Abstract

Background: According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), long COVID refers to symptoms persisting for four weeks or more after acute infection, with over 100 identified, including fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and breathlessness. Women aged 45–54 are disproportionately affected, overlapping with the typical age for perimenopause and menopause. This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of existing research on the intersection between long COVID and the menopausal transition. Methods: Five database (CINAHL ultimate, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane, and Scopus) searches yielded 387 articles; after removing 40 duplicates and screening 347 titles and abstracts, fourteen studies were reviewed in full, with seven meeting the inclusion criteria (examined both long COVID and menopause in their scope and are written in English language). Results: This scoping review identified a significant symptomatic overlap between long COVID and menopause reported by participants, particularly fatigue, cognitive difficulties, mood changes, and sleep disturbances. Preliminary evidence also suggests that hormonal fluctuations may influence symptom severity, though biological mechanisms remain insufficiently understood. Methodological limitations restrict generalisability, underscoring the need for longitudinal symptom tracking, diverse samples, and biomarker-informed studies. Recognising the intersection of long COVID and menopausal transition is essential for improving assessment, management, and targeted care for affected women.

1. Introduction

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines [1], long COVID is defined as the persistence of post-viral symptoms lasting from four weeks to beyond twelve weeks following an acute COVID-19 infection. Long COVID is characterised by a wide range of debilitating symptoms; over 100 have been identified, including muscle pain, severe fatigue, post-exertional malaise, sleep disturbances, breathlessness, as well as neurological and cognitive impairments [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Various terms have been used to describe this long COVID condition, such as “post-COVID condition”, “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC)”, “long-haul COVID”, and “COVID-19 recovery syndrome”, reflecting the evolving understanding of its complex and varied nature. Due to considerable variability in how long COVID is defined across the literature, this current paper adopts the NICE guidelines’ definition and terminology, “long COVID” [1].

The cumulative global incidence of long COVID has been estimated at approximately 400 million cases [10]. Reflecting this global burden at a national level, the ONS [11] reported that approximately 2 million people living in England and Scotland, around 3.3% of the population, self-reported experiencing long COVID. Among these individuals, those aged 45 to 54 were the most likely to report long COVID, with a higher prevalence observed in females (3.6%) compared to males (3%) within this age group [11]. Moreover, epidemiological studies have identified certain demographic groups, particularly women aged 35–50 years, among others, as being at higher risk of developing long COVID and more likely to experience severe and persistent symptoms [12,13,14,15].

Notably, the demographic most affected by long COVID, women aged 45 to 54 years of age, coincides with the typical age for the onset of perimenopause and menopause [16]. Menopause is defined as the permanent end of menstruation, usually diagnosed after 12 months without periods, typically occurring between the ages of 45 and 55 years (average age 51 years in the UK), though it can happen earlier due to surgery or medical treatment and varies across ethnic groups [16]. Perimenopause, or the menopausal transition, is the time before menopause when hormone levels change and periods become irregular; it usually lasts a few years and ends 12 months after the final period [16]. Postmenopause refers to the stage that begins after a woman has experienced 12 consecutive months without a period [16]. This overlap in age and gender risk factors has prompted emerging research into the possible intersection between long COVID and the menopausal transition [17,18].

The impact of long COVID on women’s reproductive health, especially during menopause, among many, represents an important area warranting further investigation [19]. Certain hormones, including but not limited to those implicated in the menstrual cycle, oestrogen and progesterone, are known to influence immunological parameters [20]. Furthermore, people with long COVID exhibit immune perturbation or dysregulation, suggesting an immunopathogenic aetiology of long COVID [21]. Interestingly, there appears to be a bidirectional relationship between menstrual cycling and long COVID symptomatology [22]. For example, long COVID patients report menstrual cycle irregularities, including the length of the cycle, duration, and intensity of the menses [23]. Indeed, long COVID can significantly affect menstrual health, causing changes in flow, cycle length, and pain [23]. Similarly, over 30% of menstruating long COVID patients report long COVID symptom exacerbation the week before or during menses [22]. Taken together, this suggests that long COVID symptomatology alters throughout the menstrual cycle, and the menstrual cycle is also affected by long COVID. Notably, many hallmark symptoms of menopause also appear among the commonly reported symptoms of long COVID [23,24], highlighting a potential overlap between the two conditions, which must be investigated. This overlap is likely to contribute to diagnostic uncertainty, potentially leading to underdiagnosis of perimenopause or menopause, and misdiagnosis of long COVID [25], raising important questions about symptom attribution, diagnostic clarity, and treatment strategies. Although one review has explored menopause in acute COVID patients [26], interest in the intersection between long COVID and menopause has grown significantly in recent years, reflecting the need for a more comprehensive overview. In response, this scoping review, first of its kind to our knowledge, aims to map the existing research on long COVID (and related terms) in relation to menopause. The objectives are to identify and summarise studies examining long COVID (and related terms) across the full menopausal transition, including perimenopause, to capture the breadth of existing evidence in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration

This review was preregistered on OSF on 21 October 2025 (10.17605/OSF.IO/V85BY). At this stage, formal searches had been conducted, but no article screening had commenced. This review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [27].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible in the current review if they examined both long COVID and menopause in their scope, were written in the English language, and were published between 2020 and 2025, given the emergence of COVID. Specifically, perimenopausal, menopausal, or postmenopausal focus was included. Due to the nature of scoping reviews, there were no exclusions to the outcomes, interventions, or variables within these studies.

2.3. Literature Search

A literature search was conducted on CINAHL ultimate, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane, and Scopus by EB from January 2020. Search terms were developed through examination of existing literature and previously published scoping reviews on the topic. For specific search parameters within each database, see Supplementary Materials A. Following study selection, the reference lists of all eligible papers were also screened (titles only).

2.4. Study Selection

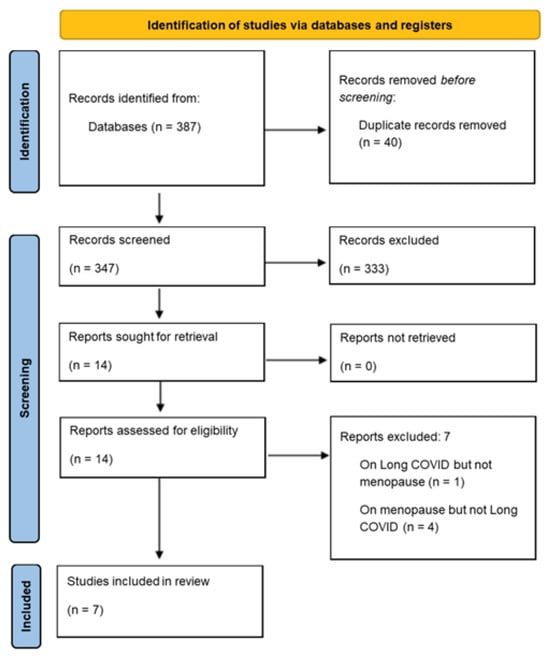

Studies were identified by EB on 21 October 2025. Once database searches were complete, all studies were downloaded to a single reference list using Zotero (software version 7.0.27), and duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were then exported to the Rayyan application [28] by EB for the screening process to begin. All screening was completed between two authors and with blind screening features selected in Rayyan. Specifically, GH and NS-H performed Stage 1 (title and abstract only) and Stage 2 screening (full-text). LH acted as an independent chair, although no disagreements arose. From a search yield of 387, 7 papers were eligible for the current scoping review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extracted from each study included author(s) and publication year, study aims and design, participant information (number, age, ethnicity, inclusion criteria), measures, and findings (See Table S1 in Supplementary Materials B). Data was extracted by SJ and RM. GH verified data extraction.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

Searches yielded 387 articles from five databases (CINAHL ultimate, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane, and Scopus). Once duplicates (k = 40) were removed, 347 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion. In total, fourteen articles were retrieved as full-text and assessed for eligibility. Of those, seven were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were as follows: a lack of focus on both COVID-19 and menopause (k = 5), a focus on the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare services (k = 1), and being a conference abstract without reported findings (k = 1). Seven articles remained, with findings synthesised. The screening process is summarised in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

3.2. Study Types

The study designs included seven observational studies [17,25,29,30,31,32,33]. Four studies were cross-sectional in design [17,25,30,31], and one was retrospective [32]. Two eligible articles were cohort studies, with one prospective [33] and one longitudinal over a three-year duration [29]. The studies’ dates of publication ranged from 2023 to 2025.

3.3. Participant Characteristics

Sample sizes ranged from n = 122 [25] to n = 12,276 [33], with a total of n = 14,810 participants. Overall, 76% of participants were female (n = 11,323). Six studies only recruited females [17,25,29,30,31,32], whereas one recruited a male control group [33] (8969 females and 3307 males). While one study did not report any information on participant age [17], the age of participants ranged from 18 years [25,30,32,33] to 79 years [25,31] in recruitment, with an overall mean age of 47 years (SD = 7.03). Only two studies reported ethnicity [31,33]. In Neuhouser et al. [31], 91% of participants were White, 6% were Black, and 3% were other. In Shah et al. [33], 57% were White, 18% Hispanic, 14% Black, 6% Asian, and 5% other. While long COVID status was reported in all studies, further disease information, such as duration and progression, was absent.

3.4. Study Location/Setting, and Recruitment

All seven articles reported study location; these were Spain [29,30], the United States [31,33], the United Kingdom [17,25], and Japan [32]. In terms of recruitment, four studies accessed data from existing long COVID or women’s health datasets [29,30,31,33], two studies reported recruiting long COVID patients from clinics [25,32], and one recruited volunteers via social media advertising [17].

3.5. Methods

Studies were homogeneous in reporting methods, as all were observational in design. Six articles examined factors via surveys [17,25,29,30,31,33]. Sakurada et al. [32] examined existing hospital records from patients to gain data, with some survey scores reported. Long COVID was measured by self-report from participants in five studies [17,29,30,31,33]. Sakurada et al. [32] determined long COVID status from healthcare professionals’ reporting in patient records. Stewart et al. [25] did not require long COVID reporting in participants, instead identifying symptoms of long COVID present in their sample. Here, long COVID symptomatology was defined from the work of Atchinson et al. [24]. Similarly, six studies determined menopausal status by self-report [17,25,29,30,31,33], whereas one study determined status from hospital records [32].

3.6. Outcome Measures

Long COVID status was examined by self-report from participants [17,25,29,30,31,33] or reporting from a healthcare professional [25,33]. Farré et al. [29] recruited participants from the COVICAT study [34]; therefore, after self-report of long COVID symptoms, a blood sample was taken to confirm status via serological biomarkers. Similarly, Shah et al. [33] recruited participants from the RECOVER cohort, where self-report was confirmed by nucleic acid amplification testing [35].

Six studies measured menopausal status by self-report [17,25,29,30,31,33], whilst one extracted data from existing patients’ medical records [32]. Stewart et al. [25] examined menopause status using Balance’s menopause screening questionnaire [36]—a web-based resource—whereas all other articles used a self-designed item.

Other outcome measures were blood tests used to examine hormone [32] and protein expression [29]. Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [37], COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS) [38], Fried Criteria [39], Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-29 (PROMIS-29) [40], International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [41], Five-Sit-To-Stand test (5STS) [42], and Gaitspeed were examined in Navas-Otero et al. [30]. While no measures were actively completed in their secondary data analysis, Sakurada et al. [32] reported common outcome measures of the Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) [43] and the Euro Quality of Life Five Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L) [44] in patient records.

3.7. Key Findings

Two studies highlighted the similarity of menopause and long COVID symptoms [30,31]. Navas-Otero et al. [30] the most prevalent perimenopausal symptom reported in their sample was depression, a symptom also common in those with long COVID. Individuals experiencing long COVID also reported facing other comorbid symptomology of hot flashes, exhaustion, and sleep disturbances. Neuhouser et al. [31] also identified fatigue as a common symptom of both menopause and long COVID from survey responses, alongside memory issues. Individuals with long COVID and facing perimenopause also showed significantly greater frailty, weakness, and exhaustion than other groups (non-perimenopausal and non-long COVID [30].

Three studies examined how symptoms of menopause and long COVID interact [17,25,32]. In their sample from Hospitals in the North of England, Stewart et al. [25] reported that a higher frequency of long COVID symptoms was recorded in patients aged 40 to 54 years; the age range for menopausal onset was typical, compared to those with long COVID in other age groups. Authors concluded symptoms in this long COVID sample were “highly attributable” to perimenopause or menopause [25]. Similarly, Newson, Lewis, and O’Hara [17] reported that 70% of surveyed participants believed their long COVID symptoms could be a result of perimenopause or menopause transition, although no analysis was conducted on cause and effect. Additionally, 62% reported long COVID symptoms to worsen on the days prior to their period starting, and 50% reported their menstruation stopping or changing following long COVID infection [17]. Sakurada et al. [32] examined hospital records and reported that 20% of female long COVID patients also faced menstrual symptoms. Although, menstrual symptoms accounted for cycle irregularities, severe pain, heavy bleeding, perimenopausal symptoms and premenstrual syndrome. Within the 20% of patients who reported these menstrual complaints, 18% reported perimenopausal symptoms. Authors noted different time periods and variants of long COVID across their sample, with a higher prevalence of menstrual symptoms reported in those with the Omicron variant [32].

Two studies considered the link between menopause and long COVID infection [29,33]. Shah et al. [33] reported that female sex was significantly associated with a 1.31-times-higher risk of long COVID compared to a male sample. However, when females were categorised into menopausal status, no greater risk was reported, suggesting menopause does not directly increase the risk of long COVID. Farré et al. [29] conducted proteomic analysis to examine the expression of proteins in those with long COVID and menopause. Authors concluded the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) protein was significantly overexpressed in the long COVID population, and this overexpression also frequently occurred in menopausal women, suggesting the relationship between menopause and long COVID may be moderated by this specific protein overexpression [29].

Together, findings indicate symptom overlap in long COVID and menopause, particularly around fatigue, mood change, and sleep issues [30,31]. While female sex significantly increased the risk of long COVID, menopausal status did not [33]. This was despite patients self-reporting that experiencing long COVID and menopause together increased symptom severity and frequency [17,25,32]. Therefore, findings suggest menopausal status may not have a causal relationship with long COVID but instead shape the presentation of the condition. Other biological mechanisms, such as protein expression, may also explain the relationship between long COVID and menopause [29].

4. Discussion

This scoping review synthesised the evidence at the intersection of long COVID and menopause. Most participants across the seven included studies were unsurprisingly midlife women, with an overall mean age of 47 years [11]. This is congruent with data indicating that women aged 45–54 are disproportionately affected by long COVID and more likely to experience severe and persistent symptoms, a demographic that also corresponds to the typical age range for the onset of perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause [13,15,16]. These demographic findings underscore the importance of considering menopausal status when evaluating long COVID, as overlapping age and sex-related risk factors may influence both symptom prevalence and severity [22].

Two studies within this review highlighted the similarity of menopause and long COVID symptoms, identifying considerable symptomatic overlap between long COVID and the menopausal transition from self-report data [30,31]. The findings from Navas-Otero et al. [30] and Neuhouser et al. [31] underscore a notable symptomatic convergence between menopause and long COVID, suggesting that women experiencing the menopausal transition may face compounded health challenges if also affected by long COVID. Depression, exhaustion, hot flashes, and sleep disturbances were identified as common features across both conditions, highlighting the potential for diagnostic overlap and symptom misattribution [30]. Neuhouser et al. [31] also reported fatigue as a common symptom of both menopause and long COVID, alongside memory issues. Moreover, Navas-Otero et al. [30] observed that individuals with concurrent long COVID and perimenopausal status exhibited significantly greater exhaustion and physical weakness compared to those without either condition, indicating that the intersection of these conditions may exacerbate functional decline. These observations are consistent with the existing literature emphasising the wide-ranging physiological and psychological impact of long COVID [2,3] and the established symptom burden associated with perimenopause and menopause [16,24]. The overlap in symptomatology not only complicates clinical assessment but also raises important considerations for tailored management strategies, as the co-occurrence of long COVID and menopausal symptoms may increase the need for holistic, multidisciplinary approaches to care. These findings reinforce the importance of recognising the intersection between reproductive ageing and post-viral sequelae, particularly in women aged 40–54, who represent a demographic at heightened risk for both long COVID and menopausal transition [11,18].

Three other studies within this review explored the interaction between long COVID and menstrual or menopausal symptoms [17,25,32]. Stewart et al. [25] reported that long COVID symptoms were most prevalent among women aged 40–54, an age range typically associated with menopausal onset, and concluded that the symptoms were “highly attributable” to perimenopause or menopause. Similarly, Newson, Lewis, and O’Hara [17] found that 70% of participants perceived their long COVID symptoms to be influenced by menopausal transition, with 62% reporting symptom exacerbation preceding menstruation and 50% reporting post-infection changes in menstruation. Sakurada et al. [32] identified menstrual complaints in 20% of female long COVID patients, of whom 18% experienced perimenopausal symptoms. These findings highlight that hormonal fluctuations during the menopausal transition may shape how long COVID symptoms are experienced. This convergence of evidence underscores the importance of clinicians considering reproductive health status, particularly menopausal changes, when assessing and managing long COVID [22].

Two remaining studies in this review examined the potential biological and epidemiological links between menopause and long COVID, providing limited yet insightful evidence on the biological mechanisms underpinning this relationship [29,33]. Shah et al. [33] reported that while female sex was associated with a 1.31-fold increased risk of long COVID, menopausal status did not independently confer additional risk, suggesting that the relationship between hormonal status and long COVID is complex and may be moderated by additional biological or environmental factors. Farré et al. [29] conducted proteomic analysis, identifying overexpression of VEGFA protein in both menopausal women and individuals with long COVID, indicating potential shared pathophysiological pathways. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating objective biomarkers and biological investigations in future research to clarify the interplay between sex, hormones, and long COVID pathogenesis.

The current scoping review holds limitations. Its narrow focus, examining only long COVID and menopause, may have excluded other factors that could impact this relationship. As no eligible studies reported direct, significant causal effects between menopause and long COVID, adopting a broader scope may have resulted in further insight gained. Although, the fixed nature of menopausal stages and distinct differences between acute and long COVID diagnosis meant this was not possible. Given the recent recognition and diagnoses of long COVID, future scoping reviews in this area may provide further insight as research has progressed. Although, the current review can act as a call for further research in this area. Furthermore, findings highlight overlapping symptomatology between menopausal stages and long COVID. This overlap raises the possibility of misdiagnosis of long COVID or menopause. This questions the rigour for both clinical diagnosis and research screening of participants. Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, risk of bias was present across studies, particularly selection and self-selection bias, as many samples were drawn from existing datasets, clinics, or volunteer recruitment via social media, which may overrepresent individuals with more severe or persistent symptoms. Second, measurement validity was limited by heavy reliance on self-report for both long COVID status and menopausal status in most studies (k = 5), increasing susceptibility to recall bias, symptom misattribution, and overlap between menopause- and long COVID–related symptom reporting. Although two studies strengthened validity through biomarker or clinical confirmation, these approaches were not consistently applied [29,32]. Limited reporting of ethnicity and socio-demographic characteristics restricts generalisability, as experiences of menopausal transition and long COVID symptomatology may vary across populations [31,33]. Together, these methodological issues may partly explain inconsistencies in findings regarding the relationship between menopausal status and long COVID risk versus symptom experience. Future research should prioritise longitudinal designs to elucidate symptom trajectories, standardised and validated measures for both long COVID and menopausal status, and the incorporation of hormonal and immunological biomarkers to investigate underlying mechanisms. Moreover, increasing diversity in study populations and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration across immunology, endocrinology, and women’s health research will be essential to advance understanding and inform the development of targeted clinical interventions.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review highlights significant symptomatic overlap between long COVID and menopause, particularly in midlife women, with fatigue, cognitive difficulties, mood changes, and sleep disturbances commonly reported. While menopausal status did not significantly increase the risk of long COVID, preliminary evidence from self-report data suggests that hormonal fluctuations may influence symptom severity. Although, biological mechanisms remain insufficiently understood. Methodological limitations restrict generalisability, underscoring the need for longitudinal symptom tracking, diverse samples, and biomarker-informed studies. Recognising the intersection of long COVID and menopausal transition is essential for improving assessment, management, and targeted care for affected women. Building on this, greater clinical awareness of menopausal status in women with long COVID, alongside routine screening and multidisciplinary care, may help reduce misdiagnosis and support more personalised management. Similarly, future research should focus on longitudinal, standardised, and biomarker-informed studies in long COVID and menopausal transition to clarify underlying mechanisms and inform targeted interventions for midlife women.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/covid6010007/s1, Supplementary Materials A; Table S1: data extraction table in Supplementary Materials B.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.E.M.S.-H. and L.D.H.; methodology, N.E.M.S.-H., E.B. and G.H.; software, E.B.; validation, N.E.M.S.-H., L.D.H., G.H., R.M., S.J. and E.B.; formal analysis, N.E.M.S.-H. and G.H.; investigation, N.E.M.S.-H., E.B. and G.H.; resources, N.E.M.S.-H. and G.H.; data curation, G.H. and N.E.M.S.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E.M.S.-H. and G.H.; writing—review and editing, L.D.H., S.J., R.M., E.B., G.H. and N.E.M.S.-H.; visualisation, G.H.; supervision, N.E.M.S.-H.; project administration, N.E.M.S.-H.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank T’Challa, Bagheera, Dobson, and Norman for their unwavering support with this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE); Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA); Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA).

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19 (NG188). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Hayes, L.D.; Ingram, J.; Sculthorpe, N.F. More Than 100 Persistent Symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 (Long COVID): A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 750378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, O.; Silva Passadouro, B.; Mulvey, M.; Delis, I.; Astill, S.; Tan, A.L.; Sivan, M. Clinical Characteristics and Mechanisms of Musculoskeletal Pain in Long COVID. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 1729–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, C.X.; Wyller, V.B.B.; Moss-Morris, R.; Buchwald, D.; Crawley, E.; Hautvast, J.; Katz, B.Z.; Knoop, H.; Little, P.; Taylor, R.; et al. Long COVID and Post-infective Fatigue Syndrome: A Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twomey, R.; DeMars, J.; Franklin, K.; Culos-Reed, S.N.; Weatherald, J.; Wrightson, J.G. Chronic Fatigue and Postexertional Malaise in People Living with Long COVID: An Observational Study. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzac005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, J.X.; Li, X.H.; Su, Z.; Cheung, T.; Lok, K.-I.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Prevalence of Poor Sleep Quality in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1272812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Daines, L.; Han, Q.; Hurst, J.R.; Pfeffer, P.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Elneima, O.; Walker, S.; Brown, J.S.; Siddiqui, S.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Treatments for Post-COVID-19 Breathlessness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Cristillo, V.; Cotti Piccinelli, S.; Zoppi, N.; Bonzi, G.; Sattin, D.; Schiavolin, S.; Raggi, A.; Canale, A.; Gipponi, S.; et al. Long-Term Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: Prevalence and Predictive Factors. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 4903–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Jayadevan, R.; Sashidharan, S. Long COVID: An Overview. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021, 15, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Davis, H.; McCorkell, L.; Soares, L.; Wulf-Hanson, S.; Iwasaki, A.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID Science, Research and Policy. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2148–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Self-Reported Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infections and Associated Symptoms, England and Scotland: November 2023 to March 2024. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/selfreportedcoronaviruscovid19infectionsandassociatedsymptomsenglandandscotland/november2023tomarch2024 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Mateu, L.; Tebe, C.; Loste, C.; Santos, J.R.; Lladós, G.; López, C.; España-Cueto, S.; Toledo, R.; Font, M.; Chamorro, A.; et al. Determinants of the Onset and Prognosis of the Post-COVID-19 Condition: A 2-Year Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 33, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, M.; Elliott, J.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; Riley, S.; Darzi, A.; Cooke, G.; Ward, H.; Elliott, P. Persistent COVID-19 Symptoms in a Community Study of 606,434 People in England. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhaber, N.H.; Ogan, W.S.; Greaves, A.; Tai-Seale, M.; Sitapati, A.; Longhurst, C.A.; Horton, L.E. Population-Based Evaluation of Postacute COVID-19 Chronic Sequelae. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J.Ž. Long COVID: A Clinical Update. Lancet 2024, 404, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Menopause—Clinical Knowledge Summary. Available online: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/menopause/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Newson, L.; Lewis, R.; O’Hara, M. Long COVID and Menopause—The Important Role of Hormones. Maturitas 2021, 152, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Newson, L.; Briggs, T.A.; Grammatopoulos, D.; Young, L.; Gill, P. Long COVID Risk—A Signal to Address Sex Hormones and Women’s Health. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 11, 100000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maham, S.; Yoon, M.S. Clinical Spectrum of Long COVID: Effects on Female Reproductive Health. Viruses 2024, 16, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.T.; Heaton, N.S. The Impact of Estrogens and Their Receptors on Immunity and Inflammation During Infection. Cancers 2022, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, D.M.; Whettlock, E.M.; Liu, S.; Arachchillage, D.J.; Boyton, R.J. The Immunology of Long COVID. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, B.; von Saltza, E.; McCorkell, L.; Santos, L.; Hultman, A.; Cohen, A.K.; Soares, L. Female Reproductive Health Impacts of Long COVID and Associated Illnesses Including ME/CFS, POTS and Connective Tissue Disorders: A Literature Review. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2023, 4, 1122673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing Long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchison, C.J.; Davies, B.; Cooper, E.; Lound, A.; Whitaker, M.; Hampshire, A.; Azor, A.; Donnelly, C.A.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; Cooke, G.S.; et al. Long-Term Health Impacts of COVID-19 Among 242,712 Adults in England. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Heald, A.; Pyne, Y.; Bakerly, N.D. Menopause Symptom Prevalence in Three Post–COVID-19 Syndrome Clinics in England: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. IJID Reg. 2024, 12, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, A.; Zarifian, A.; Hadizadeh, A.; Hajmolarezaei, E. Incidence and Outcomes Associated with Menopausal Status in COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2023, 45, e796–e807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, X.; Blay, N.; Iraola-Guzmán, S.; Fernández-Jiménez, F.; Alzate-Piñol, S.; Llucià-Carol, L.; Espinosa, A.; Castaño-Vinyals, G.; Dobaño, C.; Moncunill, G.; et al. VEGFA Sex-Specific Signature Is Associated with Long COVID Symptom Persistence. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Otero, A.; Calvache-Mateo, A.; Martín-Núñez, J.; Calles-Plata, I.; Ortiz-Rubio, A.; Valenza, M.C.; López, L.L. Characteristics of Frailty in Perimenopausal Women with Long COVID-19. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhouser, M.L.; Butt, H.I.; Hu, C.; Shadyab, A.H.; Garcia, L.; Follis, S.; Mouton, C.; Harris, H.R.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Gower, E.W.; et al. Risk Factors for Long COVID Syndrome in Postmenopausal Women. Ann. Epidemiol. 2024, 98, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurada, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Motohashi, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Otsuka, Y.; Nakano, Y.; Tokumasu, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Sunada, N.; Honda, H.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Female Long COVID Patients with Menstrual Symptoms: A Retrospective Study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 45, 2305899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.P.; Thaweethai, T.; Karlson, E.W.; Bonilla, H.; Horne, B.D.; Mullington, J.M.; Wisnivesky, J.P.; Hornig, M.; Shinnick, D.J.; Klein, J.D.; et al. Sex Differences in Long COVID. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2455430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, X.; Castaño-Vinyals, G.; Espinosa, A.; Carreras, A.; Liutsko, L.; Sicuri, E.; Foraster, M.; O’cAllaghan-Gordo, C.; Dadvand, P.; Moncunill, G.; et al. Mental Health and COVID-19 in a General Population Cohort in Spain (COVICAT Study). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 2457–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, L.I.; Thaweethai, T.; Brosnahan, S.B.; Cicek, M.S.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Goldman, J.D.; Hess, R.; Hodder, S.L.; Jacoby, V.L.; Jordan, M.R.; et al. Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER): Adult Study Protocol. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, L. Menopause Symptom Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.balance-menopause.com/menopause-library/menopause-symptom-sheet/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Charlson, M.; Szatrowski, T.P.; Peterson, J.; Gold, J. Validation of a Combined Comorbidity Index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994, 47, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.J.; Preston, N.; Parkin, A.; Makower, S.; Ross, D.; Gee, J.; Halpin, S.J.; Horton, M.; Sivan, M. The COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS): Application and Psychometric Analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Spritzer, K.L.; Schalet, B.D.; Cella, D. PROMIS-29 v2.0 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scores. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallal, P.C.; Victora, C.G. Reliability and Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Kon, S.S.; Canavan, J.L.; Patel, M.S.; Clark, A.L.; Nolan, C.M.; Polkey, M.I.; Man, W.D.-C. The Five-Repetition Sit-to-Stand Test as a Functional Outcome Measure in COPD. Thorax 2013, 68, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, J.; Michielsen, H.; Van Heck, G.L.; Drent, M. Measuring Fatigue in Sarcoidosis: The Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS). Br. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiroiwa, T.; Ikeda, S.; Noto, S.; Igarashi, A.; Fukuda, T.; Saito, S.; Shimozuma, K. Comparison of Value Sets Based on DCE and/or TTO Data: Scoring for EQ-5D-5L Health States in Japan. Value Health 2016, 19, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.