Abstract

Electromobility provides an effective solution for developing countries to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, enhance energy security, and increase environmental sustainability. The current study evaluates the feasibility of implementing electric vehicles (EVs) powered by renewable energy in developing countries. Based on qualitative methods, including expert interviews, it discusses existing transportation systems, the benefits of EVs, and significant constraints such as poor infrastructure, high initial investment, and ineffective policy structures. Evidence further suggests that EV adoption is likely to bring considerable benefits, particularly in cities with high population densities, adequate infrastructure, and supportive regulations that facilitate rapid adoption. Countries like India and Kenya have reduced their fuel import bills and created new jobs. At the same time, cities such as Bogota and Nairobi have seen improved air quality through the adoption of electric public transit. However, the transition requires investments in charging infrastructures and improvements in power grids. Central to this is government backing, whether through subsidy or partnership. Programs like India’s Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles (FAME) initiative and China’s subsidy program are prime examples of such support. The study draws on expert interviews to provide context-specific insights that are often absent in global EV discussions, while acknowledging the limitations of a small, regionally concentrated sample. These qualitative findings complement international data and offer grounded implications for electromobility planning in developing contexts. It concludes that while challenges remain, tailored interventions and multi-party public–private partnerships can make the economic and environmental promise of electromobility in emerging markets a reality.

1. Introduction

In today’s world, environmental degradation, climate change, and public health crises are intensifying, and as a result, sustainable mobility has become a global priority. Electromobility is one of the most widely discussed and promising solutions, referring to the use of electric-powered vehicles (EVs) that operate with integrated infrastructure and increasingly rely on renewable energy sources. Electromobility is not just a technical solution; it represents a systemic shift aimed at reducing reliance on fossil fuels, improving urban air quality, stimulating green economies, and enhancing energy security [1].

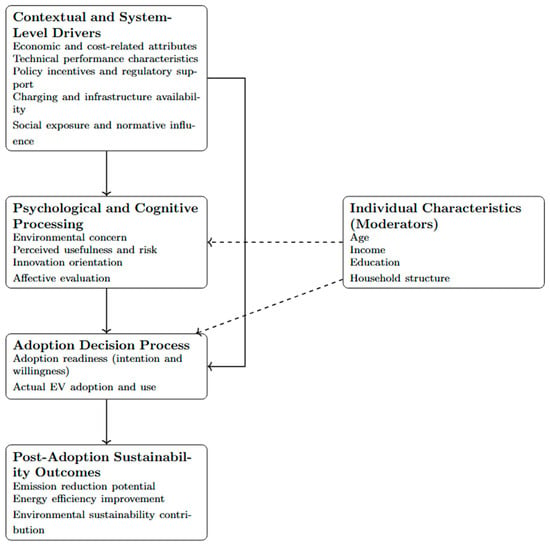

While most of the discourse and implementation of electromobility have centered on developed regions such as the United States, the European Union, and Japan, the conversation must now include developing countries, as these countries face unique socio-economic and infrastructural challenges. As highlighted by [2], emerging and developing economies already played a significant role in the global vehicle market in the 1990s, and this influence has continued to grow. Today, these countries are experiencing rapid urbanization, a growing middle class, and worsening air pollution, which creates an urgent need for sustainable transportation solutions. However, many of these regions still lack reliable electricity grids, public charging infrastructure, supportive regulations, and sufficient consumer awareness, which makes it difficult for them to adopt electromobility fully [3,4,5]. The context of EV adoption in developing countries, including the interplay between economic, infrastructural, and environmental factors, is summarized in Figure 1. This framework is later refined and operationalized through expert interviews and thematic analysis to reflect context-specific challenges in developing countries.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating the contextual drivers, psychological mechanisms, decision processes, and sustainability outcomes associated with electric vehicle adoption.

This study begins by defining electromobility not simply as the adoption of electric cars but as a broader socio-technical transformation. This transformation encompasses electric buses, two-wheelers, trolleybuses, and trains, as well as the entire infrastructure ecosystem surrounding them, including charging networks, energy storage, and integrated renewable energy systems [1]. The flexibility of electric mobility to adapt to different energy sources enables countries to tailor solutions to local energy availability, thereby reducing their dependence on petroleum imports. However, this transition must consider the entire system, because if the electricity used to power EVs is produced from coal or other fossil fuels, the environmental benefits may be reduced or even lost [1].

Despite its promise, the transition to electromobility in developing countries faces many barriers. These barriers include the high initial cost of EVs, limited charging infrastructure, unreliable power supply, and a lack of public incentives [3,4]. Social and cultural resistance, combined with limited public knowledge about EVs and their benefits, also hinders widespread adoption [6]. Moreover, these regions often rely on imported vehicles and technology, which raises costs and reduces local ownership of innovation and production. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-dimensional strategy that includes public policy, economic incentives, infrastructure investment, and public education.

The motivation for this study stems from the urgent need to provide solutions that are environmentally sound, economically feasible, and socially acceptable for low- and middle-income countries. Electromobility has the potential to address all three of these challenges. For example, replacing fossil-fuel vehicles with electric ones can reduce illnesses caused by air pollution, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and create new job opportunities in green industries [7]. Electric two-wheelers (E2Ws), in particular, are highly suitable for developing contexts due to their affordability, efficiency, and compatibility with existing transport systems [8].

Despite growing literature on global EV transitions, limited research examines electromobility through the combined lens of economic constraints, infrastructural weaknesses, and policy uncertainty in developing countries. More specifically, existing studies primarily focus on single dimensions of electromobility adoption, such as technological performance, emissions reduction, or market trends, and are often based on evidence from developed economies. There is a lack of integrated, decision-oriented frameworks that simultaneously account for economic affordability, infrastructure reliability, energy system constraints, policy effectiveness, and social acceptance in developing countries. Furthermore, empirical insights from practitioners and experts operating in Global South contexts are underrepresented in the literature, which limits the applicability of existing findings to real-world policymaking in resource-constrained settings. Moreover, few studies incorporate expert perspectives from Global South practitioners to contextualize adoption barriers. This study addresses this gap by integrating expert interviews from developing countries with international EV indicators, thereby providing a multi-dimensional and context-sensitive assessment of electromobility that goes beyond technology-focused or region-specific analyses.

Unlike previous studies, which primarily offer descriptive reviews or isolated case analyses, this research develops a structured thematic framework that links the economic, infrastructural, policy, environmental, and social dimensions of EV adoption. The study further distinguishes itself by incorporating practitioner perspectives from Egypt, India, Kenya, and Nigeria, enabling a comparative understanding of adoption barriers across diverse developing-country contexts. This integrated qualitative–analytical approach provides decision-support insights that are largely missing in prior electromobility research focused on developing economies.

The objective of this research is to assess the current state of electromobility in selected developing countries and to evaluate its future prospects. Specifically, the study explores:

- The economic benefits and trade-offs of EV adoption;

- The feasibility of achieving large-scale market penetration;

- The environmental impact of EVs in urban contexts;

- Infrastructure readiness and government efforts to support the transition.

Based on the existing literature that has discussed this topic, an initial hypothesis can be formed to address the research questions. Later, this hypothesis can be tested through the secondary research phase, specifically through interviews.

Ref. [7] mentions various benefits associated with EVs in general in countries that are adopting them. The paper focused on the US economy as an example; however, the introduced theory can also be applied to other economies. Moreover, Ref. [8] discusses how, although many developing countries are not yet fully prepared for electric four-wheelers (E4Ws), electric two-wheelers (E2Ws) offer a viable solution, as they are more effective in terms of emission reduction. They are also more energy efficient, consuming 3–5 times less energy than conventional two-wheelers (which are very popular in developing countries). A comparative analysis of different electric mobility modes in terms of tank-to-wheel energy use is presented in Table 1, highlighting the clear efficiency advantages of E2Ws over other options. It clearly illustrates the substantial efficiency advantage of electric two-wheelers (E2Ws), which consume significantly less energy per kilometer than both gasoline-powered two-wheelers and electric four-wheelers. This finding supports the argument that E2Ws represent a pragmatic entry point for electromobility in developing countries with limited grid capacity and constrained infrastructure.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis among different electric mobility modes considering tank-to-wheel energy use.

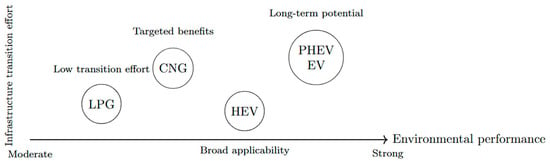

Furthermore, E2Ws and HEVs require minimal to no infrastructure modifications, as they can be integrated into existing networks. They also require significantly less operating and upkeep costs, and their prices are more affordable, especially for E2Ws [8]. Ref. [8] argues that developing countries would rather focus more on the E2Ws’ situation and infrastructure in the meantime, and leave the larger investments for the E4Ws’ infrastructure for the extended term, as it would only benefit the rich currently. Figure 2 illustrates the potential energy and emissions savings for various mobility modes, considering infrastructure investment costs. This comparison highlights why infrastructure-light technologies, such as E2Ws and PHEVs, are more suitable for early-stage electrification strategies in developing countries.

Figure 2.

Comparative evaluation of alternative vehicle technologies based on infrastructure transition effort and environmental performance.

The study results of [6], based on literature reviews conducted in India, conclude that there is a significant gap in awareness, both environmental and in terms of EVs in general, between developing and developed countries. In the paper’s opinion, such a lack of understanding would hinder any attempts at EV adoption in the country if not addressed.

Last but not least, Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) provide a practical solution for developing countries with weak or limited electricity grids. Research shows that smart PHEV charging can move demand to off-peak times. It can help stabilize microgrids and lower peak loads without needing immediate, large-scale grid expansion. This means PHEVs can significantly cut fuel use and emissions while allowing electricity infrastructure to grow more steadily [9,10].

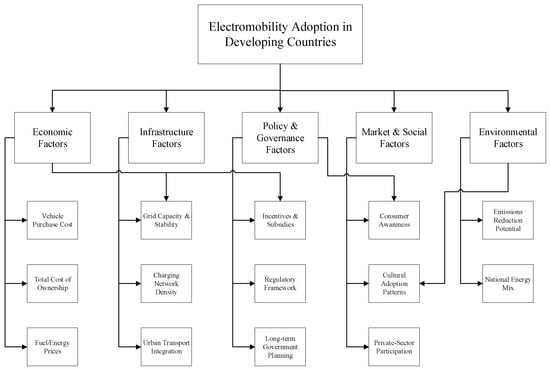

To provide readers with a clear understanding of how economic, infrastructural, policy, environmental, and social factors collectively shape EV adoption, Figure 3 presents a conceptual flowchart summarizing the key determinants of electromobility in developing countries. Unlike prior conceptual models, Figure 3 integrates economic, infrastructural, policy, environmental, and social dimensions based on both literature synthesis and expert interview insights, offering a context-sensitive decision-support perspective for developing countries.

Figure 3.

Key factors influencing electromobility in developing countries.

Overall, this study contributes to the existing literature by addressing a critical gap in integrated, context-aware electromobility research for developing countries through a combined qualitative and analytical decision-support framework. Unlike earlier reviews that focus solely on descriptive summaries, this paper offers a contextualized decision-support perspective, drawing on insights from practitioners in Egypt, India, Kenya, and Nigeria. It also presents a multi-dimensional conceptual flowchart that links infrastructure reliability, energy systems, consumer behavior, and policy incentives. This analytical perspective was missing in previous work on developing countries. This combined qualitative and analytical framework offers valuable methods for understanding EV adoption in resource-limited settings.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a comprehensive review of the relevant literature on electromobility with a focus on developing countries. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, including the research type, sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques. Section 4 discusses qualitative research design and thematic key findings from expert interviews. Section 5 provides an in-depth analysis and interpretation of the results by thematic analysis. Section 6 is the discussion part. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study by summarizing the key insights and offering practical recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders seeking to promote sustainable transport systems in developing economies, while suggesting further research directions.

2. Literature Review

Electromobility, the transition from internal combustion engine vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs), has been extensively discussed within the context of sustainable development, climate action, and the future of urban mobility. Initially, the academic literature concentrated predominantly on electromobility in developed countries, exploring mature markets with well-established infrastructure, stable regulatory environments, and high per capita income. However, recent studies emphasize the importance of understanding electromobility in the developing world, where the contextual challenges—economic, political, infrastructural, and social—are significantly different. Yet, the need for sustainable mobility solutions is equally, if not more, urgent.

In the early 2000s, Ref. [2] highlighted that a substantial portion of global automotive production and sales already came from outside the traditional “triad” markets of North America, the EU, and Japan. This finding, even two decades ago, was a call to action to recognize and research the roles of developing countries in global transportation systems. Yet, for many years, research remained heavily biased toward the Global North. Refs. [11,12], for instance, focused primarily on technological innovations, policy mechanisms, and consumer behavior in developed economies. Their contributions were substantial but lacked relevance in environments characterized by infrastructural gaps, low-income levels, and weak institutional capacities.

A notable shift has occurred more recently, with an increasing scholarly interest in the Global South. Ref. [13] conducted a critical review highlighting the lack of value chain-focused research for EV promotion in developing nations. They emphasized the need for holistic assessments that take into account localized factors, such as energy reliability, government capacity, and consumer affordability. Refs. [6,14] introduced frameworks for evaluating EV adoption using PESTEL criteria—Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal factors. These frameworks enable a multidimensional understanding of electromobility’s opportunities and barriers in complex contexts, such as India, Indonesia, or Nigeria.

A central theme across recent literature is the diversity of EV types and the corresponding infrastructural requirements. Ref. [8] made a compelling case for focusing on electric two-wheelers (E2Ws) and hybrid EVs (HEVs) in developing countries. These vehicles, unlike full-size electric four-wheelers (E4Ws), demand minimal grid upgrades, are cost-effective, and align better with the income patterns and travel behaviors of citizens in low- and middle-income nations. Their findings suggest that governments achieve higher returns on investment by promoting E2Ws and building shared micro-mobility infrastructure before embarking on high-cost, car-centric EV transitions. Additionally, the authors present comparative energy and emissions data that show E2Ws to be significantly more efficient per passenger-kilometer than traditional motorbikes.

In addition to well-known international manufacturers, many regions in the Global South depend on local electric two-wheeler (E2W) makers. Their products are designed to be affordable and withstand more challenging road and weather conditions. Local companies, such as Italika from Mexico, AKT from Colombia, and Motomel from Argentina, dominate the market. They mainly compete by keeping costs low and providing easy maintenance. These vehicles often employ simpler suspension systems, less expensive lithium or lead-acid batteries, and modular parts that can be repaired through informal networks. This accessibility is crucial, but some industry reviews suggest these models may not compare well with those from Japan, South Korea, and the EU in terms of durability, battery management, and safety features. Although few peer-reviewed engineering studies highlight a gap in the academic literature, market analyses consistently show that local E2Ws offer practical and cost-effective designs. These designs better meet the needs of developing regions than many expensive imports [8,15].

The infrastructural challenges remain a recurring concern throughout the literature. Ref. [4] pointed out that charging infrastructure in developing countries is scarce and unevenly distributed, with a primary concentration in affluent urban neighborhoods. Moreover, electricity grids in many African and South Asian nations are often unreliable, which compounds the operational uncertainty for EV users. Ref. [16] underscored that the success of commercial EVs, especially in fleets such as taxis and delivery vans, hinges on the availability of fast and accessible charging options, which are largely lacking in places like Manila or Nairobi.

Government incentives and public–private partnerships emerge as crucial enablers in the transition to electromobility. Ref. [17] documented how the European Union, through stringent CO2 targets and generous subsidies, managed to catalyze EV uptake across member states. While this model is instructive, its direct applicability to developing nations is limited without adaptation. Refs. [18,19] proposed that tailored policies—including reduced import duties, targeted subsidies, pilot demonstration programs, and capacity-building workshops—are more effective in fragile policy environments. India’s FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles) scheme is frequently cited as an exemplar policy that combines subsidy support with industrial localization strategies.

Environmental benefits of EVs are widely acknowledged, but the literature also cautions against oversimplification. Refs. [20,21] emphasized that the net environmental impact of EV adoption depends heavily on the source of electricity. In countries where the power mix is dominated by coal or other fossil fuels, the reduction in tailpipe emissions may be offset by increased emissions upstream. Nevertheless, the potential for renewable integration—particularly solar and wind—is substantial in many equatorial and tropical countries. As Ref. [14] suggested, coupling EV rollout with renewable energy policy can maximize the decarbonization potential of electromobility.

The economic implications are multifaceted. Ref. [7] found that in the United States, EVs offer lifetime cost savings in terms of fuel and maintenance. These findings, when cautiously extrapolated to developing countries, suggest that while upfront costs are prohibitive, long-term economic benefits exist, especially when combined with financial support mechanisms. Ref. [22] argued that shifting to a value-based model, where companies focus on selling mobility services rather than vehicles, may help reduce ownership burdens and improve affordability for lower-income populations.

Cultural attitudes and consumer perceptions are also pivotal. Ref. [6] highlighted the stark contrast between environmental awareness in developed and developing countries. In many developing regions, limited exposure to climate change discourse and low trust in government programs have contributed to skepticism toward EVs. Awareness campaigns, hands-on demonstrations, and integrating EVs into public transport systems are suggested as potential solutions. Similarly, Ref. [23] emphasized that regulatory clarity and consumer protection mechanisms are vital to overcoming psychological and market-entry barriers.

Recent research indicates that future transportation developments in developing countries will increasingly integrate with connected and automated vehicle (CAV) technologies. Mixed-traffic environments, where electric vehicles (EVs), CAVs, and conventional vehicles interact, create new challenges for capacity, safety, and intersection performance. Emerging studies, such as [24], indicated that mixed traffic with CAVs significantly impacts the capacity of minor-road priority intersections. This information is essential for cities that expect to see growth in both EVs and smart mobility. Considering these viewpoints ensures that electromobility strategies address energy and cost factors, as well as operational and traffic management issues, in quickly urbanizing areas.

While the academic literature is expanding, significant gaps persist. A lack of longitudinal data remains, preventing the capture of the real-world performance and user experience of EVs in the Global South. Most studies rely on simulations, economic modeling, or extrapolated case studies from high-income countries. Furthermore, there is a disproportionate focus on urban settings, even though rural populations in developing countries also contribute significantly to emissions and face the most significant transport challenges.

Recent contributions from the Future Transportation journal further advance the understanding of electromobility in emerging contexts. Ref. [25] emphasized that successful EV adoption depends not only on deploying vehicles but also on integrating smart infrastructure, promoting energy-efficient systems, and ensuring equitable access for diverse urban and rural populations. These findings highlight the importance of addressing both technological and socio-infrastructural dimensions to achieve effective and sustainable electromobility solutions. They analyzed innovative EV development and highlighted the critical role of charging infrastructure even in regions with growing adoption rates, emphasizing that infrastructure planning must accompany vehicle deployment. Similarly, Ref. [26] reviewed Transportation 5.0 concepts, underscoring the integration of advanced mobility solutions, digitalization, and sustainable practices, which collectively support the scalable and efficient implementation of EVs. These studies emphasize the importance of comprehensive planning that integrates technological, infrastructural, and policy measures to facilitate successful transitions to electromobility in developing countries.

To summarize, the literature reveals a growing but still fragmented body of research on electromobility in developing countries. Emerging studies address infrastructural, economic, technological, policy, and cultural factors, yet more nuanced, context-specific research is required. The field is transitioning from exploratory reviews toward empirical case studies and pilot evaluations. As global commitments to climate action intensify, the urgency to develop scalable, affordable, and locally adapted electromobility solutions for the developing world becomes even more pressing. This study aims to contribute to this emerging discourse by synthesizing findings from existing research, analyzing barriers and enablers, and presenting grounded recommendations tailored to the specific conditions.

Lastly, a further limitation evident in the literature is the scarcity of peer-reviewed comparative studies evaluating locally produced E2Ws in regions such as Latin America and Africa, which restricts comprehensive technical comparisons with leading manufacturers from Japan, South Korea, the EU, and the United States.

To gather and clarify the existing knowledge for this study, we created a structured literature review table. Table 2 summarizes the most significant publications on electromobility, electric vehicle adoption, charging infrastructure, policy frameworks, socio-technical transitions, and methodological foundations. By organizing these works by date, this table shows how ideas have changed over time. It transitions from early discussions about value-chain limits and socio-technical transitions to recent studies on consumer behavior, digital discussions, policy guidance, and the integration of technology. The table also highlights key methods employed, the main findings of each study, and the gaps still present in the literature. This overview not only provides context for the current research but also demonstrates how this study builds upon and expands upon previous work. The final row highlights the unique contributions of this paper.

Table 2.

Literature Review in Summary.

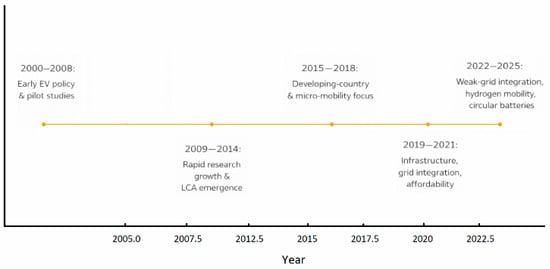

In addition to the structured summary table, a chronological timeline was developed to visualize the evolution of electromobility research and highlight the shifts in scholarly focus over the past two decades. This timeline illustrates how early studies (2000–2008) concentrated primarily on pilot projects and foundational EV policy in high-income regions, followed by a rapid expansion of technical and environmental assessments during 2009–2014. From 2015 onward, research increasingly incorporated developing-country perspectives, micro-mobility, and socio-technical factors. More recent work (2019–2021) has emphasized charging infrastructure, grid integration, and economic feasibility, while studies from 2022 to 2025 reveal growing attention to weak-grid adaptation strategies, hydrogen-based mobility pathways, circular battery systems, and context-specific analyses in the Global South. Figure 4 presents this trajectory graphically to help readers understand how the field has matured and how the present study aligns with these evolving research directions. This timeline situates the present study within the most recent phase of electromobility research, which is increasingly emphasizing weak-grid adaptation, micro-mobility, and context-specific analysis in developing countries.

Figure 4.

Evolution of electromobility research (2000–2025).

3. Methodology and Data Collection Framework

3.1. Research Procedure and Samples

This study employs a qualitative research approach, comprising expert selection, semi-structured data collection, thematic analysis, and contextual validation through secondary indicators.

The methodology employed in the study is meticulously crafted to collect and analyze data systematically. It aims to grasp the perspectives and opinions of automotive industry professionals regarding the adoption and market potential of EVs in developing nations. Qualitative research is characterized by its intent to comprehend multiple facets of social existence, often producing qualitative rather than quantitative data for analysis. This enables the generation of comprehensive descriptions of processes, mechanisms, or settings, as well as the characterization of participant perspectives and experiences.

This study employs a qualitative approach, utilizing semi-structured interviews to gather in-depth insights from individuals working in the automotive industry. Qualitative methods are particularly well-suited for exploring complex phenomena and gaining a profound understanding of participants’ experiences, beliefs, and motivations. The semi-structured interview format enables interviewers to pose questions flexibly, adapting their queries in response to the flow of conversation and delving deeper into reactions as needed. This ensures that the collected data is rich and captures the nuanced views of industry professionals.

To ensure a diverse range of viewpoints, participants were selected from multiple countries, with a focus on emerging regions. The selection included professionals from various sectors of the automotive industry, including manufacturers, suppliers, and market analysts. This diversity ensures that the data reflects a broad spectrum of experiences. Recruitment was conducted through professional networks, industry events, and social media, with a deliberate effort to include participants from diverse developing countries. The sample comprised individuals with varying levels of expertise and roles within the industry, offering a diverse range of thoughts and insights.

The countries were chosen because they follow different paths in the transition to electric vehicles. Egypt is interested in policy but lacks infrastructure. India is rapidly electrifying two- and three-wheelers. Kenya has the fastest-growing electric vehicle market in Africa. Nigeria faces challenges due to a weak grid, but it is also developing emerging pilot projects. Interviewees were selected through purposive sampling to represent different roles in procurement, logistics, manufacturing, and policy awareness. This method offers a comprehensive view of electric vehicle readiness and the associated challenges.

Ethical considerations were a central focus of the study. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, their role, and their rights, and informed consent was obtained before the commencement of interviews. Measures were taken to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of participants. The transcripts were anonymized, and any identifying information was removed or replaced with pseudonyms. All data was securely stored, and access was restricted to the research team.

The expert sample is intentionally limited and primarily concentrated in Egypt, reflecting feasibility constraints and the study’s exploratory qualitative focus. Experts were selected through purposive sampling based on professional experience in transport planning, energy systems, and EV policy in developing countries. Although representation from Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia is more limited, thematic saturation was reached, as no new insights emerged after the sixth interview. The semi-structured interview guide included questions on policy barriers, economic feasibility, infrastructural constraints, and consumer acceptance. To complement the qualitative findings, the study integrates key quantitative indicators (e.g., EV market share, charging density, cost trends) from the IEA and national reports to contextualize the interview insights.

3.2. Research Instruments

The primary research instrument used in this study was a semi-structured interview guide designed to elicit expert insights on the adoption of electric vehicles in developing countries. The guide was developed based on an extensive literature review and consultations with subject matter experts to ensure alignment with the study objectives.

Data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews using platforms such as Zoom, which provided scheduling flexibility and enabled participation from various geographic regions. The interview guide was developed through a thorough review of existing literature and consultations with subject matter experts. Key discussion points included current market conditions, where participants offered an overview of the automotive market in their countries with a focus on EVs, including market size, growth trends, public awareness, and EV-related infrastructure. Barriers to adoption were discussed in depth, with participants identifying economic constraints, regulatory challenges, technological limitations, and cultural perceptions as key factors that hindered adoption. They also proposed potential solutions, including supportive government policies, industry initiatives, technological innovations, and public engagement strategies. Furthermore, participants shared their future outlooks on EV market potential, anticipating trends in growth, technology, and the influence of global developments on local markets. Interviews lasted between 45 min and an hour, and were recorded and transcribed with the participant’s consent.

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the interview data, involving the identification and interpretation of recurring patterns and themes. This method is particularly well-suited to handle complex and varied qualitative datasets, and was chosen to ensure a thorough and meaningful understanding of the collected information.

Qualitative research is sometimes perceived as unscientific due to its focus on narratives and participant interaction, which can lead to skepticism about its credibility. As [27] suggests, qualitative findings may either align with common sense and seem trivial or contradict it and be dismissed as implausible, creating a dilemma where neither outcome is entirely accepted. Ref. [28] addressed this paradox by offering a detailed critique of these perceptions.

At the core of qualitative research lies the investigation of how individuals interpret their real-life experiences in their own terms, analyzed within the frameworks of behavioral sciences such as psychology, sociology, political science, education, healthcare, or business. These interpretations often take the form of narratives, such as interview responses or personal accounts. Unlike quantitative research, which emphasizes abstract concepts and measurable variables, qualitative research explores the subjective experiences of individuals and often uncovers unexpected findings.

According to [29], qualitative research empowers participants by allowing them to voice their experiences and grounding the research outcomes in their perspectives. This methodology emphasizes understanding subjective viewpoints, collaborating with participants to reconstruct their realities, and using inductive reasoning where theories emerge during or after data analysis. Ref. [30] highlights that the primary goal is to understand how individuals derive meaning from their actions and experiences.

Qualitative methods often involve observing and documenting behavior in natural settings or through the collection of participant narratives. Researchers aim to adopt the participants’ perspectives to grasp their experiences fully. The flexible and exploratory nature of qualitative research allows it to adapt to emerging themes and develop new hypotheses, emphasizing credibility over rigid measurement or sampling methods [31]. The characteristics of idealized qualitative methodology are illustrated in Table 3.

This approach typically avoids experimental designs, focusing instead on real-world contexts and prioritizing authenticity, relevance, and practical utility. Studies often examine past events using ex post facto designs. As noted by [32], qualitative research is inherently flexible, beginning with a genuine interest or question, and theories emerge through the process of data collection and analysis. Ref. [33] observed that this emic approach centers on understanding how people perceive and make sense of the world in their daily lives. It is typically micro-analytical, addressing specific problems in particular contexts.

Three dimensions help define the qualitative approach: reality construction, key questions, and its empirical nature. Reality construction asserts that individuals build their own realities from personal and social experiences, resulting in diverse perspectives. Key questions ask how people make sense of their environment, understand their roles, act based on their constructed realities, and communicate these understandings. The empirical dimension emphasizes learning through observing behaviors and collecting narrative data, which are interpreted using social science concepts and then generalized where appropriate.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Idealized Qualitative Methodology [34].

Table 3.

Characteristics of Idealized Qualitative Methodology [34].

| Dimension | Qualitative Approach |

|---|---|

| Design | Non-Experimental |

| Setting | Field |

| Data Collection | Collection of “narrative,” either existing or new |

| Data Type | Descriptive (e.g., interview protocols, written records, videos) |

| Analysis | Analysis aimed at revealing meaning |

| Generalization | Focus on generating hypotheses. |

In summary, while conventional quantitative methodologies align with established views of the scientific method, qualitative research—despite sometimes being perceived as akin to everyday conversation—provides rigorous, insightful understandings of real-world phenomena. As Refs. [27,28] suggest, the tension between common sense and scientific insight remains a challenge, yet qualitative research continues to offer indispensable contributions to understanding complex human behaviors and social dynamics.

4. Qualitative Research Design and Thematic Key Findings

This section presents the study’s results, integrating expert interview insights with the structured methodology provided by the Research Onion [35]. Each layer of the onion is discussed in full, followed by a thematic analysis of the interview findings, organized into five main areas: economic benefits, market dominance potential, CO2 emissions impact, infrastructure development, and government initiatives. These areas are further explored in the next section.

4.1. Philosophy

The interpretivist research philosophy was chosen to understand the subjective meanings and contextual variations surrounding the adoption of electromobility in developing countries. This philosophical stance is well-suited for examining the lived experiences, perceptions, and cultural nuances associated with the implementation of electric vehicles (EVs). Since electromobility is not merely a technological innovation but a socio-political and economic transition, interpretivism allowed for a flexible approach that captured stakeholders’ interpretations of emerging trends, constraints, and local challenges.

For example, Expert 1 emphasized the cultural dimension of technology acceptance in developing countries: “It’s not just about providing EVs—it’s about shifting mindsets, addressing people’s fears, and making them feel part of the solution.” In a similar vein, Expert 7 highlighted that consumer perceptions in Egypt are shaped less by environmental narratives and more by trust in affordability and infrastructure readiness, reinforcing the need to interpret adoption through localized social and economic realities. Expert 5 added that policies cannot be evaluated solely on their technical merits, since their success depends on how well they resonate with people’s lived circumstances, especially in relation to financial barriers and governmental trust. Expert 6 further emphasized that EV adoption must be studied within the broader socio-political context, where government priorities and national strategies have a profound influence on individual willingness to adopt.

This philosophical lens enabled the analysis to go beyond generalizations and focus on how electromobility is perceived through various cultural, institutional, and infrastructural contexts.

4.2. Approach

An inductive approach was employed, allowing the research to develop theories and patterns based on observations and qualitative insights rather than testing pre-established hypotheses. Given the diverse socioeconomic and infrastructural landscapes of developing countries, the inductive method helped generate emergent understandings from the collected data.

Participants frequently returned to previously unconsidered factors—such as societal status associated with EV ownership or distrust in government energy programs—further validating the need for a bottom-up, exploratory design. As Expert 2 observed, “EVs in Cairo mean something completely different than in Nairobi. You have to understand what people see when they look at an electric car.” Expert 7 reinforced this by noting that adoption patterns cannot be assumed to follow Western trajectories, since in Egypt, consumers frame EVs not only as environmental tools but also as symbols of economic positioning. Expert 5 emphasized that only through iterative engagement with local narratives can hidden barriers, such as affordability and perceptions of reliability, be identified and addressed. Similarly, Expert 6 emphasized that the inductive method is crucial for revealing how national policies are translated—or fail to be translated—into everyday practices, particularly when citizens’ lived realities diverge from official narratives.

4.3. Research Strategy

Semi-structured interviews were selected to allow both guidance and flexibility. Interviews were conducted with six stakeholders from diverse professional backgrounds in Egypt, Kenya, India, and Nigeria, including energy consultants, policy makers, and transport specialists. Each interview lasted between 45 and 60 min and was audio-recorded with consent. The interviewees’ profiles are reported in Appendix A (Table A1).

The semi-structured format allowed the researcher to explore emerging topics while also addressing predetermined themes such as economics, the environment, and infrastructure. Interviewees often brought up case-specific insights, such as government collaboration in Lagos or the rollout of charging stations in Pune. This method was instrumental in capturing the dynamic and context-sensitive nature of electromobility in under-resourced environments.

4.4. Research Choice

Given the focus on in-depth understanding, a mono-method qualitative design was selected. All data were collected through semi-structured interviews, transcribed, and analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. This choice allowed for rich, interpretive exploration without the constraints of quantitative modeling or survey standardization.

Although some numerical estimates were discussed (e.g., investment levels, adoption forecasts), the purpose was not to measure but to gain an understanding of the topic. This qualitative lens helped in exploring not just what changes are occurring, but why and how key actors perceive them.

4.5. Time Horizon

Although data collection took place over a limited timeframe, participants were encouraged to reflect on both past experiences and future projections related to electromobility. This enabled a longitudinal perspective, mapping changes in perception, policy, and infrastructure over time.

Expert 3 reflected: “When I started in the energy sector ten years ago, no one was talking about electric vehicles. Now, governments are setting targets for 2030 and beyond.” Thus, although the study design was technically cross-sectional, the analysis incorporates longitudinal interpretations.

4.6. Techniques and Procedures

Thematic analysis was employed to process the qualitative data. Interviews were transcribed verbatim, coded, and categorized into five overarching themes: (1) economic benefits, (2) market dominance potential, (3) CO2 emissions reduction, (4) infrastructure readiness, and (5) government initiatives. Codes were derived inductively and refined iteratively. The process followed Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework for thematic analysis.

5. Interviews’ Thematic Analysis

The following section brings together the voices of key stakeholders to paint a multidimensional picture of how electromobility could transform developing countries. From the promise of reduced fuel import costs and new job opportunities to the vision of EVs becoming the norm in bustling cities, the interviews reveal both optimism and realism. Stakeholders emphasize the environmental benefits of reducing CO2 emissions, while cautioning that actual gains depend on the effective integration of clean energy. They also underscore the pressing need for charging infrastructure, reliable grids, and skilled maintenance networks to sustain this transition. Underpinning it all is the role of policy: strategic subsidies, public–private partnerships, and awareness campaigns that can bridge the gap between possibility and reality. Together, these perspectives outline the economic, environmental, and social foundations on which a viable EV future can be built.

5.1. Economic Benefits

A recurring theme across all interviews was the economic viability of electromobility. Expert 1 emphasized that EVs reduce the financial burden of importing fossil fuels: “Developing nations spend millions on fuel imports annually. EVs cut that down, allowing funds to be redirected to education, health, or infrastructure.”

Expert 7 reinforced this point, highlighting that in Egypt, shifting to EVs could redirect substantial national resources toward infrastructure development and social programs, while also supporting the growth of domestic EV manufacturing. Expert 5 added that local production of EV components and the establishment of charging infrastructure can generate skilled employment opportunities, boosting both industrial growth and the workforce. Expert 6 offered a more cautious view, noting that in Egypt, short-term economic benefits may be limited due to high energy costs and the current small EV market, but emphasized the long-term potential if infrastructure and energy supply challenges are addressed.

Stakeholders also stressed the potential for job creation. Expert 4 noted that the EV value chain—from battery manufacturing to maintenance—creates employment opportunities: “We’re not just talking about mechanics, but software engineers, infrastructure planners, electricians.” India’s FAME initiative was cited by multiple respondents as a successful example of economic stimulus through EV adoption, particularly in terms of manufacturing and local supply chain development.

Expert 1 added that reducing dependency on oil imports could shield economies from volatile global oil prices: “We saw what happened during COVID-19 and the Ukraine war—price spikes cripple vulnerable economies. EVs provide energy independence.”

Expert 7 similarly emphasized that decreased reliance on oil imports not only stabilizes national economies but also fosters energy self-sufficiency. Expert 5, on the other hand, emphasized the importance of aligning EV adoption with renewable energy investments to achieve long-term economic resilience. Expert 6 reminded that achieving these benefits requires addressing the upfront costs and grid readiness, which are currently significant barriers in Egypt.

5.2. Market Dominance Potential

Interviewees suggested that EVs are more likely to become dominant in urban areas due to population density, shorter travel distances, and existing infrastructure. Expert 1 stated, “In cities, people are ready. They’re aware, and they value clean air. But in rural areas, it’s still a luxury concept.”

Expert 7 similarly noted that metropolitan regions in developing countries, such as Cairo, present a more favorable environment for EV adoption due to concentrated infrastructure and public awareness. In contrast, rural areas face slower adoption because of limited charging networks and affordability constraints. Expert 5 emphasized that government incentives and public–private partnerships are crucial in bridging these urban-rural disparities. Expert 6 added that in Egypt, EV dominance is unlikely in the near term without significant investment in grid stability and infrastructure expansion, particularly outside major cities.

Government subsidies and tax incentives were viewed as critical enablers of growth. Expert 2 remarked, “Without financial support, we’re just telling poor people to buy Tesla products. That’s not realistic.” Infrastructure availability was highlighted as a precondition for market expansion. Expert 4 emphasized: “Adoption is linked to trust—if people can’t find a charging point, they won’t risk switching.”

Stakeholders envisioned EV market dominance in three phases: short-term (0–5 years), focused on urban early adopters; medium-term (5–15 years), expanding with infrastructure support; and long-term (15+ years), when mass affordability and grid upgrades make EVs standard across regions. Expert 7 projected a similar phased adoption timeline, with gradual urban uptake leading the way, while Expert 5 emphasized that synchronized policy, infrastructure, and public awareness are critical to achieving this trajectory. Expert 6 cautioned that without addressing Egypt’s energy and infrastructure challenges, even a phased approach could face substantial delays.

5.3. CO2 Emissions Impact

Environmental sustainability was unanimously acknowledged as a motivator for EV adoption. Expert 1 explained: “The public health benefits of reducing tailpipe emissions are immediate and visible in congested cities.” However, respondents also warned that the environmental gains are conditional. Expert 3 noted: “If your grid is coal-powered, your EV is a coal-powered car.”

Expert 7 emphasized that the full environmental benefits of EVs in developing countries depend heavily on integrating renewable energy into the grid, as urban adoption alone will not significantly reduce CO2 emissions. Expert 5 added that pairing EV adoption with investments in solar and wind infrastructure is crucial to ensure that emission reductions are meaningful and effective. At the same time, Expert 6 cautioned that in countries like Egypt, where only a fraction of electricity comes from renewable sources, EVs may initially provide limited carbon reduction, despite cleaner urban air.

Integration with renewable energy was identified as essential. Stakeholders emphasized the need for concurrent investment in solar, wind, and smart grids. Technological and economic barriers—such as high battery costs and a lack of R&D—were identified as threats to achieving CO2 reduction goals.

5.4. Infrastructure Development

The lack of infrastructure was described as the most urgent challenge. “We can’t roll out EVs without somewhere to charge them,” said Expert 4. Urban areas were said to have some infrastructure, but rural and peri-urban regions were underserved.

Expert 7 stressed that establishing an extensive network of charging stations, including fast chargers, is critical, and recommended starting in urban centers before gradually expanding to rural areas. Expert 5 added that modernizing the electrical grid and creating specialized repair and maintenance facilities are essential to building public trust in EVs. Expert 6 highlighted that in Egypt, the limited number of public charging points and frequent grid instability present significant hurdles to rapid EV adoption, indicating that substantial investment and planning are required before the infrastructure can support widespread use.

Several interviewees highlighted the importance of grid readiness. “If we don’t upgrade the grid, we’ll see outages,” said Expert 1. Establishing service centers and training technicians were also mentioned as necessary to support the growing EV fleet.

Viable approaches included global partnerships and pilot projects. Expert 3 advocated for knowledge-sharing alliances, while Expert 4 recommended starting small and scaling based on performance evaluation.

5.5. Government Initiatives

Participants noted that policy plays a decisive role in driving or stalling EV adoption. Expert 1 referenced China’s strategic subsidies and India’s FAME initiative as exemplary cases: “They didn’t wait for the market—they built it.”

Expert 7 highlighted that in addition to subsidies and tax incentives, governments should actively promote collaborations between the public and private sectors, while also investing in renewable energy to ensure the long-term sustainability of EV adoption. Expert 5 added that enduring policies, such as technology transfer agreements and consistent financial incentives, are crucial for emerging countries to become competitive in EV production. Expert 6 noted that in Egypt, although the government has reduced taxes on EVs and promoted “Green Economy” plans, the lack of comprehensive and effective policies has limited the market impact, showing that policy consistency and scale are key to successful adoption.

Incentives such as tax breaks, import tariff reductions, and government co-financing were viewed as necessary to make EVs financially viable. Public–private partnerships were also endorsed. “Governments don’t have to do it all,” said Expert 2, “they just have to invite others to help.”

Educational campaigns were another standard recommendation. “You can’t expect people to adopt EVs if they don’t know what they are,” said Expert 4. Awareness-building and trust enhancement were seen as vital components of any national electromobility strategy.

6. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that the transition to electromobility in developing countries is shaped not only by technological readiness or global trends, but also by deeply embedded socio-economic structures, governance dynamics, and cultural narratives. While the global EV market is expanding rapidly, fueled by falling battery prices and aggressive climate 11 policies in developed nations, the pathways available to low- and middle-income countries remain uniquely constrained. This section interprets the key results through a broader analytical lens, comparing them with existing literature and offering a critical perspective on their implications.

A comparison of key electromobility indicators across five representative emerging economies, Egypt, India, Kenya, Indonesia, and Nigeria, is shown in Table 4. These countries were chosen because they represent different levels of EV penetration, infrastructure readiness, and policy maturity. Several interview participants also mentioned Egypt, India, Kenya, and Nigeria. The patterns observed in Table 4 are consistent with the expert interview findings, reinforcing the conclusion that grid reliability, policy consistency, and affordability are the dominant constraints across diverse developing-country contexts.

Table 4.

Comparative EV indicators across selected developing countries.

The comparison reveals four recurring patterns: (1) EV market shares are low in most developing countries. India and Kenya are growing the fastest, especially in the two-wheeler and three-wheeler segments; (2) incentive structures differ widely, from comprehensive subsidy programs in India to minimal national support in Nigeria; (3) the density of charging infrastructure is generally limited outside major cities, often due to weak or unstable grids; and (4) the main barriers in all countries include high upfront costs, unreliable grids, and inconsistent policies. These differences among countries support the interview findings that EV adoption cannot follow one universal model. Policy design, infrastructure investment, and market structure depend heavily on the local context.

6.1. The False Universality of Technological Diffusion

Many studies from the Global North implicitly assume that the barriers to EV adoption are universal—primarily technical and economic. Yet, this research confirms that the challenges in developing contexts are multidimensional and systemic in nature. In line with [36], who argue that energy transitions are “as much social and political as they are technical,” the expert interviews show that infrastructure and cost constraints are symptoms of deeper institutional and developmental imbalances.

For instance, while charging infrastructure is often cited as a technical gap, the underlying issue in many cases is weak governance capacity to plan and coordinate national infrastructure development. Similarly, high vehicle prices are not merely a result of global cost curves, but also of localized factors such as tariff regimes, currency volatility, and the absence of financing mechanisms.

Another technological pathway gaining attention in the literature is the use of hydrogen fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Research shows their benefits for long-distance and heavy-duty applications due to their high energy density and quick refueling. However, adopting FCEVs in developing countries is limited by the need for a separate infrastructure system. This system encompasses the production of green hydrogen, as well as facilities for compression, storage, secure transportation networks, and dedicated refueling stations. Large-scale projects, such as the NEOM Green Hydrogen Project in Saudi Arabia, demonstrate potential feasibility and lower long-term costs. Still, the high costs and safety needs of hydrogen infrastructure create significant short-term challenges. As a result, studies suggest that FCEVs are best seen as long-term options rather than immediate replacements for BEVs or PHEVs in resource-limited settings [37,38,39].

6.2. The Policy Vacuum and Fragmentation of Authority

One of the most striking themes across interviews was the lack of a unified, enforceable electromobility strategy. Despite high-level interest in sustainability, many governments in the Global South have failed to articulate clear policies on EV imports, charging standards, safety regulations, or fiscal incentives. This ambiguity discourages private investment and leads to market fragmentation.

This phenomenon is not unique to Egypt or the North African region. Studies from India, Indonesia, and Kenya reveal similar challenges, where overlapping responsibilities among ministries, unclear mandates, and short-term political cycles hinder progress [40]. Without strong institutional coordination, electromobility risks becoming an elite-driven project with little impact on mass transit or public well-being.

Moreover, policy inertia reinforces a passive mindset in the private sector. As the interviews suggest, many firms are “waiting for a signal” from the government—whether in the form of subsidies, infrastructure rollout, or public procurement programs. This indicates a broader issue: the absence of a visionary public sector willing to act as a market-shaping agent, rather than merely a market follower.

6.3. Local Manufacturing and Skill Ecosystems

An under-discussed, yet crucial, dimension of the EV transition in developing contexts is the role of industrial policy. All interviewees highlighted the fragility of the local supply chain, the lack of maintenance infrastructure, and the shortage of skilled technicians. These findings resonate with the argument made by [41], who caution that unless countries invest in the “missing middle”—the connective tissue between high-level vision and grassroots delivery—their sustainability transitions will remain fragile.

Without capacity for battery assembly, component production, or localized software engineering, countries become dependent on expensive imports, which limits affordability and economic spillovers. Moreover, the inability to train a new generation of EV mechanics, engineers, and charging technicians constrains scalability. This opens an urgent conversation about green job creation—not only in EV driving but also in support ecosystems such as logistics, repair, and digital infrastructure.

6.4. Interdependencies Between Charging Infrastructure and Energy Systems

EV charging infrastructure in developing countries is closely linked to the state of the electricity grid. In areas with weak grids, unmanaged charging demand can overload local feeders, cause voltage drops, and increase the risk of brownouts. Interviewees in Egypt reported that frequent outages at the distribution level erode confidence in the reliability of EV charging and lead to hesitation among private users and fleet operators.

Grid instability directly affects consumer trust. When users face blackouts or voltage fluctuations, they view EVs as risky, inconvenient, or not suitable for their daily transport needs. This cycle—weak grids leading to lower adoption rates and low adoption slowing infrastructure investment—was highlighted in several interviews.

Examples from other countries show the need for coordination between grid and transport systems. In Kenya, solar and mini-grid projects help create renewable charging solutions, which lessen reliance on overwhelmed distribution networks [25]. In India, smart-grid and managed-charging trials show how time-of-use pricing and coordinated load control can ease peak demand and postpone expensive grid upgrades [9].

In summary, successful EV transitions in developing countries must include assessments of grid impacts, smart-charging strategies, and renewable-supported charging stations. This approach ensures that infrastructure deployment aligns with grid capabilities, thereby fostering user confidence and trust.

6.5. Behavioral and Social-Psychology Drivers of EV Adoption

Perhaps most uniquely, the interviews shed light on the cultural framing of electromobility. The adoption of new technologies is not just a rational decision based on cost–benefit calculations; it is also a social and symbolic act. For many potential users, EVs are unfamiliar, seen as either aspirational or unreliable, and disconnected from their daily realities. Limited opportunities for experiential learning reinforce these perceptions: several interviewees noted a lack of test drives or public demonstrations, which prevents potential adopters from reducing uncertainty and contributes to fears about breakdowns and battery reliability.

Related to this, social norms around EVs remain weak in the studied countries because EV visibility in everyday life is low. Without examples from peers or neighbors, descriptive norms are not activated, meaning that EVs are not yet perceived as a regular or socially validated mode of mobility. This compounds existing concerns about affordability and risk. As some participants explained, many consumers focus on the upfront purchase price rather than the total cost of ownership, and this cognitive anchoring leads to the perception that EVs are financially out of reach—even when long-term operating costs may be lower.

These psychological and symbolic dynamics echo the work of [42], who emphasize that transitions are “culturally contested processes,” shaped by narratives of modernity, risk, and trust. In Egypt, as elsewhere, the image of a powerful, fuel-powered car remains dominant, while EVs are often viewed as experimental or elitist. Overcoming this perception will require not just education, but also emotional engagement, storytelling, and community-level demonstration projects.

In a 2025 UK-based study, researchers investigated adoption intentions among drivers lacking private parking—typically a group facing infrastructure constraints—and found that environmental motivations and positive social norms were more influential in shaping EV adoption intentions than perceived charging limitations. The authors recommend community-level interventions—such as EVs appearing at local green events, second-hand EV dealers hosting neighborhood presentations—to reinforce personal norms and facilitate emotional and social engagement with EVs [43].

Similarly, a 2025 analysis of EV discourse on Turkish social media revealed widespread positive sentiment and enthusiastic engagement, underscoring the role of storytelling and shared personal narratives in shifting cultural attitudes toward electric mobility [44].

Finally, a 2025 study on EV consumer expectations in dealership settings emphasizes that across different cultural contexts, transforming test-drives into immersive, emotionally resonant experiences—such as demonstrating reliable charging infrastructure, offering tailored tutorials, and listening closely to user anxieties—helps build empathy and trust, especially where EVs may be perceived as alien or elite [45].

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

The adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) in developing countries presents a compelling opportunity to address some of the most pressing global challenges, including energy security, economic development, and environmental sustainability. The transition to EVs offers a reduction in dependency on imported fossil fuels, which continues to place considerable strain on national budgets in many emerging economies (Expert 1, interview).

By shifting toward EVs powered by domestically sourced renewable energy, these nations can redirect financial resources toward critical areas such as education, infrastructure, and public health. Additionally, this transformation stimulates job creation across multiple sectors, ranging from charging infrastructure development and battery assembly to vehicle maintenance and digital mobility services. Success stories such as India’s FAME initiative and localized EV manufacturing efforts in Kenya demonstrate the dual impact of economic stimulus and industrial development when governments actively support the sector (Expert 2 & 5 interview).

From an environmental perspective, EVs contribute to significant reductions in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, particularly in dense urban centers where internal combustion vehicles are primary contributors to air pollution. The deployment of electric buses and ride-sharing EV fleets in cities like Bogotá and Nairobi has already resulted in measurable improvements in air quality (Expert 1 & Expert 3, interviews). These environmental gains become even more pronounced when EVs are powered through grids increasingly supplied by renewable energy. However, the sustainability of this outcome hinges on the continued decarbonization of national energy systems—a process that remains uneven across many developing regions (Expert 3 & 7 interview).

Despite these promising benefits, the widespread implementation of EVs faces considerable challenges. Infrastructure limitations persist as a key barrier, particularly in rural areas where charging stations are virtually non-existent, and road conditions are suboptimal (Expert 4, interview). Even in urban areas, the expansion of EV adoption is constrained by inadequate grid capacity and a lack of rapid-charging networks. Additionally, the upfront costs associated with EVs, particularly in regions with low per capita income, pose a substantial obstacle for both consumers and governments. Technological challenges, including battery durability, charging times, and limited access to advanced manufacturing capabilities, compound these financial burdens. The disparity between urban and rural regions intensifies these challenges, necessitating careful policy design to ensure equity and long-term adoption across diverse geographies (Expert 2 & 6 interview).

Government action is pivotal to overcoming these structural and economic constraints. Countries such as China have illustrated the power of sustained government intervention through comprehensive subsidy programs and long-term industrial planning, resulting in the rapid growth of their domestic EV sector. Similarly, India’s FAME scheme has offered targeted financial incentives to manufacturers and consumers, accelerating EV production and supporting infrastructure deployment. Interview participants consistently underscored that government efforts must be sustained, holistic, and complemented by regulatory reforms that promote coordination among private actors, municipalities, and civil society stakeholders (Expert 1 & Expert 4, interviews).

Looking ahead, the most immediate market potential for EVs lies in metropolitan areas, where existing infrastructure and consumer readiness provide a foundation for early adoption. The path to mass adoption, however, will require substantial investment in infrastructure, continued improvements in battery technology, and strong policy incentives. Urban centers can serve as proving grounds for scalable models that may later extend into peri-urban and rural settings as affordability improves and supporting infrastructure is expanded (Expert 3, interview).

Beyond economic and infrastructure challenges, the quality of governance and socio-cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping EV adoption. Corruption, bureaucratic fragmentation, and unclear regulatory guidelines often discourage private investment and slow down infrastructure deployment. Cultural beliefs, such as viewing EVs as unreliable, foreign, or mismatched with local travel habits, also affect consumer acceptance. Insights from interviews partially confirm international findings that trust, social norms, and perceived risk significantly influence adoption in low-income areas. Additionally, international funding sources, including climate funds, concessional loans, and development bank programs, are still underutilized in most of the contexts we examined. Examples from India, Kenya, and Indonesia demonstrate that stable governance, targeted subsidies, and access to international financing can accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices, even in environments with limited resources.

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical literature on electromobility and sustainable transport transitions by reinforcing and extending socio-technical transition and technology adoption frameworks within developing-country contexts. Existing theories often conceptualize EV adoption as a function of cost, technology readiness, and policy incentives. The findings of this study demonstrate that in developing economies, adoption dynamics are better understood as an interdependent system in which infrastructure reliability, governance capacity, energy-system structure, and socio-cultural trust jointly shape adoption outcomes.

From a socio-technical systems perspective, the findings highlight infrastructure reliability and grid stability as core regime-level constraints that mediate the effectiveness of EV policies. While transition theories often assume gradual infrastructure adaptation, expert insights in this study show that unreliable electricity supply can negate price incentives and environmental benefits, thereby delaying niche-to-regime transitions. This challenges linear transition assumptions and emphasizes the central role of energy-system readiness in developing-country electromobility pathways.

The results also extend institutional and policy-feedback theories by demonstrating that policy consistency and governance quality are not merely enabling conditions but decisive determinants of market confidence. In contrast to models derived from developed economies, where policy signals are often assumed to be credible and stable, this study demonstrates that fragmented governance, corruption, and regulatory ambiguity can undermine private investment and consumer trust, even when formal incentives are present. This finding suggests the need to explicitly incorporate governance quality into theoretical models of EV adoption in developing regions.

In line with behavioral adoption theories, the findings confirm the importance of perceived risk, social norms, and trust in shaping EV acceptance. However, the study advances these theories by demonstrating that socio-cultural resistance in developing countries is closely intertwined with infrastructure uncertainty and economic vulnerability, rather than being driven solely by individual preference. This interdependence indicates that behavioral models should be embedded within broader socio-technical and institutional frameworks when applied to low- and middle-income contexts.

The differentiated roles of electric two-wheelers (E2Ws) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) identified in this study provide additional theoretical insight. Rather than treating EVs as a homogeneous category, the findings support a staged-transition interpretation in which lower-infrastructure-demand technologies function as transitional niches. This refines existing transition models by illustrating how technology heterogeneity enables incremental decarbonization in contexts where full electrification is not immediately feasible.

Overall, this study contributes to a more context-sensitive theoretical understanding of electromobility transitions by demonstrating that adoption in developing countries cannot be adequately explained by cost or technology readiness alone. Instead, it requires integrated theoretical models that account for the co-evolution of infrastructure, governance, energy systems, and social acceptance. By grounding these insights in expert evidence from multiple developing countries, this research strengthens the external validity of electromobility theory beyond high-income settings.

7.2. Practical Implications and Recommendations

Based on the insights from the literature review and expert interviews, several practical recommendations emerge for managers, policymakers, and urban planners to support EV adoption in developing countries.

Managers, policymakers, and urban planners should consider several strategic implications. Investment in charging networks and energy grid enhancements must be accelerated to meet future demand. Cost reduction strategies should be pursued through collaboration with industry partners to make EVs accessible to a broader demographic. Public awareness campaigns can help mitigate misinformation and increase consumer confidence, encouraging greater uptake. Most critically, EV implementation should be embedded within broader national sustainability agendas, aligning transport policy with renewable energy goals and climate action strategies to maximize long-term impact.

To support this transition, governments should reinforce their commitment to EV adoption through expanded subsidies, tax incentives, and grant programs. These financial instruments can alleviate the burden on consumers and incentivize local manufacturing. Equally important is the urgent need for a comprehensive charging infrastructure, particularly in urban areas where demand is highest. Strengthening the national electricity grid and ensuring interoperability among charging systems will be essential to long-term viability.

Public–private partnerships will be vital in financing, developing, and maintaining infrastructure and related services. Such collaborations allow for shared investment risks and more efficient resource allocation, and can accelerate deployment timelines. Initially prioritizing high-density metropolitan areas can generate momentum and provide empirical insights to inform broader national rollouts. Pilot programs can be launched to test technology, engage communities, and adapt implementation strategies based on local feedback.

Educational campaigns should inform citizens about the economic and environmental advantages of EVs and provide clear guidance on how to access subsidies and charging infrastructure. Parallel to this, governments should allocate funding for research and development to improve battery efficiency, reduce vehicle cost, and integrate renewable energy. International R&D partnerships can further ensure that developing countries are not excluded from global technological progress.

As EV implementation progresses, governments must commit to ongoing monitoring and evaluation of their progress. Policies should be flexible and adaptive, evolving in response to emerging data on adoption patterns, infrastructure performance, and environmental outcomes. This continuous feedback loop will be crucial in ensuring that electromobility not only takes root in developing countries but also thrives as a sustainable, inclusive, and economically beneficial mode of transportation.

To provide a clearer synthesis of the results and to highlight the central insights emerging from both the literature review and expert interviews, the key findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

- EV adoption in developing countries remains low, mainly due to high upfront costs, limited incentives, and weak purchasing power.

- Charging infrastructure is insufficient, and grid unreliability is the single most critical technical barrier.

- Urban areas, especially for two- and three-wheelers, show the most substantial short-term potential.

- Policy consistency and institutional capacity determine whether private investment and consumer adoption can scale.

- Environmental benefits depend heavily on renewable energy integration in national grids.

Furthermore, the following is a concise roadmap outlining how electromobility may evolve from 2025 to 2040:

- 2025–2030—Early Phase: urban pilots, incentives for 2 W/3 W, initial charger rollout, targeted grid upgrades.

- 2030–2035—Scaling Phase: expansion of public charging networks, integration with renewables, early domestic assembly, improved affordability.

- 2035–2040—Consolidation Phase: mass adoption in urban/peri-urban areas, smart-grid integration, battery-recycling systems, rural charging via microgrids.