Abstract

This study provides a comparative thermochemical analysis of coconut husk, rice husk and mineral coal, assessing their potential for use in sustainable energy applications. Standardised proximate and ultimate analyses, thermogravimetric (TGA/DTG) evaluations and combustibility index measurements were performed under identical laboratory conditions to ensure consistent comparisons could be made. Coconut husk exhibited the lowest ignition temperature (320.88 °C) and the highest combustibility index (2.385). This indicates its suitability for rapid combustion and biochar production. Its low ash and sulphur content enhances its environmental performance. Rice husk demonstrated moderate thermal behaviour and a high ash yield owing to its elevated silica content, suggesting greater potential for non-energy applications, such as silica recovery and advanced materials production. Mineral coal displayed the highest carbon content and calorific value (24.38 MJ/kg), reflecting high energy density, but also a considerable sulphur content that raises environmental concerns. Unlike many studies that address these materials separately, this work provides a direct, side-by-side comparison under controlled conditions. This offers practical insights for selecting materials in energy systems. The results reinforce the potential of agro-industrial residues in cleaner energy strategies, while emphasising the need for emission control measures when using fossil fuels.

1. Introduction

Energy is fundamental to modern societies, enabling the development of systems that meet essential human needs, such as access to food and shelter, employment opportunities, and transport [,]. However, the global overreliance on fossil fuels, particularly oil and coal, poses serious threats to energy security and environmental sustainability due to their non-renewable nature and high levels of pollution []. In Colombia, for example, energy consumption has increased from 728 PJ to 1346 PJ in recent decades due to population growth and industrial expansion. Between 1975 and 2019, the population more than doubled and GDP increased fourfold, with the manufacturing and transport sectors showing the most significant increases in energy demand [].

These trends highlight the urgent need to identify cleaner, more sustainable energy sources []. Of the various renewable energy alternatives, plant-based biomass, such as agricultural residues and energy crops, has emerged as a viable and sustainable source. It is attracting increasing attention due to its potential to replace or complement fossil fuels [,]. Biomass conversion processes, whether biological or thermochemical, offer a way to produce heat, electricity and chemical compounds. However, one of the main limitations of biomass is its relatively low calorific value compared to fossil fuels, which could affect its performance in high-demand energy systems [,,].

Despite this drawback, the development of biomass-based energy projects is growing due to their potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the pollution associated with the combustion of fossil fuels [,].

Coconut husk and rice husk, for example, are abundant agro-industrial by-products that have attracted interest as alternative fuels. However, challenges such as irregular availability, bulk volume and costly logistics hinder their practical application, particularly in areas where production is decentralised or seasonal [,,]. Coconut husk and rice husk were selected as representative biomasses due to their abundant production in local agricultural and industrial activities, ensuring regional relevance. Other potential sources of biomass, such as forest residues, were not considered due to their limited availability in the study area.

By contrast, mineral coal is still widely used in Colombia and many other regions thanks to its high energy density and well-established infrastructure []. However, it is also a major source of sulphur oxides and carbon emissions, making cleaner alternatives or hybrid solutions necessary []. Therefore, understanding how biomass residues compare thermochemically to fossil fuels under the same experimental conditions is essential for designing realistic transition strategies.

While many studies have characterised the thermogravimetric behaviour of coconut husk, rice husk or coal independently, few have conducted direct comparative analyses using unified methods. Most available research evaluates these materials in isolation, often using different equipment, atmospheres or heating rates, which makes meaningful comparisons and practical implementation difficult. This study therefore aims to address this issue by systematically comparing coconut husk, rice husk and mineral coal under identical experimental conditions using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), proximate and ultimate analysis, and combustibility index estimation.

These three materials were chosen to represent two contrasting fuel classes: renewable agricultural waste and non-renewable fossil fuel. They were selected for their regional availability and practical relevance. This study examines their thermal decomposition profiles, ignition and burnout temperatures, combustibility and residual composition to determine their suitability for different energy applications and to highlight potential trade-offs in efficiency, emissions and sustainability.

Similarly, in Colombia’s Córdoba region, where this study was conducted, the coconut and rice processing industries produce large quantities of agricultural waste annually. According to regional agricultural reports, coconut production is expected to exceed 38,600 tonnes per year by 2023, while rice availability is estimated at over 100,000 tonnes per year due to significant rice cultivation in the region []. This waste is located close to sources of mineral coal, simplifying logistics and storage infrastructure. The widespread availability of this waste, combined with the potential to reuse existing coal handling systems, makes industrial-scale applications of coconut and rice husks as renewable energy sources highly viable.

Although the results suggest that coconut husk and rice husk have thermal properties that could make them suitable partial substitutes for the mineral coal examined, it should be noted that the actual combustion performance of biomass–coal mixtures was not evaluated experimentally in this study. However, the thermogravimetric characterisation provides a scientific basis for predicting the combustion behaviour of such blends. Future research will focus on experimentally evaluating different blending ratios of the studied biomasses with this specific type of mineral coal. The aim is to optimise energy efficiency, combustion stability and emission control in co-firing applications.

The central hypothesis is that differences in chemical composition and thermal behaviour have a significant impact on the combustion performance and energy potential of these residues. These variations could inform the selection of materials in the design of cleaner energy systems, particularly in contexts aiming to reduce dependency on fossil fuels. Ultimately, the findings will support the development of sustainable waste valorisation strategies, enhance industrial efficiency and contribute to broader environmental protection and energy transition goals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

This study considered three fuel samples: coconut husk, rice husk, and mineral coal, all sourced from the same geographical region to minimize variability due to origin. The biomasses were collected from agricultural processing facilities and the coal from a local supplier. Samples were air-dried, milled, and sieved to a particle size below 450 μm for subsequent analyses.

Figure 1 shows the appearance of the raw materials—coconut husk, rice husk and mineral coal—prior to drying and grinding. These images illustrate the morphological differences between the fuels and will support the discussion of their physical and thermal characteristics in later sections.

Figure 1.

Visual appearance of the raw materials used in the study: (a) Coconut husk. (b) Rice husk. (c) Mineral coal.

2.2. Physical and Chemical Characterisation of Raw Materials

These values were expressed on a real, dry, ash-free and moisture-free (DAF) basis. The characterization of coconut husk, rice husk, and mineral coal was carried out through proximate and ultimate analyses, as well as the determination of bulk density. All analyses were performed following standard methodologies to ensure reproducibility and comparability.

Proximate analysis was conducted according to ASTM D3172, which allowed for the determination of moisture content, volatile matter, ash content, and fixed carbon.

Ultimate analysis was performed based on ASTM D5373-08, involving complete combustion in a CHNS analyzer to determine the percentages of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), sulphur (S), and oxygen (O) (calculated by difference).

In the case of the calorific value of Coconut Husk, according to the work of Forero-Nuñez, 2012, the lower heating value (LHV) of Coconut Husk was found to be 18 MJ/kg []. On the other hand, according to Awulu et al., 2018, the LHV of rice husks is 12.3 MJ/kg []. Finally, according to Patricia et al., 2020, the calorific value of bituminous coal from the department of Córdoba is 24.38 MJ/kg [].

Bulk density was determined following the gravimetric method described by ASTM E873, using a cylindrical container of known volume. Each sample was weighed after being poured into the container without compaction, and the mass-to-volume ratio was calculated [].

However, the specific heat capacity (cp) characterises the ability of a material to store thermal energy. In this case, Lopes & Tannous, 2022, evaluated Coconut Husk fibre using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) []. Prior to testing, the sample was dried at 50 °C until mass stabilisation was achieved and then cooled in a desiccator. After the experiment, the heat capacity of Coconut Husk was found to be 1500 J/kg·K. On the other hand, according to Marques et al., 2020, the specific heat capacity of rice husk at a temperature of 40 °C is 1599 J/kg∙K []. Finally, according to The Engineering ToolBox, 2003, the heat capacity of bituminous coal is 1380 J/kg∙K [].

In the case of the thermal conductivity of coconut husk, different thermal insulation materials, factors affecting thermal insulation and methods for determining thermal conductivity are evaluated in Ismail et al., 2021 []. In this study, the authors, after carrying out various experiments, conclude that the thermal conductivity of maize husk is 0.030–0.125 W/mK. In the case of rice husk, Muthuraj et al., 2019, found its thermal conductivity to be 0.080 ± 0.001 W/mK []. Finally, in the case of bituminous coal, the thermal conductivity varies between 0.17 W/mK and 0.29 W/mK, according to Lett & Ruppel, 2004 [].

2.3. Equipment

In order to assess the thermal stability of the residues, an analysis was carried out using TGA (Thermogravimetric Analysis) curves in accordance with ASTM E1131 ‘Standard Test Method for Compositional Analysis by Thermogravimetry’, which provides a general technique for determining the amount of volatile matter, medium volatile matter, combustible matter and ash content in composites [].

The instrument used for the TGA experimental procedure was a TA Instruments Discovery TGA 550 manufactured by Waters Corporation in Milford, CT, USA, available in the Thermal Science Laboratory at ITM. This instrument offers a resolution of up to 0.1 µg, heating rates from 1 °C/min to 100 °C/min and can reach maximum temperatures of 1000 °C. Silica crucibles were used for the analysis.

The TGA was carried out in two steps. First, the samples were heated from room temperature to 600 °C in an oxidising atmosphere to assess oxidation and thermal decomposition. The analysis was then continued in a nitrogen inert atmosphere to characterise the carbonisation processes and to determine the final residues. These parameters ensured a clear distinction between oxidation reactions and pyrolysis or carbonisation processes.

2.4. Characteristics and Parameters of the TG

Once the TGA analyses had been carried out, the graphs obtained were evaluated. The temperature at which a significant increase in mass loss rate is observed indicates the ignition temperature, i.e., the temperature at which the biomass starts to burn in the presence of oxygen.

On the other hand, the burn-out temperature, which refers to the temperature at which a constant or minimal mass loss occurs during thermogravimetric analysis, is determined by observing the point at which there is no mass loss. This point indicates that all organic matter in the biomass has been completely oxidised, leaving only inorganic ash.

This approach is consistent with the findings of previous studies on the thermogravimetric behaviour of biomass and coal combustion. Examples of such studies include those by Peng et al. (2024) and Tsai & Han (2023) [,].

The amount of residual mass remaining at specific temperatures was calculated by comparing the initial sample mass and the residual mass obtained at the end of each heating stage. The residual mass percentage is determined using Equation (1):

where minitial is the mass of the sample at the start of the test, and mresidual is the mass remaining after thermal degradation at a given temperature. This metric provides insight into the ash content and thermal stability of the material.

The DTG (Derivative Thermogravimetric Analysis) curve, a technique for characterising materials and determining their thermal and decomposition properties, is then analysed. The DTG curve shows the rate of change in mass loss with respect to time or temperature, and peaks in the curve corresponding to different decomposition or mass loss processes in the material are identified. These peaks should be related to known or expected decomposition processes for the material under investigation.

From the DTG curves, the temperatures at which the peaks occur will be determined, which will be useful in understanding the thermal stability of the material and its behaviour under different conditions. The different DTG curves of the samples under different conditions will be compared to identify differences in the decomposition processes and thermal properties of the materials used.

The methodology used for identifying ignition and burnout temperatures, as well as the interpretation of DTG peaks, follows standard practices reported in the literature for the thermogravimetric characterization of solid fuels [,].

Finally, the combustibility index (S) was calculated using Equation (2), where is the maximum mass loss rate derived from the DTG curve (%/min) and and are the ignition and combustion temperatures (°C), respectively. Adapted from Shen et al. (2010) [] and applied in recent works such as Peng et al. (2024) and Tsai & Han (2023) [,], this index reflects the ease and intensity with which solid fuels burn under thermogravimetric conditions.

It is important to note that the thermogravimetric analyses were conducted as single representative runs for each fuel type, in line with the standard approach to thermal characterisation studies. The aim was to obtain comparative decomposition profiles under identical experimental conditions, rather than performing statistical comparisons of replicates.

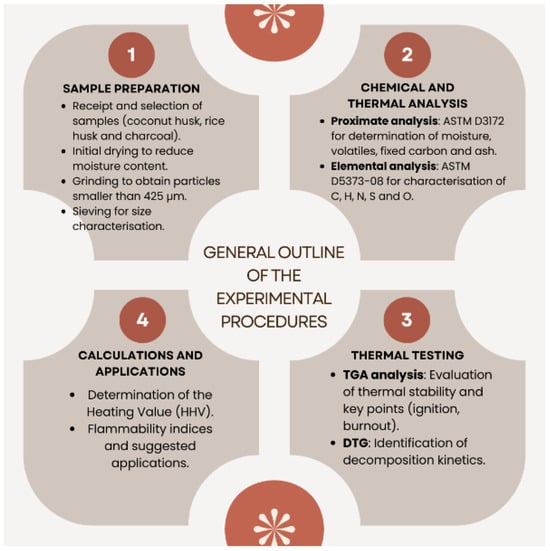

Figure 2 shows a schematic summary of the experimental procedures.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of all material and method processes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate and Ultimate Analysis

The elemental characterisation and proximate analysis of rice husk, Coconut Husk and mineral coal are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proximate analysis of rice husk, coconut husk, and mineral coal (results expressed on a wet basis).

To obtain the DAF values, the following Equation (3) was applied, where ‘X’ is the parameter on a wet basis and with ash.

Table 2 shows the results of the proximate and ultimate analyses on a dry basis.

Table 2.

Proximate and ultimate analysis on a dry basis (DAF) of rice husk, coconut husk and mineral coal.

The results of the proximate analysis are expressed on a wet basis (see Table 1), while the results of the ultimate analysis are expressed on a dry basis (see Table 2). The results of the proximate and ultimate analysis show significant differences in the chemical composition of the materials studied, which is reflected in their thermal properties []. Coconut Husk has a high content of volatile matter (53.48%) and fixed carbon (3.91%), indicating a good rapid combustion capacity and high heat production (HHV of 18 MJ/kg). Rice husk has a moderate volatile matter content (41.03%) and the highest fixed carbon content (11.64%), with a lower calorific value than Coconut Husk (HHV of 12.3 MJ/kg). The presence of silica (in CF) is remarkably high, which could affect its fuel performance. Mineral coal is the material with the highest carbon content (70.01%) and the lowest oxygen content, which gives it the highest calorific value (HHV of 24.38 MJ/kg). However, its high sulphur content (1.2%) could lead to higher pollutant emissions. Similarly, according to Table 2, mineral coal had the highest fixed carbon content (50.03%) and the lowest oxygen content (6.11%), which explains its higher thermal stability and higher calorific value (HHV: 29.91 MJ/kg). In comparison, Coconut Husk and rice husk, although having a lower fixed carbon content, had a higher oxygen content, which affected their thermal efficiency. These results are consistent with those reported by Awulu et al. 2018, who emphasised that a higher proportion of fixed carbon and lower oxygen favour the thermal efficiency of solid fuels [].

3.2. Empirical Formula

The molar quantity of each element was calculated using Equation (4), based on the mass percentage obtained through ultimate analysis on an ash-free, dry basis.

where %X is the percentage by weight of element X, and is the molar mass of element X in g/mol. This calculation, shown in Table 3, forms the basis for determining the empirical formula of each sample.

Table 3.

Molar composition of coconut husk, rice husk, and mineral coal (DAF basis).

The empirical formula of each fuel was derived by dividing all molar quantities by the value of carbon:

- Mineral coal: .

- Coconut husk: .

- Rice Husk: .

The empirical formula results show significant differences in the molar composition of the materials analysed, with direct implications for their combustion properties and energy efficiency.

The empirical formula of coal indicates a high carbon content and low oxygen content, suggesting high combustion efficiency and higher calorific value. However, the presence of sulphur can lead to polluting emissions, which is a concern for its environmental impact []. For Coconut Husk, it shows a balance between carbon and hydrogen, with a moderate oxygen content. This indicates a good combustion capacity, albeit with a lower calorific value than mineral coal. The low sulphur content of coconut husk biomass is an environmental advantage, making it a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels []. Finally, the empirical formula of rice husk shows a high hydrogen content compared to carbon and oxygen. This composition suggests faster and possibly cleaner combustion but with a lower calorific value than mineral coal and similar to that of Coconut Husk. The absence of sulphur in rice husk is a significant advantage, reducing the risk of sulphur oxide emissions during combustion [].

3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

TGA analyses were performed at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in accordance with the ASTM E1131 methodological specifications []. This parameter was chosen to ensure the samples were adequately thermally characterised and to minimise the side effects associated with extreme rates.

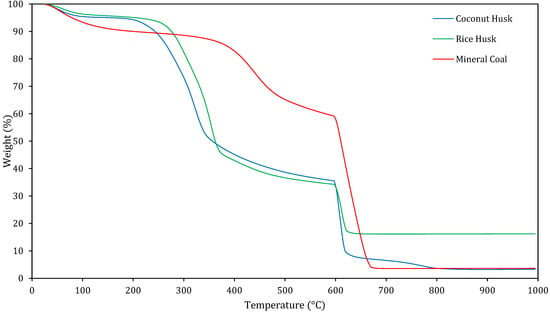

Figure 3 shows the TG curves of the three fuels under two different atmospheric conditions. From room temperature to 600 °C, the tests were performed in an inert atmosphere. Above 600 °C, an oxidising atmosphere was introduced.

Figure 3.

Thermogravimetric (TG) curves for coconut husk, rice husk and mineral coal.

These thermogravimetric analyses (TGAs) observe the weight loss of materials as a function of temperature. From room temperature to around 200 °C, slight mass loss is observed in all samples, primarily due to moisture evaporation and the release of extremely light volatile compounds.

Between 200 °C and 400 °C, the biomasses experience a more pronounced weight loss, which corresponds to the thermal degradation of hemicellulose and cellulose releasing a large proportion of their volatile matter. This stage is more evident in coconut husk and rice husk than in mineral coal due to their higher volatile content.

Between 400 and 600 °C, still under an inert atmosphere, the main process is the thermal decomposition of lignin, which is a more thermally stable component of biomass. Mass loss is slower in this range as lignin degradation produces a mixture of char and high-molecular-weight volatiles.

At 600 °C, the atmosphere changes from inert to oxidising. From this point onwards, the curves show a steep mass loss. For mineral coal, this mainly corresponds to the oxidation of fixed carbon, whereas for the biomasses it corresponds to the combustion of the char generated in the previous stage. This oxidation stage continues up to ~800 °C, after which the curves stabilise, indicating that only non-combustible ash remains.

The final residual mass is highest for rice husk due to its greater inorganic content, particularly silica, which is thermally stable under these conditions.

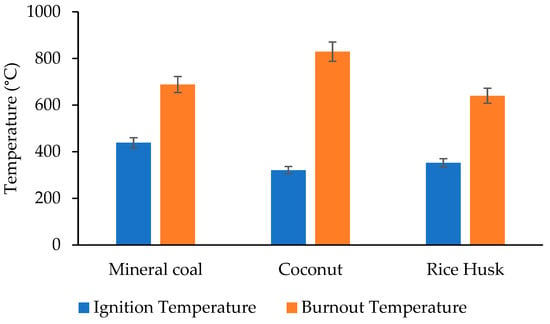

On the other hand, the TGA was used to determine the ignition temperature of each sample, which corresponds to the temperature at which a material begins to burn due to the onset of oxidation, identified by an abrupt change in the weight loss curve. Similarly, the burn-out temperature, which represents the point at which combustion is almost complete and the remaining mass loss is minimal, was determined for each type of biomass, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of ignition and burnout temperatures of the three materials.

The ignition temperature of mineral coal is the highest of the three materials (438.26 °C), indicating a higher initial thermal stability. The burnout temperature is also high (688.08 °C), indicating that mineral coal retains its structure at higher temperatures before completely decomposing. Coconut Husk has the lowest ignition temperature (320.88 °C), indicating that it decomposes more easily at lower temperatures. However, its burnout temperature is the highest (829.24 °C), indicating resistance to complete decomposition at high temperatures. Finally, rice husk has a medium ignition temperature (352.46 °C) and the lowest burnout temperature (640.01 °C), indicating that rice husk decomposes faster than the other materials.

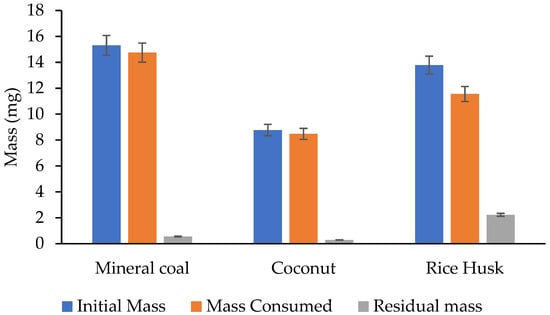

However, the analysis of the remaining residue provides information on the composition and stability of the sample, as well as the efficiency of the degradation processes or the elimination of volatiles. According to the TGA analyses, these residues are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Residue remaining from different materials.

For this case, Mineral coal leaves a significant residue after decomposition (0.5573 mg), reflecting its high ash content. Coconut Husk has the lowest remaining residue (0.2902 mg), indicating more complete combustion and less ash. And Rice Husk leaves a considerable amount of residue (2.231 mg), which may be related to its silica content. This behaviour is consistent with Muthuraj et al., 2019, who note that the presence of silica in biomass can limit its combustibility by reducing the proportion of volatile organic matter and fixed carbon available for thermal reaction [].

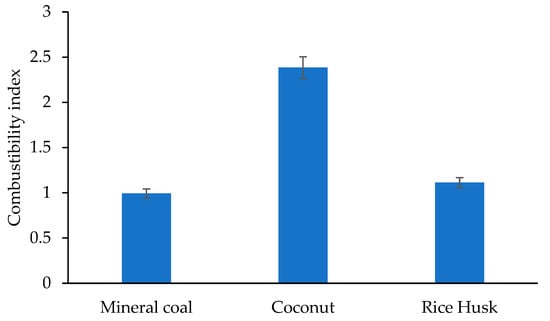

Finally, the combustibility index, which quantifies how easily a material can ignite and sustain combustion based on its thermal and compositional properties, is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Combustibility index of different materials.

The combustibility index of coconut husk (2.385) was the highest among the materials evaluated, positioning it as an ideal biomass for bioenergy applications such as biochar production or gasification. Although rice husk had a moderate index, its high ash content may limit its performance in these processes. On the other hand, although char had the lowest index, its higher thermal stability and calorific value are advantageous in high-demand energy systems [].

3.4. Differential Thermogravimetry (DTG)

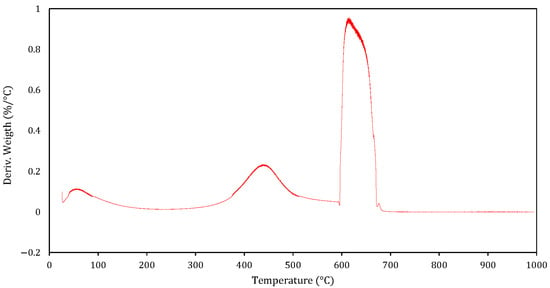

Figure 7 shows the DTG curve of mineral coal, representing the rate of weight change as a function of temperature. The test was conducted in an inert (N2) atmosphere from room temperature to 600 °C, followed by an oxidising (air) atmosphere from 600 °C to 1000 °C.

Figure 7.

Mineral coal DTG Curve.

Below 200 °C, a small, broad signal is observed, corresponding to the evaporation of physically adsorbed moisture and the release of very light volatile components. Between 200 °C and 400 °C, the DTG curve shows a slight rate increase, which is associated with the slow release of low-reactivity volatile matter and the initial transformation of some oxygen-containing functional groups.

A more distinct peak appears between 400 °C and 550 °C, corresponding to the gradual devolatilisation of coal’s more stable organic matter. This process occurs in an inert atmosphere and produces char, CO, CO2 and tars.

At 600 °C, the atmosphere changed to oxidising, producing a sharp, narrow peak—the highest in the curve—between 600 °C and ~670 °C. This intense, short event corresponds to the rapid combustion of the remaining fixed carbon in mineral coal. The pointed-tip profile indicates a fast oxidation rate, which is likely caused by the high reactivity of certain char fractions when they are suddenly exposed to oxygen.

Beyond 700 °C, the DTG signal approaches zero, indicating that only non-combustible ash remains and that the thermal reactions have finished.

This thermal behaviour highlights the distinct stages of coal reactivity—namely, moisture removal, slow devolatilisation and rapid char oxidation—which are essential for optimising industrial processes such as combustion for power generation and coal gasification for producing synthesis gas.

Figure 8 shows the DTG curve of coconut husk, representing the rate of weight change as a function of temperature. Analysis was conducted under an inert (N2) atmosphere from room temperature to 600 °C, followed by an oxidising (air) atmosphere from 600 °C to 1000 °C.

Figure 8.

Coconut Husk DTG curve.

Below 200 °C, a small and broad signal is observed, corresponding to the evaporation of physically adsorbed moisture and the release of light volatile compounds. Between 200 °C and 400 °C, a prominent peak appears, which is associated with the thermal decomposition of hemicellulose (which is less thermally stable and decomposes at lower temperatures) and cellulose (which is more crystalline and stable, peaking near 350–400 °C). These are the two main polysaccharides in lignocellulosic biomass [].

From 400 °C to ~550 °C, the DTG curve shows a broad signal related to the degradation of lignin: a complex aromatic polymer which decomposes slowly over a wide temperature range due to its heterogeneous, cross-linked structure. This stage occurs under an inert atmosphere and produces a porous char with a high fixed carbon content.

At 600 °C, switching to an oxidising atmosphere produces a sharp, intense peak corresponding to the rapid combustion of residual char. This event represents the oxidation of the fixed carbon matrix, which burns quickly due to the high surface area developed during pyrolysis.

Beyond 700 °C, the DTG signal approaches zero, indicating the completion of thermal reactions and the formation of non-combustible ash.

Understanding this staged thermal behaviour is essential for the industrial application of coconut husk in processes such as:

- (i) Activated carbon production, where the pyrolysis stage is optimised to maximise surface area;

- (ii) Biochar generation for soil improvement to benefit nutrient retention and microbial activity;

- (iii) Bioenergy production through combustion or co-combustion, where controlling the oxidation stage improves energy yield and reduces emissions.

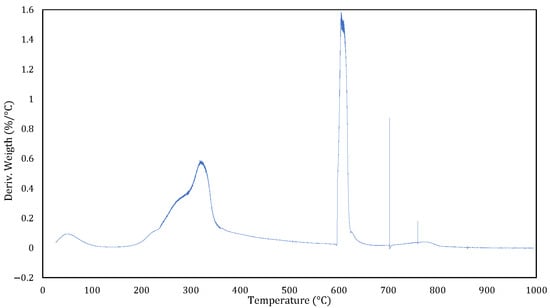

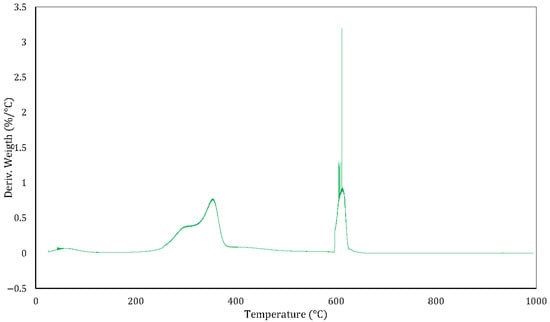

Figure 9 shows the DTG curve of rice husk, representing the rate of weight change as a function of temperature. Analysis was performed under an inert (N2) atmosphere from room temperature to 600 °C, followed by an oxidising (air) atmosphere from 600 °C to 1000 °C.

Figure 9.

Rice Husk DTG Curve.

Below 200 °C, a small, broad signal corresponding to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water and the release of very light volatiles is observed. Between 200 °C and 400 °C, a pronounced peak centred around 320–350 °C is evident. This is associated with the thermal degradation of hemicellulose (which decomposes at lower temperatures) and cellulose (which decomposes at higher temperatures within this range). This stage corresponds to the rapid devolatilisation of the polysaccharide fraction of the biomass.

From 400 °C to ~550 °C, the rate of weight change remains low but reflects the slow decomposition of lignin, which is a thermally resistant aromatic polymer. This process is less intense in rice husk than in coconut husk due to the higher ash content.

At 600 °C, when the atmosphere changes to oxidising, a very sharp, narrow peak appears, which is characteristic of the rapid combustion of residual char. The sharp peak indicates a fast oxidation event driven by the high surface area and porosity developed during pyrolysis combined with the relatively low fixed carbon content of rice husk.

After 650 °C, the DTG signal approaches zero, indicating the completion of thermal reactions and the presence of mainly silica-rich ash—a distinctive feature of rice husk. This composition opens up opportunities for non-energy applications, such as the extraction of silica for use in glass manufacturing, ceramics and advanced materials.

From an energy perspective, the staged decomposition behaviour is consistent with the typical thermal profile of lignocellulosic biomass [,]. However, the high mineral content, particularly silica, impacts combustibility. This makes rice husk more suitable for material recovery applications than direct combustion, unless pre-treatment or blending with fuels containing a higher fixed carbon content is implemented.

3.5. Comparison with Previous Studies

To emphasise the novelty and contextual relevance of this research, Table 4 compares thermochemical data for coconut husk, rice husk and mineral coal reported in previous literature. As can be seen, while individual characterisations exist, few studies have performed direct comparisons under uniform experimental conditions, particularly with the simultaneous use of TGA, DTG and combustibility indices.

Table 4.

Comparison of thermochemical properties with previous studies.

This table shows that, although the thermochemical characterisation of these materials has been studied individually, this work brings them together under standardised laboratory conditions using the same TGA protocol, heating rate and analytical techniques. Furthermore, including the combustibility index as a comparative metric provides an additional decision-making criterion that is rarely reported alongside TGA/DTG data.

4. Conclusions

This study compared the thermochemical properties of coconut husk, rice husk and mineral coal under identical laboratory conditions. Proximate and ultimate analyses, thermogravimetric evaluations and combustibility index calculations were used to make the comparison.

Mineral coal exhibited the highest carbon content and calorific value (29.91 MJ/kg), indicating superior energy density, though its elevated sulphur content (1.47%) raises environmental concerns. Coconut husk had the lowest ignition temperature (320.88 °C) and the highest combustibility index (2.385), highlighting its suitability for rapid combustion, biochar production and small-scale renewable energy applications. Rice husk had a lower calorific value and high ash content due to its silica concentration, making it more suitable for non-energy applications such as silica recovery or use in advanced materials.

These results confirm the potential of coconut and rice husks as partial substitutes for mineral coal, contributing to cleaner energy strategies and the goals of the circular economy. While biomass–coal blends were not tested experimentally, thermogravimetric data provide a technical basis for predicting their combustion performance. Future work will focus on evaluating different blending ratios to optimise the efficiency, stability and emission control of co-firing systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.S.-G. and K.P.C.M.; methodology, S.J.S.-G. and J.D.R.-J.; validation, S.J.S.-G., J.D.R.-J. and J.M.M.-F.; formal analysis, S.J.S.-G.; investigation, S.J.S.-G., K.P.C.M. and J.D.R.-J.; resources, F.L.A.-I.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.S.-G.; writing—review and editing, J.M.M.-F.; visualization, K.P.C.M.; supervision, S.J.S.-G.; project administration, S.J.S.-G.; funding acquisition, F.L.A.-I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad del Sinú—Elías Bechara Zainúm (project number CI-00423-006), and the article processing charge (APC) was funded by Universidad del Sinú—Elías Bechara Zainúm.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this research are grateful to the Universidad del Sinú—Elías Bechara Zainúm, in the framework of the internal project entitled “ANÁLISIS DEL RENDIMIENTO ENERGÉTICO Y LAS EMISIONES DE LA CO-COMBUSTIÓN DE BIOMASA CON CARBÓN MINERAL COMO ALTERNATIVA DE LA TRANSICIÓN ENERGÉTICA”, approved in the internal call UNISINÚ INVESTIGA 2023. The financial support facilitated the successful completion of the research and contributed to the advancement of knowledge in the field of energy transition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Rygg, B.J. A Review of Dominant Sustainable Energy Narratives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofán-Germán, S.J.; Mendoza-Fandiño, J.M.; Rhenals-Julio, J.D.; Gómez, R.D. CFD Simulation Applying a Discrete Phase Model of Residual Corn Biomass Gasification in a Concentric Tube Reactor. J. Southwest. Jiaotong Univ. 2023, 58, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C. 1.2. Panorámica Energética Mundial. In Energética del Hidrógeno. Contexto, Estado Actual Y Perspectivas de Futuro; 2018; pp. 20–37, [En línea]; Available online: https://biblus.us.es/bibing/proyectos/abreproy/3823/fichero/1.2+Panorámica+Energética+Mundial.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Montenegro, C. Estimación de La Elasticidad de La Demanda de Energía Eléctrica En El Sector Industrial de Colombia Para El Año 2018; Universidad Santiago de Cali: Cali, Colombia, 2020; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Linares, P. La Energía. Retos y Problemas. Dossieres EsF: La Energía. Retos Y Probl. 2017, 24, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgwater, A.V. The Technical and Economic Feasibility of Biomass Gasification for Power Generation. Fuel 2015, 74, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagastume Gutiérrez, A.; Mendoza Fandiño, J.M.; Cabello Eras, J.J.; Sofan German, S.J. Potential of Livestock Manure and Agricultural Wastes to Mitigate the Use of Firewood for Cooking in Rural Areas. The Case of the Department of Cordoba (Colombia). Dev. Eng. 2022, 7, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello Eras, J.J.; Mendoza Fandiño, J.M.; Sagastume Gutiérrez, A.; Rueda Bayona, J.G.; Sofan German, S.J. The Inequality of Electricity Consumption in Colombia. Projections and Implications. Energy 2022, 249, 23711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Fandiño, J.M.; Sofán German, S.J.; López García, D.E.; Guarín, A.M.; Rhenals Julio, J.D. Caracterização Energética Dos Resíduos Da Agroindústria Do Milho Em Um Protótipo de Gaseificação Multizona. Rev. Virtual De Quim. 2022, 14, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segurado, R.; Pereira, S.; Correia, D.; Costa, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Trigeneration System Based on Biomass Gasification. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Possibility of Utilizing Agriculture Biomass as a Renewable and Sustainable Future Energy Source. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Rahman Mahmud, A.; Maneengam, A.; Nassani, A.A.; Haffar, M.; The Cong, P. Non Linear Effect of Biomass, Fossil Fuels and Renewable Energy Usage on the Economic Growth: Managing Sustainable Development through Energy Sector. Fuel 2022, 326, 124943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadh, P.K.; Duhan, S.; Duhan, J.S. Agro-Industrial Wastes and Their Utilization Using Solid State Fermentation: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, S.V.; Daioglou, V.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Frank, S.; Popp, A.; Brunelle, T.; Lauri, P.; Hasegawa, T.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Van Vuuren, D.P. Biomass Residues as Twenty-First Century Bioenergy Feedstock—A Comparison of Eight Integrated Assessment Models. Clim. Change 2020, 163, 1569–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Golzary, A. Challenges, Recent Development, and Opportunities of Smart Waste Collection: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 886, 163925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, F.A.; Shovon, S.M.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, W.; Chakraborty, P.; Haque, M.N.; Monir, M.U.; Habib, M.A.; Biswas, A.K.; Chowdhury, S.; et al. Innovative Pathways to Sustainable Energy: Advancements in Clean Coal Technologies in Bangladesh—A Review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 22, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria Oviedo, M.; Mendoza, J.M.; Sofan-German, S.; Rhenals-Julio, J.D. Effect of Biomass Addition on Sox, Nox, and Co2 Emissions during Cofiring of Pulverized Coal. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2024, 59, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agronet Reporte Estadisticas: Participación Departamental En La Producción y En El Área Cosechada. Available online: https://www.agronet.gov.co/estadistica/Paginas/home.aspx?cod=2 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Forero-Nuñez, C.A. Characterization and Feasibility of Solid Biofuels Made of Colombian Timber, Coconut and Oil Palm Residues Regarding European Standards. Environ. Biotechnol. 2012, 8, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Awulu, J.O.; Omale, P.A.; Ameh, J.A. Comparative analysis of calorific values of selected agricultural wastes. Niger. J. Technol. (NIJOTECH) 2018, 37, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia, G.R.O.; Blandón, A.; Perea, C.; Mastalerz, M. Petrographic Characterization, Variations in Chemistry, and Paleoenvironmental Interpretation of Colombian Coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2020, 227, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.C.R.; Tannous, K. Coconut Fiber Pyrolysis: Specific Heat Capacity and Enthalpy of Reaction through Thermogravimetry and Differential Scanning Calorimetry: 504527. Thermochim. Acta 2022, 707, 179087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.; Tadeu, A.; António, J.; Almeida, J.; de Brito, J. Mechanical, Thermal and Acoustic Behaviour of Polymer-Based Composite Materials Produced with Rice Husk and Expanded Cork by-Products. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 239, 117851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Engineering ToolBox. Solids—Specific Heats. Available online: https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/specific-heat-solids-d_154.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ismail, I.; Hatta, Z.N.; Mursal; Jalil, Z.; Md Fadzullah, S.H.S. Thermal Conductivity of Coconut Shell Particle Epoxy Resin Composite. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1816, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuraj, R.; Lacoste, C.; Lacroix, P.; Bergeret, A. Sustainable Thermal Insulation Biocomposites from Rice Husk, Wheat Husk, Wood Fibers and Textile Waste Fibers: Elaboration and Performances Evaluation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 135, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, R.G.; Ruppel, T.C. Coal, Chemical and Physical Properties. In Encyclopedia of Energy; Cleveland, C.J., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 411–423. ISBN 978-0-12-176480-7. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Tang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, C.; Wu, W. Combustion Characteristics and Thermokinetics of Coconut Shell, Coal Water Slurry, and Biomass. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2024, 137, 2003–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-T.; Han, J.-W. Thermochemical Characterization of Husk Biomass Resources with Relevance to Energy Use. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 8061–8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.K.; Gu, S.; Luo, K.H.; Wang, S.R.; Fang, M.X. The Pyrolytic Degradation of Wood-Derived Lignin from Pulping Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 6136–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racero-Galaraga, D.; Rhenals-Julio, J.D.; Sofan-German, S.; Mendoza, J.M.; Bula-Silvera, A. Proximate Analysis in Biomass: Standards, Applications and Key Characteristics. Results Chem. 2024, 12, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preeti; Mohod, A.G.; Khandetod, Y.P.; Dhande, K.G.; Sawant, P.A. Physico-Chemical Characterization of Coconut Shell (Cocos nucifera). Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Darkwa, J.; Kokogiannakis, G. Review of Solid–Liquid Phase Change Materials and Their Encapsulation Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).