Abstract

The proposed work introduces a sizing algorithm to achieve a desired linear transconductance in the optimization of operational transconductance amplifiers (OTAs) by applying the method to find the initial width (W) and length (L) sizes of the transistors. These size values are used to run the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) to perform a multi-objective optimization of three OTA topologies. The method begins with transistor characterization using MATLAB R2024a generated look-up tables (LUTs), which map normalized transconductance of the transistor channel dimensions, and key performance metrics of a complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology. The LUTs guide the initial population generation within NSGA-II during the optimization of OTAs to achieve not only a desired transconductance but also accuracy alongside linearity, high DC gain, low power consumption, and stability. The feasible W/L size solutions provided by NSGA-II are used to enhance the CMOS design of a memristor emulator, where the OTA with the desired transconductance is adapted to tune the behavior of the memristor, demonstrating improved pinched hysteresis loop characteristics. In addition, process, voltage and temperature (PVT) variations are performed by using TSMC 180 nm CMOS technology. The memristor-based on optimized OTAs is used to design a Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron, which produces identical spike counts (seven spikes) under the same input conditions, though the time period varied with a CMOS inverter scaling. It is shown that increasing transistor widths by 100 in the inverter stage, the spike quantity is altered while changing the spiking period. This highlights the role of device sizing in modulating LIF neuron dynamics, and in addition, these findings provide valuable insights for energy-efficient neuromorphic hardware design.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) represent a paradigm in neuromorphic computing, establishing themselves as the third generation of artificial neural networks [1]. Unlike conventional second-generation neuron models, which rely on continuous activation functions, SNNs more faithfully replicate biological nervous systems’ information processing through temporal pulses (spikes) [2]. This approach is grounded in key neurophysiological principles: temporal information coding, dynamic activation thresholds, and spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) [3].

SNNs operate on a strictly event-driven paradigm, where each artificial neuron maintains a membrane potential modulated by synaptic inputs. A spike (analogous to biological action potentials) is generated only when this potential crosses a critical threshold. This event-driven architecture provides exceptional energy efficiency, as power consumption occurs exclusively during spike generation, unlike traditional neural networks that require continuous processing [4]. This efficiency makes SNNs particularly promising for low-power neuromorphic hardware implementations [5].

From a computational perspective, spiking neuron models capture the essential dynamics of biological membrane potentials through mathematical formulations of varying complexity. Among these, the Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) model stands out for its optimal balance between simplicity and biological plausibility, making it widely adopted in both computational neuroscience and neuromorphic engineering applications [2].

Concurrently, memristors have emerged as crucial components for advancing SNNs, owing to their non-volatile memory properties and ability to emulate biological synaptic behavior [6]. These two-terminal devices combine low power consumption with nonlinear dynamics, enabling efficient implementation of synaptic plasticity mechanisms like STDP. The synergy between memristors and SNNs opens new possibilities for developing more efficient and biologically plausible artificial intelligence systems [7]. The sizing approach described herein not only enhances memristor emulator performance but also establishes a systematic methodology for co-designing analog components and neuromorphic systems using 180 nm TSMC complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) technology. The obtained results provide valuable insights for developing scalable and energy-efficient neuromorphic hardware.

The proposed work integrates theoretical modeling, CMOS analog design, and evolutionary algorithms for the optimization of operational transconductance amplifiers (OTAs), resulting in a hybrid methodology that enhances the neuromorphic behavior of the proposed system. Section 2 details the implementation of CMOS memristor emulators in LIF neurons, describing their dynamics and topology consisting of four blocks. Section 3 introduces a memristor emulator based on a CMOS OTA, presenting its governing equations and dynamic characteristics. Section 4 analyzes three OTA topologies, where transistor channel widths are encoded as integer multiples of the technology parameter LAMBDA, and are optimized by applying the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) to simultaneously achieve three objectives: linear transconductance response, high differential gain, and minimize power consumption. Section 5 presents optimization results including electrical characteristics of all OTA topologies, memristor emulation performance, and a complete characterization of the CMOS memristor emulator-based LIF neuron dynamics across all OTA designs. Finally, the conclusions are summarized in Section 6.

2. CMOS Memristor Emulator in LIF Neurons

Computational models of spiking neurons simulate two fundamental processes: synaptic current integration and action potential (spike) generation [5]. The LIF model extends the basic mechanism by incorporating a passive leakage component that mimics the membrane’s natural tendency to return to its resting potential. The main advantage of LIF models lies in their computational and circuit simplicity, making them particularly suitable for embedded systems and neuromorphic devices. An important thing is that memristors have emerged as promising components for emulating both leakage resistance and synaptic plasticity, enabling the development of more compact and energy-efficient designs [8].

2.1. LIF Neuron Dynamics

The LIF model maintains computational efficiency while being easily implementable in both analog and digital circuits, making it ideal for SNN systems without the complexity of more detailed models [9]. Its behavior can be modeled using a simple electrical circuit comprising a membrane capacitor () in parallel with a leakage resistor (), whose dynamics are described by Equation (1),

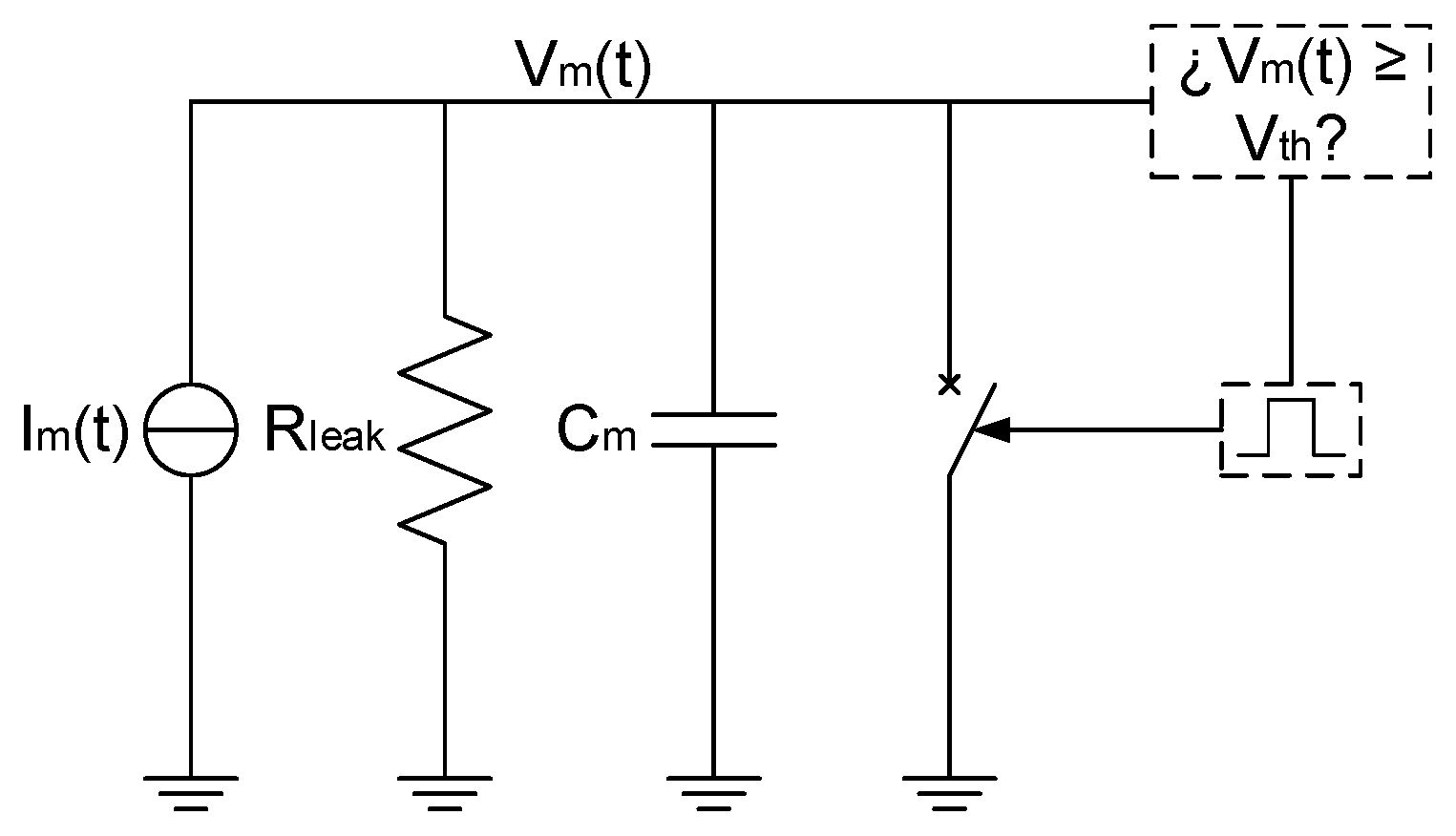

where represents the system’s characteristic time constant. The capacitor accumulates charge in response to an input current (), while the resistor models the membrane’s passive conductance responsible for ion leakage at rest. When synaptic currents excite the neuron, the membrane potential gradually increases. Upon reaching a predetermined threshold , the neuron generates a spike and immediately resets to the resting potential , replicating biological post-spike behavior [10]. The firing mechanism activates when reaches or exceeds , triggering a spike followed by a reset. In the circuit implementation shown in Figure 1, the reset is achieved through a voltage-controlled switch that rapidly discharges the capacitor. This mechanism reproduces two key biological neuron features: action potential generation and the refractory period (a brief post-spike interval during which the neuron cannot fire again).

Figure 1.

Circuit schematic of a LIF neuron model.

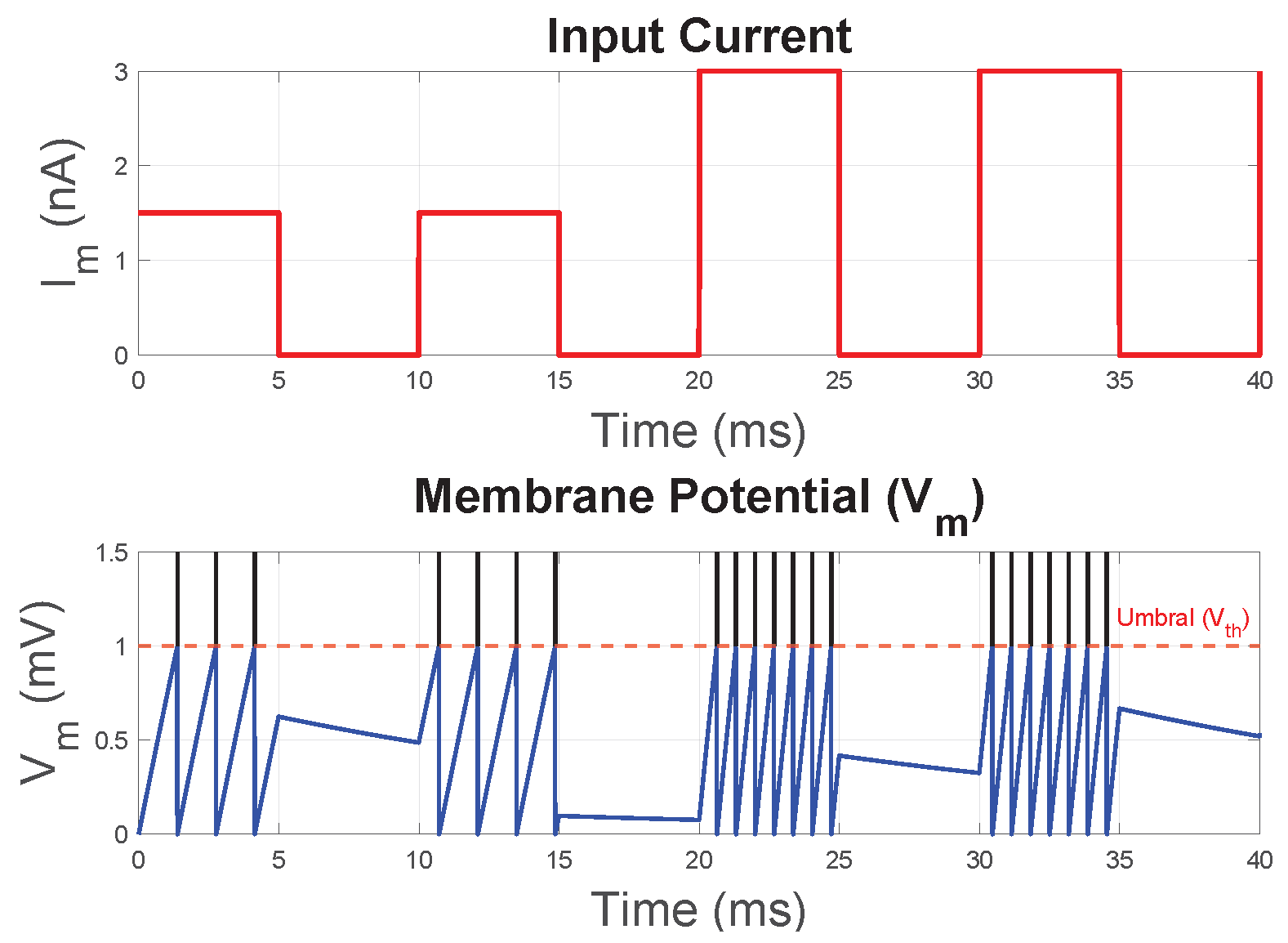

The LIF neuron’s firing rate depends directly on the magnitude, as illustrated in Figure 2. Weak input currents allow leakage to dominate, preventing threshold attainment and spike generation. Conversely, stronger currents accelerate capacitor charging, causing an increase in firing frequency. The input current-to-spike rate relationship enables SNNs to encode information in temporal activity patterns—a fundamental property for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic processing applications.

Figure 2.

Input current vs. output spike graph in a LIF neuron.

2.2. Memristor-Based Volatile LIF Neuron

The dynamic behavior of the LIF neuron circuit shown in Figure 1 can be electronically implemented using comparators and reset circuits, though these additional components significantly increase system complexity [10].

An innovative solution proposed in [8] replaces both the leakage resistor and the reset switch with a volatile memristor. This device exhibits variable memconductance (dependent on charge or flux accumulation), enabling abrupt internal resistance switching with state “forgetting”. The system operates through the following three characteristic phases:

- Resting state: The memristor maintains high resistance, simulating the membrane’s elevated basal resistance.

- Integration phase: Input current progressively charges , causing exponential growth.

- Firing and reset: When exceeds , the memristor abruptly switches to low resistance, rapidly discharging (generating a spike) before spontaneously returning to high resistance—eliminating external reset circuitry requirements.

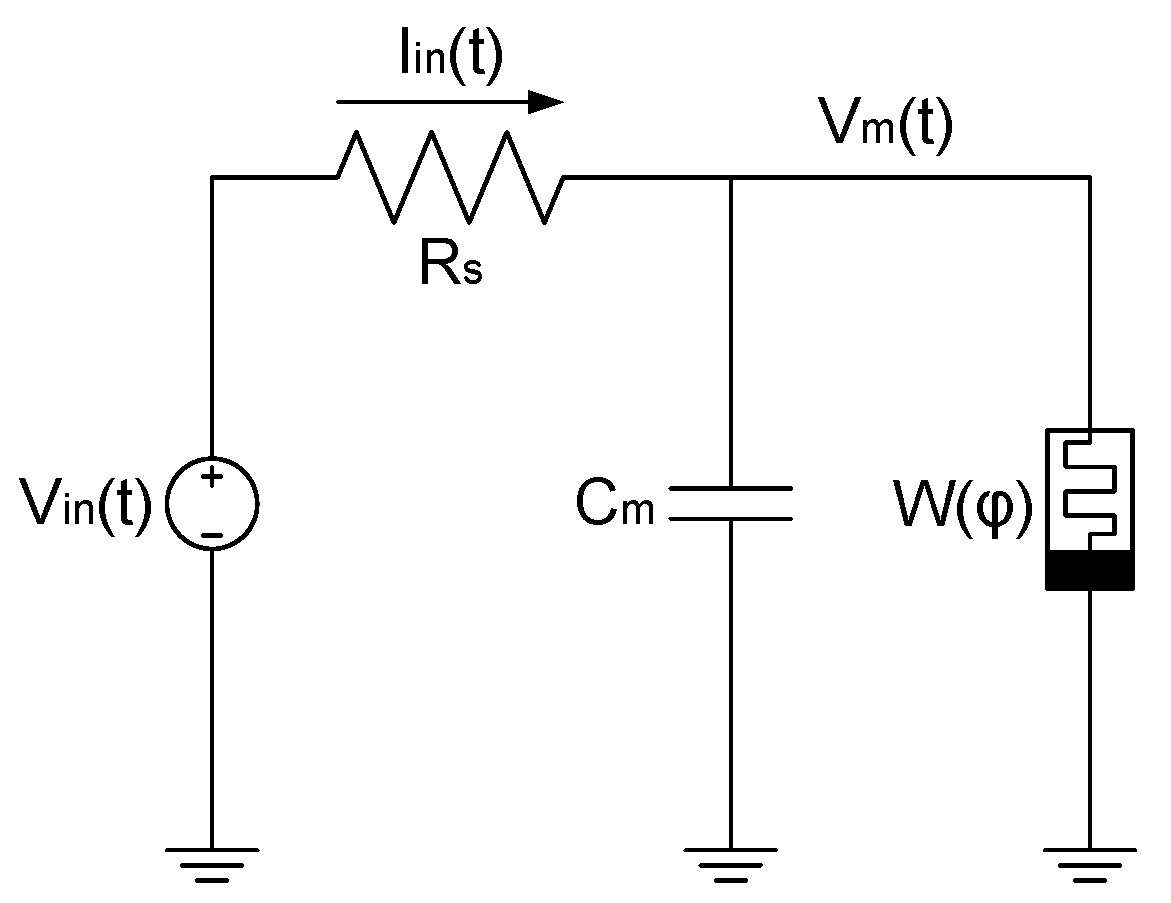

This approach significantly simplifies the architecture of the LIF neuron by eliminating additional active components while achieving more biologically plausible behavior through natural emulation of depolarization/repolarization processes. The design also improves energy efficiency by capitalizing on the volatile memristor’s intrinsic properties. As schematically shown in Figure 3, the implementation consists of a voltage-to-current conversion network (where is transformed to through ), a membrane integration capacitor , and a parallel-connected memristor that dynamically regulates charge leakage [11]. The modified membrane potential dynamics are described by Equation (2),

where the memristive current is

Figure 3.

Circuit schematic of a memristor-based LIF neuron model.

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal evolution of this system, revealing important nonlinear relationships between input excitation and spiking response. The plot clearly demonstrates how changes in volatile memconductance during current pulses directly influence spike generation frequency. The memristor’s state-dependent resistance creates an adaptive leakage pathway that naturally maintains high resistance during subthreshold integration while providing rapid discharge during spiking events, all without requiring external control circuitry for reset operations.

Figure 4.

Input voltage vs. output spike graph in the memristor-based LIF neuron model.

2.3. CMOS Design of a Memristor Emulator-Based LIF Neuron

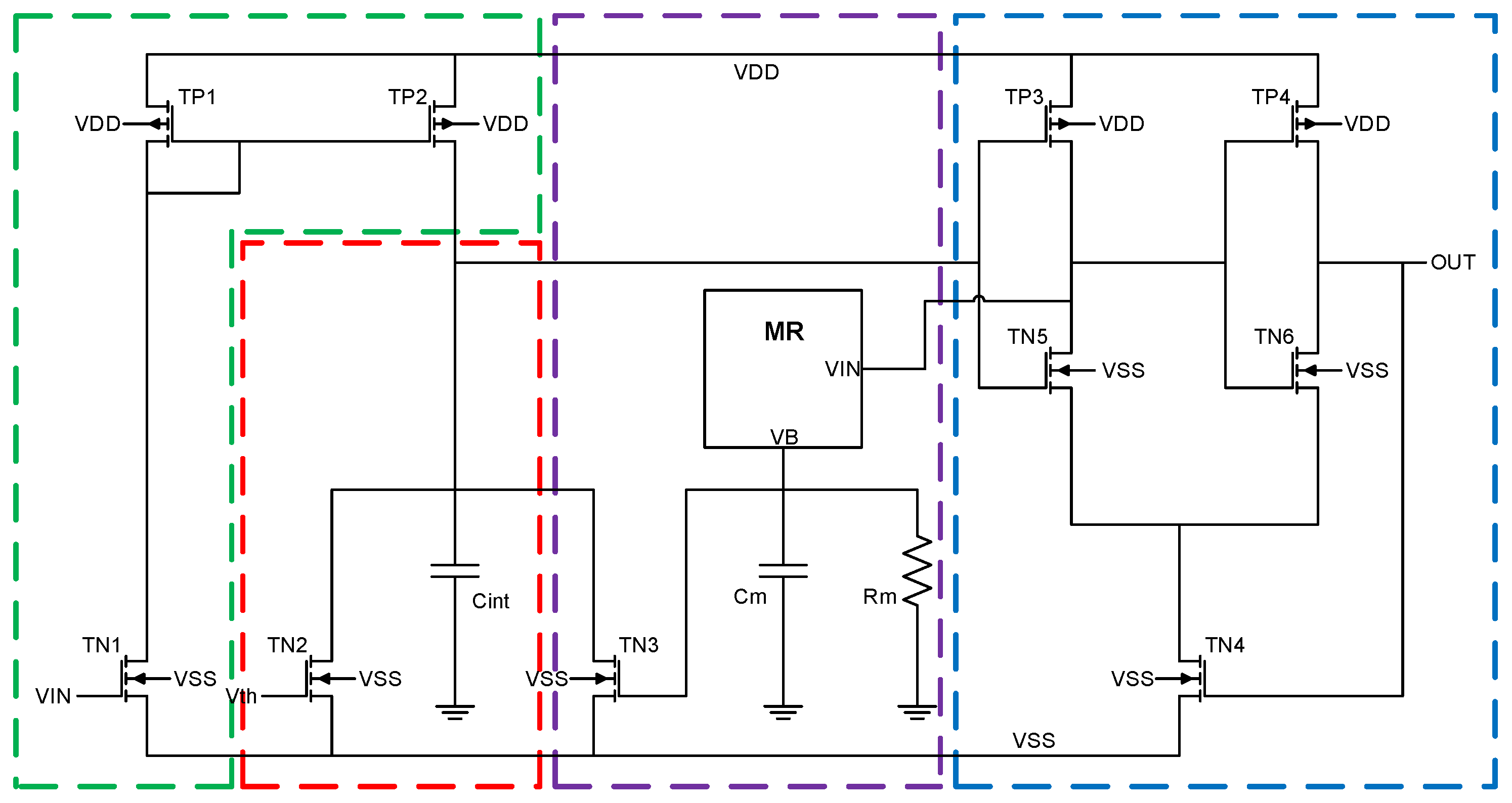

A more sophisticated circuit implementation of the neuronal model, based on the analog spiking neuron proposed by [12], and modified by [13] to incorporate a memristor emulator, is shown in Figure 5 [13]. It employs a modular architecture comprising four interconnected functional blocks. The use of devices with stable states enhances circuit performance by allowing the resistance states and to be reliably programmed with voltage or current pulses. These stable resistance states can be directly associated with binary information, making the design particularly suitable for memory-oriented applications such as synaptic-weight storage.

Figure 5.

Memristor emulator-based LIF neuron divided into four blocks: current mirror (green), integrator (red), memristive reset module (purple), Schmitt trigger (blue).

The blocks embedded in Figure 5 have the following characteristics:

- Current Mirror: This stage replicates and isolates the input current while providing a stable signal to the integrator. Its symmetric design ensures precise current injection regardless of power supply variations, maintaining consistent operation across different input conditions.

- Integration: The integration stage incorporates a capacitor that accumulates the injected current. In this implementation, a transistor is connected in parallel to the capacitor, which can be modeled as an equivalent conductance . This modifies the integration equation to account for the leakage current through the transistorwhere represents the membrane potential. The presence of the conductance causes to exhibit a leaky integration behavior, gradually approaching a steady state if is constant, until reaching the firing threshold.

- Memristive Reset Module (MRM): The MRM replaces conventional reset circuits by leveraging the memristor’s intrinsic properties. During spike generation, the memristor (MR) automatically transitions to a conductive state, followed by a passive self-reset to high resistivity, as further explained in Section 3.

- Schmitt Trigger: A comparator with hysteresis provides enhanced noise immunity through its symmetric thresholds. This circuit generates well-defined digital spikes when exceeds while preventing unwanted oscillations during the reset phase. The hysteresis window ensures robust spike generation even in the presence of signal fluctuations.

The CMOS topology shown in Figure 5 offers advantages like improved firing accuracy through the Schmitt trigger implementation, enhanced dynamic control for tuning integration () and reset () time constants, and adaptive spiking behavior enabled by the nonlinear dynamics of the memristor emulator. The system demonstrates progressive frequency reduction in response to repeated stimuli and natural adaptation to input patterns, closely mimicking biological neuronal properties.

3. CMOS OTA-Based Memristor Emulator

Operational transconductance amplifiers (OTAs) are essential components in analog circuit design, used in applications such as precision filters [14], sample and hold circuits [15], rectifiers [16], analog-to-digital [17] and digital-to-analog [18] data converters.

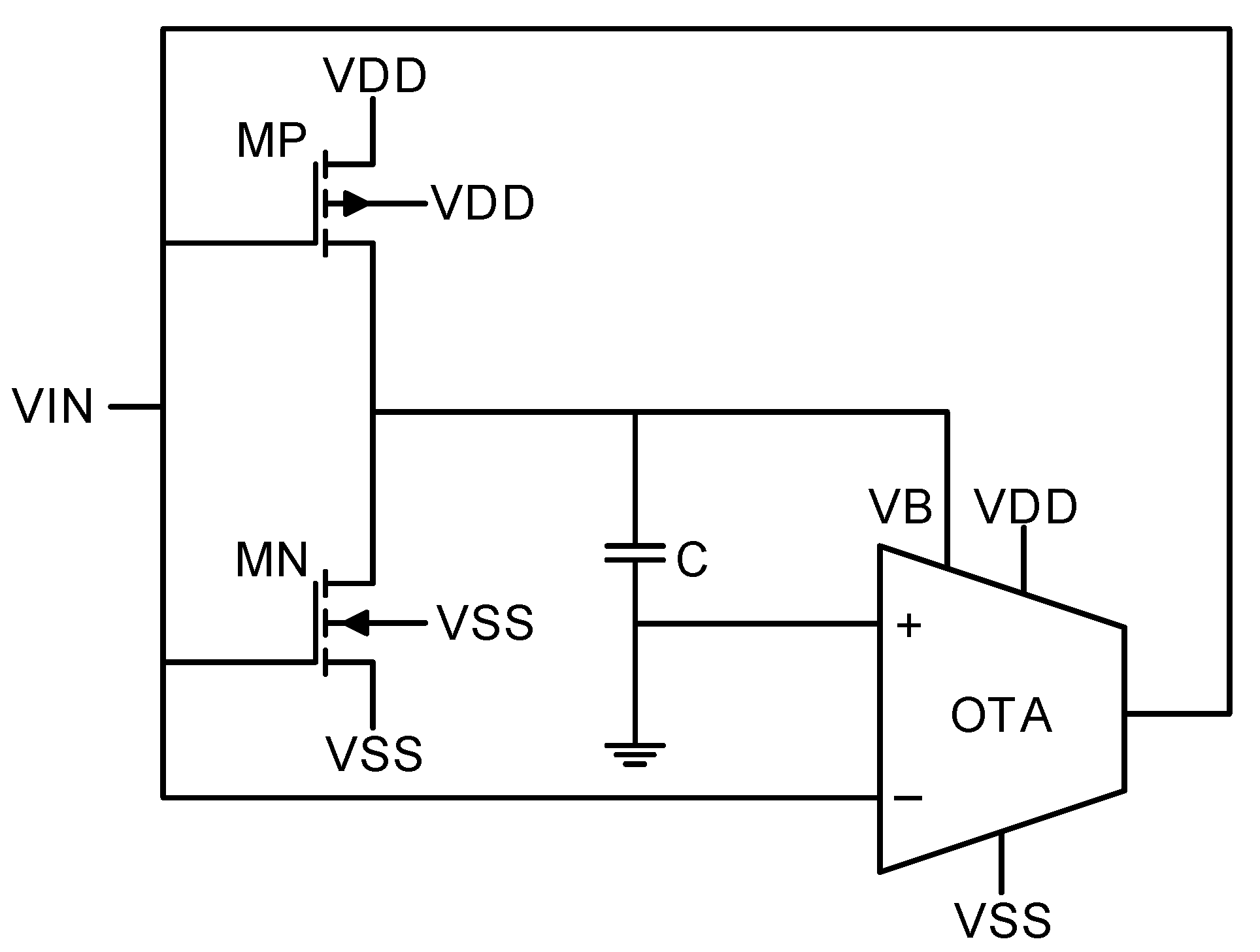

The memristor (MR) emulator design embedded in Figure 5 is designed according to Figure 6 [13]. It consists of an OTA as its fundamental building block, which operates as a voltage-controlled current source, so that the output current () is determined by the transconductance gain () and the differential input voltage, i.e., . In such a topology, is dynamically adjusted through a bias voltage , thus having dependence on biasing conditions, as described in Equation (5).

where represents the source voltage of the biasing transistor, denotes the MOSFET threshold voltage, and constitutes the technology-specific parameter encompassing mobility (), oxide capacitance (), and transistor sizing values.

Figure 6.

Grounded memristor emulator based on an OTA.

The memristor emulation circuit shown in Figure 6, integrates three key components: a CMOS inverter, a storage capacitor (C), and the OTA. The dynamic behavior emerges from the interaction between the OTA’s transconductance and the integrating action of the CMOS inverter-capacitor pair. The integration is mathematically expressed as

where represents the effective transconductance of the CMOS inverter. Substituting Equation (6) into Equation (5), one receives the description of the OTA’s effective transconductance, given by Equation (7).

To ensure linear transconductance operation within the input voltage range of [−0.5 V … 0.5 V], the transistors in the CMOS inverter are sized with m, m, and m. These sizes maintain = 0.55 V in large-signal operation while preserving the virtual ground condition at .

When driven by a sinusoidal input with maintained at virtual ground, the system exhibits memristive characteristics described by the memductance equation

As the linearity and stability of across the operating range are difficult to accomplish, this work proposes an optimization framework for sizing OTAs by combining the methodology with the NSGA-II evolutionary algorithm, which allows Pareto-optimal topology exploration. This hybrid sizing approach enables simultaneous optimization of power consumption, linearity, and silicon area, while maintaining the desired memristive emulation characteristics.

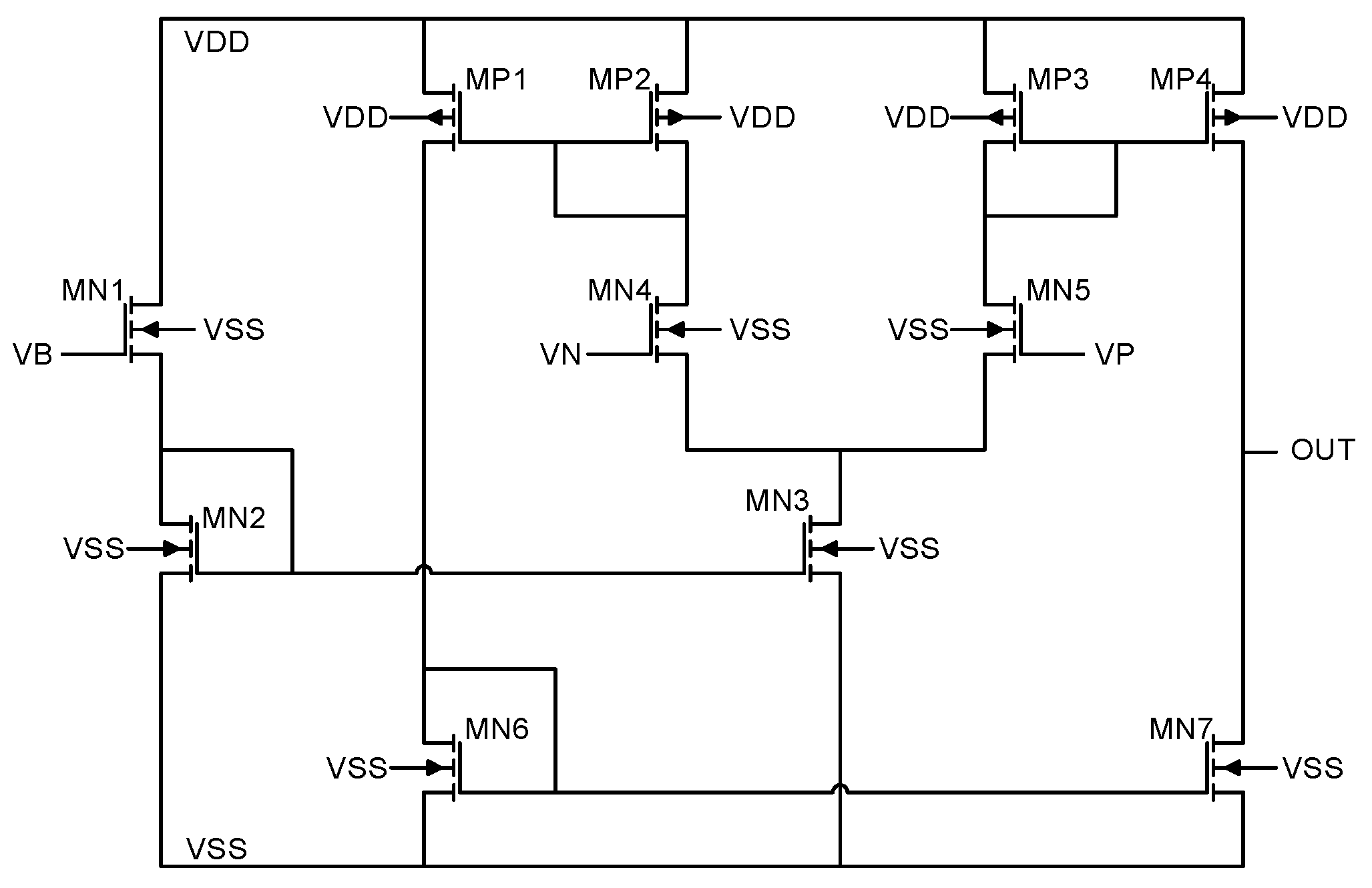

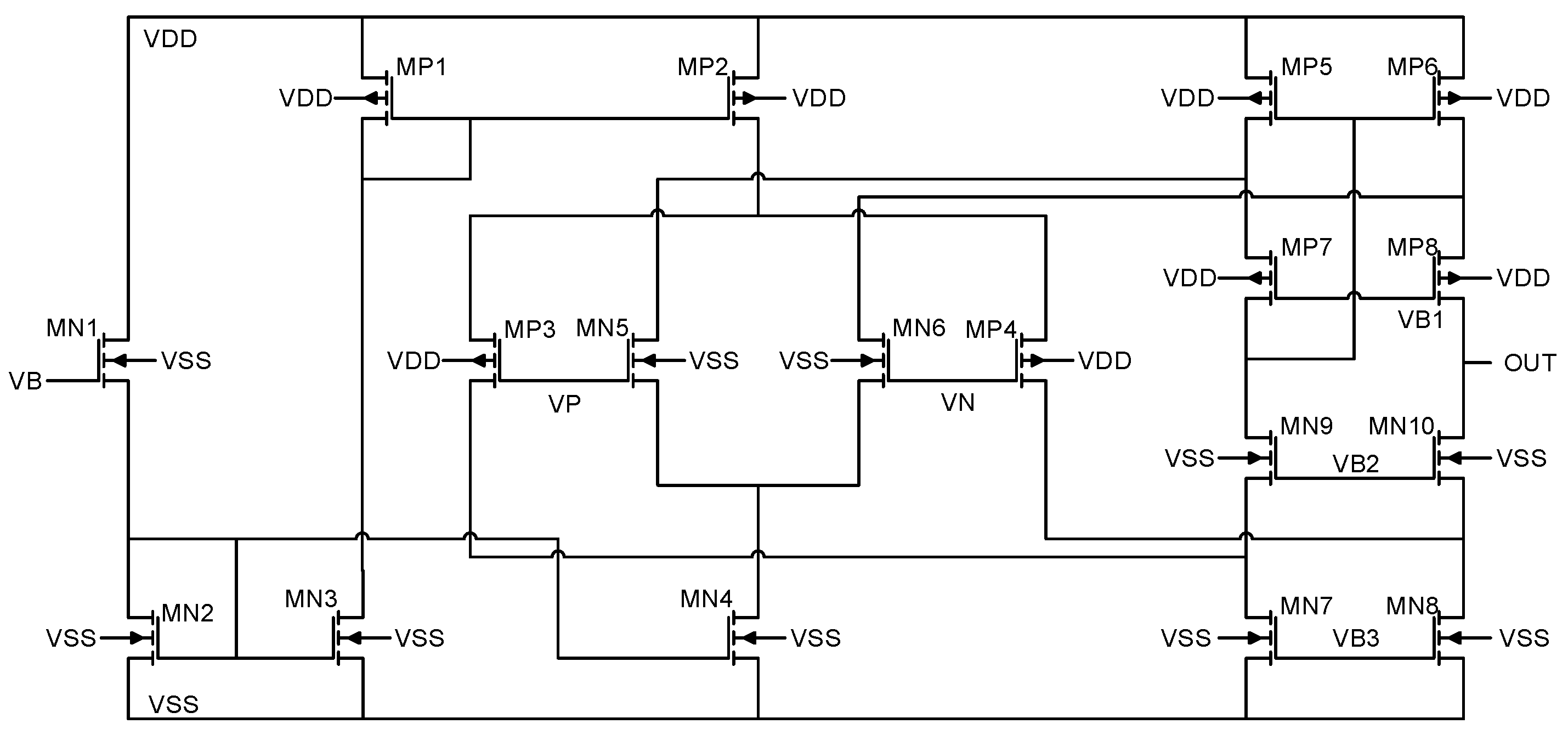

4. Sizing CMOS OTA Topologies

This section describes the optimization of the three OTA topologies shown in Figure 7 [19], Figure 8 [20], and Figure 9 [21]. Each OTA topology adopts the following bias voltages: 0.55 V, = 0.3 V, = −0.1 V and = = = −0.3 V.

Figure 7.

Current mirror OTA topology.

Figure 8.

Folded cascode OTA topology.

Figure 9.

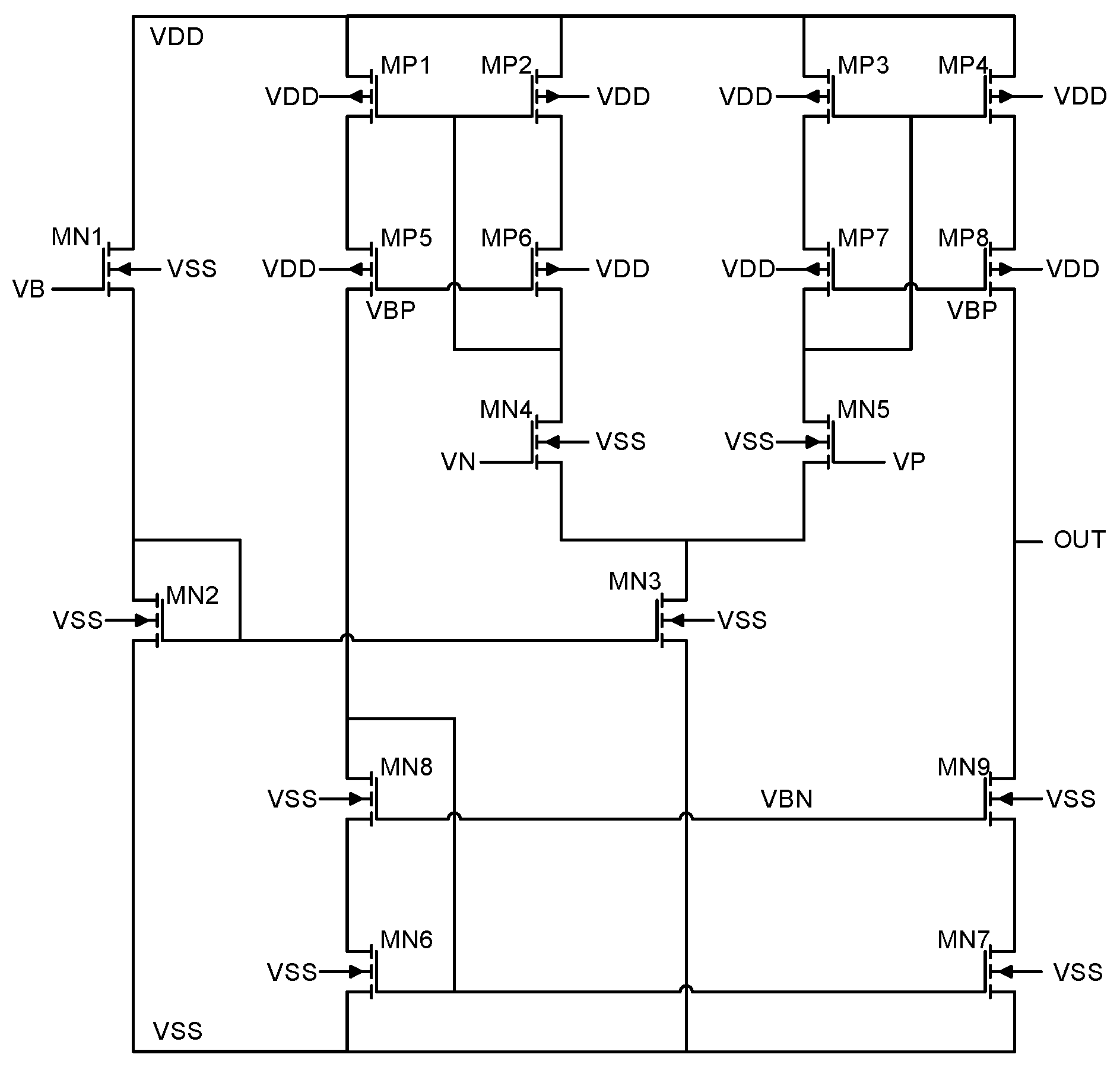

Low-voltage current mirror OTA topology.

As outlined in Section 1 and Section 3, a hybrid methodology integrating the approach with the NSGA-II evolutionary algorithm can be applied to transistor sizing in CMOS analog design, ensuring compliance with target OTA specifications, as the ones considered in this work and given in Table 1, which were obtained from [13].

In this work, the initial sizes of the MOS transistors for the three OTAs are encoded in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. It can be seen that the channel length (L) is established by a multiple of the technology, while the widths (W) are the design variables for different sets of transistors and for each OTA topology. Specifically, the channel length is a multiple of LAMBDA when working with 180 nm CMOS technology, being m m. The sizing methodology for the OTA topologies is described as follows.

Table 2.

Transistor encoding design variables for the current mirror OTA shown in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Transistor encoding design variables for the folded cascode OTA shown in Figure 8.

Table 4.

Transistor encoding design variables for the low-voltage current mirror OTA shown in Figure 9.

4.1. Sizing Methodology

Advancements in semiconductor fabrication technology have made non-ideal effects increasingly prominent, rendering traditional design methodologies (such as the square-law model) inaccurate and leading to significant discrepancies between theoretical predictions and SPICE simulation results. To address this issue, the methodology has been adopted from one decade ago [22]. This sizing technique employs lookup tables (LUTs), generated through DC analysis using BSIM models, to establish relationships among key parameters such as transition frequency (), intrinsic gain (), current density (), and transconductance efficiency (). The LUTs are generated once, and are computationally efficient, and reusable across the design process [23].

During the CMOS design of the OTAs, one must select target values for , drain current (), and channel length (L). Afterwards, each transistor width () in each OTA design is calculated through the following equation:

where retrieves the current density () associated with a given and L. This process achieves a desired circuit performance that aligns closely with SPICE simulations, enabling precise and predictable control over transistor electrical parameters [24].

The MATLAB R2024a code proposed in [25] automates the generation of LUTs and extracts W values for the selected L and biasing conditions of each MOS transistor, based on a predefined SPICE netlist. One issue is how to ensure that relationships are multiples of . This was solved by performing an integer encoding process along with the generation of the SPICE netlists [26]. Basically, this requires defining a global parameter (LAMBDA) in the SPICE netlist, so that Ws are expressed as multiples of , as shown in Listing 1. Thus, each transistor’s width () is calculated as , where is a dimensionless integer and X denotes each design variable in the OTA topologies.

| Listing 1. Example of using λ as parameter scaling in a SPICE netlist. |

| .PARAM LAMBDA = 0.09u |

| M_P D G S B PMOS L=1u W={Var1∗LAMBDA} |

| M_P D G S B NMOS L=1u W={Var2∗LAMBDA} |

The sizing values for the MOS transistors that are obtained via the method are summarized in Table 5, for each OTA topology, and include the transistor widths () from Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. Some electrical characteristics are also summarized in Table 6, such as open-loop gain (), bandwidth (), transconductance, margin phase, and voltage offset.

Table 5.

First iteration with method for sizing OTAs.

Table 6.

OTA parameters obtained from the first iteration with .

4.2. NSGA-II Algorithm

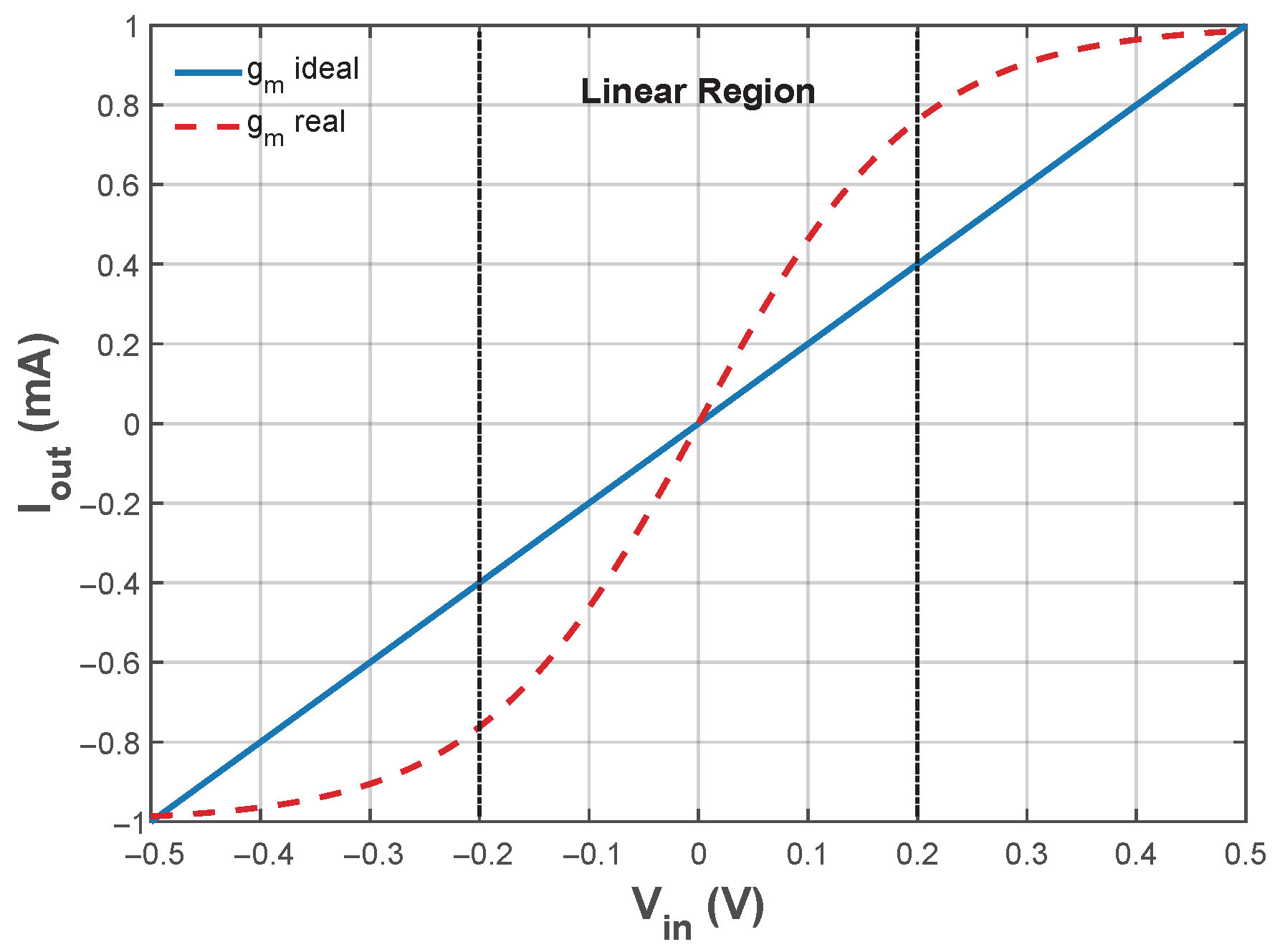

The sizing results given in Table 5 are useful if the design does not require a linear transconductance gain of the OTA. In fact, in the majority of cases, the automated characterization does not ensure constant transconductance across a linear region, as the one shown in Figure 10. To address this limitation, the proposed work shows the optimization of OTAs to achieve a linear transconductance by combining the method and NSGA-II algorithm. This sizing approach handles discrete integer variables () during design-space exploration and optimizes multiple objectives simultaneously under defined constraints [27]. The sizing process also involves generating SPICE netlists that manipulate integer values that multiply LAMBDA, to produce individuals mapped to the OTA’s physical sizing parameters.

Figure 10.

Comparison between the Ideal and Real transconductance in the I–V plane for a given CMOS OTA topology.

NSGA-II has proven its usefulness for solving complex multi-objective optimization problems in analog integrated circuit design [28]. This evolutionary algorithm excels at balancing the trade-offs between conflicting performance parameters during CMOS OTA transistor sizing.

The proposed automated sizing methodology encodes the OTA circuits in a SPICE-compatible netlist. A DC analysis evaluates the transconductance gain by sweeping the input voltage (from −0.2 V to 0.2 V) and measuring the corresponding output current, plotted on the I–V plane. Figure 10 contrasts the ideal I–V curve with that of a physical CMOS OTA, revealing deviations induced by nonlinearities.

The goal is to maximize transconductance linearity within the [−0.2 V … 0.2 V] range, quantified via the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) that is evaluated by Equation (10). This metric computes the RMS deviation among n sampled points from the ideal and actual current curves, ensuring predictable performance for critical applications such as memristor emulator design.

In the proposed work, NSGA-II is executed by generating an initial population of 20 individuals. These individuals are seeded with baseline values obtained through the methodology, as given in Table 5 to provide reasonable starting points and constrain the search space. Each individual represents a complete set of transistor dimensions for a specific OTA topology, encoded as integer variables in the range [40 … 8000]. These integers correspond to multiples of the technology parameter , directly determining the physical ratios of the transistors. Therefore, the objective function is devoted to maximizing a linear transconductance, its associated DC gain, and the inverse value of the power consumed, as given in Equation (11), which includes some constraints.

The algorithm is executed over 50 generations, with each iteration following the standard NSGA-II workflow (Algorithm 1) to optimize the three objectives defined in Equation (11). The evaluation phase performs SPICE simulations to accurately assess each candidate OTA’s performance metrics, including open-loop voltage gain (), bandwidth (), low power and a special focus on transconductance linearity. This simulation-based approach provides significantly more accurate performance evaluation compared to initial analytical approximations, enabling reliable optimization of the OTA topologies.

| Algorithm 1 NSGA-II algorithm |

|

The optimization process employs simulated binary crossover (SBX), a recombination operator designed for real-valued representations that emulates the behavior of single-point crossover in binary-coded genetic algorithms [29]. In SBX, two parent solutions are combined to produce two offspring whose genes are distributed around the parents’ values according to a probability density function controlled by the distribution index . A higher value results in offspring closer to their parents (exploitation), whereas a lower promotes greater diversity (exploration). In this study, the crossover probability indicates that recombination occurs in 90% of mating events, and the chosen provides a balance between exploring new regions of the design space and preserving promising traits from the parents.

Complementing this, polynomial mutation introduces small stochastic perturbations in the offspring’s design variables, ensuring sufficient diversity within the population [29]. This operator modifies each variable with a mutation probability of , according to a polynomial probability distribution governed by the distribution index . Higher values produce smaller, fine-grained mutations (favoring local search), while lower values allow larger variations (favoring global exploration). By applying controlled perturbations, polynomial mutation helps prevent premature convergence and enhances the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima, thereby improving the robustness of the optimization process.

A critical implementation aspect involves handling design constraints, particularly DC offset, phase margin, transistor saturation conditions, and minimum gain/bandwidth requirements to ensure compliance with target specifications from Table 1. These constraints are incorporated through a penalty mechanism that progressively guides the population toward feasible solutions while maintaining diversity.

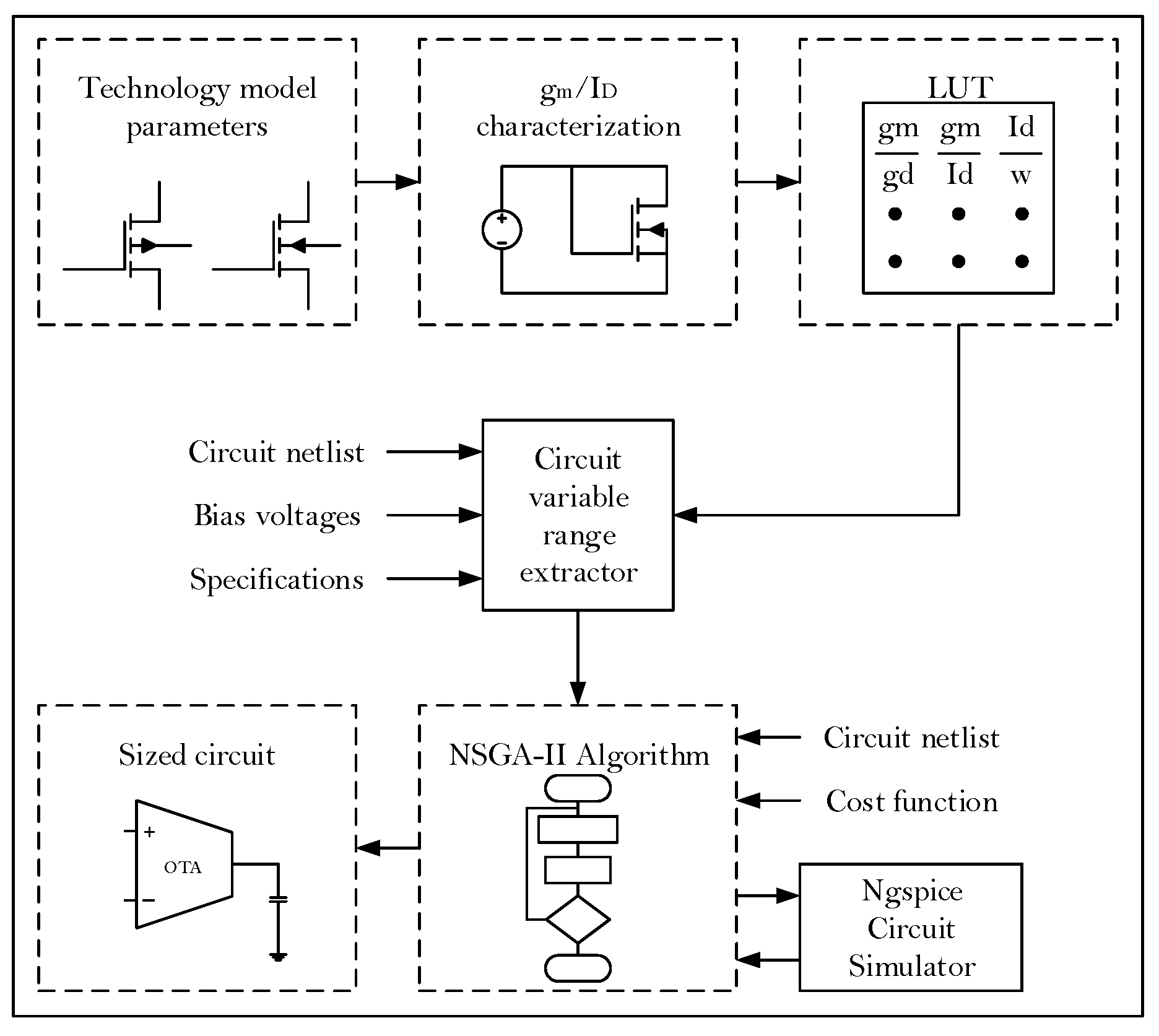

The algorithm converges to a Pareto front (PF) of non-dominated solutions representing optimal trade-offs between competing objectives. For the CMOS OTA design, this translates to a configuration set ranging from high-gain/low-speed versions to moderate-gain/wide-bandwidth designs, including intermediate options that balance both parameters while maintaining linear transconductance response. Figure 11 outlines the proposed systematic methodology integrating these computational techniques.

Figure 11.

Proposed circuit sizing optimization approach.

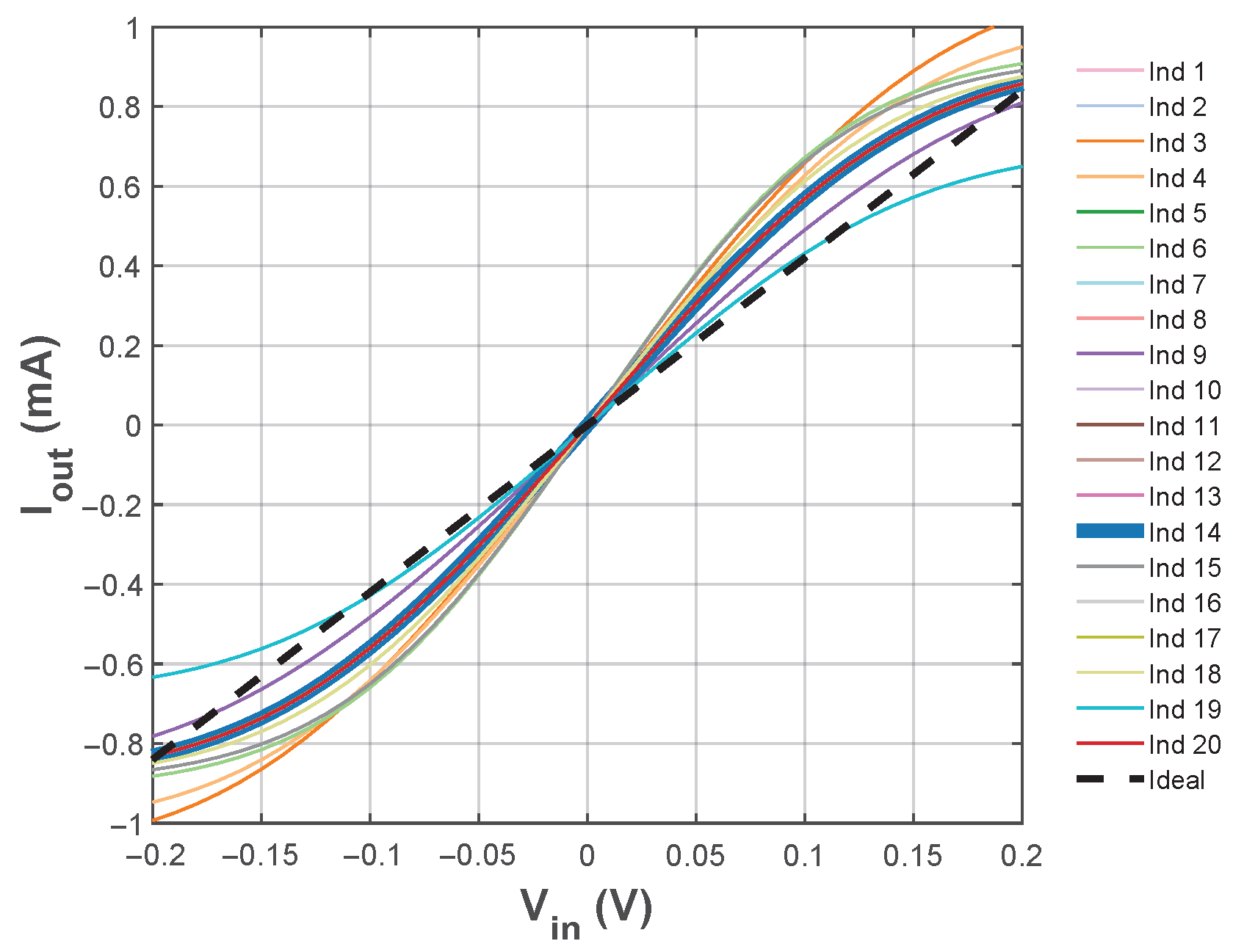

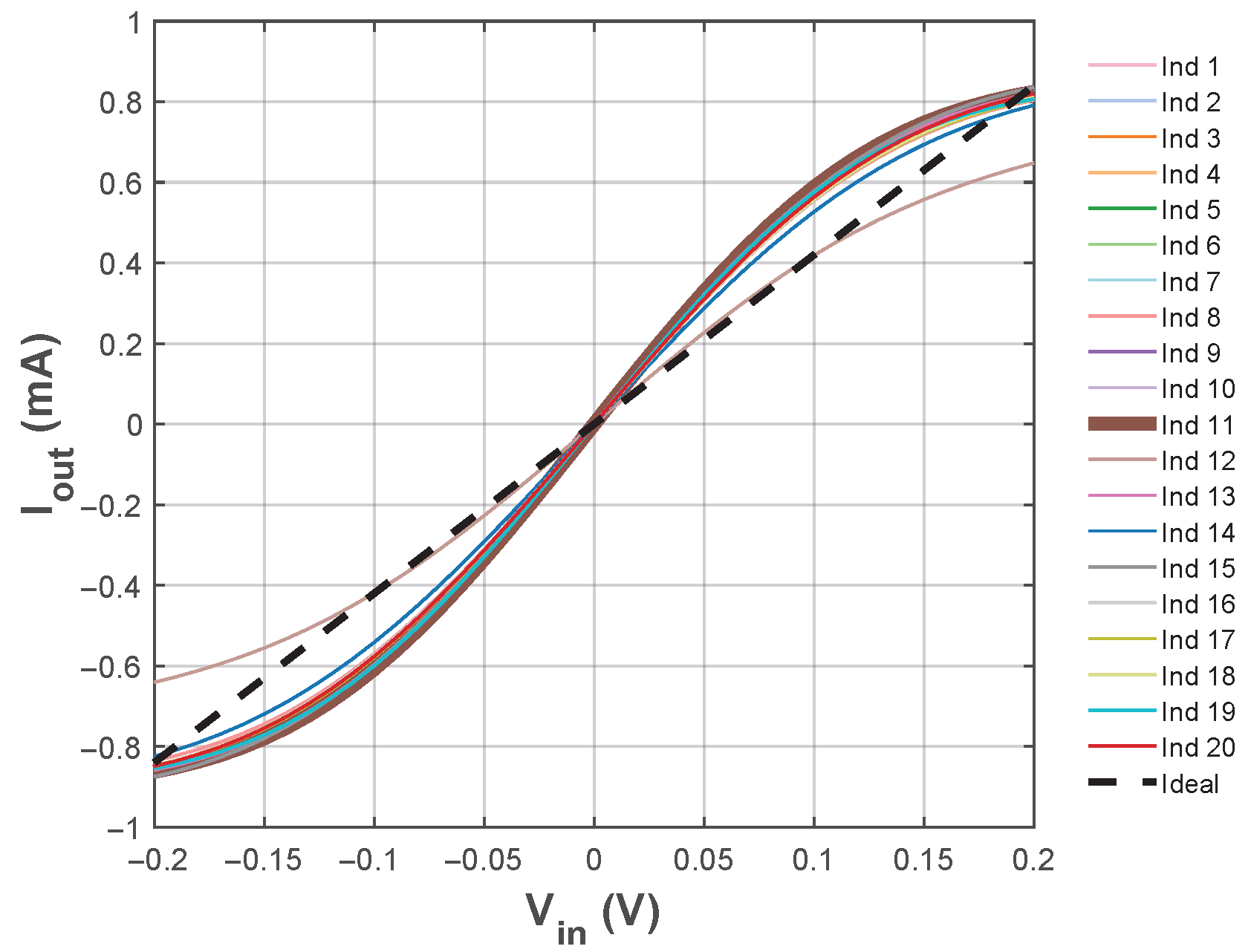

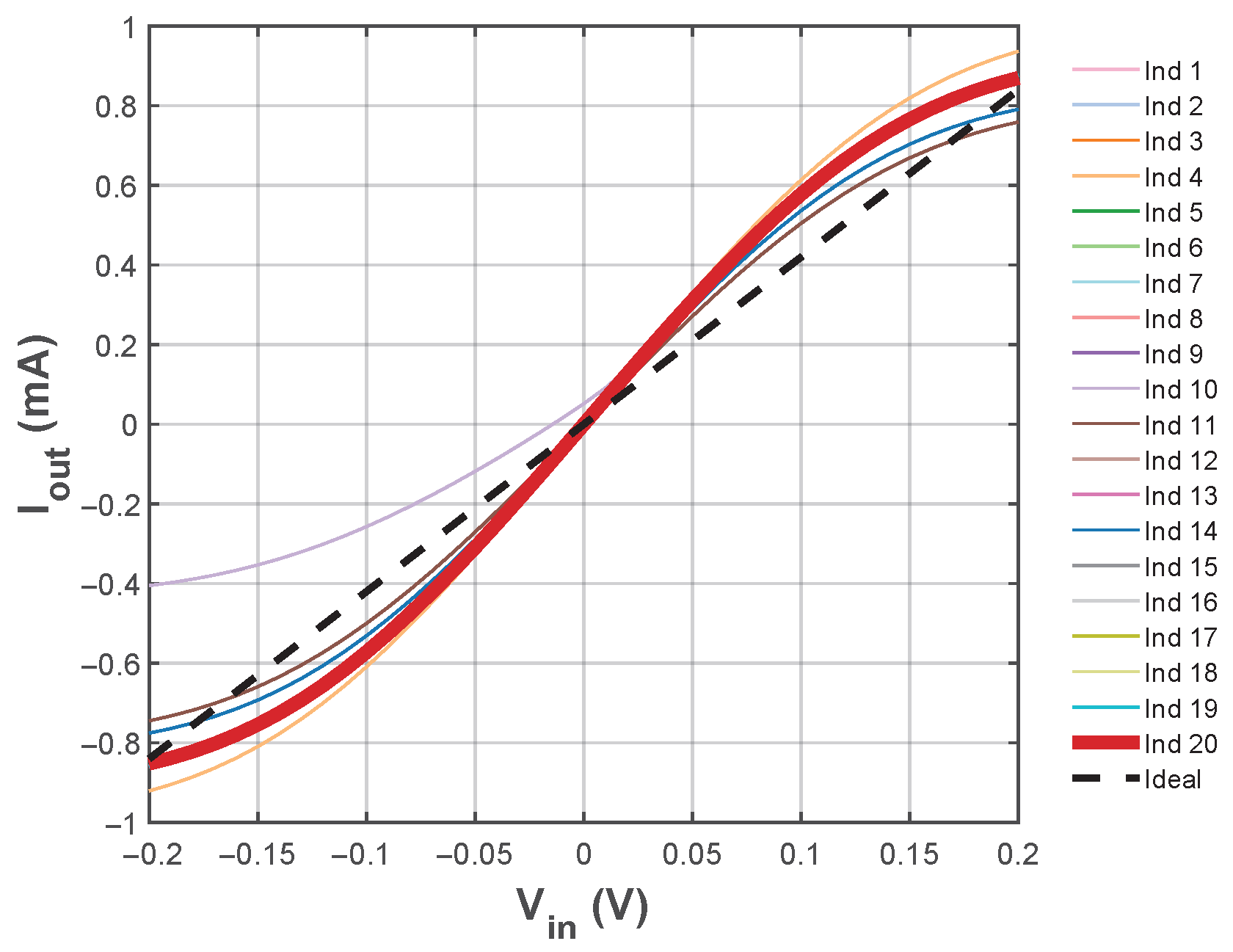

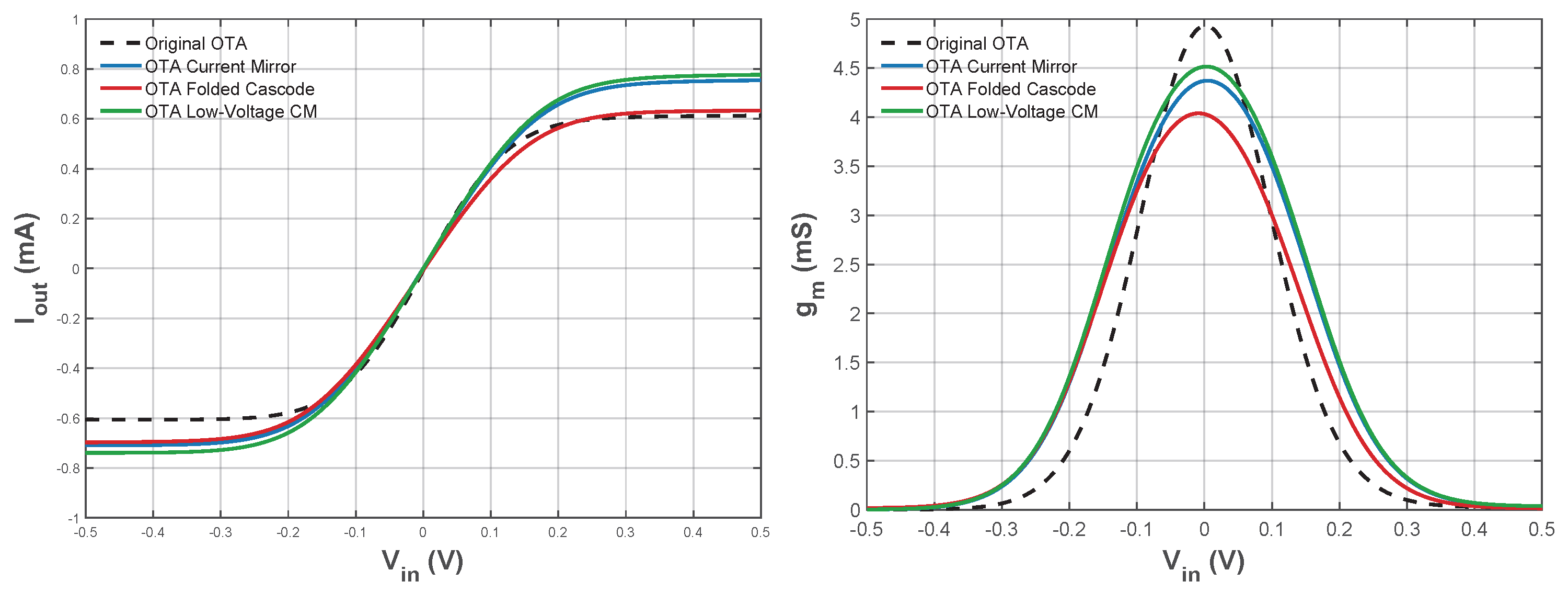

Final sizing results for the optimization of the three OTA topologies provide the transconductance shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, displaying all 20 candidate solutions for each OTA topology. Table 7 summarizes the optimal configurations, with the best linearity performance (indicated by thick lines in the figures) selected from the Pareto-optimal set.

Figure 12.

Transconductance from the sizing results with NSGA-II for the current mirror OTA topology.

Figure 13.

Transconductance from the sizing results with NSGA-II for the folded cascode OTA topology.

Figure 14.

Transconductance from the sizing results with NSGA-II for the low-voltage current mirror OTA topology.

Table 7.

Last generation with NSGA-II for sizing of OTAs.

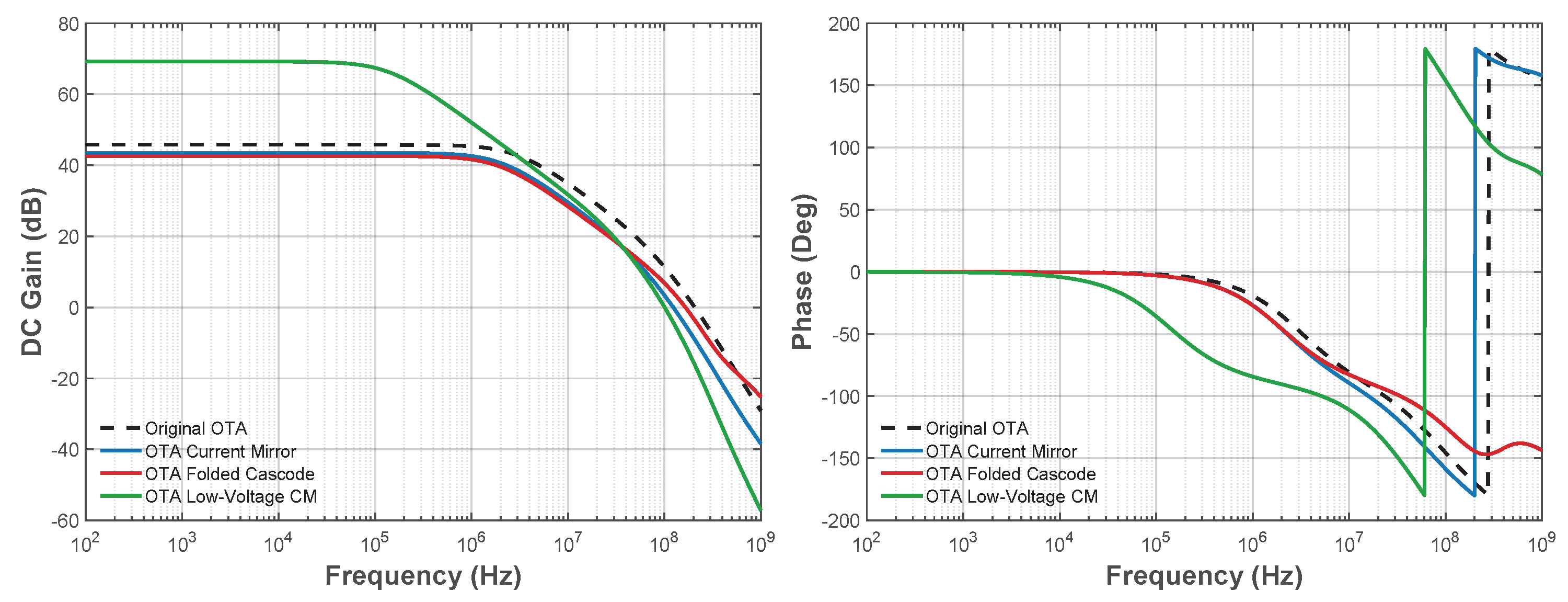

Table 8 summarizes the parameters extracted for the OTAs and compares them with those reported for the topology in [13], under equivalent operating conditions. These values were obtained from Figure 15 and Figure 16, which correspond to the DC and AC analyses, respectively.

Table 8.

OTA parameters obtained from the last generation with NSGA-II vs. Original OTA from [13].

Figure 15.

Comparison of DC analysis between OTA topologies: vs. (left) and vs. (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

Figure 16.

Comparison of AC analysis between OTA topologies: magnitude (left) and phase (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

5. Results for the Emulation of the LIF Neuron Based on the Memristor That Is Designed with Each OTA Topology

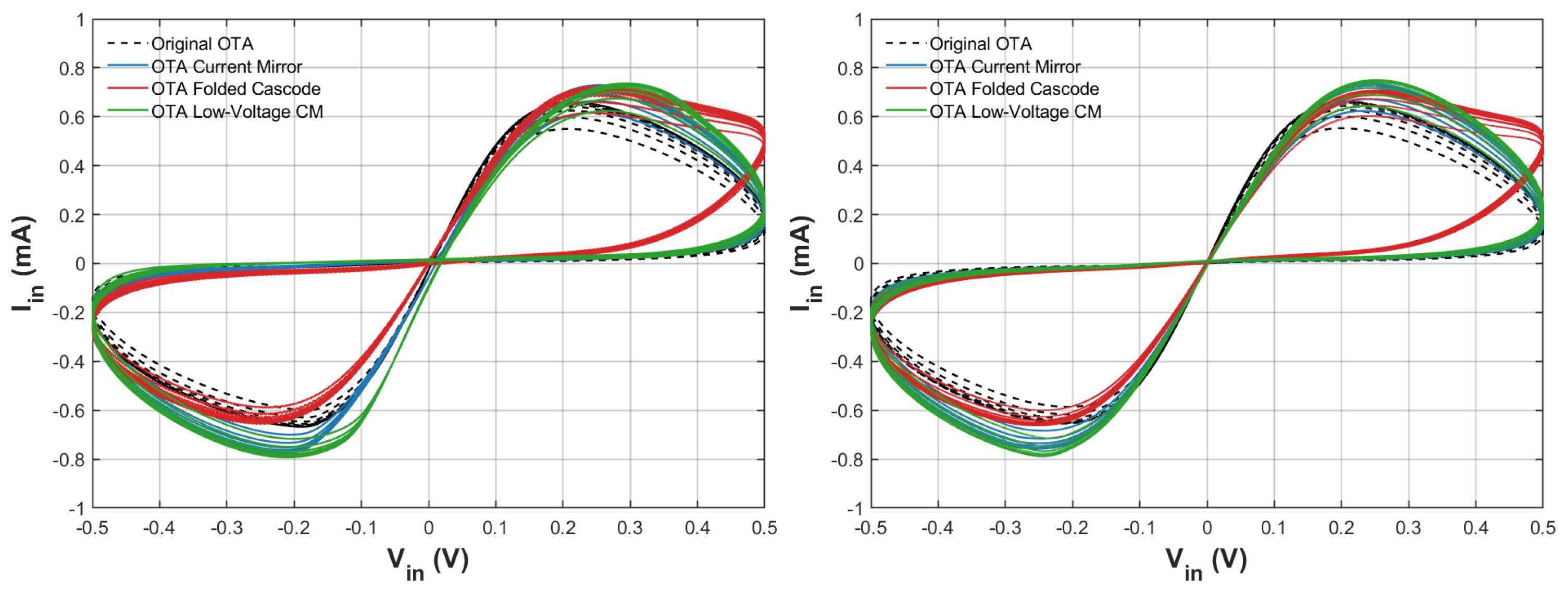

To verify the optimal sizing results given in Table 7, and shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, it is necessary to obtain hysteresis curves of the memristor emulator shown in Figure 6. The characteristic curves shown in Figure 17 demonstrate the optimized OTAs’ performance in memristive emulation applications, where the pinched hysteresis loops reveal critical insights about the nonlinear memristive emulation response and its dependence on transconductance properties.

Figure 17.

Comparison of hysteresis loop using the different OTA topologies for the memristor emulator: 1 MHz (left) and 100 kHz (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

The LIF neuron shown in Figure 5 is now simulated by using the sizes given in Table 9, and also by using the memristor emulators implemented with the three different OTA topologies. The input signal amplitudes must be at least equal to the threshold voltage of transistor TN1 to ensure proper activation. Therefore, an amplitude of 0.5 V is selected, consistent with the choice reported in [13]. To select an appropriate signal period, it is necessary to consider the time constant associated with the relationship. Using these values, the frequency is calculated as kHz which corresponds to a period of 3.92 s. This interval is the minimum time for observing the integration process in the neuron. However, for visualization and practical purposes, a frequency of 100 kHz is selected, equivalent to a period of 10 s with a duty cycle of 40% to meet the time condition.

Table 9.

Transistor dimensions for the spiking neuron shown in Figure 5.

Similarly, the time constant associated with is analyzed, yielding Hz which corresponds to a period of ms, necessary to observe the complete firing cycle of the neuron. Nevertheless, to clearly visualize the contribution of the memristor emulator and the resulting change in the burst firing frequency due to the memristive reset module, the period is set to 5 ms with a duty cycle of 30%.

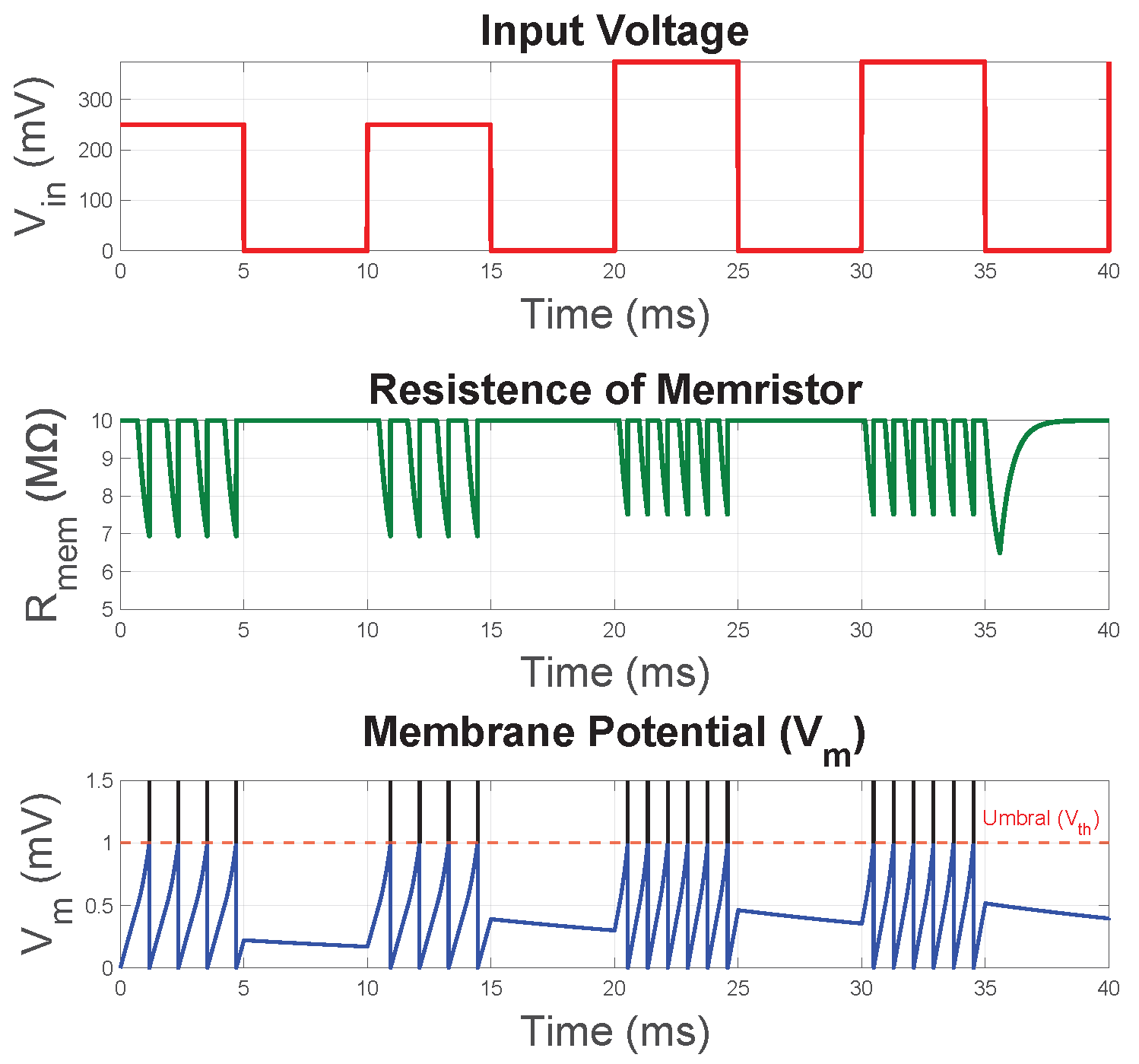

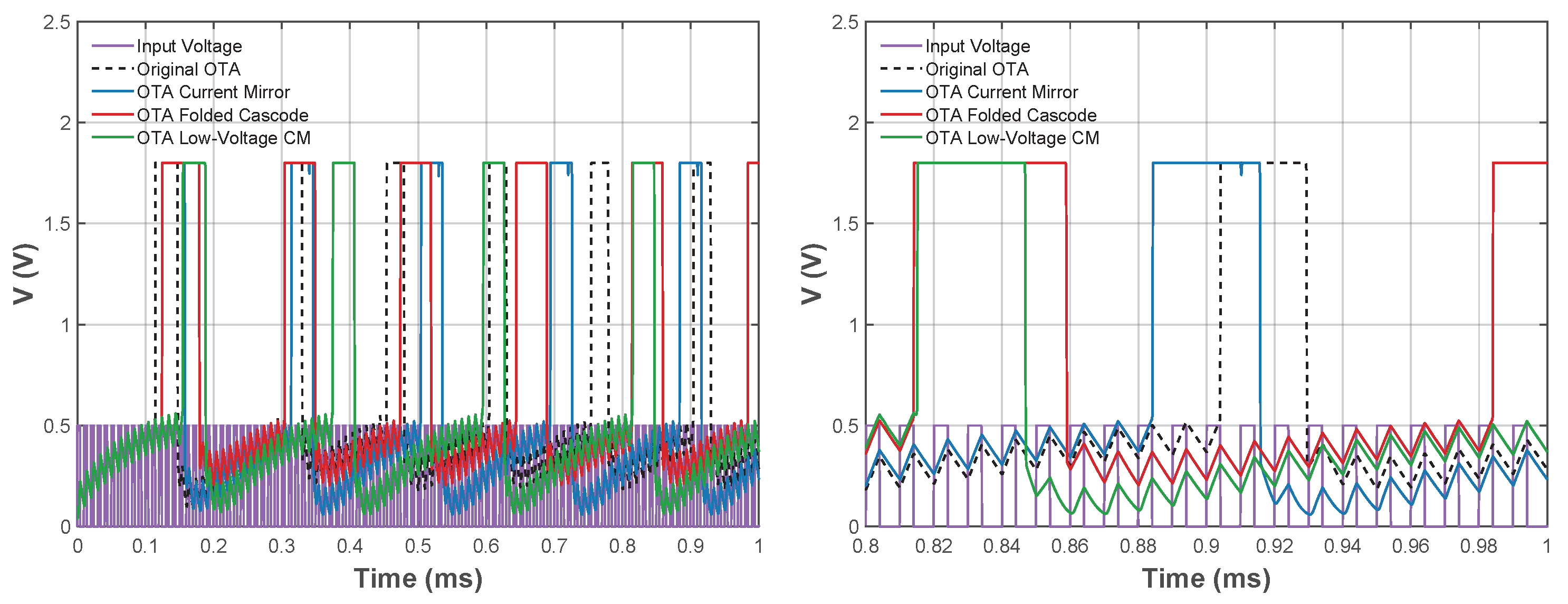

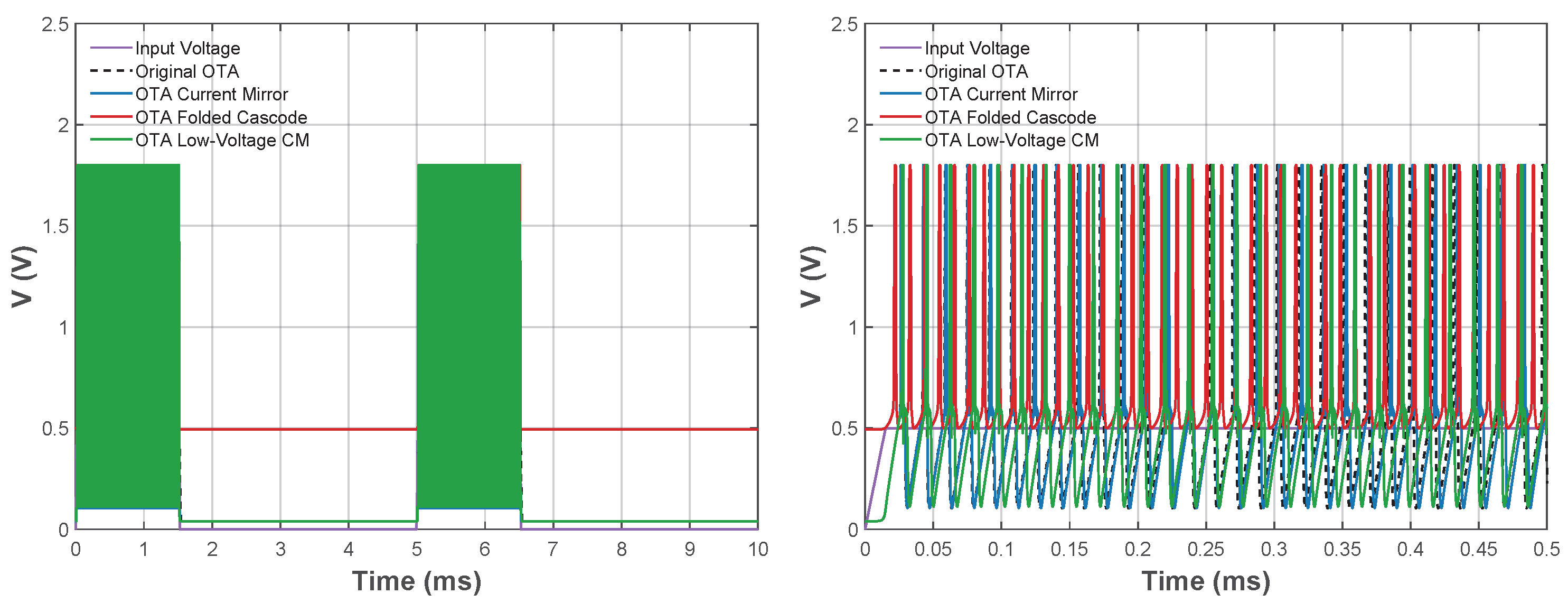

The initial results are shown in Figure 18 and Figure 19, which use the sizes of the CMOS inverter given in Section 3 (with pF and nF). In the figures it can be appreciated that during the period T = 10 s the three OTA topologies generate different numbers of spikes under identical simulation conditions. This indicates that the transconductance behavior directly affects the memristor emulation stable states and can slow down or speed up the signal.

Figure 18.

Comparison of temporal response using the different OTA topologies for the LIF neuron with T = 10 s and W initial values of the CMOS inverter: normal view (left) and zoom view (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

Figure 19.

Comparison of temporal response using the different OTA topologies for the LIF neuron with ms and W initial values of the CMOS inverter: normal view (left) and zoom view (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

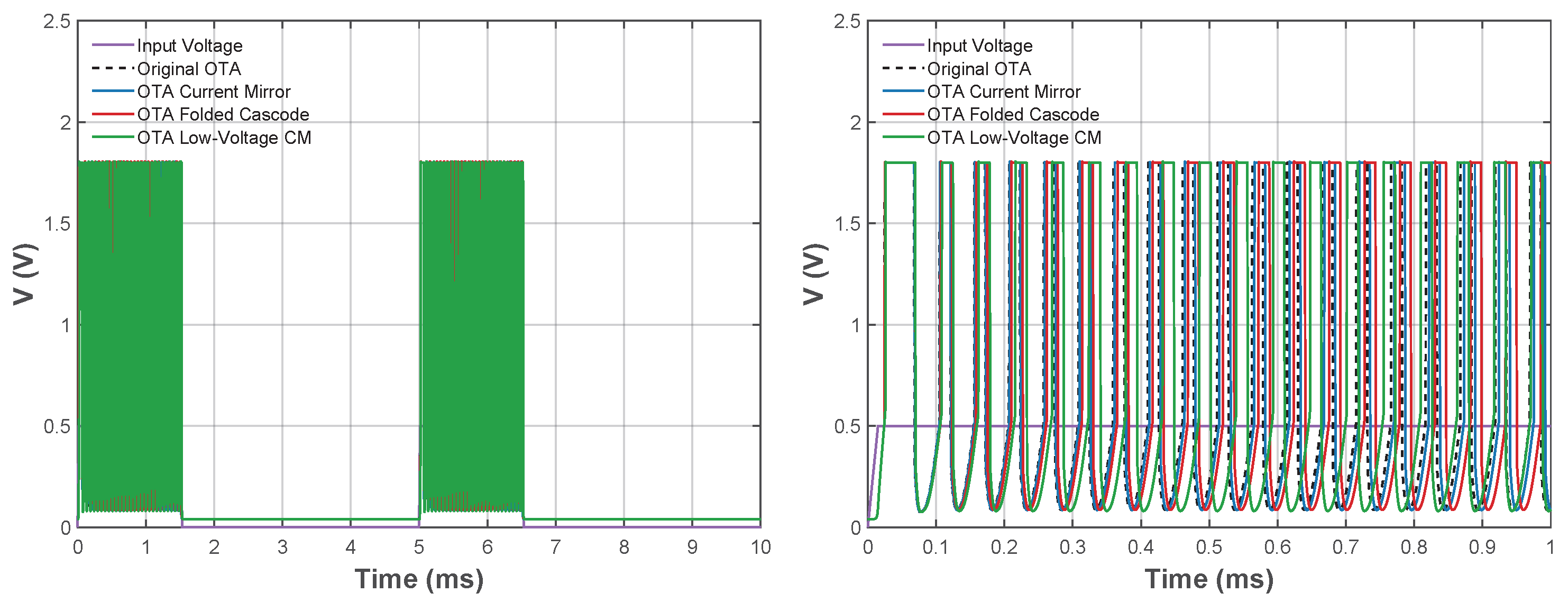

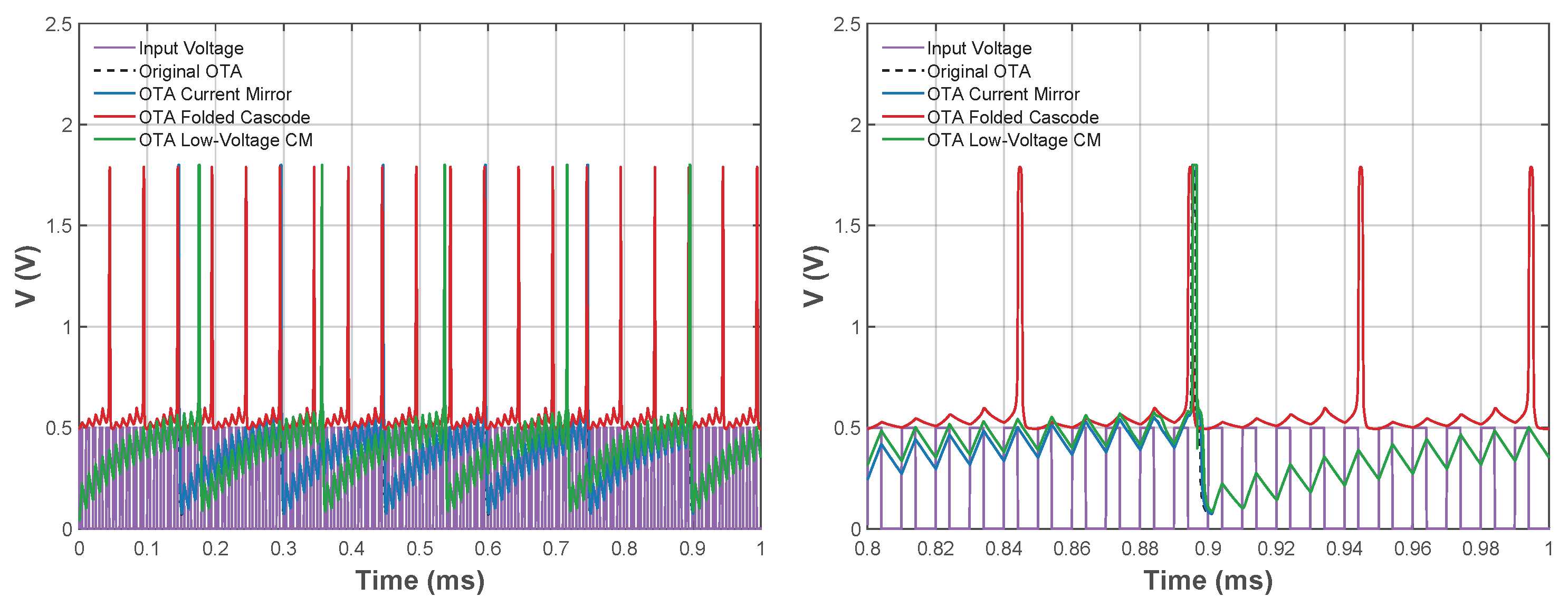

To assess frequency modulation induced by the memristor emulator, now the CMOS inverter embedded in Figure 6, is resized by considering 100 times the initial W values: m, m, and m. The simulation results are presented in Figure 20 and Figure 21, where the differences between the topologies can be observed. However, to enable a more quantitative comparison, the energy consumption per spike was computed using Equation (12),

where N denotes the number of spikes occurring within the evaluation interval T.

Figure 20.

Comparison of temporal response using the different OTA topologies for the LIF neuron with s and 100 times the W initial values of the CMOS inverter: normal view (left) and zoom view (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

Figure 21.

Comparison of temporal response using the different OTA topologies for the LIF neuron with ms and 100 times the W initial values of the CMOS inverter: normal view (left) and zoom view (right). Dashed line for Original OTA is referred to the topology taken from [13] in this work.

Table 10 summarizes the energy consumption values over the period ms for the neurons implemented with the CMOS inverter of the memristor emulator, using both the initial W values and the scaled values (100 × the initial W). According to Equation (12), the energy consumption is obtained by integrating the current over the pulse duration, multiplying the result by , and dividing by the number of generated spikes; this yields the energy consumed per spike.

Although the optimized OTAs do not match the energy consumption reported in the original work [13], the results show that adjusting the transconductance enables control over the firing frequency of the LIF neuron. The table also reports the area occupied by each neuron without capacitor dimensions, which is generally larger than that of the original design in [13], consequently affecting overall energy consumption. It is important to note that the transconductance linearity optimization performed in this work required oversizing certain transistors, making direct power- and area-related comparisons with [13] less favorable. Nevertheless, when comparing the symmetry of transconductance, this work demonstrates a clear improvement over [13].

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the linearity of the transconductance can be effectively optimized while maintaining acceptable performance parameters such as gain and bandwidth, as well as improving offset response and phase margin. However, achieving this level of linearity requires biasing the transistors in strong inversion, which has a direct impact on energy consumption.

Modifying the transconductance of an OTA influences both the symmetry of the CMOS-based memristor emulator and the dynamic evolution of the LIF neuron. As illustrated in Figure 21, the width of each spike is affected by the high-time duration of the signal, indicating that the firing frequency is directly determined by the transconductance value. This implies that different configurations can be used to obtain characteristic bursting frequencies.

Furthermore, the OTA topologies explored in this work were successfully optimized using the hybrid method in combination with the NSGA-II algorithm with Python 3.11.9 and open-source tools (PDKs).

By combining automated OTA optimization with strategic transistor scaling, this work establishes a co-design framework for tuning neuromorphic dynamics. The findings enable energy-efficient spiking neuron implementations where firing rates can be adjusted for specific applications. Future research should explore large-scale neuronal arrays and advanced-node implementations to further validate scalability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.V.-M. and E.T.-C.; methodology, L.H.-M.; software, C.A.V.-M. and L.G.d.l.F.; validation, C.A.V.-M., L.H.-M., E.T.-C. and L.G.d.l.F.; formal analysis, C.A.V.-M.; investigation, C.A.V.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.V.-M.; writing—review and editing, L.H.-M., E.T.-C. and L.G.d.l.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Carlos Alejandro Velázquez-Morales would like to thank SECIHTI /México for the scholarship 4071010 to pursue a PhD degree at INAOE.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maass, W. Networks of spiking neurons: The third generation of neural network models. Neural Netw. 1997, 10, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Vo-Ho, V.K.; Bulsara, D.; Le, N. Spiking Neural Networks and Their Applications: A Review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.D.; Carvalho, M.; Carneiro, D.; Cardoso, J.S. Spiking Neural Networks: A Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 60738–60764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, L.; Buscarino, A. Spiking Neuron Mathematical Models: A Compact Overview. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, W.B.; Long, J.Y.; Xue, T.h. Research Progress of spiking neural network in image classification: A review. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 19466–19490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, M.; Singh, A.; Kumar, S. Design of a VDBA-Based Memristor Emulator and Its Application for Bio-Sensing Through Instrument Amplifier. IEEE Open J. Nanotechnol. 2025, 6, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Meng, J.; Jin, B.; Wang, T. Low-Power Memristor for Neuromorphic Computing: From Materials to Applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Gan, L.; Guo, X. Memristor-based spiking neural networks: Cooperative development of neural network architecture/algorithms and memristors. Chip 2024, 3, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, W.; Kistler, W.M. Spiking Neuron Models: Single Neurons, Populations, Plasticity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, U.; Akram, M.W.; Prasad, D.; Islam, A. An energy and area-efficient spike frequency adaptable LIF neuron for spiking neural networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 119, 109562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepthi, M.S.; Shashidhara, H.R.; Rudraswamy, S.B. Simulation-based effective comparative analysis of neuron circuits for neuromorphic computation systems. Neurocomputing 2025, 614, 128758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besrour, M.; Zitoun, S.; Lavoie, J.; Omrani, T.; Koua, K.; Benhouria, M.; Boukadoum, M.; Fontaine, R. Analog Spiking Neuron in 28 nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the 2022 20th IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference (NEWCAS), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 19–22 June 2022; pp. 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ranjan, R.K.; Kang, S.M. A Memristor Emulation in 180-nm CMOS Process for Spiking Signal Generation and Chaos Application. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handkiewicz, A.; Krzywoszyja, G.; Zajac, W.; Naumowicz, M. Filter Design Based on Multi-port and Multi-dimensional gC Circuits. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 44, 4511–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonthaputha, T.; Kumngern, M.; Thepnarin, N. A Simple and Accurate CMOS Sample-and-Hold Circuit Using Dual Output-OTA. Przeglad Elektrotechniczny 2020, 96, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başak, E. Precision Analog Rectifiers with Current Input-Current Output Topologies: A Comprehensive Study. Electrica 2025, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhu, Z. A 16 kHz-BW 93.1 dB-SNDR DT 2-1 MASH ADC with Cascading-CLS Technique for Accelerometer Measurement Applications. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Kang, G.G.; Lim, G.W.; Kim, H.S. A Display Source-Driver IC Featuring Multistage-Cascaded 10-Bit DAC and True-DC-Interpolative Super-OTA Buffer. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2024, 59, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.N.; Srivastava, G.; Arshad, S.S.; Shukla, S. A CMOS low pass filter based on improved current mirror for biomedical application. J. Opt. 2025, 54, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, F.; Martínez, S.; Dieck, G.; Rossetto, O. An Ultra-Low Voltage High Gain Operational Transconductance Amplifier for Biomedical Applications. 2007. Available online: https://in2p3.hal.science/in2p3-00192566v1 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Ghosh, S.; Bhadauria, V. An ultra-low-power bulk-driven subthreshold super class-AB rail-to-rail CMOS OTA with enhanced small and large signal performance suitable for large capacitive loads. Microelectron. J. 2021, 115, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespers, P.G.A.; Murmann, B. Systematic Design of Analog CMOS Circuits: Using Pre-Computed Lookup Tables; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, R.; Kumaradhas, E.B.; Arun, S. Design of Second Order Low Pass Filter Using Inverter-Based CMOS Operational Transconductance Amplifier (OTA) Through gm/ID Methodology. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference of Electron Devices Society Kolkata Chapter (EDKCON), Kolkata, India, 30 November–1 December 2024; pp. 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Liang, F.; Bäck, T.; Wang, H. A Multi-Form Optimization Framework for Analog Integrated Circuit Sizing. In IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 72, pp. 7095–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aueamnuay, C.; Kayyil, A.V.; Thota, N.B.; Venkatachala, P.K.; Allstot, D.J. gm/ID-Based Frequency Compensation of CMOS Two-Stage Operational Amplifiers. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Sevilla, Spain, 10–21 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Sanabria-Borbon, A.C. Optimising operational amplifiers by evolutionary algorithms and gm/Id method. Int. J. Electron. 2016, 103, 1665–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, J.; Deb, K. Pymoo: Multi-Objective Optimization in Python. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 89497–89509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lberni, A.; Sallem, A.; Marktani, M.A.; Masmoudi, N.; Ahaitouf, A.; Ahaitouf, A. Influence of the operating regimes of MOS transistors on the sizing and optimization of CMOS analog integrated Circuits. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2022, 143, 154023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Sindhya, K.; Okabe, T. Self-adaptive simulated binary crossover for real-parameter optimization. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation (GECCO ’07), London, UK, 7–11 July 2007; pp. 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).