Abstract

The global proliferation of plastics and their degradation into microplastics (<5 mm) have created a pervasive environmental crisis with severe ecological and human health consequences. Despite the exponential growth in microplastic research over the past decade, standardized protocols are still lacking. The absence of consistent sampling, analysis, and reporting methods limits data comparability, interoperability, and harmonization across studies. This study conducted a systematic bibliographic review of 355 peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2022 that investigated microplastics in freshwater as well as marine water and sediment environments. The goal was to evaluate methodological consistency, sampling instruments, measurement units, reported characteristics, and data-sharing practices to identify pathways toward harmonized and FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) microplastic data. Results show that 80.6% of studies focused on marine environments, 18% on freshwater, and 1.4% on both. This highlights persistent data gaps in freshwater systems, which function as key transport pathways for plastics to the ocean. Most studies targeted water (59%) rather than sediment (41%) and were mostly based on single-time sampling, limiting long-term analyses. Surface layers (<1 m) were predominantly sampled, while deeper layers remain understudied. Nets, particularly Manta, neuston, and plankton nets were the dominant tools for water sampling, whereas grabs, corers, and metallic receptacles were used for sediments. However, variations in mesh size and sampling depth introduce substantial biases in particle size recovery and reduce comparability across studies. The most common units were counts/volume for water and counts/g dry weight for sediments, but more than ten unit expressions were identified, complicating conversions. Only 35% of studies reported all four key microplastic characteristics (color, polymer type, shape, and size), and less than 20% made datasets publicly available. To advance harmonization, we recommend the adoption of consistent measurement units, mandatory reporting of key metadata, and wider implementation of open data practices aligned with the FAIR principles. These insights provide a foundation for developing robust monitoring strategies and evidence-based management frameworks. This is especially important for freshwater systems, where data remain scarce, and policy intervention is urgently needed.

1. Introduction

The increased use of plastics has created an environmental menace, with global costs running into several billion US dollars annually [1,2,3,4,5]. Further breakdown of plastics into microplastics (<5 mm) has aggravated this pollution problem with severe negative impacts on the environment, aquatic systems, the organisms therein, and human health [6,7,8,9]. Microplastics can cause physiological stress, reproductive failure, and mortality in aquatic organisms [10,11,12,13]. Moreover, microplastics have been linked to cellular damage and developmental effects in humans [9,14].

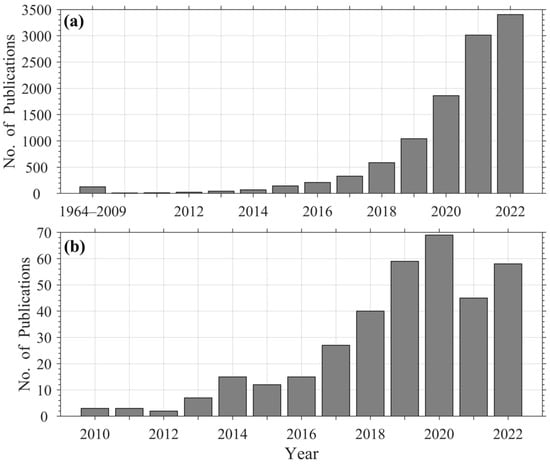

The growing awareness of these risks has driven a rapid surge in microplastic research. A search of environmental microplastic studies in the Web of Science (WoS) database (described further in the methods section) reveals 10,883 publications between 1964 and 2022, with ~76% (8278 articles) published during 2020–2022 alone (Figure 1a). Although this expansion reflects strong global interest, the diversity of sampling designs, measurement units, and reporting conventions across studies limits data comparability and integration. This in turn hinders meta-analyses, large-scale modeling, and the development of consistent regulatory frameworks [15,16,17].

Figure 1.

Number of microplastic publications in the Web of Science (WoS) database (a) between 1964 and 2022, and (b) random subset selected between 2010 and 2022 for data extraction.

Studies of microplastics have occurred in several environmental settings, or compartments, including the atmosphere, terrestrial waters, sediments, beaches, biota, and oceans, producing vast but fragmented datasets [18,19,20,21]. Several initiatives, such as the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) global marine microplastics database (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/microplastics, accessed on 15 August 2025; [22]), the European Union EMODnet (European Marine Observation and Data Network) marine litter database (https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/chemistry, accessed on 15 August 2025; [23]), the German Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research LITTERBASE (https://litterbase.awi.de/, accessed on 15 August 2025; [24]), and the Ministry of Environment Japan Atlas of Ocean Microplastics (https://aomi.env.go.jp/, accessed on 15 August 2025; [25]) aim to consolidate these data. However, inconsistencies in sampling protocols and reporting units (e.g., items/m3 vs. items/km2 or items/g) constrain their interoperability and limit the potential for large-scale syntheses. Similar methodological heterogeneity has also been documented in terrestrial systems, where differences in experimental design and measurement protocols hinder meaningful cross-study comparisons [26].

Data harmonization, defined as the aggregation of information from different sources into a consistent, unified dataset [27,28,29], is therefore essential to fully leverage existing research. Inconsistent metadata, mismatched measurement units, and partial reporting of particle characteristics remain major barriers to building coherent databases.

Drawing from our experience with NOAA NCEI’s microplastic database and collaborations with other data repositories, we identify persistent challenges to harmonization, including inconsistent sampling and analytical methods, non-uniform measurement units, and limited adherence to FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles [30]. The development of the aforementioned databases hinges heavily on FAIR data. The FAIR data principles require that data should be made publicly available. It should also include a clear data usage license. In addition, the data must have rich metadata that explains how, when, and where it was collected. The metadata should also describe how the data was processed, quality-controlled, and reported [30]. Despite broad endorsement of FAIR principles, actual implementation remains inconsistent, especially regarding metadata completeness and machine-readability of shared datasets.

Previous reviews have examined aspects of these issues (e.g., [22,31,32,33,34,35]), but few have systematically assessed how methodological heterogeneity affects harmonization across both freshwater and marine systems.

In this study, we review 355 peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2022 that investigated microplastics in freshwater as well as marine water and sediment environments. We evaluate methodological consistency, sampling instruments, measurement units, reported characteristics, and data-sharing practices to identify pathways toward harmonized and FAIR microplastic data. By highlighting cross-study discrepancies and shared practices, this work provides a foundation for improving data integration and advancing global monitoring and policy frameworks.

2. Methods

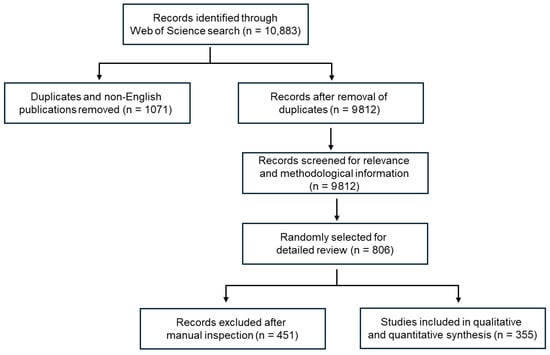

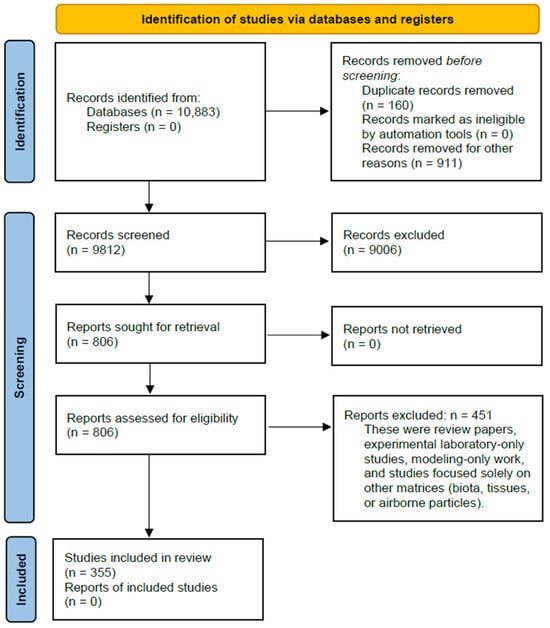

Our methods followed similar approaches used by [36,37,38]. This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [39]. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram is presented in Figure 2, and the completed PRISMA checklist is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the literature screening and selection process for the 355 studies included in this review.

A comprehensive literature search was performed in January 2023 using the WoS database. No additional databases were searched. The WoS query used was: ALL FIELDS = (“microplastic” OR “microplastics”), refined to Document Type = Article and Language = English. The search resulted in 10,883 records published between 1964 and 2022 (Figure 1a).

To derive a representative and manageable dataset suitable for detailed methodological assessment, a random sampling procedure was applied to the initial set, yielding 806 articles. Each article was screened manually to ensure relevance and adequate methodological information. Titles/abstracts and full texts were screened manually by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and/or a third reviewer. No automation tools were used for screening. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 2), 355 studies were retained for data extraction, while 451 publications were excluded. Excluded materials included review papers, experimental laboratory-only studies, modeling-only work, and studies focused solely on other matrices such as biota, tissues, or airborne particles. The final dataset therefore represents studies that directly sampled microplastics from freshwater, marine, or beach water and sediment compartments, providing sufficient methodological detail for comparative analysis.

The selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2), which details the number of studies screened, excluded, and retained at each stage.

To ensure consistency in data extraction, all personnel were trained and given the same set of papers for independent extraction as practice. The trial extractions were examined for consistency, and further training was provided where needed until consistency among personnel was achieved before embarking on the actual data extraction. Data for each article were extracted by one reviewer using a standardized extraction template. Extraction was not duplicated. We did not contact study authors for missing information; values not reported in the article were recorded as missing.

When available, the following metadata were extracted from each article: year of publication, environmental setting (i.e., freshwater or marine), study location (including latitude and longitude), record type (i.e., water or sediment), record depth, sample thickness (for sediments), study dates, study duration, sampling frequency, number of records collected, sampling instrument, microplastic sizes, units of microplastic abundance/concentration, microplastic characteristics (i.e., color, polymer type, shape, and size), and data accessibility (e.g., dataset links).

For our purposes, we considered sampling effort as the length of time over which sampling occurred. It denotes whether the study includes measurements over time (i.e., at least two times) at a given location (i.e., the same location was sampled more than once), or whether they correspond to just one sampling time at a given location. On the other hand, we considered study frequency as the sampling frequency for studies that collected measurements over time at a given location, which may be regular (e.g., monthly data collection in a one year-long study) or irregular (e.g., five sampling times at different intervals over a 3-month long study). This distinction between sampling effort and frequency was necessary to assess both temporal extent and temporal resolution across studies.

For our study, sampling depth for the water compartment represents the depth within the water column at which samples were collected, whereas for sediments, it denotes the depth of the sampled sediment layer.

We did not perform formal risk-of-bias, reporting-bias, or certainty-of-evidence assessments because the objective of this review was to characterize reporting practices and methodological heterogeneity rather than to estimate effect sizes or causal impacts. Accordingly, no effect measures were calculated. Extracted variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (counts and percentages), overall and stratified by environment (freshwater vs. marine) and compartment (water vs. sediment). Records with missing fields were retained and reported as missing for the relevant variable. All analyses and figures were produced using Excel and MATLAB.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sampling Locations and Environments

The 355 peer-reviewed articles found to be suitable for our purposes were published between 2010 and 2022, of which 75% occurred in the last five years (Figure 1b). These articles fell within the era of rapid growth in the microplastic research area (Figure 1a) and offered a good perspective on the current state of the science.

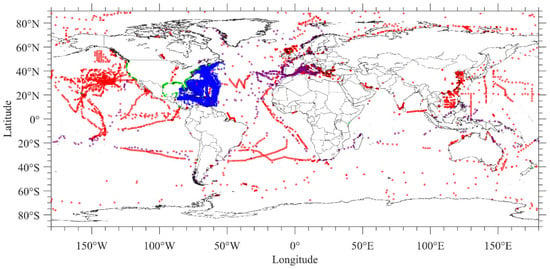

The number of sampling locations per study ranged from 1 to 4976. Studies occurred in all ocean basins and continents in the world (Figure 3). Studies with the most sampling points included [40] (4976 sampling points), [41] (2121 sampling points) and [42] (804 sampling points). Some studies did not include exact latitude and longitude for all sampling locations and reported only general study areas.

Figure 3.

Locations where microplastic data was collected from the 355 selected studies. Sampling points for [40] are shown in blue dots, [41] in green dots and [42] in purple dots. Sampling points from all other studies are shown in red dots.

Most of the studies examined marine environments (~81%), which includes estuaries, beaches, seawater and sea sediments, while only ~18% occurred in freshwater environments (Table 1). This imbalance reflects a structural research bias driven by the presence of international marine monitoring programs, easier coordination of vessel-based sampling campaigns, and funding mechanisms that prioritize ocean plastics. Less than 2% of the articles surveyed both freshwater and marine environments in the same study (Table 1). It has been reported that most of the microplastics in the marine environments originate from terrestrial sources and are carried into the coastal zones and oceans mostly by terrestrial water bodies [3,8,43,44]. Given this, the underrepresentation of freshwater environments highlights a gap in capturing early transport processes before plastics reach marine systems.

Table 1.

Environmental settings and compartments of studies.

Generally, more studies focused on water (59%) than sediment (41%), even though sediments are a primary sink for pollutants including microplastics [45,46,47]. This suggests a preference for sampling more accessible surface environments over benthic systems, even though sediments may provide longer-term pollution records. Most aquatic studies occurred in the surface layer likely due to its more advanced and established sampling technique [48]. Surface-focused methods such as net trawls are also easier to standardize internationally, which may have contributed to their widespread adoption.

Table 1 shows the preference to study the water compartment within each environmental setting. Forty-two percent of freshwater studies and 52% of marine studies focused exclusively on the water compartment. Conversely, simultaneous studies of both water and sediment compartments accounted for 31% in freshwater and only 11% in marine water. Such limited cross-compartment sampling reduces the ability to interpret vertical transport and retention processes within ecosystems.

3.2. Sampling Efforts, Sampling Frequency and Number of Samples

Sampling efforts and temporal information are important metrics for microplastic data comparison and harmonization, as it helps to geolocate data in space and time. In addition, it enhances the value and usability of the microplastic data. For example, environmental information such as winds, currents, and water level from satellites or nearby in situ measurements can be overlaid on previously collected microplastic data for additional interpretation of the microplastic abundance, distribution, and variability. This information can also be added into models to perform microplastic trajectory tracking [49]. However, these integrations are only meaningful when datasets include temporal replication rather than isolated sampling events.

Temporal coverages of the studies were obtained from sampling start and/or end dates provided in the articles. Twenty-six of the 355 analyzed articles (7.3%) did not contain sampling date information. Among the articles that included sampling date information, about half (n = 180; 50.7%) provided year and month/season, 38.6% (n = 137) provided year, month and day, while 3.4% (n = 12) provided only the year. Date information that includes year, month, and day is the most useful for harmonization because it allows alignment with other studies as well as hydrological or meteorological records. Incomplete temporal metadata reduces long-term comparability and limits alignment with external hydrological or meteorological datasets, particularly when attempting retrospective harmonization within global repositories.

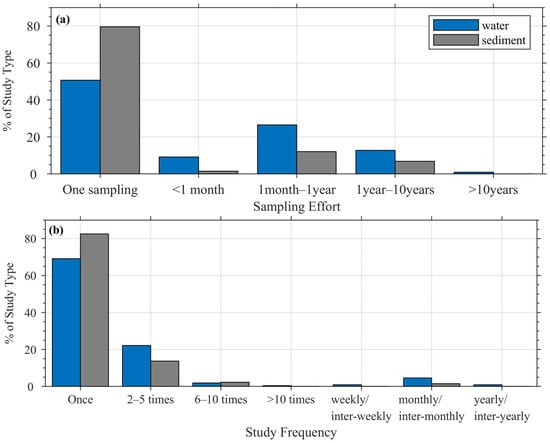

Water-based studies generally demonstrated greater temporal coverage than sediment studies. About half of water studies included repeated sampling, compared to only one-fifth for sediments (see Figure 4a). However, most datasets remain temporally limited: nearly 70% of water studies and 82% of sediment studies were one-time collections. Only a few studies (<2%) extended beyond a year, indicating that most microplastic studies are designed as spatial surveys rather than time-series monitoring efforts.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of (a) sampling effort, and (b) study frequency in water and sediment studies.

Repeated microplastic sampling at a given location is essential to gain insights into changes over time. This helps identify factors contributing to microplastic variability in the environment and assess the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. Seasonal variations such as rainfall, storms, and dry periods significantly influence microplastic abundance. Heavy rainfall and storm events enhance surface runoff and river discharge, transporting large quantities of land-based plastics and microplastics into aquatic systems. On the contrary, dry periods often lead to reduced fluxes but increased accumulation in sediments and shorelines [50,51]. Consequently, temporal sampling that spans different hydrological seasons is critical for accurately capturing the variability and transport pathways of microplastics. Without seasonally distributed sampling points, peak transport events and depositional episodes may be overlooked, which biases annual load estimates derived from single-time sampling.

Most of the microplastic studies we examined were one-time investigations (69% and 82.4% for water and sediment, respectively) with only 31% (17.6%) of water (sediment) studies being repeated (Figure 4b). About 22.1% and 13.7% of water and sediment studies, respectively, were repeated between two to five times, while 4.6% and 1.5% of water and sediment studies, respectively, were regularly sampled at monthly or inter-monthly intervals. Only 0.9% of water studies and no sediment studies sampled yearly or inter-yearly. This limited temporal depth makes it difficult to integrate these datasets into long-term observational programs or to detect directional trends over time.

Large-scale efforts such as the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER; [52]) network and the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) provide frameworks that could incorporate standardized microplastic protocols, enabling consistent temporal coverage across regions. In parallel, citizen science initiatives are emerging as valuable contributors to long-term datasets. Examples include The Ocean Race (formerly Volvo Ocean Race), Adventure Scientists, Surfing for Science, Oceaneye Association, Nurdle Patrol, and the Sail & Explore Association [22]. These organizations mobilize trained volunteers, sailors, and ocean enthusiasts to collect microplastic samples during expeditions, races, and recreational activities. For instance, the Ocean Race program used yachts such as Turn the Tide on Plastic and AkzoNobel to gather near-global surface microplastic data during their circumnavigation [53]. Oceaneye, a non-profit based in Geneva, operates a fleet of 16 volunteer sailboats that collect and analyze samples in their laboratory [42], contributing data to the NOAA NCEI Marine Microplastics Database. Similarly, the Sail & Explore Association conducts global sailing expeditions focusing on microplastics smaller than 0.3 mm [54], and Adventure Scientists engages outdoor enthusiasts to obtain samples from otherwise inaccessible locations [55]. The Nurdle Patrol initiative, coordinated by the Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve, enlists volunteers to monitor nurdle abundance globally [41]. These distributed data collection networks highlight how non-institutional platforms can improve temporal continuity, especially where formal monitoring programs are absent.

The number of microplastic samples that are collected during a study depend on factors such as the study objectives, methods (instruments), sampling strategies, and environmental settings and compartments [19,56,57]. It is important to consider the number of samples to be collected a priori as the quantity of samples collected can influence the representativeness of the results obtained for the study [19,58,59].

Overall, more water samples were collected per study than sediment samples (Table 2). About 34% and 42% of water and sediment studies, respectively, collected 20 samples or less while about 25% of water and sediment studies collected between 20 and 40 microplastic samples. Fewer studies, 13% (water) and 7% (sediment), collected over 100 samples per study (Table 2). This variation in sampling resolution introduces unequal statistical robustness across studies and should be considered when integrating datasets into harmonized databases.

Table 2.

Number of water and sediment samples collected per study.

3.3. Sampling Depth

The depth distribution of a microplastic particle is affected by both its properties (e.g., chemical composition, size, shape, and density) and the environment (e.g., water density, winds, and currents), which together determine the quality and quantity of microplastic data collected [19,46,60]. The depth at which microplastic data are collected can also indicate residence time in the system. In sediment environments, depth profiles may support chronological interpretation of deposition. Since harmonization efforts rely on comparing datasets collected under comparable environmental contexts, explicit reporting of sampling depth is essential for comparability rather than for descriptive completeness alone.

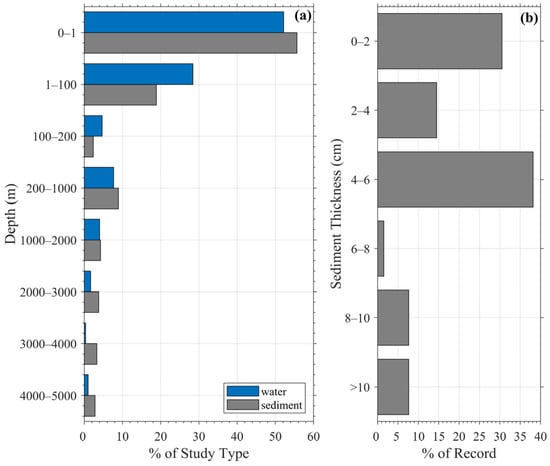

Fifty-two percent of water samples were collected in the surface, pelagic zone (<1 m), while 28% were collected between 1 and 100 m (Figure 5a). Only about 20% of water studies extended sampling below 100 m, indicating a strong surface bias driven by the dominance of net-based surface trawling. This reflects both logistical convenience and a historical focus on floating debris, but it also leads to underrepresentation of subsurface and deepwater microplastics, which are increasingly recognized as important sinks. As a result, many existing datasets provide only a surface snapshot rather than a depth-resolved concentration profile.

Figure 5.

(a) Depth where microplastic samples were collected. (b) Thickness of sediment where microplastic samples were taken.

The sediment compartment includes riverbank, riverbed, beach, and seabed settings; thus, data are collected on or within sediment layers. Approximately 56% of sediment samples were retrieved from the upper 1 m, and an additional 19% from the 1–100 m layer (Figure 5a). Ultimately, microplastics in the water column sink and settle into sediments over time [61,62], with the top 5 cm layer consistently identified as holding the highest concentration due to recent deposition [46,47]. This aligns with our finding that at least 83% of studies sampled only the upper 6 cm of sediment, and about 15% extended to a depth of 8 cm. This pattern suggests an implicit assumption that surface sediment alone is sufficient to capture accumulation trends, but it also limits the ability to detect historical pollution layers.

There was no clear distinction between sediment thickness sampled in freshwater versus marine settings. Sediment in deeper ocean zones (>2000 m) was sampled by only 10% of studies. This is understandable given that sampling at these depths is logistically intensive and requires specialized equipment and vessel access [19,32,63]. However, this creates a structural geographic and bathymetric bias in the global dataset, skewing our understanding toward shallow coastal and shelf regions. This bias should be acknowledged explicitly when aggregating records for global assessments or model validation.

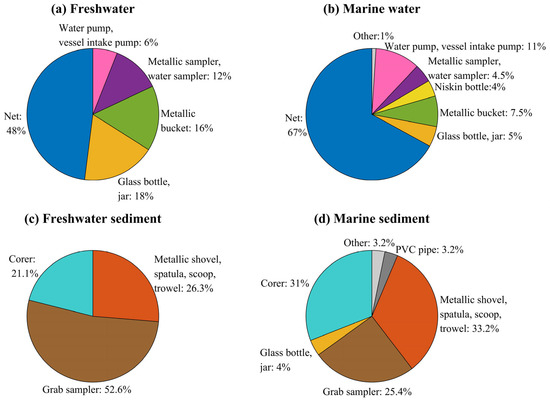

3.4. Sampling Instruments

The types and sizes of microplastic collected in an environmental setting depend largely on the sampling instrument used [19,64,65,66]. In this section, we examine how microplastic data are collected in water and sediment compartments. Nets were the most common instrument for surface-water sampling in freshwater (n = 24; 48%; Figure 6a) and especially in marine waters (n = 134; 67%; Figure 6b). Nets used in these studies include Bongo, drift, Manta, multiple opening and closing, neuston, and plankton nets. Of these, Manta (n = 71), neuston (n = 42), and plankton (n = 30) nets accounted for nearly all reported net deployments. Glass bottles, metallic buckets, metallic samplers, and water samplers were more frequently used in freshwater sampling than in marine environments. The use of pumps was almost twice as common in marine sampling (11%) compared to freshwater sampling (6%). This contrast in choice of instrument likely reflects the available research infrastructure as much as it reflects methodological preference. Marine programs often operate from research vessels that are already equipped for net-based transects. In contrast, freshwater campaigns are typically more ad hoc and resource-limited, which shapes their instrument selection.

Figure 6.

A summary of instruments used to collect microplastic samples in (a) freshwater, (b) marine water, (c) freshwater sediment, and (d) marine sediment compartments.

Sediment collection was mainly carried out using corers, grab samplers (e.g., Van Veen, Ekman, Peterson and Ponar grabs) or metallic receptacles such as shovels, spatulas, scoops, or trowels (Figure 6c,d). In freshwater settings, about half of the sediment samples were collected with grab samplers, while in marine settings, metallic receptacles dominated, particularly for littoral and beach environments. In deeper marine areas, corers and grab samplers were commonly used. These patterns indicate that sediment sampling often follows accessibility rather than harmonized objectives. As a result, easily reachable coastal zones are overrepresented, while deeper or upstream depositional environments receive comparatively less attention.

Sampling instruments broadly fall into two methodological categories: areal sampling (mainly nets), and point/station sampling (e.g., bottles, buckets, pumps, grabs, and corers). Due to the heterogeneous distribution of microplastics [16,67], nets provide wide spatial coverage over tow transects, but clogging during deployment can reduce sampling efficiency. Anderson et al. [68] and ref. [33] suggested using multiple nets with different mesh sizes in tandem to avoid clogging and reduce particle loss. A major limitation of net-based sampling is that large mesh sizes (typically 300 µm and above) prevent capture of smaller microplastics and certain shapes such as fibers, which leads to underrepresentation of finer fractions [65,69,70]. Fibers, depending on their orientation, may slip through net meshes, making point or grab sampling more suitable for capturing this morphology consistently across studies [71]. This systematic bias toward larger, floating particles means that many surface datasets are not directly comparable to sediment or riverine datasets that use finer filtration steps.

Kang et al. [72] illustrated how sampling method influences reported abundance. They retrieved 21–15,560 particles m−3 using a 50 μm hand net compared to just 0.62–860 particles m−3 using a 330 μm Manta trawl at the same site. This demonstrates that methodological choice alone can produce order-of-magnitude differences in reported concentration. Without explicit reporting of mesh size and deployment parameters, two studies that appear comparable based on units alone may, in fact, be sampling fundamentally different fractions of the particle size spectrum.

Point sampling approaches, while less spatially extensive and less laborious, can utilize finer mesh or filter paper to capture smaller microplastic particles. Barrows et al. [69] reported that grab sampling collected over three orders of magnitude more microplastics per unit volume than neuston net sampling. However, point sampling captures only a small discrete volume and may miss spatial heterogeneity. This reinforces that neither approach is inherently superior; harmonization efforts should encourage hybrid or dual-method strategies to balance detection sensitivity and spatial representation.

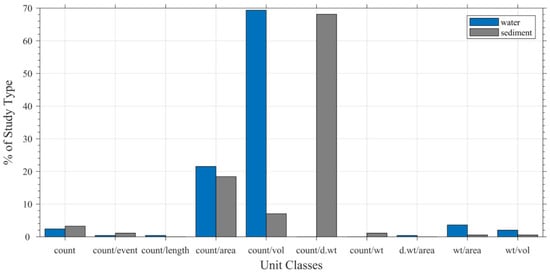

3.5. Measurement Units

A standard unit of measurement in microplastics reporting is important for data harmonization and comparability across studies. In scientific reporting, a standard of measurement refers to a mechanism used to quantify an attribute, producing numerical information that is assigned a defined unit to ensure reproducibility and comparability [73,74,75,76]. The unit of measurement is expected to be clearly defined, accurate, consistent, internationally acceptable, and easily replicated [77,78,79,80]. At present, the microplastic research area is still evolving, and no globally defined uniform standards or units of measurements exist for microplastic data reporting. This lack of standardization introduces inconsistencies that propagate into large-scale databases and complicate cross-study syntheses.

The studies examined in this work reported a wide range of measurement units, grouped into major classes such as count, count per volume, count per area, count per weight, and weight per volume (Table 3). Among these, count per volume dominated for water samples (69.3%) and count per dry weight for sediment samples (68.1%; Figure 7). These units provide the most meaningful representation of microplastic abundance within their respective environments because they account for sample volume or mass and allow comparison across studies when properly reported. However, we observed high variability even within single unit classes—for example, multiple expressions of area-based units (items/km2 vs. items/m2) or wet versus dry weight normalization—which reduces interoperability.

Table 3.

Unit classes and types used in articles examined. (d.w. is dry weight).

Figure 7.

Comparison of microplastic unit classes between water and sediment studies. See Table 3 for definition of classes.

Ideally, measurements within each compartment would be normalized to items/m3 for water and items/g dry weight for sediments to facilitate data interoperability. In practice, conversion is only possible when supporting metadata are available. For instance, surface water values reported as items/km2 can only be converted to items/m3 if sampling depth or net submergence information is provided. For example, if a study reports 1000 items/km2 and the effective sampling depth is 0.5 m, the equivalent volumetric concentration can be derived as:

1000 items/(1,000,000 m2 × 0.5 m) = 1000 items/500,000 m3 = 0.002 items/m3

Without that depth information, however, no valid conversion can be made. Likewise, sediment concentration values expressed as items/g wet weight cannot be translated into items/g dry weight without information on moisture content or a conversion factor. This demonstrates that even when unit classes appear theoretically convertible, missing metadata often prevents legitimate recalculation, limiting integration into harmonized databases.

For water samples, volumetric units (items/m3) provide the most physically consistent basis for quantifying abundance in three-dimensional space. The sampled volume can be determined directly from the internal dimensions of equipment such as bottles, pumps, grab samplers, or corers. For beach sand and other sediments collected with receptacles like a shovel, spatula, or scoop, the sample volume equals the product of the sampling area’s length, width, and depth. Such direct-volume approaches are straightforward but were inconsistently documented across studies, limiting reproducibility. In many cases, the sampling geometry was implied rather than explicitly stated, which leaves ambiguity when downstream users attempt to interpret or reprocess reported concentrations.

For net-based sampling, volume is typically estimated as the product of the net opening width, tow distance, and immersion depth. The latter parameter is particularly prone to variability. Many studies assume half the net-frame height for neuston tow configurations [81,82] or full frame height for manta nets [67,82], but few explicitly state this assumption. Even when flowmeters or volumeters are attached, fluctuations due to wave and vessel motion may affect immersion depth, making volumetric estimates inconsistent across studies. These variations mean that two datasets expressed in items/m3 may not represent equivalent sampling volumes, which complicates attempts at direct comparison.

For sediments, concentrations expressed per dry weight (items/g d.w.) reduce variability due to moisture content and are more stable for comparison [19,83]. Count per area was the second most common unit class (21.5% for water and 18.4% for sediments), and while these may be convertible to volumetric or mass-normalized values, conversion is only robust when sampling depth, core thickness, or bulk density data are available. In many studies, however, these details were missing or ambiguously reported, preventing reliable conversion. This pattern suggests that even when publications report concentration values, the omission of contextual metadata effectively limits their harmonization potential.

Other unit classes, such as weight per area and weight per volume (<4% of reports), are useful for mass load estimation. However, they obscure particle count and size distribution which are critical for ecological and toxicological interpretation [16,48,60]. Some studies addressed this by reporting both count and weight metrics (e.g., [42,60,67,84]), providing flexibility for downstream integration. Still, these dual reports were not common enough to establish a consistent reporting standard, and most datasets remain locked into single-unit expressions without conversion context.

A few studies reported abundance using non-normalized expressions such as number of items or items/tow or items/zone. These units lack spatial or volumetric context and cannot be quantitatively compared across studies, highlighting that incomplete normalization is functionally equivalent to data loss when assembling harmonized repositories.

3.6. Characteristics of Microplastics

Microplastics are characterized by polymer type, shape, color and size [12,85]. These attributes provide insight into sources, degradation processes, and potential ecological and toxicological impacts [86,87,88]. Common polymer types include high density polyethylene (HDPE), low density polyethylene (LDPE), polyamide (PA; nylon), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [19,86,89].

Confirmation of polymer type was historically performed using visual inspection under stereomicroscopes, especially in studies published before 2013 [90]. Spectroscopic confirmation using FTIR or Raman techniques became more widespread after 2015–2016 as access to instrumentation increased and methodological standards matured [91,92]. More recent studies have begun to adopt multi-modal workflows combining FTIR, Raman, and AI-driven imaging to improve classification accuracy and throughput [93,94]. This progression reflects increased community convergence toward instrument-based verification, which improves reproducibility compared to earlier visually based classifications.

Reported microplastic shapes include foam, fiber, film, fragment, and pellet with the classification based on the morphology of the particles [95,96]. However, shape terminology was not always applied consistently. For example, “fibers” may refer variously to lines, filaments, or threads, while “pellets” may include microbeads or spheres [16]. Such variation in terminology creates semantic ambiguity that complicates automated aggregation in large databases, even when studies appear to report similar categories.

Color reporting also varied widely. Microplastic colors include black, blue, gray, green, orange, red, white, yellow, and transparent. However, color determination is inherently subjective, influenced by lighting conditions, sample treatment, and observer experience [97]. This subjectivity introduces observer bias that undermines data harmonization across laboratories. Kotar et al. [98] conducted an interlaboratory comparison involving twenty-two laboratories across six countries. The study examined the accuracy and precision of recovering microplastic characteristics, including color. Their results showed wide recovery variations among the study participants, with the greatest discrepancies observed for white and transparent microplastic particles. Green particles were the most consistent recoveries. White and orange were underreported, and blue and transparent were overreported. The authors suggested that using standardized color keys and additional training could improve consistency in microplastic identification. In this regard, Ref. [97] developed a 120-color reference palette to assign colors to marine plastics, which can serve as a valuable tool for harmonizing visual color classification.

More broadly, recent interlaboratory calibration efforts have emphasized the importance of standardized reference materials, color palettes, and harmonized workflows to minimize observer variability [99]. Likewise, automated tools such as machine learning–based image analysis and hyperspectral or Raman imaging offer promising alternatives to visual classification. These methods enable objective and high-throughput particle characterization [92,100].

Despite these methodological advances, complete characteristic reporting remains scarce. Only 35% of studies reported all four characteristics (polymer, shape, size, and color), while 29.7% reported three attributes, 22.5% reported two, and 12.8% reported only one attribute (Table 4). Although 80% of studies reported polymer type, a significant proportion did not include full morphological or visual metadata. This partial reporting limits the ability to reclassify or standardize datasets during database integration. It poses particular challenges when comparing sources, degradation patterns, or exposure pathways across environmental compartments.

Table 4.

Proportion of studies reporting various combinations of microplastic characteristics.

3.7. Size Range of Microplastics

The upper size boundary of microplastics is commonly defined as <5 mm [3,84,99,101]. The lower size boundary, however, varies across the literature, with [15,101,102,103], respectively, suggesting 1 mm, 100 µm, 20 µm, 1.6 µm, and 1 µm as lower thresholds. This inconsistency in cutoff definitions reflects both the absence of a universally accepted definition and differences in analytical capability across laboratories.

Across the 355 studies analyzed, the reported minimum detectable particle size ranged from 0.45 µm to 1000 µm, while maximum sizes spanned from 300 µm to 5000 µm (Table 5). The most frequently applied lower thresholds were 330 µm and 300 µm, each reported in 14% of studies. These were followed by 100 µm (11.8%), 50 µm (10.5%), and 20 µm (8.3%). Larger limits such as 500 µm (7.5%) and 1000 µm (8.8%) were less common. Most studies (86.2%) set the upper limit at 5000 µm (5 mm), consistent with the standard microplastic definition. A few employed slightly lower cutoffs, including 4750 µm (2.9%), 4000 µm (1.3%), and 2000 µm (1.3%).

Table 5.

Summary of minimum and maximum microplastic size thresholds reported across reviewed studies. Percentages represent the proportion of records specifying each threshold value.

Studies using advanced spectroscopic workflows, particularly Raman-based imaging, tended to report much lower size thresholds. In contrast, studies relying on stereomicroscopy and manual sorting typically set their practical detection limits based on the smallest particles that could be manipulated with tweezers or observed under magnification. For example, Ref. [16] used a 45 µm lower threshold to ensure reliable handling and spectroscopic confirmation, while Ref. [57] set a 300 µm limit for operational efficiency with ATR-FTIR. This illustrates a trade-off between analytical sensitivity and processing feasibility that contributes to size-range variability across studies

Spectroscopic methods impose different detection capabilities: µFTIR is well-suited for particles larger than ~10 µm, while Raman spectroscopy can identify particles down to ~0.5 µm [104,105,106,107]. As a result, datasets derived from Raman-based analyses often include finer microplastics and sometimes even extend into the “nanoplastics” domain. In contrast, studies using only visual inspection or coarse-mesh approaches omit these smaller fractions entirely. This methodological divergence underlines the importance of documenting detection thresholds in published datasets.

Beyond instrumentation, methodological choices influence detectable size ranges. Density separation protocols rely on solutions with densities higher than most polymers (0.8–1.4 gcm−3; [90]). Common floating reagents include NaCl (1.2 gcm−3), CaCl2 (1.4 gcm−3), ZnCl2 (1.6 gcm−3), and NaI (1.8 gcm−3) [56,106,108,109]. NaCl, while widely used due to low cost and environmental safety, exhibits lower recovery rates (typically 85%; [56,110]) compared to denser reagents. He et al. [106] showed that recovery efficiency decreases as particle size decreases: ~93% for 1–5 mm, ~90% for 0.5–1 mm, and ~87% for 0.1–0.5 mm. Similar trends were reported by [57,110]. This introduces a systematic underrepresentation of the smallest microplastic fractions in many studies, which should be recognized when aggregating datasets.

Field collection methods further constrain size recovery. Nets with mesh sizes ≥ 300 µm dominated water sampling. As a result, these methods rarely captured particles smaller than 300 µm. In contrast, sediment studies more frequently recovered fine fractions because they often used post-separation filtration through fine mesh or membrane filters, typically in the 0.3–200 µm range [19,33]. Consequently, reported size distributions reflect detection capacity as much as environmental reality.

In summary, size distributions reported in the literature represent method-limited fractions of the true environmental particle spectrum rather than complete size inventories. This emphasizes the importance of documenting both the detection threshold of analytical instruments and the mesh or pore size of sampling devices to support valid size harmonization across datasets.

3.8. Data Availability

As the microplastics research field grows and new methods and standards are developed, it is important for data to be made FAIR and shared to enable reproducibility, data harmonization, and a uniform global understanding of the pollution problem [22,37,64,111]. Only 19.2% of the studies we examined provided links to their data, either as Supplementary Material or deposited in a repository. Jenkins et al. [37] similarly reported that just 28.5% of 785 analyzed articles contained a data sharing statement, with only 13.8% providing access through a formal repository. This indicates that despite growing awareness of open science principles, most published microplastic datasets remain effectively inaccessible for secondary analysis.

To enable meaningful reuse and integration into global repositories, microplastic datasets need to be shared at the level of individual particles rather than solely as aggregated concentration values. Miller et al., [16], for example, proposed a structured datasheet format in which each particle entry includes fields for shape, color, size, and polymer type. Sharing particle-level metadata rather than only summary statistics increases the analytical flexibility of datasets. It allows downstream users to reprocess results under harmonized classification schemes or to apply new categorization rules without re-analyzing raw samples.

Even when datasets are made available, a lack of standardized data formatting and metadata fields often necessitates extensive manual harmonization before they can be integrated into repositories such as NOAA NCEI, EMODnet, or PANGAEA. This suggests that openness alone does not ensure interoperability—without standardized data structures and metadata conventions, “available” datasets may still remain effectively isolated.

Operationalizing the FAIR principles in the microplastics domain requires explicit guidance. For data to be Findable, it should be deposited in citable repositories with DOI assignment and standardized metadata tags for key fields such as sampling coordinates, matrix (water/sediment), and size thresholds. To be Accessible, datasets must be downloadable in non-proprietary, machine-readable formats with clearly stated licensing conditions. However, a notable number of studies that claimed data availability in Supplementary Files hosted them as PDFs or embedded tables, formats that are technically accessible but not machine-actionable, limiting downstream reuse. Interoperability requires alignment with controlled vocabularies for particle descriptors and standardized measurement units. For example, items per cubic meter (items/m3) are used for water, and items per gram dry weight (items/g d.w.) for sediments. It also depends on documenting key contextual information such as mesh size and detection method. Finally, for Reusability, datasets should include methodological descriptors such as recovery efficiency, detection thresholds, and confirmation techniques, enabling others to evaluate uncertainty and integrate records appropriately. Across the datasets examined, these elements were present inconsistently, indicating that many datasets meet the “F” and “A” components of FAIR but fall short on the “I” and “R” dimensions that determine long-term harmonization potential.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

The rapid expansion of microplastics research over the past decade has produced a substantial yet methodologically fragmented body of literature. Our synthesis demonstrates that most studies focus on marine surface environments, driven by established ocean-monitoring programs and international funding priorities. In contrast, freshwater systems remain comparatively underrepresented, despite their key role as transport pathways. Sampling designs are spatially broad but temporally shallow, with the majority of studies collecting data only once, which limits alignment with hydrological dynamics or long-term observational frameworks. Instrument selection, particularly the dominance of nets with coarse mesh sizes in water sampling, introduces structural biases by underrepresenting fine and fiber-rich fractions, which affects cross-study comparability. While spectroscopic confirmation of polymer type has increased in recent years, full particle characterization remains incomplete in most studies. Additionally, fewer than one-fifth of the datasets are shared in FAIR-compliant formats with particle-level metadata.

Based on the methodological gaps and reporting inconsistencies identified across the reviewed literature, we provide below (Table 6) a set of prioritized recommended actions intended to support harmonization of future microplastic monitoring and data reporting efforts.

Table 6.

Recommended harmonization actions.

Presenting these recommendations in a prioritized format provides a structured pathway for translating bibliographic insights into actionable steps toward data harmonization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microplastics5010011/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Author Contributions

E.S.N. and J.C. created the first draft of the paper, and all authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. T.E.C., Z.W., Y.H.L., A.M.K., G.T., T.O. and R.G. contributed equally to data extraction efforts. T.B., K.L., P.M., E.S., and J.A.B.W. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Northern Gulf Institute, Mississippi State University is supported by a NOAA grant G00005988. E.S.N. was supported by an Early-Career Research Fellowship from the Gulf Research Program of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (Grant # 2000012639) and NOAA National Sea Grant (Grant # NA24OARX417C0421-T1-01).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Microplastics_DataExtract_xlsx/26131198.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the availability of freely accessible research outputs that made this study possible. All data used in this work were manually extracted from published, peer-reviewed articles, and full credit is extended to the original authors and journals for making their datasets publicly available. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions, which significantly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: More than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, R.C.; Seeley, M.E.; La Guardia, M.J.; Mai, L.; Zeng, E.Y. A Global Perspective on Microplastics. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2020, 125, e2018JC014719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, G.; Acharya, A.; Marahatha, R.; Modi, B.; Paudel, R.; Adhikari, A.; Raut, B.K.; Aryal, S.; Parajuli, N. Microplastics in environment: Global concern, challenges, and controlling measures. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 4673–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogi, K.; Rabari, V.; Patel, K.; Patel, H.; Trivedi, J.; Rakib, M.R.J.; Kumar, R.; Proshad, R.; Walker, T.R. Gujarat’s plastic plight: Unveiling characterization, abundance, and pollution index of beachside plastic pollution. Discov. Oceans 2024, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Kauffman, A.E.; Li, L.; McFee, W.; Cai, B.; Weinstein, J.; Lead, J.R.; Chatterjee, S.; Scott, G.I.; Xiao, S. Health impacts of environmental contamination of micro- and nanoplastics: A review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaria, G.; Avio, C.G.; Mineo, A.; Lattin, G.L.; Magaldi, M.G.; Belmonte, G.; Moore, C.J.; Regoli, F.; Aliani, S. The Mediterranean Plastic Soup: Synthetic polymers in Mediterranean surface waters. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Stoefen-O’Brien, A.; Weis, J.; Ioakeimidis, C.; Schuyler, Q.; Makarenko, I.; Griffiths, H.; Bondareff, J.; Vethaak, D.; Deidun, A.; et al. Are litter, plastic and microplastic quantities increasing in the ocean? Micropl. Nanopl. 2021, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Shruti, V.C.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Roy, P.D. Microplastic diagnostics in humans: “The 3Ps” Progress, problems, and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Besseling, E.; Foekema, E.M. Leaching of plastic additives to marine organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 187, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vethaak, A.D.; Leslie, H.A. Plastic debris is a human health issue. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6825–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, J.; Craig, C.; Little, S.; Donnelly, M.; Fox, D.; Zhai, L.; Walters, L. Microplastic accumulation in the gastrointestinal tracts in birds of prey in central Florida, USA. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, T.; Singh, S.; Gupta, G.D.; Verma, S.K. Microplastics in environment: A comprehension on sources, analytical detection, health concerns, and remediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 114707–114721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Besseling, E.; Shim, W.J. Nanoplastics in the aquatic environment. Critical review. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutov, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Sedlak, M.; Lin, D.; Box, C.; Holleman, C.; Rochman, C.M.; Sutton, R. Recommended best practices for collecting, analyzing, and reporting microplastics in environmental media: Lessons learned from comprehensive monitoring of San Francisco Bay. J. Hazard. Mater 2021, 409, 124770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Guevara, F.; Roy, P.D.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Shruti, V. Coverage of microplastic data underreporting and progress toward standardization. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaire, J.C.; Pomeroy, C.; Herczegh, S.M.; Haggart, O.; Murphy, M. Microplastic abundance and distribution in the open water and sediment of the Ottawa River, Canada, and its tributaries. FACETS 2017, 2, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P. Methods for sampling and detection of microplastics in water and sediment: A critical review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Velázquez, K.; Duque-Olivera, K.G.; Santiago-Gordillo, D.A.; Hoil-Canul, E.R.; Guzmán-Mar, J.L.; Villanueva-Rodríguez, M.; Ronderos-Lara, J.G.; Castillo-Quevedo, C.; Cabellos-Quiroz, J.L. Microplastics on sandy beaches of Chiapas, Mexico. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 70, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Zaib, A.; Rehman, S.A.U.; Riaz, N.; Eliw, M.; Hayat, F.; Li, H.; Wang, F. Effects of micro(nano)plastics on soil nutrient cycling: State of the knowledge. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadjro, E.S.; Webster, J.A.B.; Boyer, T.P.; Cebrian, J.; Collazo, L.; Kaltenberger, G.; Larsen, K.; Lau, Y.H.; Mickle, P.; Toft, T.; et al. The NOAA NCEI marine microplastics database. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, M.E.; Chaves Montero, M.d.M.; Galgani, F.; Giorgetti, A.; Vinci, M.; Le Moigne, M.; Brosich, A. EMODnet marine litter data management at pan-European scale. Ocean Coast. Manag 2019, 181, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Tekman, M.B.; Gutow, L. Litterbase: An online portal for marine litter and microplastics and their implications for marine life. In Fate and Impact of Microplastics in Marine Ecosystems, MICRO 2016; Baztan, J., Jorgensen, B., Pahl, S., Thompson, R., Vanderlinden, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michida, Y.; Chavanich, S.; Chiba, S.; Cordova, M.R.; Cozzar Cabanas, A.; Galgani, F.; Hagmann, P.; Hinata, H.; Isobe, A.; Kershaw, P.; et al. Guidelines for Harmonizing Ocean Surface Microplastic Monitoring Methods (Version 1.0), 2019; 71p, Ministry of the Environment Japan. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/en/water/marine_litter/guidelines/guidelines.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Salam, M.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Zaib, A.; Yang, W.; Li, Q. The impacts of microplastics and biofilms mediated interactions on sedimentary nitrogen cycling: A comprehensive review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiron, D.; Burton, P.; Marcon, Y.; Gaye, A.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.R.; Perola, M.; Stolk, R.P.; Foco, L.; Minelli, C.; Waldenberger, M.; et al. Data harmonization and federated analysis of population-based studies: The BioSHaRE project. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2013, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kush, R.D.; Warzel, D.; Kush, M.A.; Sherman, A.; Navarro, E.A.; Fitzmartin, R.; Pétavy, F.; Galvez, J.; Becnel, L.B.; Zhou, F.L.; et al. Fair data sharing: The roles of common data elements and harmonization. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 107, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Messerschmidt, L.; Bravo, I.; Waldbauer, M.; Bhavikatti, R.; Schenk, C.; Grujic, V.; Model, T.; Kubinec, R.; Barceló, J. A General Primer for Data Harmonization. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; Bonino da Silva Santos, L.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutroneo, L.; Reboa, A.; Besio, G.; Borgogno, F.; Canesi, L.; Canuto, S.; Dara, M.; Enrile, F.; Forioso, I.; Greco, G.; et al. Microplastics in seawater: Sampling strategies, laboratory methodologies, and identification techniques applied to port environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2020, 27, 8938–8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.N.; Fauvelle, V.; Grenz, C.; Ourgaud, M.; Schmidt, N.; Strady, E.; Sempere, R. Highlights from a review of microplastics in marine sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, N.; Hamidian, A.H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. Microplastic sampling techniques in freshwaters and sediments: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4225–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.B.; Erkan, H.S.; Engin, G.O. Current status of studies on microplastics in the world’s marine environments. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumoorthi, K.; Luis, A.J. Recent trends on microplastics abundance and risk assessment in coastal Antarctica: Regional meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 324, 121385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, K.B.; Ganshorn, H.; Rutley, S.; Scott, D.R. Data-Sharing Practices in Publications Funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research: A Descriptive Analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. Open Access J. 2021, 9, E980–E987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, T.; Persaud, B.D.; Cowger, W.; Szigeti, K.; Roche, D.G.; Clary, E.; Slowinski, S.; Lei, B.; Abeynayaka, A.; Nyadjro, E.S.; et al. Current state of microplastic pollution research data: Trends in availability and sources of open data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 912107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, D.G.; Raby, G.D.; Norin, T.; Ern, R.; Scheuffele, H.; Skeeles, M.; Morgan, R.; Andreassen, A.H.; Clements, J.C.; Louissaint, S.; et al. Paths towards greater consensus building in experimental biology. Exp. Biol. 2022, 225, jeb243559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender Law, K.; Morét-Ferguson, S.; Maximenko, N.A.; Proskurowski, G.; Peacock, E.E.; Hafner, J.; Reddy, C.M. Plastic Accumulation in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. Science 2010, 329, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunnell, J.W.; Dunning, K.H.; Scheef, L.P.; Swanson, K.M. Measuring plastic pellet (nurdle) abundance on shorelines throughout the Gulf of Mexico using citizen scientists: Establishing a platform for policy-relevant research. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faure, F.; Saini, C.; Potter, G.; Galgani, F.; de Alencastro, L.F.; Hagmann, P. An evaluation of surface micro- and mesoplastic pollution in pelagic ecosystems of the Western Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 12190–12197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keerthika, K.; Padmavathy, P.; Rani, V.; Jeyashakila, R.; Aanand, S.; Kutty, R. Spatial, seasonal and ecological risk assessment of microplastics in sediment and surface water along the Thoothukudi, south Tamil Nadu, southeast India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulfer, V.M.; Walsh, J.P. Extensive estuarine sedimentary storage of plastics from city to sea: Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, USA. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Devriese, L.; Galgani, F.; Robbens, J.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics in sediments: A review of techniques, occurrence and effects. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanvey, J.S.; Lewis, P.J.; Lavers, J.L.; Crosbie, N.D.; Pozo, K.; Clarke, B.O. A review of analytical techniques for quantifying microplastics in sediments. Anal. Meth. 2017, 9, 1369–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.A.; Eriksen, R.; Wilcox, C.; Hardesty, B.D. Microplastic distribution at different sediment depths in an urban estuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITRC (Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council). Microplastics Team Materials; Interstate Technology & Regulatory Council, MP Team: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://mp-1.itrcweb.org (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Sherman, P.; van Sebille, E. Modeling marine surface microplastic transport to assess optimal removal locations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.R.; Woodward, J.; Rothwell, J.J. Microplastic contamination of river beds significantly reduced by catchment-wide flooding. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.S.; Loutan, A.; Groeneveld, T.; Molenaar, D.; Kroetch, K.; Bujaczek, T.; Kolter, S.; Moon, S.; Huynh, A.; Khayam, R.; et al. Estimated discharge of microplastics via urban stormwater during individual rain events. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1090267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, J.E.; Carpenter, S.R.; Grimm, N.B.; Gosz, J.R.; Seastedt, T.R. The U.S. Long Term Ecological Research Program. BioScience 2003, 53, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhua, T.; Gutekunst, S.B.; Biastoch, A. A near-synoptic survey of ocean microplastic concentration along an around-the world sailing race. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.; Muff, L.F.; Pham, C.K.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Lehner, R. Spatial and temporal analysis of meso- and microplastic pollution in the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian Seas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, A.P.W.; Cathey, S.E.; Petersen, C.W. Marine environment microfiber contamination: Global patterns and the diversity of microparticle origins. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, B.; Murphy, F.; Ewins, C. Validation of density separation for the rapid recovery of microplastics from sediment. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prume, J.A.; Laermanns, H.; Löder, M.G.J.; Laforsch, C.; Bogner, C.; Koch, M. Evaluating the effectiveness of the MicroPlastic Sediment Separator (MPSS). Micropl. Nanopl 2023, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, M.; Stoewer, S.-C.; Fischer, E.K. On the representativeness of pump water samples versus manta sampling in microplastic analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Flury, M. How to take representative samples to quantify microplastic particles in soil? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, W.P.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Canals, M. Floating microplastics and aggregate formation in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 140, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Nivem, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines worldwide: Sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, L.C.; Sanchez-Vidal, A.; Canals, M.; Paterson, G.L.J.; Coppock, R.; Sleight, V.; Calafat, A.; Rogers, A.D.; Narayanaswamy, B.E.; Thompson, R.C. The deep sea is a major sink for microplastic debris. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2014, 1, 140317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Michela, A.; Gérigny, O.; Maes, T.; Tambutté, E.; Harris, P.T. Marine Litter, Plastic, and Microplastics on the Seafloor. In Plastics and the Ocean: Origin, Characterization, Fate, and Impacts; Andrady, A.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 151–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Booth, A.M.; Hamilton, B.M.; Thaysen, C.; Primpke, S.; Munno, K.; Lusher, A.L.; Dehaut, A.; Vaz, V.P.; Liboiron, M.; et al. Reporting guidelines to increase the reproducibility and comparability of research on microplastics. Appl. Spectrosc. 2020, 74, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokai, T.; Uchida, K.; Kuroda, M.; Isobe, A. Mesh selectivity of neuston nets for microplastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull 2021, 165, 112111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.; Sullivan, P.J.; Walter, M.T. What you net depends on if you grab: A meta-analysis of sampling method’s impact on measured aquatic microplastic concentration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 12930–12942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.C.; Titmus, A.J.; Ford, M. Scales of spatial heterogeneity of plastic marine debris in the northeast Pacific Ocean. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.J.; Warrack, S.; Langen, V.; Challis, J.K.; Hanson, M.L.; Rennie, M.D. Microplastic contamination in lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, A.P.W.; Neumann, C.A.; Berger, M.L.; Shaw, S.D. Grab vs. neuston tow net: A microplastic sampling performance comparison and possible advances in the field. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Tassin, B. Synthetic and non-synthetic anthropogenic fibers in a river under the impact of Paris Megacity: Sampling methodological aspects and flux estimations. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 618, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubaish, F.; Liebezeit, G. Suspended microplastics and black carbon particles in the Jade System, Southern North Sea. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2013, 224, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Kwon, O.Y.; Lee, K.-W.; Song, Y.K.; Shim, W.J. Marine neustonic microplastics around the southeastern coast of Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 96, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.R. An Account of the Principles of Measurement and Calculation; Longmans: London, UK, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, S.S. On the theory of scales of measurement. Science 1946, 103, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astin, A.V. Standards of measurement. Sci. Am. 1968, 218, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftanas, M.S. Theories, models, and standard systems of measurement. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, G.S. Conversion of units of measurement. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1995, 21, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cardarelli, F.; Shields, M.J. Scientific Unit Conversion: A Practical Guide to Metrication; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, H.J. Standardization: What’s in a Name? In Standardization: A Business Approach to the Role of National Standardization Organizations; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoutos, G.V.; Schofield, P.N.; Hoehndorf, R. The Units Ontology: A tool for integrating units of measurement in science. Database 2012, 2012, bas033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender Law, K.; Morét-Ferguson, S.E.; Goodwin, D.S.; Zettler, E.R.; DeForce, E.; Kukulka, T.; Proskurowski, G. Distribution of surface plastic debris in the Eastern Pacific Ocean from an 11-year data set. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4732–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisser, J.; Shaw, J.; Wilcox, C.; Hardesty, B.D.; Proietti, M.; Thums, M.; Pattiaratchi, C. Marine plastic pollution in waters around Australia: Characteristics, concentrations, and pathways. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C. Laboratory Methods for the Analysis of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Recommendations for Quantifying Synthetic Particles in Waters and Sediments. In NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS-OR&R; NOAA Marine Debris Division: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2015; Volume 48. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/10296 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Suaria, G.; Perold, V.; Lee, J.R.; Lebouard, F.; Aliani, S.; Ryan, P.G. Floating macro- and microplastics around the Southern Ocean: Results from the Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Liu, K.; Li, D. Prevalence of microplastic fibers in the marginal sea water column off southeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verla, A.W.; Enyoh, C.E.; Verla, E.N.; Nwarnorh, K.O. Microplastic–toxic chemical interaction: A review study on quantified levels, mechanism and implication. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B.; Soltani, N. Potentially toxic elements and microplastics in muscle tissues of different marine species from the Persian Gulf: Levels, associated risks, and trophic transfer. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 175, 113283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.K.; Duran, E.; Ottinger, M.A.; Woodrey, M.S.; Maness, T.J. Microplastics in the Gulf of Mexico: A bird’s eye view. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.F.; Nolasco, M.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.P.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Identification of microplastics using Raman spectroscopy: Latest developments and prospects. Water Res. 2018, 142, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käppler, A.; Fischer, M.; Scholz-Böttcher, B.M.; Oberbeckmann, S.; Labrenz, M.; Fischer, D.; Eichhorn, K.-J. Analysis of environmental microplastics by vibrational microspectroscopy: FTIR, Raman or both? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 8377–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primpke, S.; Wirth, M.; Lorenz, C.; Gerdts, G. Reference database design for automated analysis of microplastic samples based on FTIR spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 5131–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Si, C.; Qiu, C.; Wang, G. Microplastics analysis: From qualitative to quantitative. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 1652–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, M.; Warrier, A.K.; Kartha, V.B.; Unnikrishnan, V.K. Advances in microplastic characterization: Spectroscopic techniques and heavy metal adsorption insights. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 183, 118111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosal, R. Morphological description of microplastic particles for environmental fate studies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.T.; Diamond, M.L.; Helm, P.A. A fit for purpose categorization scheme for microplastic morphologies. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2022, 19, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, E.; Martin, C.; Galli, M.; Echevarría, F.; Duarte, C.M.; Cózar, A. The colors of the ocean plastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6594–6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotar, S.; McNeish, R.; Murphy-Hagan, C.; Renick, V.; Lee, C.-F.T.; Steele, C.; Lusher, A.; Moore, C.; Minor, E.; Schroeder, J.; et al. Quantitative assessment of visual microscopy as a tool for microplastics research: Recommendations for improving methods and reporting. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowger, W.; Steinmetz, Z.; Gray, A.; Munno, K.; Lynch, J.; Hapich, H.; Primpke, S.; De Frond, H.; Rochman, C.; Herodotou, O. Microplastic spectral classification needs an open source community: Open Specy to the rescue! Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 7543–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.; Singha, T.; Willans, M.; Hackett, M.; Pham, D.-S. A Domain-Adaptive Deep Learning Approach for Microplastic Classification. Microplastics 2025, 4, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Scherer, C.; Alvarez-Muñoz, D.; Brennholt, N.; Bourrain, X.; Buchinger, S.; Fries, E.; Grosbois, C.; Klasmeier, J.; Marti, T.; et al. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: What we know and what we need to know. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2014, 26, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigault, J.; ter Halle, A.; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.-Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.-L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current opinion: What is a nanoplastic? Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.L.; Obbard, J.P. Prevalence of microplastics in Singapore’s coastal marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, R.; Wang, S.-Q.; Koenig, J.L. FTIR microspectroscopy of polymeric systems. In Liquid Chromatography/FTIR Microspectroscopy/Microwave Assisted Synthesis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 137–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, R.; Enders, K.; Stedmon, C.A.; Mackenzie, D.M.A.; Nielsen, T.G. A critical assessment of visual identification of marine microplastic using Raman spectroscopy for analysis improvement. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J. Methods for separating microplastics from complex solid matrices: Comparative analysis. J. Hazard Mater 2021, 409, 124640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velimirovic, M.; Tirez, K.; Verstraelen, S.; Frijns, E.; Remy, S.; Koppen, G.; Rotander, A.; Bolea-Fernandez, E.; Vanhaecke, F. Mass spectrometry as a powerful analytical tool for the characterization of indoor airborne microplastics and nanoplastics. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2021, 36, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, E.M.; Noel, M.; Gies, E.A.; Ross, P.S. A novel, density-independent and FTIR compatible approach for the rapid extraction of microplastics from aquatic sediments. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, C.; Hudson, M.D.; Williams, I.D.; Langley, G.J. Evidence of underestimation in microplastic research: A meta-analysis of recovery rate studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.T.; Le, P.T.; Nguyen, T.N.H.; Hoang, T.Q.; Ngo, H.M.; Doan, T.O.; Le, T.P.Q.; Bui, H.T.; Bui, M.H.; Trinh, V.T.; et al. Selection of a density separation solution to study microplastics in tropical riverine sediment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partescano, E.; Jack, M.E.M.; Vinci, M.; Cociancich, A.; Altenburger, A.; Giorgetti, A.; Galgani, F. Data quality and FAIR principles applied to marine litter data in Europe. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 112965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.