Abstract

Hyphal systems have been essential for the morphoanatomical characterization of basidiomes and mycelia of aphyllophoroid fungi for taxonomic purposes. They have also been shown to influence the consistency of basidiomes. Recent developments in areas such as mycelium composite production as sustainable materials have redirected scientists’ attention to these structures, particularly regarding their material resistance, where complex hyphal systems enhance the properties of these composites. Compounds such as farnesol and octenol trigger growth and differentiation processes in many fungal groups, and laccases have been proposed as enzymes involved in these processes, given their roles in the synthesis of cell wall pigments and other cell wall components. Given the easily quantifiable differences in hyphal knots and dimitic mycelium between Fuscoporia torulosa and Inocutis tamaricis, we employed them as models to study their responses to these compounds, thereby helping fill the knowledge gap in the modulation of macrofungal mycelial differentiation. A variable effect was observed on laccase induction, while radial growth was reduced by octenol by up to 83% in F. torulosa and 65% in I. tamaricis, and by farnesol by up to 80% in I. tamaricis, showing slight effects on F. torulosa. Reductions of up to 100% were observed in the combination of high doses of both chemicals.

1. Introduction

The mechanical properties of fungal sporocarps, such as rigidity and compressive strength, are strongly influenced by the composition and organization of their hyphal systems. According to Porter & Naleway [1], dimitic and trimitic configurations increase mechanical performance by adding skeletal and binding hyphae, achieving superior resistance to penetration compared to expanded polystyrene and approaching that of some wood species [2]. These elements contribute to structural reinforcement and stress distribution, leveraging mesostructural designs like microtubular arrangements [3]. Such findings highlight the potential of fungal sporocarps as models for bioinspired materials, offering insights into sustainable and efficient design solutions and interesting mechanical properties. Studies report a tensile modulus in the 4–28 MPa range for mycelium matrices of commonly employed species such as Pleurotus ostreatus and Ganoderma lucidum [4], and compressive strength with an average value of 350–570 kPa in Irpex lacteus [5].

Recent developments in areas such as bioaglomerate production as sustainable materials have redirected scientists’ attention to these structures and to possible ways of modulating their consistency. In this context, the study of fungal mycelium has emerged as a promising field, as this unique biomaterial, characterized by its porous, filamentous network and non-linear mechanical behavior, offers an attractive platform for developing bioinspired materials with tunable properties [6]. Moreover, research on pure-mycelium materials has demonstrated that optimizing fermentation strategies and growth conditions enables modulation of their texture and mechanical performance, paving the way for sustainable alternatives across various applications [7].

Macromycetes are complex organisms that produce macroscopic fruiting bodies. The development of these structures requires differentiation, growth, pigmentation, and expansion. These morphogenetic processes involve physiological, biochemical, and morphological changes, including enzyme activities modulated for intracellular and intercellular processes. In addition, it was proposed that the formation of fruiting bodies may be associated with the laccase-catalyzed synthesis of extracellular pigments [8]. Mushrooms like Lentinula species change their pigmentation, forming well-differentiated morphological structures: vegetative non-pigmented mycelium, brown mycelial mat, primordia, and fruiting bodies [9]. These changes include the accumulation of pigments and the development of diverse, organized ranks of hyphae [10]. The choice of the species employed as models in this work results from the abundant data and description of the cultures of our collection, and the particularity of Fuscoporia torulosa and Inocutis tamaricis, in which the differentiation progress is evident in the micro and macroscopic observations, as well as easily quantifiable in terms of dimitic areas or number of knots, respectively, thus allowing statistical treatment of the observed responses.

Besides the aforementioned advantages of these species as models, due to the straightforward observation and quantification of hyphal differentiation, Fuscoporia torulosa has been reported to produce interesting compounds, such as bioactive triterpenes and phenolic compounds [11], and Inocutis tamaricis is known to produce bioactive flavonoids [12] and exopolysaccharides [13]. This is relevant in this framework, since textures associated with complex hyphal systems are also applicable to food preparations.

The regulation and dynamics of morphogenetic processes in fungi are a growing field of research. Many molecules have been reported to be active in triggering or signaling differentiation pathways, as is the case of 1-octen-3-ol (henceforth octenol) and (2E,6E)-3,7,11-trimethyldodeca-2,6,10-trien-1-ol (henceforth farnesol), involved in yeast/mycelium transitions [14] and also in mating and conidiation [15].

Several studies have highlighted the regulatory role of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in fungal morphogenesis, particularly during primordium initiation and fruiting body development. Compounds such as octenol and ethanol have been shown to induce fruiting body formation in Agaricus bisporus and Coprinus cinerea [16,17]. Likewise, farnesol (C15H26O) functions as a quorum-sensing molecule that modulates fungal dimorphism by inhibiting the yeast-to-hypha transition in Candida albicans through transcriptional repression of hypha-specific genes and the upregulation of negative regulators [18]. In Schizophyllum commune, a related mechanism involves schizostatin, a structural analog of farnesol [19] that inhibits squalene synthase, suggesting that autoinhibitory control of dikaryotic mycelial growth may arise from shared isoprenoid-derived intermediates [20].

Octenol has been proven to be a critical regulator in fungal morphogenesis [16,17]. This compound modulates differentiation processes, including hyphal elongation and the initiation of fruiting body formation. It acts as a signaling molecule, responding to environmental cues and orchestrating developmental pathways that optimize fungal adaptation and reproduction [21]. Farnesol has also been shown to trigger differentiation responses [22], such as the induction of a morphological transition to hyperbranched mycelial structures with short hyphae and bulbous tips in Trametes (Coriolus) versicolor, an effect mediated by synergistic modulation of morphogenesis-related genes. Furthermore, the addition of farnesol significantly elevates intracellular oxidative stress, thereby stimulating extracellular laccase production by expanding the number of active secretion sites [23]. These findings underscore farnesol’s dual role in altering mycelial morphology and enhancing enzyme secretion.

Besides their role in fungal cellular differentiation, these compounds are active in diverse organisms. In particular, farnesol has been shown to influence endocrine regulation in bees [24], and octenol acts as an attractant and behavior-modifying molecule in mosquitoes [25], suggesting that they might be involved in widespread mechanisms of cell communication across different living organisms.

Phenoloxidase (e.g., laccase) activity is closely linked to mycelial differentiation patterns and fungal morphogenesis. Enzymes such as laccases, tyrosinases, glucanases, and chitinases display dynamic activity levels that vary across different morphogenetic stages. This variability suggests that they have multiple functions in fungal development [26]. Enhanced phenoloxidase activity, along with increased pigmentation, is often associated with rapid fungal cell growth, primordia formation, and subsequent fruiting body development in both basidiomycetes [27,28,29] and ascomycetes [8,30,31]. According to Baldrian [32], laccase participates in morphogenesis mainly through its effects on the cell wall and spore wall, contributing to the formation of melanins and other structural polymers and, consequently, to hyphal differentiation and the ontogeny of reproductive structures. Its crucial role in hyphal differentiation and fruiting body formation via the oxidation of a wide range of phenolic and aromatic compounds has been known for decades (e.g., Leatham & Stahmann [8]). Its activity has been reported as essential for mycelial differentiation in species such as Hypholoma fasciculare [9]. Also, mutants of Pleurotus florida lacking laccase activity are unable to form fruiting bodies, underscoring the enzyme’s essential role in developmental processes [33].

This study analyzes the effects of farnesol and octenol on mycelial growth and laccase production in two species of agaricomycetes and their impact on hyphal differentiation. This characterization could lay the groundwork for a better understanding of the factors influencing the growth and development of texture-affecting structures.

2. Materials and Methods

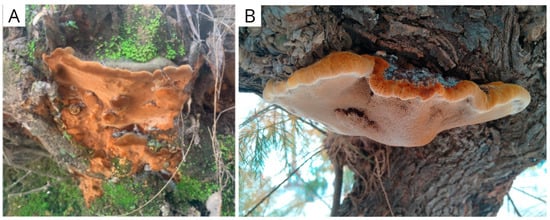

Strains and cultures: The strains were isolated from basidiomes collected for this work. Fuscoporia torulosa (IS0026, GenBank accession number PV688035) was collected in Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park, Spain, on 8 May 2022 (N 36°47′4.56″; W 5°23′56.119″) and Inocutis tamaricis (IS0034, GenBank accession number PV688037) in Gorliz’s pine forest, Spain, on 7 August 2022 (N 43°24′56.696″; W 2°56′30.361″), respectively (Figure 1). The identities of the basidiomes were verified following Chen et al. [34] (for F. torulosa) and Ghobad-Nejhad & Kotiranta [35] (for I. tamaricis). DNA extraction and amplification were performed as described by Kuhar et al. [36], and the resulting products were sequenced with the same primers at Macrogen (Seoul, Republic of Korea). The resulting sequences were compared with available GenBank sequences from verified vouchers. Stock cultures were maintained on malt agar slants at 4 °C, subcultured periodically, and stored at the Innomy Strain Collection (Derio, Basque Country, Spain).

Figure 1.

Fruiting bodies of (A) Fuscoporia torulosa and (B) Inocutis tamaricis, observed in natural conditions (original photography).

Experimental design: To evaluate the effect of farnesol and octenol on fungal colony growth rate, a full factorial experimental design was established using five concentrations of farnesol (0, 35, 70, 105, and 140 µM) and octenol (0, 3, 6, 9, and 12 µL), resulting in all possible combinations. Fungal strains were cultured on malt extract agar (MEA) and inoculated at the center of each Petri dish with a 0.5 mm diameter agar plug taken from the margin of an actively growing colony. Farnesol was incorporated into the medium prior to agar solidification using a concentrated mother solution in ethanol to ensure sterility. Aliquots of ethanol without farnesol were added to the controls to discard the effect of the solvent, whereas octenol was applied to a sterile paper disc attached to the inner surface of the Petri dish lid after inoculation. Plates were incubated for 16 days at 28 °C and 80% relative humidity. Radial mycelial growth was measured using a ruler. Each factor combination was evaluated once, since the assay’s support is provided by the coefficient of determination (R2), not by the individual mediae. The experiment was conducted as a single run.

Biomass production, laccase activity, and hyphal differentiation were assessed using a 22 factorial experimental design (Table 1), with farnesol (CAS No. 4602-84-0) and octenol (CAS No. 3391-86-4) as experimental factors. Both compounds were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Three independent factorial assays were conducted in parallel, each consisting of three replicates in a single experimental run.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions used to evaluate the effect of morphogens on mycelium growth, laccase activity, dry weight, and hyphal differentiation.

Farnesol and octenol concentrations were chosen as the independent variables. The concentration range for both compounds was fixed based on previous evidence of mycelial growth in several fungal species. The concentration ranges used in this study were estimated from relevant articles, taking into account the inhibitory effects on growth or the doses that elicited observable physiological responses reported in these studies for farnesol [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] and taking into account the estimated concentrations in the gas phase for octenol following Singh et al. [38]. Table 2 shows the concentrations in the agarized and liquid media, as well as in the headspace of the Petri dishes and the Erlenmeyer flasks, estimated using the partition coefficients at the culture conditions (Henry’s Law constants) for aqueous media, as explained in Wu et al. 2022 [39].

Table 2.

Estimated final concentration of octenol in gas and aqueous phases, both in Petri dishes and Erlenmeyer flasks, based on the partition coefficients of Henry’s law at the present conditions of the assays.

Effect on laccase activity and biomass production: Fungal strains of both species were grown in 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 30 mL of liquid malt extract medium under static conditions, since both strains had previously been assayed under agitation and neither hyphal differentiation nor laccase activity had been detected. After 18 days, farnesol (Table 1) was added to the medium, and octenol (Table 1) was added to a piece of paper attached to the flask lid.

After 11 and 21 days of exposition, laccase activity was quantified using 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (DMP) as the substrate [40]. We measured the absorbance of the product (λ = 469 nm) using a spectrophotometer and calculated the enzymatic activity using the molar extinction coefficient (ε = 49.6/mM cm) as follows:

Biomass was collected after 21 days of exposition and dried overnight at 65 °C. The biomass produced was determined as the dry weight of each sample.

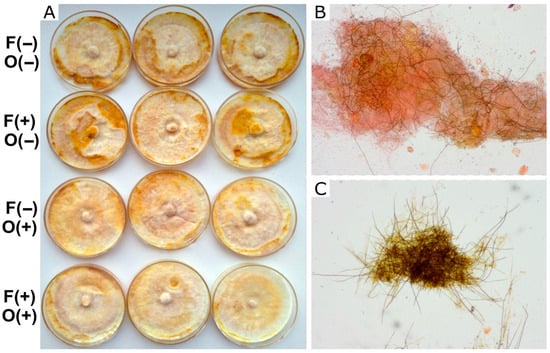

Effect on hyphal differentiation: Fungal strains were cultured on malt extract agar (MEA) containing glucose (10 g/L), malt extract (12.4 g/L), agar (20 g/L), and distilled water. Farnesol was added to the medium MEA before the agar solidified. After 18 days, once the mycelium had fully colonized the agar surface, octenol was placed on a piece of paper attached to the lid of the Petri dish because of its volatility. The plates were monitored for any macroscopical changes in the mat that could indicate hyphal differentiation. Fuscoporia torulosa exhibited melanized brown areas (Figure 2), and I. tamaricis showed melanized hyphal knots (Figure 3), both of which were used as indicators of hyphal differentiation. After 44 days, photographs of each plate were taken, and the percentage of melanized areas in F. torulosa and the number of knots in I. tamaricis were measured using ImageJ v. 1.54m. The images captured from the Petri dishes were transformed into an 8-bit greyscale palette. An analysis of the color intensity distribution, performed in ImageJ, revealed a bimodal distribution. This enabled the identification of a valley, which was subsequently used as a threshold for the automated delimitation and quantification of the melanized area. Additionally, hyphal knots were counted using the Multi-point tool implemented in this software. Melanized areas and hyphal knots were further inspected under a microscope (Estativo Eclipse Si—Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) to analyze their hyphal composition and compare them with the other (non-melanized) areas of the mat.

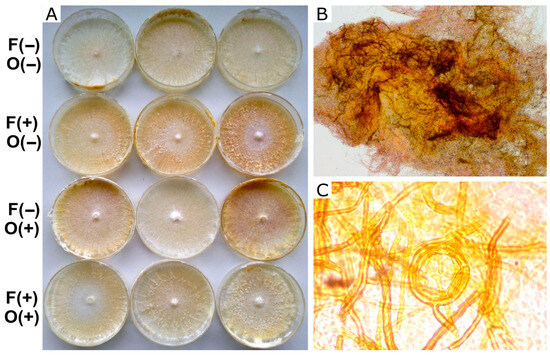

Figure 2.

Growth of F. torulosa in MEA. (A) Macroscopic view of the colony under different treatments. (B,C) Microscopic view (100×) of the clear, undifferentiated zones and the melanized areas, respectively, showing different proportions of skeletal dark hyphae. Symbols on the left indicate the presence (+) or absence (−) of farnesol (F) and octenol (O).

Figure 3.

Growth and differentiation of I. tamaricis in MEA. (A) Macroscopic point of view of mycelium growth over different treatments. (B) Microscopic 100× detail of the knot. (C) 1000× view of skeletal hyphae observed in the knots and a coiled hyphal aggregate. Symbols on the left indicate the presence (+) or absence (−) of farnesol (F) and octenol (O).

Statistical analysis: All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.2; R Core Team). The packages lme4, nlme, car, ggplot2, and rsm were used for mixed-effects modeling, diagnostic tests, data visualization, and response surface analysis, respectively. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test [41]. Homoscedasticity was evaluated using Levene’s test and by visual inspection of residuals versus fitted values plots [42].

When the assumption of homoscedasticity was violated, variance structures were modeled using alternative candidate models. Model selection was based on Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), with only models that met the homoscedasticity assumption included. In the absence of significant interaction, main effects were analyzed independently. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

To determine if mycelium growth of F. torulosa and I. tamaricis is influenced by these substances, two multivariate regression analyses were performed [43,44], assuming a Normal error distribution. In both models, the response variable was radial colony growth (cm) in the Petri dish, while farnesol (µM) and octenol (µL) concentrations were used as explanatory variables.

The effect of morphogens on the growth of both strains in a liquid medium was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. The response variable was defined as the dry weight (g) obtained at the end of the experiment, while the explanatory variables were the exposures to each compound. For I. tamaricis, the final selected model included an exponential variance structure (VarExp). In addition, we analyzed the effect of morphogen exposure on laccase enzyme activity in both strains at 11 and 21 days. A total of four two-way ANOVAs were performed to assess these responses. The response variable was enzyme activity (mIU), while the explanatory variables were exposure to each compound. For F. torulosa, the final selected model included a power variance structure (VarPower).

Finally, to analyze the effects of farnesol and octenol on mycelial differentiation in both strains, a two-way ANOVA was conducted with the presence of each compound as a fixed explanatory factor. Response variables were defined as melanized brown area (%) and knot number, for F. torulosa and I. tamaricis, respectively, using a VarPower variance structure for I. tamaricis.

All ANOVAs revealed no significant interaction between farnesol and octenol. In the absence of such interactive effects, the main effects were analyzed independently, as shown in Figure 4.

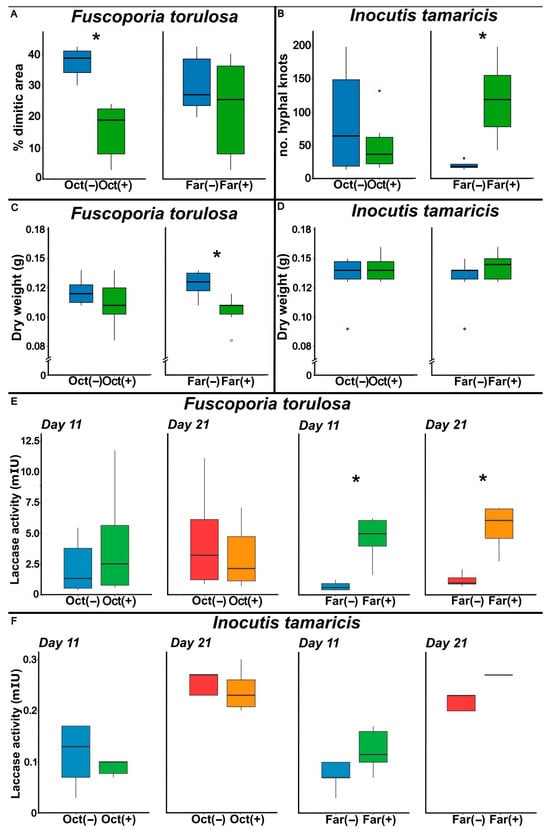

Figure 4.

Box plots showing the effects of farnesol (Far) and octenol (Oct) treatments, comparing untreated (−) and treated (+) conditions, on different physiological parameters in Fuscoporia torulosa and Inocutis tamaricis in liquid culture under static conditions. (A,B) display hyphal differentiation, expressed as percentage of dimitic area for F. torulosa and as number of hyphal knots for I. tamaricis. (C,D) show biomass production obtained expressed as dry weight (g). (E,F) present laccase activity (mIU), measured on days 11 (blue and green) and 21 (red and orange) of cultivation under each treatment. Box plots indicate the median, interquartile range, and extreme values; asterisks denote statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Effect on Colony Growth Rate

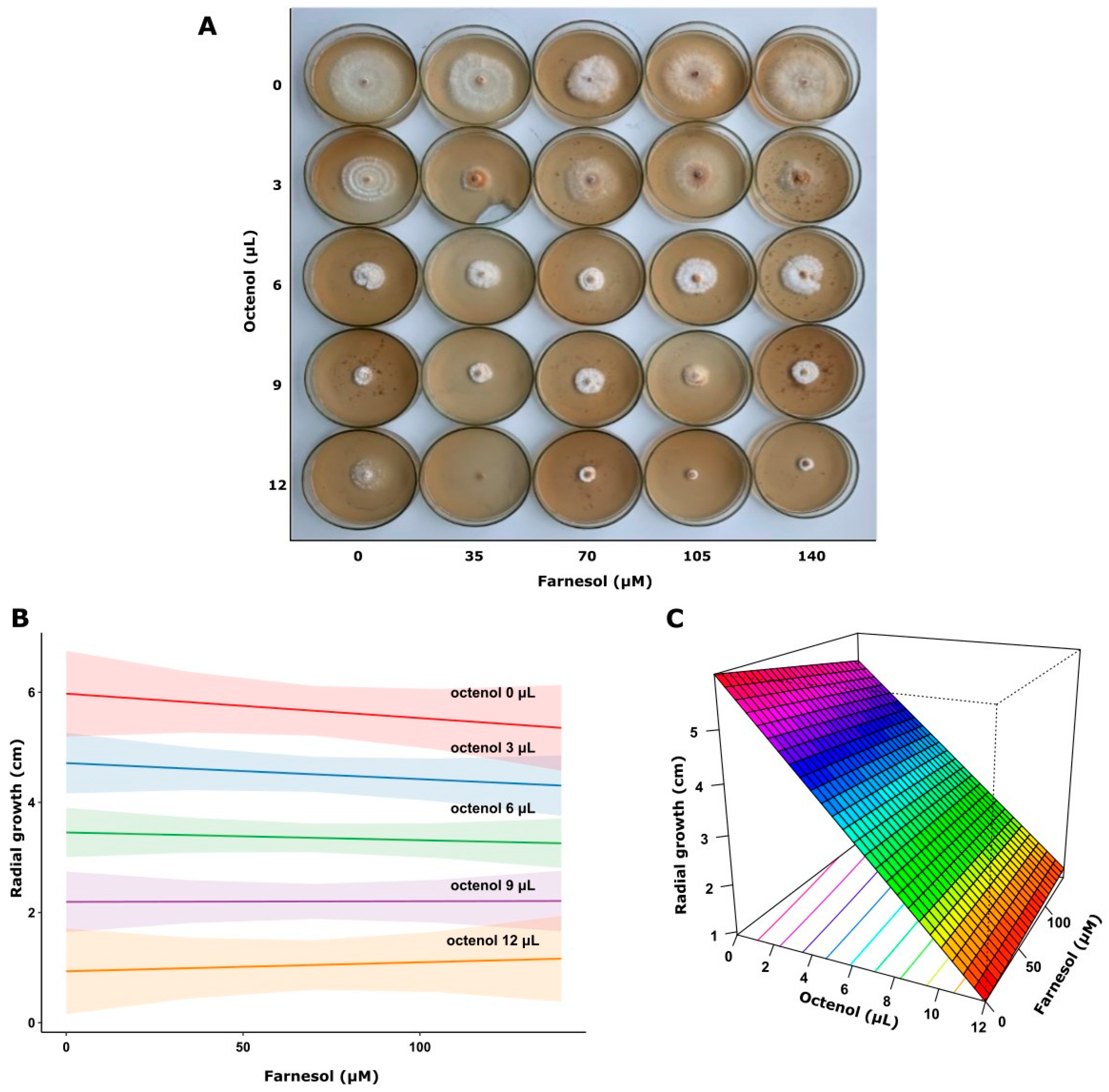

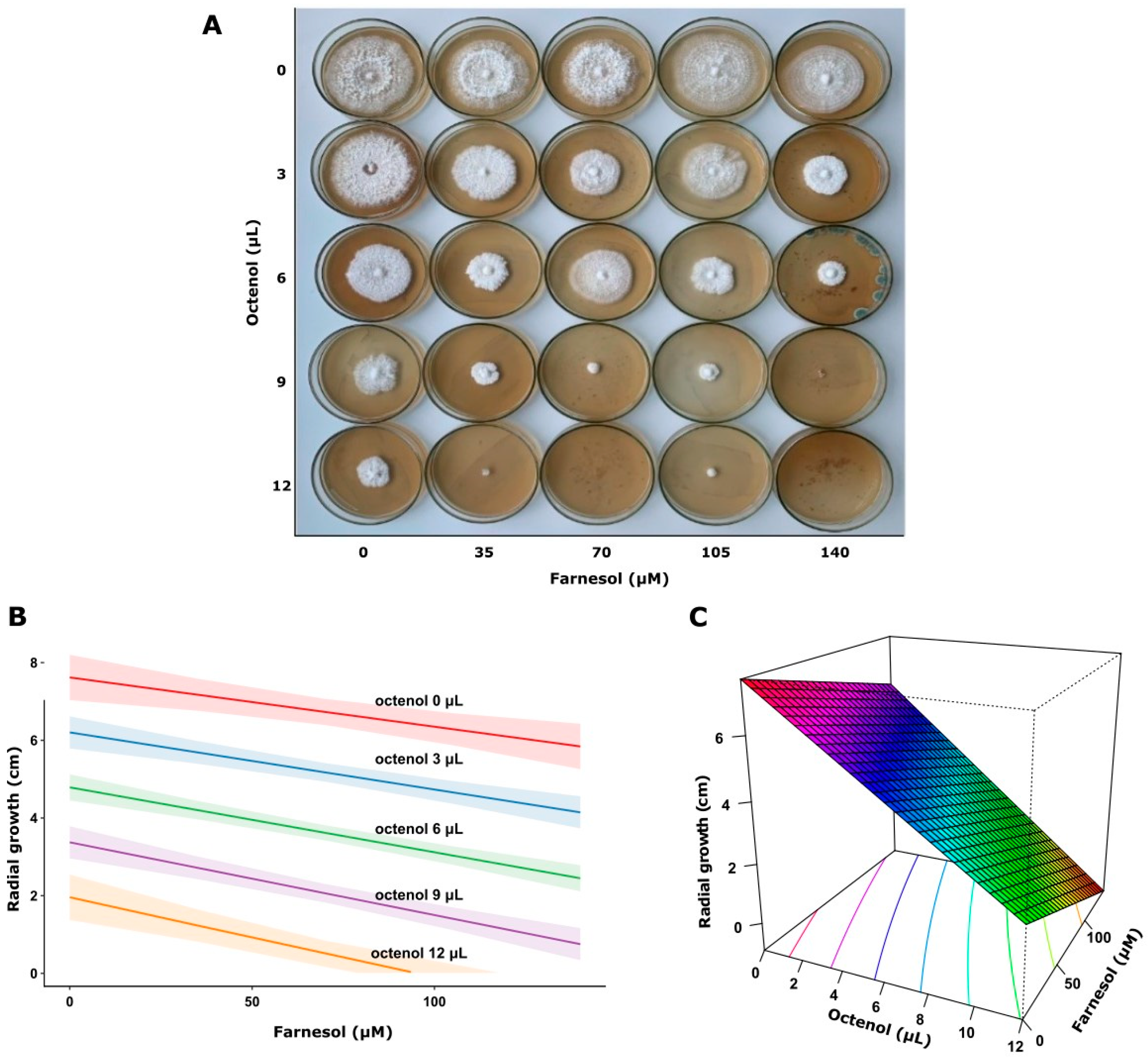

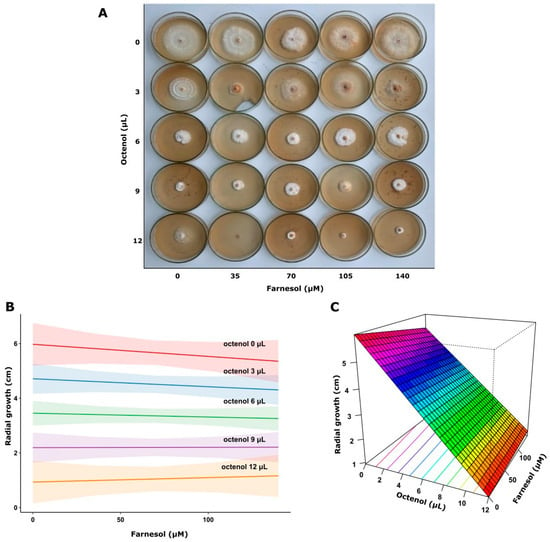

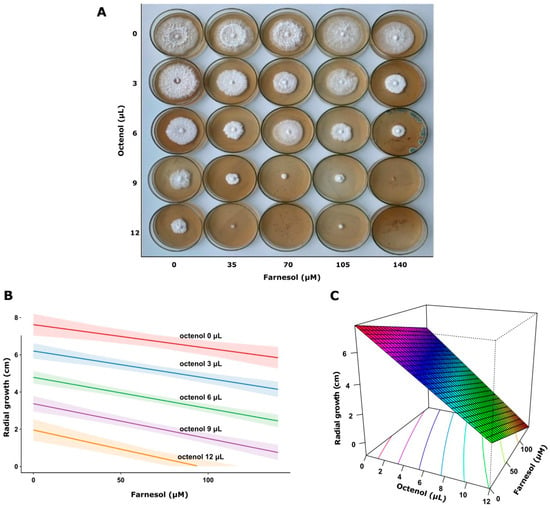

This analysis demonstrated that higher octenol concentrations significantly inhibited fungal growth in both strains (p < 0.0001). In contrast, farnesol showed no significant effect on the response variable (p = 0.593) in F. torulosa (Figure 5). The model explained approximately 76% of the variance in the response variable (adjusted R2 = 0.764). Consistent with these results, the surface response graph shows the independent inhibitory effect of octenol. Conversely, the radial growth of I. tamaricis was negatively affected by farnesol (p < 0.0001) and octenol (p < 0.0001) (Figure 6), with response surface graphs indicating a linear negative relationship for both morphogens. The model explained approximately 92% of the variance in the response variable (adjusted R2 = 0.923).

Figure 5.

Growth of F. torulosa on increasing farnesol-octenol concentrations. (A) Petri dishes with MEA medium inoculated in the center, (B) Contour plot, and (C) surface plot of the growth radius in response to the concentration of both morphogens (adjusted R2 = 0.764).

Figure 6.

Growth of I. tamaricis on increasing farnesol-octenol concentrations. (A) Petri dishes with MEA medium inoculated in the center, (B) Contour plot, and (C) surface plot of the growth radius in response to the concentration of both morphogens (adjusted R2 = 0.923).

3.2. Mycelium Growth in Liquid Medium

In F. torulosa, farnesol significantly reduced fungal biomass (p = 0.011), whereas octenol showed no significant effect on the response variable (p = 0.195). In parallel, the assessment of Inocutis tamaricis revealed that the individual presence of octenol (p = 0.634), and farnesol (p = 0.809), as well as the presence of both compounds together (p = 0.177) did not elicit significant responses to either compound (Figure 4C,D).

3.3. Laccase Activity

Laccase activity of both strains at 11 and 21 days is presented in Figure 4E,F. In F. torulosa, farnesol significantly increased enzyme activity (p = 0.006), and in I. tamaricis a similar tendency was observed but did not reach statistical significance.

3.4. Effect on Mycelium Differentiation

Fuscoporia torulosa melanized patches (Figure 2) consisted of dimitic brown mycelium with a high proportion of thick-walled skeletal hyphae (Figure 2C). Only scattered skeletal hyphae were found in the colony’s whitish areas (Figure 2B). In I. tamaricis, melanized hyphal knots (Figure 5) consisted of brown dimitic mycelia (Figure 3B), with a much higher proportion of skeletal hyphae than in the rest of the colony (Figure 3C). The melanized area and the number of hyphal knots varied across treatments, and responses to the morphogens differed between species.

Fuscoporia torulosa (Figure 4A) showed significantly smaller dimitic melanized area in the presence of octenol (p < 0.0001), but I. tamaricis (Figure 4B) showed no effect of this volatile on the number of knots (p = 0.267). On the contrary, the number of hyphal knots in I. tamaricis was significantly higher (p = 0.004) in cultures containing farnesol. The presence of farnesol in F. torulosa showed no significant differences in the melanized surface (p = 0.054).

4. Discussion

Our present results reveal that responses to farnesol and octenol vary widely across species and culture media. Octenol inhibited the hyphal growth of both species in solid medium, but had no effect in liquid culture. This might be the result of the different exposition of hyphae to this volatile compound. In agarized medium, a significant portion of the mycelia is exposed to the air, increasing the area exposed to octenol. In contrast, mycelium grown in a liquid medium primarily develops submerged, thus limiting its exposure to volatiles. Additionally, the larger headspace volume of Erlenmeyer flasks compared to Petri dishes results in a lower final octenol concentration in the gas phase than in the agarized cultures.

Farnesol inhibited the radial growth of I. tamaricis in agarized media but had no significant effect in liquid media, whereas it had the opposite effect on F. torulosa cultures. This highlights the need for further studies on the impact of concentration and application mode.

High variability in response to these compounds has been observed in diverse studies. Farnesol has been reported to inhibit the growth of Candida albicans [18], Pycnoporus sanguineus, and Trametes versicolor [45]. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [22] did not observe any effect on the biomass production or radial growth of Trametes (Coriolus) versicolor, likely due to the low dose assayed. Regarding structural differentiation, Wang et al. [22] reported that farnesol induces a hyperbranched, bulbous-tip hyphal morphology, an effect that was not observed by Backes et al. [43] for the same species. This high sensitivity of hyphal growth to dose and culture type underscores the need to accurately determine the dose and timing of application to achieve desired results.

Farnesol stimulated laccase production in F. torulosa, and a similar trend, although not statistically significant, was observed in I. tamaricis. These results align with previous studies conducted on other white-rot fungi [22,23,45]. Research indicates that farnesol increases intracellular oxidative stress [22,23,45], which appears to enhance laccase production. This is aligned with the role attributed to laccases in defending the organism against oxidative stress [23,46,47]. In contrast, octenol did not affect laccase activity, even though it did affect differentiation and mycelial growth, suggesting that its mechanism of action does not involve this enzyme. Despite these variable responses, our assays suggest that laccases are probably not mediating the differentiation of skeletal hyphae or hyphal knots.

In terms of hyphal differentiation, farnesol stimulated it in I. tamaricis but not in F. torulosa. Previous reports have noted that farnesol can affect fungal cell morphology; in Candida albicans, this compound blocks the yeast-to-mycelium shift [18]. It has also been reported to cause hyperbranching and morphological changes in the hyphae of Trametes versicolor [22]. However, there is no consensus on the effects of farnesol on hyphal morphology due to the limited number of studies and the contrasting results obtained (cfr. 45).

The relationship between phenoloxidase activity and hyphal differentiation was unclear from our results. Farnesol stimulated laccase activity in F. torulosa, but increased hyphal differentiation only in I. tamaricis. Laccase activity has been associated with enhanced mycelial differentiation and fruiting body formation [8,9,27,28,29]. In our study, the increase in laccase activity of F. torulosa was not reflected in hyphal differentiation. The differences in responses between species observed in our study may be due to differences in sensitivity. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effects of different doses across species and the interactions with other enzymes.

In line with the findings of Eastwood et al. [17], who reported that octenol at a concentration of 350 ppm inhibits the formation of hyphal knots in Agaricus bisporus, octenol was also found in our assay to reduce hyphal differentiation, even at a lower concentration (approx. 150 ppm in the headspace). The colonies of F. torulosa exhibited a significantly smaller dimitic area upon exposure to this compound. Colonies of I. tamaricis tended to show fewer hyphal knots in the presence of octenol, although the differences in this case were not statistically significant. In the latter, the dose may have been too low to detect substantial differences, as the effect of octenol is highly dose dependent [17]. Octenol is a part of a broader set of volatile organic compounds that regulate fungal development and ecological interactions [48]. Previous studies have demonstrated that octenol functions as a volatile regulator of development in Agaricus bisporus, inhibiting the formation of hyphal knots and primordia without significantly affecting vegetative mycelial growth. Wood & Blight, cited by Noble et al. [16] found that 1-octen-3-ol inhibited fruit-body formation in Agaricus bisporus, but not mycelial growth on agar culture. Noble et al. [16] showed that the presence of octenol blocks the transition to fruiting, thereby maintaining the mycelium in a vegetative state, and they reported no effect on mycelial growth. In contrast to these studies, we found that octenol markedly reduced colony radial growth, consistent with studies by and Wang et al. [49] and Yu et al. [50], which showed inhibition of mycelial proliferation in plant-pathogenic fungi in response to this alcohol. Also, the volatile nature of some of these molecules suggests they can be applied even at later stages of the culture, thereby avoiding the delayed growth observed in our experiments and taking advantage only of the induction of the desired hyphal morphologies.

Complex hyphal systems have been shown to correlate with increased resistance of mycelium composites of aphyllophoroid fungi [51]. However, skeletal or connective hyphae are sometimes only expressed in fruiting bodies of fungi, but not in the mycelium. For this reason, the interesting mechanical characteristics of basidiome tissues cannot always be replicated using solid-state fermentation for structural purposes. The possibility of modulating the differentiation of these structures paves the way for the application of morphogens to produce mycelium matrices with improved properties for diverse applications. The absence of functional material testing is a limitation of this preliminary study; this, along with the incorporation of micromechanical testing, is already underway and will be the subject of a future publication on the response of these fungal species in Solid State Fermentation.

5. Conclusions

According to these results, chemical modulation of morphogenesis via volatile and semi-volatile compounds such as farnesol and octenol is a potential strategy for controlling the texture of mycelium-based products. Given the relationship between texture (mechanical properties) and hyphal structure, the controlled application of morphogenetically active substances may help modulate specific structural and mechanical features.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the response of these species to chemical compounds is complex, underscoring the need for further investigations to obtain accurate data regarding the concentrations to be applied in accordance with specific objectives. In this context, the present work provides a foundation for more in-depth research, as both strains responded to the compounds tested.

Although further assays in solid-state fermentation and on a larger scale are needed to demonstrate the feasibility of differentiation in productive processes, the low octenol doses required to trigger thick-walled hyphae shown here indicate that this technology can be a viable alternative for modifying the resistance of the resulting materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S.-R., F.K. and F.M.C.; methodology, P.S.-R., F.K. and F.M.C.; software, P.S.-R., A.G., F.M.C. and A.L.P.; validation, A.G. and F.K.; formal analysis, P.S.-R., A.G. and A.L.P.; investigation, P.S.-R., F.K. and F.M.C.; resources, F.K.; data curation, P.S.-R., F.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.-R., F.M.C. and F.K.; writing—review and editing, P.S.-R., A.G. and F.K.; visualization, P.S.-R., F.M.C. and A.L.P.; supervision, F.K. and A.G.; project administration and funding acquisition, P.S.-R., A.G. and F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (CDTI), grant number SNEO-20241359 (P.I.: F.K.), and by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (Agencia I+D+i), Argentina (PICT-Startup 2020-00009, P.I.: A.G.). A.G. and F.K. are Career Members of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas of Argentina (CONICET).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Isabel M. Casillas Chacón for her guidance in the collection of the Fuscoporia exemplar and Mauricio Ghilardi Bordón for his invaluable assistance in the laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| CDTI | Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación |

| F | Farnesol |

| IU | International Units of enzymatic activity |

| MEA | Malt Extract Agar |

| O | Octenol |

| VarExp | Exponential Variance Structure |

| VarPower | Power Variance Structure |

References

- Porter, D.L.; Naleway, S.E. Hyphal systems and their effect on the mechanical properties of fungal sporocarps. Acta Biomater. 2022, 145, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegler, D.N. Hyphal analysis of basidiomata. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clémençon, H. Cytology and Plectology of the Hymenomycetes; Cramer in der Gebr. Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haneef, M.; Ceseracciu, L.; Canale, C.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Athanassiou, A. Advanced Materials From Fungal Mycelium: Fabrication and Tuning of Physical Properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreerag, N.K.; Kashyap, P.; Shilpa, V.S.; Thakur, M.; Goksen, G. Recent advances on mycelium based biocomposites: Synthesis, strains, lignocellulosic substrates, production parameters. Polym. Rev. 2025, 65, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Tudryn, G.; Bucinell, R.; Schadler, L.; Picu, R.C. Morphology and mechanics of fungal mycelium. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandelook, S.; Elsacker, E.; Van Wylick, A.; De Laet, L.; Peeters, E. Current state and future prospects of pure mycelium materials. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leatham, G.F.; Stahmann, M.A. Studies on the laccase of Lentinus edodes: Specificity, localization and association with the development of fruiting bodies. Microbiology 1981, 125, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetchinkina, E.P.; Gorshkov, V.Y.; Ageeva, M.V.; Gogolev, Y.V.; Nikitina, V.E. Activity and expression of laccase, tyrosinase, glucanase, and chitinase genes during morphogenesis of Lentinus edodes. Microbiology 2015, 84, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, A.D.; Griffith, G.S.; Wildman, H.G. Induction of metabolic and morphogenetic changes during mycelial interactions among species of higher fungi. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1994, 22, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béni, Z.; Dékány, M.; Sárközy, A.; Kincses, A.; Spengler, G.; Papp, V.; Hohmann, J.; Ványolós, A. Triterpenes and phenolic compounds from the fungus Fuscoporia torulosa: Isolation, structure determination and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Ming, Y.; Yu, M.; Lou, F.; Yang, S.; Wu, G.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, X. Optimization of flavonoids extraction from Inocutis tamaricis and biological activity analysis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5619–5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Q.; Mao, X.J.; Geng, L.J.; Yang, G.M.; Xu, C.P. Production optimization, preliminary characterization and bioactivity of exopolysaccharides from Incutis tamaricis (Pat.) Fiasson & Niemela. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Ordorica, A.; Patiño-Medina, J.A.; Meza-Carmen, V.; Macías-Rodríguez, L. Volatile Fingerprint Mediates Yeast-to-Mycelial Conversion in Two Strains of Beauveria bassiana Exhibiting Varied Virulence. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottier, F.; Mühlschlegel, F.A. Communication in fungi. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012, 1, 351832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, R.; Dobrovin-Pennington, A.; Hobbs, P.J.; Pederby, J.; Rodger, A. Volatile C8 compounds and pseudomonads influence primordium formation of Agaricus bisporus. Mycologia 2009, 101, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, D.C.; Herman, B.; Noble, R.; Dobrovin-Pennington, A.; Sreenivasaprasad, S.; Burton, K.S. Environmental regulation of reproductive phase change in Agaricus bisporus by 1-octen-3-ol, temperature and CO2. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 55, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosel, D.D.; Dumitru, R.; Hornby, J.M.; Atkin, A.L.; Nickerson, K.W. Farnesol concentrations required to block germ tube formation in Candida albicans in the presence and absence of serum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 4938–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, T.; Onodera, K.; Hosoya, T.; Takamatsu, Y.; Kinoshita, T.; Tago, K.; Kogen, H.; Fujioka, T.; Hamano, K.; Tsujita, Y. Schizostatin, a novel squalene synthase inhibitor produced by the mushroom, Schizophyllum commune I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, K.W.; Atkin, A.L.; Hornby, J.M. Quorum sensing in dimorphic fungi: Farnesol and beyond. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3805–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kües, U.; Khonsuntia, W.; Subba, S.; Dörnte, B. Volatiles in communication of Agaricomycetes. Physiol. Genet. Sel. Basic Appl. Asp. 2018, 15, 149–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.F.; Guo, C.; Ju, F.; Samak, N.A.; Zhuang, G.Q.; Liu, C.Z. Farnesol-induced hyperbranched morphology with short hyphae and bulbous tips of Coriolus versicolor. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, F.; Ma, A.; Zhuang, G.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.; Guo, C.; Liu, C. Farnesol stimulates laccase production in Trametes versicolor. Eng. Life Sci. 2016, 16, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.B.V.; Júnior, V.G.C.; Júnior, A.D.P.M.; Garcia, H.J.; Nogueira, E.S.C.; Mazzoni, T.S.; Martins, J.R.; Moda, L.M.R.; Barchuk, A.R. Farnesol, a component of plant-derived honeybee-collected resins, shows JH-like effects in Apis mellifera workers. J. Insect Physiol. 2024, 154, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohbot, J.D.; Durand, N.F.; Vinyard, B.T.; Dickens, J.C. Functional development of the octenol response in Aedes aegypti. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetchinkina, E.; Kupryashina, M.; Gorshkov, V.; Ageeva, M.; Gogolev, Y.; Nikitina, V. Alteration in the ultrastructural morphology of mycelial hyphae and the dynamics of transcriptional activity of lytic enzyme genes during basidiomycete morphogenesis. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, T.J.; Phillips, L.E. Study of phenoloxidase activity during the reproductive cycle in Schizophyllum commune. J. Bacteriol. 1973, 114, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.A.; Goodenough, P.W. Fruiting of Agaricus bisporus: Changes in extracellular enzyme activities during growth and fruiting. Arch. Microbiol. 1977, 114, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.A. Production, purification and properties of extracellular laccase of Agaricus bisporus. Microbiology 1980, 117, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, K. Phenol oxidases and morphogenesis in Podospora anserina. Genetics 1968, 60, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.L.; Willetts, H.J. Polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis of enzymes during morphogenesis of sclerotia of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Microbiology 1974, 81, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Fungal laccases–occurrence and properties. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 215–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Sengupta, S.; Mukherjee, M. Importance of laccase in vegetative growth of Pleurotus florida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4120–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Du, P.; Vlasák, J.; Wu, F.; Dai, Y.C. Global diversity and phylogeny of Fuscoporia (Hymenochaetales, Basidiomycota). Mycosphere 2020, 11, 1477–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobad-Nejhad, M.; Kotiranta, H. The genus Inonotus sensu lato in Iran, with keys to Inocutis and Mensularia worldwide. Annales Botanici Fennici 2008, 45, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhar, F.; Truong, C.; Smith, M.E.; Matheny, P.B.; Nouhra, E. Molecular and morphological evidence place Pholiota psathyrelloides from Patagonia within the ectomycorrhizal genus Psathyloma (Agaricales). N. Z. J. Bot. 2019, 57, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semighini, C.P.; Hornby, J.M.; Dumitru, R.; Nickerson, K.W.; Harris, S.D. Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Aspergillus nidulans reveals a possible mechanism for antagonistic interactions between fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Son, S.Y.; Lee, C.H. Critical thresholds of 1-Octen-3-ol shape inter-species Aspergillus interactions modulating the growth and secondary metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hayati, S.K.; Kim, E.; de la Mata, A.P.; Harynuk, J.J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, R. Henry’s law constants and indoor partitioning of microbial volatile organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7143–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszczynski, A.; Crawford, R.L. Degradation of azo compounds by ligninase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium: Involvement of veratryl alcohol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 178, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastwirth, J.L.; Gel, Y.R.; Miao, W. The impact of Levene’s test of equality of variances on statistical theory and practice. Statist. Sci. 2009, 24, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, S.L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed.; Harper Collins College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Büyüköztürk, S. Sosyal Bilimler icin Veri Analizi El Kitabi; Pegem Yayincilik: Ankara, Turkey, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Backes, E.; Kato, C.G.; de Oliveira Junior, V.A.; Uber, T.M.; dos Santos, L.F.O.; Corrêa, R.C.G.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M. Overproduction of laccase by Trametes versicolor and Pycnoporus sanguineus in farnesol-pineapple waste solid fermentation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszek, M.; Grzywnowicz, K.; Malarczyk, E.; Leonowicz, A. Enhanced extracellular laccase activity as a part of the response system of white rot fungi: Trametes versicolor and Abortiporus biennis to paraquat-caused oxidative stress conditions. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2006, 85, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, P.; Ramchiary, N. Laccase isozymes from Ganoderma lucidum MDU-7: Isolation, characterization, catalytic properties and differential role during oxidative stress. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 113, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J.J.; Scholtmeijer, K.; Sonnenberg, A.S.; van Peer, A. Critical factors involved in primordia building in Agaricus bisporus: A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Huang, M.; Peng, Y.; Yang, W.; Shi, J. Antifungal activity of 1-octen-3-ol against Monilinia fructicola and its ability in enhancing disease resistance of peach fruit. Food Control 2022, 135, 108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Tang, J.; Peng, W.; Tan, H. Application of the mushroom volatile 1-octen-3-ol to suppress a morel disease caused by Paecilomyces penicillatus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 4787–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, M.; Rugolo, M.; Robledo, G.; Kuhar, F. Evaluation of mycelium composite materials produced by five Patagonian fungal species. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2022, 24. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-221X2022000100435 (accessed on 23 January 2026). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.