Abstract

This work presents a micromagnetic investigation of monolayer L10 FePt and FePt/Fe bilayer thin films to clarify the role of thickness, composition, and exchange coupling in their magnetic behavior. Simulations were performed using the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert formalism implemented in OOMMF, with realistic material parameters and geometries. For FePt monolayers, film thicknesses of 1–20 nm were examined, revealing a non-monotonic coercivity trend: the coercive field increased from 35 mT at 1 nm to 136 mT at 10 nm and decreased to 69 mT at 20 nm. This evolution indicates a transition from localized reversal to domain-wall-mediated switching once the film exceeds the exchange length (10–20 nm). Additional simulations varying Fe concentration (48–68%) through the exchange stiffness constant showed that higher Fe content strengthens magnetic coupling and increases coercivity. Bilayer systems combining a 2 nm FePt layer with Fe layers of 10 and 12 nm exhibited rectangular, saturated loops, confirming strong exchange coupling and exchange-spring behavior. The results identify 2 nm FePt as the optimal thickness for achieving full saturation, balanced coercivity, and thermal stability in FePt/Fe thin-film architectures.

1. Introduction

Magnetic nanostructures and thin films with tailored magnetic properties are central to the development of next-generation spintronic devices, high-density magnetic recording media, and permanent magnets [1,2,3]. Among these materials, chemically ordered L10 FePt alloys have attracted considerable attention due to their exceptionally high magnetocrystalline anisotropy (≈7 × 106 J/m3), thermal stability, and large coercivity [4,5]. These characteristics make FePt an excellent candidate for hard magnetic layers in composite systems, particularly in exchange-coupled bilayers and multilayer heterostructures [6,7,8].

The concept of the exchange-spring magnet, originally proposed to combine the high coercivity of a hard phase with the high magnetization of a soft phase, provides a pathway to achieving superior magnetic performance [9,10,11]. In such systems, the interfacial exchange interaction allows the magnetization to gradually rotate from the hard to the soft layer under an external magnetic field, mimicking the elastic behavior of a mechanical spring [12]. The degree of coupling, and hence the magnetization reversal mechanism, strongly depends on the relative thickness and anisotropy of the two magnetic components [13,14]. A balance between interfacial exchange strength and individual layer thickness is therefore essential for optimizing both coercivity and saturation magnetization.

FePt-based hard/soft magnetic heterostructures continue to attract considerable attention due to their strong potential for high-density recording and advanced permanent-magnet technologies. L10-ordered FePt provides extremely high magnetocrystalline anisotropy, thermal stability, and compatibility with heat-assisted magnetic recording (HAMR) media [15,16], whereas Fe and Fe-rich alloys offer high and low switching fields, enabling efficient exchange-spring coupling when integrated into composite architectures [17,18]. Previous theoretical and experimental studies have explored FePt thickness effects, interface exchange, and composition-dependent magnetic properties in both monolayer and bilayer geometries, highlighting the critical role of exchange length, domain-wall formation, and anisotropy orientation in determining reversal behavior [19,20,21]. Despite extensive interest, a systematic micromagnetic analysis connecting FePt thickness, Fe composition, exchange parameters, and the transition from rigid to spring-like reversal remains limited. While many experimental and theoretical studies have explored FePt-based bilayers [22,23,24], the specific influence of FePt layer thickness at the monolayer and ultrathin limit on magnetic hysteresis and saturation behavior remains less understood. Previous work has indicated that excessive FePt thickness leads to rigid magnetic coupling, preventing full magnetization reversal at moderate fields [25], whereas too thin a hard layer can result in thermal instability and reduced anisotropy [26]. Thus, identifying an optimal FePt thickness that enables exchange-spring behavior under practical magnetic field strengths is crucial for both fundamental understanding and technological application.

In this study, we performed micromagnetic simulations to systematically investigate the effect of FePt thickness on the magnetic hysteresis of monolayer FePt and bilayer FePt/Fe systems under an applied field of 500 mT. FePt layers of 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 nm were modeled to assess their coercivity and saturation response. The 2 nm FePt film was identified as the most favorable configuration, reaching full saturation while maintaining moderate coercivity. When combined with Fe layers of 10 and 12 nm, the resulting FePt/Fe bilayers achieved complete magnetization reversal, demonstrating a clear transition from a rigidly coupled system to an exchange-spring configuration as FePt thickness decreased. From a thermodynamic viewpoint, 1 nm FePt films exhibit instability, reinforcing the 2 nm thickness as the optimum for achieving stable and efficient exchange-spring magnet behavior. To further extend this analysis, additional simulations were carried out for a 20 nm L10 FePt monolayer and for alloys with varying Fe concentrations, indirectly tuned through the exchange stiffness constant. The 20 nm FePt film exhibited a smoother hysteresis loop and a lower coercive field compared to the 5 and 10 nm cases, consistent with magnetization reversal occurring over distances comparable to or exceeding the exchange length (10–20 nm for Fe-based systems). This behavior confirms the transition from localized, nucleation-dominated reversal in thinner layers to domain-wall-mediated switching in thicker ones. Moreover, increasing Fe concentration from 48% to 68% enhanced exchange coupling and slightly increased coercivity, with the lowest Fe content yielding full saturation in the loop. These findings provide additional insight into the interplay between exchange stiffness, layer thickness, and composition in determining the reversal mechanisms and stability of FePt-based magnetic thin films. Thus, this work addresses this gap by providing a detailed thickness- and composition-dependent study of monolayer FePt and FePt/Fe bilayers under realistic device-level magnetic fields.

2. Materials and Methods

Micromagnetic simulations were performed by numerically solving the standard Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) equation [27] to model the dynamic evolution of magnetization under an applied magnetic field. The simulations were implemented using the Object-Oriented MicroMagnetic Framework (OOMMF), which provides a finite-difference solution of the LLG equation over a discretized magnetic structure [28]. Under the assumption of micromagnetic theory, Brown [29] derived a set of equations after employing the magnetic Gibbs free energy via Equation (1), such as

This integral in Equation (1) runs over the total volume of the ferromagnetic body. The details of constituent energies are as follows: Exchange energy indicates the interaction of spins with nearest neighbors. Volume anisotropy energy indicates the crystal structure and depends on the crystal type of specimen material, i.e., uniaxial or cubic symmetry. The Zeeman energy indicates an externally applied magnetic field . The term indicates the demagnetizing field, also called the stray field, and triggers a demagnetizing energy contribution. In the case of a nanomagnetic thin films, which consist of N layers, the involved energies are given by Equations (2)–(5):

where is the exchange-stiffness constant, the magnetization vector, and is the demagnetizing field of the i-th layer. Thus, macroscopically, Mi is the total magnetization of individual layers.

Equation (1) generates an effective magnetic field Heff which accounts for all relevant contributions to the magnetic Gibbs free energy E, such as the externally applied magnetic field H, the demagnetizing field , and the exchange field. When a ferromagnetic material is placed in a magnetic field, its magnetization vector Mi “moves” due to the influence of Heff. This motion is well described by the Landau–Lifshitz theorem [29], which is expressed by Equation (6):

This equation describes the precession of magnetization vector Mi in an effective field Heff. On the other hand, hysteresis curves tell us that beyond a certain value of an applied magnetic field, any magnetic sample can become saturated, i.e., all moments in the material are aligned along the field direction, and thus, precession alone cannot describe this process. Energy dissipation (or damping) must be included to allow for magnetization to relax toward the saturated state. This is the reason why Gilbert [30] included a phenomenological damping parameter in Equation (6) to express the experimentally noticeable damping in ferromagnetic materials. Consequently, the equation of Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) is given by

where is the damping parameter, and is the gyromagnetic ratio. The resulting dynamics from Equation (7) is a damped processional motion of the magnetization vector , of each magnetic nanolayer of the thin film, around the effective field.

The computational model consisted of a single L10 FePt layer (monolayer case) and a bilayer configuration composed of FePt and Fe films. In the bilayer structure, two atlas boxes were defined in OOMMF: using the OOMMF command “top”, we defined the position of the FePt hard layer. We also set the position of the Fe soft layer by using the OOMMF command “bottom”. The interfacial region was explicitly defined to include the exchange interaction between the two materials, ensuring continuous magnetization coupling across the interface. In the bilayer FePt/Fe simulations, the interlayer exchange coupling was modeled using the standard continuous-exchange formalism implemented in OOMMF. The FePt (top) and Fe (bottom) layers were defined as adjacent regions, and inter-region exchange was activated so that spins at the interface experience an exchange energy density governed by the exchange stiffness of the contacting layers. This approach corresponds to the conventional micromagnetic treatment of exchange-spring structures, where the interface is assumed to maintain magnetic continuity across atomic planes. The method is well established and has been applied extensively in FePt-based exchange-coupled composite media [10,11].

The system was discretized using a fine rectangular mesh, which provided a good balance between numerical accuracy and computational efficiency. The monolayer FePt films were discretized using an in-plane cell size of 5 × 5 nm2. Because the thinnest film studied was 1 nm, the cell size along the out-of-plane direction was set equal to the total film thickness t (t = 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 nm), resulting in a single computational cell along z, as is standard for ultrathin micromagnetic layers. For both bilayer and monolayer films, the length and width dimensions were set equal to 150 × 150 nm2, respectively, corresponding to a grid of 30 × 30 × t cells. To replicate extended films and avoid edge-driven reversal, periodic boundary conditions were applied in the in-plane (x and y) directions, with free boundaries along the z axis. The external in-plane magnetic field was applied along the x direction with the command (xyz) → (100), which nulls the y and z components of the magnetic field H, while the hysteresis loops were obtained by gradually sweeping the field from positive to negative saturation up to 500 mT. The simulated sample structures are illustrated in Scheme 1 together with the reference frame used.

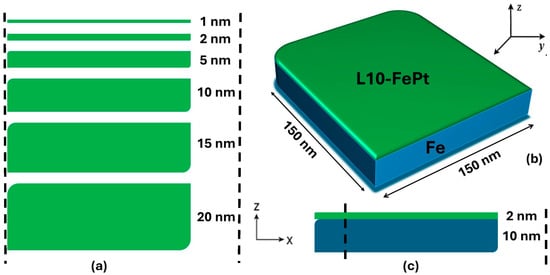

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the simulated thin-film structures: (a) Cross-section image of the various monolayer L10- FePt ultrathin films with in-plane dimensions of 150 × 150 nm2 and thickness varied between 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 nm. (b) Bilayer structure consisting of an L10-FePt layer and an Fe layer, both with the same in-plane dimensions of 150 × 150 nm2. In the bilayer, the L10-FePt layer is five times thinner than the Fe layer, corresponding to the simulated case L10-FePt 2 nm / Fe 10 nm. The structure L10-FePt 2 nm / Fe 12 nm was also studied. (c) Cross-section sequence of the simulated bilayer structure L10-FePt 2 nm / Fe 10 nm. A reference coordinate frame is included to indicate the x–y plane and film-normal z-direction.

The material parameters were selected from typical experimental and theoretical values reported for bulk and thin-film Fe and L10 FePt systems [31,32]. The saturation magnetization was set to MFe = 1.2 × 106 A/m and MFePt = 0.5 × 106 A/m while exchange stiffness constants were assigned as AFePt = 1.2 × 10−11 J/m, AFe = 2.8 × 10−11 J/m and Aex = 1.8 × 10−11 J/m. The latter constant is referred to as the interface exchange-coupled constant. Two anisotropy contributions were considered in micromagnetic simulations. The first is the intrinsic uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy, which for the L10-FePt layer was defined with its easy axis fixed along the out-of-plane (z) direction, consistent with the exhibition of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy [11]. In addition, a secondary uniaxial anisotropy contribution with randomly oriented easy axis was introduced to phenomenologically account for microstructural effects such as surface roughness, local strain variations, interface disorder, and nanoscale inhomogeneities that are not explicitly resolved within the discretized micromagnetic mesh. This approach is consistent with our recent combined experimental and micromagnetic investigation [33], in which the inclusion of a secondary uniaxial anisotropy term was necessary to reproduce the experimentally observed hysteresis characteristics, thereby validating the adopted modeling strategy to represent non-idealities arising from growth-induced disorder. The demagnetization (shape anisotropy) contribution was fully accounted for by the magnetostatic field calculated self-consistently within the micromagnetic framework and was not introduced as an additional anisotropy term. The total effective anisotropy governing the magnetization dynamics therefore results from the combined action of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy, the additional uniaxial disorder-related contribution, and the demagnetization field.

For the effective magnetic anisotropy values Keff, the following literature values were used: Keff_Fe = 4.8 × 104 J/m3 for Fe and Keff_FePt = 0.6 × 106 J/m3 for L10-FePt [11,34,35]. The Fe layer, being magnetically soft with very low intrinsic cubic anisotropy, was assumed to be in-plane isotropic, with its magnetization free to align along the applied field or follow exchange coupling with the L10-FePt layer. Hysteresis loops were simulated for both in-plane and out-of-plane applied field orientations to capture the directional dependence of magnetization reversal.

The hysteresis behavior was calculated by applying an external magnetic field from +500 mT to −500 mT, using quasi-static relaxation at each field step to ensure equilibrium magnetization states. The magnetic field step was set equal to 0.5 mT/s. Magnetization reversal processes were analyzed by recording the average magnetization, coercivity, and saturation field for each FePt thickness (1, 2, 5, and 10 nm) and for FePt/Fe bilayers with Fe layers of 10 and 12 nm. Thermal fluctuations were also incorporated into the simulations to account for finite-temperature effects. This was achieved by introducing a stochastic thermal field term (random noise field) in accordance with the fluctuation–dissipation theorem, ensuring a realistic representation of thermal agitation during magnetization dynamics [36]. The magnitude of the noise field is assumed to be the same in all three directions (isotropic), with a zero mean. Mathematically, these assumptions can be written as follows [37]: , and . A crucial aspect of incorporating thermal fluctuations is the inherently time-dependent nature of the stochastic noise field. The amplitude of this thermal field scales with the temporal resolution of the simulation; in other words, the effective strength of the noise depends on the observation frequency. Consequently, the choice of numerical time-step becomes a key parameter in ensuring physically meaningful magnetization dynamics. Temperature was set at room temperature 300 K which is appropriate for technologically relevant conditions [38,39,40,41,42]. Furthermore, a damping coefficient of 0.1 was also utilized suitable for the simulation of corresponding magnetic nanostructures [43,44,45], while the time step was equal to 2.5 × 10−12 s.

3. Results

3.1. Monolayer

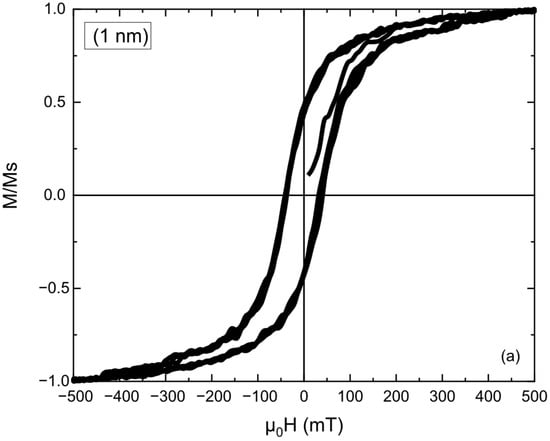

In Figure 1, the simulated hysteresis loops are presented for monolayer L10 FePt films with thicknesses of (a) 1 nm, (b) 2 nm, (c) 5 nm, and (d) 10 nm, obtained under an applied magnetic field of ±500 mT. The evolution of loop shape with increasing thickness reflects changes in coercivity, anisotropy, and the ability of the magnetization to reach saturation within the applied field range. For the 1 nm FePt film (Figure 1a), the hysteresis loop is narrow, indicating low coercivity and incomplete magnetic ordering. Such behavior is typical.

Figure 1.

Simulated in-plane hysteresis loops of monolayer L10 FePt thin films with different thicknesses: (a) 1 nm, (b) 2 nm, (c) 5 nm, and (d) 10 nm. The applied magnetic field range was ±500 mT. The magnetization values are normalized to the saturation magnetization value. The 2 nm film exhibits a more vertical loop shape, indicating a sharper magnetization reversal and near-saturation behavior, while thicker films (5 nm and 10 nm) display more gradual, unsaturated magnetization curves due to strong anisotropy and exchange stiffness.

For ultrathin FePt layers, where surface and interface effects dominate, reducing the effective anisotropy and making the magnetization thermally unstable. At 2 nm thickness (Figure 1b), the loop becomes noticeably more vertical in the central region, indicating a sharper magnetization reversal and stronger anisotropic response. The magnetization approaches full saturation within the applied field range, suggesting that the anisotropy and exchange stiffness are sufficient to stabilize a coherent reversal process while maintaining good field response. Although the coercivity is lower than in thicker films, this configuration provides the best balance between switching sharpness and saturation behavior. For 5 nm and 10 nm FePt layers (Figure 1c,d), the hysteresis loops broaden and exhibit gradual, unsaturated magnetization curves, even at ±500 mT. It is important to note here that the apparent small irregularities in all the hysteresis curves arise from discrete magnetization rearrangements in ultrathin, strongly coupled FePt layers.

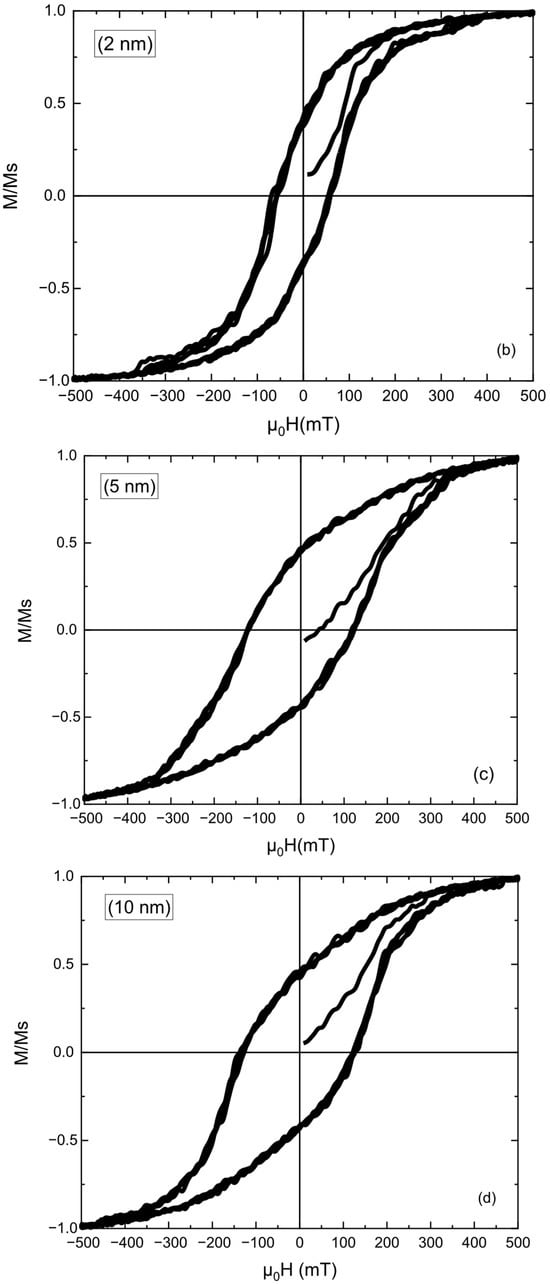

To visualize the magnetization state during the reversal process, snapshots were extracted from OOMMF for selected applied fields. Figure 2 shows the magnetization configuration at positive saturation (a), at coercive field (b), and negative saturation (c). In panel (a), all magnetic moments are uniformly aligned in the direction of the applied positive field, indicating complete saturation. The slight angular deviation visible at the extreme boundaries is a typical effect of exchange and demagnetizing interactions, but remains minimal due to the use of periodic boundary conditions, which significantly suppresses artificial edge curling. At the coercive field (panel (b)), the system exhibits nearly uniform rotation of the magnetic moments as they collectively approach the switching point. No domain nucleation or wall propagation is observed, which supports the claim of coherent as the dominant reversal mechanism for the ultrathin FePt films studied. In panel (c), the moments have fully reversed and align uniformly with the applied negative field, confirming that the system reaches negative saturation symmetrically with respect to the positive branch.

Figure 2.

Top-view (xy-plane) of micromagnetic simulation snapshots showing the magnetic moment orientation distribution in the 150 × 150 nm2 film area: (a) positive saturation, (b) demagnetization region, and (c) negative saturation. Arrows represent the magnetic moments onto the x–y plane. In the saturated states (a,c), the moments are uniformly aligned along the applied field direction, while in the demagnetization region (b), the moments display mixed orientations due to partial reversal near the coercive field.

This incomplete reversal reflects the strong magnetocrystalline anisotropy and exchange stiffness of thicker FePt films, which prevent full alignment of magnetic moments at moderate fields. These films behave as stiff magnets, requiring substantially higher fields for complete magnetization reversal. Overall, the simulation results indicate that the 2 nm FePt layer provides the optimum thickness, achieving a near-saturated state at 500 mT with a sharper magnetization transition. Thinner films (1 nm) are unstable, whereas thicker films (≥5 nm) remain partially unsaturated under the same conditions due to their increased anisotropy and exchange. Note here that this size has already been utilized as optimum in a previous experimental study in THz emission from Fe/Pt spintronic emitters with L10-FePt alloyed interface [46].

3.2. Bilayer

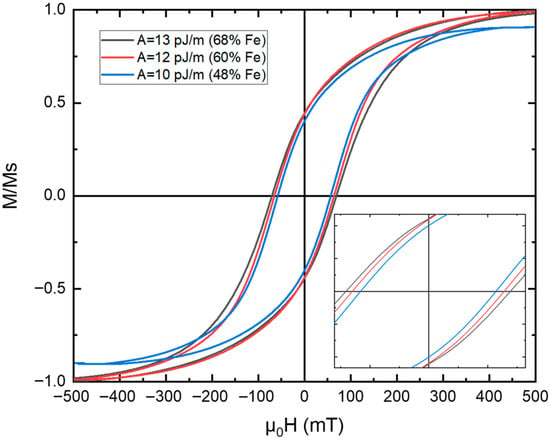

To further explore the effect of soft–hard magnetic coupling, bilayer systems composed of a 2 nm L10 FePt layer and Fe soft layers of 10 nm and 12 nm thickness were simulated. Figure 3 shows the resulting hysteresis loops for these two bilayer configurations. In both cases, the loops are narrow, rectangular, and fully saturated within the applied magnetic field range of ±500 mT. This behavior contrasts sharply with the monolayer FePt films of larger thickness (5 and 10 nm), where strong anisotropy prevents complete magnetization reversal under the same field conditions. The addition of the soft Fe layer markedly enhances the magnetic response, enabling coherent rotation of magnetization throughout the structure. The observed saturation arises from two key factors: (i) the presence of the soft Fe phase, which facilitates magnetization reversal through exchange coupling with the FePt layer, and (ii) the optimized thickness of the FePt layer (2 nm), which ensures sufficient anisotropy for magnetic stability while maintaining effective exchange interactions across the interface. The interfacial exchange stiffness defined in the model () enables a gradual yet complete rotation of the spins, leading to a single-step reversal and a nearly rectangular hysteresis loop. The results confirm that the FePt/Fe bilayer behaves as an exchange-spring magnet, where the hard FePt layer provides the anisotropy and coercivity, while the soft Fe layer contributes to rapid saturation and enhanced remanence. Increasing the Fe layer thickness from 10 nm to 12 nm does not significantly alter the overall shape of the loop, indicating that the exchange coupling remains strong across this thickness range.

Figure 3.

Simulated hysteresis loops of FePt/Fe bilayers with a 2 nm L10 FePt hard layer and soft Fe layers of different thicknesses. The black colored loop corresponds to the FePt(2 nm)/Fe(10 nm) film, while the red colored loop corresponds to the FePt(2 nm)/Fe(12 nm) film. Both bilayers exhibit narrow, rectangular loops and complete saturation within ±500 mT, demonstrating efficient exchange coupling between the hard and soft layers. The soft Fe phase promotes easy magnetization reversal, while the FePt layer maintains coercivity and thermal stability. Inset: Out-of-plane hysteresis loop of the FePt(2 nm)/Fe(10 nm) bilayer. Unlike the in-plane configuration, the loop exhibits a non-rectangular shape with reduced squareness () and higher coercivity. This behavior indicates the presence of strong out-of-plane magnetocrystalline anisotropy arising from the L10-FePt layer and the combined anisotropic coupling within the bilayer structure.

On the whole, the bilayer configuration effectively transforms the system from a rigid single-phase magnet (as in thicker FePt monolayers) to a compliant exchange-spring structure, capable of reaching full saturation at moderate fields.

To further investigate the anisotropic behavior of the optimized bilayer configuration, additional simulations were performed for the out-of-plane magnetic field orientation in the L10-FePt(2 nm)/Fe(10 nm) system. The corresponding hysteresis loop is presented in the inset of Figure 3. In contrast to the in-plane results, which exhibited rectangular and fully saturated loops, the out-of-plane direction produced a non-rectangular hysteresis loop with significantly lower squareness and higher coercivity. Specifically, the ratio of remanent to saturation magnetization () was approximately 36%, indicating that the magnetization does not retain a large remanent component once the external field is removed. This reduction in squareness reflects the competition between the strong in-plane exchange coupling within the Fe layer and the magnetization behavior of the L10-FePt film due to the bulk and out-of-plane magnetocrystalline anisotropy combined with the randomly oriented uniaxial one. The increased coercivity observed in the out-of-plane configuration suggests that the system requires a higher field to overcome the anisotropy barrier when magnetization is forced to deviate from its preferred alignment. Generally, the difference between the in-plane and out-of-plane loops confirms that the FePt/Fe bilayers possess a well-defined uniaxial effective anisotropy, combined with excellent switching performance. This anisotropic behavior could be advantageous for applications requiring tunable magnetization directions, such as magnetic recording or spintronic multilayer architectures.

4. Discussion

The hysteresis loops for FePt monolayers up to 10 nm thickness show pronounced irregularities (abrupt jumps) during magnetization reversal, whereas films thicker than ≈10 nm (we will subsequently show the 20 nm case for different Fe concentrations) display considerably smoother loops and a reduced coercivity that approaches the value observed for the 2 nm film. This systematic change in reversal character can be interpreted in terms of the characteristic exchange length and the dominant reversal mode of the films. The exchange length, , is the characteristic length scale over which exchange energy enforces local uniformity of the magnetization. When structural dimensions (film thickness, domain-wall width, or inhomogeneity size) are of the same order as or smaller than , exchange coupling strongly constrains spatial variations in magnetization, and reversal tends to be non-uniform and localized. Conversely, when the film thickness exceeds , the system can support more extended domain structures, and domain-wall motion becomes the dominant reversal mechanism. In thin films, the exchange length is Lex = (A/Km)1/2, where A is the exchange stiffness constant, and Km is a magnetostatic energy density, Km = 1/2µ0Ms2 (SI) or 2πMs2 (cgs emu) [47].

Using the material parameters employed in our simulations ( J·m−1, A·m−1; J·m−1, A·m−1, Keff_Fe = 4.8 × 104 J/m3 and Keff_FePt = 0.6 × 106 J/m3), the exchange lengths are found to be approximately nm, and nm. For Fe-based alloys, the typical values of Lex lie in the range of 10–20 nm [48,49]. Therefore, both amorphous and nanocrystalline alloys fall under the regime if their thickness is lower than Lex.

The evolution of hysteresis loops with film thickness and Fe concentration can be understood in terms of the exchange length and the corresponding magnetization reversal mechanisms. When the FePt film thickness is comparable to, or smaller than, the characteristic exchange length (), the exchange interaction strongly constrains local variations of magnetization, leading to nonuniform and localized reversal processes. Under these conditions, magnetization switching proceeds through discrete nucleation and depinning events, which appear as abrupt jumps in the simulated hysteresis loops. This behavior was clearly observed in films up to 10 nm, where the effective magnetic coupling is strong and reversal is dominated by local nucleation rather than by domain-wall propagation. The high coercivity in this range arises from the large anisotropy energy barriers that must be overcome during each localized switching event.

When the film thickness exceeds approximately 10 nm, as in the 20 nm samples, the system becomes thicker than the effective exchange length. In this regime, the magnetization can vary more smoothly across the thickness, allowing the formation and propagation of extended domain walls. Consequently, the magnetization reversal becomes collective, the hysteresis loops appear smoother, and the coercivity decreases. This transition marks the crossover from exchange-dominated localized reversal to domain-wall–mediated switching, consistent with typical exchange lengths reported for Fe-based alloys ( nm).

To evaluate how the Fe concentration influences the overall magnetic behavior, three compositions were simulated by adjusting the exchange stiffness constant (), which effectively represents the variation in Fe content within the FePt/Fe alloy system. Based on literature data [50], pJ/m corresponds to approximately 68% Fe, pJ/m to 60% Fe, and pJ/m to 48% Fe.

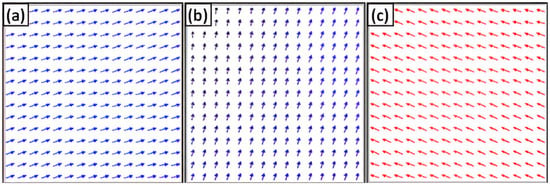

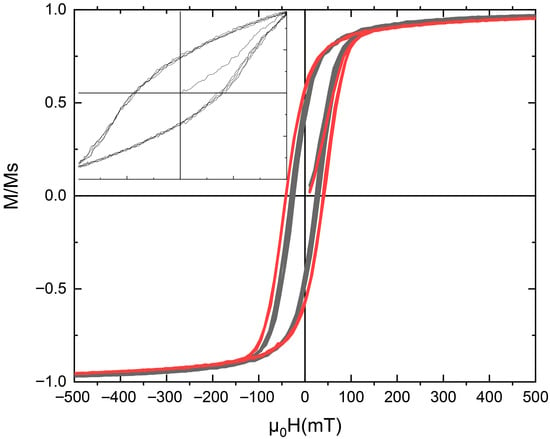

As shown in Figure 4, all three 20 nm films exhibit smooth and nearly rectangular hysteresis loops, with no abrupt magnetization jumps as observed in thinner samples (≤10 nm). The disappearance of discontinuities further confirms that the film thickness exceeds the effective exchange length, allowing the magnetization to reverse through collective domain-wall motion rather than localized switching.

Figure 4.

Simulated hysteresis loops of 20 nm FePt monolayer films for different Fe concentrations. The Fe concentration was indirectly introduced through the exchange stiffness constant : 13 pJ/m (≈68% Fe), 12 pJ/m (≈60% Fe), and 11 pJ/m (≈48% Fe). All films exhibit smooth, saturated loops, confirming the transition to domain-wall–mediated reversal when the thickness exceeds the exchange length. The 48% Fe film shows the lowest coercivity and complete saturation, whereas higher Fe concentrations yield slightly higher coercivity and remanence due to stronger exchange coupling. The inset shows the minor loop (magnification of the major loop in the vicinity of lower magnetic field amplitude) at ±80 mT, where the difference in coercivity between the three different concentrations is evident.

A moderate dependence of coercivity and squareness on Fe content is observed. The 48% Fe composition (A = 11 pJ/m) displays the lowest coercivity and achieves full saturation, consistent with a slightly weaker exchange stiffness that promotes easier domain-wall propagation. In contrast, the 60% and 68% Fe compositions (A = 12–13 pJ/m) exhibit slightly higher coercivity and a marginally larger remanent-to-saturation ratio (), indicating stronger exchange coupling and enhanced magnetic hardness. These trends reflect the direct role of the exchange stiffness in controlling the balance between coercivity and saturation: as A increases with Fe concentration, the system transitions toward a more dynamical magnetic configuration.

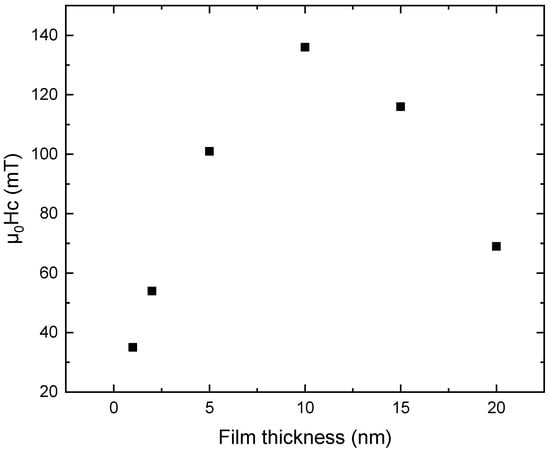

The non-monotonic behavior of the hysteresis loop is illustrated in Figure 5, where the dependence of film thickness on coercive field Hc is depicted. In order to complete the coercivity curve, we also did a simulation for the 15 nm thickness value. The coercivity initially increases sharply from 35 mT at 1 nm to 136 mT at 10 nm, indicating the progressive dominance of the hard magnetic phase as its volume fraction grows. However, when the thickness is further increased to 15 and 20 nm, the coercivity progressively decreases to 116 and 69 mT, respectively, reflecting a transition to a regime where magnetization reversal proceeds primarily through domain-wall motion rather than localized nucleation. This non-monotonic dependence demonstrates the well-known competing effects of anisotropy and exchange coupling [51,52,53,54]: thin films below the exchange length are strongly exchange-dominated and magnetically soft, while thicker films exceed the exchange length, allowing smoother and more collective reversal. The maximum coercivity observed around 10 nm thus marks the crossover between localized and extended reversal modes in the FePt films.

Figure 5.

Dependence of coercivity on FePt-L10 layer thickness obtained from micromagnetic simulations. The coercivity increases from 35 mT at 1 nm to a maximum of 136 mT at 10 nm, followed by a marked decrease to 116 mT at 15 nm and to 69 mT at 20 nm. The latter coercivity value corresponds to the highest iron concentration, namely the 68% value. This non-monotonic behavior reflects the transition from localized magnetization reversal at low thicknesses to domain-wall-mediated reversal when the film thickness exceeds the effective exchange length. The maximum near 10 nm represents the crossover between exchange-dominated and extended reversal regimes in the FePt. This behavior confirms the transition from exchange-dominated reversal at small dimensions to domain-wall-mediated magnetization switching once the total thickness exceeds the exchange length. The observed maximum around 10 nm marks the crossover between these two regimes, providing further evidence of the critical role played by exchange coupling and anisotropy balance in determining the switching behavior of FePt monolayers.

It is clear that the dependence of the loop shape on Fe concentration further supports this interpretation. In the simulations, the Fe content was introduced indirectly through the exchange stiffness constant, following literature correlations: pJ/m for ≈ 68% Fe, pJ/m for ≈ 60% Fe, and pJ/m for ≈ 48% Fe. Increasing Fe concentration enhances the exchange stiffness and slightly increases coercivity and squareness, indicating stronger magnetic coupling and reversibility. Conversely, the 48% Fe sample, with lower A, shows complete saturation and the lowest coercivity, consistent with easier domain-wall motion. This compositional dependence demonstrates that tuning the exchange stiffness offers a practical means of controlling magnetic hardness and reversal sharpness in FePt-L10 systems. The main findings on loop characteristics, regarding the coercive field Hc and remanence magnetization Mr, are summarized in the table below.

The material parameters listed in Table 1 are consistent with previously reported experimental and simulation results on Fe–Pt alloy thin films. In particular, the exchange stiffness values used here (10–13 pJ/m for Fe contents between 48% and 68%) fall within the typical range reported for disordered or partially ordered Fe–Pt alloys, where A increases with Fe concentration due to the enhanced ferromagnetic exchange among Fe–Fe pairs [55]. Coercivity values between 56 and 69 mT for films in the 48–68% Fe range are also consistent with studies showing that reduced Fe content leads to higher anisotropy dispersion and lower exchange stiffness, producing lower coercive fields [20,50]. Likewise, the gradual increase in normalized remanence with Fe content follows well-established magnetization trends in Fe-rich Fe–Pt alloys, where a higher and stronger exchange lead to more coherent remanent states [56]. These references collectively support the material parameter choices adopted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Magnetic properties of L10 thin films for the various iron concentrations.

The above analysis confirms that both film thickness and exchange stiffness (Fe concentration) critically determine the reversal mechanism and coercive behavior of FePt-based thin films. When the structural dimensions exceed the exchange length, the magnetization reversal transitions from localized, jump-like switching to collective domain-wall motion, resulting in smoother loops and reduced coercivity. These results establish a direct link between the simulated hysteresis features and the intrinsic micromagnetic length scales governing the behavior of exchange-coupled magnets. Although the Gilbert damping parameter influences the transient magnetization dynamics, such as precessional relaxation or domain-wall mobility, it does not affect the equilibrium states that define the quasistatic hysteresis loops. In this work, an intermediate [42,43,44] damping value (α = 0.1) was employed to accelerate numerical convergence at each magnetic-field step, without altering coercivity, remanence, or saturation behavior. Additional test simulations in the recent literature [57] performed for values of α = 0.01 and α = 1.0 confirmed that the final hysteresis curves remained unchanged, indicating that the reported results are robust against variations in damping. The literature confirms that in micromagnetic simulations, the final static (quasi-static) hysteresis loop is generally considered independent of the damping constant [58,59]. The damping only affects the time it takes to reach the equilibrium state, not the equilibrium state itself. Since the objective of this study is to analyze equilibrium reversal processes rather than dynamic switching pathways, the selected damping parameter provides reliable quasistatic behavior for both monolayer FePt and FePt/Fe bilayer structures.

The energy product (BH)max is a key figure of merit for exchange-spring systems, as it quantifies the achievable magnetic work density and directly reflects the balance between coercivity and saturation magnetization. Although micromagnetic simulations provide detailed reversal dynamics, an analytical perspective helps interpret the observed trends in FePt/Fe bilayers. In a classical exchange-spring model, the hard layer provides high anisotropy and coercivity, while the soft layer contributes its large saturation magnetization; the maximum energy product is optimized when the soft layer thickness remains below the exchange penetration depth, ensuring effective exchange coupling. Our results align with this framework: the 2 nm L10 FePt layer maintains the rigidity needed to pin the Fe layer, while the 10–12 nm Fe thickness allows formation of a smooth spiral-like rotation profile, indicative of efficient spring behavior. According to the analytical condition derived by Kneller and Hawig [60], the critical soft-layer thickness ; thus, our Fe thickness values fall within the expected exchange-spring regime. Future work combining these simulations with an analytical estimation of (BH)max will allow direct quantification of the energy product and enable optimization of FePt/Fe bilayers for high-performance permanent-magnet and HAMR-related applications.

5. Conclusions

Micromagnetic simulations were carried out to investigate the magnetic behavior of L10 FePt monolayers and FePt/Fe bilayer thin films. The analysis of the FePt monolayer revealed a strong dependence of coercivity on film thickness. As the thickness increased from 1 to 10 nm, the coercivity rose markedly, reaching a maximum at 10 nm, before decreasing again at 15 nm to 20 nm. This non-monotonic evolution reflects a transition in the magnetization reversal mechanism: thin films below the exchange length exhibit localized switching with lower coercivity, while thicker films above this scale reverse collectively through domain-wall motion, leading to smoother loops and reduced coercivity. Variations in Fe concentration, modeled through the exchange stiffness constant, further confirmed that higher Fe content enhances magnetic rigidity and coercivity, whereas lower Fe fractions promote easier reversal and complete saturation.

Building on these results, FePt/Fe bilayer systems were simulated using the optimal FePt thickness of 2 nm, combined with Fe layers of 10 nm and 12 nm. In both cases, the bilayers exhibited rectangular, narrow hysteresis loops and full saturation at the applied field of 500 mT, confirming efficient exchange coupling between the hard (FePt) and soft (Fe) layers. The results indicate that reducing the FePt thickness transforms the system from a rigid magnet into an exchange-spring configuration, where the soft Fe layer assists the magnetization reversal of the hard FePt phase. Out-of-plane simulations of the 2 nm FePt/10 nm Fe bilayer further demonstrated a non-rectangular loop with higher coercivity and lower squareness, consistent with strong out-of-plane uniaxial anisotropy arising from the L10-FePt layer.

Consequently, the study establishes that a 2 nm FePt layer provides an optimal balance between saturation, coercivity, and stability, making it the most suitable configuration for designing exchange-spring-type FePt/Fe thin films. These findings contribute to a better understanding of thickness- and composition-dependent micromagnetic behavior in FePt-based nanostructures and can guide the optimization of high-performance magnetic materials for data storage and spintronic applications.

Looking forward, these findings provide quantitative guidance for engineering ultrathin FePt-based exchange-spring structures for spintronic devices and energy-efficient recording media. A natural next step is to experimentally validate the predicted hysteresis trends and domain configurations, especially near the exchange length limit, and to evaluate the maximum energy product using combined analytical and micromagnetic methods. Extending the simulations to finite-temperature stochastic LLG dynamics and exploring the influence of interfacial roughness, grain boundaries, and real microstructural effects will further connect these modeling results to the technologically relevant FePt-based nanomagnet architectures.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study does not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Evangelos Papaioannou from the Physics Department of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki for his invaluable guidance during the conceptualization phase of this research and for engaging in insightful discussions that significantly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goh, C.K.; Yuan, Z.M.; Liu, B. Magnetization reversal in enclosed composite pattern media structure. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 083920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, D.; Parker, G.; Mosendz, O.; Lyberatos, A.; Mitin, D.; Safonova, N.Y.; Albrecht, M. Review article: FePt heat-assisted magnetic recording media. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2016, 34, 060801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simizu, S.; Obermyer, R.T.; Zande, B.; Chandhok, V.K.; Margolin, A.; Sankar, S.G. Exchange coupling in FePt permanent magnets. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 8134–8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sheng, W.; Bai, J.; Cao, J.; Lou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, F.; Lu, J. Magnetic properties and magnetization reversal process of L10 FePt/Fe bilayer magnetic thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 8124–8127. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhou, S.M.; Ge, J.J.; Du, J.; Sun, L. Magnetization reversal mechanism of perpendicularly exchange-coupled composite bilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 123903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, D.; Lee, J.; Brombacher, C.; Schubert, C.; Fuger, M.; Suess, D.; Fidler, J.; Albrecht, M. Perpendicular FePt-based exchange-coupled composite media. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 062501. [Google Scholar]

- Baldasseroni, C.; Bordel, C.; Gray, A.X.; Kaiser, A.M.; Kronast, F.; Herrero-Albillos, J.; Schneider, C.M.; Fadley, C.S.; Hellman, F. Temperature-driven nucleation of ferromagnetic domains in FeRh thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 262401. [Google Scholar]

- Granitzka, P.W.; Jal, E.; Le Guyader, O.; Savoini, M.; Higley, D.J.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Chase, T.; Ohldag, H.; Dakovski, G.L.; et al. Magnetic switching in granular FePt layers promoted by near-field laser enhancement. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 2426–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victora, R.H.; Shen, X. Exchange coupled composite media for perpendicular magnetic recording. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2005, 41, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvaro, G.; Albertini, F.; Agostinelli, E.; Casoli, F.; Fiorani, D.; Laureti, S.; Lupo, P.; Ranzier, P.; Astinchap, B.; Testa, A.M. Magnetization reversal mechanism in perpendicular exchange-coupled Fe/L10–FePt bilayers. N. J. Phys. 2012, 14, 073008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Huang, P.W.; Ju, G.P.; Victora, R.H. Thermal switching probability distribution of L10 FePt for heat assisted magnetic recording. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 182405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethole, N.; Ngoepe, P.; Chauke, H. Compositional dependence of magnetocrystalline anisotropy, magnetic moments, and energetic and electronic properties on Fe–Pt alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehagias, T.; Karfaridis, D.; Ballani, C.; Mihalceanu, L.; Hauser, C.; Vasileiadis, I.G.; Dimitrakopulos, G.P.; Vourlias, G.; Papaioannou, E.T. Magnetization reversal and dynamics in epitaxial Fe/Pt spintronic bilayers stimulated by interfacial Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Materials 2021, 14, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, D.; Mosendz, O.; Parker, G.; Pisana, S.; Santos, T.S. L10 FePtX–Y Media for Heat-Assisted Magnetic Recording. Phys. Status Solidi A 2013, 210, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamoto, M.; Nakamura, M.; Ohtake, M.; Inaba, N.; Shimotsu, T. Growth of L1-ordered crystal in FePt and FePd thin films on MgO(001) substrate. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 085302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kurihara, K.; Ya, X.; Bai, X.; Kanai, Y. Micromagnetic simulation of microwave-assisted magnetization switching and signal recording characteristics for exchange-coupled composite media with layer anisotropy structure. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 587, 171332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Sun, C.; Acharya, R.; Wang, J.-P. Structural and Magnetic Properties of a Core–Shell-Type L10 FePt/Fe Exchange-Coupled Nanocomposite with Tilted Easy Axis. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 083907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Gilbert, D.A.; Neu, V.; Schäfer, R.; Zheng, J.G.; Yan, X.Q.; Shi, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, S.M. Magnetization reversal in perpendicularly magnetized L1 FePd/FePt heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 033922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locovei, C.; Torosyan, G.; Papaioannou, E.T.; Crisan, A.D.; Beigang, R.; Crisan, O. Structural, Magnetic and THz Emission Properties of Ultrathin Fe/L10-FePt/Pt Heterostructures. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S.; Mihalceanu, L.; Schweizer, M.R.; Lang, P.; Heinz, B.; Geilen, M.; Brächer, T.; Pirro, P.; Meyer, T.; Conca, A.; et al. Determination of the spin Hall angle in single-crystalline Pt films from spin pumping experiments. N. J. Phys. 2018, 20, 053002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karfaridis, D.; Mihalceanu, L.; Keller, S.; Simeonidis, K.; Dimitrakopulos, G.P.; Kehagias, T.; Papaioannou, E.T.; Vourlias, G. Influence of the Pt thickness on the structural and magnetic properties of epitaxial Fe/Pt bilayers. Thin Solid Film. 2020, 694, 137716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, A. Evaluation of the exchange stiffness constants of itinerant magnets at finite temperatures from first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 93, 054705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Sun, C.; Acharya, R.; Wang, J.P. L10 FePt/Fe exchange coupled composite structure on MgO substrates. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 2345–2348. [Google Scholar]

- Casoli, F.; Albertini, F.; Nasi, L.; Fabbrici, S.; Cabassi, R.; Bolzoni, F.; Bocchi, C. Strong coercivity reduction in perpendicular FePt/Fe bilayers due to hard/soft coupling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 142506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, M. The fascinating world of the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation: An overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, M.J.; Porter, D.G. OOMMF User’s Guide; Release 1.2a; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2002. Available online: http://math.nist.gov/oommf/ (accessed on 30 October 2002).

- Bertotti, G.; Mayergoyz, I.D.; Serpico, C. Chapter 2—Basic equations for magnetization dynamics. In Nonlinear Magnetization Dynamics in Nanosystems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, T.L. A Lagrangian formulation of the gyromagnetic equation of the magnetic field. Phys. Rev. 1955, 100, 1243. [Google Scholar]

- Ghidini, G.; Asti, G.; Pellicelli, R.; Pernechele, C.; Solzi, M. Magnetic properties of Fe-based thin films. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2007, 316, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X. Magnetic and structural properties of FePt films. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 073910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennhofer, M.; Kozlowski, M.; Laenens, B.; Sepiol, B.; Kozubski, R.; Smeets, D.; Vantomme, A. Study of reorientation processes in L10-ordered FePt thin films. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 2069–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullity, B.D.; Graham, C.D. Introduction to Magnetic Materials, 2nd ed.; Wiley-IEEE Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiadis, I.G.; Karfaridis, D.; Maniotis, N.; Ignatova, K.; Arnalds, U.B.; Vourlias, G.; Dimitrakopulos, G.P.; Papaioannou, E.; Kehagias, T. Tunable magnetic properties in compositionally graded L10 -FePt thin films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.F.L.; Chantrell, R.W.; Nowak, U. The Stochastic Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert Equation. In Handbook of Magnetism and Advanced Magnetic Materials; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, A.E. Stabilisation of the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation for numerical solution via standard methods. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleják, P.; Lezier, G.; Vala, D.; Mathmann, B.; Halagačka, L.; Gelnárová, Z. Maximizing the electromagnetic efficiency of spintronic terahertz emitters. Adv. Photonics Res. 2024, 5, 2400064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfrath, T.; Battiato, M.; Maldonado, P.; Eilers, G.; Nötzold, J.; Mährlein, S.; Zbarsky, V.; Freimuth, F.; Mokrousov, Y.; Blügel, M.; et al. Terahertz spin current pulses controlled by magnetic heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challener, W.A.; Peng, C.; Itagi, A.V.; Karns, D.; Peng, W.; Peng, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, X.; Gokemeijer, N.; Seigler, M.A.; et al. Heat-Assisted Magnetic Recording by a Near-Field Transducer with Efficient Optical Energy Transfer. Nat. Photon. 2009, 3, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xiao, T.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Peng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Yin, H.; et al. A Controllability Investigation of Magnetic Properties for FePt Alloy Nanocomposite Thin Films. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perzanowski, M.; Zarzycki, A.; Gregor-Pawlowski, J.; Marszalek, M. Structural and Magnetic Properties of FePt Thin Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 39926–39934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iihama, S.; Mizukami, S.; Naganuma, H.; Oogane, M.; Ando, Y.; Miyazaki, T. Gilbert damping constants of Ta/CoFeB/MgO(Ta) thin films measured by optical detection of precessional magnetization dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 174416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Bentley, P.D.; Nakazawa, K.; Hiroto, T.; Isogami, S.; Suto, H.; Takahashi, Y.K. Damping Modification in Epitaxially Grown Continuous L10-FePt Thin Films with Different Substrates. Available online: https://www.kiroku.riec.tohoku.ac.jp/tmrc/files/P2-14.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Suess, D.; Lee, J.; Fidler, J.; Schrefl, T. Exchange-coupled perpendicular media. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, L.; Ruhwedel, M.; Karfaridis, D.; Vasileiadis, I.G.; Sokoluk, D.; Torosyan, G.; Vourlias, G.; Dimitrakopoulos, G.P.; Rahm, M.; Hillebrands, B.; et al. THz emission from Fe/Pt spintronic emitters with L10-FePt alloyed interface. iScience 2022, 25, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo, G.S.; Hong, Y.K.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, W.; Choi, B.C. Definition of magnetic exchange length. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 4937–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, G. Anisotropies in soft magnetic nanocrystalline alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005, 294, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipgen, L.; Fulara, H.; Raju, M.; Chaudhary, S. In-plane magnetic anisotropy and coercive field dependence upon thickness of CoFeB. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 3118–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniak, C.; Lindner, J.; Fauth, K.; Thiele, J.-U.; Minár, J.; Mankovsky, S.; Ebert, H.; Wende, H.; Farle, M. Composition dependence of exchange stiffness in FexPt1−x alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 064403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachowicz, T.; Ehrmann, A. Exchange bias in thin films—An update. Coatings 2021, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Hu, J.F.; Lim, B.C.; Ding, Y.F.; Chow, G.M.; Ju, G. Development of L1(0) FePt:C (001) Thin Films With High Coercivity and Small Grain Size for Ultra-High-Density Magnetic Recording Media. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Lim, B.C.; Ding, Y.F.; Chow, G.M. Low-temperature deposition of L1(0) FePt films for ultra-high density magnetic recording. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 303, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-L.; Sun, C.-Y.; Lin, J.-H.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Tsai, H.-T. Magnetic properties and microstructure of FePt(BN, X, C) (X = Ag, Re) films. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler, J.; Schrefl, T.; Scholz, W.; Suess, D.; Dittrich, R.; Kirschner, M. Micromagnetic modelling and magnetization processes. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2004, 272, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidov, V.E.; Jersch, J.; Rott, K.; Krzysteczko, P.; Reiss, G.; Demokritov, S.O. Nonlinear propagation of spin waves in microscopic magnetic stripes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 177207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Johns, R.T. Modeling of Relative Permeability Hysteresis Using Limited Experimental Data and Physically Constrained ANN. Transp. Porous Med. 2025, 152, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, A.; Van de Wiele, B. MuMax: A new high-performance micromagnetic simulation tool. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2011, 323, 2585–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhilah, U.; Kurniawan, C.; Djuhana, D. Investigation of Dynamic Magnetization in FePt and FePd Disk Ferromagnets Using Micromagnetic Simulation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 553, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, J.; Schrefl, T. Micromagnetic modelling of hard magnetic materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2000, 33, R135–R150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skomski, R. Simple Models of Magnetism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kneller, E.F.; Hawig, R. The exchange-spring magnet: A new material principle for permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1991, 27, 3588–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.