Abstract

The aim of this article is to explore the relationship between urban design and social capital in the existing literature. Through a systematic quantitative literature review (SQLR) approach, this study seeks to offer insights into this relationship, investigating trends and gaps. The review revealed that the relationship is complex and not well defined. It emphasised a consistency across the literature of references to the key historical figures and movements. Two major themes emerged as key topics of interest in the reviewed literature: the built environment outcomes and community participation. The research also revealed that the relationship between urban design and social capital is underexplored, with a lack of contemporary relevant references contributing to this topic. This deficiency results in a body of academic literature that does not fully address or reflect current industry practices and innovations. The review concludes that there is a need to shift focus globally. We need to incorporate multicultural references and case studies to learn from diverse contexts as well as multi-level collaborations between the designer and community to prepare for the different challenges that communities are currently grappling with.

1. Introduction

According to [1] (pp. 19–20), the phrase ‘social capital’ was first used in 1916 by Lyda Hanifan in a paper exploring the role played by the community in developing public schools in rural West Virginia [1] (pp. 19–20). Hanifan uses the phrase to describe the “goodwill, fellowship, sympathy and social intercourse” that make up a community [1] (pp. 19–20). Since then, the definition of social capital has been refined and can be viewed as the “building up of social connections and sociability” [2] (p. 2) and the “networks and resources available to people through their connections to others” [3] (pp. 2–5).

Furthermore, scholars from various disciplines, including sociology, political science, and economics, have also contributed to the understanding of social capital. For example, sociologist Pierre Bourdieu contributed to the scholarship during the 1970s–1990s by emphasising how social capital is linked to economic and cultural capital, which can perpetuate power dynamics and social inequality [4] (pp. 39, 49). In the late 1980s, James Coleman, another sociologist, further contributed to the evolution of social capital theory, leading to the view of social capital as a resource individuals gain from capitalising on social relationships [4] (p. 40). The political scientist Robert Putnam’s seminal work “Bowling Alone” (2000) popularised the term, highlighting the decline of social capital in American society and its consequences for civic engagement and democracy [1].

At a community level, social capital can be a tool to demonstrate why some communities can easily mobilise themselves [5]. It also helps to quantify ‘trust’ (as a necessary condition for commerce) [6] and prompt the community to invest in long-term projects. In contrast, scholarship found that a community without an initial amount of social capital relies on top-down coordination from governing bodies and will most likely face trouble achieving a state of self-sustainment [7] (p. 8). The presence of social interactions within a neighbourhood can lead to social bonding and foster a sense of belonging and ownership [8]. When residents feel connected to each other, they work together to resolve local problems, leading to lower rates of crime and disorder [9], and recover more swiftly from shocks [10,11]. Additionally, scholarship has shown that amidst community challenges like rising loneliness [12], declining social cohesion [13], and increasing global urban vulnerabilities [14], social capital emerges as a critical asset [15] (pp. 112–139).

Urban design as a profession is known for its pivotal role in designing spaces with and for the community. Urban design can be defined as “the process of shaping better places for people than would otherwise be produced” [16] (p. 3). Urban design evolved from ‘civic design’, which focused largely on city beautification and major civic buildings, to a more expansive approach that designs urban spaces for people to enjoy and benefit from [16] (p. 3). Thoughtful urban design principles, within the built form and design process, can encourage interaction, collaboration, and a sense of belonging among residents [17] (pp. 5–11, 83). Carmona contributes to this view when stating “pedestrian movement is compatible with the notion of streets as social space, and there is a symbiotic relationship between pedestrian movement and economic, social and cultural exchange” [16] (p. 83).

The urban design process is difficult to define, as there can be many variations and ways different cultural contexts view the process. The process of design itself can be summarised as a series of sequences that include the conception of an idea to preliminary sketches and the formulation and synthesis of these towards making plans, strategies, and drawings necessary for the construction of the design [18]. The scale of this process can be both micro (street, building, neighbourhood) and macro (regional, city, state). Due to the multidisciplinary nature of the practice of urban design, it often involves collaboration and coordination across various disciplines, such as planning, architecture, landscape architecture, environmental and engineering, and working with the community to develop a project outcome.

Within this context, community engagement is a key component of the urban design process, shaping the physical and social fabric of neighbourhoods and cities. Effective community engagement strategies, such as participatory design workshops and public forums, enable residents to voice their needs, preferences, and concerns, ultimately leading to more responsive and equitable urban spaces that reflect the collective identity and aspirations of the people who inhabit them [19].

Urban designers are grappling with providing sustainable solutions for community dealing with serious societal issues [20]. However, for urban design to be genuinely sustainable, a deep understanding of the community, including its local attributes, opportunities, values, and the physical environment, is essential [21] (p. 49). Yet even though existing scholarship offers abundant studies either on urban design or social capital, the scrutinization of their relationship remains underexplored. Thus, investigating the relationship between urban design and social capital may offer pathways to more responsive, inclusive, and effective urban design strategies, ultimately aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [22] (p. 16).

This is the aim of this literature review, which investigates five main categories: geographic location, definitions, methods, key figures and movements, and key themes. By focusing on key figures, movements, and themes identified in the literature, this review seeks to understand the focal points of research interest. This comprehensive exploration allows for a nuanced understanding of how different contexts, perspectives, and approaches discuss the relationship between urban design and social capital.

This contribution is divided into three sections. The first section foregrounds the approach to the systematic quantitative literature review (SQLR) and the databases from which the literature were gathered. The Section 2 summarises the results, while the Section 3 discusses and reflects on the results and gaps, providing some recommendations. The Section 5 is the conclusion, which provides the summary of the review. The contribution of this study is expected to provide a synthesised perspective on the current state of knowledge regarding the relationship between social capital and urban design, offering insights that can inform future research directions and practices on this research topic.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a SQLR method to investigate the relationship between urban design and social capital. This method, as advocated by [23], is based on a systematic approach, ensuring reliability and validity in data synthesis and analysis. This method is esteemed for the ability to produce knowledge on both what is known in the literature and what the identified gaps are, through coding results in a quantifiable measure, categorising results and producing summary tables of the collected data that can be repeated for transparency [24,25]. This section outlines the steps of this method, encompassing topic identification, database selection, screening criteria, data collection, and analysis techniques.

2.1. Category Formulation

Following SQLR’s guidelines [23], specific categories were formulated to guide the review process. These five were geographic locations, definitions, methods, key figures and movements, and key themes. Table 1 details the questions at the origin of these categories.

Table 1.

Categories based on SQLR method [23].

The selection of these categories is driven by several reasons. First, investigating the geographic locations, definitions, and methods employed in the reviewed literature is essential for establishing a contextual overview and understanding the various approaches that discussed this relationship. Specifically regarding the definition category, both urban design and social capital have been criticised as ambiguous because they lack an overarching definition and measurability [26,27]. Hence, it was deemed important to investigate this aspect further. Second, extracting key figures and movements helps in identifying the driving forces behind discussions on urban design and social capital and in understanding their influence while questioning their relevance today. Third, identifying overarching themes distils complex information into key insights that may guide future research directions and industry practices. Together, these categories contribute to a comprehensive examination of the relationship between social capital and urban design, enriching our understanding of how this relationship is perceived and studied in the academic literature while revealing trends and gaps.

2.2. Database Selection and Search Strategy

There were two phases of database selection and search strategy. In phase one, Science Direct and Web of Science were selected to ensure comprehensive reporting of the relevant literature. These databases were chosen based on their extensive multidisciplinary coverage, aligning with the recommendation by [23] to access cross-disciplinary knowledge.

The search process commenced with the initial keywords (“urban design” and “social capital”) and a comprehensive suite of keywords deemed related to either phrase. “Built environment”, “public space”, “placemaking” were chosen to reflect both the outcomes and process of urban design. “Social tie*”, “community* trust”, and “social cohesion” stemmed from the literature as different components of social capital. This first search yielded 7263 articles across Web of Science and Science Direct. However, upon initial scanning of the retrieved articles, it became apparent that many were not directly pertinent to this specific study. This necessitated a discerning approach to filter out articles that did not align with the focus on urban design and social capital.

In delineating the definitions of “urban design” and “social capital” within the framework of this study, it became evident that both concepts embody dual components: urban design encompasses both ‘process’ and ‘outcome’ of built environment, while social capital involves the nature and structure of social relations and their benefits. Terms like “public space”, “placemaking”, and “participatory design”, though related, did not fully represent urban design. Similarly, terms like “social cohesion”, “social tie”, and “community trust” were components of social capital but did not fully capture its essence. “Neighborhood design” was, however, recognised as being closely related to urban design; hence, it was chosen as a keyword. This decision accounted for variations in terminology used in different countries, where “neighbourhood design” might be more prevalent than “urban design”. For consistency, the term “urban design” will be used throughout the review to refer to both concepts, except when specifically labelled.

Therefore, to maintain research focus, only the key words “urban design” and “social capital” or “neighbo*rhood design” and “social capital” were involved in the search, excluding other terms that did not align with the holistic nature of these concepts. This process ensured a targeted and coherent approach to literature selection, facilitating a focused data collection aligned with the research topic.

In phase two, it was recognised that an additional database was required to expand the search results. Pub Med was selected after suggestion from one peer-reviewer.

2.3. Screening and Inclusion Criteria

Retrieved articles underwent screening to determine their relevance and suitability for inclusion. Inclusion criteria, guided by the principles outlined by [23], encompassed peer-reviewed articles, and all disciplines and publication years were entered. This was to understand the full breadth of research on this topic.

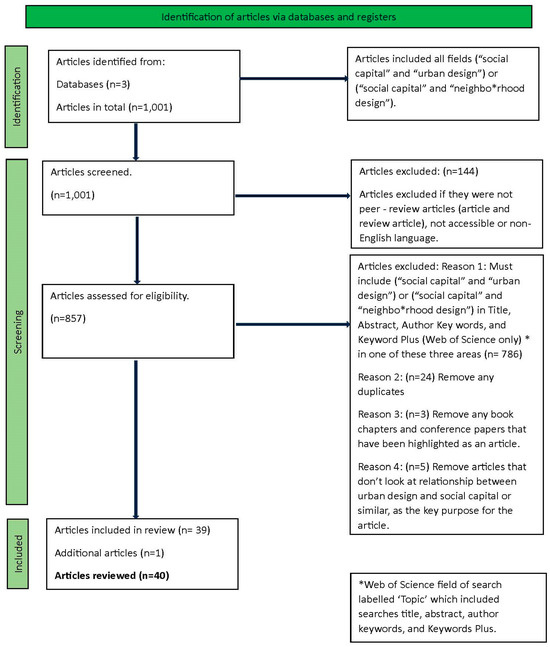

The number of retained papers was still considerable (857 articles); thus, exclusion criteria were then adopted. First, articles needed to have either “urban design” and “social capital” or “neighbo*rhood design” and “social capital” in either the ‘Title, Abstract and/or Keyword search.’ This allowed for screening articles with a strong focus on our research topic. This resulted in 71 articles. These articles were then manually read to screen their relevance and avoid repetition. At this stage, duplicates, non-peer-reviewed articles, and irrelevant peer-reviewed articles were removed (see details in Figure 1). The addition of Pub Med as a database only revealed one additional article after inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. At last, one extra article was added for this review, as it was referenced across multiple selected articles. Overall, this process revealed a total of 40 articles, which were reviewed for the purpose of this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of SQLR process. Visualisation of process adapted from PRISMA [28].

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

To facilitate the analysis, data extraction involved the creation of a comprehensive database, recording essential information in alignment with the five chosen categories. A mixed-method approach was employed for data analysis, combining qualitative interpretation and quantitative measures (mostly for the geographic location, definitions, methods and key figures, and movement categories). Themes were extracted through a qualitative approach by manually reading each article to understand the overall theme(s) of the article. Two typical themes were made clear. Furthermore, quantitative measures were used to evaluate the weight of each theme within the reviewed literature.

In the same way, extracted and quantified references to certain historical figures and movements were then qualitatively analysed to understand their influence in the reviewed research. Certain components deemed less relevant to the article’s focus were excluded from the final analysis, such as an in-depth analysis on methodologies, based on the depth provided in other reviewed literature [29].

This approach enabled a nuanced understanding of the research landscape, which revealed emerging themes and repeated references influencing the discourse.

2.5. Conceptual Framework

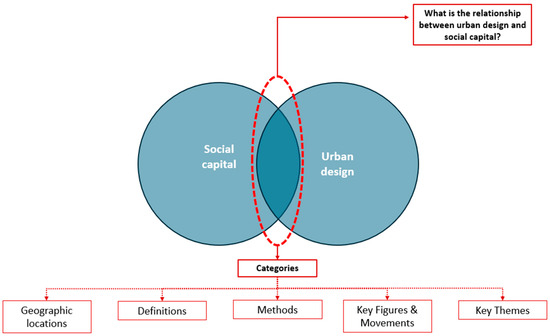

The conceptual framework (Figure 2) provides a guiding model for understanding the components of the research topic under investigation. The research aims to explore the relationship between social capital and urban design in the literature. Hence, to undertake this study, an understanding of key components such as the geographic location, key figures and movements, and key themes uncovered from the research, were significant to conceptualising this relationship.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework.

2.6. Limitations

The main limitations concern the restriction to English-language publications that prevented access to other cultural contexts, the database choice that may skew the results, and the refined keyword search strategy that may have overlooked other important keywords. While these limitations may have constrained the scope of the review, efforts were made to mitigate potential biases and ensure the robustness of the findings through the methodological process adopted. Additionally, the systematic application of the SQLR method facilitated a thorough examination of the existing literature, providing valuable insights into the complex relationship between urban design and social capital.

By adhering to established guidelines and integrating both quantitative and qualitative analyses, this study provides a nuanced understanding of the research landscape, recognising key themes and avenues for future investigation.

3. Results

Within this literature review, six main results were identified. Five correspond to our five categories, and one directly answers the initial research question of this review.

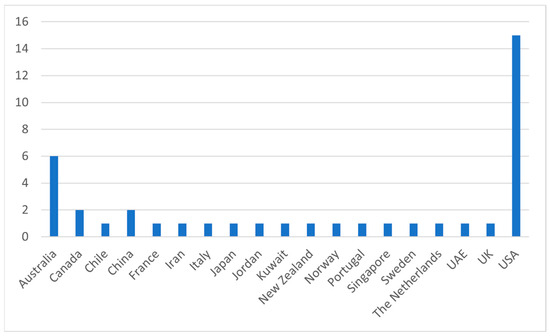

3.1. Geographic Distribution

The geographic distribution of researchers’ locations was focused heavily on the United States of America (16), followed by Australia (6), Canada (2), and China (2), while all other 14 countries equalled 1 article each (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of the articles’ primary authors.

3.2. Definitions

Overall, 31 out of 40 articles contained a definition of social capital (see Table 2). Some definitions expressed social capital as “a set of features inherent in social relationships based in trust and cooperation” [30] or “the glue that holds society together” [31] and the “collective value of social networks” [32]. The most common definition was derived from one source [1]: “connections among individuals, social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them”.

Table 2.

The frequency of the given definitions in the reviewed articles. (√ represents if an article included a definition.)

On the contrary, only three articles defined urban design, and none defined neighbourhood design (Table 2). Five articles either defined neighbourhood, community design, or the built environment (described as ‘Other’ in Table 2). Definitions of urban design in the literature contained “integrative role within the governance of the built environment of aiding a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach” [26]; “a vehicle for integrating physical form, public policy, and socioeconomic, historical, and environmental aspects” [41]; or “placemaking for people” [30].

3.3. Methods Used in the Reviewed Articles

Out of the 40 reviewed articles, 15 used surveys for data collection (including cross comparison with desktop research), 6 mixed methods (combination of survey, questionnaire and/or interviews), 2 semi-structured interviews/focus groups, and 1 questionnaire. Also, 11 articles were literature reviews on their own. Five articles were classified as ‘other’, which comprised a review of an analytical framework [54], empirical research, and semi narrative literature review [50], and three analysed particular case studies, including desktop, literature analysis, and action research [34,44,52]. Five literature reviews had specific focuses similar to this research topic; however, with slight variations. For example, a topic comprised the relationship between the built environment and social capital [29], the relationship of urban design to human health [38], the relationship between resilience and urban design [26], an analysis of theoretical urban neighbourhood concepts with social capital [27], and the relationship between social capital and the psychology of health and place [61].

3.4. Key Figures and Movements

The two key figures who most featured in the reviewed literature were Jane Jacobs and Robert Putnam. Furthermore, the movements of New Urbanism and Community/ Public Health were also repeatedly invoked (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quantitative data of contextual influences. (“√” represents inclusion of finding in article).

3.4.1. Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs’ concepts were predominant in calling attention to the relationship between social capital and urban design through four key areas: her focus on the dynamic and complex nature of cities and neighbourhoods [50,52]; the importance of design to enable informal interactions and “mutual support” [30,37,38,40,42,49,50,61,63]; her activism against sprawl and large infrastructure [37,43]; and the importance of the quality of the public realm, not just its existence [42]. Ref. [42] demonstrated this idea from Jacobs in their results that the “mere provision of community spaces and amenities does not guarantee use”.

3.4.2. Robert Putnam

Robert Putnam was often and mostly referenced in the literature for his work on social capital, in particular the impact of sprawl to the decline of social capital in America [29,40,48]. Although scholars such as Bourdieu and Coleman were also referenced as contributing to the theory of social capital—Coleman referenced in 11 articles and Bourdieu in 7 articles—Putnam was referenced in 22 articles (Table 3). Putnam was identified as a contributor to the theory of social capital for his understanding of community social capital as the resource for mutual trust, connection, and reciprocity, which ultimately promotes “public good” and the civic construction of society [1,26,27,29,30,35,43,49–51,57]. Putnam was further referenced for his influence in popularising the term ‘Social Capital’ [50,54]; his identification, with others, of bonding and bridging social capital [35,40,52]; and his hypothesis that longer commuting times and the design of neighbourhoods are decreasing political participation and cultural integration [29,40,43,48].

3.4.3. New Urbanism

New Urbanism movement emerged as a major movement revealed in this review. New Urbanism was praised for its principles on walkability, mixed use, and densification against urban sprawl [30,33,40,48,49] and specifically how walkable design encourages more social interactions [42,55]. However, [29] and [50] did also present criticisms of the movement, whether in the implemented practices or in the discourse found in other studies.

Neo-traditional urban design was also recognised as an influential neighbourhood design movement, with similar principles to New Urbanism, such as advocating for mixed land use and gridded street patterns [38]. It was, however, referenced to a lesser extent [38,50,56]. Refs. [50,56] recognised the two movements, whereas 10 other studies referenced the New Urbanist movement only [29,33,40,42,48,49,55,59,61,64]. Five articles found there are conflicting results that New Urbanism/neo-traditional neighbourhood design can promote social capital [29,38,40,42,55].

3.4.4. Community Health

Another major movement revealed in the research was the interest in community/public health. Thirty-seven out of forty articles referenced the word ‘health’ in some capacity (Table 3). The reference to health varied in the texts, such as acknowledging rising public health concerns [27,33,34,38,39,45,47,49,51]; supporting community health and wellbeing [41,42,55,57,58,66]; creating healthy cities/neighbourhoods [29,30,32,37,40,48,53]; or reviewing a Health Impact Assessment [54] or health implications from disasters [52].

3.5. Key Themes

Two major themes emerged from this review: first, built environment outcomes and, second, community participation as part of the process of urban design. Each article addressed at least one of these themes, while 25% of articles supported both themes. A breakdown of the themes can be viewed in Table 4. Built environment outcomes in this article are understood as the physical elements of the built environment as an outcome of urban design. Community participation can be defined as the process where “people act in groups to influence the direction and outcome of development programs that will affect them” [68].

Table 4.

Quantitative data collection of themes. (“√” represents inclusion of finding in article).

3.5.1. Built Environment Outcomes

One of the key overall findings uncovered how the relationship between urban design and social capital is linked to how built environment outcomes impact social capital [29,30,33,38,40,43,45,49,53,57]. The four key attributes within this theme incorporated the following:

- The neighbourhood scale;

- A place to gather;

- Building density;

- The quality and maintenance of the built environment.

The following paragraphs present each attribute.

There were 23 studies that discussed how the neighbourhood type impacted community social capital. Five studies highlighted conflicting results on the impact of the built environment on social capital, comparing neo-traditional or New Urbanist neighbourhood design to conventional neighbourhood design [29,33,38,40,49]. Ref. [66] found that walkable and mixed-use neighbourhoods have higher levels of social capital than car-dominated neighbourhoods. The authors of [49] found that the traditional neighbourhood reported closer neighbourhood ties, and respondents believed they were “more involved in mutual aid and community problem solving”. However, they viewed their neighbours as “less supportive” than participants from the ‘sprawl’ neighbourhood. Cul de sacs, on the other hand, which are associated with conventional design, were found to increase trust [40] and were “preferred” by respondents in another study [38]. Ref. [64] identified that cul de sacs increase the probability of carpooling due to one variable of social interactions; however, “the effect loses statistical significance when residential self-selection is accounted for”. In general, Ref. [27] found a “positive relationship between neighbourhood design and identity, collective satisfaction of place, physical health, sense of community and belonging”. Ref. [60] found that the perceived built environment had “positive indirect relationships with the frequency and mode of physical activity, with social capital being the mediating variable”. Further, Ref. [43] found that the neighbourhood design of Alvalade had positive impacts on social cohesion and social capital through the diversity of housing options and access to social spaces and community infrastructure.

Having a place to gather was seen as a significant component of enabling the relationship between urban design and social capital. Ten articles identified a positive relationship between access to green spaces and social capital [29,30,38,39,42,45,48,49,53,54]. Five articles identified other social infrastructure’s value to social capital, such as playgrounds, sporting clubs, and community spaces [29,38,40,42,45,47]. Ref. [52] found that during the post recovery of Hurricane Katrina, the USA, the temporary housing arrangement that contained a central community space fostered greater neighbourhood connection and trust opposed to an alternative arrangement without one. Ref. [63] had similar results, finding that “neighbourhoods with isolating characteristics speak less frequently than neighbourhoods with primarily interactive characteristics”. Another study found that neighbourhood cohesion and community participation were all higher among respondents with dependent children living at home [42]. This study hypothesised the access to social infrastructure, such as green space and playgrounds, encouraged children’s participation and allowed for relationships between parents to build. Streets and sidewalks were also recognised as important in providing a place to gather for both strangers and familiar people, which promoted informal interactions that enabled social capital [29,30,37,38,40,49].

The impact of building density on social capital was identified as having conflicting positive and negative effects [29,33,38,42,48,55,57]. In one study, density was “negatively associated with all three social capital scores, including social cohesion, activities with neighbours, and social participation” [33]. However, Ref. [55] found that the effect of density is mediated by diversity, indicating that if our dense neighbourhoods are also diverse, the negative effects are significantly reduced. Some reasons for the mix of results were hypothesised that it depends on the responder, with some saying it is not good for family’s safety but better for younger adults’ social connections and nightlife activation [57].

The quality and maintenance of the physical environment represented the final recognised subcategory within this key theme. Quality, maintenance, and walkability to destinations both played key roles in community perception and satisfaction of their neighbourhood [36,49,53,54,57,62,65]. Ref. [40] found that social belonging is a major contributing factor in residential decisions. The authors of [30] discovered that the maintenance of the street helped community perception to build pride and civic activity. Another study found that if lots are not maintained, graffiti exists, and greening is not tended to, thus producing a negative impact on safety perception, feelings of hopelessness, stigmatisation, and a sense of isolation [36].

3.5.2. Community Participation Contribution to Social Capital

The second prominent theme emerging from the review was a focus on community participation as a process of urban design. Out of 40 articles, 16 discussed elements of community participation and how it could build social capital. According to the reviewed literature, community participation may improve social capital through involvement in urban design projects [26,30,34,35,44,46,51,52,59,61,67]. For example, through the process of digital mapping local narratives of place, community participation identified areas where both the social and physical environment impacted individual community members differently [46]. Ref. [51] found that community participation in urban design can “enrich social networks with direct benefits for social capital and wellbeing”. Ref. [35] revealed that involving technology allows for a greater breadth of participants, who may have varying ability to contribute, which resulted in greater satisfaction of the project, increased social participation, and increased trust in government.

Collaboration between designer/planner and community was also recognised as a key tool for building community social capital [26,30,41,52]. Refs. [30,52] both propose that a collaborative approach to community participation is necessary when responding to vulnerable communities. They suggest that working with the community not only provides an understanding of the spatial requirements but also of the social and cultural requirements, thus informing better outcomes and quicker rebuilding.

3.6. Results on the Relationship between Urban Design and Social Capital

Urban design and social capital can be seen as two individual entities. However, the literature clearly confirms overlaps between the two. From the review, it was identified that 68% of articles looked at the impact of urban design on social capital, almost 20% of articles discussed the influence of social capital on urban design, and 12% focused on how both can influence each other (see Table 5). For example, articles that were urban design driven involved urban design interventions to an informal settlement [30], measuring walkable built environments on social capital [33], analysing the impacts of vacant lots on the perception of safety and social capital [36] and a connection to green space, resulting in positive social capital [38,39]. The articles with social capital as the main driver were concerned about the study of children influencing the social capital of a neighbourhood [42]; new models of engagement [44,46]; how social capital enhances resilient urban design theory [41]; the importance of social capital for the new regionalism theory to progress [56]; and a review of Jane Jacob’s work on the importance of social capital and self-governance on the development of urban environments [37]. Articles that recognised the influence of both on each other looked specifically at the co-benefits of both urban design and social capital on community health [58]; how a neighbourhood level impacts community participation [59]; how the integration of social capital research within a built environment field can extend social capital research [61]; how people’s perception of space is influenced by both the physical environmental and social awareness [65]; and how recognising the value of involving stakeholders in the design process can have a dual impact on the urban design and social capital outcome [67].

Table 5.

Main themes and their topic of interest.

There were 11 articles that referenced the need for bottom-up interventions and/or integrating community into the design process as a means of contributing to enhanced social capital outcomes [27,30,34,35,38,44,46,50–52]. For example, [52] discussed that if the community is involved from the beginning of a built form intervention, preexisting social capital can inform design response for quicker recovery. Further, Ref. [51] discussed the benefits of community involvement in the whole of the urban design project. Seven articles also recognised that community social capital can contribute to the urban design and planning field [26,30,34,36,43,52,56].

4. Discussion

The results showed that authors’ geographical locations played a dominant role in shaping the current literature, as articles tended to use the same references repeatedly. This finding aligns with other literature reviews focusing on urban studies, where the majority of authors came out of North America and Europe, particularly from the USA [25]. Therefore, one notable gap evidenced in this review is the underrepresentation of multicultural perspectives that would provide a better and more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between urban design and social capital. This aspect was underlined by two studies, [39,45], that emphasised the need to explore diverse cultural landscapes, such as Asian neighbourhoods, to understand variance in the impact of urban design on communities.

Furthermore, the overwhelming reference to some specific key contributors, such as Jane Jacobs, does raise questions. Indeed, it clearly evidences the lack of contemporary references. For example, although urban designer Jan Gehl could have been expected to find his place in this review due to his work about the importance of designing for the pedestrian and strengthening the social function of the city “as a meeting place that contributes toward the aims of social sustainability and an open and democratic society” [69] (p. 6),he only appeared once in the reviewed articles [50]. In the same way, Indian architect and urban planner Charles Correa was not referenced despite being famous for designing neighbourhoods that fostered a sense of belonging and social interaction through strategic design of semi-public and public spaces [70]. This lack of contemporary representativeness actually questions whether scholars are obsolete in their training and/or whether there is a reluctance to connect contemporary practitioners’ research with the literature, as their work is often less validated than historically referenced figures like Jane Jacobs. For instance, case studies such as the Alvalade neighbourhood in Lisbon, which embodies principles similar to those of New Urbanism and predates it, were discussed only in one article [43]. To improve the relationship between practice and scholarship, it would seem crucial to consider relevant contemporary references so that practice can evolve and learn from academic insights.

Another key finding in this literature review was the complex nature of defining the terms social capital and urban design. With no clear definitions, the relationship is subject to interpretation by sectors committed to either field. An interesting finding was the disparity between the number of articles that defined social capital significantly more than urban design. This showcased the confusion and ambiguity around this relationship. This could be due to an assumed understanding of what urban design is or the assumed background of the reader to be aware of the term. However, as the key themes identified, we found that articles largely focused on either built environment outcomes or the process of community participation rather than urban design specifically. Despite few articulating that urban design can be viewed as a holistic discipline incorporating both the process and outcome of the built environment, emphasising the two-sided nature of the term ‘urban’ and ‘design’ as “the former referring to the product and the latter to the process”, the ambiguity around the discipline is still exposed with our review. An argument could be that it is more important to know what the relationship between urban design and social capital does and its value, not its definition. A recommendation could be to develop future research on a guiding framework for understanding the variables of social capital and urban design. It could focus more on the relationship between the two variables and when and where an intervention is required, not specifically on the definitions themselves. This could help to view both areas as fluid and evolving and allow for flexibility over time and places.

The two themes, built environment outcomes and the process of community participation, revealed consistent topics influencing the discussion. The varying results of both the positive and negative impacts of the components of urban design on social capital, such as neighbourhood scale and building density, demonstrated that research and agreement on this topic is still evolving.

The theme of community participation shows a significant positive relationship between urban design and social capital. These findings highlight opportunities for community involvement at the intersection of this relationship. Urban designers, equipped with tools and training in design thinking, can address problems through curiosity and innovation. One recommendation would be to provide more guidance on community participation, avoiding the ‘top-down’ method. Another is to practice community involvement that focuses on shaping and valuing social capital and community building. These approaches could shift the role of urban designers from being ‘experts’ to ‘facilitators,’ working with the community to determine their needs and the appropriate built responses. Ultimately, this approach could use design as a tool to help people develop their own communities.

Several articles discussed the value of community social capital in urban design processes and outcomes. One recommendation is to integrate the community earlier in the decision-making process to understand existing social ties and how they could influence the design [52]. As [71] identifies, the current predominant urban design model is a high-level, top-down approach that has limitations in involving community stakeholders, resulting in designs that do not fully address community needs. Similar to [21] (p. 49), Ref. [67] recommends that to achieve social sustainability in neighbourhoods, it is essential to address both physical and non-physical elements (such as social capital and social equity). Recognising the community as a diverse mix of needs and networks can promote a holistic urban design process informed by social capital. Integrating community participation, and valuing community social capital in the process, is evidently a crucial anchor in the relationship between urban design and social capital.

The literature shows that urban design has evolved to become more agile and responsive to community health needs and adverse environmental effects. Acupuncture urbanism and tactical urbanism are examples in practice of agile urban design, although these were not discussed in the reviewed literature. Bottom-up urban design interventions or the need for integrating community were still referenced as important to the development of this relationship, discussed in 11 articles. The reactive and agile strengths in social capital could be valuable for urban design to adapt to rising demands imposed on the profession.

What was apparent in undertaking this study was the difficulty around conceptualising what this relationship looks like due to the complexity of both terms themselves as well as the complexity of defining this relationship itself. In many languages, there are words that cover an experience or phenomenon, such as weltanschauung in German, meaning someone’s world view [72], or raison d’être in French, meaning a person’s reason for living [73]. As there is no word or phrase that defines the intersection of urban design and social capital and the relationship between them, research on this topic is difficult to navigate. Hence, the value of this study was to focus on breaking down the definitions and methods used, key figures, movements, and themes surrounding this topic. It was identified as contributing to dialogue on this complex and evolving relationship.

5. Conclusions

Using a literature review process following the [23] guidelines for an SQLR, the research explored the relationship between urban design and social capital. There is building interest in this topic, which could be a response to the rising public health concerns and an awareness of the impacts of the built environment. The review revealed that the relationship is complex and not well defined. It emphasised a consistency across the literature of references to the key historical figures Jane Jacobs and Robert Putnam and the New Urbanism movement. Two major themes—the built environment outcomes and community participation—emerged as key topics of interest in the reviewed literature.

The research also highlighted that the relationship between urban design and social capital is underexplored, with a lack of contemporary relevant references contributing to this topic. This deficiency results in a body of academic literature that does not fully address or reflect current industry practices and innovations. This gap between academia and practice hinders industry progress, as practice relies on academic advancements. To fully realise the potential of the industry, updated references are crucial. Additionally, there is a need to shift focus globally, incorporating multicultural references and case studies to learn from diverse contexts. This global perspective is essential for addressing local issues impacted by climate change, social inequality, and rapid urbanisation, thereby informing urban designers on how to better integrate community needs into their designs. Urban designers, as experts, are in a key position to collaborate with communities, enabling them to access this knowledge, be empowered, and build their own social capital within their neighbourhoods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.C., K.D., and R.F.; methodology, M.C., K.D., and R.F.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; data curation, M.C., K.D., and R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C., K.D., and R.F.; visualisation, M.C.; supervision, K.D. and R.F.; project administration, M.C., K.D., and R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The presented data in this article are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, D.; Van Deth, J.W.; Wolleb, G. The Handbook of Social Capital; Oxford University Press: New York, NY USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D.P. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Häuberer, J. Social Capital Theory: Towards a Methodological Foundation; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D.P. The importance of social capital in building community resilience. In Rethinking Resilience, Adaptation and Transformation in a Time of Change; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Postelnicu, L.; Hermes, N. The economic value of social capital. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2018, 45, 870–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Social Capital and Civil Society. IMF Work. Pap. 2000, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social capital and community resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, M.A.; Coghlan, A.; Dupré, K.; Vada, S.; Gardiner, S.; Smart, J.C.; Castley, G. Disaster recovery as disorientation and reorientation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 49, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R.; Lass, I. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 21, the 18th Annual Statistical Report of the HILDA Survey; Melbourne Institute, Applied Economic & Social Research The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, J. Mapping Social Cohesion 2023; Scanlon Foundation Research Institute, Monash University, Australian Multicultural Foundation, Australian National University: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Beck, H.E.; Boergens, E.; de Jeu, R.A.M.; Dorigo, W.A.; Frederikse, T.; Güntner, A.; Haas, J.; Hou, J.; Preimesberger, W.; et al. Global Water Monitor 2023, Summary Report; Global Water Monitor: Acton, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, L.A.; Gill, D.A. The role of social capital in community disaster resilience. In The Disaster Resiliency Challenge: Transforming Theory to Action; Bohland, J., Harrald, J., Brosnan, D., Eds.; Charles C Thomas Publisher: Springfield, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 112–139. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sanoff, H. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Ambiguities of urban design. Town Plan. Rev. 1997, 68, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, S.G.; Sellars, D.; Dupré, K.; Mews, G.H. Implementation of the New Urban Agenda on a local level: An effective community engagement methodology for human-centred urban design. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2024, 17, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omole, F.O.; Olajiga, O.K.; Olatunde, T.M. Sustainable urban design: A review of eco-friendly building practices and community impact. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.; Lally, M.; Septiana, H.; Taylor, D.; Thorne, R.; Cameron, A. Urban design compendium. Reino Unido: Engl. Partnersh. 2007, 2, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General. Global Sustainable Development Report 2023: Times of Crisis, Times of Change: Science for Accelerating Transformations to Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Grignon, J.; Steven, R.; Guitart, D.; Byrne, J. Publishing not perishing: How research students transition from novice to knowledgeable using systematic quantitative literature reviews. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Johnson, M.; Byrne, J. Using systematic quantitative literature reviews for Urban analysis. In Methods in Urban Analysis; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, M.; Blair, N.; Davison, K. Articulating a social-ecological resilience agenda for urban design. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusban, S.A.; Alhusban, A.A.; AlBetawi, Y.N. Suggesting theoretical urban neighborhood design concept by adopting the changing discourse of social capital. J. Enterprising Communities: People Places Glob. Econ. 2019, 13, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumdar, S.; Learnihan, V.; Cochrane, T.; Davey, R. The built environment and social capital: A systematic review. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 119–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, K.; Cartes, I. Urban design and social capital in slums. Case study: Moravia’s neighborhood, Medellin, 2004–2014. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.E.; Hornburg, S.P. What is social capital and why is it important to public policy? Hous. Policy Debate 1998, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Residential and transit decisions: Insights from focus groups of neighborhoods around transit stations. Transport Policy 2018, 63, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Nakaya, T.; McCormack, G.R.; Shibata, A.; Ishii, K.; Yasunaga, A.; Hanibuchi, T.; Oka, K. Traditional and novel walkable built environment metrics and social capital. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, C.; Voghera, A. Resilience in action: The bottom up! architecture festival in Turin (Italy). J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2023, 4, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, D.; Young, D. Community in the information age: Exploring the social potential of web-based technologies in landscape architecture and community design. Front. Archit. Res. 2016, 5, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I.; Raskin, J. Urban vacancy and land use legacies: A frontier for urban ecological research, design, and planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, P.L. Jane Jacobs’s urban ethics. Cities 2019, 91, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.E. The relationship of urban design to human health and condition. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 64, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugel, E.J.; Carpiano, R.M.; Henderson, S.B.; Brauer, M. Exposure to natural space, sense of community belonging, and adverse mental health outcomes across an urban region. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.G. Can community design build trust? A comparative study of design factors in Boise, Idaho neighborhoods. Cities 2010, 27, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Hasankhan, F.; Garakani, S.A. Principles in practice: Toward a conceptual framework for resilient urban design. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 2194–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B.; Zubrick, S.R.; Bulsara, M.K. “Through the Kids... We Connected With Our Community” Children as Catalysts of Social Capital. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 344–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerez, R. Creating neighbourhood networks: Why the alvalade landscape matters to housing. Open House Int. 2015, 40, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, H.; Brown, D.; Kindon, S. Solidarity through difference: Speculative participatory serious urban gaming (SPS-UG). Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2020, 18, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Roberts, A.C.; Chao, S.T.-Y.; Ng, E. Designing urban green spaces for older adults in Asian cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, M. Duty of care: Foregrounding the user in design practice. Open House Int. 2008, 33, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.L.; March, S.; Brownlow, C.; Biddle, S.J.; Ireland, M. Inactive lifestyles in peri-urban Australia: A qualitative examination of social and physical environmental determinants. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, D.J.; Williamson, T. Inactive by design? Neighborhood design and political participation. Political Behav. 2012, 34, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oidjarv, H. The tale of two communities: Residents’ perceptions of the built environment and neighborhood social capital. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018768386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, D. Reconstituting the urban commons: Public space, social capital and the project of urbanism. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; March, T.L. An urban community-based intervention to advance social interactions. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spokane, A.R.; Mori, Y.; Martinez, F. Housing arrays following disasters: Social vulnerability considerations in designing transitional communities. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 887–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A.; Maghelal, P.; Alawadi, K. Assessing neighborhood satisfaction and social capital in a multi-cultural setting of an Abu Dhabi neighborhood. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagon, J.; Jabot, F. The challenge of assessing social cohesion in health impact assessment. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonta, A.; Jiang, X. Rethinking walkability: Exploring the relationship between urban form and neighborhood social cohesion. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.M. The new regionalism: Key characteristics of an emerging movement. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2002, 68, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Shannon, T.; Bulsara, M.; Pikora, T.; McCormack, G.; Giles-Corti, B. The anatomy of the safe and social suburb: An exploratory study of the built environment, social capital and residents’ perceptions of safety. Health Place 2008, 14, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.J.; Berry, P. Health co-benefits and risks of public health adaptation strategies to climate change: A review of current literature. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y. Toward community engagement: Can the built environment help? Grassroots participation and communal space in Chinese urban communities. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mepparambath, R.M.; Le, D.T.T.; Oon, J.; Song, J.; Huynh, H.N. Influence of the built environment on social capital and physical activity in Singapore: A structural equation modelling analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B. Is there a place for social capital in the psychology of health and place? J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Liu, J.; Yin, C.; Cao, J. Residential and workplace neighborhood environments and life satisfaction: Exploring chain-mediation effects of activity and place satisfaction. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 104, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeVan, C. Neighborhoods that matter: How place and people affect political participation. Am. Politics Res. 2020, 48, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheed, D.S. The relationship between neighborhood design and social capital as measured by carpooling. J. Reg. Sci. 2019, 59, 962–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.; Lakerveld, J.; Stronks, K.; Kunst, A.E. Uncovering how urban regeneration programs may stimulate leisure-time walking among adults in deprived areas: A realist review. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyden, K.M. Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somanath, S.; Hollberg, A.; Thuvander, L. Towards digitalisation of socially sustainable neighbourhood design. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 770–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S. Community participation in World Bank projects. Financ. Dev. 1987, 24, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R. Neighborhood spaces in residential environments: Lessons for contemporary Indian context. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Curwell, S.; Bichard, E. The current approach of urban design, its implications for sustainable urban development. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Assessment, C.U.P. Weltanschauung. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/german-english/weltanschauung (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Assessment, C.U.P. Raison-d-etre. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/raison-d-etre (accessed on 10 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).