Abstract

Zebrafish (ZF) have gained increasing attention in developmental neuroscience due to their experimental tractability, favorable ethical profile, and translational value. However, the expanding use of the ZF model has also highlighted the need to consider species-specific differences in relation to early social and emotional development. This review adopts a comparative and ethological perspective to examine early social interactions in ZF and mammals, integrating evidence from non-altricial vertebrates and teleost species with parental care (cichlids). Selected illustrative ZF papers were discussed, while Cichlids fish were chosen as a complementary, translationally consistent subject for developmental behavioral studies. The analysis focuses on developmental stages that are relevant for behavioral phenotyping in models of neuropsychiatric conditions. Zebrafish offer multiple methodological advantages, including suitability for high-throughput experimentation and substantial genetic and neurobiological homologies with humans. Nevertheless, the absence of mother–offspring bonding limits the modeling of neurodevelopmental processes shaped by early caregiving, such as imprinting and reciprocal regulatory interactions, instead observed in cichlids. Accumulating evidence indicates that early interactions among age-matched ZF are measurable, developmentally regulated, and sensitive to environmental and experimental manipulations. Within a comparative approach, these early conspecific interactions could be analogs of early social bonding observed in altricial mammals. Rather than representing a critical limitation, such species-specific features can inform the investigation of fundamental mechanisms of social development and support the complementary use of ZF and mammalian models. A contextualized and integrative approach may therefore enhance the translational relevance of ZF-based research, particularly for the study of neurodevelopmental disorders involving early social dysfunction.

1. From Rodents to Fish: The Many Meanings of “Replacement” (676)

In the most orthodox and current vision of the 3Rs of the Burch and Russel Book [1], Replacement refers to replacing formally and legally “sentient” animal species with computer simulations, algorithms of machine learning, cell lines, and similar approaches. Therefore, for some “strictly orthodox perspectives”, any “ameliorative” change in experimental design, that does not avoid the use of live subjects, does not represent a veritable Replacement. A less conservative version proposes the shift from “sentient” species towards “less sentient” ones with the replacement of rodents by Drosophila flies or Aplysia mollusks, as the most classical example [2]. Our interpretation suggests either a progressive or an abrupt shift from animal species belonging to different animal groups of decreasing “sentience”: replacing apes (less exploited in animal experimentation) with monkeys (macaques, marmosets, capuchin monkeys, etc.), monkeys with carnivores (dogs, cats, ferrets, etc.) or carnivores with rodents (rats, mice, spiny mice, gerbils, etc.).

According to this latter statement, we perceive that shifting experimental lines, which for decades have been carried out on classical rodent species, towards fish as the preferred species, may yet represent an important step in ameliorating the general public perception of animal experimentation, while providing a cost-effective and easily manageable model suitable for developmental, genetic, and behavioral laboratory studies [3].

The Oxford dictionary defines Sentience as being “endowed with biological characteristics and prerogatives peculiar to human beings”. Its philosophical roots sprout from ancient debates concerning the (supposedly) profound differences between humans and animals. Two pilasters in the long way followed by this philosophical and logic terminology in the past centuries, are, respectively, Descartes and Saint Augustine.

We are deeply influenced by the species-specific capability to perceive suffering as described by Marion Stamp-Dawkins [4]. Animal suffering grade is defined as the capability of a single animal species to imagine (and plan) the strategy to actively avoid pain or distress, rather than basing such a grade in terms of a phylogenetic level (often measured as distance from Homo sapiens) or simply on the “complexity” of its central nervous system and/or main integrating ganglia [4].

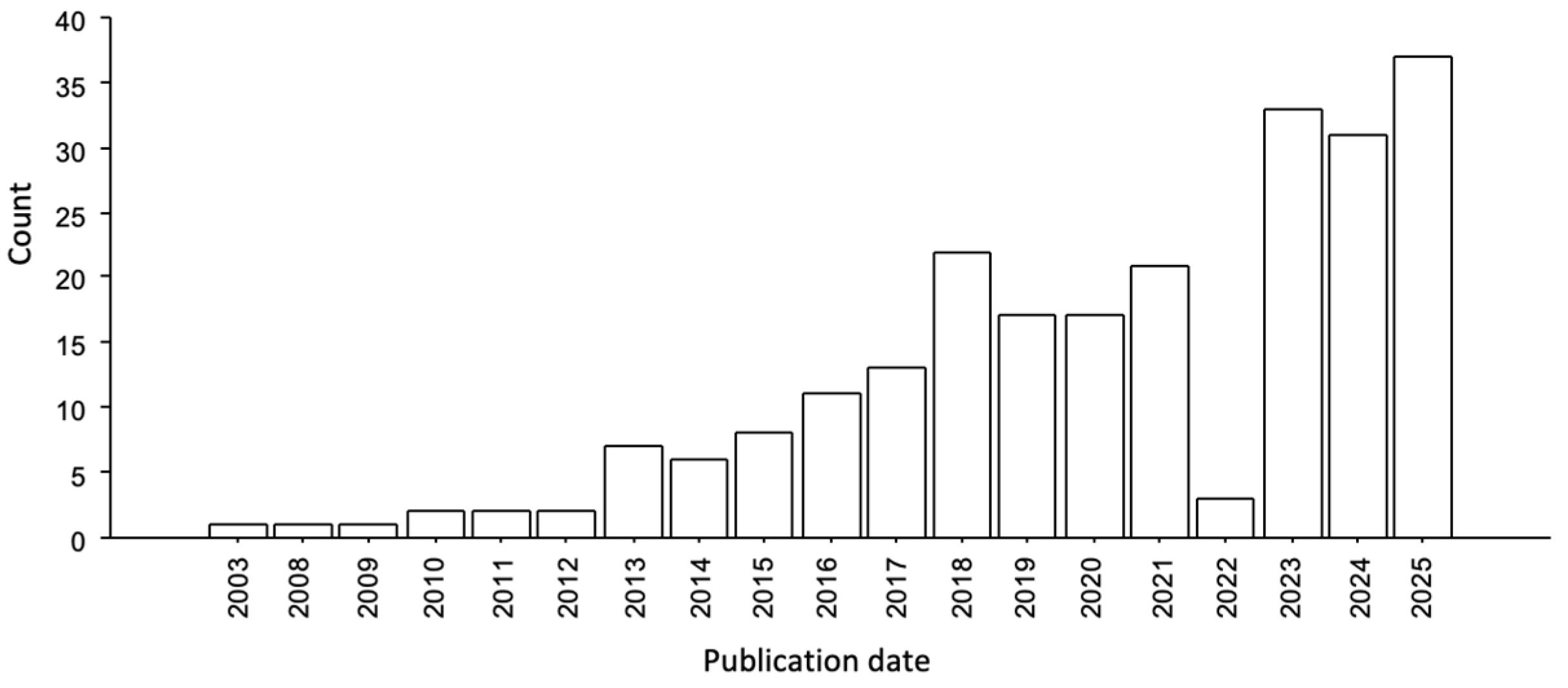

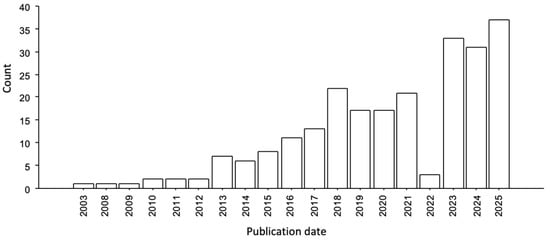

Following the book of Russel and Burch [1], which was gloriously and formally entered in the recent EU directive [5], influencing the animal experimentation and the scientific community, attempts to replace “sentient” as well as “evocative” species (the latter from the beginning of the 20th century regarding dogs, cats, and, progressively, apes and monkeys). As “evocative species”, we intend species that evocate a strong emotional reaction from the public, raising concerns about inflicting pain and suffering to animal subjects, considered quite similar to human beings. Apes and monkeys resemble humans, while dogs and cats for centuries closely share the same domestic environment with Homo sapiens. We are witnessing the emergence of non-mammalian species: Drosophila flies have long represented a solid common ground for genetic and even behavioral studies. ZF entered much later in such a scenario but rapidly achieved a podium position (Table 1 and Figure 1) [6]. Owing to its lower neuronal complexity compared with mammals, the ZF represents a suitable model for the application of the principle of Partial Replacement [2], especially when experiments are conducted using larval stages up to 120 h post-fertilization (hpf). However, sensitivity to the use of more or less evocative animal species is inevitably also influenced by sensitivity of the historical context being experienced. With wide differences among different continents and countries, due to even divergent cultural traditions, “lower level” vertebrates, such as fish or reptiles, are considered by the public to experience a minor level of suffering than mammals [4]. Marian Stamp-Dawkins mentioned that the perception of the sufferance by a given species is related to the capacity to represent a possible avoidance reaction when confronted by a noxious or stressful stimulus set (where, recognizably, mammals overcome fish), a statement echoed by the general public, particularly in some countries. Emblematic is the case of the so-called “Nemo effect”, picking up around 2003, presently in consistent diminution, which triggered a wave of unexpected sensitivity toward fish psychophysical welfare in the public [7].

Table 1.

A few selected examples of contemporary exploitation of the ZF model in neurobehavioral studies.

Figure 1.

Number of articles per year of publication extracted from PubMed database using “zebrafish” and “autism spectrum disorders” as keywords (last accessed on 31 December 2024).

Despite this positive trend, which favors Replacement through the ZF model, our present contribution aims to balance such a “ZF euphoria”, by focusing the attention on some of its limitations, particularly in the case of early social interactions, which in this species differ from those of mammalians. It is worth mentioning that some studies focus on a single hormonal index (oxytocin regularly involved in social bonding) that has evolved in ZF as a sign of “complex” mammalian social pattern [26,27]. However, considering the relevance of the investigation of the social domain for the study of neurodevelopmental disorders and the translational value of selecting early behavioral indicators of disease, the possibility of characterizing the first social interactions between mother–offspring in cichlid fish or embryo/larvae in no-altricial species and validating/comparing their ethological value in the ecological and evolutionary context of these species could provide a wider array of information on the development of social disorders. The novelty of the present review lies in reconsidering the apparent limitation imposed by the absence of mother–offspring communication in ZF models of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We propose that this limitation could be addressed by evaluating early social attraction among age-mates as a form of “postnatal parental behavior” or by employing other fish models that naturally exhibit parental care, such as those belonging to the Cichlidae family.

2. Zebrafish as a Model for Neurobehavioral Studies

The robustness of ZF phenotypes makes this species increasingly popular in neurobehavioral research, especially for the possibility to investigate the complex processes involved in degenerative brain diseases or mental disorders [28,29] (Table 1). The complete sequencing of their genome, the physiological and the anatomical homology with humans in most organs, the availability of well-characterized neuronal circuitries, the optical transparency of the embryos, and the external and fast reproduction of the species all represent the practical features that render ZF one of the most widely used model organism involved in the current scientific research [30].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that ZF constitute an alternative vertebrate model for the study of movement disorders, often associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD) [8,9,10,11], a pathological condition that could also involve depression and the loss of cognitive capabilities [31]. Among neurotoxins, methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) or 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) are the substances usually employed to induce ZF-based PD models. Both agents cause the loss of dopamine neurons and motor dysfunctions typically observed in patients affected by this pathology (reduction in speed and distance traveled, increase in bradykinetic- and dyskinetic-like behaviors, etc.) [8,9]. It is relevant to underline how cognitive decline or anxiety- and depression-like features represent often subtle and non-motor symptoms associated with this pathology [32,33]. ZF treated with rotenone, a pesticide widely used to produce PD-like symptoms in rodents, also exhibited olfactory deficits, impairment in learning capabilities and anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, probably associated with the loss of dopamine in the brain [34,35].

The fact that this species represents a relatively simple vertebrate, while at the same time possessing several conserved features across multiple levels of biological organization, makes ZF an appropriate animal model for investigating the mechanisms underlining learning and memory processes [36,37]. Some neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, are associated with impaired learning and memory capabilities, and many behavioral tests for ZF also allow some neurobehavioral impairments associated with this pathology to be elicited and investigated [38]. A recent study conducted by Boiangiu and colleagues highlights cognitive deficits and motor impairments in a ZF model of Alzheimer disease using a Y-maze test and object discrimination task, paradigms largely used to evaluate spatial learning and short-term memory in ZF [14].

Zebrafish are also largely implicated in neurotoxicological studies and behavioral teratology [39]: they are simply soaked in chemical solutions, the compounds penetrate the transparent embryo’s external membrane by passive diffusion [40], and the transparency of the larvae facilitates the observation of developing organs and the localization of protein [41], useful advantages to investigate morpho-functional changes upon chemical exposure. Different kinds of chemical pollutants may interfere with typical brain developmental trajectories, particularly during critical time windows, and induce alterations that may result in pathophysiological and behavioral deficits at a later life stage [42]. Intriguingly, the possibility to follow the neuro-anatomical changes in ZF from hatchery to adulthood represents a relevant advantage for analyzing the adjustment strategies to the environmental stressors or for identifying predictive indicators of susceptibility to environmental changes. Table 1 enlists some contemporary exploitation of the ZF model in neurobehavioral studies, including in the context of neurotoxicological research.

2.1. Basic Studies on ZF Biology and Ethology

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are an increasingly common model species. However, researchers often disregard complexities of their social behavior. As a result, most lab-based studies use rudimental and reductionist testing strategies, missing the subtleties that characterize ZF behavioral patterns. The few studies carried out under natural conditions are therefore of prominent relevance to design lab experiments reflecting ethological scores produced by natural selection [43,44].

Over the last two decades, despite the widespread exploitation of the ZF model in biomedical research, little is known about their natural history, including habitats, native behavioral interactions, and wild population genetics, important prerogatives to deeper understand its translational potential in current scientific research. Despite their popularity, the difficulties to collect ZF information from the wild could be due to the arduous nature of undertaking field trips to remote areas of India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, which are their remote native habitats. To improve basic knowledge about the ecology of wild ZF, Sundin and colleagues [45] described in detail field research conducted in collaboration with local scientists, visiting together several rivers in West Bengal and collecting information regarding wild ZF. They reported that the areas populated by ZF are characterized by a large variety of habitats: not only rivers, dense forests with turbid and slow-moving waters, and stagnant ponds with dense plant growth but also large mountainous and lowland streams/rivers, wetlands, or paddy fields [46]. All these areas have in common consistent daily temperature fluctuations and wide seasonal temperature variations. Interestingly, the most extreme environment where ZF have been found was a shallow pond on a sandbank with temperatures that could reach around 35.3 °C, while the coldest one was near a natural well with cold spring water, at a temperature around 24.5 °C [45].

As expected, although the differences between these habitats are evident, they observed ZF at extremely high densities performing shoaling behaviors, typical ZF natural behaviors [47]. Interestingly, field observations revealed that these loose social aggregations, or shoals, can vary depending on local condition and predation risk [47,48].

Zebrafish are known to be a highly social species that usually live in extremely high densities, occupying the same spatial area and forming very large shoals [48]. From an evolutionary perspective, this behavior likely provides multiple benefits, including protection from predators, who may be confused by the concomitant escape reactions of several individuals and thus cannot focus on a single target (“flash expansion”; [49,50]), improving foraging success or increasing the tendency to find and stay close to potential mates).

It has been demonstrated that ZF adjust the dimension of the “shoal” according to the amount of the space in their environment and the density of the group [44].

Different results also showed controversial observations regarding the timing of shoaling behavior. For example, Engeszer and colleagues [51] found that shoaling behavior started early in ZF development, specifically soon after hatching, but shoaling preference emerged only during the juvenile phase [52]. On the contrary, Buske and Gerlai [53] suggested that it was age-dependent: they observed a decreased distance between shoal members with age. The differences observed may result from methodological differences and from the varying concept of “shoaling behavior”. As Buske and Gerlai mentioned [53], most studies trying to investigate the timing of shoaling behavior have focused on the reaction of an experimental fish tested singly towards a fish group, usually divided through a transparent barrier. These kinds of studies probably evaluated social preferences or agonistic responses between fish, rather than the conspecific recognition or shoaling tendency. In fact, McCann and Matthews [54] observed how ZF maintained in isolation did not show a preference for a shoal of conspecifics, suggesting that species identification was probably learned and, above all, mediated by other specific stimuli, such as vision capabilities and olfactory or chemical cues [55,56].Therefore, the most converging conclusion indicates that timing is a critical key factor for developing shoaling behavior and that there is a sort of individual “imprint” on a particular visual phenotype, particularly evident during the juvenile period [51,57,58,59].

It is worth mentioning that ZF groups are commonly indicated indifferently as either shoals or schools, even if a distinction between the two terms has been largely discussed. Specifically, shoaling describes a simple aggregation of fish that “remain together for social reasons”, while schools are shoals that are coordinated in the form of synchronized and polarized swimming performances [50,60,61,62]. Miller and Gerlai [50,60,61,62] demonstrated different features of shoaling and schooling behaviors: the first is faster and less dense than the second one.

Dominance hierarchies have been observed in ZF of both sexes [63]. Chasing behavior represents the most common responses marking the resolution of a fight. It consists of accelerated movement towards a second fish, which avoids the first, a sign of establishment of social dominance. On some occasions this behavior culminates in biting behavior, a physical contact of the conspecifics after a quick movement, often around the gill region or fins of the second fish. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that changes in body colors are components of complex behaviors constituting the “aggressive pattern” in ZF. In particular, changes in body coloration occur in response to environmental stimuli such as changes in social context: dominant fish typically appear darker and occupy the entire available space, while the subordinates appear pale and are mostly stationary in a small area of the aquarium [63,64].

Regarding ZF reproductive capabilities, an enlightening paper by David Parichy describes ZF mating behavior in detail [65]. Similarly to the information reported in a paper published some years before by Spence and colleagues [63], the study reports that the courtship behavior consists of an initial chasing of the male towards the female’s side or tail, followed by circling behavior with raised fins. If the female does not respond, the male may alternate between circling and swimming back behaviors; otherwise, once over a spawning site, he swims closely alongside the female, inducing oviposition. Spawning activity typically coincides with the first exposure to light after darkness and may also occur later in the photoperiod, particularly in wild-caught ZF held in captivity. Therefore, laboratory manipulation of daylight cycles may provide a practical strategy to schedule spawning activity.

2.2. A Paradigmatic Case: ZF as an Animal Model for ASD

We firmly believe that ZF are a valid and validated model for a variety of biomedical and toxicological studies and that they represent a sound avenue for ameliorating the progress of biological knowledge in a variety of established and emerging subfields. However, some peculiar differences with murine models emerge in translational studies of psychiatric disorders where the investigation of parental care, early inter-individual communication and social interactions between mother and pups could be particularly relevant when performing behavioral phenotyping of models associated with human early alterations in social behavior [66].

The case of the ASD (Figure 1) is a vivid example of a translational effort deserving more attention. At least partially, the establishment and maintenance of social bond are relevant components of this disorder, since restoring and maintaining the social conditions in the range typical of the human species represent prerequisites and important conditions of most of the current clinical approaches for patients affected by ASD [67,68].

While ASD etiology is indeed rooted in early—often prenatal—neurodevelopmental disruptions, postnatal stages still represent critical periods for the refinement of neural circuits and the emergence of social and communicative behaviors. The information provided by comparative ethological studies is often limited to a small number of “traditional species,” as already noted by Franck A. Beach in 1950 [69]. In this context, the introduction of ZF as a model to complement monkeys, dogs, pigeons, and rodents in behavioral research represents an important step forward for the comparative approach. Such data—particularly regarding the neural substrates underlying specific behavioral traits—can be instrumental for modeling within comparative neuroscience. Moreover, following Dawkins’ perspective and the Directive 2010/63/EU [5], postnatal ZF manipulations typically involve early larval stages (up to 120 hpf), during which the estimation of suffering is lower [4], providing an additional ethical advantage. Finally, postnatal ZF models are particularly valuable for studying the onset, progression, and modulation of ASD-like phenotypes, including gene–environment interactions and potential environmental or pharmacological countermeasures.

The reference paper authored by Tropepe and Silve [70], published in a sophisticated journal that integrates genetic, neuro-anatomical, and behavioral interactive components, reviews the validity of ZF for disentangling the mechanisms and processes involved in the pathophysiology of ASD. The authors underline that the recent molecular and embryological techniques, particularly developed in ZF, allow a fine analysis of genetic “causes” and “co-causes” of ASD. Zebrafish allow cost-effective and precise genetic stains for above-mentioned genetic components and researchers can easily compare the structure and function of the adult ZF brain with those of mammals. Neurogenesis, with its primary and secondary phase, has striking similarities with that of other vertebrates, and the morphogenesis is well defined and comparable. Neural determination and pattern formation are also similar [70]. The evolutionary conserved nature of sociability in ZF suggests that it could be a prominent animal model for investigating neurodevelopmental disorders associated with social deficit [71]. The versatility of gene-targeting manipulations in ZF embryos represents an attractive advantage for disease modeling. Liu and colleagues reported that by adopting a specific genome editing technique, it is possible to create mutants of larval and adult ZF with “autism-like” phenotypes [23]. In particular, the authors found that these mutants showed repetitive behaviors and differences in the social domain, with specific alterations in shoaling behaviors and preference for conspecifics [23]. From a comparative point of view, these abnormal behaviors do not appear so much “distant” from the reduction in social interactions, impairments in social novelty or preference in the three chamber paradigms observed in murine models of ASD. Mutant ZF also apparently displayed repetitive behaviors in the novel tank test, an index of autistic-like behavioral profiles, which, in a comparative way, closely resemble the increased self-grooming behavior in the ASD rodent animal model [23].

What about investigation of the social domain during the early postnatal days?

Given the relative early onset of symptoms in ASD, the study of early social interactions and communications during the neonatal phase represents a great opportunity to carry out behavioral phenotyping during the early developmental phases, while identifying “critical windows” of intervention and potential strategies of treatments [72,73].

In rodents, many behavioral tests are available for evaluating sociability, such as reciprocal social interactions, parental behaviors, sexual interactions, or aggressive encounters [74]. The analysis of ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) represents a qualitative method to identify behavioral responses in developing mice as an index of early communicative behaviors and mother–offspring interactions [75], meaningful tools to investigate murine models of ASD impairments [76]. Specifically, pups’ vocalizations elicit in the dam expression of maternal behaviors such as licking, orienting, searching, or retrieving behaviors when pups are isolated from the nest [75,77], evidencing the pup as a member of the mother–pups dyad. Moreover, USVs could be elicited by quantifiable stimuli and follow a clear ontogenetic profile, also allowing longitudinal neurobehavioral analysis during very early postnatal development [75,78].

When considering the ZF model, although it offers relevant advantages given by its “innate sociability”, some “apparent” limitations specifically concern the difficulties in investigating complex behavioral patterns, such as individual social recognition during the early developing phase or early mother–offsprings interactions [79]. If, on the one hand, the external fertilization and the subsequent “individual growth” of the larvae represent relevant advantages to screen drugs or toxicants and define neuro-anatomical developing anomalies until adulthood, on the other hand, it does not allow the investigation of early mother–offspring interactions [80], particularly informative in animal models of neurodevelopmental disorders. However, the possibility of investigating early social interactions between ZF embryos or larvae represents a useful tool to study early changes in social behavior [81]. Chen and colleagues reported that ZF embryos treated with valproic acid (an antiepileptic drug strongly linked with developmental defects in children) showed hyperactivity and increased ASD-like larval social behaviors [80]. Interestingly, the authors observed an increase in the nearest neighbor distance and in the inter-individual distance among the treated larvae, suggesting that starting from the first days after fertilization the investigation of the social domain in ZF could be particularly informative of unconsolidated fish groups [80]. As in mammals, social behavior could also be associated with oxytocin levels in ZF [26]. Recently, Gemmer and colleagues [26] demonstrated that oxytocin receptors influence the development and maintenance of social behavior. The hormonal levels of oxytocin are involved in the regulation of social behavior in larval and adult ZF [82], suggesting that some physiological features are common between mammals and fish, and neuronal circuits involving oxytocin could play a relevant role in early social interactions in the ZF model. Although the relationship between the parental generation and offspring is absent in ZF, the investigation of species-specific parental care in other fish species, such as Cichlids, or early social and communicative behaviors between ZF embryos and/or larva could overcome this apparent limitation.

2.3. The Cichlidae Fish Family, the Most Emblematic Example of Teleost Parental Care

The hiatus between mammalian early social experiences and parental/filial bonding in fish allows several reflections on how easy and scientifically sound it is to “translate” from mammal models (mostly, altricial rodents) to the ZF ones, especially when considering the early post-hatching phase. We enlist some selected fish cases describing rather sophisticated parental care [83], wondering if different fish species may represent a better choice in establishing ASD models.

Within the heterogeneous fish universe, the teleost fish family Cichlidae provided sophisticated parental care such as nest building, active egg ventilation, mouthbreeding, etc. [84,85].

These freshwater teleost fish represent a useful model for studying the evolution of parental care and the basis of conspecific recognition. Parental care has been observed in males, females, or both and provides an excellent opportunity to investigate reciprocal parental (parents vs. offspring and vice versa) recognition.

Biparental species are evolutionarily more ancient than uniparental ones because they are distributed in a wider geographical area and, probably, have had more time to spread their eggs from one location to another. Both males and females take care for eggs laid on a substrate and continue guarding the larvae until the fries feed independently [86].

Ethologists and evolutionary biologists have focused on the study of tilapias (a Cichlid species), because they exhibit a wide range of parental care behaviors. Some species are substrate brooders, caring for eggs in the cervice or in the nest, while others are ovophile mouthbrooders. Specifically, these species already retain eggs in their mouth before hatching to reduce the risk of predation, mitigate the adverse effects of environmental stressors, or increase the survival and rate of the embryos development [87]. Astatotilapia burtoni is an example of a maternal mouthbrooder: the female refrains from self-feeding while caring for offspring inside its mouth. After egg deposition on the substrate, the female collects the eggs into the buccal cavity where they are fertilized by the male, and they remain there for incubation for 2 weeks before being released. This behavior represents an anti-predator parental strategy because, when the predator approaches the brood, the parent does not attack the predator but simply swims away, taking the fry into their mouth. Generally, only one parent performs this care, unless the fries cannot fit all in their mouth, thereby inducing a second parent to participate [88].

Among the least studied forms of parental behavior in cichlid fishes, the fin digging behavior deserves attention [89]. It consists of rapid beating of the pectoral fins and undulating movement of the body to move bottom materials, apparently increasing the availability of food for the offspring or defending the brood. Behavioral analyses of two common cichlid fish (A. nigrofasciatum and A. octofasciatum) revealed that the number of digs significantly increased with age and that it could be related to parents’ satiation and the foraging need for the offspring. Interestingly, the maximum increase in fin digging behavior was observed between the 3rd and 10th days of larvae exogenous feeding rather than during the transition to exogenous feeding, probably because complete self-feeding occurred before the development of gastrointestinal system [90].

Sex-related differences in fin digging behavior were also reported. Females increase digging intensity soon after pro-larval hatching, after which males display compensatory behavior during periods of reduced female care, specifically during early offspring development. Moreover, males collect the chaotically moving pro-larvae, removing dead individuals and fanning the nest. Parental fin digging most likely evolved through the extension and functional modification of adult foraging behavior toward brood provisioning.

Some cichlids lay eggs on mobile leaves, allowing parents to relocate eggs when survival threats arise or retrieve them if the substrate detaches from the nest [91]. For example, lamprologine cichlids use the inside of empty gastropods as protected nest sites [92], while the parents in Amazonian cichlid Symphysodon spp. produce mucus secretions to nourish offspring after hatching [93]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that egg-care is largely visually and chemically mediated: in jewelfish (Hemichromis bimaculatus), parent–young recognition is mediated by olfactory cues until 20 days post-hatch when juveniles leave their parents [93]. Chemicals released by offspring trigger parental coloration and care behaviors such as fanning or nipping, which favors brood agitation and increases oxygen availability [94].

When directly comparing small rodents to cichlids, not considering the lower costs of breeding and maintenance and the genetic manipulation of a large number of subjects in fish, early offspring–mother bonding with active and proactive behaviors in both species acts to meet offspring needs and the reciprocal tuning of survival strategies through typical behavioral patterns and dyadic vocalizations. In particular, the acoustic communication exploited by cichlids when parenting [95] represents a valid similarity with extensively used USVs to communicate between mother and offsprings [96], behavioral features largely investigated in animal models of ASD [97]. Moreover, some cichlids species (Discus fish, Symphysodon spp., [98]) provide direct nourishment to fries through skin mucus, somehow resembling the availability of milk produced by mammals.

3. Larval ZF Social Schooling and Networking as a Possible of Early Species-Specific Social Experience

How is it possible to mold a parental bond in fish dispersing dozens of eggs and never having any behavioral contact with their offsprings? If we observe inter-individual social patterns expressed at various larval stages, we notice that shoaling is already present at egg hatching and that inter-individual relationships, both among brothers/sisters or age-mates from different hatches, already possess quantitatively and qualitatively sophisticated features [53]. Is it therefore possible to establish which is the pivotal role directing the very early social attraction, cohesion, and coordinated shoaling/schooling movements in space? Is it therefore possible to exploit these specific social behavioral stages to dissect the component that establishes and maintains such bonding? Is this early social bond considered a predictive index of inter-individual disturbances, eventually leading to still uninvestigated models for early social behavioral pathologies, including ASD?

Humans are altricial mammalian species. Children depend on their caregivers for survival for a rather long time after the end of the lactation period. Somehow, the translational value of nonhuman primates was established a long time ago [99].

In recent decades, also due to the rich mass of ethological and psycho-biological data, altricial rodent species were found to have in common with primates a vast variety of behavioral patterns, such as in their social interactions. Maternal (and paternal) behaviors revealed several similarities with primates, making rats and mice a reliable and massively exploited translational model for humans [100].

When shifting to fish, the parental performances of Cichlidae [101] prompt a reflection on early social bonding phenomena across vertebrate classes, particularly between the most exploited rodent species and ZF. The capabilities to establish social bonds based on individual recognition—clearly documented in adult mice [102,103] and in other mammals such as apes and monkeys [104]—appears problematic in fish. In other words, parental–offspring bonding in fish seems to rely on a simplified and largely automatic process: an affective link between parents and early larval stages is nearly absent, and ZF respond to fixed action patterns (FAPs) directed toward conspecifics [105].

Since early experiences play a paramount role in mammals—particularly attachment, loss phenomena [106], and suckling [107], which constitute a baseline for the entire social trajectory of an individual—and these processes cannot be examined in fish within translational behavioral frameworks, does this imply that ZF cannot genuinely serve as models for early social relationships with translational relevance to human developmental behavioral disorders? Does this represent an insurmountable limitation?

Any social organism that gains the capacity for autonomous individual life could be pre-programmed to form species-specific social bonds with conspecifics. In the case of ZF, an FAP is operational, enabling the newly hatched individual to recognize members of its own species, exhibiting an innate attraction toward them, and actively engaging in a multi-individual social group. This group assumes a “parental” role, providing anti-predatory protection, facilitating (social) exploration, and sharing information related to food search and selection [108,109].

This early “automatic” social bonding shares fundamental aspects with mammalian mother–offspring interactions, while representing a very early form of intraspecific recognition when ZF larvae attain autonomous and individual control of its external environment. To support the translational value of this phenomenon, it seems relevant to better scrutinize the early releasing signals emitted by just post-hatched age-mates, which functionally replace the parental figure. These attraction-driven response patterns may constitute reliable indices of early attachment and, in turn, provide predictive measures of early intraspecific behavioral disturbances. A study conducted by Stednit and colleagues (2025) demonstrated that larvae process visual and mechanosensory signals from their conspecifics, eliciting coordinated and complex social responses [110].

The behavioral phenotypes of species that exhibit parental care share some basic common behavioral traits with early social behavior among ZF age-mates. For example, murine maternal behaviors include maintenance of a stable temperature for the litter, active protection and nourishment of the pups, and nest-building behaviors. From a comparative point of view, early social care patterns among age-mates in ZF act as a form of “age-mate care”: being part of a shoal means benefitting from protection against predators, improving the foraging process, and increasing the tendency to stay close to familiar individuals. Zebrafish shoaling behavior is modulated by precise responses to conspecific movements, guided by chemical and visual orientation among age-mates, reflecting dynamic social cohesion rather than passive co-localization, similar to the innate maternal behavior towards offspring in rodents. This social early “age-mate care” in ZF is not a simple reflexive aggregation but involves social responses that engage defined neural mechanisms. Similarly to mammals, oxytocin signaling in ZF is critically involved in social interactions with conspecifics. For example, oxytocin receptors influence the development and maintenance of social preferences and shoaling behavior among conspecifics, further supporting the role of oxytocinergic signaling in social cohesion [26]. As in the “complex” mammalian mother–offspring bond, early larval social cues activate oxytocin-expressing neuronal populations, affecting affiliative behaviors, providing good evidence of François Jacob’s defined “evolution through bricolage steps” [111].

When focusing specifically on developmental studies of ADHD, rodent models typically rely on genetically modified models (e.g., deletion of DAT gene, [112]) or models based on easily reproducible prenatal or postnatal environmental insults (maternal exposure to alcohol [113] or neurotoxicant exposure [114]). As mentioned before, acoustic parent–offspring communication in both rodents and cichlids provide reliable translational effort aimed at disentangling ASD neuro-determinants and potential ways of intervention. In fish, the evaluation of behavioral effects after genetic prenatal (in cichlids, [115]) or postnatal manipulation, and prenatal or postnatal environmental insults, respectively, on cichlids or ZF larvae, could represent a great opportunity to disentangle comparative pathways from rodent models. Similarly, the mammalian literature on the medium- or long-term effects of early social isolation [116] may possibly be reproduced in ZF or cichlids by gently removing, from variable periods of time, individual larval subjects, respectively, within the shoal or the cichlid “nest”.

Attraction toward high densities of conspecifics begins at 7 days post-fertilization (dpf), while complex social patterns emerge between 10 and 16 dpf, revealing a clear ontogenetic trajectory from 9 dpf—when larvae remain in proximity—to 15 dpf, when ZF commonly swim in cohesive groups [117,118]. Notably, the same attraction rule has been observed during adulthood, suggesting that ZF possess the neural and behavioral mechanisms to engage in social interactions at early stages and the early post-hatching social patterns could predict the organization of adult social behavior [110]. Intriguingly, this relationship could represent a critical point for investigating early social impairments in animal models of psychiatric disorders [118]. An “olfactory template”, a kind of imprinting-like phenomenon to recognize familiar kin, occurs at 6 dpf in conjunction with genotypic characteristics related to the immune system (MCH) [117]. Embryos after hatching do not discriminate between self- or non-self-odors; however, the exposure to kin individuals 6 dpf is necessary for the development of “olfactory imprinting”, instrumental to recognize familiar individuals. A time-sensitive learning mechanism drives phenotype matching and likely involves genetic predispositions linked to MHC genes expressed in olfactory receptor neurons. Interestingly, imprinting evolved to prevent inbreeding at adulthood while simultaneously acting as an FAP that establishes the foundation for subsequent social interactions [107]. This early social behavior could represent the first signal of communicative pattern in non-altricial species, and its multisensory regulation suggests that this FAP exerts a role in evoking shoal cohesiveness through olfactory and visual cues (Figure 2). Interestingly, its ontogenetic profile and modulation in response to stressors offer the possibility of investigating individual susceptibility to environmental challenges and identifying specific developing windows of intervention to counteract the typical impairments of the social domain in ASD animal models.

Figure 2.

The earliest signs of communication among ZF age-mates may serve as a valuable tool for investigating early social interactions in non-altricial species, analogous to studies of individual social recognition between mother and offspring during the early developmental phase in altricial species.

Finally, recent empirical evidence show that manipulating early social experiences in ZF larvae, such as raising larvae in social isolation, already leads to altered social avoidance patterns and atypical social interactions at larval stages, implicating social experiences in the developmental organization of social neural circuits rather than simple transient delays [119]. Conceptually, this mirrors findings from rodent models in which early maternal separation or reduced caregiver interactions during sensitive developmental windows produced persistent alterations in social behaviors and social information processing later in life (e.g., [120]). In both animal models, social experience modulates the developmental trajectory, shaping the emergence and plasticity of neural circuits underlying later social behavior: early larval social cohesion can be viewed as a functional analog of early caregiver–infant interactions, with translational value for modeling neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by altered social outcomes.

4. Conclusions

This work critically examines the translational value of the ZF model in developmental neuroscience and behavioral disorder research. Zebrafish offer major advantages over traditional mammalian models, including experimental tractability and ethical benefits, aligning with the 3Rs. However, they cannot fully replace mammals for studying early social and emotional development, as they lack mother–offspring bonds and associated neurodevelopmental processes like imprinting and reciprocal caregiving. We propose that early age-mate interactions in ZF, such as larval social cohesion, can serve as functional analogs to mother–infant bonding, providing novel behavioral domains for studying social deficits relevant to disorders like ASD. By integrating ethology and evolutionary perspectives, ZF research complements rather than replaces mammalian models, enabling investigation of early communication and natural sociality. Moreover, our attempt is to stimulate in behavioral scientists a reflection about which is the more appropriate fish model when approaching particular behavioral disorders. Based on (possibly phylogenetic) invariance among different vertebrate classes, in our case of fish (teleost) and mammals, we attempted a functional reconciliation in order to validate two fish models for early human emotional and cognitive responding. The combined adoption of teleost and mammalian models remains essential for comprehensively addressing research questions involving the complex interplay between developmental biology, early social behavior, and neurobehavioral disease. Only a comparative and phylogenetically informed approach can ensure full translational validity of the evidence obtained.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, A.R. and F.C.; Conceptualization, writing—review and editing, A.R., F.C., E.A. and D.S.; Supervision, E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive suggestions, which stimulated valuable reflection and contributed to the refinement of our work. The authors thank Antonio Maione and Stella Falsini for technical support and for help in selecting and retrieving references.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Russel, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique; Methuen: London, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, A. Sperimentazione animale e principio delle 3R. In Enciclopedia XXI Secolo; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana Treccani: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grunow, B.; Strauch, S.M. Status assessment and opportunities for improving fish welfare in animal experimental research according to the 3R-Guidelines. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 2023, 33, 1075–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S. Animal Suffering: The Science of Animal Welfare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, 276, 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, K.A.; Nagmoti, D.S.; Borkar, M.S.; Pannalal, H.K.; Bandaru, N. Review on Zebra fish as an alternative animal model for neurological studies. Adv. Biomark. Sci. Technol. 2025, 7, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militz, T.A.; Foale, S. The “Nemo Effect”: Perception and reality of Finding Nemo’s impact on marine aquarium fisheries. Fish Fish. 2017, 18, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, N.M.; Lim, S.M.; Vijayanathan, Y.; Lim, F.T.; Majeed, A.B.; Tan, M.P.; Ramasamy, K. Locomotor Assessment of 6-Hydroxydopamine-induced Adult Zebrafish-based Parkinson’s Disease Model. Jove—J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 178, e63355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.L.; Sousa, S.; Chapela, D.; van der Linde, H.C.; Willemsen, R.; Correia, A.D.; Outeiro, T.F.; Afonso, N.D. Identification of antiparkinsonian drugs in the 6-hydroxydopamine zebrafish model. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2020, 189, 172828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyn, M.; Ekker, M. Cerebroventricular Microinjections of MPTP on Adult Zebrafish Induces Dopaminergic Neuronal Death, Mitochondrial Fragmentation, and Sensorimotor Impairments. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 718244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.Y.; Jiang, X.; Paudel, Y.N.; Gao, X.; Gao, D.L.; Zhang, P.Y.; Sheng, W.L.; Shang, X.L.; Liu, K.C.; Zhang, X.J.; et al. Co-treatment with natural HMGB1 inhibitor Glycyrrhizin exerts neuroprotection and reverses Parkinson’s disease like pathology in Zebrafish. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 292, 115234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.R.; Gliksberg, M.; Varela, S.A.M.; Teles, M.; Wircer, E.; Blechman, J.; Petri, G.; Levkowitz, G.; Oliveira, R.F. Developmental Effects of Oxytocin Neurons on Social Affiliation and Processing of Social Information. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 8742–8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, T.; Seo, Y.; Park, H.C.; Choe, S.K.; Cha, S.H. Rotenone exposure causes features of Parkinsons disease pathology linked with muscle atrophy in developing zebrafish embryo. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiangiu, R.S.; Mihasan, M.; Gorgan, D.L.; Stache, B.A.; Hritcu, L. Anxiolytic, Promnesic, Anti-Acetylcholinesterase and Antioxidant Effects of Cotinine and 6-Hydroxy-L-Nicotine in Scopolamine-Induced Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Narang, R.K.; Singh, S. AlCl induced learning and memory deficit in zebrafish. Neurotoxicology 2022, 92, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raduan, S.Z.; Ahmed, Q.U.; Rusmili, M.R.A.; Sabere, A.S.M.; Haris, M.S.; Shaikh, M.F.; Mahmood, M.H. Neurotoxicity of aluminium chloride and okadaic acid in zebrafish: Unravelling Alzheimer’s disease model via learning and memory function evaluation. Neurol. Perspect. 2025, 5, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiprich, M.T.; Zanandrea, R.; Altenhofen, S.; Bonan, C.D. Influence of 3-nitropropionic acid on physiological and behavioral responses in zebrafish larvae and adults. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 234, 108772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiprich, M.T.; Vasques, R.D.; Gusso, D.; Ruebensam, G.; Kist, L.W.; Bogo, M.R.; Bonan, C.D. Locomotor Behavior and Memory Dysfunction Induced by 3-Nitropropionic Acid in Adult Zebrafish: Modulation of Dopaminergic Signaling. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasamma, S.; Audira, G.; Siregar, P.; Malhotra, N.; Lai, Y.H.; Liang, S.T.; Chen, J.R.; Chen, K.H.C.; Hsiao, C.D. Nanoplastics Cause Neurobehavioral Impairments, Reproductive and Oxidative Damages, and Biomarker Responses in Zebrafish: Throwing up Alarms of Wide Spread Health Risk of Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Samanta, P.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Cho, J.W.; Chun, H.S.; Yoon, S.; Kim, W.K. Developmental and Neurotoxicity of Acrylamide to Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.J.; Hu, J.; Liu, D.; Yin, J.; Chen, M.L.; Zhou, L.Q.; Yin, H.C. Cadmium chloride-induced transgenerational neurotoxicity in zebrafish development. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 81, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, M.; Savuca, A.; Ciobica, A.S.; Jijie, R.; Gurzu, I.L.; Hritcu, L.D.; Chelaru, I.A.; Plavan, G.I.; Nicoara, M.N.; Gurzu, B. The Neurobehavioral Impact of Zinc Chloride Exposure in Zebrafish: Evaluating Cognitive Deficits and Probiotic Modulation. Toxics 2025, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Li, C.Y.; Hu, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Jiang, Y.H.; Xu, X. CRISPR/Cas9-induced shank3b mutant zebrafish display autism-like behaviors. Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougnon, G.; Matsui, H. Behavioral and molecular insights into anxiety in and zebrafish models of autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.X.; Feng, T.S.; Lu, W.Q. The effects of valproic acid neurotoxicity on aggressive behavior in zebrafish autism model. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 275, 109783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmer, A.; Mirkes, K.; Anneser, L.; Eilers, T.; Kibat, C.; Mathuru, A.; Ryu, S.; Schuman, E. Oxytocin receptors influence the development and maintenance of social behavior in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landin, J.; Hovey, D.; Xu, B.; Lagman, D.; Zettergren, A.; Larhammar, D.; Kettunen, P.; Westberg, L. Oxytocin Receptors Regulate Social Preference in Zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, B.D.; Franscescon, F.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Norton, W.H.J.; Kalueff, A.V.; Parker, M.O. Zebrafish models for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 100, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlai, R. Zebrafish A newcomer with great promise in behavioral neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 144, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szychlinska, M.A.; Gammazza, A.M. The Zebrafish Model in Animal and Human Health Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodiya, R.; Sharma, P.; Israni, D.; Kamal, M.A.; Greig, N.H. Zebrafish-Based Parkinson’s Disease Models: Unveiling Genetic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Pathways. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets 2025, 24, 900–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadig, A.P.; Huwaimel, B.; Alobaida, A.; Khafagy, E.S.; Alotaibi, H.F.; Moin, A.; Krishna, K.L. Manganese chloride (MnCl2) induced novel model of Parkinson’s disease in adult Zebrafish; Involvement of oxidative stress, neuroinflamma-tion and apoptosis pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 155, 113697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.N.; Greene, J.G.; Miller, G.W. Behavioral phenotyping of mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2010, 211, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettiarachchi, P.; Niyangoda, S.S.; Jarosova, R.; Johnson, M.A. Dopamine Release Impairments Accompany Locomotor and Cognitive Deficiencies in Rotenone-Treated Parkinson?s Disease Model Zebrafish. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.L.; Liu, W.W.; Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Sima, Y.Z.; Zhong, Z.M.; Wang, H.; Hu, L.F.; Liu, C.F. Parkinson’s disease-like motor and non-motor symptoms in rotenone-treated zebrafish. Neurotoxicology 2017, 58, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlai, R. Learning and memory in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Method. Cell Biol. 2016, 134, 551–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reemst, K.; Shahin, H.; Shahar, O.D. Learning and memory formation in zebrafish: Protein dynamics and molecular tools. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1120984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, N.; Deshwal, S.; Rishi, V.; Singhal, N.K.; Sandhir, R. Zebrafish as a model organism to study sporadic Alzhei-mer’s disease: Behavioural, biochemical and histological validation. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 383, 115034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandino, I. Zebrafish Models in Toxicology and Disease Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Amora, M.; Giordani, S. The Utility of Zebrafish as a Model for Screening Developmental Neurotoxicity. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, K.B. Behavioural assessments of neurotoxic effects and neurodegeneration in zebrafish. Bba-Mol. Basis Dis. 2011, 1812, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, J.F. Nitazoxanide: A first-in-class broad-spectrum antiviral agent. Antivir. Res. 2014, 110, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, I.; Bhat, A. The impact of predators and vegetation on shoaling in wild zebrafish. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 240760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, D.S.; Price, B.C.; Ocasio, K.M.; Martins, E.P. Density and Group Size Influence Shoal Cohesion, but Not Coordination in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Comp. Psychol. 2015, 129, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, J.; Morgan, R.; Finnoen, M.H.; Dey, A.; Sarkar, K.; Jutfelt, F. On the Observation of Wild Zebrafish (Danio rerio) in India. Zebrafish 2019, 16, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, M.; Raja, M.; Vijayakumar, C.; Malaiammal, P.; Mayden, R.L. Natural History of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) in India. Zebrafish 2013, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlai, R. Social behavior of zebrafish: From synthetic images to biological mechanisms of shoaling. J. Neurosci. Methods 2014, 234, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, N.Y.; Gerlai, R. Shoaling in zebrafish: What we don’t know. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 22, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landeau, L.; Terborgh, J. Oddity and the Confusion Effect in Predation. Anim. Behav. 1986, 34, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, T.J. Heuristic Definitions of Fish Shoaling Behavior. Anim. Behav. 1983, 31, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeszer, R.E.; Alberici da Barbiano, L.; Ryan, M.J.; Parichy, D.M. Timing and plasticity of shoaling behaviour in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Anim. Behav. 2007, 74, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harpaz, R.; Nguyen, M.N.; Bahl, A.; Engert, F. Precise visuomotor transformations underlying collective behavior in larval zebrafish. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buske, C.; Gerlai, R. Shoaling develops with age in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Cann, L.I.; Matthews, J.J. The effects of lifelong isolation on species identification in zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio). Dev. Psychobiol. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Psychobiol. 1974, 7, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackroyd, E.J.; Heathcote, R.J.P.; Ioannou, C.C. Dynamic colour change in zebrafish (Danio rerio) across multiple contexts. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 241073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Sensory Integration: Cross-Modal Communication Between the Olfactory and Visual Systems in Zebrafish. Chem. Senses 2019, 44, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeszer, R.E.; Ryan, M.J.; Parichy, D.M. Learned social preference in zebrafish. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahabir, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Buske, C.; Gerlai, R. Maturation of shoaling in two zebrafish strains: A behavioral and neurochemical analysis. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 247, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, R.; Smith, C. The role of early learning in determining shoaling preferences based on visual cues in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Ethology 2007, 113, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcourt, J.; Poncin, P. Shoals and schools: Back to the heuristic definitions and quantitative references. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2012, 22, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Franks, B. Zebrafish welfare: Natural history, social motivation and behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 200, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.; Gerlai, R. From Schooling to Shoaling: Patterns of Collective Motion in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, R.; Gerlach, G.; Lawrence, C.; Smith, C. The behaviour and ecology of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Biol. Rev. 2008, 83, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.T.; O’Malley, D.M.; Melloni, R.H. Aggression and vasotocin are associated with dominant-subordinate relationships in zebrafish. Behav. Brain Res. 2006, 167, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parichy, D.M. Advancing biology through a deeper understanding of zebrafish ecology and evolution. eLife 2015, 4, e05635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundacker, A.; Rico, L.C.; Stoehrmann, P.; Tillmann, K.E.; Weber-Stadlbauer, U.; Pollak, D.D. Interaction of the pre- and postnatal environment in the maternal immune activation model. Discov. Ment. Health 2023, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Nakai, N.; Fujima, S.; Choe, K.Y.; Takumi, T. Social circuits and their dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3194–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.L.; Thurm, A.; Ethridge, S.B.; Soller, M.M.; Petkova, S.P.; Abel, T.; Bauman, M.D.; Brodkin, E.S.; Harony-Nicolas, H.; Wöhr, M.; et al. Reconsidering animal models used to study autism spectrum disorder: Current state and optimizing future. Genes Brain Behav. 2022, 21, e12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, F.A. The snark was a boojum. Am. Psychol. 1950, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropepe, V.; Sive, H.L. Can zebrafish be used as a model to study the neurodevelopmental causes of autism? Genes Brain Behav. 2003, 2, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Fang, Y.M.; Ma, J.H.; Wang, J.W.; Qu, L.K.; Yang, Q.S.; Wu, W.; Jin, L.B.; Sun, D. Advances in Zebrafish as a Comprehensive Model of Mental Disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2023, 2023, 6663141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washbourne, P. Can we model autism using zebrafish? Dev. Growth Differ. 2023, 65, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohr, M.; Scattoni, M.L. Behavioural methods used in rodent models of autism spectrum disorders: Current standards and new developments. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 251, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchi, I.; Santucci, D.; Alleva, E. Ultrasonic vocalisation emitted by infant rodents: A tool for assessment of neurobehavioural development. Behav. Brain Res. 2001, 125, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scattoni, M.L.; Gandhy, S.U.; Ricceri, L.; Crawley, J.N. Unusual Repertoire of Vocalizations in the BTBR T plus tf/J Mouse Model of Autism. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branchi, I.; Santucci, D.; Vitale, A.; Alleva, E. Ultrasonic vocalizations by infant laboratory mice: A preliminary spectrographic characterization under different conditions. Dev. Psychobiol. 1998, 33, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, F.; Berry, A.; Alleva, E. Early disruption of plasticity the mother-infant relationship: Effects on brain and implications for psychopathology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2003, 27, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, S.; Yuvarani, M.S.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Alterations in the ultrasonic vocalization sequences in pups of an autism spectrum disorder mouse model: A longitudinal study over age and sex. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 139, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.; Khan, A.; Gerlai, R. Early social deprivation does not affect cortisol response to acute and chronic stress in zebrafish. Stress 2021, 24, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Lei, L.; Tian, L.J.; Hou, F.; Roper, C.; Ge, X.Q.; Zhao, Y.X.; Chen, Y.H.; Dong, Q.X.; Tanguay, R.L.; et al. Developmental and behavioral alterations in zebrafish embryonically exposed to valproic acid (VPA): An aquatic model for autism. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2018, 66, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groneberg, A.H.; Marques, J.C.; Martins, A.L.; del Corral, R.D.; de Polavieja, G.G.; Orger, M.B. Early-Life Social Experience Shapes Social Avoidance Reactions in Larval Zebrafish. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 4009–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshine-Earn, S.; Earn, D.J.D. On the evolutionary pathway of parental care in mouth-brooding cichlid fish. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 2217–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacke, M.A.; Thünken, T. Juveniles of a biparental cichlid fish compensate lack of parental protection by improved shoaling performance. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2024, 78, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntti, S.A. Cichlid fishes. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 1755–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thünken, T.; Diederich, J.; Vitt, S.; Aytaç, R. Genetic Relatedness Promotes Equal Contributions of Males and Females to Brood Care in a Biparental Cichlid Fish. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e72570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klett, V.; Meyer, A. What, if anything, is a Tilapia?—Mitochondrial ND2 phylogeny of tilapiines and the evolution of parental care systems in the African cichlid fishes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002, 19, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenleyside, M.H.A. Parental Care Patterns of Fishes. Am. Nat. 1981, 117, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zworykin, D.D.; Budaev, S.V. Parental brood provisioning as a component of parental care in neotropical cichlid fishes (Perciformes: Cichlidae). J. Ichthyol. 2000, 40, S271. [Google Scholar]

- Balon, E.K. Probable evolution of the coelacanth’s reproductive style: Lecithotrophy and orally feeding embryos in cichlid fishes and in Latimeria chalumnae. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1991, 32, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Patterson, E.M. Tool use by aquatic animals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefc, K.M. Mating and parental care in Lake Tanganyika’s cichlids. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 2011, 470875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.; Maunder, R.J.; Foey, A.; Pearce, J.; Val, A.L.; Sloman, K.A. Biparental mucus feeding: A unique example of parental care in an Amazonian cichlid. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 3787–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller-Costa, T.; Canario, A.V.M.; Hubbard, P.C. Chemical communication in cichlids: A mini-review. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2015, 221, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlisle, T.R. Parental Response to Brood Size in a Cichlid Fish. Anim. Behav. 1985, 33, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longrie, N.; Poncin, P.; Denoël, M.; Gennotte, V.; Delcourt, J.; Parmentier, E. Behaviours Associated with Acoustic Communication in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchi, I.; Santucci, D.; Alleva, E. Analysis of ultrasonic vocalizations emitted by infant rodents. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2006, 30, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scattoni, M.L.; Michetti, C.; Ricceri, L. Rodent vocalization studies in animal models of the autism spectrum disorder. In Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 25, pp. 445–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.C.; Wen, B.; Liang, H.; Gao, J.Z.; Chen, Z.Z. Sex-Dependent Lipid Profile Differences in Skin Mucus between Non-Parental and Parental Discus Fish Determined by Lipidomics. Fishes 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Robles, A.; Nicolaou, C.; Smaers, J.B.; Sherwood, C.C. The evolution of human altriciality and brain development in comparative context. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, V.; Talbot, J.; Plamondon, H. Exploring rodent prosociality: A conceptual framework. Transl. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 20250375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corridi, P.; Alleva, E. Individual discrimination by olfactory cues in mice (Mus musculus): A multiple choice confirmation. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 1994, 7, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corridi, P.; Chiarotti, F.; Bigi, S.; Alleva, E. Familiarity with Conspecific Odor and Isolation-Induced Aggressive-Behavior in Male-Mice (Mus-Domesticus). J. Comp. Psychol. 1993, 107, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K. The Foundations of Ethology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, L.S.; Wessling, E.G.; Kano, F.; Stevens, J.M.G.; Call, J.; Krupenye, C. Bonobos and chimpanzees remember familiar conspecifics for decades. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2304903120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1982, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, P. Sexual imprinting and optimal outbreeding. Nature 1978, 273, 659–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinz, R.C.; de Polavieja, G.G. Ontogeny of collective behavior reveals a simple attraction rule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2295–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney, W.T.; Ellwood, C.; Davis, J.P.; Reddon, A.R. Familiarity preferences in zebrafish (Danio rerio) depend on shoal proximity. J. Fish Biol. 2025, 107, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney, W.T.; Jose, A.; Hirons-Major, C.; Reddon, A.R. Decision-making in shoaling: Zebrafish integrate cues of familiarity and group size. Anim. Cogn. 2025, 28, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stednitz, S.J.; Lesak, A.; Fecker, A.L.; Painter, P.; Washbourne, P.; Mazzucato, L.; Scott, E.K. Coordinated social interaction states revealed by probabilistic modeling of zebrafish behavior. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 2903–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.L.; Song, E.; Nikitchenko, M.; Herrera, K.J.; Wong, S.; Engert, F.; Kunes, S. Social isolation modulates appetite and avoidance behavior via a common oxytocinergic circuit in larval zebrafish. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, A.; Zelli, S.; Leo, D.; Carbone, C.; Mus, L.; Illiano, P.; Alleva, E.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Adriani, W. Behavioral characterization of DAT-KO rats and evidence of asocial-like phenotypes in DAT-HET rats: The potential involvement of norepinephrine system. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 359, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrick, A.; Jimenez, D.; Jacquez, B.; Sun, M.S.; Noor, S.; Milligan, E.D.; Valenzuela, C.F.; Linsenbardt, D.N. Maternal alcohol drinking patterns predict offspring neurobehavioral outcomes. Neuropharmacology 2024, 257, 110044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleva, E.; Rankin, J.; Santucci, D. Neurobehavioral alteration in rodents following developmental exposure to aluminum. Toxicol. Ind. Health 1998, 14, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, F.; Meyer, A. The Evolutionary Genomics of Cichlid Fishes: Explosive Speciation and Adaptation in the Postgenomic Era. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2014, 15, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seay, B.; Hansen, E.; Harlow, H.F. Mother-infant separation in monkeys. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1962, 3, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, G.; Hodgins-Davis, A.; Avolio, C.; Schunter, C. Kin recognition in zebrafish: A 24-hour window for olfactory imprinting. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2008, 275, 2165–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stednitz, S.J.; Washbourne, P. Rapid Progressive Social Development of Zebrafish. Zebrafish 2020, 17, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreosti, E.; Lopes, G.; Kampff, A.R.; Wilson, S.W. Development of social behavior in young zebrafish. Front. Neural Circuits 2015, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnie, M.T.; Baram, T.Z. The evolving neurobiology of early-life stress. Neuron 2025, 113, 1474–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.