Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing threat to public health and the environment, especially in vulnerable ecosystems such as the Amazon. The confluence of the Marañón, Utcubamba, and Chinchipe rivers, known as the Pongo de Rentema, is a strategic area where water pollution could facilitate the spread of antibiotic resistance genes. This study aims to assess water quality in this region under the “One Health” approach by analyzing physicochemical parameters, heavy metals, and the presence of antimicrobial resistance genes. Water samples were collected from five sampling points during September and October 2024. Physicochemical parameters were analyzed in situ, and heavy metal concentrations were determined using atomic emission spectrophotometry. The presence of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was evaluated through selective culture, and the detection of resistance genes (marA, ermC, amp, QEP, and qEmarA) was performed using conventional PCR. Physicochemical parameters were within the limits established by Peruvian regulations, except for total dissolved solids in the Utcubamba River. Elevated levels of lead and chromium were detected at some points. Additionally, resistance genes were identified in E. coli and P. aeruginosa, providing evidence of antimicrobial resistance dissemination in the water. Water pollution in the Pongo de Rentema poses an environmental and public health risk due to the presence of heavy metals and antimicrobial resistance genes. Continuous monitoring and environmental management strategies under the “One Health” approach are recommended to mitigate these risks.

1. Introduction

Water quality is an essential component for human, animal, and environmental health. However, bodies of water can be vectors for contamination and the spread of antibiotic resistance, as microbiological contamination of rivers and lakes comes mainly from domestic, industrial, and agricultural wastewater containing not only pathogenic bacteria but also residues of antibiotics used in the treatment of human and animal diseases, altering water quality due to its toxicity [1].

These residues reach the water, exerting selective pressure on bacterial populations, which favors the proliferation of resistant strains [2]. Consequently, the excessive and indiscriminate use of antibiotics in livestock farming, together with inadequate wastewater treatment, are key factors contributing to the release of these drugs into the environment. These practices lead to the spread of resistance genes, which can be transferred between bacterial species through mechanisms such as plasmids, amplifying the problem [3,4]. Therefore, it is essential to conduct studies in aquatic environments to identify the presence of resistance genes in these areas, which might otherwise go unnoticed.

On the other hand, water contaminated with resistant bacteria represents a direct route of exposure for communities that depend on these resources for consumption, hygiene, and recreational activities. In many Amazonian regions, rural communities depend on nearby rivers and lakes for their daily lives, making contaminated water a direct source of antibiotic-resistant infections [5]. Amazonian aquatic ecosystems are home to a wide variety of species and can suffer significant alterations in their microbiota due to the presence of resistant bacteria, affecting key ecological processes, water quality, and species relationships. It also favors resistant strains, displacing sensitive bacteria and facilitating the bioaccumulation of heavy metals and pollutants, which puts both aquatic species and humans who depend on these resources at risk [6].

In this context, water quality assessment must take into account not only physical-chemical parameters but also the presence of biological and chemical contaminants and antibiotic-resistant pathogens [7]. Heavy metals are particularly problematic, as they are toxic to aquatic organisms and humans, even at low concentrations [8]. In addition, pathogenic microorganisms, such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are key indicators of fecal contamination in water bodies, and their presence may be associated with the transmission of infectious diseases [9,10,11,12]. The spread of resistance genes in aquatic bacteria poses a threat to public health, as it facilitates the spread of antibiotic-resistant strains in aquatic ecosystems and in people who consume contaminated water [13].

The presence of resistance genes in these bacteria, which allow them to survive and proliferate in environments treated with antibiotics, poses a risk to global public health [14,15]. The spread of these genes in aquatic environments is particularly concerning, as it can facilitate the transfer of resistance between different bacterial species, including those that are pathogenic to humans [16].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the most significant challenges facing modern medicine. It is estimated that by 2050, antibiotic-resistant infections could cause more deaths than cancer, due to the inability to treat common infections with existing drugs [17]. In aquatic environments, such as Amazonian rivers, antibiotic-resistant pathogens can survive for long periods and multiply, facilitating their spread to surrounding ecosystems and human communities that depend on these water resources [18].

The analysis of resistance genes has become a key tool for understanding the extent of AMR in natural environments. Some of the most studied genes in this context are marA, associated with multidrug resistance in E. coli and P. aeruginosa; ermC, related to erythromycin resistance; amp, which confers resistance to ampicillin; QEP, related to resistance to ciprofloxacin; and qEmarA, related to resistance to fluoroquinolones and other antibiotics used in the treatment of bacterial infections [19,20,21]. The detection of these genes in water samples is essential for identifying the presence of resistant strains and assessing the risks associated with antimicrobial resistance contamination.

The excessive use of antibiotics in livestock farming, the discharge of domestic wastewater [22] and hospital wastewater without adequate treatment, and poor environmental regulation are some of the main factors contributing to the spread of these genes in aquatic environments [23]. In addition, the ability of bacteria to exchange genetic material, such as plasmids carrying resistance genes, amplifies the risk of cross-resistance, further exacerbating the problem [24].

AMR in water bodies also has implications for aquatic biodiversity, as resistant bacteria can alter ecological dynamics by displacing sensitive species and modifying the microbial communities that maintain the balance of aquatic ecosystems. This is particularly concerning in fragile ecosystems such as the Amazon, where alterations in aquatic microbiota can trigger chain reactions that affect other species, including those that form the basis of the food chain. In this sense, this study is part of the One Health initiative, which recognizes the interconnectedness between human, animal, and ecosystem health [25]. This approach is essential for understanding how environmental factors and human activities affect both public health and biodiversity [26]. The Pongo de Rentema, located in the Amazon region of Peru, is a confluence of three major rivers: Marañón, Utcubamba, and Chinchipe. This area is representative of Amazonian ecosystems, which are particularly vulnerable to pollution from intensive agriculture, mining, and waste management practices [27]. The Pongo del Rentema is home to rich biodiversity, but it also faces growing problems from climate change, pollution, and human activities. In these places, water quality is constantly threatened by pollution from various human activities, such as mining, intensive agriculture, and the discharge of untreated wastewater. These factors not only affect the physical-chemical parameters of the water, such as pH, temperature, and total dissolved solids (TDS), but also the presence of biological and chemical contaminants that have direct implications for public and environmental health [28].

In this regard, monitoring resistance genes in aquatic environments is important as a key strategy for identifying and mitigating the risks associated with the spread of resistant strains, with the aim of contributing to the formulation of more effective public policies for water resource management and public health protection [29]. Therefore, the need to conduct studies on antimicrobial resistance in aquatic environments is essential not only for public health but also for environmental conservation.

Based on the above, this study evaluated for the first time the water quality in the Pongo de Rentema, a strategic ecosystem in the Amazon region of Peru, by analyzing physical-chemical parameters, heavy metals, and the presence of antimicrobial resistance genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Delimitation of Study and Sampling

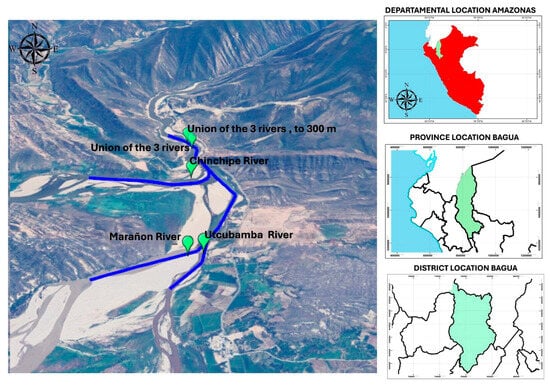

This research work was carried out during the months of September and October 2024; at the junction of the three main rivers of the Amazon Region, in Peru, called the Pongo de Rentema (Table 1), the Pongo Rentema sector is located in the province of Bagua, in the Amazonas region, in northern Peru (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Delimitation of the study according to the sampling points at the confluence of the rivers.

Figure 1.

Location of sampling points.

Pongo means “door” in Quechua; at this point, the Chinchipe River, which comes from the north and originates in Ecuador, joins the Marañón River [30], while the Utcubamba River, which originates in the Punta de Arena hill, in the province of Chachapoyas [31], coming from the south, also joins the Marañón River, one of the main rivers in the Amazon region [32].

Water samples were taken in accordance with the methodological considerations established by the Ecology and Environmental Protection Department’s “Water Resources Protection Area” [33]. In all cases, sampling was carried out 5 m from the riverbank at a depth of 50 cm, in a previously sterilized container, rinsing twice with the same water to be sampled against the current according to the sampling protocol and taking 1 L of water as a sample; this was repeated 4 times. With respect to microbiological analysis and physical-chemical parameters, analysis was conducted in the Microbial Biotechnology laboratories of the Universidad Nacional Intercultural Fabiola Salazar Leguia de Bagua in the Amazonas Region of Peru.

2.2. Analysis of Physical-Chemical Parameters and Heavy Metals

The physical-chemical analysis was carried out with the Multi-parameter PCSTestr TM 35 Series (Eutech Instruments Oaklon®, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) for pH, conductivity, total dissolved solids (TDS), and temperature. For the determination of heavy metals, the 4210 MP-AES Atomic Emission Spectrophotometry equipment was used, manufactured by Agilent Technologies, USA, was used, under methods 3120-B, APHA, AWWA, and WWF, and the Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) method for MP-AE was used to determine nickel, lead, and chromium. The physical-chemical parameters were measured at the collection point, while the heavy metals were measured in the laboratory, at most 4 h after collection. The legal limits accepted in the water quality standards of Peru are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Water quality standards of Peru [34].

2.3. Isolation and Extraction of DNA

Water samples were obtained from different rivers detailed above; all containers used for sampling were previously sterilized. Volumes of 1 L of water sample were used. m-ColiBlue24® (M00PMCB24, (HACH Company, Loveland, CO, USA) was used to detect and quantify E. coli after 24 h of incubation at 35 °C, and for P. aeruginosa, the culture medium cetrimide agar was used.

Table 3 shows that E. coli was isolated at the junction of the three rivers (M2), 2 colonies 300 m (M3) from this junction and a colony in the Marañón River (M5). Likewise, a colony of P. aeruginosa was isolated at the junction of the three rivers to 300 m away (M3) and a colony in the Marañón River (M4).

Table 3.

DNA isolation and extraction.

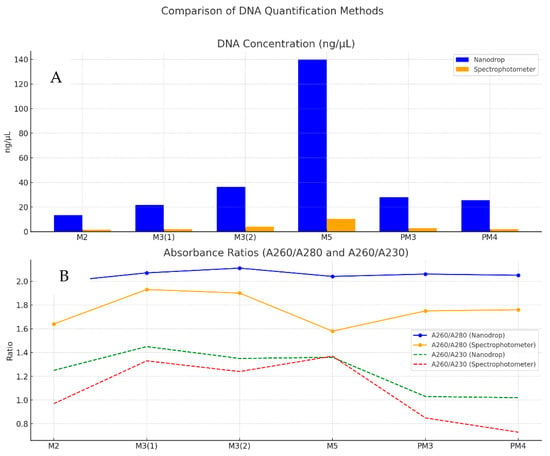

The quantification of DNA concentration was performed under the basic photometry procedure using an Eppendorf Fluorescence BioSpectrometer and Nanodrop One of Thermofisher Scientific [35,36].

Determination of resistance genes.

Determination of antibiotic resistance genes was performed by conventional PCR with specific reactions for each case (Table 4).

Table 4.

PCR reactions.

The importance in the choice of antimicrobial resistance genes (Table 5) in this study, specifically marA, ermC, amp, QEP, and qEmarA, is essential to understand the risks associated with microbiological pollution in the Amazonian water bodies and to address public health problems related to antibiotic resistance. Next, the importance of each of these genes in the context of the investigation is detailed.

Table 5.

PCR program.

The marA gene is one of the main mediators of multi-antibiotic resistance in bacteria such as E. coli and P. aeruginosa. This gene is associated with an increased capacity to expel a wide range of antibiotics from the interior of the bacterial cell, which gives them a significant resistance to drugs commonly used in the treatment of bacterial infections. Its presence in water samples indicates that the bacteria present in these bodies of water have a greater capacity to resist antimicrobial treatments, which raises a risk to public health, since these bacteria can be difficult to treat in cases of human infections [19].

The ermC gene is related to erythromycin resistance, an antibiotic used mainly to treat respiratory infections and other bacterial infections. Erythromycin resistance is particularly worrying, since this antibiotic belongs to the class of macrolides, which are essential for the treatment of infections in patients allergic to other antibiotics such as penicillin [42]. The detection of ermC in water samples suggests that antimicrobial resistance is not limited to common-use antibiotics but also affects crucial drugs in clinical medicine, which increases the risk of ineffective treatments.

amp is a gene associated with ampicillin resistance, a broad-spectrum antibiotic used in the treatment of common bacterial infections. Ampicillin is one of the first therapeutic options for a variety of infections, but the development of resistance to this medicine is worrying because it can complicate the treatment of diseases that were previously easy to treat [43]. The presence of amp in the water samples of the studied rivers underlines concern about the growing resistance to essential antibiotics, which highlights the need for constant surveillance in water sources.

The presence of the QEP gene is indicative of resistance to ciprofloxacin, an antibiotic widely used to treat urinary, respiratory, and gastrointestinal tract infections. Ciprofloxacin resistance is particularly worrying, since it is one of the most prescribed antibiotics in cases of serious bacterial infections. The spread of this gene in bodies of water highlights the need to monitor the effects of human activities, such as wastewater discharge and indiscriminate use of antibiotics in agriculture, in the propagation of this resistance [44].

The qEmarA gene is linked to resistance to fluoroquinolones, a group of last-line antibiotics used to treat serious infections. Fluoroquinolones are crucial in the treatment of urinary and respiratory infections, and their effectiveness is diminished when bacteria acquire resistance through genes such as qEmarA [45]. This gene is especially important in aquatic environments, where resistant bacteria can persist and multiply, exposing communities close by to health risks.

The relevance of the selection of these five resistance genes allowed us to cover a broad spectrum of antibiotics used both in human and veterinary medicine. The inclusion of genes related to the resistance to common-use and last-line antibiotics is essential to understand the complete panorama of antimicrobial resistance in aquatic ecosystems. Since the resistance to antibiotics in aquatic environments can spread rapidly through ecosystems, the surveillance of these genes in aquatic bodies is crucial to prevent outbreaks of resistant infections and to protect both human health and aquatic biodiversity.

In addition, these genes were selected for their high prevalence in bacterial populations of contaminated environments and for their ability to confer resistance not only to a specific antibiotic but to multiple kinds of antibiotic resistance, which amplifies the risk of infections that are difficult to treat.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In order to compare the parameters between the sampling points and determine if there were significant differences, the post hoc test (Tukey HSD) was performed, after compliance with data normality and homogeneity of variances. All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS software, version 26.0 (IBM SPSS software, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

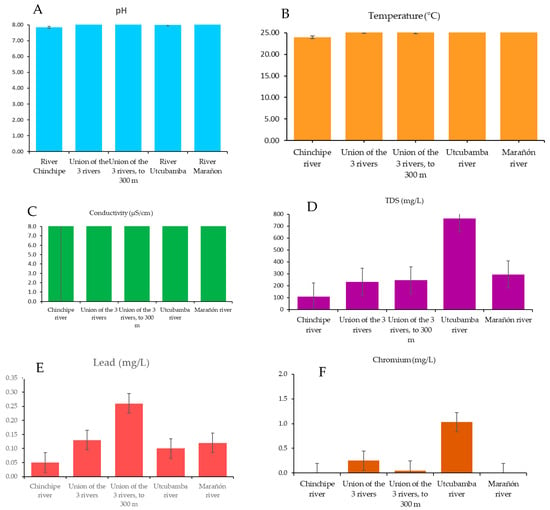

The physical-chemical parameters were within the legal limits established by DS No. 004-2017-MINAM (Table 6), and Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of the behavior of the physical-chemical parameters at the sampling points. However, high concentrations of TDS (542 mg/L) were observed, and electrical conductivity reached 765 μS/cm. With regard to heavy metals, levels above the permitted limits were detected, particularly for lead at all sampling points and for chromium only at sampling points M2 (Union of the 3 rivers), M3 (Union of the 3 rivers, to 300 m), and M4 (Utcubamba River). Nickel was found to be within Peruvian standards and was only detected in the Chinchipe River (M1). With regard to statistical analysis, significant differences were found at all sampling points for electrical conductivity, while there were no significant differences for total dissolved solids.

Table 6.

Physicochemical parameters and heavy metals.

Figure 2.

Physical-chemical parameters: pH behavior (A); temperature behavior (B); electrical conductivity behavior (C); total dissolved solids behavior (D); lead behavior (E); chromium behavior (F).

The concentrations measured by the Nanodrop are considerably higher than those obtained by the spectrophotometer (Table 7). This may be due to the fact that the Nanodrop is more sensitive. In all cases, the concentration obtained with the spectrophotometer is lower, with a noticeably wide difference in samples with high concentrations (e.g., M5). However, the Nanodrop readings (Figure 3) are in the ideal range (1.99–2.11), and most PCR protocols work well with DNA concentrations between 10 and 100 ng/µL [46].

Table 7.

DNA concentration, using different methodologies.

Figure 3.

Comparison of DNA concentration and purity: comparison of methods by sampling point (A); absorbance behavior according to methods (B).

Bacterial resistance genes were identified in all isolated strains of E. coli (04) and P. aeruginosa (02), as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Genes of resistance found.

4. Discussion

Water quality in Amazonian ecosystems such as the Pongo de Rentema is a reflection of the complex interaction between environmental factors, human activities, and biological processes. The results of this study on physical-chemical parameters, the presence of heavy metals, and antimicrobial resistance genes reveal a series of findings that have significant implications for both public health and environmental conservation in the Amazon region of Peru.

The physical-chemical parameters of the water in the Pongo de Rentema showed that, in general, they comply with the limits established by Peruvian legislation for the conservation of the aquatic environment [47]. However, they vary significantly (p < 0.05) between the different sampling points, especially for TDS and heavy metals such as lead and chromium. The pH of the samples ranged between 7.9 and 8.2, values that are typical for Amazonian ecosystems, which usually have slightly alkaline waters due to the interaction with soils rich in minerals and organic compounds [48]. Similarly, the water temperature remained within the expected range for this tropical region, varying between 24 °C and 25.9 °C, which is also consistent with previous studies reporting constant temperatures in Amazonian rivers [49].

However, total dissolved solids (TDS) levels were particularly high [47] at sampling points in the Utcubamba River, reaching up to 542 mg/L. These values are above the levels reported in other Amazonian areas [49], which could be indicative of the presence of additional contaminants, such as organic matter, sediments, or waste from agricultural or industrial activities, and may be associated with an increased risk of microbiological and heavy metal contamination, which should be continuously monitored. On the other hand, high electrical conductivity values in the Utcubamba River (765 μS/cm) help confirm the presence of urban runoff, fertilizers, road salts, or industrial waste [31,50]; significant differences were also observed in the SSTs with the heavy metals nickel, chromium, and lead, confirming serious impacts on microorganisms, plants, and animals [51].

Regarding heavy metals, the results showed concentrations of lead and chromium above legal limits, suggesting that contamination by these metals in the region is a critical problem at the selected sampling points, raising the need for more intensive monitoring in areas with potential sources of contamination, such as mining activities and the use of fertilizers and pesticides in agriculture. Previous studies in the region, such as that conducted by Ferro et al. [25], have already warned of the risks associated with heavy metals in Amazonian rivers, where informal mining practices and deforestation contribute to the release of these pollutants into water bodies.

The presence of heavy metals remains a relevant issue, since even low concentrations can have cumulative and toxic effects on aquatic organisms and human communities that depend on these water resources. Such is the case with nickel, which was found in low concentrations in the Chinchipe River, but this may be associated with anthropogenic and natural sources. For example, Ni can be released into the environment from rocks and soils as a result of weathering [52]. In addition, the Chinchipe River is one of the rivers that contains dredges used for informal gold mining, which can cause multiple changes in aquatic organisms [53]. The bioaccumulation of heavy metals through the food chain can affect the health of aquatic animals and people who consume these resources without adequate treatment [49]; lead and chromium are known for their neurotoxic and carcinogenic effects, which reinforces the need for monitoring and mitigation strategies in the region [54,55].

Regarding antimicrobial resistance in aquatic environments, the most alarming finding of this study was the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in the bacteria Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the water samples. The presence of genes such as marA, ermC, amp, QEP, and qEmarA in all samples underlines the severity of the spread of antimicrobial resistance in Amazonian water bodies. This phenomenon is not exclusive to the region studied but rather reflects a global trend that has been documented in other tropical areas and in aquatic ecosystems around the world [15].

The presence of the qEmarA gene in P. aeruginosa could be due to horizontal gene transfer, the presence of similar resistance mechanisms, and the homology between resistance genes in different bacterial species [56,57,58]. However, P. aeruginosa is known for its ability to acquire genes from other bacteria through horizontal transfer, which occurs through plasmids, transposons, or integrons, and may have been integrated into the genome or into a plasmid present in this particular strain [57,59].

Antimicrobial resistance in aquatic environments is an emerging issue of concern for global public health. Antibiotic-resistant pathogens in Amazonian rivers could represent a significant threat to communities that rely on these water bodies for consumption, as well as to aquatic biodiversity. Indeed, several studies have shown that resistant bacteria can survive in water for long periods, allowing their spread between different ecosystems and species [60,61]. Furthermore, cross-resistance between environmental and pathogenic bacteria can generate new resistant strains that are more difficult to treat with available antibiotics.

The excessive and indiscriminate use of antibiotics in livestock farming, together with the discharge of untreated wastewater, are key factors that contribute to the spread of resistance genes in water bodies. In this sense, the Amazon region is not exempt from this phenomenon, since intensive livestock practices, mining, and expanding urban activities increase the load of microbiological and chemical pollutants in rivers [15], given that the urban populations through which these rivers flow discharge wastewater into the river due to a lack of basic sanitation.

The results of this study have implications for public health and biodiversity, as they highlight the urgent need to implement more robust environmental management and public health policies in the Amazon region. The detection of resistance genes in water bodies so close to human communities is a clear indication that antimicrobial resistance is spreading in the region and could have devastating effects if preventive measures are not taken [17]. According to the World Health Organization, [62], resistance antimicrobial can make treatments for infections common be ineffective, which risks the lives of millions of people every each year. Furthermore, the spread of antimicrobial resistance can also have indirect effects on biodiversity. Resistant bacteria can alter aquatic microbial communities, affecting ecological interactions between organisms and altering biogeochemical processes essential for the functioning of aquatic ecosystems. Previous studies have documented how antimicrobial resistance can affect the health of aquatic ecosystems by modifying the structure of the microbiota and by favoring resistant bacterial strains that can displace sensitive strains [49].

This study has provided a comprehensive overview of water quality in the Pongo de Rentema, revealing not only that physical-chemical parameters are within legal limits but also the presence of microbiological contaminants and the spread of antimicrobial resistance genes. These results are alarming, as they indicate that although the physical-chemical quality of water in the region is acceptable, microbiological risks and antimicrobial resistance are emerging problems that require immediate attention.

Integrating the One Health approach is essential to address these issues holistically, as the health of ecosystems, animals, and humans are intrinsically interconnected [60,63]. Implementing pollution control policies and constant monitoring of water quality are crucial steps to mitigate the risks associated with pollution and antimicrobial resistance in the region.

The link between this research work and One Health is given because it is a comprehensive strategy that recognizes the interdependence between the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems and promotes intersectoral collaboration to address public health challenges more effectively. This approach is particularly relevant when dealing with complex problems such as antimicrobial resistance, which affects both human and animal health and has implications for environmental health. The linkage of this research work with One Health enables a holistic understanding of the risks associated with the pollution of water bodies, the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and the impacts on aquatic ecosystems.

The presence of antimicrobial resistance genes in water samples from rivers in the Amazon region is an alarming sign that not only reflects the risks to human health but also the effects on animal and environmental health. Resistant bacteria in water, such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can affect both humans and animals, as both are exposed to water contamination. In the context of One Health, it is crucial to monitor and manage these risks in an integrated manner, since resistant bacteria do not respect species boundaries. This study, which includes the detection of resistance genes such as marA, ermC, amp, QEP, and qEmarA, contributes to the surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in aquatic ecosystems, allowing the identification of resistance hotspots in vulnerable areas [64]. The One Health approach extends here not only by recognizing the risks associated with antibiotic resistance but by promoting the shared management of environmental health and public health. The evaluation of the risks of antibiotic resistance in water involves collaboration between human health professionals, veterinary medicine, and ecologists to implement effective control strategies [65,66]

Strengthening public policies and education, which allows the integration of One Health also involves strengthening public policies and community education. The results of this study can be used to raise awareness among government authorities, local populations, and residents of native communities about the risks associated with antibiotic contamination in water bodies, as well as the need for proper environmental management. The implementation of educational programs that promote the responsible use of antibiotics and the protection of water resources is essential to reduce the impacts of antimicrobial resistance in the region.

We recognize the limited representation of studies in the Amazon region. Therefore, future research should prioritize specific monitoring in these underrepresented regions to better understand antibiotic resistance in water. Above all, this should involve prolonged sampling at different times of the year in order to observe seasonal variations without neglecting longitudinal ecological assessments in aquatic systems. It is also important to mention that this study did not address broader parameters due to a lack of financial resources for chemical supplies and sampling at different points. Therefore, future projects are being prepared to obtain funding from interested parties and thus provide historical information.

5. Conclusions

The physical and chemical parameters of the water in the Pongo de Rentema, Amazonas, Peru, remained within the limits established by Peruvian environmental regulations, indicating that, in general terms, the water in this region is suitable for conventional uses. However, total dissolved solids (TDS) levels were high at some sampling points, especially in the Utcubamba River, which has a significant impact on the development of aquatic life.

Levels of heavy metals such as lead and chromium exceeded legal limits, especially at the junction of the three rivers, suggesting that the region is exposed to potential sources of heavy metal contamination. Mining, livestock farming, and nearby industrial activities could be contributing factors that should be monitored over a longer period of time.

A key finding of this study was the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the water samples. The genes marA, ermC, amp, QEP, and qEmarA were present in all samples, indicating a widespread spread of antimicrobial resistance in the aquatic environment. This phenomenon reinforces the urgent need to address antimicrobial resistance as an environmental and public health problem in the region.

The presence of antimicrobial resistance genes in water bodies used by local communities for consumption, hygiene, and other daily activities has implications for public health and the environment, presenting a significant risk to public health.

This study contributes to knowledge by providing valuable information on water quality in a strategic region of the Peruvian Amazon, contributing to the database on contamination and the spread of antimicrobial resistance in tropical aquatic environments, highlighting the need for further research and continued monitoring in other Amazonian areas to assess the magnitude and scope of these problems in the region.

It is recommended to intensify water quality monitoring in the Amazon region, with special emphasis on the presence of heavy metals and the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes, promoting sustainable practices in agriculture and mining, and improving wastewater treatment, to reduce contamination by metals and resistant pathogens.

Implementation of policies under One Health is essential to comprehensively address the challenges of public health and environmental conservation in the Amazon.

We also recommend carrying out an in-depth study on the detection of the qEmarA gene in P. aeruginosa, such as sequencing and specificity analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.T.C., P.F., G.S. and E.M.-R.; methodology, E.T.C., E.M.-R., P.F., L.C.-R., A.G., Y.A.S.-D., R.G., E.V.P. and P.F.-G.; software, P.F. and P.F.-G.; validation, P.F. and J.B.; formal analysis, J.B., P.F.-G., E.M.-R. and G.S.; investigation, E.T.C., P.F., E.M.-R., E.V.P. and Y.A.S.-D.; resources, A.G., E.V.P. and P.F.-G.; data curation, J.B. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.-R.; writing—review and editing, E.M.-R.; visualization, P.F., R.G., E.V.P., J.B. and L.C.-R.; supervision, E.M.-R., P.F.-G., P.F. and G.S.; project administration, Y.A.S.-D. and E.M.-R.; funding acquisition, E.T.C., E.V.P. and P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Vice Presidency for Research through Resolution No. 026-2025-UNIFSLB-CO/VPI, with the support of the Research Institute of the Fabiola Salazar Leguía National Intercultural University of Bagua (UNIFSLB).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the raw data is available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Samrot, A.V.; Wilson, S.; Singh, R.; Preeth, S.; Prakash, P.; Sathiyasree, M.; Saigeetha, S.; Shobana, N.; Pachiyappan, S. Sources of Antibiotic Contamination in Wastewater and Approaches to Their Removal—An Overview. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwecińska, L. Antimicrobials and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria: A Risk to the Environment and to Public Health. Water 2020, 12, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, F.; Martínez, J.L.; Cantón, R. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Flach, C.F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi, J.; Ojewole, C.O.; Ojewole, A.E.; Nwi-Mozu, I. Antimicrobial Resistance Development Pathways in Surface Waters and Public Health Implications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barathan, M.; Ng, S.L.; Lokanathan, Y.; Ng, M.H.; Law, J.X. Unseen Weapons: Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles and the Spread of Antibiotic Resistance in Aquatic Environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misman, N.A.; Sharif, M.F.; Chowdhury, A.J.K.; Azizan, N.H. Water pollution and the assessment of water quality parameters: A review. Desalination Water Treat. 2023, 294, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaynab, M.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Ameen, A.; Sharif, Y.; Ali, L.; Fatima, M.; Khan, K.A.; Li, S. Health and environmental effects of heavy metals. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, A.; Chen, J.-S.; Hussain, B.; Hsu, G.-J.; Rathod, J.; Huang, S.-W.; Wu, C.-C.; Hsu, B.-M. The escalating threat of human-associated infectious bacteria in surface aquatic resources: Insights into prevalence, antibiotic resistance, survival mechanisms, detection, and prevention strategies. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2024, 265, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfadadny, A.; Ragab, R.F.; AlHarbi, M.; Badshah, F.; Ibáñez-Arancibia, E.; Farag, A.; Hendawy, A.O.; De los Ríos-Escalante, P.R.; Aboubakr, M.; Zakai, S.A.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Navigating clinical impacts, current resistance trends, and innovations in breaking therapies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1374466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, A.M.; Yang, Z. Detection and occurrence of indicator organisms and pathogens. Water Environ. Res. 2019, 91, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richiardi, L.; Pignata, C.; Fea, E.; Bonetta, S.; Carraro, E. Are Indicator Microorganisms Predictive of Pathogens in Water? Water 2023, 15, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Fan, L.; Zhang, Y.N. Antibiotic resistance genes in aquatic systems: Sources, transmission, and risks. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 284, 107392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Nyaruaba, R.; Ita, R.E.; Okon, S.U.; Addey, C.I.; Ebido, C.C.; Opabunmi, A.O.; Okeke, E.S.; Chukwudozie, K.I. Antibiotic resistance in the aquatic environment: Analytical techniques and interactive impact of emerging contaminants. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 96, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, E.A.; Jimenez, Q.J.N. Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics in Aquatic Environments: Origin and Implications for Public Health. Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Publica 2023, 41, e351453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Ramos, F. Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: Current knowledge and alternatives to tackle the problem. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report 2021; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Popoola, B.M.; Adeyemi, O.A.; Samson, O.J. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria in tropical freshwater ecosystems: A review of occurrence, distribution and environmental implications. Microbe 2025, 8, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.R.; Webber, M.A. MarA, RamA, and SoxS as Mediators of the Stress Response: Survival at a Cost. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Moreira, I.; Nunes, O.C.; Manaia, C.M. Bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in water habitats: Searching the links with the human microbiome. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Fan, Y.; Chang, S.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, G.; Sun, X. Characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water sources of the Douhe Reservoir, Tangshan, northern China: The correlation with bacterial communities and environmental factors. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rojas, E. Mixed greywater treatment for irrigation uses. Rev. Ambiente Agua 2020, 15, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Rivadeneira, J.E.; Suarez Chavarry, E.B.; Ramirez, Í.M.; Camacho, W.R.; Calderón, E.V.; Astonitas, R.P.; Acosta, R.C.S.C.; Eli, M.R.; Ventura, H.K.M.; Musayón Díaz, M.P. Generation rate of hospital solid waste from different services: A case study in the province of Bagua, northern Peru. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Zeng, L.; Xu, T.; Sun, S.; Yan, S.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y.; Jia, J.; Dou, T. Antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria: Occurrence spread, and control. J. Basic Microbiol. 2021, 61, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.; Morales, E.; Ticona, E.; Ferró-Gonzales, P.; Oblitas, A.; Ferró-Gonzáles, A.L. Water quality and phenotypic antimicrobial resistance in isolated of E. coli from water for human consumption in Bagua, under One Health approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thal, D.A.; Mettenleiter, T.C. One Health—Key to Adequate Intervention Measures against Zoonotic Risks. Pathogens 2023, 12, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrego, S. Estudio de la Relación Entre la Agricultura, la Conservación Ecológica y la Gastronomía en el Distrito de Frías, Piura. Ph.D. Thesis, Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, Lima, Peru, 2018; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Mesías, B.V. Contaminación de las Agua del Rio Marañón Debido a las Descargas Directas del Centro Poblado el Muyo. Master’s Thesis, National University of Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Peru, 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.unc.edu.pe/handle/20.500.14074/1513 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Franklin, A.M.; Weller, D.L.; Durso, L.M.; Bagley, M.; Davis, B.C.; Frye, J.G.; Grim, C.J.; Ibekwe, A.M.; Jahne, M.A.; Keely, S.P.; et al. A one health approach for monitoring antimicrobial resistance: Developing a national freshwater pilot effort. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1359109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autoridad Nacional del Agua (ANA). Diagnóstico de Problemas y Conflictos en la Gestión de los Recursos Hídricos en la cuenca; Autoridad Nacional del Agua (ANA): Lima, Peru, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gamarra, O.; Barrena, M.; Barboza, E.; Rascón, J.; Corroto, F.; Taramona, L. Fuentes de contaminación estacionales en la cuenca del río Utcubamba, región Amazonas, Perú. Arnoalda 2018, 25, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.J.; Horton, B.K. Sediment provenance signatures of the largest river in the Andes (Marañón River, Peru): Implications for signal propagation in the Amazon drainage system. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2025, 157, 105471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud. Protocolo de monitoreo de la calidad sanitaria de los recursos hídricos superficiales. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- MINAM Aprueban Estandares de Calidad Ambiental (ECA) para Agua y establecen disposiciones complementarias. El Peruano 2017, 6–9. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/dispositivo/NL/1529835-2 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Lucena-Aguilar, G.; Sánchez-López, A.M.; Barberán-Aceituno, C.; Carrillo-Ávila, J.A.; López-Guerrero, J.A.; Aguilar-Quesada, R. DNA Source Selection for Downstream Applications Based on DNA Quality Indicators Analysis. Biopreservation Biobanking 2016, 14, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, K.L. Use of UV methods for measurement of protein and nucleic acid concentrations. BioTechniques 1996, 20, 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Pomati, F.; Miller, K.; Burns, B.P.; Zuccato, E.; Calamari, D.; Neilan, B.A. Novel homologs of the multiple resistance regulator marA in antibiotic-contaminated environments. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4271–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardic, N.; Ozyurt, M.; Sareyyupoglu, B.; Haznedaroglu, T. Investigation of erythromycin and tetracycline resistance genes in methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2005, 26, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Champs, C.; Poirel, L.; Bonnet, R.; Sirot, D.; Chanal, C.; Sirot, J.; Nordmann, P. Prospective survey of β-lactamases produced by ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in a French hospital in 2000. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3031–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périchon, B.; Courvalin, P.; Galimand, M. Transferable resistance to aminoglycosides by methylation of G1405 in 16S rRNA and to hydrophilic fluoroquinolones by QepA-mediated efflux in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappell, A.D.; De Nies, M.S.; Ahuja, N.H.; Ledeboer, N.A.; Newton, R.J.; Hristova, K.R. Detection of multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli in the urban waterways of Milwaukee, WI. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.J.; Mecaskey, R.J.; Nasef, M.; Talton, R.C.; Sharkey, R.E.; Halliday, J.C.; Dunkle, J.A. Shared requirements for key residues in the antibiotic resistance enzymes ErmC and ErmE suggest a common mode of RNA recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17476–17485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, L.; Zembower, T.R. Antimicrobial Resistance. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 30, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes-Parra, S.; Chavero-Guerra, P.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Villanueva-Recillas, S.; Manjarrez-Hernández, A. Antimicrobial Resistance in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Relapses from Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Microb. Drug Resist. 2024, 30, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Lievano, A.P.; Cervantes-Flores, F.; Nava-Torres, A.; Carbajal-Morales, P.J.; Villaseñor-Garcia, L.F.; Zavala-Cerna, M.G. Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Escherichia coli Causing Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINSA-INSN. Guia de Procedimiento: Cuantificación y Evaluación de la Pureza del Ácido. 2023, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/insnsb/normas-legales/4364896-000076-2023-dg-insnsb (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- MINAM. Aprueban Estándares de Calidad Ambiental (ECA) Para Suelo; 011-2017-MINAM; Ministry of the Environment-MINAM: Magdalena del Mar, Peru, 2017; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Aprile, F. Nutrients and water-forest interactions in an Amazon floodplain lake: An ecological approach. Acta Limnol. Bras. 2013, 25, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G.F.; Ordoñez, A.C.G. Tópicos Selectos en Salud Ambiental; Academia Nacional de Medicina (ANM): Lima, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nara, D.; De Sousa, R.; Aparecido, A.; Lajarim, R.; Sergio, P. Science of the Total Environment Electrical conductivity and emerging contaminant as markers of surface freshwater contamination by wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 484, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.; Singh, V.P. The relative impact of toxic heavy metals (THMs) (arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr)(VI), mercury (Hg), and lead (Pb)) on the total environment: An overview. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-naggar, A.; Ahmed, N.; Mosa, A.; Khan, N.; Yousaf, B.; Sharma, A.; Sarkar, B.; Cai, Y.; Chang, S.X. Nickel in soil and water: Sources, biogeochemistry, and remediation using biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostróżka, A.; Chajec, Ł.; Wilczek, G.; Student, S.; Kocot, K.; Homa, J. Toxic effects of nickel on tolerance and regeneration in the freshwater shrimp Neocaridina davidi shrimp Neocaridina davidi. Eur. Zool. J. 2024, 91, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Torres, K. Contaminación Ambiental Cerro de Pasco, Enfoques y Propuestas Pasco—2022. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Daniel Alcides Carrión, Cerro De Pasco, Peru, 2023; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Hipólito, A.; Trigo da Roza, F.; García-Pastor, L.; Vergara, E.; Buendía, A.; García-Seco, T.; Escudero, J.A. The expression of integron arrays is shaped by the translation rate of cassettes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouitcheu Mabeku, L.B.; Eyoum Bille, B.; Tepap Zemnou, C.; Tali Nguefack, L.D.; Leundji, H. Broad spectrum resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolated from gastric biopsies of patients with dyspepsia in Cameroon and efflux-mediated multiresistance detection in MDR isolates. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahayarayan, J.J.; Thiyagarajan, R.; Prathiviraj, R.; Tn, K.; Rajan, K.S.; Manivannan, P.; Balasubramanian, S.; Mohd Zainudin, M.H.; Alodaini, H.A.; Moubayed, N.M.; et al. Comparative genome analysis reveals putative and novel antimicrobial resistance genes common to the nosocomial infection pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 197, 2024–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whangsuk, W.; Dulyayangkul, P.; Loprasert, S.; Dubbs, J.M.; Vattanaviboon, P.; Mongkolsuk, S. Re-sensitization of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and restoration of cephalosporins susceptibility in Enterobacteriaceae by recombinant Esterase B. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 77, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.P. The Convergence of Antibiotic Contamination, Resistance, and Climate Dynamics in Freshwater Ecosystems. Water 2024, 16, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajqi Berisha, N.; Poceva Panovska, A.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z. Antibiotic Resistance and Aquatic Systems: Importance in Public Health. Water 2024, 16, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Warns of Widespread Resistance to Common Antibiotics Worldwide. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/13-10-2025-who-warns-widespread-resistance-common-antibiotics-worldwide (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Upreti, G. Autopoiesis, Organizational Complexity, and Ecosystem Health. In Ecosociocentrism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Malviya, R.; Sharma, R. Prospects for New Antibiotics Discovered through Genome Analysis. Anti-Infect. Agents 2023, 21, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.L. Natural antibiotic resistance and contamination by antibiotic resistance determinants: The two ages in the evolution of resistance to antimicrobials. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 2010–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, L.; Xue, H.; Yang, Z.; Meng, F. Sources, dissemination, and risk assessment of antibiotic resistance in surface waters: A review. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.