Abstract

We investigate a ferrimagnetic/ferroelectric bilayer in which a mixed-spin Heisenberg ferrimagnet is coupled to a three-state ferroelectric layer allowing for a nonpolar state. Using Monte Carlo simulations, we analyze how magnetic and electric single-ion anisotropies, together with interfacial magnetoelectric coupling, control phase transitions and hysteresis properties. We show that electric anisotropy, by tuning the population of nonpolar ferroelectric sites, strongly shifts the ferrimagnetic critical temperature, while magnetic anisotropy reciprocally affects the ferroelectric transition. Increasing the magnetoelectric coupling enhances both ordering temperatures and may induce a common transition. At fixed temperature, magnetic and electric hysteresis loops evolve from square to slim and nearly reversible shapes as anisotropies are varied. These results highlight the relevance of three-state ferroelectricity for describing polarization suppression and tunable magnetoelectric response in hybrid bilayers.

1. Introduction

Multiferroic and magnetoelectric hybrid systems attract strong theoretical and experimental interest because they couple electric and magnetic functionalities within nanoscale architectures, making them promising for nonvolatile memories, spin-based logic, field-controlled magnetic switching, and low-power multifunctional devices [1,2,3,4]. Artificial heterostructures combining ferroelectric (FE) and magnetic layers constitute one of the most versatile routes to engineer magnetoelectric (ME) coupling, owing to their tunable geometry, interfacial-strain effects, and controllable electronic or dipolar interactions [5,6,7].

Recent experiments [8,9,10] have further demonstrated that ferroelectric or piezoelectric layers can provide an efficient electrical handle to tune magnetic switching in nanoscale heterostructures, including ferroelectric-assisted spin–orbit-torque switching in heavy-metal/ferromagnet stacks on PMN-PT substrates, as well as voltage-controlled switching in ferroelectric/ferrimagnet systems such as PZT/CoGd. These advances motivate minimal theoretical models that isolate generic interfacial magnetoelectric mechanisms and their impact on phase transitions and hysteresis.

Considerable progress has been made in understanding ME phenomena in layered structures, particularly bilayers and superlattices incorporating ferromagnetic (FM) or ferrimagnetic (FI) components. In these systems, magnetic layers are commonly described by Heisenberg or mixed-spin Hamiltonians, while ferroelectric layers are often modeled using classical two-state Ising-type dipoles (±1) [11,12,13,14]. These discrete models successfully capture order-disorder transitions, hysteresis, and interface-mediated coupling and remain computationally tractable for large-scale Monte Carlo (MC) simulations.

However, conventional two-state ferroelectric models impose a fully polarized local configuration at low temperature and therefore cannot capture intermediate nonpolar regions or partial polarization suppression commonly observed in real ferroelectrics, particularly in thin films and relaxor systems [15,16,17,18]. A more flexible approach introduces an additional nonpolar state, , as in spin-1 Blume-Capel-type ferroelectric models [19,20,21]. The associated crystal-field controls the relative stability of polar and nonpolar configurations and enables richer phase behavior, including broadened susceptibility peaks and relaxor-like features [22,23].

While Blume-Capel-type ferroelectric models have been successfully applied to purely electric systems and to the study of structural phase transitions, their implementation in hybrid magnetoelectric bilayers remains limited. Most existing magnetoelectric studies rely on two-state Ising ferroelectrics [11,12,13,14], including recent FI-FE-FM trilayer models in which the ferroelectric layer is restricted to [24]. In this context, a bilayer combining a ferrimagnetic Heisenberg layer with a three-state ferroelectric layer explicitly governed by a single-ion electric anisotropy and coupled through an interfacial magnetoelectric interaction has not yet been systematically investigated. Such a framework is particularly well suited to describe polarization suppression, reduced interfacial coupling, and the emergence of slim hysteresis loops in ultrathin hybrid structures.

In this work, we fill this gap by formulating and simulating a minimal FI/FE bilayer where the magnetic layer consists of two anti-aligned Heisenberg sublattices ( and ), while the FE layer follows a three-state pseudo-Ising model (). The ME interaction is implemented as a direct interfacial coupling between the FE dipoles and the out-of-plane magnetic components. Monte Carlo simulations are used to explore the thermodynamic and hysteretic properties of the system, emphasizing the effects of the crystal-field parameter and the magnetoelectric coupling.

The goal of this study is twofold. First, we examine how the inclusion of a nonpolar ferroelectric state modifies the thermodynamic behavior of a magnetoelectric bilayer. Second, we quantify how the single-ion anisotropies and the interfacial ME coupling jointly control magnetic and electric hysteresis properties.

By comparing our results with previous Monte Carlo studies of magnetoelectric heterostructures using two-state ferroelectric models [11] and with recent experimental and first-principles works on multiferroic bilayers and 2D multiferroics [25], we demonstrate that the three-state ferroelectric description preserves the main qualitative trends in more conventional models while naturally accounting for features typically associated with polarization suppression and relaxor-like behavior. This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the Hamiltonian model and the simulation method used. Results are presented and discussed in Section 3. Finally, conclusions and perspectives are given in Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

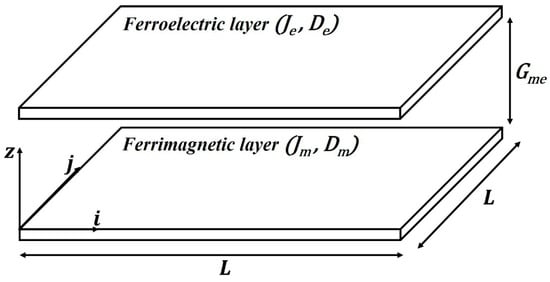

We consider a bilayer composed of a ferrimagnetic (FI) layer described by two Heisenberg mixed-spin sublattices, and , and a ferroelectric (FE) layer of the same lateral size , where each site carries a three-state dipole Periodic boundary conditions are applied in the -plane and free boundaries along the out-of-plane direction. Figure 1 displays the schematic structure of the bilayer system studied in this work.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the ferrimagnetic/ferroelectric bilayer. The system consists of a mixed-spin ferrimagnetic layer and a spin-1 ferroelectric layer, each forming an square lattice, coupled through an interfacial magnetoelectric interaction.

2.1. Hamiltonian

The total Hamiltonian which governs the system is given as:

where , and are Hamiltonians of the ferrimagnetic layer (Heisenberg spins), the ferroelectric layer (three-state pseudo-Ising model) and the interfacial magnetoelectric coupling, respectively, expressed as:

with representing the antiferromagnetic coupling between the two sublattices. denotes the Blume-Capel single-ion magnetic anisotropy along the z axis, and is the external magnetic field vector acting on spins 3/2 and 1. is the total number of spins in a layer.

is the nearest-neighbor ferroelectric coupling. represents the Blume-Capel single-ion electric anisotropy, controlling the stability of the polar states. is the external electric field.

where polar sites in the FE layer interact with the -component of the magnetic spins directly adjacent at the interface. denotes the magnetoelectric couplings between and its nearest neighbors from the ferrimagnetic layer. is assumed to take positive and negative values for interactions through and spins vectors, respectively.

2.2. Monte Carlo Simulation

We employed Monte Carlo simulation combined with the Metropolis algorithm to compute quantities of interest. For Heisenberg spins in the FI layer, a random rotation is proposed. For FE dipoles, one of the three states is proposed randomly. Moves were accepted with probability:

Here, is the energy difference between the new and old configurations, denotes the Boltzmann constant set to unity () and represents the temperature expressed in reduced (dimensionless) units. As a result, does not correspond to a direct physical temperature scale such as Kelvin or degrees Celsius.

All simulations were carried out for a layer size of . Each run consisted of a total of 180,000 Monte Carlo steps (MCs), with the first 100,000 steps discarded to ensure thermal equilibration. Statistical uncertainties were evaluated using the blocking technique in order to mitigate autocorrelation effects. The resulting error estimates were significantly smaller than the symbol sizes in all figures. Consequently, error bars are omitted from the Monte Carlo results presented throughout the paper for clarity.

Thermal averages were obtained by sweeping the temperature in small increments and using the final configuration at a given temperature as the initial state for the next one, which reduces critical slowing down near phase transitions. For hysteresis calculations, the external magnetic or electric field was varied quasistatically along a closed cycle, with sufficient Monte Carlo relaxation at each field value to approach equilibrium.

We computed the sublattice magnetizations of the ferrimagnetic layer and the total polarization of the ferroelectric layer, as well as the associated magnetic and electric susceptibilities and hysteresis loops. For clarity, we focus on the sublattice magnetizations and the total ferroelectric polarization in the results in Section 3.

- Sublattice magnetizations:

For each ferrimagnetic sublattice:

The sublattice magnetization components are given by:

Polarization of the FI layer:

Magnetic and electric susceptibilities:

Magnetic susceptibility:

Electric susceptibility:

Hysteresis loops were obtained at a fixed temperature by quasistatically cycling the external magnetic (or electric) field. From the resulting loops, we extract the coercive field and remanent magnetization and from the loops the electric coercive field and remanent polarization.

All model parameters are expressed in reduced (dimensionless) units. The ranges of magnetic and electric anisotropies and of the magnetoelectric coupling are chosen to explore physically relevant regimes, from weak to strong anisotropy and from negligible to dominant interfacial coupling. They are not intended to provide a quantitative description of specific materials but to capture generic trends in hybrid ferrimagnetic–ferroelectric bilayers.

2.3. Limitations of the Model

The present model adopts a simplified description aimed at capturing the essential mechanisms governing phase transitions and hysteresis in ferrimagnetic–ferroelectric bilayers. The ferroelectric layer is described within a discrete spin-1 framework, which accounts for the coexistence of polar and nonpolar states but does not explicitly resolve polarization gradients or finite domain-wall widths. Similarly, the magnetoelectric coupling is treated as a local interfacial interaction, focusing on short-range effects at the interface.

Within this framework, long-range electrostatic or strain-mediated interactions, explicit structural disorder, and real-time switching dynamics are not included. These effects are expected to mainly influence quantitative aspects of the response, such as the broadening of transitions, the smoothing of hysteresis loops, or moderate shifts in critical temperatures, while the qualitative mechanisms identified here remain unchanged. Finite-size effects may also lead to small shifts in the estimated critical temperatures and to a smoothing of susceptibility peaks and hysteresis loops.

The present approach should therefore be regarded as a first step toward a more comprehensive description of magnetoelectric bilayers. Extensions incorporating long-range interactions, dynamical effects, or disorder represent natural directions for future work aimed at achieving closer correspondence with experimentally realized nanoscale heterostructures.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermodynamic Behavior at Zero External Fields

In calculations, the intra-layer couplings were fixed to for the antiferromagnetically coupled ferrimagnetic sublattices and for the ferroelectric layer so that the main control parameters are the single-ion anisotropies (magnetic), (electric) and the magnetoelectric (ME) interfacial coupling , together with the external fields and (set to zero in this subsection).

In the three-state ferroelectric layer, the electric anisotropy controls the relative population of polar and nonpolar states. Large negative strongly penalizes the nonpolar configuration and favors a fully polarized ferroelectric at low temperature, whereas positive stabilizes and tends to suppress the local polarization. Analogously, the magnetic anisotropy enhances or suppresses the out-of-plane components of the Heisenberg spins, thereby modulating both ferrimagnetic order and its coupling to the ferroelectric layer. This competition between anisotropies and interfacial ME coupling is at the origin of the diverse phase behavior discussed below.

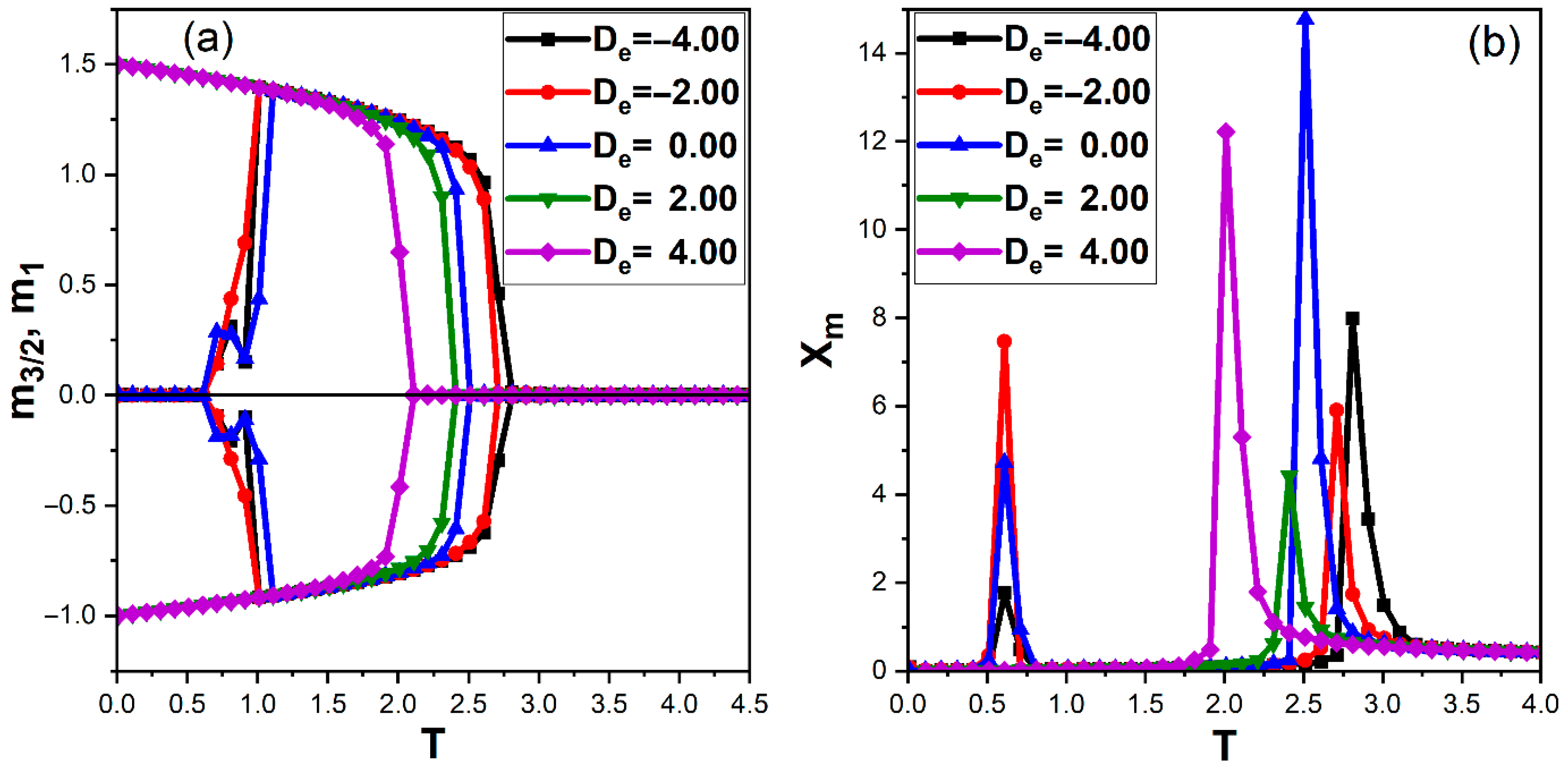

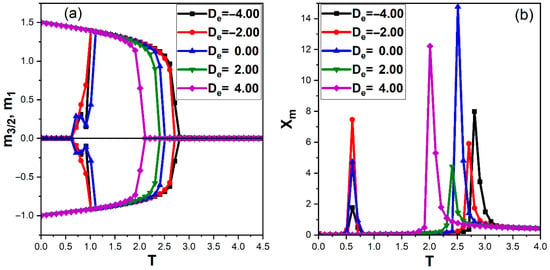

3.1.1. Effect of Electric Anisotropy on Magnetic Ordering

Figure 2 shows the temperature dependence of the sublattice magnetizations and of the ferrimagnetic layer and the corresponding magnetic susceptibilities for several values of electric anisotropy , at fixed , , , and vanishing external fields. For all , the magnitudes and decrease monotonically with temperature and vanish at a well-defined critical temperature , signaling the ferrimagnetic-paramagnetic transition (Figure 2a). The critical temperatures extracted from the peaks of the magnetic susceptibilities are and for and , respectively (Figure 2b). Thus, making more negative systematically enhances the magnetic critical temperature, whereas increasing to positive values reduces it.

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of the magnetic properties of the ferrimagnetic layer for different values of the electric anisotropy and , with , , , , and . (a) Sublattice magnetizations and as functions of temperature. (b) Corresponding magnetic susceptibilities as functions of temperature.

This behavior reflects the role of the ferroelectric layer as an effective environment for the magnetization via the ME coupling. For negative , the ferroelectric layer remains strongly polarized at low and intermediate temperatures, so that the ME interaction produces an additional effective field on the magnetic spins which stabilizes the ferrimagnetic order and shifts upward. For positive , a large fraction of sites adopts the nonpolar state ; the interfacial ME coupling is then locally switched off, and the effective magnetic field mediated by the FE layer is weakened, leading to a reduction in . This mechanism is consistent with Monte Carlo and mean-field studies of Blume-Capel-type ferroelectrics, where an increasing crystal-field term promotes nonpolar states and reduces the effective ordering field acting on coupled subsystems [26]. Similar suppression of magnetic critical temperatures induced by polarization depletion at the interface has also been reported in FI/FE heterostructures modeled with multistate ferroelectric layers [11].

The magnetic susceptibility curves in Figure 2b exhibit sharp peaks at , characteristic of a second-order transition, but also display an additional low-temperature anomaly around for and . This secondary peak, which disappears for positive , indicates a change in the internal spin configuration of the ferrimagnetic layer while the global long-range order persists. In the present three-state FE model, this anomaly can be attributed to the onset of a finite population of nonpolar FE sites when temperature is increased from very low values, which locally reduces the ME coupling and slightly rearranges the ferrimagnetic sublattices without fully destroying the order. Low-temperature susceptibility anomalies associated with partial depolarization or local decoupling have been previously observed in spin-1 Blume–Capel systems and interpreted as crossover effects within the ordered phase rather than true phase transitions [22,27].

3.1.2. Effect of Magnetic Anisotropy on Ferroelectric Ordering

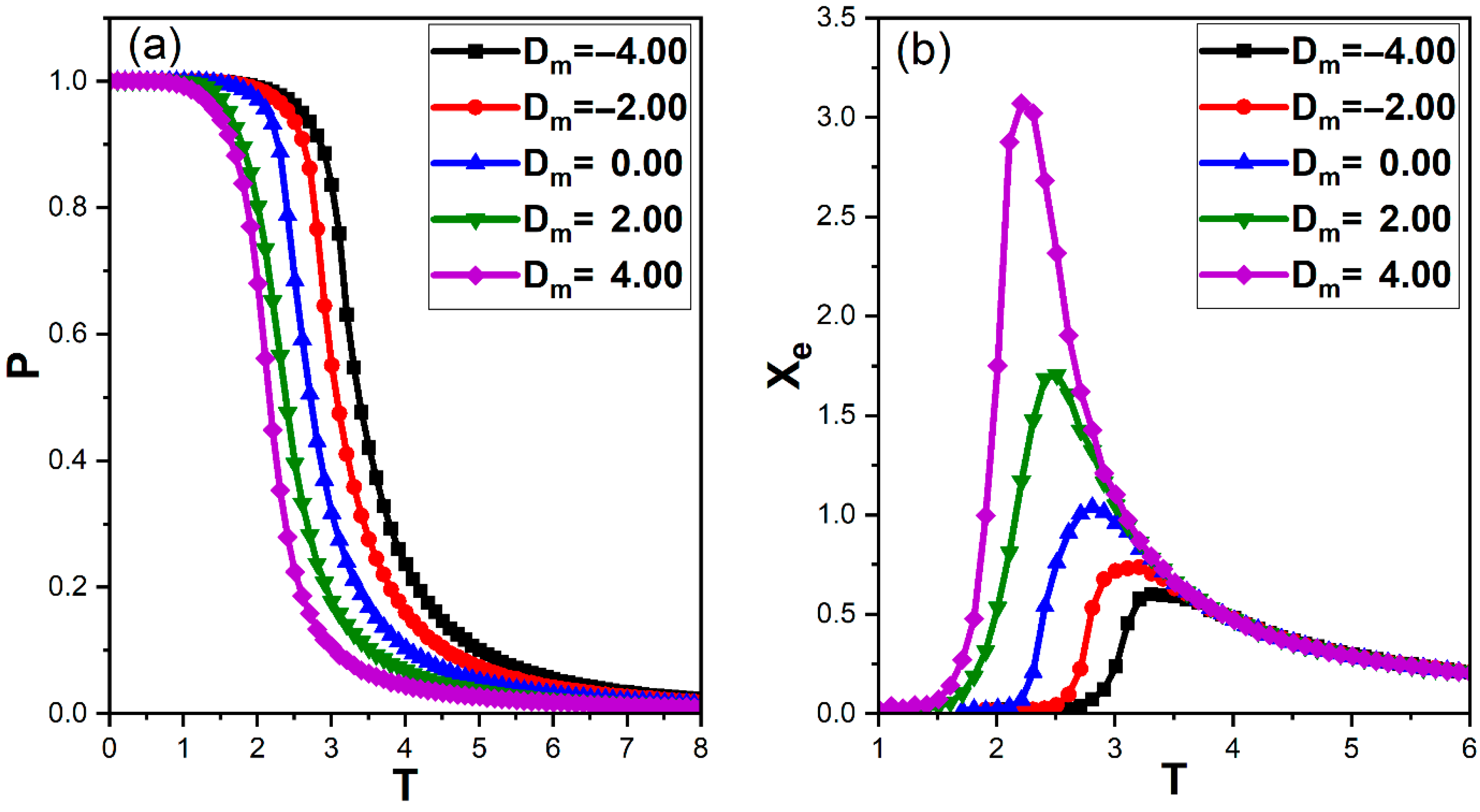

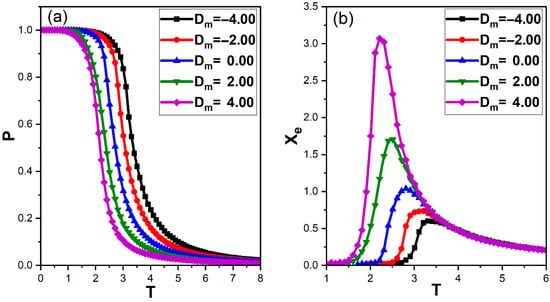

The reciprocal impact of magnetic anisotropy on the ferroelectric properties is illustrated in Figure 3, which presents the temperature dependence of the total polarization of the FE layer and its electric susceptibility for various at fixed , , and .

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence of the ferroelectric properties for different values of the magnetic anisotropy and , with , , , , and . (a) Polarization of the ferroelectric layer as a function of temperature. (b) Electric susceptibility versus temperature.

For strongly negative , the ferrimagnetic spins are tightly confined along the easy axis, maximizing their out-of-plane components and, consequently, the ME interaction at the interface. Under these conditions, the total polarization remains large up to relatively high temperatures (Figure 3a), and the electric critical temperatures extracted from the susceptibility peaks are and for and (Figure 3b). As increases towards positive values, the easy axis gradually turns into a hard axis, the out-of-plane spin components are suppressed, and the ME-induced field experienced by the FE layer is reduced. Accordingly, decreases to 2.81, 2.51 and 2.21 for and , respectively. Such reciprocal control of ferroelectric ordering by magnetic anisotropy has been widely reported in magnetoelectric bilayers, where reducing the out-of-plane spin component weakens the interfacial exchange field acting on electric dipoles [5,11].

These results demonstrate that the magnetic anisotropy can efficiently tune the ferroelectric order via interfacial coupling. First-principles and atomistic simulations of oxide-based multiferroic bilayers similarly show that enhancing magnetic anisotropy or interfacial coupling sharpens dielectric anomalies and shifts ferroelectric transition temperatures upward [28].

3.2. Role of Direct Magnetoelectric Coupling

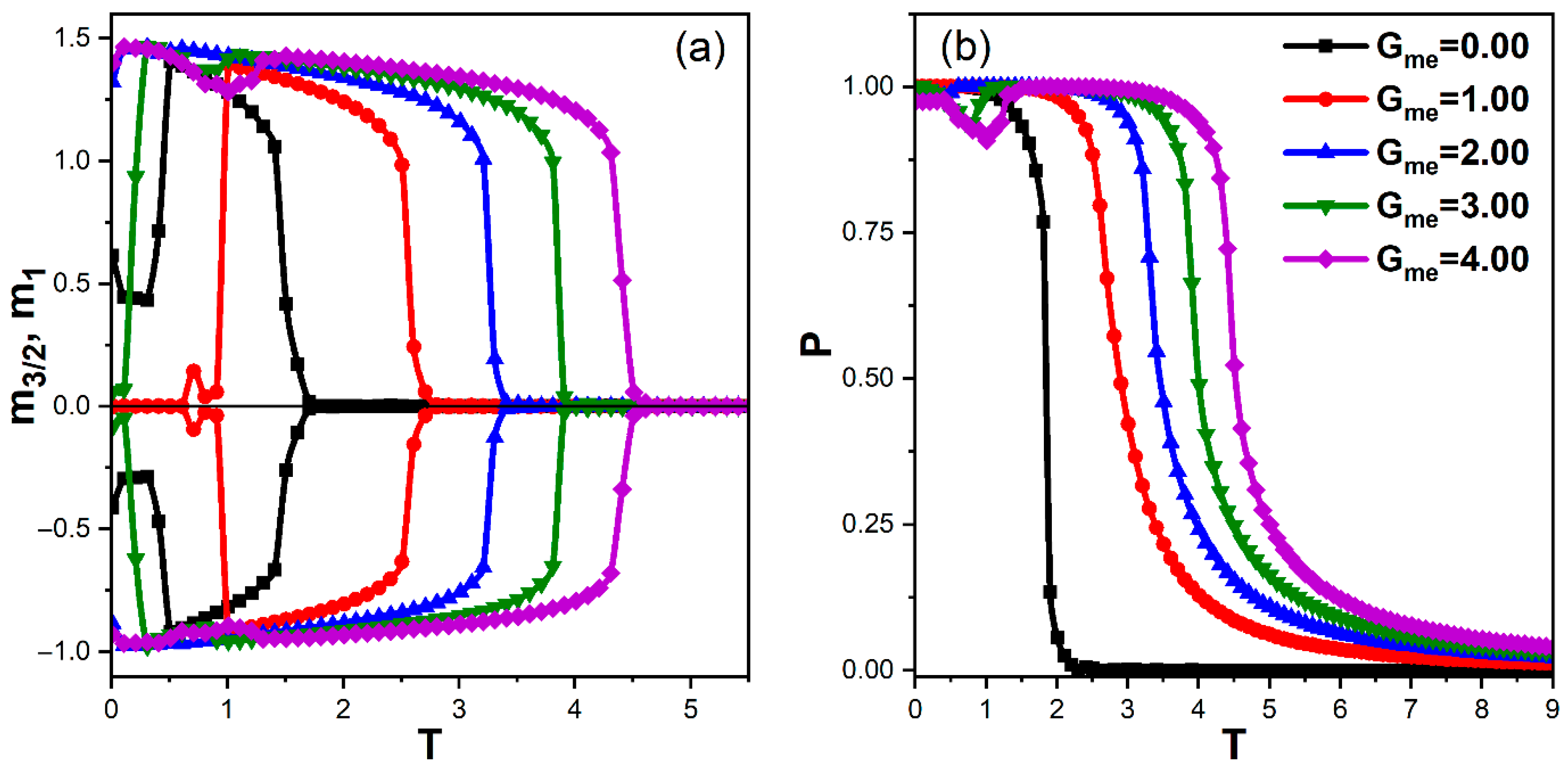

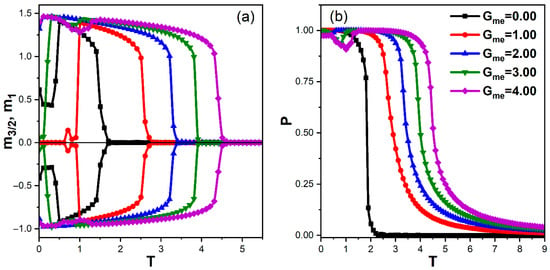

To disentangle the role of the direct ME exchange at the interface from that of the single-ion anisotropies, we now vary while keeping . The temperature dependence of the ferrimagnetic sublattice magnetizations and the FE polarization for is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Temperature dependence of the magnetic and ferroelectric order parameters for different magnetoelectric coupling strengths and , with , , , , and . (a) Sublattice magnetizations and as functions of temperature. (b) Total polarization as a function of temperature.

In the absence of interfacial coupling (), the magnetic and ferroelectric layers are essentially decoupled, and their critical temperatures are significantly lower than in the coupled case: and . The two transitions are well separated and governed by the intrinsic intra-layer couplings and . As soon as a finite ME coupling is introduced, both critical temperatures increase monotonically with , reaching and for . The simultaneous enhancement and eventual near-coincidence of the two transition temperatures indicate that the FI and FE layers become strongly locked by the ME interaction, undergoing a joint order-disorder transition for sufficiently large . The locking of magnetic and ferroelectric transitions induced by strong interfacial coupling has been identified as a hallmark of exchange-driven magnetoelectric systems, both in Monte Carlo simulations and in effective Hamiltonian approaches [11,29].

For intermediate coupling (), an additional low-temperature anomaly appears at , reflecting the same partial rearrangement of spin–dipole configurations discussed in Section 3.1.1. In contrast to two-state ferroelectric models, the present three-state description naturally accounts for these additional anomalies through the temperature-dependent activation of nonpolar states, without invoking extrinsic disorder or defects [19,20,21].

From an applications standpoint, the strong enhancement of both and with implies that engineering interfaces with large ME coupling via, for instance, chemical substitution, strain, or low-dimensional design, is a promising route to achieve room-temperature multiferroic functionality. Recent high-throughput first-principles screenings of two-dimensional multiferroics further support this trend, predicting robust magnetoelectric coupling and enhanced ordering temperatures in interfacially engineered systems [28].

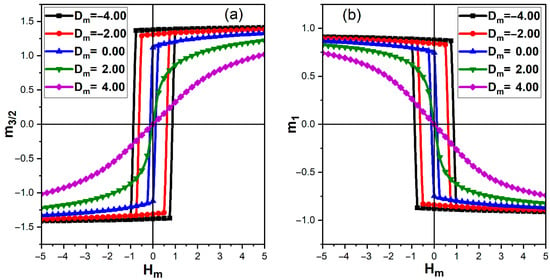

3.3. Magnetic Hysteresis and Anisotropy Tuning

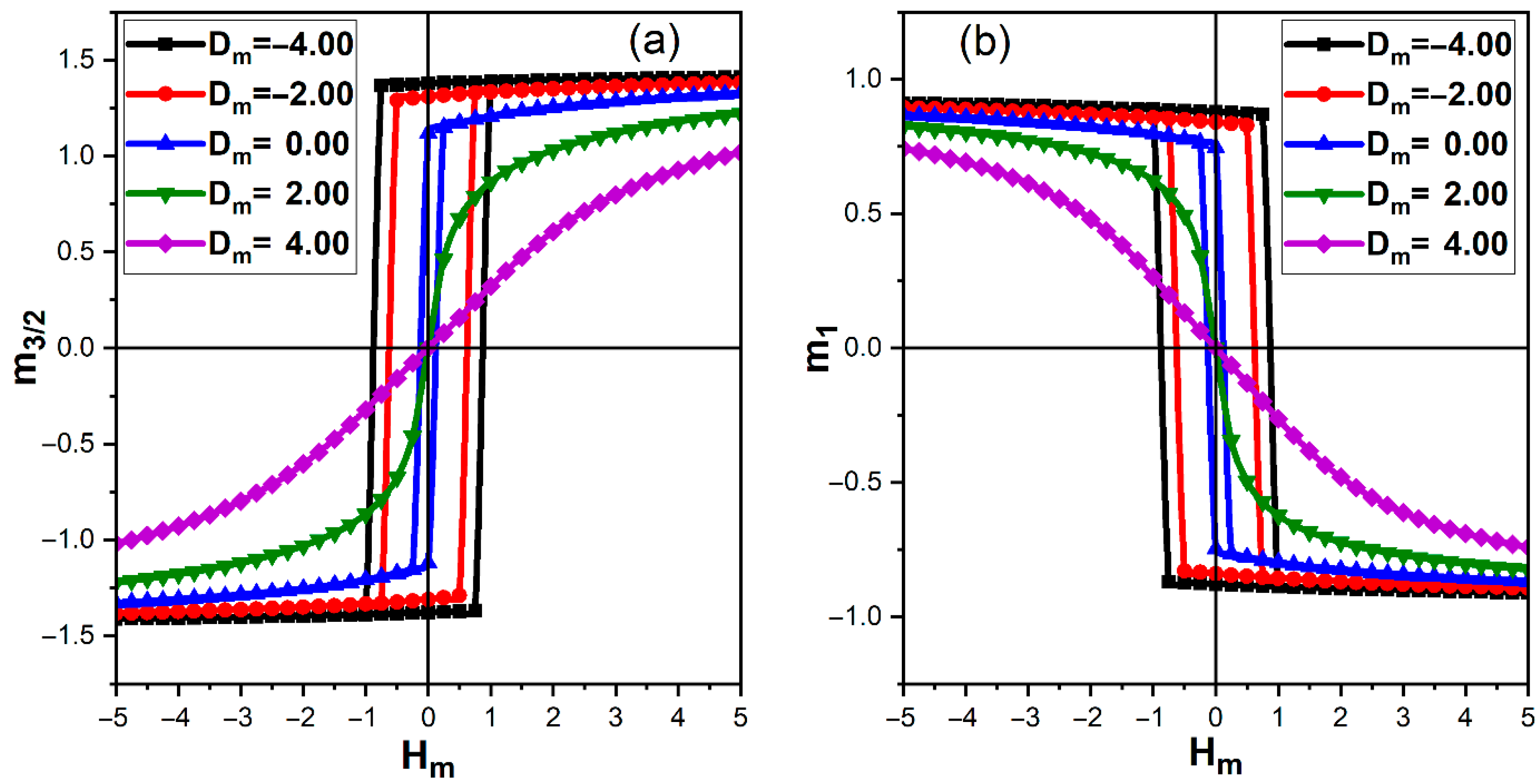

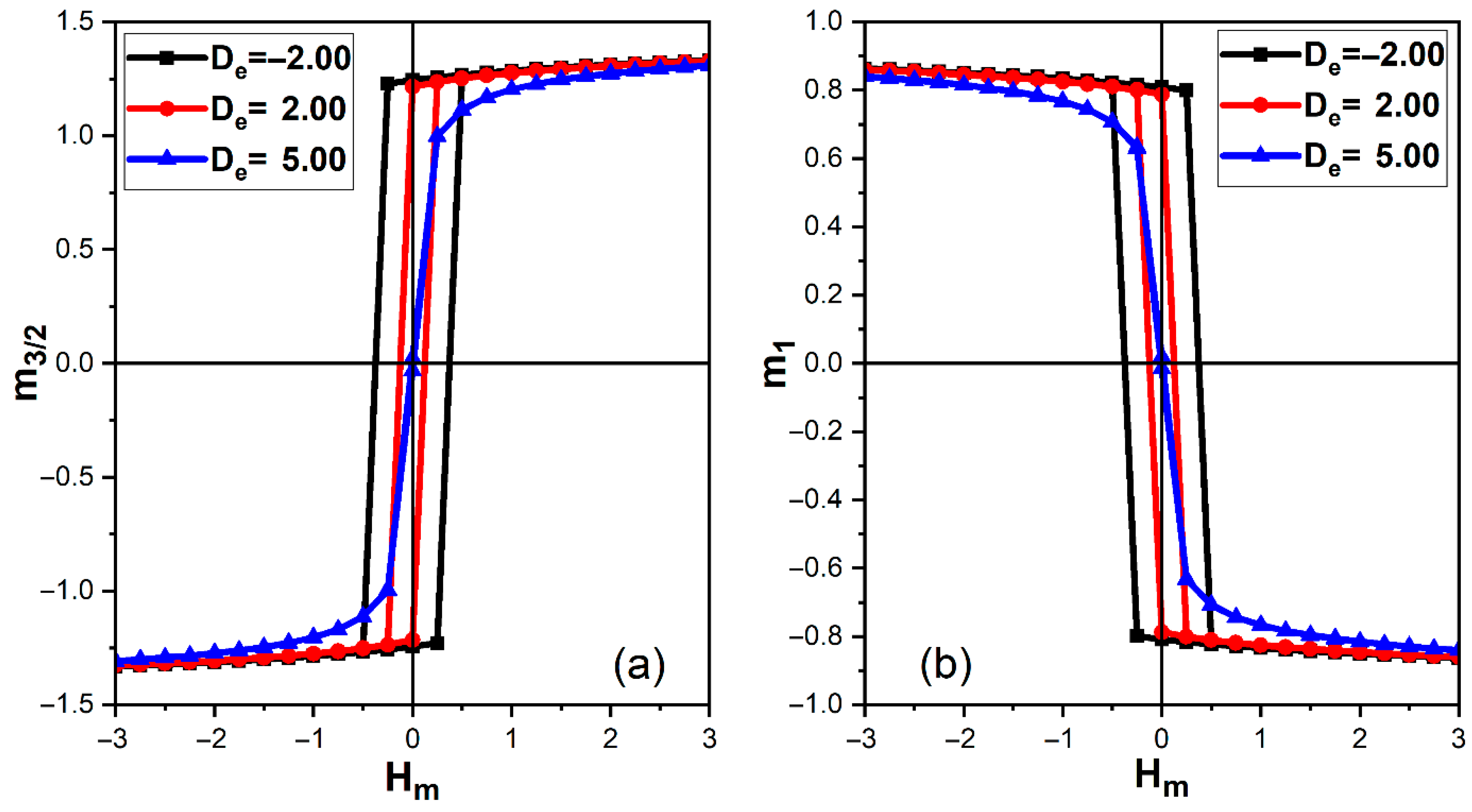

We now turn to the quasistatic magnetic hysteresis loops of the ferrimagnetic layer at fixed temperature , focusing on the dependence of the coercive field and remanent magnetization on the single-ion anisotropies of both layers.

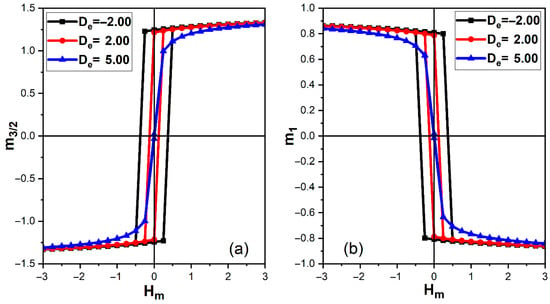

Figure 5 shows the hysteresis loops of the partial magnetizations and as functions of the external magnetic field for different magnetic anisotropies , at fixed , , and zero electric field. For the spin- sublattice, the coercive field and remanence are , , and for and , respectively (Figure 5a). For the spin-1 sublattice (Figure 5b), the corresponding values are , , and . As is further increased to positive values ( and ), both coercivity and remanence vanish and the loops collapse, indicating a transition to a magnetically soft or nearly paramagnetic state at this temperature.

Figure 5.

Magnetic hysteresis loops of the partial magnetizations of the ferrimagnetic layer at temperature for different magnetic anisotropies and , with , , , . (a) Hysteresis of the sublattice magnetization (spin-3/2). (b) Hysteresis of the sublattice magnetization (spin-1).

The progressive reduction in the coercive field and remanent magnetization with increasing reflects the lowering of anisotropy-induced energy barriers separating metastable magnetic states, a behavior commonly observed in easy-axis to easy-plane crossover regimes of mixed-spin and multilayer ferrimagnets [27,28].

The comparison between and loops also highlights the ferrimagnetic nature of the bilayer: while both sublattices exhibit similar coercive fields for a given , the remanent magnetization of the spin- sublattice is systematically larger, reflecting its higher spin magnitude and the antialigned configuration imposed by . Such nearly reversible hysteresis loops are characteristic of magnetically soft systems and have been reported in Monte Carlo studies of ferrimagnetic multilayers when anisotropy becomes insufficient to stabilize stable domain configurations at finite temperature [27].

Figure 6 emphasizes the influence of the electric anisotropy on magnetic hysteresis. Here is fixed, while is varied between and at . For the spin- sublattice (Figure 6a), () evolves from at to at , and finally to an almost reversible loop with a vanishing coercive field and remanence at . The spin-1 sublattice follows the same trend with slightly smaller remanence. The modest reduction in coercivity between and reflects a gradual weakening of the ME-induced pinning field as more nonpolar states are allowed, while the abrupt collapse of the loop at indicates that the ferroelectric layer is essentially nonpolar so that the magnetic subsystem behaves nearly as an isolated ferrimagnet with reduced anisotropy and weak effective pinning.

Figure 6.

Magnetic hysteresis loops of the partial magnetizations of the ferrimagnetic layer at temperature , for different electric anisotropies and , with , , , and . (a) Hysteresis of the sublattice magnetization . (b) Hysteresis of the sublattice magnetization .

Differences in remanent magnetization between inequivalent sublattices are a generic feature of ferrimagnetic systems and can give rise to compensation effects and asymmetric hysteresis when sublattice parameters or anisotropies are further tuned [27]. From a magnetoelectric perspective, the sensitivity of magnetic coercivity to both magnetic and electric anisotropies highlights the indirect control of magnetic switching through polarization-mediated interfacial pinning fields [5,11].

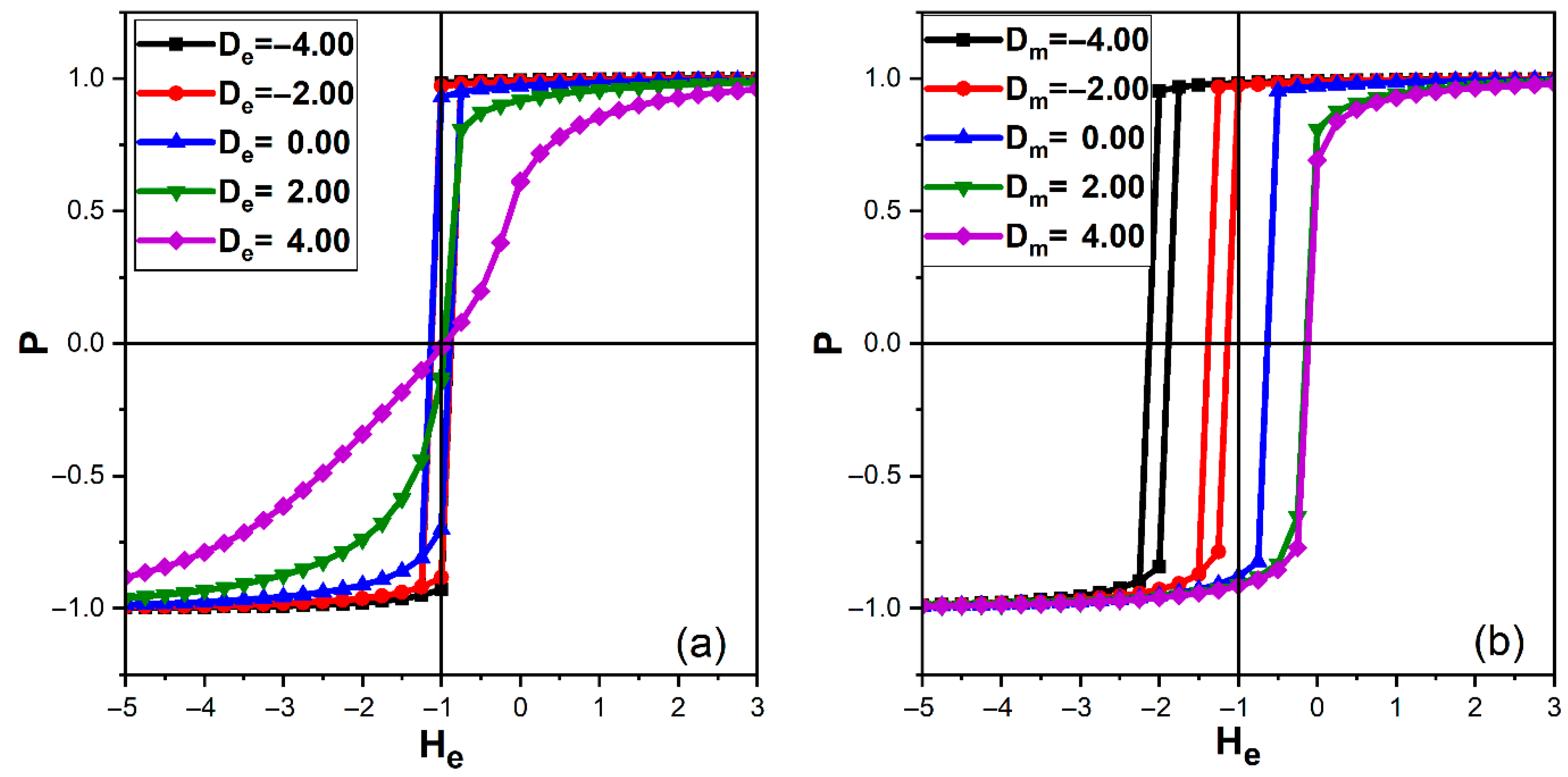

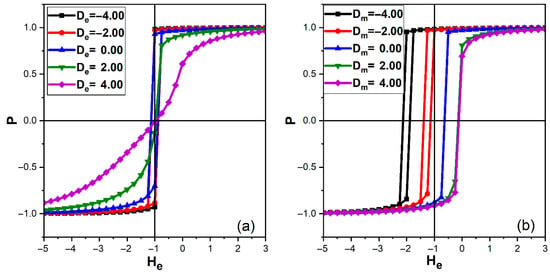

3.4. Electric Hysteresis and Cross-Control of Polarization

The electric hysteresis behavior of the ferroelectric layer is depicted in Figure 7, which shows the polarization-electric field (-) loops at under different anisotropy conditions. In Figure 7a, the magnetic anisotropy is fixed to , while the electric anisotropy is varied from to . For and , the loops are wide and nearly rectangular, with coercive fields and remanent polarizations . At , the loop remains well defined but slightly slimmer, and the remanent polarization decreases to , while remains almost unchanged. For positive , both coercivity and remanence disappear, indicating that the system responds almost linearly to the electric field with negligible remnant polarization once the field is removed.

Figure 7.

Electric hysteresis loops of the polarization of the ferroelectric layer at temperature with , . (a) Polarization-field loops for different electric anisotropies , at fixed magnetic anisotropy . (b) Polarization-field loops for different magnetic anisotropies , at fixed electric anisotropy .

The transition from square to slim polarization loops with increasing is a direct manifestation of the growing accessibility of the nonpolar state, which smooths polarization reversal and reduces remanent polarization, as widely reported in spin-1 Blume–Capel ferroelectric models [19,20,21,30].

For large positive , the nonpolar state dominates, the polarization is easily suppressed, and the hysteresis loop nearly vanishes. Comparable loop slimming and polarization suppression have also been observed experimentally in relaxor ferroelectrics and ultrathin ferroelectric films, where local nonpolar regions emerge under thermal or field-driven fluctuations [15,16,17,18].

Figure 7b illustrates the reciprocal effect of magnetic anisotropy on the electric hysteresis at fixed . For and , the polarization loops remain wide and almost symmetric, with remanent values –0.97 and coercive fields close to 0.14. When is increased to 0.00 and beyond, the loops collapse, and both the coercive field and remanence tend to zero.

Because the FE layer is coupled to the out-of-plane component of the ferrimagnetic spins, a strong magnetic anisotropy maintains a large interfacial ME field throughout the switching cycle, thereby supporting robust polarization reversal. In contrast, for , the spins tilt away from the -axis, the ME field weakens and becomes poorly correlated with the applied electric field, and the FE layer behaves almost as a decoupled spin-1 ferroelectric. At , it then lies close to its critical region and no longer shows a pronounced hysteresis loop. This behavior confirms that magnetic anisotropy acts as an effective control parameter for electric hysteresis by regulating the magnitude and stability of the interfacial magnetoelectric field experienced by the ferroelectric layer [11].

Similar cross-control of polarization by magnetic degrees of freedom has been reported in oxide superlattices and engineered multiferroic heterostructures, where interfacial anisotropy engineering enables large magnetoelectric responses and tunable hysteresis characteristics [31,32].

Although the hysteresis loops are expressed in reduced units, their qualitative evolution can be directly compared with experimentally measured magnetization and polarization loops in thin-film ferrimagnetic–ferroelectric heterostructures. In particular, the transition from square to slim or nearly reversible loops reflects the progressive reduction in anisotropy and interfacial pinning, as commonly observed in ultrathin films or when approaching critical regimes. The trends observed here therefore mirror experimental hysteresis behaviors at a qualitative level, without aiming at a quantitative description of specific materials.

4. Conclusions

We used Monte Carlo simulations to investigate a ferrimagnetic/ferroelectric bilayer in which a mixed-spin Heisenberg ferrimagnet is coupled to a three-state ferroelectric layer through a direct interfacial magnetoelectric interaction. The spin-1 description of the ferroelectric layer, controlled by an electric single-ion anisotropy, allows for a nonpolar state and thus goes beyond conventional two-state ferroelectric models.

Our results show that the magnetic and electric single-ion anisotropies strongly and reciprocally influence the ferrimagnetic and ferroelectric transition temperatures, while the magnetoelectric coupling can significantly enhance both critical temperatures and, for sufficiently strong coupling, lock the two order parameters into a common transition. At fixed temperature, we find that both magnetic and electric hysteresis loops can be widely tuned: coercive fields and remanent order parameters decrease and the loops evolve from square to slim or nearly reversible shapes as the anisotropies are varied.

These findings demonstrate that incorporating three-state ferroelectricity into magnetoelectric bilayer models provides a simple framework to capture polarization suppression and tunable hysteresis while retaining the essential physics of magnetoelectric coupling. The model thus offers a useful starting point for interpreting and guiding experiments on hybrid FI/FE heterostructures where interface engineering and anisotropy control are key design parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.N.; methodology, G.D.N. and A.K.; validation, A.K. and M.K.; formal analysis, G.D.N. and M.K.; investigation, G.D.N. and M.K.; data curation, G.D.N. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D.N. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, G.D.N., M.K. and A.K.; visualization, M.K.; project administration, G.D.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FE | Ferroelectric |

| FI | Ferrimagnetic |

| ME | Magnetoelectric |

References

- Spaldin, N.A.; Fiebig, M. The Renaissance of Magnetoelectric Multiferroics. Science 2005, 309, 391–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, R.; Spaldin, N.A. Multiferroics: Progress and prospects in thin films. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Nan, C.W. Recent progress in multiferroic magnetoelectric composites: From bulk to thin films? Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 1062–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, J.T.; Bosse, J.L.; He, Q.; Gao, Y.; Trassin, M.; Ye, L.; Clarkson, J.D.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Salahuddin, S.; et al. Deterministic switching of ferromagnetism at room temperature using an electric field. Nature 2014, 516, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, C.A.F.; Hoffman, J.; Ahn, C.H.; Ramesh, R. Magnetoelectric coupling effects in multiferroic complex oxide composite structures. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2900–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibes, M.; Barthélémy, A. Towards a magnetoelectric memory. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manipatruni, S.; Nikonov, D.E.; Young, I.A. Beyond CMOS computing with spin and polarization. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, T.; Liu, Q.; Dong, J.; Lin, T.; Zhang, Q.; Lan, X.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Pei, J.; et al. Electric field control of the perpendicular magnetization switching in ferroelectric/ferrimagnet heterostructures. Newton 2025, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Jia, L.; Shi, S.; Zhao, T.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, J. Ferroelectric Control of Spin-Orbitronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2406444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Yang, M.; Ju, H.; Wang, S.; Ji, Y.; Li, B.; Edmonds, K.W.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, N.; et al. Electric field control of deterministic current-induced magnetization switching in a hybrid ferromagnetic/ferroelectric structure. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafullin, I.F.; Kharrasov, M.K.; Diep, H.T. Magneto-ferroelectric interaction in superlattices: Monte Carlo study of phase transitions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 476, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotorlishvili, L.; Etesami, S.R.; Berakdar, J.; Khomeriki, R.; Ren, J. Electromagnetically controlled multiferroic thermal diode. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 134424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomeriki, R.; Chortorlishvili, L.; Tralle, I.; Berakdar, J. Positive–Negative Birefringence in Multiferroic Layered Metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 7290–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.S.; Liu, J.-M.; Chen, X.Y.; Liu, Z.G. Monte Carlo approach to phase transitions in ferroelectromagnets. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88, 4250–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokov, A.A.; Ye, Z.G. Recent progress in relaxor ferroelectrics with perovskite structure. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Taniguchi, H.; Itoh, M.; Koshihara, S.-Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Mori, S. Relaxor Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3: A Ferroelectric with Multiple Inhomogeneities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 207601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Wen, J.; Stock, C.; Gehring, P.M. Phase instability induced by polar nanoregions in a relaxor ferroelectric system. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleemann, W. Random fields in relaxor ferroelectrics. J. Adv. Dielectr. 2012, 2, 1241001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, M. Theory of the first-order magnetic phase change in UO2. Phys. Rev. 1966, 141, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, H.W. On the possibility of first-order phase transitions in Ising systems of triplet ions with zero-field splitting. Physica 1966, 32, 966–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, A.F.; Fittipaldi, I.P. On the phase transitions in Blume–Capel model. Phys. Status Solidi 1983, 119, K31–K36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez-Zharaouy, H.; Kassou-Ou-Ali, A. Phase diagrams of spin-1 Blume–Capel film with an alternating crystal field. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 064415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoston, W.; Berker, A.N. Multicritical behavior of the Blume–Emery-Griffiths model with repulsive biquadratic coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngantso, G.D.; Boungou, C.; Karimou, M.; Zaari, H.; Malonda-Boungou, B.; M’PAssi-Mabiala, B. Coupled magnetic and ferroelectric responses in a hybrid trilayer structure: A Monte Carlo approach with Heisenberg and Ising models. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2025, 634, 173558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channagoudra, G.; Dayal, V. Magnetoelectric coupling in ferromagnetic/ferroelectric heterostructures: A survey and perspective. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 928, 167181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Tamerd, M.; Marjaoui, A.; Zanouni, M.; El Marssi, M.; Jouiad, M.; Lahmar, A. Investigation of the magnetoelectric properties of Bi0.9La0.1Fe0.9Mn0.1O3/La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 bilayer: Monte Carlo simulation. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2023, 667, 415192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensif, O.; Hasnaoui, A.; Zouhair, S.; Hachem, N.; Madani, M.; El Bouziani, M. Magnetic properties and hysteresis loops of mixed spin-1/2 and spin-3/2 Blume-Capel model on a multilayer square lattice. Rom. J. Phys. 2024, 69, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X. Realization of 2D multiferroic with strong magnetoelectric coupling by intercalation: A first-principles high-throughput prediction. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafullin, I.F.; Yuldasheva, A.R.; Abdrakhmanov, D.I.; Kizirgulov, I.R.; Diep, H.T. Phase transitions driven by magnetoelectric and interfacial Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 587, 171317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, Y. Enhanced Magnetoelectric Coupling in Two-Dimensional Hybrid Multiferroic Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 165408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fei, R.; Lu, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, L. Artificial Multiferroics and Enhanced Magnetoelectric Effect in van der Waals Heterostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 25468–25479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, C.; Wen, Y.; Liang, S.; Yin, L.; Cheng, R.; Wang, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, L.; He, J. Ferroelectricity-Driven Strain-Mediated Magnetoelectric Coupling in Two-Dimensional van der Waals Heterostructures with Ultra-Low Power Operation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.