Abstract

The presence of microplastics (MPs) in the environment, and the effects that the ingestion of these materials can have on organisms, can be aggravated by the adsorption of harmful substances on the surface or inside the MPs. Of special relevance are the studies that have been carried out on the adsorption and transport of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as well as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as dioxins and furans (PCDD/Fs). This review will delve into the research carried out to date regarding the adsorption by conventional and biodegradable MPs of dangerous organic compounds such as those mentioned. In general, the presence of MPs is considered a vector for the entry of these contaminants into living beings, since their capacity to adsorb contaminants is very high and they are ingested by different organisms that introduce these contaminants into the trophic chain.

1. Introduction

Plastics are synthetic organic polymers that are malleable and can be molded into solid objects of various kinds. Furthermore, they are strong, light, durable and inexpensive [1], properties that make them suitable for the manufacture of a wide range of products.

The main reason plastics are hazardous to the marine environment is their resistance to degradation. The natural decomposition of plastic objects in the sea occurs over an extremely long period of time, usually estimated to be between hundreds and thousands of years [2], so plastics accumulate in the marine environment and persist for decades [3]. During this time, chemical pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins are released into the sea. In addition, these plastics fragment and become smaller and smaller pieces, even becoming plastic microparticles (particles with a diameter of less than 5 mm) [4], which makes them easily ingested by animals [5,6].

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), such as PCBs and organochlorine pesticides, are present in aquatic systems around the world because of their widespread use, long-range transport, and persistence. Individual POPs have characteristic patterns of distribution that depend on regional patterns of use and their physical–chemical properties. An international group of research units is attempting to monitor POPs contamination around the world, using stranded plastic resin pellets [7].

In addition, a series of studies have been carried out that report on the importance of the amounts of pollutants present in the different marine environments. In a previous study [8], some results of the most relevant studies in this regard were shown. Contaminants such as PCBs, hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCHs), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDTs), and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) appear in it, and significant amounts of POPs are found in plastic pellets, which can aggravate the effects that their intake produces in the marine wildlife. The average values found in the literature are approximately 45 ng of PCBs/gpellet, 5 ng of HCH/gpellet, 20 ng of DDT/gpellet, and 2500 ng of PAHs/gpellet.

In addition, different studies have been carried out on the ability of plastics to absorb hydrophobic organic chemical compounds [9,10,11,12], which highlights the need for new policies that address this important problem. In fact, Kreisz et al. [13] have long proposed the use of plastics as PCDD/Fs adsorbents to reduce emissions in industrial facilities. Other authors, such as Enyoh et al. [14] also advocate the use of environmental plastics for contaminant removal, presenting plastics as low-cost adsorbents.

This tendency to adsorb dangerous organic compounds is also common in the case of microplastics (size less than 5 mm) and nanoplastics (equivalent diameter less than 100 nm). Countless studies have been described in the literature in which the adsorption of harmful compounds on the surface of microplastics is analyzed, indicating many times [15,16,17,18] that they serve as a vector for the transport of contaminants from the environment to living organisms.

Among the compounds studied, PAHs, dioxins, and furans (PCDD/Fs) stand out. These compounds have also been detected in products made from plastics [19] and in recycled plastics by different procedures [20]. The rationale for the need for this review is therefore the importance of the presence of carcinogenic and mutagenic compounds in the different microplastics present in aquatic and terrestrial environments, which will be incorporated into the food chain, eventually reaching human beings.

The importance of the presence of these compounds in microplastics has been shown in the literature. Sharma et al. [21] show that the adsorption capacity of carcinogenic PAHs on microplastics is between 46 and 236 μg/g, occurring in just 45 min in water. The e-waste microplastic-derived leachates were highly hazardous in nature, for example, the sum of PAHs was 3.17 mg/L, which is approximately 1000 times higher than the standard for benzo[a]pyrene.

2. Search and Review Procedure

In a first approach, searching was carried out using the words (“microplastic*” AND “pollutant*” AND “adsorp*”) and looking into Title, Abstract and Keywords. This search returned a total of 641 papers, excluding reviews and removing duplicates. Figure 1 shows the percentages of papers found in the MedLine, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, distributed by type of contaminant, by type of polymer, and by the shape of the microplastics mentioned in the article.

Figure 1.

Distribution of papers found in literature concerning the search words (“microplastic*” AND “pollutant*” AND “adsorp*”).

Given that the University of Alicante pollutants laboratory is specialized in the detection and analysis of organic compounds, it was decided to limit the search to two types of pollutants: PAHs and PCDD/Fs.

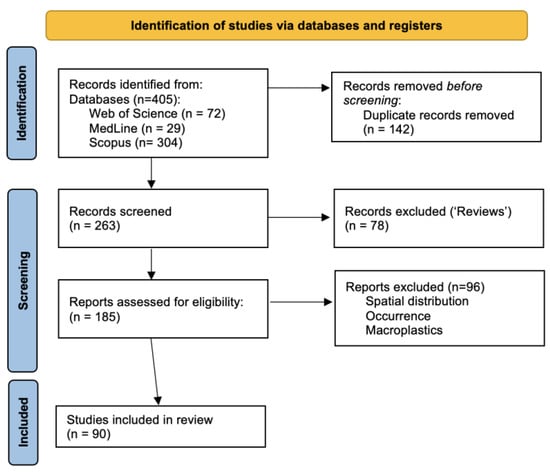

Following, a new search was carried out focused on the combination of the keywords (“microplastic*” AND “absorp*”) with (PAH* OR dioxin* OR PCDD*). The corresponding PRISMA [22] diagram is shown in Figure 2. The search offered several review-type articles as results that were eliminated. After a manual elimination of some results, a set of 90 references was obtained, which were then analyzed. The complete list of references is found in the References [11,13,14,15,16,17,18,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. The references to studies related to the spatial distribution of pollutants or their occurrence were manually eliminated, and only a few of them will be mentioned as they were considered highly relevant.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of screening process. Number of papers concerning keywords (“microplastic*” AND “absorp*”) with (PAH* OR dioxin* OR PCDD*).

There is an added difficulty with the subject of this review, since there are many works that have been excluded from the review by mentioning microplastics but were actually dealing with conventional plastics. For example, Kedzierski et al. [47] speak of the adsorption of compounds in different microplastics, but the fragments with which they work cannot really be considered in the range of microplastics. This occurs with many other studies that have been excluded.

3. MPs as Input Vector of PAHs and POPs in the Food Chain

Chua et al. [15] were the first authors to reveal the role that MPs play as a vector for the assimilation of POPs in organisms. The authors show that the polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) present in MPs are assimilated by living organisms, especially the more brominated congeners, while the particles are eliminated through the intestinal tract. Table 1 shows a summary of the most important data summarized in the present review.

Table 1.

Summary of data found in literature.

Kleinteich et al. [16] studied the toxicity of PAHs in contact with polyethylene microplastics in tests with bacteria. The authors show that MPs are an efficient transport vehicle for hydrophobic contaminants, but at the same time, the bioavailability of these contaminants in the environment is decreased, because of the adsorption that occurs quite rapidly. For example, the authors show that the presence of phenanthrene and anthracene has less effect when they are loaded on microplastics than without them.

Sorensen et al. [17] studied the kinetics of the adsorption process at 10 and 20 °C of fluorene and phenanthrene in polyethylene (PE) and polystyrene (PS) microbeads. The authors distinguish the ingestible (10 μm) and non-ingestible (200 μm) fraction by copepods. They show that MP-adsorbed PAHs do not accumulate in crustaceans, since only dissolved free PAHs are available to copepods. They also show that salinity is a very important point in the process. Similarly, Zhang et al. [18] indicated that an increase in the salinity of the water increases the zeta potential of the surface of MPs, and this produces an increase in the adsorption capacity of phenanthrene on polyurethane, polyurea, and urea-formaldehyde resin particles.

Zhu et al. [100] also showed that the presence of MPs delays the leaching of phenanthrene in the soil and decreases the bioavailability of this noxious. Additionally, Bartonitz et al. [25] discovered that the toxicity of phenanthrene is much lower in the presence of microplastics, and the presence of sediments is much more dangerous.

Hanslik et al. [44] evaluated the toxicity of PE and polymethyl metacrilate (PMMA) microplastics (less than 100 μm) and insist on the reduced bioavailability of contaminants in the presence of microplastics, which means that the potential of MPs as vectors is limited. Liu et al. [52] also showed that the accumulation of phenanthrene in crops is lower if a certain amount of microplastics is present together with the contaminant.

It is also important to note that not only are the number of contaminants adsorbed on the surface of the polymer but also those that are in the central part. Wang et al. [84] proposed a method to distinguish the surface and total concentration, which consists of the ultrasonic extraction of the compounds on the surface, and the total dissolution of the particles prior to determining the total concentration. The authors mainly studied dioxins and related compounds, including brominated congeners. The total concentration is shown to be approx. 355 times higher than the surface for dioxins and chlorinated furans, and this ratio increases to ca. 8100 in the case of brominated congeners. Compounds with a higher number of chlorine or bromine are more abundant, and in most cases, they are concentrated in the central part of the microplastic.

4. Kinetics of the Adsorption and Desorption Process

MPs uptake different potentially toxic elements. According to Igalavithana et al. [107], different mechanisms are present, such as physical adsorption, pore filling, surface complexation, and electrostatic attraction. The presence of UV radiation, microbes, and humidity can influence the pollutant uptake, as well as different environment conditions.

Many studies have been carried out showing that the kinetics of the adsorption process follows a pseudo-second-order equation. A pseudo-first-order model would represent that the rate-limiting step is a physical process affecting analyte concentrations. On the contrary, the pseudo-second-order model suggests the adsorption process involving the (chemical) interaction affinity between adsorbents and adsorbates [108].

For example, Zhao et al. [98] mentioned such kinetics for the adsorption of phenanthrene, pyrene, and some derivatives on the surface of different microplastics. Additionally, Bao et al. [92] reached this conclusion when studying the adsorption of phenanthrene and its hydroxy-derivatives in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) particles of 134 μm. This would indicate that the kinetics are dominated by the hydrophobic interaction. Yang et al. [90] used micro PS to determine the adsorption kinetics of pyrene and its substituted derivatives, also concluding that the rate is of second order with respect to the amount of contaminant.

It has also been observed that the presence of some adsorbed compounds interferes with the kinetics of the process for other compounds. Thus, Bakir et al. [23] showed, using isotopically labeled phenanthrene and DDT, that phenanthrene adsorption is modified by the presence of DDT on the particle surface. In another work, Bakir et al. [24] carried out a similar study but with perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and di(2-etilhexil) phthalate (DEHP), also showing interference. In the same work, the authors measured the kinetics of the desorption of these contaminants in the intestinal tract, compared to that which occurs in seawater, the former being much faster. This indicates that the desorption that would occur after the ingestion of microparticles by different animals would be very fast. Cormier et al. [32] also showed a rapid desorption of other contaminants (in this case, PFOS) under conditions similar to those existing in the stomach. Comier et al. insisted that the diameter of the particles plays a key role, with smaller particles’ desorption being much faster. The same is also indicated in the study by Zhang et al. [95]. Additionally, values of distribution coefficient were much higher (62.6 L/kg) for small particles of PE (4–6 μm) than for bigger particles (20.9 L/kg for 125–500 μm particles) [36].

Li et al. [78] mentioned that the desorption is dominated by the diffusion steps in the outer layer. Lin et al. [50] concluded that the external diffusion is fast and it is the diffusion in the pores that controls the speed, both for PAHs and for PCBs when studying the phenomenon in PS particles of 100 nanometers.

Gao et al. [41] studied the adsorption of compounds from oil (structurally similar to PAHs) in PE particles between 165 and 500 μm. They carried out a study of the kinetics, arriving at a pseudo-second-order adsorption model in which diffusion in the pores is the rate-controlling step. Adsorption at 25 °C and at neutral pH was the fastest when they studied the variation between 4 and 65 °C and at pHs between 2 and 12. The presence of an alkaline environment and the increase in ionic strength (presence of salts) also decreased adsorption of nitro-anthracene in various MPs, including PS, PP, and PE [106].

Lončarsk et al. [57] used the second-order model to estimate the kinetics of the adsorption process of PAHs on poly lactic acid (PLA), which implies that chemisorption is the adsorption mechanism involved.

5. Effect of Aging

Abaroa et al. [82] showed an increase in adsorption with aging, and proposed that the use of an indicator, the yellowness index (YI), related to the color change that microplastics present over time. This YI is estimated visually based on the color of the MPs and is related to the speed at which the POPs are adsorbed on the particles.

Likewise, Chen et al. [31] showed that the aging of MPs increased the presence of compounds related to dioxins in a very original study.

The presence of oxygenated groups on the surface increases its hydrophilicity, causing a reduction in the adsorption of organic compounds such as PAHs and other hydrophobic organic compounds (HOCs) [59]. Li et al. [105] showed that aging and etching (artificial weathering (etching)) of PE particles produces surface oxygenation, but also an increase in the specific surface area of the plastics, which ultimately translates into an increase in the adsorption of PAHs on polymers that have been subjected to aging and, particularly those that have been etched. Zhang et al. [18] indicated that aging decreases the affinity of MPs with organic pollutants, by increasing the amount of oxygenated functional groups.

Other authors, such as Cerná et al. [29] did not show significant differences in the adsorption capacity of MPs of polyurethane that had been subjected to aging. This may be because polyurethane is already a good adsorbent for PAHs, as will be discussed later. The authors indicated that the main driving factor is the flexibility of the polymer.

Aging is also responsible for the increase in the adsorption capacity of PS particles in water, air, and seawater, according to Ding et al. [35].

6. Main Findings Related to Different Aspects of Microplastics or Pollutants

6.1. Modifications of Microplastics

Several studies have been found that compare the ability of conventional microplastics with that obtained after some structural or surface modification.

One of the most interesting works is the one recently presented by Gui et al. [43], in which conventional polyethylene and chlorinated polyethylene (CPE) are used. Both polymers are tested on the adsorption of 13 different compounds, including PAHs, pesticides and benzene derivatives. It is notable that these authors concluded that PAHs and chlorobenzene adsorb faster on CPE than on conventional PE, while the other compounds do not show significant changes. The authors showed that the hydrophobicity of compounds is a prominent element that affects the partition of organic chemicals between MPs and fresh water.

However, Liu et al. [54] inhibited the adsorption capacity of other compounds such as ciprofloxacin in PE particles with chlorination and exposure to UV light. On the contrary, the PVC and PET particles increased the adsorption capacity.

Liu et al. [53] used nano-polystyrene (70 nm) to perform a pre-extraction of PS particles with organic solvents, eliminating the most hydrophobic fraction. This translates into a significant decrease in the adsorption of PAHs.

Yu et al. [91] modified the surface of PS microspheres with the introduction of carboxyl groups (-COOH). The two polymers showed similar naphthalene adsorption capacity (approx. 10 L/g), perhaps slightly lower in the modified PS.

Bao et al. [92] showed that the hydroxy-derivatives of phenanthrene exhibit less adsorption than phenanthrene itself, on PVC particles, concluding that the presence of the -OH group inhibits the fixation of the compound on the surface.

6.2. Chemical Modifications of the Adsorbate

The effect of some modifications of PAHs and POPs on adsorption by MPs has also been studied. One of the first works of these characteristics was that of Li et al. [49], in which PAHs containing N/O/S groups were studied. It was concluded that the lone pair of electrons in these compounds was the dominant factor in its contribution to the differences with other compounds. They also showed the importance of the presence of extractable organic matter in water (WEOM) since its presence prevents the adsorption of contaminants. Something similar was shown by Munoz et al. [62], who used PS, PET, PP, and high density PE in the form of microplastics to adsorb some drugs. When natural organic matter is present in the medium, it is preferentially adsorbed on the particles, reducing the availability of active sites by blocking.

Yu et al. [91] studied the modifications of the naphthalene molecule with charged groups (-NH2, -OH, -COOH) showing that the presence of these groups causes adsorption to occur faster, but the adsorption capacity of these modified naphthalene is much lower than unmodified naphthalene.

On the other hand, Yang et al. [90] showed that there were some substituted derivatives that facilitate adsorption. This is the case of CH3- substituted pyrene. However, as indicated by Yu et al. [91], substitutions with -OH, -NH2, and -COOH inhibit the adsorption of aromatic contaminants.

6.3. The Different Plastic Polymers

Abbasi et al. [93] showed the adsorption of naphthalene and phenanthrene in tiny poly ethylene terephthalate (PET) particles and showed that this plastic is capable of adsorbing 97% of the naphthalene and 27% of the phenanthrene present in a matrix containing 18 and 0.1 μm per liter of these compounds, respectively. However, the PET particles are capable of desorbing near the roots of the plants, losing between 22 and 29% of the adsorbed compounds.

For their part, Zhao et al. [98] compared three polar microplastics (polybutylene succinate (PBS), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polyurethane (PU)) with a typical non-polar MP, polystyrene (PS). In addition, they studied the adsorption of non-polar PAHs (phenanthrene and pyrene) and other polar derivatives (nitronaphthalene and naphthylamide). The main conclusion of the study was that adsorption in polar polymers is much faster than in conventional ones.

The existence of hydrogen bonds in the structure of polyurethane and polyamide make these polymers have a higher adsorption capacity, according to the results of Liu et al. [51], using bisphenol A.

The polyurethane, polyurea, and urea-formaldehyde resin particles studied by Zhang et al. [18], have negative charges on the surface, with oxygenated and nitrogenous groups, which allows PAHs to be easily adsorbed.

Zhu et al. [100] also studied the adsorption capacity of phenanthrene in different micrometric polymers, establishing the order PS > PE > PVC in terms of adsorption capacity. Bakir et al. [24] commented that of the POPs/plastic combinations examined, phenanthrene with PE gave the highest transport potential to organisms.

Černá et al. [29] studied the differences in the adsorption of PAHs in biodegradable and conventional polyurethane, observing a much faster adsorption in the biodegradable. In contrast, Lončarsk et al. [57] studied the adsorption of PAHs in PLA (biodegradable), this being very slow and of little relevance.

The adsorption of dioxin-like compounds has not been studied in such depth, perhaps due to the difficulty of analyzing these compounds. Chen et al. [31] compared the presence of PCDD/Fs and related compounds in polystyrene foam and in other plastics (PE, PP, PVC), showing that PS has much more ability to adsorb dioxins. Llorca et al. [56] worked on the adsorption of PCBs in MPs of different nature. The authors showed that compounds with a low chlorination degree show higher adsorption percentages in all polymers, surely due to the large dimensions of the more chlorinated molecules. Additionally, Llorca et al. showed that polymers such as PET and PS showed a higher affinity for PCBs than PE.

7. Conclusions

The organic compounds studied in this review, PAHs and PCDD/Fs, tend to be adsorbed by microplastic particles when they come into contact, both in aqueous media and from soil samples. These MPs can serve as a vector for these harmful compounds to enter the food chain, although several investigations indicated that the bioavailability of contaminants was reduced in the presence of microplastics.

An apparent second-order kinetics for the adsorption of the studied compounds has been determined, which would indicate that the adsorption takes place by chemical interaction between the microplastics and the adsorbed substances.

MPs have an adsorption capacity that increases over time, due to the effects of aging that increases the specific surface of the polymers.

Any modification made to the polymer or to the compound to be adsorbed, which involves an increase in the hydrophobicity of the molecules, will result in an increase in adsorption capacity. This is because the main driving force for adsorption is the hydrophobicity of the adsorbate, which is generally compatible with the polymers of the MPs present. For the same reason, more hydrophobic (or less polar) polymers will less efficiently transport organic contaminant molecules.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (SPAIN), grant number PID2019-105359RB-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Laist, D.W. Overview of the Biological Effects of Lost and Discarded Plastic Debris in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1987, 18, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and Fragmentation of Plastic Debris in Global Environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katsanevakis, S. A Growing Problem Sources, Distribution, Composition, and Impacts. Mar. Pollut. New Res. 2008, 2, 53–100. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.; Bamford, H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris; NOAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Basantes, M.F.; Nacimba-Aguirre, D.; Conesa, J.A.; Fullana, A. Presence of Microplastics in Commercial Canned Tuna. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, H. Call for Pellets! International Pellet Watch Global Monitoring of POPs Using Beached Plastic Resin Pellets. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1547–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iñiguez, M.E.; Conesa, J.A.; Fullana, A. Marine Debris Occurrence and Treatment: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisner, M.; Taniguchi, S.; Moreira, F.; Bícego, M.C.; Turra, A. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Plastic Pellets: Variability in the Concentration and Composition at Different Sediment Depths in a Sandy Beach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 70, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, O.; Kalbe, U.; Meißner, K.; Sobottka, S. Sorption Effects Interfering with the Analysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) in Aqueous Samples. Talanta 2014, 122, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shim, W.J.; Kwon, J.H.J.-H. Sorption Capacity of Plastic Debris for Hydrophobic Organic Chemicals. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 470–471, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Manzano, C.; Hentschel, B.T.; Simonich, S.L.M.; Hoh, E. Polystyrene Plastic: A Source and Sink for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Marine Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 13976–13984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kreisz, S.; Hunsinger, H.; Vogg, H. Technical Plastics as PCDD/F Absorbers. Chemosphere 1997, 34, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyoh, C.E.; Ohiagu, F.O.; Verla, A.W.; Wang, Q.; Shafea, L.; Verla, E.N.; Isiuku, B.O.; Chowdhury, T.; Ibe, F.C.; Chowdhury, M.A.H. “Plasti-Remediation”: Advances in the Potential Use of Environmental Plastics for Pollutant Removal. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.M.; Shimeta, J.; Nugegoda, D.; Morrison, P.D.; Clarke, B.O. Assimilation of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers from Microplastics by the Marine Amphipod, Allorchestes Compressa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8127–8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinteich, J.; Seidensticker, S.; Marggrander, N.; Zarf, C. Microplastics Reduce Short-Term Effects of Environmental Contaminants. Part II: Polyethylene Particles Decrease the Effect of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Microorganisms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorensen, L.; Rogers, E.; Altin, D.; Salaberria, I.; Booth, A.M. Sorption of PAHs to Microplastic and Their Bioavailability and Toxicity to Marine Copepods under Co-Exposure Conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, P.; Sun, H.; Ma, J.; Li, B. The Structure of Agricultural Microplastics (PT, PU and UF) and Their Sorption Capacities for PAHs and PHE Derivates under Various Salinity and Oxidation Treatments. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 257, 113525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, J.A.; Nuñez, S.S.; Ortuño, N.; Moltó, J. PAH and POP Presence in Plastic Waste and Recyclates: State of the Art. Energies 2021, 14, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, S.S.; Moltó, J.; Conesa, J.A.; Fullana, A. Heavy Metals, PAHs and POPs in Recycled Polyethylene Samples of Agricultural, Post-Commercial, Post-Industrial and Post-Consumer Origin. Waste Manag. 2022, 144, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.D.; Elanjickal, A.I.; Mankar, J.S.; Krupadam, R.J. Assessment of Cancer Risk of Microplastics Enriched with Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakir, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Competitive Sorption of Persistent Organic Pollutants onto Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2782–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakir, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C. Enhanced Desorption of Persistent Organic Pollutants from Microplastics under Simulated Physiological Conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartonitz, A.; Anyanwu, I.N.; Geist, J.; Imhof, H.K.; Reichel, J.; Graßmann, J.; Drewes, J.E.; Beggel, S. Modulation of PAH Toxicity on the Freshwater Organism G. Roeseli by Microparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 113999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, N.U.; Agboola, O.D.; Fred-Ahmadu, O.H.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Oluwalana, A.; Williams, A.B. Micro(Nano)Plastics Prevalence, Food Web Interactions, and Toxicity Assessment in Aquatic Organisms: A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.-B.; Kang, H.-M.; Byeon, E.; Kim, M.-S.; Ha, S.Y.; Kim, M.; Jung, J.-H.; Lee, J.-S. Phenotypic and Transcriptomic Responses of the Rotifer Brachionus Koreanus by Single and Combined Exposures to Nano-Sized Microplastics and Water-Accommodated Fractions of Crude Oil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Herrera, A.; Gómez, M.; Acosta-Dacal, A.; Martínez, I.; Henríquez-Hernández, L.A.; Luzardo, O.P. Organic Pollutants in Marine Plastic Debris from Canary Islands Beaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černá, T.; Pražanová, K.; Beneš, H.; Titov, I.; Klubalová, K.; Filipová, A.; Klusoň, P.; Cajthaml, T. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Accumulation in Aged and Unaged Polyurethane Microplastics in Contaminated Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaomeng, D.; Si, L.; Yanping, D.; Shuguang, L.; Yaoren, T. Advances in Research on Effects of Microplastics on Migration, Transformation and Bioavailability of Organic Pollutants in Water. Mater. Rep. 2020, 34, 21033–21037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Allgeier, A.; Zhou, Q.; Ouellet, J.D.; Crawford, S.E.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shi, H.; Hollert, H. Marine Microplastics Bound Dioxin-like Chemicals: Model Explanation and Risk Assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 364, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, B.; Borchet, F.; Kärrman, A.; Szot, M.; Yeung, L.W.Y.; Keiter, S.H. Sorption and Desorption Kinetics of PFOS to Pristine Microplastic. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 4497–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danopoulos, E.; Jenner, L.; Twiddy, M.; Rotchell, J.M. Microplastic Contamination of Salt Intended for Human Consumption: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Wei, L.; Hou, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Lin, D. Microplastics Altered Contaminant Behavior and Toxicity in Natural Waters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Mao, R.; Ma, S.; Guo, X.; Zhu, L. High Temperature Depended on the Ageing Mechanism of Microplastics under Different Environmental Conditions and Its Effect on the Distribution of Organic Pollutants. Water Res. 2020, 174, 115634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, M.L.; Oliva-Teles, L.; Pinto, R.; Carvalho, A.P.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Hornek-Gausterer, R.; Guimarães, L. Microplastics as a Vehicle of Exposure to Chemical Contamination in Freshwater Systems: Current Research Status and Way Forward. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Akhdhar, A.; Elwakeel, K.Z. Microplastics Prevalence, Interactions, and Remediation in the Aquatic Environment: A Critical Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M.A.; Chen, L.; Ashar, M.; Huang, W.; Zeng, J.N.; Zhang, C.F.; Zhang, D.D. Occurrence and Distribution of Microplastics and Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Sediments from the Qiantang River and Hangzhou Bay, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 196, 110536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, J.; Sobral, P.; Ferreira, A.M. Organic Pollutants in Microplastics from Two Beaches of the Portuguese Coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 1988–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, F.; Cao, W.; Zheng, L. Study on the Capability and Characteristics of Heavy Metals Enriched on Microplastics in Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 144, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Su, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Bao, R.; Peng, L. Sorption Behaviors of Petroleum on Micro-Sized Polyethylene Aging for Different Time in Seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, A.; Strafella, P.; Oysaed, K.B.; Fabi, G. First Occurrence and Composition Assessment of Microplastics in Native Mussels Collected from Coastal and Offshore Areas of the Northern and Central Adriatic Sea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 24407–24416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, B.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Su, L.; Zhao, Y. Prediction of Organic Compounds Adsorbed by Polyethylene and Chlorinated Polyethylene Microplastics in Freshwater Using QSAR. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanslik, L.; Seiwert, B.; Huppertsberg, S.; Knepper, T.P.; Reemtsma, T.; Braunbeck, T. Biomarker Responses in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Following Long-Term Exposure to Microplastic-Associated Chlorpyrifos and Benzo(k)Fluoranthene. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 245, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Skrzypek, G.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; Ortega-Zamora, C.; González-Sálamo, J.; González-Curbelo, M.Á.; Hernández-Borges, J. Microplastic-Adsorbed Organic Contaminants: Analytical Methods and Occurrence. Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 136, 116186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.; Jordao, L.; José, S.; Jordao, L.; Jose, S.; Jordao, L.; José, S.; Jordao, L.; Jose, S.; Jordao, L. Exploring the Interaction between Microplastics, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Biofilms in Freshwater. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedzierski, M.; D’Almeida, M.; Magueresse, A.; Le Grand, A.; Duval, H.; César, G.; Sire, O.; Bruzaud, S.; Le Tilly, V. Threat of Plastic Ageing in Marine Environment. Adsorption/Desorption of Micropollutants. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 127, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; He, H.; Xie, W.; Fan, S.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, B.; Pan, X. Adsorption and Photochemical Capacity on 17α-Ethinylestradiol by Char Produced in the Thermo Treatment Process of Plastic Waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.L.; Tan, H.D.; Zhang, L.L.; Wang, S.P.; Wang, Y.H.; Yu, K.F. The Implications of Water Extractable Organic Matter (WEOM) on the Sorption of Typical Parent, Alkyl and N/O/S-Containing Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Jiang, R.; Wu, J.; Wei, S.; Yin, L.; Xiao, X.; Hu, S.; Shen, Y.; Ouyang, G. Sorption Properties of Hydrophobic Organic Chemicals to Micro-Sized Polystyrene Particles. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shi, H.; Xie, B.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Zhao, Y. Microplastics as Both a Sink and a Source of Bisphenol A in the Marine Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 10188–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhan, X. The Joint Toxicity of Polyethylene Microplastic and Phenanthrene to Wheat Seedlings. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 130967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.J.; Fokkink, R.; Koelmans, A.A. Sorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons to Polystyrene Nanoplastic. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Fu, J.; Ou, H. Modifications of Ultraviolet Irradiation and Chlorination on Microplastics: Effect of Sterilization Pattern. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 152541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wu, X.; Pan, S.; Dai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, X. Photochlorination-Induced Degradation of Microplastics and Interaction with Cr(VI) and Amlodipine. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca, M.; Ábalos, M.; Vega-Herrera, A.; Adrados, M.A.; Abad, E.; Farré, M. Adsorption and Desorption Behaviour of Polychlorinated Biphenyls onto Microplastics’ Surfaces in Water/Sediment Systems. Toxics 2020, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončarsk, M.; Tubic, A.; Isakovski, M.K.; Jovic, B.; Apostolovic, T.; Nikic, J.; Agbaba, J. Modelling of the Adsorption of Chlorinated Phenols on Polyethylene and Polyethylene Terephthalate Microplastic. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2020, 85, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loncarski, M.; Gvoic, V.; Prica, M.; Cveticanin, L.; Agbaba, J.; Tubic, A.; Lončarski, M.; Gvoić, V.; Prica, M.; Cveticanin, L.; et al. Sorption Behavior of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Biodegradable Polylactic Acid and Various Nondegradable Microplastics: Model Fitting and Mechanism Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Liu, C.; He, D.; Xu, J.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Pan, X. Environmental Behaviors of Microplastics in Aquatic Systems: A Systematic Review on Degradation, Adsorption, Toxicity and Biofilm under Aging Conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, S.; Guchhait, R.; Chatterjee, A.; Pramanick, K. Co-Occurrence of Co-Contaminants: Cyanotoxins and Microplastics, in Soil System and Their Health Impacts on Plant—A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 794, 148752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Sobral, P. Plastic Marine Debris on the Portuguese Coastline: A Matter of Size? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2649–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Ortiz, D.; Nieto-Sandoval, J.; de Pedro, Z.M.; Casas, J.A. Adsorption of Micropollutants onto Realistic Microplastics: Role of Microplastic Nature, Size, Age, and NOM Fouling. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Näkki, P.; Eronen-Rasimus, E.; Kaartokallio, H.; Kankaanpää, H.; Setälä, O.; Vahtera, E.; Lehtiniemi, M. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Sorption and Bacterial Community Composition of Biodegradable and Conventional Plastics Incubated in Coastal Sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 143088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noro, K.; Yabuki, Y. Photolysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Adsorbed on Polyethylene Microplastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Cao, C.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Sorption and Leaching Behaviors between Aged MPs and BPA in Water: The Role of BPA Binding Modes within Plastic Matrix. Water Res. 2021, 195, 116956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puckowski, A.; Cwięk, W.; Mioduszewska, K.; Stepnowski, P.; Białk-Bielińska, A. Sorption of Pharmaceuticals on the Surface of Microplastics. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Sonne, C.; Brown, R.J.C.; Younis, S.A.; Kim, K.H. Adsorption of Environmental Contaminants on Micro- and Nano-Scale Plastic Polymers and the Influence of Weathering Processes on Their Adsorptive Attributes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, A.E.; Zucker, I. Interactions of Microplastics and Organic Compounds in Aquatic Environments: A Case Study of Augmented Joint Toxicity. Chemosphere 2022, 289, 133212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.W.; Gunderson, K.G.; Green, L.A.; Rediske, R.R.; Steinman, A.D. Perfluoroalkylated Substances (Pfas) Associated with Microplastics in a Lake Environment. Toxics 2021, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Wang, J.; Zhan, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, F.; Wang, X. Sorption Behaviors of Crude Oil on Polyethylene Microplastics in Seawater and Digestive Tract under Simulated Real-World Conditions. Chemosphere 2020, 257, 127225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, F.; Ma, J. Laboratory Simulation of Microplastics Weathering and Its Adsorption Behaviors in an Aqueous Environment: A Systematic Review. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Song, Y.; He, F.; Jing, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, R. A Review of Human and Animals Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Health Risk and Adverse Effects, Photo-Induced Toxicity and Regulating Effect of Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelamatti, T.; Rios-Mendoza, L.M.; Hoyos-Padilla, E.M.; Galván-Magaña, F.; De Camillis, R.; Marmolejo-Rodríguez, A.J.; González-Armas, R. Contamination Knows No Borders: Toxic Organic Compounds Pollute Plastics in the Biodiversity Hotspot of Revillagigedo Archipelago National Park, Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 170, 112623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Yu, X.; Cai, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, J. Microplastics and Associated PAHs in Surface Water from the Feilaixia Reservoir in the Beijiang River, China. Chemosphere 2019, 221, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubić, A.; Lončarski, M.; Maletić, S.; Jazić, J.M.; Watson, M.; Tričković, J.; Agbaba, J. Significance of Chlorinated Phenols Adsorption on Plastics and Bioplastics during Water Treatment. Water 2019, 11, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vedolin, M.C.; Teophilo, C.Y.S.; Turra, A.; Figueira, R.C.L. Spatial Variability in the Concentrations of Metals in Beached Microplastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.C.; Pham, M.H. Ecotoxicological Effects of Microplastics on Aquatic Organisms: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 44716–44725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, X.; Qin, L.; Yin, D. Evaluating the Effect of Different Modified Microplastics on the Availability of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Water Res. 2020, 170, 115290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J. Comparative Evaluation of Sorption Kinetics and Isotherms of Pyrene onto Microplastics. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J. Different Partition of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon on Environmental Particulates in Freshwater: Microplastics in Comparison to Natural Sediment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 147, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Yu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, R. Sorption Behaviors of Phenanthrene on the Microplastics Identified in a Mariculture Farm in Xiangshan Bay, Southeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaroa-Pérez, B.; Ortiz-Montosa, S.; Hernández-Brito, J.J.; Vega-Moreno, D. Yellowing, Weathering and Degradation of Marine Pellets and Their Influence on the Adsorption of Chemical Pollutants. Polymers 2022, 14, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yue, D.; Wang, H. In Situ Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Coating of Polymers for Separating Hazardous PVC from Microplastic Mixtures. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 407, 127170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-C.; Lin, J.C.-T.; Dong, C.-D.; Chen, C.-W.; Liu, T.-K. The Sorption of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Microplastics from the Coastal Environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiśniowska, E.; Włodarczyk-Makuła, M.; Wisniowska, E.; Wlodarczyk-Makula, M. Adsorption of Selected 3-and 4-Ring Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Polyester Microfibers—Preliminary Studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 232, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, K.; Huang, X.; Liu, J. Sorption of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products to Polyethylene Debris. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 8819–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Cao, W.; Qu, R.; Zhou, D.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z. Photochemical Transformation of Decachlorobiphenyl (PCB-209) on the Surface of Microplastics in Aqueous Solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, Q. Co-Exposure to Different Sized Polystyrene Microplastics and Benzo[a]Pyrene Affected Inflammation in Zebrafish and Bronchial-Associated Cells. Kexue Tongbao/Chinese Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 4281–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, X.; Huang, B.; He, Y.; Cai, Z. Exploring the Adsorption Behavior of Benzotriazoles and Benzothiazoles on Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics in the Water Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, W.; Zhou, X.; Hao, Q.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. Comparing the Sorption of Pyrene and Its Derivatives onto Polystyrene Microplastics: Insights from Experimental and Computational Studies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 113086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.D.; Yang, B.; Waigi, M.G.; Peng, F.; Li, Z.K.; Hu, X.J. The Effects of Functional Groups on the Sorption of Naphthalene on Microplastics. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.-Z.Z.Z.; Chen, Z.-F.Z.F.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, G.; Qi, Z.; Cai, Z. Adsorption of Phenanthrene and Its Monohydroxy Derivatives on Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics in Aqueous Solution: Model Fitting and Mechanism Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, S.; Moore, F.; Keshavarzi, B. PET-Microplastics as a Vector for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in a Simulated Plant Rhizosphere Zone. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fei, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Yu, B.; Wang, J.; Tong, Y.; Wen, D.; Zhou, B.; et al. Interaction of Microplastics and Organic Pollutants: Quantification, Environmental Fates, and Ecological Consequences. Handb. Environ. Chem. 2020, 95, 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Lei, Y.; Qian, J.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Dai, L.; Sun, K.; Guo, H.; Sui, G.; et al. Sorption of Organochlorine Pesticides on Polyethylene Microplastics in Soil Suspension. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 223, 112591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J. The Removal of Microplastics in the Wastewater Treatment Process and Their Potential Impact on Anaerobic Digestion Due to Pollutants Association. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; He, H.; Cheng, X.; Ma, T.; Hu, J.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Adsorption Behavior and Mechanism of 9-Nitroanthracene on Typical Microplastics in Aqueous Solutions. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.F.; Rong, L.L.; Xu, J.P.; Lian, J.P.; Wang, L.; Sun, H.W. Sorption of Five Organic Compounds by Polar and Nonpolar Microplastics. Chemosphere 2020, 257, 127206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.Z.; Chen, Y.; Deng, C.; Qi, H.Y.; Zhang, H. Salt Crust-Assisted Thermal Decomposition Method for Direct and Simultaneous Quantification of Polypropylene Microplastics and Organic Contaminants in High Organic Matter Soils. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1194, 338801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, S.; Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhan, X. Microplastics Lag the Leaching of Phenanthrene in Soil and Reduce Its Bioavailability to Wheat. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, X. Adsorption of Three Bivalent Metals by Four Chemical Distinct Microplastics. Chemosphere 2020, 248, 126064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Kumar, V.; Sonne, C.; Lee, S.S.; Brown, R.J.C.; Kim, K.H. Progress, Prospects, and Challenges in Standardization of Sampling and Analysis of Micro- and Nano-Plastics in the Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhen, K.; Defu, H.; Yongming, L. Microplastics in Terrestrial Environments: Emerging Contaminants and Major Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Li, J.L.; Wang, P.D.; Hozzein, W.N.; Li, W.J. Environmental Perspectives of Microplastic Pollution in the Aquatic Environment: A Review. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Jarvis, P.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, Q.; Tian, Y. Occurrence, Removal and Potential Threats Associated with Microplastics in Drinking Water Sources. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Diehl, A.; Lewandowski, A.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Baker, T. Removal Efficiency of Micro- and Nanoplastics (180 Nm–125 Μm) during Drinking Water Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshani Igalavithana, A.; Gedara, M.; Mahagamage, Y.L.; Gajanayake, P.; Abeynayaka, A.; Jagath, P.; Gamaralalage, D.; Ohgaki, M.; Takenaka, M.; Fukai, T.; et al. Microplastics and Potentially Toxic Elements: Potential Human Exposure Pathways through Agricultural Lands and Policy Based Countermeasures. Microplastics 2022, 1, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Singh, K.P.; Singh, V.K. Trivalent Chromium Removal from Wastewater Using Low Cost Activated Carbon Derived from Agricultural Waste Material and Activated Carbon Fabric Cloth. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 135, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).