Monitoring the Transformation of Organic Matter During Composting Using 1H NMR Spectroscopy and Chemometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composting Substrate and Pile Composition

2.2. Composting Process, Sampling, and Extraction of Soluble Organic Matter

2.3. 1H NMR Spectroscopy

2.4. Chemometric Analysis

3. Results

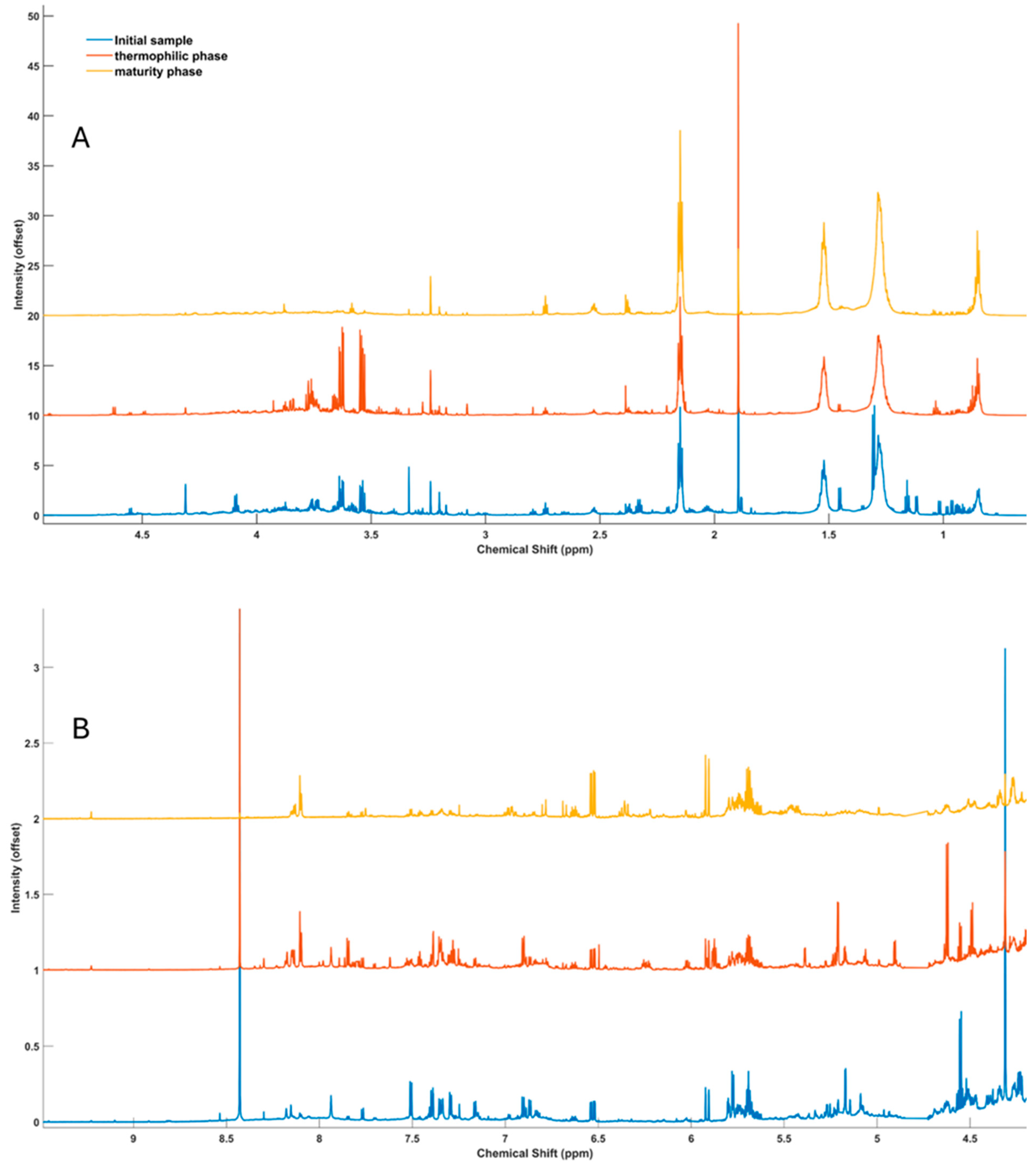

3.1. General Spectral Characteristics of Soluble Organic Matter

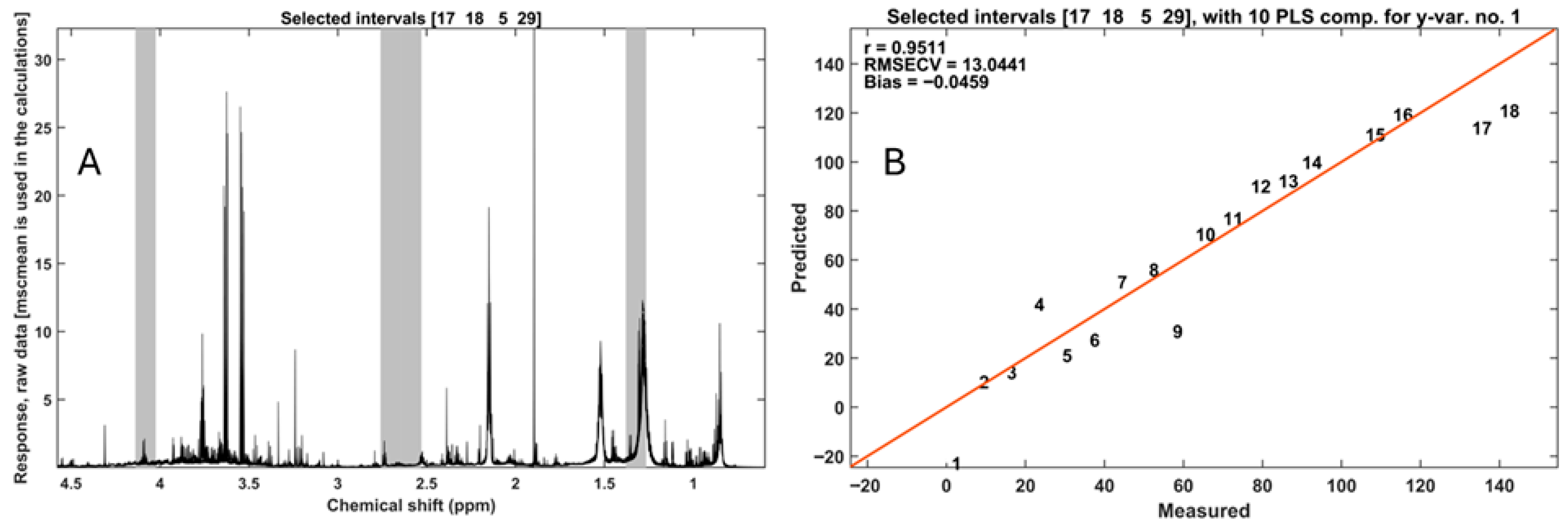

3.2. Chemometric Analysis of Composting Progress

4. Discussion

4.1. Molecular Trajectory of WEOM During Composting

4.2. Rapid Turnover of Amino Acids and Sugars, and Consequences for Process Control

4.3. Winery-Specific Molecular Fingerprints and Their Mechanistic Basis

4.4. Minor Constituents That Inform on Pathway Chemistry

4.5. From Qualitative Fingerprints to Quantitative Prediction

4.6. Practical Implications for Compost Monitoring and Quality Assurance

4.7. Limitations and Avenues for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreno-Casco, J.; Moral-Herrero, R. Compostaje; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; Martinez-Sabater, E.; Jorda, J.; Moral, R.; Bustamante, M.A.; Paredes, C.; Perez-Murcia, M.D. Dissolved organic matter fractions formed during composting of winery and distillery residues: Evaluation of the process by fluorescence excitation-emission matrix. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Abate, M.T.; Benedetti, A.; Sequi, P. Thermal methods of organic matter maturation monitoring during a composting process. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2000, 61, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrán, E.; Sort, X.; Soliva, M.; Trillas, I. Composting winery waste: Sludge and grape stalks. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 95, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, M.R.; de Oliveira, S.C.; da Silva, M.R.; Senesi, N. Assessment of maturity degree of composts from domestic solid wastes by fluorescence and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5874–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, M.R.; Malerba, A.D.; Pezzolla, D.; Gigliotti, G. Chemical and spectroscopic characterization of organic matter during the anaerobic digestion and successive composting of pig slurry. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Paredes, C.; Vargas-García, M.C.; Suárez-Estrella, F.; Moreno, J. Evolution of the pathogen content during co-composting of winery and distillery wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 7299–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youness, B.; Lyamlouli, K.; Oudouch, Y.; El Boukhari Mohamed, E.M.; Hafidi, M. Agronomic assessment of solar dried recycled olive mill sludge on Maize agrophysiological traits and soil fertility. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2022, 11, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Paredes, C.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; Pérez-Espinosa, A.; Bernal, M.P.; Moral, R. Co-composting of distillery wastes with animal manures: Carbon and nitrogen transformations in the evaluation of compost stability. Chemosphere 2008, 72, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Inbar, Y. Chemical and spectroscopical analyses of organic matter transformations during composting in relation to compost maturity. In Science and Engineering of Composting: Design, Environmental, Microbiological and Utilization Aspects; Hoitink, H.A.J., Keener, H.M., Eds.; Renaissance Publications: Worthington, OH, USA, 1993; pp. 551–600. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, R.T. The Practical Handbook of Compost Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, S.; Dhull, S.K.; Kapoor, K.K. Chemical and biological changes during composting of different organic wastes and assessment of compost maturity. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, M.P.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Moral, R. Composting of animal manures and chemical criteria for compost maturity assessment: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5444–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.M.; Siddiqi, S.A.; Farooque, A.A.; Iqbal, Q.; Shahid, S.A.; Akram, M.T.; Rahman, S.; Al-Busaidi, W.; Khan, I. Towards Sustainable Application of Wastewater in Agriculture: A Review on Reusability and Risk Assessment. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikae, M.; Ikeda, R.; Kerman, K.; Morita, Y.; Tamiya, E. Estimation of maturity of compost from food wastes and agro-residues by multiple regression analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.J. Determining the molecular weight, aggregation, structures and interactions of natural organic matter using diffusion ordered spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2002, 40, S72–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, M.H. Spin Dynamics: Basics of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, C.M. Applications of NMR to soil organic matter analysis: History and prospects. Soil Sci. 1996, 161, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, L.; Saudland, A.; Wagner, J.; Nielsen, J.P.; Munck, L.; Engelsen, S.B. Interval Partial Least-Squares Regression (iPLS): A Comparative Chemometric Study with an Example from Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2000, 54, 413–419. Available online: https://opg.optica.org/as/abstract.cfm?URI=as-54-3-413 (accessed on 24 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Winning, H.; Viereck, N.; Nørgaard, L.; Larsen, K.L.; Engelsen, S.B. Quantification of the degree of blockiness in pectins using 1H NMR spectroscopy and chemometrics. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstein, M.S.; Miller, F.C.; MacGregor, S.T.; Psarianos, K.M. The Rutgers Strategy for Composting: Process Design and Control; U.S. EPA Water Engineering Research Laboratory: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1985.

- Torres-Climent, A.; Gomis, P.; Martin-Mata, J.; Bustamante, M.A.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; Perez-Murcia, M.D.; Perez-Espinosa, A.; Paredes, C.; Moral, R. Chemical, Thermal and Spectroscopic Methods to Assess Biodegradation of Winery-Distillery Wastes during Composting. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel-Knabner, I. Analytical approaches for characterizing soil organic matter. Org. Geochem. 2000, 31, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Weimer, P.J.; van Zyl, W.H.; Pretorius, I.S. Microbial cellulose utilization: Fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 506–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalbot, M.C.; Siddiqui, S.; Kavouras, I.G. Molecular Speciation of Size Fractionated Particulate Water-Soluble Organic Carbon by Two-Dimensional Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, C.; Cai, R.; Xin, L.; Li, Y.; Ke, L.; Ye, W.; Ouyang, T.; Liang, J.; Wu, R.; et al. NMR and MS reveal characteristic metabolome atlas and optimize esophageal squamous cell carcinoma early detection. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, L.; Gomez-Requeni, P.; Moazzami, A.A.; Lundh, T.; Vidakovic, A.; Langeland, M.; Kiessling, A.; Pickova, J. 1H NMR-based metabolomics and lipid analyses revealed the effect of dietary replacement of microbial extracts or mussel meal with fish meal to arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus). Fishes 2019, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.W.; Beauchamp, E.G. Short-term effects of nitrogen fertilizers, liming, and straw on volatile fatty acid production in poultry manure. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1989, 8, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, C. Volatile fatty acids recovery from poultry manure: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Pullicino, D.; Erriquens, F.G.; Gigliotti, G. Changes in the water extractable organic matter during composting of municipal solid wastes. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caricasole, P.; Provenzano, M.R.; Hatcher, P.G.; Senesi, N.; Brunetti, G. Composting of municipal solid wastes: Characterization of organic matter by CPMAS 13C NMR spectroscopy. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Logan, T.J.; Traina, S.J. Physical and chemical characteristics of water extractable organic matter from composts. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.T.; Roberts, P.; Tonheim, S.K.; Jones, D.L. Protein breakdown represents a major bottleneck in nitrogen cycling in grassland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 2272–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Tobón-Cornejo, S.; Velazquez-Villegas, L.A.; Noriega, L.G.; Alemán-Escondrillas, G.; Tovar, A.R. Amino Acid Catabolism: An Overlooked Area of Metabolism. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Li, X.; Duan, X.; Gou, C.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y. Development of a microbial protease for composting swine carcasses, optimization of its production and elucidation of its catalytic hydrolysis mechanism. BMC Biotechnol. 2022, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fels, L.; Naylo, A.; Jemo, M.; Zrikam, N.; Boularbah, A.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Hafidi, M. Microbial enzymatic indices for predicting composting quality of recalcitrant lignocellulosic substrates. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1423728. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1423728 (accessed on 24 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vranova, V.; Zahradnickova, H.; Janous, D.; Skene, K.R.; Matharu, A.S.; Rejsek, K.; Formanek, P. The significance of D-amino acids in soil, fate and utilization by microbes and plants: Review and identification of knowledge gaps. Plant Soil 2012, 354, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, H.; Fujino, Y.; Doi, K.; Ohshima, T. Highly stable meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase from an Ureibacillus thermosphaericus strain A1 isolated from a Japanese compost: Purification, characterization and sequencing. AMB Express 2011, 1, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Mao, I.; Valls Fonayet, J.; Wirth, J. NMR-based metabolomics applied to wine quality analysis. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, E. Typical values for fats, proteins and salt in Australian wine for nutritional labelling. AWRI Tech. Rev. 2023, No. 266. Available online: https://www.awri.com.au/information_services/technical_review/technical-notes/technical-note-typical-values-for-fats-proteins-and-salt-in-australian-wine-for-nutritional-labelling/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Zacharof, M.P. Grape winery waste as feedstock for bioconversion: Applying the biorefinery concept. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Pereira, H. Methanolysis of bark suberins: Analysis of glycerol and acid monomers. Phytochem. Anal. 2000, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, N.; Belgacem, M.N.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Neto, C.P.; Gandini, A. Cork suberin as a new source of chemicals. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1998, 22, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caricasole, P.; Provenzano, M.R.; Hatcher, P.G.; Senesi, N. Chemical characteristics of dissolved organic matter during composting of different organic wastes assessed by 13C CPMAS NMR spectroscopy. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8232–8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Liao, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, S. Hyperthermophilic composting accelerates the humification process of sewage sludge: Molecular characterization of dissolved organic matter using EEM–PARAFAC and two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 274, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; Rocha, P.; Valderrama, P.; Antelo, J.; Geraldo, D.; Proença, M.F.; Fiol, S.; Bento, F. A Correlation-Based Approach for Predicting Humic Substance Bioactivity from Direct Compost Characterization. Molecules 2025, 30, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, M.; Baigorri, R.; González-Gaitano, G.; García-Mina, J.M. The complementary use of 1H NMR, 13C NMR, FTIR and size exclusion chromatography to investigate the principal structural changes associated with composting of organic materials with diverse origin. Org. Geochem. 2007, 38, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. International Code of Oenological Practices; Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin: Dijon, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.-K.; Lee, Y.-J.; Han, G.H.; Yeom, S.-J. Methanol Dehydrogenases as a Key Biocatalysts for Synthetic Methylotrophy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 787791. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/bioengineering-and-biotechnology/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2021.787791 (accessed on 24 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vu Huong, N.; Subuyuj Gabriel, A.; Vijayakumar, S.; Good Nathan, M.; Martinez-Gomez, N.C.; Skovran, E. Lanthanide-Dependent Regulation of Methanol Oxidation Systems in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and Their Contribution to Methanol Growth. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, F.; Hamilton, J.T.G.; McRoberts, W.C.; Vigano, I.; Braß, M.; Röckmann, T. Methoxyl groups of plant pectin as a precursor of atmospheric methane: Evidence from deuterium labelling studies. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, M.C.; Pratscher, J.; Crombie, A.T.; Murrell, J.C. Impact of plants on the diversity and activity of methylotrophs in soil. Microbiome 2020, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Fernández-Hernández, A.; Higashikawa, F.S.; Cayuela, M.L. Relationships between emitted volatile organic compounds and their concentration in the pile during municipal solid waste composting. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leardi, R.; Nørgaard, L. Sequential application of backward interval partial least squares and genetic algorithms for the selection of relevant spectral regions. J. Chemom. 2004, 18, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sabater, E.; Bustamante, M.A.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C.; El-Khattabi, M.; Moral, R.; Lorenzo, E.; Paredes, C.; Gálvez, L.N.; Jordá, J.D. Study of the evolution of organic matter during composting of winery and distillery residues by classical and chemometric analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9613–9623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, R.; Coromina, N.; Marfà, O. Composting of greenhouse tomato plant residues: Maturity assessment and agronomic value. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhle, L.; Wold, S. Partial least squares analysis with cross-validation for the two-class problem: A Monte Carlo study. J. Chemom. 1987, 1, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbensen, K.H.; Geladi, P. Principles of Proper Validation: Use and abuse of re-sampling for validation. J. Chemom. 2010, 24, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trygg, J.; Wold, S. Orthogonal projections to latent structures (O-PLS). J. Chemom. 2002, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour-Rainfray, D.; Lambérioux, M.; Boulard, P.; Guidotti, M.; Delaye, J.; Ribeiro, M.; Gauchez, A.; Balageas, A.; Emond, P.; Agin, A. Metabolomics—An overview. From basic principles to potential biomarkers (part 2). Med. Nucl.-Imag. Fonct. Metab. 2020, 44, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümich, B. Low-field and benchtop NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2019, 306, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peak | δ (ppm) | Compound | Multiplicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.779 | unassigned | d |

| 2 | 0.823 | 2-Hydroxyvalerate | d |

| 3 | 0.852 | Caprate | t |

| 4 | 0.859 | Octenoate | t |

| 5 | 0.874 | Valerate | t |

| 6 | 0.892 | Isovalerate | t |

| 7 | 0.923 | Isoleucine | t |

| 8 | 0.948 | Leucine | t |

| 9 | 0.978 | Valine | d |

| 10 | 0.998 | Leucine | d |

| 11 | 1.030 | Valine | d |

| 12 | 1.132 | Proppylene glycol | d |

| 13 | 1.164 | Isopropanol | d |

| 14 | 1.169 | Ethanol | t |

| 15 | 1.189 | 3-Hydroxybutirate | d |

| 16 | 1.294 | Suberate | m |

| 17 | 1.319 | Lactate | d |

| 18 | 1.367 | Acetoine | d |

| 19 | 1.468 | Alanine | d |

| 20 | 1.531 | Suberate | t |

| 21 | 1.682 | Leucine | m |

| 22 | 1.851 | Timidine | s |

| 23 | 1.894 | 1-aminocyclopropane carboxilic acid | t |

| 24 | 1.907 | Acetate | s |

| 25 | 2.045 | Glutamate | m |

| 26 | 2.121 | Glutamate | m |

| 27 | 2.164 | Suberate | t |

| 28 | 2.210 | Levulinate | s |

| 29 | 2.346 | Glutamate | m |

| 30 | 2.384 | Levulinate | t |

| 31 | 2.423 | Oxoglutarate | t |

| 32 | 2.533 | Guanidine succinate | m |

| 33 | 2.665 | Aspartate | dd |

| 34 | 2.738 | Sarcosine | s |

| 35 | 2.748 | Levulinate | t |

| 36 | 2.789 | Aspartate | dd |

| 37 | 2.800 | Methyl guanidine | s |

| 38 | 2.882 | TMA | s |

| 39 | 2.920 | N,N-Dimethylglicine | s |

| 40 | 3.092 | unassigned | s |

| 41 | 3.115 | Malonate | s |

| 42 | 3.180 | Choline | s |

| 43 | 3.216 | sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine | s |

| 44 | 3.242 | TMAO | s |

| 45 | 3.289 | Xylose | t |

| 46 | 3.346 | Methanol | s |

| 47 | 3.417 | Propylene glycol | q |

| 48 | 3.547 | Glycerol | m |

| 49 | 3.596 | 4-Hydroxybutirate | t |

| 50 | 3.649 | Glycerol | m |

| 51 | 3.656 | Ethylene glycol | s |

| 52 | 3.670 | Ethanol | q |

| 53 | 3.744 | Glutamate | m |

| 54 | 3.766 | Glycerol | m |

| 55 | 3.886 | Betaine | s |

| 56 | 3.895 | Aspartate | m |

| 57 | 4.099 | Lactate | q |

| 58 | 4.322 | Tartrate | s |

| 59 | 4.559 | Xylose | d |

| 60 | 5.180 | Xylose | d |

| 61 | 5.701 | unassigned | t |

| 62 | 5.717 | Cis-aconitate | s |

| 63 | 5.791 | Uracil | d |

| 64 | 5.812 | 2-Octanoate | dt |

| 65 | 5.931 | Gibberelline | d |

| 66 | 5.966 | cis-cis-Muconate | dd |

| 67 | 6.534 | Gibberelline | dq |

| 68 | 6.648 | 2-Octanoate | dt |

| 69 | 6.827 | 2-Aminobenzoic | ddd |

| 70 | 6.850 | 2-Aminobenzoic | dd |

| 71 | 6.884 | Tyrosine | d |

| 72 | 6.927 | 4-Hydroxybenzoate | d |

| 73 | 7.170 | Tyrosine | d |

| 74 | 7.264 | Syringate | s |

| 75 | 7.316 | Phenylalanine | d |

| 76 | 7.348 | Thymine | s |

| 77 | 7.358 | 2-Aminobenzoic | ddd |

| 78 | 7.368 | Phenylalanine | t |

| 79 | 7.401 | Phenylalanine | d |

| 80 | 7.521 | Uracyl | d |

| 81 | 7.718 | 2-Aminobenzoic | dd |

| 82 | 7.787 | 4-Hydroxybenzoate | d |

| 83 | 7.863 | Benzoate | d |

| 84 | 7.953 | Xanthine | s |

| 85 | 8.073 | Trigonelline | m |

| 86 | 8.123 | unassigned | d |

| 87 | 8.171 | Hypoxantine | s |

| 88 | 8.196 | Hypoxantine | s |

| 89 | 8.439 | Formic acid | s |

| 90 | 8.822 | Trigonelline | m |

| 91 | 8.927 | Nicotinate | d |

| 92 | 9.112 | Trigonelline | s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonsálvez-Álvarez, R.; Martínez-Sabater, E.; Bustamante, M.Á.; Piccioli, M.; Saez-Tovar, J.A.; Orden, L.; Paredes, C.; Moral, R.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C. Monitoring the Transformation of Organic Matter During Composting Using 1H NMR Spectroscopy and Chemometric Analysis. Biomass 2025, 5, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040076

Gonsálvez-Álvarez R, Martínez-Sabater E, Bustamante MÁ, Piccioli M, Saez-Tovar JA, Orden L, Paredes C, Moral R, Marhuenda-Egea FC. Monitoring the Transformation of Organic Matter During Composting Using 1H NMR Spectroscopy and Chemometric Analysis. Biomass. 2025; 5(4):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040076

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonsálvez-Álvarez, Rubén, Encarnación Martínez-Sabater, María Ángeles Bustamante, Mario Piccioli, José A. Saez-Tovar, Luciano Orden, Concepción Paredes, Raúl Moral, and Frutos C. Marhuenda-Egea. 2025. "Monitoring the Transformation of Organic Matter During Composting Using 1H NMR Spectroscopy and Chemometric Analysis" Biomass 5, no. 4: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040076

APA StyleGonsálvez-Álvarez, R., Martínez-Sabater, E., Bustamante, M. Á., Piccioli, M., Saez-Tovar, J. A., Orden, L., Paredes, C., Moral, R., & Marhuenda-Egea, F. C. (2025). Monitoring the Transformation of Organic Matter During Composting Using 1H NMR Spectroscopy and Chemometric Analysis. Biomass, 5(4), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomass5040076