Abstract

Diffusion on curved surfaces deviates from the flat case due to geometrical corrections in the evolution of its moments, such as the geodesic mean square displacement. Moreover, anomalous diffusion is widely used to model transport in disordered, confined, or crowded environments and can be described by a temporal subordination scheme, leading to a time-fractional diffusion equation. In this work, we analyze the dynamics of time subordinated anomalous diffusion on curved surfaces. By using a generalized Taylor expansion with fractional derivatives in the Caputo sense, we express the moments as a temporal power series and show that the anomalous exponent couples with curvature terms, leading to a competition between geometric and anomalous effects. This coupling indicates a mechanism through which curvature modulates anomalous transport.

1. Introduction

How particles move and diffuse in complex environments remains one of the most interesting problems in non-equilibrium statistical physics: microscopic transport rarely occurs in flat, uniform spaces, and is almost always influenced by geometry, interactions, crowding, and memory. Brownian motion is a common denominator across multiple domains, ranging from colloidal systems in biological physics [1,2,3,4] to modern physics and finance [5,6,7,8,9]. Since the last twenty years, research has increasingly focused on the description of diffusion processes in curved geometries, from measurements, experiments and simulations [10,11,12,13] to mathematical modeling [14,15,16,17,18] and simulations [19,20,21,22,23,24]. The irregular movement of a protein or lipid in the bilayer is not simply ideal Brownian motion, it is influenced by collisions, obstacles, and interactions mediated by the cell’s internal environment, thickness, etc. In addition, the membrane itself is not rigid: thermal fluctuations generate surface ripples, making the surface geometry involved in diffusion dynamic, non-planar, and complex [25,26,27,28,29]. Together, curvature, local complexity, and thermal noise make it natural to ask how diffusion changes when the geometric character of the space where it occurs is taken into account.

Diffusion on a curved surface is studied by expressing the Laplacian in the manifold’s coordinates, yielding the so-called Laplace–Beltrami operator, a covariant operator that describes the surface’s geometry. The formal solution to the diffusion equation on curved manifolds has been studied by various authors using the heat kernel method. In this approach, the kernel is represented as a power series [30,31], though calculating its coefficients can be quite challenging [32,33,34]. For instance, in Ref. [15], Balakrishnan derived a solution applicable for very small time values, which has a direct impact on the dynamics of diffusing particles. In [17], it was shown that diffusion, characterized by the mean square displacement, slows down with positive curvature and accelerates with negative curvature at short times.

In some systems, the environment’s complexity significantly influences the dynamics [35]. A common mechanism for modeling this phenomenon is anomalous diffusion, in which the mean-squared displacement scales as a power law of time [36]. Anomalous behaviors have been described using fractional derivatives, for which there are many alternative definitions [37]. Fractional generalizations of the Laplacian on curved manifolds have been studied in different contexts, typically by extending the spectral Laplacian to manifolds [38]. For instance, the fractional porous medium equation has been analyzed on manifolds with conical singularities [39,40] as well as in inverse problems on compact manifolds [41], where the observed behavior is mainly superdiffusive [42]. Also, the problem of fast diffusion has also been addressed on non-compact manifolds [43]. Anomalous subdiffusion has been observed in the motion of proteins within cell membranes [10,44,45,46,47] and in crowded liquids [48,49], and is usually modeled using time-fractional derivatives of fractional order. A practical and elegant way for introducing time-fractional derivatives is the subordination method [50,51]. In this approach, the physical process in the spatial domain evolves in physical time, which, in turn, depends on operational time, thereby capturing the effect induced by the medium’s complexity [47].

In this work, we precisely adopt the following twofold perspective. On the one hand, we consider a series expansion of the statistical observables, which shows that curvature explicitly manifests in their coefficients and, therefore, allows us to trace the impact of geometry on dynamics directly. On the other hand, we extend this framework to scenarios with memory by introducing temporal subordination, which naturally leads to fractional operators in time. In this way, we can analyze how temporal orders and coefficients in Taylor series are coupled when the spatial curvature is combined with a nonlinear internal clock, modeling the effects of the complex environment.

The article is structured as follows: In Section 2, we review the classical formalism of Brownian diffusion on curved manifolds in Riemann normal coordinates and recover the expansion for statistical moments governed by the Laplace–Beltrami operator. In Section 3, we incorporate temporal anomalies via subordination and Caputo fractional derivatives, yielding a time-fractional diffusion equation on the surface. In Section 4, we apply the fractional version of Taylor’s theorem and identify how the temporal orders and coefficients in the series are reshaped when curvature and the fractional exponent are combined. Finally, in Section 5, we evaluate these results using specific examples and extract robust patterns that allow us to better understand the interaction between geometry and the fractional exponent in diffusive processes.

2. Laplace–Beltrami Diffusion in Riemann Normal Coordinates

The unbiased concentration of Brownian particles on curved surfaces can be obtained by solving the following diffusion equation [15,16,17]

where on the right-hand side the so-called Laplace–Beltrami operator appears, D is the constant diffusion coefficient and are the coordinates of a point on the n dimensional spatial manifold where the diffusion process takes place; is its inverse metric, and g is its determinant, and a localized initial condition is assumed . One can use different methods to solve the diffusion equation with the Laplace–Beltrami operator [32,33,34]. For example, for a sphere, it is easy to obtain using the usual method of separation of variables [21]. In the general case, the formal solution can be obtained as a short-time expansion whose coefficients depend on the surface’s curvature [15]. For obtaining the dynamics of moments, in the standard case, it is necessary to integrate the solution of Equation (1) by powers of the geodesic distance. However, in [17], an alternative method was proposed for finding these dynamics for any function defined on the given manifold.

Next, we will review this method and calculate the short-time expressions of two of the most relevant moments.

Short-Time Expansion of Moments

Let us consider a scalar function defined on the curved manifold, representing some relevant physical or statistical observable, and well-behaved under successive applications of the surface Laplacian. The expected value of this function is given by:

here is the curved surface where the diffusive process evolves and then, the concentration follows the Laplace–Beltrami Equation (1). Therefore, can be Taylor-expanded around the initial time,

hence, we require an expression for the corresponding time derivatives at . In Ref. [17], an expression for the evolution of the expected values of was obtained. First, differentiating both sides of Equation (2) with respect to time, we see that only the density is affected, so that it can be replaced by the Laplace–Beltrami operator. We can rewrite the product as

where is a boundary term that depends only on density and its gradients; boundary terms will be neglected since we assume that the probability distribution and its derivatives decay quickly or vanish at the boundary. Consequently, the time derivative of the expected value of can be obtained as the expected value of ,

From this expression, we can iteratively find all temporal derivatives of by neglecting the boundary terms,

Accordingly, we can rewrite the Taylor series coefficients in (3), evaluated at by substituting the initial condition into the expected value on the right-hand side of Equation (5). Then, the k-th application of the Laplace–Beltrami operator on is evaluated at the initial point , and thus, the series becomes

For practical use of relation (6), truncations at lower orders can be made

Such truncation will be valid whenever the lower-order term dominates the next-order term. First, we need to choose the scalar function and establish a procedure for evaluating successive applications of the Laplacian. Then, we will explicitly compare the terms obtained at consecutive orders to verify the previous condition.

For diffusive processes, it is important to calculate the moments, so , with , where s is the geodesic distance , so the formal series of the geodesic mean squared displacement (MSD) about reads as follows

To calculate successive applications of the Laplace–Beltrami operator to polynomial functions , we need to approximate the metric around the initial point . For this purpose, we will use the well-known Riemann Normal Coordinates [52], which are characterized by specific conditions and . A Taylor expansion for the metric about can be found in terms of the Riemann tensor The expansion in Riemann Normal Coordinates is valid only in a neighborhood of and not on the entire manifold. There, the metric tensor can be expressed in terms of curvatures, specifically the contractions of the Riemann tensor and its covariant derivatives. In this way, the second order in expression (8) can be written in terms of the Ricci scalar or Gaussian curvature , evaluated at the initial point, yielding the following for n-dimensional manifolds

The first correction to the behavior on a flat surface is of order , where the coefficient is the Gaussian curvature of the surface evaluated at the origin. To guarantee consistent truncation, the first term must lead over the second. This condition holds in the time regime , which represents the time needed to explore the surface by diffusion. This condition can be achieved either by taking sufficiently short times, small curvatures, or low diffusivities. These different physical scenarios are important to consider when designing experimental setups.

A study reported in [53] analyzed the trajectories of polystyrene nanoparticles as they diffused on the highly curved interface between water and silicone oil. Authors found that the second-order expression for the geodesic mean-squared displacement, obtained by Castro-Villareal [17], accurately describes the experimental data and allows for obtaining the diffusion coefficient. Remarkably, the authors observed that as the size of the oil droplet decreases, the diffusion process slows down significantly compared to larger droplet surfaces, providing evidence of a significant effect of curvature on dynamics. Recent experiments [54] have also found that the dynamics of anisotropic colloidal platelets on curved surfaces are subdiffusive, even on small to intermediate time scales. Although the main cause of this slowdown is the surface curvature, the deviation from standard diffusion is also attributed to the combined effects. However, these results raise interest in studying cases where diffusion is intrinsically anomalous.

For interfaces, biological membranes, or real porous media, we need to carefully consider the geometric, structural, and experimental observational conditions, since these determine different possible outcomes. For example, when measuring the mean square displacement, [55] distinguishes three kinds: the geodesic, studied here; the Euclidean, which considers that the surface is embedded in a higher-dimensional space; and the projected, whose measurement depends on the viewing angle.

For certain functions, occasionally the scalar curvature vanishes, and it is necessary to consider higher-order terms in the formal series, which would introduce not only curvature but also its gradients. In this study, we will focus on lower-order corrections to analyze the initial effects of curvature on moments. For experimental verification, higher-order corrections can improve accuracy, allowing us to distinguish between different measurements [53,54,55]. We will later provide an example that allows us to glimpse the validity of the approximation.

Now, we compute higher-order moments by means of expression (6). We obtain the fourth geodesic moment by selecting the scalar function . To perform this calculation, we need to apply the Laplace–Beltrami operator multiple times, as required by the corresponding series

Following the procedure in [17], the first application of the Laplace–Beltrami operator was performed by splitting the products with the contracted metric, which is replaced by a , and the term of derivatives of the logarithm of g. This yields

this term vanishes at the origin of the Riemann normal coordinates; therefore, higher-order terms must be considered. When we apply Laplace–Beltrami operator once again, we observe that the complexity increases rapidly. Thus, we grouped the terms as mentioned previously: on the one hand, we separated the terms with powers of , and on the other hand, we consider the terms that contain functions of the logarithm of the metric. This approach yield the following

The only term that survives in the evaluation is the first one; also, even though the fourth term has not yet been fully expanded, it vanishes in the evaluation as it is multiplied by . To obtain an additional correction in series (10), we applied once more. This time, we encountered several terms, and after expanding the logarithm of g, we only report the relevant surviving term. The Taylor expansion of the logarithm of the determinant of the metric , up to fourth order is written in terms of Riemann tensor contractions and derivatives [17,52]:

By substituting the logarithm with powers of , the calculation of derivatives becomes simpler, and the term that remains in the evaluation is as follows:

Finally, the leading corrections at the fourth moment are of order , with coefficients that depend on the dimension and the scalar curvature.

Kurtosis describes the shape of a distribution, particularly focusing on the weight of its tails and the concentration around the mean, and is also an interesting statistical quantity to calculate. It is especially useful for identifying deviations from the Gaussian distribution and is a valuable tool in the study of anomalous diffusion, as it allows the detection of heterogeneities and long jumps. It can be defined in a dimensionless way using the standard deviation as a characteristic scale

Here, it is possible to calculate the lower-order corrections using the previous series (9) and (16), which will also approximate consistently within short times.

By expanding the denominator, calculating the product, and truncating up to the second order in time, we obtain

In the fourth section, we will recalculate the three key magnitudes that characterize the underlying statistics, now assuming that the evolution over time follows a subordinate process that we introduce in the next section.

3. Time-Fractional Diffusion and Subordination

A particle moving in crowded or complex environments often experiences overdamped motion, slowing down its dynamics. Among the various models used to address these dynamics, anomalous diffusion is characterized by a power-law time dependence in the mean-squared displacement [36,51,56]. These processes have been studied using fractional derivatives, which appear in several contexts, including the continuous-time random walk model with long tail waiting times [57,58], highly restricted domains such as comb structures [59,60], also when modeling a particle moving in a viscous medium with the fractional Langevin equation [61], and when there is a time-dependent diffusion coefficient such as in scaled Brownian motion [62,63,64], along with many other systems.

We will consider the subordination scheme to introduce fractional derivatives. Let us consider that the physical process on the surface evolves in physical time t, which intrinsically depends on the operational time . This dependence models the slowing effects of motion due to possible complex surface structures.

The physical time and the operational time are connected by , i.e., is a stochastic process; specifically, is a Lévy stable noise with index , and then is an -stable motion. Then, to obtain the particle distribution function on the surface over physical time, it is necessary to integrate over the entire operational time interval, weighted by the subordination function, which is defined as For the -stable process, the subordination function is given by the H-Fox function, which corresponds to a one-sided Lévy stable distribution. Therefore, the particle distribution on the surface in the physical time is given by

We can obtain the evolution of the particle distribution function on the surface in physical time from the evolution equation of . Specifically, let us consider the surface diffusion Equation (1), now evolving in the operational time , with having the proper units. We can substitute the left-hand side of this expression by calculating the time derivative of in (20), which only affects . To determine the derivative of the subordination function in physical time, we can calculate it in the Laplace space of t, which is well known for the Lévy process.

where s is the Laplace variable of t. We compute the derivative and its corresponding Laplace inverse:

where the Riemann–Liouville integral was introduced. By inverting the operator in (22), we obtain the subordination function, and thus its derivative in physical time can be calculated as follows

where we introduce the Riemman–Liouville fractional derivative [37,60] satisfying . By integrating in parts Equation (20) and replacing with the Laplace–Beltrami operator for the diffusion on the surface, then the equation becomes

which can be rewritten in terms of the Caputo fractional derivative [37,60]

where the Caputo operator is defined as . The expression (25) has the advantage that the right-hand side, i.e., the term on the surface, remains unaffected by the subordination process. This fact allows us to apply the method described in the previous section to analyze the evolution of the scalar functions on the surface, especially the moments.

4. Curvature Effects on Short-Time Fractional Dynamics of Moments

Let us consider a diffusive process that occurs on a curved surface, governed by Equation (25). There are several methods for solving this equation, including exploring formal solutions and eigenfunction expansions [65]. However, this paper aims to study the dynamics of moments, following the approach carried out in [17]. A detailed study of its solutions will be addressed elsewhere. Then, let us consider a scalar function defined on the surface , where its expected value is defined by Equation (2) and is a function of physical time. However, since a fractional diffusion equation now governs the process, the Taylor expansion in (6) is not possible. Instead, we need to apply a version of Taylor theorem that incorporates a Caputo fractional time derivative. There are a number of different versions of the fractional Taylor theorem, and fortunately, a version with the desired characteristics was analyzed in Ref. [66] and is as follows: for a complex valuated function , the Generalized Taylor theorem reads

where , and . The previous definition has the advantage that for integer the standard derivative is recovered. Therefore, we propose the following expansion for the average of the scalar function on the surface:

When applying Caputo’s derivative to in (2), we observe that it only affects the distribution function, so when substituting (25), the right-hand side remains the same as in Equation (4). Consequently, the coefficients of this series can be rewritten in terms of integer applications of the surface Laplace–Beltrami operator acting on the scalar function

Hence, the series becomes

We remark here that the terms are identical to the previous case. When we consider the expansion in Riemann normal coordinates, these terms ultimately depend on curvature and dimension. Additionally, the generalized Taylor expansion introduces modifications in both the powers of t and in the coefficients, now depending on the anomalous exponent .

In this way, for short times within this framework, we obtain a coupling between the effects of the subordination process, which models slowing effects reflecting the environment’s complexity, and local spatial geometric terms. In the standard case, corrections to moments were powers of t greater than one; however, the effect was not necessarily superdiffusive but instead depended on curvature. In the present study, subdiffusion is characterized by an anomalous exponent, and, depending on curvature, the retarding and confining effects of could be diminished, prevented, or even reversed within short times.

By selecting as , we obtain the geodesic MSD for subordinate anomalous diffusion

Replacing the previously calculated terms for the first and second application of the Laplace–Beltrami on , we get

he leading term reduces to the well-known case when . Using the series (29) we can calculate the dynamics of the fourth moment

and applying the coefficients already determined in (16), the result is

Finally, we can compute the kurtosis by expanding the series for short times of the quotient and truncating to the first relevant order, as in Equation (19). The anomalous exponent induces a non-zero coefficient for the lowest order term in t, whereas this does not occur in the standard case for , as we can see next

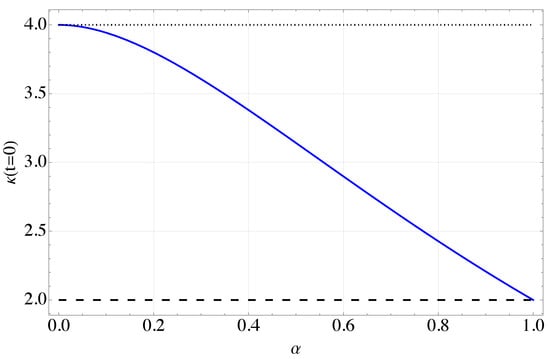

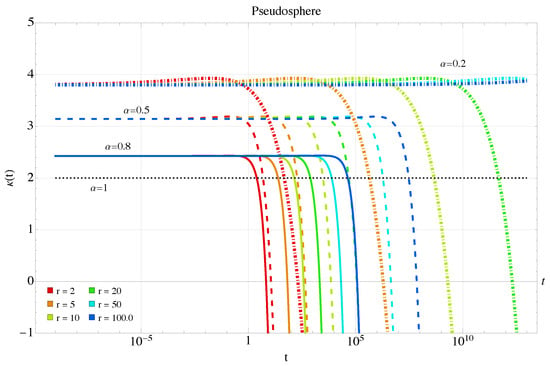

Furthermore, we observe that at and also when (i.e., no Gaussian curvature), the kurtosis coefficient depends on the anomalous exponent. In fact, for small values of , is close to twice the typical value when . The behavior in this case is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kurtosis coefficient for Equation (33) as a function of anomalous exponent , (blue solid line). Close to , the kurtosis value is twice that of the non-fractional case (dashed line).

5. Illustrative Examples

To illustrate how different curvature values influence short-time dynamics, we will consider three well-known surfaces: the sphere with positive curvature, the pseudosphere with negative curvature, and the torus, which features regions of positive, negative, and zero curvature, along with angular dependence.

The scalar curvature is defined in terms of the Riemann curvature tensor as follows

where

is the Riemann tensor in its standard form in terms of Christoffel symbols defined as metric derivatives

Then, given the metric, we can calculate the Gaussian curvature and find the coefficients of the short-time corrections on the moment’s dynamics.

5.1. Sphere and Pseudosphere

The metric of the sphere can be written as follows:

the corresponding scalar curvature is . The pseudosphere can be generated as a surface of revolution resulting from rotating a tractrix around an axis. Its metric is as follows:

where is the generating curve parameter such that the height is given by . The Gaussian curvature in this case is the negative of the sphere, i.e., . Although the pseudosphere is an open surface, it has a finite area and volume. This method provides a useful approximation for visualizing the effects of negative curvature, since calculating moments requires a bounded region or assumes rapidly decaying distributions, as established from the outset. On these two surfaces, the curvature is constant and entirely determined by the radius.

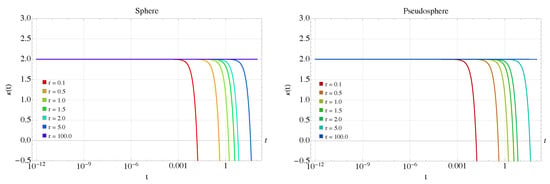

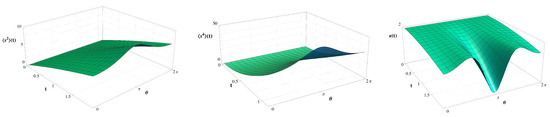

5.1.1. Normal Diffusion

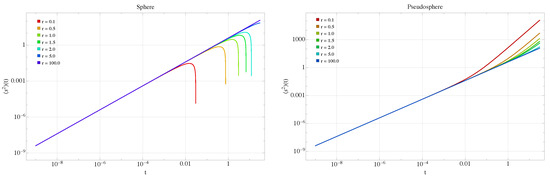

We can obtain the correction to the geodesic mean square displacement as a function of the radius in the case of normal diffusion by means of Equation (9). For these two surfaces, the geodesic mean square displacement is shown in Figure 2. For the sphere with large curvature (small radius), the correction is significant, and the behavior is considerably slower than in the standard case. As the radius increases, the geodesic MSD approaches the linear case, which is recovered at very large radii (negligible curvatures). The opposite occurs for the pseudosphere. For small radii, the curvature is negative and with large magnitude. In this case, the correction term accelerates the diffusive behavior, resembling superdiffusion. This effect decreases as the radius increases.

Figure 2.

Mean squared displacement Equation (9) for the sphere (left) and pseudosphere (right) for different radii, non-anomalous case, with .

Despite limiting ourselves to analyzing second-order corrections in this work, we can appreciate the accuracy of the curves by comparing the geodesic MSD in Equation (9) with the next-order approximation previously obtained in Ref. [17], whose expressions coincide and are as follows

We plot this expression in Figure 3 and observe that, for the sphere, the MSD decreases slightly across different radii, maintaining a qualitatively similar overall behavior. In contrast, for the pseudosphere, the third-order correction decreases relative to the second-order term. Although this correction may still be above the flat value, it decays rapidly in t, which is important to restrict to short times.

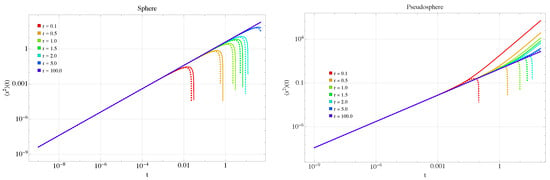

Interestingly, although the fourth moment Equation (16) is of quadratic order and the curvature correction is of cubic order, the behavior is qualitatively similar to that of the geodesic MSD. This means that, for the sphere, the fourth moment decreases relative to the flat case; the effect is more pronounced for smaller radii. In contrast, for the pseudosphere, increases as the radius decreases. This behavior is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Fourth moment Equation (16) for the sphere (left) and pseudosphere (right) for different radii, non-anomalous case, with .

In Equation (19) for kurtosis, the correction is quadratic in both time and curvature. This means that, regardless of the curvature’s sign, the correction for surfaces with the same magnitude of curvature will be identical. Figure 5 illustrates this for both the sphere and the pseudosphere. On a flat surface, the kurtosis is 2, but on the sphere and the pseudosphere, as the radius decreases, the kurtosis decreases rapidly with smaller radii on increasingly shorter time scales. Note that kurtosis cannot be negative, so the approximation is no longer valid in the negative regions shown in Figure 5. This occurs sooner for surfaces with smaller radii.

Figure 5.

Kurtosis Equation (19) for the sphere (left) and pseudosphere (right) for different radii, non-anomalous case, with .

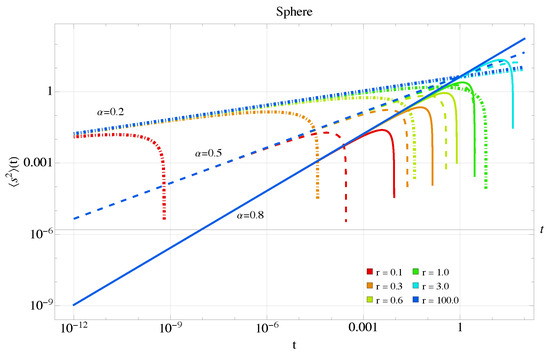

5.1.2. Anomalous Case

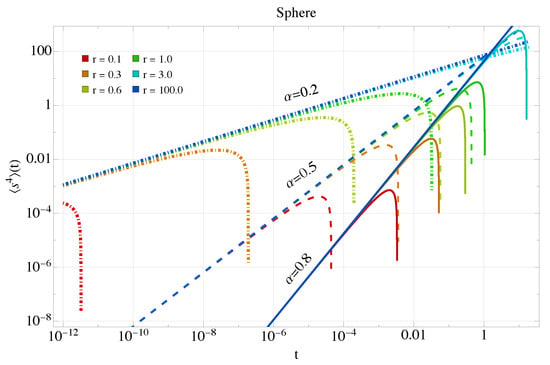

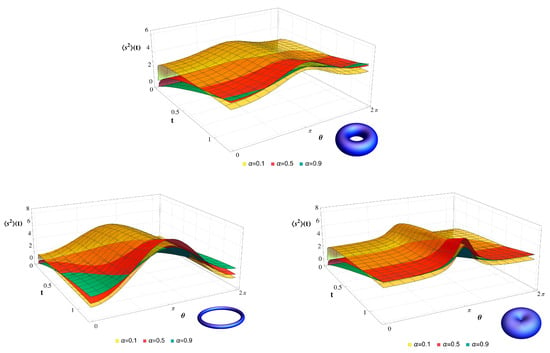

Now let us consider the case in which the mean square displacement contains anomalous diffusion effects and is therefore given by Equation (31). The short-time dynamics of the second moment are now dominated by the term of order . For the sphere the dynamics of can be seen in Figure 6, where the solid curves are for an exponent of 0.8, the dashed curves for 0.5, and the dotted curves for 0.2; the colors indicate changes in curvature, with blue colors representing small curvatures and red representing large curvatures. The effect of the anomalous exponent is to increase the geodesic mean-squared displacement at short times; curvature tends to diminish it with respect to the flat case of each exponent. We then observe a competition between the anomalous exponent, which tends to increase , and the curvature, which tends to decrease it.

Figure 6.

Mean squared displacement Equation (31) for the sphere in the anomalous case with . Colors ranging from red to blue indicate an increase in radius and a decrease in curvature. Solid curves indicate an anomalous exponent of 0.8, dashed curves for 0.5, and dotted curves for 0.2.

We also note that as time increases, the behavior of the anomalous exponent reverses: it slows the dynamics as becomes smaller, while the curvature continues to decrease it. In this case, it is important to remember that truncating the series is valid as long as the lower-order term dominates the next-order term. In this sense, the series coefficients are relevant time scales. For large radii, —the time required to explore the entire sphere through anomalous diffusion— can be theoretically very large for small , e.g., for a radius of 10 and , . These cases are described in Figure 7, and we plot long times to appreciate the effect. Notably, the subdiffusion effect is preserved in this case.

Figure 7.

Mean squared displacement Equation (31) for the sphere in the anomalous case with at longer times and smaller curvatures. Colors and dashing style as previous figure.

In Ref. [67], a fractional version of the generalized Langevin equation is studied, incorporating a memory term on the hypersphere. This approach allows exploration of the underdamped regime, which corresponds to a ballistic geodesic MSD, though the chosen fractional derivative modifies the standard behavior. For times shorter than , a subdiffusive MSD is found whose time exponent is related to the memory term and which coincides with the dominant term in our series (31). This case shows how subdiffusion can occur at intermediate times. With this approach, the authors derive an expansion similar to (30), which is valid for all times. However, the coefficients in their expansion depend on curvature only through and include a factor that incorporates memory through Mittag–Leffler functions, in contrast to the Gamma functions that appear in our case. The difference may be due to several reasons: on the one hand, the curvature of the sphere is constant, so the expansion in covariant derivatives of the Riemann tensor does not appear explicitly; on the other hand, it could be due to the series we choose in (26), since there are different possible definitions for it [66].

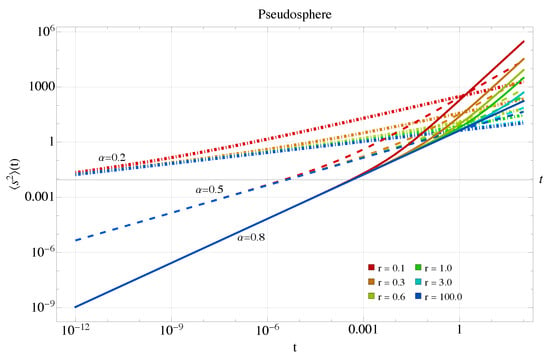

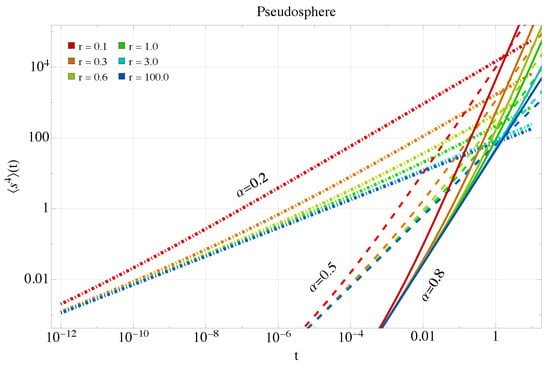

The geodesic MSD for the pseudosphere is shown in Figure 8. For both surfaces with large radii, the anomalous exponents tend to increase to as they decrease. However, the effect of curvature is now reversed relative to the sphere, and for increasingly large magnitudes of curvature, the geodesic MSD also increases. This indicates that negative curvature, coupled with the small exponent, accelerates the dynamics of , analogous to the superdiffusive case. For larger radii and longer times, Figure 9 shows that the process remains subdiffusive, but the trend is to increase the MSD.

Figure 8.

Mean squared displacement Equation (31) for the pseudosphere in the anomalous case. Colors and dashing style as in the previous figure.

Figure 9.

Mean squared displacement Equation (31) for the pseudosphere in the anomalous case at longer times and smaller curvatures. Colors and dashing style as in the previous figure.

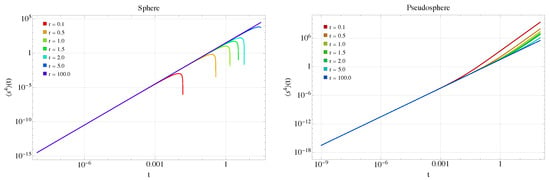

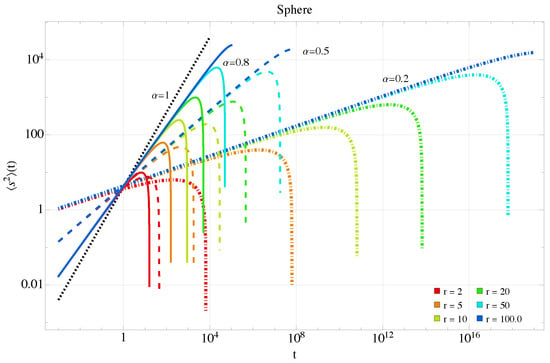

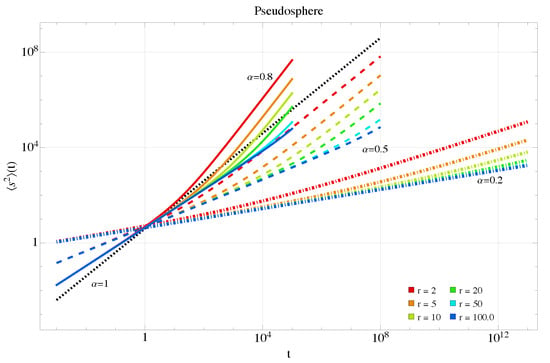

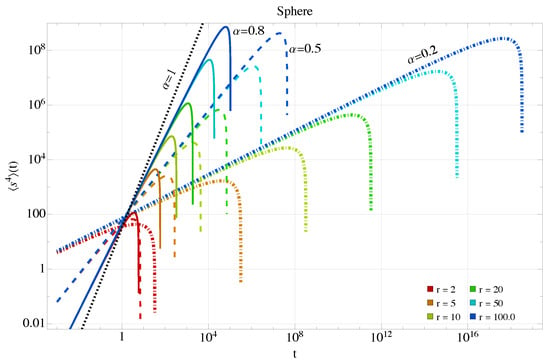

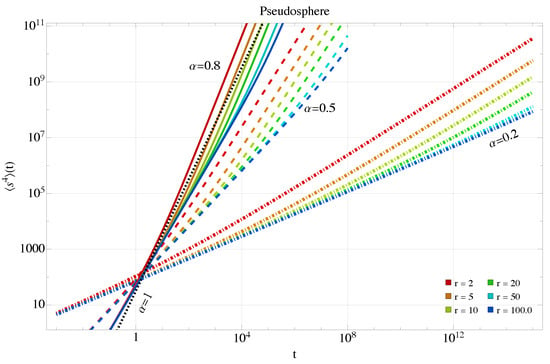

Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 show the evolution of the fourth moment in both surfaces. As previously observed in the standard case, the behavior on each surface is qualitatively similar to that of the geodesic MSD.

Figure 10.

Fourth moment Equation (32) for the sphere in the anomalous case. Colors and dashing style as in the previous figure.

Figure 11.

Fourth moment Equation (32) for the sphere in the anomalous case at longer times and smaller curvatures. Colors and dashing style as in the previous figure.

Figure 12.

Fourth moment Equation (32) for the pseudosphere in the anomalous case. Colors and dashing style as in the previous figure.

Figure 13.

Fourth moment Equation (32) for the pseudosphere in the anomalous case at longer times and smaller curvatures. Colors and dashing style as in the previous figure.

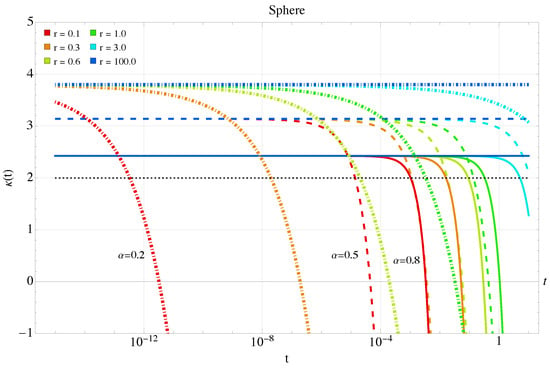

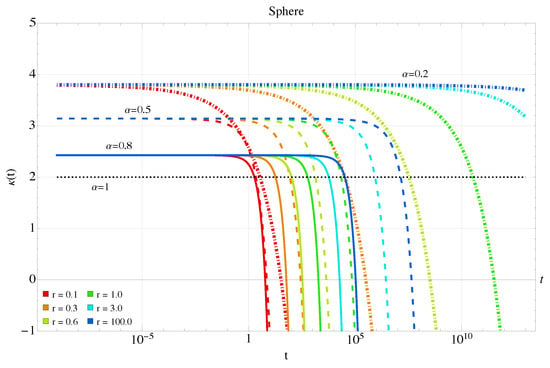

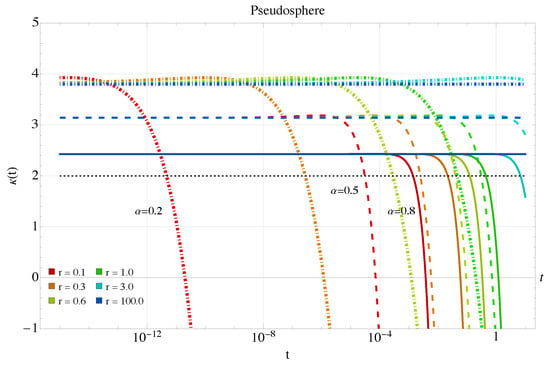

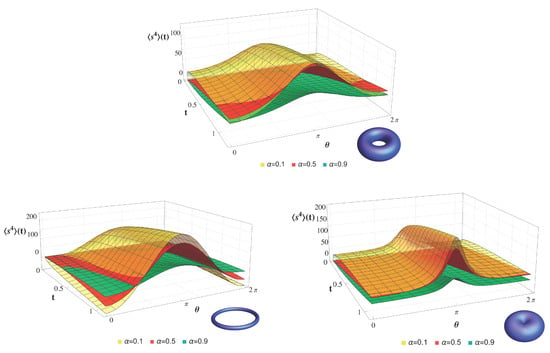

Finally, exhibits an interesting behavior as seen in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17. For large radii and , it reduces to 2, and as previously mentioned, for near-zero exponents, it doubles to 4. For the sphere, kurtosis decreases from its base value as the radius decreases. Remarkably, the correction term (33) is always negative, leading to a continuous decrease in kurtosis over time. We observe that for longer times and smaller curvatures, the behavior of the kurtosis is qualitatively similar to the previous case, as seen in Figure 15. For the pseudosphere, there is a regime where the linear term in the curvature is non-zero and dominates the correction, causing to exceed its base value. For small exponents, this is particularly significant. The kurtosis initially increases slightly before decreasing again as the quadratic curvature term becomes dominant. This trend indicates that the system’s dynamics are likely transitioning from a long-tailed to a short-tailed distribution. Similarly, for longer times and smaller curvatures, as shown in Figure 17, the behavior is the same.

Figure 14.

Kurtosis Equation (33) for the sphere for different radii, anomalous case.

Figure 15.

Kurtosis Equation (33) for the sphere for different radii at longer times and smaller curvatures, anomalous case.

Figure 16.

Kurtosis Equation (33) for the pseudosphere for different radii, anomalous case.

Figure 17.

Kurtosis Equation (33) for the pseudosphere for different radii at longer times and smaller curvatures, anomalous case.

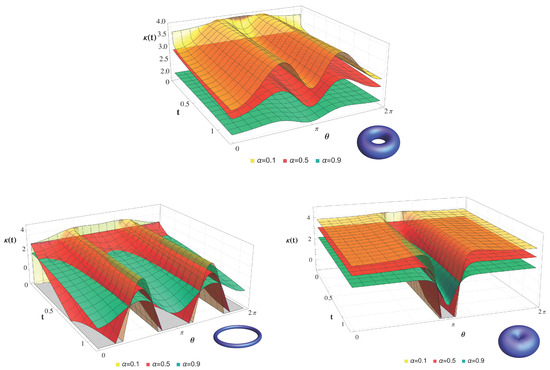

5.2. Torus

Consider the surface of a torus whose line element is given by , where a denotes the minor radius and R is the major radius. The scalar curvature for this surface exhibits an angular dependence,

indeed, for , the surface has positive curvature, for , it has negative curvature, and for , the curvature vanishes. It also depends on the aspect ratio or eccentricity . We can then calculate the geodesic MSD, the fourth moment, and the kurtosis in the standard case with Equations (9), (16) and (19), respectively. In Figure 18, we show these three quantities for a torus with an aspect ratio of .

The second and fourth moments are again qualitatively similar, both increase with time and show a maximum at , where the torus has its largest negative curvature. It is noteworthy that the MSD differs from that presented in Ref. [17] because we are only considering the lowest-order correction. The kurtosis starts at 2 and decreases over time for non-zero curvatures. Remarkably, in the negative curvature region, the decrease is more pronounced than in the positive curvature region, reaching a minimum at . This may suggest that the underlying distribution lacks long tails and that its weight has an angular dependence.

Now we consider the anomalous case of MSD, , and the kurtosis, given by Equations (31), (32) and (33), respectively. We plot temporal variation for different aspect ratios. The MSD increases for small ; this rise is very sharp for small eccentricity, , which corresponds to a very thin torus, or ring, as shown in Figure 19, where torus surfaces for each aspect ratio are shown in the bottom-right corner of each plot. For a thick torus with , we can see that the minimum of the negative curvature is more pronounced than in the case . We can also find that in all cases, the behavior of is reversed in the region of positive curvature and tends to decrease the MSD, with the effect being more pronounced for . The fourth moment is similar and is shown in Figure 20. We can also observe that for , the inversion effect on the dynamic behavior in the region of positive curvature is almost negligible, and the three surfaces do not overlap. As in previous cases, kurtosis is larger for small , where it is close to 4, while for close to one, kurtosis tends to 2. From this value, it decreases over time only in regions of non-zero curvature. This is clearly seen for the aspect-ratio torus in Figure 21. For eccentricities of , the kurtosis decreases very fast in the region of non-zero curvature and small exponents. For , varies very slightly in the region of positive curvature, but in the negative region it decreases very fast for small exponents. In this case, the distribution may show a transition from a long-tailed distribution characteristic of anomalous cases to a short-tailed distribution, induced by curvature and driven by the angle.

Figure 19.

Mean squared displacement Equation (31) for the torus with different aspect ratios (top), (left), (right), and anomalous exponents .

Figure 20.

Fourth moment Equation (32) for the torus with different aspect ratios (top), (left), (right), and anomalous exponents .

Figure 21.

Kurtosis Equation (33) for the torus with different aspect ratios (top), (left), (right), and anomalous exponents .

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we study the effect of surface curvature on diffusive processes with temporal subordination. We analyze the moments of the distribution, which satisfies the diffusion equation with the Laplace–Beltrami operator in the spatial part and the Caputo derivative introduced via the subordination method. In particular, we obtain the dynamics of the mean-square geodesic displacement, the fourth moment, and the kurtosis by truncating their Taylor series expansions. To determine the validity regime of this approximation, the lowest-order term must dominate the expansion, hence introducing a time scale below which the truncated series is valid. From a physical point of view, this regime implies short times, small curvatures, or low diffusivities. For the anomalous case, we use a generalized Taylor series that incorporates fractional derivatives in the Caputo sense, as needed. Also, we expand the moments near the initial condition using Riemann normal coordinates around a flat surface. The resulting series simultaneously incorporates information about surface curvature and the anomalous exponent , thereby modifying both the powers of t and the series coefficients.

We then apply the results to three surfaces with different curvatures (sphere, pseudosphere, and torus) to analyze the combined effects of curvature and fractional exponents on statistical moments. For all three surfaces, we observe that the second and fourth moments show qualitatively similar dynamics. At short times, anomalous exponents increase the magnitude of the moments, contrasting with the usual intuition that subdiffusive processes slow down the dynamics. The subdiffusive phase is obtained for smaller curvatures at somewhat intermediate times, in agreement with recent experiments [54]. The curvature effectively slows the dynamics and induces transitions between heavy-tail regimes and opposite behaviors. The kurtosis in the anomalous case is modified by a correction term that is linear in curvature and of order in time, which dominates at small values of fractional exponents. Qualitatively, as decreases, kurtosis increases. Furthermore, curvature tends to reduce at short and intermediate times.

A potential path to extend the work is to solve the time-fractional diffusion equation with the Laplace–Beltrami operator, a challenging task that can be addressed via approximations. In such a scenario, we would have the most comprehensive description of the system’s dynamics at different time scales. Higher-order moments will be important, as we have shown, since they may provide evidence of the coupling between curvature and the environment’s complex structure. There are also alternative fractional operators with interesting characteristics that can effectively describe relevant diffusion processes, such as the conformable derivative [68]. The corresponding Taylor expansion for this derivative has also been studied [69], so extending our results using alternative operators will also be of interest.

Our results are potentially useful for modeling the heterogeneous diffusion of biomolecules such as proteins interacting on curved cell membranes, or the dynamics of colloids confined to curved substrates, where clogging, memory effects, and nontrivial effective curvature coexist. In summary, we show that the interplay between geometry and temporal anomalies modifies diffusion dynamics, providing a framework for characterizing the joint influence of curvature and memory in complex systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.-A.; formal analysis, G.C.-A. and A.P.-R.; investigation, G.C.-A. and A.P.-R.; methodology, G.C.-A.; software, G.C.-A. and A.P.-R.; visualization, G.C.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.-A. and A.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, G.C.-A.; supervision, G.C.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by SECIHTI through the scholarship granted to A. P.-R. (CVU 2071543). Partial funding from grant No. 94 S232-22 of the project “Proyectos de Investigación Divisionales” from DCNI UAM Cuajimalpa is also acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

No data were employed or generated in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dhont, J.K.G. An Introduction to Dynamics of Colloids; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda-Priego, R. Colloidal soft matter physics. Rev. Mex. Fís. 2021, 67, 050101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackman, E.; Lipowsky, R. (Eds.) Structure and Dynamics of Membranes; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Morgan, D.; Raff, M. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 3rd ed.; Garland Publishing, Inc.: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Duplantier, B. Harmonic Measure of Some Fractal Sets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetitsky, B. Diffusion of charmed quarks in the quark-gluon plasma. Phys. Rev. D 1988, 37, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.L.; Verdaguer, E. Stochastic Gravity: Theory and Applications. Living Rev. Relativ. 2008, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, J.; Hänggi, P. Relativistic Brownian motion. Phys. Rep. 2009, 471, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzetrzelewski, M. The fractional porous medium equation on the sphere. Europhys. Lett. 2017, 117, 38004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Hashimoto, H.; Nilsson, T. Size-dependent diffusion of membrane proteins in lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 4043–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambin, Y.; Lopez-Esparza, R.; Reffay, M.; Sierecki, E.; Gov, N.S.; Genest, M.; Hodges, R.S.; Urbach, W. Lateral mobility of proteins in liquid membranes revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 2098–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbalzarini, I.F.; Hayer, A.; Helenius, A.; Koumoutsakos, P. Simulations of (An)Isotropic Diffusion on Curved Biological Surfaces. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Tian, A.; Esposito, C.; Baumgart, T. Dynamic sorting of lipids and proteins in membrane tubes with a moving phase boundary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenbud, B.M.; Gershon, N.D. Diffusion of molecules on biological membranes of nonplanar form. A theoretical study. Biophys. J. 1982, 38, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J. Diffusion on a curved surface: Physics of chemiexcitation. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 61, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraudo, J. Diffusion equation on curved surfaces. I. Theory and application to biological membranes. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 5831–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Villarreal, P. Brownian motion meets Riemann curvature. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2010, 2010, P08006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Villarreal, P.; Solano-Cabrera, C.O.; Castañeda-Priego, R. Covariant description of the colloidal dynamics on curved manifolds. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1204751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyst, R.; Plewczyński, D.; Aksimentiev, A. Diffusion of spheroidal macromolecules in narrow channels. Phys. Rev. E 1999, 60, 302. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M. A Brownian dynamics algorithm for colloids. J. Comput. Phys. 2004, 201, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Villarreal, P.; Villada-Balbuena, A.; Méndez-Alcaraz, J.M.; Castañeda-Priego, R.; Estrada-Jiménez, S. A Brownian dynamics algorithm for colloids in curved manifolds. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 214115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, B. A simulation algorithm for Brownian dynamics on complex curved surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 164901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés Gómez, A.; Sevilla, F.J. A geometrical method for the Smoluchowski equation on the sphere. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2021, 2021, 083210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Garza, O.A.; Méndez-Alcaraz, J.M.; González-Mozuelos, P. Effects of the curvature gradient on the distribution and diffusion of colloids confined to surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 8661–8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reister, E.; Seifert, U. Lateral diffusion of a protein on a fluctuating membrane. Europhys. Lett. 2005, 71, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gov, N.S. Membrane undulations driven by chemically active proteins. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 73, 041918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.; Brown, F.L.H. Diffusion on ruffled membrane surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 235103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reister-Gottfried, E.; Leitenberger, S.M.; Seifert, U. Hybrid simulations of lateral diffusion on fluctuating membranes. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 031903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, N. Diffusion of a particle on a fluctuating membrane. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 81, 061113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B.S. Dynamical theory of groups and fields. In Relativity, Groups and Topology; DeWitt, C., DeWitt, B., Eds.; Gordon and Breach: New York, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 587–820. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, G.W. Quantum field theory in curved spacetime. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.W., Israel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 639–679. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, T. On eigenvalues of Laplacian and curvature of Riemannian manifold. Tohoku Math. J. 1971, 23, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkey, P.B. The spectral geometry of a Riemannian manifold. J. Differ. Geom. 1975, 10, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsterdamski, P.; Berkin, A.L.; O’Connor, D.J. b8 coefficient of the heat kernel for a compact Riemannian manifold. Class. Quantum Grav. 1989, 6, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfling, F.; Franosch, T. Anomalous transport in the crowded world of biological cells. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 046602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, R.; Klafter, J. The random walk’s guide to anomalous diffusion: A fractional dynamics approach. Phys. Rep. 2000, 339, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Faustmann, M.; Rieder, A. Fractional diffusion in the full space: Decay and regularity. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2022, 25, 1106–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roidos, N.; Shao, Y. The fractional porous medium equation on manifolds with conical singularities I. J. Evol. Eq. 2022, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roidos, N.; Shao, Y. The fractional porous medium equation on manifolds with conical singularities II. Math. Nachr. 2023, 296, 1616–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helin, T.; Lassas, M.; Ylinen, L.; Zhang, Z. Inverse problems for heat equation and space-time fractional diffusion equation with one measurement. J. Diff. Eq. 2020, 269, 7498–7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy, A.; Raposo, E.P. Solution of the space-fractional diffusion equation on bounded domains of superdiffusive phenomena. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 110, 054119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchio, E.; Bonforte, M.; Grillo, G. Smoothing Effects and Extinction in Finite Time for Fractional Fast Diffusions on Riemannian Manifolds. J. Geom. Anal. 2025, 35, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; Granek, R.; Elbaum, M. Enhanced Diffusion in Active Intracellular Transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 5655–5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Elsner, M.; Kartberg, F.; Nilsson, T. Anomalous Subdiffusion Is a Widespread Phenomenon in Live-Cell Plasma Membranes. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 3518–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.H.; Tejedor, V.; Burov, S.; Barkai, E.; Selhuber-Unkel, C.; Berg-Sørensen, K.; Oddershede, L.; Metzler, R. In Vivo-Measured Diffusivity of a Protein Needs Correction for Itinerant Binding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 048103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabei, S.M.A.; Burov, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kuznetsov, A.; Huynh, T.; Jureller, J.; Philipson, L.H.; Dinner, A.R.; Scherer, N.F. Intracellular transport of insulin granules is a subordinated random walk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4911–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, D.S.; Fradin, C. Anomalous Diffusion of Proteins Due to Molecular Crowding. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 2960–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanski, J.; Weiss, M. Elucidating the Origin of Anomalous Diffusion in Crowded Fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 038102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogedby, H.C. Langevin equations for continuous time Lévy flights. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, 1657–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerschaert, M.M.; Benson, D.A.; Scheffler, H.P.; Baeumer, B. Stochastic solution of space-time fractional diffusion equations. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 65, 041103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzinikitas, A. A note on the random walk on a curved surface. arXiv 2000, arXiv:hep-th/0001078. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tyrlik, P.M.; Wang, G. Investigating Diffusing on Highly Curved Water-Oil Interface Using Three-Dimensional Single Particle Tracking. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 8023–8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yang, M.; Zhao, K.; Zong, Y. The single-particle dynamics of square platelets on an inner spherical surface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 700, 138513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Durán, A.; Juárez-Valencia, L.H. Diffusion coefficients and MSD measurements on curved membranes and porous media. Eur. Phys. J. E 2023, 46, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, R.; Barkai, E.; Klafter, J. Anomalous Diffusion and Relaxation Close to Thermal Equilibrium: A Fractional Fokker-Planck Equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3563–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkre, V.M.; Montroll, E.W.; Shlesinger, M.F. Generalized master equations for continuous-time random walks. J. Stat. Phys. 1973, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlesinger, M.F. Origins and applications of the Montroll-Weiss continuous time random walk. Eur. Phys. J. B 2017, 90, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iomin, A.; Méndez, V.; Horsthemke, W. Fractional Dynamics in Comb-Like Structures; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sandev, T.; Iomin, A. Special Functions of Fractional Calculus: Applications to Diffusion and Random Search Processes; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, E. Fractional Langevin equation. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 051106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, F.; Sokolov, I.M. Weak ergodicity breaking in an anomalous diffusion process of mixed origins. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 89, 012136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.H.; Chechkin, A.V.; Metzler, R. Scaled Brownian motion: A paradoxical process with a time dependent diffusivity for the description of anomalous diffusion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 15811–15817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés Gómez, A.; Sevilla, F.J. Fractional and scaled Brownian motion on the sphere: The effects of long-time correlations on navigation strategies. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 108, 054117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ovidio, M.; Nane, E. Fractional Cauchy problems on compact manifolds. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 2016, 34, 232–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odibat, Z.M.; Shawagfeh, N.T. Generalized Taylor’s formula. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 186, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, A.; Benhamou, M.; El Kinani, E.H. The study of fractional anomalous diffusion laws on the hypersphere. Gulf J. Math. 2025, 19, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Metzler, R.; Chechkin, A. Time-fractional Caputo derivative versus other integrodifferential operators in generalized Fokker-Planck and generalized Langevin equations. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 108, 024125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, T. On conformable fractional calculus. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2015, 279, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).