Abstract

Introduction: Immune dysfunction plays a significant role in Metabolic syndrome, contributing to both insulin resistance and chronic low-grade inflammation. This immune dysfunction is characterized by overproduction of inflammatory cytokines among which of primary importance are tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and (MCP-1), whereas others such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ), IL-17A, and the anti-inflammatory IL-10 appear to be of secondary importance. Cytokines also play a significant role in Post-COVID disorders contributing to prolonged immune dysregulation and persistent subclinical inflammation. However, their role in the newly emerging metabolic disorders following infection remains poorly defined. Methods and materials: In the current study 78 patients (26 men and 52 women) were included, divided into two groups—group 1 (individuals with newly diagnosed carbohydrate disorders after proven COVID-19 or Post-COVID group; n = 35) and group 2 (COVID-19 negative persons with Metabolic Syndrome; n = 33). They were further divided into several subgroups according to type of metabolic disorder present. Standard biochemical, hormonal and immunological parameters were measured using ELISA and ECLIA methods, as well as some indices for assessment of insulin resistance were calculated using the corresponding formula. Results: Patients from both groups demonstrate similar metabolic parameters including BMI and unadjusted lipid and uric acid levels (p > 0.05). After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI revealed significant differences, Post-COVID status independently predicted higher fasting glucose, HbA1c, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, uric acid, and insulin-resistance indices, indicating substantially impaired glycemic and metabolic control beyond traditional risk factors. Furthermore, the Post-COVID cohort demonstrated marked cytokine dysregulation, with significantly elevated levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17A, and IL-10 after adjustment. Conclusions: The observed changes in both metabolic and immune parameters studied among the two groups show many similarities, but some significant differences have also been identified. Together, these findings indicate that Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction is characterized by inflammation-driven dyslipidemia, heightened oxidative stress, and persistent immune activation, distinguishing it from classical Metabolic syndrome.

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined as a combination of interrelated physiological, biochemical, clinical, and metabolic factors that directly increase the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), type 2 Diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and all-cause mortality [1,2]. This constellation of metabolic abnormalities includes central obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, dysglycemia (various deviations in carbohydrate glucose tolerance), pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic state [3].

Insulin resistance (IR) and chronic low-grade inflammation are considered major, interconnected characteristics and core components of the pathogenesis of MetS with both immune and adipose tissue dysfunction playing an essential role in their emergence and maintenance [4].

Immune dysfunction, driven by a complex interplay between adipocytes and immune cells, plays a significant role in MetS, contributing to both IR and chronic low-grade inflammation [5]. This immune dysfunction is characterized by overproduction of inflammatory cytokines released from activated immune cells, especially macrophages, further impairing insulin signaling and promoting inflammation, creating a feedback loop that worsens metabolic dysfunction [6]. Major cytokines implicated in low-grade inflammatory state in MetS are tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1) [7], whereas others such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ), IL-17A, and the anti-inflammatory IL-10 appear to be of secondary importance [8,9,10].

Interestingly, IR and adipocyte dysfunction are also observed in the course and after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and they also show a link to the immune dysregulation induced by the virus [11]. Adipose tissue dysfunction in the course of COVID-19 is characterized by an increase in leptin levels and accompanying leptin resistance as well as dramatic decrease in adiponectin levels [11,12].

Cytokine storm, a hyper-inflammatory state with an overproduction of inflammatory cytokines, is a key feature of COVID-19 and is associated with disease severity and negative outcomes, including death [13]. Among the numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines that are elevated during a cytokine storm, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ are considered of paramount importance [14]. Cytokines also play a significant role in Post-COVID disorders by modulating the immune response, contributing to prolonged immune dysregulation and persistent subclinical inflammation (known as “smoldering cytokine activation”). However, their role in the newly emerging metabolic disorders following infection remains poorly defined [15].

To what extent immune system and metabolic disorders are similar in newly emerging metabolic disorders, including DM and prediabetes, compared to those observed in classic MetS, without prior SARS-CoV-2 exposure, is still not revealed and is yet to come.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A prospective observational study was conducted on 68 patients (16 men and 52 women) who attended the Clinic of Endocrinology and Metabolic Diseases at our hospital for active treatment. In order to investigate if there are common pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in the genesis of carbohydrate disorders and IR arising after COVID-19 and those observed in the classical MetS, individuals were selected according to precisely defined criteria and divided into two groups and similar diagnostic, metabolic, biochemical and hormonal aspects were studied in each of them.

2.2. Studied Population

The study population includes 2 groups of patients in the age range between 21 and 71 years:

(1) Group 1 (Post-COVID group): 35 individuals with newly diagnosed carbohydrate disorders after proven COVID-19 (Post-COVID group). All individuals were non-vaccinated and had a history of a positive PCR test for COVID-19 at least 6 months before they were newly diagnosed with carbohydrate disorders.

Only six patients (n = 6; 17.14%) of the total cohort required hospitalization for management of COVID-19-related symptoms. In this hospitalized subset, disease severity was clinically classified as moderately severe, characterized by confirmed pneumonia on imaging with stable vital signs, specifically maintaining oxygen saturation (SpO2 ≥ 94%) on room air and a respiratory rate (RR) < 30 breaths per minute. None of the hospitalized patients required supplemental oxygen therapy or intensive care unit admission. Clinical management protocols adhered to established guidelines for COVID-19 treatment prevalent during the study period, involving a combination therapy of antibiotics, a low-dose glucocorticoid regimen (e.g., methylprednisolone 32 mg or dexamethasone 6 mg daily or equivalent), anticoagulants, and symptomatic agents. The majority of participants (n = 29 individuals; 82.86%) received treatment on an outpatient basis. The outpatient treatment protocol also adhered to established guidelines for COVID-19 treatment. Clinical data regarding the specific grading of disease severity (e.g., mild vs. moderate) was not available for the non-hospitalized outpatient cohort.

All of the individuals in the group (n = 35) were further diagnosed with type 1 Diabetes mellitus (T1DM), T2DM and prediabetic conditions—impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), as well as normoglycemic patients with IR and/or hyperinsulinemia. Diagnosis DM was made according to the WHO criteria (2019) [16]. Prediabetic conditions (IFG, IGT) were diagnosed according to the WHO criteria (2015) [17]. IR and hyperinsulinemia were diagnosed based on serum insulin levels during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). All participants in Group 1 had newly diagnosed metabolic disorders and had not received any prior pharmacological treatment, including metformin or other antidiabetic agents, before enrollment.

(2) Group 2 (COVID-negative group): 33 individuals with MetS who did not suffer from COVID-19 and were not previously vaccinated (COVID-19 negative). The diagnosis of MetS was made according to the IDF criteria (2009) [3]. They were also divided into the aforementioned subgroups (with the exception of T1DM subgroup)—T2DM, IFG, IGT and IR and/or hyperinsulinemia. In Group 2, 24 participants were newly diagnosed and untreated, whereas nine had previously diagnosed T2DM and were receiving non-insulin antidiabetic therapy.

2.2.1. Including Criteria

- -

- Age over 18 years

- -

- History of COVID-19 (diagnosed with a positive PCR test) more than 3 months after the acute phase of the disease—for group 1

- -

- History of normal blood sugar before COVID-19—for group 1

- -

- Metabolic syndrome—for group 2

2.2.2. Excluding Criteria

- -

- Age under 18 and over 90 years of age

- -

- Pregnancy and breastfeeding

- -

- Patients with T1DM or T2DM prior to COVID-19 infection—for group 1

- -

- Immunization with anti-COVID-19 vaccines

- -

- Autoimmune disease present

- -

- Patients with severe, decompensated diseases of the cardiovascular system, respiratory system, gastrointestinal tract, excretory system, presence of oncological diseases

- -

- Use of biological therapy, immunosuppressants, and cytostatics in the previous 12 months

- -

- Use of glucocorticoids (during COVID treatment) in dose greater than 0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day of methylprednisolone (or an equivalent) for up to 10 days

2.3. Methods

All individuals included underwent a survey, anthropometric measurements (body mass index, BMI) and basic clinical exam. Laboratory tests were performed after informed consent was signed by the patients.

Standard biochemical parameters were evaluated including fasting plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), lipid profile parameters (Total cholesterol, Triglycerides (TG), High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)) and Uric acid.

Hormonal parameters related to the regulation of metabolic homeostasis as fasting insulin, leptin and adiponectin were also evaluated.

Immunological markers including IL-17A along with TNF-α and INF-γ levels were monitored as potent pro-inflammatory cytokines implicated in both COVID-19 and MetS-related immune disturbances pathogenesis, as well as IL-10 levels—an anti-inflammatory cytokine.

The hormonal samples were studied by electrochemiluminescent immunoassay (ECLIA), following protocol, on an automatic analyzer. All immunological samples, as well as the samples for some of the hormonal studies, were investigated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercial kits.

All samples were processed in duplicate (tested twice) to ensure technical reproducibility.

For several of the analyzed immunological indicators for which generally accepted reference values are not standardized in the literature, a rigorous calibration procedure was implemented. A laboratory-specific standard curve was generated for these indicators, which subsequently defined the internal lower and upper limits of normal values used for data interpretation within this study.

Insulin resistance was determined using IR indices, calculated according to the corresponding formula:

- (1)

- Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)

This index is calculated as HOMA-IR = Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) × Fasting insulin (µIU/mL)/22 [18].

- (2)

- Metabolic Score for Insulin Resistance (METS-IR)

METS-IR is calculated using the formula: METS-IR = (ln ((2 × fasting glucose (mg/dL) + triglycerides (mg/dL)) × BMI (kg/m2))/(ln (HDL-C (mg/dL)). The glucose, triglycerides, and HDL-C values are first converted to the appropriate units of measurement using the following formulas: glucose (mg/dL) = glucose (mmol/L) × 18.018; triglycerides (mg/dL) = triglycerides (mmol/L) × 88.57; HDL-C (mg/dL) = HDL-C (mmol/L) × 38.67

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25. Quantitative variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile range (IQR); in tables, median and range are additionally provided.

Normality of distribution was assessed using both the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. As at least one group for each variable demonstrated a non-normal distribution, non-parametric statistical methods were applied. Group and subgroups comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and only comparisons with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Only metabolically matched subgroups were compared between the Post-COVID group (Group 1) and the COVID-negative group (Group 2). The T1DM subgroup, present exclusively in Group 1, was excluded from all inter-group statistical comparisons due to the lack of a corresponding subgroup in Group 2.

To determine whether Post-COVID status independently predicted biomarker levels, generalized linear models (GLMs) with a Gamma distribution and log link (Gamma-GLM) were performed. This model was selected due to the positively skewed distribution of all biochemical markers and its suitability for modeling multiplicative effects.

Each model included age, sex, and BMI as covariates, chosen a priori based on established biological relevance. Results are reported as exponentiated coefficients (fold-change), where values >1 indicate higher adjusted levels in the Post-COVID group.

Associations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs). Only correlations with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Due to the small sample size in several metabolic subgroups (n ≤ 10), 95% confidence intervals (CI) for correlation coefficients were also reported to support interpretation.

2.5. Ethical Aspects

The study is performed after receiving ethical approval from the Ethical Commission of Medical University Pleven—Protocol №72/23.06.23. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each person included in the study declared their voluntary willingness to participate in the study and gave their consent for the publication of their de-identified clinical data by signing and dating the consent form. The researcher also signed the informed consent, declaring his obligation to comply with the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. No psychological pressure was allowed on the volunteers to sign the informed consent.

2.6. Limitations of the Study

This study is limited by the relatively small sample size within metabolic subgroups, which limited the feasibility of adjusted subgroup analyses. In addition, the absence of a healthy control group restricts comparisons to metabolically affected populations only. Finally, detailed clinical data on COVID-19 severity were unavailable for the non-hospitalized post-COVID cohort, limiting assessment of severity-dependent metabolic effects.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristic

The main demographic features of the population studied are presented in the table below (Table 1). As seen, the mean age of the patients was 46.76 ± 4.74 years old with group 2 (COVID-19 negative subjects with MetS) being older (48.21 ± 4.51 years) and group 1 (patients with new onset carbohydrate disorder following COVID-19, Post-COVID group) being younger (45.35 ± 4.98 years) with significant difference between the groups (p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Basic clinical characteristics of the studied population.

Female predominance was most pronounced in the COVID-negative group (group 2) where females comprised 90.90% of all, while in the Post-COVID group (group 1), women accounted for 62.85% of the group.

Almost half of the individuals (42.65%) had a positive family history of DM—40% in group 1 and 45.45% in group 2, respectively.

Table 2 comprises distribution of the patients according to the type of metabolic disorder present. Group 1 included a total of 35 individuals with newly emerging carbohydrate disorders after previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Post-COVID group). In the studied group, a total of 19 individuals (54.28%) had newly diagnosed DM–8 of them were diagnosed with T1DM, including LADA (22.85%), while the remaining 11 individuals (31.43%) were diagnosed with T2DM. Prediabetes as IGT was found in 3 individuals (8.57%), and as IFG in 4 patients (11.43%). The remaining 9 individuals were normoglycemic (25.72%) with data for basal and/or stimulated hyperinsulinemia and IR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the patients (N, %) from both group 1 (post-COVID group) and group 2 (COVID-negative group) according to the type of carbohydrate disorder.

Group 2 comprises 33 individuals with a negative PCR test and no history of COVID-19 vaccination/exposure (COVID-negative group) and accompanying MetS. MetS was diagnosed according to IDF criteria. Of these, 11 individuals (33.33%) had a diagnosis of T2DM. The remaining individuals had prediabetes including 3 with IFG (9.09%), 4 with IGT (12.12%) and the remaining normoglycemic 15 (45.45%) had data for basal and/or hyperinsulinemia and IR (Table 2).

A comparison of the distribution of metabolic disorder subgroups between Group 1 (Post-COVID) and Group 2 (COVID-negative) was performed using Fisher’s exact test (due to small expected cell counts). No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups for T2DM (p = 1.000), IFG (p = 1.000), IGT (p = 1.000), or IR (p = 1.000). This indicates that the subgroup composition was comparable between the two cohorts. T1DM was not included in the subgroup comparisons between Group 1 and Group 2, as no corresponding T1DM subgroup was available in Group 2.

3.2. Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI values differed between the two studied groups, with individuals in the Post-COVID group showing lower BMI (mean ± SD: 31.91 ± 2.57 kg/m2; median 32.0 kg/m2; IQR 10.0) compared with the COVID-negative group (35.67 ± 7.89 kg/m2; median 35.0 kg/m2; IQR 13.0). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

All patients from the Post-COVID group (group 1), except those with T1DM, had BMI values > 30 kg/m2 (ranging from 23 to 49 kg/m2). BMI was studied among the different subgroups (according to the disorder present) and as expected, the T1DM subgroup reported mean BMI values within the normal body weight range (mean ± SD: 23.63 ± 1.92 kg/m2; median 24.0 kg/m2; IQR 1.92). The highest mean BMI values were reported in the subgroup of individuals with T2DM (mean ± SD: 36.64 ± 6.33 kg/m2; median 36.0 kg/m2; IQR 5.0) and those with IR and/or hyperinsulinemia (mean ± SD: 33.33 ± 7.87 kg/m2; median 34.0 kg/m2; IQR 11.0). Patients with IFG (mean ± SD: 32.75 ± 3.30 kg/m2; median 32.5 kg/m2; IQR 2.75) and IGT (mean ± SD: 31.0 ± 4.24 kg/m2; median 31.0 kg/m2; IQR 3.0) demonstrated quite similar values of mean BMI.

Evaluation of BMI across the metabolic subgroups in the COVID-negative group (Group 2) showed that all individuals had elevated BMI values (>30 kg/m2), with an overall range of 23–48 kg/m2, indicating a predominantly obese population. The T2DM subgroup demonstrated the highest BMI levels (mean ± SD: 38.45 ± 7.85 kg/m2; median 37.0 kg/m2, IQR 13.0), exceeding the average BMI of the overall group. This was followed by the IGT subgroup (mean ± SD: 37.75 ± 5.91 kg/m2; median 36.0 kg/m2, IQR 6.25). Individuals with IFG exhibited the lowest BMI values (mean ± SD: 32.0 ± 10.82 kg/m2; median 29.0 kg/m2, IQR 10.5), whereas the IR subgroup showed comparable levels (mean ± SD: 33.8 ± 7.75 kg/m2; median 35.0 kg/m2, IQR 11.0). Despite these numerical differences, none of the comparisons reached statistical significance (p > 0.05).

3.3. Lipid Profile Parameters

Patients from both groups demonstrated comparable total cholesterol levels, with no statistically significant difference in the unadjusted Mann–Whitney U comparison (p > 0.05). In the Post-COVID group (Group 1), the mean total cholesterol level was 4.87 ± 1.46 mmol/L (median 4.8 mmol/L; IQR 1.07), similar to the COVID-negative group (Group 2), where average levels were 4.89 ± 1.14 mmol/L (median 4.7 mmol/L; IQR 1.30).

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, total cholesterol was significantly higher in the Post-COVID group (B = 1.71; 95% CI: 1.13–2.29; p < 0.001), corresponding to a 5.52-fold increase (95% CI: 3.10–9.84).

Across subgroups, the highest cholesterol levels were found in the IFG subgroups of both groups, whereas the lowest levels were observed in the IR subgroup of Group 1 and the IGT subgroup of Group 2. No statistically significant differences between corresponding subgroups were detected (all p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Lipid profile parameters including Total cholesterol, Triglycerides, HDL-C and LDL-C levels (mmol/L) and Uric acid levels (µmol/L) in metabolic subgroups from the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD, median (range). Statistical significance is based on Mann–Whitney U test.

Mean TG levels did not differ significantly between the two groups (p > 0.05). The Post-COVID group showed values of 1.88 ± 0.84 mmol/L (median 1.57 mmol/L; IQR 1.08), which were comparable to those in the COVID-negative group (1.90 ± 0.82 mmol/L, median 1.64 mmol/L; IQR 0.94). No significant differences emerged in subgroup analyses. The highest TG levels were seen in the IGT subgroup of Group 1 and the T2DM subgroup of Group 2.

After adjustment, TG levels were significantly elevated in the Post-COVID group (B = 1.25; 95% CI: 0.42–2.09; p = 0.003), equivalent to a 3.50-fold increase (95% CI: 1.52–8.07).

Unadjusted HDL-C levels were slightly higher in the Post-COVID group (mean 0.96 ± 0.37 mmol/L, median 0.94; IQR 0.37) compared with the COVID-negative group (mean 0.87 ± 0.23 mmol/L, median 0.81; IQR 0.33), though the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

However, adjusted analysis revealed significantly lower HDL-C levels in the Post-COVID group (B = −0.81; 95% CI: –1.55 to –0.07; p = 0.031), representing a 0.45-fold decrease (95% CI: 0.21–0.93).

When comparing corresponding subgroups, no significant differences emerged. Most subgroups in the Post-COVID group had marginally higher HDL-C values, except for the IR subgroup. Only both IFG subgroups presented average HDL-C within the normal range (Table 3).

Individuals in the COVID-negative group exhibited slightly higher LDL-C levels (3.16 ± 0.96 mmol/L, median 3.20; IQR 1.08) than those in the Post-COVID group (3.10 ± 1.36 mmol/L, median 2.97; IQR 1.23), though the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Adjusted analysis showed that LDL-C levels were significantly higher in the Post-COVID group (B = 1.38; 95% CI: 0.54–2.22; p = 0.001), corresponding to a 3.97-fold increase (95% CI: 1.71–9.23).

Across subgroups, the highest LDL-C values were noted in the IFG subgroups of both groups. Most subgroups exceeded recommended LDL-C thresholds, except for the IGT subgroup in the COVID-negative group, which exhibited borderline values (median 2.31 mmol/L; IQR 0.86) (Table 3).

3.4. Uric Acid

Serum uric acid concentrations were assessed in both groups, revealing slightly higher values in the COVID-negative MetS group compared with the Post-COVID cohort. Individuals in the COVID-negative group demonstrated mean ± SD levels of 415.04 ± 101.37 µmol/L (median 391.0 µmol/L; IQR 77.0 µmol/L), whereas subjects in the Post-COVID group exhibited somewhat lower mean values of 398.23 ± 101.58 µmol/L (median 378.5 µmol/L; IQR 153.5 µmol/L). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

In contrast, adjusted Gamma GLM analysis revealed a markedly different pattern. After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, uric acid levels were significantly higher in the Post-COVID group (B = 5.86; 95% CI: 5.38–6.33; p < 0.001). This effect corresponds to a 350-fold elevation in uric acid concentrations in Post-COVID individuals compared with COVID-negative subjects (95% CI: 218–563).

Comparisons across the corresponding metabolic subgroups likewise showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05), with uric acid levels distributed similarly between Post-COVID and COVID-negative individuals across all metabolic categories (Table 3).

3.5. Glycemic Parameters

Fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c levels were evaluated across the study population. Individuals in the Post-COVID group (Group 1) demonstrated significantly higher fasting plasma glucose levels compared with the COVID-negative group (Group 2) (Mann–Whitney U = 745.5; p = 0.01). Mean glucose concentrations in the Post-COVID group were 7.64 ± 3.69 mmol/L (median 6.24 mmol/L; IQR 3.21), whereas those in the COVID-negative group averaged 5.69 ± 1.76 mmol/L (median 5.03 mmol/L; IQR 1.14).

As expected, HbA1c levels were also higher in the Post-COVID group (mean ± SD: 8.00 ± 2.69%; median 7.20%; IQR 4.31) compared with the COVID-negative group (7.04 ± 1.40%; median 6.61%; IQR 2.19), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

To determine whether Post-COVID status independently predicted alterations in glycemic control, a Gamma GLM with log link was applied for both glucose and HbA1c, adjusting for age, sex, and BMI. Post-COVID status remained a strong independent predictor of elevated fasting glucose (B = 2.70; 95% CI: 1.92–3.48; p < 0.001), corresponding to an estimated 14.9-fold increase in glucose levels relative to the COVID-negative group (95% CI: 6.80–32.60; N = 33). Likewise, HbA1c was significantly higher among Post-COVID individuals after adjustment (B = 2.66; 95% CI: 1.99–3.33; p < 0.001), reflecting an approximately 14.3-fold elevation (95% CI: 7.35–27.87; N = 23) compared with COVID-negative patients.

3.6. Hormonal Parameters

Major adipokines—leptin and adiponectin concentrations were assessed across both study groups. Individuals in the COVID-negative group (Group 2) exhibited higher leptin levels (mean ± SD: 52.02 ± 34.59 ng/mL; median 43.86 ng/mL; IQR 63.34) compared with the Post-COVID group (Group 1: 32.14 ± 25.69 ng/mL; median 22.81 ng/mL; IQR 37.26), although this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Consistently, no significant differences in leptin concentrations were observed when comparing the corresponding metabolic subgroups between groups (all p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adipokines levels—leptin (ng/mL) and adiponectin (µg/mL) in metabolic subgroups from the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD, median (range). Statistical significance is based on Mann–Whitney U test.

Using a Gamma GLM with log link adjusted for age, sex, and BMI, Post-COVID status was associated with a non-significant elevation in leptin levels (B = 1.46; 95% CI: −0.39 to 3.31; fold-change = 4.30; 95% CI: 0.67–27.34; p = 0.123).

Adiponectin levels were comparable between the two study groups (Group 1: 25.03 ± 1.84 μg/mL; median 25.72 μg/mL; IQR 1.58 vs. Group 2: 25.87 ± 0.60 μg/mL; median 25.94 μg/mL; IQR 0.72), with no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). Likewise, adiponectin levels were similar across all individual metabolic subgroups (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

However, when adjusted for age, sex, and BMI using a Gamma GLM, Post-COVID status emerged as a strong independent predictor of adiponectin levels. Post-COVID individuals demonstrated markedly elevated adiponectin, with an estimated 2.4 × 104-fold increase relative to COVID-negative subjects (B = 10.07; 95% CI: 9.93–10.22; fold-change = 23.73; 95% CI: 20.605–27.337; p < 0.001).

3.7. Insulin Resistance Indices (HOMA-IR and METS-IR)

Insulin resistance was evaluated using both HOMA-IR and METS-IR. Patients in both the Post-COVID group (Group 1) and the COVID-negative group (Group 2) demonstrated elevated IR levels. Mean HOMA-IR values were slightly higher in the COVID-negative group (mean ± SD: 8.40 ± 17.67; median 3.29; IQR 3.82) compared with the Post-COVID group (mean ± SD: 7.41 ± 11.37; median 4.13; IQR 3.05), although the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). A similar pattern was observed for METS-IR, with higher mean levels in the COVID-negative group (mean ± SD: 61.19 ± 17.21; median 59.27; IQR 25.46) than in the Post-COVID group (mean ± SD: 55.26 ± 18.30; median 50.18; IQR 19.74), without reaching significance (p > 0.05).

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI using a Gamma GLM with log link, both IR indices (HOMA-IR and METS-IR) showed significantly higher values in the Post-COVID group compared with the COVID-negative group.

For HOMA-IR, Post-COVID individuals demonstrated significantly higher adjusted values (B = 2.19; 95% CI: 0.56–3.83; p = 0.0086), corresponding to an 8.96-fold increase (95% CI: 1.74–46.05). METS-IR was likewise significantly elevated in the Post-COVID group (B = 3.55; 95% CI: 2.97–4.13; p < 0.001), indicating a 34.81-fold higher adjusted level (95% CI: 19.50–62.14).

Levels of HOMA-IR were evaluated across the different subgroups in both the Post-COVID group (Group 1) and the COVID-negative group (Group 2) (Table 5). In the Post-COVID group, the highest HOMA-IR values were seen in the IGT subgroup, followed by individuals with T1DM and IFG. Notably, T1DM patients also demonstrated marked IR (median 4.94; IQR 3.89). In the COVID-negative group, the T2DM subgroup exhibited the highest HOMA-IR values, with the lowest levels recorded in those with isolated IR and/or hyperinsulinemia. Corresponding subgroup comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences (all p > 0.05).

Table 5.

Estimated type 2tance indices—HOMA-IR and METS-IR in metabolic subgroups from the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD, median (range). Statistical significance is based on Mann–Whitney U test.

Levels of METS-IR were also evaluated across the different metabolic subgroups in both Group 1 (Post-COVID) and Group 2 (COVID-negative) (Table 5). In the Post-COVID group, the highest mean METS-IR values were observed in the T2DM subgroup, followed by individuals with IR and/or hyperinsulinemia. Among participants in the COVID-negative group, the T2DM subgroup also exhibited the highest METS-IR levels, followed by the IGT subgroup. Despite these subgroup-specific trends, no statistically significant differences were found when comparing the corresponding subgroups between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

3.8. Immunological Parameters

3.8.1. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

TNF-α

Serum TNF-α concentrations were higher in the Post-COVID group (Group 1), where mean levels reached 129.09 ± 116.95 pg/mL (median 89.92 pg/mL; IQR 136.37), compared with the COVID-negative group (Group 2), which demonstrated lower levels (86.36 ± 71.60 pg/mL; median 58.67 pg/mL; IQR 106.17). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI using a Gamma GLM (log-link), Post-COVID status remained a strong independent predictor of higher TNF-α levels (B = 4.24; 95% CI: 2.41–6.06; p < 0.001), corresponding to an 8.96-fold increase in TNF-α concentrations (95% CI: 1.74–46.05) relative to COVID-negative individuals.

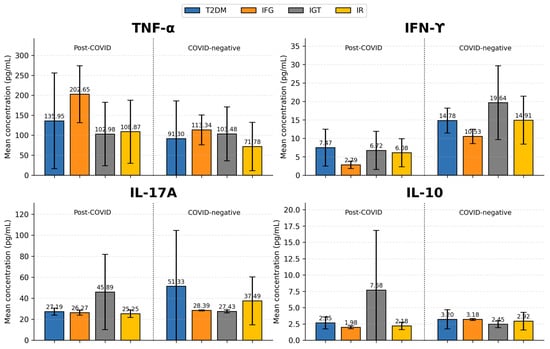

Serum TNF-α concentrations were evaluated across all subgroups in both cohorts. No statistically significant differences were observed when comparing corresponding subgroups between the Post-COVID group (group 1) and the COVID-negative group (group 2) (p > 0.05; Figure 1). The highest mean TNF-α levels were recorded in the IFG subgroup in both groups; however, values were considerably higher in the Post-COVID cohort (202.65 ± 71.25 pg/mL; median 189.87 pg/mL; IQR 43.58) compared with the COVID-negative cohort (113.34 ± 37.55 pg/mL; median 130.12 pg/mL; IQR 34.62). Within group 1, the lowest mean TNF-α levels were observed in the IGT subgroup (102.99 ± 79.50 pg/mL; median 83.34 pg/mL; IQR 77.66), whereas in group 2, the IR subgroup showed the lowest values (71.78 ± 60.39 pg/mL; median 57.14 pg/mL; IQR 90.19). Patients with T2DM from the COVID-negative group exhibited lower TNF-α levels (91.30 ± 94.58 pg/mL; median 51.94 pg/mL; IQR 102.54) compared with their counterparts in the Post-COVID group (135.95 ± 120.00 pg/mL; median 105.50 pg/mL; IQR 140.97), although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparison of cytokine concentrations (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17A, and IL-10) across metabolic subgroups in Post-COVID (Group 1) and COVID-negative (Group 2) individuals. Significant subgroup differences (based on Mann–Whitney U test.) were observed in IFN-γ in T2DM subgroups (p = 0.005), IFG subgroups (p = 0.044), and IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroups (p = 0.003). For IL-17A significant differences were found among T2DM subgroups (p = 0.007) and in the IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroups (p = 0.019) relative to the Post-COVID group. No statistically significant subgroup differences were observed for TNF-α or IL-10; T2DM—Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; IFG—Impaired fasting glycemia; IGT—Impaired glucose tolerance; IR—insulin resistance or/and hyperinsulinemia.

In the T2DM subgroup of Group 1, TNF-α levels showed a strong positive correlation with leptin (rs = 0.715; p = 0.013; 95% CI: 0.202–0.920).

In the IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroup of Group 1, TNF-α levels were also strongly positively correlated with basal insulin (rs = 0.733; p = 0.025; 95% CI: 0.135 to 0.940).

Among individuals with prediabetes (IFG + IGT) in Group 2, TNF-α levels demonstrated a strong positive correlation with uric acid (rs = 0.899; p = 0.037; 95% CI: 0.086 to 0.993) and a negative correlation with triglycerides (TG) (rs= −0.636; p = 0.011; 95% CI: −0.981 to −0.052).

INF-γ

When examining serum IFN-γ levels, patients from the COVID-negative group (Group 2) demonstrated significantly higher concentrations (mean ± SD: 14.90 ± 5.79 pg/mL; median 13.12 pg/mL; IQR 8.60) compared with individuals in the Post-COVID group (Group 1), who showed markedly lower values (mean ± SD: 5.90 ± 4.25 pg/mL; median 4.53 pg/mL; IQR 4.13). This difference was statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 100.5; p < 0.001).

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI using a Gamma GLM (log-link) IFN-γ remained significantly elevated in the Post-COVID group (B = 1.695; 95% CI: 0.29–3.10; p = 0.018), corresponding to an estimated 5.4-fold increase (95% CI: 1.3–22.1).

When examining IFN-γ concentrations across metabolic subgroups, statistically significant differences were observed between the Post-COVID group (Group 1) and the COVID-negative group (Group 2). Significant subgroup differences were identified in the T2DM subgroup (Mann–Whitney U = 14.5, p = 0.004), the IFG subgroup (Mann–Whitney U = 0.0; p = 0.044), and the IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroup (Mann–Whitney U = 14.0; p = 0.003) (Figure 1).

Within Group 2 (COVID-negative), the highest mean IFN-γ levels were recorded in the IGT subgroup (19.64 ± 10.00 pg/mL; median 23.55 pg/mL; IQR 9.41), followed by the IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroup (14.91 ± 6.50 pg/mL; median 13.12 pg/mL; IQR 9.83) and the T2DM subgroup (14.78 ± 3.39 pg/mL; median 13.61 pg/mL; IQR 4.43).

In contrast, patients in Group 1 (Post-COVID) showed markedly lower IFN-γ levels across all subgroups. The highest concentrations were observed among those with T2DM (7.46 ± 4.99 pg/mL; median 5.81 pg/mL; IQR 3.93), followed by the IGT subgroup (6.72 ± 5.17 pg/mL; median 4.53 pg/mL; IQR 4.82) and individuals with IR/hyperinsulinemia (6.08 ± 3.80 pg/mL; median 6.30 pg/mL; IQR 5.95). The lowest IFN-γ levels were found in the IFG subgroup (2.79 ± 1.01 pg/mL; median 3.30 pg/mL; IQR 0.50).

A strong positive correlation was observed between INF-γ and serum TG levels in patients with IR or/and basal hyperinsulinemia from group 1 (rs = 0.779; p = 0.023; 95% CI: 0.163 to 0.958).

Among individuals with T2DM from group 2 INF-γ levels showed a significant positive association with HOMA-IR (rs = 0.683; p = 0.042; 95% CI: 0.035 to 0.927).

IL-17A

Serum IL-17A concentrations were significantly higher in the COVID-negative group (Group 2) compared to the Post-COVID group (Group 1). Individuals in Group 2 demonstrated mean ± SD levels of 40.45 ± 35.01 pg/mL (median 29.04 pg/mL; IQR 7.71), whereas those in Group 1 exhibited 30.26 ± 14.76 pg/mL (median 26.14 pg/mL; IQR 3.86). This difference was statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 281.0; p = 0.001).

To evaluate whether Post-COVID status independently predicted IL-17A concentrations beyond demographic and anthropometric factors, a Gamma GLM with log link adjusted for age, sex, and BMI was performed. In the adjusted model, Post-COVID status remained strongly associated with IL-17A levels (B = 3.59; 95% CI: 2.89–4.29; p < 0.001). On the log scale, this corresponds to an estimated 36-fold increase in IL-17A levels (95% CI: 18–73) in Post-COVID subjects compared with COVID-negative individuals after covariate adjustment.

Levels of IL-17A were further examined across individual subgroups in both the Post-COVID group (group 1) and the COVID-negative group (group 2), and statistically significant differences were observed between several corresponding subgroups (Figure 1). In group 1, the highest mean IL-17A levels were recorded in the IGT subgroup (45.89 ± 35.83 pg/mL; median 27.11 pg/mL; IQR 31.93), which did not significantly differ from the corresponding IGT subgroup in group 2 (27.43 ± 1.47 pg/mL; median 27.11 pg/mL; IQR 1.44). In contrast, within group 2, the T2DM subgroup exhibited the highest IL-17A concentrations (51.33 ± 53.22 pg/mL; median 29.04 pg/mL; IQR 9.14), showing a significant difference from the corresponding T2DM subgroup in group 1 (Mann–Whitney U = 16.5; p = 0.007), where considerably lower levels were recorded (21.19 ± 3.41 pg/mL; median 26.08 pg/mL; IQR 2.44). Among subgroups of group 2, the lowest IL-17A levels were observed in the IGT subgroup (27.43 ± 1.47 pg/mL; median 27.11 pg/mL; IQR 1.45). A significant difference was also detected between the two IR subgroups (Mann–Whitney U = 28.0; p = 0.019), with individuals in group 2 demonstrating higher IL-17A levels (37.49 ± 22.81 pg/mL; median 30.97 pg/mL; IQR 10.12) compared to those in group 1 (25.25 ± 3.64 pg/mL; median 25.17 pg/mL; IQR 4.63).

In the IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroup of the Post-COVID group (Group 1), IL-17A levels showed significant positive correlations with both LDL-C (rs = 0.706; p = 0.034; 95% CI: 0.079 to 0.933) and total cholesterol (rs = 0.818; p = 0.007; 95% CI: 0.336 to 0.960).

Within the T2DM subgroup of group 1, IL-17A levels were strongly and inversely associated with C-peptide concentrations (rs = −0.933; p < 0.001; 95% CI: −0.984 to −0.735).

Among individuals with prediabetes (combined IFG + IGT subgroups) from group 1, IL-17A levels positively correlated with IFN-γ (rs = 0.852; p = 0.015; 95% CI: 0.277 to 0.977).

In the T2DM subgroup of the COVID-negative group (Group 2), IL-17A levels showed a significant negative correlation with adiponectin (rs = −0.912; p = 0.011; 95% CI: −0.990 to −0.387).

3.8.2. Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines

IL-10

Serum IL-10 levels were evaluated across both groups. Individuals in the Post-COVID group (Group 1) demonstrated slightly higher circulating IL-10 concentrations (mean ± SD: 3.45 ± 4.30 pg/mL; median 2.35 pg/mL; IQR 0.89) compared with those in the COVID-negative group (Group 2), who exhibited mean ± SD levels of 2.99 ± 1.26 pg/mL (median 2.81 pg/mL; IQR 0.79). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05).

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI using a Gamma GLM (log-link), Post-COVID status remained a significant predictor of higher IL-10 concentrations (B = 1.93; 95% CI: 0.17–3.69; p < 0.026), corresponding to an estimated 6.9-fold increase in IL-10 levels (95% CI: 1.2–38.3) relative to COVID-negative individuals.

When IL-10 levels were compared between corresponding subgroups (Figure 1, no statistically significant differences were detected (p > 0.05). In Group 1, the highest IL-10 levels were noted in the IGT subgroup (7.67 ± 9.15 pg/mL; median 2.80 pg/mL; IQR 8.12). In Group 2, the highest levels were recorded in the T2DM subgroup (3.20 ± 1.47 pg/mL; median 2.81 pg/mL; IQR 0.79).

Conversely, the lowest IL-10 concentrations were observed in the IFG subgroup of Group 1 (1.98 ± 0.23 pg/mL; median 1.98 pg/mL; IQR 0.31) and in the IGT subgroup of Group 2 (2.45 ± 0.52 pg/mL; median 2.33 pg/mL; IQR 0.51).

In the T2DM subgroup of the Post-COVID group (Group 1), IL-10 levels showed a significant positive correlation with adiponectin (rs = 0.673; p = 0.023; 95% CI: 0.122 to 0.907).

4. Discussion

4.1. General Characteristics

In this study, we evaluated 68 patients with various metabolic disorders (T1DM, T2DM, IFG, IGT, and IR) admitted to our clinic. The cohort was divided into two groups: 35 patients (51.47%) who were newly diagnosed with carbohydrate metabolism disorders 6 months after previous COVID-19, and 33 patients (48.53%) with established metabolic disorders but without any prior history of COVID-19 infection or vaccination.

The mean age of all participants was 46.78 ± 4.74 years, with a statistically significant difference observed between the groups (p < 0.01). Individuals in the COVID-negative group were older (48.21 ± 4.51 years) than those with Post-COVID-onset metabolic disturbances (45.35 ± 4.98 years).

The selection of the COVID-negative control group was designed to closely approximate the age range of the Post-COVID cohort. This was crucial given the well-established relationship between advancing age and the rising incidence of carbohydrate metabolism disorders, particularly T2DM. Recent epidemiological data indicate that the steepest increase in diabetes prevalence occurs among individuals aged 45–64 years, with an even greater burden seen in populations older than 65 years [19]. Ensuring similar age profiles between groups therefore minimized confounding effects related to age-dependent metabolic decline and allowed more accurate comparison of Post-COVID and non-COVID metabolic phenotypes.

Female predominance was noted across the entire sample, with women representing approximately three-quarters of the study population.

A positive family history of diabetes was present in 42.65% of participants, slightly more common in Group 2 (45.45%) than in Group 1 (40%), although not statistically significant.

Approximately half of all participants had diabetes (N = 30; 44.72%). Notably, diabetes was more prevalent in the Post-COVID group (Group 1), where more than half of the patients (N = 19; 54.28%) had diabetes, compared with only one-third of COVID-negative individuals (N = 11; 33.33%). This distribution aligns with emerging evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection may unmask or accelerate metabolic disease processes through mechanisms involving beta-cell dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and immune-metabolic dysregulation [20].

All patients in the Post-COVID group had newly diagnosed carbohydrate disorders, including all cases of diabetes, reflecting the strict inclusion criterion that metabolic disturbances must have been identified within six months following SARS-CoV-2 infection. This design minimizes the likelihood that pre-existing dysglycemia contributed to the observed findings and supports a potential temporal association between COVID-19 and the onset of metabolic abnormalities. In contrast, Group 2 consisted of patients with metabolic disorders unrelated to prior COVID-19 infection or vaccination, among whom only 24 individuals were newly diagnosed—two with diabetes and the remainder with metabolic disturbances comprising the spectrum of MetS. Within this group, 24 participants were newly diagnosed and untreated at the time of evaluation, whereas nine had previously diagnosed T2DM and were receiving non-insulin antidiabetic therapy.

Recent evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2 infection may contribute to the development of T2DM within six months after infection, emphasizing the potential long-term metabolic consequences of COVID-19. Male sex and greater disease severity have been identified as significant risk factors for Post-COVID diabetes incidence [21]. In our Post-COVID cohort, however, the sex distribution among newly diagnosed diabetic patients was balanced, with equal proportions of males and females, suggesting that in our cohort, factors beyond sex may have contributed to the observed metabolic dysregulation.

A comparison of the distribution of metabolic disorders between the two groups demonstrated no substantial imbalance. The relative proportions of individuals with T2DM, IFG, IGT, and IR were comparable between the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups, indicating that both cohorts contained a similar representation of each metabolic phenotype.

4.2. Body Mass Index (BMI)

In the present study, both Post-COVID individuals and COVID-negative patients with MetS exhibited BMI values within the overweight to obese range, reflecting the well-established association between excess adiposity and metabolic dysregulation. Although mean BMI was higher in the COVID-negative group, no statistically significant difference was observed, suggesting that the presence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection did not independently shape overall BMI distribution. Instead, the metabolic phenotype of both cohorts appears to be driven primarily by underlying IR and dysglycemia rather than by body weight alone.

The greater proportion of normal-weight individuals within the Post-COVID group likely reflects the inclusion of newly diagnosed T1DM cases, who typically present without obesity. This aligns with existing literature indicating that new-onset autoimmune or insulin-deficient phenotypes can arise after viral infections, including COVID-19, without concurrent weight gain [22]. Conversely, the predominance of obesity among COVID-negative patients is consistent with classical mechanisms of MetS, in which visceral adiposity and chronic low-grade inflammation serve as major pathogenic drivers.

Subgroup analysis further underscores these mechanistic distinctions. In the Post-COVID group, the highest BMI values were observed in individuals with T2DM and in those with IR and/or hyperinsulinemia, potentially reflecting the combined effects of preexisting susceptibility and post-infectious metabolic perturbation. In contrast, among COVID-negative subjects, the IFG and T2DM subgroups exhibited the greatest degree of obesity, in line with traditional obesity-driven pathogenesis. Meanwhile, IR individuals in this group had comparatively lower BMI, supporting the notion that in classical MetS, the severity of IR does not always correlate directly with BMI.

Taken together, these findings suggest that although BMI was elevated across both groups, the drivers, patterns, and clinical implications of excess body weight differ between Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction and conventional MetS, with the former potentially involving virus-mediated alterations in insulin sensitivity and immunometabolic signaling.

4.3. Lipid Profile Parameters and Uric Acid Levels

In the unadjusted analysis, patients in the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups demonstrated largely comparable lipid profiles, with no significant differences in total cholesterol, TG, HDL-C, or LDL-C. While minor trends were noted within specific subgroups—for example, slightly higher total cholesterol in IFG subgroups or lower LDL-C in certain IGT groups—these variations did not reach statistical significance. This similarity across groups and metabolic subtypes suggests that classic atherogenic dyslipidemia associated with IR—elevated TG and LDL-C with reduced HDL-C—is present regardless of COVID-19 history. The consistently high prevalence of hypertriglyceridemia (TG > 1.7 mmol/L) in nearly all subgroups further supports the shared contribution of underlying metabolic dysfunction.

However, the adjusted regression models revealed a distinct pattern, indicating that SARS-CoV-2 infection may exert additional metabolic effects not captured by simple group comparisons. After controlling for age, sex, and BMI, the Post-COVID group exhibited significantly higher total cholesterol, TG and LDL-C, alongside significantly lower HDL-C. These results raise questions about potential long-term effects of the infection on lipid metabolism and suggest potential post-infectious alterations in hepatic lipid handling, persistent inflammation, and qualitative HDL dysfunction—mechanisms increasingly recognized in Post-acute COVID-19 studies [23].

Although not part of the diagnostic criteria, increased levels of uric acid are associated with increased prevalence of MetS [24] and also with all its components, including high TG, low HDL-C, high blood pressure, obesity, and high plasma glucose [25].

Likewise, uric acid levels were elevated (>420 µmol/L in men and >340 µmol/L in women) in both groups, with no significant differences between subgroups in unadjusted analysis, aligning with its known association with IR and MetS. The most notable finding was the marked elevation in uric acid levels in the Post-COVID group after adjustment, consistent with enhanced oxidative stress and increased purine turnover described in post-viral metabolic injury [26]. This exaggerated uric acid response contrasts with the more moderate elevations typically seen in classical MetS and may reflect a unique component of Post-COVID immunometabolic stress.

Taken together, these findings indicate that while traditional lipid parameters appear similar between groups at the descriptive level, Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction may represent a distinct phenotype once demographic and anthropometric factors are accounted for. The adjusted analyses point toward a pattern of inflammation-driven dyslipidemia, hepatic metabolic dysregulation, and increased oxidative stress, highlighting the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 infection may contribute additional metabolic stressors that warrant further investigation.

These findings suggest that COVID-19 may accelerate or unmask metabolic dysfunction, particularly in susceptible individuals, resulting in lipid and uric acid abnormalities.

4.4. Glycemic Parameters

The significantly higher fasting glucose and HbA1c levels observed in the Post-COVID group, both before and after statistical adjustment, highlight a pronounced glycemic impairment in individuals who developed carbohydrate disturbances following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although unadjusted comparisons already indicated poorer glycemic control in the Post-COVID cohort, the adjusted Gamma GLM analysis revealed an even stronger association, demonstrating that Post-COVID status independently predicts substantially elevated glucose and HbA1c levels, irrespective of age, sex, or BMI. These findings support the hypothesis that COVID-19 induces additional diabetogenic mechanisms beyond classical metabolic risk factors. Proposed pathways include direct beta-cell injury [27], impaired insulin secretion [28], cytokine-induced IR [29,30], and long-term disturbances in adipokine signaling [11]. The magnitude of the adjusted effect suggests that SARS-CoV-2 may amplify underlying metabolic vulnerability, accelerating dysglycemia to a degree not fully explained by traditional determinants such as obesity or age. Together, these results underscore the need for proactive screening and close glycemic monitoring in individuals recovering from COVID-19, even in those without prior metabolic disease.

4.5. Hormonal Parameters

An imbalance between pro-inflammatory adipokines like leptin, which is overproduced, and anti-inflammatory adipokines like adiponectin, which are decreased, is being observed in MetS. This imbalance contributes to the onset and progression of the IR, dyslipidemia, and chronic low-grade inflammation, other key components of the MetS [30,31,32].

Adipose tissue dysfunction has also been reported in the course of COVID-19 with an increase in leptin levels and accompanying leptin resistance as well as dramatic decrease in adiponectin levels [11].

Leptin and adiponectin showed distinct patterns in Post-COVID individuals compared with those with classical MetS. Although unadjusted analyses revealed no significant differences in either marker between groups, adjusted Gamma GLMs demonstrated important differences. Leptin levels tended to be higher in the Post-COVID cohort after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, suggesting a possible shift toward greater adipose tissue inflammatory activity. However, this association did not reach statistical significance, confirming that classical drivers such as obesity and sex likely remain dominant determinants of leptin levels in both populations.

In contrast, adiponectin was markedly elevated in the Post-COVID group after covariate adjustment, despite similar concentrations across groups in raw comparison. This finding may indicate altered regulatory dynamics of adiponectin secretion in the context of post-viral metabolic stress. Elevated adjusted adiponectin could reflect compensatory upregulation in response to heightened inflammation [33], endothelial dysfunction, or oxidative stress [34,35]—phenomena documented in Post-COVID conditions.

Alternatively, the large fold-change suggests that conventional confounders (age, sex, BMI) explain a greater proportion of adiponectin variability in COVID-negative individuals, thereby amplifying the adjusted group effect. Given adiponectin’s anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing properties, higher adjusted levels in the Post-COVID cohort may reflect an adaptive counter-regulatory response rather than a direct reflection of improved metabolic health.

Overall, these findings suggest that adipokine regulation in Post-COVID metabolic disorders may differ fundamentally from that observed in classical MetS, with adiponectin in particular revealing an altered immunometabolic profile that warrants further mechanistic investigation.

4.6. Insulin Resistance Indices

Both the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups demonstrated markedly elevated IR, as indicated by mean HOMA-IR and METS-IR values exceeding the established clinical cut-offs of 2.9 and 31.84, respectively. This finding confirms that IR is a central metabolic abnormality in both newly developed Post-COVID dysglycemia and classical MetS. Individuals in the COVID-negative group exhibited higher average levels of both indices, consistent with the typically longer duration of metabolic disturbances and established mechanisms linking excess adiposity, chronic low-grade inflammation, and impaired insulin signaling in MetS.

Although crude comparisons showed similar HOMA-IR and METS-IR levels between the Post-COVID and COVID-negative groups, the adjusted regression analysis revealed an important underlying difference. After controlling for age, sex, and BMI, both indices were significantly higher among individuals in the Post-COVID group. This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection may exert an additional, BMI-independent effect on insulin sensitivity, consistent with emerging evidence that COVID-19 can trigger persistent impairments in insulin signaling and peripheral glucose uptake through ongoing inflammatory and cytokine-mediated pathways [36,37].

The magnitude of the adjusted effects—particularly the strong elevations in METS-IR—points to a possible post-viral amplification of IR, which is a central driver of dysglycemia [11].

Importantly, these differences were not reflected in the unadjusted subgroup analyses, where corresponding metabolic subgroups showed broadly comparable values of the indices. This distinction highlights the importance of multivariate models for identifying COVID-related metabolic changes that may be obscured by the significant heterogeneity inherent in MetS populations. Notably, subjects with T1DM in the Post-COVID group also demonstrated significant IR based on both measures (HOMA-IR = 4.99 and METS-IR = 52.94) despite having a normal BMI (23.63 kg/m2). This observation likely reflects the poor glycemic control documented in this subgroup (HbA1c 11.11 ± 1.85%), as chronic hyperglycemia itself exacerbates IR through glucotoxic and lipotoxic mechanisms.

Taken together, the findings indicate that COVID-19 may trigger long-lasting immunometabolic perturbations that exceed the degree of IR typically observed in classical MetS, pointing toward a distinct pathogenic mechanism involving inflammation-driven metabolic stress. They also suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to contribute independently to the development or worsening of IR, reinforcing the need for targeted monitoring and early intervention in affected individuals.

4.7. Immunological Parameters–Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines

A comprehensive evaluation of the cytokine profile revealed distinct inflammatory signatures in individuals with newly developed metabolic disturbances following COVID-19 compared with those presenting with classical MetS. These patterns suggest partially overlapping, yet biologically divergent, inflammatory pathways contributing to metabolic dysfunction across the two contexts.

TNF-α, a key mediator of metabolic inflammation, was elevated in both study groups, although mean concentrations were consistently higher among Post-COVID individuals. While this difference did not reach statistical significance in unadjusted analyses, the overall pattern suggests a sustained pro-inflammatory state following SARS-CoV-2 infection, in line with previous reports linking long-COVID to chronic low-grade inflammation and immune dysregulation [38,39].

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, TNF-α demonstrated the strongest independent association with Post-COVID status, with affected patients exhibiting an estimated 69-fold increase in circulating levels. This substantial effect size reinforces the hypothesis that TNF-α–driven inflammation persists long after recovery from acute infection. Such prolonged cytokine activity is biologically plausible, given TNF-α’s central role in adipose-tissue inflammation, beta-cell stress, and IR, all of which contribute to metabolic impairment and may be amplified by virus-induced immune alterations [40]. Collectively, these findings support the concept that SARS-CoV-2 may imprint a long-lasting inflammatory signature that interacts with—or exacerbates—classical metabolic pathways.

Notably, the IFG subgroups in both groups exhibited the highest TNF-α values, pointing to a possible early pathogenic phase during which TNF-α contributes to beta-cell dysfunction and impaired insulin secretion, as previously described in metabolic inflammation [41].

In the Post-COVID T2DM subgroup, TNF-α levels showed a strong positive association with leptin reflecting the well-established role of leptin as a pro-inflammatory adipokine that amplifies TNF-α expression through macrophage activation [42]. The observed correlation also supports the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 triggers long-lasting adipose-tissue inflammation, thereby promoting cytokine–adipokine crosstalk even after viral clearance [43]. Elevated leptin has been linked to impaired glucose uptake and beta-cell stress, potentially contributing to post-infectious deterioration of glycemic control.

A similarly strong correlation between TNF-α and basal insulin observed in the IR/hyperinsulinemia subgroup of the Post-COVID cohort suggests that low-grade inflammation may be actively contributing to compensatory hyperinsulinemia. TNF-α is known to impair insulin-receptor signaling and disrupt downstream metabolic pathways [44] which may explain the relationship observed. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 infection may accelerate the transition from IR to overt dysglycemia through cytokine-dependent alterations in insulin sensitivity. In this context, TNF-α appears to function as a key mediator linking post-infectious inflammation with emerging metabolic dysfunction, reinforcing its pathogenic relevance in both classical MetS and Post-COVID metabolic disturbances.

In COVID-negative individuals with prediabetes (IFG and IGT), TNF-α showed a strong positive correlation with serum uric acid, a biomarker closely linked to oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and heightened cardiometabolic risk. Prior evidence indicates that uric acid itself can stimulate the production of TNF-α, thereby establishing a bidirectional amplification loop between purine metabolism and inflammatory signaling [45]. This reciprocal relationship suggests that, even in the absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, prediabetes may be characterized by a synergistic interplay between oxidative stress, impaired purine metabolism, and immune activation. Such an interaction may contribute to the progression of metabolic dysfunction in susceptible individuals and emphasizes the importance of considering both metabolic and inflammatory pathways when evaluating early dysglycemia.

Interestingly, within the same group, TNF-α demonstrated a negative correlation with TG levels, suggesting the presence of altered lipid metabolism in individuals undergoing early metabolic deterioration. Such inverse associations may reflect an adaptive or compensatory response during the transition from IR to overt dysglycemia, where circulating TG levels decrease despite heightened inflammatory signaling. Similar dissociations between inflammation and TG levels have been described in conditions characterized by disrupted lipid storage and enhanced lipolytic flux, supporting the possibility of an early maladaptive phase of metabolic dysregulation in which TNF-α–driven inflammation coexists with modified TG handling [46,47,48]. This metabolic–inflammatory interaction warrants further investigation to determine whether it represents a transient compensatory phenomenon or an early marker of progression toward more advanced metabolic impairment.

In contrast to TNF-α, IFN-γ demonstrated a distinct and divergent pattern, with significantly higher circulating levels in the COVID-negative group compared with Post-COVID individuals, both in the overall comparison and within key metabolic subgroups (T2DM, IFG, and IR/hyperinsulinemia). This distribution aligns with the well-established role of IFN-γ in classical obesity-driven IR, macrophage M1 polarization, and adipose-tissue inflammation, mechanisms that characterize long-standing MetS [49,50] rather than newly emerging post-viral disturbances. The consistently higher IFN-γ concentrations in COVID-negative individuals with T2DM, IFG, and IR suggest that IFN-γ more strongly reflects chronic metabolic inflammation than post-infectious immune alterations.

Conversely, the markedly lower IFN-γ levels in the Post-COVID cohort may reflect impaired or dysregulated interferon signaling, a phenomenon reported during and following SARS-CoV-2 infection, where defective IFN-γ-mediated responses persist beyond the acute phase and contribute to immune exhaustion. This interpretation is supported by prior evidence of blunted interferon activity in patients recovering from COVID-19, even months after infection [51].

However, after statistical adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, Post-COVID status became independently associated with higher IFN-γ levels, corresponding to a 5.4-fold increase. This suggests that, although absolute IFN-γ concentrations are lower in Post-COVID individuals, residual IFN-γ dysregulation remains detectable once demographic and anthropometric factors are accounted for. Given that IFN-γ promotes macrophage M1 activation and disrupts insulin-signaling pathways, these adjusted findings raise the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 leaves behind a persistent type-1 inflammatory imprint that may contribute to ongoing metabolic disturbances.

Taken together, IFN-γ appears to differentiate classic MetS from Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction. In COVID-negative MetS, IFN-γ reflects chronic obesity-related immune activation whereas in Post-COVID metabolism, lower absolute IFN-γ levels combined with significant adjusted elevations point to virus-induced immune recalibration rather than adiposity-driven inflammation. This dual pattern underscores the complex interplay between chronic metabolic inflammation and post-viral immunological remodeling, highlighting IFN-γ as a cytokine with potential diagnostic and mechanistic relevance in distinguishing metabolic phenotypes.

In the Post-COVID IR subgroup, IFN-γ demonstrated a strong positive correlation with TG levels, suggesting IFN-γ–mediated stimulation of hepatic VLDL production—a mechanism previously described in inflammatory metabolic stress [52,53].

This association further implies that the immune–metabolic axis remains activated long after SARS-CoV-2 clearance, consistent with emerging evidence of prolonged cytokine dysregulation in Post-acute COVID-19 syndromes [54]. The IFN-γ–TG relationship observed here supports the hypothesis that Post-COVID metabolic disturbances may be driven, at least in part, by persistent cytokine-mediated interference with lipid handling, aligning with reports of post-viral inflammatory dyslipidemia [55].

In contrast, among COVID-negative individuals with T2DM, IFN-γ correlated positively with HOMA-IR, reflecting a more classical relationship where IFN-γ contributes to systemic IR. Together, these findings imply that Post-COVID IFN-γ–lipid axis activation may differ mechanistically from IFN-γ–driven IR in traditional MetS.

IL-17A, another pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with adipose tissue inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and T2DM progression [56], demonstrated a similar trend to IFN-γ. Overall, IL-17A levels were higher in the COVID-negative group, with significant differences in the T2DM (p = 0.007) and IR (p = 0.019) subgroups.

These results suggest that IL-17A may also be more closely linked to classic obesity-driven immune activation. The exception occurred in the IFG subgroup, where IL-17A levels in the Post-COVID cohort were slightly higher, though not statistically significant. This could reflect early immune perturbations following SARS-CoV-2 infection, where IL-17A–mediated pathways may be activated in early dysglycemia [57].

Together, these trends reinforce the concept that IL-17A behaves similarly to IFN-γ, contributing mainly to chronic metabolic inflammation rather than Post-COVID metabolic derangements.

After adjustment IL-17A remained strongly associated with Post-COVID status, with an estimated 36-fold increase (95% CI: 18–73). This magnitude far exceeds what is typically observed in classic MetS and suggests that Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction may involve a more intense or persistent Th17-directed inflammatory response. Such sustained IL-17A activity has been linked to endothelial activation, altered adipokine secretion, and immune remodeling, mechanisms that could plausibly contribute to the metabolic phenotype seen in Post-COVID patients. Taken together, these results indicate that while IL-17A participates in chronic metabolic inflammation in classical MetS, its exaggerated elevation in Post-COVID individuals may reflect a distinct, virus-induced immunometabolic perturbation.

Taken together, these findings imply that IL-17A contributes to both chronic MetS-related inflammation and post-viral immune remodeling. In COVID-negative individuals, IL-17A appears to reflect classic obesity-driven immune activation, whereas in Post-COVID subjects it may indicate persistent Th17-axis activation and immune perturbation following SARS-CoV-2 infection, potentially contributing to the metabolic phenotype observed in this cohort.

IL-17A demonstrated distinct and subgroup-specific associations that further differentiate Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction from classical MetS. In the Post-COVID cohort, IL-17A correlated positively with LDL-C and total cholesterol within the IR subgroup, suggesting a role in post-viral dyslipidemia and adipose-tissue immune activation—patterns consistent with Th17-mediated lipid disturbances described previously [58]. In the Post-COVID T2DM subgroup, IL-17A showed a strong inverse correlation with C-peptide, indicating a potential involvement in beta-cell secretory impairment. Additionally, the positive IL-17A–IFN-γ correlation observed in the prediabetes (IFG + IGT) subgroup supports the presence of a coordinated pro-inflammatory Th1/Th17 signature during early Post-COVID metabolic deterioration.

In contrast, IL-17A levels were generally lower across several subgroups in the COVID-negative cohort, and in T2DM subgroup it correlated negatively with adiponectin—consistent with the well-established antagonism between Th17 signaling and adiponectin-mediated insulin sensitization [59].

Taken together, these findings indicate that IL-17A plays divergent roles in classical versus Post-COVID metabolic disease. In traditional MetS, IL-17A primarily reflects chronic obesity-related inflammation, whereas in Post-COVID metabolism it appears more tightly linked to lipid abnormalities, beta-cell dysfunction, and persistent immune activation, underscoring its relevance as a mediator of post-viral immunometabolic remodeling.

IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine with known immunometabolic protective functions, showed only modest differences between groups in the unadjusted analysis, with slightly higher circulating levels observed in the Post-COVID cohort. Although these differences were not statistically significant, the directionality may reflect partial immune rebalancing following SARS-CoV-2 infection. In classical MetS, reduced IL-10 activity and impaired IL-10 receptor signaling are well-documented contributors to sustained low-grade inflammation, suggesting that diminished IL-10 bioactivity is a common feature of metabolic dysregulation [60].

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, Post-COVID status emerged as a significant independent predictor of IL-10 elevation, with a nearly sevenfold increase compared with COVID-negative individuals. This adjusted effect implies that SARS-CoV-2 may induce a compensatory upregulation of IL-10 in the post-infection period, potentially as a counteraction against persistent pro-inflammatory state in this cohort. The lack of significant subgroup differences further supports the notion that IL-10 responses are globally modulated rather than phenotype-specific.

Notably, in the T2DM subgroup of the Post-COVID cohort, IL-10 correlated strongly and positively with adiponectin, highlighting a coordinated anti-inflammatory response not observed in the COVID-negative group. Given that both IL-10 and adiponectin are key inhibitors of Th1/Th17-mediated inflammation and facilitators of insulin sensitivity [61,62], this relationship may indicate a partial preservation—or activation—of compensatory immunometabolic pathways in Post-COVID diabetes. Together, these findings suggest that while IL-10 suppression is characteristic of classical MetS, Post-COVID individuals may exhibit a distinct IL-10 regulation pattern, shaped by the lingering immunological imprint of SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than metabolic status alone.

In summary this cytokine signature suggests that while Post-COVID metabolic disorders share some inflammatory features with classical MetS, they exhibit a distinct and more intense immunometabolic phenotype, likely shaped by persistent immune activation and the lingering immunological imprint of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Altogether, these results highlight the need for longitudinal studies to elucidate the trajectory, determinants, and clinical relevance of Post-COVID immunometabolic disturbances, and to clarify whether these alterations represent temporary post-infectious adaptations or a novel pathway toward sustained metabolic disease.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrate that individuals who develop metabolic disturbances following SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibit a distinct immunometabolic profile compared with COVID-negative patients with classical MetS. Despite broadly similar BMI ranges and comparable unadjusted lipid and uric acid values, adjusted analyses revealed a pattern of inflammation-driven dyslipidemia, marked oxidative stress, and significantly impaired glycemic control in the Post-COVID cohort. Post-COVID status independently predicted higher glucose, HbA1c, LDL-C, total cholesterol, TG, uric acid, and IR indices, indicating that SARS-CoV-2 may exert additional metabolic stress beyond traditional risk factors.

A prominent finding was the profound cytokine dysregulation in the Post-COVID cohort, with pronounced elevations in TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-17A, and IL-10 after adjustment. These cytokine patterns differed qualitatively from those observed in classical MetS, where chronic obesity-driven inflammation predominates. The strong associations between cytokines and metabolic indices—including IL-17A with lipids and C-peptide, IFN-γ with TG, and TNF-α with insulin—further support a model in which Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction emerges from sustained immune activation, altered adipokine signaling, and impaired insulin action.

Taken together, our findings indicate that Post-COVID metabolic disturbances are not merely accelerated forms of classical MetS but may represent a distinct post-viral immunometabolic phenotype shaped by the lasting biological effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. These results highlight the importance of systematic metabolic monitoring after COVID-19, even in individuals without prior metabolic disease.

Future longitudinal research should focus on longitudinal characterization of these metabolic and immunological alterations, identification of mechanistic pathways driving Post-COVID metabolic dysfunction, and evaluation of targeted therapeutic strategies to mitigate long-term cardiometabolic risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.T. and K.T. methodology, V.T., M.T., K.T., M.A. and I.G.; software, V.T., M.T. and K.T.; validation, M.A. and I.G.; formal analysis, V.T., M.T., M.A. and I.G.; investigation, V.T., M.T. and K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.T.; writing—review and editing, V.T. and K.T.; supervision, K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was conducted with a grant from the Medical University–Pleven—Project №D6/2023–“Changes in pancreatic beta cell function in COVID-19”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical University Pleven (Protocol №72/23.06.23, 23 June 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants declared their voluntary willingness to participate in the study and gave their consent for the publication of their de-identified clinical data by signing and dating the consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Mircho Vukov for the statistical analysis. The authors acknowledge Medical University—Pleven, Bulgaria for financial support. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IL-17A | interleukin-17A |

| TNF-α | tumor-necrosis factor–alpha |

| INF-γ | interferon-gamma |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes mellitus |

| IFG | Impaired fasting glycemia |

| IGT | Impaired glucose tolerance |

| MetS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance |

| METS-IR | Metabolic Score for Insulin Resistance |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

References

- Alberti, K.G.; Zimmet, P.; Shaw, J.; IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome—A new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005, 366, 1059–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olijhoek, J.K.; van der Graaf, Y.; Banga, J.D.; Algra, A.; Rabelink, T.J.; Visseren, F.L. The insulin resisrome is associated with advanced vascular damage in patients with coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease or abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. Heart J. 2004, 25, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C.; et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Patial, R.; Batta, I.; Thakur, M.; Sobti, R.C.; Agrawal, D.K. Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment Strategies in the Prevention and Management of Metabolic Syndrome. Arch. Intern. Med. Res. 2024, 7, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paragh, G.; Seres, I.; Harangi, M.; Fülöp, P. Dynamic interplay between metabolic syndrome and immunity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 824, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbudi, A.; Khairani, S.; Tjahjadi, A.I. Interplay Between Insulin Resistance and Immune Dysregulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Implications for Therapeutic Interventions. Immunotargets Ther. 2025, 14, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylutka, A.; Walas, Ł.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Level of IL-6, TNF, and IL-1β and age-related diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1330386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]