Abstract

Surfactants are harmful, persistent pollutants that are often found in contaminated soils, wastewater, and industrial effluents in complex mixes. Due to their chemical diversity and persistence, they present a bioremediation challenge. Using long-read shotgun metagenomics, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, PICRUSt2 functional prediction, and physicochemical proxies (total organic carbon, dissolved oxygen, chemical oxygen demand, foaming activity, etc.), this study investigated the aerobic biodegradation of SDS, SLS, rhamnolipids, Triton X-100, and CTAB (individually/mixed, 4% w/v) by microbial consortia enriched from oil-contaminated soil for 14 days. Pseudomonadota was dominant (85–90%), with Pseudomonas (60%) driving SLS and SDS degradation, while Paraburkholderia and Bordetella were dominant in recalcitrant surfactant degradation. Among the surfactants, SLS, rhamnolipids, and the combination of all surfactants demonstrated higher degradation by virtue of total organic carbon reductions of 50%, 56%, and 50%, respectively, and a foaming activity decline of 45–64%. The combination of surfactants with CTAB showed a 21% reduction in TOC, most likely due to CTAB’s known bactericidal effects. PICRUSt2 showed differential enrichment in alkyl oxidation, sulfate ester hydrolysis, aromatic ring cleavage, and fatty acid/sulfur genes and pathways. This study establishes inexpensive, scalable proxy indicators for monitoring surfactant bioremediation when direct metabolite analysis is impractical.

1. Introduction

Surfactants are substances that are known to reduce tension between two phases, such as two liquids, a liquid and solid, and a liquid and gas, that are essential to the cosmetic, detergent, and pharmaceutical industries [1,2,3]. Due to the industrial revolution and rising demand in emerging nations, the global surfactant market is expected to reach over USD 58 billion by 2028. However, this increases the environmental burden in the face of a lack of or varying regulatory frameworks, such as the US EPA and EU standards [4,5,6]. Surfactants, classified as cationic, e.g., cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB); anionic, e.g., sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS); non-ionic, e.g., Triton X-100; and biosurfactants, e.g., rhamnolipids, play an important role in industrial processes but present serious ecological challenges [3,7]. Due to their chemical stability, surfactants persist in the environment, causing water pollution, toxicity to fish and plants, reduced dissolved oxygen in aquatic environments, and uncontrollable foaming, among many other detrimental effects [7,8,9,10,11].

Anionic surfactants, such as SDS and SLS, are commonly found in wastewater at concentrations of 1.15 to 10.6 mg/L, with possibly higher levels in industrial effluents [12,13]. Although there is little data available, concentrations of these surfactants in soils near industrial activity can range from 40 to 1000 mg/kg and possibly more [14,15]. In general, drinking water is regulated at lower concentrations: 0.5 mg/L for potable water and 1.0 mg/L for process water in the case of SDS [16]. These surfactants differ in their toxicity, e.g., CTAB, because of its high toxicity, which causes adverse microbiological effects at concentrations over 0.3 mg/L, necessitating mitigation [17]. SDS and SLS have sublethal effects such as oxidative stress at 0.5–1.0 mg/L and acute toxicity to aquatic organisms with 96 h LC50 values of 3.2–30 mg/L [18,19]. Triton X-100 and rhamnolipids are generally considered less harmful, although at high concentrations and in mixes, they can be detrimental to aquatic life [20,21]. The lack of regulation of several surfactants makes it necessary to conduct studies on their chronic effects [22,23].

Surfactants persist in the environment as complex mixes because they are not completely removed during traditional wastewater treatment. The most economical and sustainable method of removing surfactants is considered to be bioremediation, although comparable options such as adsorption, chemical oxidation, and electrochemical coagulation exist [7,24,25]. Studies have revealed several microbial taxa, mostly Pseudomonas, as prominent degraders of surfactants such as SDS and SLS that function by cleaving sulfate ester bonds and via processes such as alkyl chain β-oxidation [26,27,28]. Pure cultures of Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Acinetobacter have been shown to degrade Triton X-100 [29,30]; Pseudomonas and Achromobacter degrade CTAB [31,32], and Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Acinetobacter degrade biosurfactants [33]. Mixed or combinations of surfactants have been used in the treatment of other pollutants (e.g., hydrocarbons, PAHs, and heavy metals) [34,35,36]. However, the actual biodegradation of surfactants like SLS, SDS, Triton X-100, CTAB, and rhamnolipids, particularly at concentrations above 1%, has not been thoroughly studied [17,37,38,39,40]. Due to their potent bactericidal activity, which prevents microbial breakdown and restricts biodegradation, studies at higher doses of cationic surfactants like CTAB are particularly difficult [38,41].

Three crucial knowledge gaps remain despite extensive research on the degradation of single surfactants: (i) microbial community dynamics and functional responses during the degradation of high-concentration (>1% w/v) mixed surfactants, including bactericidal cationic surfactants; (ii) identification of primary versus secondary degraders within natural consortia; (iii) development of low-cost, reliable monitoring proxies when direct metabolite quantification is impractical due to analytical interference or cost; and (iv) identification of key metabolic pathways and functional genes enriched during surfactant biodegradation. This study addresses these gaps by utilizing pre-adapted consortia from two persistently oil-contaminated locations in Gauteng, South Africa. These locations were chosen because of their prolonged exposure to petroleum-derived compounds, which encourages robust microbial communities to degrade individual and mixed surfactants (4% w/v, including CTAB at 1%) in an aerobic environment.

To track biodegradation of surfactants, demonstrate clear successional patterns from primary to secondary degraders, and validate scalable proxy indicators (TOC, pH, COD, OD, ORP, and foaming activity), we combined PacBio long-read shotgun metagenomics, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, PICRUSt2 predictive functional profiling, and low-cost physicochemical and foaming proxies. This study provides insights into a practical framework for monitoring and optimizing field-scale bioremediation of complex surfactant pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Enrichment and DNA Sequencing

A detailed site description and the physicochemical properties of the oil-contaminated soil used in this study are provided in Supplementary Results Tables S1–S4. Briefly, the samples were collected from oil-contaminated soil from Midrand and Roodepoort (Gauteng, South Africa). Midrand soil samples were characterized by acidic conditions (pH 5.49), whereas Roodepoort samples were near neutral (pH 7.5). Total PAH concentrations (Σ 30 PAHs; mainly 5–6-ring compounds like benzo[a]pyrene: 8.500 µg/g) for Midrand’s surface (0–10 cm) and subsurface (10–20 cm) were 24,411 µg/g and 47.1 µg/g, respectively. Roodepoort was characterized by Σ 30 PAHs (mainly 4-ring compounds like pyrene: 5.600 µg/g) of 34.45 µg/g at the surface and 7.82 µg/g at subsurface levels, respectively. Heavy metal levels were quantified at, e.g., Zn (1095 mg/kg), Mn (351 mg/kg), and Cr (108.33 mg/kg) for Midrand, while at Roodepoort, the same heavy metals were 369 mg/kg, 267.33 mg/kg, and 151.67 mg/kg, respectively.

Ten grams of oil-contaminated soil were inoculated into 250 mL Duran Schott bottles containing 250 mL of sterile mineral salt medium (MSM). The individual surfactants were added at 2% w/v (sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS, ≥99% purity, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, ≥99% purity, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), rhamnolipids (≥95%, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), Triton X-100 (≥99% purity, Sigma-Aldrich), or cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, ≥98% purity, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany)) and incubated at 30 °C and 160 rpm using a Model 353 shaking incubator (Labotec, Midrand, South Africa) for 14 days. The enriched cultures were then each centrifuged for 10 min at 5000× g, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 20 mL MSM to create an inoculum. To further enrich the surfactant-degrading microbes, the inoculum was transferred to a new 250 mL MSM bottle containing the same 2% surfactant at w/v and cultured for a further 7 days under the same incubation conditions [42]. To establish the baseline microbial population, the negative controls (MSM with the soil and no surfactant) were also included. Successful enrichment was confirmed by shotgun metagenomics (Supplementary Results Figures S1–S3).

Subsequently, 10 mL of culture was centrifuged and resuspended in dH2O for the genomic DNA extraction using the NucleoSpin soil extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel GMBH & CO., Düren, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The BioDrop spectrophotometer was used to measure the purity at 260/280 nm, and the QUBIT fluorometer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to quantify DNA concentrations. The resulting DNA samples were sequenced at Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd. (Pretoria, South Africa) for whole-genome shotgun metagenomics sequencing using a PacBio Revio platform (Menlo Park, CA, USA).

2.2. Shotgun Metagenomics and Statistical Analysis of Enrichment Samples

The Nephele (cloud-based analysis platform) from NCBI was used to process PacBio long-read data from the 21-day enriched soil microbiome samples. Using PacBio CCS, the high-fidelity (HiFi) reads were generated, and the adapter and low-quality sequences were removed using HiFiAdapterFilt [43,44]. Before analysis, the reads were sorted by length and quality [45]. To illuminate the environmental contamination or potential host, the sequences were mapped against reference genomes using pbmm2, which were further screened using k-mer [46]. Utilizing DIAMOND alignments, taxonomic categorization was carried out using MEGAN-LR and METAannotatorX2 [47]. The assemblies were created using hifiasm-meta, whereas binning and bin refinement of the contigs into MAGs were carried out using Binette [48]. For functional annotations of genes and pathways, EggNOG-mapper, KEGG, and the functional modules of MEGAN-LR and METannotarX2 were used [49]. All the analyses were carried out in Nephele for reproducible PacBio metagenomic processing. Full results are presented in Supplementary Results S1 and Supplementary Figure S1.

2.3. Degradation Experiments and Physicochemical Analyses

Degradation dynamics of surfactants were studied using 1000 mL bottles containing 900 mL sterile mineral salt medium (MSM), prepared as described previously, supplemented with 4% w/v of surfactants (Rhamnolipid, SLS, SDS, Triton X-100, ALL (combination of 1% Rhamnolipid + 1% SLS + 1% SDS + 1% Triton X-100), and ALL + 1% CTAB). Each bottle was inoculated with 10 mL of enriched microbial culture and incubated at 30 °C with orbital shaking at 150 rpm in a Model 353 Incubator (Labotec, South Africa) for 14 days. Triplicate bottles were prepared for each surfactant condition. The readings were taken after 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 5 days, 8 days, and 14 days. Physicochemical characteristics measurements for pH, oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), and dissolved oxygen (DO) were carried out using an H19829 HANNA multiparameter meter (HANNA Instruments, Johannesburg, South Africa). Chemical oxygen demand (COD) was measured using a Lovibond MD160 photometer (Tintometer, Dortmund, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The total organic carbon (TOC) was determined at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) (South Africa) using an Analytik Jena Multi NC3100 (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany) according to standard procedures. All the measurements were performed in triplicate, and results were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Since the study focused on relative changes rather than absolute quantification, validated commercial equipment (Analytik Jena Multi NC3100) was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s protocols; therefore, no external standards were used.

2.4. Foaming Activity and Stability Measurements

The foaming activity was assessed on days 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and 14 by transferring 4 mL of the supernatant to 15 mL graduated centrifuge tubes. The tubes were vigorously shaken by hand for 30 s, and the foam volume was measured immediately using the tube graduations. Despite its simplicity, this method was chosen for its scalability and has been shown to be reliable for relative comparisons in previous studies.

Foaming stability was calculated as

where Vt is the foam volume after 1 h, and V0 is the initial foam volume immediately after shaking [50,51]. Measurements were performed in triplicate, with results reported as mean ± standard deviation.

(Vt/V0) × 100%,

2.5. Microbial Community Structure, Functional Abundance Predictions (PICRUSt)

To study the microbial community structure, DNA was extracted, and 16S rRNA sequencing was performed at Inqaba Biotechnical Industries Pty (Ltd.) (Pretoria, South Africa), using the PacBio sequencing platform. The raw FASTQ files obtained from sequencing were processed using the preprocessing QC pipeline in the Nephele platform (v2.0, accessed on 9 July 2025) utilizing FastQC (v0.11.9) for quality assessment and Trimmomatic (v0.39) for adapter trimming and quality filtering (Phred score lower than 20) [52]. For microbial abundance insights, Nephele’s DADA2 pipeline (v1.16) was used to perform denoising, chimera removal, and clustering of similar sequences into amplicon sequence variants (ASV) against the SILVA v138 database at 97% identity [53,54]. The amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated, and relative abundances were calculated at the phylum, genus, and species levels. To assess the metabolic potential of microbial communities found across the 14 days of degradation, 16S rRNA sequence reads were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The OUT table in BIOM format obtained from the analysis above was used to predict metabolic function using PICRUSt2 on Nephele’s Microbiome Analysis. The pipeline output was therefore visualized using STAMP software.

Predicted functional profiles (KEGG Orthologs [KO], Enzyme Commission numbers [EC], and metabolic pathways) were obtained from PICRUSt2 outputs using unstratified tables with descriptive annotations. Features with zero abundance across all samples were excluded. For each functional category (KO, EC, and pathways), the top 10 significantly different features across treatment points were identified using the Kruskal–Wallis test, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Boxplots with overlaid jittered points were generated to visualize temporal trends in feature abundance using R (v4.3.0) with the ggplot2 (v3.4.0), dplyr (v1.0.10), tidyr (v1.2.0), and tidyverse (v1.3.2) packages. Each panel in the faceted plot represents one of the top features with its corresponding abundance distribution across treatment points [55].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surfactant-Specific Selection of Microbial Consortia

The 21-day enrichment of the consortia from oil-contaminated soil revealed a specialized consortia that was mainly dominated by the phylum Pseudomonadota (85–95%) in relative abundance. Pseudomonas dominated in SLS and SDS enrichments at 60.2% and 40.5%, respectively. Achromobacter became the most enriched in rhamnolipids at 20.1%, whereas Stutzerimonas at 15.3% dominated Triton X-100 treatments. The enrichment with 2% w/v CTAB alone did not allow for growth, confirming its known bactericidal property. Functional profiling of the community after enrichment via KEGG pathway annotations showed that metabolic pathways were predominant across all samples, with a significant level linked to biodegradation and metabolism of xenobiotics, in line with oil-contaminated soil and exposure to surfactants. Statistically enriched pathways (Kruskal–Wallis p < 0.05) confirmed the shift from general microbial consortia to a more specialized surfactant-degrading consortia via the upregulation of xenobiotic (surfactant)-induced pathways in comparison to the control. The detailed results are provided in Supplementary Results; Figures S1–S3. The resulting consortia were used as an inoculum for the subsequent degradation studies.

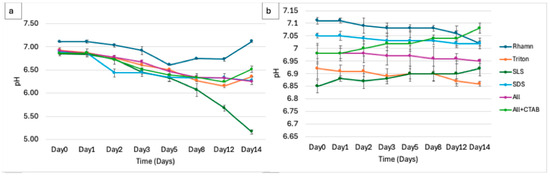

3.2. Physicochemical Dynamics Indicate Biodegradation

The experiments on the physicochemical parameters tracked over 14 days (4% w/v) surfactant provided important insights into the redox and metabolic dynamics of surfactant breakdown by microbial consortia. The pH dropped in the flasks with each treatment, highlighting that microbial metabolism of surfactants in this study produces acidic byproducts, as shown in Figure 1a. The control experiment in Figure 1b did not show any significant changes in pH over the course of 14 days. For example, SLS showed the most noticeable decline, decreasing from an initial pH of 6.85 to 5.68 by day 14, suggesting possibly a greater degradation and acid production. Showing a more dynamic pH trend, rhamnolipids dropped from 7.11 to 6.61 by day 5 before rising back to around 7.11 by day 14, suggesting a buffering ability that may be related to its biosurfactant properties. A mixture of ALL, SDS, and Triton X-100 showed a consistent decrease: Triton X-100 declined from 6.92 to 6.35, SDS went from 7.05 to 6.24, and ALL from 6.98 to 6.42. On the other hand, ALL + CTAB decreased more gradually, reaching 6.33 on day 8 and increasing to 6.51 by day 14, likely due to the presence of CTAB, which is known to exhibit an inhibitory effect on microbes.

Figure 1.

(a) Variation in pH over 14 days during microbial degradation of individual surfactants (Rhamnolipids, Triton X-100, SLS, SDS), combined mixture (ALL), and ALL + CTAB. (b) The change in pH for controls (surfactants without microbial consortia).

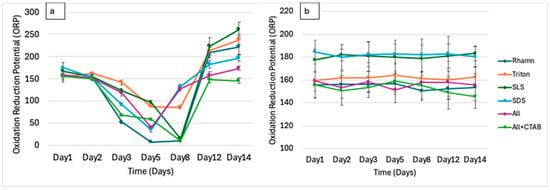

Oxidation–Reduction Potential (ORP) trends (in Figure 2) for all treatments initially showed a decline because of microbial activity, inducing reducing conditions. Rhamnolipids showed a notable decline from 155.25 ORP on day 1 to 7.6 ORP by day 5, possibly resulting from high microbial metabolism, followed by recovery to 209 ORP by day 14, indicative of redox stabilization. SLS decreased from 167.26 ORP to 97.02 ORP by Day 5, reaching 223 ORP by Day 14, whereas Triton X-100 declined from 154.73 ORP to 87.75 ORP by Day 5, rising to 213 ORP by Day 14, while SDS dropped from 160.15 ORP to 35.48 ORP by Day 5 and increased to 223 ORP by Day 14. A combination of ALL showed a drop from 155.6 ORP to 40.17 by day 5, which increased to 156 ORP by day 14. The ALL + CTAB combination was associated with a decline in ORP from 155.6 to 58.82 by day 5, which then increased to 149 ORP by day 14.

Figure 2.

(a) Oxidation–reduction potential (ORP) monitored over 14 days during microbial treatment of each surfactant. (b) The change in ORP for the controls for the same period.

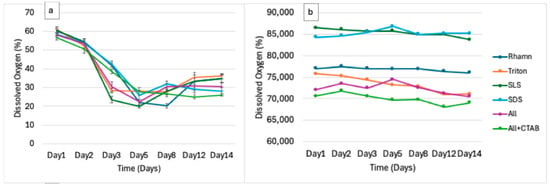

From day 1, dissolved oxygen concentrations, expressed as a percentage (Figure 3), showed a decline across all the treatments because of microbial oxygen consumption during aerobic degradation. By day 5, the lowest oxygen levels were measured, followed by partial recovery by day 14. For instance, rhamnolipid and SLS treatment experienced the steepest declines in dissolved oxygen, from 60.01% at day 1 to 22.1% by day 5 and from 60.51% at day 1 to 19.78% by day 5, respectively. This indicated high microbial activity or biodegradability and was followed by a subsequent stabilization. ALL + CTAB showed a steadier, gentle decline (56.62% to 27.73%); however, on day 14, a further decline to 25.51% was observed, perhaps because of CTAB’s inhibitory impact. While SDS dropped from 58.27% to 25.84% by day 5 and had a partial recovery of 29.18% by day 14, Triton X-100 fell from 60.78% to 28.17% by day 5 before it reached 36.05% by day 14.

Figure 3.

(a) Dissolved oxygen (DO) trends over 14 days and individual surfactants. (b) Dissolved oxygen (DO) of controls (surfactant without microbial consortia) over the same period.

The notable general trend for COD in all treatments showed an initial increase likely due to the formation of oxidizable intermediates, followed by stabilization or a slight decrease, as shown in Figure 4a. No significant changes in COD as a result of abiotic factors were recorded, as illustrated in Figure 4b. Rhamnolipids showed an increase in COD from the initial 0.27 mg/L on Day 1 to peaking at 3.59 mg/L by Day 5, then decreased to 3.17 mg/L by Day 14. While SLS reached 4.02 mg/L on day 5 from 0.68 mg/L on day 1 and stabilized between days 8 and 14. Triton X-100 demonstrated an increase from 0.53 mg/L on day 1 to peaking at 3.84 mg/L on day 5 and then declining to 2.265 mg/L by day 14. SDS increased from 0.12 mg/L to 3.805 mg/L by day 3 and stabilized thereafter, while the combination of all increased from 0.62 mg/L to stabilization around 3.21 mg/L from day 5. ALL + CTAB exhibited the most dynamic shift, rising from 0.27 mg/L to peaking at 3.84 mg/L on Day 5, then declining to 0.66 mg/L by Day 14, likely due to microbial adaptation to CTAB’s presence.

Figure 4.

(a) The change in chemical oxygen demand during the microbial degradation of different surfactants. (b) The change in COD of controls (surfactant without microbial consortia) over 14 days.

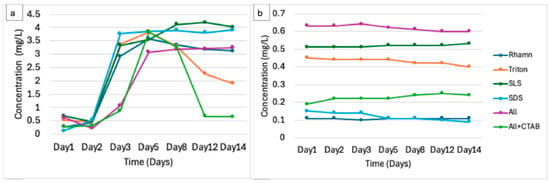

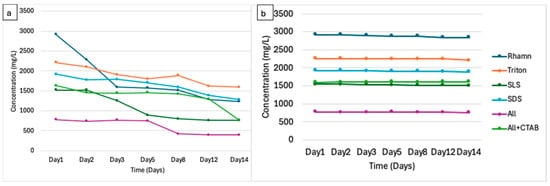

All treatments revealed a drop in TOC levels (see Figure 5a), suggesting mineralization of organic carbon as revealed in several other studies [56,57,58]. Rhamnolipids demonstrated a 56% decline from 2910 mg/L on day 1 to 1529 mg/L on day 14. SLS saw a 50% decrease (1520–757 mg/L) from day 1 to 14. SDS showed a 28.1% drop (1913 mg/L to 1382 mg/L), and Triton X-100 declined 27% (2210 mg/L to 1615 mg/L) within 14 days of treatment. The TOC of the combination of ALL surfactants decreased by 50% (1630 mg/L to 765 mg/L), whereas the combination of ALL + CTAB showed a decrease of 21% (1630–1293 mg/L) over the same treatment period. These reductions in TOC demonstrate the biodegradability of these surfactants under the study’s conditions, with rhamnolipids, SLS, and the combination (ALL) showing potentially higher mineralization rates, suggesting more efficient degradation compared to the rest of the treatments. No significant reductions in TOC without microbial treatment were identified, as shown in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

(a) Total organic carbon (TOC) reduction over 14 days by microbial treatment for each surfactant treatment. (b) Total organic carbon reduction of the control (surfactant without microbial consortia).

Overall, the observed patterns of physicochemical parameters during the duration of the treatments collectively indicate potentially strong biodegradation: a decline in pH showing the production of acidic intermediates, oxygen consumption, and redox changes reflected by DO and ORP shifts, organic carbon mineralization, and intermediate production highlighted by TOC/COD dynamics. The rapid drop in these parameters during the rhamnolipid, SLS, and ALL treatments indicates high biodegradability, while the ALL + CTAB treatment exhibited the smallest drop, likely due to the inhibitory effect of CTAB, which reduces oxygen demand and microbial activity. These findings are in line with research on aerobic biodegradation, which breaks down surfactants due to microbial metabolism and oxygen availability [59,60]. The shifts in pH are consistent with earlier studies associating surfactant degradation with a drop in pH [60,61,62]. Because of the production of acidic metabolic intermediates, the biodegradation of surfactants frequently results in a significant drop in system pH. The findings of this study are consistent with numerous reports of this acidification, especially for common anionic surfactants like sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) [63,64]. In contrast, in the studies by and Zeng et al. [63] and Staninska-Pięta et al. [65], rhamnolipids have been documented to possess a distinct buffering capacity, which leads to pH recovery during degradation as observed in this current study. This may be due to the inherent chemical properties of rhamnolipids and microbial responses to acid accumulation.

The recovery in ORP and DO after day 5 for most of the treatments suggests substrate depletion or a shift to a less oxygen-demanding phase, which is typical for biodegradation studies [66,67]. These findings have significance to bioremediation, as pointed out by the degradation of SLS, ALL, SDS, Triton X-100, and rhamnolipids, and to a lesser extent ALL + CTAB, as demonstrated by TOC reductions and DO recovery. These changes, particularly the decline in ORP, corroborate that microbial degradation creates reducing environments, with the recovery likely indicating substrate depletion or a shift in microbial community structure [63,68,69,70]. Studies by Zeng et al. [63] Lutosławski et al. [64], and Cheng et al. [71] document a rapid decline in DO and a corresponding shift towards reducing conditions, indicated by a lower oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), as typical indicators of intensive microbial metabolism. As the initial degradation phase ends and metabolic activity stabilizes, these parameters are frequently seen to partially recover. This pattern aligns with the current study’s findings. Additionally, it has been shown that the biodegradability of a surfactant can be connected to the extent of the initial DO depletion. In particular, more biodegradable substances, including sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and rhamnolipids, usually cause a greater initial drop in DO concentration. In accordance with the work by Zeng et al. [63] and Tang et al. [72], this link is directly consistent with the patterns seen in our experimental findings.

The slower degradation in SDS, Triton X-100, and ALL + CTAB emphasizes the necessity of optimizing treatment parameters such as surfactant concentration, pH, and temperature, as well as bioaugmentation with strains that are resistant to CTAB or improved aeration to overcome inhibition [73]. The peak in COD by days 3 and 5 raises the possibility of lingering intermediate compounds that may still require further treatment to accomplish full mineralization [74,75,76].

The significant reductions in COD and TOC of readily biodegradable surfactants have been linked to substantial mineralization. Over typical test periods of 14 to 21 days, reported reductions typically range from 40 to 80%. Consistent with this, studies by Mascoli Junior et al. [77], Zeng et al. [63], and Lacalamita et al. [78] report that biosurfactants and some anionic surfactants like SDS and SLS yield better mineralization rates, as observed in this work. CTAB and Triton X-100, for instance, have been reported to be more recalcitrant. Compared to their anionic or biosurfactant counterparts, their presence can impede microbial metabolism and result in a significantly slower degradation profile, as reported by Zeng et al. [63], Onadeji et al. [79], and Zheng et al. [38]. The observed pattern of initial COD increase followed by decline is corroborated by studies noting intermediate accumulation during surfactant degradation [77,80,81]. Overall, these physicochemical properties highlight microbial activity during the degradation of different surfactants at 4% concentration.

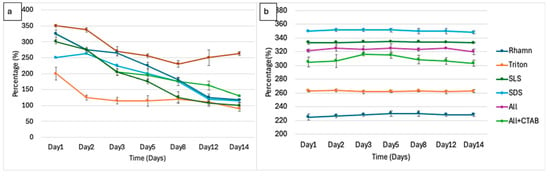

3.3. Foaming Activity and Stability as Direct Degradation Indicators

Over the course of 14 days, the foaming characteristics of surfactant treatments, measured as foaming activity and foaming stability percentages, provide direct proof of the effectiveness of biodegradation. Foaming activity, which measures the capacity of the surfactant to produce foam, declined across most of the treatments, reflecting the loss of functional surfactant molecules, as shown in Figure 6, whereas foam stability measurements are shown in Figure 7. The foaming activity for rhamnolipids significantly reduced from 200% on day 1 to 115% by day 3, to further decline to 110% by day 14, which represented a 45% overall reduction. ALL + CTAB followed a similar pattern, declining from 300% by day 1 of treatment to 205% by day 3 and subsequently falling to 107.5% by day 14, which translates to a 64.2% reduction from its highest foam. Triton X-100 showed an initial increase from 250% on day 1 to 262.5% on day 2 and was then followed by a decline to 120% by day 14, accounting for 54% foam reduction. A steady decline was exhibited by SLS, from 325% on day 1 to 275% on day 2, ultimately reaching 162.5% by day 14, representing a 50% reduction. A mixture of all exhibited a 62% reduction, i.e., 325% on day 1 and 125% by day 14. An interesting observation was noted with SDS, as it displayed a unique trend. A drop from 350% on day 1, followed by a steady decline to 337.5% on day 2, 270% on day 3, and 255.5% on day 5, then an increase from day 8 (230%) to 250% by day 14, suggesting a possible formation of intermediates with foaming abilities or other factors as mentioned in Wang et al. [82].

Figure 6.

(a) Foaming activity measured over 14 days during microbial degradation of each surfactant. (b) Foaming activity in control without microbial inoculum for the same treatment period.

Figure 7.

(a) Foaming stability during microbial degradation of each surfactant over 14 days after the reduction in foaming activity. (b) Foaming stability of surfactants without microbial consortia (control).

The foam stability remained generally stable or showed a slight increase across all treatments. This indicated that the foam integrity was resistant to decay after foaming activity was already reduced, likely as a result of the remainder of surface-active agents and foam stabilizers in the form of intermediates and microbial interaction with the foam [83]. The surface stability of the residual foam of rhamnolipids was 86.67% and 88.63% on day 1 and day 3, respectively, and peaked at 90.65% on day 5. By day 14, they had stabilized at 89.42%. In Triton X-100, the foam stability dropped from 89.59% on day 1 to 87.31% on day 2 and subsequently hit a low on day 5 at 85.97%. The stability then increased by 3% to reach 88.77% by day 14. On day 1, foaming stability for SLS started at 90.11% (most stable) and decreased to 88.66% by day 14. In SDS, foam stability was the highest on day 1 but dropped to 86.07% by day 5 to later stabilize on day 14 at 90.94%. Foam stability in ALL stayed relatively constant, with 88.76% on day 1, 86.51% on day 5, and 87.34% on day 14. After the initial rise from 90.53% on day 1 to 90.88% on day 2, ALL + CTAB dropped to 85.89% on day 8 before increasing to 86.38% on day 14. The trends in foaming-related measurements and physicochemical parameters as a collective give a direct indication of surfactant degradation.

The study’s finding of foaming activity significantly decreasing while foam stability is maintained during a 14-day degradation is well supported by other literature. Studies on rhamnolipids, saponin, and related substances have shown that microbial degradation results in a significant reduction in foaming capacity [84,85,86,87]. The current data (45–65% foam reduction) is consistent with the extent of reduction seen in prior studies. For instance, in a study by Vázquez et al. [84], the foaming activity of saponin was rapidly degraded by microbes, demonstrating that foam loss corresponds with surfactant degradation. Studies by Hollenbach et al. [86] and Arora et al. [88] show that during microbial degradation, SDS and SLS also show a notable reduction (40–60%) in foaming activity over a period of one to two weeks. However, one study reports brief rises or plateaus in foaming (similar to SDS data), which are probably caused by surface-active intermediate byproducts foaming [86]. Due to leftover surfactants and microbial metabolites that can stabilize foam, foam stability frequently stays high or even slightly rises throughout degradation [84,86,87]. Furthermore, Hollenbach et al. [86], Xu et al. [87] and Zhu et al. [83] report that foam stability can also be influenced by pH, the makeup of the microbial community, and the presence of proteins or polysaccharides that stabilize foam. This is consistent with our observations that, despite decreasing foaming activity, foam stability was either steady or slightly increased.

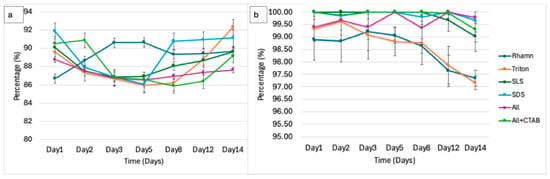

3.4. Microbial Community Distribution During Degradation

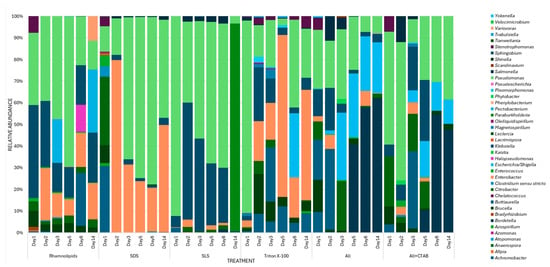

The relative abundance of the bacterial community was analyzed via 16S rRNA sequencing on days 1, 2, 5, 8, and 14 to determine the effects of six surfactant treatments on microbial community structure. These changes revealed microbial adaptation to surfactant types and environmental parameters. The shifts were closely correlated with the observed physicochemical and foaming patterns, revealing information on the microbial roles in surfactant degradation, as depicted in Figure 8 and Figure 9. Tier-4 pathways (Supplementary Figure S3), with the largest differences in mean abundance between surfactant-treated (RHM, SDS, SLS, Triton) and control (CONT) conditions, showed significant upregulation only in the surfactant treatments (and not in the control). Statistically enriched pathways (Kruskal–Wallis p < 0.05) with blue bars indicating higher abundance in surfactant-specific pathways in treatments (positive values) and red bars indicating lower abundance in control (negative values), confirming surfactant-specific microbial distribution. This functional evidence, together with the stability in physicochemical measurements in controls, conclusively demonstrated that succession was driven by the chemistry of surfactants present rather than MSM or other growth conditions. As such, our focus here was on the surfactant-specific microbial distribution.

Figure 8.

Phylum abundance during the 14-day degradation period for surfactants: rhamnolipid, SDS, SLS, Triton X-100, ALL, and ALL + CTAB, showing Pseudomonadota’s dominance and temporal shifts.

Figure 9.

Genus distribution during the 14-day degradation period for surfactants (Rhamnolipid, SDS, SLS, Triton X-100, ALL (Rhamnolipid, SDS, SLS, Triton X-100), and (ALL + CTAB)), showing dominance of Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter across all treatments.

During rhamnolipid treatment, the initial bacterial community varied on day 1 as compared to other days, with Pseudomonas present at 33% and Klebsiella dominating at 42%. The relative abundance of Pseudomonas increased to 69% by day 5, while on day 14, Pseudomonas abundance decreased to 13%, while Pectobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter emerged at 29%, 23%, and 17%, respectively. This suggests that the initial substrate decreased, shifting the microbial population toward secondary degraders (Pectobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter). In the treatment of Triton X-100, the microbial community was dominated by Pseudomonas at 88%, reflecting its initial adaptability to non-ionic surfactants. On day 5, Pseudomonas was overtaken by Enterobacter at 75%. Whereas, on day 8, there was an emergence of Escherichia/Shigella at 30%, and by day 14, Enterobacter was reduced to 51%. Likewise, the initial degradation of SLS was dominated by Pseudomonas at 92% on day 1, whereas on day 2, Klebsiella emerged at 54%. By day 14, the abundance of Paraburkholderia surged to 95%.

Day 1 of SDS treatment/biodegradation was characterized by a diverse microbial community that included 31% of Achromobacter and 31% of Citrobacter. By day 2, Enterobacter emerged as the key driver in the degradation of SDS at 79.68%, while on day 8, Pseudomonas had peaked at 77%, aligning with a 350% to 230% decrease in foaming activity by day 8. However, on day 14, Pseudomonas saw a subsequent decrease to 45%, while Enterobacter re-emerged at 50%, corresponding to a late foaming activity increase to 262.5%. In studying the microbial distribution patterns in the mix (ALL) treatments, the community was mixed, with Pseudomonas at 27% and Buttiauxella at 19% being the most abundant on day 1. By day 14, Bordetella was the most dominant. These findings highlight how Bordetella may adapt to a complex mixture of surfactants, facilitating the breakdown of a wide range of surfactants. Similarly, in ALL + CTAB, Pseudomonas dominated at 52% on day 1, whereas Bordetella’s abundance rose to 55% on day 8 and 47% on day 14. The emergence of Paraburkholderia and Bordetella in CTAB mixtures points to a crucial role in the degradation of toxic intermediates, which allows for the partial recovery of the consortium function despite CTAB inhibition.

The overall shift in community structure over time across all treatments reflects a succession of degraders likely moving from primary to secondary degraders, with Pseudomonas, Buttiauxella, Klebsiella, Achromobacter, and Citrobacter being the primary degraders, whereas Paraburkholderia, Bordetella, Escherichia/Shigella, and Enterobacter are secondary degraders. These microbial community dynamics highlight their potential applications in bioremediation efforts of surfactant-polluted environments. The effectiveness of Pseudomonas in breaking down surfactants lends credence to its potential application in bioaugmentation in locations contaminated with non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Triton X-100). The potential of Paraburkholderia to target recalcitrant anionic surfactants in wastewater, for example, is suggested by SLS breakdown. The ability of Bordetella to adapt in the CTAB in ALL + CTAB may be optimized to promote degradation of cationic surfactants in the environment. However, the potential of Enterobacter to produce SDS degradation intermediates with increased foaming activity points to a drawback necessitating additional microbial strains or optimization of degradation conditions to fully mineralize these byproducts and potentially mitigate foaming.

Recent studies provide strong support for our observations of dynamic shifts in bacterial communities during 14-day surfactant degradation, with primary degraders (like Pseudomonas) initially dominating and secondary degraders (e.g., Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Paraburkholderia, and Bordetella) succeeding. Different microbial successions are driven by surfactant type, concentration, and duration, with Pseudomonas frequently starting degradation and other species developing as substrates and conditions change. According to several studies (Phulpoto et al. [89], Wang et al. [90], and Gill et al. [91]), the addition of rhamnolipid enriches Pseudomonas and other Proteobacteria at an early stage, with subsequent increases in taxa such as Klebsiella, Sphingomonas, and Bacillus as the substrate is exhausted or intermediates build up. This is consistent with our observation that for most surfactants, Pseudomonas dominated at first, followed by Klebsiella, Pectobacterium, and Enterobacter.

A dynamic shift in the microbial composition is often seen in research on surfactant degradation, or the biodegradation of other organic compounds aided by supplementation of surfactants. SLS and Triton X-100 have been shown to initially encourage the growth of Enterobacter and Pseudomonas. However, the community structure usually changes as degradation advances, leading to an increase in the relative abundance of other species such as Stenotrophomonas, Bordetella, and Paraburkholderia. According to Zeng et al. [63], Ling et al. [92], González et al. [93], and Cecotti et al. [94], this successional pattern is a sign of microbial adaptability to changing metabolic intermediates or environmental stress caused by surfactants. Zeng et al. [63] and Gill et al. [91] state that Enterobacter and Pseudomonas replace the early diversity of Achromobacter and Citrobacter in SDS degradation, with late-stage shifts back to Enterobacter or the introduction of additional degraders, which is consistent with our findings. According to Zheng et al. [38] and Mascoli et al. [78], complex or inhibitory surfactants (such as CTAB), as demonstrated by ALL + CTAB treatments, encourage succession towards stress-tolerant or specialized degraders such as Bordetella and Paraburkholderia. Regarding microbial community succession and the roles of primary versus secondary degraders, it has been shown that genera like Pseudomonas frequently serve as initial degraders, making it easier for surfactant substrates to break down. As environmental conditions evolve, a succession to other bacterial genera typically follows. Studies, including those by Phulpoto et al. [89], Wang et al. [90], Gill et al. [91] and González et al. [93], confirm this pattern. Additionally, studies show that a surfactant’s unique structural characteristics and intrinsic toxicity have a significant impact on which secondary degraders take over, highlighting the vital role that dynamic community interactions play in accomplishing successful and comprehensive bioremediation.

To further elucidate/confirm the potential of the microbial consortia to break down surfactants, these dynamic shifts in microbial abundances were mirrored in PICRUSt2 functional predictions by the activation of particular metabolic pathways and enzyme activities (see the following section). The initial abundance in the primary degraders allowed for quick activation of key biodegradation processes, while secondary degraders probably help break down the leftover surfactants and intermediates or any changes activated by primary degraders. Functional predictions complemented by physicochemical analysis highlight the interconnectedness of taxonomic succession and biodegradative capacity, further informing strategies for the effective bioremediation of surfactants in the environment.

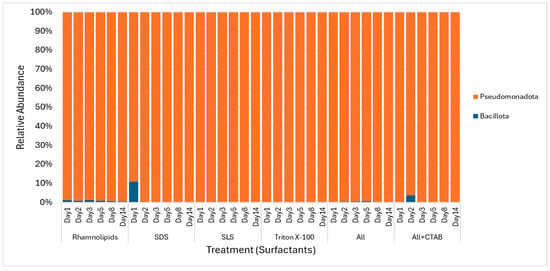

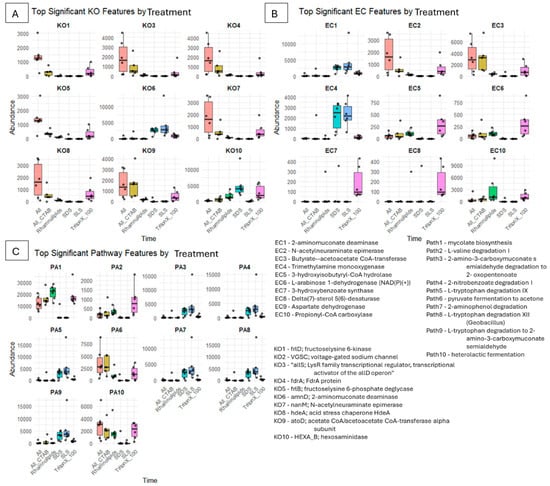

3.5. Microbial Functional Potential and Mechanistic Degradation Insights Using PICRUSt2

To understand functional changes in microbial communities subjected to the surfactants, we performed PICRUSt2 analysis. The PICRUSt2 predictions showed the abundance of important KEGG orthologs (KOs), metabolic pathways, and enzyme commission (EC) numbers across several treatments and time points (shown in Figure 10). With respect to the 10 most significant KO features, different abundance patterns were found based on the treatment. Surfactant types differed significantly in their functional profiles, which were indicative of substrate-specific metabolic processes and adaptation.

Figure 10.

Boxplots illustrating the top significant KEGG Ortholog (KO), Enzyme Commission (EC), and pathway features predicted by PICRUSt analyses across different surfactant treatments and time points. (A) The left panel shows KO features (KO1 to KO10), (B) shows EC features (EC1 to EC10), and (C) presents pathway features (PA1 to PA10). The x-axis indicates treatments and time, including ALL, ALL + CTAB, Rhamnolipids, SDS, SLS, and Triton X-100, while the y-axis shows the abundance of respective features.

3.5.1. Degradation of SLS

The number of genes and enzymes linked to the metabolism of carbohydrates and amino sugars (frlD, frlB, and nanM) remained at or close to nil, suggesting that these pathways are not essential for the breakdown of SLS. The abundances of amnD (2-aminomuconate deaminase) and HEXA_B (hexosaminidase) reached 4000 and 5000, respectively, indicating activation of aromatic ring cleavage and amino sugar metabolism, most likely in response to nitrogenous and aromatic intermediates produced during SLS sulfonated alkyl chain breakdown. Trimethylamine monooxygenase (EC4) was also predicted to be in high abundance, which further suggests that nitrogen- and sulfur-containing surfactant byproducts were being transformed. This is consistent with SLS breakdown products.

The consortia’s ability to degrade complex intermediates was demonstrated by the significant upregulation of pathways for the breakdown of aromatic compounds, including 2-nitrobenzoate, 2-aminophenol, and L-tryptophan, with some having abundances above 15,000. The majority of the carbohydrate, fermentation, and stress adaptation pathways (such as pyruvate fermentation, heterolactic fermentation, acid stress chaperone hdeA, and mycolate biosynthesis) remained at baseline or zero in the SLS-only system, compared to mixed surfactants or biosurfactant-only treatments. This suggests that the consortia are effective for the bioremediation of settings with high concentrations of SLS due to this targeted metabolic adaptation.

According to other studies, SLS and similar anionic surfactants do not primarily induce carbohydrate and amino sugar metabolism pathways during degradation; instead, they favor upregulation of aromatic compound breakdown enzymes, such as ring-hydroxylating dioxygenases for ring cleavage, which is consistent with the current study’s lack of activation in frlD, frlB, and nanM [90,95,96,97]. It has been documented that microbial consortia exposed to surfactants or aromatic hydrocarbons show increased activity and abundance of important enzymes like dioxygenases and deaminases, which facilitate the effective breakdown of complex intermediates [95,96,97]. These findings are consistent with the significant upregulation of aromatic compound degradation pathways (such as 2-nitrobenzoate, 2-aminophenol, and L-tryptophan) noted in our results. Our findings are also consistent with those of Li et al. [95], Wang et al. [40], and Liu et al. [96], who reported high abundances of trimethylamine monooxygenase and other nitrogen/sulfur-transforming enzymes as part of metabolic adaptations to surfactant-derived byproducts in both synthetic and biosurfactant systems. Furthermore, Liu et al. [96] and Yang et al. [97] found that optimized microbial communities or those with co-metabolic substrate additions achieve improved biotoxicity reduction and degradation rates, which are on par with or better than the consortia’s performance in upregulating particular catabolic pathways and degrading complex aromatic intermediates in the current work. Overall, these comparisons show that our results with SLS demonstrate strong adaptive catabolism that may improve bioremediation performance, extending recognized patterns from single-surfactant or aromatic-focused investigations.

3.5.2. Degradation of SDS

Compared to treatments like mixed surfactants or biosurfactant-only, the microbial consortia exposed to high concentrations of SDS (4%) showed a different metabolic response. Sulfatase and β-oxidation pathways were also implicated in SDS degradation, but there was a clear focus on nitrogenous and aromatic catabolism. Notably, the number of genes and enzymes linked to the metabolism of fructoselysine and amino sugars (frlD, frlB, and nanM) remained at or close to baseline, suggesting that these pathways are not essential for the breakdown of SDS. Rather, hexosaminidase (HEXA_B) at 5000 and 2-aminomuconate deaminase (ammD, EC1) at the abundance of 4000 were distinctly upregulated, indicating a shift towards aromatic ring cleavage and amino group removal activities. In contrast to SLS, SDS treatment caused a wider activation of pathways such as the breakdown of 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate semialdehyde, 2-nitrobenzoate, and L-tryptophan, suggesting the consortia’s adaptability to aromatic intermediates produced by surfactants.

The increased abundance of trimethylamine monooxygenase (EC4) suggests that nitrogen-containing byproducts were actively being transformed. Mycolate biosynthesis was upregulated only on day 1 (abundance of over 10,000), which may indicate temporary modification of the cell membrane in response to surfactant stress. Instead of depending on general carbohydrate metabolism, the predominance of aromatic and nitrogenous compound degradation pathways indicates that the microbial consortia are either enriched for or have adapted to taxa capable of using SDS and its breakdown products as carbon and nitrogen sources. The microbial consortia’s ability to adapt to and perhaps degrade SDS was demonstrated by the larger metabolic response that the SDS treatment caused, which included activation of both stress response and aromatic degradation pathways.

According to several studies, Zhu et al. [98], Najim et al. [99], Awi et al. [100] and Ambily & Jisha [101], high concentrations of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) significantly alter microbial community structures in contaminated environments, leading to the enrichment of genera such as Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Flavobacterium, which are recognized for their abilities to degrade surfactants and aromatic compounds. Exposure to SDS increases genes linked to nitrogen and sulfate respiration while decreasing those linked to nitrogen fixation and carbohydrate metabolism [98,102,103]. This is consistent with increased activities in nitrogenous and aromatic catabolism in our findings. As reflected in this study, according to Ambily & Jisha [101], the biodegradation of SDS usually proceeds by sulfatase-mediated desulfation and β-oxidation, yielding intermediates including dodecanol, dodecanal, and decanoic acid, followed by fatty acid catabolism.

Furthermore, Zhu et al. [98], Zhao et al. [103] and Awi et al. [100] state that SDS degradation often results in the upregulation of enzymes involved in aromatic ring cleavage and amino group removal, such as hexosaminidase and 2-aminomuconate deaminase, especially at high concentrations. Metabolism of nitrogen-containing byproducts in SDS degradation is supported by the enhanced expression of trimethylamine monooxygenase and other nitrogen-transforming enzymes [98,103]. According to Zhao et al. [103], early exposure to SDS frequently causes transient improvements in mycolate production and membrane modification pathways as defenses against surfactant-induced stress. Overall, SDS-treated microbial consortia exhibited wider activation of stress response and aromatic degradation pathways, and this offers better metabolic flexibility [98,103].

3.5.3. Degradation of Rhamnolipids

The acid stress chaperone gene hdeA (K08) demonstrated a notable rise on day two, with abundance levels over 3000, signifying a microbial reaction to stress caused by surfactants. Up to 500 copies of the atoD (K09) gene, which codes for the acetate CoA/acetoacetate CoA-transferase alpha subunit, were found, indicating increased metabolism of short-chain fatty acids. With abundance values at 5000, hexosaminidase (EC10, HEXA_B) was the most strongly elevated enzyme, suggesting enhanced glycoside hydrolysis that may be connected to surfactant breakdown. L-arabinose 1-dehydrogenase (EC6) and 3-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA hydrolase (EC5) both reached roughly 250, suggesting minor but significant involvement in the metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates. Mycolate biosynthesis (Path1), with abundance values peaking at 30,000, was shown to be the most upregulated pathway on day 1. This implies alteration of the cell membrane, perhaps as an adaptive reaction to exposure to surfactants. Changes in central carbon metabolism were also shown by the significant elevation (over 7500) of pyruvate fermentation to acetone (Path6). To further support metabolic adaptability, heterolactic fermentation (Path10) reached 2000. Remarkably, most genes and enzymes directly linked to aromatic or hydrocarbon breakdown (such as ammD, frlD, and frlB) stayed at or close to baseline, highlighting the fact that the observed increase is more closely linked to cell membrane modification and the surfactant stress response. With an emphasis on stress tolerance and membrane modification, this pattern highlights the uniqueness of microbial response to rhamnolipid.

According to Yang et al. [104], Grether et al. [105], and Sandoval et al. [106], rhamnolipids, like other surfactants, can damage microbial membrane integrity and activate stress response pathways, such as chaperone and oxidative stress genes. This observation is consistent with the significant increase in the acid stress chaperone gene hdeA (K08) in the current study. Nevertheless, these earlier studies usually used lower rhamnolipid concentrations (≤300 ppm), indicating that the 4% hdeA upregulation in our results probably surpasses previously documented levels. Furthermore, Saadati et al. [107] and Yang et al. [104] note that rhamnolipids also increase membrane permeability and change lipid composition in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This is in line with the significant upregulation of mycolate biosynthesis (Path1) seen here, suggesting a similar microbial strategy for preventing surfactant-induced membrane disruption.

The increase in atoD (K09) gene copies and increased pyruvate fermentation to acetone (Path6) in our results are consistent with Hu et al.’s [108] report that rhamnolipids promote volatile fatty acid (VFA) production and reroute central carbon metabolism. However, the scale of these metabolic shifts at 4% rhamnolipid appears amplified beyond the lower concentrations used in those studies. Additionally, Gill et al. [93] reported increased extracellular enzyme activities in rhamnolipid-exposed biofilms, including β-glucosidase and aminopeptidase. These findings corroborate the significant increase in hexosaminidase (HEXA_B) abundance in the current study, which may be related to glycoside hydrolysis during surfactant breakdown or biofilm matrix remodeling. The same authors noted that this is in contrast to the enzyme decreases commonly observed with synthetic surfactants such as SDS. Moreover, under rhamnolipid exposure, Wang et al. [92] found minimal changes in genes related to aromatic or hydrocarbon breakdown (e.g., ammD, frlD, frlB) unless specific pollutants were present, which is consistent with our findings that the microbial response is dominated by stress tolerance and membrane adaptation rather than enhanced catabolic pathways. Overall, these comparisons highlight that while our high-concentration treatment elicits responses congruent with prior literature, the intensity of functional shifts, particularly in stress and metabolic rerouting, may represent an extension of established patterns, warranting further investigation into dose-dependent thresholds.

3.5.4. Degradation of Triton X-100

The abundance of K08 (hdeA; acid stress chaperone) reached 2000, suggesting that periplasmic protein stabilization is triggered by pH-lowering byproducts from degradation, preventing aggregation in acidic environments. The abundance of EC3 (butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase) was up to 4000, whereas K09 (atoD; acetate CoA/acetoacetate CoA-transferase alpha subunit) was up to 2000, which, like beta-oxidation of ether-cleaved fragments, may enable CoA transfer for short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) utilization. Propionyl-CoA may be carboxylated to methylmalonyl-CoA by EC10 (propionyl-CoA carboxylase), therefore incorporating odd-chain byproducts into the TCA cycle. In contrast to other surfactants where aromatic pathways were insignificant, here, modest abundances indicate partial engagement: K06 (ammD; 2-aminomuconate deaminase) and EC1 (2-aminomucinate deaminase) deaminate muconate intermediates, a step in catechol or muconate pathways downstream of ring breakage. Benzoate production feeding into aromatic pathways may be facilitated by the presence of EC7 (3-hydroxybenzoate synthase), as seen by the abundance of 500. The production of mycolic acids, which improve cell wall hydrophobicity and impermeability, is highlighted by the high abundance of Path1 (mycolate biosynthesis), with a peak abundance of over 40,000. The high abundance of genes like hexosaminidase and 2-aminomuconate deaminase, as well as pathways like mycolate biosynthesis and heterolactic fermentation, suggests a mechanistic sequence where Triton X-100 is initially cleaved at its ether bonds, followed by further breakdown of aromatic and aliphatic fragments into central metabolic intermediates. The ability of these microbial communities to use carbon derived from surfactants and adjust to surfactant-induced environmental changes is demonstrated by the observed enrichment of functional genes and metabolic pathways, such as those involved in ether bond cleavage, aromatic compound transformation, and stress adaptation.

Guan et al. [109] state that bacteria respond to acid stress by upregulating chaperones and membrane-associated proteins to maintain protein stability and cellular integrity under acidic or stressful conditions. This is consistent with the current study’s observed increase in hdeA (K08) abundance (2000), which suggests activation of periplasmic protein stabilization mechanisms probably triggered by acidification from surfactant degradation byproducts. Guan et al. [109] and Lam Dinh Bui et al. [60] further reported that non-ionic surfactants such as Triton X-100 can increase membrane permeability, leading to changes in lipid composition for protection. This is consistent with the notable upregulation of mycolate biosynthesis (Path1, >40,000) observed here, which suggests substantial cell wall remodeling to improve hydrophobicity and impermeability.

The increased abundance of butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase (EC3, 4000) and atoD (K09, 2000) in our results, which indicate improved short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) utilization for energy production and redox balance amid surfactant degradation, are corroborated by Guan et al. [109], who also reported the upregulation of the glyoxylate cycle and fatty acid β-oxidation pathways in Pseudomonas nitroreducens during growth on Triton X-100. Compared to the studies with SDS or rhamnolipids, the modest upregulation of genes involved in aromatic compound transformation (e.g., ammD, EC1, EC7) in this study reflects partial engagement of these pathways. This is corroborated by Guan et al. [109] and Alkhatib et al. [110], who demonstrated that specific bacteria cleave ether bonds in Triton X-100 to produce aromatic intermediates metabolized via catechol and benzoate routes.

Furthermore, the enrichment of genes for ether bond cleavage, aromatic transformation, and stress adaptation in our study supports a mechanistic sequence of initial ether bond cleavage, followed by the breakdown of aromatic and aliphatic fragments and their integration into central metabolism. This is in line with transcriptomic analyses by Bui et al. [60], which showed upregulation of oxidoreductases, fatty acid degradation, and glyoxylate cycle genes during Triton X-100 metabolism. Overall, these comparisons show that although our findings at 4% Triton X-100 are consistent with known patterns in the literature, the degree of stress adaptation and metabolic changes may be greater than those in studies conducted at lower concentrations, suggesting possible concentration-dependent effects deserving of additional investigation.

3.5.5. Degradation of Surfactant Mixture (ALL)

Strong activation of the metabolism of carbohydrates and amino acids was indicated by the abundance of frlD (K01), which began at zero and rose to 3000, while allS (K03) and fdrA (K04) both exceeded 4000. With values sustained around 1500, the abundance of frlB (K05) exceeded 3000, indicating a persistent participation in fructoselysine metabolism. Sialic acid metabolism was identified as a possible adaptation mechanism when nanM (K07), which codes for N-acetylneuraminate epimerase, rose from zero to 4000. Enhanced fatty acid and amino acid interconversion suggested by N-acetylneuraminate epimerase (EC2) and butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase (EC3) reaching up to 3000 and above 6000, respectively. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase (EC10) abundance reached 3000, supporting increased propionate metabolism. Mycolate biosynthesis (Path1) showed the most significant pathway upregulation, reaching 20,000, showing significant cell membrane alteration. Changes in central to fermentative metabolism were reflected in the high upregulation of pyruvate fermentation to acetone (Path6) (over 7500 abundance) and heterolactic fermentation (Path10) (over 6000 abundance).

The significant increases in abundance were observed in genes related to fructoselysine metabolism (frlD, frlB), transcriptional regulation (allS), and N-acetylneuraminate epimerization (nanM), indicating that the consortia are using a variety of metabolic pathways to process the different surfactant components. The active transformation of sulfonated and ethoxylated surfactant headgroups, including those in SLS, SDS, and Triton X-100, is suggested by the high abundance of N-acetylneuraminate epimerase and associated pathways. Increased short-chain fatty acid metabolism is suggested by the overexpression of butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase and acetate CoA/acetoacetate CoA-transferase, which most likely reflects the hydrophobic tail degradation of surfactants. Compared to rhamnolipid treatment, the mixed surfactant system produced a stronger and more extensive metabolic reaction. The microbial consortia may be able to co-metabolize a variety of substrates obtained from surfactants due to the activation of several carbohydrate and amino sugar pathways, as well as fermentation channels (pyruvate fermentation to acetone, heterolactic fermentation).

Gill et al. [91] claim that rhamnolipid by itself increases the activity of extracellular enzymes such as leucine aminopeptidase and beta-glucosidase, promoting higher metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates. The strong upregulation of frlD, frlB, and related genes in the current mixed surfactants is consistent with Triton X-100’s more variable effects, whereas SDS tends to decrease these activities. This suggests a synergistic or additive effect that permits broader substrate utilization than with rhamnolipid or SDS alone. Surfactants like Triton X-100 and rhamnolipid can increase volatile fatty acid production and carbon conversion efficiency, especially when combined with physical pretreatments [111,112]. This is consistent with the increased expression of butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase and propionyl-CoA carboxylase in our mixture.

According to Cui et al. [112], our results show that the upregulation of mycolate biosynthesis and fermentative pathways (such as pyruvate to acetone and heterolactic fermentation) is more prominent in mixed systems, suggesting greater cell membrane adaptation and metabolic flexibility than is usually seen with single surfactants. The same authors reported that mixed-bacteria systems supplemented with rhamnolipid and Tween-80 increased abundance of genes for amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism. However, the even higher and longer-lasting gene upregulation in the mixed surfactant system described here may support more extensive co-metabolism. Furthermore, Cui et al. [112] pointed out that active transformation of sulfonated and ethoxylated surfactant headgroups is indicated by the high abundance of N-acetylneuraminate epimerase and related pathways, a trait that is less noticeable in single-surfactant investigations but clear in our mixed setup. Similar to our findings, Ravi et al. [111] and Cui et al. [112] also noted effective hydrophobic surfactant component degradation leading to increased short-chain fatty acid metabolism, which indicates higher VFA generation in systems using Triton X-100 and rhamnolipid. Overall, these comparisons show that the functional changes in our high-concentration mixed surfactant treatment go beyond those in previous single- or limited-mixture investigations, highlighting synergistic metabolic improvements that may guide more sophisticated bioremediation techniques.

3.5.6. Degradation of Surfactant Mixture (ALL) with 1% CTAB

Butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase reached 8000 in abundance, allowing SCFA utilization, while K09 (atoD) nearly reached 4000 in abundance, possibly facilitating CoA transfer in beta-oxidation byproducts. Propionyl-CoA carboxylase reached almost 1000 in abundance, likely facilitating odd-chain incorporation into central metabolism. Both pyruvate fermentation to acetone and heterolactic fermentation pathways reached 5000 in abundance, suggesting the conversion of glycolytic intermediates to acetone/lactate/ethanol. Mycolate biosynthesis reached 30,000 in abundance, signalling for cell wall fortification against CTAB’s cationic toxicity. K08 (hdeA) reached over 1800 abundance, addressing acidity from breakdown, indicating the prominence of stress responses. Similarly to surfactant mixture (without CTAB), both pyruvate fermentation to acetone and heterolactic fermentation pathway reached over 5000, likely responsible for converting glycolytic intermediates to acetone/lactate/ethanol.

The significant rise in genes like fructose lysine 6-kinase, LysR family transcriptional regulator, and fructoselysine 6-phosphate deglycase indicates a robust activation of pathways related to the metabolism of carbon and nitrogen supplies obtained from surfactants. Notably, allS and fdrA abundances were greater than 3000, suggesting a strong metabolic and regulatory response. The ability of the consortia to handle environmental stress and nutrient assimilation is further demonstrated by the overexpression of nanM (N-acetylneuraminate epimerase) and hdeA (acid stress chaperone), which is probably caused by surfactant toxicity or breakdown products. The significant abundance of fermentation pathways (pyruvate fermentation to acetone, heterolactic fermentation) and mycolate biosynthesis (up to 30,000) indicates that cell membrane modification and alternative energy-generating processes are essential for microbial survival and surfactant transformation.

According to Luo et al. [113] and Cheng et al. [114], surfactants increase the production of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) by encouraging solubilization, hydrolysis, and acidification in sludge fermentation. Key genes for VFA generation are frequently overexpressed to drive efficient substrate conversion and energy recovery, which is consistent with the high abundance of butyrate–acetoacetate CoA-transferase and propionyl-CoA carboxylase genes supporting SCFA utilization and odd-chain incorporation in the mixture containing CTAB in this study. Similar upregulation of genes involved in central carbon metabolism and fermentation (e.g., pyruvate fermentation to acetone, heterolactic fermentation) in surfactant-amended sludge and food fermentation systems has also been reported [113,114,115]. These findings are mirrored in our study with a shift towards alternative energy-generating pathways under surfactant stress. Furthermore, exposure to surfactants causes genes for membrane fortification, oxidative stress response, and environmental adaptation to enable microbial survival in harsh conditions [90,113,116]. This is consistent with the significant increase in mycolate biosynthesis genes (up to 30,000 in abundance) and acid stress chaperones (e.g., hdeA) seen here, especially in response to cationic agents like CTAB. The widespread metabolic remodeling and stress adaptation due to surfactants, due to the upregulation of regulatory and metabolic genes (e.g., LysR family transcriptional regulators, fructose lysine metabolism), is supported by Ke et al. [117] and Wang et al. [118]. Through metagenomics studies or PICRUSt, the literature consistently reported that surfactant addition increases abundances of genes for VFA production, stress response, and membrane modification, insights mirrored in the current findings [113,114,116,119]. Moreover, as shown in our mixed surfactant treatment, the coordinated upregulation of fermentation, SCFA utilization, and stress adaptation pathways highlights the metabolic flexibility and resilience of consortia, which is essential for effective surfactant transformation and environmental detoxification [113,114]. Although there are no studies that degrade high concentrations of surfactant, the trends in this study are consistent with previous research, demonstrating consortia’s adaptive processes that may enhance surfactant bioremediation.

3.6. The Implications and Limitations of the Study

The findings from this comprehensive study, which combine shotgun metagenomics, physicochemical and foaming analyses, 16S rRNA community profiling, and functional predictions, highlight the important implications in understanding surfactant degradation by microbes as well as aid in developing environmental bioremediation strategies. The effective surfactant biodegradation relies on the microbial specialization and succession, as highlighted by the succession of different taxa. The distinct microbial community changes across different surfactants revealed the specialized consortia adapted to the chemistry of each surfactant. Their ecological function as the primary and secondary degraders is highlighted by the dominant taxa such as Achromobacter, Paraburkholderia, and Bordetella in rhamnolipids and mixed surfactants, and Pseudomonas in non-ionic and anionic surfactant enrichments (e.g., SLS, SDS, and Triton X-100). Amongst the taxa identified in this study, only Pseudomonas has been widely studied. For example, it has been reported as one of the major taxa in a study on the influence of surfactants on microbial populations [120]. Pseudomonas spp. capable of decomposing SDS have also been identified in other studies [121,122], etc. Therefore, this work presents an opportunity to further investigate these under-reported taxa. A biodegradative process important for the full mineralization is reflected in the temporary succession, which starts with the rapidly growing primary degraders targeting the original surfactant molecules, while the secondary degraders metabolize the intermediates. This pattern suggests that a useful way is to use or design microbial communities that adapt and thrive in phases, maximizing the effectiveness of surfactant breakdown [123], while reducing the build-up of problematic intermediates that can promote foaming, as shown in this study.

The study also demonstrates that the functional capacity reflects community composition and degradation pathways. By elucidating the metabolic capacity behind surfactant degradation, the shotgun metagenomic KEGG pathway analysis and PICRUSt-based predictive functional profiling complemented taxonomic data [124,125]. The dominant microbial taxa and surfactants closely matched the fatty acid metabolism, ammonium compound metabolism, aromatic compound degradation, sulfur metabolism, etc., which have a direct link to surfactant breakdown [126,127,128]. The combination of taxonomic and functional analysis data has shown that the shift in microbial populations can potentially be used as a stand-in for metabolic capacity, enabling the prediction of degradation pathways and outcomes without the need for a complete sequencing of the metagenomes. This potential predictive ability is important in tracking the effectiveness of biodegradation and can inform bio-stimulation and bioaugmentation interventions.

The physicochemical monitoring (such as decreases in pH, dissolved oxygen, oxidation–reduction potential, TOC, and COD) and foaming activity measurements (reduced foaming activity) provide robust and measurable indicators for microbial surfactant degradation. The ability of the enriched consortia to degrade surfactants under aerobic conditions was demonstrated by notable decreases in these parameters in surfactants such as rhamnolipids, SLS, and the mixture (ALL). Whereas CTAB-containing mixtures of surfactants showed a delayed or reduced degradation, which is in line with CTAB’s recognizable antimicrobial effects, suggesting the need for biodegradation condition optimization (e.g., temperature adjustment, bioaugmentation with resistant strains, aeration adjustments, etc.) to circumvent these inhibitory effects [17,124]. The changes in foaming patterns, including the temporary increases in foaming after an initial reduction in SDS because of possible intermediate formation, highlight practical difficulties of biodegradation in large-scale applications. Therefore, these microbial and physicochemical correlations could facilitate the early detection of problematic intermediates and aid in controlling foaming for process stability in bioremediation applications.

By associating a particular microbial taxon with the ability to degrade a particular surfactant(s) and related metabolic pathways, the insights from this study can inform process optimization and targeted bioremediation. For instance, Pseudomonas species would be the perfect candidate for remediating or degrading anionic and non-ionic surfactants. Whereas, when dealing with recalcitrant anionic surfactants like SLS, Paraburkholderia exhibits the highest ability. Bordetella becomes the best candidate for detoxifying cationic surfactants such as CTAB. Enterobacter’s capacity to produce foaming intermediates during SDS degradation necessitates a consortium design and process optimization (improving physicochemical conditions) that strikes a balance between mineralization and foaming control. Furthermore, the insights regarding substrate utilization or depletion phases marked by variations in DO and ORP imply that treatment or microbial degradation of surfactants should accommodate succession and modify aeration to allow for shifting metabolic requirements, thus maximizing the total degradation and reducing inhibition or partial mineralization [129,130]. By combining the physicochemical monitoring and omics approaches (16S rRNA sequencing, PICRUSt prediction, and shotgun metagenomics) for thorough evaluation of surfactant biodegradation, the study shows that these integrative frameworks can be used to speed up functional characterization and remediation for various complex pollutant systems. In addition, the predicted pathways of xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism of various aromatic compounds highlight the potential of the enriched consortia to remediate co-contaminants such as hydrocarbons in oil-contaminated environments.

Although metagenomics and PICRUSt predictions offer a useful blueprint of microbial functional potential, a validation of active degradative pathways and enzymes still requires confirmatory analysis through the employment of proteomics and meta-transcriptomics [131,132]. To investigate the robustness and applicability of these consortia under field-relevant conditions, it would be essential to scale-up treatments, optimize physicochemical conditions, investigate different concentrations, and test bioaugmentation strategies with the identified important species or consortia [124,133]. Overall, all these findings contribute to the advancement of our practical knowledge and understanding of microbial surfactant biodegradation. This work establishes a basis for efficient biodegradation methods that target a combination of surfactants in complex matrices by elucidating community succession, functional gene enrichment, and physicochemical trends consistent with successful biodegradation.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study illustrates the effectiveness of an integrated, multi-omics approach that incorporates long-read shotgun metagenomics, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, PICRUSt2 functional predictions, and physicochemical proxies to elucidate or predict the aerobic biodegradation of various surfactants (SDS, SLS, rhamnolipids, Triton X-100, and CTAB, either individually or in combination at 4% w/v) by microbial consortia derived from oil-contaminated soils over a period of 14 days. Pseudomonadota (85–95%) dominated the communities, with Pseudomonas leading in the breakdown of SDS and SLS. Paraburkholderia and Bordetella dominate in the recalcitrant anionic and cationic surfactants, respectively. Rhamnolipids showed the highest TOC reduction (56%), with SLS (50%) and the surfactant mixture without CTAB (50%) illustrating significant degradation efficiencies. Foaming activity was also reduced by 45–64%, which shows that they can be degraded by bacteria. In contrast, CTAB’s bactericidal effects only reduced TOC by 21% in combined treatments. PICRUSt2 analysis showed that genes and pathways involved in alkyl chain oxidation, sulfate ester hydrolysis, aromatic ring cleavage, and fatty acid/sulfur metabolism were enriched in a substrate-specific way. This gave us mechanistic insights without needing to directly measure metabolites. Corroborative physicochemical shifts, such as pH acidification, DO consumption, ORP fluctuations, COD peaks indicating intermediate formation, and foaming reductions, confirmed microbial activity and established scalable, cost-effective proxies for monitoring bioremediation when advanced analytics are impractical.

The findings enhance our understanding of microbial succession and functional adaptation in surfactant-contaminated environments, providing a basis for developing targeted bioaugmentation strategies utilizing identified degraders such as Pseudomonas for anionic surfactants and Bordetella for cationic surfactants. This study connects taxonomic dynamics to metabolic potential and proxy indicators, addressing knowledge gaps in the degradation of high-concentration mixed surfactants. The findings have implications for enhancing wastewater treatment, soil remediation, and industrial effluent management in areas with a lack of or lenient regulations. The limitation of the study includes the lack of direct metabolite profiling (e.g., through LC-MS) and the absence of proteomic or transcriptomic validation of PICRUSt2 predictions, which could enhance the accuracy of inferred pathways. Future research should investigate bioaugmentation using CTAB-resistant strains, conduct scale-up experiments in field conditions, and optimize parameters, including surfactant ratios, aeration, pH, and temperature, to improve degradation rates and reduce inhibitory effects. This study facilitates sustainable, microbe-driven approaches to reduce the environmental persistence of surfactants, thereby contributing to global pollution control and ecosystem restoration efforts.

Supplementary Materials