Simple Summary

Prolonged drought in dry regions makes it hard for farmers to find enough feed for their cattle. This study tested whether spineless cactus could be used as an alternative feed during these shortages. Researchers mixed a local cactus (Miúda forage cactus) with Tifton hay and different amounts of urea to provide extra nitrogen. They compared these mixtures to traditional feeds like hay, wheat bran, and soybean meal. Most mixtures broke down well during digestion tests. While all urea levels performed similarly at first, the mix with the highest urea level showed poorer breakdown later on. The mixture with 2% urea digested the best overall. The results suggest that silage made from Miúda cactus, Tifton hay, and up to 2% urea can be a good, nutritious option for cattle in dry areas when regular feed is scarce.

Abstract

Prolonged drought and resource scarcity have limited feed availability for livestock in arid and semi-arid regions, necessitating strategic resource management to sustain cattle productivity. This study evaluated the use of spineless cactus as an alternative feed ingredient for ruminants in dryland areas. The experiment assessed in vitro cumulative gas production from silages of Miúda forage cactus (Nopalea cochenillifera Salm-Dyck) combined with Tifton 85 Bermuda Grass (Cynodon sp.) hay and varying levels of urea (1%, 2%, and 3% on a dry matter basis) as a nitrogen source. Traditional supplements comprising Tifton hay, wheat bran, soybean meal, and urea served as controls. Kinetic organic matter degradation parameters exceeded 60%. Dry matter degradability was similar across all urea levels at six hours but diverged over time, with the 3% urea treatment showing lower degradability at 48 and 96 h. Organic matter degradability varied throughout incubation, with the 2% urea treatment performing best. Overall, these findings suggest that silage made from native Miúda forage cactus combined with Tifton hay and up to 2% urea can serve as an effective alternative roughage to meet the nutritional requirements of ruminants, particularly during periods of feed scarcity in arid environments.

1. Introduction

In tropical pasture systems, providing ruminants with adequate nutrition and ensuring food security poses a major challenge. During drought periods, arid and semi-arid regions experience severe water scarcity, leading to dormancy of forage and a decline in native plant quality, which negatively impacts animal development and performance [1]. Under such conditions, it becomes necessary to supplement grazing with additional feed to mitigate negative energy balance. Incorporating high-digestibility forages is a common strategy to address nutritional deficits and provide essential dietary energy and metabolic precursors [2,3].

The use of native arid species, such as forage cactus, has been extensively studied as a low-cost and climate-resilient feed option for livestock, particularly during prolonged droughts and forage shortages [4]. Forage cactus are especially valued for their drought resistance, high energy and high-water content [5]. For instance, some studies have shown the high value of this plant in complete diets: Godoi et al. [6] found that combining spineless cactus with tropical forage could be utilized as a sole feed for sheep without compromising animal performance. Furthermore, Moreno et al. [7] demonstrated that goats consuming 250 g/kg of spineless cactus do not require additional water intake.

Despite its advantages, maximizing the use of forage cactus requires addressing its inherent nutritional constraints. The indiscriminate use of forage cactus as the primary ingredient in diets raises some nutritional concerns [8]. While it is rich in non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) and an excellent energy source, forage cactus is low in crude protein (CP) and fiber, which could limit its effectiveness and lead to nutrient imbalances, potentially causing metabolic disturbances [9]. Specifically, the elevated NSC content is rapidly broken down by rumen microbes, which produces large volumes of volatile fatty acids and organic acids. This reduces pH and increases the risk of rumen acidosis, thereby affecting animal health and performance. Maintaining a balance between NSC and fiber is essential to promote belching, saliva production, and maintain favorable rumen conditions [10].

Besides balancing energy and fiber, associating forage cactus with suitable nitrogen sources is necessary for supporting the protein metabolism of rumen microorganisms. This combination, providing energy from the cactus alongside nitrogen sources such as urea, can promote microbial growth and overall rumen fermentation [11]. Non-protein nitrogen (NPN) sources, particularly urea, are widely recognized as cost-effective supplements [12]. However, as with forage cactus, urea also has limitations due to its rapid hydrolysis into ammonia. This rapid breakdown can lead to an accumulation of ammonia in the rumen and blood, resulting in a lack of synchronization with the diet and potentially causing toxicity [13]. Consequently, cactus and urea represent important alternatives for ruminant diets, but their successful combined application requires the development of strategies to optimize the synchronization between the energy release from the cactus and nitrogen availability.

In their study, Souza et al. [14] highlighted the need for more scientific research on forage cactus, especially in dry regions, to better understand its physiological traits, including water use efficiency, digestibility, and optimal cultivation techniques for various genotypes. Choosing appropriate cactus species should consider their nutritional composition, adaptability, yield, and degradability [15]. While the general practice of combining forage cactus and urea is established for ruminants, there remains a critical gap in determining the optimal inclusion level of nitrogen required for efficient utilization and synchronization with high-energy cactus species.

Therefore, this study aims to estimate the fermentative potential and utilization of forage cactus by rumen microorganisms through in vitro assays that simulate a controlled ruminal environment, allowing for an assessment of feed degradability [16,17]. The objective is to evaluate and compare the degradability and cumulative gas production of silage coproducts made from Miúda forage cactus or Tifton grass hay, supplemented with varying levels of urea.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiments were conducted at the Food Analysis Laboratory of the Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology of Sertão Pernambucano, located in Floresta, Pernambuco, Brazil. The silages consisted of either the Miúda genotype of forage cactus (Nopalea cochenillifera Salm-Dyck) or Tifton hay, combined with four levels of a urea–ammonium sulfate solution based on dry matter content: 0% urea, 1% urea, 2% urea, and 3% urea. A traditional supplement containing Tifton hay, wheat bran, soybean, and urea was used as the control. The proportions of ingredients and the chemical composition of each silage are detailed in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Proportion of ingredients in experimental silages (g/kg DM).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of each silage treatment, g/kg of DM.

Dry matter (DM) was measured using method 920.39, organic matter (OM) and mineral matter (MM) by method 942.05, ether extract (EE) again by method 920.39, and crude protein (CP) using method 954.01 [18]. The analysis of neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) was performed following the procedures described by Detmann et al. [19] adapted from Van Soest [20,21]. NDF was determined with heat-stable α-amylase and corrected for residual ash.

Total carbohydrates (TC) and non-fiber carbohydrates (NFC) were estimated based on the principle that the sum of carbohydrates, fibers, minerals, ether extract, and crude protein constitutes the complete centesimal composition of the feed [19]. Total carbohydrates were calculated by the equation TC (%) = 100 − [CP + EE + MM], as suggested by Sniffen et al. [22], and NFC using the formula proposed by Weiss et al. [23]: NFC (%) = 100 − [NDF + CP + EE + MM].

Silages were packed into 4 L PVC microsilos and ensiled for 60 days. Ruminal fermentation kinetics were then assessed using a semi-automatic in vitro gas production technique [17]. One gram of each sample was incubated in 160 mL glass flasks, which were pre-flushed with CO2 and kept at 4 °C to prevent undesired fermentation prior to inoculation. Five hours before starting the experiment, the flasks were transferred to an oven at 39 °C and maintained at that temperature until inoculation.

The rumen inoculum was obtained from five non-descript crossbred cattle, following slaughter and evisceration at a local slaughterhouse in Floresta (Pernambuco, Brazil). These animals were part of the routine slaughter process and, with the owners’ consent, had been fed Miúda forage cactus, sugarcane bagasse, Tifton hay, and urea for 15 days prior to slaughter. The procedure falls within standard animal husbandry practices and does not present any ethical concerns. Therefore, ethical approval was not required and was waived by the Animal Use Ethics Committee of the Federal Institute of Pernambuco, Brazil (CEUA-IFPE). In the laboratory, rumen fluid was filtered through cotton gauze under continuous CO2 flow and maintained in a water bath at 39 °C. Each experimental flask was prepared containing 90 mL of culture medium, 10 mL of rumen fluid inoculum, and 1 g of test substrate (dry matter basis). The culture medium was formulated by mixing 500 mL of distilled water, 200 mL of buffer solution, 200 mL of macromineral solution, 60 mL of reducing agent solution, 0.1 mL of micromineral solution, and 1 mL of resazurin solution. Control flasks containing rumen fluid (10 mL) and culture medium (90 mL) were prepared following the methodology of Theodorou et al. [24].

For monitoring fermentation, flasks were removed from incubation at intervals of 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 h. Each treatment was replicated three times per time point. Measurements were taken for each treatment every 2 h, up to the designated endpoints of 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 96 h (Table 3).

Table 3.

Experimental layout and design for the kinetic in vitro fermentation study.

To determine DM content, fermentation residues were filtered using crucibles with porosity 1 (Pirex-Vidrotec) and dried in an oven at 100 °C for 48 h. Gas pressure from each sample was recorded using a pressure transducer (Press DATA 800, LANA, CENA-USP, Piracicaba, Brazil) connected to a 0.6 mm needle. The obtained pressure (P) (pounds per square inch) was converted into the volume of gases (mL) through the quadratic equation, V (mL) = 0.17454 P2 + 0.00315, as suggested by Pereira et al. [25]. Correlations were estimated between in vitro and in vivo results [26].

The cumulative gas production data were analyzed using a bicompartmental logistic model proposed by Schofield et al. [27], in which the equation used for fitting the cumulative gas production over time (V(t)) is the sum of two logistic functions:

V(t) = total maximal volume of gases produced

Vf1 = maximal volume of gas for the rapidly digested fraction (NFC)

Vf2 = maximal volume of gas for the slowly digested fraction (FC)

m1 = specific growth rate for the rapidly degraded fraction (NFC)

m2 = specific growth rate for the slowly degraded fraction (FC)

L = duration of the initial events of digestion (colonization time)

T = fermenting time

Statistical analyses were performed using the NLIN procedure in SAS 9.1 (2003) [26] (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The cumulative gas production data were also analyzed using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS (2003) version 9.1 [26], with a significance level of 0.05 for type I error. The standard non-linear fitting procedures NLIN were evaluated using criteria such as the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) to verify the model’s suitability and the reliability of the estimated kinetic parameters.

Means were compared using Dunnett’s test and orthogonal contrasts. The contrasts applied were:

I—Linear effect of urea level;

II—Quadratic effect of urea level;

III—Cubic effect of urea level.

After analysis, the lag time was determined to be 2 h, and the decay rate constants for each treatment are reported in Table S1 of the Supplementary Material.

3. Results

The cumulative gas production and the final volume of gas produced from Miúda cactus silage decreased with the inclusion of urea (Table 4). Among the treatments, the one containing 3% urea and 16% spineless forage cactus showed the lowest gas yield. However, no significant differences were observed between the treatments with 1% and 2% urea inclusion.

Table 4.

Cumulative gas production volume (mL/g DM) of Miúda cactus silage associated with Tifton hay and different urea levels.

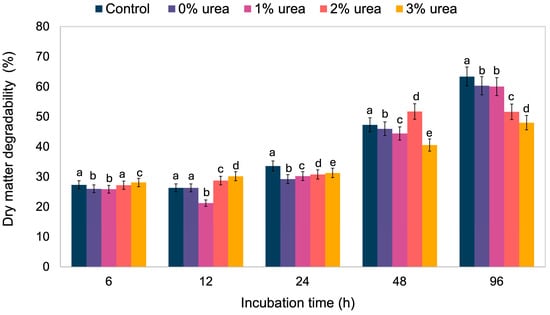

The results for the degradability of Miúda silage (Table S2), influenced by different levels of urea inclusion and incubation times, are presented in Figure 1. In general, degradability tends to increase over time. Although all treatments exhibited similar degradability at 6 h, the values began to diverge with longer incubation periods. Notably, the treatment with 3% urea showed a gradual decrease in degradability compared to the other treatments, and at 48 and 96 h, it had the lowest degradability.

Figure 1.

Dry matter degradability of silages at different incubation times. Means lacking a common letter within the same incubation time differ significantly (p < 0.05).

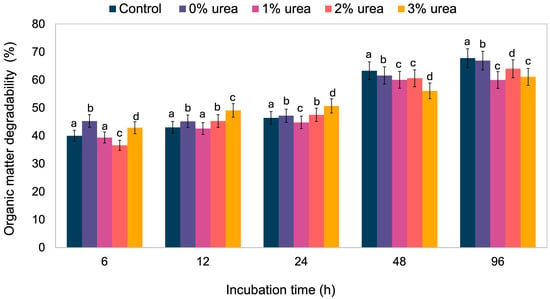

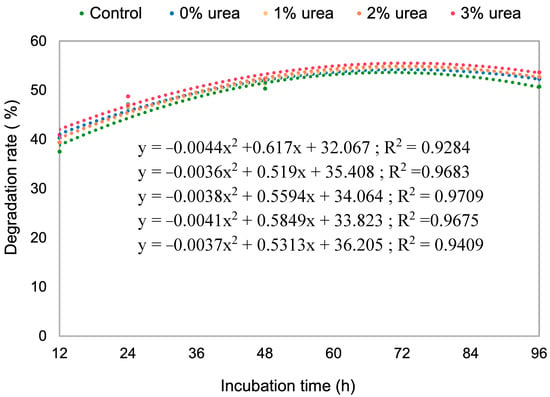

The results for OM degradability over time and under varying levels of urea are shown in Figure 2 and Table S3. By the final incubation period, the silage treated with 2% urea outperformed those with 1% and 3% urea. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 3, the degradability rate increased with incubation time for all urea levels until stabilizing at 72 h.

Figure 2.

Organic matter degradability of silages at different incubation times. Means lacking a common letter within the same incubation time differ significantly (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Dry matter degradability rate of silages with different levels of urea over 96 h of incubation.

4. Discussion

As delineated in the Results section, it was demonstrated that although the utilization of urea as a non-protein nitrogen source combined with spineless cactus silage can offer benefits for ruminant nutrition, exceeding certain thresholds can be problematic. In this study, altering the energy-to-protein ratio by replacing a fraction of the forage cactus (from 190 to 160 g/fg DM) with urea at levels exceeding 2% was associated with the potential to induce imbalances in the rumen environment, as it significantly affected cumulative gas production (Table 2).

The cumulative gas production trends observed suggest that treatments with 1% urea + 180 g/kg DM of cactus and 2% urea + 170 g/kg DM of cactus were the most effective for nutritional synchronization among the evaluated formulations. While these findings are not an absolute threshold for all dietary formulations, reducing forage cactus inclusion to accommodate higher urea levels proved counterproductive for gas production in this study. This suggests that the decline in readily fermentable carbohydrates (NFC) from the cactus limited the microbial capacity to efficiently utilize the nitrogen surplus, thereby compromising the overall fermentation kinetics.

The results are consistent with findings in the existing literature. Alipour et al. [28] investigate the effects of diets containing 0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, and 1.5% urea on the performance of beef cattle. The authors concluded that up to 1.5% urea could be included in animal feed without negatively affecting nutrient intake, digestibility, or overall cattle performance. They found that varying urea levels did not significantly influence (p > 0.05) dry matter intake and digestibility, Average Daily Gain, Feed Conversion Ratio, or Carcass Yield. It is important to note that, unlike in vitro fermentation kinetics, in vivo studies are significantly influenced by the host animal. The direct extrapolation of in vitro results to whole-animal outcomes is limited.

Replacing diets with more than 2% urea may lead to excess ammonia in the rumen, resulting in microbial imbalances primarily due to an improper nitrogen-to-carbon ratio and nitrogen losses through urine and milk [29]. The nitrogen balance in the rumen is closely tied to the carbohydrate and amino acid content of the diet, as nutrients with differing degradation rates can affect the distribution and equilibrium of bacterial species, thereby negatively impacting cumulative gas production [30]. Then, the reduced gas production observed at the 3% urea level is mainly caused by a harmful metabolic imbalance. This urea level causes rapid, excessive ammonia release that exceeds the microbial capacity for assimilation, leading to ammonia loss from the rumen instead of being converted into microbial protein, thus decreasing fermentation activity. This effect is intensified by the simultaneous decrease in Miúda forage cactus inclusion, which reduces the essential supply of readily fermentable NFC. The combination of NPN overload and decreased energy synchronization compromised microbial efficiency, leading to the lowest cumulative gas production.

Acedo et al. [31] investigated the effects of urea concentration on animal supplementation. They found that elevated urea levels can disrupt the balance between rumen-degradable protein and the ruminal degradation rate of fibrous materials. The authors indicated that urea concentrations exceeding 1.6% of DM may lead to reduced forage intake. Similarly, Benedeti et al. [32] reported that substituting soybean meal with slow-release urea caused a linear decline in the intake of DM, CP, and OM, depending on the substitution level.

From another perspective, Santos et al. [33] evaluated cumulative gas production from thirteen different cactus genotypes. They observed that feed with low structural carbohydrate content and high NFC levels significantly contributed to gas production. Furthermore, they reported that a high pectin concentration in forage cactus enhances fermentation, increasing gas volume and promoting dry matter degradation. This finding aligns with the present study, in which increased urea levels were associated with a reduced concentration of spineless cactus and NFC in the silage, ultimately resulting in lower gas production. The behavior is explained by the addition of urea, which replaced cactus on the DM basis. Also, as reported by Boukrouh et al. [34] there is a negative correlation between fiber and digestibility.

Castañeda-Trujano et al. [35] conducted an experiment evaluating the use of cactus pear cladodes in sheep fattening diets. The tested diets included one without silage, one with corn silage, and others containing either 10% or 20% cactus silage (composed of 64% nopal cladode, 11% prickly pear, 10% hibiscus grain, and 15% oat straw). This inclusion increased the levels of non-structural carbohydrates and degradable fiber, resulting in a greater fraction of available energy in the diet. Notably, this increase did not negatively affect fattening productivity, indicating that cactus pear can enhance digestive efficiency while reducing the environmental impact of the diet.

The increasing trend in DM degradability of Miúda silage over time and with higher urea levels can be explained by the fact that urea-based diets are rapidly hydrolyzed in the rumen. Therefore, it is essential that these diets be consumed alongside readily available energy sources to enable microorganisms to efficiently utilize the released nitrogen [36]. One of the main characteristics of cactus is its high content of readily digestible carbohydrates, which serve as an energy source for rumen microorganisms. Consequently, providing rapidly degradable nitrogen sources is crucial to optimizing energy use by the ruminal flora. This combination significantly influences microbial growth and activity, thereby enhancing ruminal degradability [37].

Lins et al. [38] and Santos et al. [39] investigated diets incorporating forage cactus and found that high ammonia levels and excessive urea in animal feed negatively affect palatability and ruminal fermentation. This effect is primarily due to the high availability of NPN and the low energy contribution from slowly digestible NFC, resulting in an imbalance in the energy-to-protein ratio required by ruminal microbes. Interestingly, although in this study he 3% urea treatment did not severely compromise dry matter degradability rates (Figure 3), the decline in gas volume suggests a metabolic shift. This divergence indicates that while substrate consuming remained constant, the microbial fermentation pathways may have been redirected toward alternative metabolites rather than gaseous end-products.

Wang et al. [40] conducted experiments to evaluate the effects of different urea supplementation levels in sheep diets containing soybean, corn, and wheat bran. They observed that urea concentrations above 2.5% adversely affected animal performance, leading to reduced DM digestibility and lower average daily weight gains. Consequently, the authors recommend that, to ensure animal safety and optimal performance, urea levels should be kept below 1.5%. This value is notably more conservative than the threshold reported in the current study, as we have demonstrated that urea levels up to 2% are beneficial when combined with forage cactus.

The degradability rate, which increases with incubation time and stabilizes after 72 h, is likely influenced by the substantial amount of fibrous material present during the initial colonization by ruminal microorganisms. All five degradation curves exhibited similar trends, with only minor differences observed beyond 96 h of incubation. This outcome underscores how varying urea levels can influence cumulative gas production. Due to its high availability in the rumen, urea can be an effective supplement for ruminants when paired with readily fermentable carbohydrate sources. However, it is important to report the potential adverse effects and limitations of urea. Boukrouh et al. [41] tested goat diets and, despite adding urea to equalize CP levels, found a lower protein content in the meat of goats fed bitter vetch. They explicitly attributed this outcome to the lower content of essential and limiting amino acids (e.g., methionine and cysteine) and the presence of antinutritional factors. This result highlights a possible key limitation of urea in animal performance: as a Non-Protein Nitrogen (NPN) source, it does not supply preformed essential amino acids. Therefore, although urea successfully helps achieve target CP levels the study underscores that the quality of the absorbed amino acid profile can have some impact on animal performance.

According to Paliwal et al. [42], feeds with a lower soluble fraction require longer colonization times. In contrast, Moreira et al. [43] found that feeds rich in pectin and rapidly digestible carbohydrates demonstrate higher degradation rates. Faria et al. [44] assessed the impact of adding propylene glycol or monensin to corn silage on carbohydrate degradation kinetics, identifying a 97% correlation between cumulative gas production and degradation rate.

Over the years, numerous researchers have reported that including urea in animal diets enhances nutrient intake, ruminal fermentation, and degradability. This improvement is largely attributed to the increased growth rate of rumen microorganisms, driven by the nitrogen made available as ammonia following urea hydrolysis [45].

5. Conclusions

The treatments analyzed in this study indicate that spineless cactus has significant potential for ruminal degradability and a positive effect on cumulative gas production. Silages formulated with Tifton hay, Miúda forage cactus, and urea (1%, 2% or 3%) demonstrated organic matter degradation kinetics exceeding 60%. However, cumulative gas production was significantly inhibited when cactus inclusion was reduced to 160 g/kg DM with 3% urea. This effect is likely linked to a ruminal metabolic imbalance caused by the reduction in readily fermentable carbohydrates and the simultaneous excess of ammonia release, which hinders energetic synchronization. In this sense, when combining the overall analysis of urea effects in silages, although there is no statistical difference in terms of degradability within the tested limits, adding more than 2% urea in the formulated diets could pose problems for rumen health, whereas including up to 2% urea, keeping 170 g/kg DM of cactus, represents a promising alternative to animal supplementation, as it does not affect cumulative gas production. Finally, further studies using iso-energetic diets are recommended to isolate the specific effects of urea toxicity from the influence of non-structural carbohydrate levels. This approach will allow for a more precise calibration of the optimal urea threshold.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ruminants6010004/s1, Table S1: Samples, replication and decay rate constants for each treatment; Table S2: Degradability rate values (mean and SEM) for dry matter at each time point; Table S3: Degradability rate values (mean and SEM) for organic matter at each time point.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.T., D.P.S. and D.S.R.; methodology, I.A.T., J.S. and C.T.F.C.; formal analysis, J.S. and C.T.F.C.; data curation, J.S. and C.T.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.T., M.J., F.M., J.S., J.M.S.C.G. and H.E.P.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Waived by CEUA-IFPE.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study leading to a patent application. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial assistance from Brazilian research funding agencies such as Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—CAPES, under Finance Code 001, a Brazilian foundation within the Ministry of Education (MEC), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq, a Brazilian foundation associated with the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI), and Foundation of Support to Research and Technological Innovation of the State of Sergipe—FAPITEC/SE. Our thanks are also extended to the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) for financial support to the Center for Research and Development in Agrifood Systems and Sustainability (CISAS) [UID/05937/2025 (doi.org/10.54499/UID/05937/2025)].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADF | Acid Detergent Fiber |

| CP | Crude Protein |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| EE | Ether extract |

| FC | Fiber Carbohydrates |

| MM | Mineral Matter |

| NDF | Neutral detergent Fiber |

| NPN | Non-Protein Nitrogen |

| NSC | Non-Structural Carbohydrates |

| NFC | Non-Fiber Carbohydrates |

| TC | Total Carbohydrates |

| OM | Organic Matter |

References

- Balehegn, M.; Ayantunde, A.; Amole, T.; Njarui, D.; Nkosi, B.D.; Müller, F.L.; Meeske, R.; Tjelele, T.J.; Malebana, I.M.; Madibela, O.R.; et al. Forage Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Review of Experiences, Challenges, and Opportunities. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.S.; Rodrigues, M.T.; De Oliveira, T.S. Effects of Forage Quality and Particle Size on Feed Intake and Ruminoreticulum Content of Goats. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 7, txad101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, L.F.; da Silva, T.E.; Franco, M.d.O.; Detmann, E. Can Associative Effects Affect In Vitro Digestibility Estimates Using Artificial Fermenters? Ruminants 2023, 3, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, I.A.; Costa, C.T.F.; Jesus, M.S.; Mata, F.; Santos, J.; Santana, H.E.P.; Silva, D.P.; Ruzene, D.S. Spineless Cactus (Opuntia stricta and Nopalea cochenillifera) with Added Sugar Cane (Saccharum officinarum) Bagasse Silage as Bovine Feed in the Brazilian Semi-Arid Region. Ruminants 2025, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipango, N.; Ravhuhali, K.E.; Sebola, N.A.; Hawu, O.; Mabelebele, M.; Mokoboki, H.K.; Moyo, B. Prickly Pear (Opuntia spp.) as an Invasive Species and a Potential Fodder Resource for Ruminant Animals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, P.F.A.; Magalhães, A.L.R.; de Araújo, G.G.L.; de Melo, A.A.S.; Silva, T.S.; Gois, G.C.; Dos Santos, K.C.; do Nascimento, D.B.; da Silva, P.B.; de Oliveira, J.S. Chemical Properties, Ruminal Fermentation, Gas Production and Digestibility of Silages Composed of Spineless Cactus and Tropical Forage Plants for Sheep Feeding. Animals 2024, 14, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, G.M.B.; de Araujo, G.G.L.; de Almeida, V.V.S.; Oliveira, A.C.; dos Santos Silva, M.J.M.; do Sacramento Ribeiro, J.; dos Santos Pina, D.; Neto, O.B.; da Silva, N.I.S.; de Lima Júnior, D.M. Goats Fed with 250 g/Kg of Cactus Do Not Need Drink Water. J. Arid Environ. 2024, 222, 105176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, G.d.C.; Santos, E.M.; Campos, F.S.; Cavalcanti, H.S.; Leite, G.M.; Coelho, D.F.O.; Santana, L.P.; Gomes, P.G.B.; Torres Júnior, P.d.C.; Santos, M.A.C.; et al. Optimizing Silage Quality in Drylands: Corn Stover and Forage Cactus Mixture on Nutritive Value, Microbial Activity, and Aerobic Stability. J. Arid Environ. 2024, 220, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.A.L.; Santos, D.C. Morphological and Nutritional Characterization of the Cladodes of Seven Varieties of Forage Cactus of the Genus opuntia Cultivated in Brazil. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 169, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, I.M.; El-Hais, A.M.; El-Hendawy, N.M.; El- Bltagy, E.A.; Allam, A.A.; Hassan, A.A.; Atia, S.E.S. Utilization of Cactus Cladodes as a Replacement for Berseem Clover: Effect on Nutrient Intake, Rumen Fermentation, Blood Metabolites, and Milk Yield, Composition and Fatty Acid Profile in the Diets of Dairy Goats. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 324, 116312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhtib, A.; Muna, M.; Darag, M.; Alkhalid, I.; Al-asa’ad, Z.; Mfeshi, H.; Zayod, R.; Burton, E. Spineless Cactus Cladode Is a Viable Replacement to Barley and Maize Grains in the Feed Rations of Dromedary Camel Calves. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 2368–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.S.d.M.; Cruz, G.F.d.L.; Vieira, D.d.S.; Santos, F.N.d.S.; Lemos, M.L.P.; Pinheiro, J.K.; Santos, E.M. Effects of Non-Protein Nitrogen on Buffel Grass Fiber and Ruminal Bacterial Composition in Sheep. Livest. Sci. 2023, 272, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Pereira Filho, J.M.; Oliveira, J.; Lucena, K.; Mazza, P.; Silva Filho, E.; Nascimento, A.; Pereira, E.; Vaz, A.; Barbosa, A.; et al. Effect of Slow-Release Urea on Intake, Ingestive Behavior, Digestibility, Nitrogen Metabolism, Microbial Protein Production, Blood and Ruminal Parameters of Sheep. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, J.T.A.; Ribeiro, J.E.d.S.; Ramos, J.P.d.F.; Sousa, W.H.d.; Araújo, J.S.; Lima, G.F.C.; Dias, J.A. Quantum Yield and Water Use Efficiency of Genotypes of Forage Spineless Cacti in the Brazilian Semiarid. Arch. De Zootec. 2019, 68, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Luna, R.E.; Herrera-Angulo, A.M.; Siqueira, M.C.B.; Conceição, M.G.d.; Chagas, J.C.C.; Monteiro, C.C.F.; Véras, A.S.C.; Carvalho, F.F.R.; Ferreira, M.A. Spineless Cactus plus Urea and Tifton-85 Hay: Maximizing the Digestible Organic Matter Intake, Ruminal Fermentation and Nitrogen Utilization of Wethers in Semi-Arid Regions. Animals 2022, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio, R.M.; Mould, F.L.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Owen, E.; Channa, K.S.; Theodorou, M.K. A Semi-Automated In Vitro Gas Production Technique for Ruminant Feedstuff Evaluation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol 1999, 79, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurício, R.M.; Pereira, L.G.R.; Gonçalves, L.C.; Rodriguez, N.M. Relationship between Volume and Pressure for Installation of the Semi-Automated in Vitro Gas Production Technique for Tropical Forage Evaluation. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2003, 55, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Detmann, E.; de Souza, M.; Filho, S.d.C.V.; Queiroz, A.d.; Berchielli, T.; Saliba, E.d.O.; Cabral, L.d.S.; Pina, D.d.S.; Ladeira, M.; Azevedo, J. Métodos Para Análise de Alimentos; Suprema: Visconde do Rio Branco, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J. Use of Detergents in the Analysis of Fibrous Feeds. 2. A Rapid Method for the Determination of Fiber and Lignin. J. Assoc. Off. Agric. Chem. 1963, 46, 829–835. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Wine, R.H. Use of Detergents in the Analysis of Fibrous Feeds. IV. Determination of Plant Cell-Wall Constituents. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 1967, 50, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sniffen, C.J.; O’Connor, J.D.; Van Soest, P.J.; Fox, D.G.; Russel, J.B. A Net Carbohydrate and Protein System for Evaluating Cattle Diets: IV. Predicting Amino Acid Adequacy. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 71, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, W.P.; Conrad, H.R.; St. Pierre, N.R. A Theoretically-Based Model for Predicting Total Digestible Nutrient Values of Forages and Concentrates. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1992, 39, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, M.K.; Williams, B.A.; Dhanoa, M.S.; McAllan, A.B.; France, J. A Simple Gas Production Method Using a Pressure Transducer to Determine the Fermentation Kinetics of Ruminant Feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1994, 48, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.S.; Pimentel, P.G.; Duarte, L.S.; Mizubuti, I.Y.; de Araújo, G.G.L.; Carneiro, M.S.d.S.; Lousada Regadas Filho, J.G.; Maia, I.S.G. Determinação Das Frações Proteicas e de Carboidratos e Estimativa Do Valor Energético de Forrageiras e Subprodutos Da Agroindústria Produzidos No Nordeste Brasileiro. Semin. Cienc. Agrar. 2010, 31, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS. SAS/STAT 9.1 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2003; ISBN 1590472438. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, P.; Pitt, R.E.; Pell, A.N. Kinetics of Fiber Digestion from In Vitro Gas Production. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 2980–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, D.; Saleem, A.M.; Sanderson, H.; Brand, T.; Santos, L.V.; Mahmoudi-Abyane, M.; Marami, M.R.; McAllister, T.A. Effect of Combinations of Feed-Grade Urea and Slow-Release Urea in a Finishing Beef Diet on Fermentation in an Artificial Rumen System. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 4, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.T.F.; Ferreira, M.A.; Campos, J.M.S.; Guim, A.; Silva, J.L.; Siqueira, M.C.B.; Barros, L.J.A.; Siqueira, T.D.Q. Intake, Total and Partial Digestibility of Nutrients, and Ruminal Kinetics in Crossbreed Steers Fed with Multiple Supplements Containing Spineless Cactus Enriched with Urea. Livest. Sci. 2016, 188, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kand, D.; Bagus Raharjo, I.; Castro-Montoya, J.; Dickhoefer, U. The Effects of Rumen Nitrogen Balance on in Vitro Rumen Fermentation and Microbial Protein Synthesis Vary with Dietary Carbohydrate and Nitrogen Sources. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 241, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, T.S.; Paulino, M.F.; Detmann, E.; de Campos Valadares Filho, S.; de Moraes, E.H.B.K.; de Figueiredo, D.M. Níveis de Uréia Em Suplementos Para Terminação de Bovinos Em Pastejo Durante a Época Seca. Acta Sci. 2007, 29, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Benedeti, P.D.B.; Paulino, P.V.R.; Marcondes, M.I.; Valadares Filho, S.C.; Martins, T.S.; Lisboa, E.F.; Silva, L.H.P.; Teixeira, C.R.V.; Duarte, M.S. Soybean Meal Replaced by Slow Release Urea in Finishing Diets for Beef Cattle. Livest. Sci. 2014, 165, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.D.; Neves, A.L.A.; Santos, D.C.; Pereira, L.G.R.; Gonçalves, L.C.; Ferreira, A.L.; Costa, C.T.F.; Araujo, G.G.L.; Scherer, C.B.; Sollenberger, L.E. Divergence in Nutrient Concentration, in Vitro Degradation and Gas Production Potential of Spineless Cactus Genotypes Selected for Insect Resistance. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 156, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukrouh, S.; Noutfia, A.; Moula, N.; Avril, C.; Louvieaux, J.; Hornick, J.L.; Chentouf, M.; Cabaraux, J.F. Ecological, Morpho-Agronomical, and Nutritional Characteristics of Sulla flexuosa (L.) Medik. Ecotypes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Trujano, F.J.; Miranda-Romero, L.A.; Tirado-González, D.N.; Tirado-Estrada, G.; Achiquen-Millán, J.; Améndola-Massiotti, R.D.; Martínez-Hernández, P.A. Gas Production and Environmental Impact Indicators from in Vitro Fermentation of Diets with Nopal Silage (Opuntia ficus-indica L.). Agro Product. 2023, 16, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.G.; Costa, R.G.; Medeiros, A.N.D.; De, R. Use of Different Urea Levels in the Feeding of Alpine Goats. Rev. Bras. De Zootec. 2012, 41, 1713–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shahzad, K.; Shen, S.; Dai, R.; Lu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Qi, R.; Gao, P.; et al. Altering Dietary Soluble Protein Levels With Decreasing Crude Protein May Be a Potential Strategy to Improve Nitrogen Efficiency in Hu Sheep Based on Rumen Microbiome and Metabolomics. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 815358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, S.E.B.; Pessoa, R.A.S.; Ferreira, M.d.A.; Campos, J.M.d.S.; da Silva, J.A.B.A.; de Silva, J.L.; Santos, S.A.; Melo, T.T.d.B. Spineless Cactus as a Replacement for Wheat Bran in Sugar Cane-Based Diets for Sheep: Intake, Digestibility, and Ruminal Parameters. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2016, 45, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.C.; Magalhães, A.L.R.; Silva, D.K.A.; Araújo, G.G.L.; Fagundes, G.M.; Ybarra, N.G.; Abdalla, A.L. Nutritional Potential of Forage Species Found in Brazilian Semiarid Region. Livest. Sci. 2017, 195, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, T.; Deng, K.D.; Jiang, C.G.; Diao, Q.Y. Effect of Urea Supplementation on Performance and Safety in Diets of Dorper Crossbred Sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 100, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukrouh, S.; Noutfia, A.; Moula, N.; Avril, C.; Louvieaux, J.; Hornick, J.-L.; Cabaraux, J.-F.; Chentouf, M. Growth Performance, Carcass Characteristics, Fatty Acid Profile, and Meat Quality of Male Goat Kids Supplemented by Alternative Feed Resources: Bitter Vetch and Sorghum Grains. Arch. Anim. Breed 2024, 67, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, A.; Srinivas, A.; Pauls, G.; Bg, N.; Reddy, R.; HN, C. Methanogen Colonization and ‘End-of-Life’ Use of Spent Lignocellulose from a Solid-State Reactor as an Inoculum Source. Energy 2023, 278, 127856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.C.; Reis, R.B.; Rezende, P.L.d.P.; Wascheck, R.d.C.; Mendonça, A.C.d.; Dutra, A.R. NoProdução Cumulativa de Gases e Parâmetros de France Avaliados Pela Técnica Semiautomática in Vitro de Fontes de Carboidratos de Ruminantes. Rev. Bras. Saúde Prod. Anim. 2010, 11, 452–462. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, B.N.; Reis, R.B.; Maurício, R.M.; Lana, A.M.Q.; Soares, S.R.V.; Saturnino, H.M.; Coelho, S.G. Efeitos Da Adição de Propilenoglicol Ou Monensina à Silagem de Milho Sobre a Cinética de Degradação Dos Carboidratos e Produção Cumulativa de Gases. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2008, 60, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumadong, P.; Cherdthong, A.; So, S.; Wanapat, M. Sulfur, Fresh Cassava Root and Urea Independently Enhanced Gas Production, Ruminal Characteristics and in Vitro Degradability. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.