Abstract

Magnetooptics (MO) explores light—matter interactions in magnetized media and has advanced rapidly with progress in materials science, spectroscopy, and integrated photonics. This review highlights recent developments in fundamental principles, experimental techniques, and emerging applications. We revisit the canonical MO effects: Faraday, MO Kerr effect (MOKE), Voigt, Cotton—Mouton, Zeeman, and Magnetic Circular Dichroism (MCD), which underpin technologies ranging from optical isolators and high-resolution sensors to advanced spectroscopic and imaging systems. Ultrafast spectroscopy, particularly time-resolved MOKE, enables femtosecond-scale studies of spin dynamics and nonequilibrium processes. Hybrid magnetoplasmonic platforms that couple plasmonic resonances with MO activity offer enhanced sensitivity for environmental and biomedical sensing, while all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces provide low-loss, high-efficiency alternatives. Maxwell-based modeling with permittivity tensor () and machine-learning approaches are accelerating materials discovery, inverse design, and performance optimization. Benchmark sensitivities and detection limits for surface plasmon resonance, SPR and MOSPR systems are summarized to provide quantitative context. Finally, we address key challenges in material quality, thermal stability, modeling, and fabrication. Overall, magnetooptics is evolving from fundamental science into diverse and expanding technologies with applications that extend far beyond current domains.

1. Introduction

Magnetooptics (MO) explores the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and magnetized media, providing critical insights into spin dynamics, optical manipulation, and quantum behavior in materials [1,2]. The pioneering contributions of Michael Faraday [3] and John Kerr [4] in the 19th century revealed how magnetic fields could alter the polarization and reflection properties of light, phenomena that now underpin key applications such as optical isolators [5,6], high-precision sensors [7], and magnetooptical data storage systems [8], to name a few.

James Clerk Maxwell’s unification of electromagnetic theory further formalized the underlying principles [9,10], setting the stage for the modern evolution of magnetooptical technologies. Today, MO effects serve as indispensable tools in diverse fields, including spintronics [11,12,13], optical communication [14,15], data storage [8,16], quantum computing [17], and nanophotonics [18], among many others.

Technological breakthroughs in ultrafast laser systems [19,20,21], material engineering [6,22,23], and nanofabrication [24] have propelled MO research into femtosecond and nanoscale domains [25]. Advanced characterization techniques [26,27] such as the time-resolved magnetooptical Kerr effect (TR-MOKE) [28], magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) [29], and Kerr microscopy [27] now enable real-time imaging [30] of magnetic domain structures and spin dynamics [19,20] at ultrafast timescales [31].

Simultaneously, the integration of MO effects with plasmonic structures has led to the emergence of magnetoplasmonics [32,33]. These hybrid platforms leverage both magnetic and optical resonances to significantly increase sensitivity, spatial resolution, and functional diversity for applications such as environmental monitoring, biosensing, and optical modulation, among others [7,34]. The rise of all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces presents a promising alternative to metallic architectures by minimizing optical losses while preserving strong MO coupling [35,36,37]. In addition, computational approaches driven by artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly being used to model, design, and optimize complex MO devices [38,39,40,41].

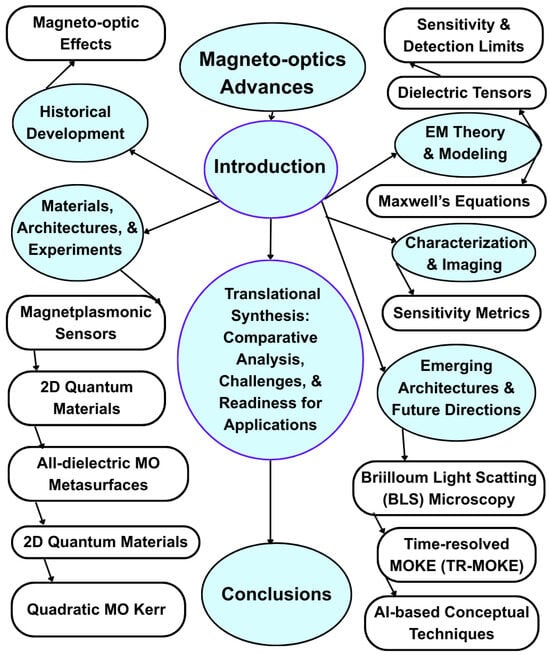

Figure 1 shows a unified conceptual framework of MO and advances in magnetoplasmonics (MP), capturing the organization and interconnections of the review. The diagram begins with the Introduction, which sets the stage for discussions on the foundational aspects of the field. From this starting point, the framework branches into multiple themes that collectively define the scope of current research.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of key themes and research directions in magnetooptics and magnetoplasmonics, linking theory, materials, devices, and characterization techniques. Central nodes (blue) represent major thematic categories, while white nodes denote subtopics within each theme. Arrows indicate conceptual flow and relationships between sections, illustrating how foundational principles lead to applied research directions and conclusions.

The development of MO is presented alongside the core understanding of MO effects, both of which provide context for subsequent innovations. Building on these foundations, the discussion extends into materials, architectures, and experiments, encompassing advances in MP sensors, 2D quantum materials, all-dielectric MO metasurfaces, and quadratic MO Kerr effects.

These emerging material platforms highlight the expansion of magnetooptical phenomena into new domains of nanoscale engineering [42,43]. Recent studies, including the work of Gabbani et al. on doped transparent conductive oxide (TCO) nanocrystals, further demonstrate that carefully engineered nanoparticles can surpass the magnetoplasmonic performance of conventional noble metals by nearly an order of magnitude [44,45].

Building on these advances, current research increasingly emphasizes novel device architectures and emerging application frontiers. These efforts encompass next-generation photonic platforms, multifunctional sensing paradigms, and spintronic integrations that collectively expand the translational potential of magnetooptical systems [34].

Central to this progression is the integrative framework of Translational Synthesis: Comparative Analysis, Challenges, and Readiness for Applications (see Section 7). This framework systematically evaluates performance trade-offs, identifies key barriers, including thermal stability, fabrication complexity, and reproducibility, and assesses the technological maturity required for real-world deployment. In doing so, this review bridges the gap between fundamental discoveries and application-ready solutions, culminating in perspectives that consolidate current insights and highlight emerging opportunities.

2. Historical and Theoretical Foundations of Magnetooptics

2.1. Historical Background

Magnetooptics (MO) traces its foundation to Michael Faraday’s 1845 discovery that a magnetic field can rotate the plane of polarization of transmitted light, now known as the Faraday effect [3]. This was followed by Kerr’s 1877 observation that the polarization state of reflected light depends on the magnetization, M of a material, establishing the MO Kerr effect (MOKE) [4]. These two findings first demonstrated a direct interaction between light and magnetic order. The theoretical framework for these effects was later solidified through Maxwell’s unification of electricity, magnetism, and light [9,46], which laid the groundwork for interpreting MO phenomena in terms of electromagnetic wave—matter interactions. Subsequent milestones include the discovery of Zeeman splitting in magnetic fields [47,48] and the development of quadratic MO effects by Voigt and Cotton—Mouton [49,50], broadening the understanding of optical responses to magnetic symmetry.

Historical records prior to these scientific developments describe magnets and optical phenomena separately but do not indicate any awareness of a coupling between them. For example, the Sushruta Samhita documents the medical use of lodestones for extracting iron from wounds [51,52], while Ibn al-Haytham’s Book of Optics presents a foundational theory of vision and optical propagation [53]. However, neither tradition connects magnetism with optical behavior. The realization that light can actively probe or manipulate magnetic states is, therefore, a distinctly modern concept, further advanced in the 20th and 21st centuries through synchrotron-based spectroscopies and ultrafast laser techniques, which revealed femtosecond spin dynamics and enabled all-optical magnetization switching [54,55]. Today, MO effects, including the Faraday, Kerr, and Voigt effects, among others, are described using tensorial dielectric models that capture both anisotropy and non-reciprocity [56]. These theoretical foundations underpin modern advances in spintronics, nanophotonics, and sensing, underscoring the enduring importance of rigorous electromagnetic theory in driving progress within magnetooptical science [1].

The evolution of MO has been shaped by pivotal discoveries and technological milestones that span more than a century [9,43]. Early investigations were constrained by weak and incoherent light sources, limiting the detection of subtle MO phenomena [57]. However, the development of lasers in the mid-20th century transformed the field [58,59,60,61,62], enabling precise control and detection of polarization effects such as the Faraday and Kerr effects, now foundational to modern MO systems [3,4].

With the advent of synchrotron radiation and X-ray techniques in the twentieth century [43,63], MO research entered a new era of precision and depth. These developments enabled element-specific imaging of magnetic domains through X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) [64] and related high-energy probes [63], vastly expanding the experimental landscape for probing magnetic and electronic structures at the nanoscale. By the 2000s, nonlinear optics and ultrafast laser technology had enabled sub-picosecond probing of spin, charge, and lattice dynamics, catalyzing the emergence of magnetoplasmonics, a synergistic field that combines surface plasmon resonances with MO effects [20,65]. These hybrid systems improved light-matter interaction at the nanoscale and enabled applications in biosensing, photonic modulation, and environmental diagnostics [34,66].

Recent research has expanded to 2D materials, such as graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides, which exhibit strong MO responses and tunable electronic properties [67]. Moreover, terahertz and X-ray MO studies have uncovered new regimes of spin-lattice interactions and quantum phenomena, supported by high-brilliance synchrotron and free-electron laser sources [68,69]. These improvements continue to guide research into novel materials and fabrication techniques, reinforcing magnetooptics as a driving force in next-generation quantum and photonic technologies [24,70]. Integrating MO materials into practical devices remains a challenge due to issues such as thermal stability, reproducibility, and system integration [6,40,71,72]. It faces hurdles such as waveguide birefringence and material compatibility [6]. These findings highlight the need for further research to improve device performance and reliability.

The availability of advanced light sources has also expanded the scope of MO research to new materials and effects [73,74,75,76,77,78]. For example, early studies focused on ferromagnetic materials because of their strong magnetooptical responses [60,79]. Later, the development of sophisticated spectroscopic techniques allowed researchers to explore antiferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic systems, uncovering complex interactions that were previously inaccessible [69,80,81,82]. Table 1 presents a comprehensive timeline of major developments in magnetooptics and related technologies from 2008 to 2025, offering valuable historical insights into the evolution and convergence of magnetooptical science, nanophotonics, and magnetoplasmonics [83].

Table 1.

Comprehensive timeline of major developments in magnetooptics (MO) and magnetoplasmonics (MP) from 2008 to 2025, illustrating the progression of theoretical models, material platforms, and device innovations that have driven the field’s evolution [83].

With this historical context established, we now turn to the fundamental principles of magnetooptics, which describe how magnetic fields influence the propagation and polarization of light in magnetized media. Building on these foundations, magnetoplasmonics, an interdisciplinary field combining magnetooptics and plasmonics, extends these interactions to the nanoscale, where collective electron oscillations (plasmons) couple with magnetic phenomena to yield enhanced and tunable light—matter responses.

2.2. Theoretical Foundations of Magnetooptics

At its core, magnetooptics (MO) refers to the study of how magnetic fields affect the propagation of electromagnetic waves in materials, including magnetic media, dielectric substances, and their composites [1,100]. In MO materials, permittivity, becomes a tensor to account for the anisotropic and non-reciprocal behavior introduced by magnetization, or applied magnetic fields. The off-diagonal elements of this tensor are responsible for MO effects [101]. For example, the dielectric tensor in the presence of a magnetic field in all three directions can be expressed as [1,5,43,102,103,104,105,106,107,108]:

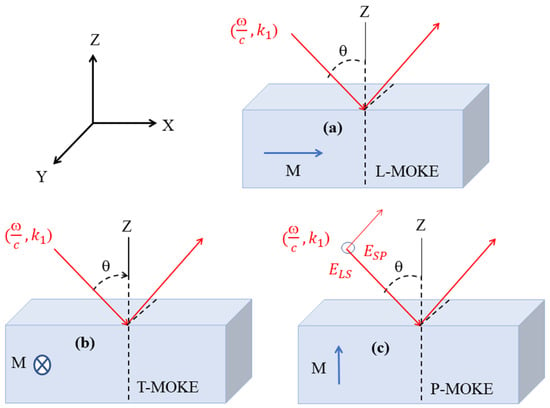

where, the permittivity tensors , , and correspond to the longitudinal, transverse, and polar magnetooptical configurations, respectively, with their coordinate axes defined in Figure 2. This figure also depicts the associated experimental setups, showing the incidence angle , the wave vector of the incident and reflected beams , and the electric-field components that govern the observed Kerr response.

Figure 2.

Main configurations of the MO Kerr effect (MOKE), expressed in terms of the interaction between the incident electromagnetic wave , the reflected wave, and the M vector [1]. (a) L-MOKE (Longitudinal configuration): lies in the plane of incidence and parallel to the sample surface. (b) T-MOKE (Transverse configuration): is parallel to the sample surface and perpendicular to the plane of incidence. (c) P-MOKE (Polar configuration): is oriented ⊥ to the sample surface.

According to Maxwell’s curl equations, and , where denotes the magnetization-induced current, the magnetooptical Kerr response originates from the coupling between electromagnetic fields and the magnetization-dependent off-diagonal elements of the permittivity tensor. Depending on the orientation of the magnetization vector relative to the plane of incidence and the sample surface, three distinct Kerr geometries emerge. In the longitudinal configuration (), lies parallel to both the surface and the plane of incidence, resulting in coupling between the y and z tensor components (). In the transverse configuration (), is oriented perpendicular to the plane of incidence, leading to coupling in the components (). In the polar configuration (), is aligned normal to the surface, producing off-diagonal coupling between the x and z components (). These orientations define the principal MOKE geometries illustrated in Figure 2.

A comparative summary of the three principal MOKE geometries: longitudinal, polar, and transverse, is presented in Table 2, extending the configurations previously introduced in Figure 2. While Figure 2 outlines the conceptual distinctions among these geometries, Table 2 highlights their specific magnetization sensitivities and typical application domains, including thin films, perpendicular anisotropy systems, and surface-sensitive measurements.

Table 2.

Comparison of the three principal MOKE configurations: longitudinal (L-MOKE), polar (P-MOKE), and transverse (T-MOKE) highlighting their sensitivity and representative application areas in thin films, surface magnetism, and systems with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy.

Building on the tensorial framework expressed in Equation (1), the coupling between electromagnetic waves and magnetization gives rise to six fundamental magnetooptical (MO) effects, each associated with distinct geometric configurations and material parameters.

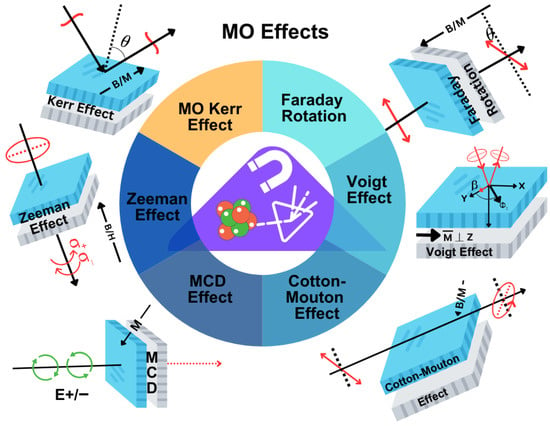

As illustrated in Figure 3, these effects form the basis of modern magnetooptical phenomena. We first consider Faraday rotation, historically the earliest observed MO effect, which arises when linearly polarized light propagates parallel to the applied magnetic field in a magnetized medium [3]. In such a medium, the presence of magnetization, breaks time-reversal symmetry and induces optical anisotropy, causing the refractive indices for the right- and left-circularly polarized light components to differ () [84].

Figure 3.

Comprehensive illustration of the six fundamental magnetooptic (MO) effects: Faraday rotation, MO Kerr effect, Zeeman effect, Voigt effect, Cotton—Mouton effect, and magnetic circular dichroism (MCD). Each effect is shown with its corresponding nanostructure configuration, indicating the orientation of the relative to the sample surface and the plane of incidence. The incident and reflected lights are represented by their wavevectors , and polarization states are shown by the E-field symbols. Gray regions denote the magnetic medium, while blue shading indicates the surrounding dielectric. Selected arrows and line styles highlight key physical features: red arrows show light propagation, polarization symbols indicate rotation or ellipticity changes, dashed lines mark the surface normal, and blue arrows denote the H-field direction ( or ), distinguishing the symmetry conditions of each MO effect.

As these two components accumulate a relative phase shift while traversing the material, the plane of polarization of the transmitted light rotates at an angle given by [5,105,106,107]:

where V is the Verdet constant, an intrinsic material parameter that quantifies the MO activity, B is the magnetic flux density, and d is the optical path length through the medium. The sign and magnitude of depend both on the direction of and on the dispersive nature of . This rotation, known as the Faraday effect forms the physical basis for optical isolators, circulators, and fiber-based magnetic field sensors [6,108], where controlled non-reciprocal light propagation is essential.

The magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE) represents another fundamental manifestation of magnetooptical interactions, describing changes in the polarization state of light upon reflection from a magnetized surface. As the physical origin, tensorial description, and experimental geometries of MOKE have already been discussed in detail in the preceding part of this section, they are not repeated here. Briefly, MOKE is commonly classified into longitudinal, transverse, and polar configurations, determined by the orientation of the magnetization vector relative to the sample surface and the plane of incidence, as illustrated earlier in Figure 2.

Having outlined the magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE), which arises from -dependent modifications of reflected light, we now consider magnetooptical phenomena that occur in transmission geometries. As illustrated in Figure 3, the Cotton—Mouton effect represents such a case, wherein a magnetic field applied perpendicular to the direction of light propagation induces birefringence in otherwise isotropic media, such as gases or liquids. This effect exhibits a quadratic dependence on the magnetic field strength, expressed as , highlighting the influence of magnetic ordering even in non-magnetic materials.

However, magnetooptical phenomena are not restricted to refractive-index modulation alone. A particularly important manifestation involves differential light absorption, most prominently observed in Magnetic Circular Dichroism (MCD). MCD describes the unequal absorption of left- and right-circularly polarized light in a magnetized medium, originating from magnetic field—induced symmetry breaking, and can be expressed as:

where and are the absorption coefficients for right- and left-circularly polarized light, respectively. It serves as a powerful probe of electronic structure, molecular magnetism, and spin-state dynamics [64].

Magnetic skyrmions, which arise from the interplay of exchange interactions, spin—orbit coupling, and external magnetic fields, constitute a prominent class of topologically nontrivial spin textures and have attracted significant interest for both fundamental studies and potential spintronic applications [109].

Within this broader context, we next consider the Zeeman effect, which describes the magnetic-field-induced splitting of atomic or molecular energy levels, resulting in distinct spectral features [48]. The Zeeman interaction underpins many spectroscopic probes of magnetic order and plays a central role in characterizing magnetic anisotropy, symmetry breaking, and spin-dependent energy landscapes in both conventional magnetic systems and complex spin textures such as skyrmions. Depending on the role of spin—orbit coupling, the effect is classified into normal and anomalous Zeeman regimes, with important implications for magnetooptical response and spin-resolved spectroscopy.

In astrophysics, Zeeman splitting serves as a key diagnostic of stellar and interstellar magnetic fields, whereas in condensed matter, it provides insight into electron spin dynamics and band structure modifications [47,110]. The quantitative analysis of line splitting, , continues to serve as a benchmark for testing fundamental theories of magnetism and quantum mechanics. In this expression, is the Zeeman energy splitting, g is the Landé g-factor, is the Bohr magneton, is the magnetic quantum number associated with the total angular momentum, and B is the external magnetic field strength.

Also known as linear magnetic birefringence, the Voigt effect appears in anisotropic crystals under magnetic fields that are perpendicular to the light propagation [111,112]. It alters the refractive index based on polarization and enables precise control in optical modulators and sensors. Unlike the Faraday effect, which is odd in the magnetic field, the Voigt effect is quadratic (), making it useful for high-field measurements and material characterization. It plays an important role in the design of magnetooptical modulators for telecommunication systems and can enhance the contrast in magnetooptical imaging. Moreover, the Voigt effect provides a pathway for non-destructive probing of hidden magnetic orders and excitonic states in complex oxides and semiconductor heterostructures.

Taken together, the six principal magneto-optical effects offer complementary perspectives on how magnetic fields influence light—matter interactions. Table 3 provides a concise comparison of their underlying physical mechanisms and highlights their diverse technological applications, ranging from spectroscopy and sensing to optical communication and advanced magnetic materials research. Having established the key MO effects, we now proceed to introduce the sensitivity metrics used to evaluate their detection performance.

Table 3.

Comparison of all six MO effects, including their physical descriptions and key applications in fields such as magnetooptical storage, spectroscopy, and advanced materials research.

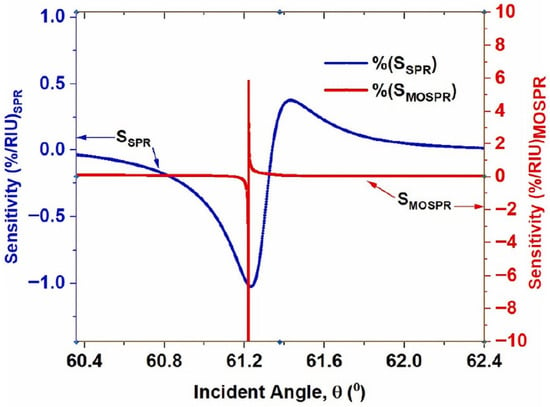

2.3. Sensitivity Comparison

Table 4 compiles benchmark sensitivities and detection limits for representative surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and magnetooptic—SPR architectures and highlights how material choice and nanoscale stacking govern performance across platforms [42,119]. Early bilayers such as Au/Fe/Au on Cr/glass establish a useful reference, showing magnetooptic SPR (MOSPR) signals roughly twice those of conventional SPR and a detection limit on the order of RIU [120], where RIU denotes refractive index unit.

Table 4.

SPR and MOSPR sensitivities and detection limits. Note RIU = Refractive Index Unit; SPR = Surface Plasmon Resonance. MOSPR = magnetooptic SPR. Adopted from [42].

Introducing protected Co layers in Au/Co/Au on Ti/glass yields a ∼ MO gain over SPR, together with improved signal-to-noise for biosensing [121]. Periodic Co/Au superlattices increase MO contrast and maintain practical detection limits through multilayer interference control, though with moderate absolute sensitivities that depend on the number of repeats and the environment (air vs. water) [123]. Symmetric magnetic stacks, such as Co/Au/Co in Kretschmann geometry, further enhance transverse MOKE (T-MOKE) without explicit detection-limit quantification [119].

Architectures that exploit localized plasmons, e.g., nanoporous Ag/CoFeB/Ag, demonstrate clear localized surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and localized surface plasmon resonance—molecular orbital (LSPR—MO) coupling with sensitivities in the mid- range and typical detection limits near RIU [124]. Flexible Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/Gold/CoFeB lattices provide ∼ enhancements of both LSPR and Kerr response via hotspot formation, illustrating the trade-off between mechanical compliance and the ultimate detection limit [125]. Lithographic Au/Co/Au nanodisks exhibit strong Kerr activity in the 2.2 to 2.5 eV window, which underscores the role of shape anisotropy and mode engineering [79].

Finally, trilayers such as Au/Fe/Ag in glass leverage low-loss Ag to boost the plasmonic field and deliver MO signals up to ∼ stronger than SPR [126]. Taken together, the literature points to a consistent trend: low-loss plasmonic metals (notably Ag), ultrathin ferromagnetic layers, and carefully tuned multilayer or nanostructured resonances systematically increase magnetooptic SPR (MOSPR) sensitivity while pushing detection limits toward the – RIU regime, providing a clear design map for next-generation magnetoplasmonic sensors.

3. Electromagnetic Theory and Modeling

Electromagnetic theory provides the fundamental framework for understanding the interaction of light with magnetized materials [46,127,128]. At its core, plasmonics investigates how electromagnetic waves couple with free electrons in metals, leading to collective oscillations known as surface plasmons [129]. When confined to metal—dielectric interfaces, these excitations, referred to as surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), exhibit strong sensitivity to changes in the surrounding dielectric environment. This property underpins a wide range of applications, spanning optical sensing, nanophotonics, energy-harvesting technologies, and beyond.

The phenomenon of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) arises when incident p-polarized light excites surface plasmons under specific resonance conditions, resulting in a characteristic dip in reflected intensity [119]. Such resonances, which are highly tunable by material and structural design, enable a wide range of applications, ranging from label-free biosensing and environmental monitoring to other sensing and photonic technologies [34,130].

Plasmon excitation also leads to pronounced field localization and enhancement, particularly in nanostructures or sharp metallic features [130]. These “hot spots” can amplify local electromagnetic fields by several orders of magnitude relative to the incident field, enabling phenomena such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) and single-molecule detection [131].

The integration of magnetooptical activity with plasmonics introduces an additional degree of freedom: external magnetic fields can modulate the dielectric tensor of a material, thereby tuning resonance conditions [101]. This magnetooptical modulation of SPR allows dynamic control of spectral properties, including the resonance angle, linewidth, and intensity, paving the way for advanced optical switches, modulators, and active sensing devices [132].

As discussed by Kittel and Yeh, the theoretical description of these interactions is rooted in Maxwell’s equations, augmented by appropriate constitutive relations to account for anisotropic, symmetry-dependent, and non-reciprocal material responses governing electromagnetic wave propagation in solids and layered media [133,134]. In magnetooptical systems, the dielectric becomes a tensor with off-diagonal elements that are directly linked to the magnetization. Linear magnetooptical effects, such as the Faraday and Kerr rotations, originate from these off-diagonal components and scale with the magnetization vector [1].

Higher-order effects, on the other hand, emerge from quadratic or more complex dependencies, introducing additional anisotropy and enhancing the sensitivity of detection techniques. To accurately model both linear and nonlinear responses, the full dielectric tensor, including its magnetic-field-dependent components, must be considered [135].

Several computational approaches have been developed to solve Maxwell’s equations under realistic material and boundary conditions [46,128,136,137]. The transfer matrix method (TMM) offers efficient analytical solutions for layered planar structures, while the finite element method (FEM) and finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) techniques provide versatile frameworks for simulating arbitrarily complex geometries and time-resolved dynamics.

These numerical methods are essential for predicting optical spectra, field distributions, and magnetooptical responses in nanostructured systems. They also guide experimental design by enabling the optimization of multilayer architectures, resonance conditions, and sensing performance before fabrication.

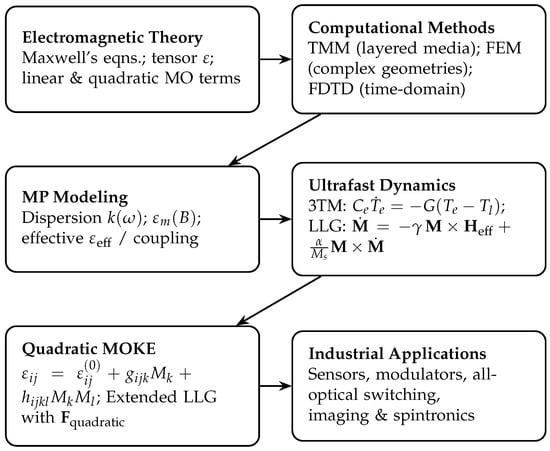

Figure 4 illustrates the conceptual framework, starting from electromagnetic theory and advancing through computational solvers, magnetoplasmonic modeling, and ultrafast spin dynamics (3TM/LLG), before extending to quadratic nonlinear MOKE and ultimately culminating in practical applications.

Figure 4.

Conceptual flow linking electromagnetic theory, computational solvers, magnetoplasmonic (MP) modeling, ultrafast spin dynamics described by the Three-Temperature Model (3TM) and the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) equation, and nonlinear quadratic MOKE, toward applications.

Having outlined the modeling framework, we now turn to the fundamental principles of plasmonics, which form the physical basis for many magnetoplasmonic phenomena. Plasmonics investigates the interaction between electromagnetic waves and free electrons in conductive materials, typically metals [129]. At optical frequencies, this interaction gives rise to surface plasmons, coherent oscillations of conduction electrons coupled to electromagnetic fields at metal-dielectric interfaces. These plasmonic modes are highly sensitive to changes in the local dielectric environment, making them foundational to optical sensing, nanophotonics, and photothermal applications [18].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) in a single metal-dielectric interface occurs when incident p-polarized light at a specific angle excites surface plasmons at that interface, leading to a characteristic dip in the reflected light intensity [119]. The resonance condition is achieved when the in-plane wavevector, of incident light matches that of the surface plasmon mode, which depends on the angular frequency (), the speed of light (c), and the dielectric constants of the metal () and dielectric (), as shown in Equation (4):

where represents the magnetically tuned dielectric constant of the metal. Such modulation forms the basis of magnetooptical sensors and switchable photonic devices.

This momentum-matching condition is highly sensitive to changes in the refractive index near the interface, enabling precise detection of molecular binding events. Due to this sensitivity, SPR has become a powerful and widely used technique for label-free biosensing, environmental monitoring, and real-time molecular interaction studies [119].

In contrast, multilayer SPR involves a stack of alternating metal () and dielectric () layers, where the plasmonic mode results from the hybridization of multiple metal—dielectric interfaces. The dispersion relation of these coupled surface modes, represented by the in-plane wavevector , is obtained by solving Maxwell’s boundary conditions across all layers using the transfer-matrix method [138]. This leads to more complex field distributions and , allowing for tunable mode coupling. Consequently, while single-layer SPR supports a single interface-bound mode , multilayer SPR enables mode splitting and enhanced field confinement through interference and coupling between adjacent plasmonic interfaces.

Although conventional plasmonic systems rely solely on material and structural properties to define their optical response, the introduction of an external magnetic field adds an additional degree of freedom, enabling active control over plasmonic behavior. In magnetoplasmonic systems, the application of an external magnetic field modulates the plasmonic resonance by altering the dielectric tensor of the material [37]. This tunability introduces anisotropy and enables active control of SPR characteristics, such as the resonance angle and linewidth [66,132].

Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) arises from the collective oscillation of conduction electrons confined to metallic nanostructures, such as nanoparticles, tips, or sharp edges [129,139,140,141]. Plasmon excitation leads to intense local electromagnetic field enhancement near the metal surface, producing nanoscale “hot spots.” The enhancement factor F is defined as

where is the peak local electric field amplitude, and is the incident field amplitude. These localized enhancements underpin phenomena such as surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), enabling single-molecule detection and ultrasensitive optical sensing [131].

Although magnetic fields can externally tune plasmonic resonances, an even more powerful approach arises from the intrinsic coupling between magnetic and plasmonic excitations, which gives rise to hybridized modes with enhanced tunability. The interaction between magnetic excitations and plasmonic modes produces hybrid resonances characterized by dynamically tunable optical responses. This coupling can be described through an effective permittivity formulation, as discussed in Section 4, Equation (17). Such interactions enable active control of resonance conditions, making hybrid magnetoplasmonic structures ideal for applications in active sensing, optical modulation, and integrated photonic systems [80,117,142,143].

To accurately capture and predict the complex behavior of hybrid magneto—plasmonic systems, it is essential to employ rigorous electromagnetic modeling based on Maxwell’s equations [133]. Such modeling requires a detailed treatment of light—matter interactions under the influence of external magnetic fields. These interactions, governed by Maxwell’s equations, are described through the dielectric tensor , which becomes anisotropic and non-reciprocal in the presence of magnetization. The general form of this tensor can be expressed as:

where the diagonal terms () represent the intrinsic permittivity along the principal axes, while the off-diagonal terms () describe the magnetooptical coupling induced by the magnetization vector . These off-diagonal components are typically antisymmetric () and proportional to the components of , i.e.,

where Q is the magneto–optical Voigt constant and is the Levi-Civita symbol. This formulation captures magnetooptical phenomena such as polarization rotation, circular birefringence, and non-reciprocal light propagation in magnetoplasmonic media [101].

Numerical simulations that incorporate the full magnetooptical dielectric tensor are essential for accurately predicting both the MO spectra (e.g., Kerr rotation and ellipticity) and the corresponding electromagnetic field distributions in complex nanoscale systems. These simulations, commonly implemented using finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) or finite element method (FEM) solvers, enable quantitatively reliable analysis of multilayers, metasurfaces, and resonant nano-architectures, where analytical or effective-medium approximations fail.

As summarized in Table 5, such modeling approaches play a critical role in optimizing sensor designs, interpreting experimental measurements, and guiding the development of new MO-active materials. Readers seeking a broader theoretical context and modeling framework are refereed to the magnetooptics Roadmap ([43], pp. 9–10) by de Sousa and García-Martín, where electromagnetic theory and numerical simulation methodologies for MO systems are discussed in detail.

Table 5.

Comparison of computational techniques used in magnetooptics modeling.

Accurate modeling also relies on computational methods capable of solving Maxwell’s equations under realistic boundary conditions. The Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) provides analytical solutions for layered media, making it well suited for planar multilayer structures. The Finite Element Method (FEM) offers high spatial accuracy for complex geometries by discretizing the system into meshes, while the Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) method simulates time-resolved electromagnetic fields in arbitrary nanostructures. These numerical tools are indispensable for predicting optical spectra, field distributions, and magnetooptical responses in device-scale architectures.

Beyond steady-state optical responses, modeling ultrafast magnetization dynamics is essential for understanding femtosecond spin—electron—lattice interactions. One widely used framework is the Three-Temperature Model (3TM) [144], which captures nonequilibrium energy transfer among three coupled subsystems: electrons, lattice, and phonons. The electron temperature evolves as:

where is the electron heat capacity and G is the electron—lattice coupling constant. The lattice temperature and the phonon temperature follow:

where and are the heat capacities of the lattice and the phonons, and is the relaxation time. This framework explains ultrafast demagnetization and recovery driven by femtosecond laser pulses. To capture vector magnetization dynamics, the Landau—Lifshitz—Gilbert (LLG) equation is employed [145]:

where is the gyromagnetic ratio, is the Gilbert damping coefficient, is the saturation magnetization, and is the effective magnetic field. The first term describes the precession of around , while the second term accounts for damping, driving the system toward equilibrium.

As presented in Equation (10), the Landau—Lifshitz—Gilbert equation (LLG) is widely used to model the dynamics of magnetization under the influence of external magnetic fields and ultrafast excitations [145]. This phenomenological framework describes both the precessional motion and the damping behavior of the magnetization vector in response to the effective magnetic field . These interactions arise from second-order contributions to the dielectric tensor and are expressed as:

where

- is the total permittivity tensor that describes the optical response of the material.

- is the permittivity tensor of the material in the absence of magnetization (i.e., the dielectric constant).

- is the first-order magnetooptical coefficient (a third-rank tensor), responsible for linear effects such as Faraday and Kerr rotation.

- is the second-order magnetooptical coefficient (a fourth-rank tensor) that accounts for quadratic coupling to magnetization.

- , are components of the magnetization vector . The term thus represents the quadratic magnetooptical coupling.

Incorporating this quadratic permittivity into a dynamical model introduces an additional torque in the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation (LLG) [145]:

where

- is the macroscopic magnetization vector.

- is the gyromagnetic ratio.

- is the effective magnetic field, which may include contributions from external, anisotropy, and exchange fields.

- is the Gilbert damping parameter.

- is the saturation magnetization.

- is the optically induced quadratic torque arising from the second-order term in permittivity.

This torque represents second-order optical driving forces that can trigger ultrafast magnetization switching and strong nonlinear magnetic responses. These quadratic contributions are fundamental mechanisms for all-optical magnetic switching and coherent control of spin states, offering promising pathways for the development of next-generation ultrafast spintronic memory and logic devices.

Although theoretical models such as 3TM provide valuable insights into the underlying spin—electron—lattice interactions, experimental validation is crucial for revealing their physical manifestations. Consequently, a range of experimental techniques has been developed to observe and quantify higher-order MO effects [105,135,146,147,148,149,150,151]. Quadratic MOKE, for example, is designed to be sensitive to the components of magnetization and has been applied effectively to antiferromagnetic (AFM) and ferrimagnetic materials. Table 6 provides a comparative summary of linear and quadratic magnetooptical (MO) effects, emphasizing their respective dependencies on magnetization, typical material classes, detection sensitivity, and spectroscopic characterization methods.

Table 6.

Comparison of linear and higher-order MO effects.

Theoretical modeling is crucial for quantitatively interpreting the observed magnetooptical responses. In Kerr microscopy, the modeling framework is derived from Maxwell’s equations in media with magnetooptical activity. In such materials, the propagation of electromagnetic waves is described by the vector wave equation, which incorporates the magnetization-dependent permittivity tensor [1,127,152]:

where is the electric—field vector, is the magnetization-dependent dielectric tensor and c is the speed of light in vacuum [1,147].

For a linear magneto—optical response (first order in ), the dielectric tensor can be written [1,127,147,152]

or, in matrix form,

where denotes the isotropic background permittivity, g is the magneto—optical (gyration) coefficient, is the Kronecker delta, is the Levi—Civita symbol (a fully antisymmetric tensor encoding the handedness of the coordinate system), and are the components of the magnetization vector . The off—diagonal terms of the permittivity tensor arise from this coupling between light and magnetization and are responsible for the observed Kerr and Faraday rotations [147].

To solve Equation (13) for realistic nanostructured materials, numerical simulation approaches such as the finite—difference time domain (FDTD) method and the finite element method (FEM) are commonly used [128,153]. These computational models provide predictive insight into the spatial and spectral distribution of the magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE) signals, supporting both the design and interpretation of experimental observations.

Beyond structural and optical modeling, the magnetooptical Kerr effect also serves as a powerful probe of spin-dependent phenomena, providing direct insight into the dynamic behavior of magnetization and spin—orbit interactions in magnetic materials. The magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE) is a powerful and widely used technique for investigating spin dynamics in magnetic materials, particularly in thin films and nanostructured systems [4,146,147].

When linearly polarized light reflects off a magnetized surface, interactions with spin-polarized electrons result in a modification of the polarization state of the reflected beam. This magnetization-dependent optical response gives rise to two measurable quantities: Kerr rotation (), which corresponds to the rotation of the plane of polarization, and Kerr ellipticity (), which quantifies the induced ellipticity of the reflected light [116,148,149]. These observables are intrinsically linked to the complex dielectric tensor of the material, especially the off-diagonal component , which encapsulates the optical anisotropy arising from magnetization and spin—orbit coupling. The complex Kerr angle is given by:

where and represent the diagonal elements of the tensor along the in-plane and out-of-plane directions, respectively, and is responsible for magnetooptically induced birefringence and dichroism [154,155].

The interaction of polarized light with the spin-dependent electronic band structure leads to polarization-dependent reflection coefficients, making MOKE particularly sensitive to magnetization orientation and magnitude. By analyzing and , researchers can monitor real-time magnetic switching, domain wall motion, and ultrafast spin reorientation processes [115,150,156]. Furthermore, the use of different MOKE geometries: longitudinal, transverse, and polar-allows selective sensitivity to magnetization components both in-plane and out-of-plane, reinforcing the status of MOKE as an indispensable tool in spintronics, magnetooptics, and ultrafast magnetism research [12,13,157].

To further complement these techniques, more sophisticated magnetooptical methods have been developed to probe complex dielectric responses and ultrafast spin dynamics. magnetooptical ellipsometry provides full complex tensor measurements and is capable of resolving subtle non-linear contributions that cannot be captured by traditional MOKE setups [103,158]. Nonlinear optical spectroscopy, particularly when employing ultrafast femtosecond laser pulses, enables the excitation and detection of magnetization dynamics beyond the linear regime. These methods have proven effective for probing spin reorientation transitions, magnetic phase boundaries, and the interplay between spin, charge, and lattice degrees of freedom in correlated systems.

4. Materials, Architectures, and Experimental Platforms

A wide range of materials, architectures, and experimental platforms forms the foundation of modern magnetooptical research. Among these, magnetooptics provides a unique tool for probing quantum materials, a class of substances with exotic electronic, magnetic, and optical properties [159]. These materials, which include topological insulators, Weyl semimetals, and quantum spin liquids, are distinguished by their non-trivial band structures and the intricate interplay of spin-orbit coupling and electronic correlations [160,161,162]. By leveraging the interaction between light and magnetic properties, magnetooptics enables researchers to probe the fundamental physics of these systems and explore their potential for next-generation technologies.

The same magnetooptical phenomena that provide deep insights into the physics of quantum materials are now being harnessed in applied contexts to engineer advanced photonic architectures. By translating fundamental principles of light—matter—spin interaction into functional device platforms, researchers have driven rapid progress in magnetoplasmonic and magnetophotonic sensor technologies, where the strategic combination of optical and magnetic components enables enhanced sensitivity, tunability, and multifunctionality.

Realizing these advances in practice requires careful material selection and structural engineering. In particular, the performance of magnetoplasmonic and magnetophotonic devices is strongly influenced by the choice and integration of plasmonic metals, ferromagnetic layers, and dielectric components that together determine the strength and tunability of optical and magnetooptical responses. Gold (Au) is widely used due to its chemical stability and efficient surface plasmon resonance (SPR) characteristics, whereas silver (Ag) offers superior field confinement but is limited by its susceptibility to oxidation and reduced durability. Ferromagnetic materials such as cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), and iron (Fe) are commonly incorporated to induce MO activity, particularly in Kerr and Faraday configurations.

To mitigate optical losses associated with metallic layers, modern sensor architectures integrate dielectric materials such as SiO2 and Si3N4, as well as high-index dielectrics, to support Mie-type resonances in all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces (ADMOMSs) [35,37]. These dielectric components improve light transmission, broaden spectral tunability, and enhance overall sensor stability. Furthermore, for enhanced chemical and biological selectivity, functional polymer layers, such as Nafion (for humidity detection) and Pb-phthalocyanine (for NO2 detection), are often applied to the sensor surface. The key materials employed in magnetoplasmonic sensor architectures, along with their functional roles, are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Materials commonly used in magnetoplasmonic sensors and their functional roles. ADMOMS = all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces.

The performance of magnetoplasmonic platforms is strongly affected by the intrinsic magneton damping (Gilbert) of the magnetic constituent. High damping in common ferromagnets such as Ni, Fe, and Co accelerates magnetization relaxation, broadens magneto—optical (MO) resonance linewidths, reduces coherence, and, thereby, degrades the signal-to-noise ratio and sensing stability. Consequently, there is a clear motivation to identify and integrate magnetic media with low damping constants, as reduced damping improves the quality factor of spin dynamics and sharpens MO spectra, which can translate into higher phase and intensity sensitivity in plasmon-enhanced transduction [145].

Ongoing research explores several material families that balance low damping with optical and nanofabrication compatibility: ferrimagnetic oxides (e.g., YIG) exhibiting ultra-low damping (down to ) yet requiring epitaxial growth and careful integration with noble metals; metallic ferromagnet alloys (e.g., CoFe, FeCoB) that offer damping lower than pure 3d ferromagnets, with CMOS-process compatibility but introduce additional optical loss; and emerging organic ferrimagnets such as V[TCNE]x that display low-loss spin dynamics in thin films while posing challenges in long-term chemical stability and heterogeneous integration [164]. Table 8 summarizes these classes, outlining representative examples along with the advantages and known limitations relevant to the engineering of magnetoplasmonic devices.

Table 8.

Comparative overview of magnetic and hybrid materials for magnetoplasmonics, including conventional ferromagnets, low-damping candidates, and emerging transparent conductive oxides (TCOs). ADMOMS = all-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces.

Transparent conductive oxides (TCOs), including ZnO, indium tin oxide (ITO), and copper chalcogenides such as Se, are attracting growing attention as alternatives to conventional noble metals for magnetoplasmonic architectures [45]. Their tunable carrier density over a broad spectral range, combined with the ability to support localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs), provides a versatile means of enhancing magnetooptical modulation. Recent studies have shown that co-doping TCOs with paramagnetic ions can further tailor both carrier concentration and magnetic response, thereby enabling hybrid material platforms with enhanced functionality. Importantly, Gabbani et al. [45] demonstrated that the magnetoplasmonic response of doped TCO nanocrystals can surpass that of conventional Ag or Au nanostructures by nearly an order of magnitude, underscoring their potential to reshape the materials landscape in this field. While stability, reproducibility, and integration challenges remain, TCOs represent a highly promising class of materials that could significantly broaden the design space for next-generation magnetoplasmonic devices.

The presence of an external magnetic field, , applied via a circular magnet surrounding the sample, induces a magnetooptic response by modulating the plasmonic dispersion relation. This -dependent modulation enables real-time detection of changes due to analyte interaction, improving the sensor sensitivity to gasses, humidity, or biological media. The resonance condition for surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is determined by the relation given in Equation (4) [129].

Recent advances in magnetoplasmonic sensing have highlighted the importance of accurately modeling the effective permittivity () to describe the intricate coupling between surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), localized surface plasmons (LSPs), and magnetooptical effects such as Kerr rotation [4,138,165]. To capture this coupling in a simplified form, effective permittivity can be phenomenologically expressed as follows:

where is the magnetization of the magnetic medium, is the externally applied magnetic field, represents the background (non-magnetic) permittivity, and denotes the intrinsic dielectric constant of the plasmonic material. This simplified expression does not constitute a rigorous microscopic derivation; instead, it serves as a phenomenological model to illustrate how variations in magnetization and magnetic field strength influence the effective dielectric response of the hybrid system. It emphasizes the field- and -dependent tunability of magnetoplasmonic interactions, which is key to optimizing device sensitivity and performance in advanced sensing architectures.

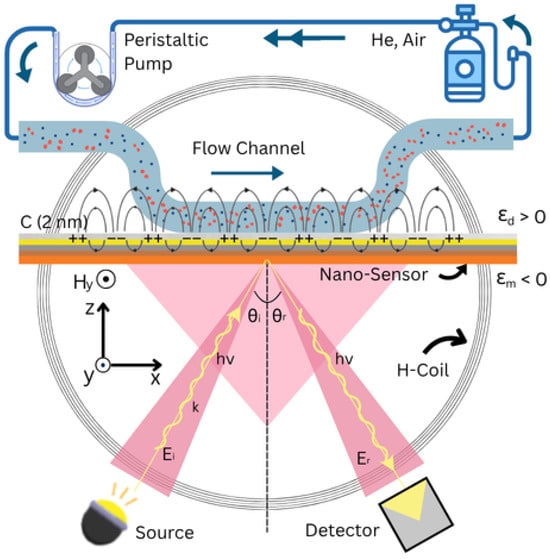

Figure 5 shows a typical experimental setup based on the Kretschmann configuration, which is used to characterize and measure the probing sample [42]. The system integrates a peristaltic pump, an electromagnetic coil, and an angle-resolved detection unit. In this setup, a laser beam is directed through a refractive index, n, of the BK-7 prism to achieve total internal reflection at the metal-dielectric interface, generating evanescent waves that excite surface plasmons [119]. A thin metal layer (e.g., Au or Ag) is coated with magnetic and dielectric films that support the SPR condition.

Figure 5.

Schematic of an excitation platform incorporating an electromagnetic coil, peristaltic pump, light input, and angle-resolved detection system. Adopted from C. Rizal and S. Malla, “Optimized magnetooptic multilayer structures for enhanced surface plasmon resonance detection,” Journal of Applied Physics 138, 074901 (2025), published by AIP Publishing under a Creative Commons CC BY license [42].

5. Characterization and Imaging Techniques

Understanding the spatial organization, temporal evolution, and nanoscale behavior of magnetic materials requires direct access to their underlying spin configurations and domain structures. Thus, magnetic imaging has become a central tool in contemporary magnetism research, providing the critical link between theoretical predictions and experimentally observed phenomena [30,150]. By enabling direct visualization of domain patterns, spin textures, topological defects, and dynamical processes, these techniques offer essential insights into the mechanisms governing magnetization behavior and device performance.

Over recent decades, major advances in magnetooptical techniques, electron microscopy, X-ray imaging, and scanning probe methods have broadened the spatial and temporal regimes accessible for magnetic characterization. Modern imaging approaches now allow not only the observation of static magnetic configurations but also the tracking of ultrafast spin dynamics, three-dimensional magnetization textures, and the behavior of individual skyrmions or propagating spin waves [109]. These capabilities are shaping the development of next-generation spintronic devices, magnetic data storage systems, and quantum magnetic platforms.

Within this progress, magnetooptical imaging has emerged as a particularly powerful approach due to its noninvasive nature, compatibility with device geometries, and ability to capture dynamic processes with high temporal resolution. Improvements in spatial resolution and light—matter interaction sensitivity have made it possible to probe emergent magnetic states and ultrafast magnetization responses relevant to both fundamental research and applied material design.

Among these approaches, advanced implementations of the magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE), Brillouin light scattering (BLS) microscopy, and near-field scanning optical microscopy (NSOM) have become widely adopted for probing spin-wave excitations, nanoscale magnetic textures, and domain evolution [166,167,168]. These techniques provide complementary access to static and dynamic aspects of magnetization, enabling the visualization of domain structures, the mapping of magnon dispersion, and the resolution of sub-diffraction magnetic features. Despite these advances, ongoing challenges remain, including improving signal—to—noise ratios, increasing compatibility with device-scale architectures, and developing scalable imaging strategies suitable for integrated magnetic platforms [90].

The following subsections examine each technique in detail, emphasizing the underlying contrast mechanisms: magnetooptical rotation, spin-wave scattering, near-field optical confinement, and polarization-dependent absorption, that govern measurement sensitivity and guide the design of next-generation, high-resolution magnetic imaging tools.

5.1. Magnetooptical Kerr Effect (MOKE) Microscopy

Magnetic imaging techniques provide direct access to the spatial distribution and temporal evolution of magnetization by probing the interaction between magnetic materials and external signals such as light or X-rays. Among optical approaches, the magnetooptical Kerr effect (MOKE) is one of the most widely used methods. In MOKE-based imaging, the polarization of reflected light is rotated by an amount proportional to the magnetization of the material:

enabling sensitive and quantitative visualization of magnetic domain patterns and real-time switching processes, particularly in thin films and nanostructured systems. The contrast originates in the magnetization-induced off-diagonal elements of the dielectric tensor. The complex Kerr angle (rotation and ellipticity ) is [155,156,169,170]:

where and are Fresnel reflection coefficients. In a gyrotropic medium the permittivity can be written

and an effective-index form emphasizes optical-constant dependence [1]:

Under an applied magnetic field H, a convenient empirical magnetization model for reversal is [100,171]:

with the saturation magnetization and the coercive field, capturing the switching and domain evolution seen in Kerr loops.

Experimentally, a linearly polarized laser, a high-NA objective, and polarization analysis upon reflection (analyzer + CCD/photodiode) are used, often with lock-in detection for weak Kerr signals [147,171,172]. The diffraction-limited lateral resolution obeys

where is the wavelength and NA is the numerical aperture [127]. Geometry determines vector sensitivity: longitudinal (in-plane, parallel to the plane of incidence), transverse (in-plane, perpendicular), and polar (out-of-plane) [1,147,171,172,173].

Recent advances include magnetization noise spectroscopy in artificial spin systems [174,175], super-Nyquist sampling MOKE for broadband spin dynamics [176], and femtosecond time-resolved Kerr microscopy for ultrafast demagnetization, spin precession, and reversal pathways ([43], pp. 7–8). These developments position MOKE microscopy as a versatile, device-compatible platform for real-time studies of domains, DW dynamics, and spin—orbit torque phenomena.

5.2. Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS) Microscopy

To probe the dynamic properties of magnetization beyond static domains, Brillouin Light Scattering (BLS) microscopy measures the frequency shift of light inelastically scattered by spin waves (magnons) [177]. The sampled dispersion can be expressed as

with the spin-wave frequency, the gyromagnetic ratio, the magnon wave vector, and the magnetization. In the provided formulation, a practical working relation connecting the observed shift and magnon kinematics is

where is a characteristic magnon velocity and is the probe-light wavelength [178,179]. Micro-focused BLS (-BLS) achieves lateral resolution ∼200–300 nm (optical focusing limited) while delivering energy resolution down to a few MHz (eV), enabling access to nanometric-wavelength magnons in reciprocal space () even when real-space features are below the optical limit. BLS quantifies magnon propagation, nonreciprocal transport (e.g., DMI-induced asymmetries), nonlinear magnon—magnon scattering, relaxation, coherence, and skyrmion dynamics [180].

Technological advances have enhanced frequency-resolved imaging and polarization sensitivity, boosting the detectability of weak magnon populations [181]. Typical limitations include weak inelastic cross-sections and longer acquisition times [168].

5.3. Near-Field Scanning Optical Microscopy (NSOM)

For nanoscale magnetic structures that lie below the optical diffraction limit, NSOM confines light through a nanoscale aperture positioned in the near field. The spatial resolution is determined by aperture size a [182]:

enabling nanometer-scale mapping of domain walls, vortices, and skyrmions [109,115]. Near-field throughput scales approximately as , which motivates plasmonic concentration; a useful enhancement scaling is [129,131]:

with d the probe—sample distance and n geometry dependent. NSOM enables studies of magnetoplasmonics and nanoscale device concepts [80,117], but it requires precise alignment and mitigation of tip-induced artefacts [127,152,183]. Recent advances include plasmonic antennas, optimized probe designs, and adaptive feedback scanning that improve SNR and robustness [35,184,185,186], advancing spintronic device metrology and high-density magnetic storage studies [12,13,16,43].

5.4. Magnetooptical Microscopy

A complementary far-field approach is magnetooptical microscopy, which uses polarization-sensitive optics to convert Kerr rotation into intensity contrast. The detected intensity I varies with the analyzer angle and Kerr rotation as

enabling real-time monitoring of domain nucleation, domain-wall motion, and magnetization reversal under fields or currents. This technique offers device-compatible imaging with video-rate feedback and spatial resolution set by Equation (23) [127].

5.5. X-Ray Magnetic Circular Dichroism

X-Ray Magnetic Circular Dichroism (XMCD) provides element-specific magnetic contrast by measuring the absorption difference between opposite X-ray helicities:

where and are the right-/left-circular absorption coefficients. By tuning in to core-level edges, XMCD isolates the spin and orbital contributions of specific elements. In combination with STXM or PEEM, XMCD enables element-resolved nanoscale imaging (∼10–50 nm) of multilayers and interfaces central to spin—orbitronics [187].

5.6. Spectroscopic Magnetooptical Characterization

Building on the magnetooptical techniques discussed above, spectroscopic implementations enable wavelength-resolved probing of electronic structure, magnetic anisotropy, and spin dynamics [43,105,146,147,148,149,157]. The underlying magnetooptical phenomena governing these spectroscopic responses were introduced earlier in Section 2 and summarized in Figure 3, which provides a unifying framework for interpreting the wavelength-dependent effects examined in this section. In transmission, Faraday rotation for transparent media is

with Verdet constant V, magnetic flux density B, and optical path L [3,43,147]. Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) measures differential absorption for circular polarizations,

and is sensitive to spin—orbit coupling, spin polarization, and the local chemical environment [1,16,50], supporting studies of molecular magnets, chiral systems, and topological semimetals [68,188,189,190]. In reflection, MOKE spectroscopy (longitudinal, transverse, polar) remains central for thin films and surface magnetism, with the complex-angle formalism consistent with Equation (19) and geometry selecting the probed magnetization component [4,14,146,148,149]. Table 9 compares widely used spectroscopic magnetooptical techniques, emphasizing their practical capabilities, limitations, and performance metrics.

Table 9.

Comparison of key spectroscopic magnetooptical techniques.

5.7. Comparison of Advanced Magnetic Imaging Techniques

The complementary strengths and limitations of the above methods are summarized in Table 10, emphasizing spatial/temporal resolution, applications, and practical constraints. NSOM surpasses far-field MCD/MOKE/BLS in real-space spatial resolution by breaking the diffraction limit and directly resolving nanoscale textures that other techniques can only infer indirectly [12,13,109,115,127,152].

Table 10.

Comparison of advanced magnetic imaging techniques, summarizing spatial resolution, typical applications, and primary limitations. BLS = Brillouin Light Scattering, NSOM = Near-field Scanning Optical Microscopy, MOKE = magnetooptical Kerr Effect, XMCD = X-ray Magnetic Circular Dichroism.

5.8. Concluding Perspective

Taken together, these imaging techniques offer complementary perspectives on magnetic systems, from domain-scale magnetization patterns (MOKE, magnetooptical microscopy) to dynamic spin-wave phenomena (BLS), element-resolved nanoscale behavior (XMCD), and sub-diffraction real-space textures (NSOM). Spectroscopic implementations (Faraday, MCD, MOKE) and ultrafast frameworks (3TM, LLG) enrich temporal, spectral, and microscopic interpretability [21,54,105,144,145,157,194] and ([43], pp. 11–12). Their combined use enables comprehensive, multi-scale characterization that supports advances in spintronics [11,12], quantum information processing [17,195], and broader materials science [8,43].

6. Emerging Architectures and Future Directions in Applications

6.1. Ferromagnetic—Nonmagnetic Configuration-Based Magnetoplasmonic Configurations

Magnetoplasmonics is an interdisciplinary field that integrates magnetic and plasmonic materials to enhance and control light—matter interactions at the nanoscale [32,33]. In multilayer magnetoplasmonic architectures, such as metal/ferromagnet/metal (M/FM/M) or dielectric/metal/ferromagnet stacks, the key optical response arises from propagating surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) supported at extended planar interfaces.

The underlying physics of SPP excitation and dispersion in layered thin films has already been discussed in Section 3; therefore, here we emphasize their magnetoplasmonic role. Embedding a ferromagnetic layer within an SPP-supporting multilayer enables magnetic control of the plasmon resonance, producing tunable reflectivity, polarization modulation, and magnetooptical signal enhancement through the coupling between plasmonic mode confinement and the magnetic permeability of the ferromagnetic layer [117,132]. These multilayer-based SPP configurations are particularly attractive for device-compatible platforms because they allow long-range propagation, on-chip integration, and field-tunable responses suitable for waveguide modulators and plasmonic readout architectures.

In contrast to multilayer SPP systems, magnetoplasmonic nanostructures based on localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPR) rely on the collective oscillation of conduction electrons confined within metallic nanoparticles or nanostructured arrays [129,131,196]. When illuminated, the localized plasmon mode produces a strong nanoscale electromagnetic near-field enhancement, significantly amplifying the optical response of adjacent magnetic materials. The magnetooptical contribution, originating from ferromagnetic elements such as Co, Fe, or Ni, modulates the polarization or amplitude of the scattered or transmitted light under applied magnetic fields [1,83,117]. The interplay between field localization and magnetic birefringence leads to a resonance-enhanced magnetooptical response, commonly observed as a change in reflectivity:

where and represent the reflectivity in the magnetized and demagnetized states, respectively. This enhancement is maximized at the LSPR wavelength due to the intensified local electromagnetic fields concentrated at the nanoparticle surface [39,143]. As a result, LSPR-based magnetoplasmonic systems enable strong, tunable magnetooptical effects and are central to applications in ultrafast optical switching, polarization control, and high-sensitivity biosensing.

Realizing functional magnetoplasmonic structures requires advanced nanofabrication techniques capable of producing well-defined and reproducible nanoscale architectures. Electron beam lithography (EBL) remains the standard method for patterning nanostructures with dimensions of up to a few tens of nanometers, offering excellent resolution and flexibility in design [26]. For scalable and cost-effective production, nanoimprint lithography (NIL) is increasingly employed to replicate nanoscale patterns over large areas [26]. Additionally, physical vapor deposition (PVD) techniques, including sputtering and thermal evaporation, are routinely used to fabricate thin-film multilayers combining magnetic and plasmonic materials [120,121]. Chemical synthesis offers another route for the production of colloidal hybrid nanoparticles, allowing the integration of magnetic cores and plasmonic shells within a single nanostructure through wet chemical processes [45,124]. These fabrication strategies enable precise control over geometry, composition, and interfacial quality, key factors that dictate the performance of magnetoplasmonic devices [34,80,184].

The structural diversity of magnetoplasmonic platforms supports a wide range of functionalities. A prominent architecture is the core—shell nanoparticle, where a ferromagnetic core (such as cobalt or iron) is encapsulated by a plasmonic shell (typically gold), providing tunable LSPR and an enhanced MO response in a single entity. Another widely adopted configuration involves plasmonic nanoantennas, such as nanodisks or nanorods, which exhibit shape- and size-dependent resonance characteristics and serve as optical modulators in sensing and communication devices. Dielectric metasurfaces, which integrate magnetic and dielectric components, have also emerged as promising alternatives, offering enhanced MO effects while mitigating optical losses typically associated with metallic systems.

One of the key achievements in magnetoplasmonics is the plasmonic amplification of MO effects. This enhancement is often evaluated using a figure of merit (FOM), defined as , where is the full-width at half-maximum of the resonance peak [66]. A high FOM indicates sharper resonances and a stronger MO response, making such systems attractive for applications in biosensing and environmental monitoring. In addition to static enhancement, ultrafast magnetoplasmonics leverages femtosecond laser pulses to probe spin and charge carrier dynamics at sub-picosecond timescales. This allows for the observation of ultrafast demagnetization, spin precession, and all-optical switching, thereby facilitating the development of high-speed optoelectronic and spintronic devices.

Recent investigations have also focused on nonlinear magnetoplasmonics, where second-order and higher-order optical processes such as second-harmonic generation (SHG) and four-wave mixing (FWM) are utilized to control magnetization and light propagation at low power thresholds. These nonlinear effects open new possibilities for coherent control, quantum state manipulation, and low-energy photonic computing.

A comparative evaluation of plasmonic and magnetoplasmonic systems reveals several key differences, as summarized in Table 11. Although both platforms leverage strong LSPR, magnetoplasmonic systems provide the added benefit of MO coupling, leading to greater functionality in areas such as data storage, light modulation, and active sensing. However, these enhancements often come at the cost of added complexity in integration and susceptibility to thermal effects. Emerging trends in pure plasmonics focus on dielectric and actively tunable materials, whereas magnetoplasmonics is evolving towards hybrid metasurfaces and the incorporation of quantum technologies for next-generation opto-magnetic platforms.

Table 11.

Comparison of plasmonic and magnetoplasmonic systems.

Magnetoplasmonics continues to bridge nanophotonics, magnetism, and materials science, offering new paradigms for controlling light and spin at the nanoscale [32,33]. As fabrication technologies mature and theoretical models evolve, the path to practical applications in quantum information processing, biomedical diagnostics, and compact magnetic sensors becomes increasingly viable. The combination of strong optical confinement with magnetic tunability presents a compelling platform for the future of multifunctional photonic and spintronic systems.

The future of magnetoplasmonics lies in its convergence with quantum optics, AI-enhanced design, and bio-integrated platforms [185]. As fabrication tools and simulation capabilities mature, magnetoplasmonic systems are poised to drive next-generation sensing, logic, and energy-efficient photonic circuits ([43], pp. 32–34).

6.2. All-Dielectric Magnetooptical Metasurfaces

All-dielectric magnetooptical metasurfaces (ADMOMSs) represent a rapidly advancing frontier in nanophotonics, offering a low-loss, highly tunable alternative to conventional plasmonic architectures [35,36,37]. Their functionality arises from the intrinsic properties of dielectric materials, which are capable of supporting both electric and magnetic Mie resonances. Unlike plasmonic metasurfaces, which rely on the excitation of surface plasmon resonances (SPRs) and often suffer from high optical losses due to free-carrier absorption in metals, ADMOMSs exhibit significantly reduced dissipation. This enables more efficient light—matter interactions, enhanced magnetooptical activity, and improved compatibility with integrated photonic platforms, paving the way for next-generation non-reciprocal devices and on-chip magneto-photonic technologies.

These dielectric metasurfaces are distinguished by their high transparency and minimal absorption losses across the visible and near-infrared spectral regimes. Commonly used materials, such as silicon and titanium dioxide, provide excellent platforms for metasurface engineering due to their favorable refractive indices and low-loss characteristics. Importantly, ADMOMSs support high-quality factor resonances, which enhance light—matter interactions and enable precise control of the magnetooptical behavior that is governed by the dielectric tensor , which takes the form as [155]; see Figure 3. The ability of ADMOMSs to tightly confine light in subwavelength dielectric resonators amplifies these magnetooptical effects, allowing for efficient modulation of polarization, phase, and intensity.

In comparison to plasmonic systems, ADMOMSs offer several critical advantages. First, they exhibit significantly lower optical losses due to the absence of conduction electrons, which mitigates absorption and heating issues [35,132,201]. Second, their sharp Mie resonances contribute to higher quality factors (Q), enhancing sensitivity and spectral resolution in magnetooptical applications [35,36,202]. Third, dielectric materials are generally abundant and cost-effective, improving the scalability and manufacturability of all-dielectric metasurfaces and photonic devices for real-world applications [17,132,195].

The fabrication of all-dielectric magnetooptic metasurfaces (ADMOMSs) leverages state-of-the-art nanofabrication techniques [35]. Electron beam lithography (EBL) provides high-resolution patterning capabilities to define subwavelength dielectric features with nanometric precision [185]. Reactive ion etching (RIE) is employed to carve these features into high-index materials like silicon or gallium arsenide [201]. Nanoimprint lithography enables large-scale, low-cost replication of the dielectric metasurface, while atomic layer deposition (ALD) ensures uniform conformal coating of ultrathin films with precise thickness control, crucial for tuning optical and magnetooptical properties at the nanoscale [36].

A side-by-side comparison of plasmonic and all-dielectric metasurfaces is provided in Table 12, highlighting differences in optical loss characteristics, resonance types, quality factors, application domains, and scalability. This comparison illustrates the distinct advantages of ADMOMSs for future optical and magnetooptical technologies that require low-loss, tunable, and scalable platforms.

Table 12.

Comparison of plasmonic and all-dielectric metasurfaces.

6.3. THz Magnetooptics and Ellipsometry

The terahertz (THz) frequency range, which spans from 0.1 to 10 THz, occupies a unique position in the electromagnetic spectrum, bridging the gap between microwave and infrared frequencies [204]. Berger et al. discuss the application of generalized magnetooptical ellipsometry to characterize materials, demonstrating how magnetooptical effects in the terahertz regime can be quantitatively linked to both optical and magnetic response functions [103]. This region has gained significant attention in recent years for its powerful capabilities in magnetooptics [205], particularly in probing low-energy excitations such as magnons, phonons, and spin waves in quantum and correlated materials. THz magnetooptics and ellipsometry provide deep insights into ultrafast spin, charge, and lattice dynamics, which are critical for understanding fundamental physical phenomena and advancing next-generation technologies.

The principles of THz magnetooptics revolve around the interaction between THz electromagnetic waves and magnetized materials. This interaction manifests primarily through two phenomena: the Faraday effect, characterized by the rotation of the polarization plane as THz radiation propagates through a magnetized medium, and the Kerr effect, observed as a change in the polarization state of light upon reflection from magnetized surfaces [206]. These effects are governed by the dielectric tensor () and are expressed as [1,147,207]:

where represents the angular frequency of the THz radiation, and characterizes the magnetooptical coupling. The capability of THz waves to probe low-energy quasiparticles enables detailed investigations into spin-lattice coupling, phase transitions, and dynamic processes in a non-invasive manner [1,147].

THz ellipsometry, an extension of traditional optical ellipsometry into the terahertz regime, is a non-destructive method for analyzing changes in the polarization state of reflected or transmitted light [103,205,208]. It provides broadband spectral coverage, making it ideal for investigating a wide array of excitations while also preserving the integrity of thin films and delicate samples. The ellipsometric parameters and are extracted using the relationship [103]:

where and are the Fresnel reflection coefficients for p- and s-polarized light, respectively. It offers high precision in determining the dielectric tensor elements and is particularly sensitive to both the magnetic and electronic properties of materials [206].