Abstract

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is a key staple crop in the Peruvian Andes, but its productivity is threatened by fungal pathogens such as Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternata. In this study, 71 native bacterial strains (39 from phyllosphere and 32 from rhizosphere) were isolated from potato plants across five agroecological zones of Peru and characterized for their plant growth-promoting (PGPR) and antagonistic traits. Actinomycetes demonstrated broader enzymatic profiles, with 2ACPP4 and 2ACPP8 showing high proteolytic (68.4%, 63.4%), lipolytic (59.5%, 60.6%), chitinolytic (32.7%, 35.5%) and amylolytic activity (76.3%, 71.5%). Strain 5ACPP5 (Streptomyces decoyicus) produced 42.8% chitinase and solubilized both dicalcium (120.6%) and tricalcium phosphate (122.3%). The highest IAA production was recorded in Bacillus strain 2BPP8 (95.4 µg/mL), while 5ACPP6 was the highest among Actinomycetes (83.4 µg/mL). Siderophore production was highest in 5ACPP5 (412.4%) and 2ACPP4 (406.8%). In vitro antagonism assays showed that 5ACPP5 inhibited R. solani and A. alternata by 86.4% and 68.9%, respectively, while Bacillus strain BPP4 reached 51.0% inhibition against A. alternata. In greenhouse trials, strain 4BPP8 significantly increased fresh tuber weight (11.91 g), while 5ACPP5 enhanced root biomass and reduced stem canker severity. Molecular identification confirmed BPP4 as Bacillus halotolerans and 5ACPP5 as Streptomyces decoyicus. These strains represent promising candidates for the development of bioinoculants for sustainable potato cultivation in Andean systems.

1. Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is one of the most important staple crops worldwide, playing a crucial role in food security and agricultural sustainability [1,2,3]. Originating in the Andean region, particularly in present-day Peru, this tuber crop has been cultivated for thousands of years, contributing significantly to the livelihoods of small-scale farmers and large agricultural enterprises alike [4,5]. Peru, recognized as the center of origin and diversification of potato, hosts an extensive genetic reservoir with over 3000 native varieties, making it a valuable resource for global breeding programs and sustainable agricultural development [6,7,8].

Despite its agronomic and economic significance, potato production is severely constrained by various phytopathogenic fungi [9,10], with Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria spp. being among the most destructive [11,12,13]. Rhizoctonia solani causes black scurf and stem canker, leading to poor tuber formation and significant yield losses [11,14], while Alternaria complex (A. solani, A. alternata) is a causal agent of early blight, reducing photosynthetic efficiency and affecting tuber quality, with A. alternata being the one that often acts as a secondary or opportunistic pathogen after other diseases [12]. Conventional disease management strategies rely heavily on synthetic fungicides, which, despite their effectiveness, pose several challenges, including environmental contamination, pathogen resistance development, and health risks to farmers and consumers [15,16]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for eco-friendly, sustainable alternatives to mitigate these fungal threats [17,18,19].

In this context, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) have emerged as promising biological control agents due to their ability to enhance plant health and suppress phytopathogens through multiple mechanisms [20,21]. PGPR include various bacterial genera, among which Bacillus and Actinomycetes are extensively studied for their dual role in promoting plant growth and exhibiting antagonistic activity against fungal pathogens [22,23]. These bacteria employ a combination of direct and indirect strategies to benefit plants: they produce phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) to stimulate root development, solubilize phosphate to enhance nutrient availability, and secrete siderophores that chelate iron, limiting pathogen proliferation [24,25]. Additionally, they generate a diverse array of lytic enzymes and antifungal compounds, providing an effective means of pathogen suppression [26].

The rhizosphere and phyllosphere of plants represent dynamic microbial niches where beneficial interactions between bacteria and host plants can be exploited for sustainable agriculture [27]. The rhizosphere, the soil–root interface, is rich in exudates that selectively recruit beneficial microbes, while the phyllosphere, the aerial surface of leaves, serves as a less explored but equally vital reservoir of microbial diversity. Given the heterogeneity of agricultural environments, isolating and characterizing indigenous microbial strains adapted to specific agroecological conditions is crucial for developing region-specific biocontrol solutions [28,29,30].

This study aims to isolate and characterize Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains from the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of potato plants cultivated in diverse agroecological zones of Peru. The primary objectives are to evaluate their plant growth-promoting traits, assess their antagonistic potential against Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternata, and identify strains with the highest biocontrol efficacy. By harnessing these indigenous microorganisms, this research seeks to contribute to the development of microbial-based biocontrol strategies that reduce dependency on chemical fungicides, enhance crop resilience, and promote sustainable potato production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Sites and Biological Material

Samples of Solanum tuberosum L. were collected from five agroecological regions across the central coast and highlands of Peru. A total of 50 phyllosphere (leaf) and 60 rhizosphere (soil) samples were obtained (details in Supplementary Table S1), ensuring representation from diverse altitudes and soil conditions. Additionally, potato plants exhibiting symptoms of fungal infection were collected from El Tambo district, Huancayo province, Junín Region, to obtain phytopathogenic isolates for antagonism assays. Samples were transported in sterile containers and processed within 24 h of collection.

2.2. Isolation and Morphological Characterization of Bacteria

Bacillus spp. were isolated following the protocol by Haddad et al. [31], with modifications. Ten grams of surface-sterilized potato leaves were homogenized in 90 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 7) and subjected to a heat treatment at 80 °C for 20 min to select for spore-forming bacteria. Serial dilutions up to 10−6 were plated on TGE agar (Tryptone, Glucose, Yeast extract) and incubated at 28 °C for 24 to 48 h. Colonies displaying whitish, mucoid or dry, irregular morphology were selected and purified. Gram staining confirmed their identity as Gram-positive rods. Actinomycetes were isolated from rhizospheric soil samples. Ten grams of soil were suspended in 90 mL of sterile 0.85% saline solution, serially diluted, and spread on Casein Agar supplemented with 50 µg/mL nystatin to inhibit fungal growth [32]. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for seven days. Colonies with distinct pigmentation and powdery texture were selected. Microscopic examination using lactophenol blue staining allowed identification of aerial and substrate mycelia, aiding in preliminary taxonomic placement using Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology [33].

2.3. Phenotypic Characterization

To evaluate environmental adaptability, bacterial isolates were tested for growth at different temperatures (4, 10, 15, and 20 °C) and pH (4, 5, 7, and 9) conditions. Growth was recorded visually and by optical density after 24 to 48 h of incubation under each condition, following Calvo and Zuñiga’s [34] protocol.

2.4. Lytic Enzyme Characterization

Lytic enzyme activity was assessed by qualitative plate assays. Chitinase production was evaluated using colloidal chitin agar, where hydrolysis halos were measured after five days of incubation at 28 °C [35]. Lipase activity was tested on Peptone Tween Agar (PTA), with opalescent halos indicating positive results after 48 h [36]. Proteolytic activity was observed on Skim Milk Agar, where clear zones around colonies indicated casein degradation [37]. Amylase activity was determined using Starch Agar incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, followed by iodine staining [38]. Cellulase production was evaluated on Minimal Medium with carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), incubated for ten days at 37 °C, and halos were visualized after Congo red staining [39].

2.5. PGPR Activity Assays

Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production was evaluated using the colorimetric Salkowski method. Bacillus strains were cultured in Nutrient Broth supplemented with L-tryptophan, while Actinomycetes were grown in ISP-2 medium, also supplemented with L-tryptophan. IAA production was quantified spectrophotometrically for ten days for Bacillus and seven to ten days for Actinomycetes [40]. Phosphate solubilization was assessed on Pikovskaya agar, measuring the ratio of halo to colony diameter to estimate solubilization efficiency [41]. Siderophore production was determined using Chrome Azurol S (CAS) agar, where a color change to yellow around the colonies indicated positive activity [42]. As a positive control, Bacillus 15 MB and Streptomyces spp. strains were used for the Bacillus and Actinomycete groups, respectively.

2.6. In Vitro Germination Assays

The germination-promoting effect of selected bacterial strains was evaluated on cherry tomato and true potato seeds. Seeds were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min followed by 3% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min, then rinsed with sterile distilled water. Bacterial suspensions were prepared by culturing strains in nutrient broth for 24 h at 28 °C and adjusting the concentration to 106–107 CFU/mL using a spectrophotometer at OD600 [34]. Seeds were immersed in the bacterial suspension for 15 min and sown on water agar (0.75%) in sterile Petri dishes. Each treatment included 25 seeds per plate with three replicates. Plates were incubated at 23 °C in the dark for seven days. Germination percentage was recorded daily and compared to untreated controls.

2.7. Antagonistic Activity Assays

The strains of R. solani and A. alternata used in this study were isolated from symptomatic potato plants collected in Huancayo city, Junin region, which were surface disinfected and plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA), identified morphologically and molecularly using ITS sequencing. Cultures were incubated at 22 °C for seven days. Pure isolates of Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternata were obtained via hyphal tip transfer. For dual culture assays, each bacterial isolate was streaked on one edge of a PDA plate while a fungal plug was placed on the opposite side. Plates were incubated at 25 °C, and radial growth inhibition was measured. The percentage inhibition was calculated using the formula: % inhibition = [(R0 − R1)/R0] × 100, where R0 is the radius of fungal growth in the control and R1 is the radius in presence of bacteria [43].

2.8. Greenhouse Evaluation

The biocontrol efficacy of the most promising bacterial strains was further tested in greenhouse conditions. The nine strains were chosen based on their performance across multiple in vitro traits (e.g., IAA production, phosphate solubilization, siderophore and enzyme production) and their antagonistic activity in dual-culture assays. Bacterial inocula were prepared at 1 × 107 CFU mL−1. True potato seed (TPS) from cv. Canchay × Ccompis was sown 0.5 cm deep in seedling trays (cell volume 2.7 cm3). After 25–30 days, emergence reached 95% at the four true-leaf stage, and three seedlings were transplanted per 3 L bag. Plants were then inoculated with 1 mL per plant of each bacterial strain at 1 × 108 CFU mL−1. The positive control received wheat grains colonized by Rhizoctonia mycelium, whereas the negative control received water only (no bacteria), and a chemical control (Benomyl-treated) was included. After one month, plant height and chlorophyll content were measured, plants were re-inoculated with the bacterial strains, and seven days later, wheat grains colonized by R. solani mycelium were applied at the plant collar. Fungal growth on the plants was monitored, and canker formation on stems was recorded seven days thereafter; plants were then harvested to determine fresh and dry weight of tuberlets (minitubers) and stem canker length.

2.9. Molecular Identification

Genomic DNA from selected bacterial strains was extracted using GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using universal primers fD1 and rD1. The PCR protocol consisted of 30 cycles with denaturation at 93 °C for 45 s, annealing at 62 °C for 45 s, extension at 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Amplified products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel. PCR products were purified using the GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and sent for sequencing to Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE, and identity was confirmed through BLAST v 2.11, analysis against the NCBI 16S rRNA gene database. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA11 software with the Tamura-Nei model and maximum likelihood method, including 1000 bootstrap replications.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using agricolae package in RStudio. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05) was used to determine significant treatment differences. Graphs and figures were prepared using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Morphological Characterization of Bacterial Strains

A total of seventy-one bacterial strains were isolated from Solanum tuberosum plants collected from five agroecological regions of Peru, comprising both highland and coastal zones. These included thirty-nine isolates from phyllospheric samples and thirty-two from rhizospheric soil (Table S1). The isolation strategy targeted spore-forming Bacillus spp. and Actinomycetes, using TGE and Casein Agar, respectively, following heat or saline dilution pretreatments. The diversity of ecological origins, ranging from Huancavelica and Puno to Lima, Huánuco, and Cajamarca, contributed to the richness of the microbial collection.

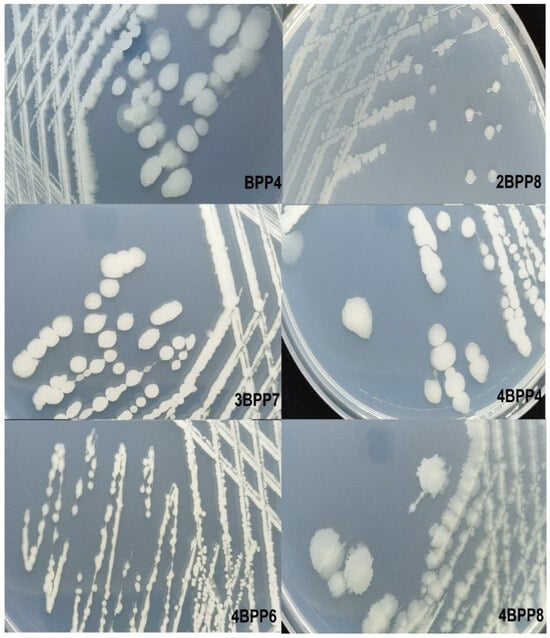

Morphological examination of Bacillus strains revealed consistent features across isolates. For instance, strain BPP4 formed irregular colonies with undulate margins, opaque cream-colored surfaces, and elevated profiles, ranging in size from 3.97 to 5.87 mm. Similarly, 4BPP6 showed curled, opaque, flat colonies of cream color and a diameter between 3.80 and 4.56 mm. Strain 4BPP8 exhibited a comparable curled morphology with slightly larger colonies (5.64–5.91 mm). In contrast, 2BPP8 produced small (1.66–2.75 mm), shiny colonies with entire margins and a crateriform elevation (Figure 1). These colony characteristics align with the known morphological variability of Bacillus species, and Gram staining confirmed their rod-shaped, Gram-positive nature (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Morphology of bacterial colonies of Bacillus species in Glucose, Tryptone and Yeast Extract (TGE) medium.

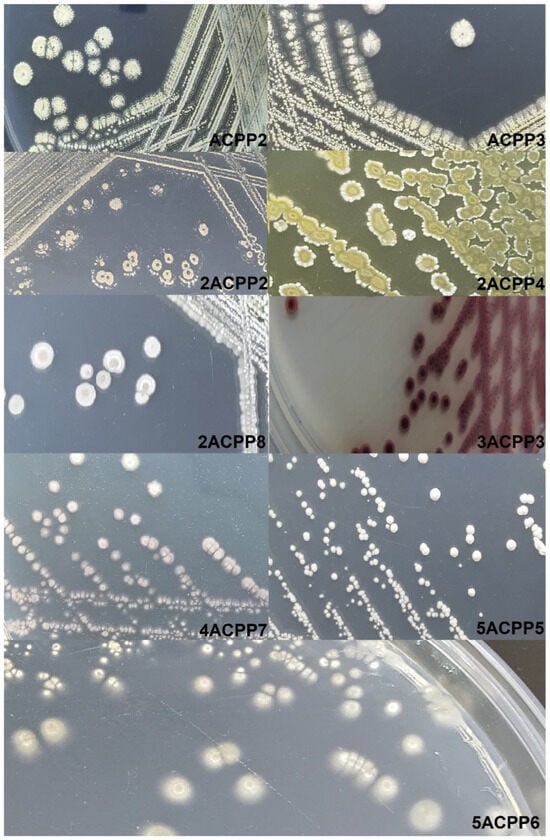

Actinomycete isolates displayed distinctive features. Colonies were predominantly circular or irregular, dry and powdery, with shades ranging from white to beige, gray, and even cherry-red. For example, strain 5ACPP5 formed white, circular colonies with entire margins, a powdery surface, and flat elevation, measuring 3.11–3.57 mm. Strain 2ACPP4 presented cream-colored, circular colonies with dentate borders and dimensions between 4.67–5.34 mm (Figure 2). Microscopic evaluation using lactophenol blue staining revealed dense aerial mycelium and branching vegetative filaments, consistent with the genus Streptomyces. A microculture of 5ACPP5 under 400× magnification showed coiled spore chains, a defining trait of this group (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Morphology of bacterial colonies of Actinomycetes in casein starch (CA) medium.

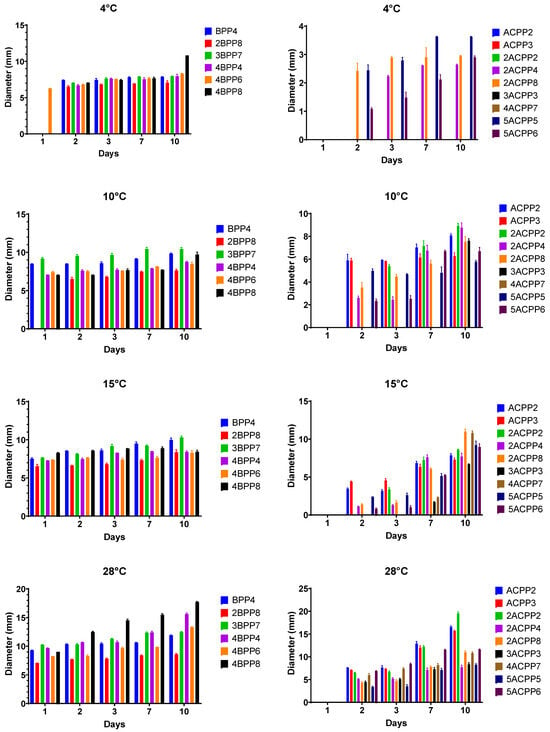

3.2. Phenotypic Characterization: Growth at Different Temperatures and pH

The evaluation of bacterial growth under varying temperature conditions revealed moderate psychrotolerance among selected isolates, particularly within the Bacillus group. At 4 °C, strain 4BPP6 demonstrated the highest adaptability, forming colonies that reached a diameter of 8.30 mm after ten days of incubation. This result indicates that although metabolic activity was considerably reduced at near-freezing temperatures, strain 4BPP6 retained sufficient physiological plasticity to maintain limited growth. Other Bacillus strains, including BPP4 and 2BPP8, exhibited smaller but measurable colony development at 4 °C, with diameters ranging from 4 to 8 mm, suggesting that sporadic low-temperature growth is possible within this group. In contrast, Actinomycetes isolates showed no significant development at 4 °C, with minimal development (2–4 mm) observed in strains such as 2ACPP8 and 5ACPP5, consistent with their general classification as mesophilic organisms (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Growth of Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains at 4 different temperatures for 10 days.

At 10 °C, growth rates improved notably for several strains. Bacillus strain 3BPP7 achieved a colony diameter of 10.43 mm, while 4BPP8 and 2BPP8 also demonstrated moderate expansion. Among Actinomycetes, growth at 10 °C remained minimal (<8 mm), reaffirming their preference for warmer conditions (Figure 3).

At 15 °C, most isolates exhibited enhanced growth, with Bacillus strains such as 3BPP7, 4BPP6, and 4BPP8 reaching diameters greater than 8 mm. Similarly, Actinomycete strains like 2ACPP2, ACPP3, and 5ACPP5 displayed moderate but sustained colony development, indicating that 15 °C is near the lower thermal threshold for effective actinomycete proliferation. Optimal growth was observed at 28 °C across all bacterial groups, with colony diameters exceeding 8 mm, even reaching some strain sizes greater than 15 mm (Figure 3).

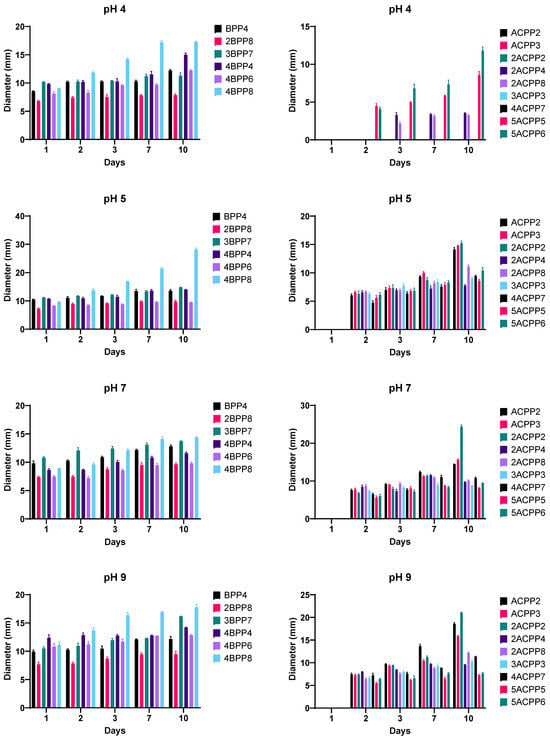

The pH tolerance assay revealed notable plasticity among the isolates. At a highly acidic pH of 4, growth was severely restricted in Actinomycetes group, and only strains 2ACPP2 and ACPP3 showed limited colony development, suggesting a basal level of acid tolerance within specific members of this group. In contrast, all Bacillus isolates succeeded in establishing visible colonies at pH 4 with size greater than 6 mm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Growth of Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains at 4 different pHs for 10 days.

At pH 5, an improvement in bacterial growth was evident. All evaluated Bacillus strains, including BPP4, 3BPP7, and 4BPP8, exhibited vigorous colony development with diameters ranging between 8.90 mm and 12.50 mm and 4BPP8 reached the highest size with a diameter of 29.3 mm at 10 days of growth. In Actinomycetes group, ACPP2, ACPP3 and 2ACPP2 obtained diameters of approximately 15 mm on average (Figure 4).

At neutral pH (7), all strains achieved their maximum growth potential. Colonies of Bacillus strains 4BPP8 and 3BPP7, as well as Actinomycete strains 2ACPP2 and 5ACPP5, expanded beyond 12 mm in diameter. It is important to note that strain 2ACPP2 had twice the diameter of the other bacterial strains of both groups (Figure 4).

At alkaline pH 9, moderate growth persisted across most strains, albeit with a slight reduction in colony diameter compared to pH 7. Notably, Bacillus strains 4BPP8 and 3BPP7, along with Actinomycetes 2ACPP2 and ACPP2, displayed good adaptability, suggesting potential utility in soils with higher pH levels, such as those found in arid or saline agricultural areas (Figure 4).

3.3. Lytic Enzyme Activity

The lytic enzyme activity of all selected strains was assessed to determine their potential roles in pathogen suppression and organic matter degradation. Among Bacillus strains, protease activity was observed in most isolates, with the highest activity recorded in strain 4BPP6 (63.28%), followed by 4BPP4 (58.87%) and 3BPP7 (54.30%). In contrast, strain BPP4 exhibited relatively low protease activity (17.83%) despite being one of the most promising PGPR strains overall (Table 1).

Table 1.

Enzymatic activity percentage of Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains.

In the Actinomycete group, 2ACPP4 had the highest proteolytic activity with 68.4%, followed by strain ACPP2 with 65.5%, and 5ACPP6 obtained the lowest proteolytic activity with 21.41%. Strain 5ACPP5 did not show proteolytic activity (Table 1).

Lipase activity varied across Bacillus isolates, with 2BPP8 demonstrating the highest lipolytic activity (40.2%), and BPP4 showing moderate activity (25.41%). In the Actinomycetes group, 2ACPP8 obtained 60.57%, followed by strain 2ACPP4 with 59.53%, and 3ACPP3 obtained the lowest lipolytic activity with 37.72%, but on average with higher values than Bacillus strains. None of the Bacillus isolates exhibited chitinase activity, which limits their capacity to hydrolyze fungal cell walls directly via chitin degradation. In contrast, almost all Actinomycetes strains showed chitinase activity except for 5ACPP6 (Table 1).

Amylase production was notably high in BPP4, which achieved the greatest starch degradation zone by BPP4 (70.81%), followed by 2BPP8 (68.65%), and surprisingly, strain 4BPP6 does not exhibit amylolytic activity. Actinomycetes strains obtained higher values than Bacillus in amylase production, highlighting ACPP2 and ACPP3 (Table 1).

Actinomycete isolates exhibited a broader enzymatic profile. The strain 5ACPP5, which showed excellent biocontrol and growth-promotion potential in subsequent assays, presented strong amylase activity (74.36%) and was the most effective chitinase producer (42.78%) among all Actinomycetes. Although 5ACPP5 lacked protease activity, it showed moderate lipase production (55.30%), indicating a distinctive enzymatic balance. In contrast, 2ACPP4 and 2ACPP8 were among the most enzymatically versatile strains, with high activities for proteases (68.4% and 63.44%, respectively), lipases (59.53% and 60.57%), chitinases (32.65% and 35.48%), and amylases (76.32% and 71.47%) (Table 1).

3.4. Plant Growth-Promoting Traits

Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production varied significantly between the two groups. Among Bacillus strains, 2BPP8 exhibited the highest production, reaching 95.44 µg/mL after 48 h, and 40.56 µg/mL after 168 h, outperforming the positive control (29.89 µg/mL). Moderate levels of IAA production were also observed in 4BPP4 and 4BPP8. In contrast, Actinomycete strains such as 5ACPP5, 5ACPP6, 4ACPP7, and 2ACPP2 produced even higher IAA concentrations than their positive control. Particularly, 5ACPP6 showed the highest IAA production among Actinomycetes (83.44 µg/mL at 96 h and 53.22 µg/mL at 168 h), suggesting a strong auxin-mediated growth-promoting potential (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quantitative assessment of Indoleacetic Acid production (µg/mL) up to 168 h in Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains.

Phosphate solubilization tests revealed a marked contrast between the two groups. None of the evaluated Bacillus strains were able to solubilize either dicalcium phosphate or tricalcium phosphate during the 30-day assay period. However, among Actinomycetes, only strain 5ACPP5 successfully solubilized both phosphate forms, achieving 120.6% solubilization efficiency for dicalcium phosphate and 122.34% for tricalcium phosphate at day 30. Although lower than the positive control, these results demonstrate a clear advantage of Actinomycetes, particularly 5ACPP5, in phosphate bioavailability enhancement (Table 3).

Table 3.

Phosphate solubilization efficiency (%) of strain 5ACPP5 compared to the positive control (C+) in liquid NBRIP medium supplemented with bi-calcium and tri-calcium phosphate.

Siderophore production was observed in all tested strains, but with distinct magnitudes between groups. In the Bacillus group, strain 4BPP8 produced the largest iron solubilization halo, reaching 254.55% efficiency after five days, surpassing the positive control (202.22%). But the group of Actinomycetes showed generally higher iron solubilization efficiency. Strain 5ACPP5 was the most effective, achieving 412.43% efficiency, followed by 2ACPP4 (406.76%) and ACPP3 (270.03%), highlighting their superior capability to mobilize iron under limited availability conditions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of iron solubilization efficiency for 120 h.

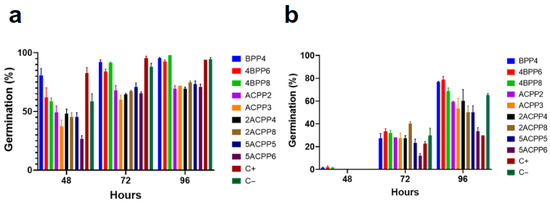

3.5. In Vitro Germination Assays

In tomato seeds, high germination rates were recorded for Bacillus strains, particularly 4BPP8 (98.00%) and BPP4 (95.33%) by day 4, both exceeding the negative control (94.00%) and outperforming all Actinomycete treatments. The strain 4BPP6 also showed strong germination stimulation, reinforcing the consistency of this group in solanaceous crops. Among Actinomycetes, moderate improvements were observed with 2ACPP8 (74.67%) and 5ACPP5 (73.33%), although performance remained lower than that of Bacillus strains (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Germination percentage of seeds of (a) tomato and (b) potato, after inoculation with Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains, evaluated over 4 days.

Potato seeds exhibited slower germination dynamics; however, marked improvements were observed in treatments with Bacillus. Strains 4BPP6 and BPP4 achieved germination rates of 78.67% and 76.67%, respectively, at 96 h. These values substantially exceeded the negative control (65.33%) and especially the positive control (30.00%), indicating the efficiency of bacterial inoculation even in physiologically dormant seeds. Among Actinomycetes, 2ACPP4 (60.00%) and ACPP2 (59.33%) presented the best performance, with 5ACPP5 reaching 50.00% (Figure 5b).

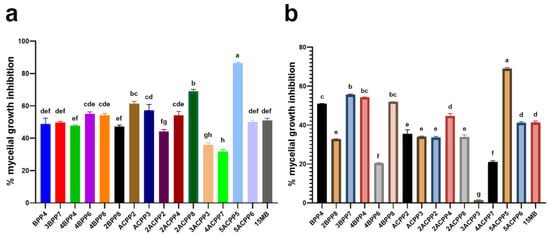

3.6. Antagonistic Activity Against Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternata

The antagonistic capacity of selected bacterial strains was evaluated through dual culture assays against two fungal pathogens of potato: Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternata. A total of 16 strains were selected based on their promising PGPR traits and enzymatic profiles, comprising eight Bacillus isolates (including positive control) and eight Actinomycetes. The extent of mycelial growth inhibition was recorded after 96 h and expressed as percentage reduction in fungal radial growth compared to the control (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Mean percentage of in vitro mycelial growth inhibition of Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains plus the positive control (15 MB) against (a) Rhizoctonia solani and (b) Alternaria alternata evaluated over 7 days. Treatments with different letters are statistically different from each other (p ≤ 0.05).

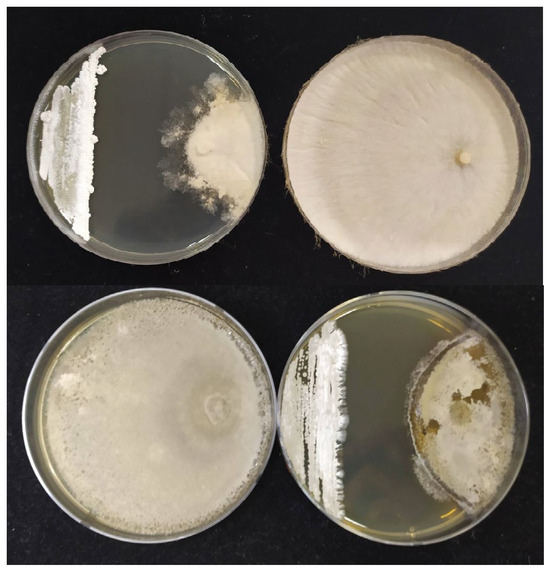

In assays against Rhizoctonia solani, significant inhibition was observed among Actinomycetes strains. The highest antagonistic effect was recorded for 5ACPP5 (86.45%), followed by 2ACPP8 (69.01%) and ACPP2 (61.31%). These strains also exhibited high IAA production and moderate chitinase activity, suggesting a potential synergistic role between metabolic traits and biocontrol efficacy. Among Bacillus, 4BPP6 and 4BPP8 demonstrated the most effective inhibition of R. solani (55.10% and 54.24%, respectively), accompanied by strong protease activity (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

In vitro mycelial growth inhibition activity of strain 5ACPP5 against Rhizoctonia solani at the top and Alternaria alternata at the bottom.

Against Alternaria alternata, lower inhibition percentages were recorded overall, reflecting potential variability in sensitivity between the fungal targets. Among Bacillus strains, BPP4 (50.99%), 3BPP7 (55.59%) and 4BPP4 (54.28%) showed the best results, even higher than almost all Actinomycetes strains, except 5ACPP5, which showed the highest percentage of inhibition (68.91%). These values align with prior observations indicating differential susceptibility of fungal species to bacterial antagonism, potentially linked to the presence or absence of specific hydrolytic enzymes such as chitinases (Figure 7).

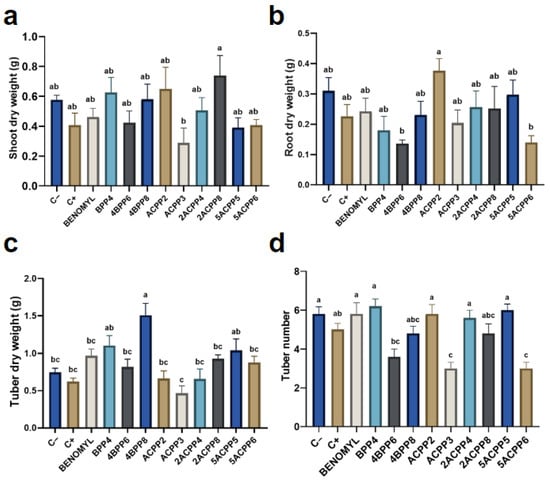

3.7. Greenhouse Evaluation of Biocontrol Potential

The biocontrol efficacy of selected bacterial strains against Rhizoctonia solani was evaluated under greenhouse conditions using true seeds of Solanum tuberosum (cv. Canchay × Ccompis). A total of nine strains were tested, including Bacillus isolates (BPP4, 4BPP6, 4BPP8) and Actinomycetes (ACPP2, ACPP3, 2ACPP4, 2ACPP8, 5ACPP5, 5ACPP6), alongside two controls: Benomyl (chemical fungicide, positive control) and sterile water (negative control).

Growth performance varied across treatments. The negative control recorded the highest fresh foliar biomass (5.06 g), followed closely by the Benomyl treatment (3.83 g). Most bacterial treatments exhibited intermediate values, with the Actinomycete strain ACPP3 presenting the lowest foliar biomass (0.98 g). Regarding dry foliar weight, the best-performing strain was 2ACPP8 (0.74 g), statistically similar to all treatments except ACPP3 (0.29 g), which again recorded the lowest value (Figure 8a).

Figure 8.

Effect of inoculated strains on growth-related variables: (a) shoot dry weight, (b) root dry weight, (c) tuber dry weight, (d) number of tubers. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p ≤ 0.05).

Root development results revealed significant differences. The strain 5ACPP5 achieved a high fresh root weight (2.74 g), closely matching the negative control (2.77 g), while the lowest value was observed for BPP4 (0.62 g). In terms of dry root biomass, ACPP2 led with 0.38 g, followed by negative control (0.31 g) and 5ACPP5 (0.29 g). Root length was highest in plants inoculated with ACPP2 (29 cm), whereas BPP4 and ACPP3 showed a shorter mean length of 22.5 cm and 21.6 cm, respectively (Figure 8b).

Tubers also responded positively to bacterial inoculation. The strain 4BPP8 produced the highest fresh (11.91 g) and dry (1.51 g) tuber weights, followed by 5ACPP5 and BPP4, which displayed statistically comparable values to those under chemical control. These three strains also achieved the highest number of tubers per plant, with BPP4 recording the top value of 6.2 tubers, suggesting a strong effect on reproductive development. In contrast, strains 5ACPP6 and ACPP3 produced the fewest tubers (3.0) and showed limited performance across most measured parameters (Figure 8).

Pathogenicity suppression was evaluated based on the presence and severity of stem canker caused by Rhizoctonia solani. Visual assessments confirmed that both BPP4 and 5ACPP5 significantly reduced lesion formation and damage severity, performing comparably to the Benomyl treatment. These observations further validated their in vitro antagonistic behavior and suggest consistent biocontrol efficacy across different experimental conditions.

3.8. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

All strains exhibited high sequence similarity (≥98%) to known species, allowing for confident taxonomic assignment.

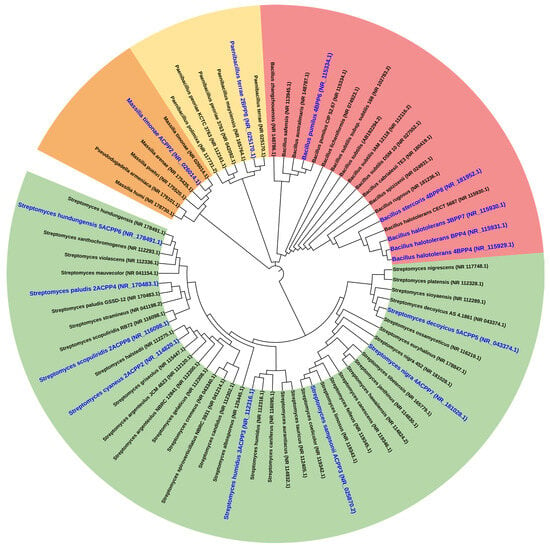

Among Bacillus isolates, strain BPP4 showed 100% identity with Bacillus halotolerans (NR_115931.1), and 3BPP7 and 4BPP4 also matched this species with complete identity. The strain 2BPP8 was identified as Paenibacillus terrae (99.36%), while 4BPP6 corresponded to Bacillus pumilus (99.85%), and 4BPP8 to Bacillus stercoris (99.70%). These results validate the phenotypic differentiation observed among isolates and confirm their placement within the Bacillaceae family (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of the novel strains with Bacillus and Actinomycetes strains. Colors represent different phylogenetic clades.

For Actinomycetes, the strain 5ACPP5—the most effective antagonist and PGPR candidate—was identified as Streptomyces decoyicus (99.85% identity; NR_043374.1). Additional Actinomycete strains matched other Streptomyces species, including S. sampsonii, S. paludis, S. scopuliridis, and S. humidus. These taxa are well-documented for their antibiotic and siderophore production, supporting their potential roles in plant-microbe interactions and disease suppression (Figure 9).

The resulting dendrogram clearly separated Bacillus and Streptomyces lineages into distinct clades, with high bootstrap support validating the taxonomic structure. Strains BPP4 and 5ACPP5 clustered with reference strains of their respective species, reinforcing their correct molecular identification.

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity and Adaptation of Native PGPR Isolated from Potato Agroecosystems

The isolation of seventy-one bacterial strains from potato plants cultivated across five agroecological regions of Peru confirms the remarkable microbial diversity present in both the rhizosphere and phyllosphere microhabitats of Solanum tuberosum. This richness is likely shaped by the wide environmental gradients in the Peruvian Andes and coast, which impose selective pressures that promote the emergence of ecologically adapted bacterial communities [44,45]. Similar microbial diversity in potato-associated bacteria has been reported by Sessitsch et al. [46] and Garcia-Serquen et al. [45], who demonstrated that rhizobacterial populations differ significantly across elevation gradients and soil types in potato-growing systems of the Andes [45,47,48].

Morphological and microscopic analyses in the present study confirmed the successful isolation of spore-forming Bacillus species and filamentous Actinomycetes, predominantly Streptomyces. Strains such as BPP4 and 4BPP6 presented typical Bacillus-like colony features, creamy, opaque colonies with undulate margins [49], while Actinomycetes such as 5ACPP5 exhibited dry, powdery, pigmented colonies and branched aerial mycelia consistent with the Streptomyces genus [50]. These traits are congruent with descriptions by Zhang et al. [51], who characterized potato-associated Streptomyces strains from Tibetan Plateau soils and found similar phenotypic diversity.

The phenotypic characterization under different temperature conditions revealed moderate psychrotolerance, particularly among Bacillus isolates. At 4 °C, strain 4BPP6 (Bacillus pumilus) achieved the highest growth, and other Bacillus strains such as BPP4 and 2BPP8 exhibited limited but measurable development. In contrast, Actinomycetes showed minimal growth at 4 °C, with only slight colony formation by strains such as 2ACPP8 and 5ACPP5. These findings align with prior studies suggesting that Bacillus spp. are better adapted to cold stress compared to Actinomycetes [52]. At 10 °C and 15 °C, improved growth was observed, especially in strains 3BPP7 and 4BPP8, demonstrating mesophilic adaptation [53] typical of PGPR adapted to Andean climates [54].

The pH tolerance assays demonstrated a broad adaptability among the isolates. While Actinomycetes showed restricted growth at pH 4, all Bacillus strains successfully established visible colonies greater than 6 mm in diameter under acidic conditions. At pH 5 and neutral pH 7, optimal colony expansion occurred across groups, with remarkable performance from strains such as 4BPP8 and 2ACPP2, the latter displaying nearly double the growth diameter compared to other strains at pH 7. Growth was moderately reduced at alkaline pH 9, although Bacillus strains 4BPP8 and 3BPP7, along with Actinomycetes 2ACPP2 and ACPP2, maintained good adaptability. This broad pH tolerance is a desirable trait for bioinoculants intended for application in Peruvian soils, which often exhibit variable pH profiles due to climatic and edaphic heterogeneity [46,55,56].

Adaptation to local conditions is essential for PGPR efficacy under field deployment. The ability of strains such as Bacillus halotolerans BPP4 and Streptomyces decoyicus 5ACPP5 to survive and remain metabolically active across a broad range of environmental parameters supports their candidacy as robust bioinoculants. Notably, B. halotolerans has been associated with high salt tolerance, antagonistic activity, and phytohormone production in previous studies [57,58,59]. Likewise, S. decoyicus and other Streptomyces spp. are recognized for their roles in soil health, pathogen suppression, and antibiotic biosynthesis, making them valuable components of plant-microbe consortia [60,61,62].

4.2. Enzymatic and Functional Traits Supporting Biocontrol Activity

The enzymatic profiles of the bacterial strains revealed important functional differences between Bacillus isolates and Actinomycetes, with direct implications for their potential use as biocontrol agents and soil health promoters. Among Bacillus strains, protease activity was widely observed, with strain 4BPP6 (Bacillus pumilus) exhibiting the highest activity, followed by 4BPP4 and 3BPP7. Conversely, BPP4 (Bacillus halotolerans), despite being one of the top-performing PGPR strains, showed relatively low protease production. These observations are consistent with previous reports that identified protease secretion as a primary biocontrol mechanism in Bacillus spp., especially in the suppression of fungal pathogens such as Rhizoctonia solani [63,64,65]. In contrast, Actinomycetes displayed a broader and more balanced enzymatic repertoire. Strain 2ACPP4 exhibited the highest protease activity among Actinomycetes, with ACPP2 also showing high activity levels. Interestingly, strain 5ACPP5 (Streptomyces decoyicus), despite its strong antagonistic capacity, lacked detectable protease activity, suggesting that other mechanisms, such as chitinase production and secondary metabolite secretion, might underpin its biocontrol performance [66,67,68].

Lipase production was more pronounced in Actinomycetes than in Bacillus strains. While Bacillus strain 2BPP8 showed the highest lipase activity among its group, Actinomycete strains 2ACPP8 and 2ACPP4 achieved substantially higher values in their group. This enhanced lipolytic capacity may contribute to membrane disruption of phytopathogenic fungi and improve competition for ecological niches [69].

Chitinase activity, critical for direct fungal cell wall degradation, was absent in all Bacillus isolates, whereas almost all Actinomycetes displayed detectable chitinase production, with 5ACPP5 being the most active producer. This finding highlights the superior mycolytic potential of Actinomycetes, a trait that has been extensively documented for Streptomyces spp. in biological control strategies [70,71,72].

Amylase activity, associated with starch hydrolysis and carbon acquisition in the rhizosphere, was notable in both groups but was generally higher among Actinomycetes. Strain BPP4 achieved the highest amylase activity among Bacillus isolates, followed by 2BPP8. Among Actinomycetes, strains ACPP2 and ACPP3 showed particularly high amylase production, reinforcing the broader catabolic versatility of this group [73,74].

Overall, the enzymatic profiles suggest that while Bacillus strains, particularly 4BPP6 and 4BPP4, excel in protease-mediated antagonism, Actinomycete strains such as 2ACPP4, 2ACPP8, and 5ACPP5 offer a more comprehensive enzymatic arsenal. This multifaceted functionality positions actinomycetes as highly competitive candidates for integrated biological control programs aimed at managing soil-borne fungal pathogens [75,76].

4.3. Plant Growth-Promoting Capacity and Germination Enhancement

The strains evaluated in this study exhibited a range of plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits that are fundamental to early plant development and yield performance. Among these, the production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), phosphate solubilization, and siderophore synthesis represent core mechanisms through which PGPR enhance plant nutrition and root architecture [22,77].

The ability of Bacillus strains such as BPP4 and 2BPP8 to synthesize high levels of IAA suggests a direct influence on root elongation and seedling vigour [34,78]. This aligns with prior findings by Idris et al. [79], who demonstrated that IAA-producing Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 significantly promoted root development in Arabidopsis and wheat by modulating endogenous auxin signaling pathways. Moreover, the Actinomycete strain 5ACPP5, though showing lower IAA levels (~40 µg/mL), maintained consistent PGP effects, reflecting a possible synergistic role of other metabolic pathways [75]. Despite high IAA production by these strains, their greenhouse performance in terms of root biomass was intermediate among tested strains. This may be due to strain-specific adaptation, microbial survival, or other PGPR characteristics as iron solubilization [80].

None of the strains showed phosphate solubilization, except 5ACPP5 from the Actinomycetes group. These findings emphasised the role of some Actinomycetes and Streptomyces spp. in the mobilisation of insoluble phosphates in a low-input agricultural system [81,82]. Phosphate availability is a key constraint in Andean soils due to fixation by aluminum and iron oxides, making these traits particularly relevant for Peruvian potato production systems.

Siderophore production, detected in both Bacillus and Streptomyces strains, adds a competitive advantage in iron-limited soils and indirectly contributes to pathogen suppression through nutrient sequestration. In particular, the strong CAS-positive reactions observed in BPP4 and 5ACPP5 are in line with studies by Dimkpa et al. [83], who found that siderophore-producing PGPR enhance nutrient uptake efficiency and systemic resistance in crops.

The observed PGP traits translated into improved germination rates in both tomato and potato seeds under in vitro conditions. Strains such as 4BPP8 and BPP4 reached germination rates over 90%, outperforming even the positive control and all Actinomycetes strains. These effects are comparable to those reported by Song et al. [84], who showed that Bacillus subtilis strain HS5B5 mitigated the inhibitory effects of NaCl stress on maize seed germination and seedling growth. For potato seeds, which tend to germinate slowly, strains BPP4 and 4BPP6 increased germination to over 76%, confirming their effectiveness even in species with physiological dormancy, better than that obtained with Actinomycetes strains. The ability of these native PGPR strains to simultaneously produce phytohormones, mobilize phosphorus, and chelate iron reflects their multifactorial mechanisms in promoting early plant development [85].

4.4. In Vitro and In Vivo Biocontrol Performance Against Fungal Pathogens

The dual antagonistic capacity of selected PGPR strains against Rhizoctonia solani and Alternaria alternata was demonstrated through in vitro and greenhouse assays. These results provide evidence of their biocontrol potential, particularly in systems where chemical fungicides are either ineffective or unsustainable. Furthermore, this bacterial trait allows promotion of sustainable agriculture free from the use of pesticides.

BPP4 and 4BPP8 displayed moderate inhibition rates in dual culture against R. solani and A. alternata among the Bacillus isolates. These values are comparable to the antagonistic performance of Bacillus velezensis and Bacillus subtilis strains reported by Chowdhury et al. [65], which inhibited various soil-borne pathogens through the combined action of lipopeptides and volatile compounds. The high efficacy of 4BPP8 may be attributed to the synergistic expression of protease, lipase, and siderophore pathways, which are well-documented mechanisms in Bacillus spp. for pathogen suppression [65,86,87].

In the case of Actinomycetes, strain 5ACPP5 (Streptomyces decoyicus) demonstrated the most consistent biocontrol performance across both pathogens, with the highest inhibition values against R. solani and A. alternata. These results align with those of Zhong et al. [88], who reported that Streptomyces olivoreticuli strain ZZ-21 shows potential as a biopesticide against tobacco target spot disease by inhibiting Rhizoctonia solani growth and altering its plasma membrane integrity. The presence of chitinase activity in 5ACPP5, combined with its ability to solubilize phosphate and produce siderophores, further supports its multifunctional role in pathogen suppression and nutrient cycling [67].

Greenhouse evaluations confirmed that strains BPP4, 5ACPP5, and 4BPP8 were not only effective in reducing stem canker symptoms caused by R. solani, but also contributed to improved plant biomass and tuber yield [78]. Similar outcomes were described by Ali et al. [89], who showed that Bacillus spp. volatiles show strong antimicrobial activity against Rhizoctonia solani and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice, with synthetic VOCs showing similar activity, and upregulating plant defense-related genes and antioxidant enzymes in rice plants. The comparable performance of these native strains to the commercial fungicide Benomyl reinforces their potential as natural alternatives within integrated pest management strategies [76].

In addition to direct pathogen inhibition, the PGPR strains may induce systemic resistance in the host plant. For example, Streptomyces species have been shown to trigger defense-related genes and prime host immunity through their secreted metabolites, as demonstrated by Vergnes et al. [90]. Although this mechanism was not evaluated in the current study, the strong biocontrol phenotypes observed suggest the possible involvement of both direct and indirect modes of action [52].

Together, the in vitro and in vivo data highlight the potential of Bacillus halotolerans BPP4 and Streptomyces decoyicus 5ACPP5 as components of biocontrol consortia for the management of fungal diseases in potato. Their consistent efficacy across systems, combined with their PGPR traits, underscores their value in developing low-input, environmentally sustainable crop protection solutions [27].

4.5. Taxonomic Identity and Biotechnological Potential of Selected Strains

The molecular identification of key bacterial isolates through 16S rRNA gene sequencing confirmed the taxonomic placement of the most effective strains within genera well-documented for their biocontrol and plant growth-promoting properties. Strain BPP4 exhibited 100% sequence identity with Bacillus halotolerans, a species increasingly recognized for its ecological plasticity and multifunctional agricultural applications [57,58]. Similarly, strain 5ACPP5 showed 99.85% similarity to Streptomyces decoyicus, positioning it within a genus renowned for its secondary metabolite diversity and symbiotic interactions in the rhizosphere [40,88].

The identification of BPP4 as B. halotolerans aligns with recent studies that highlighted the potential of Bacillus halotolerans strains as effective biocontrol agents and plant growth promoters. These endophytic bacteria exhibit strong antifungal activity against pathogens like Botrytis cinerea, reducing disease severity in various fruits [91,92]. B. halotolerans strains possess numerous secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters, producing compounds such as lipopeptides, bacillaene, and mojavensin A, which contribute to their antimicrobial properties [91]. Additionally, these bacteria can induce systemic resistance in plants by upregulating defense-related genes [58]. Some strains demonstrate remarkable stress tolerance, thriving in high salinity and alkaline conditions [93]. The application of B. halotolerans, either individually or in consortia, has been shown to enhance plant growth parameters in various species, including Arabidopsis and tomato [58,91]. These findings suggest that B. halotolerans strains are promising candidates for sustainable agriculture practices.

In the case of 5ACPP5, its identification as Streptomyces decoyicus adds to the expanding interest in the genus Streptomyces as a reservoir of novel bioactive compounds. Streptomyces species show significant potential as biocontrol agents against various plant pathogens, particularly fungal diseases like rice blast caused by Magnaporthe oryzae [94]. These bacteria produce diverse bioactive compounds that inhibit phytopathogens [95,96]. Studies have demonstrated Streptomyces effectiveness in reducing rice blast disease by up to 88.3% under greenhouse conditions [94]. They also show promise against Fusarium species, with field trials reporting reductions in Fusarium wilts by 0–55% [97]. The chitinolytic activity of Streptomyces strains plays a crucial role in biocontrol, and their plant growth promotion traits are beneficial [97]. However, the efficacy of Streptomyces as biocontrol agents can be influenced by environmental conditions and application methods [96]. Further research is needed to optimize isolation, formulation, and application techniques to fully exploit their potential in sustainable agriculture [96].

Altogether, the taxonomic confirmation of Bacillus halotolerans BPP4 and Streptomyces decoyicus 5ACPP5, combined with their functional performance, highlights their biotechnological potential as bioinoculants. Their native origin, environmental adaptability, and multifunctional traits offer a strategic advantage for use in the development of localized, sustainable solutions to improve potato health and productivity in the Peruvian Andes [54,98,99].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that potato-associated microbiomes from contrasting Peruvian agroecological zones harbor PGPR with robust and complementary functional traits. From a total of 71 isolates, obtained from rhizosphere (32) and phyllosphere (39) environments, strains belonging to Bacillus halotolerans (BPP4) and Streptomyces decoyicus (5ACPP5) emerged as the most promising candidates due to their dual capacity for promoting plant growth and suppressing fungal pathogens. Actinomycetes showed broader hydrolytic repertoires, with 5ACPP5 expressing the highest chitinase activity among its group (42.78%) and the strongest siderophore signal (412.43%), and uniquely solubilizing both di- and tri-calcium phosphate (120.6% and 122.34% efficiency at day 30). Within Bacillus, 2BPP8 reached the highest IAA level (95.44 µg mL−1 at 48 h), whereas 4BPP8 combined high siderophore efficiency (254.55% at 120 h) with strong germination promotion (tomato 98.0%; potato 78.67%). In vitro antagonism confirmed the biocontrol potential of 5ACPP5 against Rhizoctonia solani (86.45% inhibition) and Alternaria alternata (68.91%), while Bacillus strains were consistently effective against A. alternata (e.g., BPP4, 50.99%). Greenhouse validation corroborated these trends: 4BPP8 maximized tuber fresh weight (11.91 g plant−1) and 5ACPP5 enhanced root biomass and reduced stem canker severity to levels comparable to the chemical control. Collectively, these results indicate that B. halotolerans BPP4, B. stercoris 4BPP8, and S. decoyicus 5ACPP5 are promising bioinoculant components for potato, with complementary mechanisms, auxin biosynthesis, siderophore-mediated iron acquisition, phosphate solubilization, and mycolytic enzyme activity, likely underpinning their efficacy. Because some strong in vitro traits (e.g., high IAA in BPP4) did not always translate into superior greenhouse performance for all variables, next steps should prioritize formulation and delivery optimization, persistence and colonization studies, and multi-location field trials under farmer-relevant conditions. The native origin and environmental plasticity of these strains support their suitability for Andean production systems and provide a credible foundation for developing locally adapted, low-input biocontrol and biofertilization strategies for sustainable potato cultivation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/applmicrobiol6010002/s1, Table S1. Origin and Sample Type of Native Bacillus and Actinomycete Isolates from Potato in Peru; Table S2. Molecular identification of isolated strains; Figure S1. Gram staining of strain BPP4; Figure S2. Microculture microscopy of strain 5ACPP5; Figure S3. Canker stems observed on potato plants; Figure S4. Canker length and degree of damage on potato plant stems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.-R. and H.C.-S.; methodology, L.M.-R. and H.C.-S.; software, H.C.-S., R.R. and L.V.-A.; validation, L.M.-R. and H.C.-S.; formal analysis, H.C.-S. and L.V.-A.; investigation, L.M.-R. and H.C.-S.; resources, L.M.-R. and H.C.-S.; data curation, H.C.-S., R.R. and L.V.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.-R. and H.C.-S.; writing—review and editing, H.C.-S.; visualization, H.C.-S.; supervision, M.R.-R. and H.C.-S.; project administration, H.C.-S.; funding acquisition, M.R.-R. and H.C.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The National Institute of Agrarian Innovation (INIA), Peru, funded this research within the framework of the investment project “Improvement of agricultural research and technology transfer services at the El Chira—Marcavelica Agricultural Experimental Station in the Marcavelica District, Sullana Province, Piura Department”, with CUI No. 2472190.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zaeen, A.A.; Sharma, L.K.; Jasim, A.; Bali, S.; Buzza, A.; Alyokhin, A. Yield and Quality of Three Potato Cultivars under Series of Nitrogen Rates. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2020, 3, e20062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadu, T.; Abdullahi, A.; Ahmad, K. The Role of Crop Protection in Sustainable Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Production to Alleviate Global Starvation Problem: An Overview. In Solanum Tuberosum—A Promising Crop for Starvation Problem; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.-P.; Petsakos, A.; Kromann, P.; Gatto, M.; Okello, J.; Suarez, V.; Hareau, G. Global Food Security, Contributions from Sustainable Potato Agri-Food Systems. In The Potato Crop; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, H.E.; Walker, T.S.; Guimaraães, R.L.; Bais, H.P.; Vivanco, J.M. Andean Root and Tuber Crops: Underground Rainbows. HortScience 2003, 38, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, O.; Mares, V. The Historical, Social, and Economic Importance of the Potato Crop. In The Potato Genome; Chakrabarti, S.K., Xie, C., Tiwari, J.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz, G.; Miranda, T.Y.; Blas, R.H.; Neyra, E.; Orjeda, G. Simple Sequence Repeat-Based Genetic Diversity and Analysis of Molecular Variance among on-Farm Native Potato Landraces from the Influence Zone of Camisea Gas Project, Northern Ayacucho, Peru. Am. J. Potato Res. 2020, 97, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, S.; Núñez, J.; Bonierbale, M.; Ghislain, M. Multilevel Agrobiodiversity and Conservation of Andean Potatoes in Central Peru. Mt. Res. Dev. 2010, 30, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.J. Plants, People, and the Conservation of Biodiversity of Potatoes in Peru. Nat. Conserv. 2011, 9, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolf, B.; Andrade-Piedra, J.; Bittara Molina, F.; Przetakiewicz, J.; Hausladen, H.; Kromann, P.; Lees, A.; Lindqvist-Kreuze, H.; Perez, W.; Secor, G.A. Fungal, Oomycete, and Plasmodiophorid Diseases of Potato. In The Potato Crop; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 307–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kvasko, O.; Kolomiiets, Y.; Buziashvili, A.; Yemets, A. Biotechnological Approaches to Increase the Bacterial and Fungal Disease Resistance in Potato. Open Agric. J. 2022, 16, e187433152210070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiptoo, J.; Abbas, A.; Bhatti, A.M.; Usman, H.M.; Shad, M.A.; Umer, M.; Atiq, M.N.; Alam, S.M.; Ateeq, M.; Khan, M.; et al. Rhizoctonia Solani of Potato and Its Management: A Review. Plant Prot. 2021, 5, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Rashid, M.M.; Akhtar, N.; Muin, A.; Ahmad, G. In-Vitro Evaluation of Fungicides at Different Concentrations against Alternaria Solani Causing Early Blight of Potato. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 1874–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, D.L.; Gudmestad, N.C. Spatial and Temporal Sensitivity of Alternaria Species Associated with Potato Foliar Diseases to Demethylation Inhibiting and Anilino-Pyrimidine Fungicides. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsror, L.; Peretz-Alon, I. The Influence of the Inoculum Source of Rhizoctonia Solani on Development of Black Scurf on Potato. J. Phytopathol. 2005, 153, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S.; Pesaresi, P.; Mizzotti, C.; Bulone, V.; Mezzetti, B.; Baraldi, E.; Masiero, S. Game-Changing Alternatives to Conventional Fungicides: Small RNAs and Short Peptides. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ons, L.; Bylemans, D.; Thevissen, K.; Cammue, B.P.A. Combining Biocontrol Agents with Chemical Fungicides for Integrated Plant Fungal Disease Control. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Tarafdar, A.; Ghosh, R.; Gopalakrishanan, S. Biological Control as a Tool for Eco-Friendly Management of Plant Pathogens. In Advances in Soil Microbiology: Recent Trends and Future Prospects; Adhya, T., Mishra, B., Annapurna, K., Verma, D., Kumar, U., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 4, pp. 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gowtham, H.G.; Hema, P.; Murali, M.; Shilpa, N.; Nataraj, K.; Basavaraj, G.L.; Singh, S.B.; Aiyaz, M.; Udayashankar, A.C.; Amruthesh, K.N. Fungal Endophytes as Mitigators against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Crop Plants. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, M.S.; Roy, M.; Abbasi, P.A.; Carisse, O.; Yurgel, S.N.; Ali, S. Why Do We Need Alternative Methods for Fungal Disease Management in Plants? Plants 2023, 12, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahat, M.R.; Ahmed, A.A.; Enas, A.H.; Fekria, M.S. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria and Their Potential for Biocontrol of Phytopathogens. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 10, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyanthi, V.; Kanimozhi, S. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)—Prospective and Mechanisms: A Review. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 12, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Hameed, S.; Shahid, M.; Iqbal, M.; Lazarovits, G.; Imran, A. Functional Characterization of Potential PGPR Exhibiting Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 232, 126389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Iftikhar, Y.; Mubeen, M.; Ali, H.; Ahmad Zeshan, M.; Asad, Z.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Abdul Rehman, M.; Abbas, M.; Rafique, M.; et al. Antagonistic Potential of Bacterial Species against Fungal Plant Pathogens (FPP) and Their Role in Plant Growth Promotion (PGP): A Review. Phyton 2022, 91, 1859–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeysingha, S.; Walpola, B.C.; Kang, Y.-G.; Yoon, M.-H.; Oh, T.-K. Practical Significance of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria in Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 50, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Jiménez, A.; Castellanos-Hernández, O.; Acevedo-Hernández, G.; Aarland, R.C.; Rodríguez-Sahagún, A. Rhizospheric Bacteria with Potential Benefits in Agriculture. Adv. Mod. Agric. 2022, 3, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, W.K.; Raizada, M.N. Biodiversity of Genes Encoding Anti-Microbial Traits within Plant Associated Microbes. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Anand, G.; Gaur, R.; Yadav, D. Plant–Microbiome Interactions for Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, O.M.; Castrillo, G.; Herrera Paredes, S.; Salas González, I.; Dangl, J.L. Understanding and Exploiting Plant Beneficial Microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, U.; Rehmani, M.S.; Wang, L.; Luo, X.; Xian, B.; Wei, S.; Wang, G.; Shu, K. Toward a Molecular Understanding of Rhizosphere, Phyllosphere, and Spermosphere Interactions in Plant Growth and Stress Response. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2021, 40, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.C.; Razdan, N.; Saharan, K. Rhizospheric Microbiome: Bio-Based Emerging Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture Development and Future Perspectives. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 254, 126901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, F.; Maffia, L.A.; Mizubuti, E.S.G.; Teixeira, H. Biological Control of Coffee Rust by Antagonistic Bacteria under Field Conditions in Brazil. Biol. Control 2009, 49, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, T.D.; Sherpa, C.; Agrawal, V.P.; Lekhak, B. Isolation and Characterization of Antibacterial Actinomycetes from Soil Samples of Kalapatthar, Mount Everest Region. Nepal. J. Sci. Technol. 2009, 10, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergey, J.; Hendriks, D.; Holt, J. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology; Sneathy Stanley, J.T., Ed.; The Williams and Wilkins Co. Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, P.; Zúñiga, D. Physiological Characterization of Bacillus spp. Strains from Potato (Solanum tuberosum) Rhizosphere. Ecol. Apl. 2010, 9, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Espejo, C.N.; Mamani-Mamani, M.M.; Chávez-Lizárraga, G.A.; Álvarez-Aliaga, M.T. Evaluación de La Actividad Enzimática Del Trichoderma Inhamatum (BOL-12 QD) Como Posible Biocontrolador. J. Selva Andin. Res. Soc. 2016, 7, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza-Padilla, C.J.; Romero-Tabarez, M.; Orduz, S. Actividad Lipoítica de Microorganismos Aislados de Aguas Residuales Contaminadas Con Grasas. Biotecnol. En El Sect. Agropecu. Y Agroindustrial 2017, 15, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas-Junco, B.A.; Quero-Bautista, M.; Magaña-Sevilla, H.F.; Reyes-Ramírez, A. Selección de Cepas Nativas Con Actividad Quitino-Proteolítica de Bacillus sp. Aisladas de Suelos Tropicales. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol. 2009, 11, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Avalos-Zavaleta, R.; Llenque-Diaz, L.; Segura-Vega, R. Aislamiento y Selección de Cultivos Nativos de Bacillus sp. Productor de Amilasas a Partir de Residuos Amiláceos Del Mercado La Hermelinda, Trujillo, Perú. REBIOL 2016, 36, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Panchal, K.J. Identification of Cellulase Enzyme Involved in Biocontrol Activity. In Practical Handbook on Agricultural Microbiology; Humana Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishnan, H.; Shanmugaiah, V.; Balasubramanian, N.; Sharma, M.P.; Kotchoni, S.O. Antagonistic Potential of Native Strain Streptomyces aurantiogriseus VSMGT1014 against Sheath Blight of Rice Disease. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 3149–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nautiyal, C.S. An Efficient Microbiological Growth Medium for Screening Phosphate Solubilizing Microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 170, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.B.; Zuberer, D.A. Use of Chrome Azurol S Reagents to Evaluate Siderophore Production by Rhizosphere Bacteria. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1991, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, E.R.; Hebert, T.T. Métodos de Investigación Fitopatológica; Instituto Interamericano de Ciencias Agrícolas: San Jose, Costa Rica, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kiige, J.K.; Kavoo, A.M.; Mwajita, M.R.; Mogire, D.; Ogada, S.; Wekesa, T.B.; Kiirika, L.M. Metagenomic Characterization of Bacterial Abundance and Diversity in Potato Cyst Nematode Suppressive and Conducive Potato Rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Serquén, A.L.; Chumbe-Nolasco, L.D.; Navarrete, A.A.; Girón-Aguilar, R.C.; Gutiérrez-Reynoso, D.L. Traditional Potato Tillage Systems in the Peruvian Andes Impact Bacterial Diversity, Evenness, Community Composition, and Functions in Soil Microbiomes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessitsch, A.; Reiter, B.; Berg, G. Endophytic Bacterial Communities of Field-Grown Potato Plants and Their Plant-Growth-Promoting and Antagonistic Abilities. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004, 50, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S.; Mitter, B.; Oswald, A.; Schloter-Hai, B.; Schloter, M.; Declerck, S.; Sessitsch, A. Rhizosphere Microbiomes of Potato Cultivated in the High Andes Show Stable and Dynamic Core Microbiomes with Different Responses to Plant Development. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fiw242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussarrat, T.; Latorre, C.; Barros Santos, M.C.; Aguado-Norese, C.; Prigent, S.; Díaz, F.P.; Rolin, D.; González, M.; Müller, C.; Gutiérrez, R.A.; et al. Rhizochemistry and Soil Bacterial Community Are Tailored to Natural Stress Gradients. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2025, 202, 109662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.A.; Khaliq, S.; Ahmad, S.; Ashraf, N.; Ghauri, M.A.; Anwar, M.A.; Akhtar, K. Application of Combined Irradiation Mutagenesis Technique for Hyperproduction of Surfactin in Bacillus velezensis Strain AF_3B. Int. J. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 5570585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesugi, J.H.E.; dos Santos Caldas, D.; Coelho, B.B.F.; Prazes, M.C.C.; Omura, L.Y.E.; Pismel, J.A.R.; Bezerra, N.V. Morphological Diversity of Actinobacteria Isolated from Oil Palm Compost (Elaeis guineensis). Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tang, S.; Yang, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Chen, T.; Liu, G.; Dyson, P. Streptomyces dangxiongensis sp. Nov., Isolated from Soil of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 2729–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniyandi, S.A.; Yang, S.H.; Zhang, L.; Suh, J.-W. Effects of Actinobacteria on Plant Disease Suppression and Growth Promotion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9621–9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Santos Villalobos, S.; Robles, R.I.; Parra Cota, F.I.; Larsen, J.; Lozano, P.; Tiedje, J.M. Bacillus cabrialesii sp. Nov., an Endophytic Plant Growth Promoting Bacterium Isolated from Wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 3939–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Zúñiga, D. Characterization of Bacillus Isolates of Potato Rhizosphere from Andean Soils of Peru and Their Potential PGPR Characteristics. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, A.; Nagymáté, Z.; Romsics, C.; Vajna, B.; Tóth, E.; Lazanyi-Kovács, R.; Rizó, B.; Kutasi, J.; Bernhardt, B.; Farkas, É.; et al. Evaluating the Combined Effect of Biochar and PGPR Inoculants on the Bacterial Community in Acidic Sandy Soil. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2021, 160, 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.C.; Kitko, R.D.; Cleeton, S.H.; Lee, G.E.; Ugwu, C.S.; Jones, B.D.; BonDurant, S.S.; Slonczewski, J.L. Acid and Base Stress and Transcriptomic Responses in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, H. Whole-Genome Analysis Revealed the Growth-Promoting and Biological Control Mechanism of the Endophytic Bacterial Strain Bacillus halotolerans Q2H2, with Strong Antagonistic Activity in Potato Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1287921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalgatidou, P.C.; Thomloudi, E.-E.; Delis, C.; Nifakos, K.; Zambounis, A.; Venieraki, A.; Katinakis, P. Compatible Consortium of Endophytic Bacillus Halotolerans Strains Cal.l.30 and Cal.f.4 Promotes Plant Growth and Induces Systemic Resistance against Botrytis Cinerea. Biology 2023, 12, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, L.; Deng, J. Biocontrol Ability and Action Mechanism of Bacillus Halotolerans against Botrytis Cinerea Causing Grey Mould in Postharvest Strawberry Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 174, 111456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Safaie, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Shamsbakhsh, M. Streptomyces Strains Induce Resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici Race 3 in Tomato Through Different Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, R.M.; Ramos, L.M.; da Luz, L.A.; Almeida, R.N.; Lucas, A.M.; Cassel, E.; de Oliveira, S.D.; Astarita, L.V.; Santarém, E.R. Halotolerant Streptomyces spp. Induce Salt Tolerance in Maize through Systemic Induction of the Antioxidant System and Accumulation of Proline. Rhizosphere 2022, 24, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.; Gharanjik, S.; Koobaz, P.; Sadeghi, A. Plant Growth Promoting Streptomyces Strains Are Selectively Interacting with the Wheat Cultivars Especially in Saline Conditions. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contesini, F.J.; de Rodrigues, R.; Sato, H.H. An Overview of Bacillus Proteases: From Production to Application. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guleria, S.; Walia, A.; Chauhan, A.; Shirkot, C.K. Molecular Characterization of Alkaline Protease of Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens SP1 Involved in Biocontrol of Fusarium Oxysporum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 232, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.P.; Hartmann, A.; Gao, X.; Borriss, R. Biocontrol Mechanism by Root-Associated Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens FZB42—A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, E.; Saad, M.; Hassan, H.; Zeidan, E. Purification and Characterization of Alkaline Protease Produced by Streptomyces flavogriseus and Its Application as a Biocontrol Agent for Plant Pathogens. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2019, 18, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi-Zarandi, M.; Bonjar, G.H.S.; Riseh, R.S.; El-Shetehy, M.; Saadoun, I.; Barka, E.A. Exploring Two Streptomyces Species to Control Rhizoctonia solani in Tomato. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Esmail, G.A.; Ghilan, A.-K.M.; Arasu, M.V. Isolation and Screening of Streptomyces sp. Al-Dhabi-49 from the Environment of Saudi Arabia with Concomitant Production of Lipase and Protease in Submerged Fermentation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Choi, S.; Bui, D.-C.; Kim, J.-E.; Shin, J.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.J.; Lee, Y.-W.; et al. Genetic and Transcriptional Regulatory Mechanisms of Lipase Activity in the Plant Pathogenic Fungus Fusarium Graminearum. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e05285-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Deng, J.-J.; Mo, Z.-Q.; Zhang, M.-S.; Yang, Z.-D.; Zhang, J.-R.; Li, Y.-W.; Dan, X.-M.; Luo, X.-C. Synergic Chitin Degradation by Streptomyces sp. SCUT-3 Chitinases and Their Applications in Chitinous Waste Recycling and Pathogenic Fungi Biocontrol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, E.; Alabdalall, A.H.; Alghamdi, A.I.; Ababutain, I.M.; Aldakeel, S.A.; Al-Zuwaid, S.K.; Algarudi, B.M.; Algarudi, S.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Albarrag, A.M. Screening for Chitin Degrading Bacteria in the Environment of Saudi Arabia and Characterization of the Most Potent Chitinase from Streptomyces variabilis Am1. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaene, T.; Langendries, S.; Beirinckx, S.; Maes, M.; Goormachtig, S. Streptomyces as a Plant’s Best Friend? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, A.; Shehla, H.; Sheikh, H.; Hassan, M. Screening, Isolation, and Enzyme Kinetics of Bacterial Amylase Collected from Rhizosphere Soil. J. Sustain. Environ. 2023, 2, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashkandi, M.; Baz, L. Function of CAZymes Encoded by Highly Abundant Genes in Rhizosphere Microbiome of Moringa Oleifera. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olanrewaju, O.S.; Babalola, O.O. Streptomyces: Implications and Interactions in Plant Growth Promotion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Rodriguez, J.A.; Reyes-Pérez, J.J.; Quiñones-Aguilar, E.E.; Hernandez-Montiel, L.G. Actinomycete Potential as Biocontrol Agent of Phytopathogenic Fungi: Mechanisms, Source, and Applications. Plants 2022, 11, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.K.; Dheeman, S.; Agarwal, M. Phytohormone-Producing PGPR for Sustainable Agriculture. In Bacterial Metabolites in Sustainable Agroecosystem; Springer: London, UK, 2015; Volume 12, pp. 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sansinenea, E. Bacillus spp.: As Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria. In Secondary Metabolites of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizomicroorganisms: Discovery and Applications; Singh, H., Keswani, C., Reddy, M., Sansinenea, E., García-Estrada, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 225–237. ISBN 9789811358623. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, E.E.; Iglesias, D.J.; Talon, M.; Borriss, R. Tryptophan-Dependent Production of Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) Affects Level of Plant Growth Promotion by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, B.; Li, E.; Chen, S. Siderophore and Indolic Acid Production by Paenibacillus Triticisoli BJ-18 and Their Plant Growth-Promoting and Antimicrobe Abilities. PeerJ 2020, 2020, e9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouyia, F.E.; Romano, I.; Fechtali, T.; Fagnano, M.; Fiorentino, N.; Visconti, D.; Idbella, M.; Ventorino, V.; Pepe, O. P-Solubilizing Streptomyces roseocinereus MS1B15 with Multiple Plant Growth-Promoting Traits Enhance Barley Development and Regulate Rhizosphere Microbial Population. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouyia, F.E.; Ventorino, V.; Pepe, O. Diversity, Mechanisms and Beneficial Features of Phosphate-Solubilizing Streptomyces in Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1035358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.O.; Merten, D.; Svatoš, A.; Büchel, G.; Kothe, E. Metal-Induced Oxidative Stress Impacting Plant Growth in Contaminated Soil Is Alleviated by Microbial Siderophores. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhao, B.; Sun, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, C.; Zhang, J. Effects of Bacillus Subtilis HS5B5 on Maize Seed Germination and Seedling Growth under NaCl Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, D. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria-an Efficient Tool for Agriculture Promotion. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 2016, 4, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslennikova, V.S.; Tsvetkova, V.P.; Shelikhova, E.V.; Selyuk, M.P.; Alikina, T.Y.; Kabilov, M.R.; Dubovskiy, I.M. Bacillus Subtilis and Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens Mix Suppresses Rhizoctonia Disease and Improves Rhizosphere Microbiome, Growth and Yield of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.S. Bacillus spp.: A Bio-Inoculant Factory for Plant Growth Promotion and Immune Enhancement. Biofertilizers 2021, 1, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Sui, W.W.; Bai, X.Y.; Qiu, Z.L.; Li, X.G.; Zhu, J.Z. Characterization and Biocontrol Mechanism of Streptomyces olivoreticuli as a Potential Biocontrol Agent against Rhizoctonia Solani. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 197, 105681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Khan, A.R.; Tao, S.; Rajer, F.U.; Ayaz, M.; Abro, M.A.; Gu, Q.; Wu, H.; Kuptsov, V.; Kolomiets, E.; et al. Broad-spectrum Antagonistic Potential of Bacillus spp. Volatiles against Rhizoctonia solani and Xanthomonas oryzae Pv. oryzae. Physiol. Plant 2023, 175, e14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnes, S.; Gayrard, D.; Veyssière, M.; Toulotte, J.; Martinez, Y.; Dumont, V.; Bouchez, O.; Rey, T.; Dumas, B. Phyllosphere Colonization by a Soil Streptomyces sp. Promotes Plant Defense Responses Against Fungal Infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomloudi, E.-E.; Tsalgatidou, P.C.; Baira, E.; Papadimitriou, K.; Venieraki, A.; Katinakis, P. Genomic and Metabolomic Insights into Secondary Metabolites of the Novel Bacillus Halotolerans Hil4, an Endophyte with Promising Antagonistic Activity against Gray Mold and Plant Growth Promoting Potential. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalgatidou, P.C.; Thomloudi, E.-E.; Baira, E.; Papadimitriou, K.; Skagia, A.; Venieraki, A.; Katinakis, P. Integrated Genomic and Metabolomic Analysis Illuminates Key Secreted Metabolites Produced by the Novel Endophyte Bacillus Halotolerans Cal.l.30 Involved in Diverse Biological Control Activities. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Q.; Farzand, A.; Yang, X.; Semenov, M.; Borriss, R.; et al. Genomic Features and Molecular Function of a Novel Stress-Tolerant Bacillus Halotolerans Strain Isolated from an Extreme Environment. Biology 2021, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.W.-F.; Ser, H.-L.; Khan, T.M.; Chuah, L.-H.; Pusparajah, P.; Chan, K.-G.; Goh, B.-H.; Lee, L.-H. The Potential of Streptomyces as Biocontrol Agents against the Rice Blast Fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae (Pyricularia oryzae). Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Srivastava, S.; Karnwal, A.; Malik, T. Streptomyces as a Promising Biological Control Agents for Plant Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1285543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Streptomyces Strains and Their Metabolites for Biocontrol of Phytopathogens in Agriculture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 2077–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubici, G. Streptomyces spp. as Biocontrol Agents against Fusarium Species. CABI Rev. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, B.R.; Alori, E.T.; Kutu, R.F.; Babalola, O.O. Potentials of Microbial Inoculants in Soil Productivity: An Outlook on African Legumes. In Microorganisms for Green Revolution. Microorganisms for Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 53–75. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/PAVSNNR201813050 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Adeniji, A.; Fadiji, A.E.; Li, S.; Guo, R. From Lab Bench to Farmers’ Fields: Co-Creating Microbial Inoculants with Farmers Input. Rhizosphere 2024, 31, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |