chemical resistance, and scalability of petroleum based systems due to lower toughness and higher production costs [7]. Consequently, attention has shifted toward microalgae and cyanobacteria as renewable and versatile sources of coating materials [8].

Microalgal and cyanobacterial coatings offer dual benefits because they provide physical protection to surfaces while also contributing to atmospheric CO2 reduction through photosynthetic carbon fixation. These microorganisms produce a variety of functional compounds such as pigments, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and biopolymers that enhance ultraviolet (UV) resistance, mechanical strength, antimicrobial activity, and corrosion protection [9,10,11,12]. Recent innovations include latex algae biocomposites, which combine algae derived biopolymers with waterborne latex matrices to reduce petrochemical dependence and improve coating functionality [13].

Despite these advances, several barriers limit the widespread use of algae-based coatings. Variations in substrate adhesion, surface roughness, and chemical composition can reduce coating integrity [12], while mechanical resistance under industrial conditions often remains below conventional standards [14]. Additionally, high biomass processing costs, inefficient extraction methods, and lack of production standardization hinder scalability [15].

Most studies so far have examined individual algal components or small scale laboratory formulations, but their integration into industrially viable coating systems remains underexplored. Few have evaluated life cycle performance, cost competitiveness, or environmental benefits under real-world conditions. For instance, while algal pigments show strong UV blocking properties, direct comparisons with petroleum-based coatings in field environments are limited. Moreover, the overall carbon offset potential of algae-based coatings across their production and application phases has not been well quantified.

This review addresses these gaps by providing the first comprehensive synthesis of research on algae-based protective coatings. Uniquely, this study begins by explicitly defining the abiotic and biotic degradation mechanisms affecting infrastructure with a specific focus on microbiologically influenced corrosion caused by fungi and bacteria to establish the necessary performance benchmarks for bio coatings. It then connects biochemical composition, formulation strategies, mechanical performance, and techno economic feasibility. It introduces the emerging concept of carbon-negative multifunctional coating materials that not only protect surfaces but also contribute to CO2 sequestration and pollutant mitigation. By analyzing recent technological advances and industrial challenges, this study identifies future directions for improving mechanical robustness, reducing production costs, and enabling large scale implementation. The discussion is framed within the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), highlighting the potential of algae- and Cyanobacteriophyta-based coatings to drive the transition toward a low emission and resource efficient infrastructure future.

2. Surface Degradation Mechanisms in Infrastructure Materials

Infrastructure materials such as concrete, steel, and polymer-coated composites undergo continuous deterioration when exposed to environmental stressors. These degradation processes begin at the material surface, where physical, chemical, and biological interactions progressively weaken structural integrity. Because protective coatings must counteract these external stressors, understanding how degradation initiates and evolves is essential before evaluating any coating system, including algae-based coatings. This section synthesizes the dominant abiotic and biotic mechanisms affecting infrastructure surfaces and establishes the scientific foundation for Section 3. A consolidated overview is provided in Table 1, which summarizes the degradation mechanisms, effects, and key references.

2.1. Abiotic Degradation Mechanisms

Abiotic degradation results from non-living environmental factors such as UV radiation, temperature fluctuations, water exposure, and chemical pollutants. Although each stressor operates differently, they often interact in ways that accelerate deterioration and ultimately define the level of protection required from coating systems.

2.1.1. UV Radiation Induced Degradation

Ultraviolet radiation is one of the most pervasive abiotic drivers of surface deterioration. Prolonged UV exposure induces photochemical cleavage of polymer chains and generates reactive oxygen species that accelerate oxidation and surface embrittlement [16,17]. As coatings lose elasticity and color stability, microscopic cracks form, enabling water, oxygen, and ions to penetrate deeper into the underlying material. UV damage therefore becomes an initial trigger that opens pathways for additional deterioration caused by moisture, chemicals, and biological colonization.

2.1.2. Thermal Degradation and Temperature Cycling

Thermal fluctuations amplify the damage initiated by UV radiation. Differences in thermal expansion between coatings and substrates generate internal stresses during heating and cooling cycles [18]. These stresses promote crack growth, weaken interfacial bonding, and encourage delamination. Freeze–thaw cycles further intensify deterioration when water infiltrates UV weakened microcracks, freezes, and expands. The combined effect of UV exposure and temperature cycling reduces long-term coating adhesion and compromises mechanical stability.

2.1.3. Moisture, Humidity, and Water Penetration

Moisture acts as a central connector between multiple degradation mechanisms. Once microcracks form through UV and thermal processes, water quickly infiltrates the material matrix [18,19]. Humidity induces the hydrolysis of polymeric functional groups, reduces coating cohesion, and increases permeability. In concrete, water facilitates leaching, sulfate attack, and alkali silica reactions. In metals, it initiates under film corrosion. Moisture also enhances the transport of chloride ions, pollutants, and microorganisms, making it a critical factor that links abiotic and biotic deterioration.

2.1.4. Chemical Attack from Acidic, Alkaline, and Saline Environments

Chemical pollutants intensify the weaknesses created by UV, thermal, and moisture exposure. Acid rain alters surface pH and dissolves mineral phases. Chloride ions migrate through moisture induced pathways and initiate pitting corrosion in steel, even beneath partially intact coatings [20]. In concrete, alkaline conditions trigger expansive alkali silica reactions that widen cracks produced by earlier abiotic stressors. Chemical attack is therefore typically a secondary escalation mechanism that exploits pre-existing damage.

2.1.5. Mechanical Wear and Abrasion

Mechanical abrasion represents the physical counterpart to chemical attack. Particulate erosion, vehicular loads, and windborne debris directly remove surface layers and expose vulnerable substrates [17]. Abrasion also accelerates chemical attack by removing oxidized surface films and increasing material reactivity. In environments containing sand, salt crystals, or industrial particulates, abrasion amplifies the rate at which other degradation processes operate and often marks the final stage of rapid surface deterioration.

2.1.6. Synergistic Interactions Among Abiotic Factors

Abiotic stressors rarely act independently. UV exposure increases the susceptibility of surfaces to moisture ingress. Thermal cycling widens pathways created by UV and chemical attack. Moisture supports ionic transport and promotes subsequent corrosion. As described in [16], these interactions produce nonlinear degradation rates that are significantly higher than the sum of individual processes. This explains why conventional coatings often fail prematurely and highlights the need for multifunctional protective systems.

2.2. Biotic Degradation Mechanisms (Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion)

Although abiotic factors often initiate surface deterioration, biological colonization frequently becomes the dominant long-term degradation mechanism. Microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, algae, and lichens form biofilms on compromised surfaces and drive biochemical reactions that can exceed the severity of purely abiotic damage.

2.2.1. Bacterial Induced Deterioration

Bacteria contribute significantly to the deterioration of concrete, metals, and polymeric coatings. Aerobic bacteria secrete organic acids that dissolve mineral phases, while anaerobic sulfate reducing bacteria produce hydrogen sulfide that promotes severe corrosion [19]. Silicate bacteria further dissolve silicate components in concrete and accelerate erosion. These processes are most active in environments where moisture, cracking, and temperature fluctuations have already weakened surface coatings, demonstrating the dependency of biotic degradation on preceding abiotic damage.

2.2.2. Fungal Degradation

Fungi often cause more extensive deterioration than bacteria. Their hyphal systems penetrate deeply into coatings and substrates, while their enzyme systems such as cellulases, ligninases, oxidases, and proteases degrade a wide range of organic coating components [18]. Fungal growth increases when surface roughness rises due to UV exposure or abrasion, and when moisture promotes microbial activity. As a result, fungal attack frequently represents an advanced stage of biotic degradation that requires full coating replacement.

2.2.3. Algal and Lichen Colonization

Algae and lichens contribute to early stage biotic degradation by forming moisture retaining biofilms that trap pollutants and soften substrate surfaces. Although their direct damage is often less aggressive than fungal attack, they increase the likelihood of bacterial and fungal colonization [16]. Their production of organic acids enhances mineral dissolution and increases surface porosity. This sequence, which begins with algal colonization and progresses to bacterial activity and fungal invasion, reflects the typical biological succession seen in long-term microbiologically influenced corrosion.

2.3. Extent and Severity of Degradation

The severity of surface degradation depends not only on individual mechanisms but also on how they interact over time. UV exposure initiates chemical instability. Temperature cycling spreads microcracks. Moisture accelerates ionic transport. Biological colonization exploits these weaknesses and intensifies long-term deterioration. Together, these processes reduce durability, increase maintenance requirements, and shorten the service life of infrastructure materials. Table 1 synthesizes these mechanisms and provides a reference for understanding how each stressor contributes to overall degradation severity.

2.4. Implications for Protective Coating Design and Relevance to Algae Based Coatings

The degradation pathways described above define the performance criteria that protective coatings must meet. An effective coating must resist UV-induced chain scission, limit water and ion penetration, accommodate thermal cycling, provide chemical resistance, and inhibit microbial colonization. Conventional petroleum-based coatings typically excel in only a narrow set of these requirements, which contributes to their premature failure in multi-stressor environments.

Algae-based coatings contain naturally integrated protective features such as UV absorbing pigments, moisture resistant polysaccharides, ion blocking extracellular polymeric substances, and intrinsic antimicrobial compounds. These characteristics align closely with the degradation mechanisms described in this section and provide a scientific justification for exploring algae-based coatings in Section 3. This connection creates a clear and coherent transition from understanding the problem to evaluating material innovations.

Table 1.

Summary of dominant surface degradation mechanisms in infrastructure and their impact on coating performance.

Table 1.

Summary of dominant surface degradation mechanisms in infrastructure and their impact on coating performance.

| Degradation Factor | Mechanism | Resulting Damage | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV radiation | Polymer chain scission, oxidation, photodegradation | Embrittlement, discoloration, reduced adhesion | [16,17] |

| Thermal cycling | Expansion–contraction mismatch; freeze–thaw | Cracking, delamination, interface failure | [18] |

| Moisture & humidity | Hydrolysis, leaching, ion transport | Blistering, corrosion, concrete dissolution | [16,19,20] |

| Chemical pollutants | Acid/alkali attack, chloride ingress | Corrosion, mineral dissolution, ASR expansion | [21] |

| Abrasion | Mechanical erosion and friction | Surface wear, loss of coating thickness | [17] |

| Aerobic bacteria | Organic acid secretion | Mineral dissolution, pitting | [16,22] |

| Anaerobic bacteria | Sulfate reduction producing H2S | Deep pitting, steel corrosion | [16,21] |

| Silicate bacteria | Active dissolution of silicate phases | Concrete surface weakening | [16,19] |

| Fungi | Enzyme-mediated degradation, hyphal penetration | Severe softening, discoloration, loss of adhesion | [17,18,23] |

| Algae & lichens | Biofilm formation, organic acid secretion | Increased porosity, roughness, moisture retention | [16,24] |

3. Fundamentals of Algae-Based Coatings

3.1. Chemistry and Functional Compounds

Algae provide a diverse set of bioactive molecules that offer clear advantages for protective coating applications. These compounds include pigments, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), polysaccharides, proteins, and other metabolites with distinct chemical and functional properties. Unlike petroleum-derived additives, algae-derived materials are biodegradable, non-toxic, and compatible with green chemistry principles. These characteristics support long-term environmental safety while maintaining performance under demanding conditions.

Pigments such as phycocyanin, chlorophyll derivatives, astaxanthin, and fucoxanthin function both as colorants and protective agents. Their molecular structures enable strong UV absorption and antioxidant activity, which help coatings resist photodegradation. Fucoxanthin, with its allenic and conjugated carbonyl groups, provides notable UV stability under continuous sunlight exposure [25,26]. Astaxanthin from Haematococcus lacustris (formerly Haematococcus pluvialis) (Chlorophyta) also contributes high photoprotective capacity, supporting the mechanical stability of coatings exposed to sunlight and oxidation [27,28]. Additional compounds such as mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) and polyphenols further reduce oxidative damage by absorbing high-energy UV radiation and neutralizing reactive oxygen species [28,29]. These natural stabilizers offer safer alternatives to synthetic UV absorbers.

EPS produced by many microalgae enhances water resistance, cohesion, and structural integrity. EPS contains polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, which together form cross-linked networks that strengthen coating durability [30,31]. β-glucans from Chlorella vulgaris (green microalga) support adhesion, while alginate from Sargassum muticum (Phaeophyceae) provides strong film-forming ability and tensile strength [32,33]. These natural matrices add flexibility and allow coatings to absorb mechanical stress.

Algal polysaccharides including alginate, carrageenan, and ulvan contribute additional functionality. Through ionic cross-linking with divalent cations such as calcium and magnesium, these polymers form stable gel networks that improve toughness without synthetic additives [34,35]. Their ability to bind substrates while retaining elasticity supports coating stability under fluctuating moisture and temperature conditions. Marine algae also produce natural antifouling compounds, such as thymol, eugenol, and guaiacol, which reduce microbial biofilm formation in marine environments [36].

Microalgal proteins, particularly those from Limnospira platensis (formerly Spirulina platensis) (Cyanobacteriophyta), add further strength and UV resistance. Phycocyanin enhances structural cohesion and improves photostability [37,38,39]. These materials are renewable and biodegradable, which reinforces the sustainability benefits of algae-based coatings.

Despite these advantages, the functional composition of algal biomass varies with species, cultivation conditions, and harvesting methods. Such variability can reduce consistency in coating performance. To address this, processes such as sulfation, enzymatic hydrolysis, and nanocomposite blending are used to enhance mechanical properties, adhesion, and long-term stability [40,41].

Advances in extraction technologies have made algae-derived materials more viable for large-scale applications. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and supercritical CO2 extraction provide high yields, with UAE recovering up to 85 percent of polysaccharides and 75 to 80 percent of proteins depending on species and processing conditions [42,43]. Ionic-liquid extraction systems also reduce the use of hazardous solvents during processing [44]. Together, these developments strengthen the feasibility of algae-based materials for durable and multifunctional protective coatings. A detailed summary of key algae-derived components and their functional roles is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

3.2. Coating Formulation and Application

Successful algae-based coatings depend on effective formulation strategies that combine bio-based binders, pigments, proteins, antioxidants, and structural polysaccharides. These components are selected to achieve durability, environmental resistance, and functional performance equal to or better than petroleum-derived systems. As outlined in Supplementary Table S1, compounds such as fucoidan, phycobiliproteins, and carrageenan have demonstrated strong performance under UV, oxidative, thermal, and saline conditions.

Polysaccharides including alginate, carrageenan, and β-1,3-glucan play a central role in forming film matrices. Their natural film-forming ability, adhesion, and mechanical flexibility contribute to stable coating structures. Alginate extracted from Sargassum muticum exhibits strong adhesion due to its mannuronic and guluronic acid residues, which are capable of forming stable cross-linked networks [45]. Carrageenan enhances the uniformity and adhesion of coating films on various substrates [46].

Mechanical strength in algae-based coatings can be further improved by incorporating protein-based cross-linkers. Proteins from Limnospira platensis and Chlorella vulgaris form covalent bonds with polysaccharide matrices, increasing tensile strength and temperature resistance. Such composites have demonstrated tensile strengths up to 19.1 MPa and glass-transition temperatures near 122 °C, values consistent with certain synthetic coating resins [47,48].

Natural antioxidants such as astaxanthin contribute to oxidative durability. Astaxanthin from Haematococcus lacustris may reach concentrations of up to 4% of dry biomass [49]. Its extraction efficiency can exceed 80 percent when processed using techniques such as high-pressure homogenization or ultrasound-assisted extraction [49]. Stress conditions during cultivation can also increase antioxidant production. For example, high light intensity and nutrient limitation promote elevated levels of superoxide dismutase and catalase, improving resistance to oxidative degradation [50]. Similar responses have been documented in Euglena gracilis (Euglenophyta), where carotenoid accumulation enhances UV protection [3,46].

Pigments such as fucoxanthin from Padina tetrastromatica (Phaeophyceae) offer strong UV protection and antifouling effects. Ultrasound-assisted extraction can achieve concentrations of approximately 750 micrograms per gram of biomass [26]. Chlorophyll derivatives also reduce color fading and improve photostability in long-term exposure tests [45].

Proper rheological control is essential for applying algae-based coatings through spraying, dipping, or brushing. Chlorella-based formulations tend to have higher viscosity than petroleum-based systems, which necessitates adjustments in spray equipment to ensure even dispersion and consistent film thickness [51].

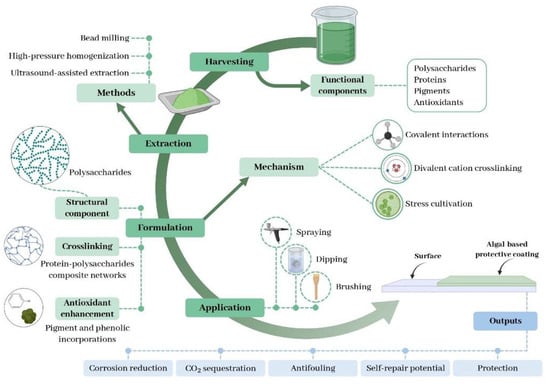

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the algae-based coating production process, illustrating the transition from biomass harvesting and extraction to formulation mechanisms (crosslinking and structural networking) and final application techniques.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the algae-based coating production process, illustrating the transition from biomass harvesting and extraction to formulation mechanisms (crosslinking and structural networking) and final application techniques.

Performance evaluations show promising results. Coatings containing alginate and carrageenan maintain structural integrity under thermal and saline stress, and they provide long-term corrosion resistance [46]. In outdoor weathering tests, coatings on calcareous substrates remained stable for up to two years with minimal porosity and color change [52]. Although biomass variability, cost management, and large-scale production remain challenges, ongoing improvements in formulation chemistry and extraction efficiency continue to advance the industrial potential of algae-based coatings.

3.3. Advantages over Conventional Coatings

The shift away from petroleum-based coatings is driven by concerns regarding VOC emissions, toxic additives, and dependency on non-renewable feedstocks. Algae-based coatings address these limitations by providing mechanical strength, multifunctional protection, and reduced environmental impacts.

Their mechanical performance results from the inherent functional groups of algal polymers. Hydroxyl, carboxylate, and sulfate groups promote strong interfacial bonding and adhesion [35,53]. Polysaccharides from Chlorella vulgaris achieve bonding strength comparable to epoxy resins. EPS from Chlorella vulgaris also contain glucuronic acid and rhamnose, which contribute to elasticity and impact resistance [54,55]. These naturally cross-linked networks dissipate mechanical stress without requiring synthetic fillers.

Algae-based coatings demonstrate strong resistance to environmental degradation. Under marine exposure, corrosion rates as low as 0.02 mm per year have been reported, representing a 40 percent reduction compared to polyurethane coatings [56]. Biomineralization processes further strengthen coatings by depositing calcium carbonate into microcracks, enhancing long-term durability. Alginate-based coatings also exhibit notable flame-retardant behavior, with limiting oxygen indices reaching approximately 48 percent, compared to about 20 percent for viscose fibers [57].

Algae offer significant environmental benefits. Microalgae can fix approximately 1.3 kg of CO2 per kg of biomass, with potential production yields up to 280 tons per hectare annually [58]. When used in hydrogel-based coatings, this biomass can continue contributing to carbon offset during use. Life cycle assessments suggest that such systems may achieve net-negative emissions, strengthening alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 13.

Natural photoprotective compounds such as MAAs and polyphenols further extend coating lifespan by absorbing UV radiation and reducing polymer degradation [28,29]. Compounds such as shinorine and porphyra-334 have high extinction coefficients across the UV A and UV B spectrum [35].

EPS also serve as hydrophobic barriers that limit water permeability, reduce moisture-driven degradation, and improve substrate adhesion [30,31]. Polysaccharides such as alginate and carrageenan form naturally cross-linked gel networks that enhance adhesion and mechanical resilience [34,35]. Their antimicrobial properties help reduce biofilm formation, which is critical for controlling microbially-induced corrosion [43].

Proteins from Limnospira platensis contribute UV absorption and antioxidant activity, reinforcing coating stability [37,38,39]. Marine algae also produce antifouling compounds such as thymol, eugenol, and guaiacol, which inhibit phototrophic biofilm development [36].

To address formulation variability caused by species differences and cultivation conditions, modification methods such as sulfation, enzymatic hydrolysis, and polymer blending remain important [40,41]. Improvements in green extraction technologies, such as ultrasound-assisted extraction and ionic-liquid systems, support high-yield and low-impact processing [42,43,44]. A direct comparison with conventional coatings is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of performance characteristics: Algae-Based vs. Traditional Petroleum-Based Coatings.

With continued optimization in formulation, processing, and rheological control, algae-based coatings show potential to become durable, high-performance, and carbon-negative alternatives to petroleum-derived products.

3.4. Comparison with Other Bio-Based Coating Systems

A range of bio-based coating systems has been developed to reduce reliance on petroleum-derived materials. These include lignin-, nanocellulose-, chitosan-, shellac-, vegetable-oil-, and bacterial-biopolymer-based coatings. Each demonstrates unique advantages in sustainability, performance, and biodegradability. However, when compared systematically, algae-based coatings offer a broader multifunctional profile due to their intrinsic UV protection, antioxidant activity, carbon fixation potential, and natural antifouling properties. This subsection compares algae-based coatings with other major bio-based systems to highlight their relative strengths and limitations.

3.4.1. Lignin-Based Coatings

Lignin is the second most abundant natural polymer after cellulose and represents a major renewable resource derived from pulping and agricultural waste. Its integration into coatings supports waste valorization and reduces dependence on fossil feedstocks [20]. Lignin also provides strong UV absorption, with lignin colloids enhancing UV-blocking efficiency more effectively than unmodified lignin. Lignin-chitosan films exhibit high UV absorbance and are promising for surface protection [20]. Barrier properties also improve significantly, particularly in water vapor and oxygen resistance when esterified kraft lignin is incorporated. Lignin nanoparticles enhance corrosion protection by limiting ion transport, and its use in polyurethane and epoxy coatings increases adhesion strength. Lignin-based materials are biodegradable, low-cost, and already used across industrial sectors including cement, petroleum, and forestry. However, variability in lignin chemistry moderate thermal instability in oxidized forms, and limited antimicrobial performance constrain its applicability in highly aggressive environments compared to algae-based systems.

3.4.2. Nanocellulose-Based Coatings

Nanocellulose composites provide strong barrier properties and support sustainable packaging applications. Cellulose nanocrystals combined with montmorillonite clay or soy protein reduce water absorption by 71 to 78 percent and significantly lower water vapor transmission [59]. Air permeance increases sharply with nanocellulose coatings, improving resistance to gas flow. The coatings rely on hydrogen bonding, which increases stiffness and adhesion to substrates. Nanocellulose, cellulose nanofibrils, and soy protein are fully biodegradable, and the formulations use relatively low-cost additives. However, the high viscosity of nanocellulose suspensions limits large-scale production, and moisture sensitivity remains a challenge. Unlike algae-derived compounds, nanocellulose does not intrinsically offer UV protection, antioxidant properties, or antimicrobial activity, requiring additional additives to match the multifunctionality of algae-based formulations.

3.4.3. Chitosan-Based Coatings

Chitosan films reinforced with nanocrystalline cellulose, clay, essential oils, or phenolic acids are widely used as biodegradable barrier coatings and edible films [60]. These coatings effectively control moisture transfer, reduce permeability to water vapor and gases, and support mechanical stability. Nanoclay additions can reduce water vapor permeability by up to 65%, while essential oils and cellulose nanocrystals further improve barrier performance. Mechanical properties, including stiffness and tensile strength, are often enhanced, though elongation decreases with some additives. Chitosan coatings are biodegradable and edible, making them suitable for food packaging. However, their stability is sensitive to temperature and storage conditions, and UV resistance is not inherently strong. Compared to algae-based coatings, chitosan lacks natural UV-absorbing pigments, photosynthetic compounds, or carbon sequestration potential.

3.4.4. Shellac-Based Natural Resin Coatings

Shellac is a natural resin widely used for wood coatings and varnishes. It is non-toxic, waterborne, and compatible with low-VOC formulations [61]. Shellac-based coatings exhibit excellent adhesion, especially when microcapsules with shellac cores are added, achieving the highest possible adhesion grade across tested concentrations. The coatings maintain hardness, show good thermal stability, and offer effective self-healing of microcracks when optimized at 10 percent microcapsule loading. Shellac films display favorable aging resistance but are not specifically designed for UV shielding or corrosion protection. Algae-based coatings provide broader environmental functionality, including UV absorption, antimicrobial properties, and ion-blocking capabilities, which typically exceed the performance of shellac-only systems.

3.4.5. Vegetable-Oil-Based Coatings and Polyols

Vegetable-oil-derived polyols, synthesized from castor oil and epoxidized soybean oil, are renewable, biodegradable, and low-cost, aligning with green manufacturing strategies [62]. Fatty acid amides in these systems improve adhesion due to strong interactions with metal surfaces. Vegetable oils have natural biodegradability and can be converted into coatings with good oxidative and thermal stability through chemical modifications. However, unmodified oils often display low oxidative stability, and their barrier and UV-resistance properties are limited. These systems provide sustainable alternatives to petroleum-based polyols but lack the intrinsic antioxidant pigments, EPS matrices, and natural antifouling compounds characteristic of algae-based coatings.

3.4.6. Bacterial Biopolymer-Based Coatings

Bacterial biopolymers such as PHB, PLA, xanthan, and bacterial cellulose are renewable, biodegradable, and capable of replacing synthetic polymers in multiple applications [63]. PHB, in particular, has mechanical properties similar to polypropylene and is fully biodegradable. Barrier properties can be enhanced with nanofillers, and microbial biopolymers support strong adhesion due to cell–surface interactions and cohesive EPS matrices. Large-scale fermenter production supports industrial scalability, though high production costs remain a challenge. While bacterial biopolymers contribute to reduced carbon emissions by replacing cement or plastics, they do not provide active carbon fixation like microalgae. Furthermore, they lack natural UV-protective pigments and bioactive antifouling compounds unless externally added.

Overall, many bio-based coating systems demonstrate strong sustainability potential and specific functional strengths. Lignin offers excellent UV-blocking performance, nanocellulose excels in barrier properties, chitosan provides edible and biodegradable matrices, shellac supports self-healing and adhesion, vegetable oils supply renewable polyols, and bacterial biopolymers deliver structural strength and biodegradability. However, algae-based coatings offer a uniquely integrated set of multifunctional traits. Their pigments supply inherent UV protection and antioxidant activity, EPS improves moisture resistance and adhesion, and natural metabolites inhibit biofilm formation. Most notably, microalgae are capable of direct carbon fixation during cultivation, which enhances the overall carbon-negative potential of algae-derived coatings. This combination of performance, sustainability, and biological functionality positions algae-based coatings as a strong alternative within the broader family of bio-based protective materials. Comparison with other bio-based coating systems is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison with Other Bio-Based Coating Systems.

4. Production & Scalability Challenges

4.1. Cultivation Systems

Efficient cultivation is the cornerstone of algae-based coating production, as biomass productivity directly influences compound availability, processing requirements, and technical scalability. Current industrial systems rely primarily on open ponds, photobioreactors (PBRs), and hybrid cultivation approaches, each presenting distinct advantages and technical limitations.

Open pond systems—remain the most widely used due to their low capital cost and minimal operational complexity. They rely on natural sunlight and atmospheric CO2, resulting in comparatively low energy consumption [64,65]. However, their productivity typically ranges between 10–25 g m−2 day−1, and susceptibility to contamination, invasive species, and seasonal fluctuations significantly limits consistency and year-round output [3,66]. High water evaporation rates and uncontrolled environmental exposure also reduce overall process stability. Despite these challenges, open ponds operate at 40–50% lower production cost than PBR systems [67], maintaining relevance for bulk, low-cost biomass.

Photobioreactors (PBRs)—provide a closed, controlled environment that enhances productivity and biomass quality. Typical yields range from 40–60 g m−2 day−1, two to three times higher than open ponds [68]. Their enclosed design improves contamination control and allows for the precise regulation of light, temperature, nutrient availability, and CO2 injection, resulting in more uniform biochemical profiles [27]. However, PBRs require significant capital investment, up to USD 500,000 per hectare, and high energy inputs, often 1.5–2.0 kWh per kg of dry biomass, limiting large-scale adoption for coating applications [15,69].

Hybrid cultivation systems—integrate both approaches by producing bulk biomass in open ponds, followed by controlled refinement or stress induction in PBRs. This two-stage model has demonstrated up to 35% higher production efficiency while reducing operational costs by approximately 40% compared with exclusive PBR use [58]. Although hybrid systems offer a balanced route to scalability, challenges remain related to contamination transfer, synchronization of operational conditions, and energy-efficient biomass transfer between stages.

Overall, while cultivation technologies have advanced significantly, achieving reliable, high-volume biomass production with consistent biochemical composition remains a central technical barrier for algae-based coating manufacturing.

4.2. Processing & Extraction Challenges

After cultivation and harvesting, scalable production depends on efficient biomass processing and extraction workflows capable of recovering pigments, polysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) with minimal degradation. Current extraction methods vary in efficiency and technical feasibility, with each approach presenting specific bottlenecks when transitioning from laboratory to industrial scale.

Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) offer rapid cell disruption and reduced solvent consumption, achieving high pigment yields. UAE has reported recoveries of 750 µg g−1 from Padina tetrastromatica, while MAE produced carotenoid yields of 629 µg g−1 from Limnospira platensis (formerly Arthrospira platensis) [26,70]. However, large-scale UAE and MAE require high-power reactors and efficient temperature control systems to prevent compound degradation, which complicates industrial implementation.

Supercritical CO2 extraction (SFE)—achieves high purity and >90% recovery of lipophilic pigments, particularly astaxanthin, when combined with mechanical pretreatment [49]. Yet SFE’s high-pressure equipment and energy demand remain major barriers, as the technical complexity exceeds that of typical coating-grade biopolymer extraction.

Growing interest in green solvents, such as ethanol–water mixtures and protic ionic liquids (PILs), aligns with circular economy principles while offering high extraction efficiency and reduced toxic waste generation [44]. Nevertheless, solvent recycling, process integration, and large-volume handling remain unresolved engineering challenges.

Hybrid and integrated biorefinery methods—combining mechanical, thermal, and solvent-based steps, enable sequential extraction of pigments, polysaccharides, and proteins from the same biomass batch, markedly improving overall resource efficiency [69]. Techniques such as pulsed electric field (PEF) extraction can achieve lipid recoveries near 96% of theoretical maxima [71]. Yet their scalability is hindered by equipment costs and operational complexity, and performance varies with biomass moisture content and intracellular composition [42,43].

A key challenge across all extraction methods is biomass variability, which arises from species differences, cultivation conditions, stress responses, and harvest timing. Variability affects viscosity, molecular weight distribution, pigment concentration, and polymer crosslinking potential, parameters essential for coating applications. Process standardization and real-time quality monitoring remain underdeveloped, limiting consistent industrial-scale production.

4.3. Scale-Up & Manufacturing Barriers

Transitioning algae-based coatings from laboratory to industrial production involves challenges beyond cultivation and extraction. Several bottlenecks arise during large-scale handling, formulation, and manufacturing that directly affect coating quality, stability, and functional performance.

One major barrier is biomass composition inconsistency, which impacts film formation, pigment dispersion, mechanical properties, and crosslinking behavior [72]. Batch-to-batch variability in polysaccharide content, pigment ratios, and protein fractions complicates formulation standardization. Controlled cultivation regimes and metabolic engineering strategies are needed to produce more predictable biochemical profiles [58].

Compound degradation during processing poses another obstacle. Pigments such as chlorophylls, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins are sensitive to heat, oxygen, and high-energy processing steps. For example, carotenoids undergo oxidative bleaching during prolonged exposure to air or light, reducing UV-blocking capacity [49]. Similarly, EPS and polysaccharides may depolymerize under high-shear mixing or elevated temperatures, altering viscosity and film integrity [73]. These degradation pathways require controlled-atmosphere handling, antioxidant buffering, or gentle processing workflows.

Energy-intensive steps, particularly drying and mechanical disruption, remain critical barriers. Freeze-drying produces high-quality biomass but imposes substantial energy penalties [26]. Centrifugation consumes 1.5–3.0 kWh per kg of dry biomass [67]. Technologies such as biofilm-based cultivation and non-mechanical dehydration offer potential reductions but require further optimization for coating-grade applications [29].

Integration challenges also arise in linking cultivation, extraction, and formulation. Inline stabilization of pigments and polymers is needed to maintain functional integrity, while oxygen exposure during transfer between processing steps accelerates degradation. Engineering continuous processing lines that prevent oxidation, maintain sterility, and minimize residence time remains a major technical challenge [74,75].

Finally, storage and shelf-life limitations impact scalability. Moisture-sensitive polysaccharides and photoactive pigments degrade during extended storage, even under refrigerated conditions, reducing coating performance over time [76]. Controlled humidity systems, encapsulation technologies, or dry stabilization techniques will be necessary for industrial readiness.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

The performance and scalability of algae-based coatings depend strongly on several operational and environmental parameters that influence biomass quality, pigment stability, polymer properties, and overall process efficiency. Variability in biochemical composition arises not only from cultivation and extraction methods but also from storage conditions and environmental exposure. These fluctuations introduce uncertainty into coating performance, industrial reliability, and cost modeling. The following subsections evaluate the primary sensitivities that constrain technical consistency at scale.

4.4.1. Cultivation Sensitivity

Algal biochemical composition responds rapidly to changes in light intensity, nutrient supply, culture density, and environmental stress. Variations in these factors influence pigment concentration, polysaccharide content, and polymer crosslinking potential [77]. In contrast, lignin benefits from highly stable supply chains tied to pulping processes, and nanocellulose exhibits predictable mechanical behavior when formulated with standard additives [59]. The heightened input-dependent variability in algae directly affects coating viscosity, film formation, mechanical stability, and UV-blocking performance. This sensitivity makes cultivation control a major determinant of product quality.

4.4.2. Processing Sensitivity

Extraction methods such as ultrasound, microwave treatment, and solvent extraction can degrade pigments and polysaccharides if the temperature, duration, and solvent composition are not tightly regulated [78,79]. This stands in contrast to lignin, which exhibits high photostability and a robust three-dimensional aromatic network [59,64], and cellulose systems where water absorption and WVTR shift predictably with clay or protein additives [64]. Because algal polymers and pigments are more susceptible to thermal and oxidative degradation, processing workflows require strict control to maintain coating-grade functionality.

4.4.3. Environmental Sensitivity: Moisture, Temperature, and Oxygen

Algae-derived biopolymers are inherently hydrophilic, making them highly responsive to moisture variations [80]. This behavior resembles the moisture sensitivity reported for nanocellulose coatings [64] and chitosan films, which require plasticizers or hydrophobic additives to achieve gas and moisture resistance [60]. Temperature fluctuations and oxygen exposure during processing and storage can trigger pigment oxidation and structural degradation, diminishing UV-protective capacity [81]. In contrast, lignin exhibits significant thermal stability and photostability [59], contributing to more predictable performance under environmental stress.

4.4.4. Cost and Scalability Sensitivity

Production costs for bacterial and plant-derived biopolymers vary with substrate selection and process scale, and similar challenges arise in algae-based systems. High cultivation costs, particularly in photobioreactor systems, and energy-intensive harvesting steps introduce substantial economic sensitivity [82]. Lignin benefits from a stable, low-cost supply chain derived from well-established pulp and paper industries [59], and plant oils remain inexpensive and abundant due to global agriculture. Algae-based systems therefore exhibit greater cost volatility, with unit-price fluctuations driven by biomass productivity, energy input, nutrient supply, and extraction efficiency.

Overall, algae-based coatings show higher sensitivity to cultivation conditions, processing parameters, environmental exposure, and cost fluctuations compared with lignin-, cellulose-, chitosan-, shellac-, plant-oil-, and bacterial biopolymer coatings. This elevated sensitivity underscores the importance of stabilizing biochemical profiles, standardizing extraction conditions, and developing robust processing frameworks. These technical sensitivities directly influence economic feasibility by altering productivity, energy requirements, solvent efficiency, and material yield. As discussed in Section 6.2, these same parameters also dominate the sensitivity of capital expenditure, operational expenditure, and minimum selling price in techno-economic models. Therefore, improvements in biological stability and process control at the technical level are essential not only for consistent coating performance but also for achieving economically competitive large-scale production.

4.5. Technical Feasibility Outlook

The technical feasibility of algae-based coatings depends on how effectively biological variability, extraction technologies, and industrial manufacturing requirements can be aligned to deliver consistent and scalable materials. Mature bio-based coating platforms such as lignin, nanocellulose, chitosan, shellac, plant oils, and bacterial biopolymers already benefit from long-established supply chains and predictable physicochemical properties. In comparison, algae-based systems are still emerging. Even so, microalgae provide several unique advantages that position them as promising next-generation coating feedstocks. Their inherent ability to fix CO2 offers a climate-positive production route that is not available in lignin-, cellulose-, or oil-derived coatings [59]. Natural pigment systems such as carotenoids and phycobiliproteins provide strong UV-blocking capabilities that are comparable to the aromatic chromophores in lignin [59]. In addition, extracellular polymeric substances and polysaccharides contribute film formation, adhesion, and self-healing behavior that are competitive with certain bacterial biopolymers [63]. The high biodegradability of algae-based materials also aligns well with circular-economy and low-impact material strategies.

Despite these advantages, several constraints currently limit industrial adoption. Biological variability is one of the most significant barriers. The biochemical composition of algae, including pigment ratios, polysaccharide profiles, and protein fractions, fluctuates with species, nutrient supply, cultivation lighting, and stress conditions. These fluctuations result in inconsistent viscosity, crosslinking behavior, and film performance [59]. This variability is more pronounced than in lignin, which exhibits high thermal and photostability due to its rigid aromatic structure [60,64], and in nanocellulose, which forms predictable barrier matrices when used with established reinforcement additives.

Moisture sensitivity is another challenge. Many algae-derived polysaccharides are hydrophilic and show swelling or mechanical softening in humid conditions. In many cases, this sensitivity is more pronounced than in chitosan or nanocellulose systems, which already require hydrophobic modification for enhanced stability [64]. Extraction pathways for pigments, polysaccharides, and EPS also remain technologically complex. Thermal, mechanical, and solvent-based extraction methods can degrade key bioactive compounds if conditions are not tightly controlled, which contrasts with the comparatively simple recovery routes used for shellac and modified plant oils [61,62].

Scalability is further influenced by limitations in cultivation and processing. High-productivity photobioreactor systems require substantial capital investment and high energy input, while open pond cultivation suffers from contamination, environmental fluctuations, and low biochemical uniformity [83]. Downstream processing steps such as cell disruption, drying, and pigment stabilization add additional energy demand and can accelerate oxidative degradation unless conducted under controlled atmospheres [84]. In comparison, lignin, bacterial biopolymers, and plant-oil derivatives benefit from mature and stable supply chains with predictable production costs and throughput.

Overall, algae-based coatings are technically feasible and show strong long-term potential. However, progress is required in three key areas to achieve industrial readiness. First, stabilization of critical biochemical components, especially pigments, EPS, and polysaccharides, is essential to match the durability and environmental resistance of lignin-based systems. Second, extraction and processing require intensification through integrated biorefinery strategies that improve resource efficiency and minimize degradation, similar to approaches used in lignin nanoparticle production and CNC-based composites. Third, scalable and cost-effective cultivation platforms are needed to reduce biomass variability and production cost so that algae-derived materials can compete directly with lignin, plant oils, and bacterial polymers. If these challenges are addressed, algae-based coatings have the potential to surpass existing bio-based coating technologies due to their carbon-negative production, multifunctionality, biodegradability, and capacity for self-healing and environmental remediation.

5. Multi-Functional Performance Analysis

5.1. Mechanical Properties

The mechanical performance of algae-based protective coatings determines their suitability as sustainable alternatives to synthetic systems such as polyurethane, epoxy, and siloxane coatings. These coatings derive their mechanical characteristics from biopolymer-rich compositions containing polysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). These components contribute to adhesion, impact resistance, hardness, flexibility, and wear resistance. However, despite notable environmental advantages, the mechanical durability of algae-based coatings requires further improvement to meet the demanding standards of industrial applications.

Adhesion strength is a primary determinant of coating performance, affecting resistance to delamination and mechanical stress. In algae-based coatings, adhesion is mediated by functional groups such as hydroxyl, carboxylate, and sulfate, which form hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, and covalent linkages with the substrate surface [53]. These mechanisms are comparable to those of epoxy coatings but eliminate the need for petroleum-based adhesion promoters. While polyurethane and epoxy coatings reach adhesion strengths of up to 7.2 MPa and 7.51 MPa, respectively, algae-based coatings currently exhibit values between 2.5 and 3.8 MPa [85,86]. The reduced polymer chain entanglement and lack of reactive cross-linkers limit substrate bonding. Emerging strategies such as plasma surface activation, enzyme-assisted cross-linking, and nanocellulose reinforcement have demonstrated potential to increase surface reactivity and enhance interfacial adhesion.

Impact resistance in algae-based coatings is largely governed by their polysaccharide network, which dissipates mechanical energy through its flexible structure. Exopolysaccharides extracted from Chlorella vulgaris, rich in glucuronic acid and rhamnose, provide natural elasticity and energy absorption, improving coating toughness [54]. Unlike synthetic epoxies that rely on inorganic fillers such as silica or carbon nanotubes to enhance strength, algae-based systems achieve impact resistance through intrinsic polymeric resilience [55]. Current impact resistance values range from 18 to 22 J/cm2, compared with 50 J/cm2 for epoxy coatings [86]. Incorporating graphene oxide, biopolymer-reinforced composites, or layered nanostructures could improve impact tolerance, especially in applications demanding high mechanical endurance.

Hardness and abrasion resistance are key to long-term performance in marine coatings, flooring, and industrial surfaces. Algae-derived polyurethane formulations exhibit pencil hardness values up to 5H, comparable to standard polyurethane systems, though below reinforced epoxies, which achieve Shore D hardness around 80.2 ± 3.06 [56,86]. The modulus of elasticity of algae-based coatings, between 0.07 and 0.26 GPa, aligns with modified polyurethane systems (0.26 GPa) but remains below that of high-strength polythiourethane/ZnO composites (0.952 GPa) [85]. To enhance surface hardness and wear resistance, researchers are exploring silica nanoparticle reinforcement, chitosan-polymer cross-linking, and bio-nanocomposite formulations that improve surface density and extend coating life.

Flexibility and crack resistance are also critical for coatings exposed to dynamic mechanical stress and thermal expansion. Algae-based coatings display high elasticity and retain structural integrity under 10 mm mandrel bend tests, showing no visible cracking [56]. The elastomeric characteristics of alginate and chitosan enable efficient strain absorption, reducing brittle failure. Polyurethane coatings typically show elongation at fracture between 14% and 65%, while epoxy coatings exhibit lower values due to their rigid cross-linked networks [85,86]. The elasticity of algae-based formulations positions them as suitable candidates for bridge coatings, expansion joints, and thermal barrier applications where flexibility is essential.

Despite encouraging progress, algae-based coatings must overcome certain limitations before they can fully substitute synthetic systems. Adhesion strength remains below industrial benchmarks, while wear resistance is insufficient for high-friction or load-bearing environments. Potential improvements include the integration of amphiphilic polymers, nanocomposite reinforcements, and bio-inspired self-healing materials that enhance both mechanical strength and sustainability. Long-term testing under industrial conditions, including accelerated weathering, chemical exposure, and field trials, is needed to validate real-world durability.

Future research should prioritize hybrid formulations that blend algae-derived polymers with bio-based elastomers, improving mechanical performance while maintaining biodegradability. The incorporation of self-repairing biopolymers, UV-stabilized bioadditives, and nanocellulose-enhanced matrices could further improve resilience and service life. Advancements in scalable production technologies will be essential to ensure cost-effective manufacturing. Through these developments, algae-based coatings could achieve the dual goals of high mechanical performance and environmental sustainability.

5.2. Protective Properties

Algae-based protective coatings provide multiple functional benefits, including corrosion resistance, antimicrobial protection, UV stability, and fire retardancy. These coatings present sustainable alternatives to conventional petroleum-based systems such as polyurethane and epoxy, addressing both environmental and performance challenges. Their protective behavior is derived from a combination of polysaccharides, EPS, and bioactive compounds, which impart long-term stability, self-repairing capacity, and resistance to environmental degradation [56].

Corrosion resistance is among the most notable advantages of algae-derived coatings, especially in marine and humid environments. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) studies show barrier resistance values between 109 and 1010 Ω·cm2, outperforming typical epoxy coatings that range from 107 to 108 Ω·cm2 [87]. Field trials report corrosion rates as low as 0.02 mm/year, representing a 40% improvement compared with polyurethane-based coatings in chloride-rich conditions [56]. This performance is attributed to biomineralization, where in situ calcium carbonate forms protective layers that seal microcracks and slow corrosion. These self-repairing features distinguish algae-based coatings from synthetic ones, which often degrade irreversibly over time [88].

Antimicrobial activity adds further value by preventing biofilm formation and microbial-induced corrosion (MIC), critical in marine and industrial environments. Unlike conventional coatings containing toxic biocides, algae-based systems employ natural bioactive molecules and nanoparticle additives for protection. Incorporating silver-hydroxyapatite (Ag-HAP) nanoparticles into algae-derived matrices achieved 86% inhibition of corrosion-related microbial colonies, substantially reducing substrate degradation [56]. In laboratory tests, these coatings reduced Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus populations by more than 90%, outperforming commercial antimicrobial coatings that lose efficiency over time [89,90,91]. The non-toxic antimicrobial nature of these systems supports their application in water treatment, pipelines, and submerged structures.

The UV and weathering resistance of algae-based coatings further enhances their outdoor performance. Natural photoprotective molecules such as carotenoids and mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) absorb high-energy radiation, minimizing polymer degradation. Accelerated UV exposure tests show that algae-based coatings retain approximately 85% of their mechanical integrity after 2000 h, compared with 65–70% retention for polyurethane and epoxy coatings [92,93]. Dense polysaccharide cross-linking contributes to UV shielding by limiting chain scission and pigment photodegradation, improving long-term stability.

Algae-based coatings also demonstrate strong thermal cycling resistance, maintaining structural integrity between −40 °C and +80 °C [66]. Their elastomeric flexibility prevents microcracking and delamination under repeated temperature changes [65]. This property provides a distinct advantage for outdoor infrastructure, aerospace structures, and equipment exposed to fluctuating thermal conditions.

Fire-retardant performance represents another key benefit. Alginate-based coatings form stable char layers during combustion, reducing heat release and improving flame resistance [57]. The limiting oxygen index (LOI) of alginate coatings is reported at 48%, significantly higher than polyurethane and viscose fibers, which average around 20% [57]. Bentonite addition further strengthens flame resistance by increasing char yield and thermal stability.

Despite these advantages, large-scale adoption faces challenges. Long-term field validation over multiple years is required to confirm performance consistency under variable climates [66]. Biomass variability also impacts reproducibility, emphasizing the need for raw material standardization. Economically, algae-based formulations currently cost more than synthetic coatings due to high extraction and processing expenses [27]. Hybrid strategies combining algae-derived polymers with selective synthetic additives can optimize performance while preserving sustainability [44]. Future research should focus on developing application-specific formulations, for example, corrosion-resistant marine coatings or UV-protective architectural layers to meet both technical and regulatory requirements [69].

5.3. Environmental Impact

Algae-based protective coatings represent a new generation of sustainable materials that merge environmental remediation with conventional protective functions. Unlike synthetic coatings that primarily act as passive barriers and contribute to pollution through volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions and microplastic generation, algae-based coatings offer active environmental benefits. These include carbon sequestration, air purification, and water treatment capabilities. Such functionalities arise from the photosynthetic activity of embedded microalgae, their bioactive metabolites, and adsorption mechanisms that continue to operate during use. In this way, algae-based coatings contribute not only to surface protection but also to continuous environmental improvement. However, large-scale implementation requires overcoming challenges in long-term biological stability, material standardization, and economic scalability. Many of the algae-derived compounds summarized in Supplementary Table S1 are produced through low-impact cultivation systems such as open ponds, photobioreactors, and integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA), reinforcing their environmental sustainability.

One of the most significant advantages of algae-based coatings is their ability to sequester carbon, aligning directly with global decarbonization efforts. Microalgae can fix approximately 1.3 kg of CO2 per kg of dry biomass, with optimized cultivation systems producing up to 280 tons of biomass per hectare annually [58]. In contrast to conventional coatings with high embodied carbon footprints, algae-based coatings incorporate microalgal biomass within polymer or hydrogel matrices, enabling continued CO2 fixation throughout their service life. Experimental data indicate that these coatings can reduce net CO2 levels by 51–73% over their functional lifespan [94]. Additionally, the integration of pyrolytic conversion processes allows for the transformation of algal residues into biochar, ensuring permanent carbon sequestration without the need for energy-intensive storage infrastructure. Life cycle assessments (LCAs) show that while epoxy coatings emit around 2.5 tons of CO2 per ton of product, algae-derived coatings exhibit net-negative carbon emissions [95]. This carbon-negative potential strengthens their relevance in carbon-regulated markets and green certification systems such as LEED.

Beyond carbon mitigation, algae-based coatings actively contribute to air purification by degrading airborne pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and VOCs. Conventional epoxy and polyurethane coatings are major VOC emitters, collectively releasing about 28.84 Tg per year, which contributes to ground-level ozone and smog formation [96]. In contrast, algae-derived coatings use photocatalytic and bioadsorptive mechanisms to remove VOCs from surrounding air. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) coatings derived from Limnospira/Arthrospira (formerly Spirulina) sp. (Cyanobacteriophyta) have demonstrated VOC degradation efficiencies above 60% within 24 h [96]. Moreover, C-phycocyanin extracted from Limnospira/Arthrospira (formerly Spirulina) exhibits dual antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, reducing microbial proliferation while enhancing indoor and outdoor air quality. This multifunctionality transforms algae-based coatings into “living” protective systems capable of improving environmental health in polluted urban settings.

Algae-based coatings also play a role in water purification and environmental remediation. Their bioactive and adsorptive properties enable the removal of heavy metals and pollutants from stormwater and industrial effluents. Unlike synthetic coatings, which may release microplastics or toxic leachates, algae-integrated coatings act as biological filters. Field-scale applications have reported removal efficiencies of 75–85% for metals such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) [58]. These coatings also support biofilm regeneration, which enhances long-term adsorption performance and reduces maintenance requirements compared with conventional membrane filtration systems. This self-renewing capability contributes to lower operational costs and sustainable water treatment, particularly in urban runoff management and wastewater reuse applications.

Despite their clear environmental benefits, several challenges limit the widespread adoption of algae-based coatings. A key issue is maintaining long-term photosynthetic viability within coating matrices. Exposure to UV radiation, temperature variations, and biofouling can reduce CO2 fixation efficiency after three to five years of use. Additionally, while life cycle assessments have demonstrated environmental superiority, comprehensive cradle-to-grave evaluations are still needed to assess the overall impact of cultivation energy demands, extraction emissions, and end-of-life biodegradability. Biological variability across algal species and cultivation conditions also complicates material standardization. Seasonal fluctuations and strain-specific biochemical profiles influence biopolymer and pigment yields, affecting consistency in coating performance [66]. Establishing uniform cultivation protocols and advanced quality control measures will be essential to achieve reliable large-scale production.

To enhance durability and scalability, future research should focus on encapsulation techniques that preserve algal photosynthetic activity within coatings while minimizing degradation under environmental stress. Hybrid formulations that combine algae-derived biopolymers with limited synthetic reinforcements can balance mechanical durability with eco-functionality. Furthermore, establishing standardized evaluation protocols for carbon sequestration, VOC degradation, and water purification performance will support regulatory approval and commercial certification. Such frameworks will be vital for integrating algae-based coatings into green infrastructure and sustainable construction standards.

Algae-based coatings redefine the traditional concept of protective surfaces. They shift from passive protection toward active environmental enhancement by simultaneously sequestering carbon, purifying air, and filtering water. This multifunctionality represents a major step forward in sustainable materials engineering. As global sustainability policies and carbon regulations tighten, algae-based coatings stand out as viable next-generation materials capable of reducing emissions, mitigating pollution, and supporting circular economy principles within construction and industrial sectors.

6. Economic Viability & Industrial Adoption

6.1. Cost Analysis vs. Petroleum-Based Coatings

The economic feasibility of algae-based protective coatings remains a major factor determining their industrial potential. Although these coatings provide clear environmental advantages and promising material performance, production costs remain high compared to conventional petroleum-based alternatives. Key cost drivers include biomass cultivation, extraction efficiency, and large-scale processing logistics. Despite recent technological progress, current cost analyses indicate that algae-based coatings still face economic challenges that restrict their commercialization. A detailed evaluation of cost components, covering biomass production, extraction, formulation, quality assurance, and regulatory compliance, helps identify strategies to enhance their economic competitiveness.

Biomass cultivation is the primary cost contributor. Open pond and photobioreactor (PBR) systems offer different cost–performance trade-offs. Open ponds require 40–60% less capital investment than PBRs but have lower productivity (20–25 g/m2/day) and higher risks of contamination and seasonal yield fluctuations [65]. PBRs provide controlled conditions and higher productivity up to 60 g/m2/day but involve high setup costs, often exceeding USD 500,000 per hectare [97]. Hybrid systems that use open ponds for bulk cultivation followed by refinement in PBRs have improved production efficiency by 35% and reduced costs by about 40% [58]. Even so, improving energy efficiency and optimizing process integration remain essential for achieving economic sustainability at larger scales.

Extraction and processing add significant costs, largely due to energy-intensive methods. Conventional solvent-based extraction and drying consume large amounts of energy and may degrade bioactive compounds that are critical to coating functionality [65]. Advanced technologies such as supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) improve recovery efficiency. SFE achieves over 90% recovery for astaxanthin, while MAE enhances polysaccharide yields by about 33% compared with traditional extraction [70,98]. However, both techniques require high capital investment. Alternative methods, such as bio-flocculation and electrocoagulation harvesting, have demonstrated potential to reduce energy costs while maintaining high recovery efficiency [99].

Quality assurance also contributes to overall costs. Unlike petroleum-based coatings that rely on standardized petrochemical feedstocks, algae-based formulations require strict quality control due to natural biomass variability. Differences in strain, nutrient supply, and growth conditions affect coating consistency, necessitating advanced monitoring systems. Analytical methods such as Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and UV–Vis spectroscopy help verify chemical structure and functional group uniformity, particularly in polysaccharide-based polyurethane coatings [100]. Although these quality controls add expense, they ensure product reliability and performance stability. Moreover, algae-derived polymers can be customized for improved adhesion, hydrophobicity, and corrosion resistance, providing long-term savings by extending service life and reducing reapplication frequency [56,100].

Material optimization strongly influences final costs. Additives such as silica–titania nanoparticles improve scratch resistance, while calcium–alginate cross-linked networks enhance adhesion [55,101]. Although these additives increase initial costs, they significantly extend coating durability, improving long-term cost efficiency. Continued innovation in biopolymer stabilization and bio-nanocomposite integration may further enhance performance while reducing energy consumption during production.

The biorefinery approach offers an effective pathway to improve economic feasibility. By sequentially extracting multiple high-value compounds such as biopolymers, pigments, and proteins from a single biomass batch, waste is minimized and overall revenue increases [102]. Additionally, integrating algae cultivation with wastewater treatment reduces nutrient costs and generates secondary income through pollutant remediation services. The use of renewable energy, such as solar-powered PBRs, has achieved operational cost reductions of 25–30%, further improving economic potential [103].

Despite the cost gap, algae-based coatings offer long-term economic advantages due to sustainability incentives and regulatory trends. Carbon pricing and VOC restrictions are driving industries toward bio-based products. With microalgae capable of fixing about 1.3 kg of CO2 per kg of biomass, algae-based coatings can benefit from carbon credit schemes valued at $50–70 per ton of CO2 sequestered [58]. In addition, demand for low-VOC coatings in LEED-certified and green infrastructure projects is increasing, enhancing market appeal [94].

Life cycle assessments (LCAs) highlight further economic potential. While petroleum-based coatings offer lower upfront costs, algae-derived formulations provide superior durability and longer service life, lowering overall maintenance and reapplication expenses. Studies show that alginate- and carrageenan-based coatings demonstrate enhanced corrosion and weathering resistance, outperforming conventional products [46,52]. Combined with tightening environmental regulations, this long-term resilience strengthens their market competitiveness.

To achieve cost parity, ongoing improvements are needed in cultivation productivity, extraction efficiency, and material performance. Scaling up biomass production, adopting renewable energy, and refining stabilization methods will reduce costs further. Strategic investment in biorefinery technologies, government incentives, and public–private partnerships will accelerate the transition of algae-based coatings from niche innovations to commercially viable products. With continued technological progress, algae-based coatings are positioned to become cost-effective, high-performance, and sustainable alternatives in the protective coatings industry.

6.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Economic Drivers for Industrial-Scale Adoption

A structured sensitivity analysis is essential for evaluating how biological, operational, and financial variables influence the economic feasibility of algae-based coatings. As discussed in Section 4.4, algae-based systems exhibit higher sensitivity to cultivation conditions, processing methods, and environmental exposure than lignin-, cellulose-, chitosan-, shellac-, plant-oil-, or bacterial biopolymer coatings. These technical sensitivities translate directly into economic variability. Table 4 provides a consolidated overview of the major economic drivers, reported ranges, and their influence on cost behavior across cultivation and downstream extraction systems.

Biomass productivity is consistently identified as the most influential upstream parameter. Techno-economic assessments show that volumetric productivity below 0.2 to 0.3 g·L−1·day−1 sharply increases production cost, while values of about 0.6 to 0.75 g·L−1·day−1 substantially improve unit economics [104,105]. Thin-layer cascades achieve the upper range of 0.75 g·L−1·day−1, while raceway ponds average around 0.1 g·L−1·day−1, which increases OPEX due to higher nutrient and dewatering requirements [105]. Productivity is therefore the strongest lever for reducing cost and minimizing land, water, and nutrient demand.

Energy consumption is the second major cost determinant, especially for mixing, aeration, and illumination. Artificial-light photobioreactor systems allocate up to 31 percent of total cost to electricity [106], while greenhouse-assisted PBRs reduce this to below 10 percent. Large-scale PBR aeration can reach 248.64 kWh per day [104], and raceway ponds still require 10 to 20 W·m−3 for mixing [105]. Cost sensitivity increases significantly at electricity prices of 0.08 to 0.10 USD per kWh [107], highlighting the need for renewable energy integration and hydrodynamic optimization.

Solvent extraction efficiency is a major downstream driver of economic performance. Lipid recovery increases from about 2 percent in unruptured cells to more than 70 percent with pretreatment [108]. Studies indicate that hexane-based wet extraction platforms can effectively process algal biomass with 10–20% solids content, eliminating the need for energy-intensive drying while recovering over 80% of the net available energy [109,110,111]. Higher extraction efficiency reduces biomass requirement, decreases drying and mixing energy, and improves overall cost efficiency. Because algae-based coatings depend heavily on pigments, polysaccharides, and EPS, this parameter strongly affects the OPEX and CAPEX-normalized cost.