Abstract

Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) is a rare but potentially reversible neurological manifestation associated with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C). We report an eight-year-old boy who developed PRES secondary to MIS-C following asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 exposure. The patient presented with fever, seizures, decreased consciousness, and visual disturbances. MRI revealed characteristic bilateral parieto-occipital and posterior temporal cortical–subcortical hyperintensities, while CT scans were normal. The patient achieved full neurological recovery with corticosteroid therapy, blood pressure control, and supportive management. This case underscores the importance of early MRI in detecting PRES when clinical or CT findings are inconclusive, emphasizing the need for heightened awareness among pediatric clinicians to prevent irreversible neurological sequelae.

1. Introduction

Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) is a neurotoxic state characterized by seizures, headaches, visual disturbances, and altered consciousness, commonly associated with vasogenic edema affecting the parieto-occipital regions on MRI [1]. It is often triggered by hypertension, renal disease, autoimmune conditions, or systemic inflammation [2].

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) emerged as a distinct post-infectious inflammatory response following SARS-CoV-2 exposure [3]. Although neurological manifestations are rare, PRES represents a severe but potentially reversible complication [4]. We present a unique pediatric case of MRI-proven PRES secondary to MIS-C in Indonesia, highlighting the role of imaging in diagnosis and the correlation between systemic inflammation, transient hypertension, and reversible cerebral edema.

2. Case Report

In June 2021, during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia, an eight-year-old boy was referred to our tertiary care hospital with a three-day history of fever, decreased consciousness, agitation, bilateral hand convulsions, and visual hallucinations. On admission, the patient presented with acute symptomatic seizures characterized by bilateral upper-limb clonic movements, associated with altered consciousness, agitation, and visual hallucinations, without prior seizure history. The initial seizure episodes occurred on illness day 2–3, were estimated to last several minutes, and recurred, prompting intravenous phenytoin loading (700 mg followed by 300 mg within 2 h) and subsequent maintenance therapy (2 × 100 mg/day), after which no further generalized convulsive seizures were observed. He had been initially admitted to a secondary hospital, with no prior history of seizures, allergies, autoimmune diseases, COVID-19 contact, cough, or respiratory symptoms.

On presentation, his weight was 37 kg, and his Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was E3M4V5. His vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 110/62 mmHg, heart rate 112 bpm, respiratory rate 24 breaths/min, temperature 38.9 °C, and oxygen saturation of 100% on 1 L/min supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula. Neurological examination revealed bilateral positive Babinski signs but no evidence of hemiparesis, meningeal signs, cranial nerve deficits, or pupillary abnormalities. In the inguinal region, multiple erythematous maculopapular lesions with desquamation were observed, accompanied by numerous excoriation marks. A chest X-ray from the previous hospital indicated bilateral pneumonia, while a non-contrast brain CT scan was unremarkable.

Laboratory investigations from the referring facility revealed thrombocytopenia (platelets: 104,000/µL), uncompensated metabolic acidosis (pH 7.28, pCO2 15 mmHg, base excess −17, HCO3− 7 mEq/L), elevated C-reactive protein (22 mg/L), markedly increased liver enzymes (AST 235 U/L, ALT 133 U/L, GGT 518 U/L), prolonged coagulation parameters (PT 17.2 s, APTT 49.2 s), and mild acute kidney injury (serum creatinine 1.12 mg/dL). The NS1 antigen test returned positive, whereas both the COVID-19 antigen test and the rapid molecular assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis from gastric aspirate were negative.

Initial treatment included intravenous phenytoin, omeprazole, paracetamol, dexamethasone, and vitamin K. Upon transfer, he was placed in a COVID-19 isolation room, where treatment was continued. A nasogastric tube and a central venous catheter (via the right femoral vein) were inserted for fluid administration. Ceftriaxone was added empirically, and a COVID-19 serology test was ordered. The dermatological lesions were suspected to be of fungal origin, and topical miconazole cream was prescribed. Due to regional protocols at the time, swab samples had to be sent to a central laboratory, with results taking up to a week.

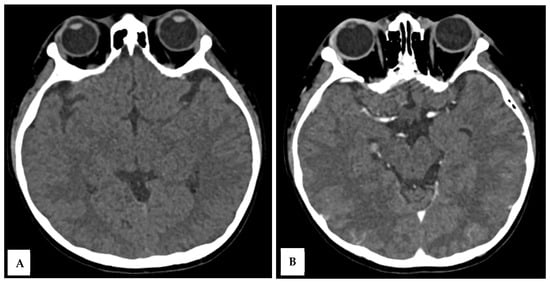

Over the next 48 h, the patient’s consciousness fluctuated, with a GCS deteriorating to E2M4V2. There were no significant changes in laboratory parameters. Brownish aspirate from the NGT prompted the discontinuation of dexamethasone. On day 5 of illness, a contrast-enhanced head CT scan was performed to evaluate for meningoencephalitis, which showed no abnormalities (Figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

A 10-year-old boy presented with visual disturbance and seizures. Axial non-contrast (A) and axial contrast-enhanced (B) head CT scans showed no evidence of meningoencephalitis, with findings within normal limits.

By day 6, COVID-19 serology returned positive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG, with negative IgM and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2. Further history revealed that his mother had experienced a mild flu-like illness three weeks earlier, without fever, cough, or known COVID-19 contact. Additional lab tests showed elevated D-dimer (2754 ng/mL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (27 mm/h), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH 795 U/L), with normal fibrinogen. Coagulation parameters and renal function were normalized. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed mildly elevated protein (52.2 mg/dL), borderline leukocyte count (5 cells/μL, 80% neutrophils), and normal glucose and chloride levels. Based on the clinical and laboratory findings, a diagnosis of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) was established, and intravenous methylprednisolone was reintroduced for five days.

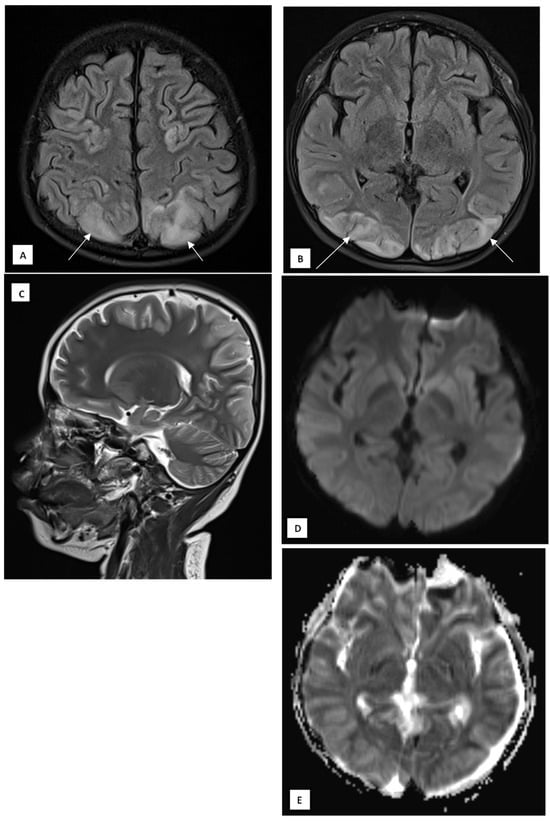

On day 9, the patient’s GCS improved to E4M6V5, with the resolution of fever and seizures. However, he developed sudden blurry vision, headache, and vomiting, without clinical seizures. Ophthalmological examination revealed normal funduscopy but significantly reduced visual acuity (1/300 bilaterally). His blood pressure was elevated to 147/89 mmHg, HR 145 bpm, RR 22 breaths/min, and temperature 37.9 °C. Brain MRI was performed on a 1.5T GE Healthcare scanner with multiplanar T1-weighted imaging (T1WI), T2WI, fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion weighted imaging—apparent diffusion coefficient (DWI-ADC), susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI), with T1 fat saturated (T1FS) pre- and post-contrast. MRI revealed hyperintense lesions in the cortical and subcortical regions of the bilateral parieto-occipital lobes, posterior temporal lobes, left precuneus, bilateral central sulcus areas, and cerebellar periphery, consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) (Figure 2A–E). There was no contrast enhancement or hemosiderin deposition on SWI.

Figure 2.

A 10-year-old boy presented with visual disturbance and seizures. (A,B) Axial T2 dark-fluid images show hyperintense lesions involving the cortical and subcortical regions of the bilateral parieto-occipital lobes, bilateral posterior temporal lobes, left precuneus gyrus, bilateral central sulcus areas, and peripheral cerebellar hemispheres (arrows). (C) Sagittal T2-weighted image confirms the posterior predominance of the lesions. (D) Diffusion-weighted image shows no diffusion restriction. (E) The apparent diffusion coefficient map demonstrates corresponding hyperintensities, consistent with a vasogenic edematous process.

On day 10, the patient experienced a 15 min episode of persistent leftward gaze without motor convulsions, accompanied by unresponsiveness. A phenytoin loading dose was administered due to status epilepticus, which terminated the episode, but the patient remained somnolent. An intravenous antihypertensive agent, labetalol, was administered to control his blood pressure. A follow-up brain MRI was done in order to rule out other pathologies, but the imaging findings are relatively similar to the previous one. A multidisciplinary consultation was held, and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was considered. However, due to supply constraints during the pandemic, IVIG was unavailable. Due to the resource constraints in Indonesia, despite our hospital being a tertiary pediatric care hospital, there were no resources to check for serum immunoglobulin levels. The patient was managed conservatively with continued phenytoin and supportive care.

Between days 11 and 15, the patient gradually regained full consciousness, visual acuity, and neurologic function, with no recurrence of fever or seizures. Laboratory parameters were normalized, and he was discharged on day 15 in stable condition with complete clinical recovery.

A summary of focused neurological examination at key time points showed:

- Admission: decreased level of consciousness (GCS 12), bilateral positive Babinski signs, hyperreflexia, no hemiparesis, intact pupillary reflexes.

- At onset of visual disturbance: fully conscious (GCS 15), acute bilateral visual acuity reduction (1/300), normal cranial nerve examination, no lateralizing motor signs.

- At discharge: normal consciousness and orientation (GCS 15), resolution of visual symptoms, normal cranial nerve function, symmetric motor strength, physiological reflexes, and absence of pathological reflexes.

Table 1 summarizes the laboratory values.

Table 1.

Trends in our patients’ laboratory values.

3. Discussion

This case highlights that PRES is associated with reversible neurological complications in MIS-C. The temporal sequence, systemic inflammation, transient hypertension, seizures, and visual loss match the classic presentation of PRES [1,2]. MRI confirmed bilateral parieto-occipital and posterior temporal cortical–subcortical hyperintensities, consistent with vasogenic edema rather than cytotoxic injury. The normal CT findings emphasize the superior sensitivity of MRI in detecting PRES [5].

The proposed mechanism involves immune-mediated endothelial dysfunction triggered by cytokine release in MIS-C, leading to cerebral autoregulatory failure and increased vascular permeability [2,6]. Several immunology panels, such as immunoglobulins, were raised in MIS-C patients, raising the possibility of autoimmune components [7]. Unfortunately, due to resource constraints at that time, these panels could not be checked in our patient. The child’s mild hypertension likely compounded the process, causing reversible blood–brain barrier disruption. The absence of diffusion restriction and the presence of high ADC values supported a vasogenic pattern, correlating with the complete clinical recovery.

While PRES typically associates with renal or autoimmune disease, it may also arise from inflammation-induced endothelial injury, even in normotensive states [2]. The MIS-C–related cytokine surge, dominated by interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, further contributes to vascular permeability and edema [6]. This aligns with our patient’s elevated inflammatory markers and rapid improvement following corticosteroid therapy.

Although the exact mechanism linking PRES and SARS-CoV-2 remains unclear, several competing theories have been proposed. One hypothesis highlights the role of systemic inflammation, suggesting that cytokine storms may cause toxic endothelial injury to the blood–brain barrier, thereby contributing to PRES. Another theory implicates the direct interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors found on endothelial cells and neurons, leading to vascular and neuronal damage [8]. Although SARS-CoV-2 is not considered a classic neurotropic virus, it may still cause neuroinvasion through hematogenous spread or retrograde pathways, particularly in regions expressing high ACE2 levels, such as the brainstem and hypothalamus. Postmortem studies have shown widespread astrocytosis, microglial activation, and hypoxic–ischemic damage, which further suggests that immune-mediated injury, systemic inflammation, and critical illness-related factors could collectively contribute to PRES pathogenesis in COVID-19 [6].

PRES in children is frequently associated with a variety of underlying conditions and inciting factors. The most commonly reported triggers include renal insufficiency from various causes, hematologic diseases, and treatments involving cytotoxic or immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids [9]. Other contributing conditions include autoimmune and connective tissue disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus), sepsis, solid organ and bone marrow transplantation, hemolytic uremic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and hypertensive disorders [8,10]. The absence of comorbidities should not preclude a diagnosis of PRES if the clinical and radiological features are consistent, as demonstrated by our case. This raises the possibility that MIS-C may act as an independent risk factor for PRES, potentially triggering it directly or through immune dysregulation or sepsis-related mechanisms.

Brain imaging, particularly MRI, plays a critical role in diagnosing PRES by revealing characteristic patterns of vasogenic edema, although findings can vary widely [9]. The three primary MRI patterns, which are dominant parieto-occipital, holohemispheric watershed, and superior frontal sulcus, account for approximately 70% of cases. These patterns typically show bilateral but often asymmetric subcortical white matter involvement, frequently accompanied by cortical changes [5]. Incomplete or atypical presentations are also common, including partial or asymmetric expression of these patterns, often with patchy or linear edema in the frontal lobes [11]. Beyond these classic areas, atypical findings may involve the frontal and temporal lobes (seen in up to 75% of cases), basal ganglia and brainstem (up to one-third), and cerebellum (up to half), usually alongside parieto-occipital involvement. Less commonly, restricted diffusion is observed in 15–30% of cases, typically representing irreversible injury. Intracranial hemorrhage, which is the most frequent intraparenchymal or sulcal subarachnoid hemorrhage, occurs in 10–25% of patients and is associated with anticoagulation or coagulopathy. Additionally, contrast enhancement may be seen in about 20% of cases [2,5]. Vascular imaging (MRA or catheter angiography) has shown vasoconstriction in 15–30% of cases, most notably in the posterior circulation, though higher rates have been reported in selected studies. CT scans may show edema in some cases, but MRI, particularly T2-weighted FLAIR sequences, remains more sensitive and is preferred for accurate detection and characterization of PRES [2]. In both this systematic review and our case report, CT scans did not reveal any abnormalities, suggesting that CT may lack the sensitivity required to detect PRES or that its diagnostic utility is highly dependent on timing, with greater effectiveness if performed during the acute phase of the condition [5].

This patient fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for MIS-C, most consistently under the WHO definition and in alignment with CDC and RCHCH guidelines. He presented with persistent fever for ≥3 days, accompanied by laboratory evidence of systemic inflammation, including elevated CRP, ESR, D-dimer, LDH, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and multiorgan enzyme derangement. Multisystem involvement was clearly demonstrated, with neurologic manifestations (seizures, encephalopathy, acute visual loss), mucocutaneous involvement (erythematous desquamating rash), hepatic dysfunction (marked AST, ALT, and GGT elevation), renal involvement (acute kidney injury), and hematologic abnormalities. Evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by a positive IgG serology test with a negative RT-PCR result, consistent with a post-infectious inflammatory state, further supported by a compatible epidemiologic exposure three weeks earlier. Alternative diagnoses were systematically excluded: acute COVID-19 was unlikely given negative RT-PCR and absence of respiratory failure; bacterial sepsis and meningoencephalitis were not supported by CSF analysis, cultures, or imaging; tuberculosis was excluded by negative molecular testing; and primary epileptic, autoimmune, or vasculitic etiologies were inconsistent with the systemic inflammatory profile and rapid steroid responsiveness. Collectively, these findings support MIS-C as the unifying diagnosis, with PRES representing a secondary immune-mediated neurological complication.

Given the positive dengue NS1 antigen, dengue-related neurological involvement was carefully considered in the differential diagnosis. Dengue infection can cause dengue encephalopathy or encephalitis through metabolic derangements, hepatic dysfunction, immune-mediated mechanisms, or, less commonly, direct neuroinvasion, and may be accompanied by systemic inflammation and thrombocytopenia [12,13]. However, dengue-associated neurological manifestations typically occur during the acute viremic phase, often in the context of plasma leakage, shock, or progressive hemorrhagic features [12]. In our patient, there was no evidence of shock, plasma leakage, or hemorrhagic complications, and the neurological deterioration occurred in a delayed, post-infectious timeframe. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in dengue encephalitis commonly demonstrate pleocytosis, elevated protein, or dengue-specific IgM or viral RNA [13,14], whereas our patient’s CSF showed only mildly elevated protein with a borderline leukocyte count, arguing against active viral encephalitis. Hematologically, dengue typically exhibits progressive thrombocytopenia and hemoconcentration during the critical phase [12], while platelet counts in this case stabilized as systemic inflammation persisted. From a neuroimaging standpoint, dengue-related CNS involvement more frequently affects the basal ganglia, thalami, brainstem, or cerebellum, and may demonstrate hemorrhage or diffusion restriction [13,14], in contrast to the bilateral posterior cortical–subcortical vasogenic edema without diffusion restriction seen in this patient, which is characteristic of PRES [5]. Conversely, the patient fulfilled established criteria for MIS-C, with persistent fever ≥3 days, marked hyperinflammation, multisystem involvement, positive SARS-CoV-2 IgG with negative RT-PCR, and exclusion of alternative infectious etiologies [3]. MIS-C was therefore considered the primary unifying diagnosis, with PRES representing a secondary immune- and endothelial-mediated complication, while dengue NS1 positivity was interpreted as incidental or insufficient to explain the delayed hyperinflammatory phenotype and characteristic imaging findings.

The management of PRES centers on treating the precipitating factor, controlling blood pressure, and preventing seizures [15]. In this case, prompt administration of corticosteroids and antihypertensives resulted in clinical and radiologic reversal. MRI follow-up confirmed resolution, consistent with the reversible nature of PRES [1].

This case expands the limited literature linking PRES and MIS-C [4]. It also demonstrates that CT alone may fail to reveal early edema, underscoring the importance of MRI when neurological deterioration occurs in MIS-C patients [5].

4. Conclusions

This case report highlights PRES as a rare but important neurological complication of MIS-C, and this entity should be suspected in MIS-C patients presenting with seizures, altered consciousness, or visual loss, even when CT scans are normal. Magnetic resonance imaging remains the diagnostic modality of choice for identifying characteristic vasogenic edema. Early recognition and timely management of hypertension and inflammation are crucial to ensuring full neurological recovery and preventing irreversible injury.

Author Contributions

I.N.B. obtained the parents’ consents, while I.N.B. and R.S. reviewed the radiological findings. C.B.H.S. and G.S.O. wrote the initial draft, and all authors revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it is a single case report that does not meet the criteria for research involving human subjects according to institutional and national guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal and written consent were obtained from the parents.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC | apparent diffusion coefficient |

| APTT | activated partial thromboplastin time |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| DWI | diffusion-weighted imaging |

| DWI-ADC | diffusion-weighted imaging–apparent diffusion coefficient |

| EEG | electroencephalography |

| ESR | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| FLAIR | fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| GGT | gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| MIS-C | multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PRES | posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome |

| PT | prothrombin time |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SGOT | serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SGPT | serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase |

| SWI | susceptibility-weighted imaging |

| T1FS | T1-weighted fat-saturated imaging |

References

- Hinchey, J.; Chaves, C.; Appignani, B.; Breen, J.; Pao, L.; Wang, A.; Pessin, M.S.; Lamy, C.; Mas, J.-L.; Caplan, L.R. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugate, J.E.; Rabinstein, A.A. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfred-Cato, S.; Abrams, J.Y.; Balachandran, N.; Jaggi, P.; Jones, K.; Rostad, C.A.; Lu, A.T.B.; Fan, L.B.; Jabbar, A.; Anderson, E.J.; et al. Distinguishing Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children from COVID-19, Kawasaki Disease and Toxic Shock Syndrome. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, J.; Toni, L.; Fencl, F.; Hrdlicka, R.; Buksakowska, I.; Paulas, L.; Lebl, J. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome-A Rare Complication of COVID-19 MIS-C. Klin. Padiatr. 2023, 235, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartynski, W.S.; Boardman, J.F. Distinct imaging patterns and lesion distribution in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2007, 28, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.L.; Benjamin, L.; Lunn, M.P.; Bharucha, T.; Zandi, M.S.; Hoskote, C.; McNamara, P.; Manji, H. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of neuroinflammation in COVID-19. BMJ 2023, 382, e073923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobh, A.; Madiha abdalla Abdelrahman, A.M.; Mosa, D.M. COVID-19 diversity: A case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children masquerading as juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2022, 36, 03946320221131981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Kudo, E.; Hatakeyama, K.; Ito, T. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome associated with mild COVID-19 infection in a 9-year-old child: A case report and literature review. IDCases 2023, 31, e01699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.H. Childhood Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: Clinicoradiological Characteristics, Managements, and Outcome. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmazer, B.; Ozogul, M.; Hikmat, E.; Kilic, H.; Aygun, F.; Arslan, S.; Kizilkilic, O.; Kocer, N. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in a Pediatric COVID-19 Patient. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e240–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.M.; Toh, C.H. Spectrum of neuroimaging mimics in children with COVID-19 infection. Biomed. J. 2022, 45, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, T.; Dung, N.M.; Vaughn, D.W.; Kneen, R.; Thao, L.T.T.; Raengsakulrach, B.; Loan, H.T.; Day, N.P.; Farrar, J.; Myint, K.S.; et al. Neurological manifestations of dengue infection. Lancet 2000, 355, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carod-Artal, F.J.; Wichmann, O.; Farrar, J.; Gascón, J. Neurological complications of dengue virus infection. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasay, M.; Channa, R.; Jumani, M.; Shabbir, G.; Azeemuddin, M.; Kamal, A.K. Encephalitis and myelitis associated with dengue viral infection. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2008, 110, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, J.D.; Kutlubaev, M.A.; Kermode, A.G.; Hardy, T. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): Diagnosis and management. Pract. Neurol. 2022, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.