Risk Assessment of Biogas Production from Sugarcane Vinasse: Does the Anaerobic Bioreactor Configuration Affect the Hazards?

Abstract

1. Introduction

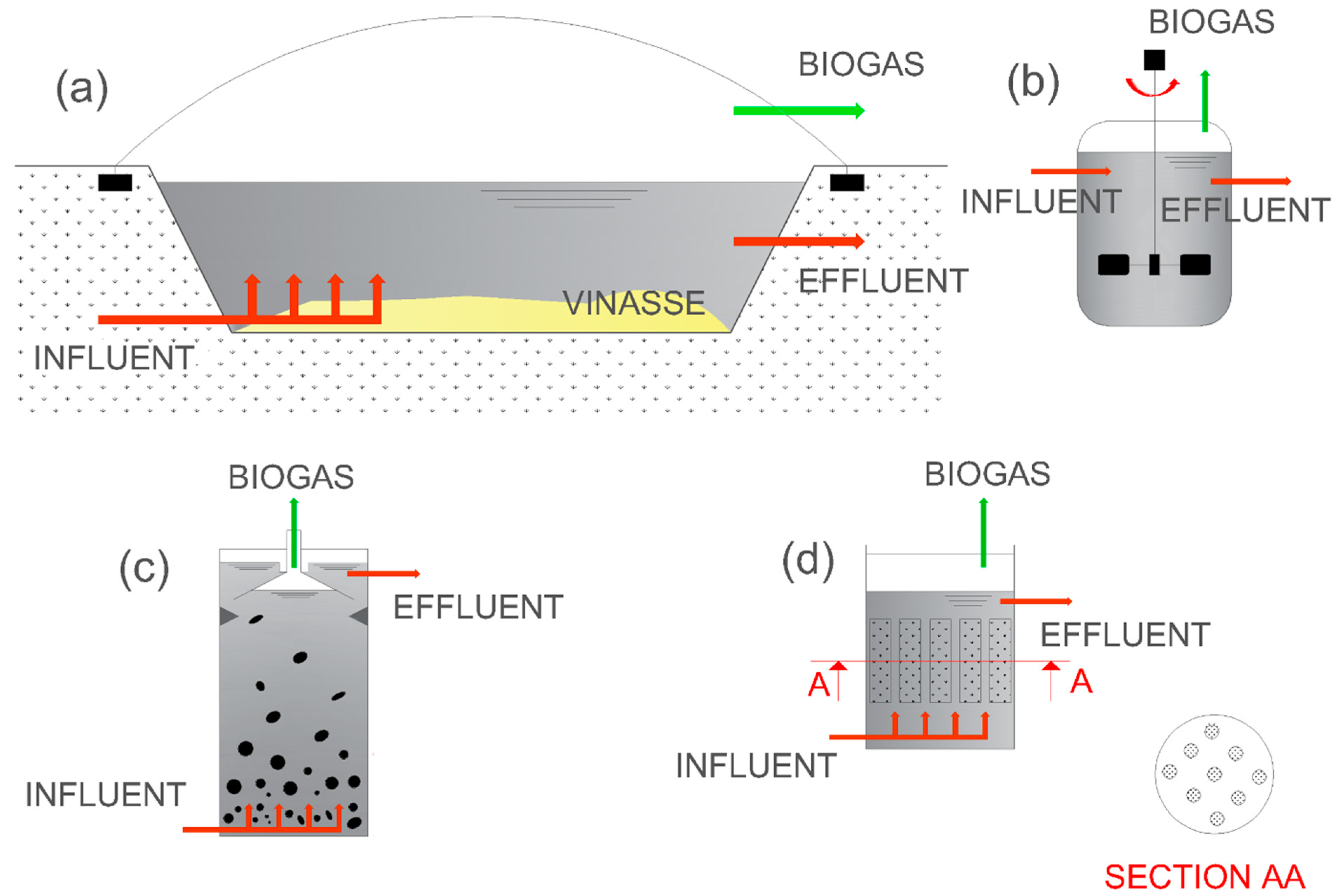

1.1. Technological Pathways for Anaerobic Digestion of Sugarcane Vinasse: Anaerobic Bioreactors

1.1.1. Covered Lagoon Biodigesters (CLBs)

1.1.2. Continuous Stirred-Tank Reactor (CSTR)

1.1.3. Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) Reactor

1.1.4. Anaerobic Structured-Bed Reactor (AnSTBR)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design Criteria, Anaerobic Bioreactor Dimensions, and Biogas Characteristics

2.2. Risk Assessment

2.2.1. Probability and Consequence Analysis

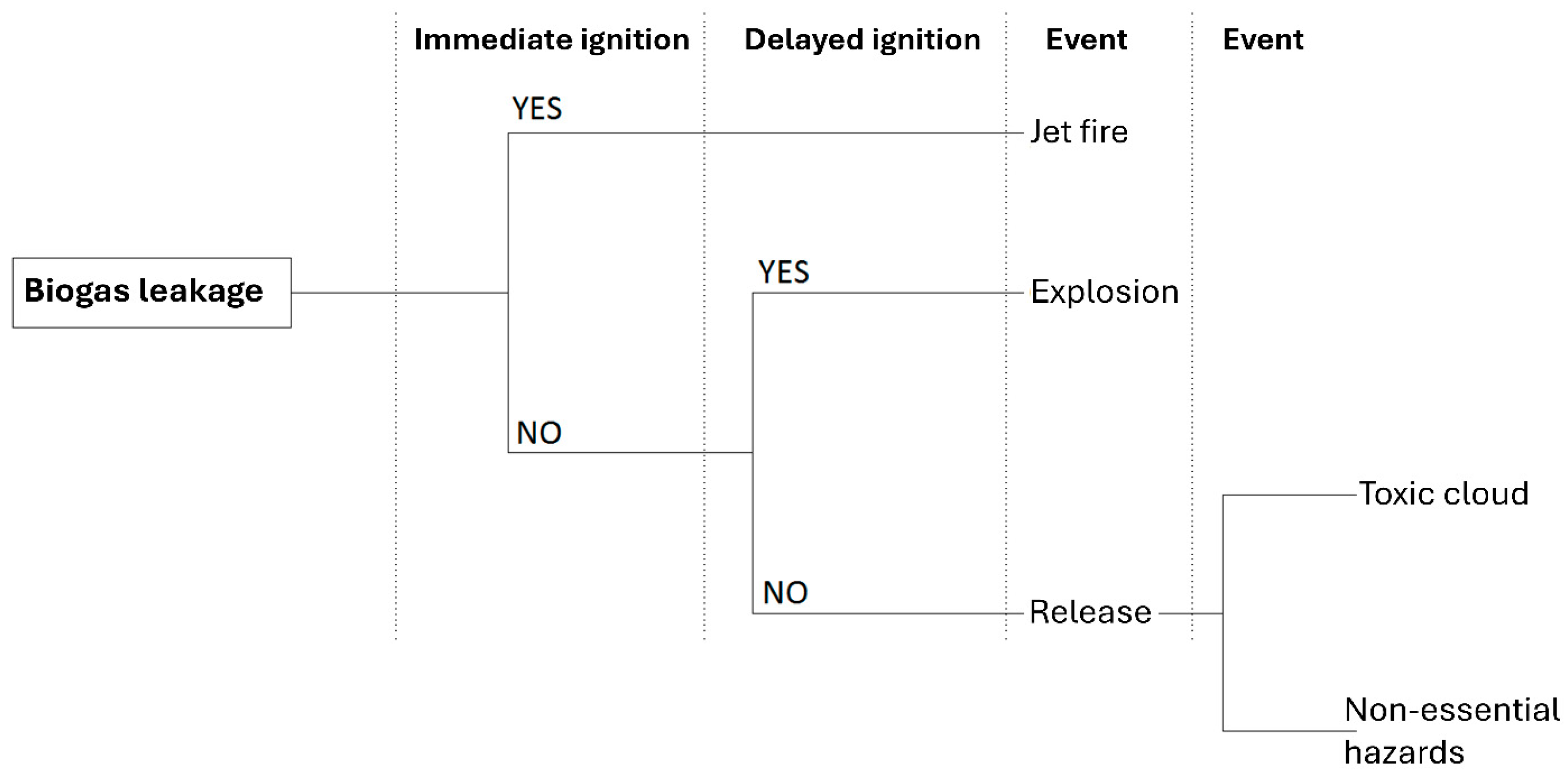

2.2.2. Hazardous Event Scenarios

3. Results

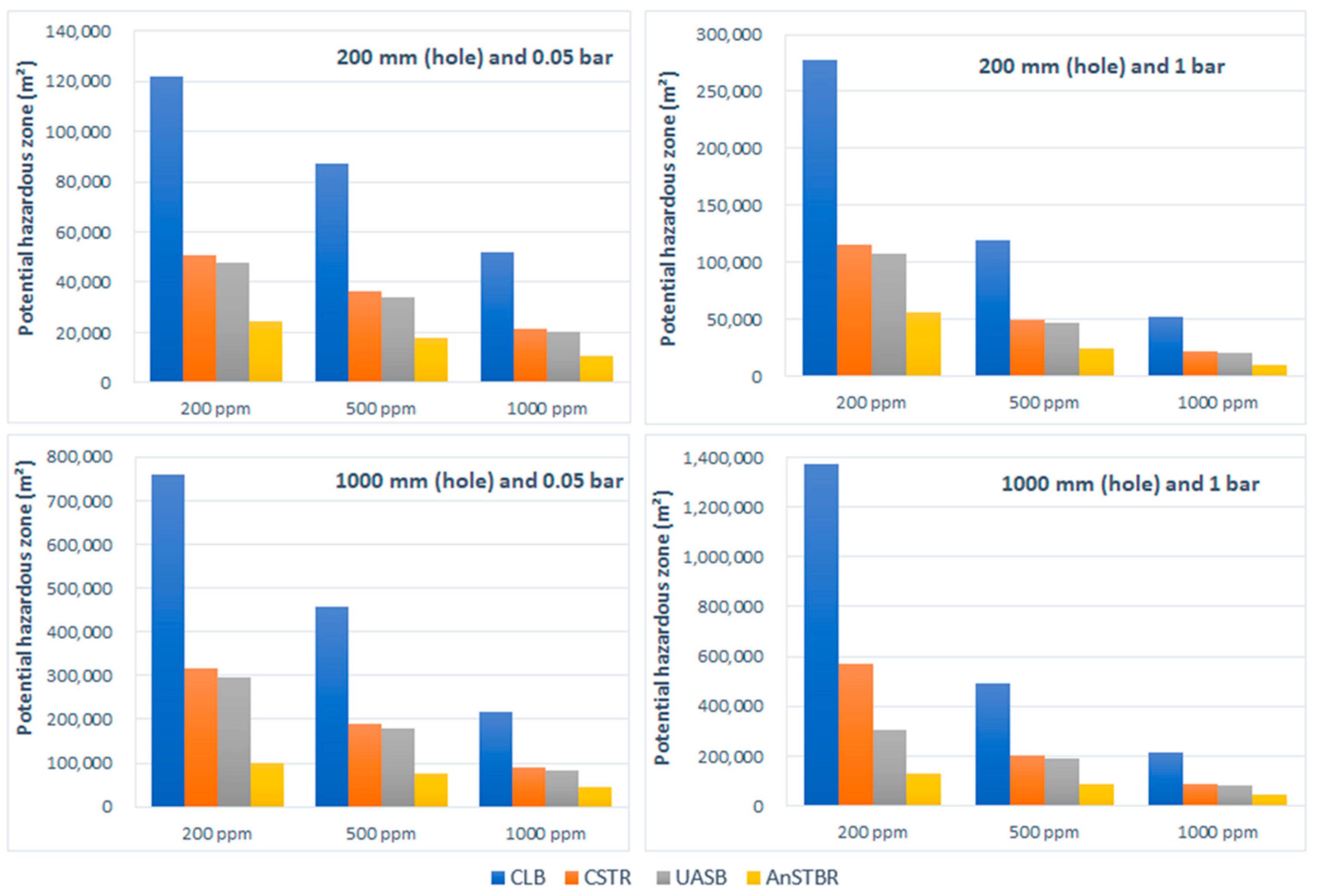

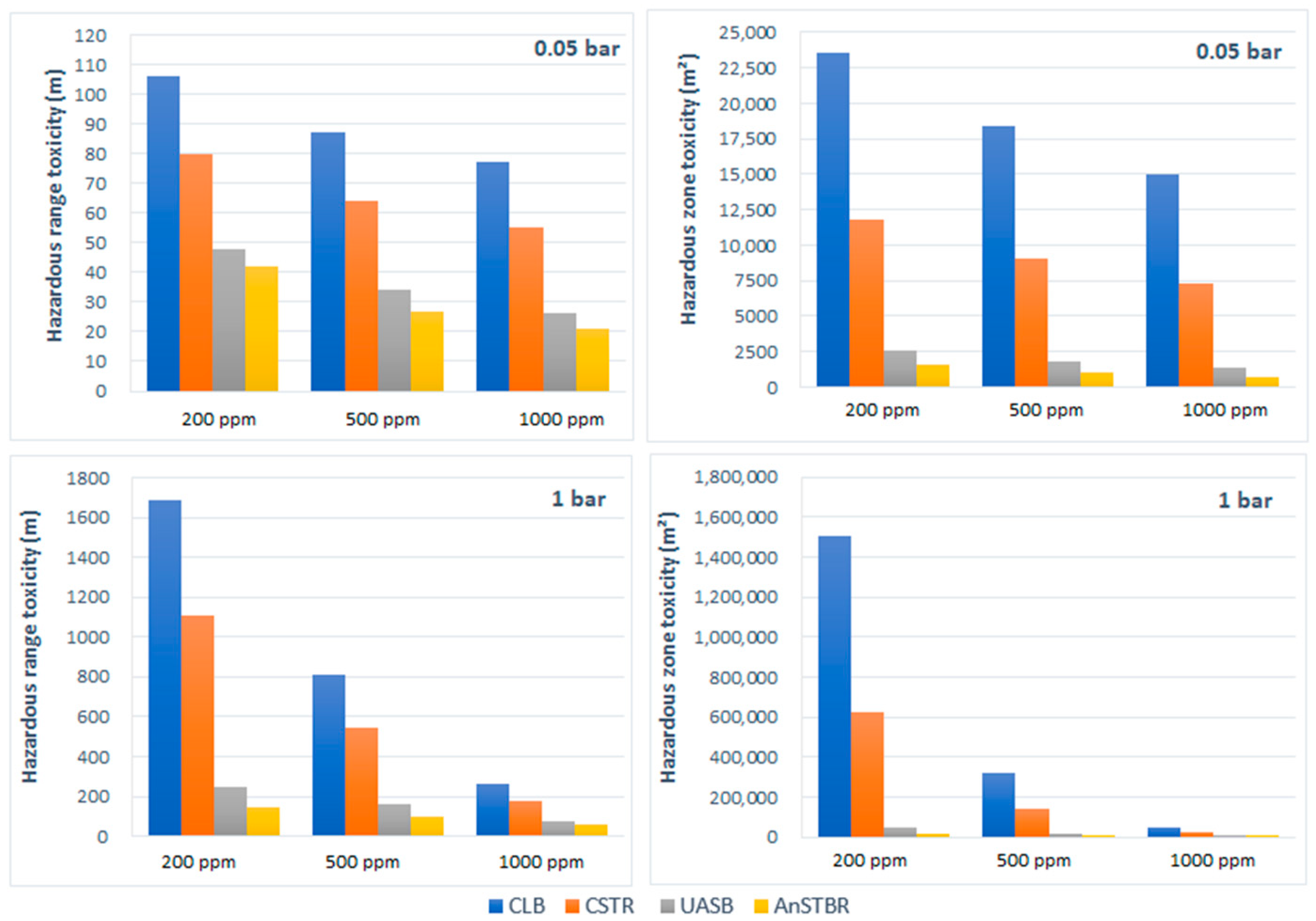

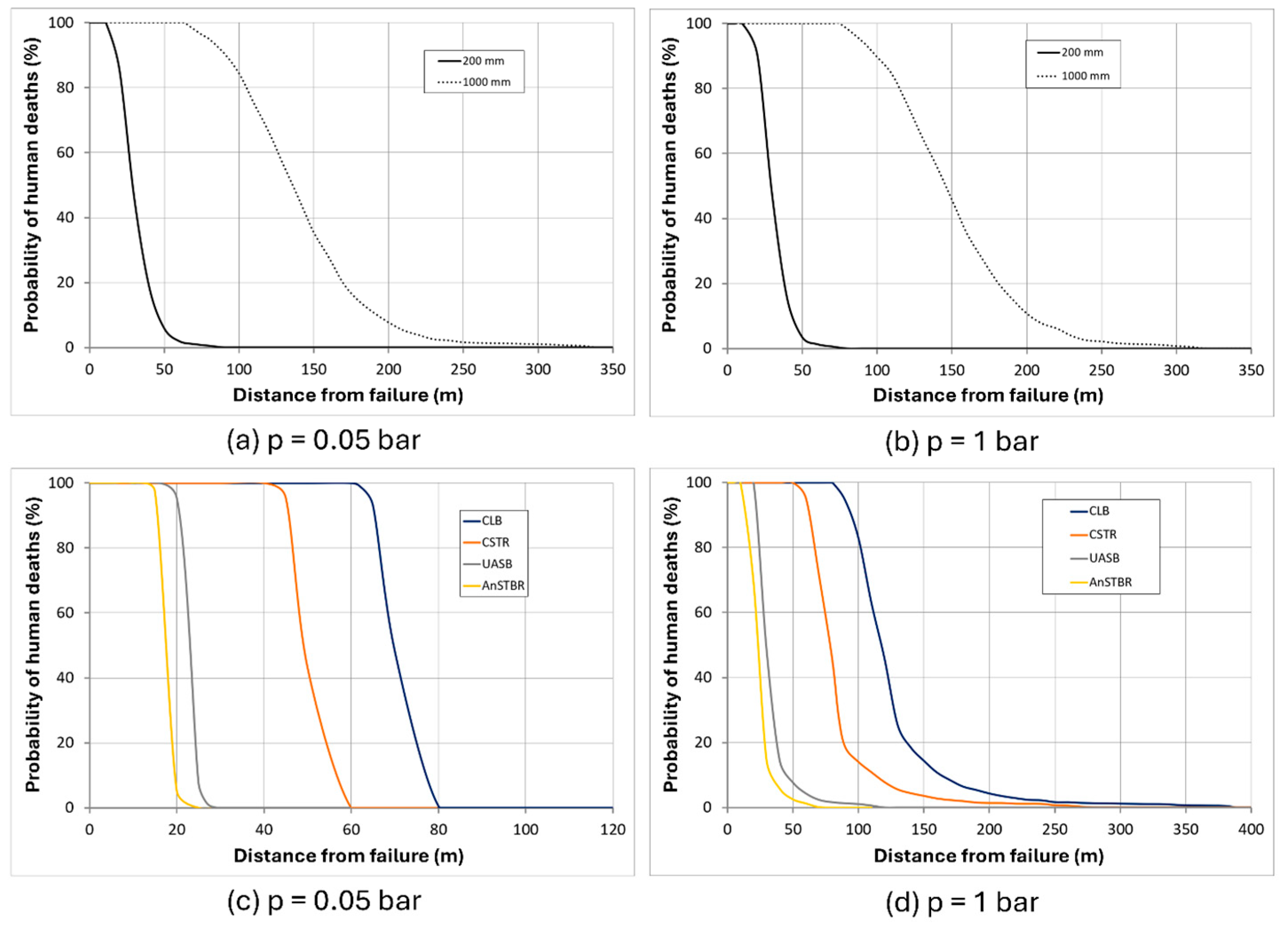

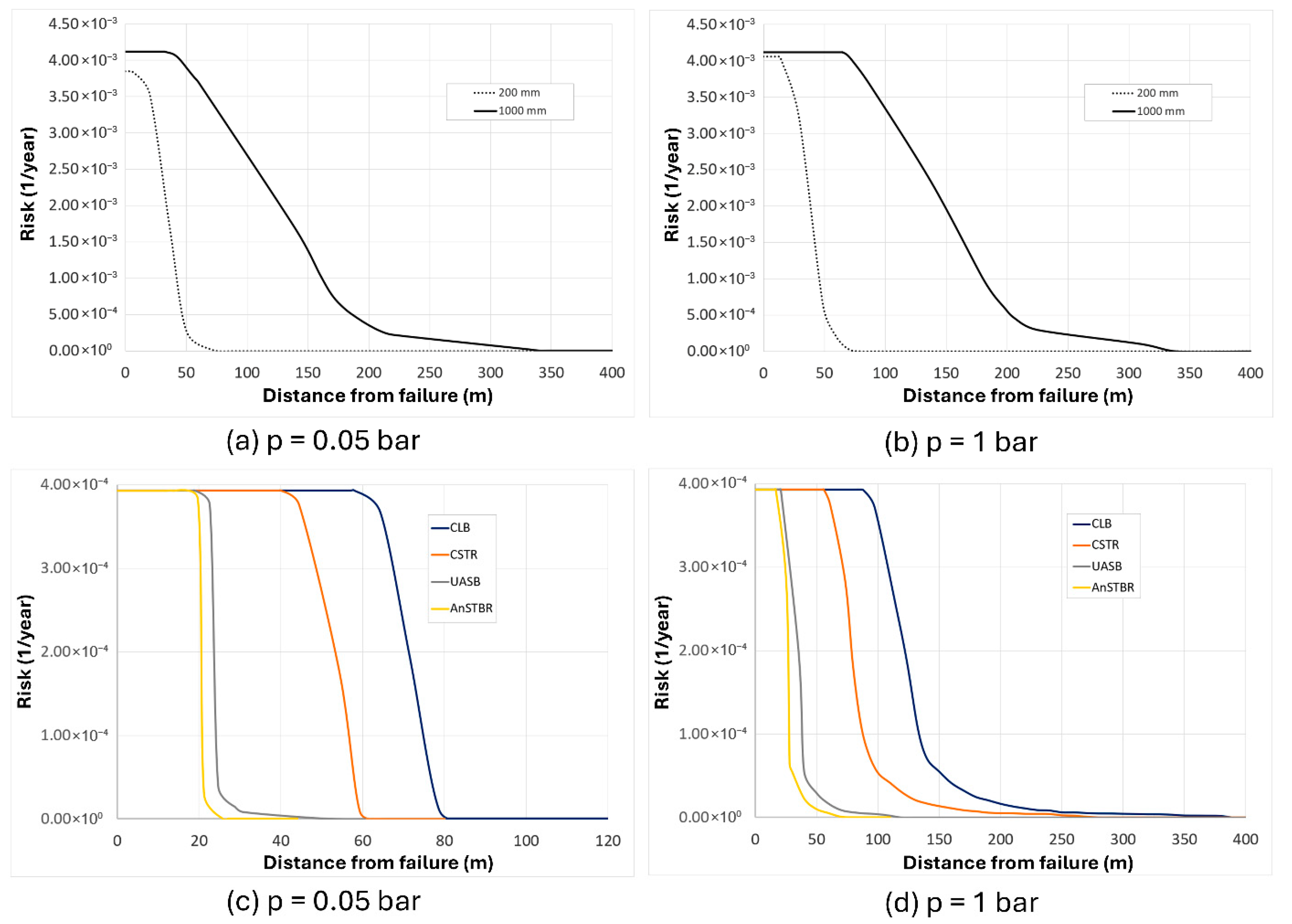

3.1. Analysis of the Hazards Related to Failure of the Biogas Installation

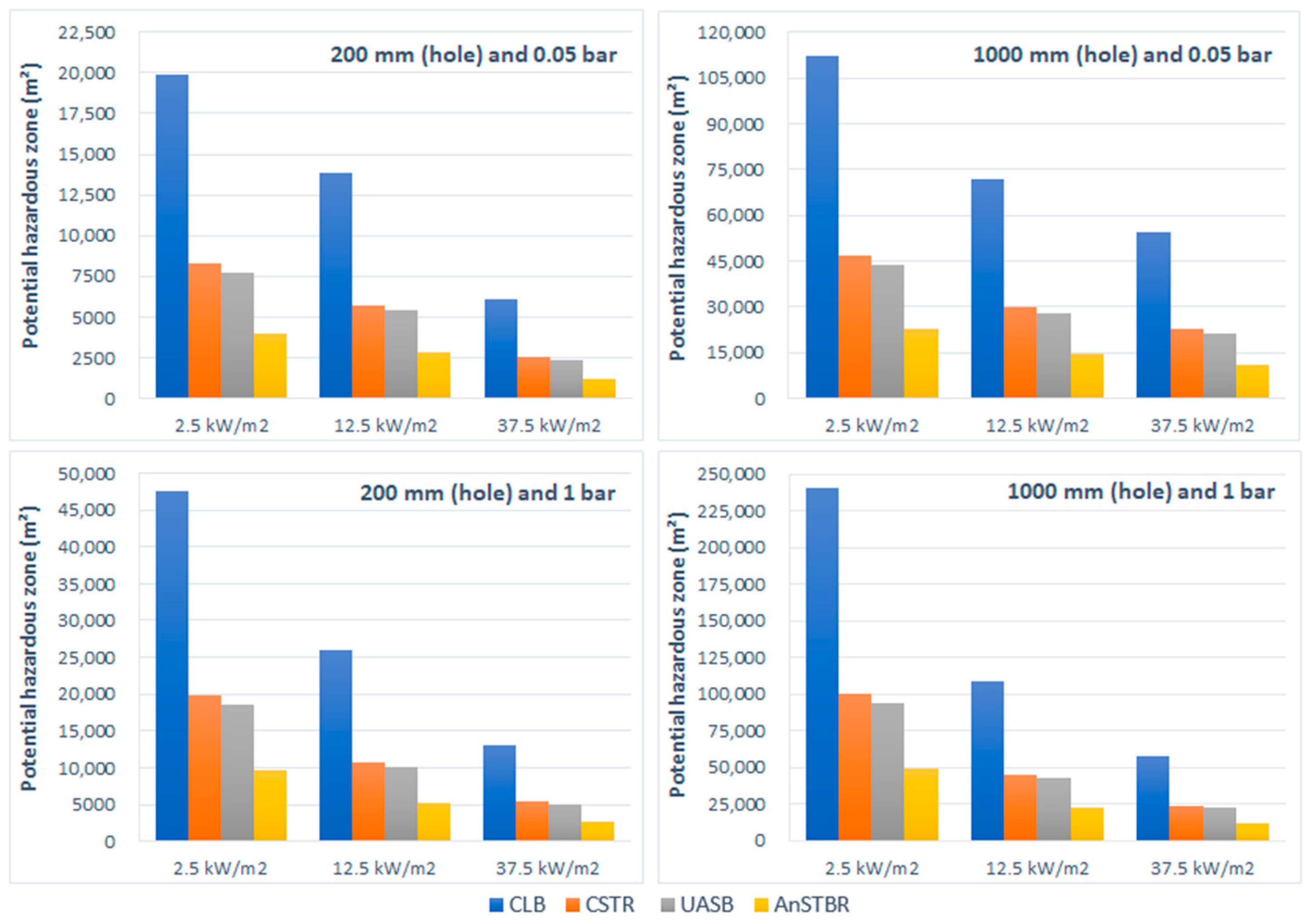

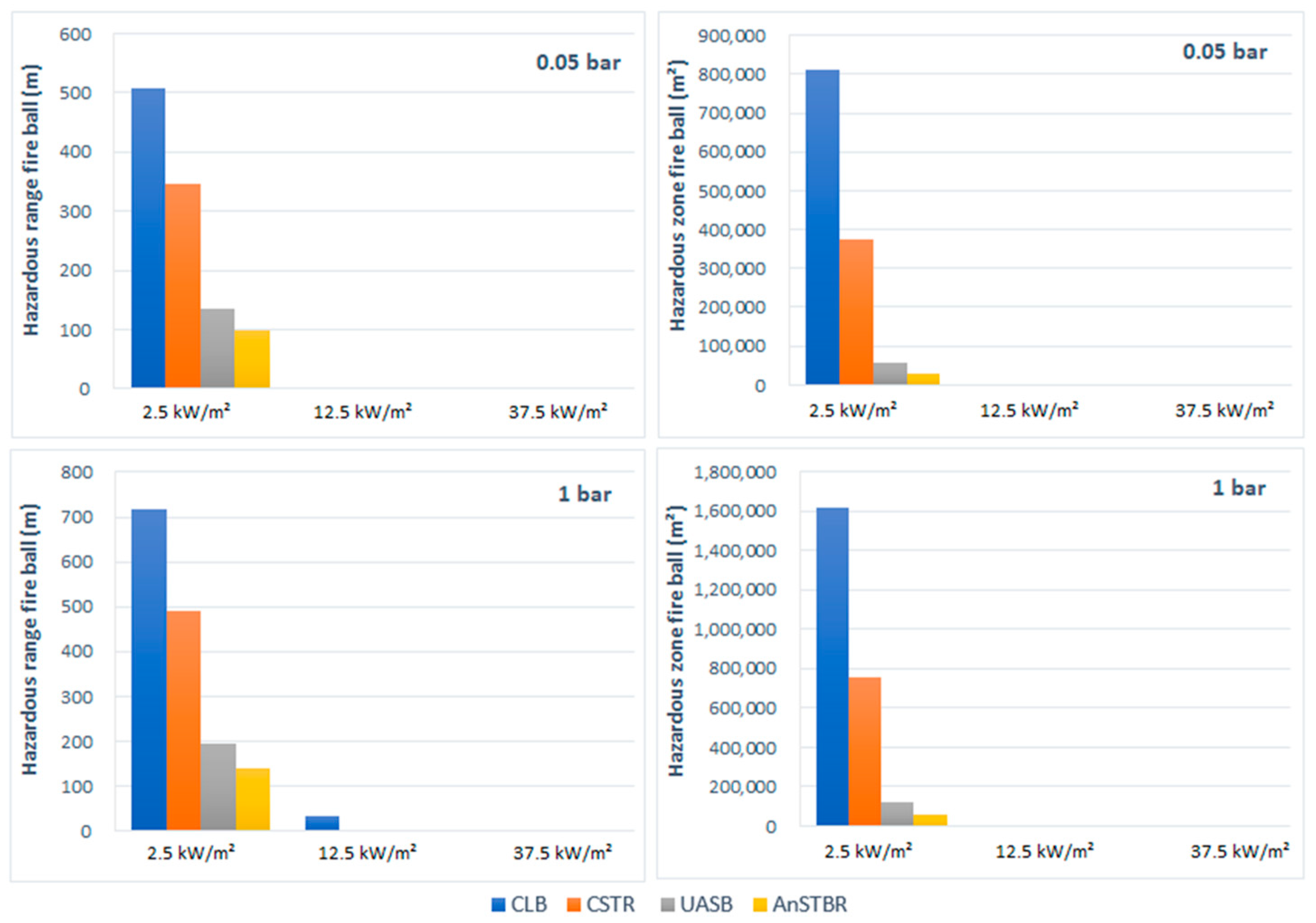

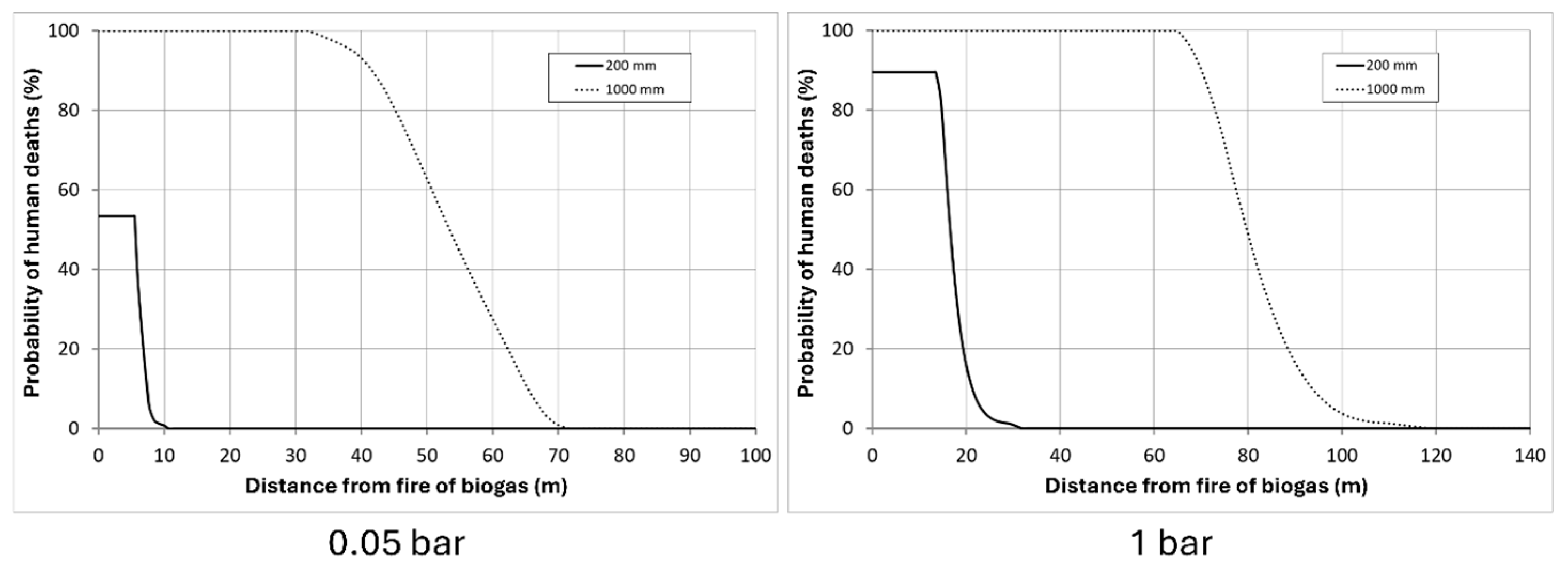

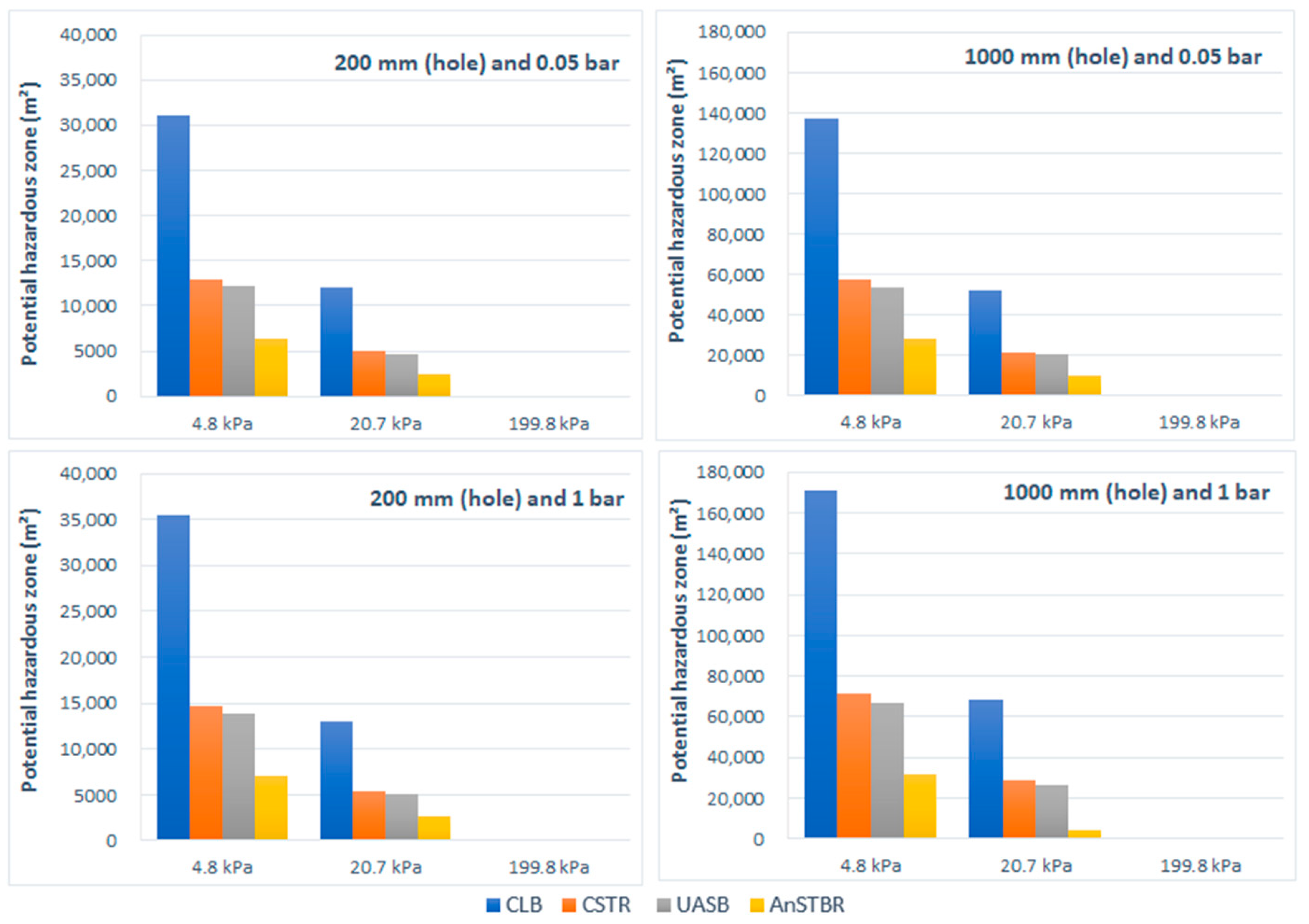

3.1.1. Fire

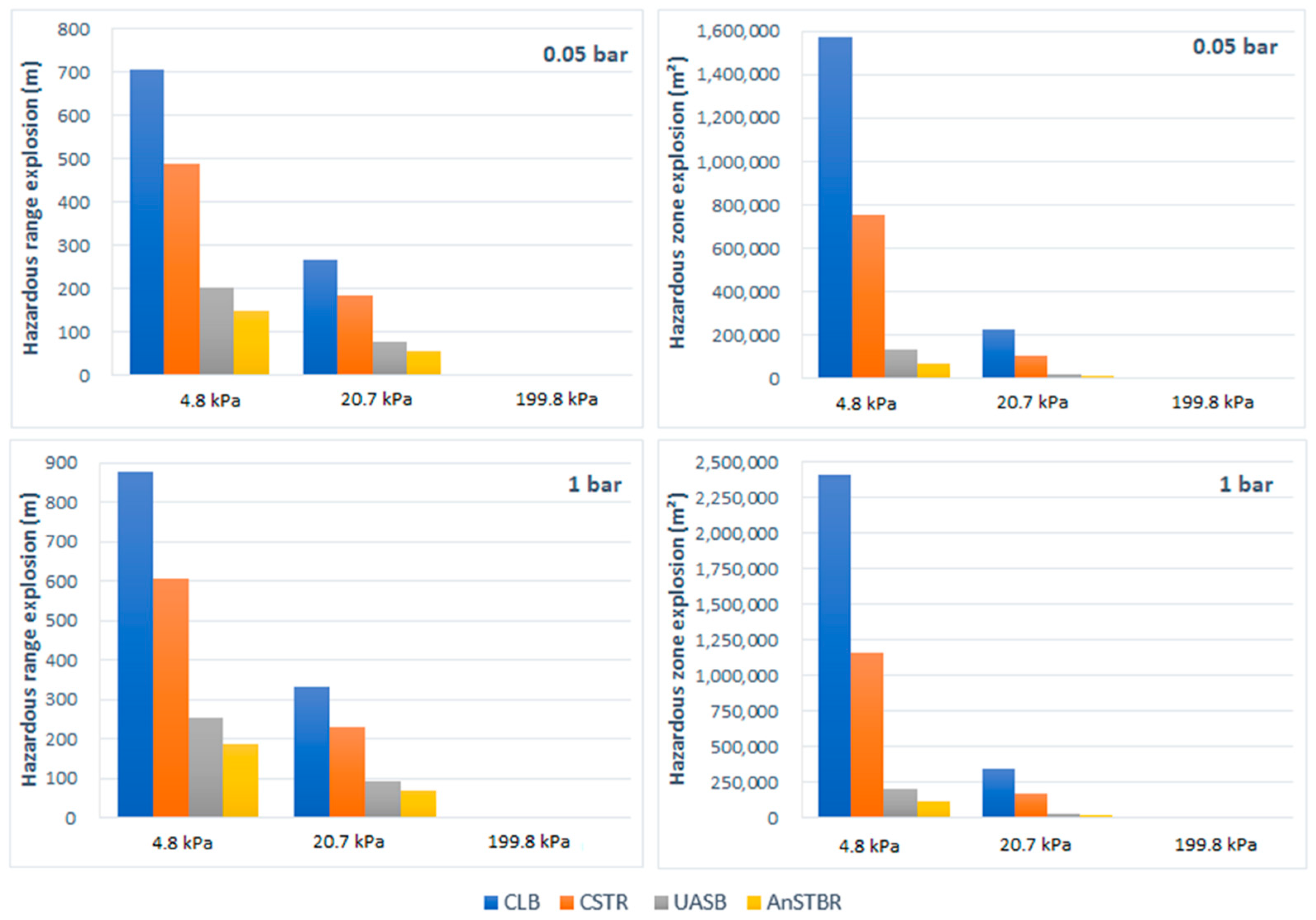

3.1.2. Explosion

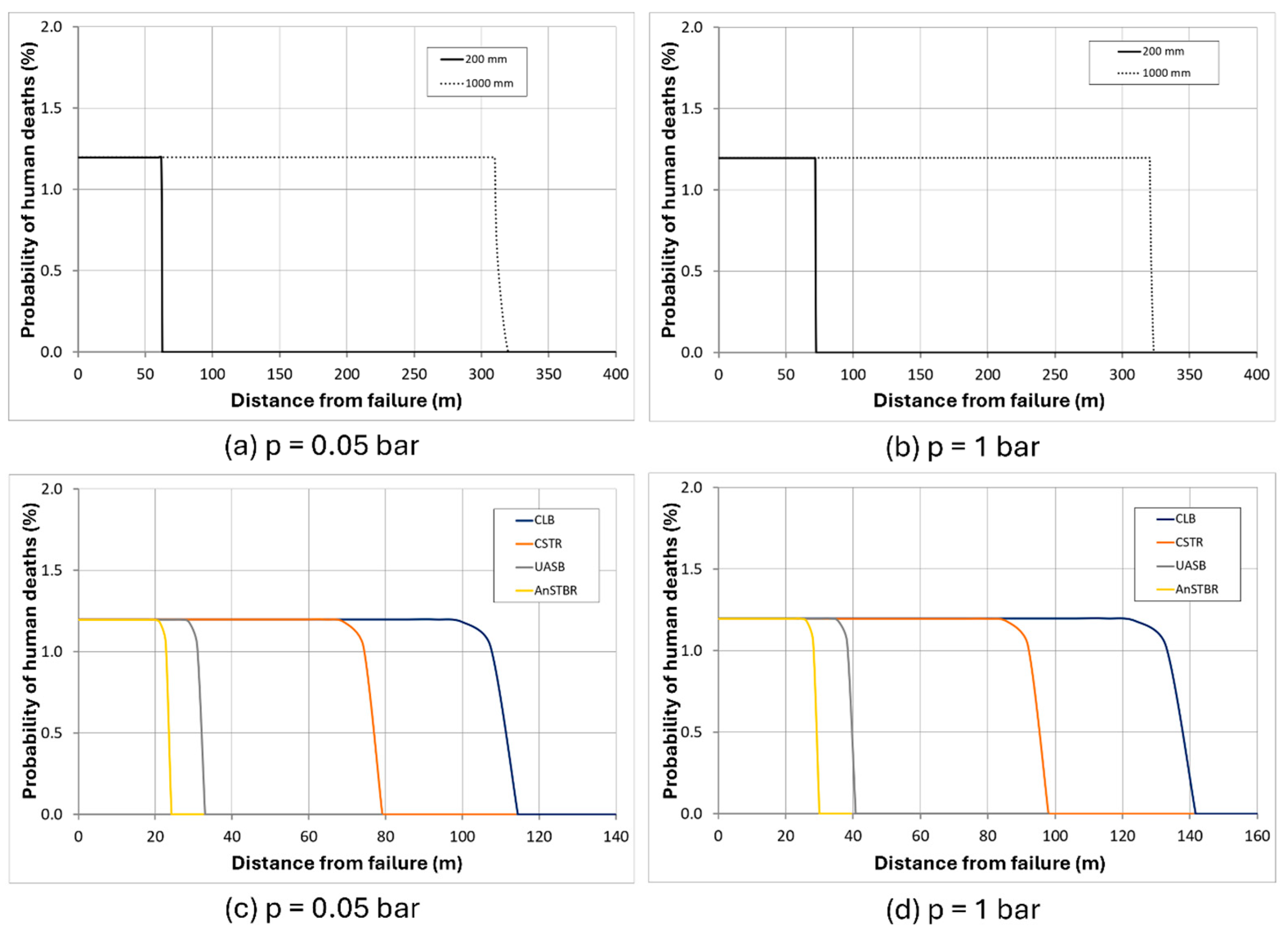

3.1.3. H2S Intoxication

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| AnSTBR | Anaerobic structured-bed reactor |

| bioCH4 | Biomethane |

| CLB | Covered lagoon biodigester |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CSTR | Continuous stirred-tank reactor |

| HR | Hazardous range |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| HZ | Hazardous zone |

| PHZ | Potential hazardous zone |

| OLR | Organic loading rate |

| SRT | Solids retention time |

| UASB | Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket |

References

- Höök, M.; Tang, X. Depletion of fossil fuels and anthropogenic climate change—A review. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.A.; Warner, K.J. The 21st century population-energy-climate nexus. Energy Policy 2016, 93, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Biofuels sources, biofuel policy, biofuel economy and global biofuel projections. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2106–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chozhavendhan, S.; Karthigadevi, G.; Bharathiraja, B.; Praveen Kumar, R.; Abo, L.D.; Venkatesa Prabhu, S.; Balachandar, R.; Jayakumar, M. Current and prognostic overview on the strategic exploitation of anaerobic digestion and digestate: A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 216 Pt 2, 114526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.D.N., Jr.; Etchebehere, C.; Perecin, D.; Teixeira, S.; Woods, J. Advancing anaerobic digestion of sugarcane vinasse: Current development, struggles and future trends on production and end-uses of biogas in Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Neto, J.V.; Gallo, W.L.R. Potential impacts of vinasse biogas replacing fossil oil for power generation, natural gas, and increasing sugarcane energy in Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAB Acompanhamento da Safra Brasileira (Cana-de-Açúcar). Vol. 4o Levantamento. 2023. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/info-agro/safras/cana/boletim-da-safra-de-cana-de-acucar/item/download/47205_4d3411e94856841a815af389cab22b93 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Moraes, B.S.; Zaiat, M.; Bonomi, A. Anaerobic digestion of vinasse from sugarcane ethanol production in Brazil: Challenges and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 44, 888–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.S.; Zaiat, M.; Oller do Nascimento, C.A.; Fuess, L.T. Does sugarcane vinasse composition variability affect the bioenergy yield in anaerobic systems? A dual kinetic-energetic assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogeri, R.C.; Fuess, L.T.; Araujo, M.N.; Eng, F.; Borges, A.V.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z.; da Silva, A.J. Methane production from sugarcane vinasse: The alkalinizing potential of fermentative-sulfidogenic processes in two-stage anaerobic digestion. Energy Nexus 2024, 14, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuess, L.T.; Zaiat, M.; Nascimento, C.A.O. Novel insights on the versatility of biohydrogen production from sugarcane vinasse via thermophilic dark fermentation: Impacts of pH-driven operating strategies on acidogenesis metabolite profiles. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 286, 121379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogeri, R.C.; Fuess, L.T.; Eng, F.; Borges, A.V.; Araujo, M.N.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z.; da Silva, A.J. Strategies to Control pH in the Dark Fermentation of Sugarcane Vinasse: Impacts on Sulfate Reduction, Biohydrogen Production and Metabolite Distribution. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.C.; Weinberger, C.B.; Lawley, A.; Thomas, D.H.; Moore, T.W. Fundamentals of Engineering Energy. J. Eng. Educ. 1994, 83, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, P.N.L.; Visser, A.; Janssen, A.J.H.; Hulshoff Pol, L.W.; Lettinga, G. Biotechnological treatment of sulfate-rich wastewaters. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 28, 41–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Othman, M.H.D.; Hashim, H.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A.F.; Rezaei-Dashtarzhandi, M.; Azelee, I.W. Biogas as a renewable energy fuel—A review of biogas upgrading, utilisation and storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 150, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Yu, X. Selection of appropriate biogas upgrading technology-a review of biogas cleaning, upgrading and utilisation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreides, M.; Pokorná-Krayzelová, L.; Bartáček, J.; Jeníč, P. Biological H2S removal from gases. In Environmental Technologies to Treat Sulphur Pollution: Principles and Engineering, 2nd ed.; Lens, P.N.L., Ed.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2020; pp. 345–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, R.M.; Seabra, J.E.A. Technical-economic assessment of different biogas upgrading routes from vinasse anaerobic digestion in the Brazilian bioethanol industry. Energy 2017, 119, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, V.C.; Cozzani, V. Major accident hazard in bioenergy production. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 35, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, V.C.; Papasidero, S.; Scarponi, G.E.; Guglielmi, D.; Cozzani, V. Analysis of accidents in biogas production and upgrading. Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trávníček, P.; Kotek, L.; Junga, P.; Vítěz, T.; Drápela, K.; Chovanec, J. Quantitative analyses of biogas plant accidents in Europe. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolecka, K.; Rusin, A. Potential hazards posed by biogas plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admasu, A.; Bogale, W.; Mekonnen, Y.S. Experimental and simulation analysis of biogas production from beverage wastewater sludge for electricity generation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Chan, A.; Ali, S.; Saha, A.; Haushalter, K.J.; Lam, W.L.M.R.; Glasheen, M.; Parker, J.; Brenner, M.; Mahon, S.B.; et al. Hydrogen Sulfide-Mechanisms of Toxicity and Development of an Antidote. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvitved-Jacobsen, T. Sulfur transformations in sewer networks: Effects, prediction and mitigation of impacts. In Environmental Technologies to Treat Sulfur Pollution: Principles and Engineering, 2nd ed.; Lens, P.N.L., Ed.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, V.C.; Guglielmi, D.; Cozzani, V. Identification of critical safety barriers in biogas facilities. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 169, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.C.; de Souza Vandenberghe, L.P.; Sydney, E.B.; Karp, S.G.; Magalhães, A.I.; Martinez-Burgos, W.J.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Vieira, S.; Letti, L.A.J. Biomethane Production from Sugarcane Vinasse in a Circular Economy: Developments and Innovations. Fermentation 2023, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Moraes, B.; Palacios-Bereche, R.; Martins, G.; Nebra, S.A.; Fuess, L.T.; Silva, A.J.; da Silva Clementino, W.; Bajay, S.V.; Manduca, P.C.; Lamparelli, R.A.; et al. Biogas production: Technologies and applications. In Biofuels and Biorefining Volume 1: Current Technologies for Biomass Conversion; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 215–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, S.; Fuess, L.T.; Pires, E.C. Media arrangement impacts cell growth in anaerobic fixed-bed reactors treating sugarcane vinasse: Structured vs. randomic biomass immobilization. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 235, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuess, L.T.; Kiyuna, L.S.M.; Ferraz Júnior, A.D.N.; Persinoti, G.F.; Squina, F.M.; Garcia, M.L.; Zaiat, M. Thermophilic two-phase anaerobic digestion using an innovative fixed-bed reactor for enhanced organic matter removal and bioenergy recovery from sugarcane vinasse. Appl. Energy 2017, 189, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges Ado, V.; Fuess, L.T.; Takeda, P.Y.; Alves, I.; Dias, M.E.S.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z. Co-digestion of biofuel by-products: Enhanced biofilm formation maintains high organic matter removal when methanogenesis fails. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, P.Y.; Oliveira, C.A.; Dias, M.E.S.; Paula, C.T.; Borges Ado, V.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z. Enhancing the energetic potential of sugarcane biorefinery exchanging vinasse and glycerol in sugarcane off-season in an anaerobic reactor. Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierangeli, G.M.F.; Gregoracci, G.B.; Del Nery, V.; Pozzi, E.; de Araujo Junior, M.M.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z.; Saia, F.T. Long-term temporal dynamics of total and potentially active microbiota affect the biogas quality from the anaerobic digestion of vinasse in a pilot-scale hybrid anaerobic reactor. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 26, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tápparo, D.C.; Cândido, D.; Steinmetz, R.L.R.; Etzkorn, C.; do Amaral, A.C.; Antes, F.G.; Kunz, A. Swine manure biogas production improvement using pre-treatment strategies: Lab-scale studies and full-scale application. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 15, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Bhattacherjee, S. A review study on anaerobic digesters with an Insight to biogas production. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Invent. 2013, 2, 2319–6734. Available online: http://ijesi.org/papers/Vol(2)3%20(Version-4)/B230817.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- van Haandel, A.; van der Lubbe, J. Anaerobic Sewage Treatment: Optimization of Process and Physical Design of Anaerobic and Complementary Processes; van Haandel, A., van der Lubbe, J., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2019; 400p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biogas Fachverband. Biowaste to Biogas—The Production of Energy and Fertilizer from Organic Waste. 2019. Available online: https://www.biogas.org/fileadmin/redaktion/dokumente/medien/broschueren/biowaste/biowaste-to-biogas.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- PROBIOGÁS Tecnologias De Digestão Anaeróbia Com Relevância Para O Brasil: Substratos, Digestores e Uso de Biogás. Ministério ds Cidades. 2015. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/probiogas-tecnologias-biogas.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Kress, P.; Nägele, H.J.; Oechsner, H.; Ruile, S. Effect of agitation time on nutrient distribution in full-scale CSTR biogas digesters. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittmann, B.E.; McCarty, P.L. Environmental Biotechnology: Principles and Applications; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2001; 768p. [Google Scholar]

- van Lier, J.B.; van der Zee, F.P.; Frijters, C.T.M.J.; Ersahin, M.E. Celebrating 40 years anaerobic sludge bed reactors for industrial wastewater treatment. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf; Eddy, I. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery; Tchobanoglous, G., Stensel, H.D., Tsuchihashi, R., Burton, F., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2013; pp. 1–2048. [Google Scholar]

- de Lemos Chernicharo, C.A.; Bressani-Ribeiro, T. (Eds.) Anaerobic Reactors for Sewage Treatment: Design, Construction and Operation; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2019; 420p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kamah, H.; Tawfik, A.; Mahmoud, M.; Abdel-Halim, H. Treatment of high strength wastewater from fruit juice industry using integrated anaerobic/aerobic system. Desalination 2010, 253, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, R.A.; Iorhemen, O.T.; Tay, J.H. Advances in biological systems for the treatment of high-strength wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2016, 10, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobi, K.; Mashitah, M.D.; Vadivelu, V.M. Development and utilization of aerobic granules for the palm oil mill (POM) wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 174, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, M.N.; Fuess, L.T.; Cavalcante, W.A.; Couto, P.T.; Rogeri, R.C.; Adorno, M.A.T.; Sakamoto, I.K.; Zaiat, M. Fixed bed in dark fermentative reactors: Is it imperative for enhanced biomass retention, biohydrogen evolution and substrate conversion? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwari, K.V.; Balakrishnan, M.; Kansal, A.; Lata, K.; Kishore, V.V.N. State-of-the-art of anaerobic digestion technology for industrial wastewater treatment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2000, 4, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuess, L.T.; de Araújo Júnior, M.M.; Garcia, M.L.; Zaiat, M. Designing full-scale biodigestion plants for the treatment of vinasse in sugarcane biorefineries: How phase separation and alkalinization impact biogas and electricity production costs? Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017, 119, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, B.; Harris, P.; Baillie, C.; Pittaway, P.; Yusaf, T. Assessing a new approach to covered anaerobic pond design in the treatment of abattoir wastewater. Aust. J. Multi-Discip. Eng. 2013, 10, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, A.; Naegele, H.J.; Sondermann, J. How efficient are agitators in biogas digesters? Determination of the efficiency of submersible motor mixers and incline agitators by measuring nutrient distribution in full-scale agricultural biogas digesters. Energies 2013, 6, 6255–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häring, I. Risk analysis and management: Engineering resilience. In Risk Analysis and Management: Engineering Resilience; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 1–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trávníček, P.; Kotek, L.; Koutný, T.; Vítĕz, T. Quantitative risk assessment of biogas plant—Determination of assumptions and estimation of selected top event. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2019, 63, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolecka, K.; Rusin, A. Analysis of hazards related to syngas production and transport. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2535–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vílchez, J.A.; Espejo, V.; Casal, J. Generic event trees and probabilities for the release of different types of hazardous materials. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2011, 24, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, J.; Tchouvelev, A.; Engebo, A. Development of uniform harm criteria for use in quantitative risk analysis of the hydrogen infrastructure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusin, A.; Stolecka-Antczak, K. Assessment of the Safety of Transport of the Natural Gas–Ammonia Mixture. Energies 2023, 16, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwayyir, H.H.S.; Maria, G.; Dinculescu, D. Simulation of the consequences of the ammonium nitrate explosion following the truck accident next to mihăileşti village (Romania) in 2004. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2021, 34, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, T.L. Hydrogen sulfide: Advances in understanding human toxicity. Int. J. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Unit | Bioreactor Configuration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLB | CSTR | UASB | AnSTBR | ||

| Organic loading rate (OLR) | kg-COD m−3 d−1 | 2 a | 5 a | 10 a | 25 b |

| Working volume (VW) | m3 | 153,891 | 61,556 | 30,778 | 12,311 |

| Headspace | m3 | 141,579 c | 46,783 c | 3386 b | 1354 b |

| Working height (HW) | m | 5 d | 6 e | 6 f | 6.5 b |

| Area | m2 | 30,778 | 10,259 | 5130 | 1894 |

| Dimension characteristics | W × L or D (m) g | 90 × 342 d | 114.3 h | 40 × 128.4 i | 40 × 47.4 j |

| Total perimeter | m | 864 | 509 | 336.8 | 174.8 |

| Headspace Pressure | 0.05 bar | 1 bar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Flux | 200 mm | 1000 mm | 200 mm | 1000 mm |

| 2.5 kW m−2 | 23 | 130 | 55 | 279 |

| 12.5 kW m−2 | 16 | 83 | 30 | 126 |

| 37.5 kW m−2 | 7 | 63 | 15 | 66 |

| Headspace Pressure | 0.05 bar | 1 bar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure Wave | 200 mm | 1000 mm | 200 mm | 1000 mm |

| 4.8 kPa | 36 | 159 | 41 | 198 |

| 20.7 kPa | 14 | 60 | 15 | 79 |

| 199.8 kPa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headspace Pressure | 0.05 bar | 1 bar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2S Concentration | 200 mm | 1000 mm | 200 mm | 1000 mm |

| 200 ppm | 141 | 878–570 a | 321 | 1587–735 c |

| 500 ppm | 101 | 530–430 b | 139 | 570–490 d |

| 1000 ppm | 60 | 250 | 60 | 252 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogeri, R.C.; Stolecka-Antczak, K.; Maradini, P.d.S.; Camiloti, P.R.; Rusin, A.; Fuess, L.T. Risk Assessment of Biogas Production from Sugarcane Vinasse: Does the Anaerobic Bioreactor Configuration Affect the Hazards? Biomass 2025, 5, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040079

Rogeri RC, Stolecka-Antczak K, Maradini PdS, Camiloti PR, Rusin A, Fuess LT. Risk Assessment of Biogas Production from Sugarcane Vinasse: Does the Anaerobic Bioreactor Configuration Affect the Hazards? Biomass. 2025; 5(4):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040079

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogeri, Renan Coghi, Katarzyna Stolecka-Antczak, Priscila da Silva Maradini, Priscila Rosseto Camiloti, Andrzej Rusin, and Lucas Tadeu Fuess. 2025. "Risk Assessment of Biogas Production from Sugarcane Vinasse: Does the Anaerobic Bioreactor Configuration Affect the Hazards?" Biomass 5, no. 4: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040079

APA StyleRogeri, R. C., Stolecka-Antczak, K., Maradini, P. d. S., Camiloti, P. R., Rusin, A., & Fuess, L. T. (2025). Risk Assessment of Biogas Production from Sugarcane Vinasse: Does the Anaerobic Bioreactor Configuration Affect the Hazards? Biomass, 5(4), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040079