Changes in Paediatric Injury-Related Emergency Department Presentations during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

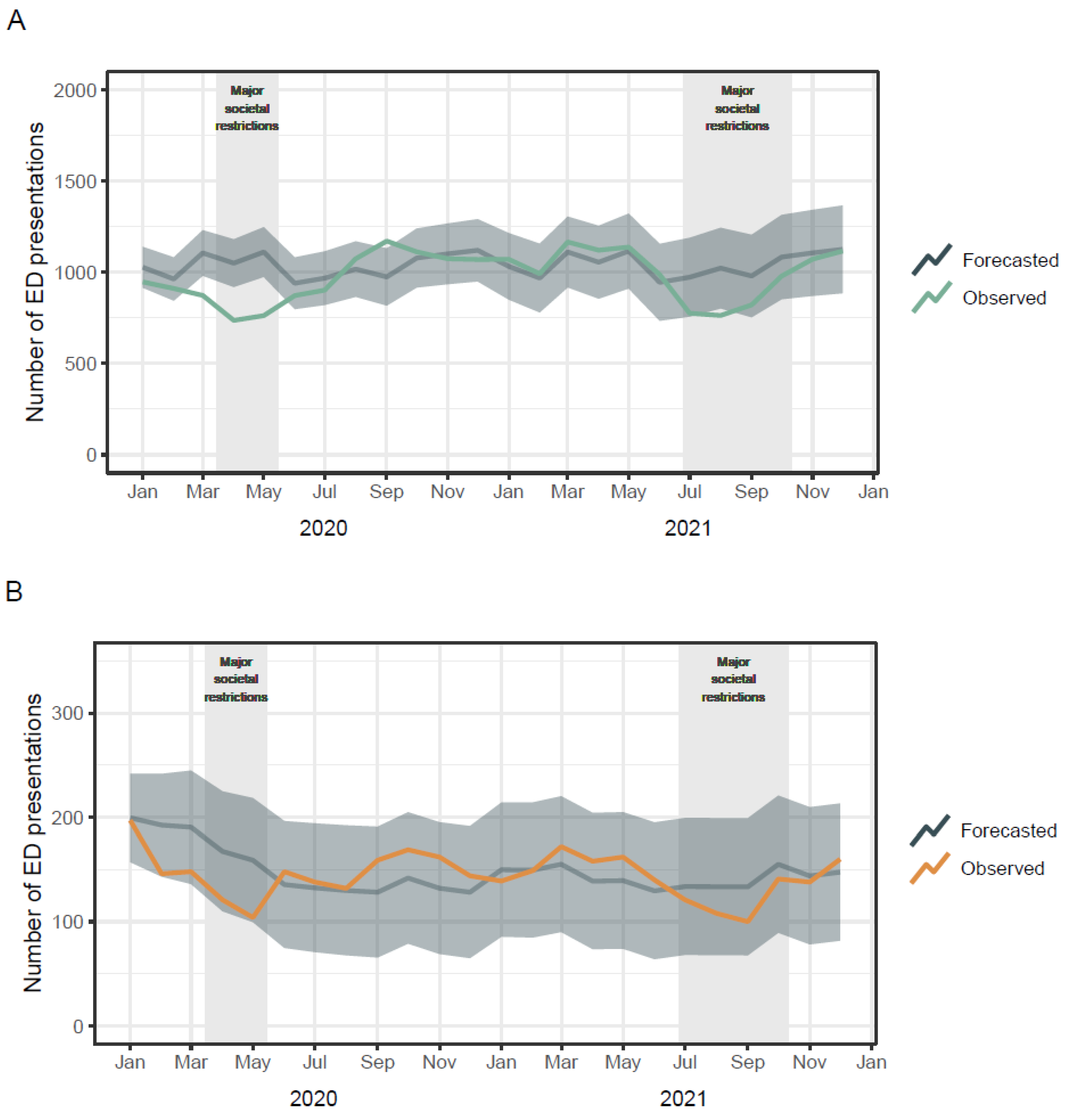

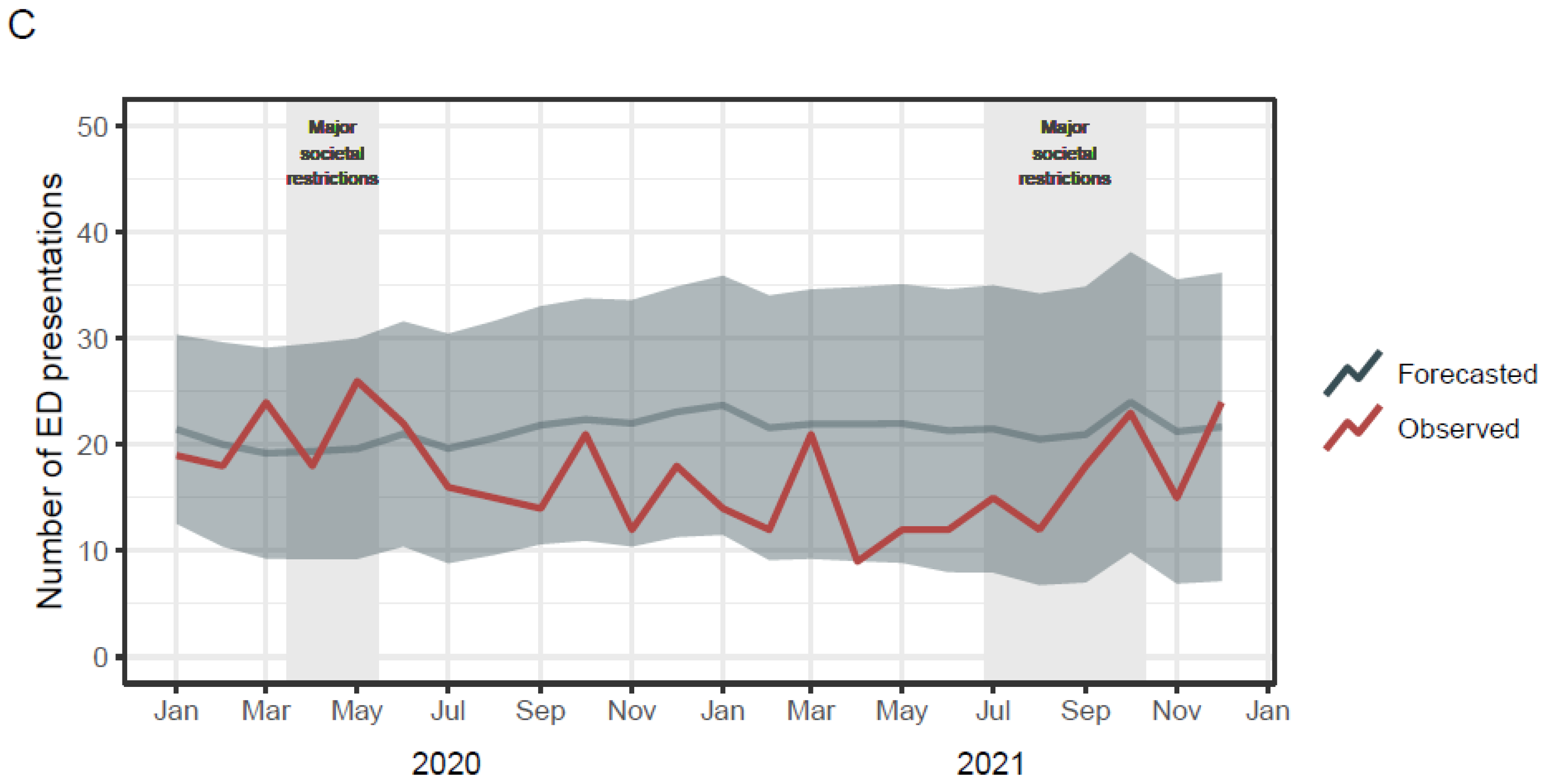

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Roth, L. NSW Public Health Restrictions to Deal with the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Chronology; Issues Backgrounder 5/2020; NSW Parliamentary Research Service: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, A. What Can Traffic Data Tell Us about the Impact of the Coronavirus? Available online: https://www.tomtom.com/newsroom/explainers-and-insights/covid-19-traffic/ (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Qureshi, A.I.; Huang, W.; Khan, S.; Lobanova, I.; Siddiq, F.; Gomez, C.R.; Suri, M.F.K. Mandated societal lockdown and road traffic accidents. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 146, 105747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chand, S.; Yee, E.; Alsultan, A.; Dixit, V.V. A descriptive analysis on the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on road traffic incidents in Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnitzer, M.; Schöttl, S.E.; Kopp, M.; Barth, M. COVID-19 stay-at-home order in Tyrol, Austria: Sports and exercise behaviour in change? Public Health 2020, 185, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, R.; To, Q.G.; Khalesi, S.; Williams, S.L.; Alley, S.J.; Thwaite, T.L.; Fenning, A.S.; Vandelanotte, C. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: Associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutz, M.; Gerke, M. Sport and exercise in times of self-quarantine: How Germans changed their behaviour at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2021, 56, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, E.A.; Lee, C.; Jenkins, M.; Calverley, J.R.; Hodge, K.; Houge Mackenzie, S. Changes in physical activity pre-, during and post-lockdown COVID-19 restrictions in New Zealand and the explanatory role of daily hassles. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 642954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Way, T.L.; Tarrant, S.M.; Balogh, Z.J. Social restrictions during COVID-19 and major trauma volume at a level 1 trauma centre. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 214, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Mwagiru, D.; Thakur, I.; Moghadam, A.; Oh, T.; Hsu, J. Impact of societal restrictions and lockdown on trauma admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-centre cross-sectional observational study. ANZ J. Surg. 2020, 90, 2227–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.; Ellis, D.Y.; Gorman, D.; Foo, N.; Haustead, D. Impact of COVID-19 social restrictions on trauma presentations in South Australia. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2021, 33, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Centre for Classification in Health. ICD-10-AM, 5th ed.; National Centre for Classification in Health: Sydney, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016; Catalogue no. 2033.0.55.001; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Do, V.Q.; Ting, H.P.; Curtis, K.; Mitchell, R. Internal validation of models for predicting paediatric survival and trends in serious paediatric hospitalised injury in Australia. Injury 2020, 51, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.; Ting, H.P. Survival Risk Ratios for ICD-10-AM Injury Diagnosis Classifications for Children [Dataset]. Available online: https://figshare.mq.edu.au/articles/dataset/Survival_risk_ratios_for_ICD-10-AM_injury_diagnosis_classifications_for_children/14852949/1 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Lystad, R.P.; Fyffe, A.; Orr, R.; Browne, G. Incidence, trends, and seasonality of paediatric injury-related emergency department presentations at a large level 1 paediatric trauma centre in Australia. Trauma Care 2022, 2, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Bergmeir, C.; Caceres, G.; Chhay, L.; O’Hara-Wild, M.; Petropoulos, F.; Razbash, S.; Wang, E.; Yasmeen, F. Forecasting Functions for Time Series and Linear Models, Version 8.18. 2022. Available online: https://pkg.robjhyndman.com/forecast/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Antonini, M.; Hinwood, M.; Paolucci, F.; Balogh, Z.J. The epidemiology of major trauma during the first wave of COVID-19 movement restriction policies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 2045–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofijur, M.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Alam, M.A.; Islam, A.S.; Ong, H.C.; Rahman, S.A.; Najafi, G.; Ahmed, S.F.; Uddin, M.A.; Mahlia, T.M. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: Lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontopantelis, E.; Doran, T.; Springate, D.A.; Buchan, I.; Reeves, D. Regression based quasi-experimental approach when randomisation is not an option: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, J.; Fielding, S.; Ramsay, C.R. Methodology and reporting characteristics of studies using interrupted time series design in healthcare. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.L.; Karahalios, A.; Forbes, A.B.; Taljaard, M.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Cheng, A.C.; Bero, L.; McKenzie, J.E. Design characteristics and statistical methods used in interrupted time series studies evaluating public health interventions: A review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 122, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | 2020 N (%) | 2021 N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8132 (60.2) | 8259 (59.5) |

| Female | 5375 (39.8) | 5629 (40.5) |

| Age group | ||

| 0 years | 817 (6.0) | 1047 (7.5%) |

| 1–5 years | 6001 (44.4) | 6389 (46.0) |

| 6–10 years | 3431 (25.4) | 3425 (24.7) |

| 11–15 years | 3258 (24.1) | 3027 (21.8) |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage 1 | ||

| 1 (most disadvantaged) | 3242 (24.3) | 3073 (22.4) |

| 2 | 892 (6.7) | 969 (7.1) |

| 3 | 1864 (14.0) | 1934 (14.1) |

| 4 | 3084 (23.2) | 3225 (23.5) |

| 5 (least disadvantaged) | 4234 (31.8) | 4498 (32.8) |

| Mode of arrival | ||

| Private car | 11,758 (87.1) | 12,017 (86.5) |

| Ambulance | 1667 (12.3) | 1833 (13.2) |

| Other | 82 (0.6) | 38 (0.3) |

| Triage category | ||

| Less urgent condition | 293 (2.2) | 184 (1.3) |

| Potentially serious condition | 9689 (71.7) | 10,566 (76.1) |

| Potentially life-threatening condition | 2556 (18.9) | 2441 (17.6) |

| Imminently life-threatening condition | 727 (5.4) | 531 (3.8) |

| Immediately life-threatening condition | 242 (1.8) | 166 (1.2) |

| Injury severity | ||

| Minor (ICISS > 0.99) 2 | 11,516 (85.3) | 12,013 (86.5) |

| Moderate (ICISS 0.98–0.99) 2 | 1768 (13.1) | 1688 (12.1) |

| Serious (ICISS < 0.98) 2 | 223 (1.7) | 187 (1.3) |

| Departure status | ||

| Discharged | 10,753 (79.6) | 10,724 (77.2) |

| Admitted | 2411 (17.9) | 2732 (19.7) |

| Departed | 317 (2.3) | 407 (2.9) |

| Transferred | 25 (0.2) | 25 (0.2) |

| Died | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diagnosis | 2020 N (%) | 2021 N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Injuries to the head (S00–S09) | 3640 (26.9) | 3877 (27.9) |

| Injuries to the neck (S10–S19) | 60 (0.4) | 48 (0.3) |

| Injuries to the thorax (S20–S29) | 27 (0.2) | 29 (0.2) |

| Injuries to the abdomen, lower back, lumbar spine and pelvis (S30–S39) | 148 (1.1) | 153 (1.1) |

| Injuries to the shoulder and upper arm (S40–S49) | 803 (5.9) | 815 (5.9) |

| Injuries to the elbow and forearm (S50–S59) | 2103 (15.6) | 2127 (15.3) |

| Injuries to the wrist and hand (S60–S69) | 1581 (11.7) | 1375 (9.9) |

| Injuries to the hip and thigh (S70–S79) | 162 (1.2) | 140 (1.0) |

| Injuries to the knee and lower leg (S80–S89) | 701 (5.2) | 688 (5.0) |

| Injuries to the ankle and foot (S90–S99) | 817 (6.0) | 878 (6.3) |

| Injuries involving multiple body regions (T00–T07) | 47 (0.3) | 47 (0.3) |

| Injuries to unspecified part of trunk, limb or body region (T08–T14) | 1594 (11.8) | 1524 (11.0) |

| Effects of foreign body entering through natural orifice (T15–T19) | 699 (5.2) | 768 (5.5) |

| Burns (T20–T32) | 416 (3.1) | 255 (1.8) |

| Poisoning by drugs, medicaments, and biological substances (T36–T50) | 57 (0.4) | 64 (0.5) |

| Toxic effects of substances chiefly nonmedicinal as to source (T51–T65) | 58 (0.4) | 68 (0.5) |

| Other and unspecified effects of external causes (T66–T78) | 113 (0.8) | 651 (4.7) |

| Certain early complications of trauma (T79) | 42 (0.3) | 41 (0.3) |

| Complications of surgical and medical care (T80–T89) | 439 (3.3) | 340 (2.4) |

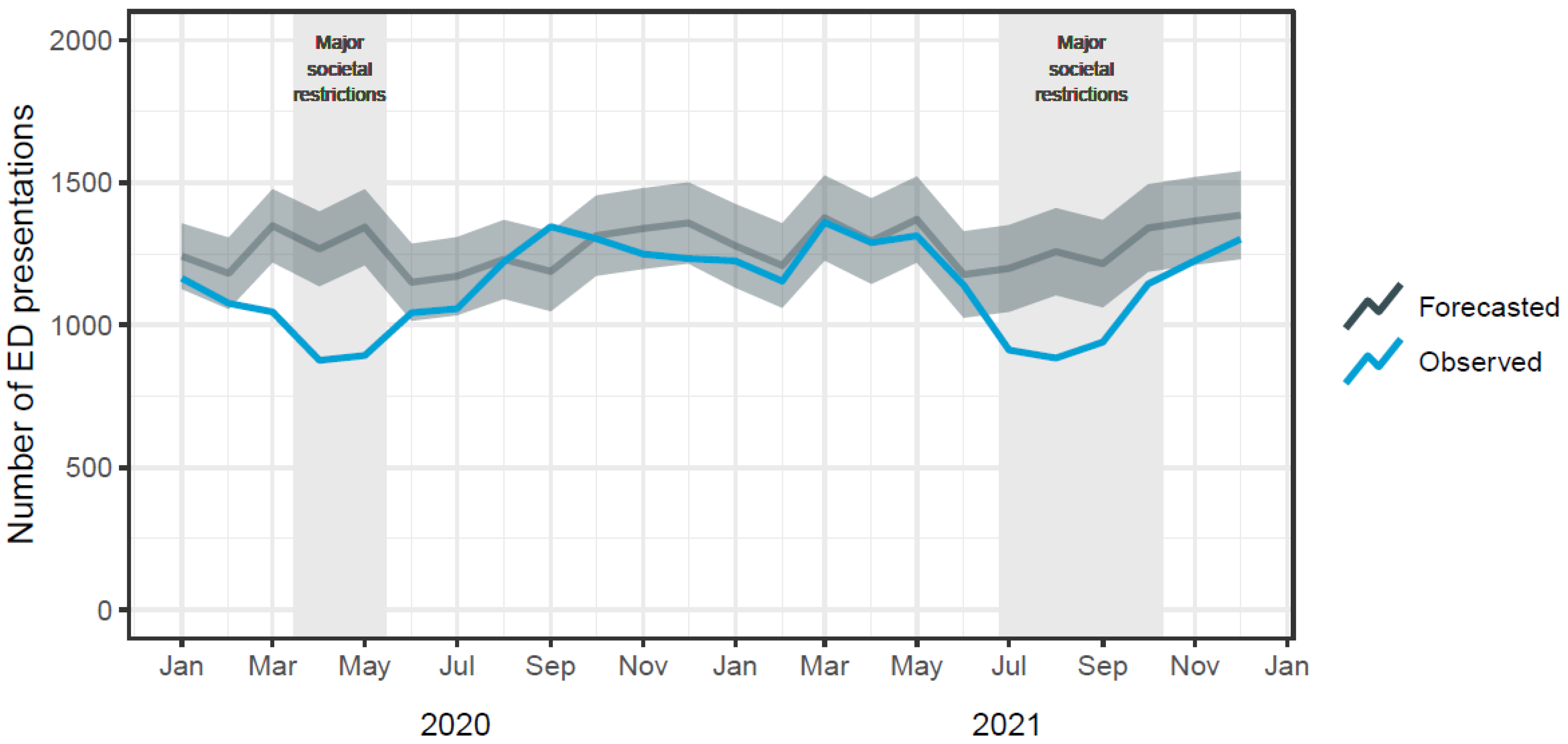

| Month | Forecasted (95% PI) | Observed | Absolute Difference | Relative Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | ||||

| January | 1242 (1127–1356) | 1164 | −78 | −6.7% |

| February | 1181 (1056–1307) | 1076 | −105 | −9.8% |

| March | 1348 (1220–1477) | 1046 | −302 | −28.9% |

| April | 1267 (1136–1398) | 876 | −391 | −44.7% |

| May | 1343 (1210–1476) | 893 | −450 | −50.4% |

| June | 1150 (1015–1285) | 1043 | −107 | −10.3% |

| July | 1171 (1034–1308) | 1057 | −114 | −10.8% |

| August | 1230 (1092–1369) | 1222 | −8 | −0.7% |

| September | 1188 (1048–1328) | 1345 | 157 | 11.7% |

| October | 1313 (1173–1454) | 1303 | −10 | −0.8% |

| November | 1338 (1197–1480) | 1249 | −89 | −7.2% |

| December | 1358 (1216–1501) | 1233 | −125 | −10.2% |

| 2021 | ||||

| January | 1278 (1131–1424) | 1225 | −53 | −4.3% |

| February | 1209 (1060–1357) | 1156 | −55 | −4.7% |

| March | 1376 (1226–1525) | 1360 | −16 | −1.2% |

| April | 1294 (1144–1445) | 1289 | −5 | −0.4% |

| May | 1370 (1219–1521) | 1313 | −57 | −4.4% |

| June | 1177 (1026–1329) | 1140 | −37 | −3.2% |

| July | 1198 (1046–1351) | 912 | −286 | −31.4% |

| August | 1257 (1105–1410) | 884 | −373 | −42.2% |

| September | 1215 (1062–1368) | 940 | −275 | 29.3% |

| October | 1340 (1187–1494) | 1144 | −196 | −17.2% |

| November | 1365 (1211–1519) | 1226 | −139 | −11.4% |

| December | 1385 (1231–1539) | 1301 | −84 | −6.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lystad, R.P.; Fyffe, A.; Orr, R.; Browne, G. Changes in Paediatric Injury-Related Emergency Department Presentations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Trauma Care 2023, 3, 46-54. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3020006

Lystad RP, Fyffe A, Orr R, Browne G. Changes in Paediatric Injury-Related Emergency Department Presentations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Trauma Care. 2023; 3(2):46-54. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3020006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLystad, Reidar P., Andrew Fyffe, Rhonda Orr, and Gary Browne. 2023. "Changes in Paediatric Injury-Related Emergency Department Presentations during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Trauma Care 3, no. 2: 46-54. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3020006

APA StyleLystad, R. P., Fyffe, A., Orr, R., & Browne, G. (2023). Changes in Paediatric Injury-Related Emergency Department Presentations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Trauma Care, 3(2), 46-54. https://doi.org/10.3390/traumacare3020006