1. Introduction

Scientists heavily rely on the reliability of genomic resources as they often reuse sequence data generated by others. However, if the quality of the available data is low, it not only affects downstream analysis but also propagates further into the public resources. Consequently, ensuring the quality of public data in molecular biology becomes crucial and presents a challenge for developing automated error detection and processing approaches [

1].

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) has revolutionized the surveillance of human pathogenic bacteria, and numerous databases host WGS data. As of October 2025, the genomes of 101 species are stored in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Pathogen Detection Database (NCBI-PD), ensuring convenient accessibility to these genomes [

2]. However, strict scrutiny procedures to identify and filter out low-quality or contaminated raw sequences, misassembled genomes, and incorrectly assigned taxonomies are lacking during data submission. This poses challenges in correctly assembling raw reads, assigning accurate species taxonomies, and characterizing genes. Particularly, raw data submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) undergoes limited scrutiny at present [

3].

Genome assemblies often encounter quality issues such as sequencing errors, misassembly, and contamination. Contamination-related errors are particularly concerning as they can lead to misinterpretation of data, mischaracterization of gene content, inaccurate species assignment, and biases in genomic analyses. Contamination is suspected to be widespread, originating from foreign DNA present in raw biological materials or introduced during library preparation. Sequencing errors and misassembly can result in fragmented genomes, which hinder downstream analysis, including the detection of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and phages [

4].

Three widely used quality control (QC) parameters for genome assessment are completeness, contiguity, and accuracy. Completeness is determined by the gene content of contigs. As contiguous genome that contains few gene contents is not useful for downstream analysis [

5]. High-quality genomes exhibit completeness above 90% [

6]. Contiguity relates to the size and number of contigs, with high-quality genomes characterized by fewer contigs of larger size [

7]. Accuracy is typically evaluated by comparing the assembled genome with a reference or by mapping reads to the assembled genome to assess coverage. Accurate genomes show consistent contig order (for reference-based assembly) or a lower percentage of unmapped reads (for de novo assembly [

8].

Individual measures of contiguity, completeness, or accuracy alone can be misleading when judging genome quality [

7]. Although numerous quality control measurements are available, there is currently no consistent framework for integrating these metrics to accurately report the quality of a whole genome [

9]. Hence, an integration of quality control parameters is necessary for precise genome quality assessment.

Given the importance of reliable genomic resources and the potential drawbacks of low-quality genomes in public databases, it is crucial to address the gaps in quality assessment and control. Present study aimed at introducing a composite Genome Quality Index (GQI) that integrates four widely reported and biologically interpretable metrics: BUSCO single-copy completeness, contig count, N50, and unmapped read percentage. We apply this framework to a controlled case study of 474 pathogenic bacterial genomes originating from South Korea, selected because they share consistent Illumina sequencing strategies, complete raw read availability, and harmonized metadata within public repositories. Focusing on a single country minimizes confounding variation arising from heterogeneous submission protocols and sequencing platforms while still providing taxonomically diverse genomes. This geographic focus reflects a controlled case study rather than a country-specific bias; the GQI framework itself is globally applicable.

We further extend the analysis in three ways. First, we re-assemble all genomes from raw reads under a standardized pipeline to minimize methodological variation and then compute the GQI from normalized, log-transformed metrics. Second, we perform species-level analyses and unsupervised clustering to identify genome-quality typologies and taxon-specific biases. Third, we compare GQI distributions between our curated dataset and an independent

Enterobacteriaceae cohort (

n = 5781) and evaluate the ability of a Random Forest classifier to automatically assign genome-quality tiers. From the top-decile GQI genomes, we derive empirical thresholds that refine existing recommendations such as Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG)/metagenome assembled genome (MIMAG) [

10].

Together, these analyses yield a reproducible and scalable composite quality framework that complements established tools such as BUSCO, QUAST, ALE, gVolante, CheckM, and Hybracter, [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] and can be embedded into submission workflows and surveillance dashboards to systematically flag low-quality genomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Retrieval and Study Design

We compiled a primary dataset of 474 pathogenic bacterial genomes from the NCBI pathogen detection (NCBI-PD) database. Inclusion criteria were: (i) isolates originating from South Korea; (ii) Illumina short-read WGS with publicly available raw reads in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA); (iii) clear species-level taxonomic labels; and (iv) complete metadata enabling standardized processing. Focusing on a single country ensured homogeneous sequencing technologies and submission practices, while still capturing multiple clinically relevant species (

Supplementary File S1). Raw reads were retrieved from the SRA accessed on 12 December 2024 using the SRA Toolkit (

https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools). Briefly, prefetch was used to fetch the SRA accession numbers, and the validity of the raw sequencing data was determined using vdb-validate. Forward and reverse reads were retrieved using fastq-dump with the --split-file parameter. As part of validation, we also compiled an independent

Enterobacteriaceae set (

n = 5781) comprising public genomes from

Escherichia coli,

Salmonella enterica,

Klebsiella pneumoniae, and related taxa with ≥20 assemblies per species and available raw reads or high-quality assemblies (

Supplementary File S2). These genomes were processed using the same pipeline wherever raw data were available.

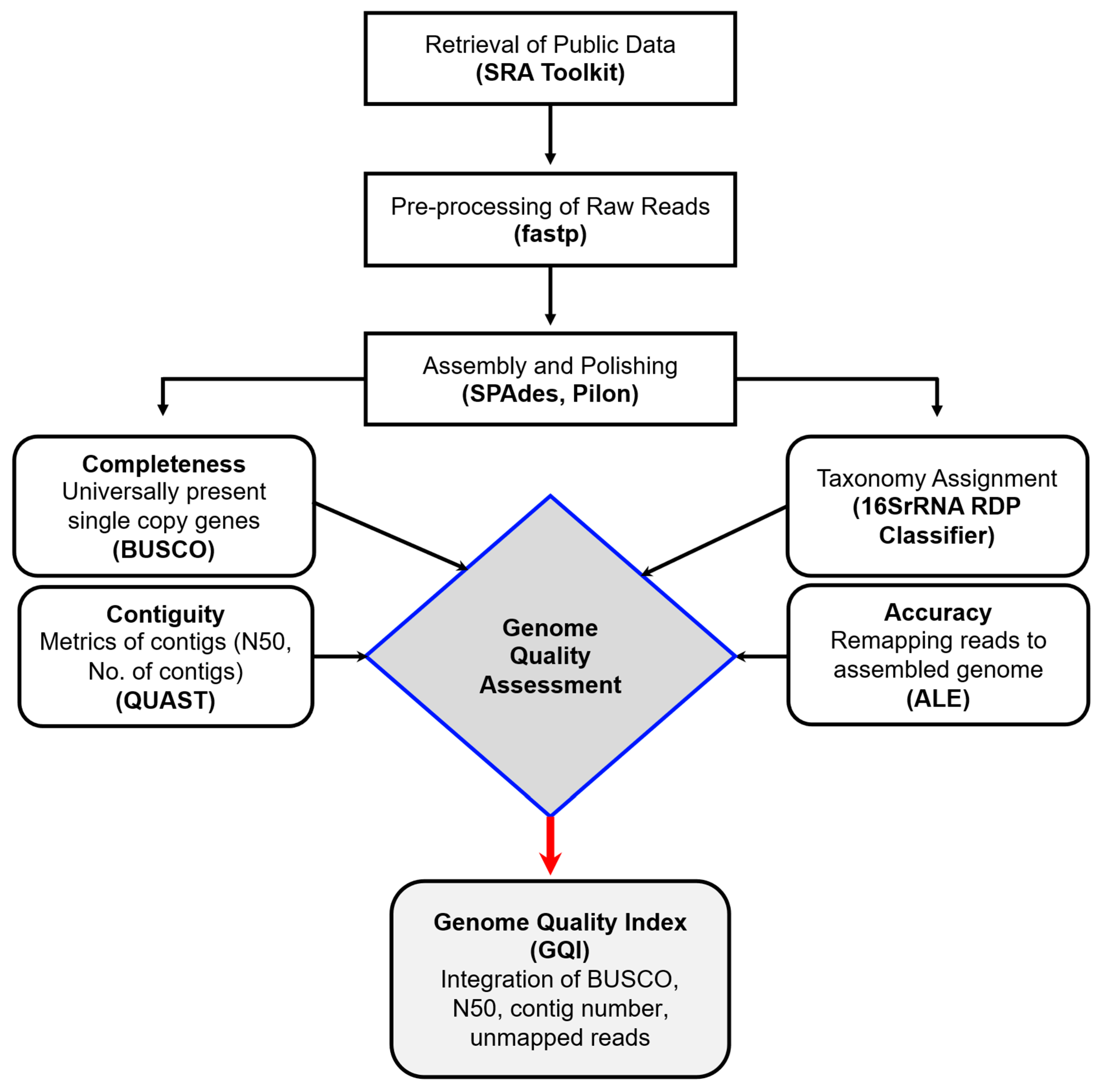

2.2. Quality Assessment of Whole Genomes

Quality trimming of the raw reads was performed using fastp v1.0.1 [

18]. Genomes were assembled using SPAdes v4.2.0 assembler [

19] with default settings, and subsequent polishing of the assembled genomes was carried out using Pilon v1.24 [

20]. The taxonomy of the genomes was determined through 16S RDP classifier v1.23 [

21]. To assess genome quality, we employed the benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCO v5) tool [

11] with the --auto-lineage-prok detection parameter. BUSCO measures several metrics, including complete single-copy, duplicated, fragmented, and missing orthologs in the genomes. The contiguity of the assembled genomes was evaluated using QUAST v5.3.0, a quality assessment tool [

12], with default parameters. Contiguity features including number of contigs and N50 values (defined as the length of the contig at which half of the genome is represented by contigs of that size or larger [

7]) were determined. Accuracy, which examines the positions of sequence read pairs within an assembly to identify anomalies [

8], was evaluated using the Assembly Likelihood Evaluation (ALE) framework [

13]. ALE measures the ratio of mapped and unmapped reads to the assembled genome. The complete workflow for genome quality assessment is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Species names were harmonized to consistent labels (e.g., “

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica” collapsed to

S. enterica). To ensure meaningful species-level statistics, only taxa with ≥5 genomes were included in groupwise analyses and this yielded 11 distinct taxa (

Supplementary File S1). Because contig count, N50, and unmapped read percentage exhibited skewed distributions and apparent non-linear relationships in preliminary plots, we applied log

10 transformations to these metrics prior to correlation and regression analyses. We use the following qualitative categories for correlation strength: “very strong” (|r| ≥ 0.90), “strong” (0.70–0.89), “moderate” (0.40–0.69), “weak” (0.20–0.39), and “negligible” (|r| < 0.20). These thresholds are reported alongside exact r values to avoid ambiguous wording.

2.3. Genome Quality Index (GQI) Construction and Clustering

To construct the GQI, we first min–max normalized each metric to the [0, 1] range so that higher values consistently reflected better quality. Specifically, BUSCO complete single-copy percentages and log10-transformed N50 values were normalized directly, whereas log10(contig count) and log10(unmapped read percentage) were inverted prior to normalization so that genomes with fewer contigs and fewer unmapped reads received higher scores. For descriptive purposes, genomes were stratified into three quality tiers based on GQI tertiles: “low” (GQI ≤ 0.50), “medium” (0.50 < GQI ≤ 0.75), and “high” (GQI > 0.75). In addition, we applied k-means clustering to the same normalized metrics, with the optimal number of clusters chosen via silhouette scores, to explore genome-quality typologies.

2.4. Species-Level and Comparative Analyses

Species-level differences in GQI were tested using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests. To compare our curated All_QC set (obtained from 474 genomes) to the Enterobacteriaceae validation cohort (n = 5781), we used Welch’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test depending on normality, along with Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to compare entire distributions.

2.5. Machine-Learning Classification

We trained a Random Forest classifier (scikit-learn) using the four raw metrics (BUSCO complete, contig count, N50, unmapped read percentage) to predict the three GQI-defined quality tiers. The dataset was split into 80% training and 20% test sets, stratified by class. Hyperparameters were tuned via five-fold cross-validation on the training set. Performance was evaluated using accuracy, macro-averaged F1-score, and confusion matrices on the held-out test set.

2.6. Threshold Derivation

To propose empirical quality thresholds, we examined genomes in the top decile of GQI (>0.85) and computed the 10th percentile for BUSCO completeness and N50, and the 90th percentile for contig count and unmapped reads. These percentiles were used to derive threshold values that characterize consistently high-quality genomes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Taxonomy Assignment

We used the 16S RDP classifier to assign taxonomy to 474 whole genomes. Our analysis revealed that 14 of these genomes showed 16S rRNA gene contamination of other bacteria, primarily from

Bradyrhizobium sp. Such contamination can result in incorrect taxonomy assignment and strain identification. The existence of contaminated genomes within public resources undermines the reliability of downstream analysis [

22]. Notably, all of the contaminated genomes were found to be of low quality in terms of completeness, contiguity, and accuracy. This observation aligns with a previous study that reported similar contamination issues in genomes sequenced using Illumina-based short-read sequencers and among publicly available genomes in NCBI [

23,

24]. Therefore, implementing proper screening procedures during genome submission to public databases is crucial to improve the overall quality of these databases.

3.2. Distributions of Completeness, Contiguity, and Accuracy Metrics

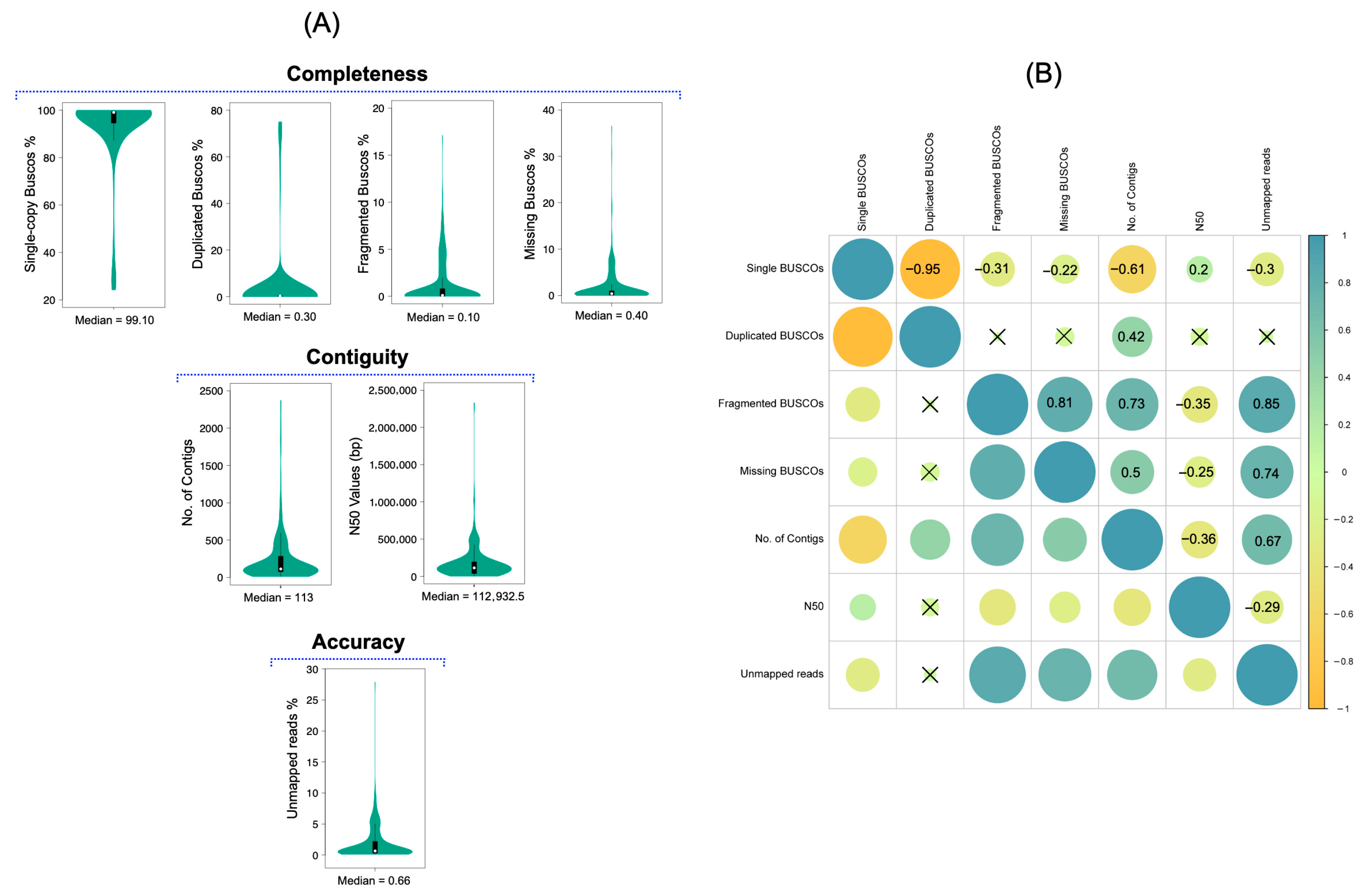

We first summarized the distributions of completeness, contiguity, and accuracy metrics for the 474 assemblies (

Figure 2A). The median value of complete single-copy BUSCO was 99.10% with an interquartile range (IQR) of 4.5%. Median percentages of duplicated, fragmented, and missing BUSCO were 0.30%, 0.10% and 0.40%, with IQRs of 0.20%, 0.80% and 0.90%, respectively.

For contiguity, the median number of contigs was 113 (IQR 209) and the median N50 was 112,932 bp (IQR 156,297 bp). For accuracy, the median percentage of unmapped reads was 0.65% (IQR 1.88%). The relatively wide IQRs, particularly for contig count, N50, and unmapped reads, reflect the presence of both high-quality and poor-quality genomes in the dataset.

These values are broadly consistent with previous reports that consider genomes with complete single-copy BUSCO above 90% and low levels of missing, duplicated, and fragmented BUSCO as high-quality [

25]. In our dataset, 392 genomes (83%) had complete single-copy BUSCO > 90%; 444 (94%), 370 (78%), and 372 (78%) had less than 2% duplicated, fragmented, and missing BUSCO, respectively (

Supplementary File S3). Regarding contiguity, 354 genomes (75%) had N50 values greater than 50 kb, and 346 (73%) had fewer than 200 contigs. For accuracy, 348 genomes (73%) had less than 2% unmapped reads. While more than 70% of genomes showed favorable values for individual metrics, they did not always perform consistently across all metrics. This motivated a more detailed examination of relationships among completeness, contiguity, and accuracy.

3.3. Relationships Among Quality Metrics and Non-Linear Trends

The correlation among the completeness, contiguity, and accuracy parameters was assessed using Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficient. Significantly very strong, strong, moderate, and less strong correlations between the features are shown in

Figure 2B (

p value < 0.05). The percentage of complete single-copy BUSCO manifested a strong negative correlation (ρ = −0.61) with the number of contigs. Additionally, it exhibited a less strong negative correlation with unmapped reads (ρ = −0.3), and a less strong positive correlation with N50 values (ρ = 0.2). However, it is challenging to establish a consistent relationship between complete single-copy BUSCO, N50 values, and the number of contigs due to the presence of genomes with diverse quality metrics. Some genomes with low N50 values and a higher number of contigs still had a wide range of complete single-copy BUSCO percentages and vice versa.

This pattern likely reflects that BUSCO targets conserved single-copy orthologs, which can remain intact even when the assembly is highly fragmented. Repetitive or high copy elements such as rRNA operons, tRNA clusters, or mobile elements can break assemblies locally without greatly affecting these core genes, and short high confidence contigs in high coverage datasets may still contain complete BUSCOs. Consequently, BUSCO completeness alone can overestimate the quality and usability of fragmented genomes, reinforcing the need to integrate multiple metrics as in our GQI framework.

We observed strong positive associations (0.73) between fragmented BUSCO and the number of contigs. Additionally, fragmented BUSCO showed very strong associations (0.8) with N50 values and unmapped reads. The percentage of missing BUSCO had a less strong negative correlation (−0.25) with N50 values, a moderate positive correlation (0.5) with the number of contigs, and a strong positive correlation (0.74) with unmapped reads. On the other hand, duplicated BUSCO values did not show a significant correlation with N50 values or unmapped reads; however, they exhibited a moderate positive correlation (0.42) with the number of contigs. Although these trends were not consistent across all genomes, they provide insights into potential associations among the parameters. The negative relationship between single-copy BUSCO and the number of contigs, along with the positive relationships of the other three completeness parameters, suggests that genomes with lower numbers of contigs are better assembled and exhibit higher completeness. As a result, N50 values tend to increase, and the percentage of unmapped reads decreases, as indicated by their associations. Higher percentages of fragmented and duplicated BUSCO indicate contamination in the genome sequences, often associated with an elevated number of contigs and lower N50 values. Conversely, lower percentages of these completeness parameters suggest better contiguity and accuracy of the genomes [

14].

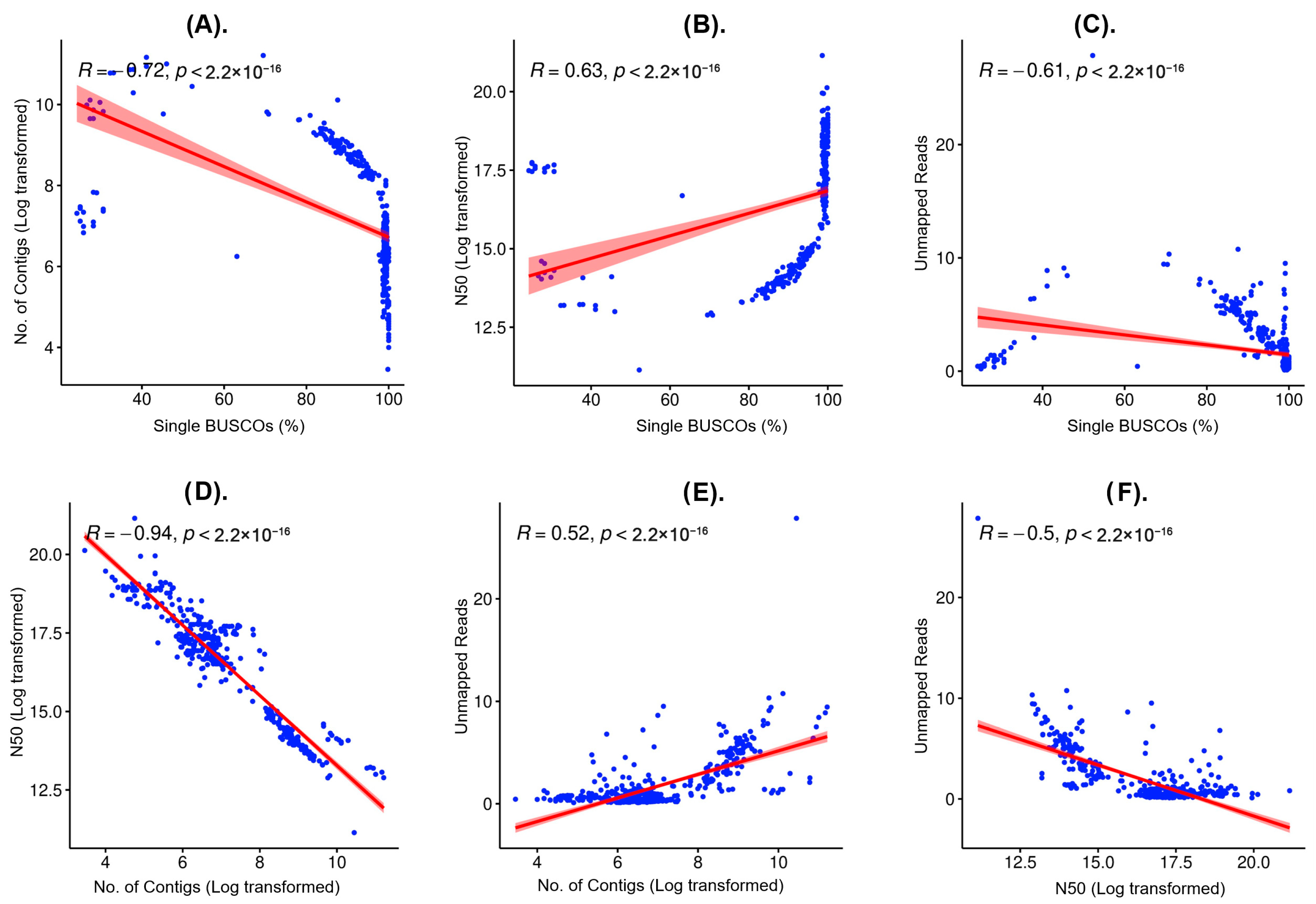

To explore potential non-linear relationships and examined six pairwise combinations of four key metrics, including complete single-copy BUSCO, log

10(number of contigs), log

10(N50) and log

10(unmapped reads), we used linear regression (

Figure 3). As expected, the strongest linear trend was the inverse relationship between contig number and N50. Relationships involving unmapped reads and BUSCO scored displayed curvature (e.g., an inverted-U pattern between BUSCO and unmapped reads), indicating that linear fits on raw scales can understate or misrepresent true associations. This justifies the use of log-transforms and multivariate approaches rather than relying solely on simple linear correlations or single-metric thresholds.

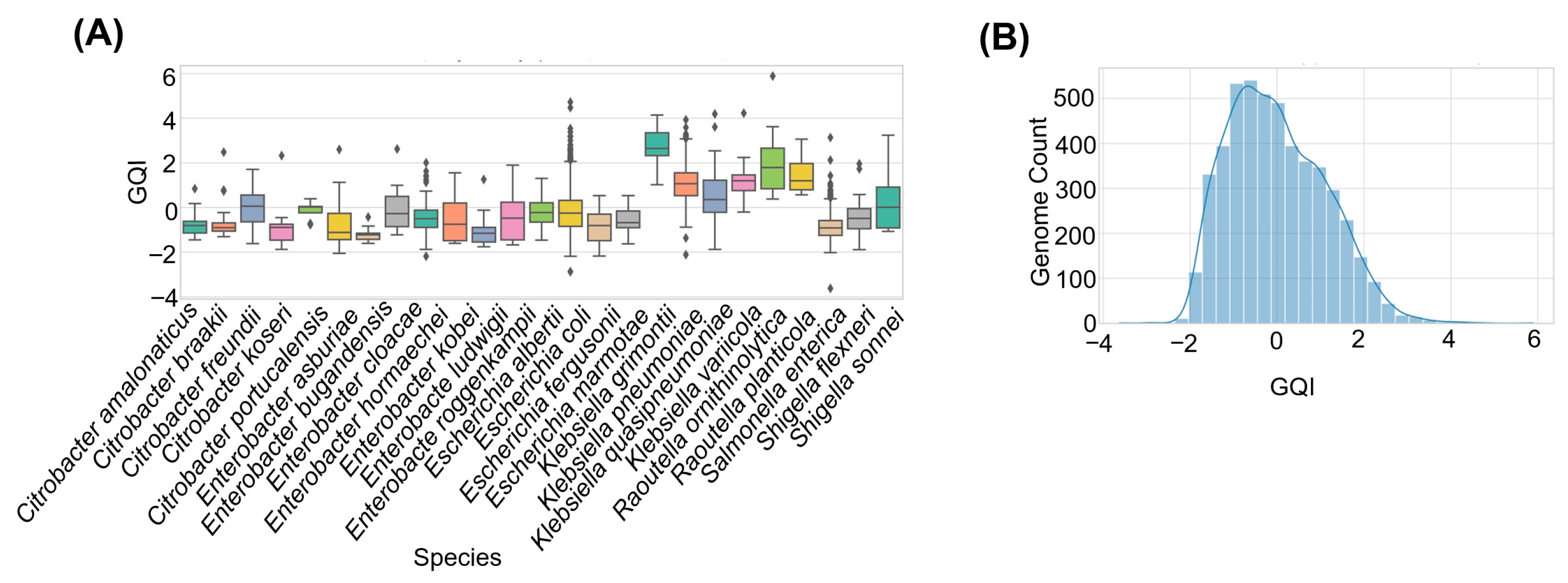

3.4. Genome Quality Index (GQI) Construction

GQI values across the 474 genomes ranged from 0.23 to 0.96, with a central cluster between 0.70 and 0.85 (

Figure 4A). Using tertiles of GQI, we classified 100 genomes (21%) as low-quality (GQI ≤ 0.50), 179 (38%) as medium-quality (0.50–0.75), and 195 (41%) as high-quality (GQI > 0.75). High GQI genomes showed the expected profile of high completeness, low fragmentation, and strong read support, whereas low GQI genomes typically combined reduced completeness, many contigs, small N50 values, and elevated unmapped reads. Notably, several genomes that would be considered acceptable based on a single metric, such as BUSCO completeness above 90%, fell into the medium or low GQI tiers. This illustrates the added resolution obtained by integrating multiple indicators into a single composite score.

3.5. Species-Level Differences in Genome Quality

GQI allowed us to explore species-specific patterns (

Figure 4B). Stacked bar plots of quality tiers revealed that

Cronobacter sakazakii and Listeria monocytogenes genomes were predominantly high-quality, with very few low-GQI assemblies (

Figure 4A). In contrast, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis displayed a broader spread of GQI values, including a substantial fraction of medium- and low-quality genomes.

Boxplots and ranked mean GQI values by species (

Figure 4B,C) confirmed these patterns. One-way ANOVA showed that mean GQI differed significantly among species (F = 39.37,

p < 1.05 × 10

−33), and Tukey’s HSD tests identified pronounced contrasts between consistently high-quality taxa (e.g.,

C. sakazakii,

L. monocytogenes) and more variable taxa (e.g.,

K. pneumoniae,

M. tuberculosis). These differences likely reflect a combination of biological factors (e.g., genome size, GC content, repeat structure) and technical aspects such as sequencing depth and assembly strategy [

7,

25,

26].

From a surveillance standpoint, the presence of intermediate- and low-GQI genomes among common pathogens such as K. pneumoniae and Salmonella enterica suggests that public collections include assemblies that may not be suitable for high-resolution comparative analyses without further curation.

3.6. Comparison with Public Enterobacteriaceae Genomes

To test the generality of the framework, we applied the same pipeline and GQI calculation to an independent

Enterobacteriaceae dataset. The resulting GQI distributions broadly overlapped with those of the curated All_QC set but were shifted slightly toward lower values and showed greater dispersion (

Figure 5A). Enterobacteriaceae assemblies also contained a larger fraction of low and medium GQI genomes (

Figure 5B).

These findings are consistent with previous work documenting variable quality, contamination and incomplete metadata in public genomes from Enterobacteriaceae and other pathogens [

3,

4,

22]. The comparison illustrates how GQI can be used as a screening tool: genomes with very low GQI values can be flagged for reassembly, reannotation, or exclusion from sensitive analyses such as AMR surveillance and outbreak investigation [

27,

28,

29].

3.7. Machine-Learning Prediction of Quality Tiers

We next evaluated whether quality tiers could be predicted automatically from the four raw metrics. The Random Forest classifier achieved 97% accuracy on the held-out test set, with macro-averaged F1-scores above 0.95 for all three classes. Feature importance analysis indicated that contig count and N50 contributed most strongly to discrimination, followed by BUSCO completeness and unmapped read percentage.

This high performance shows that a small set of interpretable metrics is sufficient for automated quality tier assignment once a composite score such as GQI is defined. Such classifiers could be embedded into submission portals or institutional pipelines to provide instant feedback to depositors, like quality dashboards used in other genomics contexts [

6,

9,

10,

15,

27,

30].

3.8. Empirical Thresholds for High-Quality Genomes

We next derived empirical thresholds for high-quality genomes by examining the top decile of assemblies (GQI > 0.85). These genomes shared a characteristic profile: complete single-copy BUSCO ≥ 98.6%, ≤30 contigs, N50 ≥ 1 Mb and unmapped reads ≤0.82%. These values are broadly consistent with, but somewhat more stringent than, criteria proposed in MISAG/MIMAG and other frameworks for high-quality bacterial and metagenome-assembled genomes [

10,

26].

When applied back to the full dataset, these thresholds captured most high-GQI genomes while excluding most low-GQI assemblies, confirming their internal consistency with the composite index. We therefore propose them as practical guidance for curators and submitters, with the caveat that taxon-specific adjustments may be necessary for particularly challenging genomes.

3.9. Biological Implications of Low-Quality Genomes

Low-quality assemblies have direct consequences for biological interpretation and public health. Fragmentation can obscure mobile genetic elements, genomic islands, and structural variants, while misassemblies may introduce false positives or negatives in gene presence–absence matrices, distort phylogenies, and misclassify transmission clusters, especially when strains differ by only a small number of SNPs [

2,

3,

26,

27,

29].

Our results show that a non-trivial fraction of genomes in contemporary surveillance efforts and public repositories fall below conservative GQI-based thresholds. This echoes prior calls for stricter submission guidelines, systematic quality checks, and integration of assembly metrics into surveillance pipelines [

15,

29,

31]. GQI offers a quantitative and interpretable scaffold for such initiatives, enabling consistent triage of genomes for reassembly, reannotation, or exclusion from high-stakes analyses.

3.10. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, we did not have explicit per-sample coverage information for all genomes. While low unmapped read fractions and high BUSCO completeness suggest adequate coverage for most assemblies, certain edge cases, particularly those with high unmapped reads, could reflect low or uneven coverage. Future work integrating coverage profiles and depth-based metrics would refine GQI further [

30,

32].

Second, we chose BUSCO rather than CheckM as the primary completeness metric because BUSCO provides gene-level resolution across a broad bacterial lineage set and is widely integrated into assembly workflows [

11,

14]. Nonetheless, CheckM’s explicit contamination estimates and lineage-specific models offer clear advantages for metagenome-assembled genomes and complex communities [

16]. We therefore view GQI as complementary to CheckM and anticipate that future implementations could integrate both metrics.

Third, our analysis was based on re-assembled genomes rather than the originally submitted assemblies. This design was intentional: by standardizing the assembly pipeline, we sought to isolate intrinsic genome properties and raw data quality from submission pipeline variability. However, it means that our study evaluates the quality achievable under a uniform pipeline, not the exact quality of deposited assemblies. For repository auditing, a future study could compute GQI directly on in situ assemblies, perhaps stratifying by assembler or sequencing technology [

1,

3,

6,

25,

26,

27].

Finally, while our case study focuses on South Korean isolates to leverage homogeneous metadata and raw reads, the framework is not geographically constrained. Applying GQI across multiple countries, sequencing centers and genome types (including metagenome-assembled genomes) will be an important next step.

4. Conclusions

We developed a composite Genome Quality Index (GQI) that integrates BUSCO completeness, N50, contig count and unmapped read percentage into a single, interpretable score for bacterial genomes. Applied to 474 re-assembled pathogenic genomes and an independent Enterobacteriaceae dataset, GQI captures established relationships among completeness, contiguity and accuracy metrics while revealing non-linear behavior that is not apparent from single metrics alone, identifying species-specific quality patterns, highlighting that expectations for genome quality should be taxon-aware, and distinguishing high-, medium- and low-quality assemblies more effectively than individual metrics, thereby supporting robust quality-tier classification. It further enables empirical derivation of practical thresholds for high-quality genomes (BUSCO ≥ 98.6%, ≤30 contigs, N50 ≥ 1 Mb, unmapped reads ≤0.82%) and can be approximated with high accuracy by a Random Forest classifier using only four routinely reported metrics. By complementing tools such as BUSCO, QUAST, ALE, gVolante, CheckM, and Hybracter, [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] the GQI framework provides an actionable, reproducible, and scalable approach to elevating genome-quality standards in microbial genomics, and its integration into submission portals, repository dashboards, and pathogen surveillance pipelines will help ensure that downstream analyses, from AMR surveillance to comparative evolutionary studies, which are based on genomes whose quality has been assessed in a transparent and quantitatively rigorous manner.