Abstract

This exploratory paper aims to discuss how community is fostered in semi-public restrooms on a college campus. While previous research has been undertaken in similar semi-private environments, this paper differs by simultaneously offering the researchers’ reflective insights in tandem with participants’ input on the research question. We begin by unpacking the challenges around Participatory Design (PD) activities that are undertaken in sensitive and private interior environments. Gathering perceptions of these sensitive spaces required methods that allowed for both anonymity and a communal approach through the use of provocative and evocative probes such as comment boxes and graffiti wall posters. This paper not only catalogues the findings of this research but also documents the difficulties in utilizing a participant-led approach, gaining access to sites and participants, and countering our own biases throughout the study’s construction. Through researcher accounts and participatory data analysis, the researchers offer a focused reflection on a possible new frontier for advancing PD methods in sensitive environments through playful probes. The contribution of this paper offers six lessons on the efficacy of using probes in semi-private environments, with playfulness as a primary driver of engaging participants.

1. Introduction

To understand behaviors and perceptions around intimate spaces, research must be approached creatively to effectively engage users while ensuring that their responses can be kept private and authentic. Engaging participants is particularly difficult to do in areas such as restrooms, which support social encounters within a typically private space. Still, many of us might recount times in which we might engage with strangers and friends in restrooms, creating a sort of community that is difficult to replicate in other environments.

Community is often expressed in the simple gesture of holding the door open or complimenting someone on their choice of shoes. Drawing from examples in the literature, at other times a sense of community has more profound and impactful consequences, such as the case explored by Drew Forbes’s reviews of the public restrooms in O’Hare International Airport in Chicago, Illinois, USA. There, restroom spaces were utilized as strategic spaces to organize protests, where those participating “wanted to exploit a vulnerability in the interface between biophysical processes and infrastructure” [1]. The demonstration of these underserved populations illustrates the idea that semi-public spaces engender a feeling of significance for ensuring that such environments are open to all. While the necessity of restrooms is primarily tied to the support of natural human processes, their social significance and connotations with refuge, safety, and security come into play [1].

Similarly, a gendered investigation of a shared female public restroom reveals the development of community between diverse women who had access to the space. This study demonstrates an emergence of a “distinctive women’s approach and relationship to objects, space, and one another” through the creation of a shared space within the restroom through objects and additions each of the women made [2]. There is evidence of restroom “culture” through these donated items shared with other female users, including female-themed reading materials with encouraging titles, stuffed animals, holiday decorations, and a guest book. Writings ranged from names of visitors to compliments of the restroom’s environment. In this way, the guestbook fostered a sense of community through “playfulness and inclusive good humor” in a shared, private space [2]. While these environments may not be typically thought of as places that foster community, playfulness acts as a method for encouraging camaraderie and openness to social interactions.

As advocated and promoted by the approaches of Gaver et al. [3] and Crabtree, et al. [4], design should encourage participants to “explore, wonder, love, worship, and waste time together and in other ways engage in activities that are ‘meaningful and valuable’ to them” [3]. In fact, Gaver references this approach in his earlier work on cultural probes. The concept of playfulness should not be perceived as overtly entertaining, but rather, playful in a subtle way [3].

Instagram provides an opportunity for users to engage in these playful activities, leading to additional insights into the thoughts of semi-public restroom users. One particularly active Instagram account, @osubathrooms, has been reviewing the campus restrooms of the Oregon State University campus since 2019 (@osubathrooms, 2019). The online shareable content is humorous and engaging. Each photo is tagged with a caption that lists a location, identifies the restroom as a male or female toilet, provides a brief description or evaluation, and then gives a rating out of five. This account and others serve as public inter-community notice boards to alert others of restroom expectations when planning to partake in that ever-so-human need. The following are a few examples of these photos and their associated captions that exhibit playfulness when discussing and rating (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Instagram account @osubathrooms examples.

Through these examples, ‘playfulness’ becomes fundamental to our understanding of semi-public restrooms and central to our research investigation of restroom communities. Aspects of comfort, privacy, function, and design are exemplified in the anecdotes provided which accompany the images. While largely in jest, these accounts further demonstrate the layers of meaning and significance restrooms have in serving as a mirror for our societies, whether it is in their ability to provide respite, give enough seclusion, serve their purpose, or be aesthetically pleasing. This central focus necessitated a light-hearted engagement with our participants in all of our research activities and recruitment practices. When collecting participants’ responses, we were sure not to act as deterrents to the fostering of playful attitudes that inherently blossom around the topic of semi-public restrooms.

We decided on the question to pose for participants to answer: “How is community fostered in (large US university) restrooms?” This question holds a clear presupposition that restrooms do indeed foster community. We anticipated that with this chosen phrasing we could prompt strong reactions from those who disagreed with our premise and deep reflection from those who agreed. An appropriate probe question should communicate the definition of space in relation to the campus community since semi-public restrooms represent a “bubble universe” running parallel to the reality of the university campus at large [2].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Positioning

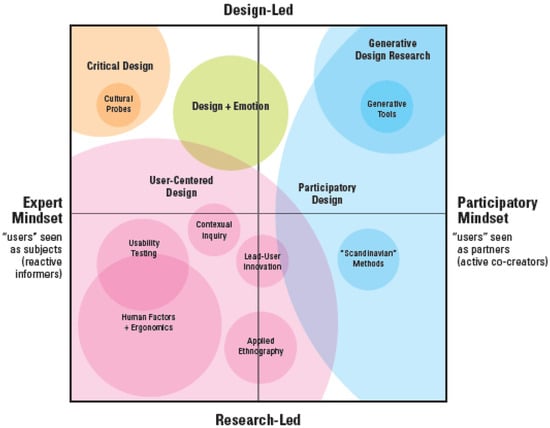

This study applies a participatory mindset to ensure that the ideas of restroom users were effectively gathered and represented through relevant methods, tools, and analysis. Sanders and Stappers outline the positioning of this approach in the design research landscape presented in Convivial Toolbox [10]. Furthermore, illustrated in Figure 1, this approach aims to inform studies by viewing participants as “partners” and “active co-creators”. Concerning this positioning, Sanders and Stappers say that “design researchers [with a participatory mindset] work with people. They see people as the true experts in domains of experience such as living, learning, working, etc. Design researchers who have a participatory mindset value people as co-creators in the design process and are happy to include people in the design process to the point of sharing control with them” [10]. Taking a step back as researchers, participant input was continuously integrated in the stages of methodological development, data collections, and assessment periods to ensure that the researchers’ views did not usurp that of the users.

Figure 1.

Research positionality outlining participatory mindset approach with research-led methodology.

2.2. Methodology

In our study, probes serve as a prompt [11] and are “purposefully designed to provoke, reveal and capture the motivational forces that shape an individual” and “to capture people’s reflection about some part of their life” [12]. Due to the “socially sensitive [setting]” of semi-public restrooms, probes were seen as the best fit for our activities to follow in the example of Hemmings, Crabtree, and Rodden, et al. [4]. Simultaneously, anonymity was also a concern because “privacy is essential in the dimension of public identity and self-presentation” [13]; it would be essential to preserve anonymity if we were to entice any of the restroom visitors to share their responses to the probe. As noted by others working in participatory environments, “pragmatically, working … with sensitive topics brings additional research challenges and additional resource requirements … considerable time and effort may be required in recruitment” [14]. While the development of these methods and their deployment required a bit more nuance and thought to ensure participation with the promise of anonymity, a third element also played an important role in bringing these traits together: playfulness. This was clearly manifested in our recruitment efforts, as seen in the distributed flyer displayed in Figure 2. Moreover, several lessons can be drawn from Paasovaara, Lucero, and Olsson’s work regarding playful design experiences between strangers; in the project, the authors recount the importance of anonymity in its ability to promote playfulness, including enticing mystery, focusing on the topic rather than individuals, and the elimination of prejudgment of contribution based on personal appearance and social standing [15].

Figure 2.

Part of the focus group flyer posted in H. Hall.

2.3. Sites of Data Collection

The location of our probes included semi-public restrooms in two buildings, H. Hall and P. Hall, on the campus of a large U.S. university.

2.4. H. Hall Community: Academic Building

H. Hall is a centrally located, historic academic building on the university’s campus which houses a department within the creative disciplines, as well as some classes outside the department. Its restrooms are small (usually 2–3 toilet stalls and 2 sinks on each floor) and outdated. To note, the H. Hall building does not have a gender-neutral restroom nor a family restroom, and thus these spaces were not included in the study. Its restrooms see a relatively high volume of use throughout the day when classes occur but also into the evening when students continue to work in the studio spaces and use the facilities. With our familiarity of this site and the building management, H. Hall seemed to be a reasonable location for employing the first measures of our study.

2.5. P. Hall Community: Residence Hall

Following the gathering of responses at H. Hall and their analysis, the study pivoted to examine an environment unfamiliar to us as researchers: an undergraduate residence hall (hereby referred to as P. Hall). The purpose of this next step in the investigation of exploring community in semi-public restrooms was to examine another location in a similar communal, anonymous manner to compare with that of H. Hall. However, given the difference in use (academic vs. residence), researcher familiarity, and an additional type of probe, the information gathered from P. Hall adds a supplemental layer of understanding about community in restrooms.

2.6. Methods and Materials

Governed by the need for a simple and anonymous method [12], we decided that written comments were best for obtaining responses. We settled on the use of: (1) survey/comment submission boxes and (2) graffiti wall posters.

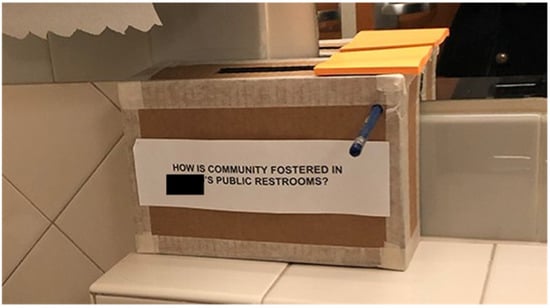

2.7. Survey/Comment Submission Boxes

We equipped each restroom in our study with a closed cardboard box with a slot and labeled the prompt “How is community fostered in (large US university) public restrooms?” Each box was also supplied with a writing utensil and sticky notes for participants to record their response. These boxes were placed in semi-public restrooms on the large university campus in March 2019, which included H. Hall and P. Hall. In both buildings, submission boxes, seen in Figure 3, were left in a men and women’s restroom on two separate floors. Boxes in H. Hall remained in restrooms for over a week’s length, while boxes in P. Hall were removed from the semi-public restrooms within a few days.

Figure 3.

Comment box in residence hall.

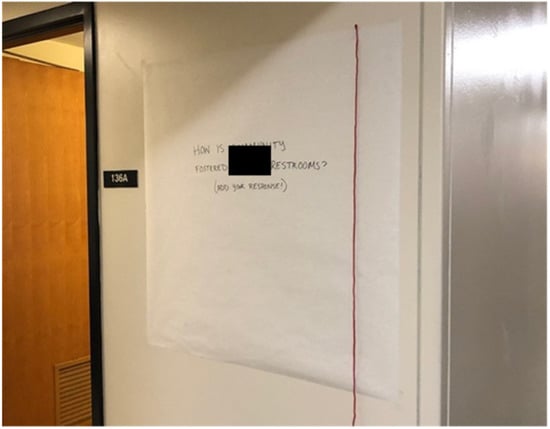

2.8. Graffiti Walls

The second method was a graffiti wall that prompted responses to the same question as the boxes: “How is community fostered in (large US university) public restrooms?” Four graffiti-wall posters were hung outside semi-public restrooms in (P. Hall). Writing utensils were provided with the graffiti-wall posters for the participants’ responses.

Graffiti walls were employed, as Martin and Hanington define, to “provide an open canvas on which participants can freely offer their written or visual comments about an environment or system, directly in the context of use” [12]. Graffiti walls also echo the prevalence of latrinalia, or restroom graffiti, sightings. Similar to the comment boxes, writing offered participants the same opportunity to interact and express their opinions in a research-sanctioned mode [16]. This varies from the comment box format in that graffiti walls are more communal and collaborative while also being less anonymous as they remained on display for restroom visitors to read. These graffiti walls encouraged an interaction of comments that could build on each other and respond to each other (Figure 4). Using this approach, we hoped to “… empower a multiplicity of voices…” that maintained anonymity while still enabling the engagement of a collective group [17].

Figure 4.

Graffiti wall in residence hall.

3. Results

3.1. H. Hall Comment Boxes

Comment boxes were positioned above the paper towel dispensers for ease of access and maximum visibility for approximately one week. Responses were collected from the boxes on two different days during this time and recorded for analysis. What we discovered was an array of dissenting views on community in semi-public restrooms. These included critiques of restroom environments, outright denouncements of community, interrogation of the posed research question, and lewd remarks. While negative and abrasive comments were reflected by the equally abrasive corporeal connotations of the restrooms, they were likely further enabled by the anonymous format and tinged by our biases as women and frequent users of the space. While these views of semi-public restrooms differed from that of our expectations, they nonetheless represented the participants’ own multi-faceted lenses on the concept of restroom communities. Sixty total responses were collected from the H. Hall comment boxes and were logged before an initial cursory categorization into seven themes, ordered by number of comments:

- “Social Behaviors/Norms”—responses regarding typical social interactions between restroom users. Of the nine responses in this theme, three responses included:

- ◦

- “A place to gossip & complain, a place to hide & talk with friends”;

- ◦

- “We learn who has what shoes”;

- ◦

- “By washing your damn hands”.

- “Not Community”—responses directly denouncing the idea of community in public restrooms. Of the fifteen responses in this theme, three responses included:

- ◦

- “I prefer that community not be fostered in the restrooms”;

- ◦

- “Why would I want community in my bathroom? I like my bathroom experience to be private not public. I’m there to do one thing LOL :)”;

- ◦

- “It’s not! No one in a male bathroom wants to talk to each other”.

- “Explicit Content”—lewd, suggestive, or inappropriate remarks concerning restroom use and/or sexual content. Of the fifteen responses in this theme, three responses included:

- ◦

- “We all shit and piss maybe cum”;

- ◦

- “Penis measuring contests”;

- ◦

- “Fuck you for asking this question the bathroom is where you piss and shit you liberal cunts need to fuck off and let it be! P.S. I stole your pencil”.

- “Environmental Qualities/Comments”—responses relating to the physical conditions of the restroom (mostly complaints). Of the nine responses in this theme, three responses included:

- ◦

- “We have fun chatting about the one random stall in the basement women’s restroom that has a curtain instead of a door. Always a conversation starter”;

- ◦

- “Peein [sic] in 1960s era urinals fosters my (school) spirit”;

- ◦

- “Sharing sounds & smells ___ illicit scratching”.

- “Other”—responses unrelated to the question posed. Of the five responses in this theme, three responses included the following:

- ◦

- “I like turtles”;

- ◦

- “Pick a different project bro… lol”;

- ◦

- “;)”.

- “Community Suggestions”—responses suggesting improvements to the restroom or proposing a call to action. Of the seventeen responses, some responses included:

- ◦

- “I like your outfit”;

- ◦

- “Can they put tampons in here instead of pads?”;

- ◦

- “Need gender neutral bathrooms”.

After cataloguing these responses, we considered our positionality as an all-female team with gendered understanding of restroom spaces, as well as familiarity of the particular restrooms in question. Because of this, we decided to undertake a focus group to participate in creating categories for the received comment-box responses to remove the possible bias.

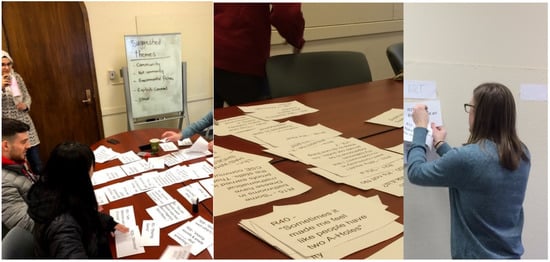

3.2. H. Hall Focus Group

We invited students at H. Hall to participate in a focus group. A primary goal of the focus group served to reify the participatory approach of this study by placing data analysis in the hands of participants. Flyers, as seen in Figure 1, were distributed around H. Hall. Unfortunately, the open recruitment through flyers was not received well among H. Hall’s visitors, and the focus group did not get much interest at first. This was possibly due to our timing coinciding with midterm examinations. Due to the low interest in the study, we recruited additional participants from classrooms directly within H. Hall. In this personal-invitation approach, more individuals agreed to participate in the focus group activities. The focus group participants included four college students (two male and two female) as both representatives of each restroom gender and the campus population that frequently used restrooms within H. Hall.

3.3. Focus Group Methods

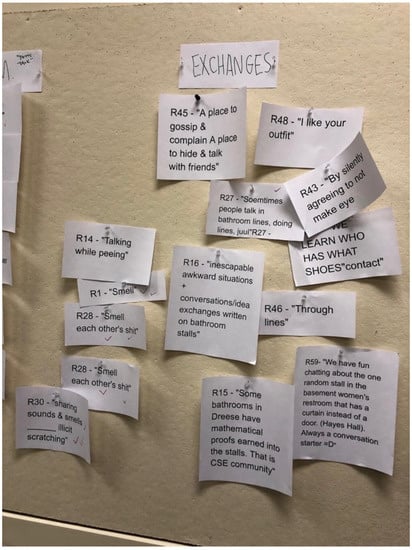

The responses collected from the submission boxes were printed onto cards for review, evaluation, sorting, and categorization of each response into themes determined by the focus group. The development of categories and the card sorting method (demonstrated in Figure 5) served to “identify items that may be difficult to categorize”, while mirroring the sorting process we engaged in, thus enabling participants to either validate or invalidate our responses [12].

Figure 5.

Focus group category card sorting example.

The focus group participants determined seven thematic categories:

- “Improvements” (comments on improvement opportunities to the physical surroundings);

- “No Homo” (discomfort due to physical proximity);

- “BM” (bowel movement and associated smells/actions);

- “Exchanges” (interactions or indicated interactions between restroom users);

- “Germs” (comments regarding cleanliness or hygiene);

- “Rando” (non-titled group that bridged BM and Exchanges).

3.4. Focus Group Data Analysis

While the themes categorized by the focus group participants varied in titles from our own categories, they were nonetheless similar in content. As can be seen in (Table 2), the two sets of categories are paralleled, with the exception of our identified “Not Community” category which was absorbed into the focus groups’ “Rando” category.

Table 2.

Emergent parallel themes from the H. Hall restrooms, as designated by the researchers and the participants of the focus group.

While sorting responses, the focus group participants discussed the comments and their own ideas about semi-public restrooms (Figure 6). During the session, Participant 2 (female) offered that “you’re kind of thinking about community when you’re washing your hands”, commenting on a response in the “germs” category. Participant 3 (male) related to a response on recognizing shoes worn by a person in a stall, saying “there’s a community in knowing the people you’ll see in the restroom sometimes”. Participant 4 (male) agreed with a comment in the “no homo” category, clarifying that “guys are so uncomfortable with each other in the restroom”.

Figure 6.

Focus group discussion.

Gathering these more diverse perspectives on the comment box responses successfully reinforced the study’s participant-focused approach while testing our biases. Moreover, the focus group participants’ perceptions of the comment box responses closely matched our own. Still, providing participants with this authority allowed for crucial additional input to verify our hunches and provide narrative accounts of participant interpretation.

3.5. P. Hall Comment Boxes

The same comment boxes used in H. Hall were deployed in the communal restrooms of P. Hall. Two collection boxes were placed in the residence hall’s female restrooms and two in male restrooms. The boxes were also spaced out geographically, with one female and male toilet being on the ground floor and another pair being on the third floor. The gender separation in residence hall restrooms was less strict than in H. Hall in that it was not enforced by labels, but rather enforced by corridor location, with half of each floor reserved for each gender. The restrooms were all single occupancy with a toilet, shower, sink, and mirror. The comment boxes were placed near the wash basins for maximum visibility and to remain far from the moist surroundings.

We expected the comment boxes placed in P. Hall to elicit many more responses than had been received in H. Hall; we hypothesized this after realizing the secluded nature of the restroom situation in the residence hall that allowed far more privacy to respond to the prompt. After two days, we only collected 11 responses and completed a thematic analysis. Six responses were placed into the “Social Behavior/Norms” category. Two responses were placed in the “Environmental Qualities/Comments” while “Not Community”, “Explicit Content”, and “Other” categories received one response each. Similar to H. Hall’s comment boxes responses, more were collected from the male restrooms than the females’.

3.6. Power Balances in P. Hall Bathrooms

The deployment of comment boxes in P. Hall was met with bureaucratic resistance. The overnight custodial staff was directed to dispose of any items within the restrooms, and our comment boxes met a similar fate. This was unexpected, since we had taken all the necessary steps with the residence administration to allow for our data collection activities.

Working within the bureaucratic contexts of a (REDACTED) university, it was somewhat difficult to find proper approval for our study, and we were unable to communicate our goals clearly to the building staff. Still, there is something to be learned from this unfortunate turn of events; semi-public spaces are regulated by an entity which has set procedures that are difficult to revise, even when one part of the system approves these amendments. Additionally, the residence hall regulating entity has a power that far outstrips the comparative power of the students who reside in P. Hall. The custodial staff was operating under a definition of what constituted a natural part of the restroom ecosystem; our comments boxes were not included, and were, therefore, discarded. Although the question of power in semi-public restrooms is not the central focus of this paper, a burdensome question arises requiring investigation regarding the definition of a restroom ecosystem. Was the discarding of the comment boxes a move that valued privacy and access? Or were there other motivations? What are the consequences of an overreaching authority in regulating semi-private/semi-public spaces that can be the locus for internal communities to challenge power structures?

In this study, it is unlikely that students would have objected to the unobtrusive presence of the boxes; however, the regulating power unilaterally decided they were intrusive and removed them. In fact, the students’ welcoming attitude to the prompt for responses was proven in their reaction to our graffiti walls, the next probe utilized in P. Hall. This was seen as a more allowable engagement within P. Hall and where participant engagement with our prompt and questions of “fostering community” was best understood.

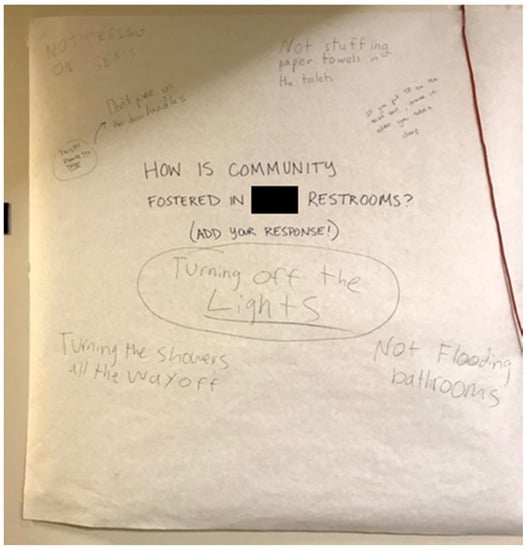

3.7. P. Hall Graffiti Walls

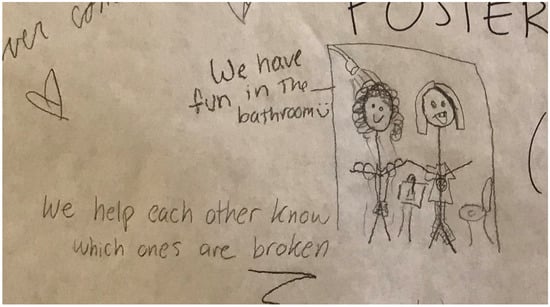

The use of the graffiti wall posters in P. Hall proved to be tactile and reciprocal. With the graffiti wall posters being hung up in a residential space, we hypothesized that students would have frequent access to them as they went about their daily routines. It is likely that they would know who else had commented as members of the shared residence hall community; while this type of community operates separately from the sphere of the restroom, it is nonetheless an extension of it. Using this approach, we hoped to “empower a multiplicity of voices” that maintained anonymity while still enabling the engagement of a collective group [17]. The graffiti walls thus encouraged an interaction of comments that could build on and respond to each other, as can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Graffiti wall posters in P. Hall.

The graffiti walls elicited thirty-four legible handwritten comments from the residents that we categorized into seven themes after analysis. Two comments were not legible and therefore removed. The engagement on the graffiti walls was in itself a visual and tactile manifestation of “public conversations”; this set it apart from the individual responses collected in the comment boxes. Hence, the responses on the walls are contextual and reference each other, therefore, they must be understood as a collage of comments. The analysis below tries to tease out the different “public conversations” that occur and define the rationale for their thematic categorization ordered by number of comments:

- The “Social Behavior/Norms” theme received thirteen comments, all from the female restroom graffiti wall. Of the thirteen responses in this theme, three responses included:

- ◦

- “We leave food in the sink for each other so no one goes hungry”;

- ◦

- “the groupchat is more frequently used”;

- ◦

- “We warn each other about which bathrooms flood”.

- The “Environmental Qualities/Comments” theme received seven comments, all placed on the female graffiti walls. Of these responses, three responses included:

- ◦

- “We stand in each others dirty shower water”;

- ◦

- “We all touch wall of the shower with our butts when we shave”;

- ◦

- “We puke in the drains so when you turn on the shower the chunks splatter and we get to play ‘Dodge Em’”.

- The “Community Suggestions” theme received seven comments, all of which came from the male restrooms. Of the seven responses, three included:

- ◦

- “Not stuffing paper towels down the toilet”;

- ◦

- “Turning the showers all the way off”;

- ◦

- “Turning off the lights” (circled and underlined).

- The “Response” theme applied to comments that were made in reference to others that were already on the graffiti walls. These included three total comments, two from the female restrooms and one from the male restroom:

- ◦

- “LMAO” (in response to “We leave food in the sink for eachother so no one goes hungry”);

- ◦

- “LMAO x2” (in response to “LMAO”);

- ◦

- “This!!! Pease!!! Stop” (stop is underlined) (in response to “Don’t pee on the door handles”).

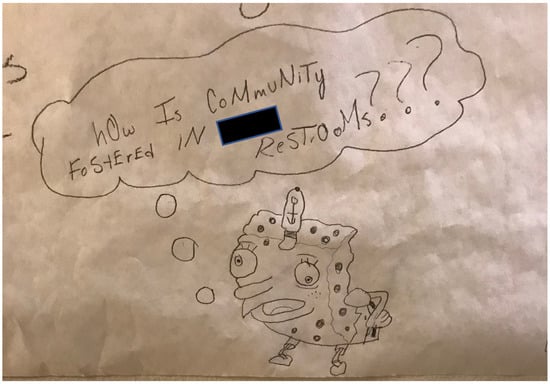

- The “Graffiti” theme was applied to two visual comments that were drawn on the female restrooms’ graffiti wall posters:

- ◦

- A sarcastic SpongeBob drawing/meme, as can be seen in Figure 8;

Figure 8. Sarcastic SpongeBob drawing/meme drawn on graffiti wall in P. Hall.

Figure 8. Sarcastic SpongeBob drawing/meme drawn on graffiti wall in P. Hall. - ◦

- A drawing of two girls having a tea party in the shower with the caption “We have fun in the bathroom :)” as seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Tea Party drawing on graffiti wall in P. Hall.

Figure 9. Tea Party drawing on graffiti wall in P. Hall.

- 6.

- The “Not Community” theme received one response from the female restroom: “What was the expected outcome of this question?”

- 7.

- The “Other” theme received one response from the female restroom: “Who would win? A genuine and probably well-meaning question about communities? A pencil and some sarcastic girls” (pros/cons chart).

There were multiple conversations publicly displayed on the graffiti walls in P. Hall with the majority of them concerning the shared use of the restrooms and showers. In the posted comments, the residents acknowledged their own and each other’s behaviors (i.e., food left in the sink or urine on the seats). Other comments highlighted the less-than-pristine conditions of the showers and toilets resulting from the shared use by the residents. The collection of comments on the graffiti walls suggest that these behaviors and shared bad conditions are what the bathroom community is fostered around in P. Hall.

4. Discussion

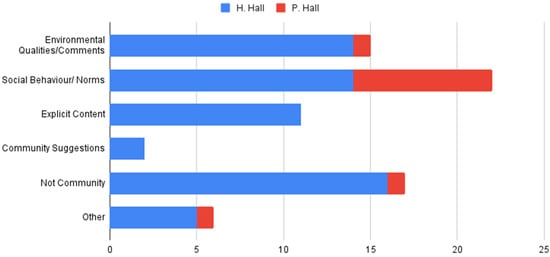

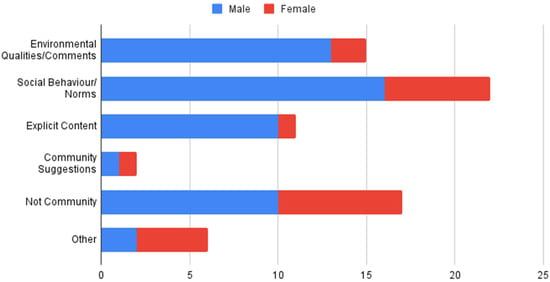

From the comment boxes placed in H. Hall and the comment boxes and graffiti walls implemented in P. Hall, several observations were made using the themes identified from participants’ responses. While some of these inferences have been alluded to thus far in the presentation of these probes and their findings, we aim to make more explicit the differences between the locations and methods of the research used.

First, referring to the comment boxes as a whole, the most popular response categories of the 72 collected responses included “Not Community” and “Explicit Content”. “Not Community” accounted for 16 responses and was almost evenly distributed between male and female responses collected from the comment boxes (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Another 16 comments placed in the theme, “Explicit Content”, with most collected from the male restroom in H. Hall. Overall, these findings signify a sense of retaliation in response to our research question. This can likely be attributed to the anonymous and secret nature of the boxes, resulting in participants’ tendency to be more negative and vulgar in their language. Moreover, because these responses largely came from male restrooms (51 male versus 21 female), this implies that males are less inclined to think of restrooms as a space for cultivating community and are more likely to have hostile attitudes on the subject. However, the limited statistical results prevent us from drawing a definite link. Additionally, these comments largely came from the comment boxes in H. Hall, implicating a more negative response from restroom users in an academic building (housing disparate classes from various departments) versus the more intimate residential setting in P. Hall. Still, because both “Not Community” and “Explicit Content” comments were submitted in P. Hall, and we were not able to collect as many responses, the results could be somewhat skewed.

Figure 10.

A comparison of the thematic analysis of the responses collected in comment boxes in H. Hall and P. Hall semi-public restrooms.

Figure 11.

A comparison of the thematic analysis of the responses collected in comment boxes in male and female restrooms (including H. Hall and P. Hall).

The second most popular response category overall (and the most popular response category for P. Hall) was “Social Behavior/Norms”, resulting in 15 total comments. This category manifested in different interpretations such as “we learn who has what shoes”, “a place to gossip & complain, a place to hide & talk with friends”, and “by washing your damn hands”, to name a few. These comments can largely be interpreted as giving recognition to a restroom community by noting social interactions, typical exchanges, and a common concern for restroom users. Because comments from this category were found in both H. Hall and P. Hall, this type of restroom community is able to span public and private areas, suggesting a common restroom culture between strangers, acquaintances, and friends.

“Environmental Qualities/Comments” elicited 11 total comments, referencing the smells and sounds respondents experienced as well as the aesthetics of these spaces. Many of this category’s responses collected from H. Hall related to the appearance and the conditions of semi-public restrooms on the university’s campus and not just the particular restrooms in H. Hall. This implies there may not be an attachment to the semi-public restrooms on campus; however, a comment collected from P. Hall, in which a participant states that “nothing makes a bonding experience like not having hot water for weeks on end”, implies that bonding occurs with the shared restrooms and showers in the residence hall. Residents also reference their knowledge of the restrooms’ quirks and shared experiences within the space, suggesting a more general sense of campus restroom community than just that of H. Hall.

These differences in the majority of comments received from both H. Hall and P. Hall suggest a complex yet shared mentality on restroom communities; drawing from the collective nature of “Not Community”, “Explicit Content”, and “Social Behavior/Norms”, community in restrooms is all at once a crude, social, and experiential oxymoron. Despite this shared approach, the nuanced replies to our research question must be noted. Overall, H. Hall’s comments represented a reaction to the strange question in a semi-public place, while the responses in P. Hall demonstrated an opportunity to write down things they had likely shared with residential community members already. In this way, asking “How is community fostered in (REDACTED) University restrooms?” in a transient space used by many informs a different interpretation than that of the residential communities at P. Hall.

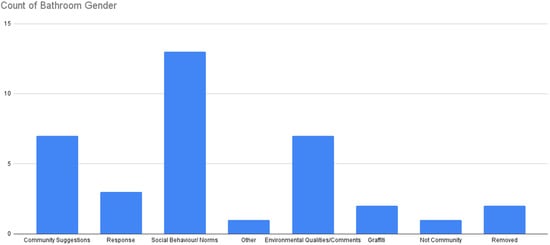

This phenomenon could be more clearly observed in the analysis of the graffiti walls as well. Similar to that of P. Hall’s comment boxes, the most popular graffiti-wall response categories included “Social Behavior/Norms” and “Environmental Qualities/Comments”. “Social Behavior/Norms” again focused on interactions between restroom users, with 22 responses (Figure 12). While recounting typical restroom interactions, participants turned comments about the space into references about a community as well, such as with the comment “We bond over not being able to sleep when the toilet won’t stop flushing.” This presence of an implied community is further reinforced through the use of a communal “we” or the proverbial “you” rather than participants using “I” to talk about individual experiences in nearly all response categories.

Figure 12.

Thematic analysis of the responses on the graffiti walls in P. Hall’s semi-public restrooms.

The “Environmental Qualities/Comments” response category continues this trend of an implied community; while the seven responses in this category largely focus on restroom cleanliness and efficiency, the nature of these comments seemed to take on a more public-facing tone due to the visible nature of the graffiti walls. Respondents took to “calling each other out” via comments such as “We leave food in the sink for each other so no one goes hungry”. With this, sarcastic and joking humor replaces the negative and contentious language used in the “Not Community” and “Explicit Content” responses found in the comment boxes.

A category emerged in the graffiti walls’ data named “Responses”, or remarks made in reply to other content on the graffiti wall. Some responses were directed towards another participant’s writing; these responses often expressed agreement or approval, such as “LMAO” and “LMAOx2” in response to “We leave food in the sink for each other so no one goes hungry”. Other responses were directed towards the research question itself, such as one participant’s drawing of a sarcastic SpongeBob meme with the speech bubble “How is community fostered in [REDACTED]’s restrooms???” This SpongeBob meme is a manifestation of playful online culture that has spilled into the physical world, painstakingly drawn by a participant on the graffiti poster [18]. The sarcastic and joking nature of this respondent community continued elsewhere on the graffiti wall with a tally chart labeled “Who would win? A genuine and probably well-meaning question about communities? A pencil and some sarcastic girls”. This playful tone that we had tried to implement in our research efforts early on in this study with the focus group was finally reciprocated (albeit to our detriment).

This sarcastic and playful character to the responses carried over most evidently to two other categories. A new category for graffiti walls is aptly named “Graffiti”, which includes drawings and other elements that are not text. While this category was not previously mentioned as a comment box category, there were drawings submitted as responses that were categorized under “Other” in both H. Hall and P. Hall. Examples of such sarcastic and playful responses that draw on internet culture include “I like turtles”, “got ‘em” (with image of an OK hand sign), and “Sometimes people talk in line, doing lines, juul”. The comment “I like turtles” is an internet meme of a televised interview of a young child at a country fair [19]. The OK hand sign is in reference to a popular game among adolescents called The Circle Game. The rules of the game are as follows “The Circle Game is a game of peripheral vision, trickery and motor skills. The game starts out when the Offensive Player creates a circle with their thumb and forefinger somewhere below his waist. The goal is to trick another person into looking at his hand. If the victim looks at the hand, he has lost the game, and is subsequently hit on the bicep with a closed fist, by the offensive player. Online, people have begun hiding hands making the circle symbols in various images to trick people into finding it” [20]. Finally, the comment response “Sometimes people talk in line, doing lines, juul” is in reference to a lyric from Miley Cyrus’s song “We Can’t Stop” [21]. Whether outright playing a game with the researchers, catching them off guard, or referencing memes nonsensically, the participants playful and sarcastic responses are most evident in the “other” and “graffiti” categories for both the comment boxes and the wall poster probes.

The findings from both the comment boxes and graffiti walls denote a consistent emphasis on comments from the “Social Behavior/Norms” and “Environmental Qualities/Comments” categories. These are therefore important aspects of semi-public restrooms while characterizing restroom community in both the context of H. Hall and P. Hall. Still, it should be noted that the impact of spatial qualities (academic versus residential), format (comment box versus graffiti wall), and the genders (male versus female) represented differences in the type of comment, tone of the comment, and overall idea of community (or the rejection of one). While a general consensus on restroom community was not identified, these themes paralleled our initial concerns of comfort, privacy, function, and design within semi-public restrooms. The acknowledgement of these themes across the methods used between the two locations demonstrate evidence of community in restrooms, even though the idea of one may differ based on spaces, spatial affordances, and genders.

5. Conclusions

This was an exploratory investigation into how communities were fostered in semi-public restrooms. Thus, the methodological efficacy of utilizing probes to address sensitive topics in sensitive settings was the main topic of investigation.

Six lessons were learned through the investigation that are transferable to other research endeavors in sensitive spaces that require a modicum of playfulness:

- Participatory design is possible in sensitive spaces and around sensitive topics.

- A level of anonymity is a requisite for meaningful participatory design in sensitive spaces.

- Playfulness is a requisite for participatory design recruitment and activities in sensitive spaces.

- Participatory design probes need to be provocative to foment opinion and evocative to draw reactions.

- Power relationships may impose definitions of sensitive spaces that are not accepted by all participants.

- Participatory analysis is needed to understand the ambiguous nature of playful and anonymous responses.

Overall, anonymous probes, which include both the comment boxes and the graffiti walls, served their intended purpose of collecting responses in sensitive areas. However, the level of anonymity after the study was understood to be two levels: first, anonymity of the respondent (graffiti wall) and second, anonymity of the comment and respondent (comment box). The second level of anonymity resulted in a high number of inappropriate, insulting, and vulgar comments. Such, it would be advised that in future research activities, if the second level of anonymity is not needed, that it be avoided.

Despite the playful nature of the study’s aesthetic and language, encouraging participation proved to be a difficulty as the study attempted to engage students in the somewhat personal and taboo topic of restrooms. While students seemed to be more willing to participate when afforded anonymity, it was particularly difficult to draw interest in the in-person focus group. Regardless, the participatory mindset of the research was a successful way of analyzing and categorizing the more ambiguous comment responses. In addition, on the whole, it was a successful way of approaching this study, thereby accounting for the needed participatory approach to develop a collective understanding of the restroom community.

Future research could look at understanding the difference in how genders understand restroom community and if such understandings hold true in gender-neutral restrooms. Additionally, research should be undertaken to test out a variety of prompts within the same restrooms to better understand what motivates participants to join in by casting a comment or drawing on a graffiti wall. Furthermore, there are opportunities for future research about, and in, semi-public restrooms where a continuous community exists (school, workplaces, etc.) and semi-public restrooms where a community does not continuously exist (airports, train stations, shopping malls, etc.). These types of communities, along with their characteristics and determinates, should be more consciously considered by designers and architects.

The six lessons presented in this paper can further the use of PD in the understanding and design of spaces in semi-public restrooms. This study can provide the tools and insights for understanding how community is conceived in areas that were previously too difficult to access. By providing takeaways that are relevant to designers, policy makers, and educators, these outcomes have the ability shape spaces, inform actions, and even foster communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.-N.S., N.D.M. and M.S.; methodology, N.D.M. and M.S.; investigation, N.D.M. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.D.M. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, E.B.-N.S., N.D.M. and M.S.; visualization, N.D.M. and M.S.; supervision, E.B.-N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the anonymous, public, and optional nature of the participatory methods.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study’s focus groups. Because of the anonymous, public, and optional nature of the participatory method, informed consent was not applicable for other participants.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to our colleagues Susan Booher and Luiza Souza Correa, whose efforts in the initial development and implementation of this study made the authoring of this paper possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Forbes, D. The O’Hare Shit-in: Airports, Occupied Infrastructures, and Excremental Politics. Society and Space, 2017. Available online: https://www.societyandspace.org(accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Gordon, B. Embodiment, Community Building, and Aesthetic Saturation in “Restroom World,” a Backstage Women’s Space. J. Am. Folk. 2003, 116, 444–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaver, W. Cultural Probes-Probing People for Design Inspiration; SIGCHI.DK: København, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, A.; Hemmings, T.; Rodden, T.; Cheverst, K.; Clarke, K.; Dewsbury, G.; Hughes, J.; Rouncefield, M. Designing with Care: Adapting Cultural Probes to Inform Design in Sensitive Settings; Ergonomics Society of Australia: Brisbane, Australia, 2003; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- OSU Bathrooms [@OSUBathrooms]. (13 December 2019). Mens, Foundation Building, East Wing: Sometimes Finals Might Make You Want to Crawl into a Hole. Conveniently, This Bathroom Has One Ready to Go! 4/5 Stars. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/B6Bpr5qBubg/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- OSU Bathrooms [@OSUBathrooms]. (15 March 2019). Mens, Hinsdale Wave Lab, 1st Floor: Wonderful Wave Accents, Possibly the Most On-Theme Bathroom on Campus. 4.5/5 Stars. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BvCdEpJl_Bv/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- OSU Bathrooms [@OSUBathrooms]. (10 January 2019). Mens, Langton, Basement: This Wall of Infinite Urinals Has An interesting Places-to-Pee to Privacy Ratio. It also Provides a Great Chance to Make Accidental Eye Contact with Half Naked Faculty Members. 2/5 Stars. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bsdx5wmnTTW/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- OSU Bathrooms [@OSUBathrooms]. (5 February 2019). Batcheller, Womens, 1.5th Floor: It’s Hot! The Faucet Drips! The Window Doesn’t Shut All the Way! 2.5/5 Stars. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BthHP0aFoZj/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- OSU Bathrooms [@OSUBathrooms]. (25 January 2019). BSingle User, ALS Building, 4th Floor: On-Pot Entertainment Offered in the Form of Various Reading Options, Scented and Unscented Hand Lotions Around Well as Complimentary Menstruation Management Products. 5/5 Stars. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BtEeJXPneVg/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Elizabeth, B.-N. Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers. In Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design; BIS Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalp, N.; Yildirim, K.; Bozdayi, M.; Cagatay, K. Consumers’ evaluations of fitting rooms in retail clothing stores. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Hanington, B. Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions; Rockport Publishers: Beverly, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jarke, J.; Maaß, S. Probes as Participatory Design Practice; De Gruyter: Oldenburg, Germany, 2018; Volume 17, pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lawhon, M.; Herrick, C.; Daya, S. Researching sensitive topics in African cities: Reflections on alcohol research in Cape Town. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2014, 96, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasovaara, S.; Lucero, A.; Olsson, T. Outlining the Design Space of Playful Interactions between Nearby Strangers. In Proceedings of the AcademicMindtrek’16, Tampere, Finland, 17–18 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lively, T. On the Shithouse Wall: The Communicative Value of Latrinalia. Master’s Thesis, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Björgvinsson, E.; Ehn, P.; Hillgren, P.-A. Participatory design and “democratizing innovation”. In Proceedings of the 11th Participatory Design Conference, PDC, Sydney, Australia, 29 November 2010; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mocking Spongebob. Know Your Meme. Available online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/mocking-spongebob (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- I Like Turtles. Know Your Meme. Available online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/i-like-turtles (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- The Circle Game. Know Your Meme. Available online: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/the-circle-game (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- We Can’t Stop. Genius Lyrics. Available online: https://genius.com/Miley-cyrus-we-cant-stop-lyrics (accessed on 29 November 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).