Abstract

The uneven distribution of flow in water distribution networks (WDNs) can cause inefficient flows and pressure imbalances as well as degraded water quality in areas where demand is higher than the networks’ design limit. In this study, two faulty connections within a WDN in Greece that exhibited unusual geometric shapes favoring preferential flow paths were investigated. The three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics simulations were performed in ANSYS Fluent solver (v. 23.1) to study the internal behavior of this network for steady-state flows. The standard k-ε model was employed to calculate turbulence and energy losses in this network. In Connection A, which is a cross-shaped junction with two inlets and two outlets, and in Connection B, which is a complex 4 → 1 → 4 manifold connection, more than 80% of total inflow was found to be directed to a single outlet. The pressure contour plots revealed that this is due to the large total head losses associated with pronounced changes in flow direction. The role of explicit junction losses in network modeling and network improvements to improve hydraulic behavior has thereby gained prominence through this study. The applicability and capability of computational fluid dynamics in characterizing complex flow problems in urban WDNs have thereby proven to be significant.

1. Introduction

Water distribution networks (WDNs) are distribution systems developed to deliver drinking water of satisfactory quality and quantity to consumers [1,2]. They consist of interconnected pipelines, pumps, distribution tanks, and valves, all designed to serve spatially distributed demands and ensure reliability under dynamic circumstances [3,4]. Adequate hydraulic design and operation of WDNs are required to avoid issues such as dead ends or zones of low pressure, inadequate fire hydrant flow, and degradation of water quality [3,5,6]. However, aging pipes, suboptimal pipeline layouts, and incorrect layouts of connections may induce inefficient or non-uniform distribution of flow in the network [7,8]. Much of the supplied water is lost or unaccounted for in the vast majority of urban centers due to leaks and inefficiencies—values of 30% and above have been reported [9,10,11,12]. These losses not only deplete valuable water supplies but also redistribute flow patterns throughout the network, intensifying distribution imbalances and operational costs [13,14].

Recent research has highlighted that flow and mixing in pipe junctions can be far from ideal. Studies of cross-type junctions (four-way crosses) have demonstrated that multiple inflows do not always mix uniformly; instead, momentum can cause stratification or preferential paths for different streams [15,16]. Ho and O’Rear [15], for example, showed through experiments that impinging flows in a cross-junction often bifurcate and “slide” past each other with incomplete mixing, contrary to the common assumption of instantaneous perfect mixing in network models. These findings spurred the development of improved water quality models accounting for incomplete mixing [15,17,18]. While those studies focused on water quality implications, they underscore that junction hydraulics are complex and can lead to uneven flow splits. In fact, Ho and O’Rear [15] noted that about 75–80% of modern pipe intersections in distribution grids utilize four-way cross-junctions (because of cost and ease of installation), rather than constructing two separate T-connections (double-T), potentially exacerbating mixing and distribution issues. The geometric configuration of a junction—including the alignment of the pipes, the branching angles, and the diameter ratios—plays a pivotal role in how flow is partitioned [19,20]. Unequal resistances of friction and tight turns cause maldistribution of flow, i.e., too-low flow in one branch relative to the remainder of the branches [19]. For manifold systems and parallel pipe configurations, it is well documented that minute dissimilarities of branch resistance or inlet shape cause flow asymmetry [19]. Correspondingly, for WDNs, an improperly shaped junction would, by analogy, be equivalent to a manifold favoring or predominantly feeding one direction of flow to the detriment of the remainder.

Another frequent WDN constituent is the T-junction, where the main pipe proceeds straight and the branch pipe T-junctions off, typically at 90°. T-junctions are common fare for distribution networks and are related to extensive head losses and flow separation characteristics [21,22]. At a diverging T-junction, the straight-through path would generally have lower resistance (only a gradual area or direction of flow change) than the side branch, which would require the fluid to make a 90° angle turn, typically into the branch pipe. Most of the flow would hence proceed straight and only a minority would turn into the branch [21]. Experimental and numerical investigations of isolated T-junctions have modeled this behavior [23,24,25]. Pal et al. [26] and Costa et al. [27] investigated turbulent flow through the 90° T-junction of equal diameter pipes: they noted substantial pressure losses along the junction and discovered rounding off the sharp corners of the junction to be able to mitigate losses and, actually, enhance the flow split through the branch. In the sharp-edged T-junction, the recirculation zone would generally develop just downstream of the branch entrance, reducing the branch’s intake area [27,28].

While most previous works have examined idealized confluences under laboratory conditions, real-world network configurations—characterized by multiple junctions in close proximity and asymmetric boundary conditions—remain under-explored. Field measurements frequently indicate network underperformance that network models fail to describe. For example, some neighborhoods may suffer chronically low flow/pressure not because of undersized pipes or overwhelmingly high demand but because of an upstream junction diverting most of the water towards a certain direction.

Two pipeline connections located in the WDN of the city of Patras (Greece) have demonstrated non-uniform flow distribution. At those connections, the water can proceed towards three alternative outlets, but field reports confirm that the bulk of the flow prefers the straight path of lowest turns and leaves the rest of the branches with significantly lower discharge. These connections are, to some extent, peculiar both in layout and not optimally designed, so they are vulnerable to the aforementioned imbalance. Effectively, one branch remains almost starved of water under nominal operation, which results in poor availability of the area it supplies and undesirable water age (stagnation) of the respective branch. The low-flow nodes of WDNs are susceptible to chlorine residual loss, bacterial growth, and settling of suspended sediments due to the longer residence times [29]. Therefore, correction of the hydraulic imbalances has crucial importance not only for distributional fairness but also for the quality characteristics of the water.

To rigorously analyze the flow behavior at these problematic connections, we employ high-fidelity computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations. CFD allows for capturing the detailed three-dimensional flow patterns, pressure distributions, and turbulence effects that simpler one-dimensional models cannot represent [30]. In recent years, CFD has been increasingly applied to water distribution problems on a component level—for example, to simulate flow through ancient conical pipes, to study transient cavitation and leaks in pipes [31], and to investigate mixing in reservoirs and tanks. In the context of pipeline junctions, CFD provides a way to visualize recirculation zones and quantify head losses with high resolution [21,28].

The current research aims to comprehend and remedy flow maldistribution through two given pipeline connections using ANSYS Fluent solver [32]. First, we construct precise 3D models of the pipe connections according to the real configuration geometry and field measurements. Flow analyses are conducted under representative peak demands to assess the distribution of water between the accessible downstream branches.

While there are relevant studies on junction losses and the related issue of flow behavior using either one-dimensional networks or simplified experiments and simulations, the effect of three-dimensional geometries on local-scale hydraulics related to junction types and pressure regulation in real-world network configurations remains insufficiently documented.

This work focuses particularly on the characteristics of turbulence and energy loss throughout the connections, applying the standard k-ε model for turbulence closure [30], which has been proven useful for internal flow and popular for pipe flow applications [22,33]. Through the results, the level of the imbalance (answering the quantitative question of what percentage of flow enters each of the branches) and the reasons behind the imbalance (pressure and velocity distributions) are revealed. By resolving these localized problems, the efficiency and hydraulic resilience of the entire network can be improved [7]. The conclusions are applicable to any water network and pipeline junctions suffering similar flow distribution difficulties due to poor connections.

2. Case Studies Description

This study focuses on two particular pipeline connections located in the municipal WDN of the city of Patras (Greece). These pipeline junctions are referred to as Connection A and Connection B, for brevity. They are both network nodes where the main intersects second-order pipelines, distributing flow in several directions. These connections were cited by the engineers of the Municipal Enterprise of Water Supply and Sewerage of Patras (MEWSSP) as problematic, where they observed an imbalance of flow distribution under normal operational conditions. Through field measurements and data acquired by means of the SCADA system, it became evident that the straight-through outlet pipe of the respective stations always carried most of the flow, while the rest of the pipes, serving neighboring zones, carried much lower flow rates, leading to consumer complaint reports.

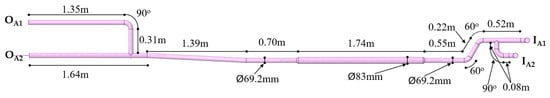

Connection A (Figure 1 and Figure 2) is situated in the urban core of the city and comprises two high-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipes, each with an inner diameter of 69.2 mm, that merge into a single pipe with an inner diameter that varies from 69.2 mm to 83.0 mm. The latter pipe branches into two pipelines, each with a diameter of 69.2 mm, one of which continues along the main pipeline route (69.2 mm). This configuration effectively creates a cross-junction characterized by two outgoing pipes: one constitutes the direct continuation of the main line (69.2 → 69.2 mm straight run), while the other serves as a lateral branch (extending to the left of the main line). The angle at which the lateral branch of Connection A diverges is approximately 90° relative to the direction of the main line (thus forming a T-junction configuration). In the present real arrangement, there is an absence of any specialized flow restriction or guiding device within the junction—it functions fundamentally as a standard cross fitting.

Figure 1.

On-site photograph of Connection A: two HDPE pipes merge into a single pipe (with a diameter that varies from 69.2 mm to 83.0 mm), which then branches into two pipelines, one of which continues along the main pipeline route (right pipe in the photograph).

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of Connection A: two pipes merge into a single pipe (with an inner diameter that varies from 69.2 mm to 83.0 mm), which then branches into two pipelines, one of which continues along the main pipeline route (i.e., OA2 outlet).

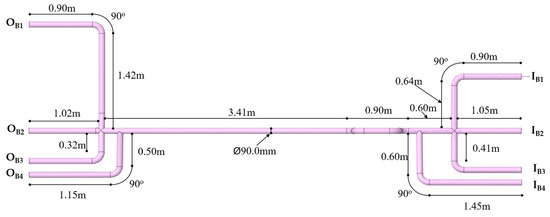

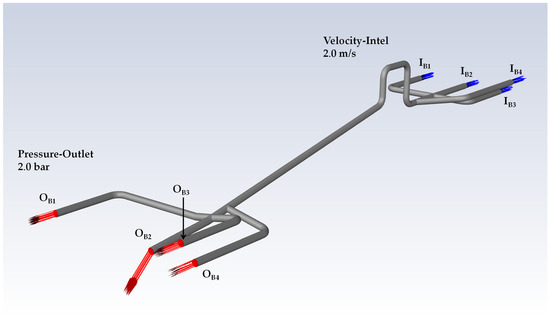

Connection B (Figure 3 and Figure 4) is situated within a residential area and features a different configuration: four inlet HDPE pipes, with an inner diameter of 90 mm, merge into a 90 mm (inner diameter) collector pipeline. The collector pipeline further distributes the water by branching off into four outlet pipes, each with an inner diameter of 90 mm. The system effectively presents a 4 → 1 → 4 configuration that provides a connectivity component to eight pipeline sections via a central header. The four inlet sections meet the central component from various directions with relatively small horizontal shifts. The four outlet sections also branch off at different angles. The primary similarity with Connection A is the existence of four outflowing pipes from a single main. The observations conducted indicated that the direct path (the 90 mm straight-through main) accommodates the majority of the flow, while the other three 90 mm branches convey markedly less.

Figure 3.

On-site photograph of Connection B: four inlet HDPE pipes (right), converging into a 90 mm collector pipeline, which further distributes the water by branching off into four outlets (4 → 1 → 4 configuration).

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of Connection B: four inlet HDPE pipes (right), converging into a 90 mm collector pipeline, which further distributes the water by branching off into four outlets (4 → 1 → 4 configuration).

For both Connections A and B, the geometrical details (pipe diameters, intersection angles, and lengths of straight sections available) were obtained from the network’s GIS database and engineering drawings provided by the MEWSSP. These dimensions were used to construct the 3D CAD models of the junctions. Small-scale features like flange bolts or curb valves were neglected in the model, as they are not expected to significantly influence the internal flow pattern at the junction scale.

Each connection was modeled as a combination of cylindrical pipe segments meeting at a common junction region. Connection A was modeled as two distinct T-junctions separated by a short length of pipe on the main line, closely matching the real configuration. The computational domain for Connection B thus included the first T-junction (with two outlets) and a length of main pipe leading to the second T-junction (with another outlet), ensuring that any interaction between the two junctions (in terms of flow distribution) was captured. In the case of Connection B (one cross-junction and a T-junction), a four-way intersection geometry was created: four inlet and four outlet legs, all merging in the junction chamber.

3. Methodology and Computational Setup

3.1. Mesh Generation

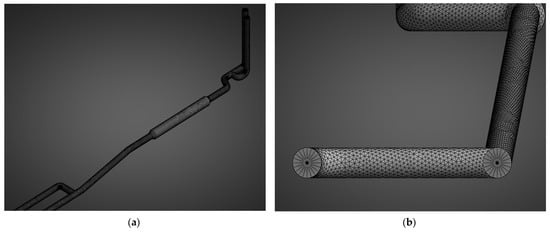

After creating the CAD geometry for each connection, a volumetric mesh was generated for CFD analysis. ANSYS Meshing tools were used to discretize the fluid volume within the pipes. A hybrid meshing approach was adopted: most of each linear pipe segment was meshed by hexahedral elements, swept along the pipeline axis, while the complex junction area was filled by unstructured tetrahedral elements. The junction, where pipes come together, has a complex geometry, which benefits from the flexibility of the tetrahedral meshing. To improve the accuracy of the computational mesh, close to the pipe wall surfaces, a prism layer (inflation) mesh was adopted for all surfaces. The goal was to have at least 5–10 quad-dominant layers (see Figure 5b and Figure 6b) and a smooth growth rate to properly resolve the flow near the wall and evaluate the wall shear stresses. The size of the initial (from the wall boundary) prism layer was set so the dimensionless distance to the wall y+ of the near-wall cell elements would be within the 30–100 interval and thus fall into the region of the logarithmic law applicable by means of standard wall functions [27,34]. This approach complies with the recommended wall treatment guidelines for the standard k-ε two-equation turbulence model of ANSYS Fluent software [32]. Mesh refinement was applied with caution: the branch inlet and junction chamber zones, the regions where flow separation and the highest velocity gradients are expected, were tuned to have a reduced largest cell size relative to the farther downstream and upstream pipe sections.

Figure 5.

Connection A Mesh Generation: (a) General overview of the Mesh Grid and (b) detailed quad-dominant layering.

Figure 6.

Connection B Mesh Generation: (a) General overview of the Mesh Grid and (b) detailed quad-dominant layering.

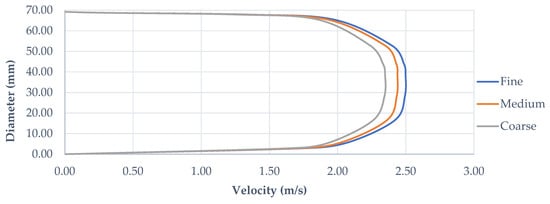

For Connection A (Figure 5a,b), a mesh independence study was conducted to confirm the accuracy of the numerical solution. Specifically, based on the numerical results, the flow distribution rate and pressure loss demonstrated independence from the mesh resolution for all different mesh resolutions examined. Three independent levels of mesh refinement were tested: a coarse mesh of about 350,000 cells, a medium mesh of about 550,000 cells, and a fine mesh of approximately 725,000 cells. The medium mesh included cells of about a maximum of 6 cm size throughout the pipes and as low as 1 cm throughout the core of the junction. Important numerical results, including the velocity profiles, differed by as little as 3.0% between the medium and the fine mesh, indicating numerical robustness (see also Section 4.1). Therefore, the medium mesh resolution was deemed sufficient to yield accurate results and was applied as the reference baseline for all subsequent simulation results.

For Connection B (Figure 6a,b), a mesh independence study was conducted to confirm the results, similarly to Connection A. Specifically, three independent levels of mesh refinement were tested: a coarse mesh of about 400,000 cells, a medium mesh of about 600,000 cells, and a fine mesh of approximately 800,000 cells. The medium mesh included cells of about a maximum of 6 cm size throughout the pipes and as low as 1 cm throughout the core of the junction. Important numerical results, including the velocity profiles, differed by as little as 2.5% between the medium and the fine mesh, indicating numerical robustness (see also Section 4.1).

For both scenarios, the final meshes comprised primarily hexahedral cells throughout the straight sections, along with an intensive packing of tetrahedral/prismatic cells near the intersection zones. An illustration of mesh details within Connection A and Connection B is shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively.

3.2. CFD Simulation Setup

All of the simulations were carried out using ANSYS Fluent 2023 R1 solver. The water was modeled as incompressible fluid at 20 °C, with constant properties (density ρ = 998 kg/m3 and dynamic viscosity μ = 0.001 Pa·s). It was considered that the flow regime was steady-state and turbulent. Gravity effects were included in the model; however, because of the negligible elevation difference between the pipe outlets within each connection (around 1–2 m), the gravitational head component of the flow exerted a negligible impact on the distribution of flow and, hence, was included largely for completeness of the pressure analysis. Equations of interest included the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations governing mass and momentum conservation, and the transport equations of the turbulence model [34]. For the simulation, the standard k-ε turbulence model was chosen [30] with the traditional wall function treatments of the near-wall zones. This selection of the k-ε model was on the basis of its simplicity and satisfactory accuracy for simulating internal pipe flow and turbulence within the joints, coupled with moderate computational costs.

It is noted here that the k-ε model has been widely utilized in similar studies of pipe junction flow [21,28] and broadly captures significant flow characteristics of interest (such as average recirculation zones and decay of jets); however, it might not effectively simulate fine-scale turbulence relative to higher-order models. While higher-order turbulence models or advanced CFD techniques such as the Reynolds Stress Model or Large Eddy Simulation, respectively, could provide further insight [20], the standard k-ε model was deemed satisfactory for the engineering-objective of this study and aligns with industry practice for initial or preliminary design studies [33]. To evaluate the impact of the turbulence models, a comparison simulation for Connection A was conducted using the Re-Normalization Group (RNG) k-ε version. This process yielded virtually the same flow distribution results, varying by under 1.5% in branch flow fraction, thereby justifying the model chosen.

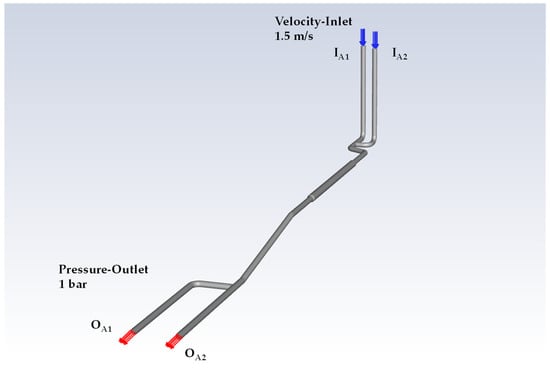

For each of the connection models, the fluid inlets and the outlet connections were specified, corresponding to the actual physical boundaries where the pipes exit the network. For simplicity, and since detailed field boundary data were not available, the inlet boundaries were set as constant total flow, and pressure boundary conditions were set at the outlet boundaries. Specifically, the mass flow inlet, i.e., velocity-inlet boundary condition (or, alternatively, constant, uniform in the cross-section velocity profile) was set at the upstream entrance of the main pipe. For Connections A and B, the total velocity-inlet magnitudes were set equal to 1.5 m/s for each of the 2 inlets (see Figure 7) and 2.0 m/s for each of the 4 inlets (see Figure 8), respectively, corresponding to the design peak flows of the two mains.

Figure 7.

Boundary conditions for Connection A.

Figure 8.

Boundary conditions for Connection B.

At each of the outlet boundaries, the static pressure corresponding to the desired normal operating conditions of the downstream pressure management area (PMA) was prescribed.

More precisely, for Connection A, all outlet boundaries share the same static pressure of 10 m (approximately 1 bar; see Figure 7), while for Connection B, a similar outlet pressure of 20 m (approximately 2 bar; see Figure 8) was considered. An important note to be made here is that equal outlet pressures allow for the flow distribution to branches to be defined based solely on hydraulic resistance, thus mimicking the case where downstream flow is constrained entirely by the upstream pressure or, equivalently, the consumers’ demand may or may not be met depending on the distribution of the inflow to the outlets.

At all solid boundaries (pipe inner wall surfaces), the no-slip boundary condition was stipulated (fluid velocity = 0 at the wall). Typical wall functions took care of the near-wall turbulence. Also, turbulence inlet conditions were assigned by setting a medium turbulence intensity (~5%) and a turbulence length scale of 0.1 times the pipe diameter at the inlet (Fluent’s inherent assumptions for internal flow). The pressure-boundary outlets inherited fully developed outflow conditions (i.e., Fluent automatically extrapolates the turbulence variables to pressure outlets).

It should be noted that the use of fixed outlet pressures in the present study is not intended as a generic simplification, but rather an implementation of the real-world operational strategy followed by MEWSSP. Specifically, the network operates under a pressure-driven approach, where each PMA is hydraulically isolated and equipped with a pressure-regulating valve at its inlet. The valve maintains the downstream pressure at a prescribed set point, largely independent of short-term demand fluctuations within the PMA. Therefore, the assumption of constant outlet pressure at the outlets can be considered an adequate assumption that closely resembles the actual conditions in the network.

In this study, the pressure-based solver within Fluent was employed, so as to analyze incompressible flow dynamics and activate the gravity vector oriented vertically downward to incorporate the hydrostatic pressure components. Further, the model coordinates were configured to ensure that the outlets are approximately aligned at the same vertical height as the inlet. Consequently, the influence of gravity predominantly results in a uniform static pressure offset.

3.3. Solution Setup

Discretization of the convection components of the RANS terms was carried out by using second-order upwind schemes to increase precision. Pressure and velocity couplings were controlled by the SIMPLE algorithm (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations), known to be stable under steady flow conditions. Default under-relaxation factors were upheld (ranging from 0.3 to 0.7 for pressure and momentum and 0.8 for turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate), allowing for convergence. The simulation results for each case contained the flow rate through each of the exits, the pressure and velocity field, and the turbulence parameters (k, ε) throughout the region.

3.4. Verification and Adjustment

Since direct flow measurements at the exact junctions were not available, so as to quantitatively validate the CFD results (in situ flow meters at each branch were not available), an indirect validation was performed by comparing the CFD-predicted head losses through the junctions with empirical formulas from hydraulic engineering handbooks and network model outputs. For both Connections A and B, the simulated minor energy losses (i.e., computed by taking the pressure drop from the inlet to each outlet and relating it to the velocity head) were found to be in good agreement with the results obtained by applying empirical minor loss coefficients found in engineering handbooks [35].

Finally, though not offering direct confirmation, conversations about the qualitative results of CFD simulations with the MEWSSP engineers were conducted, which substantiated the findings linking to downstream areas of the network experiencing insufficient pressure and negligible flow, apart from the primary conduit being constrained or blocked. This qualitative agreement supports the credibility of the numerical results.

Having established and validated the simulation procedure, a systematic study of the flow dynamics and distribution associated with Connections A and B was established. The subsequent section outlines the results, including the distribution of flow into each branch, the distribution of pressure, and the determination of the parameters accountable for the maldistribution observed at each connection.

4. Results

The CFD simulations confirmed the substantial flow maldistribution detected both at Connection A and Connection B, as expected. For both cases, the same outlet, represented by the direct extension of the main line, acquires the major fraction of the inlet flow, while the respective alternative branch outlets carry significantly lower fractions.

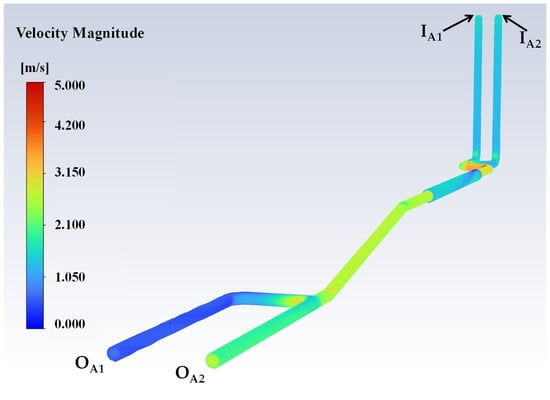

4.1. Flow Distribution Results

For Connection A, the velocity-inlet rates were set equal to 1.5 m/s for each of the 2 inlets (see Figure 7). The CFD simulation shows that approximately 74% (i.e., velocity magnitude of 2.22 m/s) of the water that enters the system flows straight into the 69.2 mm continuing main (outlet OA2), while only 26% (i.e., velocity magnitude of 0.77 m/s) flows through the T-junction branch (i.e., outlet OA1). The velocity contour plot (Figure 9) demonstrates that the primary flow nearly bypasses the branch.

Figure 9.

Velocity contour plot for Connection A.

The maximum velocity computed in the system of Connection A was about 4.93 m/s following the initial two-to-one pipes combination (i.e., Inlets IA1 and IA2 inter-connection), albeit restricted to a slender jet that adhered to one side of the pipe.

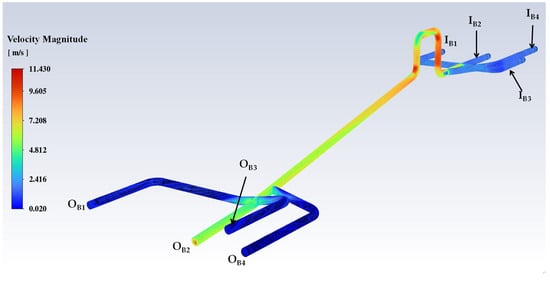

The flow distribution at Connection B (a T-junction followed by a cross-junction on a 90.0 mm line) was qualitatively the same, since the total velocity inlet rates were set to 2.0 m/s for each of the four inlets (see Figure 8). Based on the numerical simulations, it is shown that approximately 84.12% (i.e., velocity magnitude of 6.73 m/s) of the flow proceeds along the 90.0 mm main after the initial T-junction (towards outlet OB2; see Figure 10). Outlet OB4 captures about 8.00% (i.e., velocity magnitude of 0.64 m/s) of the water flow, while Outlets OB1 and OB3 receive approximately 3.13% (i.e., velocity magnitude of 0.25 m/s) and 4.75% (i.e., velocity magnitude of 0.38 m/s) of the total water inflow, respectively.

Figure 10.

Velocity contour plot for Connection B.

Numerical visualization of the flow through Connection B (see Figure 10) accentuates the manner in which the water enters the foremost branch willingly upon availability, but whatever proceeds downstream becomes somewhat “momentum-set” upon the main pipe and refuses to branch off towards the second branch. The maximum velocity recorded in the system of Connection B was about 11.43 m/s following the initial four-to-one pipes combination (i.e., Inlets IB1, IB2, IB3, and IB4 inter-connection), albeit restricted to a slender jet that adhered to one side of the pipe. A substantial portion of branches OB3 and OB4 area experienced backflow or exhibited very low velocity, suggesting that a significant extent of that pipe’s cross-sectional space was effectively not engaged by the incoming flow (presence of a stagnant eddy).

In both cases examined, the numerically predicted results clearly indicate maldistribution of the flow, which favors the shortest path. In the case of the cross-junction of Connection B, as well as the T-junction of Connection A, even though the branches were nominally symmetrical, an insignificant asymmetry in geometry caused an imbalance between the two outflows.

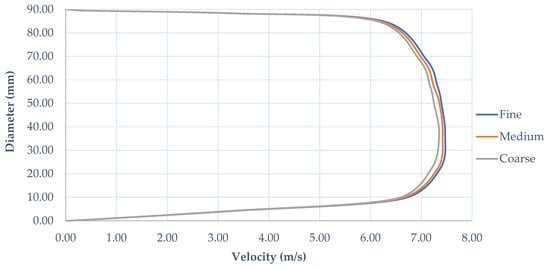

To further assess numerical robustness, velocity profiles were extracted at selected cross-sections located in characteristic regions of the flow for both Connection A and Connection B. These locations were chosen to capture the fully developed portion of the main pipe upstream of the junction (i.e., Outlet OA2 and Outlet OB2). For each location, velocity profiles were obtained using three progressively refined meshes (coarse, medium, and fine; see Section 3.1) and compared directly.

Figure 11 presents velocity magnitude profiles for Connection A (i.e., Outlet OA2), while Figure 12 shows the corresponding profiles for Connection B (Outlet OB2). For clarity, all profiles are plotted in independent coordinates (so as to illustrate the corresponding inner diameter) and highlight the local velocity. Across all examined sections, the profiles obtained from the three meshes collapse closely onto one another, indicating weak sensitivity to mesh refinement (see Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Velocity magnitude profiles at Outlet OA2 obtained using three different mesh resolutions (i.e., Coarse, Medium, and Fine; see Section 3.1).

Figure 12.

Velocity magnitude profiles at Outlet OB2 obtained using three different mesh resolutions (i.e., Coarse, Medium, and Fine); see Section 3.1.

Quantitatively, the maximum deviation between the medium and the fine meshes remained below 2.5% for both sampled locations and configurations. However, these small differences do not alter the qualitative or quantitative conclusions regarding flow maldistribution, branch bypassing, or momentum-dominated behavior observed in both connections. Based on these results, the solution may be considered effectively mesh-independent for the purposes of flow distribution analysis and velocity field characterization. Consequently, the medium mesh was adopted for the remaining post-processing and comparative evaluations, providing an appropriate balance between computational cost and numerical accuracy.

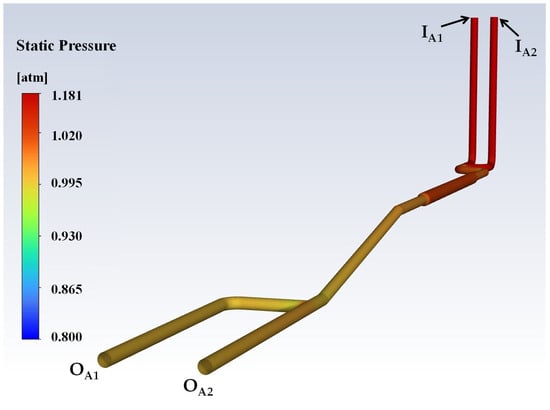

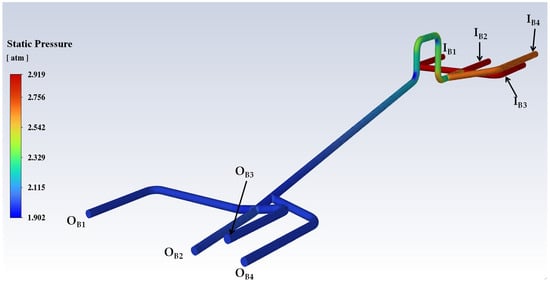

4.2. Pressure Distribution and Head Losses Results

Pressure fields of the CFD outputs reveal the energy distribution and driving forces of the flows. Color contours of the static pressure are shown through each plane of junctions in Figure 13 and Figure 14. At Connection A, the highest pressure occurs at the upstream pipes (Inlets IA1 and IA2: 1.179 atm and 1.181 atm, respectively), and the pressure declines towards each outlet. Since equal pressure was assigned to all of the outlets (10 m head, i.e., 1 atm), the CFD accordingly adjusted the flow so each outlet’s loss would be equal to the total head drop relative to the inlet head. For outlets OA1 and OA2 (which demonstrate velocity magnitudes of 0.77 m/s and 2.22 m/s, respectively), the pressures inside the corresponding branches were slightly lower than the inlet pressures—i.e., the pressure drop along the inlet to those branches was relatively modest. Figure 13 illustrates the pressure contour plot for Connection A.

Figure 13.

Pressure contour plot for Connection A.

Figure 14.

Pressure contour plot for Connection B.

In the case of Connection B, the highest pressure occurs at the upstream pipes (Inlets IB1, IB2, IB3, and IB4: 2.92 atm, 2.91 atm, 2.91 atm, and 2.68 atm, respectively), and the pressure declines towards each outlet. Since equal pressure was assigned to all of the outlets (20 m head, i.e., 2 atm), the CFD accordingly adjusted the flow so each outlet’s loss would be equal to the total head drop relative to the inlet head. The pressure after the 4 ⟶ 1 connection is significantly lower than the inlet pressure—i.e., pressure drop of approximately 1 atm. Figure 14 illustrates the pressure contour plot for Connection B.

Notably, the CFD outputs allow for the distinction between various head loss sources: loss along the pipes versus loss through the junctions. Comparing the pressure drop along an equivalent pipe length to the drop occurring or immediately adjacent to the junction, for the short connections analyzed, it is observed that the latter overwhelms the former. This finding highlights the importance of localized energy losses introduced by pipeline junctions in determining the distribution of the inlet flow to branches.

5. Conclusions

The results strongly suggest that under the same downstream pressure conditions, the present geometries of Connections A and B direct the flow towards the linear (straight-through) path. This means that unless there is sufficiently higher demand (or lower pressure) in the zones supplied by the branching pipes relative to the zone supplied by the straight-through pipe, the former zones would be undersupplied. The PMAs served by these underserving branches actually experienced substantially lower pressures during peak hours. The CFD results illuminate this, as the linear path draws most of the water under constant outflow pressures.

The turbulence modeling approach adopted in this research represents an informed compromise between physical realism and the need for engineering relevance in water distribution simulation problems. While it is known that the standard k-ε model has limitations in cases involving anisotropy, separation, and strain-driven jet breakup, this model has still found extensive use and validation as a reliable approach to simulating steady, time-averaged flow response in pressurized pipe networks [36]. In this specific problem, it would appear that bulk velocity and flow splits among branches would be of major concern, rather than turbulence characteristics and jet unsteadiness.

Another important aspect regards water quality. Low-flow branches give rise to increased residence time of the water within the pipes, leading to lower residual chlorine content [29]. In situations where the flow becomes stagnant for long periods of time, as is the case for Outlet OB3, which captured less than 5% of the total flow, taste and odor problems may arise, along with bacterial growth. The results highlight the fact that branch OA1 of Connection A and branches OB3 and OB4 of Connection B both have specific vulnerability towards this respect.

Finally, the obtained results revealed that traditional network modeling, using junction minor loss coefficients, can efficiently capture local junction losses simulated using advanced CFD solvers.

In conclusion, it should be noted that in order for the water system to be efficient and exhibit adequate pressure management as well as water quality, it is imperative that the distribution of water is regulated by the consumption and not by hydraulic constraints introduced by poor connections. Although designing a WDN promises certain flow rates, it may suffer from practical limitations and ad hoc interventions that may result in flow imbalances. To avoid new and/or remedy existing problems in WDN design and operation, both simulation methods and empirical formulas found in hydraulic engineering handbooks may be of significant help. Regarding the WDN connections studied, improvements in connections A and B can ensure better service level to the connected zones, both in terms of pressures and flow rates, which will be examined in a future study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodological formulation, and interpretation: A.V.S., N.T.F., D.S. and A.L.; data preprocessing, formal analysis, verification, visualization, and writing—original draft preparation: A.V.S.; writing—review and editing, supervision: N.T.F. and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| MEWSSP | Municipal Enterprise of Water Supply and Sewerage of Patras |

| PMA | Pressure Management Area |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| RNG | Re-Normalization Group |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations |

| WDN | Water Distribution Network |

| μ | Dynamic Viscosity |

| ρ | Density |

References

- Grigg, N.S. Water, Wastewater, and Stormwater Infrastructure Management, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langousis, A.S.; Fourniotis, N.T. Elements of Design of Water Supply and Sewerage Works, 2nd ed.; GOTSIS Publications: Patras, Greece, 2024; 722p, ISBN 978-960-9427-89-0. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Mays, L.W. Water Distribution Systems Handbook; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swamee, P.K.; Sharma, A.K. Design of Water Supply Pipe Networks; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Germanopoulos, G. A technical note on the inclusion of pressure dependent demand and leakage terms in water supply network models. Civ. Eng. Syst. 1985, 2, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, A.; Jeffrey, P. Water distribution system vulnerability analysis using weighted and directed network models. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W06517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakoudis, V.; Tsitsifli, S.; Papadopoulou, A. Integrating the Carbon and Water Footprints’ Costs in the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC Full Water Cost Recovery Concept: Basic Principles Towards Their Reliable Calculation and Socially Just Allocation. Water 2012, 4, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutikanga, H.E.; Sharma, S.K.; Vairavamoorthy, K. Methods and Tools for Managing Losses in Water Distribution Systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2013, 139, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A. International Report: Water losses management and techniques. Water Supply 2002, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liemberger, R.; Wyatt, A. Quantifying the global non-revenue water problem. Water Supply 2018, 19, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, A.V. Probabilistic Modeling and Optimization of Leakages in Water Distribution Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Patras, Patra, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, A.V.; Fourniotis, N.T.; Deidda, R.; Kokosalakis, G.; Langousis, A. Leakages in Water Distribution Networks: Estimation Methods, Influential Factors, and Mitigation Strategies—A Comprehensive Review. Water 2024, 16, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.A.M.; Sánchez-Romero, F.J.; López-Jiménez, P.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, M. Improve leakage management to reach sustainable water supply networks through by green energy systems. Optimized case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, A.V.; Kokosalakis, G.; Deidda, R.; Karathanasi, I.; Langousis, A. Probabilistic framework for the parametric modeling of leakages in water distribution networks: Large scale application to the City of Patras in Western Greece. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 3617–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.; O’Rear, L. Evaluation of solute mixing in water distribution pipe junctions. J. AWWA 2009, 101, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gomez, P.; Choi, C.Y.; van Bloemen Waanders, B.; McKenna, S.A. Mixing at Cross Junctions in Water Distribution Systems. I: Numerical Study. J. Water Resour. Plann. Manag. 2008, 134, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bloemen Waanders, B.; Hammond, G.; Shadid, J.N.; Collis, S.; Murray, R. A Comparison of Navier–Stokes and Network Models to Predict Chemical Transport in Municipal Water Distribution Systems. Proc. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. World Water Environ. Resour. Congr. 2005, 2005, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, R.G.; van Bloemen Waanders, B.; McKenna, S.A.; Choi, C.Y. Mixing at Cross Junctions in Water Distribution Systems. II: Experimental Study. J. Water Resour. Plann. Manag. 2008, 134, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajura, R.A.; Jones, E.H., Jr. Flow Distribution Manifolds. J. Fluids Eng. 1976, 98, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y. Turbulent flow in an I–L junction: Impacts of the pipe diameter ratio. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 025122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimadge, G.B.; Chopade, S.V. CFD Analysis of Flow through T-Junction of Pipe. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, A.; Hirani, C.U. CFD Simulation and Analysis of Fluid Flow Parameters within a Y-Shaped Branched Pipe. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. (IOSR-JMCE) 2013, 10, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojevič, M.; Hočevar, M.; Bizjan, B.; Drešar, P.; Kolbl Repinc, S.; Rak, G. Three-Dimensional Numerical Simulation of a Two-Phase Supercritical Open Channel Junction Flow. Water 2024, 16, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaix, J.; Mettille, M.; Drommi, J.L.; Hugo, N.; Münch-Alligné, C. Computational Fluid Dynamics Investigation of the Flow in Junctions: Application to Hydraulic Short Circuit Operating Mode. LHB 2023, 109, 2290025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayasamy, P.T. Integrating CFD Tools for the Simulation and Analysis of Turbulent Flow Dynamics in a Y-Junction Pipe. Semarak J. Therm. Fluid Eng. 2025, 5, 4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paál, G.; Pinho, R.; Maia, R.J. Numerical Predictions of Turbulent Flow in a 90° Tee Junction. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Fluid Flow Technologies (CMFF ’03), Budapest, Hungary, 3–6 September 2003; pp. 573–582. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, N.P.; Maia, R.J.; Proença, M.F.; Pinho, F.T. Edge Effects on the Flow Characteristics in a 90° Tee Junction. J. Fluids Eng. (ASME) 2006, 128, 1204–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.M.; Mohammed, W.S.; Mohamed, T.A.; Alawee, W.H. CFD Simulation for Manifold with Tapered Longitudinal Section. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2014, 4, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hrudey, S.E.; Hrudey, E.J. Safe Drinking Water—Lessons from Recent Outbreaks in Affluent Nations; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Launder, B.E.; Spalding, D.B. The Numerical Computation of Turbulent Flows. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1974, 3, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desamala, A.B.; Dasmahapatra, A.K.; Mandal, T.K. CFD Simulation and Validation of Flow Pattern Transition Boundaries during Moderately Viscous Oil-Water Two-Phase Flow through Horizontal Pipeline. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS. ANSYS FLUENT 2023 R1, Tutorial Guide; ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, L.; Singh, S. Analysis of Fully Developed Turbulent Flow in a Pipe Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2012, 4, 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0131274983. [Google Scholar]

- Idelchik, I.E. Handbook of Hydraulic Resistance, 3rd ed.; Begell House: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1-56700-074-0. [Google Scholar]

- Abujelala, M.T.; Lilley, D.G. Limitations and Empirical Extensions of the k–ε Model as Applied to Turbulent Confined Swirling Flows. Chem. Eng. Commun. 1984, 31, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.