Abstract

Egg products are a convenient and safe form of eggs, possessing valuable nutritional and functional properties. The egg processing industry is responsible for the enormous amounts of biomass in the form of animal by-products (ABPs). According to EU legislation, the ABPs are under strict control from the formation to the disposal of biomass, as they carry a risk to the ecosystem and public health. For this reason, restrictions have been introduced on their use after disposal, ranging from bioactive applications in medical, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical products, as well as feed. The shells are subject to special conditions for processing and use. The by-products of egg breaking are divided into solid (eggshells and eggshell membranes) and liquid (technical albumen) by-products. The biological value is determined by the composition, which varies significantly across the by-products. In the context of the circular economy, all egg by-products contain valuable substances that can be used in food and non-food industries. First, eggshells are the leading by-product, composing 95% of the inorganic substance calcium carbonate, which, after processing, can be used in agriculture, food and feed industries, and medicine. Second, there is a liquid by-product containing proteins from the egg white and a small part of fats from the yolk. Literature data on this by-product are scarce, but there is information about its use as a feed additive, while the extracted and purified proteins can be useful in pharmacy. Egg membranes constitute only 1% of the egg mass, but humanity has long known about the benefits of collagen, keratin, and glycosaminoglycans, including hyaluronic acid, which compose this material. The processed membranes can be used as a food additive, in cosmetics, medicine, or pharmacy, just like other egg by-products mentioned above. This literature review focuses on the possible methods and techniques for processing by-products and their potential application. The literature sources in this review have been selected according to their scientific and practical applicability. The utilization of these by-products not only reduces the impact on the environment but also facilitates the creation of value-added materials.

1. Introduction

Chicken eggs are an excellent source of balanced nutrients and biologically active substances, such as proteins containing all essential amino acids and lipids rich in unsaturated fats [1]. That is why eggs play a vital role in the human diet [2]. They are one of the few foods consumed worldwide regardless of religion, ethnic group, age, season of the year, or size of the consumer’s settlement [3]. Scientific institutions in the field of health and nutrition in a number of countries (USA, EU, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, United Kingdom; WHO, Spanish Heart Foundation) recommend regular consumption of eggs as part of a healthy diet [4]. Eggs are a conventional food that plays a fundamental role beyond basic nutrition because they contain functional ingredients and biologically active compounds that may play a role in therapy and prevention of chronic and infectious diseases [5]. Eggs, together with foods of animal origin, are a significant dietary source of vitamin B12, and contain more bioavailable forms of vitamins A and D, iron, and zinc than plant sources [6]. Deficiency of these micronutrients during critical periods of life—pregnancy, lactation, childhood, adolescence, or old age—can have severe and lasting health consequences [7].

Approximately 30% of eggs for consumption in developed countries are processed into various products [2]. This percentage reaches 50% in some European Union countries [8]. Therefore, a common practice to reduce microbiological risks and product safety is heat treatment, which is a crucial step in the egg product production process [9]. Industrialized production of egg products offers economic benefits by extending the shelf life of products and facilitating their transportation and storage [10].

The fragility and perishability of eggshells pose serious challenges to the food industry, as egg quality deteriorates over time [11]. Despite all the benefits as a valuable food source, the microbiological risk to consumer health should not be underestimated, as the main role in the occurrence of foodborne toxic infections is played by Salmonella spp. [12].

In the context of the circular economy, eggs have a low carbon footprint compared to other animal products [13]. Due to these factors, annual egg production is continuously increasing. Forecasts indicate that in 2030, 89.9 metric tons of eggs will be produced, which is an increase of 63% compared to 2000, when 55.1 metric tons were produced [14].

During the last decade, a significant increase in the use of egg products in various food industries was observed [15]. However, the creation of egg products generates biomass in quantities that increase proportionally [16]. By-products from egg processing plants (eggshell, eggshell membrane, and technical albumen) are category 3 ABPs. They fall within the scope of Regulation 1069/2009. ABPs pose a risk to humans, animals, and the environment. Therefore, regulations set rules for the collection, transport, storage, handling, processing, placing on the market, import, export, and transit of raw ABPs and products derived from them. EU regulations are among the strictest in the world [17]. ABPs can be disposed of by the following methods: incineration, use as fuel without processing, processing and then landfilling, processing and use as feed, compost, biogas, or derived products, including medical, veterinary, pharmaceutical, or cosmetic products. The processing must be carried out in registered facilities by the methods described in Regulation 142/2011 [18,19].

The European Commission’s ambitious plan to make Europe carbon neutral by 2050 is a giant step towards a circular economy. Therefore, businesses will be expected to work in a closed loop, minimizing by-products and reducing their environmental impact. The “Farm to Fork Strategy” is a subset of the Green Deal that focuses on food systems and aims to use the circular economy model in the food industry [20]. The transition to a circular economy is linked to the strategy for sustainable development in the food sector. It is defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [21]. Globally, the development of adequate management strategies for a specific food by-product is considered a challenge due to the enormous quantities and the potential threat to public health [22].

The rapid development of egg production and processing, combined with the challenges inherent in the principles of the circular economy and the stability of the food chain, raises a number of questions related to the utilization of by-products. Therefore, the aim of the article is to review the currently existing practices and potential new opportunities for the utilization of egg processing by-products, which are crucial for the development of the sector.

Articles related to the use of egg by-products mainly cover solid waste in all possible applications and industries. There are no recent reviews in the global literature specifically related to the bioactive application of these wastes, including liquid wastes. The focus of this review is on the bioactive application of these wastes in food, feed, medical, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries. The article describes the composition of all by-products and covers methods and techniques for their processing into usable raw materials and products in the context of the circular economy.

2. By-Products Generated During Egg Processing

Egg products are eggs that are processed and packaged in a convenient form for use. Some examples of egg products include dried, liquid, or frozen egg whites, yolks, or egg melange, which are used in the food industry [23]. Eggs undergo the following technological operations during the creation of egg products: breaking and shelling, filtering, homogenization, pasteurization, drying, cooling, or freezing, depending on the type of product. The final stages of egg product production are packaging, labelling, and storage [24].

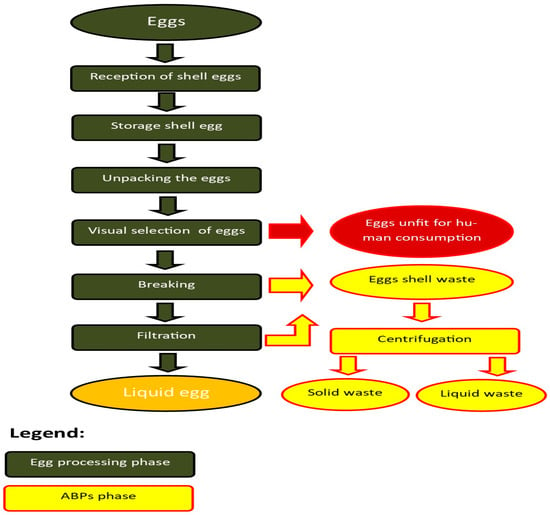

Egg by-products mainly include eggshells and membranes (solid by-products), liquid by-products from egg-breaking facilities, and eggs unfit for human consumption [25]. The production stage at which the by-product is generated is indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of egg processing (Source: GUIDE TO GOOD MANUFACTURING PRACTICE FOR “LIQUID, CONCENTRATED, FROZEN AND DRIED EGG PRODUCTS” USED AS FOOD INGREDIENTS (NON-READY TO EAT EGG PRODUCTS) https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/a94e9b3a-54a8-4581-a5fd-a4de704bdb85_en?filename=biosafety_fh_guidance_guide_good-practice-haccp-eepa_en.pdf accessed on 10 December 2025).

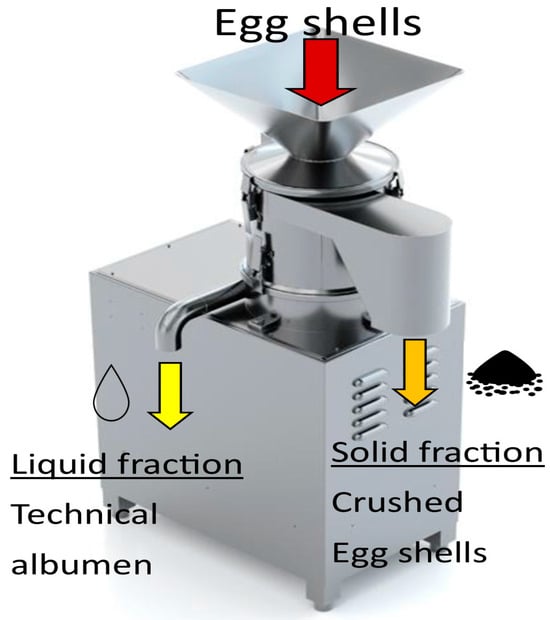

After egg breaking, the edible egg contents are separated, and the shells can be transferred via a closed conveyor to a by-product separation facility into liquid and solid fractions—crushed shells and albumen adhering to them (technical egg white). These devices are called centrifuges and consist of a sieve in which a screw moves (Figure 2) [26].

Figure 2.

Shell processing facility (Source: SANOVO Technology group SA).

Among the various by-products generated in the food industry, eggshells are among the most significant. Based on the annual global production of hen eggs of 78,949,623 tonnes and 7,770,000 tonnes in the European Union in 2018, and the fact that eggshells constitute about 10–11% of the mass of eggs, it can be estimated that at least 7,894,962 tonnes of eggshells are generated annually worldwide, of which 777,000 tonnes are in the European Union [27].

Eggshells are rich in bioactive compounds, which is why there is an increasing investment in research to develop value-added products derived from this raw material [28].

Evidence of the increased interest in the processing of eggshells and membranes is the number of patents registered for the period 2019–2022–7472 compared to the period 1999–2002–1294 [24].

3. Composition of Egg By-Products Processing

3.1. Solid By-Products

3.1.1. Eggshells (ES)

In general, 9–12% of the weight of an egg is made up of its eggshell [29]. The main function of the shell is to protect the contents of the egg and provide calcium, which is necessary for the formation of the chick’s skeleton. The ES also acts as a protective barrier against the penetration of microorganisms. It consists of several porous layers that are permeable to water and gases, allowing the embryo to breathe [30]. The cuticle, palisade, and mammillary layers are the three layers that make up the overall structure of the calcified eggshell [31]. The surface of the shell is covered with a transparent layer called the cuticle. This layer is 10–30 µm thick [32]. It consists mainly of proteins (glycoproteins) (90%) and, to a lesser extent, polysaccharides and lipids [33].

The ES is a biomineralized composite of calcite crystals embedded in a protein fibre skeleton, with a low percentage of organic matter. The mineralized shell contains about 92 to 96% of calcium carbonate. The remaining inorganic components are P2O5, Na2O, SrO, SiO2, MgO, Cl, Al2O3, Fe2O, and NiO, accounting for 1.5% of the shell composition (Table 1) [22]. The content of chemical elements in eggshells is as follows: Ca (72.6–85.7%), Mg (2.7–4.5%), Si (0.3–0.6%), P (7.0–18.1%), S (0.5–2.0%), K (0.4–0.9%), and I (2.6–3.0%) [34]. Calcium carbonate (CaCO3), the main component of the eggshell, is an amorphous crystal that occurs naturally in the form of calcite (hexagonal crystal), with low solubility in water (13 mg/L, at 18 °C) [10]. The organic matter in the shell comprises only 2% (Table 1), mainly proteins, but it has a role in crystal formation and antibacterial properties [35].

Table 1.

Biomineralized composite of eggshell [10,22,35,36].

3.1.2. Eggshell Membrane (ESM)

The ESM is a cross-linked structure located between the eggshell and the egg albumen. It is a biopolymeric fibrous network that is essential for the formation of the shell. On the one hand, it provides a non-mineralized base for the calcification of the shell from the outside, and on the other hand, it prevents the mineralization of the egg albumen from the inside [36]. The ESM has a two-layer structure; the outer part is 50 to 70 µm thick, while the inner is between 15 and 26 µm [37]. The two membranes separate at the blunt end of the egg and create a space between them called the “air cell”. This air cell is formed by the contraction of the liquid egg contents caused by the cooling of the egg after the bird has laid the egg [38]. Quantitatively, the membrane accounts for about 1.02% of the egg’s wet weight and 0.24% of the dry weight [39]. The outer layer of the membrane is firmly attached to the shell and cannot be separated from it [40].

The ESM contains 80–85% organic matter and 15–20% inorganic substances. Around 10% of the organic compounds is collagen, composed of type I, type V, and type X, and the remaining 70–75% are secondary proteins such as 10% glucosamine, 9% chondroitin, 5–10% hyaluronic acid, keratin, glycoprotein, proteoglycan, sialic acid, and 65% amino acids (9.34% proline, 9.70% glutamic acid, 8.50% cysteine) [41,42]. The content of collagen types in the outer and inner layers of the membrane differs significantly. The inner layer of the membrane contains both type I and type V collagen, but the outer layer contains only type I collagen. Another type of collagen, type X, is found in both the outer and inner layers. The ratio of type I to type V collagen is about 100:1 [43].

Collagen used as a functional supplement exists in two main forms: liquid and solid. When using soluble collagen, it is important to regulate the rate of molecular rearrangement of collagen and the intermolecular interaction in building a collagen matrix in the body. To manage these mechanisms, it is believed that the presence of substances interacting with collagen, such as glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, and phosphate polysaccharides, is important. The ESM is practically insoluble in water, as a result of a large number of crosslinks and disulfide bonds [44]. The thermal stability of the membrane is not very high, due to the content of protein fibres. Thermal decomposition of the membrane is a multi-step process, starting at about 55 °C and ending at about 120 °C. The second stage of decomposition, which may be a consequence of the thermal degradation of collagen, occurs in the range between 250 °C and 450 °C [45].

The mechanical properties of the membrane show nonlinear elasticity when applied deformation forces. The mechanical behaviour of the membrane is similar to biopolymer materials (e.g., tendons, collagen, and DNA molecules) when applied at low levels of deformation. When applied at high levels of deformation, the behaviour is like that of cellular solids [46].

3.2. Liquid By-Product/Technical Albumen (TA)

In the literature, the liquid by-product from egg-breaking installations is referred to as adherent egg white [47,48] or technical albumen (TA) [49,50]. TA is obtained in centrifuges by crushing the eggshell, followed by filtration. Regulation 853/2004 prohibits the use of material obtained in a similar way for human consumption [51]. The amount of TA depends mainly on the age of the egg, the storage temperature, and the temperature of the egg during breaking. Draining time, egg size, and the presence of a coating on the shell are of lesser importance. The measured amount of TA from manually broken eggs ranges from 2.7% to 4.1% of the egg weight [52]. According to Budžaki et al., adherent protein constitutes 10–15% of the dry matter of by-products [53].

Liquid by-product from egg processing plants contains a significant amount of protein rich in high biological value [54]. TA consists mainly of water, with protein dominating the macronutrients at 12%, and fat at 5.3% [55]. TA has a variable composition, with water content ranging from 77.5% to 82.9%. The chemical composition varies widely. Fat is between 5% and 7.2%, and protein is between 10% and 12.2%. The ash content is up to 0.71%, which indicates that the liquid is well filtered and does not contain shell residues [56].

TA has a rather different composition from that of eggs not intended for human consumption. The protein and fat content in the dry residue of eggs not intended for human consumption is almost equal, while in TA, the protein is 64.5% and the fat is 26.6% [50]. TA contains identical proteins to those of egg white [57]. Egg white contains mainly the proteins: ovalbumin (54%), ovotransferrin (12%), ovomucoid (11%), ovomucin (3.5%), and lysozyme (3.4%) [58]. Components of the yolks that have fallen into it are also found. The proteins available from the yolk are livetins and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) [59,60].

- Properties of individual egg white proteins

- Ovalbumin: This is the main protein in egg and egg white and represents about 54% of the proteins in the egg white. It demonstrates antioxidant activity after covalent binding to galactomannan or dextran through a controlled Maillard reaction, incorporation of selenium, or the polyphenol rutin [61].

- Ovotransferrin: It is known to bind and transport iron in the animal body. Ovotransferrin is present in apo- (iron-free) and holo- (iron-bound) forms [62]. It is reported to have antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other biological properties. It can be used as an iron delivery agent in the body [14,63,64]. Supplementation of ovotransferrin in the diet of mice regulates the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism, signal transduction, and the endocrine system [65].

- Ovomucin: Ovomucin has been found to possess various bioactivities such as antibacterial, antiviral, and antitumor activities, and inhibition of cholesterol absorption [66]. Ovomucin and ovomucin peptide derivatives also show antitumor activity through cytotoxic effects and activation of the immune system [64]. Ovomucin can be used as an agent to release drugs into the biological system through the mucus layer [14]. It can participate in and regulate various cellular functions, stimulate the proliferation of macrophages and lymphocytes, promote the synthesis of cytokines such as interleukin, tumour necrosis factor, and interferon, thus affecting the immune system and inhibiting tumorigenesis [67].

- Ovomucoid: In terms of quantity, it is about 11% of egg white [62]. It is well known as a “trypsin inhibitor” as each of its molecules can bind one molecule of trypsin [61]. In the food industry, the use of trypsin inhibitors derived from eggs has a higher safety profile compared to proteins derived from beef, which may pose a risk of disease [68].

- Lysozyme: Hen egg white is the richest source of lysozyme, which accounts for 3.5% of the total protein of egg white. Lysozyme kills bacteria by hydrolysing the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall of certain bacterial species, which is why it is applied as a natural antimicrobial agent [69]. Lysozyme can be used in cosmetic and pharmaceutical products. There are many lysozyme drugs on the market, such as Lisozima Chiesi® and Lizipaina®, recommended for the treatment of herpes, chickenpox, and measles, due to their antiviral activity [70]. Several studies have confirmed the tumour-inhibitory activity of lysozyme from egg white using experimental tumours. Its effect is essentially based on immunopotentiation. It also has potential immunomodulatory activity. Lysozyme from egg white is a promising agent for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. In a porcine colitis model, lysozyme has been shown to significantly protect the body from colitis [64]. It is a registered food additive with the number E 1105 [71].

- Other proteins: There is evidence of biological activity in small amounts of proteins in egg white. The flavoprotein is known as riboflavin-binding protein. Avidin binds biotin permanently and acts as an antimicrobial agent. Several proteins in egg white are characterized as “antiproteases”. Among them, ovostatin, ovoinhibitor, and cystatin are considered important. Ovostatin has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties and can be used to treat keratitis. Ovoinhibitors are a group of anti-protease proteins that inhibit serine proteases such as trypsin and chymotrypsin. Cystatin inhibits most cysteine proteases, including papain and ficin [61]. A bactericidal or bacteriostatic effect is obtained by reducing the bioavailability of vitamins (avidin), which are necessary for the growth of some microbial species, and by inhibiting microbial proteases, which are a virulence factor of infection (ovoinhibitor, cystatin) [64].

4. Processing of Egg By-Product and Applications

4.1. Solid By-Products

4.1.1. Separation of Eggshell and Eggshell Membrane

The membrane of eggshells is a natural biomaterial with many unique functional properties due to its rich protein structure. The calcified shell has a radically different composition due to its inorganic origin and does not possess the characteristics of a membrane [36]. In order to be used, the membrane must be separated from the shell before use. Shakir et al. [40] proposed three methodologies: mechanical (physical), chemical, or enzymatic.

The mechanical method in laboratory conditions involves manually peeling the membrane, although the outer membrane remains firmly attached to the shell [72]. For the industry, ES and EMS are mechanically crushed, then poured into water and allowed to separate, in order to achieve separation. The process can be accelerated by using ultrasonic treatment and separation using a sieve, achieving a purification degree of 85–95%. A yield of 96% has been achieved using cyclone airflow and air flotation by Han et al. [73]. Part of the physical methods is the batch method called “flash evaporation”. In this, a high-pressure liquid is fed into a low-pressure apparatus. Upon entry, the liquid instantly turns into steam, which causes the membrane to separate from the shell. The reported recovery is 69% [40]. The EU-funded ShellBrane project was established, the aim of which is to develop a method capable of separating the two parts and disinfecting the membrane in an easy and environmentally friendly way. The consortium has developed a prototype capable of processing 60 kg/h of solid by-product, producing a membrane and mineral shell of high quality. The system consists of three modules: a separation module using mechanical crushing, followed by a density-based system that separates the mineral shell from the membrane. The disinfection module does not use high temperature to achieve microbial stability but ultraviolet rays in order to preserve the quality of the main components found in the membrane. It is equipped with a drying module operating with cold air [74].

On the other hand, the chemical method is based on dissolving the calcium carbonate and loosening the bonds between the membrane and the shell. Given the nature of calcium carbonate, the most suitable reagents are acids such as acetic acid [75], ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) [76], or hydrochloric acid [57,77]. Mensah et al. demonstrated that acid treatment resulted in thicker and more porous membranes compared to manual removal. Furthermore, the membranes showed different wettability and swelling profiles depending on the separation method. This may be due to the effective preservation of the intact outer layer during acid treatment [76]. In addition, acetic acid treatment has been shown to improve the biocompatibility of membranes due to the introduction of carboxyl functional groups [78].

Enzymatic methods have the highest extraction rate of egg membrane among the methods, using various enzymes to cleave the peptide bonds between the fibrous bonds of the outer membrane of the eggshell and the mineralized layer of the eggshell. By using the enzymatic method, a yield of 98.9% can be achieved when using various enzyme solutions to separate the membrane from the shell. The configuration of the enzyme solution and the processing conditions are very important. In summary, the physical method of separating the shell from the membrane has the lowest extraction rate, but the cost is the lowest. The chemical method has an average efficiency, but faces problems with denaturation of the membrane protein and by-product liquid disposal. The enzymatic method has the highest efficiency in separating the membrane from the eggshell and can reduce the denaturation of the membrane protein, but it has the highest cost [73].

Of the three mentioned methods for separating membranes from shells, the enzymatic method has the highest yield—98.9%, but there is no data on its industrial application. Chemical methods are also on a laboratory scale. Mechanical separation methods, despite lower yields, are superior on an industrial scale [73,74,75,76,77].

There are also some alternative methods for separating egg membranes from shells. Microwave treatment is based on the fact that membranes have a higher water content than shells and absorb more energy from electromagnetic waves, which leads to differential heating of the two components, followed by expansion of the membranes, weakening of the physical bonds between shells and membranes, and separation [79]. Another separation technique used industrially is the passage of eggshell fragments through a series of drills in an aqueous medium heated by steam, with the separation taking place in a cyclone [80].

4.1.2. Eggshell Processing and Applications

- In the food industry

Calcium is an essential chemical element required for various metabolic functions in the human body. The intake of this mineral is important for the growth and maintenance of bones and for reducing the risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. The recommended intake is 1000–1300 mg per day, but it is difficult to meet [81]. ES are a significant source of calcium, and several recent clinical studies have investigated the effect of calcium intake from shells on the perception of pain in osteoporosis and increasing bone density [82].

According to Arnold et al., the use of 3% eggshells in the amount of flour in gingerbread does not change the appearance and aroma of the finished product. Consumption of 100 g of gingerbread with this number of shells provides 26% of the daily calcium dose [83]. ES have been used as a source of calcium in the composition of biscuits. The authors believe that the addition of 10% shells does not affect the sensory characteristics compared to the control. By consuming this food product, the consumer receives a daily calcium intake of up to 1300 mg/day, covering the daily needs [84]. In another study on the use of shells in biscuits, the dose between 5 and 10% did not affect the sensory characteristics. The dose of 5% had the highest absorbability found in vivo [81]. Hassan, in his study, indicated 6% as the desired concentration of shells in the composition of biscuits providing 1378.11 mg/100 g calcium [85]. Wesley and Renitta suggested that shells should constitute 0.8% of the ingredients of biscuits [86], but Ermiş et al. suggested 2.5% [87]. Replacing flour with up to 8% eggshell powder did not lead to changes in the structure and puffiness of crackers, and the absorption of calcium found in vivo was 44.07% [88].

Other studies used ES as a source of calcium in beef and pork sausages [89], yoghurt [90,91,92], fresh milk and kefir [93], milk tablets [94], bread [95,96,97,98,99,100], chocolate cake [101], muffins [102], butter cake [103], bean sprout milk [104], pizza, spaghetti, rice with vegetables, breaded fried meat, stew, cornmeal [105], gluten-free biscuits and crackers [106], soy milk jelly candies [107], chokeberry and cranberry juices [108], apple juice with mango, jellied fruit dessert and beef meatballs [109]. Eggshell powder in an amount of 0.2–0.5% has been used as a phosphate substitute in the production of ground pork products. The addition of natural calcium powders led to an increase in the pH of the meat products and a decrease in cooking losses compared to samples without the additive [110]. The amount of shells used in the mentioned products is small, up to 10% of the main ingredient [84]. This amount would not significantly affect the reduction in shell waste worldwide, but it is of biological origin and is more digestible than limestone [88].

According to Ningrum et al. [32], ES can be used as a natural preservative in food processing to maintain food quality and reduce the economic value of the products. ES has been used in bio-based edible film, which can delay the spoilage of steamed chicken, as observed by colour, aroma, and pH. In addition, the added roselle extract can potentially be used as an indicator of pH changes [111]. A composite coating of eggshells has been used in the storage of strawberries. The coating reduced weight loss from 60% to 30% in seven days [106].

The powdered shell can be taken orally as a dietary supplement to increase bone density and treat age-related bone loss [2]. Chicken eggshells are a possible alternative to the currently used dietary supplements from natural sources of calcium for humans and animals. The higher solubility of calcium carbonate from chicken eggshells, compared to carbonate obtained from oyster shells, and the presence of valuable mineral components (strontium, barium) make them an excellent biomaterial for the production of new dietary supplements [112]. Heat-treated shells at 125 °C for 4 h and ground to flour do not contain pathogenic microorganisms [113]. By-product eggshells can be transformed into the food additives calcium acetate monohydrate and calcium hydrogen phosphate using acetic and o-phosphoric acids [27].

- As a feed

It is recommended to use ES as a calcium supplement in animal feeds to cover the daily calcium requirements of animals [42]. In addition to calcium, eggshells contain magnesium and phosphorus, and in order to use these shells as animal feed, they must be ground into powder using a grinder [114]. Livestock in which eggshells have been used as a source of calcium are broiler chickens [54,115] and laying hens [116,117,118,119]. Adding shells to the diet improves the appearance of the shells and their strength. Eggshell meal used in the diet of growing piglets is as good a source of calcium as limestone [120]. Eggshells have been used in dog biscuits at a dosage of 2%. This amount provides 507 mg of calcium per 100 g [121].

- In medicine

Eggshells are a suitable material for the production of hydroxyapatite [122]. Microwave [123] and hydrothermal processing [124] are possible methods for processing shells into hydroxyapatite. The inorganic mineral hydroxyapatite, [Ca10 (PO4)6 (OH)2], has nano-sized crystals and constitutes about 70% of bone. Hydroxyapatite synthesized from bird shells has been used in various models of bone regeneration of dental implants in small animals. The results indicate that these biomaterials are promising candidates as bone gap fillers. Eggshell particles can be routinely applied to bone defects to promote tissue healing [125]. Eggshell powder has been used in dentistry as an abrasive material for polishing teeth [28]. Hybrid eggshell hydrogels have been used to promote bone regeneration. These gels affect macrophages and regulate osteogenic differentiation of stem cells from human dental pulp [126]. Eggshells have been used in thermoplastic scaffolds for extrusion-based 3D printing. These scaffolds are a promising alternative for applications such as bone grafts [127]. Eggshell has been used for the synthesis of various bioactive compounds that could have potential applications as antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticonvulsant agents [128].

- In pharmacy

The eggshell-based biomaterials are a promising substrate for the production of carriers for therapeutic drug and growth factor delivery [129]. Calcium carbonate particles can be used as carriers for the delivery of nanoparticles or various drugs due to their biocompatibility [130,131]. Baskar et al. have developed and evaluated an eggshell composite scaffold for dentin regeneration [132].

- Other industrial applications

Eggshells have been used in industry as a soil stabilizer [133,134], catalyst in biodiesel production [135], ingredient in cement [136,137], composite materials [112,138,139,140], and biopolymer [141].

Surface analysis of eggshell and membrane shows that these are porous materials and therefore can also be used as effective adsorbents [39]. Studies have shown the ability of eggshells to absorb heavy metals such as cadmium [142], chromium [143], lead [144], anions and phenols [145], dyes [146], hydrogen sulphide [147], and pesticides [148].

4.1.3. Eggshell Membrane

- In the food industry

Following a request from the European Commission, the Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies of the European Food Safety Authority was asked to provide a scientific opinion on egg membrane hydrolysate as a novel food under Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. The novel food under assessment is a water-soluble egg membrane hydrolysate obtained by alkaline treatment. It is a water-soluble, off-white powder containing mainly proteins. Its main constituents are elastin, collagen, and glycosaminoglycans. It is marketed outside the European Union under the trade name BiovaFlex™. The Panel concluded that egg membrane hydrolysate is safe as a food supplement at a dose of 450 mg/day. The target population is the adult population [149].

A food supplement made from eggshell membrane with the proprietary name (NEM®) is available. It contains naturally occurring membrane glycosaminoglycans and proteins. NEM® has been evaluated for safety through in vitro and in vivo toxicological studies. This supplement did not exhibit any cytotoxic or genotoxic signs. The results of these studies indicate that NEM® may be safe for human consumption [150]. Membranes have been used as an adsorbent for phenolic compounds from olive leaves. In this way, functional foods and other sources of bioactive compounds in the food industry can be created [151].

The effect of adding eggshell membrane to emulsified meat models with different concentrations of sodium chloride was evaluated. The authors investigated cooking loss, water distribution, colour, and textural properties. Emulsified meat models with membranes had less chloride and a more elastic texture than those without membranes. The addition of egg membranes increased the pH of the emulsion, reduced cooking loss, and thus improved textural properties such as firmness and elasticity in emulsified meat products with reduced salt content [152]. Hydrolysed eggshell membrane has been used in the composition of dried meat products. The membranes significantly enhanced the browning of pork sausage meat and facilitated the formation of nitroso myoglobin. Furthermore, 70% ethanol extract of hydrolysed eggshell membrane effectively reduced Fe3+ and lowered the redox potential [153].

Bird egg membranes can be used in biological tissue engineering to culture meat in the laboratory. Jang and colleagues used membranes as a scaffold on which they successfully attached bovine muscle stem cells [38].

An edible food coating based on hydrolysed egg membrane and chitosan in a 1:1 ratio has satisfactory strength and low water permeability [154]. Another food coating was created from egg membrane, soy isolates, and eugenol, improving antimicrobial activity. The film is water-resistant and has a UV barrier [155].

Demir et al. describe soft gel capsules from a solution of egg membranes. The separation of the membrane from the shell was performed by 100 mM EDTA 100 mM at a hydro modulus of 1:20. The content of membrane protein in the gel capsules is up to 1.45 mg/g [156].

Lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus plantarum have been used for eggshell membrane fermentation to produce functional and bioactive protein hydrolysates. Protein hydrolysates obtained by fermentation of poultry egg membranes can potentially be incorporated into functional foods and food supplements because they show remarkable bioactive properties, such as reducing capacity, antioxidant properties proven by DPPH reagent, and inhibition of angiotensin I-converting enzyme [157].

Eggshell membrane hydrolysate and tannic acid were obtained by covalent and non-covalent interactions. The results showed that the obtained hydrolysates can scavenge free radicals and chelate Fe2+. They were used in the composition of mayonnaise and were found to reduce the rate of lipid oxidation [158].

A nanocomposite edible film based on hydroxyapatite with eggshell membrane incorporated with anthocyanins was developed. The coating is suitable for food packaging, which can preserve the quality of food during storage or delivery [159].

Antimicrobial composite of egg membranes and silver ions can potentially be used as a bio-based disinfectant for food contact surfaces in food manufacturing facilities [160].

An important property that the membrane must possess when used as a functional additive is the lack of cytotoxicity and mutagenicity. It has been found that human cells are not damaged by the application of 100 micrograms of ESM [40].

- In medicine

Eggshell membrane (ESM) is a natural biomaterial that has attracted increasing attention in the biomedical field due to its unique properties and composition. It also has good biodegradability and biocompatibility [161].

Osteoarthritis is the most common chronic joint disease that significantly affects patients’ ability to function and their quality of life. Eggshell membrane has been tested as a natural therapeutic agent for joint and connective tissue diseases and has been reported to exert some beneficial effects on joint pain, stiffness, and cartilage regeneration induced by excessive exercise [43].

A clinical study was conducted with 60 healthy postmenopausal women divided into two groups. Consumption of the commercial product, natural eggshell membrane (NEM®) partially hydrolysed, 500 mg once daily for two weeks, rapidly improved recovery and reduced joint stiffness caused by exercise, as well as reduced discomfort immediately after exercise [162]. The same author described the effect of taking the same supplement, Natural Eggshell Membrane (NEM®), at 500 mg once a day in another clinical trial. After 30 days of taking the supplement, recipients reported that the supplement improved flexibility and reduced shoulder pain [163].

Another double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigated the therapeutic effect and safety of a water-soluble eggshell membrane hydrolysate using a dietary supplement (BiovaFlex, 450 mg daily). Researchers monitored the knee function, mobility, and overall health of 88 patients with osteoarthritis. Subjects were advised to stop all use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or over-the-counter pain relievers for at least 14 days prior to the first dose. This study found that in those participants who had difficulty moving due to joint discomfort, the product significantly increased physical capacity and walking ability, and distance travelled. The membrane group also experienced a greater reduction in joint stiffness than the placebo group [164].

In a larger, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 150 male and female volunteers, aged 40–75 years, diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis, took processed egg membrane. For 12 weeks, subjects received a daily capsule containing either 300 mg of egg membrane or a placebo. The results showed long-term improvement in patients and proved that the membrane extract successfully relieves knee pain in osteoarthritis and contributes to daily improvement in life activities [165].

In a placebo-controlled study, 100 participants aged 40–75 years with knee pain took NEM® (500 mg egg membrane/capsule). Oral administration of NEM® for 12 weeks reduces pain and stiffness and improves physical function in patients with early-stage osteoarthritis of the knee [166].

In their review, García-Muñoz et al. reviewed seven clinical trials conducted between 2009 and 2022 on the use of egg membranes in osteoarthritis. They concluded that there was compelling evidence to support the efficacy of the membranes in reducing knee pain and improving function in patients with osteoarthritis [167].

In China and Japan, chicken eggshell membranes have been used to bandage skin wounds for over 400 years [168]. The fibrous and porous structure of the membranes, resembling the extracellular matrix, and the protein content enhance the adhesion and proliferation of skin cells, thereby accelerating the wound-healing process [169]. Wound healing is an extremely complex series of biological events involving homeostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and skin remodelling. The early phase of the wound healing process is crucial for providing the extracellular matrix foundation, for cell regeneration, and for reducing scar formation. Dysregulation of the wound healing process leads to chronic tissue damage or permanent scarring, which can cause various health problems, including increased morbidity and mortality. In addition, excessive scar formation impairs skin structure and function [78]. The primary role of a dressing is to prevent infection during wound healing, but it is also advantageous that the dressing reduces wound necrosis, controls wound moisture, facilitates exudate removal, and relieves pain [170].

Choi et al. investigated the effects of modified egg membrane cross-linked with acetic and citric acid carboxyl groups on skin wound healing in rats. The wound closure rate was significantly higher in the modified egg membrane-treated group than in the natural membrane-treated or untreated groups as early as three days after surgery. Furthermore, the modified egg membrane-treated group showed a healed epithelial layer, with a densely regenerated dermis. Overall, these results suggest that the modified egg membrane significantly accelerates skin wound healing, promoting re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation in the early stages of wound healing [78]. Egg membranes are a suitable material for wound healing. Membranes have been used in two clinical cases: a three-year-old female with a severe burn of the leg and a three-year-old female with a burn of the elbow. In both cases, satisfactory epithelial tissue recovery was observed [161].

Ahmed et al. evaluated the potential of dried egg membranes for wound healing in mice. Using a mouse excisional wound splinting model followed by histopathological evaluation, they concluded that dried egg membranes are a biocompatible and non-cytotoxic biomaterial that has great potential for development into a cost-effective wound healing product [171,172].

Two types of wound dressing coatings, chitosan and chitosan with egg membranes added, were evaluated for medical applications. The membrane coatings were more stable in the solution used, with suitable acidity for wound healing, and significant antibacterial activity of the films. The swelling property of the membranes significantly contributes to the increased capacity to absorb more nutrients to promote fibroblast proliferation and migration. The authors believe that egg membrane coatings show high potential for use in wound dressings for humans and animals [173].

Webb et al. created a composite biopolymer film containing chitosan, egg membrane, membrane solutes, and plant extracts. The resulting acidity is suitable for wound healing, and the film with 5% plant extract inhibited almost all growth of E. coli in liquid cultures. The incorporation of egg membrane solutes and plant extracts into a film of chitosan and egg membrane provides a promising and novel method for making a dressing for chronic wounds that has strong antibacterial properties [170].

Avian eggshell membrane is a versatile biomaterial with a chemical composition and structure that can be used for bone regeneration. It contains molecules of biomedical interest, such as collagen, hyaluronic acid, and dermatan sulphate. It also has a mesh structure that behaves mechanically similar to collagen systems in the body, such as tendons. These properties resemble those of the collagen matrix of bone, making eggshell membrane a potential basis for the development of bone scaffolds [174]. It is necessary to combine eggshell membrane with other materials that could provide a microscopic and gradient structure with good mechanical properties [175].

Ma et al. extracted proteins from egg membranes by centrifugation after extraction with 3-mercaptopropionic acid. The authors noted the presence of specific proteins in the egg membrane with growth factors possessing potent osteoinductive properties that can stimulate the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts and promote the formation of mineralized tissue. The resulting soluble egg proteins showed good biocompatibility, highlighting their potential as reliable biomaterials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine [176].

Adali et al. designed chitosan/silk fibroin/eggshell membrane hydrogels and analyzed the cell proliferation activity of human chondrocyte cells. The hydrogel supported good adhesion, growth, and differentiation of chondrocyte cells under standard culture conditions. The results suggest that the hydrogels could potentially function as a promising cartilage substitute for tissue engineering applications [177].

Alotaibi et al. investigated the biological properties of eggshell membrane, including an in vitro cell proliferation assay with human gingival fibroblasts. According to the authors, the avian membranes could serve as viable alternatives to commonly used barrier membranes in guided bone regeneration [178].

Processed eggshell membrane powder was used in the 3D scaffold. Mechanical tests revealed that eggshell membrane/collagen-based scaffold increased the mechanical stiffness of the scaffold compared to a pure collagen scaffold. This makes them a promising low-cost, natural biomaterial for use in combination with collagen as a scaffold for 3D tissue engineering to improve mechanical properties and promote cell adhesion and growth of regenerating cells [179].

Raw egg membranes obtained by hand peeling from the shell have been used for symblepharon, burns of the eyeball, corneal ulcers, and iritis. In the case of symblepharon, after ten days, the eyeballs and eyelids of the patients were smooth, without adhesions. Similar results have been observed in patients with burns of the eyeball. The use of membranes in patients with corneal ulcers did not cause pain or irritation during treatment. The ulcers healed adequately after two weeks. Finally, the membranes were used in iridectomy for recurrent iritis and resulted in effective wound healing without infection [169]. Due to the high transparency of the egg membrane biomaterial, preparations of this raw material can be used in a number of regenerative medical and/or biotechnological applications, such as wound dressing for eye injuries [76].

Hydrolysates of egg membranes treated with the enzymes alkalise and protease have ACE inhibitory activity, as well as antioxidant activity [180]. Inhibitory activity against angiotensin-I-converting enzyme was also found in soluble peptides produced from hydrolysed eggshell membrane. The hydrolysis was performed with recombinant protease [181]. Egg membranes were used as an arterial patch in a rat aortic angioplasty model [182].

The use of membranes in medical fields such as tissue engineering and wound healing is in its infancy. It is necessary to clarify the biocompatibility, microstructure, controllable biodegradability, and suitable mechanical properties of membranes when used in 3D scaffolds and tissue engineering [179]. Wound healing is a complex and dynamic biological process. The materials used in the dressing must have high biocompatibility, antimicrobial activity, fluid absorption, and moderate physical and mechanical strength. Further studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of membranes for these purposes [173].

- Membrane product extraction

The global market for collagens and hyaluronic acid-based biomaterials is expected to reach ~6.8 billion USD by 2026. Key applications include cosmetics, healthcare, food, and beverages. Technological advancements and the increasing demand for cosmetic and anti-ageing products are believed to contribute to the growing demand for collagen and hyaluronic acid-based products [183]. The high insolubility of egg membrane proteins can be caused by inter- and intramolecular disulfide bonds of the proteins. Therefore, the reduction in the high insolubility of the membranes can be achieved by breaking the disulfide bonds in the proteins. The methods described in the literature can be divided into the following groups: mechanical, combined chemical and enzymatic [73].

Membrane hydrolysis methods with strong acid or strong alkali solutions are usually combined with high-temperature incubation under high-pressure conditions. However, these reactions require additional neutralization to make the product usable. Many of the bioactive components can be destroyed by these violent processes, leading to low yields of recycled nutrients for further application [16]. A method called “steam explosion,” based on steam treatment and explosive decompression, has been used to recover membranes and convert them into high-value antioxidants. A reduction in disulfide bonds and the level of cysteine/cystine interaction have been found. Compared to the non-steam-treated hydrolysate, the authors report an increased antioxidant capacity and potential for use in foods [184].

Enzymatic hydrolysis is a more selective method in the production of peptides with specific bioactive activity, while alkaline hydrolysis can break the chemical bonds in the eggshell membrane and release the bound peptides. Combining these two methods allows the production of higher-quality final products. Enzymatic hydrolysis better preserves the structure and activity of the peptides, while alkaline hydrolysis contributes to their complete release [80]. The enzymes used are alkalise, tryptase, papain, and trypsin (Table 2). Chemical treatment can be carried out by changing the pH, by ultrasound, by sodium acetate, or by ethanol with the addition of hydrochloric acid [185].

- Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)

Proteoglycans are biological molecules composed of a specific core protein substituted with one or more covalently linked glycosaminoglycan chains (Table 2). Glycosaminoglycans are linear, highly negatively charged polysaccharides composed of a variable number of repeating disaccharide units. Based on the structure of their repeating disaccharides, GAGs can be classified into four groups: hyaluronan, chondroitin sulphate, keratan sulphate, and heparan sulphate. Hyaluronic acid is the simplest GAG, containing neither a sulphur group nor is it linked to a core protein. In shell membranes, hyaluronan is the most abundant GAG component (703.52 ± 194.49 µg per gram of membrane), followed by chondroitin sulphate, keratan sulphate, and heparan sulphate [186].

- Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a glycosaminoglycan found in the extracellular matrix of soft connective tissues. It is a highly hydrated component of connective, epithelial, and nervous tissues. Its high-water absorption rate provides high viscosity of HA solutions at lower concentrations. High molecular weight HA solutions are very viscous and exhibit non-Newtonian flow behaviour [187].

The main biological functions of hyaluronic acid include maintaining the viscoelasticity of connective tissue and controlling its hydration. Its viscous solutions act as a lubricant in moving parts of the body, e.g., joints. It promotes wound healing, has bacteriostatic and antiseptic properties, protects tissues from the penetration of high molecular weight substances, and regulates the migration of phagocytes into inflammatory areas [188].

Table 2.

Enzymatic methods for egg membrane processing to extract HA.

Table 2.

Enzymatic methods for egg membrane processing to extract HA.

| Enzymes Used | Temperature Conditions | Other Conditions | Yield | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin, Pepsin, and Papin | Trypsin 37 °C Pepsin 40 °C Papin 60 °C | pH 8.0 pH 3.0 pH 7.5 | ~4–4.5% | [185] |

| Bromelain and Papain | 60 °C | pH 8.0 | [189] | |

| Papin | 60 °C | 0.5 M NaCl | 5.483 mg/g membrane | [190] |

| Keratinase | 55 °C | Sodium sulphite | 6.4% | [16] |

Cai et al. [191] used subcritical water to extract nutrients from egg membranes. Hydrolysates obtained at 180–210 °C showed protein content (40.57 ± 2.40 mg/g), peptides (20.36 ± 0.43 mg/g), hyaluronic acid (8.19 ± 0.34 mg/g), and chondroitin sulphate (11.68 ± 0.76 mg/g).

- Collagen

Crude collagen is a biological product with an ever-increasing demand for the production of skin grafts and tissue replacement products, dental implants, and corneal restoration. Purified collagen sells for up to $1000 per gram. Bovine and porcine hides and skins, as well as their bones, are the main sources of collagen used in the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and leather industries. The outbreak of mad cow disease has led to concerns among consumers of bovine gelatine due to the not entirely confirmed hypothesis that the infectious agent can be transferred from animals to humans [192].

Ya Chu Lien et al. [16] used the enzyme keratinase, which is a broad-spectrum serine protease that belongs to the subtilisin family. The best conditions for membrane hydrolysis with keratinase included the addition of 0.650 µM enzyme and 50 mM sodium sulphate, followed by incubation at 55 °C for 3 h (Table 3). This resulted in a weight ratio of product– sodium sulphate–membrane of 1:120:600. The amounts of glycosaminoglycans and sulphated glycosaminoglycans in the hydrolysate were quantified as 6.4% and 0.7%, respectively. The data confirmed that the enzymatic hydrolysate of egg membranes was rich in collagen peptides with molecular weights of around 963–2259 Da. Among them, type X collagen was the main species. The results indicated that the keratinase-hydrolysed membrane could produce bioactive substances suitable for therapeutic applications and nutritional supplements.

Bioactive peptides from eggshell membranes under alkaline and enzymatic treatment conditions resulted in a hydrolysis level of 14.23%. Specifically, 1.25 N NaOH and 2.4 L of alkalise protease were used [80]. A collagen facial spray with a membrane content of 30% was created. According to the authors, the spray contains the necessary daily amounts of collagen for the skin [193]. Collagen from membranes was used to make a bio-composite with hydroxyapatite for application in bone tissue [194].

Table 3.

Methods for processing egg membrane for the purpose of extracting collagen.

Table 3.

Methods for processing egg membrane for the purpose of extracting collagen.

| Substances Used | Temperature Conditions | Other Conditions | Yield | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalise Trypsin | 17.25 mg/mL 3.28 mg/mL | [195] | ||

| Keratinase | 55 °C | 50 mM Sodium sulphite | [16] | |

| Acetic acid Citric acid | Acid concentration 0.5 M | 507 mg/100 g-dry sample 495 mg/100 g-dry sample | [192] | |

| Acetic acid | 5–25 °C | Acid concentration 0.1–0.9 mol/L | 8.35% | [196] |

| Papain | 60 °C | 0.5 M NaCl | 5.483 mg/g membrane | [190] |

- In cosmetics

Collagenase is an enzyme that hydrolyses collagen, thereby causing loss of skin hydration and elasticity, leading to the formation of wrinkles. In skin exposed to ultraviolet light, an increase in the production of collagenase and elastase is observed, with the same adverse effects on the skin [197]. Chronic UVB irradiation causes skin dryness due to a decrease in the content of hyaluronic acid, which is considered critical for skin hydration due to its water-holding capacity. Furthermore, UVB irradiation has been reported to reduce HA synthesis [198]. Egg membranes possess inhibitory activity towards collagenase and elastase. This ability of eggshell membrane indicates that it has potential for practical application in anti-wrinkle cosmetics [197].

Egg constituents known to have antimicrobial properties and currently available on the market include lysozyme, conalbumin, avidin, and lactoferrin. Petri dishes containing eggshell fractions at concentrations of 10 mg/dish and 20 mg/dish showed antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but their antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria was more pronounced. In summary, eggshell membrane hydrolysates showed high levels of antimicrobial activity against several bacteria, including S. aureus, indicating that they could have practical applications in cosmetic acne creams [197].

The egg membrane was processed into a powder form with a nanosize (50 nm). With various active additives, it has been applied in the ingredients of cosmetic preparations: cream, body lotion, face mask, gel, and foundation powder. The cosmetics were used in a four-week study on human skin, assessing the condition of wrinkles, the effect on acne, dry and brittle skin, hydration, and smoothing of the dermis. From the analysis of the results, it is proven that there is an increase in cell activity and collagen production, as well as preventing skin ageing. Skin moisturizing is also observed in patients using cosmetics with the addition of egg membrane [199].

Hyaluronan contained in the membranes has moisturizing properties and a high water-holding capacity, especially for human skin. Ohto-Fujita and colleagues evaluated the effect of a 1% solution of egg membranes in the form of a moisturizing lotion. Participants applied the preparation to the skin of the forearm and upper arm for 12 weeks twice a week. Using skin biophysical measurements, they reported a significant increase in skin elasticity. The authors also applied a preparation containing egg membranes at a concentration of 2% to women in the area of “crow’s feet” wrinkles. The sample was applied three times a day for two weeks, three drops each. Binarized images of the wrinkles showed that this area decreased after treatment [168].

Hydrolysed ESM contains a number of bioactive components that may affect the physiology and appearance of hair, skin, or nails. Possibly due to the high concentration of GAGs and amino acids, oral supplementation of eggshell membrane has been associated with improvements in skin elasticity and appearance. The effects of an oral supplement of hydrolysed water-soluble eggshell membrane (BiovaBio) on the appearance of the skin were evaluated. For this, 126 healthy subjects aged 35–65 years were divided into two groups. A total of 88 subjects were instructed to consume 450 mg of the test product, and the remaining 88 were given a placebo once a day. The study demonstrated that the product under study had physiological and statistically significant effects for a positive effect on the skin and hair in healthy middle-aged adults [200].

A total of 85 women aged 25–60 years with dry facial skin and crow’s feet were given finely ground dried and sterilized egg membrane 200 mg in 650 mg tablets under the trade name Ovoderm®-AS. The study was randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled for a period of 12 weeks. Egg membrane reduced the appearance of wrinkles, and the skin improved elasticity, density, and hydration, while reducing roughness and trans epidermal water loss, compared to placebo [201].

An anti-ageing cream, containing egg membrane collagen and honey, was tested on experimental animals. The physical properties of the product were evaluated, and the results showed that it is suitable for use in cosmetics [202].

Pasarin et al. [80] combined alkaline and enzymatic hydrolysis to obtain peptides from eggshell membranes. These peptides have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and moisturizing effects that help improve skin condition. Oral administration of membranes restored moisture in the dorsal skin tissue of mice. This was due to reduced transepidermal water loss and decreased expression of hyaluronic synthase mRNA induced by ultraviolet irradiation. In addition, collagen degradation by collagenase was inhibited [198].

Eggshell membranes and quercetin are a possible combination for the treatment of skin hyperpigmentation due to the inhibition of tyrosine and the reduction in melanin production [203].

- Other industrial applications

The applicability of by-product eggshells for the removal of copper (Cu) heavy metal in aqueous solution has also been studied. The prepared matrix of membranes and polyvinyl difluoride shows removal of copper up to 99% from the solution [204]. Membranes have been used as absorbents of azo dye from the textile industry [205], organic pollutants and methylene blue dye [206], divalent nickel ions [207]. Membranes have been used as a carrier of laccase in the immobilization of enzymes [208].

4.2. Liquid By-Product (Technical Albumen)

4.2.1. As a Feed

Spray-dried eggs can play a role in the nutrition of young pigs and are considered an important dietary component, like dairy products, because they are a source of immunoglobulins [209]. The nutrients in these products are easily digestible, have an excellent balance of amino acids, are rich in fat content, and have high metabolizable energy. The contained lysozyme antimicrobial proteins can damage the cell wall of bacteria. This reduces the concentration of intestinal pathogens, which is important for physiologically immature weaned pigs [210]. DeRouchey et al., Figueiredo et al., James et al., and Zimmerman used spray-dried eggs unfit for human consumption in the composition of pig feed. James et al. found that despite the excellent amino acid composition of the eggs, satisfactory weight gain of the animals was not achieved during the test period compared to the control. Zimmerman observed that the growth-to-feed ratio decreased with increasing egg concentration in the diet. He attributed this to the lower availability of the amino acid lysine and hydrolytic changes in the protein fraction [211,212,213,214]. It is known that eggs contain some inhibitors that interfere with the absorption of nutrients, for example, protein avidin, which binds to biotin. Dried eggs are also a trypsin inhibitor, with 1 g of them inhibiting 40 mg of trypsin. These inhibitors are thermolabile, and in order to eliminate these properties, heat treatment is necessary. Schmidt and colleagues found in an in vitro study that the digestibility of proteins of dried TB after moist heat treatment above 100 °C (i.e., autoclaving) increases by 30–40% compared to the control treatment [50].

Norberg et al. studied the growth of ducks fed with by-product eggs. They concluded that spray-dried eggs are an excellent source of energy for poultry, not only because of the protein content but also because of the easily digestible fat [215].

Dried egg whites and melange have been used as a binder in canned pet food. Their addition was evaluated at concentrations of 0, 2, 4, and 6%. The use of egg products in higher amounts increased firmness, protein content, and texture [216].

The addition of dried eggs not intended for human consumption to broiler diets was evaluated at concentrations of 0.15% and 0.3% by weight of the feed. The results indicate that the immune response of broiler chickens can be affected by the use of dried eggs. Body weight and feed efficiency were also increased compared to the control. Carcass characteristics were also positively affected, especially at a concentration of 0.3% [217].

Spray drying is a common method for TA recovery. However, the high investment and operating costs do not correspond to sustainable development. Alternative processing methods that are more environmentally friendly are needed. Saraliev et al. used acid-thermal coagulation as an approach for pre-dehydration of the product before drying to reduce fuel consumption. The transformation of TA to a solid material helps to use more affordable dryers [55,56].

Twin-screw extrusion was used to produce animal feed with liquid egg by-product and almond shells. A formula with 30% egg raw material had nutritional properties similar to grain silage with good microbial stability and a satisfactory shelf life [218].

Liquid egg by-product was used as a binder for the production of organic biofertilizers from agricultural and food by-products [219].

Technical protein mainly contains egg white proteins, which exhibit various biological activities. Two approaches are possible in the use of egg white:

- (a) fractionation and extraction of individual egg proteins;

- (b) use of bioactive peptides obtained by enzymatic hydrolysis [15].

4.2.2. Extraction of Individual Egg Proteins

- Methods for extracting egg proteins

Li Z and colleagues summarized the techniques for the extraction of egg proteins. They include precipitation, chromatography (ion exchange, gel filtration, affinity, and adsorption), electrophoresis, membrane chromatography, aqueous two-phase systems, and molecular imprinting [68].

There is a method for purifying ovalbumin from eggs. This method involves only two steps: polyethylene glycol precipitation and isoelectric precipitation. By optimizing the separation parameters, the purity of ovalbumin is over 95%, and the yield is 46.4% [220].

An attempt was made to extract lysozyme, ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, and ovomucoid from egg white proteins by two-step ion exchange chromatography. The purity of lysozyme, ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, and ovomucoid was 87%, 70%, 80% and 90%, respectively. From 187.27 mg of egg white protein, the following amounts of proteins were extracted: 4.5, 54.3, 5.2, and 4.5 mg [221].

Lysozyme and ovalbumin were extracted using Amberlite FPC 3500 ion exchange resin. The yield of lysozyme and ovalbumin was >88.9% and >97.7%, respectively, and the purity of lysozyme was >97% and that of ovalbumin was 87% [3]. Using the same technology, the proteins lysozyme, ovalbumin, ovomucin, and ovotransferrin were successfully separated. The recovery of ovomucin and ovalbumin was >98%, as well as recovery of ovotransferrin and lysozyme was >82% for both laboratory and large-scale preparations. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting of the separated proteins, except for ovomucin, showed >90% purity. ELISA results showed that the activity of the separated ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, and lysozyme was >96% [63].

Ovotransferrin was extracted from egg white using its metal-binding property. The extraction was carried out with controlled pH and the addition of ethanol. The maximum yield obtained of ~85 ± 2.5% was calculated based on the theoretical value of 934 mg ovotransferrin in 100 mL of 1.5 × diluted egg white solution [222].

A method for the isolation of lysozyme from hen egg proteins was developed. Lysozyme was isolated after thermal denaturation of proteins by changing the pH value of the medium, followed by neutralization, dialysis, and further purification by gel chromatography on Sephadex G-50. The purity of the enzyme and molecular mass were determined using SDS-electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. The achieved yield was 3.2 ± 0.2% and the bacteriolytic activity was 22,025 ± 1500 U/mg. According to the electrophoresis, the isolated enzyme was characterized by a high degree of purity (~95–98%) [223].

Ji and colleagues developed a protocol for the sequential extraction of 5 egg proteins using resin adsorption, pH adjustment, salt/ethanol precipitation, and ultrafiltration. The purity of lysozyme, ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, ovomucoid is over 90%, and ovomucin is over 75%. The yield of lysozyme is over 90%, of ovotransferrin is over 80%, and of the other proteins is over 70% [224].

Soluble ovomucin with high purity (99.13%) was isolated with a good yield (3.02 g/kg fresh egg white) by two-step precipitation with CaCl2 and MgCl2, followed by gel filtration chromatography [225].

Lysozyme from avian egg white was successfully purified using stirred fluidized bed ion exchange chromatography. The purity is over 93%, and 1 g of protein requires over 40 g of egg white [226].

4.2.3. Peptides Obtained by Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Bioactive peptides are fragments of proteins obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis. Hydrolysis leads to the breakdown of the quaternary and tertiary protein structure and a decrease in molecular weight. The hydrolysates subsequently interact with the corresponding receptors of the body to regulate its functions. Bioactive peptides cause various effects on health by acting like human hormones on the circulatory, digestive, nervous, and immune systems. The specific activity of peptides is influenced by the type and location of amino acid residues in their structure [15]. Current trends focus on the modification of egg white proteins using new techniques that improve protein functionality and nutrient digestibility [227].

- Bioactive properties of egg whites and hydrolysates

The pathological condition characterized by the accumulation of free radicals and/or reduced antioxidant defence is called oxidative stress. Cellular damage caused by oxidative stress is mainly the result of the action of free radicals, which negatively affect lipids, proteins, and DNA, subsequently contributing to various human diseases. In living organisms, there is a delicate balance between the processes involving free radicals and the protective antioxidant system [228]. Bioactive compounds with antioxidant properties are a solution to this problem and have a potential therapeutic role, compensating for the adverse changes resulting from the action of free oxygen radicals [229].

Oxidative stress has been linked to the causation of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer [230], Alzheimer’s disease [231], and Parkinson’s disease [232]. The mechanism of antioxidant hydrolysates and peptides can manifest as free radical scavenging, transition metal chelation, reduction in hydroperoxides, enzymatic elimination of specific oxidants, or inhibition of lipid peroxidation in food systems [233], white protein is one of the most important sources of antioxidant peptides from food sources [234].

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular and renal diseases. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) (EC 3.4.15.1) plays a critical physiological role in increasing blood pressure; therefore, inhibition of ACE activity may result in a general antihypertensive effect [235]. ACE inhibitors are a class of drugs that are used to treat various diseases, most notably cardiovascular disease. The main side effect associated with ACE inhibitors is low blood pressure (hypotension). Some uncommon side effects of ACE inhibitors include dry cough, inflammation of the eyes, throat, or tongue, hives, irregular heartbeat, dizziness or fainting, headache, and worsening kidney function [236]. Egg white peptides have good antihypertensive activity, are safe, and can be used as an alternative for treating hypertension or slowing the progression of the disease, without side effects [237].

Egg white peptides have also been reported to inhibit enzymes associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV, EC 3.4.14.5) and α-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.1), as well as aminopeptidase N (APN, EC 3.4.11.2) [238].

Egg protein hydrolysates show not only antibacterial, but also antiviral, antifungal, and antiparasitic activity. Their antibacterial effect is based on the following bactericidal and bacteriostatic mechanisms: destruction of the bacterial cell wall, binding of free iron, and inhibition of enzymes [65].

Ho and colleagues developed an egg protein hydrolysate treated with the enzymes protease A and papain. The degree of hydrolysis of the product is 30.11% and when added at a concentration of 1% to egg products, it improves the foaming properties and the appearance of the resulting cake [239].

An antimicrobial peptide derived from ovalbumin was synthesized by Fmoc-solid-phase peptide synthesis and was found to have potent antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi [240]. A novel antimicrobial peptide (OVTp12) purified from the hydrolysis of ovotransferrin by ion-exchange chromatography and gel filtration showed effective antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The peptide OVTp12 may be a promising antimicrobial agent for food or pharmaceutical preservation [241]. Egg white hydrolysates administered at a concentration of 38.5 mg/kg body weight to rats increased antioxidant activity by increasing glutathione peroxidase activity and decreasing glutathione levels. It also reduces hepatotoxicity by reducing the levels of serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and lipid peroxidation products—specifically, malondialdehyde [242].

Egg white protein hydrolysates were produced by hydrodynamic cavitation. The enzyme papain was used under conditions (pH 7.5, processing time—90 min, temperature 50 °C) for 15 min [243].

Numerous techniques for protein extraction and enzymatic treatment of egg white are found in the scientific literature. These techniques can also be applied to liquid TA waste, because it contains proteins, valuable proteins like egg white, despite the altered ratio [55,57]. Liquid waste is an ABP category 3. European legislation allows its processing into medicinal, cosmetic, and veterinary medicinal products, but safety for the consumer, as well as public and animal health, must be guaranteed [18].

5. Conclusions

Egg processing waste is a significant concern for the food industry, with the potential for complete recovery. The focus of this review was the bioactive potential with an emphasis on food, pharmaceutical, medical, and cosmetic applications, as well as concluding with the most recent knowledge. The utilization of eggshells was already extensively reported. Due to its inorganic nature, the shell has a low biological value. On the other hand, the utilization of membranes is a developing scientific area with direct practical implementation. Medicine, pharmacy, and cosmetics successfully use the biological potential of egg membranes, with finished and registered products. Lastly, the scarce information about the sustainable reuse of technical albumen highlights the need for further study. Continuing research on the extraction of these valuable components and bringing them to an industrial scale is an opportunity to make new drugs with fewer side effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B. and D.V.-V.; validation, S.D.; investigation, P.S. and N.K.; data curation, P.S. and N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. and N.K.; writing—review and editing, D.B. and D.V.-V.; visualization, P.S.; supervision, S.D.; project administration, N.K.; funding acquisition, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund, grant number KP-06-M76/2 from 5 December 2023 entitled: Opportunities for utilizing waste from egg processing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ES | Eggshell |

| ESM | Eggshell membrane |

| TA | Technical albumen |

| ABP | Animal by-products |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| GAG | Glycosaminoglycan |

References

- Vitkova, T.; Enikova, R.; Karcheva, M.; Saraliev, P. Eggs in the human diet-facts and challenges. J. IMABs 2024, 30, 5314–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.A.; Wu, L.; Younes, M.; Hincke, M. Biotechnological applications of eggshell: Recent advances. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 675364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeyrathne, E.N.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Ahn, D.U. Egg white proteins and their potential use in food processing or as nutraceutical and pharmaceutical agents—A review. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 3292–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Molnár, J. The role of eggs as an important source of nutrition in human health. Int. J. Food Sci. Agric. 2021, 5, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.M.; Anton, X.; Redondo-Valbuena, C.; Roca-Saavedra, P.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Lamas, A.; Cepeda, A. Egg and egg-derived foods: Effects on human health and use as functional foods. Nutrients 2015, 7, 706–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, T.; Gardner, C.D.; Herrero, M.; Iannotti, L.L.; Merbold, L.; Nordhagen, S.; Mottet, A. Friend or foe? The role of animal-source foods in healthy and environmentally sustainable diets. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda García, A.M.; Fracassi, P.; Scherf, B.D.; Hamon, M.; Iannotti, L. Unveiling the Nutritional Quality of Terrestrial Animal Source Foods by Species and Characteristics of Livestock Systems. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechevalier-Datin, V.; Guérin-Dubiard, C.; Pasco, M.; Gillard, A.; Le Gouar, Y.; Musikaphun, N.; Nau, F. Technological advances in egg product processing with reference to allergenicity. In Proceedings of the XVIIth European Symposium on the Quality of Eggs and Egg Products, Bergamo, Italy, 15–19 September 2013; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-01595727 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Vitkova, T.G.; Enikova, R.K.; Stoynovska, M.R. Medical evaluation of the potential biological and chemical dangers in high-risk foods. J. IMABs 2021, 27, 3924–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; Benelli, P.; Amante, E.R. A literature review on adding value to solid residues: Egg shells. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 46, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Min, F.; Meng, X.; Chen, H. The Effect of Lipids on the Structure and Function of Egg Proteins in Response to Pasteurization. Foods 2025, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez-Aguirre, D.; Niemira, B.A. A review on egg pasteurization and disinfection: Traditional and novel processing technologies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 756–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]