Abstract

The concept of using ‘acid-adapted’ challenge cultures in the microbial validation of food processes that incorporate an acidic treatment is that they would be more resistant to acid and require a robust process to obtain targeted log reductions. The recent confirmation that acid-adapted Salmonella challenge cultures for droëwors and biltong processes are more sensitive to those processes than non-adapted cultures changes that preference for the use of non-adapted cultures for validation studies with these specific processes. However, it is difficult to achieve > 5-log reductions with non-adapted cultures, one of two USDA-FSIS parameters available for validation of processes that are not aligned with traditional process conditions for dried beef products in the USA (i.e., beef jerky). A natural multipurpose (flavor, antimicrobial) commercial product, described as a refined liquid smoke flavorant, provided >7-log reductions with droëwors when challenged with non-adapted cultures of Salmonella (5-serovar mixture), Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC, four-strain mixture), and Listeria monocytogenes (four-strain mixture) as well as a >7-log reduction with biltong processing (vs Salmonella). Comparisons between standard droëwors and biltong processes (all <5-log reductions) using non-adapted challenge cultures vs. the same formulation plus 0.75% pyrolyzed liquid smoke extracts (Flavoset) showed greater and significant (p < 0.05) reductions in duplicate trials with triplicate samples at each sampling point in each trial (total n = 6) when analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA). Although sold as a flavorant, this study examines the antimicrobial properties of Flavoset 5400L to improve the safety of droëwors and biltong by achieving a >5-log reduction with non-adapted pathogenic challenge cultures. Validation processes for droëwors and biltong established with these parameters should result in greater safety of marinaded, non-thermally processed meats from traditional foodborne pathogens commonly associated with meats or meat processing environments.

1. Introduction

Dried beef products are popular snack foods in many countries, especially among young and health-conscious consumers. These products are shelf-stable, portable, and an excellent source of protein. Recently, traditional South African air-dried beef products such as biltong and droëwors have attracted attention in United States because of their nutritional and health benefits [1,2,3] and forecasts expect a compound annual growth rate of 8.5% from 2025 through 2033 [3,4]. These ready to eat (RTE) meat products are distinct from traditional U.S. dried meat (beef jerky) because they follow different processing techniques. Beef jerky is a cooked product available under a variety of flavors and readily found in convenience stores and supermarkets. Beef jerky undergoes thermal processing inside sealed ovens operating above 62.5 °C (145 °F) with a relative humidity of more than 90% for a portion of total heating time. Biltong and droëwors, however, avoid heat treatment during production but undergo drying at room temperatures between 21.1 and 26.7 °C (70–80 °F) and 50 and 55% relative humidity (RH) levels. Hence, manufacturers of these products cannot rely upon the U.S Department of Agriculture-Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) guidelines for dried beef products [5]. USDA-FSIS requires that any alternative processing method in the U.S needs validation through peer-reviewed studies or third-party laboratory validation to show effective pathogen reduction. Accordingly, USDA-FSIS presents two compliance options: Option one requires manufacturers to perform testing for Salmonella (and be negative) on each lot of ingredients and use a process that achieves at least a 2-log reduction in Salmonella. Option two requires that the processing demonstrate a ≥5-log reduction in Salmonella without need for testing for Salmonella. The first option imposes significant economic challenges when there is non-compliance or test omission, but the second approach offers a more simple, yet technically demanding process for validation of the air-dried beef products and is the preferred option if reduction levels can be achieved [5,6].

Research has been conducted on the validation of the biltong process with a focus on improving reduction in foodborne pathogens to increase safety and satisfy US regulatory concerns. Biltong, made from vacuum-tumbled, marinated lean beef, was shown to reduce pathogenic microorganisms by ≥5 logs, including Salmonella serovars, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus [7,8]. Furthermore, this reduction was also obtained when replacing sodium chloride-based marinade systems with alternative salt formulations using potassium and calcium chloride, indicating the potential for low-sodium alternatives. Importantly, S. aureus did not make enterotoxins under the conditions of the biltong process, which includes low water activity, acidified marinade, high salt, and desiccation, despite its known ability to do so in other low-moisture environments [7]. The pathogens used in these works were ‘acid-adapted’ by culturing pathogens in broth media containing 1% glucose so they would ferment and acidify the media to pH ~ 4.8 so that challenge cultures used in process validation would not easily succumb to acidic treatment, requiring a robust process to ensure adequate log reduction. The call for acid-adapted challenge cultures may have developed from the convergence of research showing acid tolerance in Salmonella and STEC E. coli (GAD; [9]) and the numerous applications using simple acidic antimicrobial sprays/dips for carcasses and beef cuts. This concept was supported by various studies touting the benefits of acid adaptation of challenge cultures to induce acid tolerance [9,10,11,12,13], recommended by the National Advisory Committee on Microbial Criteria for Foods (NACMCF) [14], and adopted by both USDA-FSIS and FDA for use in validation studies of meat processes subjected to acidic treatments [15,16].

Recently, we examined the use of acid-adapted vs. non-adapted strains of 6 Salmonella serovars as the ‘challenge inoculum’ in air-dried beef such as biltong and droëwors [15]. The intention was to validate that acid-adapted cultures would be more resistant to acidic process treatments and therefore to the process (i.e., biltong, droëwors), requiring more robust conditions to provide adequate reduction in the pathogen of concern. However, the opposite was observed, that using acid-adapted Salmonella (6 serovars) led to increased sensitivity of Salmonella to either process providing greater reductions than when non-adapted cultures were employed providing new evidence that challenges an existing regulatory practice. Further, droëwors are beef sticks made from ground beef and marinade ingredients that are stuffed into casings and dried, which distributes marinade components and any contaminating microorganisms uniformly through the product matrix, coating them in protein and fat. Droëwors product format makes microbial inactivation more difficult than for whole-muscle biltong where inhibitory marinade components and contamination are concentrated at the surface and where the greatest desiccation occurs.

As droëwors and biltong continue to gain market interest [3,4], research is needed to determine whether validated biltong processing methods can be effectively applied to this more complex product or whether new antimicrobial intervention strategies must be developed to meet USDA-FSIS compliance standards for air-dried meat products like droëwors. Droëwors and biltong have been designated as ‘knowledge gap’ areas having validation challenges needing research support from the USDA-FSIS [17]. Ingredients may be added to meat products if they are approved by the FDA as safe and by the USDA-FSIS as having ‘efficacy’ in the purpose intended. Numerous ingredients that have been approved by the USDA-FSIS are found in the declared ‘list of suitable ingredients for meat and poultry products’ [18]. Among these are multi-functional natural ingredients, some of which have overlapping flavor and antimicrobial activities. In this study, we have examined the use of a commercial pyrolyzed and refined liquid smoke flavorant for its antimicrobial activity in air-dried beef (biltong, droëwors) processing to achieve a >5-log reduction in Salmonella in spite of using non-acid-adapted cultures to produce safe air-dried beef products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Growth and Storage Conditions, and Inoculum Preparation

Bacterial cultures were inoculated from frozen stocks into 9 mL tubes in Tryptic Soy Broth without dextrose (TSB, BD Bacto, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) overnight at 37 °C (Salmonella, E. coli) or 30 °C (L. monocytogenes). Cultures were maintained for storage by centrifugation (6000× g, 5 °C) and cell pellets were resuspended in 2–4 mL of fresh sterile TSB containing 15% glycerol + 1% trehalose. Cell suspensions were placed in glass vials and stored as frozen stocks in an ultra-low freezer (−80 °C; Sanyo Fisher Ultra Low Freezer VIP series). Frozen stocks were revived by transferring 100 µL of partially thawed cell suspension into 9 mL of TSB, incubating overnight at 37 °C or 30 °C, and sub-cultured again before use. Microbial enumeration for all assays was carried out on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA, BD Bacto; 1.5% agar) containing antibiotics specific to the particular pathogen and plated in duplicate.

Salmonella serovars used in this study included: Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Enteritidis H3527 (phage type 13a, clinical isolate), Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Thompson 120 (chicken isolate), Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Heidelberg F5038BG1 (ham isolate), Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium H3380 (DT 104 clinical isolate), and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Hadar MF60404 (turkey isolate). These strains have been used in many research publications involving antimicrobial interventions against Salmonella [8,15,19,20,21,22,23]. They are resistant to spectinomycin (5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), clindamycin (5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), and novobiocin (50 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and were plated on Selenite Cystine agar (SCA; [23]) containing these antibiotics. Strains of E. coli O157:H7 included ATCC 35150, ATCC 43894, ATCC 43889, and ATCC 45756 that are known for acid tolerance [24]. These strains were all resistant to 5 µg/mL novobiocin and 2.5 µg/mL rifamycin S/V (Sigma-Aldrich) and enumeration of these strains was conducted on TSA (BD Difco) containing these antibiotics. Strains of L. monocytogenes included ATCC 49594 (Scott A-2, serotype 4b, human isolate), V7-2 (serotype 1/2a, milk isolate), 39-2 (retail hotdog isolate), and 383-2 (ground beef isolate) [21]. These strains were resistant to streptomycin (100 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and rifamycin S/V (10 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and were plated on TSA (BD Difco) containing these antibiotics.

For meat inoculum preparation, 200 mL of individual cultures were grown in TSB without dextrose and harvested by centrifugation (8000 RPM), decanted, pellets resuspended with 6–8 mL of 0.1% buffered peptone water (BPW, BD), and held on ice until needed (i.e., 1–3 h). An equal volume of each culture was then combined to form a 5-serovar (Salmonella) or a 4-strain (E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes) cocktail. The mixture was held on ice until needed.

In prior studies with biltong processing, we used ‘acid-adapted’ cultures as specified by USDA-FSIS, the regulatory agency in charge of approving compliance of manufacturing processes based on recommendations by a white paper on challenge studies by the National Advisory Committee on Microbial Criteria for Foods [14]. The idea was to build tolerance to acid so that when the challenge cultures are exposed to acid treatment during processing, they are not easily inhibited, requiring that the process be sufficiently robust to inhibit even acid-adapted or acid-tolerant cultures. We recently compared acid-adapted vs. non-adapted cultures in biltong and droëwors processing and found that surprisingly, acid-adapted challenge cultures (i.e., Salmonella) are more sensitive to biltong/droëwors processing conditions than when using non-adapted cultures, which runs opposite of what was originally thought [15]. Therefore, we have decided to carry out these droëwors experiments with non-adapted cultures.

2.2. Beef Preparation, Inoculation, Marinade Seasoning, and Processing

2.2.1. Beef Preparation

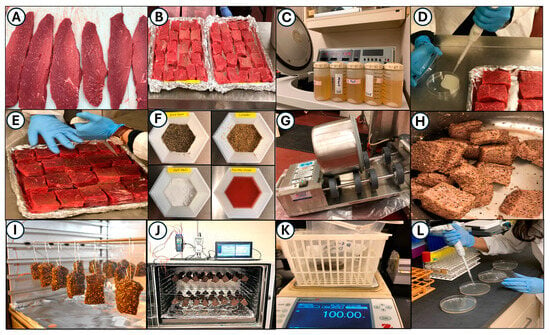

Boneless beef bottom rounds were obtained from Ralph’s Packing Co. (Perkins, OK, USA), who acquires beef from various sources via a beef broker and processed in the Robert M. Kerr Food and Agricultural Products Center (FAPC; Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA). Boneless beef rounds, or outside/bottom rounds, were select grade or ungraded, as per USDA Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications 171B [25] (Figure 1A). The vacuum-packaged beef was held at (35 °F/1.7 °C) in our meat pilot plant coolers when received and then trimmed prior to use (Figure 1B–D). Trimmed beef was held overnight at 5 °C (41 °F) to facilitate droëwors or biltong processing the next morning. Droëwors ingredient formulation was based on averaging of 8–10 ingredient compositions posted on popular biltong/droëwors sites on the internet. Beef fat (8%) was obtained from our abattoir meat-processing facility or recovered as trimmings from beef bottom rounds (Figure 1C,D). The remainder of ingredients and percent relative to total beef/fat were 100-grain red wine vinegar (3.9%), salt (2%), coriander (0.63%), black pepper (0.32%), and water + bacterial culture (2.50%). Our total batch weights after addition of all ingredients were approximately 1400–1500 g.

Figure 1.

Processing of air-dried droëwors sausage links. Panels: (A) bottom round fresh beef; (B) trimmed of fat; (C) sectioned into large beef pieces and fat pieces; (D) beef and fat cubed into smaller pieces; (E) growth and centrifugation of challenge cultures; (F) addition of challenge culture mixture onto beef/fat pieces followed by tumbling to insure distribution (G); (H) addition of salt, pepper, coriander, and red wine vinegar onto inoculated beef/fat followed by more tumbling to mix; (I) first grind followed by (J) simultaneous second grind and stuffing into collagen casings; (K) weighing droëwors sausage links and (L) placing them in drying oven; (M) wires for manual 4-channel temperature data logger (2 probes into sausages, 2 probes for recording chamber temperature) and sensor/cord for relative humidity meter.

2.2.2. Beef Inoculation and Marination

Beef and fat were added to a chilled stainless-steel Biro VTS-43 vacuum tumbler chamber (Biro, Marblehead, OH, USA) with sufficient 5-serovar mixed Salmonella inoculum (~1 × 1010 CFU/mL) to achieve ~1 × 107 CFU/gm in the ground beef. This beef/fat/culture was tumbled on the meat/fat components for 10 min to allow bacterial dispersion on their surfaces to resemble a situation mimicking contaminated beef. The vacuum tumbler was stopped, the chamber opened, and the marinade components (salt, pepper, coriander, water, and vinegar) were added and vacuum-tumbling (381 mm Hg) resumed for 30 min. When extracts of refined liquid smoke extract (Flavoset 5400L, Kerry, Beloit, WI, USA) were added for flavor enhancement and antimicrobial activity, the volume added was used to displace some of the water that was added. Similar culture inoculation and handling was performed with L. monocytogenes and E. coli O157:H7 droëwors processing.

2.3. Droëwors Beef Stick Processing

After tumbling, the beef was ground in a LEM (West Chester, OH, USA) meat grinder with an 8 mm grinder plate perforation. The grinder was cleaned up of loose beef, and the plate was replaced with a 10 mm grinding plate perforation leading directly to a 12-mm stuffing horn with 17 mm collagen casings (Ralph’s Packing Co., Perkins, OK, USA). Sausage links were tied with string at approximately 6 in length, individually weighed/recorded, and refrigerated until all were ready to be placed in the humidity-controlled oven (Hotpack, Warminster, PA, USA).

2.4. Biltong Processing

The biltong process was performed as described previously [7,8,26]. Briefly, the same beef bottom rounds used for droëwors were used for biltong to fabricate beef pieces (~ 3.0 × 2.0 × 0.63-inches; approximately 100-gm each; 20–22 pieces/trial). The beef pieces were placed on foil-lined trays, inoculated on both sides with 150 μL of inoculum (~1010 CFU/mL) spread with a gloved finger, and placed in a refrigerator for 30 min to promote attachment. Beef pieces were then transferred to a chilled stainless steel tumbler chamber where they were marinaded in a similar composition to that used for droëwors (beef, 92%; salt, 2.1%; black pepper, 0.8%, coriander, 1.1%; 100-grain red wine vinegar, 4%) and tumbled for 30 min [8]. The beef pieces were then hung in a drying oven set at 23.9 °C (75 °F) and 55% relative humidity (RH). Samples (i.e., 3 per sampling time) were retrieved for microbial enumeration at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days. Moisture loss, if needed, was determined from initial and final weights of individual beef pieces.

2.5. Quantifying Process Parameters

2.5.1. Temperature and Humidity

Oven chamber temperature was measured using a 4-thermocouple handheld temperature monitor (Center 378, New Taipei City, Taiwan); 2 thermocouples were placed hanging at different points in the chamber and 2 were placed in either biltong (Figure 2I,J) or individual droëwors sausages (Figure 1L,M; Figure 3A) depending on what was being processed”. Although the humidity oven has its own temperature and humidity probes, these are strangely placed behind a side panel and outer wall; we prefer to measure temperature and humidity readings made directly in the oven chamber as there is often a slight difference between the chamber and inside wall temperature and humidity readings.

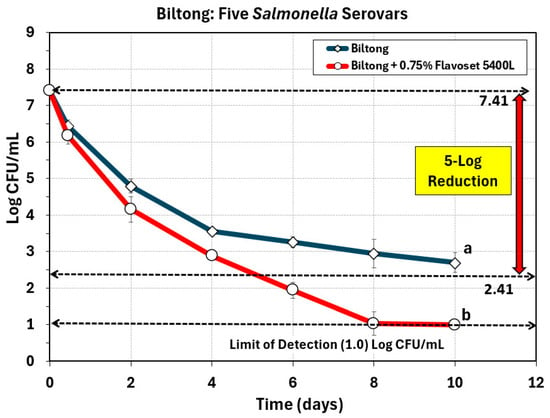

Figure 2.

Processing of biltong air-dried beef. Panels: (A) sliced bottom rounds; (B) sectioned slices into rectangular beef pieces; (C) harvesting bacterial inoculum; (D,E) inoculating beef pieces and spreading with a gloved finger; (F) ingredients for the marinade; (G) tumbling to mix; (H) after tumbling with marinade; (I) biltong hanging in drying oven; (J) drying oven with 4-channel temperature recorder and separate humidity/temperature recorder on top; (K) weighing standardized diluent for stomaching/resuspending surviving bacteria; (L) plating dilutions of diluent for microbial quantification.

Figure 3.

Measuring processing parameters for droëwors sausage links. Panels: (A) handheld temperature and humidity data loggers with laptop; (B) ground droëwors sausage samples for pH and salt determination; (C) blenders with steel blades for grinding droëwors sausages; (D) solid state salt meter for determining salt concentrations; (E,F) pH meter for raw and dried ground beef pH measurements; (G) Rotronic USB water activity meter, laptop with software, and sample cups for water activity; (H) raw ground beef in sample cups; (I) dried droëwors sausage links whole and (J) sectioned into sampling cups with the interior sides facing up.

2.5.2. Salt

Following drying, droëwors sausages were ground using a laboratory blender (Waring, New Harford, CT, USA) until homogenous as fine ground particles (Figure 3B,C). Five (5) g of the finely ground droëwors beef was weighed out and brought up to 100 g with distilled water in a filter-stomacher bag and macerated in a paddle mixer (IUL instruments) to thoroughly mix the sample and solubilize the salt. A Horiba LAQUA Pocket Ion Meter (Horiba Instruments, Irvine, CA, USA) was used for NaCl quantitation standardized with 0.5% and 5.0% NaCl standards (Figure 2D). Following the manufacturer’s instructions, 300 μL of the dilution water in the mixed sample was placed into the sensor chamber and readings were obtained (% NaCl) when stabilized and multiplied by the dilution of the ground sample. Readings were taken for triplicate samples at each trial sampling period. To determine the salt concentration in the droëwors sausage, the following was used:

2.5.3. pH

Sample pH was obtained from the droëwors sausage samples that were ground and paddle-blended in de-ionized water as used for the salt concentrations. The lack of buffering capacity of the de-ionized water did not affect the pH of the droëwors sausage. The pH meter (Accumet Research, AR25, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was standardized with pH 4.0 and 7.0 buffers as the droëwors pH was expected to be within this pH range (Figure 3E,F). As with the salt concentrations, pH was obtained with triplicate samples taken at each sampling period.

2.5.4. Water Activity

Water activity was measured using a HC2-AW-USB portable USB probe with direct PC interface and HW4-P-Quick software (Rotronic Corp., Hauppauge, NY, USA) (Figure 3G). Samples for water activity, pH, NaCl concentration, and moisture loss were obtained using un-inoculated beef for safety issues. Water activity was obtained either directly after grinding (day 0; Figure 3H) or upon removal from casings at various periods during the drying process (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days). For droëwors sausages, segments of sausage were peeled and casing removed, then sliced in half lengthwise with the internal surfaces positioned upwards (towards the humidity sensor); additional pieces were positioned to fill the space in the sampling cups also with internal sections facing upwards (Figure 3I,J).

2.5.5. Moisture Loss

Moisture loss was determined by weighing droëwors sausages prior to drying (initial weights) and then again upon removal from the drying oven to determine moisture loss at those specific time periods (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days; n = 6 per sampling period).

Comparison of latter weights to initial weights of the same pieces resulted in determination of % moisture loss as shown in Equation (2):

2.6. Microbial Sampling

The concern in microbial plating to determine process lethality of droëwors (or biltong) samples is that enumeration based on CFU/gm will be incorrect because the log reduction due to process lethality competes with microbial concentration due to moisture loss; these two opposing conditions occur simultaneously during processing. In order to remove microbial concentration effects due to sample moisture loss, we performed microbial dilutions relative to the initial weight of the product.

Raw droëwors beef stick sausages and biltong were weighed initially and then again at the time of sampling. Dilution of samples was made to correlate to the initial weight of individual droëwors sausages or biltong beef pieces. This allowed us to eliminate the conflicting impact of microbial concentration (due to 60–65% moisture loss) and microbial reduction (due to process conditions) that occur simultaneously and would lead to enumeration errors had we quantified on a per gram basis after moisture loss had occurred. Droëwors samples were placed in sterile stainless steel blender cups followed by the addition of chilled 1% neutralizing buffered peptone water (nBPW, Criterion, Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA, USA) based on initial day, pre-dried sample weight; additional diluent was added to make up for loss from drying compared to initial weight. Following blending in diluent, samples were transferred to a filter-stomacher bag and stomached for 60 s in a masticator paddle-blender (IUL Instruments, Barcelona, Spain). The filter bag dilution (stomached sample) was considered the 100 dilution for all samplings, including the initially inoculated raw beef through the final samples at up to 8–10 days of drying so that microbial counts were directly comparable with each other at all stages of drying. After stomaching in 1% nBPW, inoculated (experimental) and non-inoculated (negative control), samples were 10-fold serially diluted with 0.1% BPW. Dilutions were then surface-plated (0.1 mL) in duplicate on TSA/SCA containing appropriate antibiotics for the specific challenge organism and incubated at 30–37 °C for 48 h before enumeration. In a prior study, SCA was shown to enumerate these same non-adapted Salmonella serovars comparably to TSA, even after exposure to different types of stress [15]. When microbial counts were expected to be low, 0.2 mL was plated on each of 5 plates (1 mL total) to increase the sensitivity of plating, lowering the limit of detection (LOD). Biltong beef samples were treated similarly to droëwors; each sample was weighed before placement in the humidity oven and dilutions of retrieved samples were made based on their initial weights rather than on dried weights, allowing for direct comparison of microbial counts without the effects of moisture loss.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Trials were performed in duplicate replication with 3 samples tested per sampling period within each trial (n = 6). This is in accordance with validation criteria established by the NACMCF and accepted by the USDA-FSIS [14]. Replications were performed as separate experiments using meat sourced from different animals and randomly obtained from different sources. The data are presented as the mean of multiple replications. Data values represent mean counts across replicates and trials (i.e., data was averaged within trials and then averaged across trials); variation represented by standard deviation of the mean between trials was presented as error bars [14,27,28,29,30]. Statistical analysis was performed with SigmaPlot ver. 13 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA), data passed Normality and Equal Variance, and the Holm–Sidak test was used for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatments. Data treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05); treatments with the same letter are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Droëwors: Reduction in Salmonella Serovars Using Pyrolyzed Liquid Smoke Extracts as Flavoring and Antimicrobial

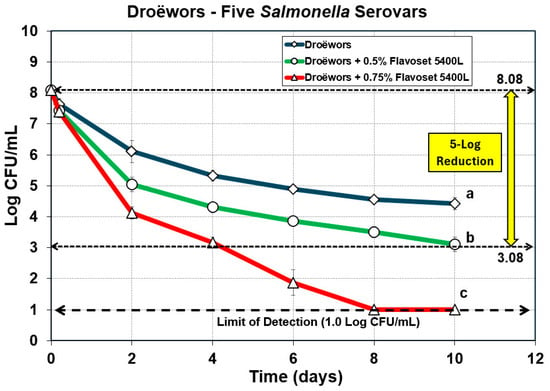

The droëwors process was validated for efficacy against five serovars (mixed) of Salmonella, whereby pyrolyzed extracts were added to the marinade at 0.5% and 0.75% of total product composition (i.e., marinade + meat ingredients) and compared to the droëwors process without the added extract. A prior trial with the standard marinade formulation or one including 0.3% Flavoset did not achieve the targeted 5-log reduction with Salmonella prompting us to increase levels in subsequent trials. The data shows that non-adapted Salmonella with just the standard marinade formulation achieved approximately a 3.5-log reduction while droëwors with 0.5% and 0.75% of the Flavoset plant extract added to the marinade mixture demonstrated 4.9-log and >7-log reductions, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Droëwors process against five serovar mixture of Salmonella without added Flavoset extract (open diamond symbols) versus droëwors made with 0.5% (open circles) and 0.75% (open triangles) Flavoset extract. Treatments were analyzed by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). The limit of detection (LOD) was established at 1 log CFU/mL by plating 1 mL of dilution instead of 0.1 mL when low levels were expected from prior day sample data.

3.2. Droëwors: Reduction in E. coli O157:H7 Using Pyrolyzed Liquid Smoke Extracts as Flavoring and Antimicrobial

Demonstration of 5-log reductions was sufficient for USDA-FSIS to approve the process for safety based on sufficient log reduction against a pathogen of concern (i.e., Salmonella). However, food safety managers of major supermarket clients who purchase biltong and droëwors often require additional proof of process and product safety against other potential foodborne pathogens. We therefore examined additional foodborne pathogens typically associated with raw beef and/or meat processing facilities. We examined Flavoset 5400L against four strains of E. coli O157:H7 that were known as being acid tolerant and had a history of experimental use with antimicrobials. The data shows that inclusion of Flavoset 5400L provided a >7-log reduction in a four-strain mixture of E. coli O157:H7 strains in 10 days when 0.75% Flavoset 5400L was included in the marinade, while achieving only a 4.5 log-reduction without the added ingredient (Figure 5). Given the level of reduction obtained for E. coli O157:H7, it is likely that even 0.35–0.5% Flavoset 5400L may easily achieve the 5-log reduction target.

Figure 5.

Droëwors process against four-strain mixture of E. coli O157:H7 ATCC strains without added Flavoset extract (diamond symbols) versus droëwors made with 0.75% (circles) Flavoset extract. Treatments were analyzed by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). The Limit of Detection (LOD) was established at 1 log CFU/mL by plating 1 mL of dilution instead of 0.1 mL when low levels were expected from prior sample data.

3.3. Droëwors: Reduction in Listeria Monocytogenes Using Pyrolyzed Liquid Smoke Extracts as Flavoring and Antimicrobial

Listeria monocytogenes has been a significant problem with meat processing plants as implicated with past and recent recalls, outbreaks, and deaths associated with consumption of contaminated food [31,32]. Much of this stems from the ability of many strains which have strong adherence properties to surfaces that can initiate biofilm formation that leads to persistence in meat processing plants. The best approach against L. monocytogenes contamination of food products is a program targeting biofilm formation/survival in plant facilities and the inclusion of antimicrobials on products should the former approach fail. In prior work, a similar product (AM-3, Mastertaste Inc., Monterey, TN, USA) was used against the same four-strain mixture of L. monocytogenes with artificially contaminated commercial [33] and inhouse manufactured hotdogs [34] demonstrating significant reduction over inoculated controls. Flavoset 5400L was tested against four strains of L. monocytogenes in the same droëwors product as processed above. We observed a very quick reduction in L. monocytogenes achieving a 6.5-log reduction within two days and a >7-log reduction by four days of drying when 0.75% Flavoset 5400L was added to the droëwors marinade (Figure 6). Similarly to what was observed with E. coli O157:H7, the quick reduction observed with L. monocytogenes suggests that even a lower level of Flavoset 5400L (0.3–0.5%?) may be effective in achieving a 5-log reduction target. We increased use levels to 0.75% because we worked first with Salmonella and only achieved a 4.9-log reduction with 0.5% Flavoset. Perhaps it is worth re-examining 0.5% Flavoset with all three pathogens in future work.

Figure 6.

Droëwors process against four-strain mixture of Listeria monocytogenes strains without added Flavoset extract (diamond symbols) versus droëwors made with 0.75% (circles) Flavoset extract. Treatments were analyzed by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). The Limit of Detection (LOD) was established at 1 log CFU/mL by plating 1 mL of dilution instead of 0.1 mL when low levels were expected from prior sample data.

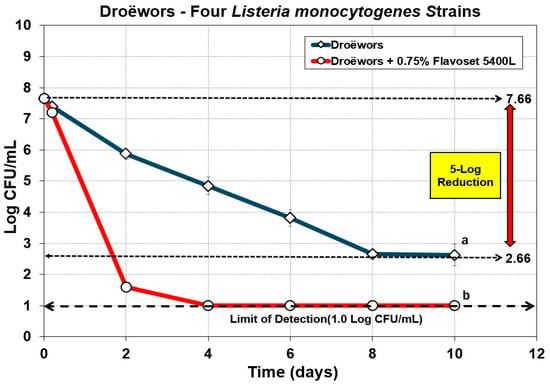

3.4. Biltong: Reduction in Salmonella Serovars Using Pyrolyzed Liquid Smoke Extracts as Flavoring and Antimicrobial

One concern was that prior work performed on the biltong process of air-dried beef was performed using acid-adapted cultures as per USDA-FSIS specifications in order to desensitize Salmonella to acid for a process that would receive acidic treatment [7,8]. Later we learned that acid-adapted Salmonella were more sensitive, rather than resistant, to biltong/droëwors processing conditions [15] and questions arose about whether we could still achieve a 5-log reduction in Salmonella using non-adapted cultures. When the biltong process was applied using non-adapted challenge cultures we obtained only a 4.6-log reduction. Trials including 0.75% Flavoset 5400L (pyrolyzed plant extract) in the marinade formulation allowed us to achieve a 5-log reduction in five days and a >6.41 log-reduction within eight days (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Biltong process against five serovar mixture of Salmonella (diamond symbols) versus biltong made with 0.75% (circles) Flavoset 5400L extract. Treatments were analyzed by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences; treatments with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). The Limit of Detection (LOD) was established at 1 log CFU/mL by plating 1 mL of dilution instead of 0.1 mL when low levels were expected from prior sample data.

3.5. Droëwors Processing Parameters

3.5.1. Droëwors Temperature and Relative Humidity Measurements

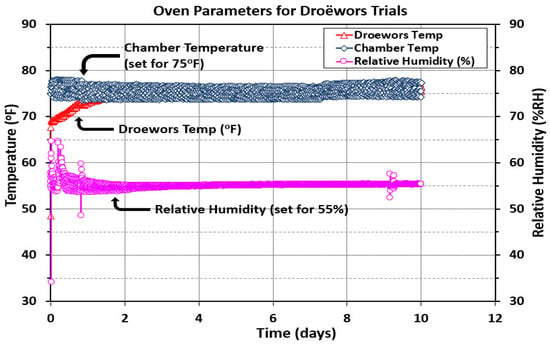

The humidity oven chamber was monitored with a handheld temperature data monitor that could accommodate four probes. Two probes were placed in the chamber, and an additional two probes were placed in either droëwors beef sticks or biltong beef pieces (Figure 3A). Additionally, a humidity probe extending to a handheld data monitor was set up in the chamber air space. The instrument was adjusted for temperature (75 °F/23.9 °C) and relative humidity (55% RH) based on our handheld probes, as the oven’s own probes were situated in the walls of the unit and often were off a little from the direct measurements made from within the chamber air space. Both handheld monitors were recorded to a laptop computer for subsequent graphing of the temperature or RH trace (Figure 8). The data for the two sets of paired temperature probes (air, beef) were averaged and shown as a single curve in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Oven temperature (°F) and relative humidity (%RH) measurements during droëwors processing. Chamber temperature (set for 75 °F/23.9 °C) is the average of two individual temperature probes in the chamber. Droëwors temperature (°F) is also the average of two probes, each placed in a different droëwors beef stick. Relative humidity (%RH) was also placed in the chamber. Measurements were taken at 15 min intervals over 10 days.

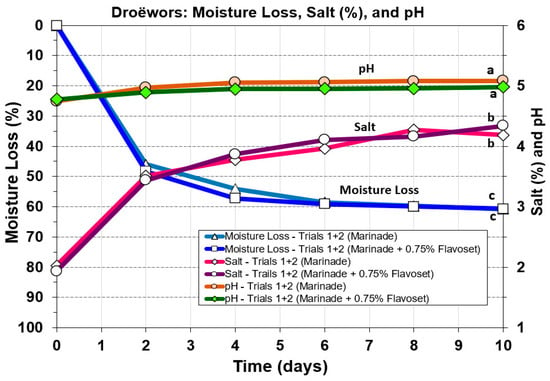

3.5.2. Comparison of Droëwors Moisture Loss, Salt, and pH Measurements

Moisture loss in droëwors was compared to both pH and % salt (Figure 9) and to water activity (Figure 10) as these are important aspects for the safety of these products. Moisture loss drops faster in droëwors reaching a ~50% loss in two days (Figure 9) as opposed to a 50% loss in five days in biltong; [8]). Since droëwors is a ground product in an oxygen permeable collagen casing, it would be expected to lose moisture at a faster rate. Salt concentration is 2% in the formulation and after a ~60% moisture loss this increases to 4.2–4.3% by the end of the 10-day drying cycle, similar to what would be observed in biltong at the same moisture loss. Droëwors pH dropped slightly from the original raw beef pH (5.6) down to pH 4.98–5.1 after being ground with vinegar and the rest of the marinade ingredients (day 0; Figure 8). Also, comparison of pH, salt, and moisture loss value trends in droëwors made with the standard formulation compared to droëwors with 0.75% Flavoset 5400L showed no significant difference (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Droëwors processing: effect on moisture loss, salt (%), and pH during drying in a humidity chamber (set for 75 °F/23.9 °C; 55% RH). Each graph curve is the mean of data obtained from duplicate trials (Trial 1 and 2). Similar treatments of droëwors (marinade) vs. droëwors (marinade + 0.75% Flavoset 5400L) were analyzed to each other by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences. Treatments with the same letters are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

Figure 10.

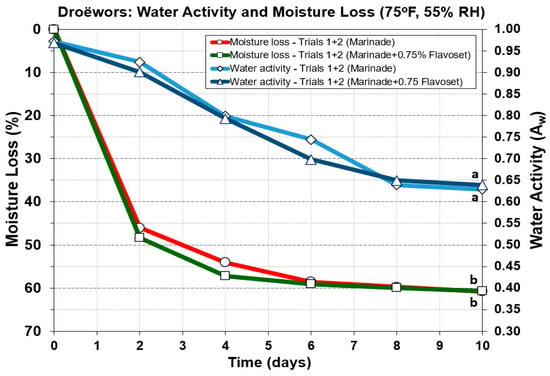

Droëwors processing: comparison of moisture loss and water activity (Aw) during drying in a humidity chamber (set for 75 °F/23.9 °C; 55% RH). Each graph curve is the mean of data obtained from duplicate trials (Trial 1 and 2). Similar treatments of droëwors (marinade) vs. droëwors (marinade + 0.75% Flavoset 5400L) were analyzed to each other by repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) using the Holm–Sidak test for pairwise multiple comparisons to determine significant differences. Treatments with the same letters are not significantly different (p > 0.05).

3.5.3. Comparison of Droëwors Moisture Loss and Water Activity (Aw) Measurements

Water activity, the ‘free, available’ water is the defining level of water that sets limits for growth of microorganisms [35]. Again, the difference between droëwors (ground beef ingredients) vs. biltong (solid beef) is that droëwors has salt (and other components) mixed into the meat homogenously throughout the product, while biltong has the marinade ingredients accumulated or absorbed at the surface. Therefore, the salt in droëwors can bind to free water and reduce its availability, helping to lower it much more quickly than during the drying of biltong. We observed that droëwors Aw reaches 0.80 in four days (Figure 10) while with biltong it barely reaches that level in eight days [8] at 75 °F (23.9 °C). Again, the means of duplicate trials of each condition (marinade vs. marinade + 0.75% Flavoset) for both moisture loss and Aw showed no significant difference from each other, demonstrating no impact by Flavoset on processing parameters for droëwors (Figure 10).

Given the biochemical changes that occur during droëwors processing, it is unsurprising that acid-adapted cultures behaved contrary to expectations when compared with non-adapted cultures. Growth in media containing 1% glucose lowers the pH to approximately 4.8, imposing stress on Salmonella. The droëwors process further compounds this stress through multiple simultaneous factors—acid from vinegar, increased salt concentration, and desiccation (moisture loss and reduced water activity). In combination, these conditions can overwhelm Salmonella, rendering them more sensitive to the process. This effect was evident when acid-adapted cultures were plated on XLD agar, which inhibits injured cells, resulting in lower recoveries compared to counts on TSA. Because acid-adapted cultures are already compromised by low pH, their survival is further challenged by the stresses inherent in droëwors and biltong production. Consequently, it may be prudent to conduct preliminary trials comparing acid-adapted and non-adapted cultures when designing challenge studies for new processes.

3.5.4. Liquid Smokes and Their Antimicrobial Activity in Food

The use of wood smoke to impart flavor to foods has a long history, extending back thousands of years. This practice persists today, employing diverse wood types such as oak, cherry, mesquite, apple, hickory, and pecan, each valued for their distinctive aromatic and flavor characteristics [36]. With the rise in commercial smoking, traditional slow-smoking methods have largely been supplanted by modern techniques that capture smoke volatiles in liquid form. These liquid smokes can be incorporated either prior to cooking (e.g., “smoked” meats) or post-cooking (e.g., “smoke flavor added”).

Although strongly aromatic, dark-colored liquid smokes remain commercially available, recent advances have led to the development of “refined” liquid smokes. These products undergo processes that reduce or remove ash, colorants, and phenolic compounds, yielding lighter flavor profiles with subtle roasted or nutty notes. Such refinement enhances their applicability across a broader range of food products [37,38]. Although there are still markets for the heavily aromatic and dark colored liquid smokes, a more recent development has been the appearance of ‘refined’ liquid smokes where much of the color components and heavy aromas have been removed and much of the ash, color compounds, and phenolics have been removed or reduced with subtle roast or nutty notes, making them adaptable to a greater array of food products [38,39,40]. An example is Flavoset 5400L, a refined liquid smoke extract produced by Kerry (St. Louis, MO, USA). Marketed as a natural flavoring, it imparts light toasted or roasted notes. Flavoset 5400L is comparable to AM-3, a product originally manufactured by Mastertaste prior to Kerry’s acquisition in 1998. AM-3 has been extensively investigated for its antimicrobial efficacy against Listeria monocytogenes in processed meats [33,40,41].

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the antimicrobial efficacy of refined pyrolyzed liquid smoke extract (Flavoset 5400L) when incorporated into droëwors and biltong formulations, demonstrating >7-log reductions in Salmonella, E. coli O157:H7, and Listeria monocytogenes with non-acid-adapted challenge cultures. Importantly, the purpose of this work was not to assess flavor attributes–those will be addressed in subsequent studies–but rather to determine the effectiveness of Flavoset as a flavorant with antimicrobial functionality. The findings confirm that inclusion of Flavoset at 0.75% provides a practical intervention strategy that meets USDA-FSIS validation requirements, thereby enhancing the microbial safety of non-thermally processed, air-dried beef products while maintaining their traditional processing characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.M.; methodology, P.M.M. and P.A.; software, P.M.M.; validation, P.A. and P.M.M.; formal analysis, P.M.M.; investigation, P.A.; resources, P.M.M.; data curation, P.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.M. and P.A.; writing—review and editing, P.M.M. and P.A.; visualization, P.M.M. and P.A.; supervision, P.M.M.; project administration, P.M.M.; funding acquisition, P.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Food Safety and Defense grant (2023-67017-40046) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the OSU Gilliland/Advance Food Professorship in Microbial Food Safety (21-57200), and the OSU Agricultural Experiment Station (OKL03284).

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the prior contributions of Caitlin Karolenko and Jade Wilkinson in prior work performed with demonstrating that acid-adapted Salmonella are more sensitive to biltong processing than non-adapted cultures that prompted us to look for additional additives to achieve the log reduction capable of validating these processes (droëwors and biltong) to satisfactory levels. We would also like to thank Joyjit Saha (Kerry Group, Beloit, WI, USA) for providing a sample of Flavoset 5400L for use in our studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, G.; Hu, S. A Comprehensive Review on the Recent Technological Advancements in the Processing, Safety, and Quality Control of Ready-to-Eat Meals. Processes 2025, 13, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediani, A.; Hamezah, H.S.; Jam, F.A.; Mahadi, N.F.; Chan, S.X.Y.; Rohani, E.R.; Che Lah, N.H.; Azlan, U.K.; Khairul Annuar, N.A.; Azman, N.A.F.; et al. A comprehensive review of drying meat products and the associated effects and changes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1057366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, A.B.; Chandola, V.; Bhat, S. Biltong Market Research Report 2033; Growth Market Reports: Maharashtra, India; Available online: https://growthmarketreports.com/report/biltong-market (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Verified Market Research Reports Team. Air-Dried Beef Market Size, Market Growth and Forecast; Verified Market Research Reports: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketreports.com/product/air-dried-beef-market/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- USDA-FSIS. FSIS Compliance Guideline for Meat and Poultry Jerky Produced by Small and Very Small Establishments; U.S. Food Safety and Inspection Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. pp 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- USDA-FSIS. FSIS Ready-to-Eat Fermented, Salt-Cured, and Dried Products Guideline; U.S. Food Safety and Inspection Service: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/documents/FSIS-GD-2023-0002.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Gavai, K.; Karolenko, C.; Muriana, P.M. Effect of biltong dried beef processing on the reduction of Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7, and Staphylococcus aureus, and the contribution of the major marinade components. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolenko, C.E.; Bhusal, A.; Nelson, J.L.; Muriana, P.M. Processing of Biltong (Dried Beef) to Achieve USDA-FSIS 5-log Reduction of Salmonella without a Heat Lethality Step. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Prieto, M.; Bernardo, A.; Hill, C.; López, M. The acid tolerance response of Salmonella spp.: An adaptive strategy to survive in stressful environments prevailing in foods and the host. Food Res. Intl. 2012, 45, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriil, A.; Giannenas, I.; Skandamis, P.N. A current insight into Salmonella’s inducible acid resistance. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 3835–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyer, G.J.; Johnson, E.A. Acid adaptation induces cross-protection against environmental stresses in Salmonella typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyer, G.J.; Johnson, E.A. Acid adaptation promotes survival of Salmonella spp. in cheese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 2075–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; He, S.; Zhou, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, M.; Shi, X. Response to acid adaptation in Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods. Parameters for Determining Inoculated Pack/Challenge Study Protocols. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 140–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, P.; Karolenko, C.E.; Wilkinson, J.; Muriana, P.M. Acid Adaptation Leads to Sensitization of Salmonella Challenge Cultures During Processing of Air-Dried Beef (Biltong, Droëwors). Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidt, F.J.; Andress, E.L.; Ingham, B. Recommendations for Designing and Conducting Cold-fill Hold Challenge Studies for Acidified Food Products. Food Prot. Trends 2018, 38, 322–328. [Google Scholar]

- USDA-FSIS. Availability of FSIS Ready-to-Eat Fermented, Salt-Cured, and Dried Products Guideline. Fed. Regist. 2023, 88, 29188–29189. [Google Scholar]

- USDA-FSIS. Safe and Suitable Ingredients Used in the Production of Meat, Poultry, and Egg Products; FSIS Directive 7120.1, rev. 44; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Juneja, V.K.; Hwang, C.A.; Friedman, M. Thermal inactivation and postthermal treatment growth during storage of multiple Salmonella serotypes in ground beef as affected by sodium lactate and oregano oil. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, M1–M6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, C.E.; Smith, J.V.; Broadbent, J.R. Efficacy of washing meat surfaces with 2% levulinic, acetic, or lactic acid for pathogen decontamination and residual growth inhibition. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Eblen, B.S.; Marks, H.M. Modeling non-linear survival curves to calculate thermal inactivation of Salmonella in poultry of different fat levels. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 70, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Yadav, A.S.; Hwang, C.A.; Sheen, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Friedman, M. Kinetics of thermal destruction of Salmonella in ground chicken containing trans-cinnamaldehyde and carvacrol. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolenko, C.E.; Bhusal, A.; Gautam, D.; Muriana, P.M. Selenite cystine agar for enumeration of inoculated Salmonella serovars recovered from stressful conditions during antimicrobial validation studies. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, E.D.; Cutter, C.N. Effects of acid adaptation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on efficacy of acetic acid spray washes to decontaminate beef carcass tissue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA-AMS. Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications; Fresh beef series 100; Agricultural Marketing Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Karolenko, C.; Muriana, P.M. Quantification of process lethality (5-log reduction) of Salmonella and salt concentration during sodium replacement in biltong marinade. Foods 2020, 9, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.M. Best practice in statistics: The use of log transformation. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2022, 59, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, A.; Martos, P. Log Transformation and the Effect on Estimation, Implication, and Interpretation of Mean and Measurement Uncertainty in Microbial Enumeration. J. AOAC Int. 2018, 102, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, B.; Cornu, M.; Lahellec, C.; Feinberg, M.H. Experimental Evaluation of Different Precision Criteria Applicable to Microbiological Counting Methods. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 88, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B.A.; Overbaugh, J. Basic Statistical Considerations in Virological Experiments. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, A.; Zhu, M.-J. Mapping the landscape of listeriosis outbreaks (1998–2023): Trends, challenges, and regulatory responses in the United States. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 154, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.K.; Mishra, S.; Tuglo, L.S.; Sarangi, A.K.; Kandi, V.; AL Ibrahim, A.A.; Alsaif, H.A.; Rabaan, A.A.; Zahan, M.K.-E. Recurring food source-based Listeria outbreaks in the United States: An unsolved puzzle of concern? Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedela, S.; Escoubas, J.R.; Muriana, P.M. Effect of inhibitory liquid smoke fractions on Listeria monocytogenes during long-term storage of frankfurters. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedela, S.; Gamble, R.K.; Macwana, S.; Escoubas, J.R.; Muriana, P.M. Effect of inhibitory extracts derived from liquid smoke combined with postprocess pasteurization for control of Listeria monocytogenes on ready-to-eat meats. J. Food Prot. 2007, 70, 2749–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, W.H. Influence of Water Activity on Foodborne Bacteria—A Review1. J. Food Prot. 1983, 46, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, T.R. Salt, Smoke, and History. Gastronomica 2001, 1, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.; de la Calle, B.; Palme, S.; Meier, D.; Anklam, E. Composition and analysis of liquid smoke flavouring primary products. J. Sep. Sci. 2005, 28, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, N.; Oliveira, A.C.M.; Himelbloom, B.H.; Leigh, M.B.; Crapo, C.A. Chemical characterization of commercial liquid smoke products. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 1, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingbeck, J.M.; Cordero, P.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Johnson, M.G.; Ricke, S.C.; Crandall, P.G. Functionality of liquid smoke as an all-natural antimicrobial in food preservation. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.M.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Lary, R.Y.; Griffis, C.L.; Vaughn, K.L.S.; Marcy, J.A.; Ricke, S.C.; Crandall, P.G. Spray application of liquid smoke to reduce or eliminate Listeria monocytogenes surface inoculated on frankfurters. Meat Sci. 2010, 85, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, N.; Himelbloom, B.H.; Oliveira, A.C.M.; Leigh, M.B.; Crapo, C.A. Refined Liquid Smoke: A Potential Antilisterial Additive to Cold-Smoked Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).