Towards Decision Support in Precision Sheep Farming: A Data-Driven Approach Using Multimodal Sensor Data

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup and Data Collection

2.2. Machine Learning and Model Evaluation

2.3. Ethical Approval

3. Results

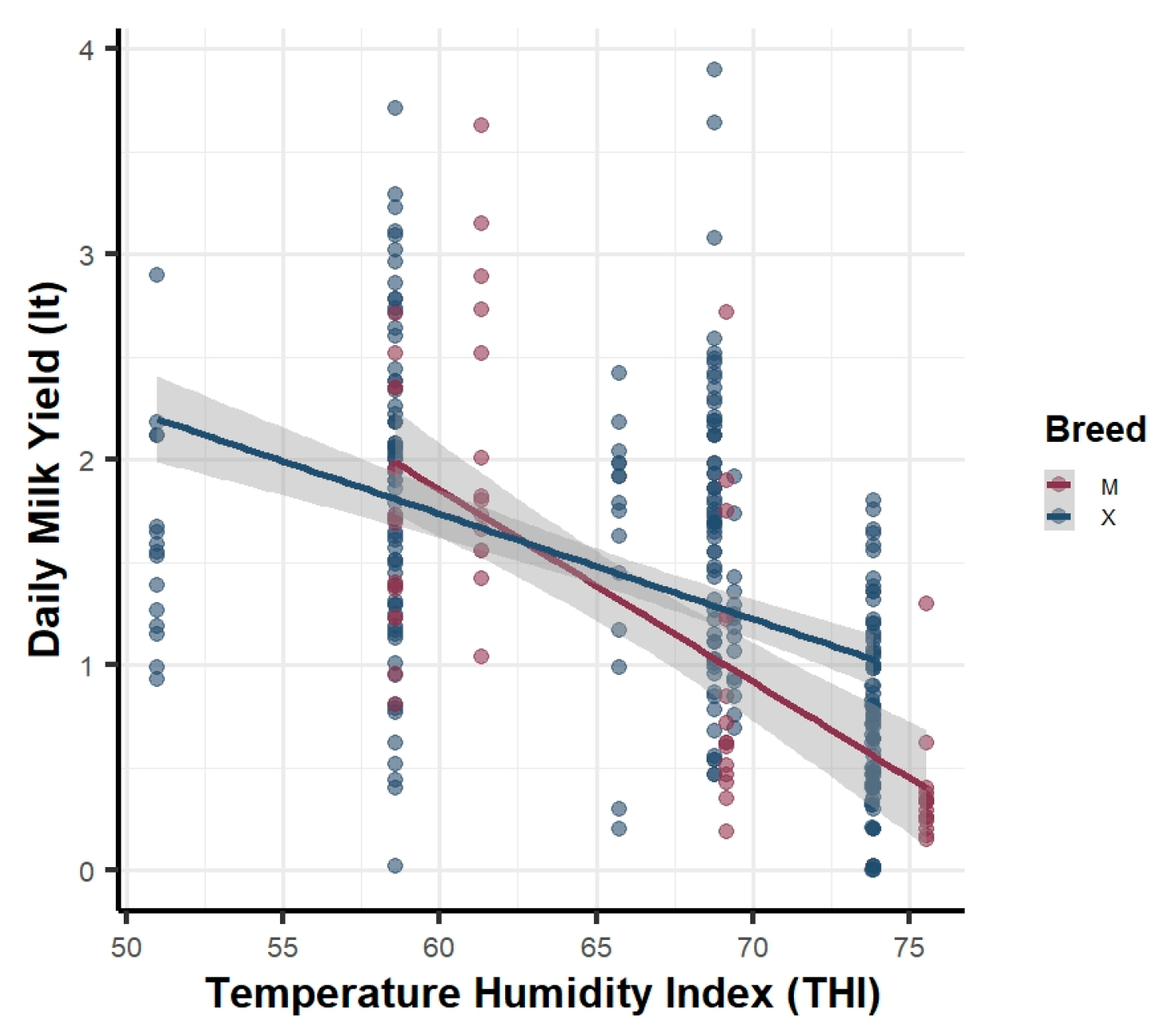

3.1. Descriptive Visualization of Key Relationships

3.2. Model-Specific Results

3.2.1. Linear Regression (LR)

3.2.2. Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR)

3.2.3. Random Forest (RF)

3.2.4. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

3.2.5. Neural Network (MLP)

3.2.6. Elastic Net (EN)

3.2.7. Ensemble Modeling

3.2.8. Mixed-Effects Model

3.2.9. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

3.3. Comparative Model Performance

3.4. Interpretation Across Welfare Indicators

3.4.1. Daily Milk Yield (DMY)

3.4.2. Medial Canthus of the Eye

3.4.3. Respiratory Rate (RR)

3.4.4. Daily Distance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaler, J.; Mitsch, J.; Vázquez-Diosdado, J.A.; Bollard, N.; Dottorini, T.; Ellis, K.A. Automated Detection of Lameness in Sheep Using Machine Learning Approaches: Novel Insights into Behavioural Differences among Lame and Non-Lame Sheep. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 190824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezenwa, V.O.; Archie, E.A.; Craft, M.E.; Hawley, D.M.; Martin, L.B.; Moore, J.; White, L. Host Behaviour–Parasite Feedback: An Essential Link between Animal Behaviour and Disease Ecology. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20153078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, K.; Aerts, J.-M.; Dekock, J.; Bleyaert, P.; Berckmans, D.; Steppe, K. Automated Leaf Temperature Monitoring of Glasshouse Tomato Plants by Using a Leaf Energy Balance Model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 87, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Langford, J.; Fawcett, T.W.; Wilson, A.J.; Croft, D.P. Classifying the Posture and Activity of Ewes and Lambs Using Accelerometers and Machine Learning on a Commercial Flock. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 251, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikurior, S.J.; Marquetoux, N.; Leu, S.T.; Corner-Thomas, R.A.; Scott, I.; Pomroy, W.E. What Are Sheep Doing? Tri-Axial Accelerometer Sensor Data Identify the Diel Activity Pattern of Ewe Lambs on Pasture. Sensors 2021, 21, 6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.; Yubero, R.; Visitación, B.; Navarro-García, J.; Algar, M.J.; Cano, E.L.; Ortega, F. Analysis of Accelerometer and GPS Data for Cattle Behaviour Identification and Anomalous Events Detection. Entropy 2022, 24, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Shu, H.; Hu, T.; Jiang, C.; Yan, R.; Qi, J.; Wang, W.; Guo, L. Behavior Classification and Spatiotemporal Analysis of Grazing Sheep Using Deep Learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachica, M.; Barroso, F.G.; Prieto, C. Seasonal Variation of Locomotion and Energy Expenditure in Goats under Range Grazing Conditions. J. Range Manag. 1997, 50, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caja, G.; Castro-Costa, A.; Salama, A.A.K.; Oliver, J.; Baratta, M.; Ferrer, C.; Knight, C.H. Sensing Solutions for Improving the Performance, Health and Wellbeing of Small Ruminants. J. Dairy Res. 2020, 87, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, E.S.; Swain, D.L.; Cronin, G.M.; Moraes, L.E.; Bailey, D.W.; Trotter, M. Developing a Simulated Online Model That Integrates GNSS, Accelerometer and Weather Data to Detect Parturition Events in Grazing Sheep: A Machine Learning Approach. Animals 2021, 11, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihulay, H.; Abied, A.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y. Adaptation Mechanisms of Small Ruminants to Environmental Heat Stress. Animals 2019, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Taheri, S.; Dunshea, F.R.; Leury, B.J.; DiGiacomo, K.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Brodie, G.; Chauhan, S.S. Non-Invasive Measure of Heat Stress in Sheep Using Machine Learning Techniques and Infrared Thermography. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 207, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, C.; Michie, C.; Hamilton, A.; Tachtatzis, C.; Andonovic, I.; Gilroy, M. Detecting Heat Stress in Dairy Cattle Using Neck-Mounted Activity Collars. Agriculture 2020, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Saikia, T.; Banik, S.; Patil, G.; Pegu, S.R.; Rajkhowa, S.; Sen, A.; Das, P.J. Infrared Imaging a New Non-Invasive Machine Learning Technology for Animal Husbandry. Imaging Sci. J. 2020, 68, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, S.; Gonzalez Viejo, C.; Chauhan, S.S.; Joy, A.; Tongson, E.; Dunshea, F.R. Non-Invasive Sheep Biometrics Obtained by Computer Vision Algorithms and Machine Learning Modeling Using Integrated Visible/Infrared Thermal Cameras. Sensors 2020, 20, 6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.R.; Sacarrão-Birrento, L.; Almeida, M.; Ribeiro, D.M.; Guedes, C.; González Montaña, J.R.; Pereira, A.F.; Zaralis, K.; Geraldo, A.; Tzamaloukas, O.; et al. Extensive Sheep and Goat Production: The Role of Novel Technologies towards Sustainability and Animal Welfare. Animals 2022, 12, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsen, E.; Kutluca Korkmaz, M.; Odevci, B.B. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Selection Strategies in Sheep: Linking Reproductive Traits with Behavioral Indicators. Animals 2025, 15, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, V.; Delbuggio, A.; Cardoso, H.; Fraga, D.; Gómez, A.; Pedemonte, M.; Ungerfeld, R.; Oreggioni, J. Harnessing Technology for Livestock Research: An Online Sheep Behavior Monitoring System. IEEE Trans. AgriFood Electron. 2024, 2, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z, T.B.; Shastry, C. Ewe Health Monitoring Using IoT Simulator. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Information System (ICDSIS), Hassan, India, 29 July 2022; IEEE: Hassan, India, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dikmen, S.; Hansen, P.J. Is the Temperature-Humidity Index the Best Indicator of Heat Stress in Lactating Dairy Cows in a Subtropical Environment? J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vall, E.; Blanchard, M.; Sib, O.; Cormary, B.; González-García, E. Standardized Body Condition Scoring System for Tropical Farm Animals (Large Ruminants, Small Ruminants, and Equines). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2025, 57, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogianni, A.I.; Bouzalas, I.; Bossis, I.; Gelasakis, A.I. Seroepidemiology of Maedi-Visna in Intensively Reared Dairy Sheep: A Two-Year Prospective Study. Animals 2023, 13, 2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadon, A.; Patil, A.; Jadon, S. A Comprehensive Survey of Regression Based Loss Functions for Time Series Forecasting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.02989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.B. A Robust Hybrid of Lasso and Ridge Regression. In Contemporary Mathematics; Verducci, J.S., Shen, X., Lafferty, J., Eds.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2007; Volume 443, pp. 59–71. ISBN 978-0-8218-4195-2. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos López, O.A.; Montesinos López, A.; Crossa, J. Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-89009-4. [Google Scholar]

- Arfuso, F.; Acri, G.; Piccione, G.; Sansotta, C.; Fazio, F.; Giudice, E.; Giannetto, C. Eye Surface Infrared Thermography Usefulness as a Noninvasive Method of Measuring Stress Response in Sheep during Shearing: Correlations with Serum Cortisol and Rectal Temperature Values. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 250, 113781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiura, M.M.; Filipe, J.A.N.; Kyriazakis, I. Mathematical and Statistical Approaches to the Challenge of Forecasting Animal Performance for the Purposes of Precision Livestock Feeding. In Smart Livestock Nutrition; Kyriazakis, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 141–167. ISBN 978-3-031-22584-0. [Google Scholar]

- Agiomavriti, A.-A.; Bartzanas, T.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Gelasakis, A.I. Spectroscopy-Based Methods for Water Quality Assessment: A Comprehensive Review and Potential Applications in Livestock Farming. Water 2025, 17, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiomavriti, A.-A.; Nikolopoulou, M.P.; Bartzanas, T.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Demestichas, K.; Gelasakis, A.I. Spectroscopy-Based Methods and Supervised Machine Learning Applications for Milk Chemical Analysis in Dairy Ruminants. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzarin, M.; Gormley, I.C.; Berry, D.P.; Murphy, T.B.; Casa, A.; Lynch, A.; McParland, S. Predicting Cow Milk Quality Traits from Routinely Available Milk Spectra Using Statistical Machine Learning Methods. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7438–7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and Regression Trees; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Chen, R.; Liang, B.; Li, X. A XGBoost-Based Prediction Method for Meat Sheep Transport Stress Using Wearable Photoelectric Sensors and Infrared Thermometry. Sensors 2024, 24, 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kaur, P.; Gosain, A. A Comprehensive Survey on Ensemble Methods. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 7th International conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Mumbai, India, 7 April 2022; IEEE: Mumbai, India, 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.R.; Cannon, A.J.; Hsieh, W.W. Nonlinear Regression in Environmental Sciences by Support Vector Machines Combined with Evolutionary Strategy. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 50, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaço, A.F.; Richetti, J.; Bramley, R.G.V.; Lawes, R.A. How Will the Next-Generation of Sensor-Based Decision Systems Look in the Context of Intelligent Agriculture? A Case-Study. Field Crops Res. 2021, 270, 108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Table: Resting Respiratory Rates. Available online: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/multimedia/table/resting-respiratory-rates (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Wang, A.; Brito, L.F.; Zhang, H.; Shi, R.; Zhu, L.; Liu, D.; Guo, G.; Wang, Y. Exploring Milk Loss and Variability during Environmental Perturbations across Lactation Stages as Resilience Indicators in Holstein Cattle. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1031557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.A.; Collier, R.J.; Stone, A.E. Invited Review: Physiological and Behavioral Effects of Heat Stress in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 6751–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, S.F.; Silva, M.C.F.; Miranda, J.M.; Stilwell, G.; Cortez, P.P. Predictive Models of Dairy Cow Thermal State: A Review from a Technological Perspective. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploumi, K.; Belibasaki, S.; Triantaphyllidis, G. Some Factors Affecting Daily Milk Yield and Composition in a Flock of Chios Ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 1998, 28, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.L.; Milano, G.D.; Fernández, J.; Alvarado, P.I.; Nadin, L.B. Lack of Agreement among Analysers of Infrared Thermal Images in the Temperature of Eye Regions in Sheep. J. Therm. Biol. 2024, 126, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antanaitis, R.; Džermeikaitė, K.; Bespalovaitė, A.; Ribelytė, I.; Rutkauskas, A.; Japertas, S.; Baumgartner, W. Assessment of Ruminating, Eating, and Locomotion Behavior during Heat Stress in Dairy Cattle by Using Advanced Technological Monitoring. Animals 2023, 13, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essien, D.; Neethirajan, S. Multimodal AI Systems for Enhanced Laying Hen Welfare Assessment and Productivity Optimization. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Chios | Lesvos |

|---|---|---|

| Number of observations | 518 | 255 |

| DMY 1 (kg) | 0.00–1.87 (0.66 ± 0.36) 2 | 0.10–2.10 (0.73 ± 0.48) 2 |

| Daily distance traveled (m) | 0–2668 (1004 ± 576) 2 | 41–5251 (2082 ± 1169) 2 |

| THI 1 | 50.99–75.54 2 | 50.99–75.54 2 |

| NH3 1 (ppm) | 4.67–30.17 2 | 4.67–30.17 2 |

| CO2 1 (ppm) | 474.54–666.65 2 | 474.54–666.65 2 |

| CH4 1 (%) | 0.038–0.065 2 | 0.038–0.065 2 |

| Predictors | LR | PLSR | RF | XGBoost | MLP | EN | Ensemble | Mixed-Effects | SVR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE lt/day | CCC | R2 | RMSE lt/day | MAE

lt/day | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

lt/day |

MAE

lt/day | CCC | |

| 1 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| 2 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| 3 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.41 |

| 4 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| 5 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| 6 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| 7 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.53 |

| 8 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| 9 | 0.29 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.44 |

| 10 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| 11 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| 12 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.45 |

| 13 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| 14 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.54 |

| 15 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| 16 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.54 |

| 17 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.41 |

| 18 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.41 |

| Model | Predictors | RMSE (lt/Day) | MAE (lt/Day) | R2 | CCC | Overfitting | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | ||||

| LR | 1 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.68 | M | M |

| 4 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.59 | 0.51 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.60 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.62 | M | M | |

| 13 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.63 | M | M | |

| 16 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.64 | 0.61 | L | M | |

| PLSR | 1 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.44 | L | W |

| 4 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.49 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.35 | L | W | |

| 10 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0.40 | L | W | |

| 13 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.49 | 0.47 | L | W | |

| 16 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.37 | L | W | |

| RF | 1 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.58 | M | M |

| 4 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.59 | M | M | |

| 7 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 0.60 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.58 | M | M | |

| 13 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.58 | M | M | |

| 16 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.69 | 0.60 | M | M | |

| XGBoost | 1 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.54 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.53 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.70 | 0.59 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 13 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 16 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.58 | M | M | |

| MLP | 1 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.53 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.62 | 0.55 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.57 | L | M | |

| 13 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.62 | 0.56 | M | M | |

| 16 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.57 | L | M | |

| EN | 1 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.47 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.52 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.48 | L | M | |

| 10 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 0.48 | L | M | |

| 13 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.52 | L | M | |

| 16 | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.49 | L | M | |

| Ensemble | 1 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.54 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.56 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.57 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 13 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.55 | M | M | |

| 16 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.57 | M | M | |

| Mixed Effects | 1 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.84 | 0.74 | M | M |

| 4 | 0.32 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.88 | 0.56 | S | M | |

| 7 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.65 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.46 | 0.78 | 0.66 | M | M | |

| 13 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.69 | M | M | |

| 16 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.68 | M | M | |

| SVR | 1 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.49 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.51 | L | M | |

| 7 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.53 | L | M | |

| 10 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.52 | M | M | |

| 13 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.53 | L | M | |

| 16 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| Predictors | LR | PLSR | RF | XGBoost | MLP | EN | Ensemble | Mixed-Effects | SVR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 | RMSE °C | MAE °C | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

°C |

MAE

°C | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

°C |

MAE

°C | CCC | |

| 1 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.73 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.50 | 0.34 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.76 |

| 2 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.75 |

| 3 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.75 |

| 4 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 1.03 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 0.45 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.73 |

| 5 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.46 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.64 |

| 6 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.63 |

| 7 | 0.47 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.34 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.78 |

| 8 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.77 |

| 9 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.76 |

| 10 | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.51 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.79 |

| 11 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.74 |

| 12 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.73 |

| Model | Predictors | RMSE (°C) | MAE (°C) | R2 | CCC | Overfitting | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | ||||

| LR | 1 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.73 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.63 | M | G | |

| 7 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.71 | 0.64 | L | M | |

| 10 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.79 | 0.66 | M | M | |

| PLSR | 1 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.72 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.94 | 1.03 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.51 | L | W | |

| 7 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.58 | L | M | |

| 10 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.75 | 0.66 | M | M | |

| RF | 1 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.81 | M | G |

| 4 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.79 | S | G | |

| 7 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.81 | M | G | |

| 10 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.80 | S | G | |

| XGBoost | 1 | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 0.78 | S | G |

| 4 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 0.80 | S | G | |

| 7 | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.95 | 0.76 | S | G | |

| 10 | 0.17 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.79 | S | G | |

| MLP | 1 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 0.74 | M | M |

| 4 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 0.69 | M | M | |

| 7 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 0.79 | M | G | |

| 10 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 0.68 | M | M | |

| EN | 1 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.72 | L | M |

| 4 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.56 | M | M | |

| 7 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.58 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.77 | 0.68 | M | M | |

| Ensemble | 1 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.90 | 0.78 | S | M |

| 4 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.76 | S | G | |

| 7 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.76 | S | G | |

| 10 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.78 | S | G | |

| Mixed Effects | 1 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.74 | M | M |

| 4 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.45 | 0.79 | 0.64 | M | M | |

| 7 | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.74 | 0.65 | M | M | |

| 10 | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.68 | M | M | |

| SVR | 1 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.76 | M | M |

| 4 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.85 | 0.73 | M | M | |

| 7 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.78 | M | G | |

| 10 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.79 | S | G | |

| Predictors | LR | PLSR | RF | XGBoost | MLP | EN | Ensemble | Mixed-Effects | SVR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 | RMSE ** | MAE ** | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

** |

MAE

** | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

** |

MAE

** | CCC | |

| 1 | 0.36 | 15.8 | 11.0 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 16.6 | 11.8 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 13.5 | 9.22 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 15.3 | 10.2 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 15.0 | 10.3 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 15.3 | 10.8 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 14.1 | 9.37 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 15.4 | 10.8 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 14.0 | 9.31 | 0.51 |

| 2 | 0.21 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 13.1 | 9.14 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 13.2 | 9.07 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 14.0 | 9.80 | 0.50 | 0.21 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 13.5 | 9.47 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 15.5 | 11.1 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 14.9 | 10.3 | 0.36 |

| 3 | 0.19 | 14.5 | 10.5 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 14.5 | 10.5 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 13.0 | 9.20 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 13.3 | 9.21 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 14.2 | 10.2 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 14.5 | 10.5 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 13.5 | 9.52 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 15.8 | 11.7 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 14.7 | 10.2 | 0.36 |

| 4 | 0.24 | 15.9 | 11.2 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 12.9 | 8.91 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 14.6 | 9.64 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 15.0 | 10.8 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 13.6 | 9.09 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 15.4 | 10.8 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 0.40 |

| 5 | 0.21 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 12.9 | 9.02 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 13.2 | 9.10 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 13.8 | 9.85 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 14.8 | 10.6 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 13.2 | 9.35 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 15.0 | 10.6 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 14.6 | 10.3 | 0.44 |

| 6 | 0.19 | 14.6 | 10.5 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 14.6 | 10.5 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 12.9 | 9.10 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 13.1 | 9.29 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 14.1 | 10.0 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 14.6 | 10.5 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 13.3 | 9.47 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 15.1 | 10.8 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 14.9 | 10.4 | 0.37 |

| 7 | 0.19 | 16.4 | 11.7 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 15.6 | 11.2 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 12.7 | 8.72 | 0.59 | 0.45 | 14.4 | 9.50 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 13.5 | 9.56 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 15.6 | 11.1 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 13.6 | 9.11 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 16.0 | 11.3 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 14.1 | 9.57 | 0.45 |

| 8 | 0.18 | 15.1 | 10.8 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 15.1 | 10.8 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 12.8 | 8.93 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 13.1 | 9.04 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 13.9 | 9.93 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 15.1 | 10.8 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 13.2 | 9.36 | 0.51 | 0.21 | 15.5 | 11.1 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 14.8 | 10.3 | 0.40 |

| 9 | 0.16 | 14.8 | 10.8 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 14.8 | 10.8 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 12.7 | 8.97 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 13.0 | 9.15 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 13.8 | 9.80 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 14.8 | 10.7 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 13.3 | 9.50 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 15.5 | 11.3 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 14.1 | 9.98 | 0.41 |

| 10 | 0.26 | 15.3 | 11.0 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 16.6 | 11.6 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 12.9 | 8.79 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 14.5 | 9.67 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 13.6 | 9.71 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 13.5 | 8.96 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 14.9 | 10.7 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 14.0 | 9.48 | 0.47 |

| 11 | 0.20 | 14.9 | 10.7 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 14.8 | 10.7 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 12.9 | 9.00 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 13.2 | 9.16 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 14.1 | 9.73 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 14.9 | 10.7 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 13.3 | 9.37 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 14.6 | 10.6 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 14.2 | 10.0 | 0.48 |

| 12 | 0.18 | 14.6 | 10.7 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 14.6 | 10.7 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 12.7 | 9.00 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 13.3 | 9.44 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 14.7 | 10.7 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 13.3 | 9.47 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 14.9 | 10.9 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 14.1 | 10.0 | 0.45 |

| 13 | 0.21 | 17.5 | 12.3 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 15.3 | 10.9 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 13.3 | 9.14 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 14.6 | 10.2 | 0.50 | 0.18 | 15.7 | 11.1 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 14.0 | 9.64 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 17.0 | 11.9 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 13.6 | 9.24 | 0.53 |

| 14 | 0.21 | 14.8 | 10.4 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 15.0 | 10.7 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 13.0 | 9.11 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 0.55 | 0.28 | 14.3 | 10.3 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 14.8 | 10.5 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 13.2 | 9.31 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 16.6 | 12.2 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 14.5 | 10.3 | 0.40 |

| 15 | 0.19 | 14.5 | 10.4 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 14.8 | 10.7 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 13.2 | 9.45 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 0.53 | 0.17 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 14.5 | 10.4 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 13.2 | 9.37 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 16.6 | 12.4 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 14.3 | 10.3 | 0.43 |

| Model | Predictors | RMSE (Breaths/min) | MAE (Breaths/min) | R2 | CCC | Overfitting | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | ||||

| LR | 1 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.46 | L | M |

| 4 | 14.8 | 15.9 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.37 | L | M | |

| 7 | 15.2 | 16.4 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.30 | L | W | |

| 10 | 14.7 | 15.3 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.38 | L | M | |

| 13 | 16.2 | 17.5 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.33 | L | W | |

| PLSR | 1 | 15.5 | 16.6 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.32 | L | W |

| 4 | 14.4 | 10.1 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.37 | L | M | |

| 7 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.30 | L | W | |

| 10 | 15.5 | 16.6 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0.32 | L | W | |

| 13 | 14.4 | 56.1 | 10.3 | 14.4 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.05 | S | W | |

| RF | 1 | 9.70 | 13.6 | 6.87 | 9.29 | 0.68 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.52 | M | M |

| 4 | 11.1 | 13.1 | 7.78 | 8.95 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.66 | 0.57 | L | M | |

| 7 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 7.71 | 8.74 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.60 | L | M | |

| 10 | 11.1 | 12.9 | 7.75 | 8.82 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.59 | L | M | |

| 13 | 7.72 | 13.3 | 5.57 | 9.17 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.84 | 0.54 | S | M | |

| XGBoost | 1 | 11.6 | 15.3 | 7.93 | 10.2 | 0.69 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.44 | M | M |

| 4 | 12.6 | 14.6 | 8.53 | 9.64 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.50 | M | M | |

| 7 | 12.8 | 14.4 | 8.60 | 9.50 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.50 | L | M | |

| 10 | 12.9 | 14.5 | 8.59 | 9.67 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.50 | L | M | |

| 13 | 4.09 | 15.3 | 1.65 | 10.4 | 0.94 | 0.27 | 0.97 | 0.50 | S | M | |

| MLP | 1 | 11.8 | 15.0 | 8.45 | 10.3 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.63 | 0.47 | M | M |

| 4 | 11.8 | 15.0 | 8.49 | 10.8 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.45 | M | M | |

| 7 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 9.47 | 9.56 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.52 | L | M | |

| 10 | 11.8 | 13.6 | 8.24 | 9.71 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.55 | L | M | |

| 13 | 11.9 | 14.6 | 8.53 | 10.3 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.50 | M | M | |

| EN | 1 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 10.2 | 10.8 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.35 | L | W |

| 4 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.36 | L | W | |

| 7 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.29 | L | W | |

| 10 | 14.4 | 15.2 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.33 | L | W | |

| 13 | 14.7 | 15.8 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.26 | L | W | |

| Ensemble | 1 | 11.1 | 14.1 | 7.56 | 9.37 | 0.61 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.46 | M | M |

| 4 | 12.0 | 13.6 | 8.13 | 9.09 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 0.51 | L | M | |

| 7 | 12.1 | 13.6 | 8.14 | 9.11 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.50 | L | M | |

| 10 | 12.1 | 13.5 | 8.19 | 8.96 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.51 | L | M | |

| 13 | 7.84 | 14.0 | 5.73 | 9.68 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 0.83 | 0.47 | S | M | |

| Mixed Effects | 1 | 14.6 | 15.4 | 10.6 | 10.8 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.49 | L | M |

| 4 | 13.7 | 15.4 | 9.70 | 10.8 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.42 | L | M | |

| 7 | 14.3 | 16. | 10.3 | 11.3 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.34 | L | W | |

| 10 | 13.5 | 14.9 | 9.68 | 10.7 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.43 | L | M | |

| 13 | 15.2 | 17.0 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.38 | L | M | |

| SVR | 1 | 11.3 | 14.0 | 7.18 | 9.31 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.51 | M | M |

| 4 | 13.3 | 14.7 | 8.62 | 10.0 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.40 | L | M | |

| 7 | 12.9 | 14.1 | 8.36 | 9.57 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.45 | L | M | |

| 10 | 12.8 | 14.0 | 8.39 | 9.48 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.47 | L | M | |

| 13 | 11.0 | 13.6 | 7.16 | 9.26 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0.66 | 0.54 | M | M | |

| Predictors | LR | PLSR | RF | XGBoost | MLP | EN | Ensemble | Mixed-Effects | SVR | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 | RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

(m) |

MAE

(m) | CCC | R2 |

RMSE

(m) |

MAE

(m) | CCC | |

| 1 | 0.40 | 704 | 582 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 923 | 717 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 598 | 469 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 616 | 477 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 686 | 550 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 753 | 627 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 624 | 500 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 603 | 498 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 632 | 501 | 0.72 |

| 2 | 0.45 | 712 | 573 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 713 | 573 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 568 | 436 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 592 | 447 | 0.77 | 0.48 | 687 | 543 | 0.66 | 0.45 | 712 | 573 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 598 | 468 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 588 | 477 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 650 | 493 | 0.72 |

| 3 | 0.39 | 759 | 614 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 759 | 614 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 645 | 501 | 0.66 | 0.49 | 698 | 540 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 779 | 618. | 0.51 | 0.39 | 758 | 614 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 671 | 527 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 711 | 572 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 739 | 570 | 0.54 |

| 4 | 0.29 | 748 | 615 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 749 | 617 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 593 | 470 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 614 | 487 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 736 | 590 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 738 | 602 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 613 | 493 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 688 | 560 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 668 | 529 | 0.67 |

| 5 | 0.44 | 710 | 575 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 710 | 575 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 565 | 436 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 583 | 445 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 649 | 511 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 710 | 575 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 595 | 466 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 673 | 535 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 680 | 521 | 0.67 |

| 6 | 0.39 | 763 | 621 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 761 | 619 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 652 | 509 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 687 | 537 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 738 | 595 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 763 | 621 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 672 | 529 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 762 | 622 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 743 | 575 | 0.53 |

| 7 | 0.28 | 729 | 585 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 803 | 688 | 0.41 | 0.62 | 586 | 458 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 616 | 489 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 730 | 601 | 0.58 | 0.35 | 764 | 631 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 616 | 492 | 0.71 | 0.39 | 667 | 539 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 643 | 513 | 0.71 |

| 8 | 0.40 | 735 | 590 | 0.57 | 0.40 | 734 | 590 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 565 | 433 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 582 | 450 | 0.77 | 0.48 | 698 | 547 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 735 | 590 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 594 | 467 | 0.75 | 0.38 | 619 | 512 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 692 | 526 | 0.67 |

| 9 | 0.34 | 784 | 634 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 783 | 634 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 643 | 501 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 685 | 528 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 768 | 619 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 783 | 634 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 671 | 528 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 717 | 559 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 714 | 552 | 0.58 |

| 10 | 0.30 | 761 | 637 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 785 | 656 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 592 | 463 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 605 | 481 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 643 | 513 | 0.70 | 0.34 | 772 | 634 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 614 | 486 | 0.71 | 0.42 | 687 | 568 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 626 | 493 | 0.72 |

| 11 | 0.39 | 739 | 591 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 738 | 591 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 563 | 430 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 577 | 442 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 693 | 543 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 739 | 591 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 591 | 462 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 675 | 540 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 664 | 507 | 0.71 |

| 12 | 0.34 | 785 | 633 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 785 | 633 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 648 | 502 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 696 | 536 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 746 | 600 | 0.56 | 0.34 | 784 | 633 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 673 | 528 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 773 | 627 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 718 | 555 | 0.59 |

| 13 | 0.38 | 714 | 591 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 766 | 628 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 596 | 470 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 613 | 487 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 662 | 516 | 0.69 | 0.43 | 712 | 582 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 613 | 497 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 623 | 517 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 656 | 518 | 0.69 |

| 14 | 0.49 | 685 | 559 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 686 | 559 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 560 | 431 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 577 | 440 | 0.79 | 0.50 | 679 | 539 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 685 | 559 | 0.65 | 0.62 | 585 | 459 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 617 | 503 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 679 | 519 | 0.67 |

| 15 | 0.43 | 738 | 601 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 738 | 600 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 661 | 514 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 698 | 538 | 0.63 | 0.45 | 729 | 590 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 737 | 601 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 669 | 527 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 725 | 592 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 726 | 564 | 0.53 |

| 16 | 0.33 | 708 | 586 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 780 | 665 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 589 | 471 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 605 | 485 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 681 | 545 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 728 | 598 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 604 | 492 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 632 | 523 | 0.66 | 0.52 | 661 | 517 | 0.69 |

| 17 | 0.45 | 707 | 571 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 705 | 570 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 570 | 446 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 586 | 452 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 666 | 522 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 707 | 571 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 595 | 471 | 0.75 | 0.41 | 602 | 490 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 682 | 514 | 0.69 |

| 18 | 0.39 | 759 | 617 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 758 | 616 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 650 | 509 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 690 | 535 | 0.63 | 0.39 | 760 | 601 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 759 | 617 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 667 | 528 | 0.63 | 0.30 | 686 | 544 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 709 | 542 | 0.59 |

| Model | Predictors | RMSE (m/Day) | MAE (m/Day) | R2 | CCC | Overfitting | Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | ||||

| LR | 1 | 630 | 704 | 505 | 582 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.58 | M | M |

| 4 | 700 | 748 | 568 | 615 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.48 | M | M | |

| 7 | 573 | 729 | 445 | 585 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.47 | M | M | |

| 10 | 710 | 761 | 562 | 637 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.49 | L | M | |

| 13 | 658 | 714 | 537 | 591 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.56 | L | M | |

| 16 | 548 | 708 | 419 | 586 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.53 | M | M | |

| PLSR | 1 | 824 | 923 | 606 | 717 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 0.37 | M | W |

| 4 | 699 | 749 | 570 | 617 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 7 | 779 | 803 | 635 | 688 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.41 | L | M | |

| 10 | 734 | 785 | 576 | 656 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.48 | L | M | |

| 13 | 713 | 766 | 569 | 628 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.52 | L | M | |

| 16 | 748 | 780 | 607 | 665 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.46 | L | M | |

| RF | 1 | 465 | 598 | 351 | 474 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.75 | M | G |

| 4 | 458 | 594 | 342 | 471 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.75 | M | G | |

| 7 | 456 | 587 | 347 | 466 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.75 | M | G | |

| 10 | 466 | 588 | 352 | 466 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.75 | M | G | |

| 13 | 464 | 595 | 650 | 474 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.75 | S | G | |

| 16 | 439 | 589 | 335 | 470 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.87 | 0.75 | M | G | |

| XGBoost | 1 | 425 | 616 | 314 | 477 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.74 | M | G |

| 4 | 423 | 614 | 316 | 487 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.73 | M | G | |

| 7 | 395 | 616 | 293 | 489 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 0.73 | M | G | |

| 10 | 420 | 605 | 313 | 481 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.88 | 0.74 | M | G | |

| 13 | 414 | 613 | 306 | 487 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.74 | M | G | |

| 16 | 408 | 605 | 309 | 485 | 0.82 | 0.59 | 0.89 | 0.74 | M | G | |

| MLP | 1 | 523 | 701 | 404 | 561 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.66 | M | M |

| 4 | 602 | 736 | 473 | 590 | 0.59 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.61 | M | M | |

| 7 | 631 | 730 | 499 | 601 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 0.58 | M | M | |

| 10 | 565 | 643 | 428 | 513 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.78 | 0.70 | L | G | |

| 13 | 560 | 662 | 441 | 516 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.69 | M | M | |

| 16 | 570 | 681 | 442 | 545 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.66 | M | M | |

| EN | 1 | 680 | 753 | 543 | 627 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.65 | 0.55 | M | M |

| 4 | 691 | 738 | 559 | 602 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.57 | L | M | |

| 7 | 708 | 764 | 563 | 631 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 10 | 712 | 772 | 561 | 634 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.60 | 0.54 | L | M | |

| 13 | 663 | 712 | 543 | 582 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 0.61 | L | M | |

| 16 | 686 | 728 | 555 | 598 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.58 | L | M | |

| Ensemble | 1 | 487 | 624 | 382 | 500 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.71 | M | G |

| 4 | 485 | 613 | 384 | 493 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.83 | 0.71 | M | G | |

| 7 | 483 | 616 | 379 | 492 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.83 | 0.71 | M | G | |

| 10 | 494 | 614 | 386 | 486 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.82 | 0.71 | M | G | |

| 13 | 480 | 613 | 380 | 497 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.72 | M | G | |

| 16 | 475 | 604 | 377 | 492 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.84 | 0.72 | M | G | |

| Mixed Effects | 1 | 531 | 603 | 429 | 498 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.72 | L | G |

| 4 | 618 | 688 | 496 | 560 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.59 | M | M | |

| 7 | 448 | 667 | 351 | 539 | 0.63 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0.58 | M | M | |

| 10 | 623 | 687 | 498 | 568 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.68 | 0.61 | L | M | |

| 13 | 560 | 623 | 454 | 517 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.69 | L | M | |

| 16 | 390 | 632 | 300 | 523 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.66 | S | M | |

| SVR | 1 | 478 | 632 | 341 | 501 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.72 | M | G |

| 4 | 511 | 668 | 371 | 529 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.67 | M | M | |

| 7 | 438 | 643 | 298 | 513 | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.88 | 0.71 | M | G | |

| 10 | 456 | 626 | 319 | 493 | 0.77 | 0.56 | 0.87 | 0.72 | M | G | |

| 13 | 550 | 656 | 416 | 518 | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.79 | 0.69 | M | M | |

| 16 | 481 | 661 | 346 | 517 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.85 | 0.69 | M | M | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nikolopoulou, M.P.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Demestichas, K.; Kalogianni, A.I.; Papada, I.; Lamprou, P.A.; Chalkos, A.; Manavis, E.; Bartzanas, T. Towards Decision Support in Precision Sheep Farming: A Data-Driven Approach Using Multimodal Sensor Data. Ruminants 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants6010003

Nikolopoulou MP, Gelasakis AI, Demestichas K, Kalogianni AI, Papada I, Lamprou PA, Chalkos A, Manavis E, Bartzanas T. Towards Decision Support in Precision Sheep Farming: A Data-Driven Approach Using Multimodal Sensor Data. Ruminants. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleNikolopoulou, Maria P., Athanasios I. Gelasakis, Konstantinos Demestichas, Aphrodite I. Kalogianni, Iliana Papada, Paraskevas Athanasios Lamprou, Antonios Chalkos, Efstratios Manavis, and Thomas Bartzanas. 2026. "Towards Decision Support in Precision Sheep Farming: A Data-Driven Approach Using Multimodal Sensor Data" Ruminants 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants6010003

APA StyleNikolopoulou, M. P., Gelasakis, A. I., Demestichas, K., Kalogianni, A. I., Papada, I., Lamprou, P. A., Chalkos, A., Manavis, E., & Bartzanas, T. (2026). Towards Decision Support in Precision Sheep Farming: A Data-Driven Approach Using Multimodal Sensor Data. Ruminants, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants6010003