Abstract

Bacterial cellulose hydrogels (BCHs) are characterized as exopolysaccharides of glucose polymers consisting of β–1–4–glycosidic linkage with various degrees of polymerization which are synthesized by bacteria. There is a paucity of information on the isolation and characterization of a BCH producer isolate from Nigeria. The study, therefore, aimed to characterize a new Acetobacter species that had previously been confirmed to produce BCH. The BCH-producing isolate was characterized by PCR amplification of the full-length 16S rRNA gene, as well as whole-genome sequencing analysis. The whole-genome sequence of the isolate was determined using the Illumina next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform, with downstream analysis of genomic reads through the metaWRAP pipeline. The BCH producer isolate was identified to be Acetobacter orientalis strain Zaria-B1, based on sequence identity with the reference Acetobacter orientalis strain VVS. Based on its annotated genome, the isolate had an approximate genomic size of 3.1 Mbp, 45 total RNAs, a GC content of 52.5%, 3046 total protein-encoding genes, an N50 of 253,774 bp, and an L50 of 4, as well as 30 contigs. The nucleotide BLAST of the cellulose synthase gene sequence confirmed the bin to be Acetobacter orientalis. The whole-genome characterization alongside the 16S rRNA genotyping confirmed the BCH-producing isolate to be Acetobacter orientalis.

1. Introduction

Cellulose is the most common renewable biopolymer (homopolysaccharide) produced in the biosphere (C6H10O5) and is essentially made up of glucose monomers joined together by β (1–4) glycosidic linkages. It is produced by microorganisms, animals, and plants [1,2]. Bacterial cellulose hydrogel (BCH) is a three-dimensional (3-D) network structure of naturally occurring bacterial cellulose that can absorb and retain large amounts of water. The purification processes for plant-based cellulose, such as logging, debarking, chipping, mechanical pulping, screening, chemical pulping, and bleaching, consume a lot of energy and are not environmentally friendly [3]. By contrast, just a few contaminants, such as cells and/or medium components, are present in the bacterial cellulose (BC) that is formed during fermentation. There is a growing interest in developing fully bio-based cellulosic polymers with excellent properties such as tensile strength and Young’s modulus. BCH has good mechanical properties, positioning it as a choice bioresource for reinforcing agents in composite materials [4]. BCH is devoid of impurities such as lignin, hemicellulose, pectin, wax, and other challenging-to-remove plant components [5].

BCH is suited for the creation of wound dressing materials due to the biocompatibility of its nanofibers and their high water-holding capacity [3]. The biomaterial has been commercialized as high-end products for health, food, high-strength papers, audio speakers, filtration membranes, wound dressing materials, artificial blood vessels, and other biomedical devices due to desirable properties like three-dimensional nanomeric structures; unique physical, mechanical, and thermal properties; and its high purity [6].

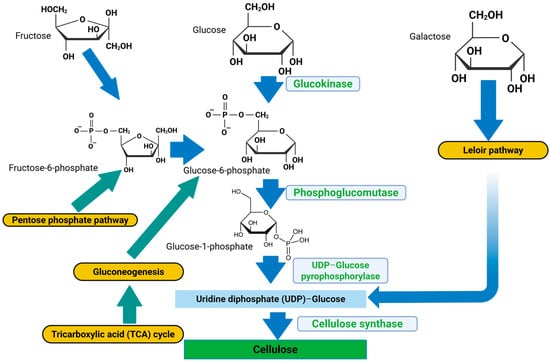

The bacterial cellulose synthesis operon (bcsABCD) encodes the core enzymes responsible for cellulose polymerization and export, as summarized in Figure 1. Gluconacetobacter species use a multi-step metabolic route involving different enzymes, catalytic complexes, and regulatory proteins at each stage for cellulose production [7]. The biosynthetic pathway, assuming glucose is the carbon source, consists of four major enzymatic steps: (i) glucose phosphorylation by glucokinase; (ii) isomerization of glucose-6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) to glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1-P) by phosphoglucomutase; (iii) synthesis of UDP-glucose (UDPGlc) by UDPG pyrophosphorylase (UGPase); and (iv) cellulose synthase reaction. Among all Gluconacetobacter species and other BCH-producing bacterial species, the bacterial cellulose synthesis (bcs) operon encodes the synthesis of cellulose [8]. This operon has four subunits (bcsA, bcsB, bcsC, and bcsD) which are necessary for full BCH synthesis. The catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase is encoded by the first gene of the bcsABCD operon, bcsA. The second messenger that initiates the cellulose synthesis process, cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-di-GMP), is bound by the regulatory subunit of cellulose synthase, which is encoded by the second gene, bcsB [7,9,10].

Figure 1.

Bacterial cellulose hydrogel synthesis pathway. Blue and green arrows = metabolites, yellow boxes = metabolic pathways, light blue boxes = enzymes involved in the respective reactions, sky blue box = rate-determining precursor for cellulose synthesis, green box = cellulose (BCH) (created with Biorender.com (2025); https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/690b04e62cb200a741a44e69, accessed on 3 November 2025).

Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) are a group of bacteria that belong to the family Acetobacteraceae of the class Alphaproteobacteria and are made up of 14 genera. Due to its capacity to produce comparatively large amounts of BCH in liquid culture from a variety of carbon and nitrogen sources, Gluconacetobacter xylinus (previously known as Acetobacter xylinum) is one of the most researched species [11]. Despite extensive studies on bacterial BCH producers, none have been isolated or identified here in Nigeria. Moreover, the Acetobacter orientalis species has not been reported or documented in the literature to produce BCH. Hence, the search for other species of Acetobacter (Gluconacetobacter) that can produce BCH has become imperative. Therefore, the current study aimed to characterize a novel BCH-producing bacterial isolate purified from banana peel agro-residue. Whole-genome sequencing data will provide valuable insight into a comprehensive taxonomy of the study organism, as Sanger’s method of genotyping can be limited by a low sequence identity index with reference sequences, making it difficult for identification to the species or strain level. Additionally, the complete genome sequencing analysis of local strains of Gluconacetobacter [11], as well as characterization of subunit genes in the cellulose-synthesizing operon (acs operon), will serve as genomic data that will provide a viable platform that can be used to understand and modify the phenotype of the bacterial cellulose synthase (bcs) genes to further improve BCH production.

Molecular identification techniques have revolutionized bacterial identification studies, enabling the rapid and accurate identification of certain species. Numerous applications exist for DNA sequencing methods, including the identification of bacterial species and the tracking of the transmission of genes encoding antibiotic resistance. Examples of these uses include Sanger sequencing, NGS, and third-generation sequencing [12]. One method used to ascertain an organism’s entire DNA sequence is whole-genome sequencing (WGS). The method uses high-throughput sequencing to generate a lot of data in a short amount of time. DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis are the steps involved in WGS [13,14].

To identify the most similar biological sequences, the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) takes a query sequence—either a DNA or protein sequence—provided by the researcher and compares it to a library of biological sequences on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database [15]. The BLAST is an algorithm or piece of software used for pairwise sequence (nucleotide or protein) alignment [16]. The extraction and interpretation of high-quality metagenomic bins are greatly enhanced by MetaWRAP, an intuitive, modular pipeline that automates the core tasks in metagenomic analysis. Modern software uses metaWRAP to manage metagenomic data processing, which begins with raw sequence reads and ends with metagenomic bins and their analysis [17,18,19]. The BLASTn was used for our search.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retrieval and Culturing of the BCH-Producing Isolate on Hestrin–Schrann (HS) Media

The bacterial isolate was retrieved from a preliminary study which involved isolation from banana peel agro-residue using the method described by [20]. This was followed by subsequent screening for BCH production using Hestrin–Schramm (HS) media (broth and agar). The HS media had the following components: 2% (w/v) glucose, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) peptone, 0.27% (w/v) Na2HPO4 (disodium hydrogen phosphate), 0.15% (w/v) citric acid, and 1.8% (w/v) agar. In total, 10 mL of the bacterial culture was inoculated into 90 mL of the broth media. The mixture was incubated on a shaker incubator set at 30 °C for 48 h at 150 rpm. The resulting culture was used for the extraction of genomic DNA. For the agar plates, a 100 µL preculture of the isolate was inoculated into the sterile agar plates and spread out using a sterile inoculating loop spreader. The plates were then incubated at 30 °C for 48 h and were observed for colony growth. Colonies from each plate were randomly picked and used for genomic DNA extraction.

2.2. Genomic DNA Extraction from Broth and Agar Cultures

Prior to DNA extraction, 200 µL of the broth culture from each Erlenmeyer flask was aliquoted into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, while samples for DNA extraction from agar plates were scoops of bacterial colony randomly picked from the agar plates and placed into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes containing 200 µL of DNA Elution Buffer using P100 pipette tips. The mixture was vortexed, and the genomic DNA was extracted using the Zymo Research Quick-DNATM Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified DNA was eluted in 50 µL of Elution Buffer. The quality and concentration of extracted DNA were determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dane County, WI, USA) with 1 µL of DNA.

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification of the 16S rRNA Gene

The extracted bacterial DNA was used for PCR amplification of the full-length 16S rRNA gene using generic forward primer 48A (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and reverse primer 48B (5′-TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The PCR mix was prepared to a total reaction volume of 25 µL with the following composition: 9.5 µL of nuclease-free water (NFW), 1 µL (10 µM) of each primer, 12.5 µL of Quick-load 2× Mastermix, and 1 µL of template DNA. A negative control reaction contained NFW in the place of template DNA. The following PCR cycling conditions were used: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 48 °C for 1 min, extension at 68 °C for 1 min, final extension step at 68 °C for 10 min, and storage at 4 °C for ∞. The PCR amplicons were resolved on 1% agarose gel prepared with 1× Tris-acetate buffer (TBE) stained with ethidium bromide and the gel was visualized on a GelDoc system under UV (Ultraviolet) light.

2.4. Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis of PCR Amplicons

The PCR amplicons were sequenced by the Dye terminator method (Sanger’s) with an AB1 XL3500 Genetic Analyzer according to the service provider’s instruction (Inqaba Biotec West Africa, IBWA, Ibadan, Nigeria). In summary, the method entailed preparation of the BigDye mix, preparation of the sequencing reaction, thermal cycling, precipitation reaction (DNA sequencing cleanup), and capillary electrophoresis (actual sequencing).

The AB1 sequencing data contained chromatograms of the individual sequences alongside some ambiguous nucleotide codes. These ambiguous codes were edited using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor v7.2.5. Edited reverse sequences were reverse complemented using the “reverse complement function”. Thereafter, the forward and reverse sequences were aligned using the program “pairwise alignment function”. Finally, a consensus nucleotide sequence representative of the two aligned sequences was generated with the program’s “create consensus sequence algorithm”.

The generated consensus sequence was subjected to the NCBI nucleotide BLAST, and ten (10) sequences from the BLAST hits (output) were selected based on the highest query coverage and percentage identity indexes, as well as the lowest E-values, and downloaded in FASTA format. The 10 sequences with the query consensus sequence were subjected to ClustalW multiple-sequence alignment (MSA) on MEGA11 software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to determine the most recent and closely related ancestry of the isolate. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura–Nei model. A bootstrap value of 1000 was set for the phylogeny. The phylogenetic tree was further edited using the Fig Tree software v1.4.4. The consensus sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of the identified isolate was deposited in the NCBI GenBank Database and was assigned accession number.

2.5. Whole-Genome Sequencing of the Isolate

Purified DNA of the bacterial isolate was sent for whole-genome sequencing analysis (Inqaba Biotec, West Africa, IBWA, Ibadan, Nigeria). The library was prepared as follows: Genomic DNA was fragmented using an enzymatic approach with NEB Ultra II FS kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Resulting DNA fragments were size-selected (200–700 bp) using AMPure XP beads, the fragments were end-repaired, and Illumina-specific adapter sequences were ligated to each fragment. Each sample was individually indexed, and a second size-selection step was performed. Samples were then quantified using a fluorometric method. The samples were diluted to a standard concentration (4 nM) and then sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq500 platform using a NextSeq mid-output kit (300 cycles), following a standard protocol as described by the manufacturer. A 2 × 150 bp paired end read datum was produced for each sample. The library preparation method used can be found at https://www.neb.com/ja-jp/products/next-generation-sequencing-library-preparation/library-preparation-for-illumina (accessed on 24 November 2024).

2.6. Data Analysis of the Whole-Genome Sequence (WGS) Reads Using the metaWRAP Pipeline Modules

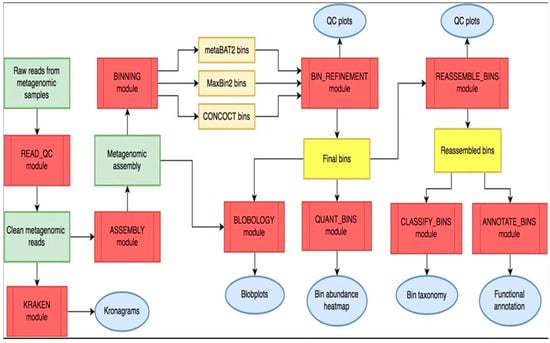

MetaWRAP is an open-source and easy-to-use modular pipeline that automates the core tasks for genomic analysis and can be found at https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP (accessed on 24 November 2024) [18]. An explicit description of the pipeline is presented in Figure 2. After downloading the genomic reads, the metaWRAP-Read_qc module was run to trim the reads and remove human contamination using “bmtagger hg38”. The reads were then assembled with the metaWRAP-Assembly module using the “metaSPADES or MegaHIT” program (version 3.15.5). This was executed following concatenation of the sample reads. To know the taxonomic composition of communities (reads), the “Kraken” module was run on both the reads as well as the assembly. After assembly, the co-assembly was binned with three different algorithms (CONCOCT, MaxBin, and MetaBAT) using the metaWRAP-Binning module [17].

Figure 2.

Overall workflow of metaWRAP pipeline. Modules (red); metagenomic data (green); intermediate (orange) and final bin sets (yellow); and data reports and figures (blue) (Adapted from https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP) (accessed on 24 November 2024).

Next, the concoct, MaxBin, and the MetaBAT bin sets were consolidated into a single, stronger bin set with the metaWRAP Bin-Refinement module. The CheckM database was employed for this module. By default, the minimum completion of 70% and maximum contamination of 5% were deployed by the program. The community (consolidated bin set) and the extracted bins were visualized with the Blobology module. This module was used to project the entire assembly onto a GC vs. Abundance plane and annotate them with taxonomy and bin information. Thereafter, the abundances of the draft genomes (bins) across the sample were determined with the Quant module. Next, the consolidated bin set was reassembled with the Reassemble-bins module.

The Reassemble-bins module collects reads belonging to each bin and then reassembles them separately with a “permissive” and a “strict” algorithm. Only the bins that improved through reassembly were altered in the final set. Thereafter, the taxonomy of each bin was inferred with the Classify-bins module using the Taxator-tk program [21]. For this module, the NCBI_nt and NCBI_tax databases were used. The Classify_bins module used Taxator-tk to accurately assign taxonomy to each contig and then consolidated the results to estimate the taxonomy of the whole bin.

Another important module of the metaWRAP pipeline is the “CLASSIFY_Bin Module”, which is used to assign taxonomic hierarchies to the bin under analysis. First, the contigs (a set of DNA segments or sequences that overlap in a way that provides a contiguous representation of a genomic region) in all bins were combined into one file, and blastn v2.7.1 was used to align the contigs to the NCBI_nt database. The alignment results were then used by taxator-kt v1.3.3e to estimate the taxonomy of each contig. The most likely taxonomy of each bin was then estimated from individual contig predictions. Once no further taxonomic ranking could be estimated, the final taxonomy of the bin was reported (Adapted from https://github.com/bxlab/metaWRAP, accessed on 3 November 2025) [18,22].

There was no doubt the success and accuracy of the predictions would rely heavily on the query cover and percentage sequence identity indexes of the existing database. Finally, the generated bin (bins) was functionally annotated with the Annotate-bins module using the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) online tool [17,18,21]. The annotated bin was then visualized on the SEED viewer online tool.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Identification of the BCH-Producing Isolate by the Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene

3.1.1. Genomic DNA Extraction and Quantification

Concentrations of the extracted genomic DNA were recorded within the standard range of 5–100 ng/µL for genomic DNA, while the purity level was also reported within the expected A260/A280 ratio of 1.80, as shown in Table 1 below. Of the extracted DNA samples, only the PCR amplicon from PLT2 passed the sequencing quality check (QC); this amplicon was successfully sequenced and used for downstream analysis. Additionally, the same genomic material was subjected to whole-genome sequencing.

Table 1.

Bacterial genomic DNAs with their concentrations and purity (A260/A280).

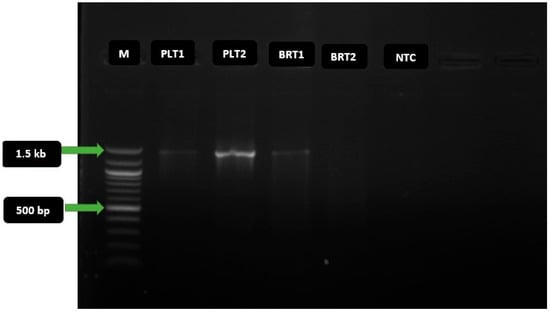

3.1.2. Gel Electrophoresis of the 16S rRNA PCR Amplicons

Four (4) of the extracted genomic DNAs were selected based on the Nanodrop quality check and used for PCR amplification of the full-length 16S rRNA gene, using a combination of agar and broth cultures. Three of the tested DNAs were successfully amplified, as shown by the gel electrophoregram in Figure 3 below. From the gel, amplicon PLT2 had the clearest distinct band and consequently passed the sequencing QC. Nonetheless, amplicons PLT1 and BRT1 also had some distinct bands and were all amplified at the same size (1.5 kbp).

Figure 3.

Gel electrophoregram of 16S rRNA gene PCR amplicons. Key: M = 100 basepair molecular marker; bp = basepair; kb = kilobase; PLT1 and PLT2 = amplicons of extracted genomic DNA from agar plates; BRT1 and BRT2 = amplicons of extracted template DNA from broth cultures; NTC = non-template control. The expected amplicon size of the target taxonomic marker gene is 1.5 kilobasepair (kbp), and the PCR amplicon was amplified at this mark.

3.1.3. Nucleotide BLAST Output with Parameters of the Sequenced 16S rRNA Gene

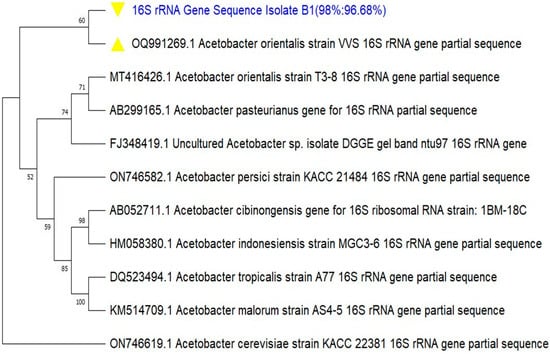

The sequences of the PCR amplicons were analyzed and aligned using the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor v7.2.5. From the BLAST algorithm output, different species of the genus Acetobacter were returned, including orientalis, tropicalis, persici, pasteurianus, cibinongensis, indonesiensis, malorum, and cerevisiae. However, the species orientalis constituted majority of the hits. Based on the BLAST output, the first hit, Acetobacter orientalis strain VVS, isolated in India, had the highest percentage identity of 96.68%, an E-value of 0.0, and a query cover of 98%; these parameters were shared together with the second reference, Uncultured Acetobacter sp. isolate DGGE, although further details for the second reference were not available from this analysis.

3.1.4. Evolutionary Relatedness (Phylogeny) of the BCH-Producing Isolate

The evolutionary relatedness and ancestry of the isolate were predicted from the BLAST output of its 16S rRNA gene sequence as well as its relative positioning on the phylogenetic tree. This finding made possible the accurate prediction of the genus and species identities of the study organism. Furthermore, the constructed phylogenetic tree for the isolate and other reference Acetobacter species placed the query sequence in the same clade with the reference Acetobacter orientalis strain VVS, as indicated with the yellow triangle in Figure 4. This is an obvious indication that the isolate was most closely related to the reference species. Based on the percentage identity shared with this reference species and the evolutionary relatedness as predicted from its positioning in the phylogeny, the BCH-producing isolate was hereby identified as Acetobacter orientalis.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the BCH-producing isolate Zaria-B1. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura–Nei model. A bootstrap value of 1000 was set for the phylogeny.

3.2. Whole-Genome Characterization of the Acetobacter Orientalis Zaria-B1

3.2.1. Completion and Contamination Indexes of Reassembled Bin

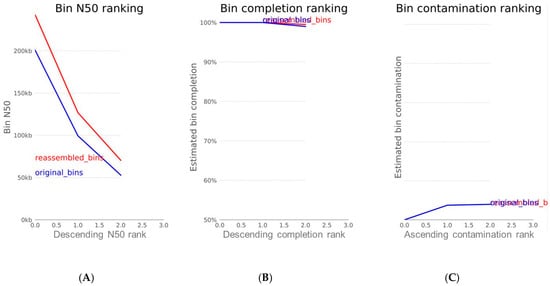

For accurate assessment of the reassembly module, three important indices were used, namely N50, completion, and contamination. N50 statistics define assembly quality in terms of contiguity. The N50 is defined as the sequence length of the shortest contig at 50% of the total assembly length. Based on the chart in Figure 5A, the reassembled bin had an N50 of 253,774 bp. The expected minimum bin completion (-C) was set at 70%, and there was a bin completion of approximately 100% as indicated by the red curve in chart b. While the expected maximum contamination rate (-X) ranged from 5 to 10%, it returned a contamination of about 0.7%, as each bar on chart c stands for a contamination rate of 1%. These three indices are a clear indication that the reassembly module was successful.

Figure 5.

Plots of (A) N50 index; (B) completion percentage; and (C) contamination metric of reassembled bin. The blue curve represents the original genomic bin before reassembly, while the red curve depicts the reassembled bin.

3.2.2. Hierarchical Taxonomic Classification of Bin from the metaWRAP Classify-Bin Module

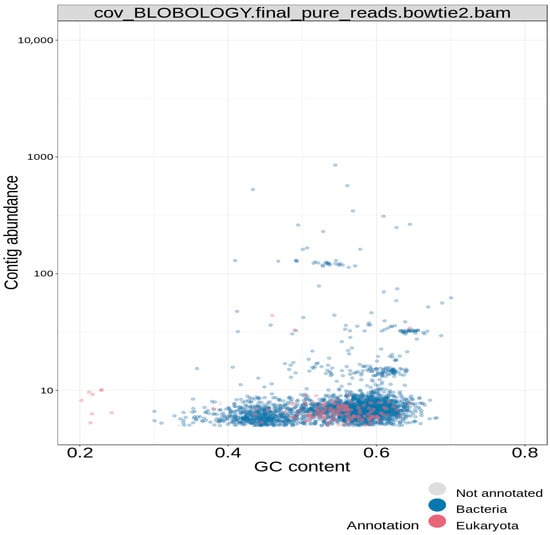

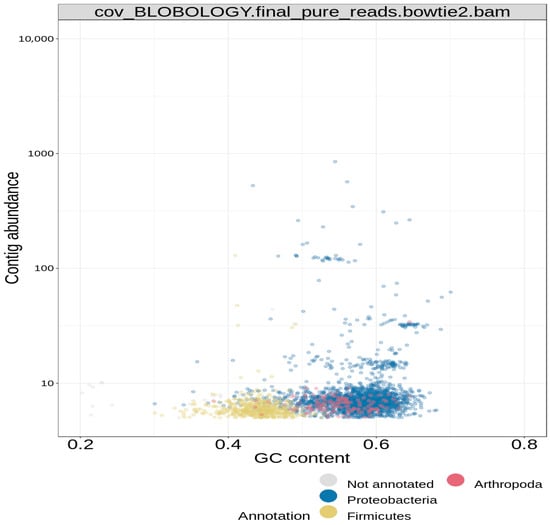

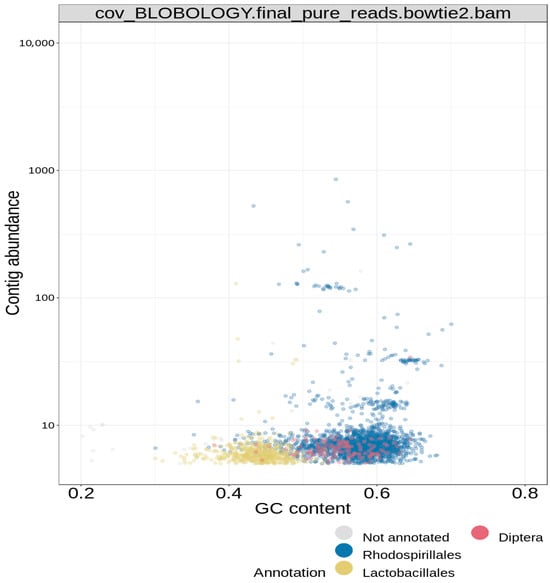

The reported final taxonomy is presented on clustered heatmaps in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. Figure 6 shows that the majority of the scattered dots are colored blue, which was assigned to the super kingdom (domain) taxonomy of bacteria; the other group in this ranking is eukaryote (red) Figure 7 also shows that the majority of the dots are colored blue, which corresponds to a phylum taxonomy of proteobacteria; the other taxonomic groups in this ranking are arthropoda (red) and firmicutes (yellow). Figure 8 gave similar results, in which more than 95% of the dots (corresponding to the different contigs) are colored blue; in this case, the blue color stands for the order taxonomy of rhodospirillales, and the other taxonomic group in this rank is sphingomonadales (red). Additionally, in each of the taxonomic assignments, the blue dots also had the highest contig abundance, as shown on the vertical axes. In summary, the pattern observed in the three above-described figures classifies the study isolate into the domain bacteria; phylum proteobacteria; and order rhodospirillales.

Figure 6.

Blobology clustered heatmap for super kingdom (domain) hierarchical taxonomy.

Figure 7.

Blobology clustered heatmap for phylum hierarchical taxonomy of bin.

Figure 8.

Blobology clustered heatmap for order hierarchical taxonomy of bin.

3.2.3. Genome Annotation Using the metaWRAP Annotate_Bin Module

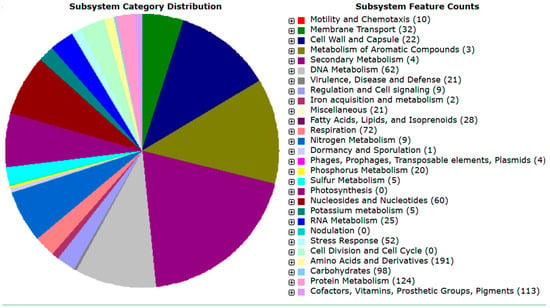

Annotation of the assembled genome was achieved by the metaWRAP “Annotate_BINS module”, using the RAST and the SEED Viewer online tools, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Based on the annotation, the genome size of the isolate was 3,084,067 bp (3.1 Mbp) and it had the following properties: GC content of 52.5%; N50 = 253,774 bp; L50 = 4; number of contigs = 30; number of coding sequences = 3047; and number of RNAs = 45. Figure 9 shows the metabolic orientation of the Acetobacter orientalis Zaria-B1 isolate from the annotated genome. The figure shows genes connected to the subsystem and their category distribution. These are some of the predicted metabolisms of the isolate, alongside their respective number of protein-encoding genes (PEGs) shown in brackets, that translate into gene products that are involved in each metabolic pathway. The Acetobacter orientalis Zaria-B1 was predicted to exhibit both primary and secondary metabolisms, based on its annotated genome.

Figure 9.

Genome map showing critical metabolic pathways of the isolate Zaria-B1.

Furthermore, genome annotation using RAST also presented the taxonomic profile of the isolate as follows: Bacteria; Pseudomonadati; Pseudomonadota; Alphaproteobacteria; Acetobacterales; Acetobacteraceae; Acetobacter; Acetobacter orientalis; Acetobacter orientalis Zaria-B1.

3.2.4. NCBI Nucleotide BLAST of the Cellulose Synthase Gene

The hierarchical taxonomies of the bin from the isolate Zaria-B1 all corresponded to the ones assigned by the NCBI GenBank after submission of its 16S rRNA gene sequence to the database. However, the system could not identify beyond this level of classification, and based on the developer’s instruction, it was recommended to use one of the conserved taxonomic marker genes’ sequences of the target organism from the annotated genome for the nucleotide BLAST for species identification. Therefore, the cellulose synthase catalytic subunit gene was used for the BLAST. Supplementary Figure S3 shows the BLAST output of the query gene sequence, which returned only one hit, which belongs to Acetobacter orientalis, strain FAN1, with a percentage identity of 98.44% and a query cover of 100%. This is an apparent affirmation that the assembled genome belongs to Acetobacter orientalis, in addition to the previous 16S rRNA identification. The gene sequence for the cellulose synthase is the coding sequence, with a start codon ATG and a stop codon TAG at the flanking ends of the sequence (Accession: PP393681). The bcs gene sequence had a length of 4608 bp and an amino acid sequence length of 1536 aa. Following the whole-genome characterization, the cellulose synthase catalytic subunit gene and the beta-1,4-endoglucanase gene sequences of the isolate were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database and were assigned accession numbers PP393681 and PP393682, respectively. The products of the two genes are essential for the functional synthesis of the bacterial cellulose hydrogel (BCH).

4. Discussion

The ultrapure and nanofibrillar structure of BCH differentiates it from plant cellulose. BCH is well known for its strength, flexibility, and high water-holding capacity, reaching up to ~90% of its weight. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that BCH attracts significant attention, and numerous approaches have been pursued for research and development of the biomaterial [23].

Molecular characterization of microorganisms has become necessary to complement other preliminary characterizations (such as microscopic, morphological, and biochemical), which are not sensitive enough to determine the species and strains of target organisms. In this study, molecular techniques were used to characterize a new BCH-producing isolate, identified as Acetobacter orientalis, via PCR amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene and sequencing. Findings from this study are similar to several other studies that have reported the characterizations of several species of the Acetobacteraceae family, using similar techniques. Ref. [24] isolated and characterized a bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) producer from rotten fruits in Malaysia as Gluconacetobacter xylinus; the species Acetobacter orientalis was isolated from Indonesian flowers, fruits, and fermented foods and characterized as the orientalis species [25]. Similarly, [26,27,28] also isolated Acetobacter tropicalis from fermented juice of mango, capable of producing vinegar in Burkina Faso, and a cellulolytic and ligninolytic bacterium Acetobacter orientalis XJC-C from a marine soft coral in China, respectively, and characterized them as the same. All the referenced studies employed PCR amplification [29] of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, sequencing, and construction of phylogenetic trees to ascertain the genus and species of the organisms. In these studies, the amplified 16S rRNA gene amplicon had nucleotide sizes ranging from 1.3 to 1.5 kbp.

The N50 is a statistical index that defines assembly quality in terms of contiguity. Since contigs are ordered according to their length when calculating N50, it can be said that L50 is simply the rank of the contig that outputs the N50 length [21]. Two additional parameters that are used to assess the qualities of a genomic bin are completion and contamination. From Figure 5, the estimated completion of the bin was approximately 100%, while the contamination was found to be 0.7%. Completion refers to the level of coverage of the population genome during assembly and reassembly, while contamination is the amount of sequence that does not belong to this population from another genome [21]. In the metaWRAP reassembly module, the expected minimum completion is 50–70%, while the maximum contamination is 5–10%. These two metrics are usually estimated by counting universal single-copy genes within each bin. The percentage of expected single-copy genes that are found within a bin is interpreted as its completion, while the contamination is calculated from the percentage of single-copy genes that are found in duplicate [21].

Findings from the annotated genome of the study organism showed similarity and variation to works of many other authors [8,11,14,23]. This comparative analysis is presented in Supplementary Table S1. The genomic data provided a taxonomic profile of the BCH-producing isolate to the species level. An interesting report from the annotated genome is about the cellulose synthase catalytic subunit gene, comprising bcsA and bcsB subunits, with a DNA size of 4611 bp encoding 1537 amino acid residues [30]. Another component of the bcs subunit genes, as seen from the annotation, is bcsC coding the beta-1,4-glucanase, with 1080 bp encoding 360 amino acid residues [31]. The bcsC subunit serves as a regulatory component of the bcs genes, which functions in the binding of uridine diphosphate (UDP) to the catalytic subunit bcsA. The presence of the above-mentioned bcs subunit genes is an indication that the bacterial isolate can carry out a functional BCH synthesis. In terms of application, data from the annotated genome will provide additional information on the genomic composition and profiles of BCH-producing bacteria, as such data are limited in the database [32,33]. Furthermore, the genomic data could be used for downstream optimization of BCH yield through recombinant DNA technology.

The NCBI nucleotide BLAST output for the cellulose synthase catalytic gene retrieved from the annotated genome of the isolate is presented in Supplementary Figure S3. This BLAST was essential as the metaWRAP pipeline program could only classify the reassembled bin to the order level of taxonomy. Hence, the BLAST result for the cellulose synthase gene returned only one hit, which corresponded to the Acetobacter orientalis strain FAN1 cellulose synthase gene, with a query cover of 100%, percentage identity of 98.44%, and an E-value of 0.0. Based on this observation and the taxonomy assigned to the isolate by the NCBI GenBank database, the BCH producer isolate was confirmed to be Acetobacter orientalis.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully identified and characterized a new BCH-producing Gluconacetobacter orientalis strain, Zaria-B1, based on the bacterial 16S rRNA genotyping, sequencing, and phylogeny. The whole-genome sequence of the isolate was analyzed and annotated with both functional and hypothetical proteins. This is the first report of Acetobacter orientalis producing BCH. Additionally, this is the first study to successfully identify and characterize a BCH-producing bacterium here in Nigeria, and the whole-genome sequence of the isolate Zaria-B1 is one of the few available data globally. Herein, we present a new BCH-producing bacterial isolate whose BCH yield could be optimized for industrial-scale use, using specialized bioreactors. The wound dressing potential of the BCH product has also been tested by another researcher (unpublished). Gene sequences of the isolate have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database with accession numbers OR835989, PP393681, and PP393682. A major limitation of the study reflects the fact that further structural and functional characterization of the bcs subunit genes found in the genome of the isolate could not be determined. Additionally, due to the timeframe of the study and financial constraint, there is a clear gap in studying the cellulose synthase genes for probable recombinant production of BCH in another fast-growing bacterial host [34]. It is therefore recommended that predicted hypothetical proteins from the annotated genome of the isolate should be explored to predict their structure and functions and to investigate if its cellulose synthase genes are expressed in another fast-growing bacterial hosts such as Escherichia coli for enhanced recombinant production of the biomaterial, using recombinant DNA technology as have previously demonstrated [35,36,37].

6. Patents

The research output from this study had been successfully patented through a Germany-based IP filling company, Ideas2ipr, with patent model no. 20 2024 102 959. The patent certificate can be found in the Supplementary Materials, Figure S1.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010005/s1, Figure S1: Certificate of Patent. Figure S2: The Seed viewer homepage showing the annotated genome with various parameters generated (Domain, Taxonomy, Size, GC Content, N50, L50, Number of contigs, Number of subsystems, Number of coding sequences, and Number of RNAs). Figure S3: NCBI Nucleotide BLAST Output of the Cellulose Synthase Catalytic Subunit Gene Sequence. NCBI nucleotide BLAST output of the cellulose synthase gene retrieved from the annotated genome. The BLAST returned only one hit, the Acetobacter orientalis cellulose synthase catalytic gene, with a query cover of 100%, E-value of 0.0 and percentage identity of 98.44%. Table S1. Comparative genomic analyses of Gluconacetobacter species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I.; methodology, S.C.O.; software, S.C.O.; validation, S.C.O., L.J., B.Y.L. and I.Z.W.; formal analysis, S.C.O., O.A.A., G.J. and R.B.M.; investigation, E.O.B.; resources, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I.; data curation, S.C.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.O.; writing—review and editing, O.A.A., G.J., E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I.; visualization, S.C.O.; supervision, E.O.B., Y.K.E.I., A.A.S., M.N.S., A.B.S., T.T.M. and S.H.M.; project administration, S.C.O.; funding acquisition, E.O.B. and Y.K.E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Funds (NRF) under the Tertiary Education Trust Funds (TETFUND), Nigeria. The grant was released under grant number TETF/DR&D-CE/NRF/2020/SETI/572/VOL.1. However, the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. Deposited sequence data in the GenBank repository can be accessed on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database with accession numbers OR835989, PP393681, and PP393682.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the NRF TETFUND Grant, which has made the successful execution of the study possible. Utmost acknowledgement also goes to the Africa Center of Excellence for Neglected Tropical Diseases and Forensic Biotechnology (ACENTDFB) for providing the required facility for the wet lab, as well as funding. We also acknowledge and thank Youssouf Mouliom Mfopit of the Institute of Agricultural Research for Development (IRAD), Yaounde, Cameroon, for establishing the connection for analysis of the metagenomic reads generated from the NGS Illumina sequencing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCH | Bacterial cellulose hydrogel |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| WGS | Whole-genome sequencing |

References

- Castro, C.; Zuluaga, R.; Álvarez, C.; Putaux, J.L.; Caro, G.; Rojas, O.J.; Mondragon, I.; Gañán, P. Bacterial Cellulose Produced by a New Acid-resistant Strain of Gluconacetobacter Genus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Hu, S. “Smart” Materials Based on Cellulose: A Review of the Preparations, Properties, and Applications. Materials 2013, 6, 738–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizem, B.; Athanasios, M. Systematic Understanding of Recent Developments in Bacterial Cellulose Biosynthesis at Genetic, Bioprocess and Product Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, O.; Panesar, P.S.; Chopra, H.K. Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose Producing Bacterial Isolate from Rotten Grapes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 2017, 14, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelenko, K.; Cepec, E.; Nascimento, F.X.; Trček, J. Comparative genomics and phenotypic characterization of Gluconacetobacter entanii, a highly acetic acid-tolerant bacterium from vinegars. Foods 2023, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, J.B.; Deng, Y.; Nagachar, N.; Kao, T.; Tien, M. Acsa–Acsb: The core of the cellulose synthase complex from Gluconacetobacter hansenii ATCC23769. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2016, 82, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cao, Y.; Qu, R.; Gao, G.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, M.; Ma, T.; Li, G. Production of bacterial cellulose hydrogels with tailored crystallinity from Enterobacter Sp. FY-07 by the controlled expression of colanic acid synthetic genes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illeghems, K.; De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of Acetobacter pasteurianus 386B, a strain well-adapted to the cocoa bean fermentation ecosystem. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K.; Tsai, M.; Chen, C.; Di Dong, C. Genetic modification for enhancing bacterial cellulose production and its applications. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 6793–6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abhay, P.; Rakesh, K. A Review on Production, Characterization and Application of Bacterial Cellulose and Its Biocomposites. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 2738–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lingpu, L.; Shiru, J.; Siqi, L.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, Z. Complete Genome Analysis of Gluconacetobacter xylinus CGMCC 2955 for Elucidating Bacterial Cellulose Biosynthesis and Metabolic Regulation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulateef, A.S.; Owaif, H.A.; Hadi, N.A. Molecular Identification Techniques of Bacteria: A Review. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4, 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Cleenwerck, I. Improved Classification and Identification of Acetic Acid Bacteria Based on Molecular Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Gent Universiteit, Ghent, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Gao, H.; Liao, B.; Wu, J.; Zhang, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, M.; Huang, J.; Chang, Z.; Jin, M.; et al. Characterization and optimization of production of bacterial cellulose from strain CGMCC 17276 based on whole-genome analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 232, 115788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, K.C.; Sahoo, J.P.; Behera, L.; Dash, T. Understanding the BLAST (Basic local alignment search tool) program and a step-by-step guide for its use in life science research. Bhartiya Krishi Anusandhan Patrika 2021, 36, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staton, J.L. Understanding Phylogenies: Constructing and Interpreting Phylogenetic Trees. J. S. Carol. Acad. Sci. 2015, 13, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystem Technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, R.; Olson, R.; Pusch, G.D.; Olsen, G.J.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Parrello, B.; Shukla, M.; et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotations of Microbial Genomes using Subsystem Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 42, D206–D214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swingler, S.; Gupta, A.; Gibson, H.; Kowalczuk, M.; Heaselgrave, W.; Radecka, I. Recent Advances and Applications of Bacterial Cellulose in Biomedicine. Polymers 2021, 13, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revin, V.; Liyaskina, E.; Nazarkina, M.; Bogatyreva, A.; Shchankin, M. Cost-effective production of bacterial cellulose using acidic food industry by-products. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49S, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uritskiy, G.V.; DiRuggiero, J.; Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—A Flexible Pipeline for Genome-Resolved Metagenomic Data Analysis. Microbiome 2018, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizem, B.; Alexander, B.; Athanasios, M. Recombinant Biosynthesis of Bacterial Cellulose in Genetically Modified Escherichia coli. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 41, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, N.; Tamura, T. Whole-genome sequence of Acetobacter orientalis strain FAN1, isolated from Caucasian yogurt. Genome Announc. 2018, 6, e00201-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abba, M.; Abdullahi, M.; Md Nor, M.H.; Chong, C.S.; Ibrahim, Z. Isolation and characterisation of locally isolated Gluconacetobacter xylinus BCZM Sp. with nanocellulose producing potentials. IET Nanobiotechnology 2017, 12, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdiyanti, P.; Kawasaki, H.; Seki, T.; Yamada, Y.; Uchimura, T.; Komagata, K. Identification of Acetobacter strains isolated from Indonesian sources, and proposals of Acetobacter syzygii Sp. Nov., Acetobacter cibinongensis Sp. Nov., and Acetobacter orientalis Sp. Nov. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 47, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assiètta, O.; Somda, M.K.; Ouattara, A.T.C.; Bassirou, N.; Alfred, T.; Ouattara, S.A. Molecular identification of acetic acid bacteria isolated from fermented mango juices of Burkina Faso: 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, D.; Cai, B.; Zhang, M.; Qi, D.; Jing, T.; Zang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xie, J. Acetobacter orientalis XJC-C with a high lignocellulosic biomass-degrading ability improves significantly composting efficiency of banana residues by increasing metabolic activity and functional diversity of bacterial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 324, 124661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Deresawi, T.S.; Mohammed, M.K.; Khudhair, S.H. Isolation, Screening, and Identification of Local Bacterial Isolates Producing Bio-Cellulose. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 2022, 6, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N. DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction. J. Cytol. 2019, 36, 116–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryu, T.; Kiso, T.; Nakano, H.; Ooe, K.; Kimura, T.; Murakami, H. Involvement of Acetobacter orientalis in the production of lactobionic acid in Caucasian yogurt (“Caspian Sea yogurt”) in Japan. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, I.M.; Krystyna, K.; Kazuo, O.; Brown, R.M., Jr. Characterization of Genes in the Cellulose-synthesizing Operon (acs Operon) of Acetobacter xylinum: Implications for Cellulose Crystallization. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 5735–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, J.D.; Vilcinskas, A. Genome analysis suggests the bacterial family Acetobacteraceae is a source of undiscovered specialized metabolites. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2021, 115, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsutani, M.; Hirakawa, H.; Yakushi, T.; Matsushita, K. Genome-wide phylogenetic analysis of Gluconobacter, Acetobacter, and Gluconacetobacter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 315, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Janabi, S.S.; Shawky, H.; El-Waseif, A.A.; Farrag, A.A.; Abdelghany, T.M.; El-Ghwas, D.E. Stable, efficient, and cost-effective system for the biosynthesis of recombinant bacterial cellulose in Escherichia coli DH5α platform. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogun, E.O.; Inaoka, D.K.; Kido, Y.; Shiba, T.; Nara, T.; Aoki, T.; Honma, T.; Tanaka, A.; Inoue, M.; Matsuoka, S.; et al. Overproduction, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense glycerol kinase. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2010, 66, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, E.O.; Inaoka, D.K.; Shiba, T.; Kido, Y.; Nara, T.; Aoki, T.; Honma, T.; Tanaka, A.; Inoue, M.; Matsuoka, S.; et al. Biochemical characterization of highly active Trypanosoma brucei gambiense glycerol kinase, a promising drug target. J. Biochem. 2013, 154, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Inaoka, D.K.; Shiba, T.; Balogun, E.O.; Allmann, S.; Watanabe, Y.I.; Boshart, M.; Kita, K.; Harada, S. Expression, purification, and crystallization of type 1 isocitrate dehydrogenase from Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 138, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.